Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

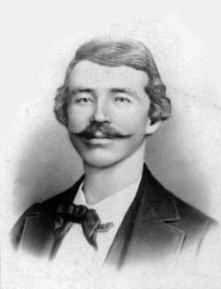

William Quantrill

View on Wikipedia

William Clarke Quantrill (July 31, 1837 – June 6, 1865) was a Confederate guerrilla leader during the American Civil War.

Key Information

Quantrill experienced a turbulent childhood, became a schoolteacher, and joined a group of bandits who roamed the Missouri and Kansas countryside to apprehend escaped slaves. The group became irregular pro-Confederate soldiers called Quantrill's Raiders, a partisan ranger outfit best known for its often brutal guerrilla tactics in defense of the Confederacy, and including the young Jesse James and his older brother Frank James.

Quantrill was influential to many bandits, outlaws, and hired guns of the American frontier as it was being settled. On August 21, 1863, Quantrill's Raiders committed the Lawrence Massacre. In May 1865, Quantrill was mortally wounded in combat by U.S. troops in Central Kentucky in one of the last engagements of the American Civil War. He died of his wounds in June 1865.

Early life

[edit]William Quantrill was born at Canal Dover, Ohio, on July 31, 1837. His father was Thomas Henry Quantrill, formerly of Hagerstown, Maryland, and his mother, Caroline Cornelia Clark, was a native of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. William was the oldest of twelve children, four of whom died in infancy.[1] Quantrill taught school in Ohio when he was sixteen.[2] In 1854, his abusive father died of tuberculosis, leaving the family with a huge financial debt. Quantrill's mother turned the home into a boarding house to survive. During this time, Quantrill helped support the family by working as a schoolteacher, but he left home a year later for Mendota, Illinois.[3]: 54 There, Quantrill worked in the lumberyards, unloading timber from rail cars.

Authorities briefly arrested him for murder, but Quantrill claimed he had acted in self-defense. Quantrill was set free since there were no eyewitnesses, and the victim was a stranger who knew no one in town. Nevertheless, the police strongly urged him to leave Mendota. Quantrill continued teaching, moving to Fort Wayne, Indiana, in February 1856. Quantrill journeyed back home to Canal Dover late that year.[3]: 55

Quantrill spent the winter in his family's diminutive shack in the impoverished town and soon grew restless. Many Ohioans migrated to the Kansas Territory for cheap land and opportunity. This included Henry Torrey and Harmon Beeson, two local men hoping to build a large farm for their families out west. Although they mistrusted the 19-year-old Quantrill, his mother's pleadings persuaded them to let Quantrill accompany them to turn his life around.[citation needed] The party of three departed in late February 1857. Torrey and Beeson agreed to pay for Quantrill's land in exchange for Quantrill working for them. They settled along the Marais des Cygnes River, but a dispute arose over the claim, and Quantrill sued Torrey and Beeson. The court awarded Quantrill $63, but he was only paid half of this amount. Quantrill later attempted to rectify this by stealing oxen, firearms, and blankets from Beeson, but he was caught and returned the oxen and weapons; the blankets were not found until later, by which time they had rotted. Afterwards, Beeson became hostile towards Quantrill, but Quantrill remained friends with Torrey.[4]

Soon, Quantrill accompanied a large group of hometown friends in their quest to settle near Tuscarora Lake. However, neighbors soon began to notice Quantrill stealing goods out of other people's cabins and banished him from the community in January 1858.[citation needed] Soon thereafter, Quantrill signed on as a teamster with the US Army expedition heading to Salt Lake City, Utah in early 1858. Quantrill's journey out west is little known except that he excelled at poker. Quantrill racked up piles of winnings by playing the game against his comrades at Fort Bridger but lost it all on one hand, leaving him broke. Quantrill then joined a group of Missouri ruffians and became a drifter. The group helped protect pro-slavery Missouri farmers from the Jayhawkers for pay and slept wherever they could find lodging. Quantrill traveled back to Utah and then to Colorado but returned in less than a year to Lawrence, Kansas, in 1859[5] where he taught at a schoolhouse until it closed in 1860. Quantrill then partnered with brigands and turned to cattle rustling and anything else to earn him money. Quantrill also learned the profitability of capturing runaway slaves and devised plans to use free black men as bait for runaway slaves, whom he subsequently captured and returned to their enslavers in exchange for reward money.[citation needed]

Before 1860, Quantrill appeared to oppose slavery. He wrote to his good friend W.W. Scott in January 1858 that the Lecompton Constitution was a "swindle" and that James Henry Lane, a Northern sympathizer, was "as good a man as we have here". He also called the Democrats "the worst men we have for they are all rascals, for no one can be a democrat here without being one".[6] However, in February 1860, Quantrill wrote a letter to his mother that expressed his views on the anti-slavery supporters. Quantrill told her that slavery was right and that he detested Jim Lane. He said that the hanging of John Brown had been too good for him and that "the devil has got unlimited sway over this territory, and will hold it until we have a better set of man and society generally."[7]

Guerrilla leader

[edit]In 1861, Quantrill went to Texas with Marcus Gill. They met Joel B. Mayes and joined the Cherokee Nations. Mayes, of mixed Scots-Irish and Cherokee descent, was a Confederate sympathizer and a war chief of the Cherokee Nations in Texas. Mayes had moved from Georgia to the old Indian Territory in 1838. Mayes enlisted and served as a private in Company A of the 1st Cherokee Regiment in the Confederate army. Mayes taught Quantrill guerrilla warfare tactics, ambush fighting tactics used by Native Americans, camouflage, and sneak attack tactics. Quantrill, in the company of Mayes and the Cherokee Nations, joined with General Sterling Price and fought at the Battle of Wilson's Creek and First Battle of Lexington in August and September 1861.[8]

In late September Quantrill went to Blue Springs, Missouri, to form his own partisan unit made of loyal men who had great belief in him and the Confederate cause, and they came to be known as "Quantrill's Raiders". By Christmas 1861, ten men followed Quantrill full-time in his pro-Confederate guerrilla organization:[3][page needed] William Haller, George Todd, Joseph Gilcrist, Perry Hoy, John Little, James Little, Joseph Baughan, William H. Gregg, James A. Hendricks, and John W. Koger. Later, in 1862, John Jarrett, John Brown (not to be confused with the abolitionist John Brown), Cole Younger, William T. "Bloody Bill" Anderson, and the James brothers would join Quantrill's army.[9] On March 7, 1862, Quantrill and his men attacked a small US Army outpost in Aubry, Kansas, and ransacked the town.[10]

On March 11, 1862, Quantrill joined Confederate forces under Colonel John T. Hughes and took part in an attack on Independence, Missouri. After what became known as the First Battle of Independence, the Confederate government decided to secure the loyalty of Quantrill by issuing him a "formal army commission" to the rank of captain.[11]

In the early hours of September 7, 1862, William Quantrill and a force of 140 men seized control of Olathe, Kansas, capturing 125 US Army soldiers.[12] On October 5, 1862, Quantrill attacked and destroyed Shawneetown, Kansas; William T. Anderson soon revisited and torched the rebuilding settlement.[13] On November 5, 1862, Quantrill joined Colonel Warner Lewis to stage an attack on Lamar, Missouri, where a company of the 8th Regiment Missouri Volunteer Cavalry protected a US Army outpost. Warned about the attack, the US soldiers repelled the raiders, who torched part of the town before they retreated.[14]

Lawrence Massacre

[edit]The most significant event in Quantrill's guerrilla career occurred on August 21, 1863. Lawrence had been seen for years as the stronghold of the antislavery forces in Kansas and as a base of operation for incursions into Missouri by Jayhawkers and pro-Union forces. It was also the home of James Henry Lane, a US senator known for his staunch opposition to slavery and a leader of the Jayhawkers.

During the weeks immediately preceding the raid, US Army General Thomas Ewing, Jr., ordered the detention of any civilians giving aid to Quantrill's Raiders. Several female relatives of the guerrillas were imprisoned in a makeshift jail in Kansas City, Missouri. On August 14, the building collapsed, killing four young women and seriously injuring others. Among the dead was Josephine Anderson, the sister of one of Quantrill's key guerrilla allies, Bill Anderson. Another of Anderson's sisters, Mary, was permanently crippled in the collapse. Quantrill's men believed the collapse was deliberate, which infuriated them.

Some historians have suggested that Quantrill planned to raid Lawrence before the building's collapse, in retaliation for earlier Jayhawker attacks[15][page needed] as well as the burning of Osceola, Missouri.

Early in the morning of August 21, Quantrill descended from Mount Oread and attacked Lawrence with a combined force of 450 guerrilla fighters. Lane, a prime target of the raid, managed to escape through a cornfield in his nightshirt, but the guerrillas, on Quantrill's orders, killed around 150 men and boys who could carry a rifle.[16] When Quantrill's men rode out at 9 a.m., most of Lawrence's buildings were burning, including all but two businesses.

On August 25, in retaliation for the raid, General Ewing authorized General Order No. 11 (not to be confused with General Ulysses S. Grant's order of the same name). The edict ordered the depopulation of three and a half Missouri counties along the Kansas border except for a few designated towns, which forced tens of thousands of civilians to abandon their homes. Union troops marched through behind them and burned buildings, torched planted fields, and shot down livestock to deprive the guerrillas of food, fodder, and support. The area was so thoroughly devastated that it was known as the "Burnt District".[17]

In early October, Quantrill and his men rode south to Texas, to pass the winter. On the way, on October 6, Quantrill attacked Fort Blair in Baxter Springs, Kansas, which resulted in the so-called Battle of Baxter Springs. After being repelled, Quantrill surprised and destroyed a US Army relief column under General James G. Blunt, who escaped, but Quantrill killed almost 100 US Army soldiers.[18]

In Texas, on May 18, 1864, Quantrill's sympathizers lynched Collin County Sheriff Captain James L. Read for shooting the Calhoun Brothers from Quantrill's force who had killed a farmer in Millwood, Texas.[19]

Final year

[edit]

While in Texas, Quantrill and his 400 men quarreled. His once-large band broke up into several smaller guerrilla companies. One was led by his lieutenant, "Bloody Bill" Anderson, and Quantrill joined it briefly in the fall of 1864 during a fight north of the Missouri River.

In early 1865, now leading only a few dozen bushwackers, Quantrill staged a series of raids in western Kentucky. Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses Grant on April 9, and General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered most of the rest of the Confederate Army to General Sherman on April 26. On May 10, the US Army caught up to Quantrill and his band in an ambush in Wakefield, Kentucky. While attempting to flee on a skittish horse, Quantrill was shot in the back and paralyzed from the chest down. The unit that successfully ambushed Quantrill and his followers was led by Edwin W. Terrell, a guerrilla hunter charged with finding and eliminating high-profile targets by General John M. Palmer, the commander of the District of Kentucky. US officials, Palmer and Governor Thomas E. Bramlette, did not wish to see Quantrill staging a repeat of his performance in Missouri in 1862–1863.[20] Quantrill was brought by wagon to Louisville, Kentucky, and taken to the military prison hospital on the north side of Broadway at 10th Street. He died from his wounds on June 6, 1865, at the age of 27.[21]

Burial

[edit]Quantrill was buried in an unmarked grave in what became known as St. John's Cemetery in Louisville. A boyhood friend of Quantrill, the newspaper reporter William W. Scott, claimed to have dug up the Louisville grave in 1887 and brought Quantrill's remains back to Dover at the request of Quantrill's mother. The remains were supposedly buried in Dover in 1889, but Scott attempted to sell what he said were Quantrill's bones, so it is unknown if the remains he returned to Dover or buried in Dover were genuine. In the early 1990s, the Missouri division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans convinced the Kansas State Historical Society to negotiate with authorities in Dover, which led to three arm bones, two leg bones, and some hair, all of which were allegedly Quantrill's, being re-buried in 1992 at the Old Confederate Veteran's Home Cemetery in Higginsville, Missouri. As a result, there are grave markers for Quantrill in Louisville, Dover, and Higginsville.[22]

Claims of survival

[edit]In August 1907, news articles appeared in Canada and the US that claimed that J.E. Duffy, a member of a Michigan cavalry troop that had dealt with Quantrill's raiders during the war, met Quantrill at Quatsino Sound on northern Vancouver Island, while he was investigating timber rights in the area. Duffy claimed to recognize the man, living under the name of John Sharp, as Quantrill. Duffy said that Sharp admitted he was Quantrill and discussed raids in Kansas and elsewhere in detail. Sharp claimed that he had survived the ambush in Kentucky but received a bayonet and bullet wound, making his way to South America, where he lived some years in Chile. He returned to the US and worked as a cattleman in Fort Worth, Texas. He then moved to Oregon, acting as a cowpuncher and drover, before he reached British Columbia in the 1890s, where he worked in logging, trapping, and finally as a mine caretaker at Coal Harbour at Quatsino. Within weeks after the news stories were published, two men came to British Columbia, traveling to Quatsino from Victoria, leaving Quatsino on a return voyage of a coastal steamer the next day. On that day, Sharp was found severely beaten and died several hours later without giving information about his attackers. The police failed to solve the murder.[23]

Another legend that has circulated claims that Quantrill may have escaped custody and fled to Arkansas, where he lived under the name of L.J. Crocker until he died in 1917.[24]

The family of Major Cornelius Boyle believed that Quantrill had actually served as a bodyguard for the Provost Marshal General when he visited Mexico after the war, while Jubal Early was also in the country as they sought out an alternate resolution.[25]

Personal life

[edit]During the war, Quantrill met the 13-year-old Sarah Katherine King at her parents' farm in Blue Springs, Missouri. They never married, although she often visited and lived in camp with Quantrill and his men. At the time of his death, she was 17.[citation needed]

Legacy

[edit]

Quantrill's actions were barbaric. Historians view him as an opportunistic, bloodthirsty outlaw. James M. McPherson, one of the most prominent experts on the American Civil War, calls Quantrill and Anderson "pathological killers" who "murdered and burned out Missouri Unionists".[26] The historian Matthew Christopher Hulbert argues that Quantrill "ruled the bushwhacker pantheon" established by the ex-Confederate officer and propagandist John Newman Edwards in the 1870s to provide Missouri with its own "irregular Lost Cause".[27] Some of Quantrill's celebrity later rubbed off on other ex-Raiders, such as John Jarrett, George and Oliver Shepherd, Jesse and Frank James, and Cole Younger, who went on after the war to apply Quantrill's hit-and-run tactics to bank and train robbery.[28]

In popular culture

[edit]Film

[edit]- Dark Command (1940), in which John Wayne opposes former schoolteacher turned guerrilla fighter "William Cantrell" in the early days of the Civil War. William Cantrell is a thinly veiled portrayal of William Quantrill by Walter Pidgeon.

- Renegade Girl (1946) deals with the tension between Unionists and Confederates in Missouri. Ray Corrigan plays Quantrill.

- Kansas Raiders (1950), Brian Donlevy (at age 49) portrayed Quantrill, in which Jesse James (played by Audie Murphy) falls under the influence of the guerilla leader.

- In Best of the Badmen (1951), Robert Ryan plays a Union officer who goes to Missouri after the Civil War to persuade the remnants of Quantrill's band to swear allegiance to the Union in return for a pardon. They are betrayed, and he becomes their leader in a fight against corrupt law officers.

- In Red Mountain (1951), Alan Ladd plays a Confederate officer who joins and later becomes disillusioned with Quantrill, played by John Ireland.

- Stories of the Century (1954) Ruthless raid on Lawrence, Kansas. "Charles" Quantrill is played by Bruce Bennett.

- Quantrill's Raiders (1958) focuses on the raid on Lawrence. Leo Gordon plays Quantrill.

- Young Jesse James (1960) also depicts Quantrill's influence on Jesse James.

- In The Legend of the Golden Gun (1979), two men attempt to track down and kill Quantrill.

- Lawrence: Free State Fortress (1998) depicts the attack on Lawrence.

- In Ride with the Devil (1999), protagonists ride with "Black John Ambrose", who is a loose portrayal of "Bloody Bill" Anderson and later join with Quantrill for the raid on Kansas. Quantrill, Anderson, and most Raiders are portrayed as bloodthirsty and murderous.

Literature

[edit]- Quantrill is a major character in Wildwood Boys (2000), James Carlos Blake's biographical novel of Bloody Bill Anderson.

- In the novel The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales (republished as Gone to Texas in later editions), by Asa (aka Forrest) Carter, Josey Wales is a former member of a Confederate raiding party led by "Bloody Bill" Anderson. The book is the basis of the Clint Eastwood film The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976).

- In Bradley Denton's alternate history tale "The Territory" (1992), Samuel Clemens joins Quantrill's Raiders and is with them when they attack Lawrence, Kansas. It was nominated for a Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy Award for best novella.

- Frank Gruber's article "Quantrell's Flag" (1940), for Adventure Magazine (March through May 1940), was published as a book titled Quantrell's Raiders (Ace Original, 954366 bound with Rebel Road).

- In Charles Portis's novel True Grit, and the 1969 and 2010 film versions thereof, Rooster Cogburn boasts of being a former member of Quantrill's Raiders. Laboeuf excoriates him for being part of the "border gang" that murdered men and children alike during the raid on Lawrence.

- The novel Woe To Live On (1987) by Daniel Woodrell was filmed as Ride With The Devil (1999) by Ang Lee. The film features a harrowing recreation of the Lawrence Massacre with authenticity. Quantrill, played by John Ales, makes brief appearances.

- In the novelization of the 1999 film Wild Wild West by Bruce Bethke, former Confederate General "Bloodbath" McGrath (played by Ted Levine) reflects on the fates of his several friends from the war, including Quantrill, Henry Wirz, and John Singleton Mosby.

- In the novel Lincoln's Sword (2010) by Debra Doyle and James D. Macdonald, the raid on Lawrence, Kansas, is told from the point of view of Cole Younger.

- In the story Hewn in Pieces for the Lord by John J. Miller – published in Drakas!, an anthology of stories set in S. M. Stirling's alternate history series The Domination – Quantrill managed to escape after the fall of the Confederacy, get to the slave-holding Draka society in Africa, and join its ruthless Security Directorate, where he tangles with the rebellious Mahdi in Sudan.

- In the novel Shadow of the Outlaw: Quantrill's Initiation (2021) by Mason Stone – Historical fiction summarizing Quantrill's adult life.

Other

[edit]- He is depicted in Robert Schenkkan's series of one-act plays, The Kentucky Cycle.

- Quantrill's Lawrence Massacre of 1863 is depicted in Steven Spielberg's mini-series Into the West (2005)

References

[edit]- ^ Edward E. Leslie, The Devil Knows How to Ride, Random House, 1996. pp. 406–406, 410

- ^ Blackmar, Frank, ed. (1912). "Quantrill, William". Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc. Standard Publishing Company. p. 524. Archived from the original on June 25, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c Brownlee, Richard (1958). Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy. Library of Congress. Retrieved December 25, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Edward E. Leslie, The Devil Knows How to Ride, Random House, 1996. pp. 49–51

- ^ Edward E. Leslie, The Devil Knows How to Ride, Random House, 1996

- ^ William Connelley, Quantrill and the Border Wars, Pageant Book Co, 1956, pp. 72–74

- ^ William Connelley, Quantrill and the Border Wars, Pageant Book Co, 1956, pp. 94–96. "My Dear Mother", February 8, 1860

- ^ Oklahoma Historical Society, John Bartlett Meserve, Chronicles of Oklahoma Archived February 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 15, no. 1, March 1937, pp. 57–59. Accessed on August 30, 2009.

- ^ John McCorkle, Accessed on 09-08-2009 Three Years With Quantrill Archived April 19, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, written by O.S. Barton, Armstrong Herald Print, 1914. pp. 25–26. Accessed through the Library of Congress online catalog

- ^ Quantrill's Raid on Aubry Archived May 13, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–1865

- ^ Charles D. Collins, Jr. Battlefield Atlas of Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 Archived November 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Fort Leavenworth, Kan.: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2016, p. 21. ISBN 9781940804279

- ^ Quantrill's Raid on Olathe Archived May 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–1865

- ^ In Kansas, Confederate guerrillas attack and burn Shawneetown for the second time Archived October 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The House Divided Project at Dickinson College

- ^ Andra Bryan Stefanoni. Civil War raid on Lamar to be re-enacted for 150th anniversary Archived August 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The Joplin Globe, October 2, 2012

- ^ Paul Wellman, A Dynasty of Western Outlaws, 1961

- ^ Pringle, Heather (April 2010). "Digging the Scorched Earth". Archaeology. 63 (2): 21.

- ^ General Order No. 11 Archived February 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, by Jeremy Neely, Missouri State University, Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–1865

- ^ Quantrill Attacks Fort Blair Archived October 11, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–1865

- ^ A hard history lesson: 'A Civil War Tragedy' details 1864 lynching of Collin County judge, sheriff and sheriff's brother-in-law, McKinney Courier-Gazette, August 30, 2008 Archived

- ^ Matthew Christopher Hulbert, "The Rise and Fall of Edwin Terrell, Guerrilla Hunter, U.S.A.", Ohio Valley History 18, No. 3 (Fall 2018), pp. 49, 52–53.

- ^ Albert Castel, William Clarke Quantrill His Life and Times, Frederick Fell, 1962, pp. 208–213

- ^ "Replica Head of Confederate Raider Quantrill". Roadside America. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ McKelvie, B.A., Magic, Murder & Mystery, Cowichan Leader Ltd. (printer), 1966, pp. 55–62.; The American West, Vol. 10, American West Pub. Co., 1973, pp. 13–17; Leslie, Edward E., The Devil Knows How to Ride: The True Story of William Clarke Quantrill and his Confederate Raiders, Da Capo Press, 1996, pp. 404, 417, 488, 501.

- ^ Gary Telford. "The Great Quantrill – Crocker Mystery in Augusta, Arkansas". Woodruff County, ARGenWeb. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "Scottie transcript of Emily Hardestys Boylehardesty cassette taped history" (PDF). www.heritagestatic.com.

- ^ "Was It More Restrained Than You Think? Archived August 29, 2018, at the Wayback Machine", James M. McPherson, The New York Review of Books, February 14, 2008

- ^ Matthew Christopher Hulbert, The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory: How Civil War Bushwhackers Became Gunslingers in the American West. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016), pp. 47–48.

- ^ "William Clarke Quantrill Society". Archived from the original on April 27, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

Bibliography

[edit]- The American West, Vol. 10, American West Pub. Co., 1973, pp. 13–17.

- Banasik, Michael E., Cavaliers of the bush: Quantrill and his men, Press of the Camp Pope Bookshop, 2003.[ISBN missing]

- Connelley, William Elsey, Quantrill and the border wars, The Torch Press, 1910 (reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, 2004).[ISBN missing]

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Johnson, Curt, and Bongard, David L., Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, Castle Books, 1992, 1st ed., ISBN 0-7858-0437-4.

- Edwards, John N., Noted Guerillas: The Warfare of the Border, St. Louis: Bryan, Brand, & Company, 1877.

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Gilmore, Donald L., Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas border, Pelican Publishing, 2006. [ISBN missing]

- Hulbert, Matthew Christopher. The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory: How Civil War Bushwhackers Became Gunslingers in the American West. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0820350028.

- Leslie, Edward E., The Devil Knows How to Ride: The True Story of William Clarke Quantrill and his Confederate Raiders, Da Capo Press, 1996, ISBN 0-306-80865-X.

- McKelvie, B.A., Magic, Murder & Mystery, Cowichan Leader Ltd. (printer), 1966, pp. 55–62

- Mills, Charles, Treasure Legends Of The Civil War, Apple Cheeks Press, 2001, ISBN 1-58898-646-2.

- Schultz, Duane, Quantrill's war: the life and times of William Clarke Quantrill, 1837–1865, St. Martin's Press, 1997. ISBN 0-312-16972-8

- Wellman, Paul I., A Dynasty of Western Outlaws, University of Nebraska Press, 1986, ISBN 0-8032-9709-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Castel, Albert E., William Clarke Quantrill, University of Oklahoma Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8061-3081-4.

- Geiger, Mark W. Financial Fraud and Guerrilla Violence in Missouri's Civil War, 1861–1865, Yale University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-15151-0

- Crouch, Barry A. "A 'Fiend in Human Shape?' William Clarke Quantrill and his Biographers", Kansas History (1999) 22#2 pp 142–156 analyzes the highly polarized historiography

External links

[edit]- William Clark Quantrill Society

- Official website for the Family of Frank & Jesse James: Stray Leaves, A James Family in America Since 1650 Archived February 28, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- T.J. Stiles, Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War

- Guerrilla raiders in an 1862 Harper's Weekly story, with illustration

- Quantrill's Guerrillas Members In The Civil War

- Quantrill flag at Kansas Museum of History

- "Guerilla Warfare in Kentucky" – Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush

- Charles W. Quantrell: A True Report of his Guerrilla Warfare on the Missouri and Kansas Border at Project Gutenberg (1923 book of reminiscences by Harrison Trow)

William Quantrill

View on GrokipediaWilliam Clarke Quantrill (July 31, 1837 – June 6, 1865) was an American outlaw and Confederate guerrilla leader during the American Civil War, best known for commanding Quantrill's Raiders in brutal partisan warfare along the Kansas-Missouri border.[1][2] Born in Canal Dover, Ohio, to a Methodist family, Quantrill drifted westward as a young man, working as a schoolteacher and teamster before turning to criminal activities such as horse theft and cattle rustling in Utah Territory and Texas.[3] By 1861, amid escalating border conflicts between pro-Union Jayhawkers and pro-Confederate Bushwhackers, he aligned with the Southern cause, forming a guerrilla band that operated irregularly under Confederate auspices and included future figures like Jesse and Frank James and the Younger brothers.[2][4] Quantrill's most infamous action was the August 21, 1863, raid on Lawrence, Kansas—a stronghold of abolitionists and Union supporters—where approximately 450 raiders killed between 150 and 200 unarmed men and boys, looted businesses, and burned about one-quarter of the town, destroying an estimated $2 million in property (equivalent to over $40 million today).[5][6] This massacre, framed by Quantrill as retaliation for Union General Thomas Ewing's Order No. 11—which forcibly evacuated rural Missouri counties and destroyed homes of suspected Confederate sympathizers—and earlier Jayhawker depredations, nonetheless targeted non-combatants indiscriminately, fueling cycles of reprisal that characterized the region's irregular warfare.[5][4] His band's tactics, blending combat against Union troops with civilian atrocities, earned Quantrill a commission as captain in the Confederate army but also vilification as a terrorist by Union authorities, who offered rewards for his capture.[3] As the war progressed, internal fractures splintered Quantrill's command, with subordinates like "Bloody Bill" Anderson pursuing even more savage independent operations; Quantrill himself shifted east to Kentucky in late 1864, where on May 10, 1865, he was mortally wounded in a skirmish with Union militia near Taylorsville and died shortly after in Louisville.[1][4] Quantrill's legacy remains polarizing: hailed by some Southern sympathizers as a defender against Northern aggression in a theater where conventional rules of war often collapsed, yet condemned broadly for embodying the unchecked violence that claimed thousands of civilian lives in the Trans-Mississippi borderlands.[2][3]