Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Social network

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Sociology |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

A social network is a social structure consisting of a set of social actors (such as individuals or organizations), networks of dyadic ties, and other social interactions between actors. The social network perspective provides a set of methods for analyzing the structure of whole social entities along with a variety of theories explaining the patterns observed in these structures.[1] The study of these structures uses social network analysis to identify local and global patterns, locate influential entities, and examine dynamics of networks. For instance, social network analysis has been used in studying the spread of misinformation on social media platforms or analyzing the influence of key figures in social networks.

Social networks and the analysis of them is an inherently interdisciplinary academic field which emerged from social psychology, sociology, statistics, and graph theory. Georg Simmel authored early structural theories in sociology emphasizing the dynamics of triads and "web of group affiliations".[2] Jacob Moreno is credited with developing the first sociograms in the 1930s to study interpersonal relationships. These approaches were mathematically formalized in the 1950s and theories and methods of social networks became pervasive in the social and behavioral sciences by the 1980s.[1][3] Social network analysis is now one of the major paradigms in contemporary sociology, and is also employed in a number of other social and formal sciences. Together with other complex networks, it forms part of the nascent field of network science.[4][5]

Overview

[edit]The social network is a theoretical construct useful in the social sciences to study relationships between individuals, groups, organizations, or even entire societies (social units, see differentiation). The term is used to describe a social structure determined by such interactions. The ties through which any given social unit connects represent the convergence of the various social contacts of that unit. This theoretical approach is, necessarily, relational. An axiom of the social network approach to understanding social interaction is that social phenomena should be primarily conceived and investigated through the properties of relations between and within units, instead of the properties of these units themselves. Thus, one common criticism of social network theory is that individual agency is often ignored[6] although this may not be the case in practice (see agent-based modeling). Precisely because many different types of relations, singular or in combination, form these network configurations, network analytics are useful to a broad range of research enterprises. In social science, these fields of study include, but are not limited to anthropology, biology, communication studies, economics, geography, information science, organizational studies, social psychology, sociology, and sociolinguistics.

History

[edit]In the late 1890s, both Émile Durkheim and Ferdinand Tönnies foreshadowed the idea of social networks in their theories and research of social groups. Tönnies argued that social groups can exist as personal and direct social ties that either link individuals who share values and belief (Gemeinschaft, German, commonly translated as "community") or impersonal, formal, and instrumental social links (Gesellschaft, German, commonly translated as "society").[7] Durkheim gave a non-individualistic explanation of social facts, arguing that social phenomena arise when interacting individuals constitute a reality that can no longer be accounted for in terms of the properties of individual actors.[8] Georg Simmel, writing at the turn of the twentieth century, pointed to the nature of networks and the effect of network size on interaction and examined the likelihood of interaction in loosely knit networks rather than groups.[9]

Major developments in the field can be seen in the 1930s by several groups in psychology, anthropology, and mathematics working independently.[6][10][11] In psychology, in the 1930s, Jacob L. Moreno began systematic recording and analysis of social interaction in small groups, especially classrooms and work groups (see sociometry). In anthropology, the foundation for social network theory is the theoretical and ethnographic work of Bronislaw Malinowski,[12] Alfred Radcliffe-Brown,[13][14] and Claude Lévi-Strauss.[15] A group of social anthropologists associated with Max Gluckman and the Manchester School, including John A. Barnes,[16] J. Clyde Mitchell and Elizabeth Bott Spillius,[17][18] often are credited with performing some of the first fieldwork from which network analyses were performed, investigating community networks in southern Africa, India and the United Kingdom.[6] Concomitantly, British anthropologist S. F. Nadel codified a theory of social structure that was influential in later network analysis.[19] In sociology, the early (1930s) work of Talcott Parsons set the stage for taking a relational approach to understanding social structure.[20][21] Later, drawing upon Parsons' theory, the work of sociologist Peter Blau provides a strong impetus for analyzing the relational ties of social units with his work on social exchange theory.[22][23][24]

By the 1970s, a growing number of scholars worked to combine the different tracks and traditions. One group consisted of sociologist Harrison White and his students at the Harvard University Department of Social Relations. Also independently active in the Harvard Social Relations department at the time were Charles Tilly, who focused on networks in political and community sociology and social movements, and Stanley Milgram, who developed the "six degrees of separation" thesis.[25] Mark Granovetter[26] and Barry Wellman[27] are among the former students of White who elaborated and championed the analysis of social networks.[26][28][29][30]

Beginning in the late 1990s, social network analysis experienced work by sociologists, political scientists, and physicists such as Duncan J. Watts, Albert-László Barabási, Peter Bearman, Nicholas A. Christakis, James H. Fowler, and others, developing and applying new models and methods to emerging data available about online social networks, as well as "digital traces" regarding face-to-face networks.

Levels of analysis

[edit]

In general, social networks are self-organizing, emergent, and complex, such that a globally coherent pattern appears from the local interaction of the elements that make up the system.[32][33] These patterns become more apparent as network size increases. However, a global network analysis[34] of, for example, all interpersonal relationships in the world is not feasible and is likely to contain so much information as to be uninformative. Practical limitations of computing power, ethics and participant recruitment and payment also limit the scope of a social network analysis.[35][36] The nuances of a local system may be lost in a large network analysis, hence the quality of information may be more important than its scale for understanding network properties. Thus, social networks are analyzed at the scale relevant to the researcher's theoretical question. Although levels of analysis are not necessarily mutually exclusive, there are three general levels into which networks may fall: micro-level, meso-level, and macro-level.

Micro level

[edit]At the micro-level, social network research typically begins with an individual, snowballing as social relationships are traced, or may begin with a small group of individuals in a particular social context.

Dyadic level: A dyad is a social relationship between two individuals. Network research on dyads may concentrate on structure of the relationship (e.g. multiplexity, strength), social equality, and tendencies toward reciprocity/mutuality.

Triadic level: Add one individual to a dyad, and you have a triad. Research at this level may concentrate on factors such as balance and transitivity, as well as social equality and tendencies toward reciprocity/mutuality.[35] In the balance theory of Fritz Heider the triad is the key to social dynamics. The discord in a rivalrous love triangle is an example of an unbalanced triad, likely to change to a balanced triad by a change in one of the relations. The dynamics of social friendships in society has been modeled by balancing triads. The study is carried forward with the theory of signed graphs.

Actor level: The smallest unit of analysis in a social network is an individual in their social setting, i.e., an "actor" or "ego." Egonetwork analysis focuses on network characteristics, such as size, relationship strength, density, centrality, prestige and roles such as isolates, liaisons, and bridges.[37] Such analyses, are most commonly used in the fields of psychology or social psychology, ethnographic kinship analysis or other genealogical studies of relationships between individuals.

Subset level: Subset levels of network research problems begin at the micro-level, but may cross over into the meso-level of analysis. Subset level research may focus on distance and reachability, cliques, cohesive subgroups, or other group actions or behavior.[38]

Meso level

[edit]In general, meso-level theories begin with a population size that falls between the micro- and macro-levels. However, meso-level may also refer to analyses that are specifically designed to reveal connections between micro- and macro-levels. Meso-level networks are low density and may exhibit causal processes distinct from interpersonal micro-level networks.[39]

Organizations: Formal organizations are social groups that distribute tasks for a collective goal.[40] Network research on organizations may focus on either intra-organizational or inter-organizational ties in terms of formal or informal relationships. Intra-organizational networks themselves often contain multiple levels of analysis, especially in larger organizations with multiple branches, franchises or semi-autonomous departments. In these cases, research is often conducted at a work group level and organization level, focusing on the interplay between the two structures.[40] Experiments with networked groups online have documented ways to optimize group-level coordination through diverse interventions, including the addition of autonomous agents to the groups.[41]

Randomly distributed networks: Exponential random graph models of social networks became state-of-the-art methods of social network analysis in the 1980s. This framework has the capacity to represent social-structural effects commonly observed in many human social networks, including general degree-based structural effects commonly observed in many human social networks as well as reciprocity and transitivity, and at the node-level, homophily and attribute-based activity and popularity effects, as derived from explicit hypotheses about dependencies among network ties. Parameters are given in terms of the prevalence of small subgraph configurations in the network and can be interpreted as describing the combinations of local social processes from which a given network emerges. These probability models for networks on a given set of actors allow generalization beyond the restrictive dyadic independence assumption of micro-networks, allowing models to be built from theoretical structural foundations of social behavior.[42]

Scale-free networks: A scale-free network is a network whose degree distribution follows a power law, at least asymptotically. In network theory a scale-free ideal network is a random network with a degree distribution that unravels the size distribution of social groups.[43] Specific characteristics of scale-free networks vary with the theories and analytical tools used to create them, however, in general, scale-free networks have some common characteristics. One notable characteristic in a scale-free network is the relative commonness of vertices with a degree that greatly exceeds the average. The highest-degree nodes are often called "hubs", and may serve specific purposes in their networks, although this depends greatly on the social context. Another general characteristic of scale-free networks is the clustering coefficient distribution, which decreases as the node degree increases. This distribution also follows a power law.[44] The Barabási model of network evolution shown above is an example of a scale-free network.

Macro level

[edit]Rather than tracing interpersonal interactions, macro-level analyses generally trace the outcomes of interactions, such as economic or other resource transfer interactions over a large population.

Large-scale networks: Large-scale network is a term somewhat synonymous with "macro-level." It is primarily used in social and behavioral sciences, and in economics. Originally, the term was used extensively in the computer sciences (see large-scale network mapping).

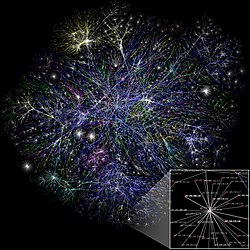

Complex networks: Most larger social networks display features of social complexity, which involves substantial non-trivial features of network topology, with patterns of complex connections between elements that are neither purely regular nor purely random (see, complexity science, dynamical system and chaos theory), as do biological, and technological networks. Such complex network features include a heavy tail in the degree distribution, a high clustering coefficient, assortativity or disassortativity among vertices, community structure (see stochastic block model), and hierarchical structure. In the case of agency-directed networks these features also include reciprocity, triad significance profile (TSP, see network motif), and other features. In contrast, many of the mathematical models of networks that have been studied in the past, such as lattices and random graphs, do not show these features.[45]

Theoretical links

[edit]Imported theories

[edit]Various theoretical frameworks have been imported for the use of social network analysis. The most prominent of these are Graph theory, Balance theory, Social comparison theory, and more recently, the Social identity approach.[46]

Indigenous theories

[edit]Few complete theories have been produced from social network analysis. Two that have are structural role theory and heterophily theory.

The basis of Heterophily Theory was the finding in one study that more numerous weak ties can be important in seeking information and innovation, as cliques have a tendency to have more homogeneous opinions as well as share many common traits. This homophilic tendency was the reason for the members of the cliques to be attracted together in the first place. However, being similar, each member of the clique would also know more or less what the other members knew. To find new information or insights, members of the clique will have to look beyond the clique to its other friends and acquaintances. This is what Granovetter called "the strength of weak ties".[47]

Structural holes

[edit]In the context of networks, social capital exists where people have an advantage because of their location in a network. Contacts in a network provide information, opportunities and perspectives that can be beneficial to the central player in the network. Most social structures tend to be characterized by dense clusters of strong connections.[48] Information within these clusters tends to be rather homogeneous and redundant. Non-redundant information is most often obtained through contacts in different clusters.[49] When two separate clusters possess non-redundant information, there is said to be a structural hole between them.[49] Thus, a network that bridges structural holes will provide network benefits that are in some degree additive, rather than overlapping. An ideal network structure has a vine and cluster structure, providing access to many different clusters and structural holes.[49]

Networks rich in structural holes are a form of social capital in that they offer information benefits. The main player in a network that bridges structural holes is able to access information from diverse sources and clusters.[49] For example, in business networks, this is beneficial to an individual's career because he is more likely to hear of job openings and opportunities if his network spans a wide range of contacts in different industries/sectors. This concept is similar to Mark Granovetter's theory of weak ties, which rests on the basis that having a broad range of contacts is most effective for job attainment. Structural holes have been widely applied in social network analysis, resulting in applications in a wide range of practical scenarios as well as machine learning-based social prediction.[50]

Research clusters

[edit]Art Networks

[edit]Research has used network analysis to examine networks created when artists are exhibited together in museum exhibition. Such networks have been shown to affect an artist's recognition in history and historical narratives, even when controlling for individual accomplishments of the artist.[51][52] Other work examines how network grouping of artists can affect an individual artist's auction performance.[53] An artist's status has been shown to increase when associated with higher status networks, though this association has diminishing returns over an artist's career.

Community

[edit]In J.A. Barnes' day, a "community" referred to a specific geographic location and studies of community ties had to do with who talked, associated, traded, and attended church with whom. Today, however, there are extended "online" communities developed through telecommunications devices and social network services. Such devices and services require extensive and ongoing maintenance and analysis, often using network science methods. Community development studies, today, also make extensive use of such methods.

Complex networks

[edit]Complex networks require methods specific to modelling and interpreting social complexity and complex adaptive systems, including techniques of dynamic network analysis. Mechanisms such as Dual-phase evolution explain how temporal changes in connectivity contribute to the formation of structure in social networks.

Conflict and Cooperation

[edit]The study of social networks is being used to examine the nature of interdependencies between actors and the ways in which these are related to outcomes of conflict and cooperation. Areas of study include cooperative behavior among participants in collective actions such as protests; promotion of peaceful behavior, social norms, and public goods within communities through networks of informal governance; the role of social networks in both intrastate conflict and interstate conflict; and social networking among politicians, constituents, and bureaucrats.[54]

Criminal networks

[edit]In criminology and urban sociology, much attention has been paid to the social networks among criminal actors. For example, murders can be seen as a series of exchanges between gangs. Murders can be seen to diffuse outwards from a single source, because weaker gangs cannot afford to kill members of stronger gangs in retaliation, but must commit other violent acts to maintain their reputation for strength.[55]

Diffusion of innovations

[edit]Diffusion of ideas and innovations studies focus on the spread and use of ideas from one actor to another or one culture and another. This line of research seeks to explain why some become "early adopters" of ideas and innovations, and links social network structure with facilitating or impeding the spread of an innovation. A case in point is the social diffusion of linguistic innovation such as neologisms. Experiments and large-scale field trials (e.g., by Nicholas Christakis and collaborators) have shown that cascades of desirable behaviors can be induced in social groups, in settings as diverse as Honduras villages,[56][57] Indian slums,[58] or in the lab.[59] Still other experiments have documented the experimental induction of social contagion of voting behavior,[60] emotions,[61] risk perception,[62] and commercial products.[63]

Demography

[edit]In demography, the study of social networks has led to new sampling methods for estimating and reaching populations that are hard to enumerate (for example, homeless people or intravenous drug users.) For example, respondent driven sampling is a network-based sampling technique that relies on respondents to a survey recommending further respondents.[64][65]

Economic sociology

[edit]The field of sociology focuses almost entirely on networks of outcomes of social interactions. More narrowly, economic sociology considers behavioral interactions of individuals and groups through social capital and social "markets". Sociologists, such as Mark Granovetter, have developed core principles about the interactions of social structure, information, ability to punish or reward, and trust that frequently recur in their analyses of political, economic and other institutions. Granovetter examines how social structures and social networks can affect economic outcomes like hiring, price, productivity and innovation and describes sociologists' contributions to analyzing the impact of social structure and networks on the economy.[66]

Health care

[edit]Analysis of social networks is increasingly incorporated into health care analytics, not only in epidemiological studies but also in models of patient communication and education, disease prevention, mental health diagnosis and treatment, and in the study of health care organizations and systems.[67]

Human ecology

[edit]Human ecology is an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary study of the relationship between humans and their natural, social, and built environments. The scientific philosophy of human ecology has a diffuse history with connections to geography, sociology, psychology, anthropology, zoology, and natural ecology.[68][69]

Literary networks

[edit]In the study of literary systems, network analysis has been applied by Anheier, Gerhards and Romo,[70] De Nooy,[71] Senekal,[72] and Lotker,[73] to study various aspects of how literature functions. The basic premise is that polysystem theory, which has been around since the writings of Even-Zohar, can be integrated with network theory and the relationships between different actors in the literary network, e.g. writers, critics, publishers, literary histories, etc., can be mapped using visualization from SNA.

Organizational studies

[edit]Research studies of formal or informal organization relationships, organizational communication, economics, economic sociology, and other resource transfers. Social networks have also been used to examine how organizations interact with each other, characterizing the many informal connections that link executives together, as well as associations and connections between individual employees at different organizations.[74] Many organizational social network studies focus on teams.[75] Within team network studies, research assesses, for example, the predictors and outcomes of centrality and power, density and centralization of team instrumental and expressive ties, and the role of between-team networks. Intra-organizational networks have been found to affect organizational commitment,[76] organizational identification,[37] interpersonal citizenship behaviour.[77]

Social capital

[edit]Social capital is a form of economic and cultural capital in which social networks are central, transactions are marked by reciprocity, trust, and cooperation, and market agents produce goods and services not mainly for themselves, but for a common good. Social capital is split into three dimensions: the structural, the relational and the cognitive dimension. The structural dimension describes how partners interact with each other and which specific partners meet in a social network. Also, the structural dimension of social capital indicates the level of ties among organizations.[78] This dimension is highly connected to the relational dimension which refers to trustworthiness, norms, expectations and identifications of the bonds between partners. The relational dimension explains the nature of these ties which is mainly illustrated by the level of trust accorded to the network of organizations.[78] The cognitive dimension analyses the extent to which organizations share common goals and objectives as a result of their ties and interactions.[78]

Social capital is a sociological concept about the value of social relations and the role of cooperation and confidence to achieve positive outcomes. The term refers to the value one can get from their social ties. For example, newly arrived immigrants can make use of their social ties to established migrants to acquire jobs they may otherwise have trouble getting (e.g., because of unfamiliarity with the local language). A positive relationship exists between social capital and the intensity of social network use.[79][80][81] In a dynamic framework, higher activity in a network feeds into higher social capital which itself encourages more activity.[79][82]

Advertising

[edit]This particular cluster focuses on brand-image and promotional strategy effectiveness, taking into account the impact of customer participation on sales and brand-image. This is gauged through techniques such as sentiment analysis which rely on mathematical areas of study such as data mining and analytics. This area of research produces vast numbers of commercial applications as the main goal of any study is to understand consumer behaviour and drive sales.

Network position and benefits

[edit]In many organizations, members tend to focus their activities inside their own groups, which stifles creativity and restricts opportunities. A player whose network bridges structural holes has an advantage in detecting and developing rewarding opportunities.[48] Such a player can mobilize social capital by acting as a "broker" of information between two clusters that otherwise would not have been in contact, thus providing access to new ideas, opinions and opportunities. British philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill, writes, "it is hardly possible to overrate the value of placing human beings in contact with persons dissimilar to themselves.... Such communication [is] one of the primary sources of progress."[83] Thus, a player with a network rich in structural holes can add value to an organization through new ideas and opportunities. This in turn, helps an individual's career development and advancement.

A social capital broker also reaps control benefits of being the facilitator of information flow between contacts. Full communication with exploratory mindsets and information exchange generated by dynamically alternating positions in a social network promotes creative and deep thinking.[84] In the case of consulting firm Eden McCallum, the founders were able to advance their careers by bridging their connections with former big three consulting firm consultants and mid-size industry firms.[85] By bridging structural holes and mobilizing social capital, players can advance their careers by executing new opportunities between contacts.

There has been research that both substantiates and refutes the benefits of information brokerage. A study of high tech Chinese firms by Zhixing Xiao found that the control benefits of structural holes are "dissonant to the dominant firm-wide spirit of cooperation and the information benefits cannot materialize due to the communal sharing values" of such organizations.[86] However, this study only analyzed Chinese firms, which tend to have strong communal sharing values. Information and control benefits of structural holes are still valuable in firms that are not quite as inclusive and cooperative on the firm-wide level. In 2004, Ronald Burt studied 673 managers who ran the supply chain for one of America's largest electronics companies. He found that managers who often discussed issues with other groups were better paid, received more positive job evaluations and were more likely to be promoted.[48] Thus, bridging structural holes can be beneficial to an organization, and in turn, to an individual's career.

Social media

[edit]Computer networks combined with social networking software produce a new medium for social interaction. A relationship over a computerized social networking service can be characterized by context, direction, and strength. The content of a relation refers to the resource that is exchanged. In a computer-mediated communication context, social pairs exchange different kinds of information, including sending a data file or a computer program as well as providing emotional support or arranging a meeting. With the rise of electronic commerce, information exchanged may also correspond to exchanges of money, goods or services in the "real" world.[87] Social network analysis methods have become essential to examining these types of computer mediated communication.

In addition, the sheer size and the volatile nature of social media has given rise to new network metrics. A key concern with networks extracted from social media is the lack of robustness of network metrics given missing data.[88]

Segregation

[edit]Based on the pattern of homophily, ties between people are most likely to occur between nodes that are most similar to each other, or within neighbourhood segregation, individuals are most likely to inhabit the same regional areas as other individuals who are like them. Therefore, social networks can be used as a tool to measure the degree of segregation or homophily within a social network. Social Networks can both be used to simulate the process of homophily but it can also serve as a measure of level of exposure of different groups to each other within a current social network of individuals in a certain area.[89]

See also

[edit]- Bibliography of sociology

- Blockmodeling – Analytical method for social structure

- Business networking – Sharing of information or services between people, companies or groups

- Collective network – Social groups linked by a common bond

- International Network for Social Network Analysis – Professional academic association

- Network science – Academic field

- Network society – Concept in sociology

- Network theory – Study of graphs as a representation of relations between discrete objects

- Scientific collaboration network

- Semiotics of social networking – Study of symbols and signs in social settings

- Social graph – Graph representing social relations

- Social network (sociolinguistics) – Structure of a speech community

- Social network analysis – Analysis of social structures using network and graph theory

- Social networking service – Online platform that facilitates the building of relations

- Social web – Social relations over the World Wide Web

- Structural fold – Cohesive group whose membership overlaps with that of another cohesive group

References

[edit]- ^ a b Wasserman, Stanley; Faust, Katherine (1994). "Social Network Analysis in the Social and Behavioral Sciences". Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN 978-0-521-38707-1.

- ^ Scott, W. Richard; Davis, Gerald F. (2003). "Networks In and Around Organizations". Organizations and Organizing. Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-195893-7.

- ^ Freeman, Linton (2004). The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Empirical Press. ISBN 978-1-59457-714-7.

- ^ Borgatti, Stephen P.; Mehra, Ajay; Brass, Daniel J.; Labianca, Giuseppe (2009). "Network Analysis in the Social Sciences". Science. 323 (5916): 892–895. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..892B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.536.5568. doi:10.1126/science.1165821. PMID 19213908. S2CID 522293.

- ^ Easley, David; Kleinberg, Jon (2010). "Overview". Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-0-521-19533-1.

- ^ a b c Scott, John P. (2000). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- ^ Tönnies, Ferdinand (1887). Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, Leipzig: Fues's Verlag. (Translated, 1957 by Charles Price Loomis as Community and Society, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.)

- ^ Durkheim, Emile (1893). De la division du travail social: étude sur l'organisation des sociétés supérieures, Paris: F. Alcan. (Translated, 1964, by Lewis A. Coser as The Division of Labor in Society, New York: Free Press.)

- ^ Simmel, Georg (1908). Soziologie, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

- ^ For a historical overview of the development of social network analysis, see: Carrington, Peter J.; Scott, John (2011). "Introduction". The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis. Sage. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84787-395-8.

- ^ See also the diagram in Scott, John (2000). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. Sage. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7619-6339-4.

- ^ Malinowski, Bronislaw (1913). The Family Among the Australian Aborigines: A Sociological Study. London: University of London Press.

- ^ Radcliffe-Brown, Alfred Reginald (1930) The social organization of Australian tribes. Sydney, Australia: University of Sydney Oceania monographs, No.1.

- ^ Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (1940). "On social structure". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 70 (1): 1–12. doi:10.2307/2844197. JSTOR 2844197.

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude ([1947]1967). Les structures élémentaires de la parenté. Paris: La Haye, Mouton et Co. (Translated, 1969 by J. H. Bell, J. R. von Sturmer, and R. Needham, 1969, as The Elementary Structures of Kinship, Boston: Beacon Press.)

- ^ Barnes, John (1954). "Class and Committees in a Norwegian Island Parish". Human Relations, (7): 39–58.

- ^ Freeman, Linton C.; Wellman, Barry (1995). "A note on the ancestral Toronto home of social network analysis". Connections. 18 (2): 15–19.

- ^ Savage, Mike (2008). "Elizabeth Bott and the formation of modern British sociology". The Sociological Review. 56 (4): 579–605. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954x.2008.00806.x. S2CID 145286556.

- ^ Nadel, S. F. 1957. The Theory of Social Structure. London: Cohen and West.

- ^ Parsons, Talcott ([1937] 1949). The Structure of Social Action: A Study in Social Theory with Special Reference to a Group of European Writers. New York: The Free Press.

- ^ Parsons, Talcott (1951). The Social System. New York: The Free Press.

- ^ Blau, Peter (1956). Bureaucracy in Modern Society. New York: Random House, Inc.

- ^ Blau, Peter (1960). "A Theory of Social Integration". The American Journal of Sociology, (65)6: 545–556, (May).

- ^ Blau, Peter (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life.

- ^ Bernie Hogan. "The Networked Individual: A Profile of Barry Wellman". Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- ^ a b Granovetter, Mark (2007). "Introduction for the French Reader". Sociologica. 2: 1–8.

- ^ Wellman, Barry (1988). "Structural analysis: From method and metaphor to theory and substance". pp. 19–61 in B. Wellman and S. D. Berkowitz (eds.) Social Structures: A Network Approach, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Mullins, Nicholas. Theories and Theory Groups in Contemporary American Sociology. New York: Harper and Row, 1973.

- ^ Tilly, Charles, ed. An Urban World. Boston: Little Brown, 1974.

- ^ Wellman, Barry. 1988. "Structural Analysis: From Method and Metaphor to Theory and Substance". pp. 19–61 in Social Structures: A Network Approach, edited by Barry Wellman and S. D. Berkowitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Nagler, Jan; Anna Levina; Marc Timme (2011). "Impact of single links in competitive percolation". Nature Physics. 7 (3): 265–270. arXiv:1103.0922. Bibcode:2011NatPh...7..265N. doi:10.1038/nphys1860. S2CID 2809783.

- ^ Newman, Mark, Albert-László Barabási and Duncan J. Watts (2006). The Structure and Dynamics of Networks (Princeton Studies in Complexity). Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Wellman, Barry (2008). "Review: The development of social network analysis: A study in the sociology of science". Contemporary Sociology. 37 (3): 221–222. doi:10.1177/009430610803700308. S2CID 140433919.

- ^ Wasserman, Stanley; Faust, Katherine (1998). Social network analysis: methods and applications (Reprint. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38269-4.

- ^ a b Kadushin, C. (2012). Understanding social networks: Theories, concepts, and findings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Granovetter, M. (1976). "Network sampling: Some first steps". American Journal of Sociology. 81 (6): 1287–1303. doi:10.1086/226224. S2CID 40359730.

- ^ a b Jones, C.; Volpe, E.H. (2011). "Organizational identification: Extending our understanding of social identities through social networks". Journal of Organizational Behavior. 32 (3): 413–434. doi:10.1002/job.694.

- ^ de Nooy, Wouter (2012). "Social Network Analysis, Graph Theoretical Approaches to". Computational Complexity. Springer. pp. 2864–2877. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-1800-9_176. ISBN 978-1-4614-1800-9.

- ^ Hedström, Peter; Sandell, Rickard; Stern, Charlotta (2000). "Mesolevel Networks and the Diffusion of Social Movements: The Case of the Swedish Social Democratic Party" (PDF). American Journal of Sociology. 106 (1): 145–172. doi:10.1086/303109. hdl:10016/34606. S2CID 3609428. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-02-26.

- ^ a b Riketta, M.; Nienber, S. (2007). "Multiple identities and work motivation: The role of perceived compatibility between nested organizational units". British Journal of Management. 18: S61–77. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00526.x. S2CID 144857162.

- ^ Shirado, Hirokazu; Christakis, Nicholas A (2017). "Locally noisy autonomous agents improve global human coordination in network experiments". Nature. 545 (7654): 370–374. Bibcode:2017Natur.545..370S. doi:10.1038/nature22332. PMC 5912653. PMID 28516927.

- ^ Cranmer, Skyler J.; Desmarais, Bruce A. (2011). "Inferential Network Analysis with Exponential Random Graph Models". Political Analysis. 19 (1): 66–86. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.623.751. doi:10.1093/pan/mpq037.

- ^ Moreira, André A.; Demétrius R. Paula; Raimundo N. Costa Filho; José S. Andrade Jr. (2006). "Competitive cluster growth in complex networks". Physical Review E. 73 (6) 065101. arXiv:cond-mat/0603272. Bibcode:2006PhRvE..73f5101M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.73.065101. PMID 16906890. S2CID 45651735.

- ^ Barabási, Albert-László (2003). Linked: how everything is connected to everything else and what it means for business, science, and everyday life. New York: Plum.

- ^ Strogatz, Steven H. (2001). "Exploring complex networks". Nature. 410 (6825): 268–276. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..268S. doi:10.1038/35065725. PMID 11258382.

- ^ Kilduff, M.; Tsai, W. (2003). Social networks and organisations. Sage Publications.

- ^ Granovetter, M. (1973). "The strength of weak ties". American Journal of Sociology. 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469. S2CID 59578641.

- ^ a b c Burt, Ronald (2004). "Structural Holes and Good Ideas". American Journal of Sociology. 110 (2): 349–399. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.388.2251. doi:10.1086/421787. S2CID 2152743.

- ^ a b c d Burt, Ronald (1992). Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Lin, Zihang; Zhang, Yuwei; Gong, Qingyuan; Chen, Yang; Oksanen, Atte; Ding, Aaron Yi (2022). "Structural Hole Theory in Social Network Analysis: A Review" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems. 9 (3): 724–739. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2021.3070321.

- ^ Braden, L.E.A.; Teekens, Thomas (2020-08-01). "Historic networks and commemoration: Connections created through museum exhibitions". Poetics. 81 101446. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101446. hdl:1765/127209. ISSN 0304-422X.

- ^ Braden, L. E. A. (2021-01-01). "Networks Created Within Exhibition: The Curators' Effect on Historical Recognition". American Behavioral Scientist. 65 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1177/0002764218800145. ISSN 0002-7642.

- ^ Braden, L. E. A.; Teekens, Thomas (September 2019). "Reputation, Status Networks, and the Art Market". Arts. 8 (3): 81. doi:10.3390/arts8030081. hdl:1765/119341.

- ^ Larson, Jennifer M. (11 May 2021). "Networks of Conflict and Cooperation". Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 89–107. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102523.

- ^ Papachristos, Andrew (2009). "Murder by Structure: Dominance Relations and the Social Structure of Gang Homicide" (PDF). American Journal of Sociology. 115 (1): 74–128. doi:10.2139/ssrn.855304. PMID 19852186. S2CID 24605697. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ Kim, David A.; Hwong, Alison R.; Stafford, Derek; Hughes, D. Alex; O'Malley, A. James; Fowler, James H.; Christakis, Nicholas A. (2015-07-11). "Social network targeting to maximise population behaviour change: a cluster randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 386 (9989): 145–153. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60095-2. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC 4638320. PMID 25952354.

- ^ Airoldi, Edoardo M.; Christakis, Nicholas A. (2024-05-03). "Induction of social contagion for diverse outcomes in structured experiments in isolated villages". Science. 384 (6695) eadi5147. Bibcode:2024Sci...384i5147A. doi:10.1126/science.adi5147. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 38696582.

- ^ Alexander, Marcus; Forastiere, Laura; Gupta, Swati; Christakis, Nicholas A. (2022-07-26). "Algorithms for seeding social networks can enhance the adoption of a public health intervention in urban India". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (30) e2120742119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11920742A. doi:10.1073/pnas.2120742119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9335263. PMID 35862454.

- ^ Fowler, James H.; Christakis, Nicholas A. (2010). "Cooperative behavior cascades in human social networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (12): 5334–5338. arXiv:0908.3497. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5334F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913149107. PMC 2851803. PMID 20212120.

- ^ Bond, RM; Fariss, CJ; Jones, JJ; Kramer, ADI; Marlow, C; Settle, JE; Fowler, JH (2012). "A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization". Nature. 489 (7415): 295–298. Bibcode:2012Natur.489..295B. doi:10.1038/nature11421. PMC 3834737. PMID 22972300.

- ^ Kramer, ADI; Guillory, JE; Hancock, JT (2014). "Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (24): 8788–8790. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.8788K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320040111. PMC 4066473. PMID 24889601.

- ^ Moussaid, M; Brighton, H; Gaissmaier, W (2015). "The amplification of risk in experimental diffusion chains" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (18): 5631–5636. arXiv:1504.05331. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5631M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421883112. PMC 4426405. PMID 25902519.

- ^ Aral, Sinan; Walker, Dylan (2011). "Creating Social Contagion Through Viral Product Design: A Randomized Trial of Peer Influence in Networks". Management Science. 57 (9): 1623–1639. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1110.1421.

- ^ Gile, Krista J.; Beaudry, Isabelle S.; Handcock, Mark S.; Ott, Miles Q. (7 March 2018). "Methods for Inference from Respondent-Driven Sampling Data". Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application. 5 (1): 65–93. Bibcode:2018AnRSA...5...65G. doi:10.1146/annurev-statistics-031017-100704. S2CID 67695078. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Heckathorn, Douglas D.; Cameron, Christopher J. (31 July 2017). "Network Sampling: From Snowball and Multiplicity to Respondent-Driven Sampling". Annual Review of Sociology. 43 (1): 101–119. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053556.

- ^ Granovetter, Mark (2005). "The Impact of Social Structure on Economic Outcomes". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 19 (1): 33–50. doi:10.1257/0895330053147958. JSTOR 4134991. S2CID 263519132.

- ^ Levy, Judith and Bernice Pescosolido (2002). Social Networks and Health. Boston, MA: JAI Press.

- ^ Crona, Beatrice and Klaus Hubacek (eds.) (2010). "Special Issue: Social network analysis in natural resource governance" Archived 2012-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. Ecology and Society, 48.

- ^ Ernstson, Henrich (2010). "Reading list: Using social network analysis (SNA) in social-ecological studies". Resilience Science Archived 2012-04-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Anheier, H. K.; Romo, F. P. (1995). "Forms of capital and social structure of fields: examining Bourdieu's social topography". American Journal of Sociology. 100 (4): 859–903. doi:10.1086/230603. S2CID 143587142.

- ^ De Nooy, W (2003). "Fields and networks: Correspondence analysis and social network analysis in the framework of Field Theory". Poetics. 31 (5–6): 305–327. doi:10.1016/S0304-422X(03)00035-4.

- ^ Senekal, B. A. (2012). "Die Afrikaanse literêre sisteem: ʼn Eksperimentele benadering met behulp van Sosiale-netwerk-analise (SNA)". LitNet Akademies. 9: 3.

- ^ Lotker, Zvi (2021), "Machine Narrative", Analyzing Narratives in Social Networks, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 283–298, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68299-6_18, ISBN 978-3-030-68298-9, S2CID 241976819

- ^ Podolny, J. M.; Baron, J. N. (1997). "Resources and relationships: Social networks and mobility in the workplace". American Sociological Review. 62 (5): 673–693. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.114.6822. doi:10.2307/2657354. JSTOR 2657354.

- ^ Park, Semin; Grosser, Travis J.; Roebuck, Adam A.; Mathieu, John E. (3 February 2020). "Understanding Work Teams From a Network Perspective: A Review and Future Research Directions". Journal of Management. 46 (6): 1002–1028. doi:10.1177/0149206320901573.

- ^ Lee, J.; Kim, S. (2011). "Exploring the role of social networks in affective organizational commitment: Network centrality, strength of ties, and structural holes". The American Review of Public Administration. 41 (2): 205–223. doi:10.1177/0275074010373803. S2CID 145641976.

- ^ Bowler, W. M.; Brass, D. J. (2011). "Relational correlates of interpersonal citizenship behaviour: A social network perspective". Journal of Applied Psychology. 91 (1): 70–82. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.516.8746. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.70. PMID 16435939.

- ^ a b c (Claridge, 2018).

- ^ a b Koley, Gaurav; Deshmukh, Jayati; Srinivasa, Srinath (2020). "Social Capital as Engagement and Belief Revision". In Aref, Samin; Bontcheva, Kalina; Braghieri, Marco; Dignum, Frank; Giannotti, Fosca; Grisolia, Francesco; Pedreschi, Dino (eds.). Social Informatics. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 12467. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 137–151. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-60975-7_11. ISBN 978-3-030-60975-7. S2CID 222233101. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-09.

- ^ Sebastián, Valenzuela; Namsu Park; Kerk F. Kee (2009). "Is There Social Capital in a Social Network Site? Facebook Use and College Students' Life Satisfaction, Trust, and Participation". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 14 (4): 875–901. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01474.x.

- ^ Wang, Hua & Barry Wellman (2010). "Social Connectivity in America: Changes in Adult Friendship Network Size from 2002 to 2007". American Behavioral Scientist. 53 (8): 1148–1169. doi:10.1177/0002764209356247. S2CID 144525876.

- ^ Gaudeul, Alexia; Giannetti, Caterina (2013). "The role of reciprocation in social network formation, with an application to LiveJournal". Social Networks. 35 (3): 317–330. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2013.03.003. ISSN 0378-8733.

- ^ Mill, John (1909). Principles of Political Economy. Library of Economics and Liberty: William J Ashley.

- ^ Csermely, Peter (July 2017). "The Network Concept of Creativity and Deep Thinking: Applications to Social Opinion Formation and Talent Support". Gifted Child Quarterly. 61 (3): 194–201. arXiv:1702.06342. doi:10.1177/0016986217701832. ISSN 0016-9862. S2CID 14419926.

- ^ Gardner, Heidi; Eccles, Robert (2011). "Eden McCallum: A Network Based Consulting Firm". Harvard Business School Review.

- ^ Xiao, Zhixing; Tsui, Anne (2007). "When Brokers May Not Work: The Cultural Contingency of Social Archived 2016-09-14 at the Wayback Machine Capital in Chinese High-tech Firms". Administrative Science Quarterly.

- ^ Garton, Laura; Haythornthwaite, Caroline; Wellman, Barry (23 June 2006). "Studying Online Social Networks". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 3 (1): 0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00062.x. S2CID 29051307.

- ^ Wei, Wei; Joseph, Kenneth; Liu, Huan; Carley, Kathleen M. (2016). "Exploring Characteristics of Suspended Users and Network Stability on Twitter". Social Network Analysis and Mining. 6: 51. doi:10.1007/s13278-016-0358-5. S2CID 18520393.

- ^ Bojanowski, Michał; Corten, Rense (2014-10-01). "Measuring segregation in social networks". Social Networks. 39: 14–32. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2014.04.001. ISSN 0378-8733.

Further reading

[edit]- Aneja, Nagender; Gambhir, Sapna (August 2013). "Ad-hoc Social Network: A Comprehensive Survey" (PDF). International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 4 (8): 156–160. ISSN 2229-5518.

- Barabási, Albert-László (2003). Linked: How Everything Is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life. Plum. ISBN 978-0-452-28439-5.

- Barnett, George A. (2011). Encyclopedia of Social Networks. Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-7911-5.

- Estrada, E (2011). The Structure of Complex Networks: Theory and Applications. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-59175-6.

- Ferguson, Niall (2018). The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, from the Freemasons to Facebook. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0-7352-2291-5.

- Freeman, Linton C. (2004). The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Empirical Press. ISBN 978-1-59457-714-7.

- Kadushin, Charles (2012). Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts, and Findings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537946-4.

- Mauro, Rios; Petrella, Carlos (2014). La Quimera de las Redes Sociales [The Chimera of Social Networks] (in Spanish). Bubok España. ISBN 978-9974-99-637-3.

- Rainie, Lee; Wellman, Barry (2012). Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01719-0.

- Scott, John (1991). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. Sage. ISBN 978-0-7619-6338-7.

- Wasserman, Stanley; Faust, Katherine (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38269-4.

- Wellman, Barry; Berkowitz, S. D. (1988). Social Structures: A Network Approach. Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24441-1.

External links

[edit]Organizations

[edit]Peer-reviewed journals

[edit]- Social Networks

- Network Science

- Journal of Social Structure

- Journal of Mathematical Sociology

- Social Network Analysis and Mining (SNAM)

- "INSNA – Connections Journal". Connections Bulletin of the International Network for Social Network Analysis. Toronto: International Network for Social Network Analysis. ISSN 0226-1766. Archived from the original on 2013-07-18.

Textbooks and educational resources

[edit]- Networks, Crowds, and Markets (2010) by D. Easley & J. Kleinberg

- Introduction to Social Networks Methods (2005) by R. Hanneman & M. Riddle

- Social Network Analysis Instructional Web Site by S. Borgatti

- Guide for virtual social networks for public administrations (2015) by Mauro D. Ríos (in Spanish)

Data sets

[edit]Social network

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

A social network is a structure comprising social actors, such as individuals or organizations, interconnected by ties that represent relationships or interactions of varying types and strengths.[9][10] These ties may encompass personal friendships, professional collaborations, kinship bonds, or informational exchanges, forming patterns that influence behavior, resource flow, and social dynamics.[11] The concept emphasizes relational data over isolated attributes of actors, viewing social phenomena as emerging from network configurations rather than individual traits alone.[12] The scope of social network analysis (SNA) extends to mapping, measuring, and interpreting these structures using quantitative methods derived from graph theory and sociology.[8] SNA quantifies properties such as node centrality (measuring an actor's influence or connectivity), density (proportion of possible ties realized), and clustering (tendency for connected actors to form dense subgroups), enabling empirical assessment of how networks facilitate processes like diffusion of innovations or propagation of attitudes.[13] Applications span disciplines including sociology, where it elucidates community formation and inequality; organizational studies, analyzing collaboration and power; and health sciences, tracking disease spread or support systems.[11][14] While contemporary digital platforms exemplify large-scale social networks, the framework predates computing and applies broadly to any interdependent social system, from historical trade routes to modern supply chains.[15] SNA distinguishes itself by prioritizing structural invariants—enduring patterns like small-world properties or scale-free distributions—over transient content, providing a causal lens for understanding why certain networks exhibit resilience or fragility.[16] This analytical paradigm contrasts with traditional variable-based approaches, insisting that social outcomes arise from positional embeddedness within relational webs.[17]Core Concepts and Terminology

In social network analysis, a social network consists of nodes (also termed actors or vertices) representing discrete entities such as individuals, organizations, or groups, connected by edges (also called ties or links) that denote relationships or interactions between them.[18] These structures are formally modeled using graph theory, where a graph has as the set of vertices and as the set of edges.[19] Edges may be undirected, indicating symmetric relations like mutual friendships, or directed, capturing asymmetric ones such as one-way citations or follows.[20] Key structural properties include network density, defined as the ratio of observed ties to the maximum possible ties in the network; for an undirected simple graph with nodes, this is , measuring overall connectedness.[8] The clustering coefficient quantifies local density by assessing how often a node's neighbors are connected to each other; the local version for a node is the fraction of possible triangles formed by it and its neighbors, ranging from 0 (no clustering) to 1 (complete clustering), while the global coefficient averages this across nodes. Centrality measures evaluate a node's prominence within the network. Degree centrality counts direct connections, with in-degree and out-degree for directed graphs.[21] Closeness centrality gauges average shortest path distance to all other nodes, favoring those with efficient reach.[22] Betweenness centrality sums the proportion of shortest paths between all node pairs passing through a given node, highlighting brokers or gatekeepers.[23] Eigenvector centrality weights connections by the centrality of neighbors, emphasizing ties to influential nodes.[21] These metrics, rooted in empirical network data, reveal positional advantages without assuming inherent actor traits.[24]Historical Development

Early Influences and Precursors

Georg Simmel's sociological inquiries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries provided foundational insights into social structures that anticipated network analysis. In works such as Soziologie (1908), Simmel examined the "forms" of association—distinguishing them from content—focusing on how dyadic (two-person) and triadic (three-person) interactions generated emergent properties like competition, alliance, or mediation.[25][26] He argued that increasing group size quantitatively alters relational dynamics: larger circles expand individual choices but weaken personal bonds, fostering overlapping "webs" of affiliation that constrain or enable agency.[26][27] Simmel's formal sociology treated society as a configuration of intersecting social circles, where positions derive meaning from patterns of connectivity rather than isolated attributes.[28] This approach prefigured network theory by prioritizing relational geometry—such as the effects of "tertius gaudens" (third-party gains in triads)—over individualistic or normative explanations, influencing later quantifications of tie strength and centrality.[26][28] Émile Durkheim's emphasis on interconnectedness as the basis for social cohesion, as in The Division of Labor in Society (1893), complemented these ideas by highlighting mechanical and organic solidarity emerging from collective ties, though Durkheim focused more on aggregate densities than discrete structures.[25] Early anthropological kinship mappings, such as Lewis Henry Morgan's diagrammatic classifications in Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity (1871), visually represented descent and marriage alliances as linked entities, laying groundwork for relational visualization without formal metrics.[29] These precursors shifted attention from isolated actors to interdependent configurations, setting the stage for 20th-century operationalization.[30]Formalization in the 20th Century

The formalization of social network concepts in the 20th century originated with Jacob L. Moreno's development of sociometry in the 1930s. In his 1934 book Who Shall Survive?, Moreno introduced sociograms as graphical representations of social relations, depicting individuals as nodes and directed choices (e.g., friendships or preferences) as edges; an early application analyzed selections among 435 girls at the Hudson School for Girls, quantifying group attractions and repulsions.[30] This approach provided the first systematic method for visualizing and measuring interpersonal ties, influencing fields like group psychotherapy.[31] Mid-century advancements incorporated mathematical graph theory into sociological analysis. Anthropologist J.A. Barnes coined the term "social network" in 1954 to describe extended patterns of personal ties cutting across formal structures, as observed in a Norwegian island parish study involving class and committee memberships.[32] Mathematician Anatol Rapoport applied graph-theoretic models to social structures in the late 1940s and 1950s, developing probabilistic analyses of random nets, including cycle distributions and connectivity biases.[33] Complementing this, Fritz Heider's 1946 balance theory for dyadic and triadic signed relations was extended by Dorwin Cartwright and Frank Harary in 1956 through explicit graph formulations, enabling predictions of structural stability based on path signs.[30] The 1960s and 1970s saw further mathematical rigor with algebraic and computational methods. Harrison White, leading the Harvard social networks group, pioneered blockmodeling to capture role structures via equivalence classes of actors with similar ties; this culminated in the 1971 CONCOR algorithm co-developed with François Lorrain for iterative partitioning of relational matrices into blocks.[34] These innovations formalized network positions and subsystems, facilitating quantitative metrics like centrality and density, and establishing social network analysis as a distinct paradigm blending sociology with formal mathematics.[35]Expansion with Computational Methods

The integration of computational methods into social network analysis during the late 20th century transformed the field by enabling the processing of larger datasets and the execution of complex algorithms infeasible with manual techniques. In the 1950s and 1960s, early adopters utilized mainframe computers to apply graph theory, computing metrics like path lengths and clustering coefficients from adjacency matrices representing social ties.[30] This shift allowed quantitative validation of hypotheses about information flow and influence in groups, building on experimental studies of communication structures.[36] By the 1970s, algorithmic advancements facilitated structural analyses such as blockmodeling, introduced by Harrison White, Ronald Burt, and others, which employed iterative partitioning to identify role equivalences based on tie patterns. These computations, reliant on matrix reductions and optimization routines, revealed systemic patterns in datasets previously limited to qualitative scrutiny.[37] Concurrently, centrality measures—degree, closeness, and betweenness—were formalized and implemented computationally by Linton Freeman, quantifying node positions in networks with empirical precision.[38] Dedicated software emerged in the 1980s, with UCINET, developed by Freeman and colleagues from 1981 onward, providing tools for eigenvalue-based centrality, Q-analysis, and network visualization via punch-card and later disk-based inputs.[39] This package processed matrices up to hundreds of nodes, supporting permutation tests for significance and expanding applications to organizational and community studies. By the 1990s, tools like Pajek (1996) handled thousands of vertices, incorporating layout algorithms and community detection for scale-free and small-world simulations.[25] Computational simulations proliferated, modeling network growth via preferential attachment as in the Barabási–Albert algorithm (1999), which generated power-law degree distributions matching real-world observations through iterative node additions and stochastic edge formations. These methods, grounded in Monte Carlo techniques, tested causal mechanisms of emergence, bridging theoretical sociology with physics-inspired modeling.[40] Such expansions underscored computation's role in causal inference, revealing how local rules yield global structures without relying on biased narrative interpretations.Levels of Analysis

Micro Level: Individuals and Ties

In social network analysis, the micro level examines individual actors and the dyadic ties connecting them, forming the foundational units of networks. Actors, often individuals, are modeled as nodes, while ties represent interpersonal relations such as friendships, kinships, or professional collaborations, depicted as edges in graph theory. These ties can be undirected (mutual, like friendship) or directed (asymmetric, like influence), binary (existence only) or weighted (by frequency or intensity).[8][41] Tie strength, a key micro-level attribute, combines dimensions including time spent together, emotional intensity, intimacy, and reciprocal services, as defined by Granovetter in 1973. Strong ties, characterized by frequent interaction and closeness, foster emotional support and resource sharing within dense clusters but often convey redundant information due to overlapping contacts. Weak ties, conversely, link disparate groups, facilitating access to novel information and opportunities; Granovetter's empirical study of 282 professional, technical, and managerial workers in a Boston suburb found that among 56 job placements via personal contacts, weak ties accounted for 55.6% of successful referrals, compared to 27.8% from strong ties, underscoring their role in bridging structural holes.[42][43] Homophily, the tendency for ties to form between similar actors, operates prominently at the micro level, structuring dyadic connections by attributes like race, ethnicity, age, education, and values. McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook's 2001 review of empirical studies revealed robust status homophily, such as U.S. adults having over 90% same-race close friends and workplace advice networks showing 80-90% racial similarity; value homophily, driven by induced effects from socialization and choice-based selection, reinforces these patterns, limiting cross-group exposure while stabilizing intra-group norms. This principle arises from baseline propinquity (proximity-induced similarity) and endogenous feedback, with evidence from longitudinal data indicating induced homophily grows over time in marriages and friendships.[44] Multiplexity, where ties encompass multiple relation types (e.g., coworker and friend), enhances strength and durability at the individual level, as multiplex relations correlate with higher reciprocity and longevity than uniplex ones. Empirical analyses of communication data confirm that tie strength predicts interaction persistence, with temporal patterns like recency and frequency serving as proxies; for instance, studies of mobile phone records show strong ties exhibit higher call volume and duration, while weak ties sustain bridging functions over longer intervals. Ego-centric network approaches, focusing on an individual's alters and their interconnections, reveal how personal tie configurations influence outcomes like social capital, with denser egos benefiting from cohesion but risking insularity.[45][46]Meso Level: Groups and Substructures

The meso level of social network analysis examines intermediate structures between individual dyads and the overall network, focusing on groups, clusters, and subgraphs that exhibit denser internal connections compared to the broader system.[47] These substructures include cliques, where every node is directly connected to every other node within the subgroup, and communities, which are partitions of nodes with high intra-group density and low inter-group ties.[48] Such formations reveal how actors aggregate into cohesive units that influence behavior, information flow, and resource distribution within larger networks.[49] Key substructures at the meso level encompass cliques and their generalizations, such as n-cliques, which allow for limited path distances up to n between non-adjacent members, accommodating real-world imperfections in complete connectivity.[47] Communities, often identified through modularity optimization, represent emergent groupings where ties are disproportionately concentrated internally, as seen in empirical studies of adolescent peer networks where cliques correlate with shared activities and risk behaviors.[50] Structural equivalence positions, another meso construct, group actors with similar connection patterns to others, independent of direct ties, enabling analysis of role-based substructures like departmental clusters in organizations.[8] Detection of these substructures relies on algorithms tailored to uncover partitions maximizing internal cohesion. The Louvain method, introduced in 2008, iteratively optimizes modularity by merging communities based on density gains, proving effective in large-scale social networks like collaboration graphs.[48] Infomap employs information theory to compress network descriptions via flow modeling, identifying communities as modules that minimize description length, with applications demonstrating superior performance in directed networks.[51] Walktrap, utilizing random walks to measure node similarity, clusters based on structural proximity, revealing meso-level patterns in dynamic settings such as evolving friendship ties.[48] Empirical validation across datasets, including email and co-authorship networks, shows these methods recover ground-truth communities with adjusted Rand indices often exceeding 0.7 in benchmark tests.[52] Meso-level analysis highlights causal roles of substructures in network dynamics; for instance, cliques can amplify influence diffusion within bounded groups, while bridging substructures facilitate cross-community ties, as evidenced in studies of social mobility where early meso-structure insight predicts hierarchical ascent.[53] In organizational contexts, persistent subgroups correlate with innovation silos or coordination failures, underscoring the need for meso-aware interventions.[54] These insights derive from rigorous computational validations, prioritizing algorithmic robustness over subjective interpretations.[55]Macro Level: Systemic Patterns

Macro-level analysis of social networks examines the overall topology and emergent properties of entire systems, revealing patterns that arise from the aggregation of micro-level ties. Empirical studies consistently find that social networks display heterogeneous degree distributions, where a minority of nodes (hubs) possess disproportionately high connectivity while most nodes have few links. For instance, analyses of collaboration networks, friendship graphs, and online platforms show power-law-like tails in degree distributions, though rigorous statistical tests indicate that pure power-laws fit fewer than 5% of real-world networks, with truncated power-laws, log-normals, or exponential cutoffs often providing better descriptions due to finite size effects and growth constraints.[56][57] This heterogeneity contributes to systemic inequality in influence and information access, as hubs dominate flows of resources, ideas, and contagions across the network.[57] A defining systemic pattern is the small-world effect, where networks maintain short average path lengths—typically logarithmic in network size—despite sparse connections, enabling rapid transmission between distant nodes. This property, first empirically demonstrated in Stanley Milgram's 1967 letter-forwarding experiment involving 296 starters and targets in the U.S., yielded a median chain length of approximately 5 degrees of separation, far shorter than random expectations.[58] Subsequent computational models, such as the Watts-Strogatz rewiring process starting from regular lattices, replicate this by balancing high local clustering coefficients (often 0.1-0.6 in social data) with global efficiency, contrasting with the low clustering in random graphs.[59] In large-scale social datasets, like email or co-authorship networks exceeding 10^5 nodes, geodesic distances average 3-6, underscoring causal resilience to disconnection through intermediate paths.[60] Social networks also exhibit assortativity patterns that shape systemic stability and segregation. By degree, they tend toward disassortativity, with high-degree hubs linking preferentially to low-degree peripherals, enhancing network robustness to random failures but vulnerability to targeted hub attacks—as simulated in models where removing 5-10% of hubs fragments the graph.[61] Conversely, assortative mixing prevails for attributes like demographics or interests, where similar nodes cluster, measured by positive assortativity coefficients (r > 0.2-0.5) in datasets from friendship ties or online communities; this fosters modular substructures but can amplify echo chambers and polarization in information diffusion.[61] These patterns emerge dynamically from preferential attachment during growth, where new nodes connect disproportionately to popular ones, yielding scale-invariant structures over time, as observed in longitudinal studies of platforms like arXiv collaborations from 1995-2010.[62] Overall, such macro configurations reflect causal mechanisms of homophily and cumulative advantage, driving inequality and efficiency in real systems without assuming idealized scale-freeness.[63]Theoretical Foundations

Imported Theories

Social network analysis incorporates foundational concepts from graph theory, a branch of mathematics developed independently of social sciences. Graph theory models social structures as consisting of vertices (representing actors) and edges (representing ties), enabling the quantification of properties such as connectivity and paths. This framework, originating with Leonhard Euler's 1736 solution to the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem, was adapted for social applications through random graph models by Paul Erdős and Alfréd Rényi in 1959–1960, which assume uniform probability of ties to simulate network formation.[64][65] From psychology, structural balance theory, proposed by Fritz Heider in 1946, has been imported to explain preferences for congruent relational triads in signed networks (e.g., positive or negative ties). Heider's principle—that "the friend of my friend is my friend" or "the enemy of my enemy is my friend" yields balance—posits cognitive drives toward tension reduction, formalized mathematically by Cartwright and Harary in 1956 using graph-theoretic conditions for global balance. Empirical tests in social contexts, such as international relations or interpersonal conflicts, reveal partial adherence, with deviations attributed to network scale and dynamics rather than strict psychological universality.[66][67] Epidemiological diffusion models, rooted in public health and mathematics, inform the study of information, behavior, and influence spread in networks. The susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) framework, developed by Kermack and McKendrick in 1927 for disease propagation, treats adoption as contagious processes where tie exposure probability drives cascades, as seen in threshold models by Granovetter (though indigenous extensions exist). Applications to social contagion, such as innovation uptake, demonstrate that network topology—e.g., high-degree nodes accelerating spread—moderates diffusion rates beyond individual traits.[68] Physics-inspired theories, including small-world and scale-free models, have been adapted to capture empirical social network features. The Watts-Strogatz model (1998) interpolates between regular lattices and random graphs to explain short average path lengths (six degrees of separation) alongside local clustering, validated in datasets like actor collaborations. Similarly, the Barabási–Albert preferential attachment mechanism (1999) generates scale-free degree distributions following power laws, where high-degree hubs emerge via cumulative advantage, observed in collaboration and citation networks but critiqued for overemphasizing growth over static social constraints.[65]Indigenous Theories

Structural role theory represents one of the primary theoretical contributions endogenous to social network analysis, emphasizing that social roles derive from actors' positions within relational structures rather than personal attributes or external norms. Formulated by O. A. Oeser and Frank Harary in 1962, the theory decomposes roles into three interrelated components: tasks (specific functions), positions (structural locations defined by ties to other positions), and persons (individuals occupying those positions). Positions are equivalent if they exhibit identical patterns of connections, leading to shared role expectations and behaviors; this equivalence is quantified through adjacency matrices and path analyses, revealing how interdependencies generate stable role configurations.[69] The model's predictive power lies in identifying role strains, such as conflicts arising from incompatible task demands across connected positions, which has been applied to organizational settings where network topology explains coordination failures or efficiencies.[70] A companion formulation in 1964 extended the model to dynamic aspects, incorporating feedback loops between persons and positions to account for role adaptation over time.[71] This approach prioritizes causal mechanisms rooted in relational data, positing that structural constraints dictate behavioral outcomes more deterministically than attribute-based explanations. Empirical validations, such as in group participation indices derived from role matrices, confirm that actors in structurally similar positions display correlated actions, supporting the theory's emphasis on endogenous network properties over exogenous factors.[72] Beyond structural role theory, indigenous frameworks in social network analysis often manifest as partial theories centered on endogenous processes like triadic closure, where the presence of two ties increases the likelihood of a third, fostering network density through mechanisms of reciprocity and transitivity. These principles, formalized in algebraic representations of signed graphs, predict stability in positive tie clusters and instability in mixed-sign triads, influencing applications from alliance formation to conflict resolution without reliance on imported psychological constructs. Such theories highlight SNA's focus on relational realism, where observable tie patterns causally underpin social phenomena, though comprehensive general theories remain scarce compared to methodological advancements.[73]Structural Holes and Network Positions