Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

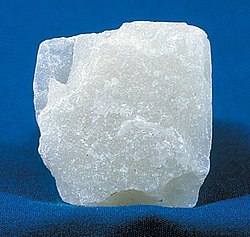

Soapstone

View on Wikipedia

Soapstone (also known as steatite or soaprock) is a talc-schist, which is a type of metamorphic rock. It is composed largely of the magnesium-rich mineral talc. It is produced by dynamothermal metamorphism and metasomatism, which occur in subduction zones, changing rocks by heat and pressure, with influx of fluids but without melting. It has been a carving medium for thousands of years.

Terminology

[edit]The definitions of the terms "steatite" and "soapstone" vary with the field of study. In geology, steatite is a rock that is, to a very large extent, composed of talc. The mining industry defines steatite as a high-purity talc rock that is suitable for the manufacturing of, for example, insulators; the lesser grades of the mineral can be called simply "talc rock". Steatite can be used both in lumps ("block steatite", "lava steatite", "lava grade talc"), and in the ground form. While the geologists logically will use "steatite" to designate both forms, in the industry, "steatite" without additional qualifications typically means the steatite that is either already ground or to be used in the ground form in the future. If the ground steatite is pressed together into blocks, these are called "synthetic block steatite", "artificial block steatite", or "artificial lava talc".[1]

In industrial applications soapstone refers to dimension stone that consists of either amphibole-chlorite-carbonate-talc rock, talc-carbonate rock, or simply talc rock and is sold in the form of sawn slabs. "Ground soapstone" sometimes designates the ground waste product of the slab manufacturing.[1]

Petrology

[edit]

Petrologically, soapstone is composed predominantly of talc, with varying amounts of chlorite and amphiboles (typically tremolite, anthophyllite, and cummingtonite, hence its obsolete name, magnesiocummingtonite), and traces of minor iron-chromium oxides. It may be schistose or massive. Soapstone is formed by the metamorphism of ultramafic protoliths (e.g. dunite or serpentinite) and the metasomatism of siliceous dolomites.

By mass, "pure" steatite is roughly 63% silica, 32% magnesia, and 5% water.[2] It commonly contains minor quantities of other oxides such as CaO or Al2O3.

Pyrophyllite, a mineral very similar to talc, is sometimes called soapstone in the generic sense, since its physical characteristics and industrial uses are similar,[3] and because it is also commonly used as a carving material. However, this mineral typically does not have as soapy a feel as soapstone.

Physical characteristics

[edit]Soapstone is relatively soft because of its high proportion of talc, which has a definitional value of 1 on the Mohs hardness scale. Softer grades may feel similar to soap when touched, hence the name. The hardness of soapstone varies due to its varying talc content, from as little as 30% for architectural grades such as those used on countertops, to as much as 80% for carving grades.

Soapstone is easy to carve; it is also durable and heat-resistant and has a high heat storage capacity. It has therefore been used for cooking and heating equipment for thousands of years.[4]

Soapstone is often used as an insulator for housing and electrical components, due to its durability and electrical characteristics and because it can be pressed into complex shapes before firing. Soapstone undergoes transformations when heated to temperatures of 1,000–1,200 °C (1,830–2,190 °F) into enstatite and cristobalite; on the Mohs scale, this corresponds to an increase in hardness to 5.5–6.5.[5] The resulting material, harder than glass, is sometimes called "lava".[6]

Historical use

[edit]Africa

[edit]Ancient Egyptian scarab signets and amulets were most commonly made from glazed steatite.[7] The Yoruba people of West Nigeria used soapstone for several statues, most notably at Esie, where archaeologists have uncovered hundreds of male and female statues about half of life size. The Yoruba of Ife also produced a miniature soapstone obelisk with metal studs called "the staff of Oranmiyan".

Soapstone mining in Tabaka, Kenya occurs in relatively shallow and accessible quarries in the surrounding areas of Sameta, Nyabigege and Bomware.[8] These were at the time open to all to access provided they had the labor resources to do so. This mostly meant the men did the mining as they were custodian to the community land, meaning ancestral lands in Riamosioma, Itumbe, Nyatike etc.[9]

Americas

[edit]Native Americans have used soapstone since the Late Archaic period. During the Archaic archaeological period (8000–1000 BC), bowls, cooking slabs, and other objects were made from soapstone.[10] The use of soapstone cooking vessels during this period has been attributed to the rock's thermal qualities; compared to clay or metal containers, soapstone retains heat more effectively.[11] Use of soapstone in native American cultures continues to the modern day. Later, other cultures carved soapstone smoking pipes, a practice that continues today. The soapstone's low heat conduction allows for prolonged smoking without the pipe heating up uncomfortably.[12]

Indigenous peoples of the Arctic have traditionally used soapstone for carvings of both practical objects and art. The qulliq, a type of oil lamp, is carved out of soapstone and used by the Inuit and Dorset peoples.[13] The soapstone oil lamps indicate these people had easy access to oils derived from marine mammals.[14]

In the modern period, soapstone is commonly used for carvings in Inuit art.[15]

In the United States, locally quarried soapstone was used for gravemarkers in 19th century northeast Georgia, around Dahlonega, and Cleveland as simple field stone and "slot and tab" tombs.

In Canada, soapstone was quarried in the Arctic regions like the western part of the Ungava Bay and the Appalachian Mountain System from Newfoundland.[16]

Asia

[edit]

The ancient trading city of Tepe Yahya in southeastern Iran was a center for the production and distribution of soapstone in the 5th to 3rd millennia BC.[17]

Soapstone has been used in India as a medium for sculptures since at least the time of the Hoysala Empire, the Western Chalukya Empire and to an extent Vijayanagara Empire.[18]

Even earlier, steatite was used as the substrate for Indus-Harappan seals.[19][20] After the intricate carvings of icons and (yet undeciphered) symbols, the seals were heated above 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) for several days to make them hard and durable to make the final seals used for making impressions on clay.

In China, during the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BC), soapstone was carved into ceremonial knives.[21] Soapstone was also used to carve Chinese seals.

Soapstone was used as a writing pencil in Myanmar as early as the 11th-century Pagan period. After that, it was still used as a pencil to write on Black Parabaik until the end of the Mandalay period (19th century).

Australia

[edit]Pipes and decorative carvings of local animals were made out of soapstone by Australian Aboriginal artist Erlikilyika (c. 1865 – c. 1930) in Central Australia.[22]

Europe

[edit]The Minoan civilization on Crete used soapstone. At the Palace of Knossos, a steatite libation table was found.[23] Soapstone is relatively abundant in northern Europe. During the Viking Age, soapstone was the primary cooking vessel material in Norway.[24] Vikings hewed soapstone directly from the stone face, shaped it into cooking pots, and sold these at home and abroad.[25] In Shetland, there is evidence that these vessels were used for processing marine and dairy fats.[26] Several surviving medieval buildings in northern Europe are constructed with soapstone, amongst them Nidaros Cathedral.[4]

Modern use

[edit]

In modern times, soapstone is most commonly used for architectural applications, such as counter tops, floor tiles, showerbases, and interior surfacing.

Soapstone is sometimes used for construction of fireplace surrounds, cladding on wood-burning stoves,[27][28] and as the preferred material for woodburning masonry heaters because it can absorb, store, and evenly radiate heat due to its high density and magnesite (MgCO3) content.[27][28] It is also used for countertops and bathroom tiling because of the ease of working the material and its property as the "quiet stone". A weathered or aged appearance occurs naturally over time as the patina is enhanced.

Soapstone can be used to create molds for casting objects from soft metals, such as pewter or silver. The soft stone is easily carved and is not degraded by heating. The slick surface of soapstone allows the finished object to be easily removed.

Welders and fabricators use soapstone as a marker due to its resistance to heat; it remains visible when heat is applied. It has also been used for many years by seamstresses, carpenters, and other craftspeople as a marking tool, because its marks are visible but not permanent.

Resistance to heat made steatite suitable for manufacturing gas burner tips, spark plugs, and electrical switchboards.[6]

Ceramics

[edit]Steatite ceramics are low-cost biaxial porcelains of nominal composition (MgO)3(SiO2)4.[29] Steatite is used primarily for its dielectric and thermally-insulating properties in applications such as tile, substrates, washers, bushings, beads, and pigments.[30] It is also used for high-voltage insulators, which have to stand large mechanical loads, such as insulators of mast radiators.

Crafts

[edit]Soapstone continues to be used for carvings and sculptures by artists and indigenous peoples. In Brazil, especially in the state of Minas Gerais, the abundance of soapstone mines allow local artisans to craft pots, pans, wine glasses, statues, jewel boxes, coasters, and vases from soapstone. These handicrafts are commonly sold in street markets found in cities across the state. Some of the oldest towns, notably Congonhas, Tiradentes, and Ouro Preto, still have some of their streets paved with soapstone from colonial times.

Mining

[edit]Architectural soapstone is mined in Canada, Brazil, India, and Finland and imported into the United States.[31] Active North American mines include one south of Quebec City with products marketed by Canadian Soapstone, the Treasure and Regal mines in Beaverhead County, Montana mined by the Barretts Minerals Company, and another in central Virginia operated by the Alberene Soapstone Company.

Mining to meet worldwide demand for soapstone is threatening the habitat of India's tigers.[32]

Other

[edit]Soapstones can be put in a freezer and later used in place of ice cubes to chill alcoholic beverages without diluting. Sometimes called whiskey stones, these were introduced around 2007.[33] Most whiskey stones feature a semipolished finish, retaining the soft look of natural soapstone, while others are highly polished.

Safety

[edit]People can be exposed to soapstone dust in the workplace via inhalation and skin or eye contact. Exposure above safe limits can lead to symptoms including coughing, shortness of breath, cyanosis, crackles, and pulmonary heart disease. Due to the potential presence of tremolite and crystalline silica in the dust, precautions should be taken to avoid occupational diseases such as asbestosis, silicosis, mesothelioma, and lung cancer.[34]

United States

[edit]The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for soapstone exposure in the workplace as 20 million particles per cubic foot over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has set a recommended exposure limit of 6 mg/m3 total exposure and 3 mg/m3 respiratory exposure over an 8-hour workday. At levels of 3000 mg/m3, soapstone is immediately dangerous to life and health.[35]

Other names

[edit]The local names for the soapstone vary: in Vermont, "grit" is used, in Georgia "white-grinding" and "dark-grinding" varieties are distinguished, and California has "soft", "hard", and "blue" talc.[36] Also:

- Combarbalite stone, exclusively mined in Combarbalá, Chile, is known for its many colors. While they are not visible during mining, they appear after refining.

- Palewa and gorara stones are types of Indian soapstone.

- A variety of other regional and marketing names for soapstone are used.[37]

Gallery

[edit]-

A 12th-century Byzantine relief of Saint George and the Dragon

-

Soapstone slot-and-tab tomb in Dahlonega, Georgia

-

A fountain made with soapstone, near Our Lady of Good Voyage Cathedral, in Belo Horizonte, Brazil

-

An Egyptian carved and glazed steatite scarab amulet

-

Steatite scarab at the Walters Art Museum

-

Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, Norway, constructed mainly of soapstone

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Chidester, Engel & Wright 1963, p. 8.

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (1995). "Talc" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. II (Silica, Silicates). Chantilly, VA: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209716.

- ^ Virta, Robert L. (2017). Minerals Yearbook Metals and Minerals 2010. Government Printing Office. p. 75.1. ISBN 9788290273908. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b Hansen, Gitte; Storemyr, Per (2017). A Versatile Resource – The Procurement and Use of Soapstone in Norway and The North Atlantic Region. In: Soapstone in the North Quarries, Products and People 7000 BC – AD 1700. UBAS – University of Bergen Archaeological Series 9. Bergen, Norway. ISBN 978-82-90273-90-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Some Important Aspects of the Harappan Technological Tradition," Bhan KK, Vidale M and Kenoyer JM, in Indian Archaeology in Retrospect/edited by S. Settar and Ravi Korisettar, Manohar Press, New Delhi, 2002.

- ^ a b Hall, A. L. (1927). "On the talc deposits near Kaapmuiden, in the Eastern Transvaal". Transactions of the Geological Society of South Africa. 30: 83.

- ^ Aldred, Cyril (1971). Jewels of the Pharaohs Egyptian Jewellery of the Dynastic Period. Thames and Hudson. pp. 160–161. ISBN 0500231389.

- ^ Akama, John (2018-08-14). "The Evolution and Resilience of the Gusii Soapstone Industry". Journal of African Cultural Heritage Studies. 1 (1): 1–17. doi:10.22599/jachs.31. ISSN 2513-8243. S2CID 169646064.

- ^ Akama, John (2018-08-14). "The Evolution and Resilience of the Gusii Soapstone Industry". Journal of African Cultural Heritage Studies. 1 (1): 1. doi:10.22599/jachs.31. ISSN 2513-8243. S2CID 169646064.

- ^ Kenneth E. Sassaman (1993-03-30). Early Pottery in the Southeast: Tradition and Innovation in Cooking Technology. University Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0670-0.

- ^ Frink, Liam; Glazer, Dashiell; Harry, Karen G. (October 2012). "Canadian Arctic Soapstone Cooking Technology". North American Archaeologist. 33 (4): 429–449. doi:10.2190/NA.33.4.c. ISSN 0197-6931.

- ^ Witthoft, J.G. (1949). "Stone pipes of the historic Cherokees". Southern Indian Studies. 1 (2): 43–62.

- ^ Erwin, John C. (2016). "A Large-Scale Systematic Study of Dorset and Groswater Soapstone Vessel Fragments from Newfoundland and Labrador". Arctic. 69: 1–8. doi:10.14430/arctic4592. ISSN 0004-0843. JSTOR 26891240.

- ^ "Civilization.ca – Life and Art of an Ancient Arctic People – The Dorset People". www.historymuseum.ca. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ Nuttall, Mark (2005-09-23). Encyclopedia of the Arctic. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-78680-8.

- ^ O'Driscoll, Cynthia Marie (2003). The application of trace element geochemistry to determine the provenance of soapstone vessels from Dorset Palaeoeskimo sites in western Newfoundland (masters thesis). Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- ^ "Tepe Yahya," Encyclopædia Britannica, 2004. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 3 January 2004, Britannica.com

- ^ UGC NET History Paper II Chapter Wise Notebook | Complete Preparation Guide. EduGorilla. 1 September 2022. p. 485. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ Pruthi, R. K. (2004). Indus Civilization. Discovery Publishing House. p. 225. ISBN 978-81-7141-865-7.

- ^ a b "Soapstone sculptures". hoysala.in. 2008. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Steatite Knife" at the Bath Museum of East Asian Art

- ^ Kelham, Megg (November 2010). "A museum in Finke: An Aputula Heritage project" (PDF). Territory Stories. pp. 1–97. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-10. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan (2007) "Knossos Fieldnotes", The Modern Antiquarian

- ^ Arne Skjølsvold, Klebersteinsindustrien i vikingtiden, Universitetsforlaget, 1961

- ^ Else Rosendahl, The Vikings, The Penguin Press, 1987, page 105

- ^ Steele, Val. "Report on the analysis of residues from steatite and ceramic vessels from the site of Belmont, Shetland" (PDF). Shetland Amenity.

- ^ a b Weideman, Paul (2017-11-05). "There's a stove for every taste". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ a b Damrosch, Barbara (2017-01-19). "The enduring appeal of wood stoves". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ "Royalty Minerals". royaltyminerals.in. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Superior Technical Ceramics". Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Soapstone gives countertops, tiles a look that's both new and old". The Washington Post. 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ^ Barnett, Antony (2003-06-22). "West's love of talc threatens India's tigers". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ "Interview with the Inventor of Whisky Stones, Andrew Hellman". Whisky Stones. 2017-04-21. Archived from the original on 2025-04-02. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- ^ Proctor, Nick H.; Hughes, James P.; Hathaway, Gloria J. (2004). Proctor and Hughes' Chemical hazards of the workplace (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-26883-3.

- ^ "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Soapstone (containing less than 1% quartz)". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ^ Chidester, Engel & Wright 1963, pp. 8–9.

- ^ "CST Personal Home Pages". cst.cmich.edu. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

General and cited references

[edit]- Chidester, Alfred Herman; Engel, Albert Edward John; Wright, Lauren Albert (1963). Talc resources of the United States (PDF). Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

Further reading

[edit]- Felce, Robert (2011). Soaprock Coast... The origins of English porcelain. ISBN 978-0-956-9895-0-5.

External links

[edit]- Soapstone Calculated Refractory Data w/ Technical Properties Converter (Incl. Soapstone Volume vs. Weight measuring units)

- Ancient soapstone bowl (The Central States Archaeological Journal)

- Soapstone Native American quarries, Maryland Archived 2017-07-06 at the Wayback Machine (Geological Society of America)

- Prehistoric soapstone use in northeastern Maryland (Antiquity Journal)

- The Blue Rock Soapstone Quarry, Yancey County, NC (North Carolina Office of State Archaeology)

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Steatite historical marker in Decatur, Georgia

_-_several_colored_samples.jpg/250px-Soapstone_(Speckstein)_-_several_colored_samples.jpg)

_-_several_colored_samples.jpg/2000px-Soapstone_(Speckstein)_-_several_colored_samples.jpg)

![Soapstone sculpture on the Hoysala temple at Belur, India[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Belur2_retouched.jpg/120px-Belur2_retouched.jpg)