Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

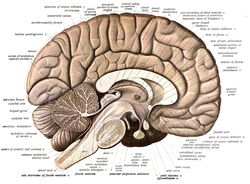

Neuroanatomy

View on Wikipedia

Neuroanatomy is a branch of neuroscience that studies the structure and organization of the nervous system. In contrast to animals with radial symmetry, whose nervous system consists of a distributed network of cells, animals with bilateral symmetry have segregated, defined nervous systems. Their neuroanatomy is therefore better understood. In vertebrates, the nervous system is segregated into the central nervous system (CNS) comprising the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) comprising the connecting nerves between them. Much of what has informed neuroscientists has come from observing how lesions (damage) to specific brain areas affects behavior or other neural functions.

For information about the composition of non-human animal nervous systems, see nervous system. For information about the typical structure of the human nervous system, see human brain, and peripheral nervous system.

History

[edit]

The first known written record of a study of the anatomy of the human brain is an ancient Egyptian document, the Edwin Smith Papyrus.[1] In Ancient Greece, interest in the brain began with the work of Alcmaeon, who appeared to have dissected the eye and related the brain to vision. He also suggested that the brain, not the heart, was the organ that ruled the body (what Stoics would call the hegemonikon) and that the senses were dependent on the brain.[2]

The debate regarding the hegemonikon persisted among ancient Greek philosophers and physicians for a very long time.[3] Those who argued for the brain often contributed to the understanding of neuroanatomy as well. Herophilus and Erasistratus of Alexandria were perhaps the most influential with their studies involving dissecting human brains, affirming the distinction between the cerebrum and the cerebellum, and identifying the ventricles and the dura mater.[4][5] The Greek physician and philosopher Galen, likewise, argued strongly for the brain as the organ responsible for sensation and voluntary motion, as evidenced by his research on the neuroanatomy of oxen, Barbary apes, and other animals.[3][6]

The cultural taboo on human dissection continued for several hundred years afterward, which brought no major progress in the understanding of the anatomy of the brain or of the nervous system. However, Pope Sixtus IV effectively revitalized the study of neuroanatomy by altering the papal policy and allowing human dissection. This resulted in a flush of new activity by artists and scientists of the Renaissance,[7] such as Mondino de Luzzi, Berengario da Carpi, and Jacques Dubois, and culminating in the work of Andreas Vesalius.[8][9]

In 1664, Thomas Willis, a physician and professor at Oxford University, coined the term neurology when he published his text Cerebri Anatome which is considered the foundation of modern neuroanatomy.[10] The subsequent three hundred and fifty some years has produced a great deal of documentation and study of the neural system.

Composition

[edit]At the tissue level, the nervous system is composed of neurons, glial cells, and extracellular matrix. Both neurons and glial cells come in many types (see, for example, the nervous system section of the list of distinct cell types in the adult human body). Neurons are the information-processing cells of the nervous system: they sense our environment, communicate with each other via electrical signals and chemicals called neurotransmitters which generally act across synapses (close contacts between two neurons, or between a neuron and a muscle cell; note also extrasynaptic effects are possible, as well as release of neurotransmitters into the neural extracellular space), and produce our memories, thoughts, and movements. Glial cells maintain homeostasis, produce myelin (oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells), and provide support and protection for the brain's neurons. Some glial cells (astrocytes) can even propagate intercellular calcium waves over long distances in response to stimulation, and release gliotransmitters in response to changes in calcium concentration. Wound scars in the brain largely contain astrocytes. The extracellular matrix also provides support on the molecular level for the brain's cells, vehiculating substances to and from the blood vessels.

At the organ level, the nervous system is composed of brain regions, such as the hippocampus in mammals or the mushroom bodies of the fruit fly.[11] These regions are often modular and serve a particular role within the general systemic pathways of the nervous system. For example, the hippocampus is critical for forming memories in connection with many other cerebral regions. The peripheral nervous system also contains afferent or efferent nerves, which are bundles of fibers that originate from the brain and spinal cord, or from sensory or motor sorts of peripheral ganglia, and branch repeatedly to innervate every part of the body. Nerves are made primarily of the axons or dendrites of neurons (axons in case of efferent motor fibres, and dendrites in case of afferent sensory fibres of the nerves), along with a variety of membranes that wrap around and segregate them into nerve fascicles.

The vertebrate nervous system is divided into the central and peripheral nervous systems. The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain, retina, and spinal cord, while the peripheral nervous system (PNS) is made up of all the nerves and ganglia (packets of peripheral neurons) outside of the CNS that connect it to the rest of the body. The PNS is further subdivided into the somatic and autonomic nervous systems. The somatic nervous system is made up of "afferent" neurons, which bring sensory information from the somatic (body) sense organs to the CNS, and "efferent" neurons, which carry motor instructions out to the voluntary muscles of the body. The autonomic nervous system can work with or without the control of the CNS (that's why it is called 'autonomous'), and also has two subdivisions, called sympathetic and parasympathetic, which are important for transmitting motor orders to the body's basic internal organs, thus controlling functions such as heartbeat, breathing, digestion, and salivation. Autonomic nerves, unlike somatic nerves, contain only efferent fibers. Sensory signals coming from the viscera course into the CNS through the somatic sensory nerves (e.g., visceral pain), or through some particular cranial nerves (e.g., chemosensitive or mechanic signals).

Orientation in neuroanatomy

[edit]

In anatomy in general and neuroanatomy in particular, several sets of topographic terms are used to denote orientation and location, which are generally referred to the body or brain axis. The axis of the CNS is often wrongly assumed to be more or less straight, but it actually shows always two ventral flexures (cervical and cephalic flexures) and a dorsal flexure (pontine flexure), all due to differential growth during embryogenesis. The pairs of terms used most commonly in neuroanatomy are:

- Dorsal and ventral: Dorsal refers more or less to the top or upper side of the brain, which is symbolized by the floor plate, and ventral to the bottom or lower side. These descriptors originally were used for dorsum and ventrum – back and belly – of the body; the belly of most animals is oriented towards the ground; the erect posture of humans places our ventral aspect anteriorly, and the dorsal aspect becomes posterior. The case of the head and the brain is peculiar, since the belly does not properly extend into the head, unless we assume that the mouth represents an extended belly element. Therefore, in common use, those brain parts that lie close to the base of the cranium, and through it to the mouth cavity, are called ventral – i.e., at its bottom or lower side, as defined above – whereas dorsal parts are closer to the enclosing cranial vault. Reference to the roof and floor plates of the brain is less prone to confusion, also allow us to keep an eye on the axial flexures mentioned above. Dorsal and ventral are thus relative terms in the brain, whose exact meaning depends on the specific location.

- Rostral and caudal: rostral refers in general anatomy to the front of the body (towards the nose, or rostrum in Latin), and caudal refers to the tail end of the body (towards the tail; cauda in Latin). The rostrocaudal dimension of the brain corresponds to its length axis, which runs across the cited flexures from the caudal tip of the spinal cord into a rostral end roughly at the optic chiasma. In the erect Man, the directional terms "superior" and "inferior" essentially refer to this rostrocaudal dimension, because our body and brain axes are roughly oriented vertically in the erect position. However, all vertebrates develop a very marked ventral kink in the neural tube that is still detectable in the adult central nervous system, known as the cephalic flexure. The latter bends the rostral part of the CNS at a 180-degree angle relative to the caudal part, at the transition between the forebrain (axis ending rostrally at the optic chiasma) and the brainstem and spinal cord (axis roughly vertical, but including additional minor kinks at the pontine and cervical flexures) These flexural changes in axial dimension are problematic when trying to describe relative position and sectioning planes in the brain. There is abundant literature that wrongly disregards the axial flexures and assumes a relatively straight brain axis.

- Medial and lateral: medial refers to being close, or relatively closer, to the midline (the descriptor median means a position precisely at the midline). Lateral is the opposite (a position more or less separated away from the midline).

Note that such descriptors (dorsal/ventral, rostral/caudal; medial/lateral) are relative rather than absolute (e.g., a lateral structure may be said to lie medial to something else that lies even more laterally).

Commonly used terms for planes of orientation or planes of section in neuroanatomy are "sagittal", "transverse" or "coronal", and "axial" or "horizontal". Again in this case, the situation is different for swimming, creeping or quadrupedal (prone) animals than for Man, or other erect species, due to the changed position of the axis. Due to the axial brain flexures, no section plane ever achieves a complete section series in a selected plane, because some sections inevitably result cut oblique or even perpendicular to it, as they pass through the flexures. Experience allows to discern the portions that result cut as desired.

- A mid-sagittal plane divides the body and brain into left and right halves; sagittal sections, in general, are parallel to this median plane, moving along the medial-lateral dimension (see the image above). The term sagittal refers etymologically to the median suture between the right and left parietal bones of the cranium, known classically as sagittal suture, because it looks roughly like an arrow by its confluence with other sutures (sagitta; arrow in Latin).

- A section plane orthogonal to the axis of any elongated form in principle is held to be transverse (e.g., a transverse section of a finger or of the vertebral column); if there is no length axis, there is no way to define such sections, or there are infinite possibilities. Therefore, transverse body sections in vertebrates are parallel to the ribs, which are orthogonal to the vertebral column, which represents the body axis both in animals and man. The brain also has an intrinsic longitudinal axis – that of the primordial elongated neural tube – which becomes largely vertical with the erect posture of Man, similarly as the body axis, except at its rostral end, as commented above. This explains that transverse spinal cord sections are roughly parallel to our ribs, or to the ground. However, this is only true for the spinal cord and the brainstem, since the forebrain end of the neural axis bends crook-like during early morphogenesis into the chiasmatic hypothalamus, where it ends; the orientation of true transverse sections accordingly changes, and is no longer parallel to the ribs and ground, but perpendicular to them; lack of awareness of this morphologic brain peculiarity (present in all vertebrate brains without exceptions) has caused and still causes much erroneous thinking on forebrain brain parts. Acknowledging the singularity of rostral transverse sections, tradition has introduced a different descriptor for them, namely coronal sections. Coronal sections divide the forebrain from rostral (front) to caudal (back), forming a series orthogonal (transverse) to the local bent axis. The concept cannot be applied meaningfully to the brainstem and spinal cord, since there the coronal sections become horizontal to the axial dimension, being parallel to the axis. In any case, the concept of 'coronal' sections is less precise than that of 'transverse', since often coronal section planes are used which are not truly orthogonal to the rostral end of the brain axis. The term is etymologically related to the coronal suture of the cranium and this to the position where crowns are worn (Latin corona means crown). It is not clear what sort of crown was meant originally (maybe just a diadema), and this leads unfortunately to ambiguity in the section plane defined merely as coronal.

- A coronal plane across the human head and brain is modernly conceived to be parallel to the face (the plane in which a king's crown sits on his head is not exactly parallel to the face, and exportation of the concept to less frontally endowed animals than us is obviously even more conflictive, but there is an implicit reference to the coronal suture of the cranium, which forms between the frontal and temporal/parietal bones, giving a sort of diadema configuration which is roughly parallel to the face). Coronal section planes thus essentially refer only to the head and brain, where a diadema makes sense, and not to the neck and body below.

- Horizontal sections by definition are aligned (parallel) with the horizon. In swimming, creeping and quadrupedal animals the body axis itself is horizontal, and, thus, horizontal sections run along the length of the spinal cord, separating ventral from dorsal parts. Horizontal sections are orthogonal to both transverse and sagittal sections, and in theory, are parallel to the length axis. Due to the axial bend in the brain (forebrain), true horizontal sections in that region are orthogonal to coronal (transverse) sections (as is the horizon relative to the face).

According to these considerations, the three directions of space are represented precisely by the sagittal, transverse and horizontal planes, whereas coronal sections can be transverse, oblique or horizontal, depending on how they relate to the brain axis and its incurvations.

Tools

[edit]Modern developments in neuroanatomy are directly correlated to the technologies used to perform research. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the various tools that are available. Many of the histological techniques used to study other tissues can be applied to the nervous system as well. However, there are some techniques that have been developed especially for the study of neuroanatomy.

Cell staining

[edit]In biological systems, staining is a technique used to enhance the contrast of particular features in microscopic images.

Nissl staining uses aniline basic dyes to intensely stain the acidic polyribosomes in the rough endoplasmic reticulum, which is abundant in neurons. This allows researchers to distinguish between different cell types (such as neurons and glia), and neuronal shapes and sizes, in various regions of the nervous system cytoarchitecture.

The classic Golgi stain uses potassium dichromate and silver nitrate to fill selectively with a silver chromate precipitate a few neural cells (neurons or glia, but in principle, any cells can react similarly). This so-called silver chromate impregnation procedure stains entirely or partially the cell bodies and neurites of some neurons -dendrites, axon- in brown and black, allowing researchers to trace their paths up to their thinnest terminal branches in a slice of nervous tissue, thanks to the transparency consequent to the lack of staining in the majority of surrounding cells. Modernly, Golgi-impregnated material has been adapted for electron-microscopic visualization of the unstained elements surrounding the stained processes and cell bodies, thus adding further resolutive power.

Histochemistry

[edit]Histochemistry uses knowledge about biochemical reaction properties of the chemical constituents of the brain (including notably enzymes) to apply selective methods of reaction to visualize where they occur in the brain and any functional or pathological changes. This applies importantly to molecules related to neurotransmitter production and metabolism, but applies likewise in many other directions chemoarchitecture, or chemical neuroanatomy.

Immunocytochemistry is a special case of histochemistry that uses selective antibodies against a variety of chemical epitopes of the nervous system to selectively stain particular cell types, axonal fascicles, neuropiles, glial processes or blood vessels, or specific intracytoplasmic or intranuclear proteins and other immunogenetic molecules, e.g., neurotransmitters. Immunoreacted transcription factor proteins reveal genomic readout in terms of translated protein. This immensely increases the capacity of researchers to distinguish between different cell types (such as neurons and glia) in various regions of the nervous system.

In situ hybridization uses synthetic RNA probes that attach (hybridize) selectively to complementary mRNA transcripts of DNA exons in the cytoplasm, to visualize genomic readout, that is, distinguish active gene expression, in terms of mRNA rather than protein. This allows identification histologically (in situ) of the cells involved in the production of genetically-coded molecules, which often represent differentiation or functional traits, as well as the molecular boundaries separating distinct brain domains or cell populations.

Genetically encoded markers

[edit]By expressing variable amounts of red, green, and blue fluorescent proteins in the brain, the so-called "brainbow" mutant mouse allows the combinatorial visualization of many different colors in neurons. This tags neurons with enough unique colors that they can often be distinguished from their neighbors with fluorescence microscopy, enabling researchers to map the local connections or mutual arrangement (tiling) between neurons.

Optogenetics uses transgenic constitutive and site-specific expression (normally in mice) of blocked markers that can be activated selectively by illumination with a light beam. This allows researchers to study axonal connectivity in the nervous system in a very discriminative way.

Non-invasive brain imaging

[edit]Magnetic resonance imaging has been used extensively to investigate brain structure and function non-invasively in healthy human subjects. An important example is diffusion tensor imaging, which relies on the restricted diffusion of water in tissue in order to produce axon images. In particular, water moves more quickly along the direction aligned with the axons, permitting the inference of their structure.

Viral-based methods

[edit]Certain viruses can replicate in brain cells and cross synapses. So, viruses modified to express markers (such as fluorescent proteins) can be used to trace connectivity between brain regions across multiple synapses.[12] Two tracer viruses which replicate and spread transneuronal/transsynaptic are the Herpes simplex virus type1 (HSV)[13] and the Rhabdoviruses.[14] Herpes simplex virus was used to trace the connections between the brain and the stomach, in order to examine the brain areas involved in viscero-sensory processing.[15] Another study injected herpes simplex virus into the eye, thus allowing the visualization of the optical pathway from the retina into the visual system.[16] An example of a tracer virus which replicates from the synapse to the soma is the pseudorabies virus.[17] By using pseudorabies viruses with different fluorescent reporters, dual infection models can parse complex synaptic architecture.[18]

Dye-based methods

[edit]Axonal transport methods use a variety of dyes (horseradish peroxidase variants, fluorescent or radioactive markers, lectins, dextrans) that are more or less avidly absorbed by neurons or their processes. These molecules are selectively transported anterogradely (from soma to axon terminals) or retrogradely (from axon terminals to soma), thus providing evidence of primary and collateral connections in the brain. These 'physiologic' methods (because properties of living, unlesioned cells are used) can be combined with other procedures, and have essentially superseded the earlier procedures studying degeneration of lesioned neurons or axons. Detailed synaptic connections can be determined by correlative electron microscopy.

Connectomics

[edit]Serial section electron microscopy has been extensively developed for use in studying nervous systems. For example, the first application of serial block-face scanning electron microscopy was on rodent cortical tissue.[19] Circuit reconstruction from data produced by this high-throughput method is challenging, and the Citizen science game EyeWire has been developed to aid research in that area. Nevertheless, complete connectomes of some model organisms have been obtained (see below).

Computational neuroanatomy

[edit]Is a field that utilizes various imaging modalities and computational techniques to model and quantify the spatiotemporal dynamics of neuroanatomical structures in both normal and clinical populations.[20]

Model systems

[edit]Aside from the human brain, there are many other animals whose brains and nervous systems have received extensive study as model systems, including mice, zebrafish,[21] fruit fly,[22] and a species of roundworm called C. elegans. Each of these has its own advantages and disadvantages as a model system. For example, the C. elegans nervous system is extremely stereotyped from one individual worm to the next. This has allowed researchers using electron microscopy to map the paths and connections of all of the 302 neurons in this species. The fruit fly is widely studied in part because its genetics is very well understood and easily manipulated. The mouse is used because, as a mammal, its brain is more similar in structure to our own (e.g., it has a six-layered cortex, yet its genes can be easily modified and its reproductive cycle is relatively fast).

Caenorhabditis elegans

[edit]

The brain is small and simple in some species, such as the nematode worm, where the body plan is quite simple: a tube with a hollow gut cavity running from the mouth to the anus, and a nerve cord with an enlargement (a ganglion) for each body segment, with an especially large ganglion at the front, called the brain. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has been studied because of its importance in genetics.[23] In the early 1970s, Sydney Brenner chose it as a model system for studying the way that genes control development, including neuronal development. One advantage of working with this worm is that the nervous system of the hermaphrodite contains exactly 302 neurons, always in the same places, making identical synaptic connections in every worm.[24] Brenner's team sliced worms into thousands of ultrathin sections and photographed every section under an electron microscope, then visually matched fibers from section to section, to map out every neuron and synapse in the entire body, to give a complete connectome of the nematode.[25]

Drosophila melanogaster

[edit]Drosophila melanogaster is a popular experimental animal because it is easily cultured en masse from the wild, has a short generation time, and mutant animals are readily obtainable.

Arthropods have a central brain with three divisions and large optical lobes behind each eye for visual processing. The brain of a fruit fly contains several million synapses, compared to at least 100 billion in the human brain. Approximately two-thirds of the Drosophila brain is dedicated to visual processing.

Thomas Hunt Morgan started to work with Drosophila in 1906, and this work earned him the 1933 Nobel Prize in Medicine for identifying chromosomes as the vector of inheritance for genes. Because of the large array of tools available for studying Drosophila genetics, they have been a natural subject for studying the role of genes in the nervous system.[26] The genome has been sequenced and published in 2000. About 75% of known human disease genes have a recognizable match in the genome of fruit flies. Drosophila is being used as a genetic model for several human neurological diseases including the neurodegenerative disorders Parkinson's, Huntington's, spinocerebellar ataxia and Alzheimer's disease. In spite of the large evolutionary distance between insects and mammals, many basic aspects of Drosophila neurogenetics have turned out to be relevant to humans. For instance, the first biological clock genes were identified by examining Drosophila mutants that showed disrupted daily activity cycles.[27]

In 2024, a complete connectome of adult female fruit fly brain was obtained and published.[28][29]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Atta, H. M. (1999). "Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: The Oldest Known Surgical Treatise". American Surgeon. 65 (12): 1190–1192. doi:10.1177/000313489906501222. PMID 10597074. S2CID 30179363.

- ^ Rose, F (2009). "Cerebral Localization in Antiquity". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 18 (3): 239–247. doi:10.1080/09647040802025052. PMID 20183203. S2CID 5195450.

- ^ a b Rocca, J. (2003). Galen on the Brain: Anatomical Knowledge and Physiological Speculation in the Second Century AD. Studies in Ancient Medicine. Vol. 26. Brill. pp. 1–313. ISBN 978-90-474-0143-8. PMID 12848196.

- ^ Potter, P. (1976). "Herophilus of Chalcedon: An assessment of his place in the history of anatomy". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 50 (1): 45–60. ISSN 0007-5140. JSTOR 44450313. PMID 769875.

- ^ Reveron, R. R. (2014). "Herophilus and Erasistratus, pioneers of human anatomical dissection". Vesalius: Acta Internationales Historiae Medicinae. 20 (1): 55–58. PMID 25181783.

- ^ Ajita, R. (2015). "Galen and his contribution to anatomy: a review". Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences. 4 (26): 4509–4517. doi:10.14260/jemds/2015/651.

- ^ Ginn, S. R.; Lorusso, L. (2008). "Brain, Mind, and Body: Interactions with Art in Renaissance Italy". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 17 (3): 295–313. doi:10.1080/09647040701575900. PMID 18629698. S2CID 35600367.

- ^ Markatos, K.; Chytas, D.; Tsakotos, G.; Karamanou, M.; Piagkou, M.; Mazarakis, A.; Johnson, E. (2020). "Andreas Vesalius of Brussels (1514–1564): his contribution to the field of functional neuroanatomy and the criticism to his predecessors". Acta Chirurgica Belgica. 120 (6): 437–441. doi:10.1080/00015458.2020.1759887. PMID 32345153. S2CID 216647830.

- ^ Splavski, B. (2019). "Andreas Vesalius, the Predecessor of Neurosurgery: How his Progressive Scientific Achievements Affected his Professional Life and Destiny". World Neurosurgery. 129: 202–209. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.06.008. PMID 31201946. S2CID 189897890.

- ^ Neher, A (2009). "Christopher Wren, Thomas Willis and the Depiction of the Brain and Nerves". Journal of Medical Humanities. 30 (3): 191–200. doi:10.1007/s10912-009-9085-5. PMID 19633935. S2CID 11121186.

- ^ Mushroom Bodies of the Fruit Fly Archived 2012-07-16 at archive.today

- ^ Ginger, M.; Haberl, M.; Conzelmann, K.-K.; Schwarz, M.; Frick, A. (2013). "Revealing the secrets of neuronal circuits with recombinant rabies virus technology". Front. Neural Circuits. 7: 2. doi:10.3389/fncir.2013.00002. PMC 3553424. PMID 23355811.

- ^ McGovern, AE; Davis-Poynter, N; Rakoczy, J; Phipps, S; Simmons, DG; Mazzone, SB (2012). "Anterograde neuronal circuit tracing using a genetically modified herpes simplex virus expressing EGFP". J Neurosci Methods. 209 (1): 158–67. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.05.035. PMID 22687938. S2CID 20370171.

- ^ Kuypers HG, Ugolini G (February 1990). "Viruses as transneuronal tracers". Trends in Neurosciences. 13 (2): 71–5. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(90)90071-H. PMID 1690933. S2CID 27938628.

- ^ Rinaman L, Schwartz G (March 2004). "Anterograde transneuronal viral tracing of central viscerosensory pathways in rats". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (11): 2782–6. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5329-03.2004. PMC 6729508. PMID 15028771.

- ^ Norgren RB, McLean JH, Bubel HC, Wander A, Bernstein DI, Lehman MN (March 1992). "Anterograde transport of HSV-1 and HSV-2 in the visual system". Brain Research Bulletin. 28 (3): 393–9. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(92)90038-Y. PMID 1317240. S2CID 4701001.

- ^ Card, J. P. (2001). "Pseudorabies virus neuroinvasiveness: A window into the functional organization of the brain". Advances in Virus Research. 56: 39–71. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(01)56004-2. ISBN 978-0-12-039856-0. PMID 11450308.

- ^ Card, J. P. (2011). "A Dual Infection Pseudorabies Virus Conditional Reporter Approach to Identify Projections to Collateralized Neurons in Complex Neural Circuits". PLOS ONE. 6 (6) e21141. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621141C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021141. PMC 3116869. PMID 21698154.

- ^ Denk, W; Horstmann, H (2004). "Serial Block-Face Scanning Electron Microscopy to Reconstruct Three-Dimensional Tissue Nanostructure". PLOS Biology. 2 (11) e329. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020329. PMC 524270. PMID 15514700.

- ^ Kędzia, Alicja; Derkowski, Wojciech (December 2024). "Modern methods of neuroanatomical and neurophysiological research". MethodsX. 13 102881. doi:10.1016/j.mex.2024.102881. PMC 11340600. PMID 39176151.

- ^ Wullimann, Mario F.; Rupp, Barbar; Reichert, Heinrich (1996). Neuroanatomy of the zebrafish brain: a topological atlas. Birkh[Ux9451]user Verlag. ISBN 3-7643-5120-9. Archived from the original on 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- ^ "Atlas of the Drosophila Brain". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ "WormBook: The online review of C. elegans biology". Archived from the original on 2011-10-11. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ^ Hobert, Oliver (2005). The C. elegans Research Community (ed.). "Specification of the nervous system". WormBook: 1–19. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.12.1. PMC 4781215. PMID 18050401. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- ^ White, JG; Southgate, E; Thomson, JN; Brenner, S (1986). "The Structure of the Nervous System of the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 314 (1165): 1–340. Bibcode:1986RSPTB.314....1W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. PMID 22462104.

- ^ "Flybrain: An online atlas and database of the drosophila nervous system". Archived from the original on 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ^ Konopka, RJ; Benzer, S (1971). "Clock Mutants of Drosophila melanogaster". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 68 (9): 2112–6. Bibcode:1971PNAS...68.2112K. doi:10.1073/pnas.68.9.2112. PMC 389363. PMID 5002428.

- ^ Dorkenwald, Sven; et al. (2024-10-02). "Neuronal wiring diagram of an adult brain". Nature. 634 (8032): 124–138. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07558-y. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 11446842. PMID 39358518.

- ^ Schlegel, Philipp; et al. (2024-10-02). "Whole-brain annotation and multi-connectome cell typing of Drosophila". Nature. 634 (8032): 139–152. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07686-5. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 11446831. PMID 39358521.

Sources

[edit]- Parent, André; Carpenter, Malcolm B. (1996). Carpenter's Human Neuroanatomy (9th ed.). Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-06752-1.

- Patestas, Maria A.; Gartner, Leslie P. (2016). A Textbook of Neuroanatomy (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-67746-9.

- Splittgerber, Ryan (2019). Snell's Clinical Neuroanatomy (8th ed.). Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4963-4675-9.

- Waxman, Stephen (2020). Clinical Neuroanatomy (29th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-260-45235-8.

External links

[edit]- Neuroanatomy, an annual journal of clinical neuroanatomy

- Mouse, Rat, Primate and Human Brain Atlases (UCLA Center for Computational Biology)

- brainmaps.org: High-Resolution Neuroanatomically-Annotated Brain Atlases

- BrainInfo for Neuroanatomy

- Brain Architecture Management System, several atlases of brain anatomy

- White Matter Atlas, Diffusion Tensor Imaging Atlas of the Brain's White Matter Tracts

Neuroanatomy

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Early Discoveries

The earliest recorded observations of the brain in neuroanatomy trace back to ancient Egypt, where the Edwin Smith Papyrus, dating to approximately 1600 BCE (a copy of an older text from around 3000 BCE), described head and spinal injuries, noting the brain's pulsatile nature and its role in causing symptoms like seizures and paralysis following trauma.[7] This document, the oldest known surgical treatise, recognized the brain as a distinct organ connected to the spinal cord but did not elaborate on deeper functional theories.[8] In ancient Greece, around 300 BCE, Herophilus of Chalcedon advanced these ideas through systematic human dissections in Alexandria, identifying key brain structures such as the meninges, four ventricles (with the fourth ventricle deemed most important for sensation), and at least seven pairs of cranial nerves.[9] He viewed the brain's ventricles as the seat of intelligence, soul, and mental functions, distinguishing the nervous system from other bodily networks and emphasizing its role in sensory processing.[10] In the 2nd century CE, Galen of Pergamon built on this foundation with extensive animal dissections, describing the brain as the origin of the senses—where the five sensory nerves (touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing) converged—and integrating it into humoral theory, positing that imbalances in the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, black bile) affected cerebral function and sensory perception.[11][12] Galen's ventricular model localized cognitive faculties across brain chambers, influencing medical thought for centuries.[13] The Renaissance marked a revival of empirical anatomy, exemplified by Andreas Vesalius's 1543 publication De humani corporis fabrica, which featured precise woodcut illustrations of the brain's gross structures, including sagittal sections revealing ventricles and cranial nerves, challenging Galenic errors through direct human cadaver dissections.[14] By the late 18th century, Félix Vicq d'Azyr's 1786 Traité d'anatomie et de physiologie provided the first detailed mappings of cerebral gyri and sulci, accurately delineating surface folds like the central sulcus (later named by others) and introducing terms such as "plis de passage" for interconnecting gyri, laying groundwork for cortical topography.[15][16] In the early 19th century, the Bell-Magendie law, independently formulated by Charles Bell (1811) and François Magendie (1822) and formalized around 1824, established that ventral spinal roots transmit motor impulses while dorsal roots convey sensory information, differentiating neural pathways through experimental sectioning in animals.[17][18] Mid-19th-century advancements shifted focus toward functional localization within the brain. In 1861, French physician Paul Broca identified the left inferior frontal gyrus (now known as Broca's area) as the center for speech production through postmortem examinations of patients with aphasia, providing early evidence for localized brain functions and challenging holistic views of cerebral activity.[19] Santiago Ramón y Cajal's work in the late 1880s and 1890s bridged these anatomical foundations to cellular neuroanatomy, using Golgi's staining method to demonstrate that neurons are discrete, independent cells rather than a fused network, with impulses flowing unidirectionally across junctions (later termed synapses), as articulated in his neuron doctrine.[20] This conceptualization, detailed in publications like La fine structure des centres nerveux (1890), revolutionized understanding of neural organization.[21]Modern Advances

The 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal for their pioneering work on the microscopic structure of the nervous system. Golgi's black reaction, a silver chromate staining technique developed in the 1870s, enabled the selective visualization of entire neurons, including their processes, which had previously been indistinguishable in tissue preparations. Cajal's application of this method provided compelling evidence for the neuron doctrine, establishing that the nervous system consists of discrete, independent cells communicating via specialized junctions rather than a continuous syncytium.[22] Shortly thereafter, in 1909, German neurologist Korbinian Brodmann published a seminal cytoarchitectonic map of the human cerebral cortex, delineating 52 distinct areas based on variations in neuronal cell types, layers, and organization, which became essential for correlating structure with function in neuroanatomical studies.[23] Advancements in the mid-20th century further refined this cellular perspective through electron microscopy, invented in the 1930s and applied to neuroanatomy by the 1950s. Pioneering studies by Sanford Palay and George Palade revealed the ultrastructural details of synapses, including presynaptic vesicles, synaptic clefts, and postsynaptic densities, confirming the physical site of interneuronal transmission and supporting the chemical synapse hypothesis.[24] The 1970s introduced non-invasive imaging modalities that transformed neuroanatomy from postmortem analysis to in vivo exploration. Computed tomography (CT), developed by Godfrey Hounsfield in 1971, utilized X-ray attenuation to generate cross-sectional brain images, enabling detection of structural abnormalities without surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), pioneered by Paul Lauterbur and Peter Mansfield in the mid-1970s, offered superior soft-tissue contrast by exploiting nuclear magnetic resonance, allowing detailed visualization of gray and white matter in living subjects.[25][26] In the 1990s, the U.S. National Institutes of Health launched the Human Brain Project as part of the Decade of the Brain initiative, focusing on neuroinformatics to integrate disparate neuroscience datasets and facilitate large-scale modeling of brain connectivity. This effort laid the groundwork for connectome initiatives, which seek comprehensive maps of neural wiring akin to the Human Genome Project's sequencing of DNA. Subsequent projects, such as the 2010 Human Connectome Project, advanced this vision by combining high-resolution diffusion MRI and tractography to chart human brain networks in healthy populations.[27][28] Building on these, the U.S. BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative, announced in 2013, represents a landmark effort to develop innovative technologies for mapping brain circuits at multiple scales, from synapses to whole-brain networks, enhancing understanding of neural structure and function.[29] Post-2010 innovations have integrated molecular genetics and computational tools for unprecedented precision in neural mapping. Optogenetics, refined in the 2010s, employs light-sensitive proteins like channelrhodopsin to activate or silence specific neuron populations, enabling causal dissection of circuits in behaving animals. CRISPR-Cas9 technologies, adapted for neuroscience since 2012, allow targeted editing of neural genes to label and trace cell types, revealing connectivity patterns at single-cell resolution. AI algorithms have accelerated 3D reconstructions from serial electron microscopy, as demonstrated in projects producing nanoscale brain atlases. Additionally, mRNA-based barcoding methods, such as those using random RNA sequences for high-throughput projection mapping, have expanded tracing capabilities beyond traditional dyes. The 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman for nucleoside modifications enabling stable mRNA delivery, has indirectly bolstered these techniques by improving synthetic mRNA tools for neural applications.[30][31][32] The 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun for the discovery of microRNA (miRNA) and its role in post-transcriptional gene regulation, a mechanism essential for controlling neural cell differentiation, synapse formation, and brain development in neuroanatomy.[33] Genomic approaches have revolutionized comparative neuroanatomy by linking evolutionary changes in brain structure to genetic sequences. Since the 2010s, comparative genomics has identified regulatory elements driving brain size expansion in primates, such as human-specific enhancers in genes like NOTCH2NL that promote cortical neurogenesis. These studies integrate multi-species transcriptomic data to trace conserved and divergent neural architectures, elucidating adaptations like enhanced human prefrontal connectivity.[34][35] As of November 2025, a major advance in developmental neuroanatomy emerged with the publication of the first comprehensive atlas of human brain cell types during development, mapping how stem cells differentiate into neurons and glia from embryonic stages through early childhood, as part of the BRAIN Initiative Cell Atlas Network (BICAN). This resource provides unprecedented insights into the cellular and genetic trajectories shaping brain structure.[36]Core Components

Gross Anatomy

The nervous system is divided into the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS), with gross anatomy encompassing the visible structures without magnification that form the foundational organization for neural processing and communication.[2] The CNS consists of the brain and spinal cord, encased within protective bony structures and membranes, while the PNS comprises nerves extending from the CNS to innervate peripheral tissues.[2] This macroscopic layout enables the integration of sensory input, motor output, and autonomic regulation across the body.[2] The brain, weighing approximately 1.4 kg in adults, is subdivided into the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain, each contributing to distinct functions visible at the gross level.[2] The forebrain includes the cerebrum, with its paired hemispheres divided into frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes separated by prominent sulci such as the central sulcus and lateral fissure, and featuring convoluted gyri that expand surface area for higher cognition.[2] Deep within the forebrain lie the thalamus and hypothalamus, acting as relay and regulatory hubs, respectively.[2] The midbrain, a short conduit between the forebrain and hindbrain, contains the cerebral peduncles and tectum, facilitating motor and auditory-visual relay.[37] The hindbrain encompasses the pons, medulla oblongata, and cerebellum; the pons bridges the cerebellum to the midbrain, the medulla handles vital autonomic centers like cardiovascular control, and the cerebellum coordinates movement through its folia-covered hemispheres.[2] The brainstem, formed by the midbrain, pons, and medulla, houses cranial nerve nuclei such as the oculomotor in the midbrain and hypoglossal in the medulla, essential for head and neck functions.[37] The spinal cord extends from the foramen magnum to the L1-L2 vertebral level, measuring about 45 cm in length, and is segmented into cervical (enlarged for upper limbs), thoracic, lumbar (enlarged for lower limbs), sacral, and coccygeal regions, with 31 pairs of spinal nerves emerging via ventral and dorsal roots.[2] Externally, it appears cylindrical with anterior median and posterolateral sulci, while internally, gray matter forms an H-shaped core surrounded by white matter tracts.[2] Ascending tracts, such as the dorsal columns (gracilis and cuneatus for fine touch and proprioception) and spinothalamic (for pain and temperature), convey sensory information upward to the brain, often decussating early.[38] Descending tracts, including the lateral corticospinal (for voluntary motor control) and vestibulospinal (for posture), transmit commands downward, with many crossing in the medulla.[38] Protective structures include the meninges—three layers enveloping the CNS: the tough outer dura mater forming dural folds like the falx cerebri, the web-like arachnoid mater overlying the subarachnoid space, and the delicate pia mater adhering to the brain and cord surfaces.[39] The ventricular system comprises fluid-filled cavities: paired lateral ventricles in the cerebrum connected via the interventricular foramina to the narrow third ventricle in the diencephalon, which links through the cerebral aqueduct to the fourth ventricle in the hindbrain, ultimately continuous with the central canal of the spinal cord and subarachnoid space.[40] These ventricles produce and circulate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for buoyancy and nutrient transport.[40] The blood-brain barrier, formed by endothelial tight junctions in cerebral capillaries supported by astrocytes and pericytes, selectively regulates substance passage to maintain neural homeostasis, absent in areas like the circumventricular organs.[41] The PNS connects the CNS to effectors and receptors, divided into somatic (voluntary control of skeletal muscles) and autonomic (involuntary regulation of viscera) components, with 12 pairs of cranial nerves emerging from the brain and 31 pairs of spinal nerves from the cord.[42] Cranial nerves include sensory types like olfactory (I) and optic (II), motor like oculomotor (III) and hypoglossal (XII), and mixed like trigeminal (V) and vagus (X), primarily innervating the head and neck.[43] Spinal nerves form plexuses—cervical (neck), brachial (upper limbs), lumbar (lower abdomen), and sacral (pelvis/legs)—distributing branches to limbs.[44] The autonomic division splits into sympathetic (thoracolumbar outflow from T1-L2, promoting arousal via chain ganglia) and parasympathetic (craniosacral via CN III, VII, IX, X and S2-S4, fostering conservation via terminal ganglia), with the enteric subsystem autonomously managing gut motility through myenteric and submucosal plexuses.[45]Cellular Anatomy

The cellular anatomy of the nervous system comprises neurons and glial cells as the primary constituents of neural tissue, forming the microscopic foundation that enables signal transmission and support functions across the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). Neurons serve as the excitable units responsible for processing and relaying information, while glial cells provide structural, metabolic, and protective roles. This organization underpins the functional complexity observed at larger scales, with neurons integrating inputs through intricate circuits.[3] Neurons are specialized cells characterized by their ability to generate and propagate electrical impulses. The soma, or cell body, houses the nucleus and organelles, facilitating protein synthesis and overall cellular maintenance essential for neuronal survival.[3] Extending from the soma are dendrites, branched structures that receive synaptic inputs from other neurons, allowing for signal integration; these processes also contribute to local protein synthesis and plasticity.[3] The axon projects from the soma as a long, slender extension that conducts action potentials away from the cell body toward target cells, often terminating in synaptic boutons where signals are transmitted.[3] Many axons are enveloped by a myelin sheath, a lipid-rich insulating layer that accelerates impulse conduction via saltatory propagation, formed by glial cells in both CNS and PNS.[46] Neurons exhibit morphological diversity, reflecting their specialized roles in different brain regions. Pyramidal neurons, comprising approximately 70-90% of cortical cells, feature a pyramid-shaped soma with a prominent apical dendrite extending toward the cortical surface and basal dendrites for broad input reception; they utilize glutamate as an excitatory neurotransmitter and form key corticocortical and subcortical connections.[47] In contrast, Purkinje cells are GABAergic inhibitory neurons unique to the cerebellar cortex, distinguished by their massive, fan-like dendritic arbor that receives up to 200,000 parallel fiber inputs, enabling precise motor coordination.[48] Other types, such as bipolar sensory neurons in the retina or pseudounipolar neurons in dorsal root ganglia, adapt to specific sensory or relay functions.[3] Synapses represent the junctions where neurons communicate, categorized as chemical or electrical. Chemical synapses, predominant in the mammalian CNS, involve a synaptic cleft where neurotransmitters are released from presynaptic vesicles upon calcium influx triggered by an action potential; this process, mediated by SNARE proteins, allows for modulated signaling with a delay of 0.5-1.0 ms as transmitters bind postsynaptic receptors.[49] Electrical synapses, formed by gap junctions composed of connexin proteins, enable direct ion flow between coupled neurons, facilitating rapid, bidirectional transmission without chemical intermediaries and often synchronizing activity in networks like those in the inferior olive.[49] Neurotransmitter release is terminated by reuptake into presynaptic terminals or glia, enzymatic degradation, or diffusion, ensuring precise temporal control.[50] Glial cells, outnumbering neurons in many regions, provide essential support without direct excitability. Astrocytes, star-shaped cells in the CNS, maintain ionic homeostasis by buffering potassium and neurotransmitters, form the blood-brain barrier through endfoot processes on capillaries, and supply metabolic substrates like lactate to neurons during activity.[51] Oligodendrocytes in the CNS extend processes to myelinate multiple axons, promoting efficient saltatory conduction and axonal integrity.[51] Microglia, the CNS's resident immune cells derived from yolk sac progenitors, surveil tissue for debris, phagocytose pathogens or apoptotic cells, and release cytokines in response to injury, contributing to neuroinflammation.[52] In the PNS, Schwann cells myelinate individual axons, aiding regeneration after damage by clearing debris and forming bands of Büngner to guide regrowth.[52] Neural circuits emerge from the interconnected projections of these cells, balancing local and long-range interactions to process information. Local circuits involve short-range connections within a brain region, such as inhibitory interneurons modulating nearby pyramidal cells to refine output precision.[53] Long-range projections, often from pyramidal neurons, extend across regions or hemispheres, like cortico-thalamic pathways that integrate sensory and cognitive signals, enabling coordinated brain-wide activity.[53] These projections form synaptic terminals with region-specific densities, supporting functions from sensory processing to decision-making.[54] As estimated in 2009, the human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons, with a near 1:1 ratio to non-neuronal (primarily glial) cells, challenging earlier estimates of 100 billion neurons and a 10:1 glia-to-neuron ratio; however, analyses as of 2025 suggest variability in counts, with possible ranges of 62–94 billion depending on factors such as sex and methodology.[55][56] This scaling reflects an isometric expansion from primate brains, where the cerebral cortex holds only about 16 billion neurons despite comprising 82% of brain mass.[55]Anatomical Orientations

Directional Terms

In neuroanatomy, directional terms establish a consistent framework for describing the relative positions of neural structures, essential for interpreting diagrams, lesions, and pathways across species and body postures. These terms are derived from the anatomical position, where the organism is imagined in a standard orientation, and they prioritize the neuraxis—the central axis of the brain and spinal cord—over peripheral body axes.[57][58] The primary directional terms include rostral and caudal, which denote positions toward the head (rostrum) and tail, respectively. In the brain, rostral directs toward the frontal regions or face, while caudal points toward the occipital lobe or posterior brainstem; in the spinal cord, rostral aligns with superior (upward) and caudal with inferior (downward).[57][58] Dorsal and ventral indicate toward the back (or top in the brain) and belly (or bottom in the brain), respectively; for the spinal cord, dorsal corresponds to the posterior surface and ventral to the anterior.[57] Medial and lateral describe proximity to the midline (medial) or distance from it (lateral), applicable uniformly to both central and peripheral nervous system components.[57][58] Ipsilateral refers to the same side of the body relative to a reference (e.g., a neural origin or lesion), while contralateral indicates the opposite side.[58] Conventions differ between quadrupeds and bipeds like humans due to postural variations. In quadrupeds, with a horizontal spine, rostral/caudal runs nose-to-tail, dorsal aligns with the spine (upward), and ventral with the ground (belly-down); superior/inferior is rarely used, as cranio-caudal directions follow cranial (headward) and caudal.[59] In humans, the upright bipedal posture shifts body axes: superior/inferior replaces cranio-caudal for the trunk (head-up, feet-down), but neuroanatomy adheres to the neuraxis orientation, retaining rostral/caudal along the tilted brain-spinal cord axis (approximately 120° bend at the brainstem) and dorsal/ventral relative to the head's back-front. This ensures cross-species comparability, though human descriptions often incorporate superior/inferior for peripheral nerves or body-integrated neural elements.[57][59][58] The foundational axes in neuroanatomy are the anterior-posterior (equivalent to rostral-caudal along the neuraxis), dorsoventral, and mediolateral, which define three-dimensional orientation for mapping structures like tracts or nuclei. For example, the anterior-posterior axis runs from the frontal cortex rostrally to the spinal cord caudally, the dorsoventral from the dorsal brainstem to ventral medulla, and the mediolateral from midline structures like the third ventricle laterally to cortical edges.[57][58] These terms are applied practically in describing pathologies and connectivity, such as neural decussations where pathways cross the midline. In the corticospinal tract, approximately 85-90% of fibers decussate at the medullary pyramids, projecting contralaterally to control limb motor neurons; thus, a lesion rostral to this decussation (e.g., in the motor cortex) produces ipsilateral upper motor neuron signs initially but contralateral deficits below the neck due to the crossing. The remaining 10-15% form the anterior corticospinal tract, remaining ipsilateral until lower spinal decussation via the anterior white commissure. Such terminology clarifies why cortical strokes often yield contralateral hemiparesis.[60]| Directional Term | Definition | Example in Neuroanatomy |

|---|---|---|

| Rostral/Caudal | Toward head/tail along neuraxis | Rostral: frontal cortex to occipital (caudal) |

| Dorsal/Ventral | Toward back/belly (or top/bottom in brain) | Dorsal: posterior spinal horn; Ventral: anterior motor neurons |

| Medial/Lateral | Toward/away from midline | Medial: corpus callosum; Lateral: temporal lobe |

| Ipsilateral/Contralateral | Same/opposite side relative to reference | Contralateral: post-decussation corticospinal control of limbs |