Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polyploidy

View on Wikipedia

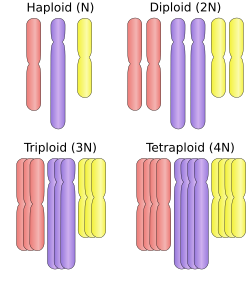

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than two paired sets of (homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two complete sets of chromosomes, one from each of two parents; each set contains the same number of chromosomes, and the chromosomes are joined in pairs of homologous chromosomes. However, some organisms are polyploid. Polyploidy is especially common in plants. Most eukaryotes have diploid somatic cells, but produce haploid gametes (eggs and sperm) by meiosis. A monoploid has only one set of chromosomes, and the term is usually only applied to cells or organisms that are normally diploid. Males of bees and other Hymenoptera, for example, are monoploid. Unlike animals, plants and multicellular algae have life cycles with two alternating multicellular generations. The gametophyte generation is haploid, and produces gametes by mitosis; the sporophyte generation is diploid and produces spores by meiosis.

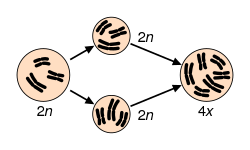

Polyploidy is the result of whole-genome duplication during the evolution of species. It may occur due to abnormal cell division, either during mitosis, or more commonly from the failure of chromosomes to separate during meiosis or from the fertilization of an egg by more than one sperm.[1] In addition, it can be induced in plants and cell cultures by some chemicals: the best known is colchicine, which can result in chromosome doubling, though its use may have other less obvious consequences as well. Oryzalin will also double the existing chromosome content.

Among mammals, a high frequency of polyploid cells is found in organs such as the brain, liver, heart, and bone marrow.[2] It also occurs in the somatic cells of other animals, such as goldfish,[3] salmon, and salamanders. It is common among ferns and flowering plants (see Hibiscus rosa-sinensis), including both wild and cultivated species. Wheat, for example, after millennia of hybridization and modification by humans, has strains that are diploid (two sets of chromosomes), tetraploid (four sets of chromosomes) with the common name of durum or macaroni wheat, and hexaploid (six sets of chromosomes) with the common name of bread wheat. Many agriculturally important plants of the genus Brassica are also tetraploids. Sugarcane can have ploidy levels higher than octaploid.[4]

Polyploidization can be a mechanism of sympatric speciation because polyploids are usually unable to interbreed with their diploid ancestors. An example is the plant Erythranthe peregrina. Sequencing confirmed that this species originated from E. × robertsii, a sterile triploid hybrid between E. guttata and E. lutea, both of which have been introduced and naturalised in the United Kingdom. New populations of E. peregrina arose on the Scottish mainland and the Orkney Islands via genome duplication from local populations of E. × robertsii.[5] Because of a rare genetic mutation, E. peregrina is not sterile.[6]

On the other hand, polyploidization can also be a mechanism for a kind of 'reverse speciation',[7] whereby gene flow is enabled following the polyploidy event, even between lineages that previously experienced no gene flow as diploids. This has been detailed at the genomic level in Arabidopsis arenosa and Arabidopsis lyrata.[8] Each of these species experienced independent autopolyploidy events (within-species polyploidy, described below), which then enabled subsequent interspecies gene flow of adaptive alleles, in this case stabilising each young polyploid lineage.[9] Such polyploidy-enabled adaptive introgression may allow polyploids at act as 'allelic sponges', whereby they accumulate cryptic genomic variation that may be recruited upon encountering later environmental challenges.[7]

Terminology

[edit]Types

[edit]

Polyploid types are labeled according to the number of chromosome sets in the nucleus. The letter x is used to represent the number of chromosomes in a single set:

- haploid (one set; 1x), for example male European fire ants

- diploid (two sets; 2x), for example humans

- triploid (three sets; 3x), for example sterile saffron crocus, or seedless watermelons, also common in the phylum Tardigrada[10]

- tetraploid (four sets; 4x), for example, Plains viscacha rat, Salmonidae fish,[11] the cotton Gossypium hirsutum[12]

- pentaploid (five sets; 5x), for example Kenai Birch (Betula kenaica)

- hexaploid (six sets; 6x), for example some species of wheat,[13] kiwifruit[14]

- heptaploid or septaploid (seven sets; 7x), for example some cultured Siberian sturgeon[15]

- octaploid or octoploid, (eight sets; 8x), for example Acipenser (genus of sturgeon fish), dahlias

- decaploid (ten sets; 10x), for example certain strawberries

- hendecaploid or undecaploid (eleven sets; 11x), for example some Lepidium [16] species and rose cultivars

- dodecaploid or duodecaploid (twelve sets; 12x), for example the plants Celosia argentea and Spartina anglica [17] or the amphibian Xenopus ruwenzoriensis.

- tetratetracontaploid (forty-four sets; 44x), for example black mulberry[18]

Classification

[edit]Autopolyploidy

[edit]Autopolyploids are polyploids with multiple chromosome sets derived from a single taxon.

Two examples of natural autopolyploids are the piggyback plant, Tolmiea menzisii[19] and the white sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanum.[20] Most instances of autopolyploidy result from the fusion of unreduced (2n) gametes, which results in either triploid (n + 2n = 3n) or tetraploid (2n + 2n = 4n) offspring.[21] Triploid offspring are typically sterile (as in the phenomenon of triploid block), but in some cases they may produce high proportions of unreduced gametes and thus aid the formation of tetraploids. This pathway to tetraploidy is referred to as the triploid bridge.[21] Triploids may also persist through asexual reproduction. In fact, stable autotriploidy in plants is often associated with apomictic mating systems.[22] In agricultural systems, autotriploidy can result in seedlessness, as in watermelons and bananas.[23] Triploidy is also utilized in salmon and trout farming to induce sterility.[24][25]

Rarely, autopolyploids arise from spontaneous, somatic genome doubling, which has been observed in apple (Malus domesticus) bud sports.[26] This is also the most common pathway of artificially induced polyploidy, where methods such as protoplast fusion or treatment with colchicine, oryzalin or mitotic inhibitors are used to disrupt normal mitotic division, which results in the production of polyploid cells. This process can be useful in plant breeding, especially when attempting to introgress germplasm across ploidal levels.[27]

Autopolyploids possess at least three homologous chromosome sets, which can lead to high rates of multivalent pairing during meiosis (particularly in recently formed autopolyploids, also known as neopolyploids) and an associated decrease in fertility due to the production of aneuploid gametes.[28] Natural or artificial selection for fertility can quickly stabilize meiosis in autopolyploids by restoring bivalent pairing during meiosis. Rapid adaptive evolution of the meiotic machinery, resulting in reduced levels of multivalents (and therefore stable autopolyploid meiosis) has been documented in Arabidopsis arenosa[29] and Arabidopsis lyrata,[8] with specific adaptive alleles of these species shared between only the evolved polyploids.[8][30]

The high degree of homology among duplicated chromosomes causes autopolyploids to display polysomic inheritance.[31] This trait is often used as a diagnostic criterion to distinguish autopolyploids from allopolyploids, which commonly display disomic inheritance after they progress past the neopolyploid stage.[32] While most polyploid species are unambiguously characterized as either autopolyploid or allopolyploid, these categories represent the ends of a spectrum of divergence between parental subgenomes. Polyploids that fall between these two extremes, which are often referred to as segmental allopolyploids, may display intermediate levels of polysomic inheritance that vary by locus.[33][34]

About half of all polyploids are thought to be the result of autopolyploidy,[35][36] although many factors make this proportion hard to estimate.[37]

Allopolyploidy

[edit]Allopolyploids or amphipolyploids or heteropolyploids are polyploids with chromosomes derived from two or more diverged taxa.

As in autopolyploidy, this primarily occurs through the fusion of unreduced (2n) gametes, which can take place before or after hybridization. In the former case, unreduced gametes from each diploid taxon – or reduced gametes from two autotetraploid taxa – combine to form allopolyploid offspring. In the latter case, one or more diploid F1 hybrids produce unreduced gametes that fuse to form allopolyploid progeny.[38] Hybridization followed by genome duplication may be a more common path to allopolyploidy because F1 hybrids between taxa often have relatively high rates of unreduced gamete formation – divergence between the genomes of the two taxa result in abnormal pairing between homoeologous chromosomes or nondisjunction during meiosis.[38] In this case, allopolyploidy can actually restore normal, bivalent meiotic pairing by providing each homoeologous chromosome with its own homologue. If divergence between homoeologous chromosomes is even across the two subgenomes, this can theoretically result in rapid restoration of bivalent pairing and disomic inheritance following allopolyploidization. However multivalent pairing is common in many recently formed allopolyploids, so it is likely that the majority of meiotic stabilization occurs gradually through selection.[28][32]

Because pairing between homoeologous chromosomes is rare in established allopolyploids, they may benefit from fixed heterozygosity of homoeologous alleles.[39] In certain cases, such heterozygosity can have beneficial heterotic effects, either in terms of fitness in natural contexts or desirable traits in agricultural contexts. This could partially explain the prevalence of allopolyploidy among crop species. Both bread wheat and triticale are examples of an allopolyploids with six chromosome sets. Cotton, peanut, and quinoa are allotetraploids with multiple origins. In Brassicaceous crops, the Triangle of U describes the relationships between the three common diploid Brassicas (B. oleracea, B. rapa, and B. nigra) and three allotetraploids (B. napus, B. juncea, and B. carinata) derived from hybridization among the diploid species. A similar relationship exists between three diploid species of Tragopogon (T. dubius, T. pratensis, and T. porrifolius) and two allotetraploid species (T. mirus and T. miscellus).[40] Complex patterns of allopolyploid evolution have also been observed in animals, as in the frog genus Xenopus.[41]

Aneuploid

[edit]Organisms in which a particular chromosome, or chromosome segment, is under- or over-represented are said to be aneuploid (from the Greek words meaning "not", "good", and "fold"). Aneuploidy refers to a numerical change in part of the chromosome set, whereas polyploidy refers to a numerical change in the whole set of chromosomes.[42]

Endopolyploidy

[edit]Polyploidy occurs in some tissues of animals that are otherwise diploid, such as human muscle tissues.[43] This is known as endopolyploidy. Species whose cells do not have nuclei, that is, prokaryotes, may be polyploid, as seen in the large bacterium Epulopiscium fishelsoni.[44] Hence ploidy is defined with respect to a cell.

Monoploid

[edit]A monoploid has only one set of chromosomes and the term is usually only applied to cells or organisms that are normally diploid. The more general term for such organisms is haploid.

Temporal terms

[edit]Neopolyploidy

[edit]A polyploid that is newly formed.

Mesopolyploidy

[edit]That has become polyploid in more recent history; it is not as new as a neopolyploid and not as old as a paleopolyploid. It is a middle aged polyploid. Often this refers to whole genome duplication followed by intermediate levels of diploidization.

Paleopolyploidy

[edit]

Ancient genome duplications probably occurred in the evolutionary history of all life. Duplication events that occurred long ago in the history of various evolutionary lineages can be difficult to detect because of subsequent diploidization (such that a polyploid starts to behave cytogenetically as a diploid over time) as mutations and gene translations gradually make one copy of each chromosome unlike the other copy. Over time, it is also common for duplicated copies of genes to accumulate mutations and become inactive pseudogenes.[45]

In many cases, these events can be inferred only through comparing sequenced genomes. Examples of unexpected but recently confirmed ancient genome duplications include baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), mustard weed/thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana), rice (Oryza sativa), and two rounds of whole genome duplication (the 2R hypothesis) in an early evolutionary ancestor of the vertebrates (which includes the human lineage) and another near the origin of the teleost fishes.[46] Angiosperms (flowering plants) have paleopolyploidy in their ancestry. All eukaryotes probably have experienced a polyploidy event at some point in their evolutionary history.

Other similar terms

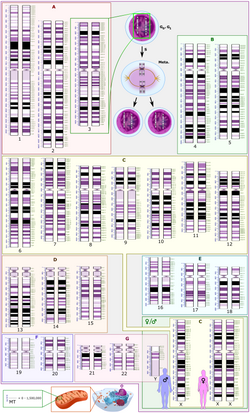

[edit]Karyotype

[edit]A karyotype is the characteristic chromosome complement of a eukaryote species.[47][48] The preparation and study of karyotypes is part of cytology and, more specifically, cytogenetics.

Although the replication and transcription of DNA is highly standardized in eukaryotes, the same cannot be said for their karyotypes, which are highly variable between species in chromosome number and in detailed organization despite being constructed out of the same macromolecules. In some cases, there is even significant variation within species. This variation provides the basis for a range of studies in what might be called evolutionary cytology.

Homoeologous chromosomes

[edit]Homoeologous chromosomes are those brought together following inter-species hybridization and allopolyploidization, and whose relationship was completely homologous in an ancestral species. For example, durum wheat is the result of the inter-species hybridization of two diploid grass species Triticum urartu and Aegilops speltoides. Both diploid ancestors had two sets of 7 chromosomes, which were similar in terms of size and genes contained on them. Durum wheat contains a hybrid genome with two sets of chromosomes derived from Triticum urartu and two sets of chromosomes derived from Aegilops speltoides. Each chromosome pair derived from the Triticum urartu parent is homoeologous to the opposite chromosome pair derived from the Aegilops speltoides parent, though each chromosome pair unto itself is homologous.

Examples

[edit]Humans

[edit]

True polyploidy rarely occurs in humans, although polyploid cells occur in highly differentiated tissue, such as liver parenchyma, heart muscle, placenta and in bone marrow.[49][50] Aneuploidy is more common.

Polyploidy occurs in humans in the form of triploidy, with 69 chromosomes (sometimes called 69, XXX), and tetraploidy with 92 chromosomes (sometimes called 92, XXXX). Triploidy, usually due to polyspermy, occurs in about 2–3% of all human pregnancies and ~15% of miscarriages.[citation needed] The vast majority of triploid conceptions end as a miscarriage; those that do survive to term typically die shortly after birth. In some cases, survival past birth may be extended if there is mixoploidy with both a diploid and a triploid cell population present. There has been one report of a child surviving to the age of seven months with complete triploidy syndrome. He failed to exhibit normal mental or physical neonatal development, and died from a Pneumocystis carinii infection, which indicates a weak immune system.[51]

Triploidy may be the result of either digyny (the extra haploid set is from the mother) or diandry (the extra haploid set is from the father). Diandry is mostly caused by reduplication of the paternal haploid set from a single sperm, but may also be the consequence of dispermic (two sperm) fertilization of the egg.[52] Digyny is most commonly caused by either failure of one meiotic division during oogenesis leading to a diploid oocyte or failure to extrude one polar body from the oocyte. Diandry appears to predominate among early miscarriages, while digyny predominates among triploid zygotes that survive into the fetal period.[53] However, among early miscarriages, digyny is also more common in those cases less than 8+1⁄2 weeks gestational age or those in which an embryo is present. There are also two distinct phenotypes in triploid placentas and fetuses that are dependent on the origin of the extra haploid set. In digyny, there is typically an asymmetric poorly grown fetus, with marked adrenal hypoplasia and a very small placenta.[54] In diandry, a partial hydatidiform mole develops.[52] These parent-of-origin effects reflect the effects of genomic imprinting.[citation needed]

Complete tetraploidy is more rarely diagnosed than triploidy, but is observed in 1–2% of early miscarriages. However, some tetraploid cells are commonly found in chromosome analysis at prenatal diagnosis and these are generally considered 'harmless'. It is not clear whether these tetraploid cells simply tend to arise during in vitro cell culture or whether they are also present in placental cells in vivo. There are, at any rate, very few clinical reports of fetuses/infants diagnosed with tetraploidy mosaicism.

Mixoploidy is quite commonly observed in human preimplantation embryos and includes haploid/diploid as well as diploid/tetraploid mixed cell populations. It is unknown whether these embryos fail to implant and are therefore rarely detected in ongoing pregnancies or if there is simply a selective process favoring the diploid cells.

Other animals

[edit]Examples in animals are more common in non-vertebrates[55] such as flatworms, leeches, and brine shrimp. Polyploidy also occurs commonly in amphibians; for example the biomedically important genus Xenopus contains many different species with as many as 12 sets of chromosomes (dodecaploid).[56] Polyploid lizards are also quite common. Most are sterile and reproduce by parthenogenesis;[citation needed] others, like Liolaemus chiliensis, maintain sexual reproduction. Polyploid mole salamanders (mostly triploids) are all female and reproduce by kleptogenesis,[57] "stealing" spermatophores from diploid males of related species to trigger egg development but not incorporating the males' DNA into the offspring.

While some tissues of mammals, such as parenchymal liver cells, are polyploid,[58][59] rare instances of polyploid mammals are known, but most often result in prenatal death. An octodontid rodent of Argentina's harsh desert regions, known as the plains viscacha rat (Tympanoctomys barrerae) has been reported as an exception to this 'rule'.[60] However, careful analysis using chromosome paints shows that there are only two copies of each chromosome in T. barrerae, not the four expected if it were truly a tetraploid.[61] This rodent is not a rat, but kin to guinea pigs and chinchillas. Its "new" diploid (2n) number is 102 and so its cells are roughly twice normal size. Its closest living relation is Octomys mimax, the Andean Viscacha-Rat of the same family, whose 2n = 56. It was therefore surmised that an Octomys-like ancestor produced tetraploid (i.e., 2n = 4x = 112) offspring that were, by virtue of their doubled chromosomes, reproductively isolated from their parents.

Polyploidy was induced in fish by Har Swarup (1956) using a cold-shock treatment of the eggs close to the time of fertilization, which produced triploid embryos that successfully matured.[62][63] Cold or heat shock has also been shown to result in unreduced amphibian gametes, though this occurs more commonly in eggs than in sperm.[64] John Gurdon (1958) transplanted intact nuclei from somatic cells to produce diploid eggs in the frog, Xenopus (an extension of the work of Briggs and King in 1952) that were able to develop to the tadpole stage.[65] The British scientist J. B. S. Haldane hailed the work for its potential medical applications and, in describing the results, became one of the first to use the word "clone" in reference to animals. Later work by Shinya Yamanaka showed how mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent, extending the possibilities to non-stem cells. Gurdon and Yamanaka were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in 2012 for this work.[65]

Fish

[edit]A polyploidy event occurred within the stem lineage of the teleost fish.[46] Some fish which include the salmonids and many cyprinids (i.e. carp) exhibit stable polyploidy, where entire species consist entirely of polyploid individuals. Some fish[examples needed] have as many as 400 chromosomes.[66]

Plants

[edit]

Polyploidy is frequent in plants, some estimates suggesting that 30–80% of living plant species are polyploid, and many lineages show evidence of ancient polyploidy (paleopolyploidy) in their genomes.[67][68][69][70] Huge explosions in angiosperm species diversity appear to have coincided with the timing of ancient genome duplications shared by many species.[71] It has been established that 15% of angiosperm and 31% of fern speciation events are accompanied by ploidy increase.[72]

Polyploid plants can arise spontaneously in nature by several mechanisms, including meiotic or mitotic failures, and fusion of unreduced (2n) gametes.[39] Both autopolyploids (e.g. potato[73]) and allopolyploids (such as canola, wheat and cotton) can be found among both wild and domesticated plant species.

Most polyploids display novel variation or morphologies relative to their parental species, that may contribute to the processes of speciation and eco-niche exploitation.[68][39] The mechanisms leading to novel variation in newly formed allopolyploids may include gene dosage effects (resulting from more numerous copies of genome content), the reunion of divergent gene regulatory hierarchies, chromosomal rearrangements, and epigenetic remodeling, all of which affect gene content and/or expression levels.[74][75][76][77] Many of these rapid changes may contribute to reproductive isolation and speciation. However, seed generated from interploidy crosses, such as between polyploids and their parent species, usually have aberrant endosperm development which impairs their viability,[78][79] thus contributing to polyploid speciation. Polyploids may also interbreed with diploids and produce polyploid seeds, as observed in the agamic complexes of Crepis.[80]

Some plants are triploid. As meiosis is disturbed, these plants are sterile, with all plants having the same genetic constitution: Among them, the exclusively vegetatively propagated saffron crocus (Crocus sativus). Also, the extremely rare Tasmanian shrub Lomatia tasmanica is a triploid sterile species.

There are few naturally occurring polyploid conifers.[81] One example is the Coast Redwood Sequoia sempervirens, which is a hexaploid (6x) with 66 chromosomes (2n = 6x = 66), although the origin is unclear.[82]

Aquatic plants, especially the Monocotyledons, include a large number of polyploids.[83]

Crops

[edit]The induction of polyploidy is a common technique to overcome the sterility of a hybrid species during plant breeding. For example, triticale is the hybrid of wheat (Triticum turgidum) and rye (Secale cereale). It combines sought-after characteristics of the parents, but the initial hybrids are sterile. After polyploidization, the hybrid becomes fertile and can thus be further propagated to become triticale.

In some situations, polyploid crops are preferred because they are sterile. For example, many seedless fruit varieties are seedless as a result of polyploidy. Such crops are propagated using asexual techniques, such as grafting.

Polyploidy in crop plants is most commonly induced by treating seeds with the chemical colchicine.

Examples

[edit]- Triploid crops: some apple varieties (such as Belle de Boskoop, Jonagold, Mutsu, Ribston Pippin), banana, citrus, ginger, watermelon,[84] saffron crocus, white pulp of coconut

- Tetraploid crops: very few apple varieties, durum or macaroni wheat, cotton, potato, canola/rapeseed, leek, tobacco, peanut, kinnow, Pelargonium

- Hexaploid crops: chrysanthemum, bread wheat, triticale, oat, kiwifruit[14]

- Octaploid crops: strawberry, dahlia, pansies, sugar cane, oca (Oxalis tuberosa)[85]

- Dodecaploid crops: some sugar cane hybrids[86]

Some crops are found in a variety of ploidies: tulips and lilies are commonly found as both diploid and triploid; daylilies (Hemerocallis cultivars) are available as either diploid or tetraploid; apples and kinnow mandarins can be diploid, triploid, or tetraploid.

Fungi

[edit]Besides plants and animals, the evolutionary history of various fungal species is dotted by past and recent whole-genome duplication events (see Albertin and Marullo 2012[87] for review). Several examples of polyploids are known:

- autopolyploid: the aquatic fungi of genus Allomyces,[88] some Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in bakery,[89] etc.

- allopolyploid: the widespread Cyathus stercoreus,[90] the allotetraploid lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus,[91] the allotriploid wine spoilage yeast Dekkera bruxellensis,[92] etc.

- paleopolyploid: the human pathogen Rhizopus oryzae,[93] the genus Saccharomyces,[94] etc.

In addition, polyploidy is frequently associated with hybridization and reticulate evolution that appear to be highly prevalent in several fungal taxa. Indeed, homoploid speciation (hybrid speciation without a change in chromosome number) has been evidenced for some fungal species (such as the basidiomycota Microbotryum violaceum[95]).

As for plants and animals, fungal hybrids and polyploids display structural and functional modifications compared to their progenitors and diploid counterparts. In particular, the structural and functional outcomes of polyploid Saccharomyces genomes strikingly reflect the evolutionary fate of plant polyploid ones. Large chromosomal rearrangements[96] leading to chimeric chromosomes[97] have been described, as well as more punctual genetic modifications such as gene loss.[98] The homoealleles of the allotetraploid yeast S. pastorianus show unequal contribution to the transcriptome.[99] Phenotypic diversification is also observed following polyploidization and/or hybridization in fungi,[100] producing the fuel for natural selection and subsequent adaptation and speciation.

Chromalveolata

[edit]Other eukaryotic taxa have experienced one or more polyploidization events during their evolutionary history (see Albertin and Marullo, 2012[87] for review). The oomycetes, which are non-true fungi members, contain several examples of paleopolyploid and polyploid species, such as within the genus Phytophthora.[101] Some species of brown algae (Fucales, Laminariales[102] and diatoms[103]) contain apparent polyploid genomes. In the Alveolata group, the remarkable species Paramecium tetraurelia underwent three successive rounds of whole-genome duplication[104] and established itself as a major model for paleopolyploid studies.

Bacteria

[edit]Each Deinococcus radiodurans bacterium contains 4-8 copies of its chromosome.[105] Exposure of D. radiodurans to X-ray irradiation or desiccation can shatter its genomes into hundred of short random fragments. Nevertheless, D. radiodurans is highly resistant to such exposures. The mechanism by which the genome is accurately restored involves RecA-mediated homologous recombination and a process referred to as extended synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA).[106]

Azotobacter vinelandii can contain up to 80 chromosome copies per cell.[107] However this is only observed in fast growing cultures, whereas cultures grown in synthetic minimal media are not polyploid.[108]

Archaea

[edit]The archaeon Halobacterium salinarium is polyploid[109] and, like Deinococcus radiodurans, is highly resistant to X-ray irradiation and desiccation, conditions that induce DNA double-strand breaks.[110] Although chromosomes are shattered into many fragments, complete chromosomes can be regenerated by making use of overlapping fragments. The mechanism employs single-stranded DNA binding protein and is likely homologous recombinational repair.[111]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Solomon E (2014). Solomon/Martin/Martin/Berg, Biology. Cengage Learning. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-285-42358-6.

- ^ Zhang S, Lin YH, Tarlow B, Zhu H (June 2019). "The origins and functions of hepatic polyploidy". Cell Cycle. 18 (12): 1302–1315. doi:10.1080/15384101.2019.1618123. PMC 6592246. PMID 31096847.

- ^ Ohno S, Muramoto J, Christian L, Atkin NB (1967). "Diploid-tetraploid relationship among old-world members of the fish family Cyprinidae". Chromosoma. 23 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/BF00293307.

- ^

- Manimekalai R, Suresh G, Govinda Kurup H, Athiappan S, Kandalam M (September 2020). "Role of NGS and SNP genotyping methods in sugarcane improvement programs". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 40 (6): 865–880. doi:10.1080/07388551.2020.1765730. PMID 32508157.

- This review cites this study:

- Vilela MM, Del Bem LE, Van Sluys MA, de Setta N, Kitajima JP, Cruz GM, et al. (February 2017). "Analysis of Three Sugarcane Homo/Homeologous Regions Suggests Independent Polyploidization Events of Saccharum officinarum and Saccharum spontaneum". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (2): 266–278. doi:10.1093/gbe/evw293. PMC 5381655. PMID 28082603.

- ^ Vallejo-Marín M, Buggs RJ, Cooley AM, Puzey JR (June 2015). "Speciation by genome duplication: Repeated origins and genomic composition of the recently formed allopolyploid species Mimulus peregrinus". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 69 (6): 1487–1500. doi:10.1111/evo.12678. PMC 5033005. PMID 25929999.

- ^ Fessenden M. "Make Room for a New Bloom: New Flower Discovered". Scientific American. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ a b Schmickl, Roswitha; Yant, Levi (April 2021). "Adaptive introgression: how polyploidy reshapes gene flow landscapes". New Phytologist. 230 (2): 457–461. Bibcode:2021NewPh.230..457S. doi:10.1111/nph.17204. ISSN 0028-646X. PMID 33454987.

- ^ a b c Marburger, Sarah; Monnahan, Patrick; Seear, Paul J.; Martin, Simon H.; Koch, Jordan; Paajanen, Pirita; Bohutínská, Magdalena; Higgins, James D.; Schmickl, Roswitha; Yant, Levi (2019-11-18). "Interspecific introgression mediates adaptation to whole genome duplication". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 5218. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.5218M. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13159-5. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6861236. PMID 31740675.

- ^ Seear, Paul J.; France, Martin G.; Gregory, Catherine L.; Heavens, Darren; Schmickl, Roswitha; Yant, Levi; Higgins, James D. (2020-07-15). "A novel allele of ASY3 is associated with greater meiotic stability in autotetraploid Arabidopsis lyrata". PLOS Genetics. 16 (7) e1008900. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008900. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 7392332. PMID 32667955.

- ^ Bertolani R (2001). "Evolution of the reproductive mechanisms in Tardigrades: a review". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 240 (3–4): 247–252. Bibcode:2001ZooAn.240..247B. doi:10.1078/0044-5231-00032. hdl:11380/304261.

- ^ McPhail, J. D. (1997). "The Origin and Speciation of Oncorhynchus Revisited". Pacific Salmon & Their Ecosystems. pp. 29–38. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-6375-4_4. ISBN 978-0-412-98691-8.

- ^ Adams KL, Wendel JF (April 2005). "Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 8 (2): 135–141. Bibcode:2005COPB....8..135A. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.001. PMID 15752992.

- ^ Singh, Dhan Pal; Singh, Asheesh K.; Singh, Arti (2021). "Wide hybridization". Plant Breeding and Cultivar Development. pp. 159–178. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-817563-7.00028-3. ISBN 978-0-12-817563-7.

- ^ a b Crowhurst, Ross N.; Whittaker, D.; Gardner, R. C. (April 1992). "The Genetic Origin of Kiwifruit". Acta Horticulturae (297): 61–62. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.1992.297.5.

- ^ Havelka, Miloš; Bytyutskyy, Dmytro; Symonová, Radka; Ráb, Petr; Flajšhans, Martin (11 February 2016). "The second highest chromosome count among vertebrates is observed in cultured sturgeon and is associated with genome plasticity". Genetics Selection Evolution. 48 12. doi:10.1186/s12711-016-0194-0. PMC 4751722. PMID 26867760.

- ^ Dierschke, Tom; Mandáková, Terezie; Mummenhoff, Klaus (9 July 2009). "A Bicontinental Origin of Polyploid Australian/New Zealand Lepidium Species (Brassicaceae)? Evidence from Genomic in situ Hybridization". Annals of Botany. 104 (4): 681–688. doi:10.1093/aob/mcp161. PMC 2729636. PMID 19589857.

- ^ Aïnouche ML, Fortune PM, Salmon A, Parisod C, Grandbastien MA, Fukunaga K, et al. (2008). "Hybridization, polyploidy and invasion: Lessons from Spartina (Poaceae)". Biological Invasions. 11 (5): 1159–1173. doi:10.1007/s10530-008-9383-2.

- ^

- Hussain F, Rana Z, Shafique H, Malik A, Hussain Z (2017). "Phytopharmacological potential of different species of Morus alba and their bioactive phytochemicals: A review". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 7 (10). Medknow: 950–956. doi:10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.09.015. ISSN 2221-1691.

- Al-Khayri JM, Jain SM, Johnson DV (2018). Al-Khayri JM, Jain SM, Johnson DV (eds.). Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Fruits. Vol. 2. Springer International Publishing AG. pp. 89–130. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-91944-7. ISBN 978-3-319-91943-0.

- This review and book cite this research.

- Zeng Q, Chen H, Zhang C, Han M, Li T, Qi X, et al. (2015). "Definition of Eight Mulberry Species in the Genus Morus by Internal Transcribed Spacer-Based Phylogeny". PLOS ONE. 10 (8) e0135411. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035411Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135411. PMC 4534381. PMID 26266951.

- ^ Soltis DE (October 1984). "Autopolyploidy in Tolmiea menziesii (Saxifragaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 71 (9): 1171–1174. doi:10.2307/2443640. JSTOR 2443640.

- ^ Drauch Schreier A, Gille D, Mahardja B, May B (November 2011). "Neutral markers confirm the octoploid origin and reveal spontaneous autopolyploidy in white sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanus". Journal of Applied Ichthyology. 27: 24–33. Bibcode:2011JApIc..27...24D. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0426.2011.01873.x. ISSN 1439-0426.

- ^ a b Bretagnolle F, Thompson JD (January 1995). "Gametes with the somatic chromosome number: mechanisms of their formation and role in the evolution of autopolyploid plants". The New Phytologist. 129 (1): 1–22. Bibcode:1995NewPh.129....1B. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1995.tb03005.x. PMID 33874422.

- ^ Müntzing A (March 1936). "The Evolutionary Significance of Autopolyploidy". Hereditas. 21 (2–3): 363–378. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5223.1936.tb03204.x. ISSN 1601-5223.

- ^ Varoquaux F, Blanvillain R, Delseny M, Gallois P (June 2000). "Less is better: new approaches for seedless fruit production". Trends in Biotechnology. 18 (6): 233–242. doi:10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01448-7. PMID 10802558.

- ^ Cotter D, O'Donovan V, O'Maoiléidigh N, Rogan G, Roche N, Wilkins NP (June 2000). "An evaluation of the use of triploid Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) in minimising the impact of escaped farmed salmon on wild populations". Aquaculture. 186 (1–2): 61–75. Bibcode:2000Aquac.186...61C. doi:10.1016/S0044-8486(99)00367-1.

- ^ Lincoln RF, Scott AP (1983). "Production of all-female triploid rainbow trout". Aquaculture. 30 (1–4): 375–380. Bibcode:1983Aquac..30..375L. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(83)90179-5.

- ^ Dermen H (May 1951). "Tetraploid and Diploid Adventitious Shoots: From a Giant Sport of McIntosh Apple". Journal of Heredity. 42 (3): 145–149. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a106189.

- ^ Dwivedi, Sangam L.; Upadhyaya, Hari D.; Stalker, H. Thomas; Blair, Matthew W.; Bertioli, David J.; Nielen, Stephan; Ortiz, Rodomiro (2007). "Enhancing Crop Gene Pools with Beneficial Traits Using Wild Relatives" (PDF). Plant Breeding Reviews. pp. 179–230. doi:10.1002/9780470380130.ch3. ISBN 978-0-470-17152-3.

- ^ a b Justin R (January 2002). "Neopolyploidy in Flowering Plants". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 33 (1): 589–639. Bibcode:2002AnRES..33..589R. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150437.

- ^ Yant, Levi; Hollister, Jesse D.; Wright, Kevin M.; Arnold, Brian J.; Higgins, James D.; Franklin, F. Chris H.; Bomblies, Kirsten (November 2013). "Meiotic Adaptation to Genome Duplication in Arabidopsis arenosa". Current Biology. 23 (21): 2151–2156. Bibcode:2013CBio...23.2151Y. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.059. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 3859316. PMID 24139735.

- ^ Seear, Paul J.; France, Martin G.; Gregory, Catherine L.; Heavens, Darren; Schmickl, Roswitha; Yant, Levi; Higgins, James D. (2020-07-15). Grelon, Mathilde (ed.). "A novel allele of ASY3 is associated with greater meiotic stability in autotetraploid Arabidopsis lyrata". PLOS Genetics. 16 (7) e1008900. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008900. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 7392332. PMID 32667955.

- ^ Parisod C, Holderegger R, Brochmann C (April 2010). "Evolutionary consequences of autopolyploidy". The New Phytologist. 186 (1): 5–17. Bibcode:2010NewPh.186....5P. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03142.x. PMID 20070540.

- ^ a b Le Comber SC, Ainouche ML, Kovarik A, Leitch AR (April 2010). "Making a functional diploid: from polysomic to disomic inheritance". The New Phytologist. 186 (1): 113–122. Bibcode:2010NewPh.186..113L. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03117.x. PMID 20028473.

- ^ Stebbins GL (1947). Types of Polyploids: Their Classification and Significance. Advances in Genetics. Vol. 1. pp. 403–429. doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60490-3. ISBN 978-0-12-017601-4. PMID 20259289.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Stebbins GL (1950). Variation and Evolution in Plants. Oxford University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Ramsey J, Schemske DW (January 1998). "Pathways, Mechanisms, and Rates of Polyploid Formation in Flowering Plants". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 29 (1): 467–501. Bibcode:1998AnRES..29..467R. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.467.

- ^ Barker MS, Arrigo N, Baniaga AE, Li Z, Levin DA (April 2016). "On the relative abundance of autopolyploids and allopolyploids". The New Phytologist. 210 (2): 391–398. Bibcode:2016NewPh.210..391B. doi:10.1111/nph.13698. PMID 26439879.

- ^ Doyle JJ, Sherman-Broyles S (January 2017). "Double trouble: taxonomy and definitions of polyploidy". The New Phytologist. 213 (2): 487–493. Bibcode:2017NewPh.213..487D. doi:10.1111/nph.14276. PMID 28000935.

- ^ a b Ramsey J (January 1998). "Pathways, Mechanisms, and Rates of Polyploid Formation in Flowering Plants". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 29 (1): 467–501. Bibcode:1998AnRES..29..467R. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.467.

- ^ a b c Comai L (November 2005). "The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 6 (11): 836–846. doi:10.1038/nrg1711. PMID 16304599.

- ^ Ownbey M (January 1950). "Natural Hybridization and Amphiploidy in the Genus Tragopogon". American Journal of Botany. 37 (7): 487–499. doi:10.2307/2438023. JSTOR 2438023.

- ^ Schmid M, Evans BJ, Bogart JP (2015). "Polyploidy in Amphibia". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 145 (3–4): 315–330. doi:10.1159/000431388. PMID 26112701.

- ^ Griffiths AJ (1999). An Introduction to genetic analysis. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3520-5.[page needed]

- ^ Parmacek MS, Epstein JA (July 2009). "Cardiomyocyte renewal". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (1): 86–88. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr0903347. PMC 4111249. PMID 19571289.

- ^ Mendell JE, Clements KD, Choat JH, Angert ER (May 2008). "Extreme polyploidy in a large bacterium". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (18): 6730–6734. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.6730M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707522105. PMC 2373351. PMID 18445653.

- ^ Edger PP, Pires JC (2009). "Gene and genome duplications: the impact of dosage-sensitivity on the fate of nuclear genes". Chromosome Research. 17 (5): 699–717. doi:10.1007/s10577-009-9055-9. PMID 19802709.

- ^ a b Clarke JT, Lloyd GT, Friedman M (October 2016). "Little evidence for enhanced phenotypic evolution in early teleosts relative to their living fossil sister group". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (41): 11531–11536. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11311531C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607237113. PMC 5068283. PMID 27671652.

- ^ White MJ (1973). The Chromosomes (6th ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. p. 28.

- ^ Stebbins GL (1950). "Chapter XII: The Karyotype". Variation and Evolution in Plants. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Velicky P, Meinhardt G, Plessl K, Vondra S, Weiss T, Haslinger P, et al. (October 2018). "Genome amplification and cellular senescence are hallmarks of human placenta development". PLOS Genetics. 14 (10) e1007698. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007698. PMC 6200260. PMID 30312291.

- ^ Winkelmann M, Pfitzer P, Schneider W (December 1987). "Significance of polyploidy in megakaryocytes and other cells in health and tumor disease". Klinische Wochenschrift. 65 (23): 1115–1131. doi:10.1007/BF01734832. PMID 3323647.

- ^ "Triploidy". National Organization for Rare Disorders. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

- ^ a b Baker P, Monga A, Baker P (2006). Gynaecology by Ten Teachers. London: Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-81662-2.

- ^ Brancati F, Mingarelli R, Dallapiccola B (December 2003). "Recurrent triploidy of maternal origin". European Journal of Human Genetics. 11 (12): 972–974. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201076. PMID 14508508.

- ^ Wick JB, Johnson KJ, O'Brien J, Wick MJ (May 2013). "Second-trimester diagnosis of triploidy: a series of four cases". AJP Reports. 3 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1331378. PMC 3699153. PMID 23943708.

- ^ Otto SP, Whitton J (2000). "Polyploid incidence and evolution". Annual Review of Genetics. 34 (1): 401–437. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.323.1059. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.401. PMID 11092833.

- ^ Cannatella DC, De Sa RO (1993). "Xenopus laevis as a Model Organism". Society of Systematic Biologists. 42 (4): 476–507. doi:10.1093/sysbio/42.4.476.

- ^ Bogart JP, Bi K, Fu J, Noble DW, Niedzwiecki J (February 2007). "Unisexual salamanders (genus Ambystoma) present a new reproductive mode for eukaryotes". Genome. 50 (2): 119–136. doi:10.1139/g06-152. PMID 17546077.

- ^ Epstein CJ (February 1967). "Cell size, nuclear content, and the development of polyploidy in the Mammalian liver". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 57 (2): 327–334. Bibcode:1967PNAS...57..327E. doi:10.1073/pnas.57.2.327. PMC 335509. PMID 16591473.

- ^ Donne R, Saroul-Aïnama M, Cordier P, Celton-Morizur S, Desdouets C (July 2020). "Polyploidy in liver development, homeostasis and disease". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 17 (7): 391–405. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-0284-x. PMID 32242122.

- ^ Gallardo MH, González CA, Cebrián I (August 2006). "Molecular cytogenetics and allotetraploidy in the red vizcacha rat, Tympanoctomys barrerae (Rodentia, Octodontidae)". Genomics. 88 (2): 214–221. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.02.010. hdl:10533/178085. PMID 16580173.

- ^ Svartman M, Stone G, Stanyon R (April 2005). "Molecular cytogenetics discards polyploidy in mammals". Genomics. 85 (4): 425–430. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.12.004. PMID 15780745.

- ^ Swarup H (1956). "Production of Heteroploidy in the Three-Spined Stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus (L.)". Nature. 178 (4542): 1124–1125. Bibcode:1956Natur.178.1124S. doi:10.1038/1781124a0.

- ^ Swarup H (1959). "Production of triploidy in Gasterosteus aculeatus (L.)". Journal of Genetics. 56 (2): 129–142. doi:10.1007/BF02984740.

- ^ Mable BK, Alexandrou MA, Taylor MI (2011). "Genome duplication in amphibians and fish: an extended synthesis". Journal of Zoology. 284 (3): 151–182. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00829.x.

- ^ a b "Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2012 awarded for discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent". ScienceDaily (Press release). Nobel Foundation. 8 October 2012.

- ^ Smith LE (October 2012). "A suggestion to the medical librarians. 1920". Journal of the Medical Library Association. 100 (4 Suppl): B. doi:10.1023/B:RFBF.0000033049.00668.fe. PMC 3571666. PMID 23509424.

- ^ Meyers LA, Levin DA (June 2006). "On the abundance of polyploids in flowering plants". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 60 (6): 1198–1206. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01198.x. PMID 16892970.

- ^ a b Rieseberg LH, Willis JH (August 2007). "Plant speciation". Science. 317 (5840): 910–914. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..910R. doi:10.1126/science.1137729. PMC 2442920. PMID 17702935.

- ^ Otto SP (November 2007). "The evolutionary consequences of polyploidy". Cell. 131 (3): 452–462. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.022. PMID 17981114.

- ^ One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes Initiative (October 2019). "One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants". Nature. 574 (7780): 679–685. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1693-2. PMC 6872490. PMID 31645766.

- ^ De Bodt S, Maere S, Van de Peer Y (November 2005). "Genome duplication and the origin of angiosperms". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 20 (11): 591–597. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.07.008. PMID 16701441.

- ^ Wood TE, Takebayashi N, Barker MS, Mayrose I, Greenspoon PB, Rieseberg LH (August 2009). "The frequency of polyploid speciation in vascular plants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (33): 13875–13879. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10613875W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811575106. JSTOR 40484335. PMC 2728988. PMID 19667210.

- ^ Xu X, Pan S, Cheng S, Zhang B, Mu D, Ni P, et al. (July 2011). "Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato". Nature. 475 (7355): 189–195. doi:10.1038/nature10158. hdl:10533/238440. PMID 21743474.

- ^ Osborn TC, Pires JC, Birchler JA, Auger DL, Chen ZJ, Lee HS, et al. (March 2003). "Understanding mechanisms of novel gene expression in polyploids". Trends in Genetics. 19 (3): 141–147. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00015-5. PMID 12615008.

- ^ Chen ZJ, Ni Z (March 2006). "Mechanisms of genomic rearrangements and gene expression changes in plant polyploids". BioEssays. 28 (3): 240–252. doi:10.1002/bies.20374. PMC 1986666. PMID 16479580.

- ^ Chen ZJ (2007). "Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms for gene expression and phenotypic variation in plant polyploids". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 58 (1): 377–406. Bibcode:2007AnRPB..58..377C. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103835. PMC 1949485. PMID 17280525.

- ^ Albertin W, Balliau T, Brabant P, Chèvre AM, Eber F, Malosse C, Thiellement H (June 2006). "Numerous and rapid nonstochastic modifications of gene products in newly synthesized Brassica napus allotetraploids". Genetics. 173 (2): 1101–1113. doi:10.1534/genetics.106.057554. PMC 1526534. PMID 16624896.

- ^ Pennington PD, Costa LM, Gutierrez-Marcos JF, Greenland AJ, Dickinson HG (April 2008). "When genomes collide: aberrant seed development following maize interploidy crosses". Annals of Botany. 101 (6): 833–843. doi:10.1093/aob/mcn017. PMC 2710208. PMID 18276791.

- ^ von Wangenheim KH, Peterson HP (June 2004). "Aberrant endosperm development in interploidy crosses reveals a timer of differentiation". Developmental Biology. 270 (2): 277–289. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.014. PMID 15183714.

- ^ Whitton J, Sears CJ, Maddison WP (December 2017). "Co-occurrence of related asexual, but not sexual, lineages suggests that reproductive interference limits coexistence". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 284 (1868) 20171579. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1579. PMC 5740271. PMID 29212720.

- ^ Halabi K, Shafir A, Mayrose I (June 2023). "PloiDB: The plant ploidy database". The New Phytologist. 240 (3): 918–927. Bibcode:2023NewPh.240..918H. doi:10.1111/nph.19057. PMID 37337836.

- ^ Ahuja MR, Neale DB (2002). "Origins of Polyploidy in Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens (D. Don) Endl.) and Relationship of Coast Redwood to other Genera of Taxodiaceae". Silvae Genetica. 51: 2–3. INIST 13965465.

- ^ Les DH, Philbrick CT (1993). "Studies of hybridization and chromosome number variation in aquatic angiosperms: Evolutionary implications". Aquatic Botany. 44 (2–3): 181–228. Bibcode:1993AqBot..44..181L. doi:10.1016/0304-3770(93)90071-4.

- ^ Karp, David (25 March 2007). "Seedless Fruits Make Others Needless". The Ledger. The New York Times.

- ^ Emshwiller E (2006). "Origins of polyploid crops: The example of the octaploid tuber crop Oxalis tuberosa". In Zeder MA, Decker-Walters D, Emshwiller E, Bradley D, Smith BD (eds.). Documenting Domestication: New Genetic and Archaeological Paradigms. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 153–168. ISBN 978-0-520-24638-6.

- ^ Le Cunff L, Garsmeur O, Raboin LM, Pauquet J, Telismart H, Selvi A, et al. (September 2008). "Diploid/polyploid syntenic shuttle mapping and haplotype-specific chromosome walking toward a rust resistance gene (Bru1) in highly polyploid sugarcane (2n approximately 12x approximately 115)". Genetics. 180 (1): 649–660. doi:10.1534/genetics.108.091355. PMC 2535714. PMID 18757946.

- ^ a b c Albertin W, Marullo P (July 2012). "Polyploidy in fungi: evolution after whole-genome duplication". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 279 (1738): 2497–2509. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0434. PMC 3350714. PMID 22492065.

- ^ Emerson R, Wilson CM (1954). "Interspecific Hybrids and the Cytogenetics and Cytotaxonomy of Euallomyces". Mycologia. 46 (4): 393–434. doi:10.1080/00275514.1954.12024382. JSTOR 4547843.

- ^ Albertin W, Marullo P, Aigle M, Bourgais A, Bely M, Dillmann C, et al. (November 2009). "Evidence for autotetraploidy associated with reproductive isolation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: towards a new domesticated species". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 22 (11): 2157–2170. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01828.x. PMID 19765175.

- ^ Lu BC (1964). "Polyploidy in the Basidiomycete Cyathus stercoreus". American Journal of Botany. 51 (3): 343–347. doi:10.2307/2440307. JSTOR 2440307.

- ^ Libkind D, Hittinger CT, Valério E, Gonçalves C, Dover J, Johnston M, et al. (August 2011). "Microbe domestication and the identification of the wild genetic stock of lager-brewing yeast". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (35): 14539–14544. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10814539L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1105430108. PMC 3167505. PMID 21873232.

- ^ Borneman AR, Zeppel R, Chambers PJ, Curtin CD (February 2014). "Insights into the Dekkera bruxellensis genomic landscape: comparative genomics reveals variations in ploidy and nutrient utilisation potential amongst wine isolates". PLOS Genetics. 10 (2) e1004161. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004161. PMC 3923673. PMID 24550744.

- ^ Ma LJ, Ibrahim AS, Skory C, Grabherr MG, Burger G, Butler M, et al. (July 2009). Madhani HD (ed.). "Genomic analysis of the basal lineage fungus Rhizopus oryzae reveals a whole-genome duplication". PLOS Genetics. 5 (7) e1000549. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000549. PMC 2699053. PMID 19578406.

- ^ Wong S, Butler G, Wolfe KH (July 2002). "Gene order evolution and paleopolyploidy in hemiascomycete yeasts". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (14): 9272–9277. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.9272W. doi:10.1073/pnas.142101099. JSTOR 3059188. PMC 123130. PMID 12093907.

- ^ Devier B, Aguileta G, Hood ME, Giraud T (2009). "Using phylogenies of pheromone receptor genes in the Microbotryum violaceum species complex to investigate possible speciation by hybridization". Mycologia. 102 (3): 689–696. doi:10.3852/09-192. PMID 20524600.

- ^ Dunn B, Sherlock G (October 2008). "Reconstruction of the genome origins and evolution of the hybrid lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus". Genome Research. 18 (10): 1610–1623. doi:10.1101/gr.076075.108. PMC 2556262. PMID 18787083.

- ^ Nakao Y, Kanamori T, Itoh T, Kodama Y, Rainieri S, Nakamura N, et al. (April 2009). "Genome sequence of the lager brewing yeast, an interspecies hybrid". DNA Research. 16 (2): 115–129. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsp003. PMC 2673734. PMID 19261625.

- ^ Scannell DR, Byrne KP, Gordon JL, Wong S, Wolfe KH (March 2006). "Multiple rounds of speciation associated with reciprocal gene loss in polyploid yeasts". Nature. 440 (7082): 341–345. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..341S. doi:10.1038/nature04562. hdl:2262/22660. PMID 16541074.

- ^ Minato T, Yoshida S, Ishiguro T, Shimada E, Mizutani S, Kobayashi O, Yoshimoto H (March 2009). "Expression profiling of the bottom fermenting yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus orthologous genes using oligonucleotide microarrays". Yeast. 26 (3): 147–165. doi:10.1002/yea.1654. PMID 19243081.

- ^ Lidzbarsky GA, Shkolnik T, Nevo E (June 2009). Idnurm A (ed.). "Adaptive response to DNA-damaging agents in natural Saccharomyces cerevisiae populations from "Evolution Canyon", Mt. Carmel, Israel". PLOS ONE. 4 (6) e5914. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5914L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005914. PMC 2690839. PMID 19526052.

- ^ Ioos R, Andrieux A, Marçais B, Frey P (July 2006). "Genetic characterization of the natural hybrid species Phytophthora alni as inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analyses" (PDF). Fungal Genetics and Biology. 43 (7): 511–529. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2006.02.006. PMID 16626980.

- ^ Phillips N, Kapraun DF, Gómez Garreta A, Ribera Siguan MA, Rull JL, Salvador Soler N, et al. (2011). "Estimates of nuclear DNA content in 98 species of brown algae (Phaeophyta)". AoB Plants. 2011 plr001. doi:10.1093/aobpla/plr001. PMC 3064507. PMID 22476472.

- ^ Chepurnov VA, Mann DG, Vyverman W, Sabbe K, Danielidis DB (2002). "Sexual Reproduction, Mating System, and Protoplast Dynamics of Seminavis (Bacillariophyceae)". Journal of Phycology. 38 (5): 1004–1019. Bibcode:2002JPcgy..38.1004C. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2002.t01-1-01233.x.

- ^ Aury JM, Jaillon O, Duret L, Noel B, Jubin C, Porcel BM, et al. (November 2006). "Global trends of whole-genome duplications revealed by the ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia". Nature. 444 (7116): 171–178. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..171A. doi:10.1038/nature05230. PMID 17086204.

- ^ Hansen MT (April 1978). "Multiplicity of genome equivalents in the radiation-resistant bacterium Micrococcus radiodurans". Journal of Bacteriology. 134 (1): 71–75. doi:10.1128/JB.134.1.71-75.1978. PMC 222219. PMID 649572.

- ^ Zahradka K, Slade D, Bailone A, Sommer S, Averbeck D, Petranovic M, et al. (October 2006). "Reassembly of shattered chromosomes in Deinococcus radiodurans". Nature. 443 (7111): 569–573. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..569Z. doi:10.1038/nature05160. PMID 17006450.

- ^ Nagpal P, Jafri S, Reddy MA, Das HK (June 1989). "Multiple chromosomes of Azotobacter vinelandii". Journal of Bacteriology. 171 (6): 3133–3138. doi:10.1128/jb.171.6.3133-3138.1989. PMC 210026. PMID 2785985.

- ^ Maldonado R, Jiménez J, Casadesús J (July 1994). "Changes of ploidy during the Azotobacter vinelandii growth cycle". Journal of Bacteriology. 176 (13): 3911–3919. doi:10.1128/jb.176.13.3911-3919.1994. PMC 205588. PMID 8021173.

- ^ Soppa J (January 2011). "Ploidy and gene conversion in Archaea". Biochemical Society Transactions. 39 (1): 150–154. doi:10.1042/BST0390150. PMID 21265763.

- ^ Kottemann M, Kish A, Iloanusi C, Bjork S, DiRuggiero J (June 2005). "Physiological responses of the halophilic archaeon Halobacterium sp. strain NRC1 to desiccation and gamma irradiation". Extremophiles. 9 (3): 219–227. doi:10.1007/s00792-005-0437-4. PMID 15844015.

- ^ DeVeaux LC, Müller JA, Smith J, Petrisko J, Wells DP, DasSarma S (October 2007). "Extremely radiation-resistant mutants of a halophilic archaeon with increased single-stranded DNA-binding protein (RPA) gene expression". Radiation Research. 168 (4): 507–514. Bibcode:2007RadR..168..507D. doi:10.1667/RR0935.1. PMID 17903038.

Further reading

[edit]- Snustad DP, Simmons MJ (2006). Principles of Genetics (4th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-69939-2.

- The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (December 2000). "Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana". Nature. 408 (6814): 796–815. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..796T. doi:10.1038/35048692. PMID 11130711.

- Eakin GS, Behringer RR (December 2003). "Tetraploid development in the mouse". Developmental Dynamics. 228 (4): 751–766. doi:10.1002/dvdy.10363. PMID 14648853.

- Gaeta RT, Pires JC, Iniguez-Luy F, Leon E, Osborn TC (November 2007). "Genomic changes in resynthesized Brassica napus and their effect on gene expression and phenotype". The Plant Cell. 19 (11): 3403–3417. Bibcode:2007PlanC..19.3403G. doi:10.1105/tpc.107.054346. PMC 2174891. PMID 18024568.

- Gregory, T. Ryan; Mable, Barbara K. (2005). "Polyploidy in Animals". The Evolution of the Genome. pp. 427–517. doi:10.1016/B978-012301463-4/50010-3. ISBN 978-0-12-301463-4.

- Jaillon O, Aury JM, Brunet F, Petit JL, Stange-Thomann N, Mauceli E, et al. (October 2004). "Genome duplication in the teleost fish Tetraodon nigroviridis reveals the early vertebrate proto-karyotype". Nature. 431 (7011): 946–957. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..946J. doi:10.1038/nature03025. PMID 15496914.

- Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Van de Peer Y, Vandepoele K (March 2005). "Ancient duplication of cereal genomes". The New Phytologist. 165 (3): 658–661. Bibcode:2005NewPh.165..658P. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01347.x. PMID 15720677.

- Raes J, Vandepoele K, Simillion C, Saeys Y, Van de Peer Y (2003). "Investigating ancient duplication events in the Arabidopsis genome". Journal of Structural and Functional Genomics. 3 (1–4): 117–129. doi:10.1023/A:1022666020026. PMID 12836691.

- Simillion C, Vandepoele K, Van Montagu MC, Zabeau M, Van de Peer Y (October 2002). "The hidden duplication past of Arabidopsis thaliana". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (21): 13627–13632. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9913627S. doi:10.1073/pnas.212522399. JSTOR 3073458. PMC 129725. PMID 12374856.

- Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Schemske DW, Hancock JF, Thompson JN, Husband BC, Judd WS (2007). "Autopolyploidy in Angiosperms: Have We Grossly Underestimated the Number of Species?". Taxon. 56 (1): 13–30. JSTOR 25065732.

- Soltis DE, Buggs RJ, Doyle JJ, Soltis PS (2010). "What we still don't know about polyploidy". Taxon. 59 (5): 1387–1403. Bibcode:2010Taxon..59.1387S. doi:10.1002/tax.595006.

- Taylor JS, Braasch I, Frickey T, Meyer A, Van de Peer Y (March 2003). "Genome duplication, a trait shared by 22000 species of ray-finned fish". Genome Research. 13 (3): 382–390. doi:10.1101/gr.640303. PMC 430266. PMID 12618368.

- Tate, Jennifer A.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Soltis, Pamela S. (2005). "Polyploidy in Plants". The Evolution of the Genome. pp. 371–426. doi:10.1016/B978-012301463-4/50009-7. ISBN 978-0-12-301463-4.

- Van de Peer Y, Taylor JS, Meyer A (2003). "Are all fishes ancient polyploids?". Journal of Structural and Functional Genomics. 3 (1–4): 65–73. doi:10.1023/A:1022652814749. PMID 12836686.

- Van de Peer Y (2004). "Tetraodon genome confirms Takifugu findings: most fish are ancient polyploids". Genome Biology. 5 (12): 250. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-250. PMC 545788. PMID 15575976.

- Van De Peer, Yves; Meyer, Axel (2005). "Large-Scale Gene and Ancient Genome Duplications". The Evolution of the Genome. pp. 329–368. doi:10.1016/B978-012301463-4/50008-5. ISBN 978-0-12-301463-4.

- Wolfe KH, Shields DC (June 1997). "Molecular evidence for an ancient duplication of the entire yeast genome". Nature. 387 (6634): 708–713. Bibcode:1997Natur.387..708W. doi:10.1038/42711. PMID 9192896.

- Wolfe KH (May 2001). "Yesterday's polyploids and the mystery of diploidization". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 2 (5): 333–341. doi:10.1038/35072009. PMID 11331899.

External links

[edit]- Polyploidy on Kimball's Biology Pages

- The polyploidy portal a community-editable project with information, research, education, and a bibliography about polyploidy.