Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

JavaScript

View on Wikipedia

| JavaScript | |

|---|---|

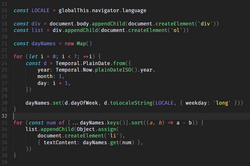

Screenshot of JavaScript source code | |

| Paradigms | Multi-paradigm: event-driven, functional, imperative, procedural, object-oriented |

| Family | ECMAScript |

| Designed by | Brendan Eich of Netscape first; then others contributed to ECMAScript standard |

| First appeared | 4 December 1995[1] |

| Stable release | ECMAScript 2024[2] |

| Preview release | ECMAScript 2025[3] |

| Typing discipline | Dynamic, weak, duck |

| Memory management | Garbage collected |

| Scope | lexical |

| Filename extensions | .js • .mjs • .cjs[4] |

| Website | ecma-international |

| Major implementations | |

| V8, JavaScriptCore, SpiderMonkey; Chakra (deprecated) | |

| Influenced by | |

| Java,[5][6] Scheme,[6] Self,[7] AWK,[8] HyperTalk[9] | |

| Influenced | |

| ActionScript, ArkTS, AssemblyScript, CoffeeScript, Dart, Haxe, JS++, Opa, TypeScript | |

| |

JavaScript (JS)[a] is a programming language and core technology of the Web, alongside HTML and CSS. It was created by Brendan Eich in 1995.[6] Ninety-nine percent of websites use JavaScript on the client side for webpage behavior.[10]

Web browsers have a dedicated JavaScript engine that executes the client code. These engines are also utilized in some servers and a variety of apps. The most popular runtime system for non-browser usage is Node.js.[11]

JavaScript is a high-level, often just-in-time–compiled language that conforms to the ECMAScript standard.[12] It has dynamic typing, prototype-based object-orientation, and first-class functions. It is multi-paradigm, supporting event-driven, functional, and imperative programming styles. It has application programming interfaces (APIs) for working with text, dates, regular expressions, standard data structures, and the Document Object Model (DOM).

The ECMAScript standard does not include any input/output (I/O), such as networking, storage, or graphics facilities. In practice, the web browser or other runtime system provides JavaScript APIs for I/O.

Although Java and JavaScript are similar in name and syntax, the two languages are distinct and differ greatly in design.

History

[edit]Creation at Netscape

[edit]The first popular web browser with a graphical user interface, Mosaic, was released in 1993. The lead developers of Mosaic then founded the Netscape corporation, which released a more polished browser, Netscape Navigator, in 1994. This quickly became the most-used.[13]

During these formative years of the Web, web pages could only be static, lacking the capability for dynamic behavior after the page was loaded in the browser. There was a desire in the flourishing web development scene to remove this limitation, so in 1995, Netscape decided to add a programming language to Navigator. They pursued two routes to achieve this: collaborating with Sun Microsystems to embed the Java language, while also hiring Brendan Eich to embed the Scheme language.[6]

The goal was a "language for the masses",[14] "to help nonprogrammers create dynamic, interactive Web sites".[15] Netscape management soon decided that the best option was for Eich to devise a new language, with syntax similar to Java and less like Scheme or other extant scripting languages.[5][6] Although the new language and its interpreter implementation were called LiveScript when first shipped as part of a Navigator beta in September 1995, the name was changed to JavaScript for the official release in December.[6][1][16][17]

The choice of the JavaScript name has caused confusion, implying that it is directly related to Java. At the time, the dot-com boom had begun and Java was a popular new language, so Eich considered the JavaScript name a marketing ploy by Netscape.[14]

Adoption by Microsoft

[edit]Microsoft debuted Internet Explorer in 1995, leading to a browser war with Netscape. On the JavaScript front, Microsoft created its own interpreter called JScript.[18]

Microsoft first released JScript in 1996, alongside initial support for CSS and extensions to HTML. Each of these implementations was noticeably different from their counterparts in Netscape Navigator.[19][20] These differences made it difficult for developers to make their websites work well in both browsers, leading to widespread use of "best viewed in Netscape" and "best viewed in Internet Explorer" logos for several years.[19][21]

The rise of JScript

[edit]Brendan Eich later said of this period: "It's still kind of a sidekick language. It's considered slow or annoying. People do pop-ups or those scrolling messages in the old status bar at the bottom of your old browser."[14]

In November 1996, Netscape submitted JavaScript to Ecma International, as the starting point for a standard specification that all browser vendors could conform to. This led to the official release of the first ECMAScript language specification in June 1997.

The standards process continued for a few years, with the release of ECMAScript 2 in June 1998 and ECMAScript 3 in December 1999. Work on ECMAScript 4 began in 2000.[18]

However, the effort to fully standardize the language was undermined by Microsoft gaining an increasingly dominant position in the browser market. By the early 2000s, Internet Explorer's market share reached 95%.[22] This meant that JScript became the de facto standard for client-side scripting on the Web.

Microsoft initially participated in the standards process and implemented some proposals in its JScript language, but eventually it stopped collaborating on ECMA work. Thus ECMAScript 4 was mothballed.

Growth and standardization

[edit]

During the period of Internet Explorer dominance in the early 2000s, client-side scripting was stagnant. This started to change in 2004, when the successor of Netscape, Mozilla, released the Firefox browser. Firefox was well received by many, taking significant market share from Internet Explorer.[23]

In 2005, Mozilla joined ECMA International, and work started on the ECMAScript for XML (E4X) standard. This led to Mozilla working jointly with Macromedia (later acquired by Adobe Systems), who were implementing E4X in their ActionScript 3 language, which was based on an ECMAScript 4 draft. The goal became standardizing ActionScript 3 as the new ECMAScript 4. To this end, Adobe Systems released the Tamarin implementation as an open source project. However, Tamarin and ActionScript 3 were too different from established client-side scripting, and without cooperation from Microsoft, ECMAScript 4 never reached fruition.

Meanwhile, very important developments were occurring in open-source communities not affiliated with ECMA work. In 2005, Jesse James Garrett released a white paper in which he coined the term Ajax and described a set of technologies, of which JavaScript was the backbone, to create web applications where data can be loaded in the background, avoiding the need for full page reloads. This sparked a renaissance period of JavaScript, spearheaded by open-source libraries and the communities that formed around them. Many new libraries were created, including jQuery, Prototype, Dojo Toolkit, and MooTools.

Google debuted its Chrome browser in 2008, with the V8 JavaScript engine that was faster than its competition.[24][25] The key innovation was just-in-time compilation (JIT),[26] so other browser vendors needed to overhaul their engines for JIT.[27]

In July 2008, these disparate parties came together for a conference in Oslo. This led to the eventual agreement in early 2009 to combine all relevant work and drive the language forward. The result was the ECMAScript 5 standard, released in December 2009.

Reaching maturity

[edit]Ambitious work on the language continued for several years, culminating in an extensive collection of additions and refinements being formalized with the publication of ECMAScript 6 in 2015.[28]

The creation of Node.js in 2009 by Ryan Dahl sparked a significant increase in the usage of JavaScript outside of web browsers. Node combines the V8 engine, an event loop, and I/O APIs, thereby providing a stand-alone JavaScript runtime system.[29][30] As of 2018, Node had been used by millions of developers,[31] and npm had the most modules of any package manager in the world.[32]

The ECMAScript draft specification is currently maintained openly on GitHub,[33] and editions are produced via regular annual snapshots.[33] Potential revisions to the language are vetted through a comprehensive proposal process.[34][35] Now, instead of edition numbers, developers check the status of upcoming features individually.[33]

The current JavaScript ecosystem has many libraries and frameworks, established programming practices, and substantial usage of JavaScript outside of web browsers.[17] Plus, with the rise of single-page applications and other JavaScript-heavy websites, several transpilers have been created to aid the development process.[36]

Trademark

[edit]"JavaScript" is a trademark of Oracle Corporation in the United States.[37][38] The trademark was originally issued to Sun Microsystems on 6 May 1997, and was transferred to Oracle when they acquired Sun in 2009.[39][40]

A letter was circulated in September 2024, spearheaded by Ryan Dahl, calling on Oracle to free the JavaScript trademark.[41] Brendan Eich, the original creator of JavaScript, was among the over 14,000 signatories who supported the initiative.

Website client-side usage

[edit]JavaScript is the dominant client-side scripting language of the Web, with 99% of all websites using it for this purpose.[10] Scripts are embedded in or included from HTML documents and interact with the DOM.

All major web browsers have a built-in JavaScript engine that executes the code on the user's device.

Examples of scripted behavior

[edit]- Loading new web page content without reloading the page, via Ajax or a WebSocket. For example, users of social media can send and receive messages without leaving the current page.

- Web page animations, such as fading objects in and out, resizing, and moving them.

- Playing browser games.

- Controlling the playback of streaming media.

- Generating pop-up ads or alert boxes.

- Validating input values of a web form before the data is sent to a web server.

- Logging data about the user's behavior then sending it to a server. The website owner can use this data for analytics, ad tracking, and personalization.

- Redirecting a user to another page.

- Storing and retrieving data on the user's device, via the storage or IndexedDB standards.

Libraries and frameworks

[edit]Over 80% of websites use a third-party JavaScript library or web framework as part of their client-side scripting.[42]

jQuery is by far the most-used.[42] Other notable ones include Angular, Bootstrap, Lodash, Modernizr, React, Underscore, and Vue.[42] Multiple options can be used in conjunction, such as jQuery and Bootstrap.[43]

However, the term "Vanilla JS" was coined for websites not using any libraries or frameworks at all, instead relying entirely on standard JavaScript functionality.[44]

Other usage

[edit]The use of JavaScript has expanded beyond its web browser roots. JavaScript engines are now embedded in a variety of other software systems, both for server-side website deployments and non-browser applications.

Initial attempts at promoting server-side JavaScript usage were Netscape Enterprise Server and Microsoft's Internet Information Services,[45][46] but they were small niches.[47] Server-side usage eventually started to grow in the late 2000s, with the creation of Node.js and other approaches.[47]

Electron, Cordova, React Native, and other application frameworks have been used to create many applications with behavior implemented in JavaScript. Other non-browser applications include Adobe Acrobat support for scripting PDF documents[48] and GNOME Shell extensions written in JavaScript.[49]

Oracle used to provide Nashorn, a JavaScript interpreter, as part of their Java Development Kit (JDK) API library along with jjs a command line interpreter as of JDK version 8. It was removed in JDK 15. As a replacement Oracle offered GraalJS which can also be used with the OpenJDK which allows one to create and reference Java objects in JavaScript code and add runtime scripting in JavaScript to applications written in Java.[50][51][52][53]

JavaScript has been used in some embedded systems, usually by leveraging Node.js.[54][55][56]

Execution

[edit]JavaScript engine

[edit]Runtime system

[edit]A JavaScript engine must be embedded within a runtime system (such as a web browser or a standalone system) to enable scripts to interact with the broader environment. The runtime system includes the necessary APIs for input/output operations, such as networking, storage, and graphics, and provides the ability to import scripts.

JavaScript is a single-threaded language. The runtime processes messages from a queue one at a time, and it calls a function associated with each new message, creating a call stack frame with the function's arguments and local variables. The call stack shrinks and grows based on the function's needs. When the call stack is empty upon function completion, JavaScript proceeds to the next message in the queue. This is called the event loop, described as "run to completion" because each message is fully processed before the next message is considered. However, the language's concurrency model describes the event loop as non-blocking: program I/O is performed using events and callback functions. This means, for example, that JavaScript can process a mouse click while waiting for a database query to return information.[61]

Features

[edit]The following features are common to all conforming ECMAScript implementations unless explicitly specified otherwise. The number of cited reserved words including keywords is 50–60 and varies depending on the implementation.

Imperative and structured

[edit]JavaScript supports much of the structured programming syntax from C (e.g., if statements, while loops, switch statements, do while loops, etc.). One partial exception is scoping: originally JavaScript only had function scoping with var; block scoping was added in ECMAScript 2015 with the keywords let and const. Like C, JavaScript makes a distinction between expressions and statements. One syntactic difference from C is automatic semicolon insertion, which allow semicolons (which terminate statements) to be omitted.[62]

Weakly typed

[edit]JavaScript is weakly typed, which means certain types are implicitly cast depending on the operation used.[63]

- The binary

+operator casts both operands to a string unless both operands are numbers. This is because the addition operator doubles as a concatenation operator - The binary

-operator always casts both operands to a number - Both unary operators (

+,-) always cast the operand to a number. However,+always casts toNumber(binary64) while-preservesBigInt(integer)[64]

Values are cast to strings like the following:[63]

- Strings are left as-is

- Numbers are converted to their string representation

- Arrays have their elements cast to strings after which they are joined by commas (

,) - Other objects are converted to the string

[object Object]whereObjectis the name of the constructor of the object

Values are cast to numbers by casting to strings and then casting the strings to numbers. These processes can be modified by defining toString and valueOf functions on the prototype for string and number casting respectively.

JavaScript has received criticism for the way it implements these conversions as the complexity of the rules can be mistaken for inconsistency.[65][63] For example, when adding a number to a string, the number will be cast to a string before performing concatenation, but when subtracting a number from a string, the string is cast to a number before performing subtraction.

| left operand | operator | right operand | result |

|---|---|---|---|

[] (empty array)

|

+

|

[] (empty array)

|

"" (empty string)

|

[] (empty array)

|

+

|

{} (empty object)

|

"[object Object]" (string)

|

false (boolean)

|

+

|

[] (empty array)

|

"false" (string)

|

"123"(string)

|

+

|

1 (number)

|

"1231" (string)

|

"123" (string)

|

-

|

1 (number)

|

122 (number)

|

"123" (string)

|

-

|

"abc" (string)

|

NaN (number)

|

Often also mentioned is {} + [] resulting in 0 (number). This is misleading: the {} is interpreted as an empty code block instead of an empty object, and the empty array is cast to a number by the remaining unary + operator. If the expression is wrapped in parentheses - ({} + []) – the curly brackets are interpreted as an empty object and the result of the expression is "[object Object]" as expected.[63]

Dynamic

[edit]Typing

[edit]JavaScript is dynamically typed like most other scripting languages. A type is associated with a value rather than an expression. For example, a variable initially bound to a number may be reassigned to a string.[66] JavaScript supports various ways to test the type of objects, including duck typing.[67]

Run-time evaluation

[edit]JavaScript includes an eval function that can execute statements provided as strings at run-time.

Object-orientation (prototype-based)

[edit]Prototypal inheritance in JavaScript is described by Douglas Crockford as:

You make prototype objects, and then ... make new instances. Objects are mutable in JavaScript, so we can augment the new instances, giving them new fields and methods. These can then act as prototypes for even newer objects. We don't need classes to make lots of similar objects... Objects inherit from objects. What could be more object oriented than that?[68]

In JavaScript, an object is an associative array, augmented with a prototype (see below); each key provides the name for an object property, and there are two syntactical ways to specify such a name: dot notation (obj.x = 10) and bracket notation (obj["x"] = 10). A property may be added, rebound, or deleted at run-time. Most properties of an object (and any property that belongs to an object's prototype inheritance chain) can be enumerated using a for...in loop.

Prototypes

[edit]JavaScript uses prototypes where many other object-oriented languages use classes for inheritance,[69] but it's still possible to simulate most class-based features with the prototype system.[70] Additionally, ECMAScript version 6 (released June 2015) introduced the keywords class, extends and super, which serve as syntactic sugar to abstract the underlying prototypal inheritance system with a more conventional interface. Constructors are declared by specifying a method named constructor, and all classes are automatically subclasses of the base class Object, similarly to Java.

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

class Student extends Person {

constructor(name, id) {

super(name);

this.id = id;

}

}

const bob = new Student("Robert", 12345);

console.log(bob.name); // Robert

Though the underlying object mechanism is still based on prototypes, the newer syntax is similar to other object oriented languages. Private variables are declared by prefixing the field name with a number sign (#), and polymorphism is not directly supported, although it can be emulated by manually calling different functions depending on the number and type of arguments provided.[71]

Functions as object constructors

[edit]

Functions double as object constructors, along with their typical role. Prefixing a function call with new will create an instance of a prototype, inheriting properties and methods from the constructor (including properties from the Object prototype).[72] ECMAScript 5 offers the Object.create method, allowing explicit creation of an instance without automatically inheriting from the Object prototype (older environments can assign the prototype to null).[73] The constructor's prototype property determines the object used for the new object's internal prototype. New methods can be added by modifying the prototype of the function used as a constructor.

// This code is completely equivalent to the previous snippet

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

function Student(name, id) {

Person.call(this, name);

this.id = id;

}

var bob = new Student("Robert", 12345);

console.log(bob.name); // Robert

JavaScript's built-in classes, such as Array and Object, also have prototypes that can be modified. However, it's generally considered bad practice to modify built-in objects, because third-party code may use or inherit methods and properties from these objects, and may not expect the prototype to be modified.[74]

Functions as methods

[edit]Unlike in many object-oriented languages, in JavaScript there is no distinction between a function definition and a method definition. Rather, the distinction occurs during function calling. When a function is called as a method of an object, the function's local this keyword is bound to that object for that invocation.

Functional

[edit]JavaScript functions are first-class; a function is considered to be an object.[75] As such, a function may have properties and methods, such as .call() and .bind().[76]

Lexical closure

[edit]A nested function is a function defined within another function. It is created each time the outer function is invoked.

In addition, each nested function forms a lexical closure: the lexical scope of the outer function (including any constant, local variable, or argument value) becomes part of the internal state of each inner function object, even after execution of the outer function concludes.[77]

Anonymous function

[edit]JavaScript also supports anonymous functions.

Delegative

[edit]JavaScript supports implicit and explicit delegation.

Functions as roles (Traits and Mixins)

[edit]JavaScript natively supports various function-based implementations of Role[78] patterns like Traits[79][80] and Mixins.[81] Such a function defines additional behavior by at least one method bound to the this keyword within its function body. A Role then has to be delegated explicitly via call or apply to objects that need to feature additional behavior that is not shared via the prototype chain.

Object composition and inheritance

[edit]Whereas explicit function-based delegation does cover composition in JavaScript, implicit delegation already happens every time the prototype chain is walked in order to, e.g., find a method that might be related to but is not directly owned by an object. Once the method is found it gets called within this object's context. Thus inheritance in JavaScript is covered by a delegation automatism that is bound to the prototype property of constructor functions.

Miscellaneous

[edit]Zero-based numbering

[edit]JavaScript is a zero-index language.

Variadic functions

[edit]An indefinite number of parameters can be passed to a function. The function can access them through formal parameters and also through the local arguments object. Variadic functions can also be created by using the bind method.

Array and object literals

[edit]Like in many scripting languages, arrays and objects (associative arrays in other languages) can each be created with a succinct shortcut syntax. In fact, these literals form the basis of the JSON data format.

Regular expressions

[edit]JavaScript supports regular expressions for text searches and manipulation.[72]: 139

Promises

[edit]A built-in Promise object provides functionality for handling promises and associating handlers with an asynchronous action's eventual result. JavaScript supplies combinator methods, which allow developers to combine multiple JavaScript promises and do operations based on different scenarios. The methods introduced are: Promise.race, Promise.all, Promise.allSettled and Promise.any.

Async/await

[edit]Async/await allows an asynchronous, non-blocking function to be structured in a way similar to an ordinary synchronous function. Asynchronous, non-blocking code can be written, with minimal overhead, structured similarly to traditional synchronous, blocking code.

Vendor-specific extensions

[edit]Historically, some JavaScript engines supported these non-standard features:

- array comprehensions and generator expressions (like Python)

- concise function expressions (

function(args) expr; this experimental syntax predated arrow functions) - ECMAScript for XML (E4X), an extension that adds native XML support to ECMAScript (unsupported in Firefox since version 21[82])

Syntax

[edit]Variables in JavaScript can be defined using either the var,[83] let[84] or const[85] keywords. Variables defined without keywords will be defined at the global scope.

Arrow functions were first introduced in 6th Edition – ECMAScript 2015. They shorten the syntax for writing functions in JavaScript. Arrow functions are anonymous, so a variable is needed to refer to them in order to invoke them after their creation, unless surrounded by parenthesis and executed immediately.

Here is an example of JavaScript syntax.

// Declares a function-scoped variable named `x`, and implicitly assigns the

// special value `undefined` to it. Variables without value are automatically

// set to undefined.

// var is generally considered bad practice and let and const are usually preferred.

var x;

// Variables can be manually set to `undefined` like so

let x2 = undefined;

// Declares a block-scoped variable named `y`, and implicitly sets it to

// `undefined`. The `let` keyword was introduced in ECMAScript 2015.

let y;

// Declares a block-scoped, un-reassignable variable named `z`, and sets it to

// a string literal. The `const` keyword was also introduced in ECMAScript 2015,

// and must be explicitly assigned to.

// The keyword `const` means constant, hence the variable cannot be reassigned

// as the value is `constant`.

const z = "this value cannot be reassigned!";

// Declares a global-scoped variable and assigns 3. This is generally considered

// bad practice, and will not work if strict mode is on.

t = 3;

// Declares a variable named `myNumber`, and assigns a number literal (the value

// `2`) to it.

let myNumber = 2;

// Reassigns `myNumber`, setting it to a string literal (the value `"foo"`).

// JavaScript is a dynamically-typed language, so this is legal.

myNumber = "foo";

Note the comments in the examples above, all of which were preceded with two forward slashes.

More examples can be found at the Wikibooks page on JavaScript syntax examples.

Security

[edit]JavaScript and the DOM provide the potential for malicious authors to deliver scripts to run on a client computer via the Web. Browser authors minimize this risk using two restrictions. First, scripts run in a sandbox in which they can only perform Web-related actions, not general-purpose programming tasks like creating files. Second, scripts are constrained by the same-origin policy: scripts from one website do not have access to information such as usernames, passwords, or cookies sent to another site. Most JavaScript-related security bugs are breaches of either the same origin policy or the sandbox.

There are subsets of general JavaScript—ADsafe, Secure ECMAScript (SES)—that provide greater levels of security, especially on code created by third parties (such as advertisements).[86][87] Closure Toolkit is another project for safe embedding and isolation of third-party JavaScript and HTML.[88]

Content Security Policy is the main intended method of ensuring that only trusted code is executed on a Web page.

Cross-site scripting

[edit]A common JavaScript-related security problem is cross-site scripting (XSS), a violation of the same-origin policy. XSS vulnerabilities occur when an attacker can cause a target Website, such as an online banking website, to include a malicious script in the webpage presented to a victim. The script in this example can then access the banking application with the privileges of the victim, potentially disclosing secret information or transferring money without the victim's authorization. One important solution to XSS vulnerabilities is HTML sanitization.

Some browsers include partial protection against reflected XSS attacks, in which the attacker provides a URL including malicious script. However, even users of those browsers are vulnerable to other XSS attacks, such as those where the malicious code is stored in a database. Only correct design of Web applications on the server-side can fully prevent XSS.

XSS vulnerabilities can also occur because of implementation mistakes by browser authors.[89]

Cross-site request forgery

[edit]Another cross-site vulnerability is cross-site request forgery (CSRF). In CSRF, code on an attacker's site tricks the victim's browser into taking actions the user did not intend at a target site (like transferring money at a bank). When target sites rely solely on cookies for request authentication, requests originating from code on the attacker's site can carry the same valid login credentials of the initiating user. In general, the solution to CSRF is to require an authentication value in a hidden form field, and not only in the cookies, to authenticate any request that might have lasting effects. Checking the HTTP Referrer header can also help.

"JavaScript hijacking" is a type of CSRF attack in which a <script> tag on an attacker's site exploits a page on the victim's site that returns private information such as JSON or JavaScript. Possible solutions include:

- requiring an authentication token in the POST and GET parameters for any response that returns private information.

Misplaced trust in the client

[edit]Developers of client-server applications must recognize that untrusted clients may be under the control of attackers. The author of an application should not assume that their JavaScript code will run as intended (or at all) because any secret embedded in the code could be extracted by a determined adversary. Some implications are:

- Website authors cannot perfectly conceal how their JavaScript operates because the raw source code must be sent to the client. The code can be obfuscated, but obfuscation can be reverse-engineered.

- JavaScript form validation only provides convenience for users, not security. If a site verifies that the user agreed to its terms of service, or filters invalid characters out of fields that should only contain numbers, it must do so on the server, not only the client.

- Scripts can be selectively disabled, so JavaScript cannot be relied on to prevent operations such as right-clicking on an image to save it.[90]

- It is considered very bad practice to embed sensitive information such as passwords in JavaScript because it can be extracted by an attacker.[91]

- Prototype pollution is a runtime vulnerability in which attackers can overwrite arbitrary properties in an object's prototype.

Misplaced trust in developers

[edit]Package management systems such as npm and Bower are popular with JavaScript developers. Such systems allow a developer to easily manage their program's dependencies upon other developers' program libraries. Developers trust that the maintainers of the libraries will keep them secure and up to date, but that is not always the case. A vulnerability has emerged because of this blind trust. Relied-upon libraries can have new releases that cause bugs or vulnerabilities to appear in all programs that rely upon the libraries. Inversely, a library can go unpatched with known vulnerabilities out in the wild. In a study done looking over a sample of 133,000 websites, researchers found 37% of the websites included a library with at least one known vulnerability.[92] "The median lag between the oldest library version used on each website and the newest available version of that library is 1,177 days in ALEXA, and development of some libraries still in active use ceased years ago."[92] Another possibility is that the maintainer of a library may remove the library entirely. This occurred in March 2016 when Azer Koçulu removed his repository from npm. This caused tens of thousands of programs and websites depending upon his libraries to break.[93][94]

Browser and plugin coding errors

[edit]JavaScript provides an interface to a wide range of browser capabilities, some of which may have flaws such as buffer overflows. These flaws can allow attackers to write scripts that would run any code they wish on the user's system. This code is not by any means limited to another JavaScript application. For example, a buffer overrun exploit can allow an attacker to gain access to the operating system's API with superuser privileges.

These flaws have affected major browsers including Firefox,[95] Internet Explorer,[96] and Safari.[97]

Plugins, such as video players, Adobe Flash, and the wide range of ActiveX controls enabled by default in Microsoft Internet Explorer, may also have flaws exploitable via JavaScript (such flaws have been exploited in the past).[98][99]

In Windows Vista, Microsoft has attempted to contain the risks of bugs such as buffer overflows by running the Internet Explorer process with limited privileges.[100] Google Chrome similarly confines its page renderers to their own "sandbox".

Sandbox implementation errors

[edit]Web browsers are capable of running JavaScript outside the sandbox, with the privileges necessary to, for example, create or delete files. Such privileges are not intended to be granted to code from the Web.

Incorrectly granting privileges to JavaScript from the Web has played a role in vulnerabilities in both Internet Explorer[101] and Firefox.[102] In Windows XP Service Pack 2, Microsoft demoted JScript's privileges in Internet Explorer.[103]

Microsoft Windows allows JavaScript source files on a computer's hard drive to be launched as general-purpose, non-sandboxed programs (see: Windows Script Host). This makes JavaScript (like VBScript) a theoretically viable vector for a Trojan horse, although JavaScript Trojan horses are uncommon in practice.[104][failed verification]

Hardware vulnerabilities

[edit]In 2015, a JavaScript-based proof-of-concept implementation of a rowhammer attack was described in a paper by security researchers.[105][106][107][108]

In 2017, a JavaScript-based attack via browser was demonstrated that could bypass ASLR. It is called "ASLR⊕Cache" or AnC.[109][110]

In 2018, the paper that announced the Spectre attacks against Speculative Execution in Intel and other processors included a JavaScript implementation.[111]

Development tools

[edit]Important tools have evolved with the language.

- Every major web browser has built-in web development tools, including a JavaScript debugger.

- Static program analysis tools, such as ESLint and JSLint, scan JavaScript code for conformance to a set of standards and guidelines.

- Some browsers have built-in profilers. Stand-alone profiling libraries have also been created, such as benchmark.js and jsbench.[112][113]

- Many text editors have syntax highlighting support for JavaScript code.

Related technologies

[edit]Java

[edit]A common misconception is that JavaScript is directly related to Java. Both indeed have a C-like syntax (the C language being their most immediate common ancestor language). They are also typically sandboxed, and JavaScript was designed with Java's syntax and standard library in mind. In particular, all Java keywords were reserved in original JavaScript, JavaScript's standard library follows Java's naming conventions, and JavaScript's Math and Date objects are based on classes from Java 1.0.[114]

Both languages first appeared in 1995, but Java was developed by James Gosling of Sun Microsystems and JavaScript by Brendan Eich of Netscape Communications.

The differences between the two languages are more prominent than their similarities. Java has static typing, while JavaScript's typing is dynamic. Java is loaded from compiled bytecode, while JavaScript is loaded as human-readable source code. Java's objects are class-based, while JavaScript's are prototype-based. Finally, Java did not support functional programming until Java 8, while JavaScript has done so from the beginning, being influenced by Scheme.

JSON

[edit]JSON is a data format derived from JavaScript; hence the name JavaScript Object Notation. It is a widely used format supported by many other programming languages.

Transpilers

[edit]Many websites are JavaScript-heavy, so transpilers have been created to convert code written in other languages, which can aid the development process.[36]

TypeScript and CoffeeScript are two notable languages that transpile to JavaScript.

WebAssembly

[edit]WebAssembly is a newer language with a bytecode format designed to complement JavaScript, especially the performance-critical portions of web page scripts. All of the major JavaScript engines support WebAssembly,[115] which runs in the same sandbox as regular JavaScript code.

asm.js is a subset of JavaScript that served as the forerunner of WebAssembly.[116]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Netscape and Sun announce JavaScript, the Open, Cross-platform Object Scripting Language for Enterprise Networks and the Internet" (Press release). 4 December 1995. Archived from the original on 16 September 2007.

- ^ "ECMAScript® 2024 Language Specification". June 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "ECMAScript® 2025 Language Specification". 27 March 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "nodejs/node-eps". GitHub. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ a b Seibel, Peter (16 September 2009). Coders at Work: Reflections on the Craft of Programming. Apress. ISBN 978-1-4302-1948-4. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

Eich: The immediate concern at Netscape was it must look like Java.

- ^ a b c d e f "Chapter 4. How JavaScript Was Created". speakingjs.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ "Popularity – Brendan Eich".

- ^ "Brendan Eich: An Introduction to JavaScript, JSConf 2010". YouTube. 20 January 2013. p. 22m. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

Eich: "function", eight letters, I was influenced by AWK.

- ^ Eich, Brendan (1998). "Foreword". In Goodman, Danny (ed.). JavaScript Bible (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-7645-3188-3. LCCN 97078208. OCLC 38888873. OL 712205M.

- ^ a b "Usage Statistics of JavaScript as Client-side Programming Language on Websites". W3Techs. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ "Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2025". Stack Overflow. Retrieved 10 October 2025.

- ^ "ECMAScript 2020 Language Specification". Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Enzer, Larry (31 August 2018). "The Evolution of the Web Browsers". Monmouth Web Developers. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Fin JS (17 June 2016), "Brendan Eich – CEO of Brave", YouTube, retrieved 7 February 2018

- ^ "Netscape Communications Corp.", Browser enhancements. Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD

- ^ "TechVision: Innovators of the Net: Brendan Eich and JavaScript". Archived from the original on 8 February 2008.

- ^ a b Han, Sheon (4 March 2024). "JavaScript Runs the World—Maybe Even Literally". Wired. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Chapter 5. Standardization: ECMAScript". speakingjs.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ a b Champeon, Steve (6 April 2001). "JavaScript, How Did We Get Here?". oreilly.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ "Microsoft Internet Explorer 3.0 Beta Now Available". microsoft.com. Microsoft. 29 May 1996. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ McCracken, Harry (16 September 2010). "The Unwelcome Return of "Best Viewed with Internet Explorer"". technologizer.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ Baker, Loren (24 November 2004). "Mozilla Firefox Internet Browser Market Share Gains to 7.4%". Search Engine Journal. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ Weber, Tim (9 May 2005). "The assault on software giant Microsoft". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017.

- ^ "Big browser comparison test: Internet Explorer vs. Firefox, Opera, Safari and Chrome". PC Games Hardware. Computec Media AG. 3 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Purdy, Kevin (11 June 2009). "Lifehacker Speed Tests: Safari 4, Chrome 2". Lifehacker. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "TraceMonkey: JavaScript Lightspeed, Brendan Eich's Blog". Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Mozilla asks, 'Are we fast yet?'". Wired. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "ECMAScript 6: New Features: Overview and Comparison". es6-features.org. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Professional Node.js: Building JavaScript Based Scalable Software Archived 2017-03-24 at the Wayback Machine, John Wiley & Sons, 01-Oct-2012

- ^ Sams Teach Yourself Node.js in 24 Hours Archived 2017-03-23 at the Wayback Machine, Sams Publishing, 05-Sep-2012

- ^ Lawton, George (19 July 2018). "The secret history behind the success of npm and Node". TheServerSide. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ Brown, Paul (13 January 2017). "State of the Union: npm". Linux.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Branscombe, Mary (4 May 2016). "JavaScript Standard Moves to Yearly Release Schedule; Here is What's New for ES16". The New Stack. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "The TC39 Process". tc39.es. Ecma International. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "ECMAScript proposals". TC39. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ a b Ashkenas, Jeremy. "List of languages that compile to JS". GitHub. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Trademark Serial No. 75026640". uspto.gov. United States Patent and Trademark Office. 6 May 1997. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "Legal Notices". oracle.com. Oracle Corporation. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "Oracle to buy Sun in $7.4-bn deal". The Economic Times. 21 April 2009.

- ^ Claburn, Thomas (17 September 2024). "Oracle urged again to give up JavaScript trademark". The Register. Retrieved 2 February 2025.

- ^ Krill, Paul (20 September 2024). "JavaScript community challenges Oracle's JavaScript trademark". InfoWorld.

- ^ a b c "Usage statistics of JavaScript libraries for websites". W3Techs. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Using jQuery with Bootstrap". clouddevs.com. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Vanilla JS". vanilla-js.com. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "Server-Side JavaScript Guide". oracle.com. Oracle Corporation. 11 December 1998. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ Clinick, Andrew (14 July 2000). "Introducing JScript .NET". Microsoft Developer Network. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

[S]ince the 1996 introduction of JScript version 1.0 ... we've been seeing a steady increase in the usage of JScript on the server—particularly in Active Server Pages (ASP)

- ^ a b Mahemoff, Michael (17 December 2009). "Server-Side JavaScript, Back with a Vengeance". readwrite.com. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ "JavaScript for Acrobat". adobe.com. 7 August 2009. Archived from the original on 7 August 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ treitter (2 February 2013). "Answering the question: "How do I develop an app for GNOME?"". livejournal.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ Ponge, Julien (19 April 2018). "Oracle Nashorn: A Next-Generation JavaScript Engine for the JVM". oracle.com. Oracle Corporation. Retrieved 17 February 2025.

- ^ "Migration Guide from Nashorn to GraalJS". graalvm.org. Retrieved 17 February 2025.

- ^ "GraalJS". GraalVM. Retrieved 17 February 2025.

- ^ "Java Interoperability". oracle.com. Oracle. Retrieved 17 February 2025.

- ^ "Tessel 2... Leverage all the libraries of Node.JS to create useful devices in minutes with Tessel". tessel.io. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "Node.js Raspberry Pi GPIO Introduction". w3schools.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Espruino – JavaScript for Microcontrollers". espruino.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Looper, Jen (21 September 2015). "A Guide to JavaScript Engines for Idiots". Telerik Developer Network. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ "How Blink Works". Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Documentation · V8". Google. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ Nelaturu, Keerthi (September 2020). "WebAssembly: What's the big deal?". medium.com. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Concurrency model and Event Loop". Mozilla Developer Network. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Flanagan, David (17 August 2006). JavaScript: The Definitive Guide. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-596-55447-7. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Korolev, Mikhail (1 March 2019). "JavaScript quirks in one image from the Internet". The DEV Community. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "Proposal-bigint/ADVANCED.md at master · tc39/Proposal-bigint". GitHub.

- ^ Bernhardt, Gary (2012). "Wat". Destroy All Software. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ "JavaScript data types and data structures". MDN. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Flanagan 2006, pp. 176–178.

- ^ Crockford, Douglas. "Prototypal Inheritance in JavaScript". Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ "Inheritance and the prototype chain". Mozilla Developer Network. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Herman, David (2013). Effective JavaScript. Addison-Wesley. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-321-81218-6.

- ^ Ghandi, Raju (2019). JavaScript Next. New York City: Apress Media. pp. 159–171. ISBN 978-1-4842-5394-6.

- ^ a b Haverbeke, Marijn (September 2024). Eloquent JavaScript (PDF) (4th ed.). San Francisco: No Starch Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-1-71850-411-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2025.

- ^ Katz, Yehuda (12 August 2011). "Understanding "Prototypes" in JavaScript". Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Herman, David (2013). Effective JavaScript. Addison-Wesley. pp. 125–127. ISBN 978-0-321-81218-6.

- ^ "Function – JavaScript". MDN Web Docs. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Properties of the Function Object". Es5.github.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Flanagan 2006, p. 141.

- ^ The many talents of JavaScript for generalizing Role-Oriented Programming approaches like Traits and Mixins Archived 2017-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, Peterseliger.blogspot.de, April 11, 2014.

- ^ Traits for JavaScript Archived 2014-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, 2010.

- ^ "Home | CocktailJS". Cocktailjs.github.io. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Croll, Angus (31 May 2011). "A fresh look at JavaScript Mixins". JavaScript, JavaScript…. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020.

- ^ "E4X – Archive of obsolete content". Mozilla Developer Network. Mozilla Foundation. 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "var – JavaScript". The Mozilla Developer Network. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ "let". MDN web docs. Mozilla. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "const". MDN web docs. Mozilla. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Making JavaScript Safe for Advertising". ADsafe. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "Secure ECMA Script (SES)". Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Google Caja Project". Google. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Mozilla Cross-Site Scripting Vulnerability Reported and Fixed – MozillaZine Talkback". Mozillazine.org. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Kottelin, Thor (17 June 2008). "Right-click "protection"? Forget about it". blog.anta.net. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Rehorik, Jan (29 November 2016). "Why You Should Never Put Sensitive Data in Your JavaScript". ServiceObjects Blog. ServiceObjects. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ a b Lauinger, Tobias; Chaabane, Abdelberi; Arshad, Sajjad; Robertson, William; Wilson, Christo; Kirda, Engin (21 December 2016), "Thou Shalt Not Depend on Me: Analysing the Use of Outdated JavaScript Libraries on the Web" (PDF), Northeastern University, arXiv:1811.00918, doi:10.14722/ndss.2017.23414, ISBN 978-1-891562-46-4, S2CID 17885720, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017, retrieved 28 July 2022

- ^ Collins, Keith (27 March 2016). "How one programmer broke the internet by deleting a tiny piece of code". Quartz. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ SC Magazine UK, Developer's 11 lines of deleted code 'breaks the internet' Archived February 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mozilla Corporation, Buffer overflow in crypto.signText() Archived 2014-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Festa, Paul (19 August 1998). "Buffer-overflow bug in IE". CNET. Archived from the original on 25 December 2002.

- ^ SecurityTracker.com, Apple Safari JavaScript Buffer Overflow Lets Remote Users Execute Arbitrary Code and HTTP Redirect Bug Lets Remote Users Access Files Archived 2010-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SecurityFocus, Microsoft WebViewFolderIcon ActiveX Control Buffer Overflow Vulnerability Archived 2011-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fusion Authority, Macromedia Flash ActiveX Buffer Overflow Archived August 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Protected Mode in Vista IE7 – IEBlog". Blogs.msdn.com. 9 February 2006. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ US CERT, Vulnerability Note VU#713878: Microsoft Internet Explorer does not properly validate source of redirected frame Archived 2009-10-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mozilla Foundation, Mozilla Foundation Security Advisory 2005–41: Privilege escalation via DOM property overrides Archived 2014-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Andersen, Starr (9 August 2004). "Part 5: Enhanced Browsing Security". TechNet. Microsoft Docs. Changes to Functionality in Windows XP Service Pack 2. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ For one example of a rare JavaScript Trojan Horse, see Symantec Corporation, JS.Seeker.K Archived 2011-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gruss, Daniel; Maurice, Clémentine; Mangard, Stefan (24 July 2015). "Rowhammer.js: A Remote Software-Induced Fault Attack in JavaScript". arXiv:1507.06955 [cs.CR].

- ^ Jean-Pharuns, Alix (30 July 2015). "Rowhammer.js Is the Most Ingenious Hack I've Ever Seen". Motherboard. Vice. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Goodin, Dan (4 August 2015). "DRAM 'Bitflipping' exploit for attacking PCs: Just add JavaScript". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Auerbach, David (28 July 2015). "Rowhammer security exploit: Why a new security attack is truly terrifying". slate.com. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ AnC Archived 2017-03-16 at the Wayback Machine VUSec, 2017

- ^ New ASLR-busting JavaScript is about to make drive-by exploits much nastier Archived 2017-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Ars Technica, 2017

- ^ Spectre Attack Archived 2018-01-03 at the Wayback Machine Spectre Attack

- ^ "Benchmark.js". benchmarkjs.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ JSBEN.CH. "JSBEN.CH Performance Benchmarking Playground for JavaScript". jsben.ch. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Eich, Brendan (3 April 2008). "Popularity". Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ "Edge Browser Switches WebAssembly to 'On' -- Visual Studio Magazine". Visual Studio Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "frequently asked questions". asm.js. Archived from the original on 4 June 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Flanagan, David (2020). JavaScript: The Definitive Guide (7th ed.). Sebastopol, California: O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-491-95202-3.

- Haverbeke, Marijn (2024). Eloquent JavaScript (PDF) (4th ed.). San Francisco: No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-71850-411-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2025.

- Zakas, Nicholas (2014). Principles of Object-Oriented JavaScript (1st ed.). No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-59327-540-2.

External links

[edit]- The Modern JavaScript Tutorial. A community maintained continuously updated collection of tutorials on the entirety of the language.

- "JavaScript: The First 20 Years". Retrieved 6 February 2022.

JavaScript

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins at Netscape

JavaScript originated in the mid-1990s at Netscape Communications Corporation, where Brendan Eich, a newly hired developer, was tasked with creating a scripting language for the web browser. In early to mid-May 1995, Eich prototyped the language under the code name Mocha, drawing inspiration from existing languages like Scheme and Self for its prototype-based object model.[8][9] By late 1995, amid internal discussions and to align with Netscape's strategic partnerships, the name was changed first to LiveScript and then to JavaScript in December, partly to capitalize on the rising popularity of Sun Microsystems' Java programming language, with its syntax adopted for developer familiarity.[8][2] The language was rapidly integrated into Netscape Navigator 2.0, debuting in the browser's beta releases starting in September 1995, with the JavaScript name appearing in Beta 3 that December.[8][2] This marked JavaScript's first public implementation as a client-side scripting tool embedded directly in the browser, allowing developers to enhance HTML documents without requiring server-side processing or additional plugins.[9] Netscape designed JavaScript primarily to enable dynamic and interactive web experiences, addressing the limitations of static HTML pages prevalent at the time. Its core objectives included supporting interactive web forms for user input validation, simple animations to bring pages to life, and basic client-side logic to perform computations and decisions directly in the browser, thereby reducing the need for roundtrips to the server.[9][8] Among its inaugural features, JavaScript introduced rudimentary event handling to respond to user interactions, such as mouse clicks or form submissions, and early prototypes for manipulating the Document Object Model (DOM), which allowed scripts to access and modify HTML elements dynamically.[9] These capabilities laid the groundwork for more responsive web interfaces, though the initial implementation was basic and tied closely to Netscape's proprietary extensions.[8]Early Adoption and Standardization

Following the initial release of JavaScript in Netscape Navigator 2.0, Microsoft responded by developing its own implementation, JScript, which was introduced with Internet Explorer 3.0 on August 13, 1996.[10] This move intensified the "browser wars" between Netscape and Microsoft, as each company extended the language with proprietary features to gain competitive advantage, resulting in significant compatibility issues for web developers who had to write version-specific code for different browsers.[11] To mitigate these fragmentation risks and promote interoperability, Netscape submitted JavaScript to Ecma International for standardization in November 1996.[12] The effort culminated in the first edition of the ECMAScript standard (ES1, ECMA-262), approved in June 1997, which defined the core syntax, semantics, and behavior of the language while aligning implementations from Netscape and Microsoft.[13] JavaScript's adoption surged during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, as the explosive growth of the web—fueled by rising internet users and online businesses—demanded more interactive experiences beyond static HTML pages.[14] Developers increasingly used it for client-side enhancements in dynamic websites, such as real-time form validation in e-commerce applications, which improved user interaction by checking inputs like email addresses or credit card numbers without server round-trips.[15] Subsequent standardization efforts refined the language: the second edition (ES2) was released in August 1998, primarily incorporating editorial clarifications and minor alignments to international standards without adding new features.[16] The third edition (ES3), published in December 1999, introduced key capabilities including regular expressions for pattern matching in strings and try-catch blocks for structured exception handling, enhancing error management and text processing in web scripts.[17]Maturation and Modern Evolution

By the late 1990s, JavaScript's popularity waned amid the browser wars, where incompatibilities between Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer implementations led to fragmented support and developer frustration with its error-prone nature.[18] This decline reversed in 2005 with the rise of Ajax, driven by the standardization of the XMLHttpRequest API, which enabled dynamic web applications without full page reloads and reignited interest in client-side scripting.[19] The release of ECMAScript 5 (ES5) in December 2009 marked a significant maturation, introducing strict mode for enhanced error checking, native JSON support for data interchange, and new array methods such as forEach, map, and filter to simplify iteration and manipulation.[20] These additions improved code reliability and interoperability across browsers, laying groundwork for more robust web development. ECMAScript 6 (ES2015), finalized in June 2015, represented a revolutionary update by incorporating object-oriented classes, concise arrow functions for lexical this binding, promises for asynchronous programming, and native modules for better code organization.[21] Following this, the ECMAScript specification shifted to annual releases; for instance, ES2020 introduced BigInt for arbitrary-precision integers beyond the Number type's limits, while ES2023 added immutable array methods like toSorted, toReversed, and with to promote safer data handling without mutating originals.[22] To bridge gaps in browser support for these evolving features, transpilers like Babel emerged around 2015, converting modern syntax—such as arrow functions and classes—into ES5-compatible code while integrating polyfills for runtime behaviors like promises.[23] Concurrently, Node.js, first released in 2009 by Ryan Dahl, expanded JavaScript to server-side environments using the V8 engine, enabling full-stack development and powering scalable applications like Netflix's streaming backend.[24] In the 2020s, JavaScript's ecosystem continued advancing with proposals for deeper hardware integration, including WebGPU—a W3C Candidate Recommendation API since 2023—that allows JavaScript access to GPU compute shaders for graphics and machine learning tasks directly in browsers.[25] Additionally, the Temporal API, which reached stage 3 in the TC39 process in March 2021 and has remained at that stage through 2025, previews a comprehensive overhaul of date and time handling in ES2025, offering immutable, time-zone-aware objects to replace the legacy Date constructor's limitations.[26]Branding and Standards

Trademark and Naming

The name "JavaScript" originated in 1995 when Netscape Communications Corporation, in partnership with Sun Microsystems, rebranded its scripting language from LiveScript to capitalize on the popularity of Sun's Java programming language, despite no technical relation between the two.[27] The language had initially been developed by Brendan Eich at Netscape under the codename Mocha earlier that year, before the interim name LiveScript.[9] This marketing-driven renaming was part of a licensing agreement between Netscape and Sun, allowing Netscape to use the "JavaScript" name to evoke synergy with Java's emerging brand.[27] Sun Microsystems formally applied for the "JavaScript" trademark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) in December 1995, with registration granted on December 26, 2000 (Serial No. 75026640).[28] Following Oracle Corporation's acquisition of Sun in 2010, Oracle inherited ownership of the trademark.[29] Oracle has since licensed the "JavaScript" name to entities like the Mozilla Foundation for their implementations. However, as of November 2025, the trademark's status is under challenge through a pending cancellation proceeding filed on November 22, 2024 (announced publicly on November 25, 2024), by Deno Land Inc., arguing that "JavaScript" has become generic; the case remains unresolved following Oracle's responses and procedural delays.[28][30][31][32] Oracle maintains it as a proprietary brand distinct from the open standard.[33] To distinguish the standardized specification from the trademarked brand and avoid confusion with the unrelated Java trademark (also owned by Oracle), the European standards body Ecma International adopted "ECMAScript" as the official name for the language standard in 1997.[33] Usage guidelines emphasize referring to the standard as ECMAScript, reserving "JavaScript" for Netscape- and Mozilla-derived implementations, thereby preventing brand dilution or legal conflicts with Java.[33] When Microsoft developed its ECMAScript implementation in 1996, it named it JScript to sidestep potential trademark infringement claims from Netscape and Sun regarding "JavaScript." This approach aligned with the push toward standardization, culminating in Microsoft's participation in the Ecma process, which helped unify browser scripting without direct trademark disputes.[34]ECMAScript Specification Process

The ECMAScript specification is developed and maintained by Ecma Technical Committee 39 (TC39), a working group under Ecma International responsible for evolving the language through consensus-driven processes.[35] TC39 oversees the annual release of new ECMAScript editions, incorporating features via a structured proposal pipeline that ensures rigorous review and implementation feasibility. Proposals advance through five stages: Stage 0 (strawperson) for initial ideation without formal committee endorsement; Stage 1 for establishing a proposal with a champion and addressing key concerns; Stage 2 for drafting a preferred solution with preliminary specification text; Stage 3 for candidate status, where the feature is deemed complete for implementation with minimal further changes; and Stage 4 for finished proposals ready for inclusion in the standard, requiring at least two independent implementations and comprehensive tests.[35] This process promotes transparency and collaboration, with all discussions and documents publicly available on GitHub repositories under the TC39 organization.[36] Key historical milestones shaped the modern specification process. In 2008, efforts to develop ECMAScript 4 (ES4) were abandoned due to disagreements over its increased complexity and potential for fragmentation among implementations, leading instead to the more incremental ECMAScript 5 (ES5) released in 2009, which focused on harmonizing existing features while adding strict mode and JSON support.[37] Following ES5, the process evolved significantly with ECMAScript 2015 (ES6), introducing major enhancements like classes and modules; this paved the way for a shift to annual releases starting with ECMAScript 2016, allowing for steady, predictable evolution rather than infrequent large updates.[38] Throughout these changes, backward compatibility has remained a foundational principle, ensuring that new editions do not break existing codebases unless explicitly addressing legacy issues, as emphasized in TC39's guidelines for proposal advancement.[35] Contributions to the specification come from a diverse set of delegates, including representatives from major browser vendors such as Google (V8 engine), Apple (JavaScriptCore), and Mozilla (SpiderMonkey), alongside other Ecma members like Microsoft and IBM.[39] The community plays a vital role through public GitHub repositories, where anyone can submit ideas, review drafts, or contribute tests via the Test262 suite, fostering broad input beyond corporate stakeholders.[40] Since the 2010s, TC39 has intensified inclusivity efforts, adopting a Code of Conduct in 2017 to promote diversity by welcoming participants from varied backgrounds and prohibiting discrimination, with a dedicated committee to handle reports and ensure safe collaboration spaces.[41] As of November 2025, the process continues to prioritize backward compatibility while advancing innovative features; for instance, the Temporal proposal for improved date and time handling remains in Stage 3, undergoing implementation testing before potential inclusion in a future edition.[26] This ongoing cadence reflects TC39's commitment to balancing evolution with stability, enabling JavaScript to adapt to modern needs without disrupting its vast ecosystem.[38]Usage Contexts

Client-Side Web Development

JavaScript serves as the primary scripting language for client-side web development, enabling dynamic interactivity within web browsers by allowing developers to manipulate the Document Object Model (DOM) and respond to user events. The DOM represents the structured representation of HTML documents as a tree of objects, which JavaScript accesses through built-in browser APIs to create, modify, or delete elements, attributes, and content without requiring full page reloads.[42] This manipulation facilitates real-time updates to user interfaces, such as inserting new elements or altering text and styles in response to user actions. Event listeners are a core mechanism in JavaScript for handling user interactions, such as mouse clicks, keyboard inputs, and form submissions, by attaching callback functions to DOM elements via theaddEventListener() method.[43] For instance, developers can use event listeners to validate form inputs on submission, checking for required fields or valid formats before processing, which improves user experience by providing immediate feedback without server round-trips. Another common application involves triggering CSS transitions or animations through JavaScript, where an event like a button click adds or removes CSS classes to smoothly animate elements, leveraging hardware-accelerated rendering for efficiency.[44] In single-page applications (SPAs), JavaScript integrates with the History API to manage navigation states, using methods like pushState() and popstate events to update the URL and content dynamically while maintaining browser back/forward functionality.[45]

JavaScript integrates seamlessly with HTML and CSS to form the foundational triad of web development, where scripts interact with HTML structures and CSS styles to produce responsive pages. Early practices often embedded JavaScript directly within HTML using inline <script> tags, but this approach led to parsing delays and hindered caching, prompting a shift to external .js files linked via <script src> attributes, which browsers can cache across sessions for improved load times and maintainability.[46] Modern best practices recommend deferring or asynchronously loading these external scripts to avoid blocking HTML rendering, further enhancing performance.

Support for JavaScript is universal across all modern web browsers, including Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Edge, ensuring consistent execution of core features like DOM manipulation and event handling without additional configuration. For legacy browsers lacking support for newer APIs, polyfills—JavaScript implementations that emulate missing functionality—can be included to bridge compatibility gaps, though their use has diminished as older browsers like Internet Explorer fade from relevance.[47] Key browser-provided APIs further extend JavaScript's capabilities in client-side contexts; for example, the Canvas API enables 2D drawing and graphics rendering directly in the browser, supporting applications from simple charts to complex games.[48] Similarly, the Fetch API provides a modern, promise-based interface for making HTTP requests, replacing older methods like XMLHttpRequest for asynchronous data retrieval and manipulation.[49]

Server-Side and Non-Web Environments

JavaScript, originally designed for client-side web scripting, has expanded significantly into server-side and non-web environments through dedicated runtimes and frameworks that leverage its asynchronous capabilities. Node.js, released in 2009 by Ryan Dahl, pioneered server-side JavaScript by providing an event-driven, non-blocking I/O model built on the V8 engine, enabling efficient handling of concurrent operations for applications like web servers, RESTful APIs, and command-line tools.[24][50] This architecture allows Node.js to process thousands of simultaneous connections without traditional threading, making it ideal for scalable backend services. Modern alternatives like Deno and Bun address some of Node.js's limitations, such as module resolution and security. Deno, introduced in 2018, offers secure-by-default execution with explicit permission prompts for file, network, and environment access, alongside zero-configuration TypeScript support.[51][52] Bun, launched in 2022, emphasizes speed with its JavaScriptCore engine and includes native TypeScript transpilation, a built-in bundler, and package manager for faster development workflows.[53][54] Beyond servers, JavaScript powers non-web applications across diverse platforms. For desktop software, Electron combines Chromium and Node.js to build cross-platform apps using web technologies; notable examples include Visual Studio Code, which relies on Electron for its interface and extensibility.[55][56] In mobile development, React Native enables native iOS and Android apps with JavaScript and React components, bridging to platform-specific UI elements for high-performance experiences.[57] For embedded systems and IoT, frameworks like Johnny-Five provide a JavaScript API for hardware interaction, supporting Arduino, Raspberry Pi, and sensors in robotics projects.[58] As of 2025, JavaScript's backend adoption remains strong, with the Stack Overflow Developer Survey indicating that 29.7% of developers used Node.js in the past year, reflecting its role in full-stack and serverless architectures.[59] For instance, Netflix employs Node.js-based serverless functions in its Functions-as-a-Service runtime to manage API platforms, handling high-scale microservices efficiently.[60]Execution Model

JavaScript Engines

JavaScript engines are the core software components responsible for parsing, compiling, and executing JavaScript code within browsers and other environments. These engines translate high-level JavaScript source code into machine-executable instructions, enabling dynamic interpretation or compilation at runtime to achieve both flexibility and performance. Modern engines predominantly employ just-in-time (JIT) compilation, which combines interpretation for quick startup with on-the-fly compilation of frequently executed code paths into optimized native machine code, significantly boosting execution speed compared to pure interpretation.[61] Prominent examples include Google's V8 engine, released in 2008 alongside Chrome and also powering Node.js, which uses a multi-tier JIT approach starting with an interpreter called Ignition that generates bytecode, followed by the TurboFan optimizing compiler for hot code paths. Mozilla's SpiderMonkey, originally developed in 1995 for Netscape Navigator and now integral to Firefox, employs tiered JIT compilation with a baseline interpreter, a baseline compiler for initial optimizations, and higher-tier compilers like WarpMonkey for aggressive inlining and machine code generation. Apple's JavaScriptCore, introduced in 2005 for Safari, similarly relies on JIT techniques, including early adoption of baseline and optimizing compilers to handle dynamic language features efficiently. These engines demonstrate JIT's role in adapting to JavaScript's dynamic typing by profiling runtime behavior and recompiling as needed.[62][63][64] The execution pipeline in these engines begins with lexical analysis, where source code is tokenized into identifiers, operators, and literals, followed by parsing to construct an abstract syntax tree (AST) representing the code's syntactic structure. The AST is then transformed into intermediate bytecode, a platform-independent representation suitable for interpretation, before JIT stages apply optimizations such as inline caching, which stores type and property access assumptions in caches to accelerate polymorphic operations without full recompilation. For instance, inline caching enables engines to predict and specialize property lookups based on observed types, deoptimizing and falling back if assumptions fail, thus balancing speed and correctness in dynamic contexts.[61] Performance advancements continue to drive engine evolution, exemplified by V8's TurboFan optimizer, enabled by default in 2017, which employs a "sea of nodes" intermediate representation for sophisticated graph-based optimizations, resulting in faster execution for complex workloads like those in modern web applications. Benchmarks such as JetStream evaluate these improvements by measuring latency, throughput, and geometric means across JavaScript and WebAssembly tests, highlighting engines' ability to handle real-world scenarios with quick startup and sustained performance. Cross-engine compatibility is maintained through rigorous adherence to the ECMAScript standard, verified via the official Test262 conformance test suite, which includes over 50,000 tests covering specification behaviors to ensure consistent implementation across engines.[65][66][40]Runtime and Concurrency