Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Percussion cap

View on Wikipedia

The percussion cap, percussion primer, or caplock, introduced in the early 1820s, is a type of single-use percussion ignition device for muzzle loader firearm locks enabling them to fire reliably in any weather condition.[1] Its invention gave rise to the caplock mechanism or percussion lock system which used percussion caps struck by the hammer to set off the gunpowder charge in rifles and cap and ball firearms. Any firearm using a caplock mechanism is a percussion gun. Any long gun with a cap-lock mechanism and rifled barrel is a percussion rifle. Cap and ball describes cap-lock firearms discharging a single bore-diameter spherical bullet with each shot.

Description

[edit]

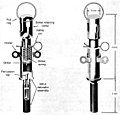

The percussion cap is a small cylinder of copper or brass with one closed end. Inside the closed end is a small amount of a shock-sensitive explosive material such as mercury fulminate (discovered in 1800; it was the only practical detonator used from about the mid-19th century to the early 20th century[2]).

The caplock mechanism consists of a hammer and a nipple (sometimes referred to as a cone). The nipple contains a hollow conduit which goes into the rearmost part of the gun barrel, and the percussion cap is placed over the nipple hole. Pulling the trigger releases the hammer, which strikes the percussion cap against the nipple (which serves as an anvil), crushes it and detonates the mercury fulminate inside, which releases sparks that travel through the hollow nipple into the barrel and ignite the main powder charge.

Percussion caps have been made in small sizes for pistols and larger sizes for rifles and muskets.[1]

Origins

[edit]Earlier firearms used flintlock mechanisms causing a piece of flint to strike a steel frizzen producing sparks to ignite a pan of priming powder and thereby fire the gun's main powder charge. The flintlock mechanism replaced older ignition systems such as the matchlock and wheellock, but all were prone to misfire in wet weather.[citation needed]

The discovery of fulminates was made by Edward Charles Howard (1774–1816) in 1800.[3][4] The invention that made the percussion cap possible using the recently discovered fulminates was patented by the Reverend Alexander John Forsyth of Belhelvie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, in 1807.[1] The rudimentary percussion system was invented by Forsyth as a solution to the problem that birds would startle when smoke puffed from the powder pan of his flintlock shotgun, giving them sufficient warning to escape the shot.[1] This early percussion lock system operated in a nearly identical fashion to flintlock firearms and used a fulminating primer made of fulminate of mercury, chlorate of potash, sulphur and charcoal, ignited by concussion.[5][6] His invention of a fulminate-primed firing mechanism deprived the birds of their early warning system, both by avoiding the initial puff of smoke from the flintlock powder pan, as well as shortening the interval between the trigger pull and the shot leaving the muzzle. Forsyth patented his "scent bottle" ignition system in 1807. However, it was not until after Forsyth's patents expired that the conventional percussion cap system was developed. Joseph Manton invented a precursor to the percussion cap in 1814, comprising a copper tube that detonated when crushed.[7] This was further developed in 1822 by the English-born American artist Joshua Shaw, as a copper cup filled with fulminates.[8]

The first purpose-built caplock guns were fowling pieces commissioned by sportsmen in Regency era England. Due to the mechanism's compactness and superior reliability compared to the flintlock, gunsmiths were able to manufacture pistols and long guns with two barrels. Early caplock handguns with two or more barrels and a single lock are known as turn-over or twister pistols, due to the need to manually rotate the second barrel to align with the hammer. With the addition of a third barrel, and a ratchet to mechanically turn the barrels while cocking the hammer, these caplock pistols evolved into the pepper-box revolver during the 1830s.[9]

The caplock offered many improvements over the flintlock. The caplock was easier and quicker to load, more resilient to weather conditions, and far more reliable than the flintlock. Many of the older flintlock weapons were later converted to the caplock, so that they could take advantage of these features.[1]

-

Japanese matchlock converted to caplock, the brass band is dated 1894 (明治二十七)

-

A pair of caplock twister pistols

-

Inverted percussion pistol, 9.5 mm; made by gunsmith Correvon, Morges, 1854

Parallel developments

[edit]Joshua Shaw is sometimes credited (primarily by himself) with the development of the first metallic percussion cap in 1814, a reusable one made of iron, then a disposable pewter one in 1815 and finally a copper one in 1816. There is no independent proof of this since Shaw was advised he could not patent it due to Alexander Forsyth's patent for using fulminates to ignite guns being in force between 1807 and 1821. Shaw says he only shared the development of his innovation with a few associates (gunmakers and others) who were sworn to secrecy and never provided affidavits at a later date. Shaw's claim to have been the inventor remains clouded in controversy as he did not patent the idea until 1822, having moved to America in 1817. According to Lewis Winant, the US government's decision to award Shaw $25,000 as compensation for his invention being used by the Army was a mistake. Congress believed Shaw's patent was the earliest in the world and awarded him a large sum of money based on this belief. The investigators had overlooked two French patents and the earlier use of the idea in Britain.

The earliest known patent anywhere in the world which specifically mentions a percussion cap and nipple was granted in France on 29 July 1818 to François Prélat, four years before Shaw's patent. Prelat made a habit of copying English patents and inventions and the mode of operation he describes is flawed.[10] Secondly a French patent of a percussion cap and nipple had been granted in 1820 to Deboubert. However predating both of these French claims, the most likely inventor of the percussion cap, according to historian Sidney James Gooding, was Joseph Egg (nephew of Durs Egg), around 1817, .[11]

There were other earlier claims. Col. Peter Hawker in 1830 simultaneously claimed and denied being the inventor. "I do not wish to say I was the inventor of it - very probably not" but then immediately recounts that he came up with the idea of simplifying a Manton patch-lock, which could be troublesome, by designing a cap and nipple arrangement around 1816 when the patch lock was patented. He says he then presented a drawing to a reluctant Joseph Manton to make a few copper cap guns which were then sold.[12] Hawker, seems to give Joseph Manton more of the glory eight years later in the 1838 edition of his 'Instructions to young Sportsmen', by stating categorically that "copper tubes and primers were decidedly invented by Joe Manton". By the 1850s Hawker was again claiming the invention for himself in his press advertisements.[13]

Despite many years of research by Winant, Gooding and De Witt Bailey, the jury is still out as the competing claims are based on personal accounts and have little or no independently verifiable evidence.

While the metal percussion cap was the most popular and widely used type of primer, their small size made them difficult to handle under the stress of combat or while riding a horse. Accordingly, several manufacturers developed alternative, "auto-priming" systems. The "Maynard tape primer", for example, used a roll of paper "caps" much like today's toy cap gun. The Maynard tape primer was fitted to some firearms used in the mid-nineteenth century and a few saw brief use in the American Civil War. Other disc or pellet-type primers held a supply of tiny fulminate detonator discs in a small magazine. Cocking the hammer automatically advanced a disc into position. However, these automatic feed systems were difficult to make with the manufacturing systems in the early and mid-nineteenth century and generated more problems than they solved. They were quickly shelved in favor of a single percussion cap that, while unwieldy in some conditions, could be carried in sufficient quantities to make up for occasionally dropping one, while a jammed tape primer system would instead reduce the rifle to an awkward club.[1]

Military firearms

[edit]This invention was gradually improved, and came to be used, first in a steel cap and then in a copper cap, by various gunmakers and private individuals before coming into general military use nearly thirty years later.[when?] The alteration of the military flintlock to the percussion musket was easily accomplished by replacing the powder pan and steel frizzen with a nipple and by replacing the cock or hammer that held the flint by a smaller hammer formed with a hollow made to fit around the nipple when released by the trigger. On the nipple was placed the copper cap containing Shaw's detonating composition of three parts of chlorate of potash, two of fulminate of mercury and one of powdered glass. The hollow in the hammer contained the fragments of the cap if it fragmented, reducing the risk of injury to the firer's eyes. From the 1820s onwards, the armies of Britain, France, Russia, and America began converting their muskets to the new percussion system. Caplocks were generally applied to the British military musket (the Brown Bess) in 1842, a quarter of a century after the invention of percussion powder and after an elaborate government test at Woolwich in 1834. The first percussion firearm produced for the US military was the percussion carbine version (c.1833) of the M1819 Hall rifle. The Americans' breech loading caplock Hall rifles, muzzle loading rifled muskets and Colt Dragoon revolvers gave them an advantage over the smoothbore flintlock Brown Bess muskets used by Santa Anna's troops during the Mexican War. In Japan, matchlock pistols and muskets were converted to percussion from the 1850s onwards, and new guns based on existing designs were manufactured as caplocks.[14]

The Austrians instead used a variant of Manton's tube lock in their Augustin musket until the conventional caplock Lorenz rifle was introduced in 1855. The first practical solution for the problem of handling percussion caps in battle was the Prussian 1841 (Dreyse needle gun), which used a long needle to penetrate a paper cartridge filled with black powder and strike the percussion cap that was fastened to the base of the bullet.[15] While it had a number of problems, it was widely used by the Prussians and other German states in the mid-nineteenth century and was a major factor in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War. The needle gun originally fired paper cartridges containing a bullet, powder charge and percussion cap, but by the time of the Franco-Prussian War this had evolved into modern brass ammunition.[16]

-

Reproduction Springfield and Enfield caplocks

-

Detail of the firing mechanism on an instruction cutaway model of a French navy percussion pistol, model 1837

-

Caplock horse pistol, Swiss Ordnance 1817/42

-

Loading sequence for percussion revolvers

Later firearms evolution

[edit]The percussion cap brought about the invention of the modern cartridge case and made possible the general adoption of the breech-loading principle for all varieties of rifles, shotguns and pistols. After the American Civil War, Britain, France, and America began converting existing caplock guns to accept brass rimfire and centrefire cartridges. For muskets such as the 1853 Enfield and 1861 Springfield, this involved installing a firing pin in place of the nipple, and a trapdoor in the breech to accept the new bullets. Examples include the Trapdoor Springfield, Tabatière rifle, Westley Richards and Snider–Enfield conversions. The British Army used Snider Enfields contemporaneously with the Martini–Henry rifle until the .303 bolt action Lee–Metford repeating rifle was introduced in the 1880s. Later, military surplus Sniders were purchased as hunting and defensive weapons by British colonists and trusted local natives.[17][18]

Caplock revolvers such as the Colt Navy and Remington were also widely converted during the late 19th century, by replacing the existing cylinder with one designed for modern ammunition. These were used extensively by the Turks in the Russo-Turkish War, the US Cavalry during the Indian Wars, and also by gunfighters, lawmen, and outlaws in the old west.[19]

In the 1840s and 1850s, the percussion cap was first integrated into a metallic cartridge, where the bullet is held in by the casing, the casing is filled with gunpowder, and a primer is placed on the end. By the 1860s and 1870s, breech-loading metallic cartridges had made the percussion cap system obsolete.[citation needed]

Today, reproduction percussion firearms are popular for recreational shooters and percussion caps are still available (though some modern muzzleloaders use shotshell primers instead of caps).[20] Most percussion caps now use non-corrosive compounds such as lead styphnate.[1]

Other uses

[edit]Caps are used in cartridges, grenades, rocket-propelled grenades and rescue flares. Percussion caps are also used in land mine fuzes, booby-trap firing devices and anti-handling devices. Most purpose-made military booby-trap firing devices contain some form of spring-loaded firing pin designed to strike a percussion cap connected to a detonator at one end. The detonator is inserted into an explosive charge—e.g., C-4 or a block of TNT. Triggering the booby-trap (e.g., by pulling on a trip-wire) releases the cocked firing pin that flips forward to strike the percussion cap, firing it and the attached detonator; the shock-wave from the detonator sets off the main explosive charge.[citation needed]

-

Alternative design of USSR booby trap firing device – pull fuze: normally connected to tripwire. Percussion cap is clearly labelled.

-

USSR boobytrap firing device – pressure fuze: victim steps on loose floorboard with fuze concealed underneath.

-

Cross-sectional view of a Japanese Type 99 grenade showing percussion primer

-

Cross-sectional view of the fuze fitted to a German S-mine. Percussion cap is clearly labelled.

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Fadala, Sam (17 November 2006). The Complete Black powder Handbook. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 159–161. ISBN 0-89689-390-1.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wisniak, Jaime (2012). "Edward Charles Howard. Explosives, meteorites, and sugar". Educación Química. 23 (2). Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico: 230–239. doi:10.1016/s0187-893x(17)30114-3. ISSN 0187-893X.

- ^ Howard, Edward (1800) "On a New Fulminating Mercury," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 90 (1): 204–238.

- ^ Edward Charles Howard at National Portrait Gallery

- ^ Percussion lock

- ^ Samuel Parkes, The chemical catechism : with notes, illustrations, and experiments, New York : Collins and Co., 1818, page 494 (page 494 online, see "LVI. A New Kind of Gunpowder.")

- ^ Sam Fadala (2006). The Complete Blackpowder Handbook. Krause Publications. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-89689-390-0.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Joshua Shaw". Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Martin J. Dougherty (2017). Pistols and Revolvers: From 1400 to the present day. Amber Books Ltd. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-78274-266-1.

- ^ "Early Percussion Firearms". Spring Books. 25 October 2015.

- ^ Gooding, S. James (August 2018). "Joseph Egg - Inventor of the Copper Cap..." Canadian Journal of Arms Collecting. 36 (3). Arms Collecting Publications, Inc.: 75–79. ISSN 0008-3992. Retrieved 13 May 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hawker, Peter (1830). "Instructions to Young Sportsmen 6th edition (1830)". Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Hawker Ad - Inventor of the Copper Cap". Hampshire Chronicle. 30 November 1850.

- ^ "Met Museum". Met Museum. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "Kammerbusche". Militarygunsofeurope.eu. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Milivojevic, Dejan (18 January 2019). "The Revolutionary Rifle That Won the Austro-Prussian War and Gave Birth to the German Nation". warhistoryonline. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Loading and firing a Snider Enfield". Militaryheritage.com. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "Britain's big 577". Retrieved 5 November 2018 – via The Free Library.

- ^ "Colt revolver in the Old West". Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "Wheelgun Wednesday: American Gun Craft ROTO 12 Revolver Shotguns". 2 April 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Winant, L. (1956). Early percussion firearms. Bonanza Books