Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Epistle to the Colossians

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

|

The Epistle to the Colossians[a] is a Pauline epistle and the twelfth book of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It was written, according to the text, by Paul the Apostle and Timothy, and addressed to the church in Colossae, a small Phrygian city near Laodicea and approximately 100 miles (160 km) from Ephesus in Asia Minor (now in Turkey).[4]

Many scholars question Paul's authorship and attribute the letter to an early follower instead, but others still defend it as authentic.[4] If Paul was the author, he probably used an amanuensis, or secretary, in writing the letter (Col 4:18),[5] possibly Timothy.[6]

The original text was written in Koine Greek.

Composition

[edit]During the first generation after Jesus, Paul's epistles to various churches helped establish early Christian theology. According to Bruce Metzger, it was written in the 60s while Paul was in prison.[7] Other scholars have ascribed the epistle to an early follower of Paul, writing as Paul due to its similarity to the Epistle to the Galatians, another contested work. The epistle's description of Christ as pre-eminent over creation marks it, for some scholars, as representing an advanced christology not present during Paul's lifetime.[8] Defenders of Pauline authorship, however, cite the work's similarities to the letter to Philemon, which is broadly accepted as authentic.[4]

Authorship

[edit]The letter's authors claim to be Paul and Timothy, but authorship began to be authoritatively questioned during the 19th century.[9] Pauline authorship was held to by many of the early church's prominent theologians, such as Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Origen of Alexandria and Eusebius.[10]

However, as with several epistles attributed to Paul, critical scholarship disputes this claim.[11] A 2011 survey of 109 scholars at the British New Testament Conference found 56 in favor of authenticity, while 17 rejected Pauline authorship and 36 were uncertain.[12] One ground is that the epistle's language doesn't seem to match Paul's, with 48 words appearing in Colossians that are found nowhere else in his writings and 33 of which occur nowhere else in the New Testament.[13] A second ground is that the epistle features a strong use of liturgical-hymnic style which appears nowhere else in Paul's work to the same extent.[14] A third is that the epistle's themes related to Christ, eschatology and the church seem to have no parallel in Paul's undisputed works.[15]

Advocates of Pauline authorship defend the differences that there are between elements in this letter and those commonly considered the genuine work of Paul (e.g. 1 Thessalonians). It is argued that these differences can come by human variability, such as by growth in theological knowledge over time, different occasion for writing, as well as use of different secretaries (or amanuenses) in composition.[16][5] As it is usually pointed out by the same authors who note the differences in language and style, the number of words foreign to the New Testament and Paul is no greater in Colossians than in the undisputed Pauline letters (Galatians, of similar length, has 35 hapax legomena). In regard to the style, as Norman Perrin, who argues for pseudonymity, notes, "The letter does employ a great deal of traditional material and it can be argued that this accounts for the non-Pauline language and style. If this is the case, the non-Pauline language and style are not indications of pseudonymity."[17] Not only that, but it has been noted that Colossians has indisputably Pauline stylistic characteristics, found nowhere else in the New Testament.[17][18] Advocates of Pauline authorship also argue that the differences between Colossians and the rest of the New Testament are not as great as they are purported to be.[19]

As theologian Stephen D. Morrison points out in context, "Biblical scholars are divided over the authorship of Ephesians and Colossians."[20] He provides as an example the reflection of theologian Karl Barth on the question. While acknowledging the validity of many questions regarding Pauline authorship, Barth was inclined to defend it. Nevertheless, he concluded that it didn't much matter one way or the other to him. It was more important to focus on "Quid scriptum est" (What is written) than "Quis scripseris" (Who wrote it). "It is enough to know that someone, at any rate, wrote Ephesians (why not Paul?), 30 to 60 years after Christ’s death (hardly any later than that, since it is attested by Ignatius, Polycarp, and Justin), someone who understood Paul well and developed the apostle’s ideas with conspicuous loyalty as well as originality.”[20]

Date

[edit]If the text was written by Paul, it could have been written at Rome during his first imprisonment.[21][22] Paul would likely have composed it at roughly the same time that he wrote Philemon and Ephesians, as all three letters were sent with Tychicus[23] and Onesimus. A date of 62 AD assumes that the imprisonment Paul speaks of is his Roman imprisonment that followed his voyage to Rome.[24][22]

Other scholars have suggested that it was written from Caesarea or Ephesus.[25]

If the letter is not considered to be an authentic part of the Pauline corpus, then it might be dated during the late 1st century, possibly as late as AD 90.[26]

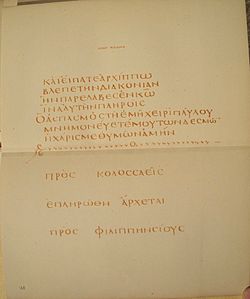

Surviving manuscripts

[edit]The original manuscript is lost, as are many early copies. The text of surviving copies varies. The oldest manuscripts transcribing some or all of this letter include:

- Papyrus 46 (c. AD 200)

- Codex Vaticanus (325–350)

- Codex Sinaiticus (330–360)

- Codex Alexandrinus (400–440)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (c. 450)

- Codex Freerianus (c. 450)

- Codex Claromontanus (c. 550; in Greek and Latin)

- Codex Coislinianus (c. 550)

Content

[edit]

Colossae is in the same region as the seven churches of the Book of Revelation.[27] In Colossians there is mention of local brethren in Colossae, Laodicea, and Hierapolis. Colossae was approximately 12 miles (19 km) from Laodicea and 14 miles (23 km) from Hierapolis.

References to "the elements" and the only mention of the word "philosophy" in the New Testament have led scholar Norman DeWitt to conclude that early Christians at Colossae must have been under the influence of Epicurean philosophy, which taught atomism.[28] The Epistle to the Colossians proclaimed Christ to be the supreme power over the entire universe, and urged Christians to lead godly lives. The letter consists of two parts: first a doctrinal section, then a second regarding conduct. Those who believe that the motivation of the letter was a growing heresy in the church see both sections of the letter as opposing false teachers who have been spreading error in the congregation.[further explanation needed][8] Others[like whom?] see both sections of the letter as primarily encouragement and edification for a developing church.[29]

Outline

[edit]I. Introduction (1:1–14)

- A. Greetings (1:1–2)

- B. Thanksgiving (1:3–8)

- C. Prayer (1:9–14)

II. The Supremacy of Christ (1:15–23)

III. Paul's Labor for the Church (1:24–2:7)

- A. A Ministry for the Sake of the Church (1:24–2:7)

- B. A Concern for the Spiritual Welfare of His Readers (2:1–7)

IV. Freedom from Human Regulations through Life with Christ (2:8–23)

- A. Warning to Guard against the False Teachers (2:8–15)

- B. Pleas to Reject the False Teachers (2:16–19)

- C. An Analysis of the Heresy (2:20–23)

V. Rules for Holy Living (3:1–4:6)

- A. The Old Self and the New Self (3:1–17)

- B. Rules for Christian Households (3:18–4:1)

- C. Further Instructions (4:2–6)

VI. Final Greetings (4:7–18) [30]

Doctrinal sections

[edit]The doctrinal part of the letter is found in the first two chapters. The main theme is developed in chapter 2, with a warning against being drawn away from him in whom dwelt all the fullness of the deity,[31] and who was the head of all spiritual powers. Colossians 2:8–15 offers firstly a "general warning" against accepting a purely human philosophy, and then Colossians 2:16–23 a "more specific warning against false teachers".[32]

In these doctrinal sections, the letter proclaims that Christ is supreme over all that has been created. All things were created through him and for him, and the universe is sustained by him. God had chosen for his complete being to dwell in Christ. The "cosmic powers" revered by the false teachers had been "discarded" and "led captive" at Christ's death. Christ is the master of all angelic forces and the head of the church. Christ is the only mediator between God and humanity, the unique agent of cosmic reconciliation. It is the Father in Colossians who is said to have delivered us from the domain of darkness and transferred us to the kingdom of His beloved Son.[33] The Son is the agent of reconciliation and salvation not merely of the church, but in some sense redeems the rest of creation as well ("all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven").[34][tone]

Conduct

[edit]The practical part of the Epistle, in chapters 3 and 4, addresses various duties which flow naturally from the doctrinal section. The community members are exhorted to "set their minds" on the things that are above, not on earthly things,[35] to mortify every evil principle of their nature, and to put on "a new self".[36] Many special duties of the Christian life are also insisted upon as the fitting evidence of the Christian character.

Colossians 3:22–24 instructs slaves to obey their masters and serve them sincerely, because they will receive an "inheritance"[37] from God. Colossians 4:1 instructs masters (slave owners) to "provide your slaves with what is right and fair",[38] because God is in turn their master.

The letter ends with a customary prayer,[39] instruction, and greetings.[8]

The prison epistles

[edit]Colossians is often categorized as one of the "prison epistles", along with Ephesians, Philippians, and Philemon. Colossians has some close parallels with the letter to Philemon: names of some of the same people (e.g., Timothy, Aristarchus, Archippus, Mark, Epaphras, Luke, Onesimus, and Demas) appear in both epistles, and both are claimed to be written by Paul.[40]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1. Archived from the original on October 5, 2023.

- ^ ESV Pew Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. 2018. p. 983. ISBN 978-1-4335-6343-0. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021.

- ^ "Bible Book Abbreviations". Logos Bible Software. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c Cross, F.L., ed. (2005), "Colossians, Epistle to the", The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Richards, E. Randolph (2004), Paul and First-Century Letter Writing: Secretaries, Composition and Collection, Downers Grove, IL; Leicester, England: InterVarsity Press; Apollos.

- ^ Dunn, James D.G. (1996), The Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon: A Commentary on the Greek Text, New International Greek Testament Commentary, Grand Rapids, MI; Carlisle: William B. Eerdmans; Paternoster Press, p. 38.

- ^ May, Herbert G. and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.

- ^ a b c Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "Colossians" pp. 337–38

- ^ “The earliest evidence for Pauline authorship, aside from the letter itself ... is from the mid to late 2d cent. (Marcionite canon; Irenaeus, Adv. Haer. 3.14.1; Muratorian canon). This traditional view stood [usually] unquestioned until 1838, when E. T. Mayerhoff denied the authenticity of this letter, claiming that it was full of non-Pauline ideas and dependent on the letter to the Ephesians. Thereafter others have found additional arguments against Pauline authorship." New Jerome Biblical Commentary

- ^ For a defense of Pauline authorship for Colossians see: Authenticity of Colossians

- ^ "The cumulative weight of the many differences from the undisputed Pauline epistles has persuaded most modern [also some XVI century] scholars that Paul did not write Colossians ... Those who defend the authenticity of the letter include Martin, Caird, Houlden, Cannon and Moule. Some... describe the letter as Pauline but say that it was heavily interpolated or edited. Schweizer suggests that Col was jointly written by Paul and Timothy. The position taken here is that Col is Deutero-Pauline; it was composed after Paul’s lifetime, between AD 70 (Gnilka) and AD 80 (Lohse) by someone who knew the Pauline tradition. Lohse regards Col as the product of a Pauline school tradition, probably located in Ephesus." [TNJBC 1990 p. 877]

- ^ Foster, Paul 2012, Who Wrote 2 Thessalonians: A Fresh Look at an Old Problem, Journal for the Study of the New Testament , vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 150-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064X12462654

- ^ Koester, Helmut. History and Literature of Early Christianity, Introduction to the New Testament Vol 2. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co, 1982, 1987.

- ^ Kümmel, Werner Georg. Introduction To The New Testament, Revised English Edition, Translated by Howard Kee. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1973, 1975

- ^ “The christology of Col is built on the traditional hymn in 1:15–20, according to which Christ is the image of the invisible God... and other christological statements that have no parallel in the undisputed Pauline writings are added: that Christ is the mystery of God... that believers have been raised with Christ ... that Christ forgives sins... that Christ is victorious over the principalities and powers..." Compared to undisputed Pauline epistles, in which Paul looks forward to an imminent Second Coming, Colossians presents a completed eschatology, in which baptism relates to the past (a completed salvation) rather than to the future: “...whereas Paul expected the parousia in the near future (I Thes 4:15; 5:23; I Cor 7:26)... The congregation has already been raised from the dead with Christ ... whereas in the undisputed letters resurrection is a future expectation... The difference in eschatological orientation between Col and the undisputed letters results in a different theology of baptism... Whereas in Rom 6:1–4 baptism looks forward to the future, in Col baptism looks back to a completed salvation. In baptism believers have not only died with Christ but also been raised with him.” The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, Edited by Raymond E. Brown, S.S., Union Theological Seminary, New York; NY, Maurya P. Horgan (Colossians); Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm. (emeritus) The Divinity School, Duke University, Durham, NC, with a foreword by His Eminence Carlo Maria Cardinal Martini, S.J.; Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1990 1990 p. 876

- ^ Richard R. Melick, vol. 32, Philippians, Colossians, Philemon, electronic ed., Logos Library System; The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2001, c. 1991), 166

- ^ a b Perrin, Norman. The New Testament: An Introduction: Proclamation and Parenesis, Myth and History. Harcourt College Pub., 1974, p. 121

- ^ Kümmel, W.G. Introduction to the New Testament. 1966, p. 241: 'Pleonastic "kai" after "dia touto" (Col 1:9) is found in the NT only in Paul (1 Thess. 2:13; 3:5; Rom. 13:6)..."hoi hagioi autou" Col 1:25=1 Thess. 3:13, 2 Thess. 1:10, "charixesthai"=to forgive (Col 2:13, 3:13) only in 2 Cor 2:7, 10, 12:13' etc.

- ^ P. O’Brien, Colossians, Philemon, WBC (Waco, Tex.: Word, 1982), xiv

- ^ a b Morrison, Stephen D. (June 8, 2016). "Karl Barth on the Authorship of Ephesians and Colossians". Stephen D. Morrison.

- ^ Acts 28:16, 28:30

- ^ a b "Introduction to the Book of Colossians". ESV Study Bible. Crossway. 2008. ISBN 978-1433502415.

- ^ Ephesians 6:21

- ^ Acts 27-28

- ^ Wright, N. T., Colossians and Philemon, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1986), pp. 34–39.

- ^ Mack, Burton L. (1996), Who Wrote the New Testament? San Francisco: Harper Collins.

- ^ Revelation 1-2

- ^ St Paul and Epicurus. University of Minnesota Press. 1954.

- ^ Hooker, Morna D. (1973). "Were There False Teachers in Colossae?". Christ and Spirit in the New Testament: Studies in Honour of Charles Francis Digby Moule: 315–331.

- ^ NIV Bible (Large Print ed.). (2007). London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

- ^ Colossians 2:9

- ^ Alford, H., Greek Testament Critical Exegetical Commentary - Alford: Colossians 2, accessed 19 May 2021

- ^ Colossians 1:12–13

- ^ Colossians 1:20

- ^ Colossians 3:4: Christian Standard Bible (CSB), 2017

- ^ Colossians 3:10: CSB

- ^ New International Version

- ^ New International Version

- ^ Colossians 4:3–4

- ^ [Survey of the New Testament: Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians and Philemon]

Bibliography

[edit]- R. McL. Wilson, Colossians and Philemon (International Critical Commentary; London: T&T Clark, 2005)

- Jerry Sumney, Colossians (New Testament Library; Louisville; Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 2008)

- TIB = The Interpreter's Bible, The Holy Scriptures in the King James and Revised Standard versions with general articles and introduction, exegesis, [and] exposition for each book of the Bible in twelve volumes, George Arthur Buttrick, Commentary Editor, Walter Russell Bowie, Associate Editor of Exposition, Paul Scherer, Associate Editor of Exposition, John Knox Associate Editor of New Testament Introduction and Exegesis, Samuel Terrien, Associate Editor of Old Testament Introduction and Exegesis, Nolan B. Harmon Editor, Abingdon Press, copyright 1955 by Pierce and Washabaugh, set up printed, and bound by the Parthenon Press, at Nashville, Tennessee, Volume XI, Philippians, Colossians [Introduction and Exegesis by Francis W. Beare, Exposition by G. Preston MacLeod], Thessalonians, Pastoral Epistles [The First and Second Epistles to Timothy, and the Epistle to Titus], Philemon, Hebrews

- TNJBC = The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, Edited by Raymond E. Brown, S.S., Union Theological Seminary, New York; NY, Maurya P. Horgan [Colossians]; Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm. (emeritus) The Divinity School, Duke University, Durham, NC, with a foreword by His Eminence Carlo Maria Cardinal Martini, S.J.; Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1990

External links

[edit]Online translations of the Epistle to the Colossians:

- Collection of translations and commentary on Colossians

Colossians public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions including Greek Translation

Colossians public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions including Greek Translation- English Translation with Parallel Latin Vulgate

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Multiple bible versions at Bible Gateway (NKJV, NIV, NRSV etc.)