Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Multicellular organism

View on Wikipedia

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, and more than one cell type, unlike unicellular organisms.[1] All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- and partially multicellular, like slime molds and social amoebae such as the genus Dictyostelium.[2][3]

Multicellular organisms arise in various ways, for example by cell division or by aggregation of many single cells.[4][3] Colonial organisms are the result of many identical individuals joining together to form a colony. However, it can often be hard to separate colonial protists from true multicellular organisms, because the two concepts are not distinct; colonial protists have been dubbed "pluricellular" rather than "multicellular".[5][6] There are also macroscopic organisms that are multinucleate though technically unicellular, such as the Xenophyophorea that can reach 20 cm.

Evolutionary history

[edit]Occurrence

[edit]Multicellularity has evolved independently at least 25 times in eukaryotes,[7][8] and also in some prokaryotes, like cyanobacteria, myxobacteria, actinomycetes, Magnetoglobus multicellularis or Methanosarcina.[3] However, complex multicellular organisms evolved only in six eukaryotic groups: animals, symbiomycotan fungi, brown algae, red algae, green algae, and land plants.[9] It evolved repeatedly for Chloroplastida (green algae and land plants), once for animals, once for brown algae, three times in the fungi (chytrids, ascomycetes, and basidiomycetes)[10] and perhaps several times for slime molds and red algae.[11] To reproduce, true multicellular organisms must solve the problem of regenerating a whole organism from germ cells (i.e., sperm and egg cells), an issue that is studied in evolutionary developmental biology. Animals have evolved a considerable diversity of cell types in a multicellular body (100–150 different cell types), compared with 10–20 in plants and fungi.[12]

The first evidence of multicellular organization, which is when unicellular organisms coordinate behaviors and may be an evolutionary precursor to true multicellularity, is from cyanobacteria-like organisms that lived 3.0–3.5 billion years ago.[7] Decimeter-scale multicellular fossils have been found as early as 1.56 Bya.[13]

Loss of multicellularity

[edit]Loss of multicellularity occurred in some groups.[14] Fungi are predominantly multicellular, though early diverging lineages are largely unicellular (e.g., Microsporidia) and there have been numerous reversions to unicellularity across fungi (e.g., Saccharomycotina, Cryptococcus, and other yeasts).[15][16] It may also have occurred in some red algae (e.g., Porphyridium), but they may be primitively unicellular.[17] Loss of multicellularity is also considered probable in some green algae (e.g., Chlorella vulgaris and some Ulvophyceae).[18][19] In other groups, generally parasites, a reduction of multicellularity occurred, in the number or types of cells (e.g., the myxozoans, multicellular organisms, earlier thought to be unicellular, are probably extremely reduced cnidarians).[20]

Cancer

[edit]Multicellular organisms, especially long-living animals, face the challenge of cancer, which occurs when cells fail to regulate their growth within the normal program of development. Changes in tissue morphology can be observed during this process. Cancer in animals (metazoans) has often been described as a loss of multicellularity and an atavistic reversion towards a unicellular-like state.[21] Many genes responsible for the establishment of multicellularity that originated around the appearance of metazoans are deregulated in cancer cells, including genes that control cell differentiation, adhesion and cell-to-cell communication.[22][23] There is a discussion about the possibility of existence of cancer in other multicellular organisms[24][25] or even in protozoa.[26] For example, plant galls have been characterized as tumors,[27] but some authors argue that plants do not develop cancer.[28]

Separation of somatic and germ cells

[edit]In some multicellular groups, which are called Weismannists, a separation between a sterile somatic cell line and a germ cell line evolved. However, Weismannist development is relatively rare (e.g., vertebrates, arthropods, Volvox), as a great part of species have the capacity for somatic embryogenesis (e.g., land plants, most algae, many invertebrates).[29][10]

Origin hypotheses

[edit]One hypothesis for the origin of multicellularity is that a group of function-specific cells aggregated into a slug-like mass called a grex, which moved as a multicellular unit. This is essentially what slime molds do. Another hypothesis is that a primitive cell underwent nucleus division, thereby becoming a coenocyte. A membrane would then form around each nucleus (and the cellular space and organelles occupied in the space), thereby resulting in a group of connected cells in one organism (this mechanism is observable in Drosophila). A third hypothesis is that as a unicellular organism divided, the daughter cells failed to separate, resulting in a conglomeration of identical cells in one organism, which could later develop specialized tissues. This is what plant and animal embryos do as well as colonial choanoflagellates.[30][31]

Because the first multicellular organisms were simple, soft organisms lacking bone, shell, or other hard body parts, they are not well preserved in the fossil record.[32] One exception may be the demosponge, which may have left a chemical signature in ancient rocks. The earliest fossils of multicellular organisms include the contested Grypania spiralis and the fossils of the black shales of the Palaeoproterozoic Francevillian Group Fossil B Formation in Gabon (Gabonionta).[33] The Doushantuo Formation has yielded 600 million year old microfossils with evidence of multicellular traits.[34]

Until recently, phylogenetic reconstruction has been through anatomical (particularly embryological) similarities. This is inexact, as living multicellular organisms such as animals and plants are more than 500 million years removed from their single-cell ancestors. Such a passage of time allows both divergent and convergent evolution time to mimic similarities and accumulate differences between groups of modern and extinct ancestral species. Modern phylogenetics uses sophisticated techniques such as alloenzymes, satellite DNA and other molecular markers to describe traits that are shared between distantly related lineages.[citation needed]

The evolution of multicellularity could have occurred in several different ways, some of which are described below:

The symbiotic theory

[edit]This theory suggests that the first multicellular organisms occurred from symbiosis (cooperation) of different species of single-cell organisms, each with different roles. Over time these organisms would become so dependent on each other that they would not be able to survive independently, eventually leading to the incorporation of their genomes into one multicellular organism.[35] Each respective organism would become a separate lineage of differentiated cells within the newly created species.[citation needed]

This kind of severely co-dependent symbiosis can be seen frequently, such as in the relationship between clown fish and Riterri sea anemones. In these cases, it is extremely doubtful whether either species would survive very long if the other became extinct. However, the problem with this theory is that it is still not known how each organism's DNA could be incorporated into one single genome to constitute them as a single species. Although such symbiosis is theorized to have occurred (e.g., mitochondria and chloroplasts in animal and plant cells—endosymbiosis), it has happened only extremely rarely and, even then, the genomes of the endosymbionts have retained an element of distinction, separately replicating their DNA during mitosis of the host species. For instance, the two or three symbiotic organisms forming the composite lichen, although dependent on each other for survival, have to separately reproduce and then re-form to create one individual organism once more.[citation needed]

The cellularization (syncytial) theory

[edit]This theory states that a single unicellular organism, with multiple nuclei, could have developed internal membrane partitions around each of its nuclei.[36] Many protists such as the ciliates or slime molds can have several nuclei, lending support to this hypothesis. However, the simple presence of multiple nuclei is not enough to support the theory. Multiple nuclei of ciliates are dissimilar and have clear differentiated functions. The macronucleus serves the organism's needs, whereas the micronucleus is used for sexual reproduction with exchange of genetic material. Slime molds syncitia form from individual amoeboid cells, like syncitial tissues of some multicellular organisms, not the other way round. To be deemed valid, this theory needs a demonstrable example and mechanism of generation of a multicellular organism from a pre-existing syncytium.[citation needed]

The colonial theory

[edit]The colonial theory of Haeckel, 1874, proposes that the symbiosis of many organisms of the same species (unlike the symbiotic theory, which suggests the symbiosis of different species) led to a multicellular organism. At least some – it is presumed land-evolved – multicellularity occurs by cells separating and then rejoining (e.g., cellular slime molds) whereas for the majority of multicellular types (those that evolved within aquatic environments), multicellularity occurs as a consequence of cells failing to separate following division.[37] The mechanism of this latter colony formation can be as simple as incomplete cytokinesis, though multicellularity is also typically considered to involve cellular differentiation.[38]

The advantage of the Colonial Theory hypothesis is that it has been seen to occur independently in 16 different protoctistan phyla. For instance, during food shortages the amoeba Dictyostelium groups together in a colony that moves as one to a new location. Some of these amoeba then slightly differentiate from each other. Other examples of colonial organisation in protista are Volvocaceae, such as Eudorina and Volvox, the latter of which consists of up to 500–50,000 cells (depending on the species), only a fraction of which reproduce.[39] For example, in one species 25–35 cells reproduce, 8 asexually and around 15–25 sexually. However, it can often be hard to separate colonial protists from true multicellular organisms, as the two concepts are not distinct; colonial protists have been dubbed "pluricellular" rather than "multicellular".[5]

The synzoospore theory

[edit]Some authors suggest that the origin of multicellularity, at least in Metazoa, occurred due to a transition from temporal to spatial cell differentiation, rather than through a gradual evolution of cell differentiation, as affirmed in Haeckel's gastraea theory.[40]

GK-PID

[edit]About 800 million years ago,[41] a minor genetic change in a single molecule called guanylate kinase protein-interaction domain (GK-PID) may have allowed organisms to go from a single cell organism to one of many cells.[42]

The role of viruses

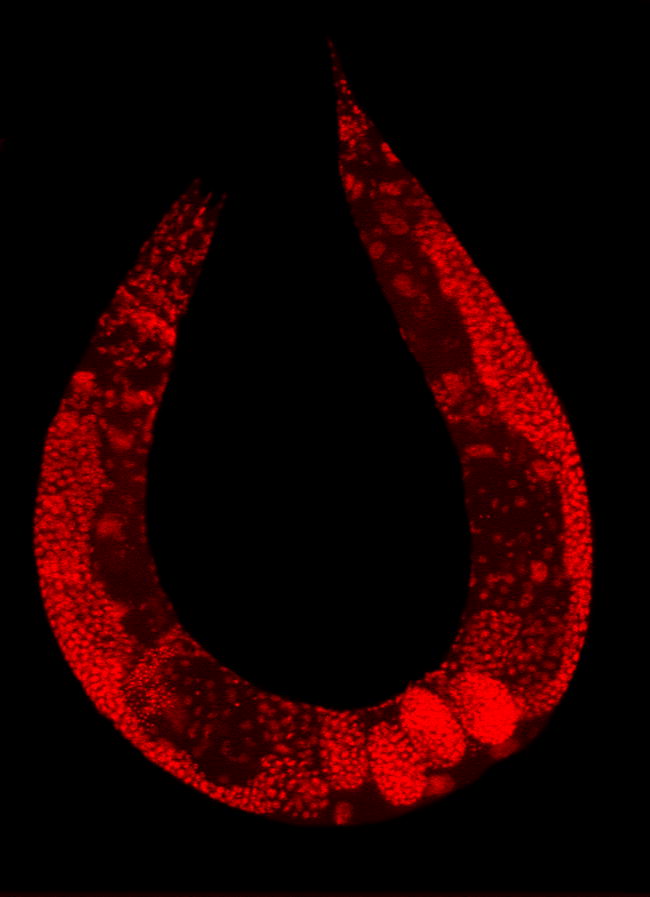

[edit]Genes borrowed from viruses and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) have recently been identified as playing a crucial role in the differentiation of multicellular tissues and organs and even in sexual reproduction, in the fusion of egg cells and sperm.[43][44] Such fused cells are also involved in metazoan membranes such as those that prevent chemicals from crossing the placenta and the brain body separation.[43] Two viral components have been identified. The first is syncytin, which came from a virus.[45] The second identified in 2002 is called EFF-1,[46] which helps form the skin of Caenorhabditis elegans, part of a whole family of FF proteins. Felix Rey, of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, has constructed the 3D structure of the EFF-1 protein[47] and shown it does the work of linking one cell to another, in viral infections. The fact that all known cell fusion molecules are viral in origin suggests that they have been vitally important to the inter-cellular communication systems that enabled multicellularity. Without the ability of cellular fusion, colonies could have formed, but anything even as complex as a sponge would not have been possible.[48]

Oxygen availability hypothesis

[edit]This theory suggests that the oxygen available in the atmosphere of early Earth could have been the limiting factor for the emergence of multicellular life.[49] This hypothesis is based on the correlation between the emergence of multicellular life and the increase of oxygen levels during this time. This would have taken place after the Great Oxidation Event but before the most recent rise in oxygen. Mills concludes that the amount of oxygen present during the Ediacaran is not necessary for complex life and therefore is unlikely to have been the driving factor for the origin of multicellularity.[50]

Snowball Earth hypothesis

[edit]A snowball Earth is a geological event where the entire surface of the Earth is covered in snow and ice. The term can either refer to individual events (of which there were at least two) or to the larger geologic period during which all the known total glaciations occurred.

The most recent snowball Earth took place during the Cryogenian period and consisted of two global glaciation events known as the Sturtian and Marinoan glaciations. Xiao et al.[51] suggest that between the period of time known as the "Boring Billion" and the snowball Earth, simple life could have had time to innovate and evolve, which could later lead to the evolution of multicellularity.

The snowball Earth hypothesis in regards to multicellularity proposes that the Cryogenian period in Earth's history could have been the catalyst for the evolution of complex multicellular life. Brocks suggests that the time between the Sturtian Glacian and the more recent Marinoan Glacian allowed for planktonic algae to dominate the seas making way for rapid diversity of life for both plant and animal lineages. Complex life quickly emerged and diversified in what is known as the Cambrian explosion shortly after the Marinoan.[52]

Predation hypothesis

[edit]The predation hypothesis suggests that to avoid being eaten by predators, simple single-celled organisms evolved multicellularity to make it harder to be consumed as prey. Herron et al. performed laboratory evolution experiments on the single-celled green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, using paramecium as a predator. They found that in the presence of this predator, C. reinhardtii does indeed evolve simple multicellular features.[53]

Experimental evolution

[edit]It is impossible to know what happened when single cells evolved into multicellular organisms hundreds of millions of years ago. However, we can identify mutations that can turn single-celled organisms into multicellular ones. This would demonstrate the possibility of such an event. Unicellular species can relatively easily acquire mutations that make them attach to each other—the first step towards multicellularity. Multiple normally unicellular species have been evolved to exhibit such early steps:

- yeast are long known to exhibit flocculation. One of the first yeast genes found to cause this phenotype is FLO1.[54] A more strikingly clumped phenotype is called "snowflake", caused by the loss of a single transcription factor Ace2. "Snowflake" yeast grow into multicellular clusters that sediment quickly; they were identified by directed evolution.[55] More recently (2024), snowflake yeast were subject to over 3,000 generations of further directed evolution, forming macroscopic assemblies on the scale of millimeters. Changes in multiple genes were identified. In addition, the authors reported that only anaerobic cultures of snowflake yeast evolved this trait, while the aerobic ones did not.[56]

- A range of green algae species have been experimentally evolved to form larger clumps. When Chlorella vulgaris is grown with a predator Ochromonas vallescia, it starts forming small colonies, which are harder to ingest due to the larger size. The same is true for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under predation by Brachionus calyciflorus and Paramecium tetraurelia.

C. reinhartii normally starts as a motile single-celled propagule; this single cell asexually reproduces by undergoing 2–5 rounds of mitosis as a small clump of non-motile cells, then all cells become single-celled propagules and the clump dissolves. With a few generations under Paramecium predation, the "clump" becomes a persistent structure: only some cells become propagules. Some populations go further and evolved multi-celled propagules: instead of peeling off single cells from the clump, the clump now reproduces by peeling off smaller clumps.[53]

Advantages

[edit]Multicellularity allows an organism to exceed the size limits normally imposed by diffusion: single cells with increased size have a decreased surface-to-volume ratio and have difficulty absorbing sufficient nutrients and transporting them throughout the cell. Multicellular organisms thus have the competitive advantages of an increase in size without its limitations. They can have longer lifespans as they can continue living when individual cells die. Multicellularity also permits increasing complexity by allowing differentiation of cell types within one organism.[citation needed]

Whether all of these can be seen as advantages however is debatable: The vast majority of living organisms are single celled, and even in terms of biomass, single celled organisms are far more successful than animals, although not plants.[57] Rather than seeing traits such as longer lifespans and greater size as an advantage, many biologists see these only as examples of diversity, with associated tradeoffs.[citation needed]

Gene expression changes in the transition from uni- to multicellularity

[edit]During the evolutionary transition from unicellular organisms to multicellular organisms, the expression of genes associated with reproduction and survival likely changed.[58] In the unicellular state, genes associated with reproduction and survival are expressed in a way that enhances the fitness of individual cells, but after the transition to multicellularity, the pattern of expression of these genes must have substantially changed so that individual cells become more specialized in their function relative to reproduction and survival.[58] As the multicellular organism emerged, gene expression patterns became compartmentalized between cells that specialized in reproduction (germline cells) and those that specialized in survival (somatic cells). As the transition progressed, cells that specialized tended to lose their own individuality and would no longer be able to both survive and reproduce outside the context of the group.[58]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Becker, Wayne M.; et al. (2008). The world of the cell. Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-321-55418-5.

- ^ Chimileski, Scott; Kolter, Roberto (2017). Life at the Edge of Sight: A Photographic Exploration of the Microbial World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97591-0.

- ^ a b c Lyons, Nicholas A.; Kolter, Roberto (April 2015). "On the evolution of bacterial multicellularity". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 24: 21–28. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2014.12.007. ISSN 1879-0364. PMC 4380822. PMID 25597443.

- ^ Miller, S.M. (2010). "Volvox, Chlamydomonas, and the evolution of multicellularity". Nature Education. 3 (9): 65.

- ^ a b Hall, Brian Keith; Hallgrímsson, Benedikt; Strickberger, Monroe W. (2008). Strickberger's evolution: the integration of genes, organisms and populations (4th ed.). Hall/Hallgrímsson. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-7637-0066-9.

- ^ Adl SM, Simpson AG, Farmer MA, Andersen RA, Anderson OR, Barta JR, Bowser SS, Brugerolle G, Fensome RA, Fredericq S, James TY, Karpov S, Kugrens P, Krug J, Lane CE, Lewis LA, Lodge J, Lynn DH, Mann DG, McCourt RM, Mendoza L, Moestrup O, Mozley-Standridge SE, Nerad TA, Shearer CA, Smirnov AV, Spiegel FW, Taylor MF (October 2005). "The New Higher Level Classification of Eukaryotes with Emphasis on the Taxonomy of Protists". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 52 (5): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. PMID 16248873. S2CID 8060916.

- ^ a b Grosberg, RK; Strathmann, RR (2007). "The evolution of multicellularity: A minor major transition?" (PDF). Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 38: 621–654. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102403.114735.

- ^ Parfrey, L.W.; Lahr, D.J.G. (2013). "Multicellularity arose several times in the evolution of eukaryotes" (PDF). BioEssays. 35 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1002/bies.201200143. PMID 23315654. S2CID 13872783. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-25.

- ^ Popper, Zoë A.; Michel, Gurvan; Hervé, Cécile; Domozych, David S.; Willats, William G.T.; Tuohy, Maria G.; Kloareg, Bernard; Stengel, Dagmar B. (2011). "Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: From algae to flowering plants". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 62 (1): 567–590. Bibcode:2011AnRPB..62..567P. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103809. hdl:10379/6762. PMID 21351878. S2CID 11961888.

- ^ a b Niklas, K.J. (2014). "The evolutionary-developmental origins of multicellularity". American Journal of Botany. 101 (1): 6–25. Bibcode:2014AmJB..101....6N. doi:10.3732/ajb.1300314. PMID 24363320.

- ^ Bonner, John Tyler (1998). "The origins of multicellularity". Integrative Biology. 1 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6602(1998)1:1<27::AID-INBI4>3.0.CO;2-6. ISSN 1093-4391.

- ^ Margulis, L.; Chapman, M.J. (2009). "2. Kingdom Protoctista". Kingdoms and Domains: An illustrated guide to the phyla of life on Earth (4th ed.). Academic Press / Elsevier. p. 116. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-373621-5.00002-7. ISBN 978-0-12-373621-5. OCLC 990541741.

- ^ Zhu, S; Zhu, M; Knoll, A; et al. (2016). "Decimetre-scale multicellular eukaryotes from the 1.56-billion-year-old Gaoyuzhuang Formation in North China". Nat Commun. 7 11500. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711500Z. doi:10.1038/ncomms11500. PMC 4873660. PMID 27186667.

- ^ Seravin, L.N. (2001). "The principle of counter-directional morphological evolution and its significance for constructing the megasystem of protists and other eukaryotes". Protistology. 2: 6–14.

- ^ Parfrey & Lahr 2013, p. 344

- ^ Medina, M.; Collins, A.G.; Taylor, J.W.; Valentine, J.W.; Lipps, J.H.; Zettler, L.A. Amaral; Sogin, M.L. (2003). "Phylogeny of Opisthokonta and the evolution of multicellularity and complexity in Fungi and Metazoa". International Journal of Astrobiology. 2 (3): 203–211. Bibcode:2003IJAsB...2..203M. doi:10.1017/s1473550403001551.

- ^ Seckbach, Joseph; Chapman, David J., eds. (2010). "5 Porphyridiophyceae". Red algae in the genomic age. Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology. Vol. 13. Springer. p. 252. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3795-4. ISBN 978-90-481-3795-4.

- ^ Cocquyt, E.; Verbruggen, H.; Leliaert, F.; De Clerck, O. (2010). "Evolution and Cytological Diversification of the Green Seaweeds (Ulvophyceae)". Mol. Biol. Evol. 27 (9): 2052–61. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq091. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 20368268.

- ^ Richter, Daniel Joseph (2013). The gene content of diverse choanoflagellates illuminates animal origins (PhD). University of California, Berkeley. OCLC 1464736521. ark:/13030/m5wd44q5.

- ^ "Myxozoa". tolweb.org. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Davies, P.C.W.; Lineweaver, C.H. (2011). "Cancer tumors as Metazoa 1.0: tapping genes of ancient ancestors". Physical Biology. 8 (1) 015001. Bibcode:2011PhBio...8a5001D. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/8/1/015001. PMC 3148211. PMID 21301065.

- ^ Domazet-Loso, T.; Tautz, D. (2010). "Phylostratigraphic tracking of cancer genes suggests a link to the emergence of multicellularity in metazoa". BMC Biology. 8 (66): 66. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-66. PMC 2880965. PMID 20492640.

- ^ Jacques, F.; Baratchart, E.; Pienta, K.; Hammarlund, E. (2022). "Origin and evolution of animal multicellularity in the light of phylogenomics and cancer genetics". Medical Oncology. 39 (160): 1–14. doi:10.1007/s12032-022-01740-w. PMC 9381480. PMID 35972622..

- ^ Richter 2013, p. 11

- ^ Gaspar, T.; Hagege, D.; Kevers, C.; Penel, C.; Crèvecoeur, M.; Engelmann, I.; Greppin, H.; Foidart, J.M. (1991). "When plant teratomas turn into cancers in the absence of pathogens". Physiologia Plantarum. 83 (4): 696–701. Bibcode:1991PPlan..83..696G. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1991.tb02489.x.

- ^ Lauckner, G. (1980). Diseases of protozoa. In: Diseases of Marine Animals. Kinne, O. (ed.). Vol. 1, p. 84, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK.

- ^ Riker, A.J. (1958). "Plant tumors: Introduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 44 (4): 338–9. Bibcode:1958PNAS...44..338R. doi:10.1073/pnas.44.4.338. PMC 335422. PMID 16590201.

- ^ Doonan, J.; Hunt, T. (1996). "Cell cycle. Why don't plants get cancer?". Nature. 380 (6574): 481–2. doi:10.1038/380481a0. PMID 8606760. S2CID 4318184.

- ^ Ridley M (2004) Evolution, 3rd edition. Blackwell Publishing, p. 295–297.

- ^ Fairclough, Stephen R.; Dayel, Mark J.; King, Nicole (26 October 2010). "Multicellular development in a choanoflagellate". Current Biology. 20 (20): R875 – R876. Bibcode:2010CBio...20.R875F. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.014. PMC 2978077. PMID 20971426.

- ^ Carroll, Sean B. (December 14, 2010). "In a Single-Cell Predator, Clues to the Animal Kingdom's Birth". The New York Times.

- ^ A H Knoll, 2003. Life on a Young Planet. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00978-3 (hardcover), ISBN 0-691-12029-3 (paperback). An excellent book on the early history of life, very accessible to the non-specialist; includes extensive discussions of early signatures, fossilization, and organization of life.

- ^ El Albani, Abderrazak; et al. (1 July 2010). "Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago". Nature. 466 (7302): 100–4. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..100A. doi:10.1038/nature09166. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20596019. S2CID 4331375.

- ^ Chen, L.; Xiao, S.; Pang, K.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, X. (2014). "Cell differentiation and germ–soma separation in Ediacaran animal embryo-like fossils". Nature. 516 (7530): 238–241. Bibcode:2014Natur.516..238C. doi:10.1038/nature13766. PMID 25252979. S2CID 4448316.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn (1998). Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution. Basic Books. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-465-07272-9. Archived from the original on 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ Hickman CP, Hickman FM (8 July 1974). Integrated Principles of Zoology (5th ed.). Mosby. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8016-2184-0.

- ^ Wolpert, L.; Szathmáry, E. (2002). "Multicellularity: Evolution and the egg". Nature. 420 (6917): 745. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..745W. doi:10.1038/420745a. PMID 12490925. S2CID 4385008.

- ^ Kirk, D.L. (2005). "A twelve-step program for evolving multicellularity and a division of labor". BioEssays. 27 (3): 299–310. doi:10.1002/bies.20197. PMID 15714559.

- ^ AlgaeBase. Volvox Linnaeus, 1758: 820.

- ^ Mikhailov, Kirill V.; Konstantinova, Anastasiya V.; Nikitin, Mikhail A.; Troshin, Peter V.; Rusin, Leonid Yu.; Lyubetsky, Vassily A.; Panchin, Yuri V.; Mylnikov, Alexander P.; Moroz, Leonid L.; Kumar, Sudhir; Aleoshin, Vladimir V. (2009). "The origin of Metazoa: A transition from temporal to spatial cell differentiation" (PDF). BioEssays. 31 (7): 758–768. doi:10.1002/bies.200800214. PMID 19472368. S2CID 12795095. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05.

- ^ Erwin, Douglas H. (9 November 2015). "Early metazoan life: divergence, environment and ecology". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 370 20150036. Bibcode:2015RSPTB.37050036E. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0036. PMC 4650120. PMID 26554036.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (7 January 2016). "Genetic Flip Helped Organisms Go From One Cell to Many". New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ a b Koonin, E.V. (2016). "Viruses and mobile elements as drivers of evolutionary transitions". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1701). doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0442. PMC 4958936. PMID 27431520.

- ^ Letzter, Rafi (2018-02-02). "An Ancient Virus May Be Responsible for Human Consciousness". Live Science. Retrieved 2022-09-05.

- ^ Mi, S.; Lee, X.; Li, X.; Veldman, G.M.; Finnerty, H.; Racie, L.; Lavallie, E.; Tang, X.Y.; Edouard, P.; Howes, S.; Keith Jr, J.C.; McCoy, J.M. (2000). "Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis". Nature. 403 (6771): 785–9. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..785M. doi:10.1038/35001608. PMID 10693809. S2CID 4367889.

- ^ Mohler, William A.; Shemer, Gidi; del Campo, Jacob J.; Valansi, Clari; Opoku-Serebuoh, Eugene; Scranton, Victoria; Assaf, Nirit; White, John G.; Podbilewicz, Benjamin (March 2002). "The Type I Membrane Protein EFF-1 Is Essential for Developmental Cell Fusion". Developmental Cell. 2 (3): 355–362. doi:10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00129-6. ISSN 1534-5807. PMID 11879640.

- ^ Pérez-Vargas, Jimena; Krey, Thomas; Valansi, Clari; Avinoam, Ori; Haouz, Ahmed; Jamin, Marc; Raveh-Barak, Hadas; Podbilewicz, Benjamin; Rey, Félix A. (2014). "Structural Basis of Eukaryotic Cell-Cell Fusion". Cell. 157 (2): 407–419. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.020. PMID 24725407.

- ^ Slezak, Michael (2016), "No Viruses? No skin or bones either" (New Scientist, No. 2958, 1 March 2014) p.16

- ^ Nursall, J.R. (April 1959). "Oxygen as a Prerequisite to the Origin of the Metazoa". Nature. 183 (4669): 1170–2. Bibcode:1959Natur.183.1170N. doi:10.1038/1831170b0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4200584.

- ^ Mills, D.B.; Ward, L.M.; Jones, C.; Sweeten, B.; Forth, M.; Treusch, A.H.; Canfield, D.E. (2014-02-18). "Oxygen requirements of the earliest animals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (11): 4168–72. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4168M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1400547111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3964089. PMID 24550467.

- ^ Lyons, Timothy W.; Droser, Mary L.; Lau, Kimberly V.; Porter, Susannah M.; Xiao, Shuhai; Tang, Qing (2018-09-28). "After the boring billion and before the freezing millions: Evolutionary patterns and innovations in the Tonian Period". Emerging Topics in Life Sciences. 2 (2): 161–171. Bibcode:2018ETLS....2..161X. doi:10.1042/ETLS20170165. hdl:10919/86820. ISSN 2397-8554. PMID 32412616. S2CID 90374085.

- ^ Brocks, Jochen J.; Jarrett, Amber J.M.; Sirantoine, Eva; Hallmann, Christian; Hoshino, Yosuke; Liyanage, Tharika (August 2017). "The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals". Nature. 548 (7669): 578–581. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..578B. doi:10.1038/nature23457. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 28813409. S2CID 205258987.

- ^ a b Herron, Matthew D.; Borin, Joshua M.; Boswell, Jacob C.; Walker, Jillian; Chen, I.-Chen Kimberly; Knox, Charles A.; Boyd, Margrethe; Rosenzweig, Frank; Ratcliff, William C. (2019-02-20). "De novo origins of multicellularity in response to predation". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 2328. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.2328H. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39558-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6382799. PMID 30787483.

- ^ Smukalla, Scott; Caldara, Marina; Pochet, Nathalie; Beauvais, Anne; Guadagnini, Stephanie; Yan, Chen; Vinces, Marcelo D.; Jansen, An; Prevost, Marie Christine; Latgé, Jean-Paul; Fink, Gerald R.; Foster, Kevin R.; Verstrepen, Kevin J. (2008-11-14). "FLO1 is a variable green beard gene that drives biofilm-like cooperation in budding yeast". Cell. 135 (4): 726–737. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.037. ISSN 1097-4172. PMC 2703716. PMID 19013280.

- ^ Oud, Bart; Guadalupe-Medina, Victor; Nijkamp, Jurgen F.; De Ridder, Dick; Pronk, Jack T.; Van Maris, Antonius J.A.; Daran, Jean-Marc (2013). "Genome duplication and mutations in ACE2 cause multicellular, fast-sedimenting phenotypes in evolved Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (45): E4223-31. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110E4223O. doi:10.1073/pnas.1305949110. PMC 3831460. PMID 24145419.

- ^ Bozdag, G. Ozan; Zamani-Dahaj, Seyed Alireza; Day, Thomas C.; Kahn, Penelope C.; Burnetti, Anthony J.; Lac, Dung T.; Tong, Kai; Conlin, Peter L.; Balwani, Aishwarya H.; Dyer, Eva L.; Yunker, Peter J.; Ratcliff, William C. (2023-05-25). "De novo evolution of macroscopic multicellularity". Nature. 617 (7962): 747–754. Bibcode:2023Natur.617..747B. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06052-1. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 10425966. PMID 37165189. S2CID 236953093.

- ^ Bar-On, Yinon M.; Phillips, Rob; Milo, Ron (2018-06-19). "The biomass distribution on Earth". PNAS. 115 (25): 6506–11. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6506B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. PMC 6016768. PMID 29784790.

- ^ a b c Grochau-Wright ZI, Nedelcu AM, Michod RE (April 2023). "The Genetics of Fitness Reorganization during the Transition to Multicellularity: The Volvocine regA-like Family as a Model". Genes (Basel). 14 (4): 941. doi:10.3390/genes14040941. PMC 10137558. PMID 37107699.

External links

[edit]- Tree of Life Eukaryotes. Archived 2012-01-29 at the Wayback Machine.

Multicellular organism

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Definition

A multicellular organism is defined as an entity composed of more than one cell, where the cells remain associated after division, exhibit specialization for division of labor, maintain permanent adhesion, and engage in intercellular communication to coordinate functions. This definition emphasizes the cooperative integration of cells into a cohesive unit, enabling enhanced size, complexity, and efficiency compared to solitary cells.[4] In contrast to unicellular organisms, which rely on a single cell to perform all vital processes such as metabolism, reproduction, and response to stimuli, multicellular organisms distribute these responsibilities across specialized cell types forming coordinated groups that develop into tissues and organs.[9] While some prokaryotes, such as certain bacteria forming biofilms or filaments, exhibit primitive multicellular traits like aggregation and division of labor, the term often refers to sustained, clonal structures typical in eukaryotes.[10] The concept of multicellular organisms emerged in the 19th century alongside cell theory, formulated by Matthias Schleiden for plants in 1838 and extended by Theodor Schwann to animals in 1839, recognizing that living organisms are composed of cells and their products.[11] Modern interpretations, however, focus on multicellularity as an evolutionary innovation involving transitions from unicellular ancestors through mechanisms like adhesion and signaling.Key Structural Features

Multicellular organisms rely on specialized mechanisms for cell adhesion to maintain structural integrity and enable collective function. In eukaryotes, these mechanisms primarily involve the extracellular matrix (ECM), a network of proteins and polysaccharides secreted by cells that provides scaffolding for tissue architecture and mediates cell-matrix interactions.[12] Cadherins, a family of calcium-dependent transmembrane proteins, facilitate homophilic cell-to-cell adhesion by forming adherens junctions, which link the actin cytoskeleton of adjacent cells and are essential for tissue morphogenesis.[13] Tight junctions, composed of proteins like claudins and occludins, seal the intercellular space to prevent leakage and maintain polarity, particularly in epithelial layers.[14] Cell-to-cell communication is crucial for coordinating multicellular behavior, achieved through signaling pathways that transmit information across cells. The Notch pathway enables direct contact-dependent signaling, where ligand-receptor interactions trigger proteolytic cleavage of the Notch receptor, releasing the intracellular domain to regulate gene expression and influence cell fate decisions such as differentiation and proliferation.[15] Similarly, the Wnt pathway facilitates paracrine signaling by stabilizing β-catenin upon ligand binding to receptors, which then translocates to the nucleus to activate transcription factors, thereby coordinating pattern formation and tissue homeostasis in multicellular contexts.[16] These pathways ensure synchronized responses among cells, preventing disorganized growth. Tissue formation arises from the differentiation of totipotent or pluripotent cells into specialized types, allowing division of labor within the organism. Epithelial cells, for instance, form sheets that line surfaces and cavities, providing barrier functions through apical-basal polarity maintained by adhesion structures.[17] Connective tissue cells, such as fibroblasts, secrete ECM components like collagen and elastin to support structural framework, enabling resilience and nutrient transport in multicellular assemblies.[17] This differentiation process integrates adhesion and signaling to generate functional tissues without relying on specific kingdom examples. A simple model for these features is the green alga Volvox, which forms spherical colonies of up to 50,000 biflagellated cells embedded in an ECM, with somatic cells on the exterior for motility and reproductive cells internally, illustrating basic adhesion and differentiation in a multicellular aggregate.[18]Levels of Organization

Multicellular organisms exhibit a hierarchical organization that ranges from rudimentary cell groupings to highly integrated structures, enabling functional complexity and adaptability. At the most basic level, simple multicellularity involves loose aggregates of cells that temporarily associate without permanent adhesion or differentiation, as seen in cellular slime molds like Dictyostelium discoideum, where individual amoebae aggregate under starvation to form a migratory slug-like structure that eventually develops into a fruiting body for spore dispersal.[19] This form of organization lacks true tissue formation and relies on transient cell-cell interactions, primarily through signaling molecules, to achieve collective behaviors such as chemotaxis.[20] Intermediate levels of organization build on this by incorporating colonial structures with emerging division of labor, exemplified by volvocine algae such as Volvox species. In these spherical colonies, cells are embedded in an extracellular matrix and exhibit partial specialization, where somatic cells handle motility and photosynthesis while a few larger gonidial cells dedicate to reproduction.[21] This division enhances efficiency in resource allocation and locomotion, marking a transition toward more stable multicellular units without the full compartmentalization of tissues.[22] In complex multicellular organisms, organization escalates to form tissues, organs, and organ systems, allowing for specialized functions across scales. Tissues arise from similar cell types performing coordinated roles, such as epithelial tissues for barrier functions or connective tissues for support; these integrate into organs like the heart, which comprises muscle, connective, and neural tissues to pump blood.[23] Organ systems further interconnect these, as in the animal circulatory system, where the heart and blood vessels distribute oxygen and nutrients throughout the body, or the plant vascular system, consisting of xylem for water transport and phloem for nutrient distribution, enabling growth and homeostasis in large-bodied forms. This hierarchical integration supports physiological unity despite cellular diversity. The spectrum of multicellular organization underscores its scalability, from minimal configurations like Volvox colonies with 500 to 50,000 cells to vast assemblies in humans comprising approximately 36 trillion cells in adult males.[24][25] Such variation highlights how organizational levels facilitate evolutionary diversification, with cell numbers correlating to body size and functional demands while maintaining cohesive operation through intercellular communication.[23]Evolutionary History

Timeline of Emergence

The earliest evidence of multicellular organisms dates to approximately 2.1 billion years ago, preserved in the Francevillian biota of the Paleoproterozoic Era in what is now Gabon. These macroscopic structures, including discoidal and tubular forms up to 12 cm in length, exhibit coordinated growth patterns suggestive of multicellular organization, though their biogenicity and exact affinity (prokaryotic or early eukaryotic) remain debated. Fossil evidence for eukaryotic multicellularity first appears around 1.6 billion years ago, with the discovery of cellularly preserved red algae such as Rafatazmia chitrakootensis and Ramathallus lobatus from the Vindhyan Supergroup in India. These fossils demonstrate subcellular structures like branched filaments and cell walls, predating previous records of red algae by about 400 million years and indicating the emergence of crown-group eukaryotes capable of multicellularity. Complementary chemical signatures, such as steranes—lipid biomarkers derived from eukaryotic sterols—provide indirect evidence of eukaryotic presence in rocks as old as 1.64 billion years from the Chuanlinggou Formation in North China. Direct fossil evidence includes multicellular microfossils such as Qingshania magnifica from the same formation, confirming early eukaryotic multicellular organization.[26] These findings support the diversification of early multicellular eukaryotes during the Mesoproterozoic. Multicellularity evolved independently in major eukaryotic lineages over the subsequent billion years. In the plant lineage (archaeplastida), multicellular forms arose around 1 billion years ago, as inferred from molecular clock analyses and fossilized green algal filaments such as Proterocladus antiquus from the Nanfen Formation in North China, marking the transition from unicellular to colonial and filamentous growth in streptophytes.[27] Similarly, in fungi (opisthokonts), multicellularity likely originated around 1 billion years ago, with phylogenetic estimates placing the common ancestor of dikarya (including ascomycetes and basidiomycetes) at 0.9–1.4 billion years ago, evidenced by early hyphal-like structures in Proterozoic cherts. For animals (metazoans), the transition to multicellularity occurred approximately 800 million years ago, supported by molecular clocks and the appearance of sponge-derived biomarkers like 24-isopropylcholestanes in Tonian sediments around 800–650 million years ago. By the Ediacaran Period, around 600 million years ago, complex multicellular animal-like organisms proliferated in the Ediacaran biota, represented by soft-bodied fossils such as Charnia and Dickinsonia from sites in Australia, Newfoundland, and Russia. These rangeomorphs and dickinsoniids, up to 2 meters in size, display fractal branching and epithelial-like tissues, signaling a diversification of multicellular eukaryotes just before the Cambrian explosion. Sterane biomarkers become more abundant in Ediacaran rocks, corroborating the expansion of eukaryotic multicellular life during this interval of rising oxygen levels.Multiple Independent Origins

Multicellularity has arisen independently at least 25 times across eukaryotic lineages, with recent analyses identifying up to 45 distinct cases of simple multicellular forms, categorized into six functional types based on developmental and structural criteria.[28][29] These transitions occurred in diverse clades, including opisthokonts, archaeplastida, amoebozoa, and stramenopiles, demonstrating the repeated feasibility of this evolutionary innovation from unicellular ancestors. Within the opisthokont supergroup, which encompasses animals, fungi, and their unicellular relatives, multicellularity evolved at least three times independently. Animals originated from choanoflagellate-like unicellular or colonial protists, where cell aggregation and differentiation led to metazoan complexity around 600 million years ago.[30] Multicellular fungi, in contrast, arose from unicellular yeast ancestors through the development of hyphal structures and filamentous growth, with evidence from genomic comparisons showing distinct genetic co-options for cell-cell interactions.[28] A third instance involves aggregative multicellularity in opisthokont protists like Fonticula alba, which forms fruiting bodies through cell aggregation similar to amoebozoan slime molds but via a separate evolutionary path.[31] In the archaeplastida supergroup, particularly the Viridiplantae clade comprising green algae and land plants, multicellularity transitioned from unicellular algal ancestors to complex terrestrial forms, involving the evolution of cell walls and polarized growth independent of animal or fungal mechanisms.[32] Brown algae (Phaeophyceae) in the stramenopile lineage represent another major independent origin, achieving large, differentiated multicellular bodies with specialized tissues like holdfasts and blades, distinct from green plant architectures.[28] Meanwhile, amoebozoan slime molds, such as Dictyostelium discoideum, exhibit aggregative multicellularity where unicellular amoebae temporarily form multicellular slugs and fruiting structures in response to starvation, marking yet another convergent instance outside opisthokonts and archaeplastida.[33] These independent origins highlight convergent evolution in key multicellular traits, such as cell adhesion, which facilitates stable associations but arose through disparate molecular pathways. In animals, classical cadherins mediate calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion, whereas plants lack cadherins and instead utilize pectin-based cell wall modifications and receptor-like kinases for intercellular connections; fungi employ glycoproteins like mannoproteins for hyphal adhesion, and brown algae rely on alginates and fucoidans in their extracellular matrices.[34] This molecular diversity underscores how similar functional outcomes were achieved via lineage-specific genetic innovations, without shared ancestry for these adhesion systems.Loss and Re-evolution

Multicellularity, having arisen multiple times independently across eukaryotic lineages, demonstrates notable evolutionary plasticity through instances of secondary loss. In the animal kingdom, myxozoans exemplify this reversal; these obligate parasites, classified within Cnidaria, evolved from multicellular ancestors but underwent drastic simplification to highly reduced, effectively unicellular somatic forms consisting of syncytial plasmodia or single cells.[35] Genomic analyses reveal massive gene loss and genome size reduction accompanying this transition, adapting them to parasitic lifestyles within vertebrate and invertebrate hosts.[36] Similarly, in fungi, unicellular yeasts such as those in the Saccharomycotina clade represent secondary losses from multicellular ancestors, with phylogenetic reconstructions indicating multiple independent reversions to unicellularity across the kingdom.[37] These losses often involve partial or complete abandonment of hyphal growth and compartmentalization, key multicellular traits in fungi.[38] Such reversions are frequently driven by selective pressures favoring simplification, particularly in parasitic or environmentally stable niches where complex multicellular structures confer no advantage or impose costs. For myxozoans, the parasitic lifestyle necessitates streamlined body plans for efficient host invasion and spore production, leading to the loss of tissues, organs, and even aerobic respiration in some species.[39] In fungi, environmental simplification or niche shifts, such as transitions to free-living unicellular states, promote the erosion of multicellularity through relaxed selection on group-level traits.[40] These factors underscore how multicellularity can be dispensable when individual-level fitness dominates over collective benefits. Re-evolution of multicellularity following loss is rare, reflecting the challenges of reassembling coordinated cellular behaviors, but evidence from volvocine algae lineages illustrates its potential. In this group of green algae, multicellularity and cellular differentiation prove evolutionarily labile, with phylotranscriptomic studies revealing patterns of reversal and independent re-emergence within the Volvocales order, suggesting that simple colonial forms can transition back and forth.[41] Experimental evolution provides further support for reversibility; in laboratory settings with unicellular precursors like yeast, selection can drive rapid shifts to multicellular aggregates and back to unicellularity, demonstrating that early-stage multicellularity is not strongly canalized.[42] Overall, losses occur more frequently in early, facultative multicellular transitions—such as colonial or aggregative forms—than in highly integrated complex multicellularity, where reversal would require improbable coordinated regains of developmental pathways.[36]Theories of Transition to Multicellularity

Colonial Theory

The colonial theory proposes that multicellularity originated when unicellular organisms formed loose, temporary aggregates that gradually evolved into stable colonies through natural selection favoring group-level benefits, such as enhanced resource acquisition or protection from predation.[43] This process involves cells adhering to one another, transitioning from independent entities to interdependent units where survival depends on collective function.[9] Originally formulated by Ernst Haeckel in 1874 as part of his gastraea theory, the colonial hypothesis suggested that early metazoans arose from colonial flagellates, with cell adhesion enabling the formation of hollow, spherical structures resembling modern sponges.[44] Modern empirical support comes from studies of volvocine green algae, a clade spanning unicellular forms like Chlamydomonas to complex colonies like Volvox, where phylogenetic and experimental evidence demonstrates stepwise evolution from solitary cells to multicellular aggregates.[45] In these algae, natural selection has favored colonial forms over millions of years, with genetic analyses revealing that key innovations, such as extracellular matrix production, promoted permanent adhesion without requiring fusion of distinct lineages.[46] The evolutionary steps under this theory begin with temporary aggregates of similar cells, often facilitated by basic cell adhesion mechanisms like glycoprotein linkages on cell surfaces.[47] These aggregates then stabilize through permanent adhesion, where cells lose individual motility and invest in shared structures, such as protective sheaths in cyanobacteria or spherical matrices in volvocines. Finally, division of labor emerges, with specialized cell types—such as somatic cells for motility and structural support, and reproductive cells for propagation—arising via differential gene expression, as observed in Volvox carteri where regA mutants revert to undifferentiated colonies.[48] Supporting evidence from the fossil record includes stromatolites formed by colonial cyanobacteria from the Archaean Pilbara Craton in Australia, dated to approximately 3.5 billion years ago, indicating early aggregation and filamentation as precursors to multicellular cooperation. Phylogenetic reconstructions further suggest that multicellularity in cyanobacteria predates eukaryotic origins, with most modern lineages descending from colonial ancestors and multiple reversals to unicellularity occurring later.[49]Symbiotic and Syncytial Theories

The symbiotic theory posits that multicellularity emerged through cooperative associations between genetically distinct unicellular organisms from different lineages, analogous to the endosymbiotic origins of organelles, where mutual benefits drive integration into a unified structure.[50] Pioneered by Lynn Margulis in the 1990s, this view extends her serial endosymbiosis hypothesis to higher-level organization, suggesting that tissues or organs in multicellular organisms represent symbioses among specialized cell types derived from diverse prokaryotic or eukaryotic ancestors.[51] A key example is lichen formation, where a fungal partner (typically an ascomycete) and an algal or cyanobacterial phototroph form a composite thallus exhibiting multicellular-like architecture, including layered tissues for protection and nutrient exchange, demonstrating how interspecies cooperation can yield complex, interdependent forms without initial genetic uniformity. In contrast, the syncytial theory proposes that multicellularity arose via the cellularization of a coenocytic ancestor—a single cell with multiple nuclei sharing a common cytoplasm (syncytium)—followed by the partitioning of nuclei into individual cells through membrane ingrowth.[52] This process maintains genetic homogeneity across the emerging cells, as all nuclei derive from the same zygote, and is observed in the early development of certain animals and fungi. For instance, in Drosophila melanogaster embryos, the initial syncytial blastoderm stage involves 13 rapid nuclear divisions without cytokinesis, creating a multinucleate cytoplasm that later undergoes cellularization to form the cellular blastoderm, illustrating a developmental mechanism that may recapitulate evolutionary origins.[53] Similarly, many fungi, such as zygomycetes, grow as coenocytic hyphae where nuclei divide within a shared cytoplasm before septa form to compartmentalize cells, providing evidence for syncytial intermediates in fungal multicellular evolution.[36] The primary distinction between these theories lies in the genetic and structural starting points: symbiotic models emphasize mergers of evolutionarily distinct entities retaining partial genetic independence, fostering diversity through inter-lineage interactions, whereas syncytial models highlight internal subdivision of a unified cytoplasm, promoting cohesion via shared ancestry but potentially limiting initial cellular specialization. Both offer alternatives to simpler adhesion-based aggregations by involving deeper physiological integration, though empirical support remains indirect, drawn largely from extant developmental processes and symbiotic consortia rather than fossil records.[52]Environmental and Ecological Hypotheses

Environmental and ecological hypotheses propose that external pressures, such as changes in atmospheric composition and climatic extremes, exerted selective forces favoring the transition from unicellular to multicellular life by promoting aggregation, increased size, and enhanced survival strategies. These ideas emphasize how abiotic and biotic interactions in ancient environments could drive the evolution of cell adhesion and cooperation, without relying on internal cellular mechanisms. The Great Oxidation Event (GOE), occurring approximately 2.4 billion years ago, exemplifies such a pressure, as the dramatic rise in atmospheric oxygen levels—resulting from cyanobacterial photosynthesis—created a more energetic environment that supported larger cell sizes and the formation of multicellular aggregates.[54] This oxygenation shift, often termed the catastrophic oxidation due to its devastating impact on anaerobic life, paradoxically enabled aerobic metabolism, providing the metabolic efficiency necessary for multicellular structures to emerge and persist.[55] By increasing oxygen availability, the GOE facilitated higher energy yields, allowing cells to overcome diffusion limitations and form stable clusters that conferred advantages in resource acquisition.[54] Climatic upheavals, particularly the Cryogenian glaciations known as Snowball Earth events around 720–635 million years ago, further illustrate how extreme environmental conditions selected for multicellular traits. During these periods, global ice cover drastically reduced sunlight penetration and nutrient availability in oceans, creating viscous, low-energy aquatic environments that challenged unicellular mobility and survival.[56] Multicellularity likely evolved as an adaptive response, enabling organisms to achieve larger body sizes and faster locomotion to navigate these harsh conditions, such as by forming chains or clusters that improved propulsion against increased water viscosity.[57] Fossil evidence from post-glacial deposits supports this, showing early multicellular eukaryotes appearing shortly after deglaciation, when nutrient upwelling from melting ice may have amplified selective pressures for complex forms.[58] These glaciations thus acted as evolutionary bottlenecks, favoring adhesion and division of labor in aggregates that could better withstand resource scarcity and physical constraints. Biotic interactions, particularly the predation hypothesis, complement these abiotic drivers by highlighting how ecological arms races post-Snowball Earth intensified selection for multicellularity. Around 740–580 million years ago, the emergence of predatory protists created intense grazing pressure on unicellular prey, prompting evolutionary responses like cell clumping to evade engulfment.[59] Nicholas Butterfield's analysis of Neoproterozoic fossils suggests that this predator-prey dynamic, evident in trace fossils of bored or grazed eukaryotes, drove the aggregation of cells into protective multicellular groups, as evidenced by early multicellular forms such as the red alga Bangiomorpha pubescens dated to approximately 1.05 billion years ago. Integrating these factors, the combined effects of oxygenation, glaciation, and predation generated synergistic selective pressures: oxygen provided metabolic fuel for size increase, Snowball conditions demanded structural innovations for survival, and predators enforced rapid evolution of adhesion mechanisms, collectively paving the way for multicellular diversification during the Neoproterozoic era.[61]Experimental Studies

Laboratory Evolution Models

Laboratory evolution models utilize microbial organisms to experimentally recreate the transition from unicellular to multicellular life, providing controlled insights into the mechanisms driving aggregation and cooperation. These setups often draw inspiration from the colonial theory, which posits that multicellularity arose from loose aggregations of unicellular ancestors that gained selective advantages through clustering.[62] A prominent model employs the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to form "snowflake" clusters, where cells remain attached after division due to targeted genetic modifications. In these experiments, researchers knock out the ACE2 gene, which normally promotes cell separation post-division, leading to the formation of branching, multicellular clusters resembling snowflakes.[63] This system allows for the study of basic multicellular traits, such as size-dependent sedimentation, in a genetically tractable eukaryote.[64] Choanoflagellates, the closest living relatives to animals, serve as models for animal-like multicellularity through their natural ability to form colonies that mimic early metazoan structures. Experimental protocols involve culturing species like Salpingoeca rosetta, which form rosette-shaped colonies in response to environmental cues such as bacterial prey, to investigate adhesion and polarity establishment.[65] These setups use microfluidic devices or static cultures to observe colony formation and test factors influencing multicellular transitions.[66] In green algae, particularly Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as a precursor to the volvocine lineage, laboratory evolution models select for volvocine-like multicellularity by promoting cell adhesion and group formation. Protocols often involve mutagenizing unicellular strains and screening for mutants with enhanced extracellular matrix production or adhesion proteins, such as those in the pherophorins family.[67] Common techniques across these models include selection for settling or clustering in assays that impose predation pressure or gravitational settling. For instance, in yeast and algal systems, populations are subjected to predation by filter-feeding protists or centrifugation to favor faster-sinking aggregates, mimicking natural selection for larger group sizes.[62] These assays are conducted in liquid media where solitary cells settle slowly, while clusters descend rapidly, enabling differential survival.[68] Protocols typically rely on serial transfer cultures, where a small aliquot of the population (e.g., 1:100 dilution) is transferred to fresh medium every 24-48 hours, maintaining selection for large aggregates over hundreds of generations. Genetic markers, such as fluorescent tags or selectable adhesion mutants (e.g., FLO1 overexpression in yeast), facilitate tracking of clustering phenotypes and isolation of evolved strains.[67] In choanoflagellate models, transfers incorporate prey bacteria to sustain colony-inducing conditions.[65] Despite their utility, these laboratory models face limitations due to their compressed timescales, spanning only hundreds to thousands of generations compared to the millions of years required for natural multicellular evolution. This acceleration may overlook long-term genomic changes or ecological interactions that stabilize multicellularity in nature.[69] Additionally, the controlled environments simplify complex selective pressures, potentially limiting the generalizability to diverse evolutionary contexts.[42]Key Experimental Findings

Experimental evolution of multicellularity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae under settling selection has demonstrated rapid emergence of clustered forms. In replicate populations subjected to daily transfers favoring faster sedimentation, snowflake-like multicellular clusters evolved within approximately 60 generations, consistently across all lines in multiple independent experiments. This transition occurred through mutations preventing complete mother-daughter cell separation after division, leading to branched aggregates of up to thousands of cells that settle significantly faster than unicellular ancestors.[62] A key outcome of this multicellularity is the suppression of selfish cheater mutants, which exploit cooperative cells but reduce overall group fitness. In snowflake yeast, the life cycle features a single-cell bottleneck during reproduction, where clusters propagate by fission into daughter groups; this structure limits cheater invasion because size-based selection favors larger, cooperative clusters over those compromised by non-adhesive or exploitative mutants, effectively reducing their frequency over generations.[64] Division of labor also arose quickly in these evolving clusters, enhancing multicellular functionality. In elongated snowflake aggregates, posterior cells specialized in reproduction by forming propagules that mediate cluster fission, while anterior cells maintained structural integrity through viability and growth support, allowing efficient dispersal and survival under selection.[62] Further findings highlight molecular and ecological drivers: adhesion-related genes, such as those involved in cell wall integrity and separation, upregulated rapidly to stabilize clusters, occurring within the initial generations of selection. Additionally, multicellularity evolved even faster when predation by predators like the rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus was introduced, with clustered forms providing a defensive size advantage and emerging in under 100 generations compared to longer timelines without predators.[62][5]Recent Advances (2023-2025)

In 2023, experimental studies demonstrated that interspecific competition between two yeast species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces lactis, promotes the de novo evolution of multicellularity in K. lactis. When co-cultured, K. lactis rapidly evolved larger cell clusters as an adaptive response to competitive pressures from S. cerevisiae, which outcompeted unicellular K. lactis for resources; this shift to multicellular aggregates enhanced survival and resource acquisition in mixed populations.[70] The findings highlight how multispecies interactions, including exploitative competition akin to predation dynamics, can drive the transition to multicellularity by favoring group-level adaptations over solitary growth. Advancing this understanding, research in 2025 revealed that abiotic stresses such as periodic drought or antibiotic exposure can trigger the evolution of multicellularity and cell differentiation in unicellular organisms. Mathematical models and simulations showed that under repeated stress cycles, populations initially evolve stress-resistant unicellular traits but subsequently transition to multicellular forms with specialized cell types, improving overall group resilience; for instance, drought selects for aggregated structures that retain moisture, while antibiotics favor differentiated propagules for dispersal.[71] These stress-induced pathways provide a mechanistic link between environmental pressures and the emergence of complexity, distinct from biotic drivers like predation.[71] In 2025, investigations into animal evolution uncovered how cytokinesis—the process of cell division—was repurposed from a unicellular toolkit to enable organized tissue formation in early metazoans. Comparative genomic and functional analyses across choanoflagellates (closest unicellular relatives to animals) and basal animals revealed that animals refined centralspindlin and Ect2 regulatory proteins to incomplete cytokinesis, allowing daughter cells to remain connected and form epithelial-like sheets; this innovation, absent in non-animal lineages, facilitated the transition from loose colonies to cohesive multicellular bodies approximately 600 million years ago.[72][73] Complementing these insights, a 2024 study on proteostatic mechanisms showed that tuning protein homeostasis (proteostasis) enables the rapid evolution of novel multicellular traits, such as cellular elongation, in experimentally evolved lineages. In long-term evolution experiments with budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), mutations in chaperones like Hsp90 altered protein folding networks, promoting elongated cell shapes that increased cluster size and mechanical strength without requiring new genes; this tuning of ancient proteostatic systems thus scaffolds biophysical adaptations central to multicellular diversification.[74] Although focused on yeast, the principles suggest similar repurposing in choanoflagellates, where elongation supports colonial forms predating animal multicellularity.[74] Finally, computational simulations in 2023 illustrated how "selfish multicellularity"—where individual cells prioritize personal regulatory strategies within groups—fundamentally alters cell competition dynamics during the origins of multicellularity. Evolving virtual cell populations under group-selection pressures showed that multicellularity constrains intra-group competition by synchronizing behaviors, reducing the spread of selfish cheaters and stabilizing cooperative aggregates; however, it amplifies inter-group rivalry, driving faster evolution of collective traits like adhesion.[75] This framework underscores the tension between individual and group-level selection in nascent multicellular systems.[75]Advantages

Survival and Ecological Benefits

Multicellular organisms achieve significantly larger body sizes compared to their unicellular counterparts, conferring key survival advantages such as enhanced resistance to predation. By increasing in size, multicellular forms can evade microscopic predators like ciliates and rotifers that readily consume smaller unicellular prey, thereby improving overall fitness in predator-rich environments.[76] This size escalation also bolsters tolerance to environmental stresses, including desiccation and physical perturbations, as aggregated cells form protective structures that maintain internal hydration and structural integrity during adverse conditions.[10][77] Beyond physical protection, larger multicellular size facilitates superior access to resources by overcoming diffusion limitations inherent to unicellular life. In unicellular organisms, nutrient and oxygen uptake is constrained by surface-to-volume ratios, restricting growth beyond a few millimeters; multicellularity enables emergent mechanisms, such as metabolically driven flows, to transport nutrients efficiently across greater distances within the organism.[78] This adaptation not only supports sustained growth but also enhances competitive ability for scarce resources in nutrient-limited habitats.[10] The division of labor among specialized cells further amplifies survival efficiency in multicellular organisms. By allocating distinct roles—such as motility in somatic cells for foraging and reproduction in germline cells—organisms optimize resource utilization and energy allocation, leading to higher overall productivity compared to uniform unicellular strategies.[79][80] This specialization improves ecological performance, allowing multicellular groups to exploit diverse niches more effectively than solitary cells.[6] Ecologically, multicellularity has driven accelerated evolution toward greater complexity, enabling dominance in post-Cambrian ecosystems. The transition facilitated rapid diversification through expanded food webs and adaptive radiations, as seen in the Late Precambrian breakthrough where multicellular herbivores and carnivores co-evolved, breaking resource barriers and promoting complex trophic interactions.[81] Quantitatively, multicellular forms exhibit metabolic rates per unit biomass that are over ten-fold higher than those in unicellular species of comparable size, reflecting the elevated energetic demands and efficiencies of coordinated cellular activities.[82]Functional Specialization

In multicellular organisms, functional specialization arises through the differentiation of cells into distinct types, primarily somatic cells dedicated to structural support and maintenance, and germ cells focused on reproduction. Somatic cells, such as those forming supportive tissues like connective or epithelial layers, perform non-reproductive roles that sustain the organism's overall integrity and functionality.[83] In contrast, germ cells are specialized for generating gametes, ensuring the transmission of genetic material across generations, a division that enhances the organism's reproductive efficiency by segregating these essential tasks.[84] This basic dichotomy forms the foundation of more advanced multicellular architectures. Coordination among specialized cells is achieved through intercellular signaling pathways, which allow cells to communicate and integrate their functions effectively. Signaling molecules, often mediated by cell surface receptors and the extracellular matrix, enable somatic cells to respond to positional cues and environmental inputs, fostering organized tissue development.[83] For instance, integrin proteins in cell junctions relay information from the matrix to the nucleus, guiding cells in forming cohesive units that operate in unison. The resulting complexity from such specialization permits the evolution of organs tailored to specific physiological demands, vastly expanding the organism's capabilities beyond those of unicellular life. Neurons enable sensory perception and rapid information processing, digestive epithelia facilitate nutrient breakdown and absorption, and muscle cells drive locomotion and mechanical work.[83] This organ-level integration allows for efficient division of labor, where specialized tissues collaborate to perform multifaceted tasks that a single cell type could not achieve alone. Evolutionarily, functional specialization confers greater adaptability to multicellular organisms by enabling tailored responses to diverse challenges, as seen in the animal immune system where distinct leukocyte types, such as T cells for targeted cytotoxicity and B cells for antibody production, provide robust defense against pathogens.[85] Such specialization drives the transition from unicellular groups to integrated individuals by optimizing task allocation, thereby enhancing overall fitness in variable environments.[86] However, this comes with trade-offs, including elevated energy costs for maintaining differentiated states and intercellular communication, which are offset by gains in efficiency, such as improved resource allocation and reduced redundancy in function.[87]Challenges

Intercellular Conflicts and Cancer

In multicellular organisms, intercellular conflicts arise when individual cells prioritize their own proliferation over the cooperative needs of the whole organism, echoing competitive dynamics from unicellular ancestors. These "cheater" cells exploit the cooperative framework established during the evolution of multicellularity, where cells typically suppress selfish behaviors to benefit the group. Cancer represents a prime example of such cheating, as malignant cells proliferate uncontrollably, disrupting tissue architecture and organismal fitness at the expense of surrounding healthy cells. This behavior parallels social cheating in microbial populations, where mutants gain fitness advantages by avoiding cooperative costs like resource sharing or programmed cell death.[88] The atavistic theory posits that cancer emerges from the reactivation of ancient genetic programs retained from unicellular progenitors, effectively reverting cells to a pre-multicellular state. In this view, oncogenic transformations disable multicellular-specific controls, such as regulated apoptosis and contact inhibition, allowing cells to resume unicellular-like survival strategies including uncontrolled division and migration. For instance, suppression of apoptosis—a mechanism evolved in multicellular lineages to eliminate defective cells for group benefit—enables cancer cells to evade death signals that would otherwise limit their expansion. This regression is not merely a failure of modern regulation but a throwback to robust, ancestral pathways that prioritize individual survival over collective organization.[89][90] From an evolutionary perspective, the persistent threat of intercellular conflicts like cancer has likely driven the selection of adaptive mechanisms, including tumor suppressor genes that enforce cellular cooperation. The p53 gene, often called the "guardian of the genome," exemplifies this, as it detects DNA damage and aberrant proliferation—hallmarks of cheating cells—and triggers responses like cell cycle arrest or apoptosis to protect multicellular integrity. Evidence suggests that p53's tumor-suppressive functions expanded during the transition to multicellularity, with cancer pressures selecting for enhanced variants that balance proliferation control against risks in larger, more complex bodies. In species like elephants, multiple p53 copies correlate with lower cancer rates, illustrating how such adaptations mitigate evolutionary trade-offs imposed by multicellularity.[91][92] Cancer prevalence varies with multicellular complexity, remaining rare in simple multicellular forms like colonial algae due to fewer cells and less specialized tissues, which limit opportunities for cheater emergence. In contrast, complex multicellular organisms, with trillions of cells and intricate divisions of labor, face exponentially higher risks, as the sheer number of divisions increases mutation accumulation and conflict potential. This scaling effect underlies observations that neoplasia is infrequent in basal multicellular lineages but escalates in advanced vertebrates, where body size and longevity amplify the challenge despite evolved safeguards.[88][93]Germ-Soma Separation

The germ-soma separation, often referred to as the Weismann barrier, delineates a fundamental distinction in multicellular organisms between somatic cells, which perform non-reproductive functions and are mortal, and germ cells, which are dedicated to reproduction and maintain potential immortality across generations. Proposed by August Weismann in his 1892 treatise Das Keimplasma, this concept posits that hereditary material is confined to the germ line, preventing somatic modifications from being inherited and ensuring the continuity of the germ plasm as the sole carrier of inheritance.[94] Weismann's theory emphasized that somatic cells serve the organism's survival and reproduction but do not transmit their genetic changes, thereby isolating the germline from somatic wear and tear.[95] This separation evolved subsequent to the emergence of multicellularity, primarily as a mechanism to mitigate conflicts arising from mutations in somatic cells that could otherwise infiltrate the germline and propagate deleterious effects to offspring. In evolutionary terms, it arose to stabilize the organism level of selection by suppressing intra-organismal competition between cell lineages, as detailed in Leo Buss's analysis of developmental hierarchies. By sequestering the germline early or late in development, multicellular lineages could prioritize organismal fitness over cellular autonomy, a transition facilitated in various eukaryotic clades independently.[96] Empirical evidence for the germ-soma separation is robust in complex multicellular taxa, including animals where the germline is typically specified early during embryogenesis, rendering somatic cells incapable of contributing to the next generation. In plants, a similar but delayed segregation occurs, with germline precursors arising late from somatic tissues during reproductive development, yet still enforcing a functional barrier against somatic inheritance.[97] Conversely, this strict separation is absent in simpler multicellular forms, such as the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum, where all cells retain totipotency and can differentiate into either reproductive spores or sterile stalk cells without a dedicated germline.[98] The establishment of the germ-soma divide has profound implications for organismal biology, notably underpinning the disposable soma theory of aging proposed by Thomas Kirkwood. This theory argues that resources are allocated preferentially to germline maintenance for reproductive success, treating the soma as expendable and leading to progressive deterioration over time due to underinvestment in somatic repair.[95] By isolating the immortal germline, the barrier allows for such trade-offs, explaining why aging manifests in multicellular organisms as an adaptive consequence of evolutionary pressures favoring reproduction over indefinite somatic longevity.Molecular and Genetic Basis

Gene Expression Shifts