Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

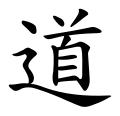

Waidan

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

| Waidan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Seal script for wàidān 外丹 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 外丹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | outside cinnabar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 외단 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 外丹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 外丹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | がいたん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Waidan, translated as 'external alchemy' or 'external elixir', is the early branch of Chinese alchemy that focuses upon compounding elixirs of immortality by heating minerals, metals, and other natural substances in a luted crucible. The later branch of esoteric neidan 'inner alchemy', which borrowed doctrines and vocabulary from exoteric waidan, is based on allegorically producing elixirs within the endocrine or hormonal system of the practitioner's body,[1] through Daoist meditation, diet, and physiological practices. The practice of waidan external alchemy originated in the early Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), grew in popularity until the Tang (618–907), when neidan began and several emperors died from alchemical elixir poisoning, and gradually declined until the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Terminology

[edit]The Chinese compound wàidān combines the common word wài 外 'outside; exterior; external' with dān 丹 'cinnabar; vermillion; elixir; alchemy'. The antonym of wài is nèi 內 meaning 'inside; inner; internal', and the term wàidān 外丹 'external elixir/alchemy' was coined in connection with the complementary term nèidān 'internal elixir/alchemy'.

The sinologist and expert on Chinese alchemy Fabrizio Pregadio lists four generally accepted meanings of dan: "The color cinnabar, scarlet, or light scarlet", "The mineral cinnabar, defined as 'a red stone formed by the combination of quicksilver and sulphur'", "Sincerity (corresponding to danxin 丹心)", and "An essence obtained by the refining of a medicinal substance; a refined medicinal substance, the so-called medicine of the seekers of immortality for avoiding aging and death; a term often used for matters concerning the immortal". Pregadio concludes that the semantic field of the word dan evolves from a root-meaning of "essence", and its connotations include "the reality, principle, or true nature of an entity or its essential part, and by extension, the cognate notions of oneness, authenticity, sincerity, lack of artifice, simplicity, and concentration."[2]

The date for the earliest use of the term waidan is unclear. It occurs in Du Guangting's 901 Daode zhenjing guangshengyi 道德真經廣聖義 (Explications Expanding on the Sages [Commentaries] on the Daodejing), which is quoted in the 978 Taiping guangji. Liu Xiyue's 劉希岳 988 Taixuan langranzi jindao shi 太玄朗然子進道詩 (Master Taixuan Langran's Poems on Advancing in the Dao) has the earliest mention of both the terms neidan and waidan.[3]

Jindan zhi dao 金丹之道 (Way of the Golden Elixir) was a classical name for waidan alchemy, and wàidān shù 外丹術 (with 術 'art; skill; technique; method') is the Modern Standard Chinese term.

History

[edit]Joseph Needham, the eminent historian of science and technology, divided Chinese alchemy into the "golden age" (400–800) from the end of the Jin to late Tang dynasty and the "silver age" (800–1300) from late Tang to the end of the Song dynasty.[4] Furthermore, Fabrizio Pregadio uses "golden age" in specific reference to the Tang period.[5]

The extant Chinese alchemical literature comprises about 100 sources preserved in the Daoist Canon. These texts show that while early waidan was mainly concerned with the performance of ceremonies and other ritual actions addressed to gods and demons, a shift occurred around the 6th or 7th century to the later tradition that used alchemical symbolism to represent the origins and functioning of the cosmos, which played a crucial role in the development of neidan.[6]

Early references

[edit]Little is known about the origins of alchemy in China. The historian and sinologist Nathan Sivin gives an approximate timeline: the Chinese belief in the possibility of physical immortality began around the 8th century BCE, the acceptance that immortality was attainable by taking herbal drugs started in the 4th century BCE, but the uncertain date when the idea that immortality drugs could be made through alchemy rather than found in nature was no later than the 2nd century BCE.[7] Despite a later tradition that Zou Yan (c. 305–240 BCE), founder of the School of Yin Yang, was an early alchemist, his biography does not mention alchemy, and no waidan text is attributed to him.[8]

The sinologist Homer H. Dubs proposed that the earliest historical allusion to Chinese alchemy was in 144 BCE, but other scholars are doubtful. Emperor Jing of Han's 144 BCE anti-coining edict "established a statute (fixing) public execution for (privately) coining of cash or counterfeiting gold" that Dubs believes also made alchemy illegal.[9] However, Jing's imperial decree did not ban making alchemical elixirs but rather, privately coining money; the commentary of Ying Shao (140–206 CE) explains how it abrogated the 175 BCE edict by the previous Emperor Wen that allowed people to cast coins without authorization.[10]

The first historically reliable mention of alchemy in China concerns Li Shaojun, a fangshi "masters of methods", who suggested around 133 BCE that Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87) should prepare for the feng 封 and shan 禪 state rituals to Heaven and Earth by performing an alchemical method of transmuting cinnabar into gold.[6] According to the c. 94 BCE Shiji,

Li Shaojun told the Emperor: "By making offerings to the stove (zao), one can summon the supernatural beings (wu). If one summons them, cinnabar can be transmuted into gold. When gold has been produced and made into vessels for eating and drinking, one can prolong one’s life. If one’s life is prolonged, one will be able to meet the immortals of the Penglai Island in the midst of the sea. When one has seen them and has performed the feng and shan ceremonies, one will never die. The Yellow Emperor did just so. Your subject formerly, when sailing on the sea, encountered Master Anqi (Anqi Sheng), who feeds on jujube-dates as large as melons. Master Anqi is an immortal who roams about Penglai; when it pleases him to appear to humans, he does so, otherwise he remains invisible." Thereupon the Emperor for the first time personally made offerings to the stove. He sent some fangshi to the sea to search for the legendary Penglai and for alchemists who could transmute cinnabar and other substances into gold. [11]

Li Shaojun's immortality elixir in this passage was not meant to be consumed, but used to cast alchemical gold cups and dishes that would supposedly prolong the emperor's life to the point that he could perform the thaumaturgic and ritual prerequisites to ultimately become immortal.[12]

Although Liu An's c. 120 BCE Huainanzi does not explicitly refer to alchemy, it does have a passage on the natural evolution of minerals and metals in the earth, which became a prominent idea in later waidan cosmological texts. They state that elixir compounding reproduces the process through which nature spontaneously transmutes minerals and metals into gold, but alchemy accelerates it by compressing or "manipulating" [13] the centuries of time that the natural process requires, using huohou 火 候 'fire times' to match cycles of different lengths.[14] The Huainanzi context lists wu-xing "Five Phases/Elements" correlations for colors, minerals, and metals.

The qi of balanced earth is received into the yellow heaven, which after five hundred years engenders a yellow jade [possibly realgar or amber]. After five hundred years this engenders a yellow quicksilver, which after five hundred years engenders gold ["yellow metal"]. After one thousand years, gold engenders the yellow dragon. The yellow dragon, going into hiding, engenders the yellow springs. When the dust from the yellow springs rises to become a yellow cloud, the rubbing together of yin and yang makes thunder; their rising and spreading out make lightning. What has ascended then descends as a flow of water that collects in the yellow sea. [15]

For each of the Five Colors (yellow, bluegreen, vermillion, white, and black), the Huainanzi transmutation process involves a corresponding mineral, quicksilver (using the archaic name hòng 澒 for gǒng 汞 'mercury; quicksilver'), and metal (jīn 金). The other four colored metamorphoses are bluegreen malachite-quicksilver-lead, vermillion cinnabar-quicksilver-copper, white arsenolite-quicksilver-silver, and black slate-quicksilver-iron. According to Dubs, this passage omits mentioning alchemy because of its illegality. It accounts for common alchemical ingredients like quicksilver, and comes from the School of Yin-Yang and perhaps even Zou Yan himself.[16] Major says it is considered to be "China's oldest statement of the principles of alchemy".[17]

The c. 60 BCE Yantie lun (Discourses on Salt and Iron) has the earliest reference to the ingestion of alchemical elixirs in a context criticizing Qin Shi Huang's patronage of anyone who claimed to know immortality techniques.[18] "At that time, the masters (shi) of Yan and Qi set aside their hoes and digging sticks and competed to make themselves heard on the subject of immortals and magicians. Consequently the fangshi who headed for [the Qin capital] Xianyang numbered in the thousands. They asserted that the immortals had eaten of gold and drunk of pearl; after this had been done, their lives would last as long as Heaven and Earth."[19]

The erudite Han official Liu Xiang (77-6 BCE) attempted and failed to compound alchemical gold. The Hanshu says that in 61 BCE, Emperor Xuan became interested in immortality and employed numerous fangshi specialists to recreate the sacrifices and techniques used by his great-grandfather, Emperor Wu. In 60 BCE, Liu Xiang presented the emperor with a rare alchemical book entitled Hongbao yuanbi shu 鴻寳苑祕術 (Arts from the Garden of Secrets of the Great Treasure)–which had supposedly belonged to the Huainanzi compiler Liu An–that described "divine immortals and the art of inducing spiritual beings to make gold" and Zou Yan's chongdao 重道 "recipe for prolonging life by a repeated method [of transmutation]".[20] The chongdao context is also translated as "a method of repeated (transmutation)",[21] or reading zhongdao as "important methods by Zou Yan for prolonging life".[22] Emperor Xuan commissioned Liu Xiang to produce alchemical gold, but he was ultimately unsuccessful despite having access to the best available alchemical texts in the imperial library, the expertise of numerous fangshi and metallurgist assistants, and unlimited imperial resources. In 56 BCE, the emperor ordered Liu to be executed yet later reduced the sentence. Dubs concludes that a "more complete and adequate test of alchemy could not have been made".[23]

First texts

[edit]The oldest extant Chinese alchemistic texts, comprising the Taiqing corpus, Cantong qi, and Baopuzi, date from around the 2nd to 4th centuries.

The Daoist Taiqing 太清 (Great Clarity) tradition produced the earliest known textual corpus related to waidan. Its main scriptures were the Taiqing jing 太清經 (Scripture of Great Clarity), the Jiudan jing 九丹經 (Scripture of the Nine Elixirs), and the Jinye jing 金液經 (Scripture of the Golden Fluid), which early sources say were revealed to the Han fangshi Zuo Ci at the end of the 2nd century. Both the Baopuzi (below) and the received versions of these scriptures in the Daoist Canon show that the Taiqing tradition developed in Jiangnan (lit. 'south of the Yangtze river'), in close relation to local exorcistic and ritual practices.[24]

The Zhouyi Cantong Qi (Token for the Agreement of the Three According to the Book of Changes) or Cantong qi, is traditionally considered the earliest Chinese book on alchemy. Its original version is attributed to Wei Boyang in the mid-2nd century, but the received text was augmented during the Six Dynasties (220-589) period. Unlike the earlier Taiqing tradition, which focuses on ritual, the Cantong qi is based on correlative cosmology and uses philosophical, astronomical, and alchemical emblems to describe the relation of the Dao to the universe. For instance, the two main emblems are zhengong 真汞 (Real Mercury) and zhenqian 真鉛 (Real Lead), respectively corresponding to Original Yin and Original Yang.[25] This choice of mercury and lead as the prime ingredients for elixir alchemy limited later potential experiments and resulted in numerous cases of poisoning. It is quite possible that "many of the most brilliant and creative alchemists fell victim to their own experiments by taking dangerous elixirs".[26] The new Cantong qi view of the alchemical process not only influenced the later development of waidan, but also paved the way for the rise of neidan. From the Tang period onward, the Cantong qi became main scripture of both waidan and neidan alchemies.

The Daoist scholar Ge Hong's c. 318-330 Baopuzi devotes two of its twenty chapters to waidan alchemy. Chapter 4, Jindan 金丹 "Gold and Cinnabar", focuses on the Taiqing corpus, whose methods are mostly based on minerals, and Chapter 16, Huangbai 黃白 "The Yellow and the White", contains formulas centered on metals.[27] Ge Hong says that the ritual context of the two sets of practices was similar, but the scriptures were transmitted by different lineages.[28] In addition, the Baopuzi quotes, summarizes, or mentions many other waidan methods, often from unknown sources.[29]

Chapter 4, "Gold and Cinnabar", provides a variety of formulas for elixirs of immortality. Most of them involve shijie 尸解 "liberation from the corpse", which generates "a new physical but immortal self (embodying the old personality) that leaves the adept's corpse like a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis", and is verifiable when the corpse, light in weight as an empty cocoon, did not decay after death.[30] Many Baopuzi elixirs are based on arsenic and mercury compounds, which have "excellent embalming properties".[31] Some less effective elixirs only provide longevity, cure disease, or allow the adept to perform miracles. The Baoppuzi lists a total of 56 chemical preparations and elixirs, 8 of which were poisonous, with hallucinations from mercury poisoning the most commonly reported symptom.[32]

Baopuzi Chapter 16, "The Yellow and the White", records several methods for preparing artificial alchemical gold and silver, which when ingested will provide immortality.[33] It also includes a few elixir formulas with effects such as providing invulnerability or reversing the course of a stream.[34] Ge Hong emphasizes that waidan alchemy grants access to higher spiritual realms and is therefore superior to other practices such as healing, exorcism, and meditation.[35]

Golden age

[edit]What Needham calls the "golden age of Chinese alchemy" (c. 400-800) was from the end of the Jin to the late Tang dynasty.

The Daoist scholar and alchemist Tao Hongjing (456–536) was a founder of the Shangqing (Highest Clarity) and the compiler-editor of the basic "Shangqing revelations" purportedly dictated to Yang Xi by Daoist deities between 364 and 370.[6] Many of these revealed texts described immortality elixirs, and Tao incorporated the core Taiqing (Great Clarity) alchemical texts into the Shangqing corpus, marking the first encounter between waidan and an established Daoist movement. Although the Shangqing texts used the waidan process mainly as a support for meditation and visualization practices, the language, techniques, and rituals in these works are mostly identical with those of the Taiqing corpus.[35] Tao was commissioned by Emperor Wu of Liang to experiment with waidan alchemy and produce elixirs, but only achieved limited success.

The decline of the original Taiqing tradition resulted in a tendency to focus the alchemical process on two major methods: refining cinnabar into mercury and compounding lead with mercury. Advocates of the cinnabar-mercury waidan methods, such as the 8th-century alchemist Chen Shaowei 陳少微, described producing quicksilver in cosmological terms, without any reference to the Cantong qi system. During the Tang dynasty, the lead-mercury tradition based on the Cantong qi acquired importance, and waidan alchemy was transformed from an instrument for communicating with supernatural beings to a support for intellectualizing philosophical principles.[36] Several works related to the Cantong qi rejected cinnabar-mercury methods with the rationale that yang cinnabar and yin mercury alone cannot produce the true elixir. Historically, the lead-mercury theory became the predominant method.[25]

The Tang period is also known for intensified imperial patronage of waidan, even though elixir poisoning caused the death of Emperors Wuzong (r. 840-846), Xuanzong (r. 846-859), and likely also Xianzong (r. 805-820) and Muzong (r. 820-824).[25] While elixir poisoning is sometimes designated as a reason for the decline of waidan after the Tang, the shift to neidan was the result of a much longer and more complex process. Waidan and early neidan developed together throughout the Tang and were closely interrelated.[37]

Silver age

[edit]Needham's "silver age of Chinese alchemy" (c. 800-1300) was from the late Tang to the end of the Song dynasty. During the Tang, waidan literature gradually changed from emphasizing ritual practices to cosmological principles. Early Taiqing tradition texts stress the performance of alchemical rites and ceremonies when compounding, and described elixirs as tools for either summoning benevolent gods or expelling malicious spirits. Most post-Tang waidan texts related to Cantong qi alchemy stress the cosmological significance of elixir compounding and employ numerous abstract notions.[38] After the late Tang period, waidan gradually declined and the soteriological immortality significance of alchemy was transferred to neidan.[25]

Imperial interest in alchemy continued during the Song dynasty (960-1279). Emperor Zhenzong (r. 997-1022) established a laboratory in the Imperial Academy, where the Daoist alchemist Wang Jie 王捷 "produced and presented to the throne artificial gold and silver amounting to many tens of thousands (of cash), brilliant and glittering beyond all ordinary treasures".[39]

Most waidan sources dating from the Song and later periods are either anthologies of earlier writings or deal with metallurgical techniques.[25] Waidan alchemy subsequently declined in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties.[40]

Laboratory and instruments

[edit]

Chinese descriptions of alchemical laboratory equipment vary among texts and traditions, but share some common terminology. The following outline concerns alchemical hardware rather than liturgical or magical artifacts such as the sword, sun and moon mirrors, and peach-wood talismans.

The alchemy laboratory was called the Chamber of Elixirs (danshi 丹室, danwu 丹屋, or danfang 丹房). Sources differ about how to construct one. One text says the Chamber is ideally built near a mountain stream on in a secluded place, and has two doors, facing east and south; another says it should never be built over an old well or tomb, and has doors facing in all directions except north.[41]

A layered "laboratory bench" called tan 壇 "altar; platform" was placed either in the center or along a wall of the Chamber.[42] It was commonly depicted as a three-tiered clay stove platform, with eight ventilating openings on each tier—8 numerologically signifying bafang 八方 (lit. 'eight directions') "eight points of the compass; all directions".[41] The alchemist's heating apparatus, interchangeably called lu 爐 'stove; furnace' or zao 竈 '(kitchen) stove', was placed on the highest tier of the tan platform. Owing to inconsistent textual terminology, it translates as 'stove' or 'furnace' in some sources and as 'oven' or 'combustion chamber' in others.[43] Depending upon the alchemical formula, rice hulls, charcoal, or horse manure served as fuel.

A waidan alchemical fu 釜 'crucible; cauldron' was placed over the zao stove or sometimes inside it. The shuangfu 雙釜 'double crucible' was commonly made of red clay and had two halves joined to each other by their mouths.[44] Another type of crucible had an iron lower half and clay upper one.[45] After placing the ingredients in a crucible, the alchemist would hermetically seal it by applying several layers of a lute clay preparation inside and outside. The classic alchemical luting mixture was liuyini 六一泥 Six-and-One Mud with seven ingredients, typically alum, Turkestan rock salt (rongyan 戎鹽), lake salt, arsenolite, oyster shells, red clay, and talc.[44]

Two common types of open alchemical reaction vessels were called ding 鼎 'tripod; container; cauldron' and gui 匱 'box; casing; container; aludel'.[46] Ding 鼎 originally named a "tripod cauldron" Chinese ritual bronze, but alchemists used the term (and dingqi 鼎器) in reference to numerous metal or clay instruments with different shapes and functions.[44] Ding generally named both pots and various other reaction vessels to which fire was applied externally—as distinguished from lu that contained fire within.[46] Gui 匱 (an old character for gui 櫃 'cupboard; cabinet') was an alchemical name for a reaction vessel casing that was placed within a reaction chamber. Broadly speaking, gui had lids while ding were open at the top.[47]

Besides the more open bowl-like or crucible forms of reaction vessels, whether lidded or not, many kinds of sealed containers were employed. Two common ones were the shenshi 神室 (lit. 'divine chamber') corresponding to the aludel subliming pot used in Arabic alchemy, and the yaofu 藥釜 'pyx; bomb' vessel composed of two roughly hemispherical crucible-like bowls with flanges placed mouth to mouth.[48]

In addition to these basic tools, the alchemical apparatus also includes both common utensils (like mortars and pestles) and various specialized laboratory instruments for steaming, condensation, sublimation, distillation, and extraction.[49]

References

[edit]- ^ Beans, Donald (2009). Integrative Endocrinology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781135252083.

- ^ Pregadio 2006, pp. 68–70

- ^ Baldrian-Hussein 1989, pp. 174, 178, 180

- ^ Needham, Ho & Lu 1976, pp. 117–166, 167–207

- ^ Pregadio 2014, p. 25

- ^ a b c Pregadio 2008, p. 1002

- ^ Sivin 1968, p. 25

- ^ Pregadio 2006, p. 5

- ^ Dubs 1947, p. 63

- ^ Pregadio 2000, p. 166

- ^ Pregadio 2006, p. 10

- ^ Sivin 1968, p. 25

- ^ Sivin 1977

- ^ Pregadio 2000, p. 184

- ^ Major et al. 2010, p. 170

- ^ Dubs 1947, pp. 70, 73

- ^ Major et al. 2010, p. 152

- ^ Sivin 1968, p. 26

- ^ Pregadio 2006, p. 31

- ^ Dubs 1947, p. 75

- ^ Needham, Ho & Lu 1976, p. 14

- ^ Pregadio 2006, p. 27

- ^ Dubs 1947, p. 77

- ^ Pregadio 2008, pp. 1002–1003

- ^ a b c d e Pregadio 2008, p. 1003

- ^ Needham, Ho & Lu 1976, p. 74

- ^ Pregadio 2000, p. 167

- ^ Ware 1966, p. 261

- ^ Needham, Ho & Lu 1976, pp. 81–113

- ^ Ware 1966, pp. 68–96

- ^ Sivin 1968, p. 41

- ^ Needham, Ho & Lu 1976, pp. 89–96

- ^ Ware 1966, pp. 261–278

- ^ Sivin 1968, p. 42

- ^ a b Pregadio 2000, p. 168

- ^ Pregadio 2000, p. 170

- ^ Needham & Ho 1983, pp. 218–229

- ^ Pregadio 2000, p. 179

- ^ Needham, Ho & Lu 1976, p. 186

- ^ Needham & Lu 1974, p. 208-219

- ^ a b Pregadio 2000, p. 188

- ^ Sivin 1980, p. 10

- ^ Sivin 1980, p. 11

- ^ a b c Pregadio 2000, p. 189

- ^ Sivin 1968, pp. 166–168

- ^ a b Sivin 1980, p. 16

- ^ Sivin 1980, p. 18

- ^ Sivin 1980, p. 22

- ^ Sivin 1980, pp. 26–103

- Baldrian-Hussein, Farzeen (1989). "Inner Alchemy: Notes on the Origin and Use of the Term Neidan". Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie. 5: 163–190. doi:10.3406/asie.1989.947.

- Baldrian-Hussein, Farzeen (2008). "Neidan 內丹 internal elixir; internal alchemy". In Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Routledge. pp. 762–66. ISBN 9780700712007.

- Dubs, Homer H. (1947). "The Beginnings of Alchemy". Isis. 38 (1): 62–86. doi:10.1086/348038.

- Eliade, Mircea (1978). The Forge and the Crucible: The Origins and Structure of Alchemy. University Of Chicago Press. pp. 109–26. ISBN 9780226203904.

- Ho, Peng Yoke (1979). On the Dating of Taoist Alchemical Texts. Griffith University. ISBN 9780868570754.

- Johnson, Obed Simon (1928). A Study of Chinese Alchemy. Martino Pub.

- Major, John S.; Queen, Sarah A.; Meyer, Andrew Seth; Roth, Harold D. (2010). The Huainanzi. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52085-0.

- Needham, Joseph; Lu, Gwei-djen, eds. (1974). Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 2, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521085717.

- Needham, Joseph; Ho, Ping-Yu; Lu, Gwei-djen, eds. (1976). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 3: Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Historical Survey, from Cinnabar Elixirs to Synthetic Insulin. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521210287.

- Needham, Joseph; Ho, Ping-yu; Lu, Gwei-djen; Sivin, Nathan, eds. (1980). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories, and Gifts. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521085731.

- Needham, Joseph; Ho, Ping-yu, eds. (1983). Science and civilisation in China. Vol. 5, Chemistry and chemical technology. Part 5, Spagyrical discovery and invention: physiological alchemy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521085748.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (1996). "Chinese Alchemy. An Annotated Bibliography of Works in Western Languages". Monumenta Serica. 44: 439–473. JSTOR 40727097.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2000). "Elixirs and Alchemy". In Kohn, Livia (ed.). Daoism Handbook. E. J. Brill. pp. 165–195. ISBN 9789004112087.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2006). Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804751773.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2008). "Waidan "external elixir; external alchemy" 外丹". In Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Routledge. pp. 1002–1004. ISBN 9780700712007.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2014). The Way of the Golden Elixir: A Historical Overview of Taoist Alchemy. Golden Elixir.

- Seidel, Anna (1989). "Chronicle of Taoist Studies in the West 1950-1990". Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie. 5 (1): 223–347. doi:10.3406/asie.1989.950.

- Sivin, Nathan (1968). Chinese Alchemy: Preliminary Studies. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780196264417.

- Sivin, Nathan (1976). "Chinese Alchemy and the Manipulation of Time". Isis. 67 (4): 513–526. doi:10.1086/351666.

- Sivin, Nathan (1977). Science and technology in East Asia. Science History Publications. ISBN 9780882021621.

- Sivin, Nathan (1980). "The Theoretical Background of Laboratory Alchemy". In Needham, Joseph; Ho, Ping-yu; Lu, Gwei-djen; Sivin, Nathan (eds.). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus and Theory. Cambridge University Press. pp. 210–305. ISBN 9780521085731.

- Waley, Arthur (1930). "Notes on Chinese Alchemy ("Supplementary to Johnson's" A Study of Chinese Alchemy)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies. 6 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00090911.

- Ware, James R. (1966). Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The Nei Pien of Ko Hung. Dover. OCLC 23118484.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- "Taoist Alchemy", Fabrizio Pregadio