Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pulp (paper)

View on Wikipedia

Pulp is a fibrous lignocellulosic material prepared by chemically, semi-chemically, or mechanically isolating the cellulosic fibers of wood, fiber crops, waste paper, or rags. Mixed with water and other chemicals or plant-based additives, pulp is the major raw material used in papermaking and the industrial production of other paper products.[1][2]

History

[edit]Before the widely acknowledged invention of papermaking by Cai Lun in China around AD 105, paper-like writing materials such as papyrus and amate were produced by ancient civilizations using plant materials which were largely unprocessed. Strips of bark or bast material were woven together, beaten into rough sheets, dried, and polished by hand.[3][4] Pulp used in modern and traditional papermaking is distinguished by the maceration process which produces a finer, more regular slurry of cellulose fibers which are pulled out of solution by a screen and dried to form sheets or rolls.[5] The earliest paper produced in China consisted of bast fibers from the paper mulberry (kozo) plant along with hemp rag and net scraps.[5][6][7] By the 6th century, the mulberry tree was domesticated by farmers in China specifically for the purpose of producing pulp to be used in the papermaking process. In addition to mulberry, pulp was also made from bamboo, hibiscus bark, blue sandalwood, straw, and cotton.[7] Papermaking using pulp made from hemp and linen fibers from tattered clothing, fishing nets and fabric bags spread to Europe in the 13th century, with an ever-increasing use of rags being central to the manufacture and affordability of rag paper, a factor in the development of printing.[1] By the 1800s, production demands on the newly industrialized papermaking and printing industries led to a shift in raw materials, most notably the use of pulpwood and other tree products which today make up more than 95% of global pulp production.[8]

The use of wood pulp and the invention of automatic paper machines in the late 18th- and early 19th-century contributed to paper's status as an inexpensive commodity in modern times.[1][9][10] While some of the earliest examples of paper made from wood pulp include works published by Jacob Christian Schäffer in 1765 and Matthias Koops in 1800,[1][11] large-scale wood paper production began in the 1840s with unique, simultaneous developments in mechanical pulping made by Friedrich Gottlob Keller in Germany[12] and by Charles Fenerty in Nova Scotia.[9] Chemical processes quickly followed, first with J. Roth's use of sulfurous acid to treat wood, then by Benjamin Tilghman's U.S. patent on the use of calcium bisulfite, Ca(HSO3)2, to pulp wood in 1867.[2] Almost a decade later, the first commercial sulfite pulp mill was built, in Sweden. It used magnesium as the counter ion and was based on work by Carl Daniel Ekman. By 1900, sulfite pulping had become the dominant means of producing wood pulp, surpassing mechanical pulping methods. The competing chemical pulping process, the sulfate, or kraft, process, was developed by Carl F. Dahl in 1879; the first kraft mill started, in Sweden, in 1890.[2] The invention of the recovery boiler, by G.H. Tomlinson in the early 1930s,[12] allowed kraft mills to recycle almost all of their pulping chemicals. This, along with the ability of the kraft process to accept a wider variety of types of wood and to produce stronger fibres,[13] made the kraft process the dominant pulping process, starting in the 1940s.[2]

Global production of wood pulp in 2006 was 175 million tons (160 million tonnes).[14] In the previous year, 63 million tons (57 million tonnes) of market pulp (not made into paper in the same facility) was sold, with Canada being the largest source at 21 percent of the total, followed by the United States at 16 percent. The wood fiber sources required for pulping are "45% sawmill residue, 21% logs and chips, and 34% recycled paper" (Canada, 2014).[15] Chemical pulp made up 93% of market pulp.[16]

Wood pulp

[edit]

The timber resources used to make wood pulp are referred to as pulpwood.[17] While in theory any tree can be used for pulp-making, coniferous trees are preferred because the cellulose fibers in the pulp of these species are longer, and therefore make stronger paper.[18] Some of the most commonly used trees for paper making include softwoods such as spruce, pine, fir, larch and hemlock, and hardwoods such as eucalyptus, aspen and birch.[19] There is also increasing interest in genetically modified tree species (such as GM eucalyptus and GM poplar) because of several major benefits these can provide, such as increased ease of breaking down lignin and increased growth rate.

A pulp mill is a manufacturing facility that converts wood chips or other plant fibre source into a thick fiberboard which can be shipped to a paper mill for further processing. Pulp can be manufactured using mechanical, semi-chemical or fully chemical methods (kraft and sulfite processes). The finished product may be either bleached or non-bleached, depending on the customer requirements.

Wood and other plant materials used to make pulp contain three main components (apart from water): cellulose fibers (desired for papermaking), lignin (a three-dimensional polymer that binds the cellulose fibres together) and hemicelluloses (shorter branched carbohydrate polymers). The aim of pulping is to break down the bulk structure of the fibre source, be it chips, stems or other plant parts, into the constituent fibres.

Chemical pulping achieves this by degrading the lignin and hemicellulose into small, water-soluble molecules which can be washed away from the cellulose fibres without depolymerizing the cellulose fibres (chemically depolymerizing the cellulose weakens the fibres). The various mechanical pulping methods, such as groundwood (GW) and refiner mechanical pulping (RMP), physically tear the cellulose fibres one from another. Much of the lignin remains adhering to the fibres. Strength is impaired because the fibres may be cut. There are a number of related hybrid pulping methods that use a combination of chemical and thermal treatment to begin an abbreviated chemical pulping process, followed immediately by a mechanical treatment to separate the fibres. These hybrid methods include thermomechanical pulping, also known as TMP, and chemithermomechanical pulping, also known as CTMP. The chemical and thermal treatments reduce the amount of energy subsequently required by the mechanical treatment, and also reduce the amount of strength loss suffered by the fibres.

| Pulp category | Production [M ton] |

| Chemical | 131.2 |

| Kraft | 117.0 |

| Sulfite | 7.0 |

| Semichemical | 7.2 |

| Mechanical | 37.8 |

| Nonwood | 18.0 |

| Total virgin fibres | 187.0 |

| Recovered fibres | 147.0 |

| Total pulp | 334.0 |

Harvesting trees

[edit]Most pulp mills use good forest management practices in harvesting trees to ensure that they have a sustainable source of raw materials. One of the major complaints about harvesting wood for pulp mills is that it reduces the biodiversity of the harvested forest. Pulp tree plantations account for 16 percent of world pulp production, old-growth forests 9 percent, and second- and third- and more generation forests account for the rest.[21] Reforestation is practiced in most areas, so trees are a renewable resource. The FSC (Forest Stewardship Council), SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification), and other bodies certify paper made from trees harvested according to guidelines meant to ensure good forestry practices.[22]

The number of trees consumed depends on whether mechanical processes or chemical processes are used. It has been estimated that based on a mixture of softwoods and hardwoods 12 metres (40 ft) tall and 15–20 centimetres (6–8 in) in diameter, it would take an average of 24 trees to produce 0.9 tonne (1 ton) of printing and writing paper, using the kraft process (chemical pulping). Mechanical pulping is about twice as efficient in using trees, since almost all of the wood is used to make fibre, therefore it takes about 12 trees to make 0.9 tonne (1 ton) of mechanical pulp or newsprint.[23]

There are roughly two short tons in a cord of wood.[24]

Preparation for pulping

[edit]Wood chipping is the act and industry of chipping wood for pulp, but also for other processed wood products and mulch. Only the heartwood and sapwood are useful for making pulp. Bark contains relatively few useful fibers and is removed and used as fuel to provide steam for use in the pulp mill. Most pulping processes require that the wood be chipped and screened to provide uniform sized chips.

Pulping

[edit]There are a number of different processes which can be used to separate the wood fiber:

Mechanical pulp

[edit]Manufactured grindstones with embedded silicon carbide or aluminum oxide can be used to grind small wood logs called "bolts" to make stone pulp (SGW). If the wood is steamed prior to grinding it is known as pressure ground wood pulp (PGW). Most modern mills use chips rather than logs and ridged metal discs called refiner plates instead of grindstones. If the chips are just ground up with the plates, the pulp is called refiner mechanical pulp (RMP) and if the chips are steamed while being refined the pulp is called thermomechanical pulp (TMP). Steam treatment significantly reduces the total energy needed to make the pulp and decreases the damage (cutting) to fibres. Mechanical pulps are used for products that require less strength, such as newsprint and paperboards.

Thermomechanical pulp

[edit]

Thermomechanical pulp is pulp produced by processing wood chips using heat (thus "thermo-") and a mechanical refining movement (thus "-mechanical"). It is a two-stage process where the logs are first stripped of their bark and converted into small chips. These chips have a moisture content of around 25–30 percent. A mechanical force is applied to the wood chips in a crushing or grinding action which generates heat and water vapour and softens the lignin thus separating the individual fibres. The pulp is then screened and cleaned, any clumps of fibre are reprocessed. This process gives a high yield of fibre from the timber (around 95 percent) and as the lignin has not been removed, the fibres are hard and rigid.[25]

Chemi-thermomechanical pulp

[edit]Wood chips can be pre-treated with sodium carbonate, sodium hydroxide, sodium sulfate and other chemicals prior to refining with equipment similar to a mechanical mill. The conditions of the chemical treatment are much less vigorous (lower temperature, shorter time, less extreme pH) than in a chemical pulping process since the goal is to make the fibers easier to refine, not to remove lignin as in a fully chemical process. Pulps made using these hybrid processes are known as chemi-thermomechanical pulps (CTMP).

Chemical pulp

[edit]

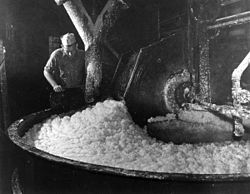

Chemical pulp is produced by combining wood chips and chemicals in large vessels called digesters. There, heat and chemicals break down lignin, which binds cellulose fibres together, without seriously degrading the cellulose fibres. Chemical pulp is used for materials that need to be stronger or combined with mechanical pulps to give a product different characteristics. The kraft process is the dominant chemical pulping method, with the sulfite process second. Historically soda pulping was the first successful chemical pulping method.

Recycled pulp

[edit]Recycled pulp is also called deinked pulp (DIP). DIP is recycled paper which has been processed by chemicals, thus removing printing inks and other unwanted elements and freeing the paper fibres. The process is called deinking.

DIP is used as raw material in papermaking. Many newsprint, toilet paper and facial tissue grades commonly contain 100 percent deinked pulp and in many other grades, such as lightweight coated for offset and printing and writing papers for office and home use, DIP makes up a substantial proportion of the furnish.

Organosolv pulping

[edit]Organosolv pulping uses organic solvents at temperatures above 140 °C to break down lignin and hemicellulose into soluble fragments. The pulping liquor is easily recovered by distillation. The reason for using a solvent is to make the lignin more soluble in the cooking liquor. Most common used solvents are methanol, ethanol, formic acid and acetic acid often in combination with water.

Alternative pulping methods

[edit]Research is under way to develop biopulping (biological pulping), similar to chemical pulping but using certain species of fungi that are able to break down the unwanted lignin, but not the cellulose fibres.[26] In the biopulping process, the fungal enzyme lignin peroxidase selectively digests lignin to leave remaining cellulose fibres. This could have major environmental benefits in reducing the pollution associated with chemical pulping. The pulp is bleached using chlorine dioxide stage followed by neutralization and calcium hypochlorite. The oxidizing agent in either case oxidizes and destroys the dyes formed from the tannins of the wood and accentuated (reinforced) by sulfides present in it.

Steam exploded fibre is a pulping and extraction technique that has been applied to wood and other fibrous organic material.[27]

Bleaching

[edit]The pulp produced up to this point in the process can be bleached to produce a white paper product. The chemicals used to bleach pulp have been a source of environmental concern, and recently the pulp industry has been using alternatives to chlorine, such as chlorine dioxide, oxygen, ozone and hydrogen peroxide.

Alternatives to wood pulp

[edit]Pulp made from non-wood plant sources or recycled textiles is manufactured today largely as a speciality product for fine-printing and art purposes.[8] Modern machine- and hand-made art papers made with cotton, linen, hemp, abaca, kozo, and other fibers are often valued for their longer, stronger fibers and their lower lignin content. Lignin, present in virtually all plant materials, contributes to the acidification and eventual breakdown of paper products, often characterized by the browning and embrittling of paper with a high lignin content such as newsprint.[28][29] 100% cotton or a combination of cotton and linen pulp is widely used to produce documents intended for long-term use, such as certificates, currency, and passports.[30][31][32]

Today, some groups advocate using field crop fibre or agricultural residues instead of wood fibre as a more sustainable means of production.[citation needed]

There is enough straw to meet much of North America's book, magazine, catalogue and copy paper needs.[citation needed] Agricultural-based paper does not come from tree farms. Some agricultural residue pulps take less time to cook than wood pulps. That means agricultural-based paper uses less energy, less water and fewer chemicals. Pulp made from wheat and flax straw has half the ecological footprint of pulp made from forests.[33]

Hemp paper is a possible replacement, but processing infrastructure, storage costs and the low usability percentage of the plant means it is not a ready substitute.[citation needed]

However, wood is also a renewable resource, with about 90 percent of pulp coming from plantations or reforested areas.[21] Non-wood fibre sources account for about 5–10 percent of global pulp production, for a variety of reasons, including seasonal availability, problems with chemical recovery, brightness of the pulp etc.[16][34] In China, as of 2009, a higher proportion of non-wood pulp processing increased use of water and energy.[35]

Nonwovens are in some applications alternatives to paper made from wood pulp, like filter paper or tea bags.

| Component | Wood | Nonwood |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | 65–80% | 50–80% |

|

40–45% | 30–45% |

|

23–35% | 20–35% |

| Lignin | 20–30% | 10–25% |

| Extractives | 2–5% | 5–15% |

| Proteins | <0.5% | 5–10% |

| Inorganics | 0.1–1% | 0.5–10% |

|

<0.1% | 0.5–7% |

Market pulp

[edit]Market pulp is any variety of pulp that is produced in one location, dried and shipped to another location for further processing.[37] Important quality parameters for pulp not directly related to the fibres are brightness, dirt levels, viscosity and ash content. In 2004 it accounted for about 55 million metric tons of market pulp.[37]

Air dry pulp is the most common form to sell pulp. This is pulp dried to about 10 percent moisture content. It is normally delivered as sheeted bales of 250 kg. The reason to leave 10 percent moisture in the pulp is that this minimizes the fibre to fibre bonding and makes it easier to disperse the pulp in water for further processing to paper.[37]

Roll pulp or reel pulp is the most common delivery form of pulp to non traditional pulp markets. Fluff pulp is normally shipped on rolls (reels). This pulp is dried to 5–6 percent moisture content. At the customer this is going to a comminution process to prepare for further processing.[37]

Some pulps are flash dried. This is done by pressing the pulp to about 50 percent moisture content and then let it fall through silos that are 15–17 m high. Gas fired hot air is the normal heat source. The temperature is well above the char point of cellulose, but large amount of moisture in the fibre wall and lumen prevents the fibres from being incinerated. It is often not dried down to 10 percent moisture (air dry). The bales are not as densely packed as air dry pulp.[37]

Environmental concerns

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Environmental issues with paper. (Discuss) (September 2025) |

The major environmental impacts of producing wood pulp come from its impact on forest sources and from its waste products.

Forest resources

[edit]The impact of logging to provide the raw material for wood pulp is an area of intense debate. Modern logging practices, using forest management seek to provide a reliable, renewable source of raw materials for pulp mills. The practice of clear cutting is a particularly sensitive issue since it is a very visible effect of logging. Reforestation, the planting of tree seedlings on logged areas, has also been criticized for decreasing biodiversity because reforested areas are monocultures. Logging of old growth forests accounts for less than 10 percent of wood pulp,[21] but is one of the most controversial issues.

Effluents from pulp mills

[edit]The process effluents are treated in a biological effluent treatment plant, which guarantees that the effluents are not toxic in the recipient.

Mechanical pulp is not a major cause for environmental concern since most of the organic material is retained in the pulp, and the chemicals used (hydrogen peroxide and sodium dithionite) produce benign byproducts (water and sodium sulfate (finally), respectively).

Chemical pulp mills, especially kraft mills, are energy self-sufficient and very nearly closed cycle with respect to inorganic chemicals.

Bleaching with chlorine produces large amounts of organochlorine compounds, including polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs).[38][39] Many mills have adopted alternatives to chlorinated bleaching agents thereby reducing emissions of organochlorine pollution.[40]

Odor problems

[edit]The kraft pulping reaction in particular releases foul-smelling compounds. The sulfide reagent that degrades lignin structure also causes some demethylation, yielding methanethiol, dimethyl sulfide, and dimethyl disulfide.[41] These same compounds are released during many forms of microbial decay, including the internal microbial action in Camembert cheese, although the kraft process is a chemical one and does not involve any microbial degradation. These compounds have extremely low odor thresholds and disagreeable smells.

Applications

[edit]The main applications for pulp are paper and board production. The furnish of pulps used depends on the quality on the finished paper. Important quality parameters are wood furnish, brightness, viscosity, extractives, dirt count and strength.

Chemical pulps are used for making nanocellulose.[citation needed]

Speciality pulp grades have many other applications. Dissolving pulp is used in making regenerated cellulose that is used textile and cellophane production. It is also used to make cellulose derivatives. Fluff pulp is used in diapers, feminine hygiene products and nonwovens.

Paper production

[edit]The Fourdrinier Machine is the basis for most modern papermaking[42], and it has been used in some variation since its conception. It accomplishes all the steps needed to transform pulp into a final paper product.

Economics

[edit]In 2009, NBSK pulp sold for $650/ton in the United States. The price had dropped due to falling demand when newspapers reduced their size, in part, as a result of the recession.[43] By 2024 this price had recovered to $1315/ton.[44]

See also

[edit]- Nanocellulose

- Paper chemicals

- Pulp mill

- Pulpwood

- Tree-free paper

- Johan Richter, developer of the process for continuous cooking of pulp

- World Forestry Congress

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Hunter, Dard (1943). Papermaking, the history and technique of an ancient craft. Dover.

- ^ a b c d Biermann, Christopher J. (1993). Handbook of Pulping and Papermaking. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-097360-X.

- ^ Spivey, Nigel (November 1987). "J. Swaddling (Ed.), Italian Iron Age Artefacts in the British Museum: Papers of the Sixth British Museum Classical Colloquium. London: British Museum, 1986. Pp x + 483, numerous illus. (incl. pls, text figs). ISBN 0-7141-1274-7". Journal of Roman Studies. 77: 267–268. doi:10.2307/300639. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 300639. S2CID 162420219.

- ^ "El Dialogo en la Historia Hispanoamericana", El diálogo en el español de América, Iberoamericana Vervuert, pp. 71–92, 1998-12-31, doi:10.31819/9783865278364-004, ISBN 978-3-86527-836-4

- ^ a b "papermaking | Process, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ^ Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985), Paper and Printing, Science and Civilisation in China: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, vol. 5 Part 1, Cambridge University Press, p. 4

- ^ a b Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985), Paper and Printing, Science and Civilisation in China: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, vol. 5 Part 1, Cambridge University Press, pp. 56–61

- ^ a b Bowyer, Jim (August 19, 2014). "Tree-free Paper: A Path to Saving Trees and Forests?" (PDF). Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Burger, PeterCharles Fenerty and his Paper Invention. Toronto: Peter Burger, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9783318-1-8 pp.25–30

- ^ Ragnar, Martin; Henriksson, Gunnar; Lindström, Mikael E.; Wimby, Martin; Blechschmidt, Jürgen; Heinemann, Sabine (2014-05-30), "Pulp", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, pp. 1–92, doi:10.1002/14356007.a18_545.pub4, ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2

- ^ Leong, Elaine (2016). "An Early Modern DIY Guide to Making Paper". The Recipes Project. doi:10.58079/tcxz. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ^ a b Sjöström, E. (1993). Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications. Academic Press.

- ^ History of Paper. indiapapermarket.com

- ^ "Pulp production growing in new areas (Global production)". Metso Corporation. September 5, 2006. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ^ Sixta, Herbert (2006). "Preface". Handbook of Pulp. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH Verlag & Co KGaA. p. XXIII. ISBN 3-527-30999-3.

- ^ a b "Overview of the Wood Pulp Industry". Market Pulp Association. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ^ Manthy, Robert S.; James, Lee Morton; Huber, Henry H. (1973). Michigan Timber Production: Now and in 1985. Michigan State University, Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension service.

- ^ "Paper". How Products are Made.

- ^ Geman, Helyette (2014-12-29). Agricultural Finance: From Crops to Land, Water and Infrastructure. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118827376.

- ^ Sixta, Herbert, ed. (2006). Handbook of pulp. Vol. 1. Winheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. p. 9. ISBN 3-527-30997-7.

- ^ a b c Martin, Sam (2004). "Paper Chase". Ecology Communications, Inc. Archived from the original on 2007-06-19. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ "Certification Tracking products from the forest to the shelf". Archived from the original on 2007-08-26. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ Trees Into Paper. Conservatree. Retrieved on 2017-01-09.

- ^ "dead link". Archived from the original on 2008-12-25. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ a b Paperboard the Iggesund Way (Report). Iggesund Paperboard AB. 2008. p. 15. Archived from the original on 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ Husaini, Ahmad; Fisol, Faisalina Ahmad; Yun, Liew Chia; Hussain, Mohd Hasnain; Muid, Sepiah; Roslan, Hairul Azman (2011). "Lignocellulolytic enzymes produced by tropical white rot fungi during biopulping of Acacia mangium wood chips". J Biochem Tech. 3 (2): 245–250. Archived from the original on 2017-01-09. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ Avella, Maurizio; Bozzi, Claudio; Dell'Erba, Ramiro; Focher, Bonaventura; Marzetti, Annamaria; Martuscelli, Ezio (November 1995). "Steam-exploded wheat straw fibres as reinforcing material for polypropylene-based composites. Characterization and properties". Angewandte Makromolekulare Chemie. 233 (1): 149–166. doi:10.1002/apmc.1995.052330113.

- ^ McCrady, Ellen (November 1991). "The Nature of Lignin". cool.culturalheritage.org. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ^ Burge, Daniel M. (2002). "Effects of enclosure papers and paperboards containing lignins on photographic image stability". cool.culturalheritage.org. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ^ "Markets". delarue.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-13. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "Banknotes design and production". Bank of Canada. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ "How Money is Made – Paper and Ink". Bureau of Engraving and Printing U.S. Department of the Treasury. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ "Canopy's Straw Paper Campaign". canopyplanet.org. Archived from the original on 2013-09-03.

- ^ Judt, Manfred (Oct–Dec 2001). "Nonwoody Plant Fibre Pulps". Inpaper International. Archived from the original on 2007-11-20. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ 造纸企业能入“绿色之门”的前提 南粤大地 南方网. News.southcn.com (2009-07-20). Retrieved on 2017-01-09.

- ^ Stenius, Per (2000). "1". PForest Products Chemistry. Papermaking Science and Technology. Vol. 3. Finland: Fapet Oy. p. 29. ISBN 952-5216-03-9.

- ^ a b c d e Nanko, Hirko; Button, Allan; Hillman, Dave (2005). The World of Market Pulp. Appleton, Wisconsin, US: WOMP, LLC. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-615-13013-5.

- ^ Hoffman, Emma; Alimohammadi, Masi; Lyons, James; Davis, Emily; Walker, Tony R.; Lake, Craig B. (2019-08-23). "Characterization and spatial distribution of organic-contaminated sediment derived from historical industrial effluents". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 191 (9): 590. Bibcode:2019EMnAs.191..590H. doi:10.1007/s10661-019-7763-y. ISSN 1573-2959. PMID 31444645.

- ^ Effluents from Pulp Mills using Bleaching – PSL1. Health Canada. 1991. ISBN 0-662-18734-2. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ Auer, Matthew R. (2010-03-01). "Better science and worse diplomacy: negotiating the cleanup of the Swedish and Finnish pulp and paper industry". International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics. 10 (1): 65–84. Bibcode:2010IEAPL..10...65A. doi:10.1007/s10784-009-9112-z. ISSN 1573-1553.

- ^ Hansen, G. A. (1962). "Odor and Fallout Control in a Kraft Pulp Mill". Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association. 12 (9): 409–436. doi:10.1080/00022470.1962.10468107. PMID 13904415.

- ^ Hubbe, Martin A.; Madappa, Kavya (2024-08-01). "Contemporary papermaking in the tradition of Mahatma Gandhi". BioResources. 19 (4): 6979–6982. doi:10.15376/biores.19.4.6979-6982.

- ^ Lefebrvre, Paul (February 4, 2009). Wood products market looks soft. The Chronicle.

- ^ "Current Lumber Pulp Panel Prices". Natural Resources Canada/Our Natural Resources/Domestic and international markets. Government of Canada. 2024-01-17. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Pulp and Paper", Environment Canada, Government of Canada, 2014, archived from the original on 2016-04-21, retrieved 2014-03-31

- Schäffer, Jacob Christian (1765). Versuche und Muster ohne alle Lumpen oder doch mit enem geringen Zusatze derselben Papier zu machen.

Pulp (paper)

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Pre-Industrial Methods

The origins of paper pulp trace to ancient China, where court official Cai Lun is credited with refining papermaking techniques around 105 AD by combining mulberry tree bark, hemp fibers, old rags, and fishnets with water to create a fibrous slurry, or pulp, suitable for forming sheets.[4] This method built on earlier rudimentary practices using hemp waste, which was soaked, washed, and manually beaten with wooden mallets to break down fibers into a pulp suspension, enabling more efficient production than prior materials like silk or bamboo slips.[5] The process involved macerating the raw materials to separate cellulose fibers, suspending them in water, and agitating to achieve a uniform consistency before manual sheet formation, marking the first systematic approach to pulp preparation from disparate plant and textile sources.[6] Papermaking and pulp methods spread from China to Korea by the 6th century AD, where similar manual beating of hemp, rattan, and mulberry fibers produced pulp, and further to Japan via Buddhist monks in the 7th century, incorporating local plant materials like gampi bark.[5] By the 8th century, the technology reached the Islamic world in Samarkand (modern Uzbekistan), where captured Chinese papermakers introduced early water-powered mechanisms for pulp preparation, such as trip-hammers to beat fibers, transitioning from fully manual labor while still relying on rags and plant scraps rather than wood.[7] These pre-industrial techniques emphasized labor-intensive fiber defibrillation to yield high-quality, durable pulp, limited by the scarcity of raw materials and yielding outputs far below later mechanized scales. In medieval Europe, paper production began in the 11th century via Moorish Spain, with the first mill established in Xàtiva around 1050, using imported techniques but adapting to local linen and cotton rags as primary pulp sources due to the absence of abundant wood pulping knowledge.[8] Rags were sorted by fabric type and quality, dampened and allowed to ferment or "rot" for 4 to 5 days to weaken non-cellulosic impurities, then boiled in alkaline solutions like lime or wood ash lye to cleanse and soften fibers.[9] The softened rags underwent prolonged beating—initially by hand in mortars but increasingly via water-powered stamp mills with wooden mallets or hammers from the 13th century onward—to fibrillate and shorten fibers into a watery pulp, a process requiring 12 to 48 hours per batch depending on equipment.[8] This rag-based pulp preparation dominated European methods through the 18th century, constrained by rag supply shortages that drove prices high and limited paper availability, until wood-based innovations emerged in the 19th century.[10]19th Century Mechanization

The mechanization of pulp production accelerated in the 19th century amid surging paper demand from continuous-sheet papermaking machines, which by 1825 accounted for 50 percent of England's paper supply and exhausted traditional rag supplies obtained from textile waste.[11] This scarcity prompted innovation in wood-based pulping to replace labor-intensive rag beating in hollandered beaters, enabling scalable fiber preparation through mechanical means.[12] In 1843, German inventor Friedrich Gottlob Keller developed the first practical wood-grinding machine, producing groundwood pulp by abrading debarked logs against a rotating grindstone under water to separate lignin-bound fibers mechanically without chemical dissolution.[13] Keller patented this in 1844 and sold rights to Heinrich Voelter, who established the first commercial groundwood mill near Heilbronn, Germany, in 1847, yielding pulp suitable for newsprint and lower-grade papers despite its shorter fiber length and higher lignin content compared to rag pulp.[14] Independently, Canadian Charles Fenerty experimented with wood grinding around 1841, producing experimental sheets, but lacked a patented machine for industrial replication, underscoring Keller's device's causal role in mechanized adoption.[15] Mechanical pulping spread to North America, with the first U.S. groundwood mill operational in 1867 at Fitchburg, Massachusetts, using spruce and fir woods to meet expanding print media needs.[16] By the 1870s, groundwood processes dominated low-cost pulp production, though initial outputs were coarse and prone to yellowing due to retained lignin, limiting use to temporary products; this mechanization reduced costs dramatically, dropping newsprint prices from $0.01 per pound in the 1860s to under $0.005 by century's end through higher throughput via steam-powered grinders.[12] Parallel early chemical efforts, such as soda pulping experiments by American Hugh Burgess in 1851, began delignifying wood via caustic solutions but remained secondary to mechanical methods until refined in the 1860s.[12]20th Century Chemical and Scale Advancements

Refinements to the kraft pulping process in the early 20th century focused on enhancing chemical recovery from black liquor, the byproduct containing dissolved lignin and spent cooking chemicals. Advances in evaporation techniques and recovery furnace design during the 1920s and 1930s enabled more efficient combustion of black liquor solids, recovering up to 95% of pulping chemicals while generating steam and power for mill operations.[17] These improvements addressed earlier limitations in chemical recycling, making the alkaline kraft liquor—comprising sodium hydroxide and sodium sulfide—more economically viable compared to the acidic sulfite processes. By the 1940s, kraft pulping had overtaken sulfite as the leading chemical method, producing stronger fibers suitable for a wider range of paper grades.[18] Bleaching advancements shifted from rudimentary single-stage hypochlorite treatments in the early 1900s to multi-stage sequences by mid-century, incorporating chlorine gas for delignification and hypochlorite for brightening. The introduction of chlorine dioxide in the 1940s, patented for pulp applications around 1944, marked a key development, as it provided selective bleaching that preserved fiber strength while achieving higher brightness levels with reduced chemical consumption.[19] By the 1980s, approximately 88% of bleached chemical pulp worldwide derived from kraft processes, often using chlorine dioxide in later stages to minimize residual lignin and improve pulp quality.[20] Scaling efforts emphasized continuous processing and larger facilities to boost output efficiency. The adoption of continuous digesters in the 1950s and 1960s replaced batch systems, allowing steady-state operation and capacities exceeding 1,000 tons per day in major mills. U.S. wood pulp production expanded throughout most of the century, driven by these technological shifts and rising demand, with mill sizes growing from averages of 25 tons per day in the late 19th century to integrated complexes handling thousands of tons daily by the late 20th century.[21] Economies of scale further concentrated production in capital-intensive operations, where vertical integration of pulping, recovery, and papermaking reduced unit costs.[22] This era's innovations laid the foundation for the industry's dominance in chemical pulp, comprising over 70% of global production by 2000.[23]Post-2000 Innovations and Sustainability Shifts

Since the early 2000s, the pulp industry has increasingly incorporated biotechnological processes, particularly enzymatic treatments, to enhance efficiency and reduce environmental impacts during pulping and refining. Cellulases and xylanases have been applied to modify pulp fibers, improving drainage, reducing refining energy by up to 20-30% in some cases, and enabling milder mechanical treatments without compromising fiber strength.[24] These enzymes facilitate selective hydrolysis of hemicelluloses and surface fibrils, leading to better papermaking properties in both chemical and mechanical pulps.[25] By 2010, commercial adoption of such biocatalysts had expanded to deinking recycled pulp, where lipases and esterases break down pitch and contaminants, minimizing adhesive-related defects and chemical usage.[26] Nanocellulose extraction from pulp fibers emerged as a key innovation around the mid-2000s, leveraging mechanical fibrillation and chemical pretreatment of wood-derived cellulose to produce nanofibrils and nanocrystals with tensile strengths exceeding 200 GPa and high aspect ratios.[27] This material, derived directly from kraft or sulfite pulps, offers renewable alternatives to synthetic polymers in applications like barrier coatings and composites, with pilot-scale production reaching commercial viability by 2015 in facilities processing up to 1,000 tons annually.[28] Integration of nanocellulose back into pulp streams has improved paper strength and reduced basis weight needs, supporting lightweighting in packaging while maintaining recyclability.[29] Sustainability efforts post-2000 have centered on resource optimization, with global pulp mills achieving average energy reductions of 1-2% annually through process integrations like combined heat and power from black liquor recovery boilers, which now generate over 50% of mill energy in many operations.[30] Water consumption has dropped by approximately 40% in integrated mills via closed-loop systems and membrane technologies, limiting freshwater intake to under 10 m³ per ton of pulp in advanced facilities by 2020.[31] These shifts, driven by regulatory pressures and certification standards like FSC and PEFC, have enabled the industry to project net-zero CO₂ emissions before 2050 through biomass utilization and carbon capture from gasification processes.[32] However, challenges persist in scaling negative emissions via bioenergy with carbon capture, as adoption varies by region due to infrastructure costs.[32]Raw Materials

Wood Fibers and Sourcing

Wood fibers, the primary raw material for pulp production, consist mainly of cellulose (approximately 40-50%), hemicellulose (20-30%), and lignin (20-35%), with minor extractives. Cellulose forms the structural backbone, providing fiber strength and length, while lignin acts as a binder but must be largely removed during pulping to avoid brittleness; hemicellulose contributes to fiber flexibility but degrades under processing.[33][34] Softwood fibers from coniferous trees, such as pine, spruce, and fir, typically measure 3-4 mm in length, offering high tensile strength and durability suitable for products like packaging and newsprint. Hardwood fibers from deciduous species, including birch, eucalyptus, and poplar, are shorter (around 1 mm), yielding smoother, more opaque sheets ideal for tissue and fine papers. Globally, pulp fibers derive from roughly 35% softwood and 65% hardwood sources, often blended to balance strength and printability.[35][36][37] Sourcing occurs predominantly from managed forests and plantations, with the industry consuming about 213 million metric tons of wood annually as of 2024. In North America, key softwood species include southern pines (e.g., loblolly, slash) and Douglas fir; hardwoods feature poplar and alder. Europe relies on spruce and pine, while Asia favors fast-growing eucalyptus plantations. The Americas led production with nearly 94 million metric tons in 2023, followed by Europe and Asia.[38][39][40][41] Practices emphasize plantations for efficiency, as seen in eucalyptus sourcing, which reduces pressure on natural forests but has raised concerns over biodiversity loss in conversion areas. Major producers trace supply chains to certified managed forests, though global trade in wood pulp reached higher volumes despite a 2% production dip to 193 million tonnes recently, reflecting demand from integrated mills.[42][43][44]Harvesting Practices and Forest Management

Clearcutting predominates in harvesting pulpwood from managed plantations and even-aged stands, as it suits the regeneration requirements of fast-growing, light-demanding species like pines and eucalypts used in pulp production.[45][46] This method removes all trees in a defined area to promote uniform regrowth, contrasting with selective harvesting more common for high-value sawtimber.[45] In tree-length systems typical for pulpwood, trees are felled, topped, and delimbed on-site before bundling and transport to mills, minimizing roadside processing.[47] Forest management for pulp emphasizes intensive silviculture on dedicated plantations, which supply the majority of global pulp fiber and reduce reliance on natural forests.[44] Common species include Eucalyptus spp. with rotations of 6-8 years for pulpwood in suitable climates, and southern pines like loblolly (Pinus taeda) harvested at 20-25 years.[48][49] Practices involve site preparation via mechanical or chemical means, planting at high densities (e.g., 1,000-2,000 stems per hectare), and optional thinning to optimize growth before final harvest.[50] Rotation lengths balance yield, wood quality, and soil nutrient sustainability, with shorter cycles in tropical plantations enabling annual fiber production comparable to agricultural crops.[51] Regeneration follows harvest promptly, with artificial planting of seedlings within 1-2 years in clearcut areas to ensure rapid canopy closure and soil protection.[52] In the United States, where much pulpwood derives from private lands, annual wood growth exceeds removals by approximately 2:1, supporting sustained yields under even-aged management.[53] Certification schemes like SFI, ATFS, FSC, and PEFC cover over 99% of fiber sourced by major U.S. paper producers, enforcing standards for replanting, stream protection via buffer zones, and biodiversity retention through set-asides.[53][54] While plantations enhance fiber efficiency and offset natural forest logging, their monocultural nature can limit local biodiversity relative to diverse ecosystems, though edge effects and retained habitats mitigate this in certified operations.[44] Empirical data from managed southern U.S. pine stands show successful regeneration rates exceeding 90% post-clearcut when followed by prescribed burns or herbicides to control competition.[55] Globally, the pulp sector's shift toward short-rotation plantations has stabilized wood supply amid rising demand, with Latin American eucalypt operations exemplifying high-yield cycles that outpace traditional forestry.[56]Non-Wood and Alternative Fibers

Non-wood fibers, derived from herbaceous plants rather than trees, constitute an alternative raw material for pulp production, comprising agricultural residues, bast fibers, and grasses. These include wheat and rice straw, sugarcane bagasse, bamboo, kenaf, and esparto grass, which are processed via chemical or mechanical methods to yield pulp suitable for paper, tissue, and specialty products. Globally, non-wood pulp production reached approximately 35 million metric tons in 2023, representing about 18% of total pulp output amid a market valued at USD 11.5 billion.[57] [58] [59] Agricultural residues such as wheat straw and rice straw are abundant byproducts of grain harvesting, particularly in Asia, where they supply pulp for cultural and printing papers. Wheat straw pulp, after bleaching, exhibits good strength properties and printability but requires depithing to remove non-fibrous pith, which generates fines that impair paper quality and bleachability. Rice straw, similarly processed with soda or anthraquinone additives, yields bleached pulp for writing papers, though its high silica content—up to 10-15%—accelerates equipment wear and demands additional washing steps. Sugarcane bagasse, the fibrous residue from juice extraction, provides a cellulose-rich source (around 40-50% content) used in board and filter papers, with global availability tied to sugarcane output exceeding 1.9 billion tons annually; pulping involves alkali cooking to achieve yields of 45-50%.[60] [61] [62] Bamboo, a fast-growing grass, supports chemical pulping for high-brightness products like tissue, with China's capacity at 2.4 million tons as of 2017, primarily via kraft processes yielding 80% for domestic tissue production. India and other Asian nations utilize bamboo for similar applications, leveraging its 50-60% cellulose content, though fiber length variability affects uniformity. Other non-wood sources, such as kenaf bast fibers, offer tensile strength advantages in specialty papers but face scalability issues due to cultivation costs.[63] [64] These fibers provide benefits including rapid renewability—bamboo matures in 3-5 years versus decades for trees—and utilization of waste streams, potentially reducing landfill disposal and farming costs. In mechanical pulping, non-wood materials require less energy than wood, and their adoption mitigates deforestation pressures in fiber-short regions. However, disadvantages include seasonal supply fluctuations, necessitating storage infrastructure, and processing challenges: high ash and silica levels increase chemical demands and effluent loads in chemical pulping, while shorter fiber lengths (1-3 mm versus wood's 3-5 mm) result in lower tear strength papers requiring blends with wood pulp. Year-round availability remains a barrier for mill operations, often limiting non-wood use to 10-20% in hybrid pulps. Innovations like enzymatic pre-treatments for bagasse and straw aim to enhance yields and reduce environmental impacts, though empirical data on full lifecycle emissions shows mixed sustainability gains compared to managed forestry.[65] [66] [67]Pulping Processes

Mechanical Pulping Techniques

Mechanical pulping techniques separate wood fibers through physical grinding or refining without dissolving lignin, resulting in high yields of 92-96% but producing pulp with lower strength due to retained lignin content. These methods are energy-intensive, typically consuming 1,000-4,000 kWh per ton depending on the variant, and yield pulp suitable for opaque, bulky products like newsprint and tissue where high yield compensates for weaker fiber bonding.[68] The processes rely on mechanical attrition to break fiber bonds, preserving most of the wood mass but incorporating fines and shives that affect paper quality.[69] Stone groundwood (SGW) pulping, the earliest mechanical method developed in the 19th century, involves pressing debarked logs against a rotating grindstone under water to abrade fibers from the wood. This produces yields of 93-98% with energy consumption around 1,300 kWh/ton, though much of the energy dissipates as heat from viscoelastic wood deformation rather than efficient fiber separation.[68] SGW pulp contains high levels of fines and lignin, limiting its use to low-grade papers, and requires subsequent refining to improve fiber development. Refiner mechanical pulp (RMP) processes wood chips in disc refiners where rotating plates shear and compress the material at atmospheric pressure, generating heat that softens lignin in situ. Compared to SGW, RMP uses chips rather than logs, allowing better utilization of wood resources and producing pulp with slightly longer fibers but similar high energy demands.[70] Yields remain above 90%, though the process generates more shives necessitating screening.[68] Thermomechanical pulp (TMP) refines preconditioned chips in pressurized refiners with steam pretreatment at temperatures up to 150°C, enhancing fiber separation efficiency over RMP by reducing shives and increasing fiber length while requiring higher energy input of 2,000-4,000 kWh/ton.[70] This technique yields stronger pulp suitable for higher-quality printing papers, as the thermal softening minimizes fiber damage and improves bonding potential despite retained lignin.[71] TMP's advantages include lower fines content and better opacity in end products, though it demands precise control of steam pressure to optimize energy use and pulp properties.[72]Chemical Pulping Methods

Chemical pulping methods employ chemical agents to selectively dissolve lignin from lignocellulosic raw materials, primarily wood chips, thereby liberating cellulose fibers while minimizing damage to the fibrous structure. This contrasts with mechanical pulping by achieving higher pulp quality suitable for strong, durable paper products, though at the cost of lower yields typically ranging from 40% to 55% of the original dry wood weight. The process involves cooking the chips in a liquor under elevated temperature and pressure, followed by washing to separate the pulp from spent chemicals.[73][74] The kraft, or sulfate, process dominates chemical pulping, accounting for over 90% of global chemical pulp production due to its versatility with various wood species and efficient chemical recovery. Wood chips are treated with white liquor—a mixture of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium sulfide (Na2S)—at temperatures of 160–180°C and pressures up to 10 bar for 2–5 hours, which breaks down lignin into soluble fragments while preserving fiber strength. Pulp yield in kraft pulping averages 45–50% for softwoods and slightly higher for hardwoods, with the process enabling recovery of up to 95% of cooking chemicals through black liquor evaporation and combustion in a recovery boiler, which also generates energy. This recovery mitigates costs and environmental impacts, though the process emits odorous sulfur compounds like hydrogen sulfide if not controlled.[75][17][74] Sulfite pulping, an older method developed in the late 19th century, uses sulfurous acid (H2SO3) or bisulfite salts (e.g., calcium, magnesium, sodium, or ammonium bisulfite) in acidic, neutral, or alkaline variants to delignify wood, producing brighter pulps ideal for writing papers and tissues. Cooking occurs at 130–180°C for 4–12 hours, yielding 40–50% pulp, but it is limited to softwoods and certain hardwoods due to less effective lignin removal from resinous species. Advantages include superior brightness and ease of bleaching, but disadvantages encompass higher production costs, poorer strength compared to kraft pulp, and challenges in chemical recovery, particularly with calcium-based variants that generate insoluble waste. Environmental concerns, such as acidic effluents and sulfur dioxide emissions, have reduced its prevalence to under 10% of chemical pulping.[76][77] Soda pulping, a sulfur-free alkaline process using solely sodium hydroxide, was historically applied to non-woody fibers like bagasse or bamboo but sees limited modern use for wood due to lower pulp strength and tear resistance. It operates at similar conditions to kraft (160–170°C, 3–5 hours) with yields around 45–50%, and additions of anthraquinone (AQ) as a catalyst can enhance delignification rates and yield by accelerating peeling reactions while stabilizing carbohydrates. Compared to kraft, soda pulping avoids sulfur emissions but requires more alkali and produces weaker fibers, making it uneconomical for most wood pulps without additives.[78][79] Overall, chemical pulping's environmental footprint includes significant water use (20–50 m³ per ton of pulp), energy demands (up to 20 GJ/ton), and greenhouse gas emissions averaging 600–2000 kg CO2 equivalent per metric ton, largely from black liquor combustion and process heat. Kraft's recovery systems reduce net impacts relative to sulfite, but both face scrutiny for aquatic toxicity from effluents unless treated via extended aeration or anaerobic digestion.[80][81]Hybrid and Specialized Pulping

Hybrid pulping processes integrate chemical pretreatment with mechanical defibration to achieve a balance between pulp yield, strength, and energy efficiency, yielding pulps with properties intermediate between those of purely mechanical and chemical methods.[82] Chemi-thermomechanical pulping (CTMP), a prominent hybrid technique, begins with impregnation of wood chips using sulfite or sodium hydroxide solutions, followed by preheating to 90–150°C to soften lignin, and subsequent mechanical refining under pressure of about 3 bar.[83] This process typically consumes 2–4% chemicals by weight and results in pulps with yields of 80–95%, offering improved fiber flexibility and bonding over thermomechanical pulping while retaining more lignin for opacity and bulk.[84] CTMP pulps, often from softwoods like spruce, are valued for applications in newsprint, tissue, and board, with energy inputs around 800 kWh per air-dried metric ton in optimized low-consistency refining variants.[85] Semi-chemical pulping, another hybrid approach, involves partial chemical digestion—using sodium hydroxide or bisulfite at lower severity than full chemical pulping—followed by mechanical refining to separate fibers.[86] This method yields pulps at 75–85% efficiency, suitable for corrugating medium and linerboard, as the retained lignin provides stiffness while chemical treatment reduces shives and enhances drainability.[87] Hybrid processes like CTMP and semi-chemical account for a notable share of mechanical pulp production, addressing limitations of pure mechanical methods such as high energy use and poor strength by selectively modifying lignin without extensive delignification.[88] Specialized pulping encompasses tailored methods for non-wood fibers or niche requirements, often emphasizing sustainability or lignin valorization. Organosolv pulping employs organic solvents like ethanol or acetone, sometimes with acid catalysts, at 160–200°C to fractionate biomass into cellulose, hemicellulose sugars, and high-purity lignin.[89] Advantages include facile solvent recovery via distillation and lower environmental toxicity compared to kraft processes, enabling lignin extraction for chemicals or fuels; however, high solvent costs and energy demands for recovery limit commercial scalability, with pilots showing pulp yields of 40–60% but requiring economic incentives for adoption.[90][91] Steam explosion pulping, suited for agricultural residues like wheat straw or oil palm empty fruit bunches, involves short-term steaming at 180–210°C under 10–30 bar followed by explosive decompression to disrupt fiber bonds.[92] This physicochemical method achieves ultra-high yields of 70–90%, preserving hemicelluloses for strength while facilitating lignin fragmentation, and produces pulps with tensile indices up to 8.6 N·m/g for non-wood sources after minimal refining.[93] It reduces chemical use versus traditional pulping for non-woods, though challenges include equipment corrosion from acetic acid release and variability in fiber quality from silica content.[65] These specialized techniques support biorefinery integration, prioritizing fiber separation with co-product recovery over mass yield alone.[94]Recycled Pulp Recovery

Recycled pulp recovery entails the mechanical and chemical processing of waste paper to liberate and purify cellulose fibers for reuse in papermaking, distinct from virgin pulping by relying on secondary raw materials rather than wood chips. The process begins with the collection of recovered paper, which globally reached approximately 59.1 million tonnes of recycled pulp production in 2022, supporting a circular fiber economy while substituting for virgin sources.[95] In the United States, 46 million tons of paper were recycled in 2024, achieving a recovery rate of 60-64%.[96] Yield efficiency in recovery typically incurs losses of 10-20% per cycle due to fines generation and contaminant rejection, with sludges representing the largest yield deduction in facilities processing mixed grades.[97] The initial pulping stage involves shredding sorted waste paper in a hydropulper—a large vat filled with water and dispersants—to form a low-consistency slurry (3-5% solids) where fibers separate via agitation and shear forces, typically at 40-60°C for 10-30 minutes.[98] Coarse contaminants like staples or plastics are removed via screening with perforated plates (slots 1-6 mm), followed by high-density cleaning using centrifugal forces to eject heavier rejects such as metals or stones.[99] This cleaning step achieves removal efficiencies exceeding 95% for macro-impurities, preserving fiber integrity while minimizing breakage.[100] De-inking, critical for producing brighter pulp from printed stock, employs flotation or washing methods to detach and eliminate ink particles. In flotation de-inking, surfactants and air injection generate microbubbles (0.1-1 mm) that adhere to hydrophobic ink via collector chemicals, rising to form foam skimmed from the surface; this yields effective residual ink concentrations below 100 ppm for office grades.[101] Washing complements by diluting the slurry to 0.5-1% consistency and using detergents to solubilize fine ink, though it consumes more water (up to 20,000 liters per ton) compared to flotation's 5,000-10,000 liters.[102] Hybrid systems combining both enhance overall de-inking efficiency to 90-98% for flexographic inks, but efficacy diminishes with modern UV-cured or water-based inks due to poorer detachability.[101] Post-de-inking refinement involves dispersion kneading to break ink aggregates and fine screening (0.1-0.3 mm slots) for micro-contaminant removal, followed by centrifugal or pressure screening to achieve pulp consistencies of 10-15%.[98] Fiber quality degrades with recycling, as repeated mechanical action shortens lengths by 10-20% per cycle and reduces tensile strength by accumulating fines, limiting practical reuse to about five cycles before blending with virgin fiber becomes necessary for high-grade applications.[103] Contamination from adhesives or coatings poses persistent challenges, often requiring enzymatic aids or advanced flotation to maintain pulp brightness above 70% ISO, though recycled pulp inherently yields lower opacity and burst strength than chemical virgin pulp.[104] Despite these limitations, recovery processes recover 80-90% of input fiber mass as usable pulp, enabling cost savings of 40-60% in energy versus virgin pulping while reducing landfill diversion.[105]Post-Pulping Operations

Bleaching and Brightening

Bleaching of wood pulp involves a multi-stage chemical treatment to remove residual lignin and chromophores, thereby increasing the pulp's brightness, whiteness, and suitability for high-quality paper production. The process typically employs oxidizing agents in sequences of up to five stages, including delignification, extraction, and final brightening steps, to achieve brightness levels of 80-95% ISO for chemical pulps.[106][107] This enhances the pulp's ability to accept dyes, inks, and coatings while reducing yellowness caused by lignin degradation products.[108] Dominant modern bleaching technologies include elemental chlorine-free (ECF) and totally chlorine-free (TCF) methods. ECF utilizes chlorine dioxide (ClO2) as the primary bleaching agent, replacing elemental chlorine gas since the 1990s to minimize dioxin formation and effluent toxicity, and accounts for over 90% of global chemical pulp bleaching capacity as of 2023.[109][110] TCF, by contrast, relies on oxygen, hydrogen peroxide, and ozone without any chlorine compounds, offering lower AOX (adsorbable organic halides) emissions but requiring 10-20% more energy and wood fiber to attain equivalent brightness and strength due to less efficient delignification.[111][109] Life-cycle assessments indicate comparable environmental impacts between ECF and TCF in categories like global warming and eutrophication, with ECF often showing advantages in resource efficiency.[112] Brightening complements chemical bleaching by incorporating optical brightening agents (OBAs), also known as fluorescent whitening agents, which are stilbene-based or similar organic compounds added during pulp refining or papermaking. These agents absorb ultraviolet light (below 400 nm) and re-emit it as visible blue light (around 450 nm), counteracting yellow tones for a perceived whiteness increase of 5-10 ISO points without altering inherent pulp color.[113][114] OBAs are substantive to cellulose fibers under alkaline conditions and are used at dosages of 0.1-1% based on pulp dry weight, particularly in fine papers and tissues to meet consumer preferences for vivid whiteness.[115] However, their efficacy diminishes in high-yield mechanical pulps due to lignin interference, and overuse can lead to uneven fluorescence or reduced recyclability.[113][116]Refining, Washing, and Additives

Refining of pulp fibers entails mechanical shearing and compression in specialized equipment, such as double-disc or conical refiners, to fibrillate the fiber surfaces, increase bonding potential, and enhance papermaking properties like tensile strength and density. This process typically occurs at low consistency (2-5% solids) for chemical pulps, where fibers are subjected to repeated impacts between grooved plates, promoting internal delamination and external fibrillation without significant length reduction.[117][118] Refining energy input, measured in kWh per tonne, correlates directly with fiber development; for instance, 1-3% freeness reduction per stage is common in multi-stage refining for newsprint-grade pulp.[119] Excessive refining can lead to over-beating, reducing drainage rates and increasing energy costs, which averaged 200-500 kWh/tonne for softwood kraft pulp in industrial operations as of 2020.[120] Washing follows pulping, particularly in chemical processes like kraft, to displace and remove cooking liquors—such as black liquor containing dissolved lignin, hemicelluloses, and inorganic salts (e.g., sodium hydroxide and sulfide)—thereby recovering chemicals for reuse and purifying the pulp for downstream steps. Displacement washing employs countercurrent flow in equipment like vacuum drum washers or horizontal belt filters, achieving liquor removal efficiencies of 95-99% with diluted black liquor solids below 0.5% in washed pulp.[121][122] Key metrics include the washing factor (ratio of incoming to outgoing liquor solids) and residual alkali content, which, if not minimized (target <0.1 g/L NaOH), can impair bleaching efficacy and increase chemical demand. In modern mills, multistage washing with filtrate recycle reduces freshwater use to 10-20 m³/tonne of pulp while complying with effluent standards limiting total dissolved solids to under 1 g/L.[123] Additives are selectively incorporated post-washing and refining to stabilize pulp quality, mitigate biological degradation, or tailor properties for specific grades, though their use remains limited compared to papermaking wet-end chemistry. Chelating agents like EDTA (0.1-0.5% on pulp) are added to bind transition metals (e.g., Mn, Fe) that catalyze bleaching degradation, improving brightness stability in ECF (elemental chlorine-free) sequences.[25] Biocides, such as isothiazolinones at 10-50 ppm, prevent microbial slime formation during pulp storage or transport, critical for market pulp where contamination can exceed 10^5 CFU/g, leading to quality defects.[124] For enhanced pulping yield in extended processes, anthraquinone (0.01-0.05% on wood) may be retained from cooking and influence post-pulping fiber reactivity, though primary addition occurs earlier; its catalytic effect persists, accelerating delignification residuals removal.[125] These interventions prioritize process efficiency over bulk property alteration, with overuse risking regulatory scrutiny under effluent limits for persistent organics.[126]Pulp Properties and Types

Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Paper pulp consists of lignocellulosic fibers primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, with cellulose forming the structural backbone as a linear polysaccharide of glucose units.[127] Typical chemical composition in wood-derived pulp includes 40-45% cellulose, 23-35% hemicellulose, and 20-30% lignin prior to processing, though extractives and minor components like resins vary by species.[34] In chemical pulping processes, lignin content is substantially reduced to 1-5% through delignification, enhancing fiber purity and resulting in pulps with higher alpha-cellulose content exceeding 80% after bleaching.[77] Mechanical pulps retain nearly all original lignin (25-30%), yielding a more heterogeneous composition that includes fines and shives, which impact drainage and bonding properties.[128] Physically, pulp fibers exhibit species-dependent morphology, with softwood fibers averaging 3-5 mm in length and 30-40 μm in width, providing greater tensile strength due to thicker cell walls and higher aspect ratios compared to hardwood fibers at 1-1.5 mm length and 15-25 μm width.[34] Fiber coarseness, measured as mass per unit length (typically 0.1-0.3 mg/100m for softwoods), correlates with wood density, which ranges from 300-500 kg/m³ and influences pulp yield and sheet density.[129] Mechanical pulps feature shorter, more flexible fibers with increased fibrillation from grinding, leading to higher bulk and opacity but reduced tear strength, whereas chemical pulps preserve longer, more rigid fibers suited for high-strength applications.[130] Other key physical metrics include pulp freeness (Canadian Standard Freeness, CSF, often 100-700 mL for mechanical pulps indicating drainage rate) and viscosity (intrinsic viscosity 300-500 mL/g for kraft pulps, reflecting degree of polymerization).[131] Brightness, a measure of whiteness post-bleaching, reaches 80-90% ISO for chemical pulps versus 50-70% for mechanical due to residual chromophores in lignin.[77] These properties directly determine end-use suitability, with chemical pulps favoring printing grades and mechanical pulps newsprint, underscoring causal links between processing intensity and fiber integrity.[132]Classification by Process and Grade

Paper pulp is classified by pulping process into mechanical, chemical, semichemical, and recovered categories, each yielding distinct fiber properties that influence paper strength, opacity, and permanence. Mechanical pulps, produced by grinding or refining wood without lignin removal, achieve yields of 85-95% and furnish high-bulk, opaque sheets for newsprint and directories but degrade rapidly due to retained hemicelluloses and lignin.[133] Chemical pulps, primarily from kraft (sulfate) or sulfite processes, dissolve 40-55% of wood mass to isolate cellulose fibers, enabling stronger, more durable papers for packaging and printing; kraft dominates with 85-90% of chemical production for its versatility and recovery of cooking chemicals.[133] Semichemical pulps combine mild chemical pretreatment with mechanical action for yields of 75-85%, suiting corrugated medium and linerboard.[133] Recovered pulps from deinking wastepaper provide lower-cost fibers but with variable contaminants, often blended for tissue or board.[134] Grading further differentiates pulps by fiber source, bleaching, and performance metrics like brightness, viscosity, and purity, aligning with end-use demands. Softwood pulps (e.g., northern bleached softwood kraft, NBSK) from conifers like spruce and pine offer long fibers (3-4 mm) for tensile strength in sack papers, while hardwood pulps (e.g., bleached eucalyptus kraft, BEK) from deciduous species yield shorter fibers (1-1.5 mm) for smoothness in writing papers.[134] Bleached grades, treated via elemental chlorine-free (ECF) or total chlorine-free (TCF) sequences, reach ISO brightness of 88-92% for graphic arts, contrasting unbleached pulps at 40-60% brightness for economical brown packaging.[134] Dissolving pulps, refined to >93% alpha-cellulose and viscosities of 400-600 mL/g, support non-paper applications like viscose rayon, distinct from papergrade pulps at higher hemicellulose content.[135] Fluff pulps, chemically or chemi-mechanically processed for absorbency, grade by bulk and fluid retention for hygiene products.[134] Standard metrics underpin grading: ISO 2470 specifies brightness via diffuse blue reflectance, while TAPPI T230 measures capillary viscosity to assess cellulose degradation, with values >500 mL/g indicating intact chains for strength.[136] Trade grades like NBSK command premiums (e.g., $800-1000/tonne in 2023) over mechanical types ($400-600/tonne) due to superior purity and yield efficiency in downstream forming.[134] Hybrid classifications, such as bleached chemi-thermomechanical pulp (BCTMP), blend process traits for opacity in coated papers, with brightness targets of 80-85% ISO.[134]Applications

Paper and Paperboard Manufacturing

Paper and paperboard manufacturing converts pulp into continuous sheets via sequential dewatering and consolidation on paper machines, with paper typically featuring grammage below 250 g/m² and paperboard exceeding this threshold for greater thickness and rigidity.[137] [138] The process commences with stock preparation, diluting refined pulp to under 1% fiber consistency in water, followed by cleaning via screens and cyclones to remove contaminants before feeding into the machine headbox.[133] [1] In the forming section, predominantly using Fourdrinier machines, the slurry jets onto a high-speed moving wire mesh (1,200–5,000 feet per minute), where gravity, foils, and vacuum boxes drain free water, forming an embryonic fiber web with initial solids content around 15-20%.[1] [133] The wet web transfers to felts in the press section, where multiple nips between rollers squeeze out additional water, elevating consistency to 40-50%.[1] [133] Drying follows on steam-heated cast-iron cylinders maintained at approximately 200°F (93°C), evaporating moisture to 4-5% final content while the web consolidates via hydrogen bonding between fibers.[1] [133] Finishing entails calendering, passing the sheet through stacked rolls under pressure to enhance smoothness, density, and printability, with optional coating for specialized grades.[1] Paperboard production diverges by often employing multi-wire formers or cylinder-vat machines to build multi-ply structures—typically at least three layers—with long softwood fibers in outer plies for surface quality and bulkier fibers internally for strength, minimizing fillers to preserve rigidity unlike filler-heavy printing papers.[138] [137] These variations yield products suited for packaging, where grammage ranges 200–1,000 g/m², contrasting single-ply paper machines optimized for lower basis weights (70–200 g/m²) and finer finishes.[138] [1] The resulting reels are slit and converted into end-use formats, with process controls ensuring uniformity in properties like tensile strength and opacity derived from pulp characteristics.[133]

Specialty and Non-Paper Uses

Dissolving pulp, a high-purity form of chemical pulp containing over 90% cellulose, serves as the primary raw material for regenerated cellulose fibers in the textile industry.[139] It is processed through methods like viscose or lyocell production to create fibers such as viscose rayon, which accounted for over 70% of dissolving pulp consumption in 2023, primarily in apparel, home textiles, and nonwovens.[140] Lyocell, produced via a more environmentally benign solvent-spinning process, is used in clothing and medical textiles for its softness and breathability.[141] Other applications include acetate fibers for cigarette filters and photographic films, as well as cellophane for packaging.[135] Fluff pulp, derived from southern softwood or hardwood via fluffing processes, is specialized for highly absorbent nonwoven structures rather than sheet formation. It forms the core of disposable hygiene products like diapers and sanitary napkins, where its high bulk and liquid retention capacity—up to 10 times its weight—are critical.[142] In medical applications, fluff pulp enables wound dressings and surgical pads that prioritize absorbency over structural rigidity.[143] Cellulose pulp finds use in filtration media, particularly alpha cellulose fibers from wood pulp, which create porous structures for capturing particulates in industrial and pharmaceutical processes.[144] These filters are employed in air and liquid purification, including beverage clarification and sterile pharmaceutical production, due to their cost-effectiveness and compatibility with chemical treatments.[145] In composite materials, wood pulp fibers act as reinforcements in polymer matrices, such as epoxy resins, enhancing stiffness and strength at low cost. Studies demonstrate that incorporating extracted cellulose fibers from pulp increases tensile modulus in composites by up to 20-30% compared to unfilled polymers, suitable for automotive and construction applications.[146] Pulp-based fillers also appear in bioplastics and starch composites, where fiber contents of 60-70% by weight improve mechanical properties without synthetic additives.[147]Economics and Markets

Global Production Volumes

Global wood pulp production reached approximately 195 million metric tons in 2023, reflecting steady long-term growth from about 60 million metric tons in 1961 despite periodic fluctuations tied to economic cycles and raw material availability.[59][39] Production volumes have expanded due to rising demand for paper products, packaging, and tissue, though recent years show moderation; for instance, FAO data indicate a 2% decline to 193 million tonnes in the latest reported period, attributed to slower global economic activity and supply chain disruptions.[43][148] Chemical pulp constitutes the majority of output, accounting for 158 million metric tons in 2023, or roughly 81% of total production, produced via processes like kraft or sulfite that yield higher-quality fibers suitable for printing and writing papers.[59] Mechanical and semi-chemical pulps, which preserve more wood yield but result in lower-strength fibers, totaled about 25 million metric tons, primarily used for newsprint and lower-grade papers.[59] Recovered or recycled pulp supplements virgin production but is not typically included in primary wood pulp volume statistics.[95]| Pulp Type | Production (million metric tons, 2023) | Share of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical | 158 | 81% |

| Mechanical/Semi-chemical | 25 | 13% |

| Other/Non-wood | ~12 | 6% |

Trade, Pricing, and Supply Chains

Global trade in wood pulp reached approximately 70 million metric tons in 2023, with bleached eucalyptus kraft pulp from Brazil accounting for over 25% of exports due to the country's competitive production costs from eucalyptus plantations.[39] Major exporters include Brazil, Canada, the United States, and Indonesia, while key importers are China, India, South Korea, and Egypt, driven by demand for paper production and textiles in Asia.[152] In 2024, dissolving grade wood pulp imports totaled 7.7 million tons worldwide, reflecting growth in specialty applications like viscose fibers.[153] Pricing for wood pulp is influenced by raw material costs, energy prices, global supply capacity expansions, and demand from packaging and hygiene products, with bleached softwood kraft (BSK) and northern bleached softwood kraft (NBSK) serving as benchmark grades. The average import price stood at $728 per ton in 2024, up 2.1% from the prior year, but spot prices declined amid oversupply, with NBSK in China falling to around $791 per metric ton in Q1 2025 before stabilizing.[154] [155] As of October 24, 2025, kraft pulp traded at 4,852 CNY per ton, down 3.31% over the preceding month, reflecting downward pressure from Latin American mill expansions outpacing demand recovery.[156] Contracts often blend fixed and market-based elements, but volatility persists due to freight costs and currency fluctuations, with U.S. producer prices for wood pulp at 225.46 in recent data, down from 239.28 a year earlier.[157]| Top Wood Pulp Exporters (2023, million metric tons) | Volume |

|---|---|

| Brazil | ~17.5 |

| Canada | ~10 |

| United States | ~8 |

| Indonesia | ~5 |