Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

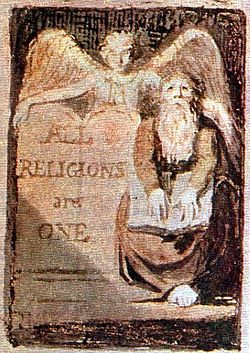

Perennial philosophy

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Outline |

| Influences |

| Research |

The perennial philosophy (Latin: philosophia perennis),[note 1] also referred to as perennialism and perennial wisdom, is a school of thought in philosophy and spirituality that posits that the recurrence of common themes across world religions illuminates universal truths about the nature of reality, humanity, ethics, and consciousness. Some perennialists emphasize common themes in religious experiences and mystical traditions across time and cultures; others argue that religious traditions share a single metaphysical truth or origin from which all esoteric and exoteric knowledge and doctrine have developed.

Perennialism has its roots in the Renaissance-era interest in neo-Platonism and its idea of the One from which all existence emerges. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) sought to integrate Hermeticism with Greek and Christian thought,[1] discerning a prisca theologia found in all ages.[2] Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) suggested that truth could be found in many—rather than just Biblical and Aristotelian traditions. He proposed a harmony between the thought of Plato and Aristotle and saw aspects of the prisca theologia in Averroes (Ibn Rushd), the Quran, Kabbalah, and other sources.[3] Agostino Steuco (1497–1548) coined the term philosophia perennis.[4]

Developments in the 19th and 20th centuries integrated Eastern religions and universalism—the idea that all religions, underneath apparent differences, point to the same Truth. In the early 19th century, the Transcendentalists propagated the idea of a metaphysical Truth and universalism—this inspired the Unitarians, who proselytized among Indian elites. Toward the end of the 19th century, the Theosophical Society further popularized universalism in the Western world and Western colonies. In the 20th century, this form of universalist perennialism was further popularized by Aldous Huxley and his book The Perennial Philosophy, which was inspired by Neo-Vedanta. Huxley and some other perennialists grounded their point of view in the commonalities of mystical experience and generally accepted religious syncretism.

Also, in the 20th century, the anti-modern Traditionalist School emerged in contrast to the universalist approach to perennialism. Inspired by Advaita Vedanta, Sufism and 20th-century works critical of modernity such as René Guénon's The Crisis of the Modern World, Traditionalism emphasises a metaphysical unitary source of the major religions in their "orthodox" forms and rejects syncretism, scientism, and secularism as deviations from the truth contained in their concept of Tradition.

Definition

[edit]There is no universally agreed upon definition of the term "perennial philosophy", and various thinkers have employed the term in different ways. For all perennialists, the term denotes a common wisdom at the heart of world religions, but exponents across time and place have differed on whether, or how, it can be defined. Some perennialists emphasise a sense of participation in an ineffable truth discovered in mystical experience, though ultimately beyond the scope of complete human understanding. Others seek a more well-developed metaphysics.

Drawing upon the same Renaissance foundations, in the 20th century the mystical universalist interpretation popularised by Aldous Huxley, and the metaphysical approach of the Traditionalist School became particularly influential.

Renaissance

[edit]The idea of a perennial philosophy originated with a number of Renaissance theologians who took inspiration from neo-Platonism and from the theory of Forms. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) argued that there is an underlying unity to the world, the soul or love, which has a counterpart in the realm of ideas.[2] According to Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), a student of Ficino, truth could be found in many, rather than just two, traditions.[3] According to Agostino Steuco (1497–1548) there is "one principle of all things, of which there has always been one and the same knowledge among all peoples."[5]

Aldous Huxley and mystical universalism

[edit]Aldous Huxley, author of the popular book The Perennial Philosophy, propagated a universalist interpretation of the world religions, inspired by Vivekananda's neo-Vedanta and his own use of psychedelic drugs.[6] According to Huxley:

The Perennial Philosophy is expressed most succinctly in the Sanskrit formula, tat tvam asi ('That thou art'); the Atman, or immanent eternal Self, is one with Brahman, the Absolute Principle of all existence; and the last end of every human being, is to discover the fact for himself, to find out who he really is.[7]

Huxley's approach to perennialism is grounded in ineffable mystical experience, which ego can obscure:

The divine Ground of all existence is a spiritual Absolute, ineffable in terms of discursive thought, but (in certain circumstances) susceptible of being directly experienced and realized by the human being. This Absolute is the God-without-form of Hindu and Christian mystical phraseology. The last end of man, the ultimate reason for human existence, is unitive knowledge of the divine Ground—the knowledge that can come only to those who are prepared to "Die to self" and so make room, as it were, for God.[7]

In Huxley's 1944 essay in Vedanta and the West, he proposes The Minimum Working Hypothesis, a basic outline which an individual can adopt to achieve the "Godhead":

That there is a Godhead or Ground, which is the unmanifested principle of all manifestation.

That the Ground is transcendent and immanent.

That it is possible for human beings to love, know and become the Ground.

That to achieve this unitive knowledge, to realize this supreme identity, is the final end and purpose of human existence.

That there is a Law or Dharma, which must be obeyed, a Tao or Way, which must be followed, if humans are to achieve their final end.[8]

Traditionalist School

[edit]For the Traditionalist Seyyed Hossein Nasr, the perennial philosophy is rooted in the concept of Tradition, which he defines as:

...truths or principles of a divine origin revealed or unveiled to mankind and, in fact, a whole cosmic sector through various figures envisaged as messengers, prophets, avataras, the Logos or other transmitting agencies, along with all the ramifications and applications of these principles in different realms including law and social structure, art, symbolism, the sciences, and embracing of course Supreme Knowledge along with the means for its attainment.[9]

— Seyyed Hossein Nasr quoted in Sallie B. King, The Philosophia Perennis and the Religions of the World, 2000

Origins

[edit]The perennial philosophy originates from a blending of neo-Platonism and Christianity. Neo-Platonism itself has diverse origins in the syncretic culture of the Hellenistic period, and was an influential philosophy throughout the Middle Ages.

Classical world

[edit]Hellenistic period: religious syncretism

[edit]During the Hellenistic period, Alexander the Great's campaigns brought about exchange of cultural ideas on its path throughout most of the known world of his era. The Greek Eleusinian Mysteries and Dionysian Mysteries mixed with such influences as the Cult of Isis, Mithraism and Hinduism, along with some Persian influences. Such cross-cultural exchange was not new to the Greeks; the Egyptian god Osiris and the Greek god Dionysus had been equated as Osiris-Dionysus by the historian Herodotus as early as the 5th century BCE (see Interpretatio graeca).[10][11]

Roman world: Philo of Alexandria

[edit]Philo of Alexandria (c. 25 BCE – c. 50 CE) attempted to reconcile Greek Rationalism with the Torah, which helped pave the way for Christianity with neoplatonism, and the adoption of the Old Testament with Christianity, as opposed to Gnostic roots of Christianity.[12] Philo translated Judaism into terms of Stoic, Platonic and neopythagorean elements, and held that God is "supra rational" and can be reached only through "ecstasy". He also held that the oracles of God supply the material of moral and religious knowledge.

Neoplatonism

[edit]Neoplatonism arose in the 3rd century CE and persisted until shortly after the closing of the Platonic Academy in Athens in 529 CE by Justinian I. Neoplatonists were heavily influenced by Plato, but also by the Platonic tradition that thrived during the six centuries which separated the first of the neoplatonists from Plato. The work of neoplatonic philosophy involved describing the derivation of the whole of reality from a single principle, "the One". It was founded by Plotinus,[web 1] and has been very influential throughout history. In the Middle Ages, neoplatonic ideas were integrated into the philosophical and theological works of many of the most important medieval Islamic, Christian, and Jewish thinkers.

Renaissance

[edit]Ficino and Pico della Mirandola

[edit]Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) believed that Hermes Trismegistos, the supposed author of the Corpus Hermeticum, was a contemporary of Moses and the teacher of Pythagoras, and the source of both Greek and Christian thought.[1] He argued that there is an underlying unity to the world, the soul or love, which has a counterpart in the realm of ideas. Platonic Philosophy and Christian theology both embody this truth. Ficino was influenced by a variety of philosophers including Aristotelian Scholasticism and various pseudonymous and mystical writings. Ficino saw his thought as part of a long development of philosophical truth, of ancient pre-Platonic philosophers (including Zoroaster, Hermes Trismegistus, Orpheus, Aglaophemus and Pythagoras) who reached their peak in Plato. The Prisca theologia, or venerable and ancient theology, which embodied the truth and could be found in all ages, was a vitally important idea for Ficino.[2]

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), a student of Ficino, went further than his teacher by suggesting that truth could be found in many, rather than just two, traditions. This proposed a harmony between the thought of Plato and Aristotle, and saw aspects of the Prisca theologia in Averroes, the Koran and the Kabbalah among other sources.[3] After the deaths of Pico and Ficino this line of thought expanded, and included Symphorien Champier, and Francesco Giorgio.

Steuco

[edit]De perenni philosophia libri X

[edit]The term perenni philosophia was first used by Agostino Steuco (1497–1548) who used it to title a treatise, De perenni philosophia libri X, published in 1540.[4] De perenni philosophia was the most sustained attempt at philosophical synthesis and harmony.[13] Steuco represents the renaissance humanist side of 16th-century Biblical scholarship and theology, although he rejected Luther and Calvin.[14] De perenni philosophia is a complex work which only contains the term philosophia perennis twice. It states that there is "one principle of all things, of which there has always been one and the same knowledge among all peoples."[15] This single knowledge (or sapientia) is the key element in his philosophy. In that he emphasises continuity over progress, Steuco's idea of philosophy is not one conventionally associated with the Renaissance. Indeed, he tends to believe that the truth is lost over time and is only preserved in the prisci theologica. Steuco preferred Plato to Aristotle and saw greater congruence between the former and Christianity than the latter philosopher. He held that philosophy works in harmony with religion and should lead to knowledge of God, and that truth flows from a single source, more ancient than the Greeks. Steuco was strongly influenced by Iamblichus's statement that knowledge of God is innate in all,[16] and also gave great importance to Hermes Trismegistus.

Influence

[edit]Steuco's perennial philosophy was highly regarded by some scholars for the two centuries after its publication, then largely forgotten until it was rediscovered by Otto Willmann in the late part of the 19th century.[14] Overall, De perenni philosophia was not particularly influential, and largely confined to those with a similar orientation to himself. The work was not put on the Index of works banned by the Roman Catholic Church, although his Cosmopoeia which expressed similar ideas was. Religious criticisms tended to the conservative view that held Christian teachings should be understood as unique, rather than seeing them as perfect expressions of truths that are found everywhere.[17] More generally, this philosophical syncretism was set out at the expense of some of the doctrines included within it, and it is possible that Steuco's critical faculties were not up to the task he had set himself. Further, placing so much confidence in the prisca theologia, turned out to be a shortcoming as many of the texts used in this school of thought later turned out to be bogus[ambiguous].[18] In the following two centuries the most favourable responses were largely Protestant and often in England.

Gottfried Leibniz later picked up on Steuco's term. The German philosopher stands in the tradition of this concordistic philosophy; his philosophy of harmony especially had affinity with Steuco's ideas. Leibniz knew about Steuco's work by 1687, but thought that De la vérité de la religion chrétienne by Huguenot philosopher Phillippe du Plessis-Mornay expressed the same truth better. Steuco's influence can be found throughout Leibniz's works, but the German was the first philosopher to refer to the perennial philosophy without mentioning the Italian.[19]

Popularisation and later developments

[edit]Transcendentalism and Unitarian Universalism

[edit]Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) was a pioneer of the idea of spirituality as a distinct field.[20] He was one of the major figures in Transcendentalism, which was rooted in English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, and the skepticism of Hume.[web 2] The Transcendentalists emphasised an intuitive, experiential approach of religion.[web 3] Following Schleiermacher,[21] an individual's intuition of truth was taken as the criterion for truth.[web 3] The Transcendentalists were largely inspired by Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), whose Critical and Miscellaneous Essays popularised German Romanticism in English and whose Sartor Resartus (1833–34) was a pioneer work of Western perennialism.[22] They also read and were influenced by Hindu texts, the first translations of which appeared in the late 18th and early 19th century.[web 3] They also endorsed universalist and Unitarian ideas, leading in the 20th century to Unitarian Universalism. Universalism holds the idea that there must be truth in other religions as well, since a loving God would redeem all living beings, not just Christians.[web 3][web 4]

Theosophical Society

[edit]By the end of the 19th century, the idea of a perennial philosophy was popularized by leaders of the Theosophical Society such as H. P. Blavatsky and Annie Besant, under the name of "Wisdom-Religion" or "Ancient Wisdom".[23] The Theosophical Society took an active interest in Asian religions, subsequently not only bringing those religions under the attention of a western audience but also influencing Hinduism and Buddhism in India, Sri Lanka and Japan.

Neo-Vedanta

[edit]Many perennialist thinkers (including Armstrong, Gerald Heard, Aldous Huxley, Huston Smith and Joseph Campbell) are influenced by Hindu mystics Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda,[24] who themselves have taken over western notions of universalism.[25] They regarded Hinduism to be a token of this perennial philosophy. This notion has influenced thinkers who have proposed versions of the perennial philosophy in the 20th century.[25]

The unity of all religions was a central impulse among Hindu reformers in the 19th century, who in turn influenced many 20th-century perennial philosophy-type thinkers. Key figures in this reforming movement included two Bengali Brahmins. Ram Mohan Roy, a philosopher and the founder of the modernising Brahmo Samaj religious organisation, reasoned that the divine was beyond description and thus that no religion could claim a monopoly in their understanding of it.

The mystic Ramakrishna's spiritual ecstasies included experiencing his identity with Christ, Mohammed and his own Hindu deity.[26] Ramakrishna's most famous disciple, Swami Vivekananda, travelled to the United States in the 1890s where he formed the Vedanta Society.

Roy, Ramakrishna and Vivekananda were all influenced by the Hindu school of Advaita Vedanta,[27] which they saw as the exemplification of a Universalist Hindu religiosity.[25]

Traditionalist School

[edit]The Traditionalist School is a group of 20th- and 21st-century thinkers concerned with what they consider to be the demise of traditional forms of knowledge, both aesthetic and spiritual, within Western society. The early proponents of this school are René Guénon, Ananda Coomaraswamy and Frithjof Schuon. Other important thinkers in this tradition include Titus Burckhardt, Martin Lings, Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Jean-Louis Michon, Marco Pallis, Huston Smith, Jean Borella, and Elémire Zolla. According to the Traditionalist School, orthodox religions are based on a singular metaphysical origin. According to the Traditionalist School, the "philosophia perennis" designates a worldview that is opposed to the scientism of modern secular societies and which promotes the rediscovery of the wisdom traditions of the pre-secular world.[citation needed] This view is exemplified by René Guénon in his 1945 book The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, one of the founding works of the Traditionalist School.

According to Frithjof Schuon:

It has been said more than once that total Truth is inscribed in an eternal script in the very substance of our spirit; what the different Revelations do is to "crystallize" and "actualize", in different degrees according to the case, a nucleus of certitudes which not only abides forever in the divine Omniscience, but also sleeps by refraction in the "naturally supernatural" kernel of the individual, as well as in that of each ethnic or historical collectivity or of the human species as a whole.[28]

The Traditionalist School continues this metaphysical orientation. According to this school, the perennial philosophy is "absolute Truth and infinite Presence".[29] Absolute Truth is "the perennial wisdom (sophia perennis) that stands as the transcendent source of all the intrinsically orthodox religions of humankind."[29] Infinite Presence is "the perennial religion (religio perennis) that lives within the heart of all intrinsically orthodox religions."[29] The Traditionalist School discerns a transcendent and an immanent dimension, namely the discernment of the Real or Absolute, c.q. that which is permanent; and the intentional "mystical concentration on the Real".[30]

According to Soares de Azevedo, the perennialist philosophy states that the universal truth is the same within each of the world's orthodox religious traditions, and is the foundation of their religious knowledge and doctrine. Each world religion is an interpretation of this universal truth, adapted to cater for the psychological, intellectual, and social needs of a given culture of a given period of history. This perennial truth has been rediscovered in each epoch by mystics of all kinds who have revived already existing religions, when they had fallen into empty platitudes and hollow ceremonialism.[31][page needed]

Shipley further notes that the Traditionalist School is oriented on orthodox traditions, and rejects modern syncretism and universalism, which together create new religions from older religions and compromise the standing traditions.[6]

Aldous Huxley

[edit]The term was popularized in the mid-twentieth century by Aldous Huxley, who was profoundly influenced by Vivekananda's Neo-Vedanta and Universalism.[32] In his 1945 book The Perennial Philosophy he defined the perennial philosophy as:

... the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical to, divine Reality; the ethic that places man's final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being; the thing is immemorial and universal. Rudiments of the perennial philosophy may be found among the traditional lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions.[33]

In contrast to the Traditionalist school, Huxley emphasized mystical experience over metaphysics:

The Buddha declined to make any statement in regard to the ultimate divine Reality. All he would talk about was Nirvana, which is the name of the experience that comes to the totally selfless and one-pointed [...] Maintaining, in this matter, the attitude of a strict operationalist, the Buddha would speak only of the spiritual experience, not of the metaphysical entity presumed by the theologians of other religions, as also of later Buddhism, to be the object and (since in contemplation the knower, the known and the knowledge are all one) at the same time the subject and substance of that experience.[7]

According to Aldous Huxley, in order to apprehend the divine reality, one must choose to fulfill certain conditions: "making themselves loving, pure in heart and poor in spirit."[34] Huxley argues that very few people can achieve this state. Those who have fulfilled these conditions, grasped the universal truth and interpreted it have generally been given the name of saint, prophet, sage or enlightened one.[35] Huxley argues that those who have, "modified their merely human mode of being", and have thus been able to comprehend "more than merely human kind and amount of knowledge" have also achieved this enlightened state.[36]

New Age

[edit]The idea of a perennial philosophy is influential in the New Age, a loosely defined Western spiritual movement that developed in the second half of the 20th century. Its central precepts have been described as "drawing on both Eastern and Western spiritual and metaphysical traditions and infusing them with influences from self-help and motivational psychology, holistic health, parapsychology, consciousness research and quantum physics".[37] The term New Age refers to the coming astrological Age of Aquarius.[web 5]

The New Age aims to create "a spirituality without borders or confining dogmas" that is inclusive and pluralistic.[38] It holds to "a holistic worldview",[39] emphasising that the Mind, Body and Spirit are interrelated[web 5] and that there is a form of monism and unity throughout the universe.[40] It attempts to create "a worldview that includes both science and spirituality"[41] and embraces a number of forms of mainstream science as well as other forms of science that are considered fringe.

Academic discussions

[edit]Mystical experience

[edit]The idea of a perennial philosophy, sometimes called perennialism, is a key area of debate in the academic discussion of mystical experience. Huston Smith notes that the Traditionalist School's vision of a perennial philosophy is not based on mystical experiences, but on metaphysical intuitions.[42] The discussion of mystical experience has shifted the emphasis in the perennial philosophy from these metaphysical intuitions to religious experience[42] and the notion of nonduality or altered state of consciousness.

William James popularized the use of the term "religious experience" in his 1902 book The Varieties of Religious Experience.[43] It has also influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge.[web 6] Writers such as W.T. Stace, Huston Smith, and Robert Forman argue that there are core similarities to mystical experience across religions, cultures and eras.[44] For Stace the universality of this core experience is a necessary, although not sufficient, condition for one to be able to trust the cognitive content of any religious experience.[45][verification needed]

Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of "religious experience" further back to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite. The notion of "religious experience" was used by Schleiermacher to defend religion against the growing scientific and secular critique. It was adopted by many scholars of religion, of which William James was the most influential.[46]

Critics point out that the emphasis on "experience" favours the atomic individual, instead of the community. It also fails to distinguish between episodic experience, and mysticism as a process, embedded in a total religious matrix of liturgy, scripture, worship, virtues, theology, rituals and practices.[47] Richard King also points to disjunction between "mystical experience" and social justice:[48]

The privatisation of mysticism—that is, the increasing tendency to locate the mystical in the psychological realm of personal experiences—serves to exclude it from political issues such as social justice. Mysticism thus comes to be seen as a personal matter of cultivating inner states of tranquility and equanimity, which, rather than serving to transform the world, reconcile the individual to the status quo by alleviating anxiety and stress.[48]

Religious pluralism

[edit]Religious pluralism holds that various world religions are limited by their distinctive historical and cultural contexts and thus there is no single, true religion. There are only many equally valid religions. Each religion is a direct result of humanity's attempt to grasp and understand the incomprehensible divine reality. Therefore, each religion has an authentic but ultimately inadequate perception of divine reality, producing a partial understanding of the universal truth, which requires syncretism to achieve a complete understanding as well as a path towards salvation or spiritual enlightenment.[49]

Although perennial philosophy also holds that there is no single true religion, it differs when discussing divine reality. Perennial philosophy states that a divine reality can be understood and that its existence is what allows the universal truth to be understood.[50] Each religion provides its own interpretation of the universal truth, based on its historical and cultural context, potentially providing everything required to observe the divine reality and achieve a state in which one will be able to confirm the universal truth and achieve salvation or spiritual enlightenment.[citation needed]

Evidence for perennial philosophy

[edit]Cognitive archeology such as analysis of cave paintings and other pre-historic art and customs suggests that a form of perennial philosophy or Shamanic metaphysics may stretch back to the birth of behavioral modernity, all around the world. Similar beliefs are found in present-day cultures such as Aboriginal Australians. Perennial philosophy postulates the existence of a spirit or concept world alongside the day-to-day world, and interactions between these worlds during dreaming and ritual, or on special days or at special places. It has been argued that perennial philosophy formed the basis for Platonism, with Plato articulating, rather than creating, much older widespread beliefs.[51][7]

Perennial trends in religions

[edit]Perennialists often ground their position in what they call a "common core" of religious wisdom which is found across traditions. They argue that since many of these themes developed independent of contact between the cultures concerned, they are likely to point to deeper truths from anthropological, phenomenological and/or metaphysical perspectives. Perennialists generally make a distinction between the exoteric and esoteric dimensions of the various religions, arguing that the exoteric doctrinal differences are cultural in nature, but that the mystical traditions of these religious use the language of these doctrines and cultural forms to express identical or similar things. The perennialist rabbi Rami Shapiro expresses it from a Jewish perspective in this way:

Religions are like languages: no language is true or false; all languages are of human origin; each language reflects and shapes the civilization that speaks it; there are things you can say in one language that you cannot say or say as well in another; and the more languages you speak, the more nuanced your understanding of life becomes. Yet it is silence that reveals the ultimate Truth:

אֵ֥ין ע֖וד מִלְבַדֽו/ein od milvado

There is nothing other than God (Deut 4:35).[52]

What follows is a summary of some of the perennialist currents which have emerged in various religions.

Hinduism

[edit]Famous Hindu mystic Sri Ramakrishna stated that God can be realized through many different means and therefore all religions are true because each religion is nothing but different means towards the ultimate goal.[53]

Christianity

[edit]Clement of Alexandria, who had both knowledge and admiration for Greek philosophy, thought that Greek wisdom did not contradict Christianity because it shared its source with it. According to him, philosophy is not secular knowledge but sacred knowledge derived from the reason revealed in Christ.[54]

Islam/Sufism

[edit]In general, Muslims have shown a tendency towards religious exclusivism, as in other Abrahamic religions. However, there have been some exceptions to this in history. Hallaj was one of the leading Sufis with perennial perspective. Hallaj said the following about a co-religionist who insulted a Jew:

You should know that Judaism, Christianity and other religions are just various names and different names; but the purpose in all of them is the same, they are not different. I thought a lot about what religions are. As a result, I saw that religions are various branches of a root. From a person, from his habits. Do not demand that he choose a religion that restricts him and separates him from his ties. He will search for the reason for existence and the meaning of supreme purposes in the way he understands best.[55]

Sufi Inayat Khan, who lived in the 20th century, explained Sufism to the masses with its universal aspect and stated that it repeated the same common message with the mystical branches of other religions, and frequently made references to different religious/mystical traditions in his speeches and writings.[56]

Criticism

[edit]Criticism of perennialism has come from academic and traditional religious circles. Academic critiques include the contention that perennialists make ontological claims about Divinity, God(s), and supernatural powers that cannot be verified in practice; and that they take an ahistorical or transhistorical view, overemphasizing similarities and downplaying differences between religions. Craig Martin argues that perennialism involves empirical claims, but that they circumvent those issues and make unfalsifiable claims that resemble the "no true Scotsman" fallacy.[57]

Religious criticism has emerged from within various traditions, including Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism.[58] Tom Facchine argues that by prioritizing mystical experience over revelation and sacred texts, perennialists neglect, ignore, or reinterpret the truth claims found in the religious traditions they are engaged with, or that they interpret or distort the words of some religious historical figures to confirm their own views.[59][60] Gary Stogsdill argues that perennialism can have negative social consequences, perceiving it as anthropocentric and individualistic, and arguing that concepts such as "enlightenment" can be abused by unethical gurus and teachers.[61]

Some thinkers of the Traditionalist School have been criticised for their influence on far-right politics.[62] Julius Evola, in particular, was active in Italian fascist politics during his lifetime and counted Benito Mussolini among his admirers.[63] References to Evola are widespread in the alt-right movement.[64][65] Steve Bannon has called him an influence.[66]

Paul Furlong argues that "Evola's initial writings in the inter-war period were from an ideological position close to the Fascist regime in Italy, though not identical to it". Over his active years, Furlong writes, he "synthesized" spiritual bearings of writers like Guénon with his political concerns of the "European authoritarian Right". Evola tried to develop a tradition different from that of Guénon and thus attempted to develop a "strategy of active revolt as a counterpart to the spiritual withdrawal favoured by Guénon". Evola, as Furlong puts it, wanted to have political influence both in Fascist and Nazi regimes, something which he failed to achieve.[67]

See also

[edit]- Ivan Aguéli

- Aurobindo Ghose

- Alice Bailey

- Suheil Bushrui

- Henry Corbin

- Benjamin Creme

- J. N. Findlay

- Angus Macnab

- Rudolf Otto

- Whitall Perry

- Kathleen Raine

- Religious pluralism

- Helena Roerich

- Edith Stein

- William Stoddart

- The Teachings of the Mystics

- Wilbur Marshall Urban

- R. C. Zaehner

- Educational perennialism

- Urreligion

- Golden Rule

Notes

[edit]- ^ more fully, philosophia perennis et universalis (perennial and universal philosophy); sometimes rendered sophia perennis (perennial wisdom) or religio perennis (perennial religion)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Slavenburg & Glaudemans 1994, p. 395.

- ^ a b c Schmitt 1966, p. 508.

- ^ a b c Schmitt 1966, p. 513.

- ^ a b Schmitt 1966.

- ^ Schmitt 1966, p. 517.

- ^ a b Shipley 2015, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Huxley 1945.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (March–April 1944). "Minimum Working Hypothesis". Vedanta and the West. Hollywood. p. 38.

- ^ King 2000, p. 203.

- ^ Durant & Durant 1966, p. 188-192.

- ^ McEvilley 2002.

- ^ Cahil, Thomas (2006). Mysteries of the Middle Ages. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-0-385-49556-1.

- ^ Schmitt 1966, p. 515.

- ^ a b Schmitt 1966, p. 516.

- ^ De perenni philosophia Bk 1, Ch 1; folio 1 in Schmitt (1966) P.517

- ^ Jamblichi De mysteriis liber, ed. Gustavus Parthey (Berlin), I, 3; 7-10

- ^ Schmitt 1966, p. 527.

- ^ Schmitt 1966, p. 524.

- ^ Schmitt 1966, p. 530-531.

- ^ Schmidt, Leigh Eric. Restless Souls : The Making of American Spirituality. San Francisco: Harper, 2005. ISBN 0-06-054566-6

- ^ Sharf 1995.

- ^ Harding, Mildred D. (1999). "Thomas Carlyle's Sartor Resartus: The Secret Doctrine in a Western Mode". Journal of Religion & Psychical Research. 22 (1): 16.

- ^ Blavatsky, p. 7.

- ^ Prothero 2010, p. 166.

- ^ a b c King 2002.

- ^ Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna

- ^ Prothero 2010, pp. 165–6.

- ^ The Essential Writings of Frithjof Schuon, Suhayl Academy, Lahore, 2001, p.67.

- ^ a b c Lings & Minnaar 2007, p. xii.

- ^ Lings & Minnaar 2007, p. xiii.

- ^ Soares de Azevedo 2005.

- ^ Roy 2003.

- ^ Huxley 1945, p. vii.

- ^ Huxley 1945, p. 2.

- ^ Huxley 1945, p. 3.

- ^ Huxley 1945, p. 6.

- ^ Drury 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Drury 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Drury 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Michael D. Langone, Ph.D. Cult Observer, 1993, Volume 10, No. 1. What Is "New Age"? Archived 2016-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2006-07

- ^ Drury 2004, p. 10.

- ^ a b Smith 1987, p. 554.

- ^ Hori 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Wildman, Wesley J. (2010) Religious Philosophy as Multidisciplinary Comparative Inquiry: Envisioning a Future for the Philosophy of Religion, p. 49, SUNY Press, ISBN 1-4384-3235-6

- ^ Prothero 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Sharf 2000, p. 271.

- ^ Parsons 2011, p. 4-5.

- ^ a b King 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Livingston, James. "Religious Pluralism and the Question of Religious Truth in Wilfred C. Smith." The Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory 4, no. 3 (2003): pp.58-65.

- ^ Bowden, John Stephen. "Perennial Philosophy and Christianity." In Christianity: the complete guide . London: Continuum, 2005. pp.1-5.

- ^ David Lewis-Williams (2009). Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos, and the Realm of the Gods.

- ^ Shapiro, Rami. "Rabbi Rami – Rabbi Rami". Rabbi Rami Shapiro. One River Foundation. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Ramakrishna, Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, trans.Swami Nikhilananda, New York:Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1952, p.111

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Knowledge and the Sacred, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989, p.16-17

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Hallac: Kurtarın Beni Tanrı'dan, çev.G.Ahmetcan Asena, Pan Yayıncılık, 2009,p.62

- ^ Inayat Khan, The Unity of Religious Ideals, Sufi Order Publications, 1979

- ^ Craig Martin, "Yes, ... but ...: The Neo-Perennialists", Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, Vol. 29, Brill, 2017, pp.314-315 [1]

- ^ Problem With Hindu Universalism

- ^ Tom Facchine, "Are All Religions the Same? Islam and the False Promise of Perennialism" False Promise of Perennialism

- ^ "Nuh Ha Mim Keller - On the validity of all religions in the thought of ibn Al-'Arabi and Emir 'Abd al-Qadir: a letter to 'Abd al-Matin". Archived from the original on 2023-10-19. Retrieved 2024-03-11.

- ^ Gary Stogsdill, A Critique of Perennialism: Problems with Enlightenment, Gurus, and Meditation

- ^ Teitelbaum, Benjamin (8 October 2020). "The rise of the traditionalists: how a mystical doctrine is reshaping the right". New Statesman. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (11 February 2017). "Thinker loved by fascists like Mussolini is on Stephen Bannon's reading list". The Boston Globe. The New York Times. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Weitzman 2021.

- ^ Momigliano, Anna (2017-02-21). "The Alt-Right's Intellectual Darling Hated Christianity". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ Rose 2021, p. 41.

- ^ Furlong, Paul: Authoritarian Conservatism After The War Julius Evola and Europe, 2003

Sources

[edit]Printed sources

[edit]- Soares de Azevedo, Mateus (2005), Ye Shall Know the Truth: Christianity and the Perennial Philosophy, World Wisdom, ISBN 0-941532-69-0

- Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna (1889). The Key to Theosophy. Mumbai, India: Theosophy Company (published 1997).

- Drury, Nevill (2004), The New Age: Searching for the Spiritual Self, London, England, UK: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28516-0

- Durant, Will (1966). The Story of Civilization. Volume 2: The Life of Greece. Simon & Schuster.

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1999), Translating the Zen Phrase Book. In: Nanzan Bulletin 23 (1999) (PDF)

- Huxley, Aldous (1945), The Perennial Philosophy (1st ed.), New York: Harper & Brothers

- King, Richard (2002), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- Lings, Martin; Minnaar, Clinton (2007), The Underlying Religion: An Introduction to the Perennial Philosophy, World Wisdom, ISBN 9781933316437

- McEvilley, Thomas (2002), The Shape of Ancient Thought

- Parsons, William B. (2011), Teaching Mysticism, Oxford University Press

- Prothero, Stephen (2010), God is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions That Run the World--and Why Their Differences Matter, HarperOne, ISBN 978-0-06-157127-5

- Roy, Sumita (2003), Aldous Huxley And Indian Thought, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd

- Schmitt, Charles (1966), "Perennial Philosophy: From Agostino Steuco to Leibniz", Journal of the History of Ideas, 27 (1): 505–532), doi:10.2307/2708338, JSTOR 2708338

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995). "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience". Numen. 42 (3): 228–283. doi:10.1163/1568527952598549. hdl:2027.42/43810. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3270219.

- Sharf, Robert H. (2000), "The Rhetoric of Experience and the Study of Religion" (PDF), Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7 (11–12): 267–87, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-13, retrieved 2013-05-04

- Shipley, Morgan (2015), Psychedelic Mysticism: Transforming Consciousness, Religious Experiences, and Voluntary Peasants in Postwar America, Lexington Books

- Slavenburg; Glaudemans (1994), Nag Hammadi Geschriften I, Ankh-Hermes

- Smith, Huston (1987), "Is There a Perennial Philosophy?", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 55 (3): 553–566, doi:10.1093/jaarel/LV.3.553, JSTOR 1464070

Web-sources

[edit]- ^ IEP

- ^ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Transcendentalism

- ^ a b c d "Jone John Lewis, What is Transcendentalism?". Archived from the original on 2013-12-09. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

- ^ Barry Andrews, THE ROOTS OF UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST SPIRITUALITY IN NEW ENGLAND TRANSCENDENTALISM Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Melton, J. Gordon – Director Institute for the Study of American Religion. New Age Transformed, retrieved 2006-06

- ^ Gellman, Jerome, "Mysticism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

Further reading

[edit]- Aldous Huxley, The Perennial Philosophy, Harper Perennial Modern Classics (January 1, 2009) ISBN 978-0061724947

- Frithjof Schuon, Transcendent Unity of Religions (Quest Book) Paperback – January 1, 1984 ISBN 978-0835605878

- William W. Quinn, junior. The Only Tradition, in S.U.N.Y. Series in Western Esoteric Traditions. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1997. xix, 384 p. ISBN 0-7914-3214-9 pbk

- Samuel Bendeck Sotillos (ed.), Psychology and the Perennial Philosophy in Studies in Comparative Religion (Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom Books, 2013). ISBN 978-1-936597-20-8

- Zachary Markwith, "Muslim Intellectuals and the Perennial Philosophy in the Twentieth Century", Sophia Perennis Vol. 1, N° 1 (Tehran: Iranian Institute of Philosophy, 2009).

- Inayat Khan, The Unity of Religious Ideals, Sufi Order Publications, 1979.

.jpg/250px-ARO_Plate_2_(Title_page_alternate).jpg)

.jpg)