Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neuroimmune system

View on Wikipedia| Neuroimmune system | |

|---|---|

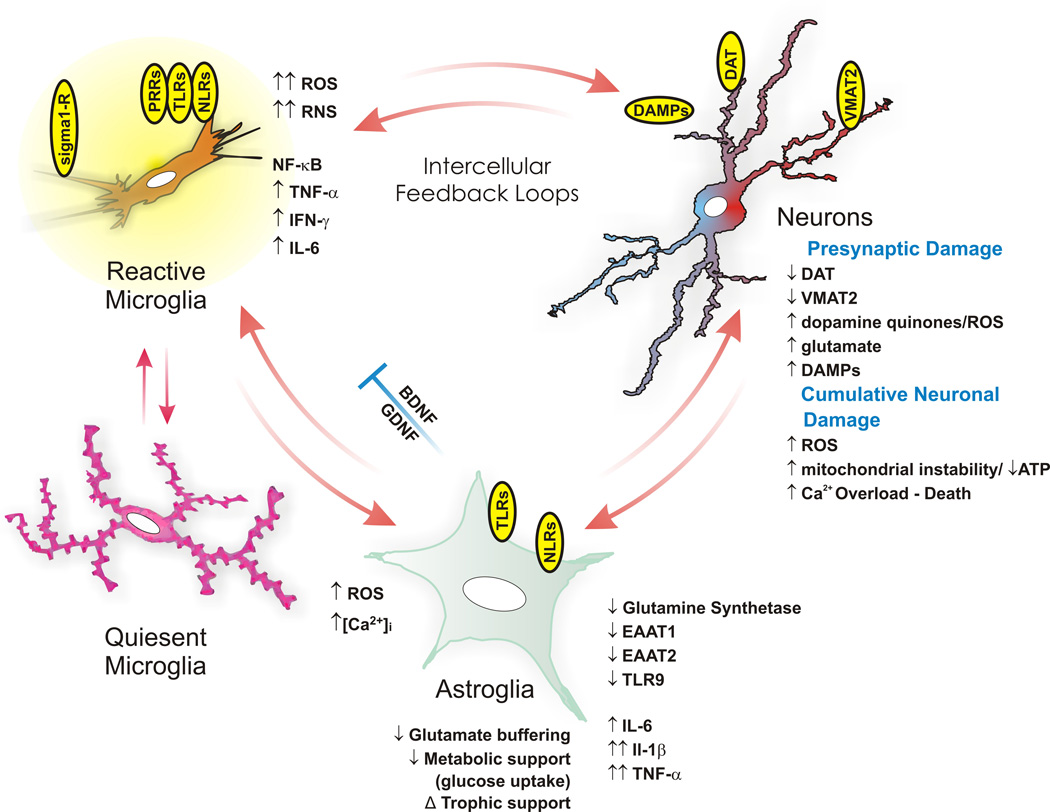

This diagram depicts the neuroimmune mechanisms that mediate methamphetamine-induced neurodegeneration in the human brain.[1] The NF-κB-mediated neuroimmune response to methamphetamine use which results in the increased permeability of the blood–brain barrier arises through its binding at and activation of sigma-1 receptors, the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs), the dysregulation of glutamate transporters (specifically, EAAT1 and EAAT2) and glucose metabolism, and excessive calcium influx in glial cells and dopamine neurons.[1][2][3] | |

| Details | |

| System | Neuroimmune |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D015213 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The neuroimmune system is a system of structures and processes involving the biochemical and electrophysiological interactions between the nervous system and immune system which protect neurons from pathogens. It serves to protect neurons against disease by maintaining selectively permeable barriers (e.g., the blood–brain barrier and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier), mediating neuroinflammation and wound healing in damaged neurons, and mobilizing host defenses against pathogens.[2][4][5]

The neuroimmune system and peripheral immune system are structurally distinct. Unlike the peripheral system, the neuroimmune system is composed primarily of glial cells;[1][5] among all the hematopoietic cells of the immune system, only mast cells are normally present in the neuroimmune system.[6] However, during a neuroimmune response, certain peripheral immune cells are able to cross various blood or fluid–brain barriers in order to respond to pathogens that have entered the brain.[2] For example, there is evidence that following injury macrophages and T cells of the immune system migrate into the spinal cord.[7] Production of immune cells of the complement system have also been documented as being created directly in the central nervous system.[8]

Structure

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2016) |

The key cellular components of the neuroimmune system are glial cells, including astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes.[1][2][5] Unlike other hematopoietic cells of the peripheral immune system, mast cells naturally occur in the brain where they mediate interactions between gut microbes, the immune system, and the central nervous system as part of the microbiota–gut–brain axis.[6]

G protein-coupled receptors that are present in both CNS and immune cell types and which are responsible for a neuroimmune signaling process include:[4]

- Chemokine receptors: CXCR4

- Cannabinoid receptors: CB1, CB2, GPR55

- Trace amine-associated receptors: TAAR1

- μ-Opioid receptors – all subtypes

Neuroimmunity is additionally mediated by the enteric nervous system, namely the interactions of enteric neurons and glial cells. These engage with enteroendocrine cells and local macrophages, sensing signals from the gut lumen, including those from the microbiota. These signals prompt local immune responses and transmit to the CNS through humoral and neural pathways. Interleukins and signals from immune cells can access the hypothalamus via the neurovascular unit or circumventricular organs.[9]

Cellular physiology

[edit]The neuro-immune system, and study of, comprises an understanding of the immune and neurological systems and the cross-regulatory impacts of their functions.[10] Cytokines regulate immune responses, possibly through activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.[medical citation needed] Cytokines have also been implicated in the coordination between the nervous and immune systems.[11] Instances of cytokine binding to neural receptors have been documented between the cytokine releasing immune cell IL-1 β and the neural receptor IL-1R.[11] This binding results in an electrical impulse that creates the sensation of pain.[11] Growing evidence suggests that auto-immune T-cells are involved in neurogenesis. Studies have shown that during times of adaptive immune system response, hippocampal neurogenesis is increased, and conversely that auto-immune T-cells and microglia are important for neurogenesis (and so memory and learning) in healthy adults.[12]

The neuroimmune system uses complementary processes of both sensory neurons and immune cells to detect and respond to noxious or harmful stimuli.[11] For example, invading bacteria may simultaneously activate inflammasomes, which process interleukins (IL-1 β), and depolarize sensory neurons through the secretion of hemolysins.[11][13] Hemolysins create pores causing a depolarizing release of potassium ions from inside the eukaryotic cell and an influx of calcium ions.[11] Together this results in an action potential in sensory neurons and the activation of inflammasomes.[11]

Injury and necrosis also cause a neuroimmune response. The release of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from damaged cells binds to and activates both P2X7 receptors on macrophages of the immune system, and P2X3 receptors of nociceptors of the nervous system.[11] This causes the combined response of both a resulting action potential due to the depolarization created by the influx of calcium and potassium ions, and the activation of inflammasomes.[11] The produced action potential is also responsible for the sensation of pain, and the immune system produces IL-1 β as a result of the ATP P2X7 receptor binding.[11]

Although inflammation is typically thought of as an immune response, there is an orchestration of neural processes involved with the inflammatory process of the immune system. Following injury or infection, there is a cascade of inflammatory responses such as the secretion of cytokines and chemokines that couple with the secretion of neuropeptides (such as substance P) and neurotransmitters (such as serotonin).[7][11][13] Together, this coupled neuroimmune response has an amplifying effect on inflammation.[11]

Neuroimmune responses

[edit]Neuron-glial cell interaction

[edit]

Neurons and glial cells work in conjunction to combat intruding pathogens and injury. Chemokines play a prominent role as a mediator between neuron-glial cell communication since both cell types express chemokine receptors.[7] For example, the chemokine fractalkine has been implicated in communication between microglia and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons in the spinal cord.[14] Fractalkine has been associated with hypersensitivity to pain when injected in vivo, and has been found to upregulate inflammatory mediating molecules.[14] Glial cells can effectively recognize pathogens in both the central nervous system and in peripheral tissues.[15] When glial cells recognize foreign pathogens through the use of cytokine and chemokine signaling, they are able to relay this information to the CNS.[15] The result is an increase in depressive symptoms.[15] Chronic activation of glial cells however leads to neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation.[15]

Microglial cells are of the most prominent types of glial cells in the brain. One of their main functions is phagocytozing cellular debris following neuronal apoptosis.[15] Following apoptosis, dead neurons secrete chemical signals that bind to microglial cells and cause them to devour harmful debris from the surrounding nervous tissue.[15] Microglia and the complement system are also associated with synaptic pruning as their secretions of cytokines, growth factors and other complements all aid in the removal of obsolete synapses.[15]

Astrocytes are another type of glial cell that among other functions, modulate the entry of immune cells into the CNS via the blood–brain barrier (BBB).[15] Astrocytes also release various cytokines and neurotrophins that allow for immune cell entry into the CNS; these recruited immune cells target both pathogens and damaged nervous tissue.[15]

Reflexes

[edit]Withdrawal reflex

[edit]

The withdrawal reflex is a reflex that protects an organism from harmful stimuli.[13] This reflex occurs when noxious stimuli activate nociceptors that send an action potential to nerves in the spine, which then innervate effector muscles and cause a sudden jerk to move the organism away from the dangerous stimuli.[11] The withdrawal reflex involves both the nervous and immune systems.[11] When the action potential travels back down the spinal nerve network, another impulse travels to peripheral sensory neurons that secrete amino acids and neuropeptides like calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and Substance P.[11][13] These chemicals act by increasing the redness, swelling of damaged tissues, and attachment of immune cells to endothelial tissue, thereby increasing the permeability of immune cells across capillaries.[11][13]

Reflex response to pathogens and toxins

[edit]Neuroimmune interactions also occur when pathogens, allergens, or toxins invade an organism.[11] The vagus nerve connects to the gut and airways and elicits nerve impulses to the brainstem in response to the detection of toxins and pathogens.[11] This electrical impulse that travels down from the brain stem travels to mucosal cells and stimulates the secretion of mucus; this impulse can also cause ejection of the toxin by muscle contractions that cause vomiting or diarrhea.[11]

Neuroimmune connections and the vagus nerve have also been highlighted more recently as essential to maintaining homeostasis in the context of novel viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 [16] This is especially relevant when considering the role of the vagus nerve in regulating systemic inflammation via the Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway. [17]

Reflex response to parasites

[edit]The neuroimmune system is involved in reflexes associated with parasitic invasions of hosts. Nociceptors are also associated with the body's reflexes to pathogens as they are in strategic locations, such as airways and intestinal tissues, to induce muscle contractions that cause scratching, vomiting, and coughing.[11] These reflexes are all designed to eject pathogens from the body. For example, scratching is induced by pruritogens that stimulate nociceptors on epidermal tissues.[11] These pruritogens, like histamine, also cause other immune cells to secrete further pruritogens in an effort to cause more itching to physically remove parasitic invaders.[11] In terms of intestinal and bronchial parasites, vomiting, coughing, sneezing, and diarrhea can also be caused by nociceptor stimulation in infected tissues, and nerve impulses originating from the brain stem that innervate respective smooth muscles.[11]

Eosinophils in response to capsaicin, can trigger further sensory sensitization to the molecule.[18] Patients with chronic cough also have an enhanced cough reflex to pathogens even if the pathogen has been expelled.[18] In both cases, the release of eosinophils and other immune molecules cause a hypersensitization of sensory neurons in bronchial airways that produce enhanced symptoms.[11][18] It has also been reported that increased immune cell secretions of neurotrophins in response to pollutants and irritants can restructure the peripheral network of nerves in the airways to allow for a more primed state for sensory neurons.[11]

Clinical significance

[edit]It has been demonstrated that prolonged psychological stress could be linked with increased risk of infection via viral respiratory infection. Studies, in animals, indicate that psychological stress raises glucocorticoid levels and eventually, an increase in susceptibility to streptococcal skin infections.[19]

The neuroimmune system plays a role in Alzheimer's disease. In particular, microglia may be protective by promoting phagocytosis and removal of amyloid-β (Aβ) deposits, but also become dysfunctional as disease progresses, producing neurotoxins, ceasing to clear Aβ deposits, and producing cytokines that further promote Aβ deposition.[20] It has been shown that in Alzheimer's disease, amyloid-β directly activates microglia and other monocytes to produce neurotoxins.[21]

Astrocytes have also been implicated in multiple sclerosis (MS). Astrocytes are responsible for demyelination and the destruction of oligodendrocytes that is associated with the disease.[15] This demyelinating effect is a result of the secretion of cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) from activated astrocyte cells onto neighboring neurons.[15] Astrocytes that remain in an activated state form glial scars that also prevent the re-myelination of neurons, as they are a physical impediment to oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs).[22]

The neuroimmune system is essential for increasing plasticity following a CNS injury via an increase in excitability and a decrease in inhibition, which leads to synaptogenesis and a restructuring of neurons. The neuroimmune system may play a role in recovery outcomes after a CNS injury.[23]

The neuroimmune system is also involved in asthma and chronic cough, as both are a result of the hypersensitized state of sensory neurons due to the release of immune molecules and positive feedback mechanisms.[18]

Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that cellular (microglia/macrophages, leukocytes, astrocytes, and mast cells, etc.) and molecular neuroimmune responses contribute to secondary brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage.[24][25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Beardsley PM, Hauser KF (2014). "Glial Modulators as Potential Treatments of Psychostimulant Abuse". Emerging Targets & Therapeutics in the Treatment of Psychostimulant Abuse. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 69. pp. 1–69. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00001-9. ISBN 9780124201187. PMC 4103010. PMID 24484974.

Glia (including astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes), which constitute the majority of cells in the brain, have many of the same receptors as neurons, secrete neurotransmitters and neurotrophic and neuroinflammatory factors, control clearance of neurotransmitters from synaptic clefts, and are intimately involved in synaptic plasticity. Despite their prevalence and spectrum of functions, appreciation of their potential general importance has been elusive since their identification in the mid-1800s, and only relatively recently have they been gaining their due respect. This development of appreciation has been nurtured by the growing awareness that drugs of abuse, including the psychostimulants, affect glial activity, and glial activity, in turn, has been found to modulate the effects of the psychostimulants

- ^ a b c d Loftis JM, Janowsky A (2014). "Neuroimmune Basis of Methamphetamine Toxicity". Neuroimmune Signaling in Drug Actions and Addictions. International Review of Neurobiology. Vol. 118. pp. 165–197. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801284-0.00007-5. ISBN 9780128012840. PMC 4418472. PMID 25175865.

Collectively, these pathological processes contribute to neurotoxicity (e.g., increased BBB permeability, inflammation, neuronal degeneration, cell death) and neuropsychiatric impairments (e.g., cognitive deficits, mood disorders)

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)

"Figure 7.1: Neuroimmune mechanisms of methamphetamine-induced CNS toxicity" - ^ Kaushal N, Matsumoto RR (March 2011). "Role of sigma receptors in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity". Curr Neuropharmacol. 9 (1): 54–57. doi:10.2174/157015911795016930. PMC 3137201. PMID 21886562.

- ^ a b Rogers TJ (2012). "The molecular basis for neuroimmune receptor signaling". J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 7 (4): 722–4. doi:10.1007/s11481-012-9398-4. PMC 4011130. PMID 22935971.

- ^ a b c Gimsa U, Mitchison NA, Brunner-Weinzierl MC (2013). "Immune privilege as an intrinsic CNS property: astrocytes protect the CNS against T-cell-mediated neuroinflammation". Mediators Inflamm. 2013: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2013/320519. PMC 3760105. PMID 24023412.

Astrocytes have many functions in the central nervous system (CNS). ... they are responsible for formation of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and make up the glia limitans. Here, we review their contribution to neuroimmune interactions and in particular to those induced by the invasion of activated T cells. ... Within the central nervous system (CNS), astrocytes are the most abundant cells.

- ^ a b Polyzoidis S, Koletsa T, Panagiotidou S, Ashkan K, Theoharides TC (2015). "Mast cells in meningiomas and brain inflammation". J Neuroinflammation. 12 (1) 170. doi:10.1186/s12974-015-0388-3. PMC 4573939. PMID 26377554.

MCs originate from a bone marrow progenitor and subsequently develop different phenotype characteristics locally in tissues. Their range of functions is wide and includes participation in allergic reactions, innate and adaptive immunity, inflammation, and autoimmunity [34]. In the human brain, MCs can be located in various areas, such as the pituitary stalk, the pineal gland, the area postrema, the choroid plexus, thalamus, hypothalamus, and the median eminence [35]. In the meninges, they are found within the dural layer in association with vessels and terminals of meningeal nociceptors [36]. MCs have a distinct feature compared to other hematopoietic cells in that they reside in the brain [37]. MCs contain numerous granules and secrete an abundance of prestored mediators such as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), neurotensin (NT), substance P (SP), tryptase, chymase, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TNF, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and varieties of chemokines and cytokines some of which are known to disrupt the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [38–40].

They key role of MCs in inflammation [34] and in the disruption of the BBB [41–43] suggests areas of importance for novel therapy research. Increasing evidence also indicates that MCs participate in neuroinflammation directly [44–46] and through microglia stimulation [47], contributing to the pathogenesis of such conditions such as headaches, [48] autism [49], and chronic fatigue syndrome [50]. In fact, a recent review indicated that peripheral inflammatory stimuli can cause microglia activation [51], thus possibly involving MCs outside the brain. - ^ a b c Ji, Ru-Rong; Xu, Zhen-Zhong; Gao, Yong-Jing (2014). "Emerging targets in neuroinflammation-driven chronic pain". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 13 (7): 533–548. doi:10.1038/nrd4334. PMC 4228377. PMID 24948120.

- ^ Stephan, Alexander H.; Barres, Ben A.; Stevens, Beth (2012-01-01). "The Complement System: An Unexpected Role in Synaptic Pruning During Development and Disease". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 35 (1): 369–389. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113810. PMID 22715882. S2CID 2309037.

- ^ Benarroch, Eduardo E. (2019-02-19). "Autonomic nervous system and neuroimmune interactions: New insights and clinical implications". Neurology. 92 (8): 377–385. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006942. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 30651384.

- ^ Brady, Scott T.; Siegel, George J. (2012-01-01). Basic Neurochemistry: Principles of Molecular, Cellular and Medical Neurobiology. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123749475.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Talbot, Sébastien; Foster, Simmie; Woolf, Clifford (February 22, 2016). "Neuroimmune Physiology and Pathology". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 34: 421–47. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055340. PMID 26907213.

- ^ Ziv Y, Ron N, Butovsky O, Landa G, Sudai E, Greenberg N, Cohen H, Kipnis J, Schwartz M (2006). "Immune cells contribute to the maintenance of neurogenesis and spatial learning abilities in adulthood". Nat. Neurosci. 9 (2): 268–75. doi:10.1038/nn1629. PMID 16415867. S2CID 205430936.

- ^ a b c d e McMahon, Stephen; La Russa, Federica; Bennett, David (June 19, 2015). "Crosstalk between the nociceptive and immune systems in host defence and disease". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 16 (7): 389–402. doi:10.1038/nrn3946. PMID 26087680. S2CID 22294761.

- ^ a b Miller, Richard; Hosung, Jung; Bhangoo, Sonia; Fletcher, White (2009). Sensory Nerves. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. pp. 417–449. ISBN 978-3-540-79090-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tian, Li; Ma, Li; Kaarela, Tiina; Li, Zhilin (July 2, 2012). "Neuroimmune crosstalk in the central nervous system and its significance for neurological diseases". Journal of Neuroinflammation. 9 594: 155. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-9-155. PMC 3410819. PMID 22747919.

- ^ Rangon, Claire-Marie; Niezgoda, Adam (2022-07-29). "Understanding the Pivotal Role of the Vagus Nerve in Health from Pandemics". Bioengineering. 9 (8): 352. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9080352. ISSN 2306-5354. PMC 9405360. PMID 36004877.

- ^ Rosas-Ballina, M.; Tracey, K. J. (June 2009). "Cholinergic control of inflammation". Journal of Internal Medicine. 265 (6): 663–679. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02098.x. PMC 4540232. PMID 19493060.

- ^ a b c d Chung, Kian (October 2014). "Approach to chronic cough: the neuropathic basis for cough hypersensitivity syndrome". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 6 (Suppl 7): S699–707. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.08.41. PMC 4222934. PMID 25383203.

- ^ Kawli, Trupti; He, Fanglian; Tan, Man-Wah (2010-01-01). "It takes nerves to fight infections: insights on neuro-immune interactions from C. elegans". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 3 (11–12): 721–731. doi:10.1242/dmm.003871. ISSN 1754-8403. PMC 2965399. PMID 20829562.

- ^ Farfara, D.; Lifshitz, V.; Frenkel, D. (2008). "Neuroprotective and neurotoxic properties of glial cells in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 12 (3): 762–780. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00314.x. ISSN 1582-1838. PMC 4401126. PMID 18363841.

- ^ Hickman SE, El Khoury J (2013). "The neuroimmune system in Alzheimer's disease: the glass is half full". J. Alzheimers Dis. 33 (Suppl 1): S295–302. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-129027. PMC 8176079. PMID 22751176.

- ^ Nair, Aji; Frederick, Terra; Miller, Stephen (September 2008). "Astrocytes in Multiple Sclerosis: a Product of their environment". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (17): 2702–20. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8059-5. PMC 2858316. PMID 18516496.

- ^ O’Reilly, Micaela L.; Tom, Veronica J. (2020). "Neuroimmune System as a Driving Force for Plasticity Following CNS Injury". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 14: 187. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.00187. ISSN 1662-5102. PMC 7390932. PMID 32792908.

- ^ Ren H, Han R, Chen X, Liu X, Wan J, Wang L, Yang X, Wang J (May 2020). "Potential therapeutic targets for intracerebral hemorrhage-associated inflammation: An update". J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 40 (9): 1752–1768. doi:10.1177/0271678X20923551. PMC 7446569. PMID 32423330.

- ^ Zhu H, Wang Z, Yu J, Yang X, He F, Liu Z, Che F, Chen X, Ren H, Hong M, Wang J (March 2019). "Role and mechanisms of cytokines in the secondary brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage". Prog. Neurobiol. 178 101610. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.03.003. PMID 30923023. S2CID 85495400.

Further reading

[edit]- Ikezu, Tsuneya; Gendelman, Howard E. (2008-03-21). Neuroimmune Pharmacology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780387725734.