Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Atlantic World

View on Wikipedia

The Atlantic World comprises the interactions among the peoples and empires bordering the Atlantic Ocean rim from the beginning of the Age of Discovery to the early 19th century. Atlantic history is split between three different contexts: trans-Atlantic history, meaning the international history of the Atlantic World; circum-Atlantic history, meaning the transnational history of the Atlantic World; and cis-Atlantic history within an Atlantic context.[1] The Atlantic slave trade continued into the 19th century, but the international trade was largely outlawed in 1807 by Britain. Slavery ended in 1865 in the United States and in the 1880s in Brazil (1888) and Cuba (1886).[2] While some scholars stress that the history of the "Atlantic World" culminates in the "Atlantic Revolutions" of the late 18th early 19th centuries,[3] the most influential research in the field examines the slave trade and the study of slavery, thus in the late-19th century terminus as part of the transition from Atlantic history to globalization seems most appropriate.

The historiography of the Atlantic World, known as Atlantic history, has grown enormously since the 1990s.[4]

Concept

[edit]Geography

[edit]The Atlantic World comprises the histories of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Travel over land was difficult and expensive, so settlements were made along the coast, especially where rivers allowed small boats to travel inland. Distant settlements were linked by elaborate sea-based trading networks. Since the easiest and cheapest way of long-distance travel was by sea, international trading networks emerged in the Atlantic World, with major hubs at London, Amsterdam, Boston, and Havana. Time was a factor, as sailing ships averaged about 2 knots speed (50 miles a day). Navigators had to rely on maps of currents or they would be becalmed for days or weeks.[5] These maps were not only for navigational purposes however, but also as a way to give insight in regards to power and ownership of lands that had already been claimed, essentially creating a greater desire to finding new routes and land.[6] One major goal for centuries was finding the Northwest Passage (through what is now Canada) from Europe to Asia.[7]

Emergence

[edit]

Given the scope of Atlantic history it has tended to downplay the singular influence of the voyages of Columbus and to focus more on growing interactions among African and European polities (ca 1450–1500), including contact and conflict in the Mediterranean and Atlantic islands, as critical to the emergence of the Atlantic World. Awareness of the Atlantic World, of course, spiked post-1492: after the earliest European voyages to the New World and continuing encounters on the African coast, a Euro-centric division of the Atlantic was proclaimed between the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. The West Coast and Central Africa, which are distinct from one another and each made up of many competing polities, played core roles in shaping the Atlantic World and as major sources for slave labor.[8] An elaborate network of economic, geopolitical and cultural exchange took shape—an "Atlantic World" comparable to the "Mediterranean World". It linked the nations and peoples that inhabited the Atlantic litoral of North and South America, the Caribbean, Africa and Europe.

The main empires that built the Atlantic World were the British,[9] French,[10] Spanish[11] , Portuguese[12] and Dutch;[13] entrepreneurs from the United States played a role as well after 1789.[14] Other countries, such as Sweden and Denmark, were active on a smaller scale.

Historical usage

[edit]American historian Bernard Bailyn traces the concept of the Atlantic World to an editorial published by journalist Walter Lippmann in 1917.[15] The alliance of the United States and Great Britain in World War II, and the subsequent creation of NATO, heightened historians' interest in the history of interaction between societies on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.[16] Other scholars emphasize its intellectual origins in the more systematic and less political approach of the French Annales school, especially the influential work by Fernand Braudel on the Mediterranean World (trans. 2 vols, 1973).[17]

In American and British universities, Atlantic World history is supplementing (and possibly supplanting) the study of specific European colonial societies in the Americas, e.g. British North America or Spanish America. Some historians have criticized the North Atlantic emphasis as downplaying the importance of African history and the transatlantic slave trade on Brazilian and Caribbean history. Atlantic World history differs from traditional approaches to the history of European colonization in its emphasis on inter-regional and international comparisons and its attention to events and trends that transcended national borders. Atlantic World history emphasizes how the colonization of the Americas reshaped Africa and Europe, provided a foundation for later globalization, and insists that our understanding of the past benefits from looking beyond the nation state as our primary (or sole) category of analysis.[citation needed]

Aspects

[edit]Environment

[edit]The beginning of extensive contact between Europe, Africa, and the Americas had sweeping implications for the environmental and demographic history of all the regions involved.[18] In the process known as the Columbian Exchange, numerous plants, animals, and diseases were transplanted—both deliberately and inadvertently—from one continent to another. The epidemiological impact of this exchange on the indigenous peoples of the Americas was profound, causing very high death rates and population declines of 50% to 90% or even 100%. European and African immigrants also had very high death rates on their arrival, but they could be and were replaced by new shipments of immigrants (see the Population history of American indigenous peoples). Many foods that are common in present-day Europe, including corn (maize) and potatoes, originated in the New World and were unknown in Europe before the 16th century. Similarly, some staple crops of present-day West Africa, including cassava and peanuts, originated in the New World. Some of the staple crops of Latin America, such as coffee and sugarcane, were introduced by European settlers in the course of the Columbian Exchange.[19]

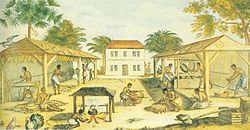

Slavery and labor

[edit]

The slave trade played a role in the history of the Atlantic World almost from the beginning.[20] As European powers began to conquer and claim large territories in the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries, the role of chattel slavery and other forced labor systems in the development of the Atlantic World expanded. European powers typically had vast territories that they wished to exploit through agriculture, mining, or other extractive industries, but they lacked the work force that they needed to exploit their lands effectively. Consequently, they turned to a variety of coercive labor systems to meet their needs. At first the goal was to use native workers. Native Americans were employed through Indian slavery and through the Spanish system of encomienda. Indian labor was not effective on a large scale for complex reasons (e.g., high death rates and relative ease of escape to Native communities), so plantation owners turned to African slaves via the Atlantic slave trade. European workers arrived as indentured servants or transported felons who went free after a term of labor.[21] In short, the Atlantic World was one of widespread inequality where the exploitation of human labor provided the foundation for a small handful of elites to reap enormous profits.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave trade played a massive role in shaping the demographics of the Americas, especially in areas where huge plantations were the norm, such as in Brazil and the Caribbean. Roughly three quarters of immigrants to the Americas before 1820 were African, and more than half of these Africans were originally from West or Central Africa. In Brazil, the population percentage of Africans was even higher, with about seven African to every one Portuguese immigrant.[22] Because there was such a large population of Africans, it is unsurprising that African slaves aided in shaping the culture of these regions. In the early colonial period, there was a high prevalence of African spiritual practices, such as spirit possessions and healing practices. Presumably, these practices served as a point of connection and as an identity hold for slaves hailing from the same African origin.[23] Such cultural practices allowed, at least to an extent, African slaves to maintain kinship structures similar to those that they might have seen in their homeland. In many cases, European authorities viewed spiritual positions that were highly esteemed in African societies to be socially unacceptable, morally corrupt, and heretical. This led to the disappearance or transformation of most African religious practices. For example, the practice of consulting kilundu, or Angolan spirits, was seen as homosexual by Portuguese authorities,[23] a clear example of Eurocentrism in colonial societies, as European ideas of religion often did not match African ones. Unfortunately, there is a lack of documents written from the African point of view, so almost all information from this time period in these colonial societies is subject to cross-cultural misinterpretation, omission of facts, or other such changes that could affect the quality of description of African spiritual practices. Maintaining the integrity of cultural practices was difficult due to disagreement with European propriety and European tendency to generalize the African demographic makeup to merely "Central African", rather than acknowledging individual cultures. Eventually, most African traditions such as Kilundu, which was ultimately reduced to the popular Brazilian dance "Lundu", were either absorbed into other African traditions or reduced to a ritual simply resembling the original tradition.[22]

The extent of voluntary immigration to the Atlantic World varied considerably by region, nationality, and time period. Many European nations, particularly the Netherlands and France, only managed to send a few thousand voluntary immigrants. Though 15,000 or so who came to New France multiplied rapidly. In New Netherland, the Dutch coped by recruiting immigrants of other nationalities.[24] In New England, the massive Puritan migration of the first half of the 17th century created a large free workforce and thus obviated the need to use unfree labor on a large scale. Colonial New England's reliance on the labor of free men, women, and children, organized in individual farm households, is called the yeoman or household labor system.[25] There is an important distinction to be made between "societies with slaves", such as colonial New England, and "slave societies", where slavery was so central that it can properly be said to define all aspects of life in that region.[26]

The French colony of Saint-Domingue was one of the first American jurisdictions to end slavery, in 1794. Brazil was the last nation in the Western Hemisphere to end slavery, in 1888.

Governance

[edit]

The Spanish conquistadores conquered the Aztec Empire, more accurately now referred to by scholars as the Mexica empire[citation needed], in present-day Mexico, and the Inca Empire, in present-day Peru, with surprising speed, assisted by horses, guns, large numbers of Native allies, and, perhaps above all, by the devastating mortality inflicted by newly introduced diseases such as smallpox. To some extent the prior emergence of the large and wealthy Inca and Mexica civilizations aided the transfer of governance to the Spanish, since these native empires had already established road systems, state bureaucracies and systems of taxation and intensive agriculture that were often inherited wholesale and then modified by the Spanish. The early Spanish conquerors of these empires were also aided by political instability and internal conflict within the Mexica and Incan regimes, which they successfully exploited to their benefit.[27]

One of the problems that most European governments faced in the Americas was how to exercise authority over vast expanses of territory.[28] Spain, which colonized Mexico, Central America, and the greater part of South America, established a network of powerful viceroyalties to administer different regions of its New World holdings: the Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535), the Viceroyalty of Peru (1542), the Viceroyalty of New Granada (1717–1739), and the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata (1776). The result was strong government that became even stronger during the Bourbon reforms of the 18th century.[29]

Britain approached the task of governing its New World territories in a less centralized manner, establishing about twenty distinct colonies in North America and the Caribbean from 1585 onward.[30] Each British colony had its own governor and most would have representative assemblies. Most of the North American Thirteen Colonies that became the United States had strong self-government via popular assemblies that countered the authority of governors with their own assertions of rights via parliamentary and other English sources of authority. Only property owners could vote in British polities, but since so many free men in mainland British Colonial America owned land, a majority could vote and participate in popular politics. The British challenge to the authority of colonial assemblies, especially via taxation, was a major cause of the American Revolution in the 1770s.[31]

"Atlantic Revolutions"

[edit]

A wave of revolutions shook the Atlantic World from the 1770s to the 1820s, including in the United States (1775–1783), France and French-controlled Europe (1789–1814), Haiti (1791–1804), and Spanish America (1806–1830).[32] There were smaller upheavals in Switzerland, Russia, and Brazil. The revolutionaries in varied places were aware of recent anti-colonial struggles in other Atlantic societies and even interacted with one another in many cases.[33]

Independence movements in the New World began with the American Revolution, 1775–1783, in which France, the Netherlands and Spain assisted the new United States of America as it secured independence from Britain. In August 1791 a coordinated slave uprising in the wealthy French sugar colony of St. Domingue began the Haitian Revolution. A long and destructive period of international warfare there came to a close with the creation of Haiti as an independent black republic in 1804. It has a complex and contested legacy as the largest successful slave revolt in history and was accompanied by widespread violence. With Spain tied down in European wars, the mainland Spanish colonies waged independence movements over a long period from 1806 to 1830, sometimes inspired by, but often fearful of, the Haitian example, which delayed effective independence movements in the slave societies of the Caribbean and Brazil until the late-19th century and later.[34]

In long-term perspective, the revolutions were mostly successful. They spread widely the ideals of republicanism, the overthrow of aristocracies, kings and established churches. They emphasized the universal ideals of The Enlightenment, such as the equality of all men. They emphasized equal justice under law by disinterested courts, as opposed to particular justice handed down at the whim of a local noble. They showed that the modern notion of revolution, of starting fresh with a radically new government, could actually work in practice. Revolutionary mentalities were born and continue to flourish to the present day.[35] When assessed in comparative perspective, the American Revolution (and especially the Federal Constitution that protected slavery as a legal institution) seems less radical and with a more oligarchic outcome than when viewed through a traditional nationalistic lens.

See also

[edit]- Atlantic history, on the historiography of the Atlantic World

- Age of Discovery

- Atlantic slave trade

- Atlantic Revolutions

- Colonial America

- Portuguese Empire

- Dutch Empire

- European colonization of the Americas

- French colonization of the Americas

- New France

- New Netherland

- New Spain

- Piracy in the Atlantic World

- Early modern Britain

- Atlantic Creole

- Transatlantic migrations

- Transatlantic relations

- Influence of the American Revolution on the French Revolution

References

[edit]- ^ Armitage, David (2002). "The Concepts of Atlantic History". In Armitage, David; Braddick, Michael J. (eds.). The British Atlantic World 1500–1800.

- ^ David Eltis, et al. Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (2010)

- ^ Wim Klooster, Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History (2009)

- ^ Alison Games and Adam Rothman, eds., Major Problems in Atlantic History: Documents and Essays (2007)

- ^ Peggy K. Liss, Atlantic Empires: The Network of Trade and Revolution, 1713-1826 (Johns Hopkins Studies in Atlantic History and Culture) (1982)

- ^ Schmidt, Benjamin (1997). "Mapping an Empire: Cartographic and Colonial Rivalry in Seventeenth-Century Dutch and English North America". The William and Mary Quarterly. 54 (3). Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 549–578. doi:10.2307/2953839. JSTOR 2953839.

- ^ Pierre Berton, The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the Northwest Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909 (2000)

- ^ John Kelly Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1680 (2nd ed. 1998)

- ^ H. V. Bowen, et al. Britain's Oceanic Empire: Atlantic and Indian Ocean Worlds, c. 1550-1850 (2012) excerpt and text search

- ^ Kenneth J. Banks, Chasing Empire Across the Sea: Communications And the State in the French Atlantic, 1713-1763 (2006)

- ^ Richard L. Kagan and Geoffrey Parker, eds. Spain, Europe and the Atlantic (2003), specialized essays excerpt and text search

- ^ Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert, A Nation upon the Ocean Sea: Portugal's Atlantic Diaspora and the Crisis of the Spanish Empire, 1492-1640 (2007) excerpt and text search

- ^ Joyce D. Goodfriend, et al. eds. Going Dutch: The Dutch Presence in America 1609-2009 (Atlantic World) (2008)

- ^ Eliga H. Gould and Peter S. Onuf, eds. Empire and Nation: The American Revolution in the Atlantic World (Anglo-America in the Transatlantic World) (2005) excerpt and text search

- ^ Bailyn, Atlantic History, 6-7.

- ^ Bailyn, Atlantic History, 9.

- ^ Alison Games, "Atlantic History: Definitions, Challenges, and Opportunities". American Historical Review. 111 (June 2006), 741-757

- ^ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2010). "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 24 (2): 163–188. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.232.9242. doi:10.1257/jep.24.2.163. JSTOR 25703506.

- ^ Timothy Silver, A New Face on the Countryside: Indians, Colonists, and Slaves in South Atlantic Forests, 1500-1800 (Studies in Environment and History) (1990)

- ^ Hugh Thomas, The slave trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440-1870 (2006) excerpt and text search

- ^ Morgan, Kenneth (2000). Slavery, Atlantic Trade and the British Economy, 1660-1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521588140.

- ^ a b Sweet, James H. "The Evolution of Ritual in the African Diaspora". (n.d.): 64-80. Web.

- ^ a b Sweet, James H. "Mutual Misunderstandings: Gester, Gender, and Healing in the African Portuguese World". Past and Present 4th ser. (2009): 128-43. Web.

- ^ Jaap Jacobs, New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America (The Atlantic World) (2004)

- ^ Francis J. Bremer, First Founders: American Puritans and Puritanism in an Atlantic World (2012)

- ^ Ira Berlin, "Generations of Captivity: A History of African American Slaves" (2003)

- ^ John Huxtable Elliott, Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 (2007)

- ^ Jacob Cooke, ed., Encyclopedia of the North American Colonies (1993) vol 1

- ^ Elliott, Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830 (2007)

- ^ Vickers, Daniel, ed. (2003). A Companion to Colonial America. Wiley Blackwell Companions to American History. ISBN 978-0631210115.

- ^ Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole, eds.. A Companion to the American Revolution (Blackwell, 2003) excerpt and text search

- ^ Wim Klooster, Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History (2009)

- ^ Laurent Dubois and Richard Rabinowitz, eds. Revolution!: The Atlantic World Reborn (2011)

- ^ Rodríguez O., Jaime E. (1998). The Independence of Spanish America. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511721137. ISBN 9780521622981.

- ^ Robert R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760–1800. (2 vol, 1959–1964)

Further reading

[edit]- Altman, Ida. Emigrants and Society: Extremadura and Spanish America in the Sixteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

- Altman, Ida. Transatlantic Ties in the Spanish Empire: Brihuega, Spain, and Puebla, Mexico, 1560-1620. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Altman, Ida and James J. Horn, eds. "To Make America": European Emigration in the Early Modern Period. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

- Altman, Ida and David Wheat, eds. The Spanish Caribbean and the Atlantic World in the Long Sixteenth Century. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2019. ISBN 978-0803299573

- Armitage, David, and Michael J. Braddick, eds., The British Atlantic World, 1500-1800 (2002)

- Cañeque, Alejandro. "The Political and Institutional History of Colonial Spanish America" History Compass (April 2013) 114 pp 280–291, DOI: 10.1111/hic3.12043

- Canny, Nicholas, and Philip Morgan, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Atlantic World: 1450-1850 (2011)

- Cooke, Jacob Ernest et al., eds. Encyclopedia of the North American Colonies (3 vol. 1993); 2397 pp.; comprehensive coverage of British, French, Spanish & Dutch colonies

- Egerton, Douglas, Alison Games, Kris Lane, and Donald R. Wright. The Atlantic World: A History, 1400-1888. (Harlan Davidson, 2007); a broad overview

- Falola, Toyin, and Kevin D. Roberts, eds. The Atlantic World, 1450–2000 (Indiana U.P. 2008), a broad overview with an emphasis on race

- Games, Alison and Adam Rothman, eds. Major Problems in Atlantic History: Documents and Essays (2007), 544pp; primary and secondary sources

- Greene, Jack P., Franklin W. Knight, Virginia Guedea, and Jaime E. Rodríguez O. "AHR Forum: Revolutions in the Americas". American Historical Review (2000) 105#1 92–152. Advanced scholarly essays comparing different revolutions in the New World. in JSTOR

- Kagan, Richard and Geoffrey Parker, Spain, Europe and the Atlantic: Essays in Honour of John H. Elliott. New York: Cambridge University Press 2003.

- Klooster, Wim. Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History (2009)

- Klooster, Wim. The Dutch Moment: War, Trade, and Settlement in the Seventeenth-Century Atlantic World. (Cornell University Press, 2016). 419 pp.

- Liss, Peggy K. Atlantic Empires: The Network of Trade and Revolution, 1713-1826 (Johns Hopkins Studies in Atlantic History and Culture) (1982)

- Mark, Peter and José da Silva Horta, The Forgotten Diaspora: Jewish Communities in West Africa and the Making of the Atlantic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2011.

- Noorlander, D. L. "The Dutch Atlantic world, 1585–1815: Recent themes and developments in the field." History Compass (2020): e12625.

- Palmer, Robert R. The age of the democratic revolution: a political history of Europe and America, 1760-1800 (Princeton UP, 1959); vol. 2 (1964) online edition volume 1-2

- Pestana, Carla Gardina. Protestant Empire: Religion and the Making of the British Atlantic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press 2009.

- Racine, Karen, and Beatriz G. Mamigonian, eds. The Human Tradition in the Atlantic World, 1500–1850 (2010) excerpt and text search

- Savelle, Max. Empires To Nations: Expansion In America 1713-1824 (1974) online

- Seed, Patricia. Ceremonies of Possession in Europe's Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Taylor, Alan. American Colonies. New York: Viking, 2001.

- Thornton, John. Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1680. (1998) excerpt and text search

External links

[edit]- Atlantic History Seminar, Harvard University

- The Atlantic World: America and the Netherlands, sponsored by the Library of Congress

- Slavery Images: A Visual Database, originally at the Univ. of Virginia, now hosted by Univ. of Colorado Boulder

- The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, Emory University

- Vistas, Spanish American visual culture, 1520-1820, Smith College