Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Trans-Neptunian object

View on Wikipedia

|

A trans-Neptunian object (TNO), also written transneptunian object,[1] is any minor planet in the Solar System that orbits the Sun at a greater average distance than Neptune, which has an orbital semi-major axis of 30.1 astronomical units (AU).

Typically, TNOs are further divided into the classical and resonant objects of the Kuiper belt, the scattered disc and detached objects with the sednoids being the most distant ones.[nb 1] As of February 2025, the catalog of minor planets contains 1006 numbered and more than 4000 unnumbered TNOs.[3][4][5][6][7] However, nearly 5900 objects with semimajor axis over 30 AU are present in the MPC catalog, with 1009 being numbered.

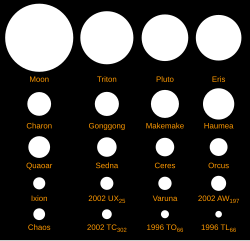

The first trans-Neptunian object to be discovered was Pluto in 1930. It took until 1992 to discover a second trans-Neptunian object orbiting the Sun directly, 15760 Albion. The most massive TNO known is Eris, followed by Pluto, Haumea, Makemake, and Gonggong. More than 80 satellites have been discovered in orbit of trans-Neptunian objects. TNOs vary in color and are either grey-blue (BB) or very red (RR). They are thought to be composed of mixtures of rock, amorphous carbon and volatile ices such as water and methane, coated with tholins and other organic compounds.

Twelve minor planets with a semi-major axis greater than 150 AU and perihelion greater than 30 AU are known, which are called extreme trans-Neptunian objects (ETNOs).[8]

History

[edit]Discovery of Pluto

[edit]

The orbit of each of the planets is slightly affected by the gravitational influences of the other planets. Discrepancies in the early 1900s between the observed and expected orbits of Uranus and Neptune suggested that there were one or more additional planets beyond Neptune. The search for these led to the discovery of Pluto in February 1930, which was progressively determined to be too small to explain the discrepancies. Revised estimates of Neptune's mass from the Voyager 2 flyby in 1989 showed that there is no real discrepancy: The problem was an error in the expectations for the orbits.[9] Pluto was easiest to find because it is the brightest of all known trans-Neptunian objects. It also has a lower inclination to the ecliptic than most other large TNOs, so its position in the sky is typically closer to the search zone in the disc of the Solar System.

Subsequent discoveries

[edit]After Pluto's discovery, American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh continued searching for some years for similar objects but found none. For a long time, no one searched for other TNOs as it was generally believed that Pluto, which up to August 2006 was classified as a planet, was the only major object beyond Neptune. Only after the 1992 discovery of a second TNO, 15760 Albion, did systematic searches for further such objects begin. A broad strip of the sky around the ecliptic was photographed and digitally evaluated for slowly moving objects. Hundreds of TNOs were found, with diameters in the range of 50 to 2,500 kilometers. Eris, the most massive known TNO, was discovered in 2005, revisiting a long-running dispute within the scientific community over the classification of large TNOs, and whether objects like Pluto can be considered planets. In 2006, Pluto and Eris were classified as dwarf planets by the International Astronomical Union.

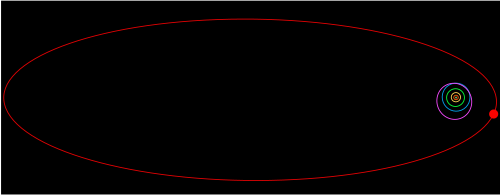

Classification

[edit]According to their distance from the Sun and their orbital parameters, TNOs are classified in two large groups: the Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) and the scattered disc objects (SDOs).[nb 1] The diagram below illustrates the distribution of known trans-Neptunian objects beyond the orbit of Neptune at 30.07 AU. Different classes of TNOs are represented in different colours. The main part of the Kuiper belt is shown in orange and blue between the 2:3 and 1:2 orbital resonances with Neptune. Plutinos (orange) are the objects in the 2:3 resonance, including the dwarf planets Pluto and Orcus. Classical Kuiper belt objects are shown in blue, with the largest of these, including Haumea, Makemake, and Quaoar in the dynamically 'hot' population in light blue, and the dynamically 'cold' population, including 486958 Arrokoth, in low-eccentricity orbits clustered near 44 AU in dark blue.

The scattered disc can be found beyond the Kuiper belt, shown in grey and purple. These objects, including dwarf planets Eris and Gonggong have been excited into eccentric orbits due to gravitational perturbations by Neptune, resulting in a concentration of their perihelia in the horizontal band between 30 and 40 AU. Some detached objects, such as (612911) 2004 XR190 however have higher perihelia. Centaurs, shown in green, have been perturbed from the scattered disc onto orbits crossing the outer planets. Bodies in both of these groups may be found in mean-motion resonances with Neptune; these are plotted in red.

Finally, extreme trans-Neptunian objects are shown at the right of the diagram, with many having orbits that extend over 1000 AU from the sun. These can be divided into the extended scattered disc (pink), including (768325) 2015 BP519, the distant detached objects (brown), including 2017 OF201, and the four known sednoids, including Sedna and 541132 Leleākūhonua.

KBOs

[edit]The Edgeworth–Kuiper belt contains objects with an average distance to the Sun of 30 to about 55 AU, usually having close-to-circular orbits with a small inclination from the ecliptic. Edgeworth–Kuiper belt objects are further classified into the resonant trans-Neptunian object that are locked in an orbital resonance with Neptune, and the classical Kuiper belt objects, also called "cubewanos", that have no such resonance, moving on almost circular orbits, unperturbed by Neptune. There are a large number of resonant subgroups, the largest being the twotinos (1:2 resonance) and the plutinos (2:3 resonance), named after their most prominent member, Pluto. Members of the classical Edgeworth–Kuiper belt include 15760 Albion, Quaoar and Makemake.

Another subclass of Kuiper belt objects is the so-called scattering objects (SO). These are non-resonant objects that come near enough to Neptune to have their orbits changed from time to time (such as causing changes in semi-major axis of at least 1.5 AU in 10 million years) and are thus undergoing gravitational scattering. Scattering objects are easier to detect than other trans-Neptunian objects of the same size because they come nearer to Earth, some having perihelia around 20 AU. Several are known with g-band absolute magnitude below 9, meaning that the estimated diameter is more than 100 km. It is estimated that there are between 240,000 and 830,000 scattering objects bigger than r-band absolute magnitude 12, corresponding to diameters greater than about 18 km. Scattering objects are hypothesized to be the source of the so-called Jupiter-family comets (JFCs), which have periods of less than 20 years.[10][11][12]

SDOs

[edit]The scattered disc contains objects farther from the Sun, with very eccentric and inclined orbits. These orbits are non-resonant and non-planetary-orbit-crossing. A typical example is the most-massive-known TNO, Eris. Based on the Tisserand parameter relative to Neptune (TN), the objects in the scattered disc can be further divided into the "typical" scattered disc objects (SDOs, Scattered-near) with a TN of less than 3, and into the detached objects (ESDOs, Scattered-extended) with a TN greater than 3. In addition, detached objects have a time-averaged eccentricity greater than 0.2[13] The sednoids are a further extreme sub-grouping of the detached objects with perihelia so distant that it is confirmed that their orbits cannot be explained by perturbations from the giant planets,[14] nor by interaction with the galactic tides.[15] However, a passing star could have moved them on their orbit.[16]

Physical characteristics

[edit]

Given the apparent magnitude (>20) of all but the biggest trans-Neptunian objects, the physical studies are limited to the following:

- thermal emissions for the largest objects (see size determination)

- colour indices, i.e. comparisons of the apparent magnitudes using different filters

- analysis of spectra, visual and infrared

Studying colours and spectra provides insight into the objects' origin and a potential correlation with other classes of objects, namely centaurs and some satellites of giant planets (Triton, Phoebe), suspected to originate in the Kuiper belt. However, the interpretations are typically ambiguous as the spectra can fit more than one model of the surface composition and depend on the unknown particle size. More significantly, the optical surfaces of small bodies are subject to modification by intense radiation, solar wind and micrometeorites. Consequently, the thin optical surface layer could be quite different from the regolith underneath, and not representative of the bulk composition of the body.

Small TNOs are thought to be low-density mixtures of rock and ice with some organic (carbon-containing) surface material such as tholins, detected in their spectra. On the other hand, the high density of Haumea, 2.6–3.3 g/cm3, suggests a very high non-ice content (compare with Pluto's density: 1.86 g/cm3). The composition of some small TNOs could be similar to that of comets. Indeed, some centaurs undergo seasonal changes when they approach the Sun, making the boundary blurred (see 2060 Chiron and 7968 Elst–Pizarro). However, population comparisons between centaurs and TNOs are still controversial.[17]

Color indices

[edit]

Colour indices are simple measures of the differences in the apparent magnitude of an object seen through blue (B), visible (V), i.e. green-yellow, and red (R) filters.[18] Correlations between the colours and the orbital characteristics have been studied, to confirm theories of different origin of the different dynamic classes:

- Classical Kuiper belt objects (cubewanos) seem to be composed of two different colour populations: the so-called cold (inclination <5°) population, displaying only red colours, and the so-called hot (higher inclination) population displaying the whole range of colours from blue to very red.[19] A recent analysis based on the data from Deep Ecliptic Survey confirms this difference in colour between low-inclination (named Core) and high-inclination (named Halo) objects. Red colours of the Core objects together with their unperturbed orbits suggest that these objects could be a relic of the original population of the belt.[20]

- Scattered disc objects show colour resemblances with hot classical objects pointing to a common origin.

While the relatively dimmer bodies, as well as the population as the whole, are reddish (V−I = 0.3–0.6), the bigger objects are often more neutral in colour (infrared index V−I < 0.2). This distinction leads to suggestion that the surface of the largest bodies is covered with ices, hiding the redder, darker areas underneath.[21]

| Color | Plutinos | Cubewanos | Centaurs | SDOs | Comets | Jupiter trojans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B–V | 0.895±0.190 | 0.973±0.174 | 0.886±0.213 | 0.875±0.159 | 0.795±0.035 | 0.777±0.091 |

| V–R | 0.568±0.106 | 0.622±0.126 | 0.573±0.127 | 0.553±0.132 | 0.441±0.122 | 0.445±0.048 |

| V–I | 1.095±0.201 | 1.181±0.237 | 1.104±0.245 | 1.070±0.220 | 0.935±0.141 | 0.861±0.090 |

| R–I | 0.536±0.135 | 0.586±0.148 | 0.548±0.150 | 0.517±0.102 | 0.451±0.059 | 0.416±0.057 |

Spectral type from visible and near-Infrared Observations

[edit]Among TNOs, as among centaurs, there is a wide range of colors from blue-grey (neutral) to very red, but unlike the centaurs, bimodally grouped into grey and red centaurs, the distribution for TNOs appears to be uniform.[17] The wide range of spectra differ in reflectivity in visible red and near infrared. Neutral objects present a flat spectrum, reflecting as much red and infrared as visible spectrum.[23] Very red objects present a steep slope, reflecting much more in red and infrared. A recent attempt at classification (common with centaurs) uses the total of four classes from BB (blue, or neutral color, average B−V = 0.70, V−R = 0.39, e.g. Orcus) to RR (very red, B−V = 1.08, V−R = 0.71, e.g. Sedna) with BR and IR as intermediate classes. BR (intermediate blue-red) and IR (moderately red) differ mostly in the infrared bands I, J and H.

Typical models of the surface include water ice, amorphous carbon, silicates and organic macromolecules, named tholins, created by intense radiation. Four major tholins are used to fit the reddening slope:

- Titan tholin, believed to be produced from a mixture of 90% N2 (nitrogen) and 10% CH4 (methane)

- Triton tholin, as above but with very low (0.1%) methane content

- (ethane) Ice tholin I, believed to be produced from a mixture of 86% H2O and 14% C2H6 (ethane)

- (methanol) Ice tholin II, 80% H2O, 16% CH3OH (methanol) and 3% CO2

As an illustration of the two extreme classes BB and RR, the following compositions have been suggested

- for Sedna (RR very red): 24% Triton tholin, 7% carbon, 10% N2, 26% methanol, and 33% methane

- for Orcus (BB, grey/blue): 85% amorphous carbon, +4% Titan tholin, and 11% H2O ice

Spectral types after the James Webb Space Telescope

[edit]Recent observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and in particular its high sensitivity with the NIRSpec instrument in the 0.7–5.3 μm range, have led to a new spectral classification for trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). This classification is based on the Discovering the Surface Composition of TNOs (DiSCo) Large program and, for the first time, incorporates not only spectral profiles but also how they relate to the surface composition of TNOs. Additionally to the discovery of species that had not been detected before, the most significant discoveries from the spectral study of TNOs with Webb is the prevalence of CO2 on the surface for TNOs, independently of the size, albedo, and color and the non-prevalence of water ice, clearly present only in 20% of the sample.[24]

The DiSCo compositional classes [24] show three distinct groups:

- Bowl-type: the only class with a clear absorption features of water ice all over the NIRSPEC spectral range, accompanied by silicates and some carbon dioxide (CO2). Due to the high presence of refractory material on the surface these objects show the lowest geometric albedo in the population.[24]

- Double-Dip: reddish objects in the visible with spectra dominated by CO2 (including the isotopologue 13CO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) The non-icy surface component is probably dominated by tholins with aliphatic stretching absorptions at 3.2 - 3.5 μm.[24][25][26]

- Cliff: the reddest objects below 1.2 μm, with chemically evolved surfaces dominated by methanol, CO2, CO, and irradiation byproducts of methanol bearing −OH, −CH and −NH groups.[27] These spectra also display additional complex bands, likely associated with OCN− and OCS.

The distribution of these groups shows no clear relation with physical parameters or dynamical class, except for the color in the visible and the fact that all cold classical TNOs belong to the Cliff class.[24] These three groups are also reproduced, with some differences, in centaurs[28](including active ones such as Chiron),[29] in Neptune Trojans,[30] and in ETNOs,[31] making them a useful reference for icy bodies throughout the Solar System. Similarities have also been noted with debris disk spectra.[32]

As expected given their peculiar compositions, the dwarf planets Eris and Makemake[33] do not fall into any of these groups. The same is true for large (~1000 km) dwarf planet candidates such as Quaoar, Gonggong, and Sedna, which show distinctive spectral profiles with irradiation products of methane.[34]

Size determination and distribution

[edit]

Characteristically, big (bright) objects are typically on inclined orbits, whereas the invariable plane regroups mostly small and dim objects.[21]

It is difficult to estimate the diameter of TNOs. For very large objects, with very well known orbital elements (like Pluto), diameters can be precisely measured by occultation of stars. For other large TNOs, diameters can be estimated by thermal measurements. The intensity of light illuminating the object is known (from its distance to the Sun), and one assumes that most of its surface is in thermal equilibrium (usually not a bad assumption for an airless body). For a known albedo, it is possible to estimate the surface temperature, and correspondingly the intensity of heat radiation. Further, if the size of the object is known, it is possible to predict both the amount of visible light and emitted heat radiation reaching Earth. A simplifying factor is that the Sun emits almost all of its energy in visible light and at nearby frequencies, while at the cold temperatures of TNOs, the heat radiation is emitted at completely different wavelengths (the far infrared).

Thus there are two unknowns (albedo and size), which can be determined by two independent measurements (of the amount of reflected light and emitted infrared heat radiation). TNOs are so far from the Sun that they are very cold, hence producing black-body radiation around 60 micrometres in wavelength. This wavelength of light is impossible to observe from the Earth's surface, but can be observed from space using, e.g. the Spitzer Space Telescope. For ground-based observations, astronomers observe the tail of the black-body radiation in the far infrared. This far infrared radiation is so dim that the thermal method is only applicable to the largest KBOs. For the majority of (small) objects, the diameter is estimated by assuming an albedo. However, the albedos found range from 0.50 down to 0.05, resulting in a size range of 1,200–3,700 km for an object of magnitude of 1.0.[35]

Notable objects

[edit]| Object | Description |

|---|---|

| 134340 Pluto | A dwarf planet, the first and largest trans-Neptunian object (TNO) discovered. It is the only TNO known to have an atmosphere. Hosts a system of five satellites and is the prototype plutino. |

| 15760 Albion | The prototype classical Kuiper belt object (KBO), and the first TNO discovered after Pluto. |

| (385185) 1993 RO | The next plutino discovered after Pluto. |

| (15874) 1996 TL66 | The first object identified as a scattered disc object. |

| 1998 WW31 | The first binary KBO discovered after Pluto. |

| 47171 Lempo | A plutino and triple system consisting of a central binary pair of similar size, and a third outer circumbinary satellite. |

| 20000 Varuna | A large classical KBO, known for its rapid rotation (6.3 h) and elongated shape. |

| 28978 Ixion | A large plutino, was considered to be among the largest KBOs upon discovery. |

| 50000 Quaoar | A dwarf planet and a large classical KBO. It has an elongated shape, albeit less elongated than Haumea. It has one known moon, Weywot, and two known rings that are both outside Quaoar's Roche limit. |

| 90377 Sedna | A distant dwarf planet, proposed for a new category named extended scattered disc (E-SDO),[36] detached objects,[37] distant detached objects (DDO)[38] or scattered-extended in the formal classification by DES.[13] |

| 90482 Orcus | A dwarf planet and the second-largest known plutino, after Pluto. Has a relatively large satellite, Vanth. |

| 136108 Haumea | A dwarf planet, the third-largest-known TNO. Notable for its two known satellites, rings, and unusually short rotation period (3.9 h). It is the most massive known member of the Haumea collisional family.[39][40] |

| 136472 Makemake | A dwarf planet, a classical KBO, and the fourth-largest known TNO.[41] |

| 136199 Eris | A dwarf planet, a scattered disc object, and currently the most massive known TNO. It has one known satellite, Dysnomia. |

| (612911) 2004 XR190 | A detached object whose orbit is highly inclined and lies outside the classical Kuiper belt. |

| 225088 Gonggong | A dwarf planet and the second-largest discovered scattered-disc object. Has one known satellite, Xiangliu. |

| (528219) 2008 KV42 | The first retrograde TNO, having an unusually high orbital inclination of 104°. |

| 471325 Taowu | Another retrograde TNO with an unusually high orbital inclination of 110°.[42] |

| 2012 VP113 | A sednoid with a large perihelion of 80 AU from the Sun (50 AU beyond Neptune). |

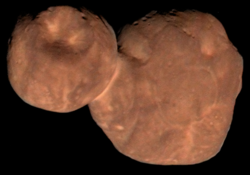

| 486958 Arrokoth | A contact binary classical KBO encountered by the New Horizons spacecraft in 2019. |

| 2018 VG18 | A scattered disc object, and the first TNO discovered while beyond 100 AU (15 billion km) from the Sun. |

| 2018 AG37 | The most distant observable TNO at 132 AU (19.7 billion km) from the Sun. |

Exploration

[edit]

The only mission to date that primarily targeted a trans-Neptunian object was NASA's New Horizons, which was launched in January 2006 and flew by the Pluto system in July 2015[43] and 486958 Arrokoth in January 2019.[44]

In 2011, a design study explored a spacecraft survey of Quaoar, Sedna, Makemake, Haumea, and Eris.[45]

In 2019 one mission to TNOs included designs for orbital capture and multi-target scenarios.[46][47]

Some TNOs that were studied in a design study paper were Uni, 1998 WW31, and Lempo.[47]

The existence of planets beyond Neptune, ranging from less than an Earth mass (Sub-Earth) up to a brown dwarf has been often postulated[48][49] for different theoretical reasons to explain several observed or speculated features of the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud. It was recently proposed to use ranging data from the New Horizons spacecraft to constrain the position of such a hypothesized body.[50]

NASA has been working towards a dedicated Interstellar Precursor in the 21st century, one intentionally designed to reach the interstellar medium, and as part of this the flyby of objects like Sedna are also considered.[51] Overall this type of spacecraft studies have proposed a launch in the 2020s, and would try to go a little faster than the Voyagers using existing technology.[51] One 2018 design study for an Interstellar Precursor, included a visit of minor planet 50000 Quaoar, in the 2030s.[52]

Extreme trans-Neptunian objects

[edit]

Among the extreme trans-Neptunian objects are high-perihelion objects classified as sednoids, four of which have been confirmed: 90377 Sedna, 2012 VP113, 541132 Leleākūhonua, and 2023 KQ14. They are distant detached objects with perihelia greater than 70 AU. Their high perihelia keep them at a sufficient distance to avoid significant gravitational perturbations from Neptune. Previous explanations for the high perihelion of Sedna include a close encounter with an unknown planet on a distant orbit and a distant encounter with a random star or a member of the Sun's birth cluster that passed near the Solar System.[53][54][55]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b The literature is inconsistent in the use of the phrases "scattered disc" and "Kuiper belt". For some, they are distinct populations; for others, the scattered disk is part of the Kuiper belt, in which case the low-eccentricity population is called the "classical Kuiper belt". Authors may even switch between these two uses in a single publication.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ "Transneptunian object 1994 TG2".

- ^ McFadden, Weissman, & Johnson (2005). Encyclopedia of the Solar System, footnote p. 584

- ^ "List Of Transneptunian Objects". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects". Minor Planet Center. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Johnston's Archive. 7 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: orbital class (TNO)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: orbital class (TNO) and q > 30.1 (au)". Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ C. de la Fuente Marcos; R. de la Fuente Marcos (1 September 2014). "Extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the Kozai mechanism: signalling the presence of trans-Plutonian planets". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 443 (1): L59 – L63. arXiv:1406.0715. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..59D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu084.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris; Goldader, Jeff (20 August 2011). "Thirty-four years after launch, Voyager 2 continues to explore". NASA Spaceflight (nasaspaceflight.com) (Press release).

- ^ Cory Shankman; et al. (10 February 2013). "A Possible Divot in the Size Distribution of the Kuiper Belt's Scattering Objects". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 764 (1): L2. arXiv:1210.4827. Bibcode:2013ApJ...764L...2S. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/764/1/L2. S2CID 118644497.

- ^ Shankman, C.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Gladman, B. J.; Alexandersen, M.; Kaib, N.; Petit, J.-M.; Bannister, M. T.; Chen, Y.-T.; Gwyn, S.; Jakubik, M.; Volk, K. (2016). "OSSOS. II. A Sharp Transition in the Absolute Magnitude Distribution of the Kuiper Belt's Scattering Population". The Astronomical Journal. 150 (2): 31. arXiv:1511.02896. Bibcode:2016AJ....151...31S. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/151/2/31. S2CID 55213074.

- ^ Brett Gladman; et al. (2008). The Solar System Beyond Neptune. p. 43.

- ^ a b Elliot, J. L.; Kern, S. D.; Clancy, K. B.; Gulbis, A. A. S.; Millis, R. L.; Buie, M. W.; Wasserman, L. H.; Chiang, E. I.; Jordan, A. B.; Trilling, D. E.; Meech, K. J. (2005). "The Deep Ecliptic Survey: A Search for Kuiper Belt Objects and Centaurs. II. Dynamical Classification, the Kuiper Belt Plane, and the Core Population". The Astronomical Journal. 129 (2): 1117–1162. Bibcode:2005AJ....129.1117E. doi:10.1086/427395.

- ^ Brown, Michael E.; Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Rabinowitz, David L. (2004). "Discovery of a Candidate Inner Oort Cloud Planetoid" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): 645–649. arXiv:astro-ph/0404456. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..645B. doi:10.1086/422095. S2CID 7738201. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Sheppard, Scott S. (2014). "A Sedna-like body with a perihelion of 80 astronomical units" (PDF). Nature. 507 (7493): 471–474. Bibcode:2014Natur.507..471T. doi:10.1038/nature13156. PMID 24670765. S2CID 4393431. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2014.

- ^ Pfalzner, Susanne; Govind, Amith; Portegies Zwart, Simon (4 September 2024). "Trajectory of the stellar flyby that shaped the outer Solar System". Nature Astronomy. 8 (11): 1380–1386. arXiv:2409.03342. Bibcode:2024NatAs...8.1380P. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02349-x. ISSN 2397-3366.

- ^ a b Peixinho, N.; Doressoundiram, A.; Delsanti, A.; Boehnhardt, H.; Barucci, M. A.; Belskaya, I. (2003). "Reopening the TNOs Color Controversy: Centaurs Bimodality and TNOs Unimodality". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 410 (3): L29 – L32. arXiv:astro-ph/0309428. Bibcode:2003A&A...410L..29P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20031420. S2CID 8515984.

- ^ Hainaut, O. R.; Delsanti, A. C. (2002). "Color of Minor Bodies in the Outer Solar System". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 389 (2): 641–664. Bibcode:2002A&A...389..641H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020431. datasource

- ^ Doressoundiram, A.; Peixinho, N.; de Bergh, C.; Fornasier, S.; Thébault, Ph.; Barucci, M. A.; Veillet, C. (2002). "The color distribution in the Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt". The Astronomical Journal. 124 (4): 2279–2296. arXiv:astro-ph/0206468. Bibcode:2002AJ....124.2279D. doi:10.1086/342447. S2CID 30565926.

- ^ Gulbis, Amanda A. S.; Elliot, J. L.; Kane, Julia F. (2006). "The color of the Kuiper belt Core". Icarus. 183 (1): 168–178. Bibcode:2006Icar..183..168G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.01.021.

- ^ a b Rabinowitz, David L.; Barkume, K. M.; Brown, Michael E.; Roe, H. G.; Schwartz, M.; Tourtellotte, S. W.; Trujillo, C. A. (2006). "Photometric Observations Constraining the Size, Shape, and Albedo of 2003 El61, a Rapidly Rotating, Pluto-Sized Object in the Kuiper Belt". Astrophysical Journal. 639 (2): 1238–1251. arXiv:astro-ph/0509401. Bibcode:2006ApJ...639.1238R. doi:10.1086/499575. S2CID 11484750.

- ^ Fornasier, S.; Dotto, E.; Hainaut, O.; Marzari, F.; Boehnhardt, H.; De Luise, F.; et al. (October 2007). "Visible spectroscopic and photometric survey of Jupiter Trojans: Final results on dynamical families". Icarus. 190 (2): 622–642. arXiv:0704.0350. Bibcode:2007Icar..190..622F. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.033. S2CID 12844258.

- ^ A. Barucci Trans Neptunian Objects’ surface properties, IAU Symposium No. 229, Asteroids, Comets, Meteors, Aug 2005, Rio de Janeiro

- ^ a b c d e Pinilla-Alonso, Noemi; Brunetto, Rosario; De Prá, Mario; Holler, Bryan J.; Hénault, Elsa; Feliciano, Ana Carolina de Souza; Lorenzi, Vania; Pendleton, Yvonne; Cruikshank, Dale P.; Müller, Thomas G.; Stansberry, John; Emery, Joshua P.; Schambeau, Charles; Licandro, Javier; Harvison, Brittany (February 2025). "A JWST/DiSCo-TNOs portrait of the primordial Solar System through its trans-Neptunian objects". Nature Astronomy. 19 (2): 230–244. Bibcode:2025NatAs...9..230P. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02433-2.

- ^ De Prá, Mário N.; Hénault, Elsa; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemí; Holler, Bryan J.; Brunetto, Rosario; Stansberry, John A.; de Souza-Feliciano, Ana Carolina; Carvano, Jorge M.; Harvison, Brittany; Licandro, Javier; Müller, Thomas G.; Peixinho, Nuno; Lorenzi, Vania; Guilbert-Lepoutre, Aurélie; Bannister, Michele T.; Pendleton, Yvonne J.; Cruikshank, Dale P.; Schambeau, Charles A.; McClure, Lucas; Emery, Joshua P. (2024). "Widespread CO2 and CO ices in the trans-Neptunian population revealed by JWST/DiSCo-TNOs". Nature Astronomy. 9 (2): 252–261. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02276-x.

- ^ Hénault, Elsa; Brunetto, Rosario; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemí; Baklouti, Donia; Djouadi, Zahia; Guilbert-Lepoutre, Aurelie; Müller, Thomas G.; Cyran, Sasha; de Souza-Feliciano, Ana Carolina; Holler, Bryan J.; De Prá, Mario N.; Emery, Joshua P.; McClure, Lucas; Schambeau, Charles; Pendleton, Yvonne; Harvison, Brittany; Licandro, Javier; Lorenzi, Vania; Cruikshank, Dale P.; Peixinho, Nuno; Bannister, Michele T.; Stansberry, John (February 2025). "Irradiation origin and stability of CO on trans-Neptunian objects: Laboratory constraints and observational evidence from JWST/DiSCo-TNOs". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 694: A126. Bibcode:2025A&A...694A.126H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202452321.

- ^ Brunetto, Rosario; Hénault, Elsa; Cryan, Sasha; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemí; Emery, Joshua P.; Guilbert-Lepoutre, Aurelie; Holler, Bryan J.; McClure, Lucas; Müller, Thomas G.; Pendleton, Yvonne; de Souza-Feliciano, Ana Carolina; Stansberry, John; Grundy, William; Peixinho, Nuno; Strazzulla, Gianni (March 2025). "Spectral Diversity of DiSCo's TNOs Revealed by JWST: Early Sculpting and Late Irradiation". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 982 (1): L8. Bibcode:2025ApJ...982L...8B. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/adb977.

- ^ Licandro, Javier; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemí; Holler, Bryan J.; De Prá, Mario; Melita, Mario; de Souza Feliciano, Ana Carolina; Brunetto, Rosario; Guilbert-Lepoutre, Aurelie; Hénault, Elsa; Lorenzi, Vania; Stansberry, John; Schambeau, Charles; Harvison, Brittany; Pendleton, Yvonne; Cruikshank, Dale P. (February 2025). "Thermal evolution of trans-Neptunian objects through observations of Centaurs with JWST". Nature Astronomy. 19 (2): 245–251. Bibcode:2025NatAs...9..245L. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02417-2.

- ^ Pinilla-Alonso, Noemi; Licandro, Javier; Brunetto, Rosario; Henault, Elsa; Schambeau, Charles; Guilbert-Lepoutre, Aurelie; Stansberry, John; Wong, Ian; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Holler, Bryan; Emery, Joshua P.; Protopapa, Silvia; Cook, Jason; Hammel, Heide B.; Villanueva, Geronimo L.; Milam, Stefanie N.; Cruikshank, Dale P.; de Souza-Feliciano, Ana C. (December 2024). "Unveiling the ice and gas nature of active centaur (2060) Chiron using the James Webb Space Telescope". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 692: idL11. arXiv:2407.07761. Bibcode:2024A&A...692L..11P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202450124.

- ^ Markwadt, Larissa; Wen Lin, Hsing; Holler, Bryan J; Gerdes, David W.; Adams, Fred C.; Malhotra, Renu; Napier, Kevin J. (2025). "From Colors to Spectra and Back Again: First Near-IR Spectroscopic Survey of Neptunian Trojans". The Planetary Science Journal. 6 (7): id.154. arXiv:2310.03998. Bibcode:2025PSJ.....6..154M. doi:10.3847/PSJ/addecd.

- ^ Holler, BryanJ.; Benecchi, Susan D.; Brunetto, Rosario; Cartwright, Richard; Cook, Jason C.; Emery, Joshua P.; Ieva, Simone; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemí; Protopapa, Silvia; Stansberry, John A.; Wong, Ian; Young, Leslie A.; de Souza Feliciano, Ana C. (2024). "Constraining the origin and dynamical evolution of extreme trans-Neptunian objects through NIR spectroscopy". JWST Proposal GO3: 4665. Bibcode:2024jwst.prop.4665H.

- ^ Xie, Chen; Chen, Christine H.; Lisse, Carey M; Hise, Dean C.; Beck, Tracy; Betti, Sarah K.; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemi; Ingebretsen, Carl; Worthen, Kadin; Gaspar, Andras; Wolf, Schuyler G.; Bolin, Bryce; Pueyo, Lauren; Perrin, Marshall D.; Stansberry, John A.; Leisenring, Jarron M. (May 2025). "Water ice in the debris disk around HD 181327". Nature. 641 (8063): 608–611. arXiv:2505.08863. Bibcode:2025Natur.641..608X. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-08920-4. PMID 40369138.

- ^ Grundy, William M.; Wong, Ian; Glein, Chris R.; Protopapa, Silvia; Holler, Bryan; Cook, Jason C.; Stansberry, John A.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Parker, Alexander; Hammel, Heide B.; Milam, Stefanie N.; Brunetto, R.; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemi; de Souza Feliciano, Ana C.; Emery, Joshua P. (2024). "Measurement of D/H and 13C/12C ratios in methane ice on Eris and Makemake: Evidence for internal activity". Icarus. 411: id. 115923. arXiv:2309.05085. Bibcode:2024Icar..41115923G. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02275-y.

- ^ Emery, Joshua P.; Wong, Ian; Brunetto, Rosario; Cook, Jason. C.; Pinilla-Alonso, Noemí; Stansberry, John A.; Holler, Bryan P.; Grundy, William M.; Protopapa, Silvia; Souza-Feliciano, Ana C.; Fernandez-Valenzuela, Estela; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Hines, Dean C. (May 2024). "A tale of 3 dwarf planets: Ices and organics on Sedna, Gonggong, and Quaoar from JWST spectroscopy". Icarus. 414 116017: id.116017. arXiv:2309.15230. Bibcode:2024Icar..41416017E. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116017.

- ^ "Conversion of Absolute Magnitude to Diameter". Minorplanetcenter.org. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "Evidence for an Extended Scattered Disk?". obs-nice.fr.

- ^ Jewitt, D.; Delsanti, A. (2006). "The Solar System Beyond The Planets" (PDF). Solar System Update : Topical and Timely Reviews in Solar System Sciences (Springer-Praxis ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-26056-1.

- ^ Gomes, Rodney S.; Matese, John J.; Lissauer, Jack J. (2006). "A Distant Planetary-Mass Solar Companion May Have Produced Distant Detached Objects" (PDF). Icarus. 184 (2): 589–601. Bibcode:2006Icar..184..589G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.05.026. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2007.

- ^ Brown, Michael E.; Barkume, Kristina M.; Ragozzine, Darin; Schaller, Emily L. (2007). "A collisional family of icy objects in the Kuiper belt" (PDF). Nature. 446 (7133): 294–296. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..294B. doi:10.1038/nature05619. PMID 17361177. S2CID 4430027.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (11 February 2018). "Dynamically correlated minor bodies in the outer Solar system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 474 (1): 838–846. arXiv:1710.07610. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.474..838D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx2765.

- ^ "MPEC 2005-O42 : 2005 FY9". Minorplanetcenter.org. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "Mystery object in weird orbit beyond Neptune cannot be explained". New Scientist. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (25 March 2015). "NASA New Horizons Mission Page". NASA.

- ^ "New Horizons: News Article?page=20190101". pluto.jhuapl.edu. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "A Survey of Mission Opportunities to Trans-Neptunian Objects". ResearchGate. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Low-Cost Opportunity for Multiple Trans-Neptunian Object Rendezvous and Capture, AAS Paper 17-777.

- ^ a b "AAS 17-777 Low-cost Opportunity for Multiple Trans-Neptunian Object Rendezvous and Orbital Capture". ResearchGate. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Julio A., Fernández (January 2011). "On the Existence of a Distant Solar Companion and its Possible Effects on the Oort Cloud and the Observed Comet Population". The Astrophysical Journal. 726 (1): 33. Bibcode:2011ApJ...726...33F. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/726/1/33. S2CID 121392983.

- ^ Patryk S., Lykawka; Tadashi, Mukai (April 2008). "An Outer Planet Beyond Pluto and the Origin of the Trans-Neptunian Belt Architecture". The Astronomical Journal. 135 (4): 1161–1200. arXiv:0712.2198. Bibcode:2008AJ....135.1161L. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/4/1161. S2CID 118414447.

- ^ Lorenzo, Iorio (August 2013). "Perspectives on effectively constraining the location of a massive trans-Plutonian object with the New Horizons spacecraft: a sensitivity analysis". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 116 (4): 357–366. arXiv:1301.3831. Bibcode:2013CeMDA.116..357I. doi:10.1007/s10569-013-9491-x. S2CID 119219926.

- ^ a b David, Leonard (9 January 2019). "A Wild 'Interstellar Probe' Mission Idea Is Gaining Momentum". Space.com. Retrieved 22 April 2025.

- ^ Bradnt, P.C.; et al. "The Interstellar Probe Mission (Graphic Poster)" (PDF). hou.usra.edu. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Wall, Mike (24 August 2011). "A Conversation With Pluto's Killer: Q & A With Astronomer Mike Brown". Space.com. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Brown, Michael E.; Trujillo, Chadwick; Rabinowitz, David (2004). "Discovery of a Candidate Inner Oort Cloud Planetoid". The Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): 645–649. arXiv:astro-ph/0404456. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..645B. doi:10.1086/422095. S2CID 7738201.

- ^ Brown, Michael E. (28 October 2010). "There's something out there – part 2". Mike Brown's Planets. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

External links

[edit]- Nine planets, University of Arizona

- David Jewitt's Kuiper Belt site

- A list of the estimates of the diameters from johnstonarchive with references to the original papers

Trans-Neptunian object

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

A trans-Neptunian object (TNO) is defined as any minor planet or dwarf planet in the Solar System that orbits the Sun with a semi-major axis greater than 30.1 AU, the average distance of Neptune from the Sun.[8] This criterion places TNOs firmly beyond the orbit of the outermost major planet, distinguishing them from inner Solar System bodies like asteroids in the main belt or those influenced primarily by Jupiter and Saturn. The term encompasses a diverse population of icy, rocky remnants from the early Solar System, preserved in the cold outer reaches where dynamical interactions with giant planets are minimal.[9] TNOs are differentiated from related but distinct classes of objects based on orbital characteristics. For instance, centaurs—transitional bodies with perihelia inside Neptune's orbit and semi-major axes typically between 5 and 30 AU—are not classified as core TNOs, though some originate from scattered TNO populations before migrating inward.[10] Similarly, Oort cloud comets, which reside at distances exceeding 2,000 AU in a spherical halo, are dynamically separate and not included in the TNO category, despite their shared icy composition and distant orbits.[10] The TNO population broadly includes the Kuiper belt, a disk-shaped region extending from about 30 to 50 AU, but extends further to encompass scattered disk objects (with perihelia beyond 30 AU but high eccentricities) and detached objects in more stable, distant orbits.[2] As of 2025, more than 5,000 TNOs have been identified through systematic surveys, yet this represents only a tiny fraction of the estimated billions of smaller objects (down to kilometer sizes) thought to populate the region based on observational constraints and dynamical models.[3]Population and Distribution

Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) form a vast population in the outer Solar System, with current observations identifying over 5,000 such bodies, though estimates indicate a much larger total exceeding 100,000 objects with diameters greater than 100 km. Surveys like the Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS), which discovered 838 TNOs and nearly doubled the known nonresonant Kuiper Belt inventory, and the Dark Energy Survey (DES), which identified 812 TNOs including 458 new ones, provide critical constraints on these estimates by characterizing detection biases and extrapolating to the full population.[11][12] These efforts reveal that while hundreds of TNOs larger than 100 km have been directly observed, the intrinsic population is dominated by smaller, fainter objects, with the total mass in the Kuiper Belt estimated at around 0.01 to 0.1 Earth masses.[13] The size-frequency distribution of TNOs follows a power-law form, where the cumulative number of objects with diameter greater than is , with to 5 for bodies larger than a few tens of kilometers.[13] A notable break occurs at diameters around 50 km, marking the transition from a regime dominated by accretion processes for larger bodies to one shaped by collisional evolution for smaller ones, where frequent impacts grind down objects and steepen the distribution slope. This break reflects the primordial formation history combined with billions of years of dynamical and collisional processing, with the power-law index indicating a relatively shallow slope for large TNOs (implying fewer giants) and a steeper profile below the break consistent with equilibrium in a collisional cascade.[14] Spatially, TNOs occupy a broad, disk-like structure aligned with the ecliptic plane, with the densest concentration in the Kuiper Belt core spanning semimajor axes from 30 to 50 AU.[15] Beyond this, scattered and detached populations extend to semimajor axes of 100 AU and farther, forming a more diffuse halo influenced by interactions with Neptune.[10] The radial density profile decreases sharply beyond 50 AU, consistent with models of planet migration that depleted the outer disk, leaving a cutoff in object density around 45–50 AU.[16] In the extreme outer regions, where semimajor axes exceed 150 AU, observed clustering in orbital elements such as longitude of perihelion among extreme TNOs hints at dynamical sculpting by unseen gravitational perturbers, though the overall population remains sparse and unevenly sampled.[17]History

Early Hypotheses

In the early 19th century, astronomers observed discrepancies in the predicted orbit of Uranus, which had been discovered in 1781 and was expected to follow a regular path based on Newtonian gravity. These anomalies, including slight deviations in Uranus's position, suggested the influence of an unseen massive body exerting gravitational perturbations. Independently, British mathematician John Couch Adams calculated the likely position of this perturbing body in 1845, predicting it to lie beyond Uranus. Similarly, French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier arrived at nearly identical conclusions through his own mathematical analysis in 1846, proposing coordinates for the hypothetical planet that closely matched Adams's work. These predictions culminated in the telescopic confirmation of Neptune on September 23, 1846, by Johann Galle at the Berlin Observatory, using Le Verrier's coordinates, marking the first planet discovered through gravitational theory rather than direct observation.[18][19] Following Neptune's discovery, astronomers re-examined the orbital data for both Uranus and the newly found planet, revealing persistent irregularities that could not be fully accounted for by known bodies. These residual perturbations implied the possible existence of yet another massive object farther out in the solar system. In 1906, American astronomer Percival Lowell formalized this idea in his "Planet X" hypothesis, arguing that a trans-Neptunian planet with significant mass—estimated at several times Earth's—could explain the observed discrepancies in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune. Lowell initiated a systematic search for this body from his observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, calculating its potential orbit to lie far beyond Neptune, though his efforts did not yield a discovery during his lifetime.[20][21] By the mid-20th century, theoretical models of solar system formation began to incorporate ideas of extended populations beyond Neptune. In 1951, Dutch-American astronomer Gerard Kuiper proposed the existence of a vast reservoir of icy planetesimals just outside Neptune's orbit, serving as the source for short-period comets observed in the inner solar system. Kuiper envisioned this disk-like structure as remnants from the solar system's primordial accretion phase, where leftover material failed to coalesce into a planet due to insufficient density, instead forming a belt of small, comet-like bodies. This hypothesis, detailed in his paper "On the Origin of the Solar System," provided a dynamical explanation for comet origins without invoking a single large perturber, predating any direct observational evidence by decades.[22][23]Discovery of Pluto

The search for a trans-Neptunian planet, dubbed Planet X, originated from Percival Lowell's 1906 hypothesis that an unseen body was perturbing the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, prompting systematic photographic surveys at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona.[24] In 1929, 23-year-old assistant astronomer Clyde Tombaugh joined the effort, using a 13-inch astrograph telescope to capture paired images of regions in Gemini and Taurus predicted by Lowell's calculations.[25] On February 18, 1930, while examining plates taken on January 23 and January 29, Tombaugh identified a faint moving object against the stars, confirming its position with additional exposures; at the time of imaging, the object was approximately 39.5 AU from the Sun.[24][26] The discovery was announced on March 13, 1930, to the International Astronomical Union and the American Astronomical Society, with the object initially hailed as Planet X due to its location aligning with Lowell's predictions.[24] However, early mass estimates, derived from its minimal gravitational influence on other bodies, revealed Pluto to be far too small—approximately 0.002 Earth masses—to account for the observed perturbations in Uranus and Neptune's orbits, which were later attributed to observational errors rather than an external planet.[26] Pluto's highly eccentric orbit, with an eccentricity of 0.25, further distinguished it, allowing it to approach as close as 29.7 AU to the Sun at perihelion while receding to 49.3 AU at aphelion, a trait that complicated its interpretation as a traditional planet.[27] By the early 1990s, the detection of other trans-Neptunian objects, such as 1992 QB1, demonstrated that Pluto belonged to a vast population in the Kuiper Belt, leading to its reclassification as the largest known member of this disk rather than a solitary perturber.[28] This shift underscored Pluto's role as a prototype for the region's icy bodies, transforming its status from a presumed ninth planet to an archetypal trans-Neptunian object.[10]Modern Discoveries

The modern era of Trans-Neptunian object (TNO) discoveries began in 1992 with the detection of 1992 QB₁ (later designated 15760 Albion) by astronomers David Jewitt and Jane Luu using the University of Hawaii's 2.2-meter telescope on Mauna Kea.[29] This faint object, with a magnitude of about 23 and an orbit beyond Neptune, provided the first direct evidence for the Kuiper belt, a predicted population of icy bodies hypothesized decades earlier. Their systematic search, spanning years of observations, marked a shift from serendipitous finds to targeted surveys.[30] Advancements in charge-coupled device (CCD) imaging and wide-field telescopes revolutionized TNO detection by enabling deeper, larger-scale sky surveys that capture faint, slow-moving objects.[31] These technologies increased the annual discovery rate to approximately 100 new TNOs in recent years, up from just a handful before 1992.[32] Instruments like the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope's MegaCam and Subaru's Hyper Suprime-Cam have been pivotal, allowing for efficient monitoring of vast ecliptic regions.[33] Dedicated survey programs have since cataloged thousands of TNOs, providing insights into the outer Solar System's structure. The Deep Ecliptic Survey (DES), conducted from 1998 to 2005 using telescopes at Cerro Tololo and Kitt Peak, discovered over 500 TNOs and identified key dynamical classes, including the first detached objects unaffected by Neptune.[34] The Outer Solar System Origins Survey (OSSOS), operating from 2013 to 2017 on the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, detected 838 TNOs across 168 square degrees, enabling unbiased studies of orbital distributions.[11] By 2025, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), which began full operations in early 2025, had already contributed dozens of discoveries in its initial months, with projections for tens of thousands more over the decade; combined efforts have identified over 5,000 TNOs to date.[7][3] Recent findings highlight the diversity of TNO orbits and the role of advanced observatories. In July 2025, the Subaru Telescope's FOSSIL survey announced 2023 KQ₁₄ (nicknamed Ammonite), a Sedna-like object with a perihelion of 66 AU, semi-major axis of 252 AU, and inclination of 11°, observed near its closest approach at 71 AU.[6] This distant body, potentially a dwarf planet candidate, underscores the existence of an extended scattered population. The discovery of 2017 OF₂₀₁ was announced in May 2025, with follow-up analysis in September 2025 confirming it as a ~700 km-diameter TNO on an extreme ~26,000-year orbit, with perihelion of 44.9 AU and aphelion reaching 1,713 AU, challenging models of outer Solar System formation.[35][36] Additionally, James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations in early 2025 of multiple TNOs, including Pluto and Eris, revealed pristine, ancient surfaces dominated by water ice, CO₂, and complex organics, indicating minimal alteration since the Solar System's formation ~4.6 billion years ago.[3] These JWST-assisted characterizations, using near-infrared spectroscopy, have detected ices on over 50 mid-sized TNOs, linking their compositions to primordial conditions.[37]Classification

Kuiper Belt Objects

Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) represent the primary stable population of trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), characterized by semi-major axes ranging from 30 to 50 AU and low orbital eccentricities, generally less than 0.2. These objects avoid close encounters with Neptune due to their non-crossing orbits and are subdivided into classical and resonant subpopulations based on their dynamical properties. The classical KBOs form a disk-like structure analogous to the predicted remnants of the early Solar System's planetesimal disk, while the resonant KBOs are locked in stable orbital configurations with Neptune. The classical KBOs are further divided into "cold" and "hot" populations distinguished by their orbital inclinations. Cold classical KBOs exhibit low inclinations, typically below 5°, along with very low eccentricities (often <0.08), resulting in nearly circular and coplanar orbits that preserve the dynamical coldness of the primordial planetesimal disk from the Solar Nebula. This subpopulation is thought to have remained largely unperturbed since formation, offering insights into the initial conditions of the outer Solar System. In contrast, hot classical KBOs have higher inclinations, ranging from about 5° to 15° or more, with slightly elevated eccentricities, suggesting they may have been dynamically excited by early planetary migrations or scattering events. Classical KBOs collectively account for approximately two-thirds of all known KBOs.[38] Resonant KBOs occupy mean-motion resonances with Neptune, where the orbital periods of the TNO and Neptune are in simple integer ratios, ensuring long-term stability by preventing disruptive close approaches. The 3:2 resonance, known as the plutino population, is the most populous, with objects completing two orbits for every three of Neptune; Pluto is the prototype, and estimates suggest around 10,000–20,000 objects with absolute magnitudes brighter than H=9 in this group. The 2:1 resonance, or twotino population, features objects that complete one orbit for every two of Neptune, with comparable estimated numbers to the plutinos. These resonances, along with others like 5:2 and 3:1, trap TNOs in protective configurations that have endured for billions of years.[39] The classical and resonant subpopulations together comprise about 70% of known TNOs, underscoring the Kuiper Belt's role as the dominant reservoir of these icy bodies. The dynamically cold classical population, in particular, is widely regarded as a relic that retains the compositional and structural signatures of the primordial disk, minimally altered by subsequent dynamical processes.[40]Scattered and Detached Objects

Scattered disk objects (SDOs) represent a dynamically perturbed population of trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) with orbits characterized by perihelion distances greater than 30 AU, semi-major axes exceeding 50 AU, and eccentricities typically above 0.2.[41] These parameters distinguish SDOs from the more stable classical and resonant TNOs in the inner Kuiper belt, as their high eccentricities result in elongated orbits that bring them closer to Neptune at perihelion but extend far beyond its influence at aphelion.[42] The scattered disk extends outward to nearly 1000 AU, though most known members reside between 30 and 100 AU, forming a sparse, extended structure overlapping the outer Kuiper belt.[10] The origins of SDOs trace back to gravitational scattering by Neptune during the planet's outward migration in the early Solar System, a process that implanted primordial planetesimals from the proto-Kuiper belt onto these unstable trajectories.[43] Over billions of years, ongoing perturbations from Neptune cause many SDOs to evolve further, either being ejected from the Solar System, captured into resonances, or transitioning to centaur orbits upon crossing inward of 30 AU.[44] A prominent example is the dwarf planet Eris, which exemplifies the class with its high eccentricity and distant aphelion.[42] Detached objects form another perturbed TNO class, defined by semi-major axes greater than 50 AU and perihelion distances exceeding 40 AU, ensuring minimal interactions with Neptune and thus dynamical isolation from the scattered disk.[45] Unlike SDOs, these objects occupy an intermediate zone where perihelia are too distant for frequent scattering (typically q > 36–40 AU), often accompanied by moderate to high inclinations greater than 10°.[46] Their orbits exhibit stability over gigayears due to the lack of close planetary encounters, contrasting the chaotic evolution of SDOs.[45] The formation of detached objects is attributed to early giant planet migration, particularly during the Nice model phase, where scattering events among Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune raised perihelia of planetesimals without ongoing Neptune perturbations.[46] This mechanism suggests they preserve signatures of the primordial disk beyond the classical belt, potentially including a subset with even more extreme perihelia.[45] Scattered and detached objects collectively comprise approximately 8–10% of the known TNO population among the roughly 4,000 multi-opposition objects cataloged as of 2025.[47] Recent classifications in 2024 have employed machine learning algorithms, such as gradient boosting classifiers trained on 10-Myr orbital integrations, to dynamically group TNOs with over 98% accuracy, refining boundaries between these classes and revealing subtle overlaps in their distributions.[48]Physical Properties

Size and Shape

Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) exhibit a wide range of sizes, from sub-kilometer particles to dwarf planets exceeding 2000 km in diameter. Determining these sizes relies primarily on two key observational techniques: stellar occultations and thermal radiometry. Stellar occultations occur when a TNO passes in front of a background star, allowing the timing and duration of the star's disappearance from multiple ground-based sites to yield precise measurements of the object's silhouette diameter and shape, often with kilometric accuracy. For instance, a multi-chord stellar occultation of the dwarf planet Eris in 2010 provided a diameter of 2326 ± 12 km, confirming its nearly spherical profile. This method is particularly effective for larger TNOs but requires precise predictions and favorable alignments, limiting its application to sporadic events. Thermal radiometry complements occultations by measuring the infrared emission from a TNO's sun-heated surface, enabling size estimates through models of thermal equilibrium that relate flux to diameter and albedo. Facilities like the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have detected thermal signatures from TNOs larger than about 100 km, even at distances of tens of AU. For example, ALMA observations of the TNO 2013 FY27 yielded a diameter of approximately 765 km by combining thermal flux data with optical brightness.[49] These measurements are crucial for faint or distant objects where occultations are impractical, though they assume surface properties like emissivity and beaming effects from rotation and roughness. The size distribution of TNOs follows a power-law form with a notable break around 50-100 km, separating a steeper slope for smaller objects (down to sub-kilometer scales) from a shallower one for larger bodies, reflecting collisional evolution in the Kuiper Belt. Among binaries, which comprise about 10-15% of TNOs, the distribution appears bimodal, with peaks in the 100-200 km range for equal-mass pairs and smaller components in unequal systems, suggesting formation mechanisms favoring similar-sized progenitors. Mass estimates for TNOs often derive from satellite orbits using Kepler's laws, providing dynamical constraints on total system mass. The Pluto-Charon binary, for example, yields a combined mass of (1.457 ± 0.009) × 10^22 kg from Charon's 6.387-day orbit at 19,591 km separation, allowing separation of individual masses when sizes are known.[50] Shapes of TNOs are inferred from occultation chords, lightcurve amplitudes, and thermal models, revealing deviations from sphericity driven by rotation, collisions, or tidal forces. Fast rotators like Haumea, with a period of ~3.9 hours, exhibit oblate or triaxial elongation, approaching rotational breakup and resulting in a projected shape with axes ratios up to 2:1, as seen in multi-chord occultations spanning 2010-2017. Larger dwarf planets, such as Pluto and Eris, maintain near-equilibrium shapes close to oblate spheroids due to self-gravity dominating over rotation, with polar flattening less than 1% for Pluto's 6.4-day period. These shapes inform mass-density relations, though detailed density requires integration with compositional data.Composition and Density

Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) primarily consist of water ice as the dominant surface and subsurface material, often mixed with rock and amorphous carbon, reflecting their formation in the cold outer Solar System. Spectroscopic observations indicate that approximately 86% of TNOs exhibit signatures of water ice absorption features in the near-infrared, confirming its prevalence across the population. This water ice can exist in both crystalline and amorphous forms, with the latter suggesting low-temperature accretion environments.[4] On larger TNOs, particularly dwarf planets like Pluto, Eris, and Haumea, more volatile ices such as methane, nitrogen, and carbon monoxide are present, either as surface frost or trapped in the interior. These volatiles are detected through their distinct spectral bands; for instance, Pluto's surface shows nitrogen and methane ices, with carbon monoxide also identified via near-infrared spectroscopy. These materials likely originated from the initial protoplanetary disk and have been retained due to the low temperatures beyond Neptune, though they can migrate seasonally via sublimation.[51][52] Organic compounds on TNO surfaces arise largely from the irradiation of ices by cosmic rays and ultraviolet photons over billions of years, producing complex molecules like tholins, methanol derivatives, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Laboratory simulations demonstrate that ion irradiation of water-methane mixtures generates these reddish, refractory organics, which alter the albedo and spectral properties of TNOs. This process is particularly evident on "ultra-red" TNOs, where irradiation products dominate the surface composition.[37][53] Bulk densities of TNOs range from about 0.5 to 2.5 g/cm³, with lower values indicating highly porous, undifferentiated structures and higher values suggesting compaction or internal differentiation. Small TNOs, typically under 400 km in diameter, often have densities below 1.0 g/cm³ due to macroporosity from rubble-pile-like interiors formed during low-velocity collisions. In contrast, larger bodies show densities approaching 2.0 g/cm³ or more, implying denser rock-ice mixtures.[54] For example, Pluto's density is 1.854 ± 0.006 g/cm³, derived from New Horizons measurements of its mass and volume, indicating a differentiated interior with a rocky core surrounded by ice layers. Sedna, a detached TNO, has an estimated density around 2.0 g/cm³ assuming similarity to Pluto, though direct measurements are lacking due to no known satellites. These variations highlight how size and formation history influence internal structure.[51][56] Evidence for differentiation includes cryovolcanism on Pluto, where nitrogen-rich lavas have resurfaced regions like the Vastitas Borealis, driven by internal heat from radioactive decay and tidal forces with Charon. This process suggests subsurface oceans or mobilized volatiles, as seen in topographic domes and flow features mapped by New Horizons. Binary TNOs provide additional insights, as mutual tidal interactions during formation and evolution reshape components, allowing density estimates from orbital parameters; for instance, systems like (47171) Lempo show densities around 1.2 g/cm³, with tides promoting spin synchronization and potentially reducing porosity over time.[57][58]Colors and Spectra

Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) exhibit a wide range of surface colors, quantified through photometric color indices such as B-R, which typically span from approximately 0.5 (neutral colors) to 1.5 or greater (very red colors). This diversity reflects variations in surface composition and processing, with observations revealing a bimodal distribution in color space. The blue-grey population, often denoted as BB (blue-blue), corresponds to fresher surfaces dominated by unprocessed ices, while the red population, known as RR (red-red), is characterized by irradiated organic materials like tholins formed through cosmic ray bombardment over billions of years. Spectroscopically, TNOs display distinct near-infrared features that provide insights into their surface chemistry. Small TNOs frequently show flat, featureless spectra, indicative of complex, processed mixtures lacking prominent absorptions. In contrast, larger or less altered objects often exhibit water ice absorption bands at 1.5 μm and 2.0 μm, signaling the presence of crystalline or amorphous water ice on their surfaces. Recent James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations, conducted as part of the DiSCo-TNOs program, have analyzed spectra from 59 TNOs and Centaurs, revealing ancient surfaces heavily processed by radiation and impacts, with evidence of organic refractories and ices that preserve signatures from the early solar system. These include detections of CO_2 ice on approximately 90% and CO on about 50% of the observed TNOs, indicating widespread volatile retention.[59][60][61] TNOs are classified into taxonomic groups based on their visible and near-infrared colors: RR for very red objects, IR for intermediate red, and BB for blue-grey. These classes correlate with dynamical populations; for instance, objects in the scattered disk tend to be redder (favoring RR and IR), likely due to greater exposure to radiation during their dynamical scattering from closer orbits. Such correlations highlight how orbital history influences surface evolution, with colder, more stable populations like cold classical TNOs showing a higher proportion of BB types.[59]Orbital Dynamics

Resonances and Stability

Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) often occupy mean-motion resonances with Neptune, where the orbital periods of the TNO and Neptune are in simple integer ratios, such as 2:1, 3:2, and 5:2. These resonances create libration zones in which TNOs oscillate around stable points, shielding them from close encounters with Neptune and thereby enhancing long-term orbital stability. For instance, the 3:2 resonance hosts Pluto and its plutinos, while the 2:1 resonance contains twotinos like (119979) 2002 WC19.[62] The stability of these resonant populations draws an analogy to the Kirkwood gaps in the asteroid belt, where Jupiter's resonances clear out unstable orbits, leaving protected zones for survivors. In the TNO context, simulations from the Nice model demonstrate that during Neptune's outward migration in the early Solar System, TNOs were captured into these resonances, preserving a subset of the primordial disk against scattering. This capture mechanism explains the observed clustering of TNOs in specific resonant families. Higher-order resonances, such as the 10:1, have also been identified, with the discovery of 2020 VN40 in July 2025 marking the first confirmed object in this distant resonance at approximately 100 AU. This object exhibits short-term stability in libration but is not stable over gigayear timescales, suggesting temporary capture during Neptune's migration and extending our understanding of resonant sculpting in the outer Solar System.[63] Approximately 10% of known TNOs reside in these Neptune resonances, with the majority in the classical belt being non-resonant, though resonant objects exhibit lower chaotic diffusion rates over gigayear timescales compared to scattered populations. Long-term numerical integrations indicate that resonant TNOs maintain semi-major axes with variations of less than 0.1 AU over 4.5 billion years, underscoring their role in delineating stable regions of the outer Solar System.Extreme Orbits

Extreme trans-Neptunian objects (ETNOs) exhibit highly eccentric orbits with perihelion distances typically exceeding 50 AU, placing them beyond the gravitational influence of Neptune and rendering them dynamically detached from the inner Solar System. These orbits often feature semi-major axes greater than 200 AU and aphelia extending hundreds of AU, with eccentricities approaching 0.9, resulting in orbital periods spanning thousands to tens of thousands of years. Such configurations suggest these bodies populate an inner region of the Oort cloud, a hypothetical reservoir of icy planetesimals perturbed into distant trajectories during the early Solar System's formation.[6] Sedna-like objects represent the archetype of these extreme orbits, characterized by perihelia greater than 50 AU and aphelia exceeding 200 AU, isolating them from planetary perturbations. The prototype, Sedna (90377 Sedna), discovered in 2003, has a perihelion of 76 AU, a semi-major axis of 507 AU, and an aphelion of 937 AU, yielding an orbital period of approximately 11,400 years. More recent examples include 2012 VP113 with a perihelion of 80 AU and semi-major axis of 261 AU, and the 2025 discovery of 2023 KQ14 (nicknamed Ammonite), which boasts a perihelion of 66 AU, semi-major axis of 252 AU, and aphelion around 438 AU. These objects are considered candidates for the inner Oort cloud due to their detachment from the Kuiper belt and scattered disk, providing clues to the primordial architecture of the outer Solar System.[6] A notable feature among some ETNOs is the apparent clustering of orbital elements, particularly the longitude of the ascending node (Ω) and argument of perihelion (ω), for objects with eccentricities between 0.3 and 0.9 and inclinations of 15° to 30°. This alignment, observed in a subset of ETNOs with semi-major axes exceeding 250 AU, has been interpreted as evidence for an undiscovered massive planet, dubbed Planet Nine, with a mass of 5 to 10 Earth masses orbiting at 400 to 800 AU. The gravitational shepherding by such a planet could sustain this clustering over billions of years, countering the diffusive effects of galactic tides and passing stars. The original hypothesis, proposed in 2016, relied on simulations showing that Planet Nine's influence naturally reproduces the observed orbital configurations.[64] Dynamical models attribute the origins of these extreme orbits to scattering events in the early Solar System, including interactions with unseen giant planets or close encounters with passing stars. For Sedna-like objects, simulations indicate that a stellar flyby during the Sun's birth cluster could have elevated perihelia beyond 50 AU while preserving high eccentricities, with probabilities of such events around 20-30% for solar-type stars. Alternatively, perturbations from a Planet Nine-mass object could detach inner Oort cloud bodies, implanting them into stable, distant orbits. Recent analyses of Ammonite suggest it and other Sedna-like objects may have originated from a primordial cluster perturbed around 4.2 billion years ago, potentially by giant planet migration or external perturbations.[65][66] Discoveries in 2025 have introduced challenges to the Planet Nine hypothesis through ETNOs exhibiting non-clustered orbits. The object 2017 OF201, announced as a dwarf planet candidate with a diameter of 500-900 km and an orbital period of about 25,000 years, has an extremely wide orbit extending to the Oort cloud but with an argument of periapsis and ascending node that deviate from the predicted clustering. Similarly, Ammonite's orbital parameters do not align with the expected alignments under Planet Nine's influence, suggesting alternative formation mechanisms or observational biases may explain the original clustering. These findings imply that while Planet Nine remains a viable explanation for some ETNOs, broader dynamical processes like multiple stellar encounters could account for the population's diversity without invoking a single distant perturber.[35][6]Notable Objects

Dwarf Planets

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) defines a dwarf planet as a celestial body that orbits the Sun, has sufficient mass to assume a nearly round shape due to hydrostatic equilibrium under its own gravity, has not cleared the neighborhood around its orbit, and is not a satellite.[67] This classification distinguishes dwarf planets from full planets while recognizing their rounded forms, a key criterion applied to trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). Among TNOs, the IAU officially recognizes four dwarf planets: Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake.[68] Additionally, 225088 Gonggong and the recently discovered 2017 OF201 (~700 km diameter) are widely considered dwarf planet candidates due to their estimated sizes and shapes, though they await formal IAU designation.[69] Pluto, the archetypal TNO dwarf planet, has an equatorial diameter of approximately 2,377 kilometers, making it the largest known in this category.[26] It possesses five moons—Charon, Nix, Hydra, Kerberos, and Styx—with Charon being the largest at about half Pluto's diameter, forming a binary-like system.[26] Pluto maintains a thin, tenuous atmosphere composed mainly of molecular nitrogen, with traces of methane and carbon monoxide, which seasonally expands and collapses as it orbits.[26] The 2015 New Horizons flyby revealed diverse geology, including water-ice mountains up to 3 kilometers high, vast nitrogen-ice plains with convective resurfacing, and eroded craters, indicating active processes despite its frigid surface temperatures around 40 kelvins.[70] Eris, residing in the scattered disc, has a diameter of about 2,326 kilometers, slightly smaller than Pluto but more massive at roughly 27% greater than Pluto's mass due to its higher density.[71] It has one known moon, Dysnomia, which orbits at a distance of approximately 37,000 kilometers and helps constrain Eris's mass through gravitational effects.[72] Eris follows a highly eccentric orbit with an eccentricity of 0.44, ranging from 37.8 AU at perihelion to 97.6 AU at aphelion, taking 557 years to complete one revolution.[73] Haumea, another scattered disc object, exhibits an elongated, triaxial shape due to its exceptionally rapid rotation period of about 3.9 hours, the fastest among dwarf planets, resulting in dimensions of approximately 2,320 × 1,704 × 1,138 kilometers (mean diameter ~1,560 kilometers).[74] This rapid spin, likely from a past collision, gives it a density of 2.6 g/cm³, higher than most TNOs, and it has two small moons, Hi'iaka and Namaka, which orbit in the equatorial plane.[75] Its surface is dominated by crystalline water ice, covering about 75% and suggesting recent geological activity or resurfacing. Makemake, a classical Kuiper Belt object, has a diameter of approximately 1,430 kilometers, making it the second-largest Kuiper Belt dwarf planet after Pluto.[76] It features a bright, reddish surface rich in frozen methane, ethane, and nitrogen ices, with a high albedo of about 0.8 due to fresh frost layers that give it a mottled appearance.[76] Makemake has one known moon, S/2015 (136472) 1, estimated at 175 kilometers in diameter, orbiting at around 21,000 kilometers.[77] Its orbit has a low eccentricity of 0.16 and takes 306 years, placing it among the more stable TNOs.[76] Gonggong, a scattered disc TNO discovered in 2007, is a strong dwarf planet candidate with an estimated diameter of 1,230 kilometers, sufficient for hydrostatic equilibrium based on its brightness and thermal models. It has a single known moon, Xiangliu, estimated at approximately 100-200 kilometers in diameter, and a reddish color indicative of complex organics on its icy surface. With an orbital eccentricity of 0.34 and a period of 553 years, Gonggong's status hinges on further confirmation of its rounded shape, but astronomers like Mike Brown argue it qualifies due to its size exceeding 900 kilometers.Other Prominent TNOs

Beyond the dwarf planets, several trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) stand out due to their size, binary nature, or extreme orbital parameters, providing key insights into the outer Solar System's formation and dynamics. Approximately 10-15% of TNOs are binaries, a fraction that is notably higher than in inner Solar System populations and particularly useful for determining individual masses and densities through mutual orbital analysis.[78] These systems, often involving near-equal-mass components, likely formed through gravitational collapse of pebble clouds in the protoplanetary disk, and examples include the contact binary (58534) 1997 CQ29, discovered via Hubble Space Telescope imaging, which consists of two lobes approximately 100 km and 70 km in diameter orbiting at a separation of about 5 km.[79] One of the largest non-dwarf TNOs is (50000) Quaoar, a classical Kuiper Belt object with an estimated diameter of 1110 km, making it roughly half the size of Pluto.[80] Quaoar is orbited by a small moon, Weywot, with a diameter of about 170 km, discovered in 2007 and located at an average distance of 14,500 km from the primary.[81] Observations suggest Quaoar hosts a dense ring system at approximately 4050 km from its center, unusually far beyond the Roche limit, potentially sustained by cryovolcanic activity that ejects material from its interior, as evidenced by surface detections of crystalline water ice and ammonia hydrates indicating recent resurfacing.[80][82] Quaoar's orbit has a perihelion of 41.6 AU, placing it in a relatively stable classical population with low eccentricity.[83] Another significant binary system is (90482) Orcus, a plutino with a diameter of approximately 870-960 km, locked in a 2:3 mean-motion resonance with Neptune, completing two orbits for every three of the planet.[84] Orcus's moon, Vanth, has a diameter of about 443 km—roughly half that of the primary—and orbits at around 9000 km, comprising a substantial fraction of the system's total mass and enabling precise density estimates of 1.5-1.7 g/cm³ for both components.[85] Spectrally, Orcus exhibits neutral colors dominated by water ice absorption features, with Vanth appearing slightly redder in visible and near-infrared wavelengths, though uncertainties in albedo limit firm compositional distinctions.[86] Among the most extreme TNOs are those with highly detached orbits, such as (90377) Sedna, which has a perihelion distance of 76 AU, far beyond Neptune's influence and suggesting origins perturbed by a passing star or undiscovered massive body in the early Solar System.[87] Similarly, (2018 VG18), nicknamed Farout, was discovered at 120 AU and follows an elongated orbit with a perihelion of 39 AU, marking it as one of the most distant observed TNOs at discovery and highlighting gaps in our understanding of scattered disk populations.[88] More recently, the sednoid (2023 KQ14), dubbed Ammonite, was identified with a semi-major axis of 252 AU and perihelion of 66 AU, its parameters challenging models of outer Solar System sculpting and potentially linking to hypothetical Planet Nine influences.[6] These objects underscore the diverse dynamical histories within the trans-Neptunian region.Exploration

Spacecraft Missions