Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

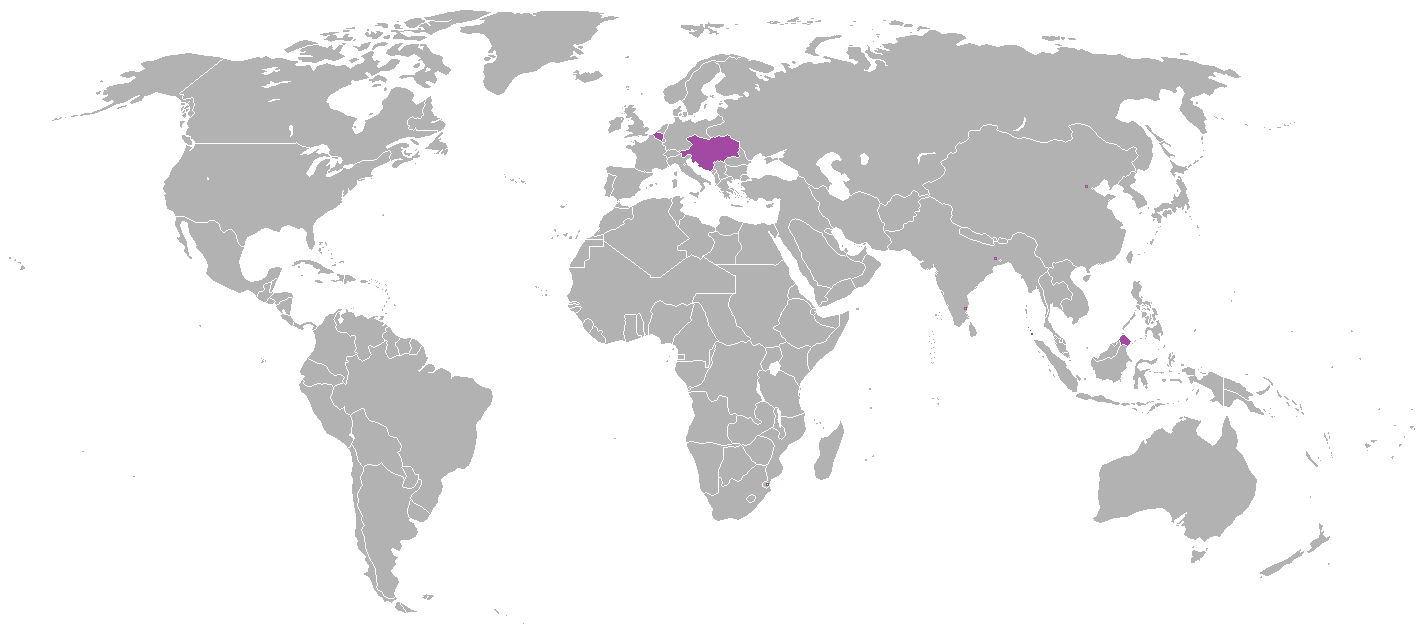

Austrian colonial policy

View on Wikipedia

From the 17th century through to the 19th century, the Habsburg monarchy, Austrian Empire, and (from 1867 to 1918) the Austro-Hungarian Empire made a few small short-lived attempts to expand overseas colonial trade through the acquisition of factories. In 1519–1556 Austria's ruler also ruled Spain, which did have a large colonial empire.

The colonial domains of the dual monarchy Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918, are covered in Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Keeping it under control was a major factor in Austro-Hungarian entry into World War I in 1914. All the other small attempts were ended due to international pressure, or lack of interest from the Imperial government and opposition from Hungarians high in the government.

Ostend East India Company

[edit]

The Ostend East India Company was a private merchant company formed in 1715, based in the Southern Netherlands in what is now Flemish Belgium. The Emperor provided the company with 6 million guilders, as a public-private monopoly with 6,000 shares, set at 1,000 guilders each.[1] Due to the speed of the Ostender's trade ships, the company, within a couple of years became one of the largest trading firms in the East and Canton.[1] By 1720, the Ostend Company had been transporting 7 million pounds of tea, which was about 41.78% of the tea traded from the Port of Canton.[2][1]

The private Ostend Company consisted of two Flemish brothers-in-law, Paulo Cloots and Jacomo de Pret, who formed a consortium with two Dutch merchant houses of De Bruyn and Geelhand; Cloots and de Pret also invited the two London houses of Hambly and Trehee, and the French baker Antoine Crozat to invest in the company.[1] After seven years of profitable ventures, and much fighting between other merchants in Antwerp and Ghent, Charles VI agreed to its petition of official charter.[1]

In 1715, the Ostend Company acquired trading charters in the ports of Mocha, Surat, and Canton.[2] In 1723, the Ostender's obtained trading ports in the lucrative harbors of Banquibazar and Cabelon.[3] The trade missions to Mocha were initially successful, but due to the wreck of the Mochaman, a trade vessel headed to the Red Sea in 1720, and the capture of a home-bound vessel by the Barbary Pirates in 1723, Mocha eventually turned into a heavy loss.[1] The ports of Surat and Canton however, continued to be quite profitable. All the profits went to the Southern Netherlands and none to Austria.

The company had become such a threat to British, Dutch, Portuguese, and French interests, that when Emperor Charles VI promulgated the edict of the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, it was refused international recognition on the grounds of Ostend Company's success in the East Indies. These International political pressures ended its extraordinary growth, and in 1727 the charter was suspended, leading to the company being dissolved by 1732.

After the Imperial government's withdrawal of the Ostend Company's charter, the Great Powers accepted the Pragmatic Sanction. The suspension also allowed the Austrians to sign the Treaty of Vienna (1731) with the British; which allied both powers in the Anglo-Austrian Alliance.[1]

Maputo Bay

[edit]Maputo Bay, formerly also known as Delagoa Bay from Baía da Lagoa in Portuguese, is an inlet of the Indian Ocean on the coast of Mozambique. In 1776, an expelled British trade official, Colonel William Bolts, approached the Austrian Imperial Court with a request to found a trading company to explore possible routes in Africa, India, and China.[4] Empress Maria Theresa was intrigued and decided to form the Austrian Asiatic Company of Trieste, with Bolts as the head of the company. Colonel Bolts had previously been under the service of the British East India Company and was already competent in trade and colonization efforts. Bolts had also heard that the area was a possible site for gold mining.[5]

Sailing from Flanders in 1778, Bolts and his company of Austrian-Italian subjects, the Austrian ship Joseph und Theresia of the Austrian East India Company docked in Delagoa Bay in 1779. Bolts then made treaties with the local Mabudu chieftains, who inhabited the port.[6] Austrians erect the St. Joseph and St. Maria forts, A trading post (factory) was built, and the factory quickly began to thrive under Austrian rule, also due to their participation in the slave trade.[7] Bolts shortly after, set sail to promote Austrian interests in India. After two years, the factory, which was composed of 155 men and a number of women, traded in ivory, and profits reached as high as 75,000 pounds per year.[8] The factory was expelled by the Portuguese in 1781.

The Austrian presence in Delagoa Bay caused the ivory price to change dramatically. This was due to the Austrian output, which exceeded that of the Portuguese in Mozambique Island.[4] Unfortunately for the Austrians, the port contracted malaria in 1781, and the Portuguese successfully asserted their dominance of the area; the Portuguese then proceeded to expel the remainder of Austrian colonists.[6]

Multiple attempts in the Nicobar Islands

[edit]First attempt

[edit]After William Bolts' mission in Delagoa Bay, he directed a venture to the Nicobar Islands. This mission was a part of his colonial ventures in India; and in 1778, Gottfried Stahl and his crew arrived on the ship Joseph und Theresia.[9] Stahl greeted the natives personally and made a contract with the Nicobarese, where all twenty-four islands were to be signed over to the Austrians. The colonization effort was successful until Stahl, whom Bolts had appointed as head of the colony, died in 1783. The colonists lost courage in their settlement attempts, and the islands were abandoned in 1785.[9][7]

Second attempt and expedition

[edit]Seventy-three years later in 1858, the SMS Novara, then on its circumnavigation of the globe, decided to sail to Nicobar. SMS Novara landed in Car Nicobar, the northernmost island, and its purpose was to promote scientific exploration and included the search for possible penal colonies.[9] The leader of the group, Karl von Scherzer, promoted re-colonization. Austrian scientists and archaeologists then explored the islands of Nancowry and Kamorta and collected over 400 artifacts native to the islands.[9] The Austrian government decided against Von Scherzer's recommendations, and closed all potential colonial opportunities.

Third attempt

[edit]In 1886, the Austrians became interested in another possible colonization attempt. When the crew arrived on the island of Nancowry with the corvette SMS Aurora, they were surprised to find the entire Nicobar Island chain had been colonized by the British several years earlier.[9] In 1868, the British purchased the claims to the Nicobar Islands from the Danish and established it as a penal colony for several years.[10] This ended all further possibilities to colonize the area.

Exploration of Franz-Joseph's Land

[edit]

In 1873, an Austrian expedition, according to its leader Julius von Payer, was sent to the North Pole tasked with finding the Northeast Passage.[11] The expedition actually ended up close to the Novaya Zemlya archipelago, the easternmost point of Europe. Karl Weyprecht, the expedition's secondary leader, claimed the second intended destination after the Northeast Passage was the North Pole.[12]

The cost of the journey is estimated to be around 175,000 florins. The project was promoted and financially supported by several Austrian and Hungarian noblemen, which included Count Johann Nepomuk Wilczek and Count Ödön Zichy.[13] The head-ship was named after the Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff. The Tegetthoff weighed 220 tonnes, 125.78 feet long (38.34 m.), and had a 100 horsepower (75 kW) steam engine).[14]

The Tegetthoff left port at Tromsø, Norway in July 1872. Soon after arriving in the Arctic Circle, the Tegetthoff became locked in pack ice and drifted for the remainder of their journey.[11] While drifting within the ice, the explorers discovered an archipelago and decided to name it after the then-current Emperor Franz Joseph. The crew later was able to dock and performed several sled expeditions on the island chain.[13]

Two years later in May 1874, Captain Weyprecht decided to abandon the ice-locked Tegetthoff and believed the crew could return to the mainland by sleds and boats.[12] On 14 August, the expedition reached the open sea. The expedition then arrived at Novaya Zemlya, where a Russian fishing vessel rescued them. The crew was dropped off in Vardø, Norway; and were able to arrive in Austria-Hungary by train from Hamburg.[11]

Berlin Conference of 1884–1885

[edit]

The Berlin Conference was held to settle matters of African colonization, particularly regarding the Congo territory and West Africa. Austria-Hungary was only invited to the Conference due to its status as a great power.[15] While Austria did not petition for any permanent colonies or treaty ports, it did acquire some indirect benefits. Imre Széchényi, serving as one of the head members of the Conference, was able to procure the privilege of free docking rights in all European-controlled ports in Africa except for those in the British Cape Colony, Italian Somaliland and French Madagascar.[citation needed]

North Borneo

[edit]In 1877, a Hong Kong-based merchant sold his rights to North Borneo to the consul of the Austro-Hungarian Empire based in that city, Baron Gustav von Overbeck. In 1878 Gustav von Overbeck bought land from the sultanates of Brunei and Sulu; and acquired additional land from the American Borneo Trading Company, to form what was then known as the North Borneo protectorate. A friend of Overbeck's, William Clarke Cowie, had influence with the Sulu Sultanate, allowing him the January 22, 1878 purchase yet more land to add to North Borneo protectorate.

Following these purchases, Overbeck traveled to Europe, where he then attempted to sell off the newly created North Borneo by promoting it as a penal colony. He reached out to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the United Kingdom, the German Empire, and Kingdom of Italy. Due to a general lack of interest, Overbeck later sold these lands to Alfred Dent, a British colonial merchant who later formed the British North Borneo Company in 1880. A year later, the United Kingdom revived interest in the territory and then purchased North Borneo from Dent in 1881.

North Borneo could technically be considered an Austrian colony for one reason. Baron von Overbeck, though German, was the Austro-Hungarian consul in Hong Kong, so control of Borneo under an Austrian citizen would define it as a possession of Austria-Hungary.[citation needed]

Rio de Oro

[edit]After the humiliation in the Spanish–American War, Spain wished to divest itself of its colonies, and in 1898, Spanish diplomats approached the Austro-Hungarian Colonial Society about a possible purchase of the trading port of Rio de Oro. The society's vice-president, Ernst Weisl, made a quiet deal with Agenor Goluchowski, the Minister of Foreign Affairs for Austria.[16] Goluchowski later convinced the Austrian Imperial Council, and Emperor Franz Joseph openly supported the deal. However, the success of the business, which promised significant profits, was hindered by the Monarchy’s unwillingness to invest public funds [17]

The process faced significant setbacks, primarily due to internal disagreements among economic groups and the government. The government initially wanted to negotiate directly with the Spanish, but there was a lack of consensus on who should lead the talks. Proposals included using the Austrian-Hungarian Colonial Society or prominent figures like Austrian Commerce Minister Baron Josef De Paoli or businessman Arthur Krupp, but these were met with obstacles. De Paoli sought the involvement of Foreign Minister Agenor Goluchowski, while Krupp rejected the offer due to past failures in Somalia. [18]

By the end of 1899, the negotiations stalled, with neither the government nor business circles willing to invest the necessary funds. The Spanish continued waiting for an offer from Austria-Hungary, despite interest from other countries, including Germany, Britain, France, and Italy, in the territory. Ultimately, the Spanish began talks with the French, who sought to acquire Rio de Oro to expand their colonial holdings in North Africa. However, public opinion in Spain shifted, and the government eventually decided against selling the territory.[19]

Port of Tianjin

[edit]

Austria-Hungary participated in the Eight-Nation Alliance from 1899 to 1901. This grand alliance was formed to contain the Boxer Rebellion in China.[20] The Austro-Hungarian Navy helped in suppressing the rising. However, Austria-Hungary sent the smallest force of any nation. Only four cruisers and a force of only 296 marines were dispatched.[21]

Even so, on 27 December 1902, Austria gained a concession zone in Tianjin as part of the reward for its contribution to the Alliance.[22][23] The Austrian concession zone was 150 acres (0.61 km2) in area; which was slightly larger than the Italian, but smaller than the Belgian zone. The self-contained concession had its own prison, school, barracks, and hospital.[22] It also contained the Austro-Hungarian consulate and its citizens were under Austrian, not Chinese, rule.[22]

The concession was provided with a small garrison, and Austria-Hungary proved unable to maintain control of its concession during the Great War. The concession zone was swiftly occupied on the Chinese declaration of war on the Central Powers.[22] On 14 August 1917 the lease was terminated, (along with that of the larger German concession in the same city).

Austria abandoned all claims to Tianjin on 10 September 1919.[24] Hungary also made a similar recognition in 1920.[24] However, despite its relatively short life-span of 15 years, the Austrians left their mark on that area of the city, as can be seen in the Austrian architecture that still stands in the city.[25]

List of consuls

[edit]- Carl Bernauer: 1901–1908

- Erwin Ritter von Zach: 1908

- Miloš Kobr: 1908–1912

- Hugo Schumpeter: 1913–1917

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Parmentier, Jan. "Ostend East India Company". Encyclopedia.com: History of World Trade Since 1450. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Davids, Karel (November 1993). "Jaap R. Bruijn and Femme S. Gaastra, Ships, Sailors and Spices: East India Companies and their Shipping in the 16th, 17th and 18th century. Amsterdam (NEHA) 1993. XI + 208 pp. ISBN 90-71617-69-6". Itinerario. 20 (3): 147. doi:10.1017/s0165115300004046. ISSN 0165-1153. S2CID 197836826.

- ^ Parmentier, Jan (December 1993). "The Private East India Ventures from Ostend: The Maritime and Commercial Aspects, 1715–1722". International Journal of Maritime History. 5 (2): 75–102. doi:10.1177/084387149300500206. ISSN 0843-8714. S2CID 130707436.

- ^ a b Kloppers, Roelie J. (2003). THE HISTORY AND REPRESENTATION OF THE HISTORY OF THE MABUDU-TEMBE. SUNScholar Research Repository (Thesis). Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ C., F. R.; Bryant, A. T. (January 1930). "Olden Times in Zululand and Natal, Containing Earlier Political History of the Eastern Nguni Clans". The Geographical Journal. 75 (1): 79. Bibcode:1930GeogJ..75...79C. doi:10.2307/1783770. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1783770.

- ^ a b Liesegang, Gerhard (1970). "Nguni Migrations between Delagoa Bay and the Zambezi, 1821-1839". African Historical Studies. 3 (2): 317–337. doi:10.2307/216219. ISSN 0001-9992. JSTOR 216219.

- ^ a b Ambach, Florian (2022). "Habsburgs in the Indian Ocean. A Commercial History of the Austrian East India Company and its Colonies and Bases in East Africa, India, and China, 1775–1785". Global Histories: A Student Journal. 8 (2). doi:10.17169/GHSJ.2022.540. ISSN 2366-780X.

- ^ D., Newitt, M. D. (1995). A history of Mozambique. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253340061. OCLC 27812463.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Steger, Philipp (2005). "The Nicobar Islands: Linking Past and Future". University of Vienna. Archived from the original on 2018-12-18. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Lowis, R. F. (1912) The Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Part I. Report. Part II. Tables.

- ^ a b c von Payer, Julius (1876). New Lands within the Arctic Circle. England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139151573.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Weyprecht, Karl (1875). The Austro-Hungarian Expedition of 1872-1874. Austria. ISBN 9783205796060.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Johan., Schimanski (2014). Passagiere des Eises Polarhelden und arktische Diskurse 1874. Spring, Ulrike. (1. Aufl ed.). Wien: Böhlau Wien. ISBN 9783205796060. OCLC 879877160.

- ^ Johan., Schimanski (2014). Passagiere des Eises Polarhelden und arktische Diskurse 1874. Spring, Ulrike. (1. Aufl ed.). Wien: Böhlau Wien. ISBN 9783205796060. OCLC 879877160.

- ^ "MITTEILUNG V. Berliner Konferenz "Die Persönlichkeit in der Wissenschaft"". Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie. 33 (7): 672. 1985-01-01. doi:10.1524/dzph.1985.33.7.672. ISSN 2192-1482.

- ^ Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867-1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. Purdue University Press. pp. 147, 148. ISBN 9781557530349.

- ^ Fülöp, Sándor. "[1]Hand-made Austro-Hungarian Maps of the Rio de Oro Coast". Journal of Central European and Eastern European African Studies, 2021

- ^ Besenyő, János. "[2]Az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia lehetséges afrikai gyarmata: Rio de Oro". Repository of the Academy's Library, 2018

- ^ Besenyő, János. "[3]Az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia lehetséges afrikai gyarmata: Rio de Oro". Repository of the Academy's Library, 2018

- ^ Hall Gardner (2016). The Failure to Prevent World War I: The Unexpected Armageddon. Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-317-03217-5.

- ^ "Russojapanesewarweb". Russojapanesewar.com. 1 July 1902. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d Bristol, University of. "Bristol University | Tianjin under Nine Flags, 1860-1949 | Austro-Hungarian Concession". www.bristol.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2018-12-23. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- ^ Jovanovic, Miloš (2017). "Tianjin's Imperial Discomfort". www.mmg.mpg.de. Archived from the original on 2018-12-23. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

- ^ a b Santangelo, Jon (16 May 2017). "A 5 Minute History of the 10 Concessions of Tianjin". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

- ^ "China VII: Concessions in China - Nine Concessions in Tianjin". www.travelanguist.com. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

Further reading

[edit]- Sauer, Walter. "Habsburg Colonial: Austria-Hungary's Role in European Overseas Expansion Reconsidered," Austrian Studies (2012) 20:5-23 ONLINE

Austrian colonial policy

View on GrokipediaEighteenth-Century Commercial Ventures

Ostend East India Company

The Ostend East India Company, officially the Generale Indische Compagnie (General Indian Company), was established through a charter granted by Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI on 17 December 1722, authorizing trade from the port of Ostend in the Austrian Netherlands to Asia, including the East Indies, China, and parts of West Africa.[4] The company received a 30-year monopoly on these routes for Austrian subjects, mirroring privileges held by rivals like the Dutch VOC and British EIC, with the aim of boosting Habsburg commerce amid post-War of Spanish Succession recovery.[5] Prior to formal organization, private Flemish merchants from Ostend, Antwerp, and Ghent had dispatched vessels to Mocha, India, Bengal, and China since 1715, conducting unregulated trade that laid groundwork for the chartered entity.[4] Between 1723 and 1731, the company operated 12 ships, establishing temporary trading factories in regions such as Bengal and Canton, focusing on exports of textiles, spices, and tea while importing bullion and goods to Europe.[4] Initial voyages yielded profits, with supercargoes negotiating directly at Asian ports despite lacking naval escorts, but competition intensified as Dutch and British forces seized Ostend vessels and blockaded routes.[6] European rivals, viewing the upstart as a threat to their monopolies, mounted diplomatic opposition; Britain and the Dutch Republic protested vehemently, leveraging alliances to pressure Vienna.[7] Facing escalating tensions, Charles VI suspended the company's charter on 31 May 1727 via the Treaty of Paris, halting operations for seven years in exchange for assurances from Britain and Prussia supporting the Pragmatic Sanction to secure his daughter Maria Theresa's succession.[8] This concession reflected Habsburg prioritization of continental dynastic stability over overseas commerce, as Austria lacked a blue-water navy to defend trade lanes.[7] The suspension proved terminal; residual activities dwindled amid ongoing seizures, and the company was definitively dissolved in 1731 under the Treaty of Vienna, which formalized its suppression to appease maritime powers.[4] The Ostend venture underscored Austria's marginal role in global trade imperialism, achieving no permanent colonies or territorial claims despite commercial promise, and reinforced a Habsburg shift toward European-focused policies rather than sustained colonial expansion.[9] Investors, including Flemish entrepreneurs and foreign backers, suffered losses from unrecovered assets, though some redirected efforts to neutral flags like Prussian or Swedish companies.[10]Nicobar Islands Attempts

In 1775, Dutch-born merchant William Bolts, previously dismissed from the British East India Company, secured a ten-year imperial charter from Empress Maria Theresa to establish Austrian trade routes to Asia, including provisions for territorial acquisitions.[11] Bolts proposed leveraging Trieste as a base for direct commerce with India and China, bypassing established European monopolies. This initiative culminated in a colonial venture targeting the Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal, which Bolts viewed as strategically positioned for trade in spices, coconuts, and other goods, under the mistaken assumption that prior Danish claims from the mid-18th century had lapsed.[12] The primary expedition departed in 1778 aboard the imperial vessel Joseph und Theresia, carrying Lieutenant Gottfried Stahl, whom Bolts appointed to lead settlement efforts, along with approximately 20 European workers, seeds, livestock, and supplies for establishing plantations and a trading post. Stahl anchored at Nancowry (also spelled Nankauri) in April 1778, hoisted the Austrian flag, and negotiated a treaty with local Nicobarese chiefs, purporting to cede all 24 islands of the archipelago in exchange for protection and trade privileges. The settlers constructed basic structures on Nancowry, introduced European crops and animals, and renamed one island Theresia in honor of the empress, aiming to develop it as a refreshment station for ships en route to India. Initial reports indicated amicable relations with indigenous populations, who numbered around 5,000-10,000 across the islands and subsisted on fishing, coconut cultivation, and inter-island trade.[13][12] The colony faltered rapidly due to endemic tropical diseases such as malaria and dysentery, exacerbated by the islands' humid climate and isolation, which hindered resupply from Europe; settlers suffered high mortality, with limited medical knowledge and provisions proving insufficient. Stahl's death in 1783 from illness left the remaining colonists leaderless and demoralized, prompting their evacuation by Danish vessels to India by 1785, after which the Habsburg court formally relinquished claims. No significant economic output materialized, as plantations yielded minimal returns before abandonment, underscoring Austria's logistical constraints in sustaining distant overseas ventures amid continental priorities and naval limitations. Subsequent surveys, including those during the 1857-1859 Novara expedition, confirmed the site's inhospitality for European settlement, reinforcing the failure's attribution to environmental and operational factors rather than native hostility.[14][13][12] Later Habsburg interests in the Nicobars, such as exploratory visits in the 1880s, did not revive colonization, as geopolitical realities—including British dominance in the region—precluded further action; Danish rights were transferred to Britain in 1868, formalizing European control under London. These episodes highlight the Austrian monarchy's episodic, commercially driven forays into imperialism, constrained by inadequate infrastructure and competing domestic demands.[13]Mid-to-Late Nineteenth-Century Explorations

Franz Joseph Land Expedition

The Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition, conducted from 1872 to 1874, represented Austria-Hungary's most ambitious Arctic venture under leaders Julius Payer, the naval commander, and Karl Weyprecht, the scientific director. Funded primarily by Count Johann Nepomuk Wilczek and supported by Emperor Franz Joseph I, the expedition's primary objectives included probing the Northeast Passage along Siberia's northern coast, attaining high Arctic latitudes toward the North Pole, and gathering systematic meteorological, magnetic, and oceanographic data to advance polar science.[15][16] The barque Tegetthoff, a wooden three-masted schooner reinforced for ice navigation and displacing 200 tons, carried a crew of 24, including engineers, naturalists, and artists, departing Vienna by train on 13 June 1872 en route to Bremerhaven for final provisioning before sailing north.[15][17] After navigating past Novaya Zemlya in late August 1872, the Tegetthoff became beset in pack ice at 77°28'N, initiating an uncontrolled drift northward over 18 months, reaching a farthest north of 82°49'N by April 1874. During this period, the crew endured severe hardships, including scurvy outbreaks that claimed three lives and forced reliance on bear meat and improvised rations. On 30 August 1873, amid the drift, Payer sighted an unknown archipelago, which the expedition mapped over subsequent months, naming it Franz Joseph Land in honor of the emperor after identifying over 70 islands through sledge journeys and balloon ascents.[15][17] Payer formally claimed the territory for Austria-Hungary by raising the national flag on Wilczek Island and inscribing possession notices, envisioning potential stations for further exploration or whaling support, though no settlements were established due to the ice-bound conditions and logistical limits.[17][18] Exploration efforts focused on Cape Austria, the northernmost point reached at approximately 81°30'N, and included geological surveys revealing sedimentary rocks and fossil evidence, alongside biological collections of Arctic fauna. Weyprecht's emphasis on continuous observations yielded over 700 days of meteorological records, later instrumental in advocating the first International Polar Year in 1882–1883. In May 1874, deeming further progress impossible, the expedition abandoned the Tegetthoff at 79°30'N, executing a 2,000-kilometer journey via sledge and open boat to reach Novaya Zemlya, where Norwegian seal hunters rescued them on 23 August 1874 after two months adrift.[16][19] The survivors returned to Vienna on 25 September 1874, greeted with imperial honors, though the venture yielded no territorial control over Franz Joseph Land, which remained unclaimed effectively until Soviet annexation in 1926.[15][20] In the broader scope of Austrian colonial policy, the expedition underscored the empire's exploratory ambitions amid naval revival post-1867 Compromise, paralleling contemporaneous voyages like the Novara circumnavigation, yet highlighted structural barriers: the landlocked orientation of Habsburg interests, absence of polar infrastructure, and prioritization of European affairs precluded sustained Arctic presence. Payer's published accounts and maps fueled scientific prestige but not imperial expansion, as rival powers like Britain and Russia dominated subsequent Arctic claims.[17][19]Participation in Global Imperial Conferences and Claims

Berlin Conference of 1884–1885

The Berlin Conference convened on November 15, 1884, at the initiative of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck to address escalating European rivalries over African territories, particularly following Belgian King Leopold II's claims in the Congo Basin.[21] Fourteen powers participated, including Austria-Hungary, which was represented by Foreign Minister Count Gustav Kálnoky.[22] The conference concluded on February 26, 1885, with the signing of the General Act, establishing rules for free navigation on the Congo and Niger rivers, the suppression of the slave trade, and the principle of effective occupation, whereby territorial claims required demonstrable administrative control rather than mere notification.[22] Austria-Hungary, lacking established African colonies or significant commercial interests on the continent, joined seven other participants—Russia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden-Norway, the Ottoman Empire, and the United States—that held no territorial stakes in Africa.[21] Kálnoky's delegation endorsed the General Act without advancing specific claims, aligning with Vienna's broader geopolitical priorities centered on the Balkans and Central Europe amid internal ethnic tensions and limited naval resources.[21] This participation underscored Austria-Hungary's status as a great power entitled to influence international norms on colonization, yet it yielded no direct colonial benefits, highlighting the empire's peripheral role in the Scramble for Africa.[23] The conference's outcomes formalized a framework that favored maritime powers with expeditionary capabilities, implicitly disadvantaging landlocked Austria-Hungary, which possessed only a modest Adriatic fleet ill-suited for distant African ventures.[21] By adhering to the effective occupation doctrine, Austria-Hungary committed to non-interference in African partitions unless pursuing verifiable claims, a stipulation that deterred speculative expansion absent substantial investment.[22] Thus, the Berlin Conference represented a diplomatic formality for the Dual Monarchy rather than a catalyst for imperial growth, foreshadowing its reliance on concessions in Asia over African colonization.Late Nineteenth-Century African and Asian Initiatives

Maputo Bay Settlement

In 1777, William Bolts, a Dutch-born merchant previously employed by the British East India Company, established a trading factory at Delagoa Bay (present-day Maputo Bay) under a charter from the Austrian Asiatic Company, granted by Empress Maria Theresa in Ostend on September 2, 1776.[11] Bolts negotiated land cessions and trade rights with local Tembe chiefs, constructing basic infrastructure including a small harbor and Fort St. Joseph, armed with two cannons, to serve as a hub for exporting ivory and facilitating commerce between southeastern Africa and India's Malabar Coast.[24] The outpost initially comprised around 155 personnel, predominantly Austrian and Italian subjects who arrived via Bolts' expeditions starting in 1778, and rapidly boosted ivory shipments, doubling regional output and depressing local prices through competitive European demand.[25] By 1779, the company ship Joseph und Theresia supported further fortification efforts, including the erection of St. Maria Fort, amid growing Portuguese protests over Habsburg encroachment on claimed territories in Portuguese East Africa.[26] Despite short-term economic viability—evidenced by Bolts' procurement of multiple vessels for intra-regional "country trade"—the settlement encountered logistical challenges, such as disease among settlers and supply disruptions, compounded by Bolts' controversial practices including alleged slave trading.[27] Emperor Joseph II revoked the company's privileges on October 20, 1780, citing mismanagement and diplomatic fallout, leading to abandonment by mid-1781; Portuguese naval forces then razed the installations, reasserting control without formal arbitration.[28] The episode highlighted Austria's limited capacity for sustained overseas ventures, reliant on private initiative rather than state naval power, and yielded no lasting territorial gains, though it temporarily integrated Delagoa Bay into Habsburg trade networks before dissolution.[11]North Borneo Claim

In late 1877, Baron Gustav von Overbeck, a German-born adventurer serving as the Austro-Hungarian consul in Hong Kong, secured a territorial concession from Sultan Abdul Momin of Brunei for the northern coastal regions of Borneo, encompassing present-day Sabah.[29] This grant, dated December 29, 1877, vested Overbeck with rights to govern, trade, and develop the area in exchange for an annual payment of $15,000 Mexican dollars.[30] Overbeck, leveraging his diplomatic position, styled himself as Maharaja of Sabah and sought imperial backing from Vienna to transform the concession into an Austro-Hungarian protectorate, but the dual monarchy's foreign ministry rebuffed the proposal amid internal debates over overseas expansion. On January 22, 1878, Overbeck extended his holdings by obtaining a similar concession from Sultan Jamalul Alam of Sulu for the Sabah region, including islands and coastal territories, for an annual cession money of $5,000.[31] The Sulu agreement appointed Overbeck as Dato Bendahara and further authorized suppression of piracy and establishment of settlements.[32] To finance development, Overbeck assembled an international syndicate, including financial support from Count Maximilian von Montgelas, secretary at the Austro-Hungarian embassy in London, though this did not translate to official state endorsement. Initial efforts involved dispatching agents to assert control, such as establishing a flag-raising at Kudat in 1878, but faced local resistance and logistical challenges without naval backing from the empire. Unable to secure Austro-Hungarian governmental commitment—due to fiscal constraints and Hungarian parliamentary opposition to diverting resources from European priorities—Overbeck transferred his rights in 1880 to British merchant Alfred Dent and associates. This culminated in the chartering of the British North Borneo Company on November 1, 1881, under a royal charter that formalized British influence over the territory.[33] The episode represented a fleeting private initiative with diplomatic ties to Austria-Hungary, rather than a sustained imperial claim, highlighting the monarchy's reluctance to engage in distant colonial administration without broad domestic consensus.[34]Rio de Oro Venture

In the aftermath of its defeat in the Spanish-American War of 1898, Spain sought to divest itself of peripheral colonial holdings to alleviate financial and administrative burdens, including the sparsely populated Rio de Oro region along the Atlantic coast of present-day Western Sahara.[35] Spanish diplomats initiated contact with the Austro-Hungarian Colonial Society (Ostafrikanische Gesellschaft Österreichs), proposing the sale of the territory as a trading port and potential naval base, which aligned with Austria-Hungary's intermittent interest in overseas expansion during the late 19th century.[36] Negotiations advanced informally through the Colonial Society and figures such as Austrian Commerce Minister Baron Josef de Paoli, who advocated for acquisition to secure commercial outlets and counterbalance the monarchy's continental focus.[37] Proponents argued that Rio de Oro's strategic location could facilitate trade in gum arabic, fish, and phosphates, with initial estimates suggesting a purchase price in the range of several million gulden, though exact terms remained provisional.[35] However, the venture encountered staunch opposition from Hungarian political leaders within the Dual Monarchy, who viewed colonial commitments as a pretext for bolstering the central government's military and administrative powers, potentially threatening Hungary's autonomist position established by the 1867 Ausgleich.[36] By 1900, Hungarian vetoes in the joint ministerial council effectively halted the deal, prioritizing internal stability over extraterritorial gains amid ongoing Ausgleich tensions.[37] Spain subsequently redirected overtures toward France, which incorporated Rio de Oro into its North African sphere by 1904, underscoring Austria-Hungary's structural limitations in pursuing independent colonial policy.[35] The episode highlighted the monarchy's reliance on private societies for exploratory ventures, yet revealed how domestic veto powers consistently undermined such initiatives, resulting in no territorial acquisition or sustained presence in the region.[36]Early Twentieth-Century Concessions

Tianjin Concession

The Austro-Hungarian concession in Tianjin was granted in December 1902 as partial compensation for the empire's participation in the Eight-Nation Alliance that suppressed the Boxer Rebellion (1900–1901), during which Austro-Hungarian forces contributed approximately 200 marines to the relief expedition for the besieged legations in Beijing.[38][39] The territory encompassed roughly 0.6 square kilometers (150 acres or 600,000 square meters) along the Hai River, adjacent to other foreign concessions but hampered by its upstream location, which restricted maritime access and commercial viability.[39] Administration fell under the Austro-Hungarian consul, with figures such as Carl Bernauer (1903–1912) and Hugo Schumpeter (1912–1917) overseeing operations; a municipal council established in 1908 included four Austro-Hungarian and four Chinese members, while policing relied on 70 Chinese auxiliaries supervised by Austro-Hungarian naval personnel.[39] The population reached about 40,000, predominantly Chinese, with around 10,000 residents expropriated by 1914 to clear land for development, though European settlement remained negligible.[39] Infrastructure efforts included the construction of a consulate between 1903 and 1906 at a cost of approximately 87,000 Mexican dollars and an iron swing bridge completed in 1906 for 500,000 kronen, largely funded by non-Austrian sources via the Hotung Construction Company founded in 1905.[39] Development stagnated after 1909 due to inadequate funding from Vienna, pre-existing Chinese settlements, salt deposits, and over 6,700 graves complicating land use, compounded by a major flood in 1911 that damaged nascent sewage and drainage systems.[39] Economic activities were minimal, with the concession generating little trade or investment relative to larger European holdings, reflecting Austria-Hungary's broader naval and fiscal constraints that prioritized European commitments over distant enclaves.[39] The concession effectively ended in 1917 when the Republic of China declared war on the Central Powers on August 14, revoking the lease and occupying the territory alongside the adjacent German concession; formal renunciation followed the empire's dissolution, with properties like the consulate sold in 1923 for 65,000 taels.[38][39] Despite initial ambitions for a "model colony," the venture yielded negligible long-term economic or strategic gains for Austria-Hungary, underscoring the impracticality of micro-concessions without sustained metropolitan support.[39]Structural Constraints on Expansion

Internal Political Divisions

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 created a dual monarchy in which foreign policy was conducted jointly, but common expenditures for military, naval, or colonial initiatives required approval from both the Austrian Reichsrat and Hungarian Parliament, mediated through annual Delegations. This institutional arrangement frequently stymied overseas ambitions, as Hungarian delegates, representing a partner wary of centralizing tendencies, vetoed proposals perceived to strengthen Vienna's influence or divert funds from land-based priorities. For example, in the 1870s, Hungarian opposition blocked revivals of the Ostend East India Company and limited naval expansions essential for colonial sustainment, prioritizing instead a minimal common army to avert repeats of the 1848 suppression of Hungarian revolt.[1][40] Hungarian political culture, shaped by post-1848 resentments, emphasized continental focus and resisted policies that might legitimize Habsburg universalism abroad while neglecting Magyarization efforts at home. Delegates like those aligned with Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza argued that colonial ventures would exacerbate budget strains without proportional benefits, effectively vetoing acquisitions such as potential African leaseholds discussed in the 1880s. This dynamic not only curtailed private initiatives, like William Bolts' earlier schemes, but also ensured that joint foreign ministry efforts, under figures like Count Gustav Kálnoky, prioritized Balkan containment over global competition.[1][40] Compounding the Austro-Hungarian axis were ethnic fractures among the empire's 52 million subjects by 1910, where German liberals, Czech autonomists, Polish federalists, and South Slav irredentists engaged in chronic parliamentary obstruction. The Czech National Social Party's boycott of the Reichsrat from 1897 onward, alongside Croatian demands for parity akin to Hungary's, fragmented consensus on any non-European policy, as governments grappled with suffrage reforms and language laws amid rising pan-Slavic agitation. These divisions channeled limited imperial energies toward "internal colonies" like Bosnia-Herzegovina, occupied in 1878 and annexed in 1908, rather than risking further instability through overseas commitments that could ignite domestic nationalist backlash.[41][42]Naval and Economic Realities

The Austro-Hungarian Navy's strategic orientation toward Adriatic coastal defense severely restricted its capacity for overseas colonial ventures. Established primarily to counter Italian naval threats and secure maritime access to the empire's primary ports in Trieste and Pola, the fleet prioritized short-range operations over long-distance power projection. By the late 19th century, naval reforms following the 1866 Battle of Lissa had modernized some vessels, but the overall force remained modest, with limited cruisers and no dedicated colonial transports.[43] Funding constraints inherent to the dual monarchy exacerbated these limitations. Naval appropriations required unanimous approval from both Austrian and Hungarian parliamentary delegations, resulting in chronic underfunding and delays; Hungary, contributing 36% of the budget, viewed expansions as disproportionately benefiting Austrian Adriatic interests and often vetoed ambitious programs. The 1911-1917 naval plan, which yielded only four Tegetthoff-class dreadnoughts alongside a handful of cruisers and destroyers, exemplified this parsimony, as the fleet's total tonnage paled against British or French counterparts capable of sustaining global squadrons. Without overseas coaling stations or allied basing rights, even routine expeditions like the 1857-1859 Novara circumnavigation strained logistics, underscoring the navy's unsuitability for colonial enforcement.[43][14] Economically, Austria-Hungary's agrarian-dominated structure and regional disparities hindered investment in colonial enterprises. While Bohemia and Austrian Poland experienced industrialization, the empire as a whole remained self-sufficient in staples like cereals, reducing urgency for tropical resource extraction. Merchant shipping lagged, with minimal tonnage relative to colonial powers, and capital flowed preferentially to European infrastructure over risky overseas concessions. High public debts from mid-century military reforms and uneven fiscal integration under the 1867 Ausgleich further diverted resources, rendering sustained colonial administration fiscally unviable.[44][43]Geopolitical Focus on Continental Europe

The Austro-Hungarian Empire's geopolitical orientation in the 19th and early 20th centuries was firmly anchored in continental Europe, driven by immediate security imperatives that overshadowed any peripheral overseas ambitions. Surrounded by rival powers—Russia to the east, the German Empire to the north, and an increasingly unified Italy to the south—the Dual Monarchy prioritized containment of Slavic nationalism in the Balkans and preservation of its multi-ethnic territorial integrity over distant colonial ventures. The Congress of Berlin in 1878, which formalized Austria-Hungary's occupation and administration of Bosnia-Herzegovina on July 28, granted Vienna a strategic foothold to counter Russian pan-Slavic influence and Serbian irredentism, redirecting diplomatic and military resources toward Southeastern Europe rather than global expansion.[45] This move, involving the deployment of over 150,000 troops by 1879, underscored a doctrine of forward defense on land borders, where threats to the empire's cohesion were most acute.[46] Alliance systems further entrenched this European-centric focus, as Austria-Hungary sought multilateral balances to mitigate isolation. The Dual Alliance with Germany, signed on October 7, 1879, committed mutual defense against Russian aggression, reflecting Vienna's vulnerability exposed by the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the need to anchor Habsburg influence in Central Europe amid the Eastern Question.[41] Extended into the Triple Alliance with Italy in 1882, this framework—despite Italy's Adriatic ambitions—prioritized deterrence of French revanchism and Russian southward pushes, consuming diplomatic bandwidth in European congresses and chancelleries. Such entanglements, including the Dreikaiserbund renewals until 1887, embodied Metternichian principles of equilibrium, where overseas distractions risked weakening the empire's position in Vienna's core sphere of competition.[47] Limited maritime projection capabilities reinforced terrestrial priorities, as the Austro-Hungarian Navy, confined primarily to the Adriatic with a fleet peaking at around 20 modern warships by 1914, lacked the blue-water assets for sustained extracon tinental operations. Geopolitical calculus thus favored leveraging continental alliances and Balkan buffer zones—evident in the 1908 annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which provoked but contained crises with Russia—over speculative colonial risks that could strain alliances or invite naval overextension.[1] This inward-looking realism, informed by defeats like Königgrätz in 1866, positioned Europe not as a mere theater but as the existential arena, where Habsburg survival hinged on mastering regional power dynamics rather than emulating maritime empires.[48]Assessments and Legacy

Empirical Outcomes of Attempts

Austrian colonial ventures yielded predominantly negative empirical outcomes, characterized by financial losses, high human costs, and territorial impermanence across multiple attempts. The Ostend East India Company (1722–1731), the most commercially viable Habsburg initiative, generated substantial short-term profits from trade in Bengal textiles, Mocha coffee, and Chinese goods, with shareholders realizing an estimated net return of approximately 150% before its forced dissolution under British and Dutch diplomatic pressure.[49] However, the company's suppression prevented sustained economic integration, resulting in no long-term imperial revenue stream and the forfeiture of two Indian settlements established during its operations.[50] Subsequent efforts, such as the Nicobar Islands settlements in the late 18th century, incurred severe human tolls without viable returns. The 1778 expedition under Gottfried Stahl involved around 100 colonists, but disease outbreaks, particularly malaria, led to the leader's death in 1783 and the abandonment of the colony by 1785, with the majority of settlers perishing from illness and privation.[51] Later Habsburg-associated attempts in the 1880s similarly collapsed due to endemic tropical diseases, yielding zero economic output and reinforcing the impracticality of plantation-based colonization in such environments.[14] Claims in regions like North Borneo (1878–1880) and Rio de Oro in West Africa produced negligible results, with the Borneo venture quickly ceded to British interests after brief diplomatic maneuvering, entailing administrative costs but no resource extraction or settlement establishment.[52] The Austro-Hungarian concession in Tianjin (1901–1917), granted post-Boxer Rebellion, spanned a mere 0.5 square kilometers and generated insignificant trade volumes, functioning more as a symbolic diplomatic outpost than a profitable enclave before its wartime liquidation.[53] Exploratory expeditions, including the SMS Novara's global circumnavigation (1857–1859), incurred costs estimated at 175,000 florins for scientific gains but no colonial footholds, underscoring a pattern of expenditure without commensurate imperial expansion.[54] In aggregate, these initiatives resulted in net financial drains on Habsburg resources, with human casualties concentrated in disease-prone outposts and diplomatic reversals preventing any enduring territorial or economic legacies, as evidenced by the absence of viable overseas assets by the empire's dissolution in 1918.[41]Comparative Analysis with Other Powers

Unlike maritime empires such as Britain and France, which established vast overseas territories through naval supremacy and mercantile interests, Austria-Hungary's colonial efforts remained marginal due to its continental orientation and structural limitations. By 1914, Britain's empire encompassed roughly 33.7 million square kilometers across every inhabited continent, fueled by the Royal Navy's unchallenged global reach that enabled sustained projection of power from the 16th century onward. France, similarly, controlled about 10.6 million square kilometers, including Algeria seized in 1830 and expansions in West Africa and Indochina, supported by a fleet that ranked second to Britain's in tonnage and battleships during the late 19th century. In contrast, Austria-Hungary held no significant overseas possessions, with its few ventures—like the short-lived Rio de Oro claim in 1883–1885 and the Tianjin concession from 1901—yielding negligible territorial or economic gains.[55] The Austro-Hungarian navy's inadequacy for blue-water operations further underscored this disparity; by 1914, it maintained only 20,000 personnel and four dreadnoughts, primarily configured for Adriatic defense against Italy rather than oceanic campaigns, ranking it below Britain (29 dreadnoughts), Germany (17), and even France in overall capability for distant expeditions. This contrasted sharply with the Netherlands, whose earlier Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, secured profitable enclaves like Indonesia through armed trading fleets, generating revenues that peaked at 40% of Dutch GDP in the mid-17th century. Austria's analogous Ostend Company, chartered in 1722, was suppressed by Dutch-British pressure after just nine years, reflecting Habsburg vulnerability to rival coalitions without comparable naval deterrence.[43] Comparisons with Germany highlight shared initial restraint but divergent outcomes. Otto von Bismarck, like Austrian statesmen, prioritized European Realpolitik over colonial distractions, dismissing overseas acquisitions as costly entanglements that could provoke Britain and France; Germany's first formal colonies emerged only in 1884, totaling about 2.55 million square kilometers in Africa and the Pacific by 1914, often unprofitable and administered via chartered companies to minimize state burden. Yet, under Wilhelm II's Weltpolitik from 1897, Germany expanded naval construction—reaching 40 battleships by 1914—enabling bolder claims, whereas Austria-Hungary's dualist structure post-1867 Compromise engendered Hungarian vetoes against military centralization, capping naval budgets at under 3% of the joint budget versus Germany's rising 20% share. Belgium's outlier success, with King Leopold II personally claiming the 2.3 million-square-kilometer Congo Free State in 1885 through diplomatic maneuvering at the Berlin Conference (where Austria participated peripherally without gains), stemmed from monarchical autonomy absent in the multi-ethnic Habsburg realm, where Franz Joseph I emphasized Balkan stabilization over extraterritorial risks.[56]| Power | Approx. Colonial Land Area (1914, million km²) | Key Enablers | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Britain | 33.7 | Naval dominance, trading companies | Global commerce, settlement |

| France | 10.6 | Centralized state, army deployments | Africa, Asia assimilation |

| Germany | 2.55 | Late unification, chartered firms | Prestige, resource extraction |

| Belgium | 2.3 (Congo) | Personal royal initiative | Exploitation via concessions |

| Austria-Hungary | ~0 | Limited navy, internal divisions | Continental security |