Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Devon

View on Wikipedia

Devon (/ˈdɛvən/ DEV-ən; historically also known as Devonshire /-ʃɪər, -ʃər/ -sheer, -shər) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west. The city of Plymouth is the largest settlement, and the city of Exeter is the county town.

Key Information

The county has an area of 2,590 sq mi (6,700 km2) and a population of 1,194,166. The largest settlements after Plymouth (264,695) are the city of Exeter (130,709) and the seaside resorts of Torquay and Paignton, which have a combined population of 115,410.[6] They all are located along the south coast, which is the most populous part of the county; Barnstaple (31,275) and Tiverton (22,291) are the largest towns in the north and centre respectively. For local government purposes Devon comprises a non-metropolitan county, with eight districts, and the unitary authority areas of Plymouth and Torbay. Devon County Council and Torbay Council collaborate through a combined county authority.

Devon has a varied geography. It contains Dartmoor and part of Exmoor, two upland moors which are the source of most of the county's rivers, including the Taw, Dart, and Exe. The longest river in the county is the Tamar, which forms most of the border with Cornwall and rises in Devon's northwest hills. The southeast coast is part of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site, and characterised by tall cliffs which reveal the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous geology of the region. The county gives its name to the Devonian geologic period, which includes the slates and sandstones of the north coast. Dartmoor and Exmoor have been designated national parks, and the county also contains, in whole or in part, five national landscapes.

In the Iron Age, Roman and the Sub-Roman periods, the county was the home of the Dumnonii Celtic Britons. The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain resulted in the partial assimilation of Dumnonia into the kingdom of Wessex in the eighth and ninth centuries, and the western boundary with Cornwall was set at the Tamar by king Æthelstan in 936.

Toponymy

[edit]The name Devon derives from the name of the Brythons who inhabited the southwestern peninsula of Britain at the time of the Roman conquest of Britain known as the Dumnonii, thought to mean 'deep valley dwellers' from Proto-Celtic *dubnos 'deep'. In the Brittonic languages, Devon is known as Welsh: Dyfnaint, Breton: Devnent and Cornish: Dewnens, each meaning 'deep valleys'. (For an account of Celtic Dumnonia, see the separate article.) Among the most common Devon placenames is -combe which derives from Brittonic cwm meaning 'valley' usually prefixed by the name of the possessor.[citation needed]

William Camden, in his 1607 edition of Britannia, described Devon as being one part of an older, wider country that once included Cornwall:

THAT region which, according to the Geographers, is the first of all Britaine, and, growing straiter still and narrower, shooteth out farthest into the West, [...] was in antient time inhabited by those Britans whom Solinus called Dumnonii, Ptolomee Damnonii [...] For their habitation all over this Countrey is somewhat low and in valleys, which manner of dwelling is called in the British tongue Dan-munith, in which sense also the Province next adjoyning in like respect is at this day named by the Britans Duffneit, that is to say, Low valleys. [...] But the Country of this nation is at this day divided into two parts, knowen by later names of Cornwall and Denshire, [...]

— William Camden, Britannia.[7]

The term Devon is normally used for everyday purposes (e.g., "Devon County Council"), but Devonshire has continued to be used in the names of the "Devonshire and Dorset Regiment" (until 2007) and "The Devonshire Association". One erroneous theory is that the shire suffix is due to a mistake in the making of the original letters patent for the Duke of Devonshire, resident in Derbyshire. There are references to both Defnas and Defenasċīre in Anglo-Saxon texts from before 1000 CE (the former is a name for the "people of Devon" and the latter would mean 'Shire of the Devonians'),[8] which translates to modern English as Devonshire. The term Devonshire may have originated around the 8th century, when it changed from Dumnonia (Latin) to Defenasċīr.[9]

History

[edit]Human occupation

[edit]

Kents Cavern in Torquay had produced human remains from 30 to 40,000 years ago. Dartmoor is thought to have been occupied by Mesolithic hunter-gatherer peoples from about 6000 BC. The Romans held the area under military occupation for around 350 years. Later, the area began to experience Saxon incursions from the east around 600 AD, firstly as small bands of settlers along the coasts of Lyme Bay and southern estuaries and later as more organised bands pushing in from the east. Devon became a frontier between Brittonic and Anglo-Saxon Wessex, and it was largely absorbed into Wessex by the mid ninth century.

A genetic study carried out by the University of Oxford and University College London discovered separate genetic groups in Cornwall and Devon. Not only were there differences on either side of the River Tamar—-with a division almost exactly following the modern county boundary,[10] but also between Devon and the rest of Southern England. Devon's population also exhibited similarities with modern northern France, including Brittany. This suggests the Anglo-Saxon migration into Devon was limited, rather than a mass movement of people.[11][12]

The border with Cornwall was set by King Æthelstan on the east bank of the River Tamar in 936 AD. Danish raids also occurred sporadically along many coastal parts of Devon between around 800AD and just before the time of the Norman conquest, including the silver mint at Hlidaforda Lydford in 997 and Taintona (a settlement on the Teign estuary) in 1001.[13]

Devon was the home of a number of anticlerical movements in the Later Middle Ages. For example, the Order of Brothelyngham—a fake monastic order of 1348 — regularly rode through Exeter, kidnapping both religious men and laymen, and extorting money from them as ransom.[14]

Devon has also featured in most of the civil conflicts in England since the Norman conquest, including the Wars of the Roses, Perkin Warbeck's rising in 1497, the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, and the English Civil War. The arrival of William of Orange to launch the Glorious Revolution of 1688 took place at Brixham.[15]

Devon has produced tin, copper and other metals from ancient times. Devon's tin miners enjoyed a substantial degree of independence through Devon's Stannary Convocation, which dates back to the 12th century. The last recorded sitting was in 1748.[16]

Geography and geology

[edit]

Devon straddles a peninsula and so, uniquely among English counties, has two separate coastlines: on the Bristol Channel and Celtic Sea in the north, and on the English Channel in the south.[17] The South West Coast Path runs along the entire length of both, around 65% of which is named as Heritage Coast. Before the changes to English counties in 1974, Devon was the third largest county by area and the largest of the counties not divided into county-like divisions (only Yorkshire and Lincolnshire were larger and both were sub-divided into ridings or parts, respectively).[18] Since 1974 the county is ranked fourth by area (due to the creation of Cumbria) amongst ceremonial counties and is the third largest non-metropolitan county. The island of Lundy and the reef of Eddystone are also in Devon. The county has more mileage of road than any other county in England.

Inland, the Dartmoor National Park lies wholly in Devon, and the Exmoor National Park lies in both Devon and Somerset. Apart from these areas of high moorland the county has attractive rolling rural scenery and villages with thatched cob cottages. All these features make Devon a popular holiday destination.

In South Devon the landscape consists of rolling hills dotted with small towns, such as Dartmouth, Ivybridge, Kingsbridge, Salcombe, and Totnes. The towns of Torquay and Paignton are the principal seaside resorts on the south coast. East Devon has the first seaside resort to be developed in the county, Exmouth and the more upmarket Georgian town of Sidmouth, headquarters of the East Devon District Council. Exmouth marks the western end of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. Another notable feature is the coastal railway line between Newton Abbot and the Exe Estuary: the red sandstone cliffs and sea views are very dramatic and in the resorts railway line and beaches are very near.

North Devon is very rural with few major towns except Barnstaple, Great Torrington, Bideford and Ilfracombe. Devon's Exmoor coast has the highest cliffs in southern Britain, culminating in the Great Hangman, a 318 m (1,043 ft) "hog's-back" hill with a 250 m (820 ft) cliff-face, located near Combe Martin Bay.[19] Its sister cliff is the 218 m (715 ft) Little Hangman, which marks the western edge of coastal Exmoor. One of the features of the North Devon coast is that Bideford Bay and the Hartland Point peninsula are both west-facing, Atlantic facing coastlines; so that a combination of an off-shore (east) wind and an Atlantic swell produce excellent surfing conditions. The beaches of Bideford Bay (Woolacombe, Saunton, Westward Ho! and Croyde), along with parts of North Cornwall and South Wales, are the main centres of surfing in Britain.

Geology

[edit]

A geological dividing line cuts across Devon roughly along the line of the Bristol to Exeter line and the M5 motorway east of Tiverton and Exeter. It is a part of the Tees–Exe line broadly dividing Britain into a southeastern lowland zone typified by gently dipping sedimentary rocks and a northwestern upland zone typified by igneous rocks and folded sedimentary and metamorphic rocks.

The principal geological components of Devon are i) the Devonian strata of north Devon and south west Devon (and extending into Cornwall); ii) the Culm Measures (north western Devon also extending into north Cornwall); and iii) the granite intrusion of Dartmoor in central Devon, part of the Cornubian batholith forming the 'spine' of the southwestern peninsula. There are blocks of Silurian and Ordovician rocks within Devonian strata on the south Devon coast but otherwise no pre-Devonian rocks on the Devon mainland. The metamorphic rocks of Eddystone are of presumed Precambrian age.[20]

The oldest rocks which can be dated are those of the Devonian period which are approximately 395–359 million years old. Sandstones and shales were deposited in North and South Devon beneath tropical seas. In shallower waters, limestone beds were laid down in the area now near Torquay and Plymouth.[21] This geological period was named after Devon by Roderick Murchison and Adam Sedgwick in the 1840s and is the only British county whose name is used worldwide as the basis for a geological time period.[22]

Devon's second major rock system[23] is the Culm Measures, a geological formation of the Carboniferous period that occurs principally in Devon and Cornwall. The measures are so called either from the occasional presence of a soft, sooty coal, which is known in Devon as culm, or from the contortions commonly found in the beds.[24] This formation stretches from Bideford to Bude in Cornwall, and contributes to a gentler, greener, more rounded landscape. It is also found on the western, north and eastern borders of Dartmoor.

The sedimentary rocks in more eastern parts of the county include Permian and Triassic sandstones (giving rise to east Devon's well known fertile red soils); Bunter pebble beds around Budleigh Salterton and Woodbury Common and Jurassic rocks in the easternmost parts of Devon. Smaller outcrops of younger rocks also exist, such as Cretaceous chalk cliffs at Beer Head and gravels on Haldon, plus Eocene and Oligocene ball clay and lignite deposits in the Bovey Basin, formed around 50 million years ago under tropical forest conditions.

Climate

[edit]Devon generally has a cool oceanic climate, heavily influenced by the North Atlantic Drift. In winter, snow is relatively uncommon away from high land, although there are few exceptions. The county has mild summers with occasional warm spells and cool rainy periods. Winters are generally cool and the county often experiences some of the mildest winters in the world for its high latitude, with average daily maximum temperatures in January at 8 °C (46 °F). Rainfall varies significantly across the county, ranging from over 2,000 mm (79 in) on parts of Dartmoor, to around 750 mm (30 in) in the rain shadow along the coast in southeastern Devon and around Exeter. Sunshine amounts also vary widely: the moors are generally cloudy, with the uplands near Princetown receiving less than 1,400 hours of sunshine annually, but the SE coast around Brixham and Berry Head receives more than 1,800 hours annually and is one of the sunniest areas of the UK. With westerly or south-westerly winds and high pressure the area around Torbay and Teignmouth will often be warm, with long sunny spells due to shelter by high ground (Foehn wind).

| Climate data for Devon | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

8 (46) |

10 (50) |

13 (55) |

16 (61) |

19 (66) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

19 (66) |

15 (59) |

12 (54) |

9 (48) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4 (39) |

3 (37) |

5 (41) |

6 (43) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

13 (55) |

12 (54) |

9 (48) |

7 (45) |

5 (41) |

8 (46) |

| [citation needed] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]

The variety of habitats means that there is a wide range of wildlife (see Dartmoor wildlife, for example). A popular challenge among birders is to find over 100 species in the county in a day.[citation needed] The county's wildlife is protected by several wildlife charities such as the Devon Wildlife Trust, which looks after 40 nature reserves. The Devon Bird Watching and Preservation Society (founded in 1928 and known since 2005 as "Devon Birds") is a county bird society dedicated to the study and conservation of wild birds.[25] The RSPB has reserves in the county, and Natural England is responsible for over 200 Devon Sites of Special Scientific Interest and National Nature Reserves,[26] such as Slapton Ley. The Devon Bat Group was founded in 1984 to help conserve bats. Wildlife found in this area extend to a plethora of different kinds of insects, butterflies and moths; an interesting butterfly to take look at is the chequered skipper.

Devon is a national hotspot for several species that are uncommon in Britain, including the cirl bunting; greater horseshoe bat; Bechstein's bat and Jersey tiger moth. It is also the only place in mainland Britain where the sand crocus (Romulea columnae) can be found – at Dawlish Warren, and is home to all six British native land reptile species, partly as a result of some reintroductions. Another recent reintroduction is the Eurasian beaver, primarily on the river Otter. Other rare species recorded in Devon include seahorses and the sea daffodil.[27][28]

The botany of the county is very diverse and includes some rare species not found elsewhere in the British Isles other than Cornwall. Devon is divided into two Watsonian vice-counties: north and south, the boundary being an irregular line approximately across the higher part of Dartmoor and then along the canal eastwards. Botanical reports begin in the 17th century and there is a Flora Devoniensis by Jones and Kingston in 1829.[29] A general account appeared in The Victoria History of the County of Devon (1906), and a Flora of Devon was published in 1939 by Keble Martin and Fraser.[30] An Atlas of the Devon Flora by Ivimey-Cook appeared in 1984, and A New Flora of Devon, based on field work undertaken between 2005 and 2014, was published in 2016.[31] Rising temperatures have led to Devon becoming the first place in modern Britain to cultivate olives commercially.[32]

In January 2024, plans were announced to plant over 100,000 trees in northern Devon to support Celtic rainforests, which are cherished yet at risk ecosystems in the UK. The project aims to create 50 hectares of new rainforest across three sites, planting trees near existing rainforest areas along the coast and inland. Among the tree species to be planted is the rare Devon whitebeam, known for its unique reproduction method and once-popular fruit. Led by the National Trust and with the assistance of volunteers and community groups, the initiative will focus on locations in Exmoor, Woolacombe, Hartland, and Arlington Court.[33]

Politics and administration

[edit]

The administrative centre and capital of Devon is the city of Exeter. The largest city in Devon, Plymouth, and the conurbation of Torbay (which includes the largest town in Devon and capital of Torbay, Torquay, as well as Paignton and Brixham) have been unitary authorities since 1998, separate from the remainder of Devon which is administered by Devon County Council for the purposes of local government.

Devon County Council is controlled by the Conservatives, and the political representation of its 60 councillors are: 38 Conservatives, 10 Liberal Democrats, six Labour, three Independents, two Green and one South Devon Alliance.[34][35][36]

At the 2024 general election, Devon returned six Liberal Democrats, four Conservatives and three Labour MPs to the House of Commons.[37]

Hundreds

[edit]Historically Devon was divided into 32 hundreds:[38] Axminster, Bampton, Black Torrington, Braunton, Cliston, Coleridge, Colyton, Crediton, East Budleigh, Ermington, Exminster, Fremington, Halberton, Hartland, Hayridge, Haytor, Hemyock, Lifton, North Tawton and Winkleigh, Ottery, Plympton, Roborough, Shebbear, Shirwell, South Molton, Stanborough, Tavistock, Teignbridge, Tiverton, West Budleigh, Witheridge, and Wonford.

Combined County Authority

[edit]Devon County Council and Torbay Council are constituent members of the Devon and Torbay Combined County Authority, which has devolved powers over transport, housing, skills, and support for business.[39]

The authority consists of 12 members: six constituent members with full voting rights, four non-constituent members who do not have voting powers unless extended to them by the constituent members, and two associate members who cannot vote. Devon County Council and Torbay Council each choose half of the constituent members. Two of the non-constituent members are selected collectively by the district councils of Devon to represent their interests, and one is reserved for the Devon and Cornwall Police and Crime Commissioner. The remaining non-constituent member and the two associate members are elected by the constituent members of the authority.[40][41]

Cities, towns and villages

[edit]

The main settlements in Devon are the cities of Plymouth, a historic port now administratively independent, Exeter, the county town, and Torbay, the county's tourist centre. Devon's coast is lined with tourist resorts, many of which grew rapidly with the arrival of the railways in the 19th century. Examples include Dawlish, Exmouth and Sidmouth on the south coast, and Ilfracombe and Lynmouth on the north. The Torbay conurbation of Torquay, Paignton and Brixham on the south coast is now administratively independent of the county. Rural market towns in the county include Barnstaple, Bideford, Honiton, Newton Abbot, Okehampton, Tavistock, Totnes and Tiverton.

The boundary with Cornwall has not always been on the River Tamar as at present: until the late 19th century a few parishes in the Torpoint area were in Devon and five parishes now in north-east Cornwall were in Devon until 1974 (however, for ecclesiastical purposes these were nevertheless in the Archdeaconry of Cornwall and in 1876 became part of the Diocese of Truro).

Religion

[edit]Ancient and medieval history

[edit]The region of Devon was the dominion of the pre-Roman Dumnonii Celtic tribe, known as the "Deep Valley Dwellers". The region to the west of Exeter was less Romanised than the rest of Roman Britain since it was considered a remote part of the province. After the formal Roman withdrawal from Britain in AD 410, one of the leading Dumnonii families attempted to create a dynasty and rule over Devon as the new Kings of Dumnonii.[42]

Celtic paganism and Roman practices were the first known religions in Devon, although in the mid-fourth century AD, Christianity was introduced to Devon.[43][citation needed] In the Sub-Roman period the church in the British Isles was characterised by some differences in practice from the Latin Christianity of the continent of Europe and is known as Celtic Christianity;[44][45][46] however it was always in communion with the wider Roman Catholic Church. Many Cornish saints are commemorated also in Devon in legends, churches and place-names. Western Christianity came to Devon when it was over a long period incorporated into the kingdom of Wessex and the jurisdiction of the bishop of Wessex. Saint Petroc is said to have passed through Devon, where ancient dedications to him are even more numerous than in Cornwall: a probable seventeen (plus Timberscombe just over the border in Somerset), compared to Cornwall's five. The position of churches bearing his name, including one within the old Roman walls of Exeter, are nearly always near the coast, as in those days travelling was done mainly by sea. The Devonian villages of Petrockstowe and Newton St Petroc are also named after Saint Petroc and the flag of Devon is dedicated to him.

The history of Christianity in the South West of England remains to some degree obscure. Parts of the historic county of Devon formed part of the diocese of Wessex, while nothing is known of the church organisation of the Celtic areas. About 703 Devon and Cornwall were included in the separate diocese of Sherborne and in 900 this was again divided into two, the Devon bishop having from 905 his seat at Tawton (now Bishop's Tawton) and from 912 at Crediton, birthplace of St Boniface. Lyfing became Bishop of Crediton in 1027 and shortly afterwards became Bishop of Cornwall.

The two dioceses of Crediton and Cornwall, covering Devon and Cornwall, were united under Edward the Confessor by Lyfing's successor Bishop Leofric, hitherto Bishop of Crediton, who became first Bishop of Exeter under Edward the Confessor, which was established as his cathedral city in 1050. At first, the abbey church of St Mary and St Peter, founded by Athelstan in 932 and rebuilt in 1019, served as the cathedral.

Devon came under the political influence of several different nobles during the Middle Ages, especially the Courtenays Earl of Devon. During the Wars of the Roses, important magnates included the Earl of Devon, William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville, and Humphrey Stafford, earl of Devon whose wider influence stretched from Cornwall to Wiltshire. After 1485, one of the county's influential figures included Henry VII's courtier Robert Willoughby, 1st Baron Willoughby de Broke.[47]

Later history

[edit]In 1549, the Prayer Book Rebellion caused the deaths of thousands of people from Devon and Cornwall. During the English Reformation, churches in Devon officially became affiliated with the Church of England. From the late sixteenth century onwards, zealous Protestantism – or 'puritanism' – became increasingly well-entrenched in some parts of Devon, while other districts of the county remained much more conservative. These divisions would become starkly apparent during the English Civil War of 1642–46, when the county split apart along religious and cultural lines.[48] The Methodism of John Wesley proved to be very popular with the working classes in Devon in the 19th century. Methodist chapels became important social centres, with male voice choirs and other church-affiliated groups playing a central role in the social lives of working class Devonians. Methodism still plays a large part in the religious life of Devon today, although the county has shared in the post-World War II decline in British religious feeling.

The Diocese of Exeter remains the Anglican diocese including the whole of Devon. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Plymouth was established in the mid 19th century.[49]

Symbols

[edit]Coat of arms

[edit]

There was no established coat of arms for the county until 1926: the arms of the City of Exeter were often used to represent Devon, for instance in the badge of the Devonshire Regiment. During the forming of a county council by the Local Government Act 1888 adoption of a common seal was required. The seal contained three shields depicting the arms of Exeter along with those of the first chairman and vice-chairman of the council (Lord Clinton and the Earl of Morley).[50]

On 11 October 1926, the county council received a grant of arms from the College of Arms. The main part of the shield displays a red crowned lion on a silver field, the arms of Richard Plantagenet, Earl of Cornwall. The chief or upper portion of the shield depicts an ancient ship on wavers, for Devon's seafaring traditions. The Latin motto adopted was Auxilio Divino (by Divine aid), that of Sir Francis Drake. The 1926 grant was of arms alone. On 6 March 1962 a further grant of crest and supporters was obtained. The crest is the head of a Dartmoor Pony rising from a "Naval Crown". This distinctive form of crown is formed from the sails and sterns of ships, and is associated with the Royal Navy. The supporters are a Devon bull and a sea lion.[51][52]

Devon County Council adopted a "ship silhouette" logo after the 1974 reorganisation, adapted from the ship emblem on the coat of arms, but following the loss in 1998 of Plymouth and Torbay re-adopted the coat of arms. In April 2006 the council unveiled a new logo which was to be used in most everyday applications, though the coat of arms will continue to be used for "various civic purposes".[53][54]

Flag

[edit]

Devon also has its own flag which has been dedicated to Saint Petroc, a local saint with dedications throughout Devon and neighbouring counties. The flag was adopted in 2003 after a competition run by BBC Radio Devon.[55] The winning design was created by website contributor Ryan Sealey, and won 49% of the votes cast. The colours of the flag are those popularly identified with Devon, for example, the colours of the University of Exeter, the rugby union team, and the Green and White flag flown by the first Viscount Exmouth at the Bombardment of Algiers (now on view at the Teign Valley Museum), as well as one of the county's football teams, Plymouth Argyle. On 17 October 2006, the flag was hoisted for the first time outside County Hall in Exeter to mark Local Democracy Week, receiving official recognition from the county council.[56] In 2019 Devon County Council with the support of both the Anglican and Catholic churches in Exeter and Plymouth, officially recognised Saint Boniface as the Patron Saint of Devon.[57]

Place names and customs

[edit]

Devon's toponyms include many with the endings "coombe/combe" and "tor". Both 'coombe' (valley or hollow, cf. Welsh cwm, Cornish komm) and 'tor' (Old Welsh twrr and Scots Gaelic tòrr from Latin turris; 'tower' used for granite formations) are rare Celtic loanwords in English and their frequency is greatest in Devon which shares a boundary with historically Brittonic speaking Cornwall. Ruined medieval settlements of Dartmoor longhouses indicate that dispersed rural settlement (OE tun, now often -ton) was very similar to that found in Cornish 'tre-' settlements, however these are generally described with the local placename -(a)cott, from the Old English for homestead, cf. cottage. Saxon endings in -worthy (from Anglo-Saxon worthig) indicate larger settlements. Several 'Bere's indicate Anglo-Saxon wood groves, as 'leighs' indicate clearings.[58]

Devon has a variety of festivals and traditional practices, including the traditional orchard-visiting Wassail in Whimple every 17 January, and the carrying of flaming tar barrels in Ottery St. Mary, where people who have lived in Ottery for long enough are called upon to celebrate Bonfire Night by running through the village (and the gathered crowds) with flaming barrels on their backs.[59] Berry Pomeroy still celebrates Queene's Day for Elizabeth I.

Economy and industry

[edit]Devon's total economic output in 2019 was over £26 billion, larger than either Manchester, or Edinburgh.[60] A 2021 report states that "health, retail and tourism account for 43.1% of employment. Agriculture, education, manufacturing, construction and real estate employment are also over-represented in Devon compared with nationally".[61]

Like neighbouring Cornwall to the west, historically Devon has been disadvantaged economically compared to other parts of Southern England, owing to the decline of a number of core industries, notably fishing, mining, and farming, but it is now significantly more diverse. Agriculture has been an important industry in Devon since the 19th century. The 2001 UK foot and mouth crisis harmed the farming community severely.[62] Since then some parts of the agricultural industry have begun to diversify and recover, with a strong local food sector and many artisan producers. Nonetheless, in 2015 the dairy industry was still suffering from the low prices offered for wholesale milk by major dairies and especially large supermarket chains.

The pandemic negatively affected the economy during 2020 and early 2021; an August 2021 report states that "the immediate economic impacts of COVID-19 for the County as a whole [was] as severe as any in living memory".[63]

Between 2014 and 2016, the attractive lifestyle of the area was drawing in new industries which were not heavily dependent upon geographical location;[64][65] Dartmoor, for instance, saw a significant rise in the percentage of its inhabitants involved in the digital and financial services sectors. The Met Office, the UK's national and international weather service, moved to Exeter in 2003. Plymouth hosts the head office and first ever store of The Range, the only major national retail chain headquartered in Devon.

Since the rise of seaside resorts with the arrival of the railways in the 19th century, Devon's economy has been heavily reliant on tourism. The county's economy followed the declining trend of British seaside resorts since the mid-20th century, but with some recent revival and regeneration of its resorts, particularly focused around camping; sports such as surfing, cycling, sailing and heritage. This revival has been aided by the designation of much of Devon's countryside and coastline as the Dartmoor and Exmoor national parks, and the Jurassic Coast and Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Sites. In 2019 the county's visitor spend was almost £2.5 billion.[66] More successful visitor attractions are particularly concentrated on food and drink, including sea-view restaurants in North-West Devon (such as one example belonging to Damien Hurst), walking the South West Coast Path, cycling on the Devon Coast to Coast Cycle Route and other cycle routes such as the Tarka Trail and the Stover Trail; watersports; surfing; indoor and outdoor folk music festivals across the county and sailing in the 5-mile (8.0 km) hill-surrounded inlet (ria) at Salcombe.

Incomes vary significantly and the average is bolstered by a high proportion of affluent retired people. Incomes in much of the South Hams and in villages surrounding Exeter and Plymouth are close to, or above the national average, but there are also areas of severe deprivation, with earnings in some places among the lowest in the UK.

The table also shows the population change in the ten years to the 2011 census by subdivision. It also shows the proportion of residents in each district reliant upon lowest income and/or joblessness benefits, the national average proportion of which was 4.5% as at August 2012, the year for which latest datasets have been published. It can be seen that the most populous district of Devon is East Devon but only if excluding Torbay which has marginally more residents and Plymouth which has approximately double the number of residents of either of these. West Devon has the fewest residents, having 63,839 at the time of the census.

| Unit | JSA or Inc. Supp. claimants (August 2012) % of 2011 population | JSA and Income Support claimants (August 2001) % of 2001 population | Population (April 2011) | Population (April 2001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devon | 2.7% | 6.6% | 746,399 | 704,493 |

| Ranked by district | ||||

| Exeter | 3.5% | 7.5% | 117,773 | 111,076 |

| Torridge | 3.3% | 7.7% | 63,839 | 58,965 |

| North Devon | 2.8% | 7.8% | 93,667 | 87,508 |

| Teignbridge | 2.6% | 6.7% | 124,220 | 120,958 |

| Mid Devon | 2.6% | 6.0% | 77,750 | 69,774 |

| West Devon | 2.5% | 5.9% | 53,553 | 48,843 |

| South Hams | 2.1% | 6.0% | 83,140 | 81,849 |

| East Devon | 1.9% | 5.4% | 132,457 | 125,520 |

| In historic Devon | ||||

| Torbay | 5.3% | 11.0% | 130,959 | 129,706 |

| Plymouth | 5.1% | 9.5% | 256,384 | 240,720 |

Transport

[edit]Bus

[edit]There is a network of buses across Devon, the largest operator in Devon is Stagecoach South West, having operated 93% of services in the county in 2021.[68] Smaller operators include Dartline, Country Bus and Plymouth Citybus.

Devon County Council oversees and co-ordinates bus transport through DevonBus, an Enhanced Partnership covering the county, with the purpose of improving the network and creating a unified brand for buses in the county.[69]

Rail

[edit]The key train operator for Devon is Great Western Railway, which operates numerous regional, local and suburban services, as well as inter-city services north to London Paddington and south to Plymouth and Penzance. Other inter-city services are operated by CrossCountry north to Manchester Piccadilly, Edinburgh Waverley, Glasgow Central, Dundee, Aberdeen and south to Plymouth and Penzance; and by South Western Railway, operating hourly services between London Waterloo and Exeter St Davids, via the West of England Main Line. All Devon services are diesel-hauled, since there are no electrified lines in the county.

Okehampton station in Devon was closed in 1972 to passenger traffic as a result of the Beeching cuts, but regained regular passenger services run by GWR to Exeter in November 2021, funded by the UK Government's Restoring your Railway programme.

There are proposals to reopen the line from Tavistock to Bere Alston for a through service to Plymouth.[70] The possibility of reopening the line between Tavistock and Okehampton, to provide an alternative route between Exeter and Plymouth, has also been suggested following damage to the railway's sea wall at Dawlish in 2014, which caused widespread disruption to trains between Exeter and Penzance. However, a study by Network Rail determined that maintaining the existing railway line would offer the best value for money[71] and work to strengthen the line at Dawlish began in 2019.[72]

Devon Metro

[edit]Devon County Council has proposed a 'Devon Metro' scheme to improve rail services in the county and offer a realistic alternative to car travel. This includes the opening of Cranbrook station in December 2015, plus four new stations to be constructed (including Edginswell) as a priority.[73] Several elements of the scheme have, or are in the process of being delivered including the building of Marsh Barton station on the edge of Exeter[74] which was opened in July 2023,[75] and a regular half hourly local rail service now extended from the Avocet Line across Exeter to include the Riviera Line.[76]

Air

[edit]Exeter Airport is the only passenger airport in Devon and in 2019 was used by over one million people. Until 2020, Flybe had its headquarters at the airport. Destinations include various locations within the UK (London City, Manchester, Belfast, Edinburgh, etc.), as well as locations in Cyprus, Italy, Netherlands, Lapland, Portugal, Spain, France, Malta, Switzerland and Turkey.[77]

Education

[edit]Devon has a mostly comprehensive education system. There are 37 state and 23 independent secondary schools. There are three tertiary (FE) colleges and an agricultural college (Bicton College, near Budleigh Salterton). Torbay has eight state (with three grammar schools) and three independent secondary schools, and Plymouth has 17 state (with three grammar schools – two all-girls and one all-boys) and one independent school, Plymouth College. East Devon and Teignbridge have the largest school populations, with West Devon the smallest (with only two schools). Only one school in Exeter, Mid Devon, Torridge and North Devon have a sixth form – the schools in other districts mostly have sixth forms, with all schools in West Devon and East Devon having a sixth form.

Three universities are located in Devon, the University of Exeter (split between the Streatham Campus and St Luke's Campus, both in Exeter, and a campus in Cornwall); in Plymouth the University of Plymouth in Britain is present, along with the University of St Mark & St John to the city's north. The universities of Exeter and Plymouth have together formed the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry which has bases in Exeter and Plymouth. There is also Schumacher College.

Cuisine

[edit]The county has given its name to a number of culinary specialities. The Devonshire cream tea, involving scones, jam and clotted cream, is thought to have originated in Devon (though claims have also been made for neighbouring counties); in other countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, it is known as a "Devonshire tea".[78][79][80] It has also been claimed that the pasty originated in Devon rather than Cornwall, with the first record of the pasty coming from Plymouth in 1509.[81]

In October 2008, Devon was awarded Fairtrade County status by the Fairtrade Foundation.[82][83]

Sport

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

Devon has been home to a number of customs, such as its own form of Devon wrestling, similar in some ways to Cornish wrestling. As recently as the 19th century, a crowd of over 17,000 at Devonport, near Plymouth, attended a match between the champions of Devon and Cornwall.[84] Another Devon sport was outhurling which was played in some regions until the 20th century (e.g. 1922, at Great Torrington).[85] Other ancient customs which survive include Dartmoor step dancing, and "Crying The Neck".

Devon has three professional football teams, based in each of its most populous towns and cities. As of 2025, Plymouth Argyle F.C. and Exeter City F.C. compete in the EFL League One, whilst Torquay United F.C. compete in the National League. Plymouth's highest Football League finish was fourth in the Second Division, which was achieved twice, in 1932 and 1953. Torquay and Exeter have never progressed beyond the third tier of the league; Torquay finished second on goal average in the Third Division (S) behind Sir Alf Ramsey's Ipswich Town in 1957. Exeter's highest position has been eighth in the Third Division (S). The county's biggest non-league clubs are Plymouth Parkway F.C. and Tiverton Town F.C. which compete in the Southern Football League Premier Division, and Bideford A.F.C., Exmouth Town F.C. and Tavistock A.F.C. which are in the Southern Football League Division One South and West.

Rugby Union is popular in Devon with over forty clubs under the banner of the Devon Rugby Football Union, many with various teams at senior, youth and junior levels. One club – Exeter Chiefs – play in the Aviva Premiership, winning the title in 2017 for the first time in their history after beating Wasps RFC in the final 23–20. Plymouth Albion who are, as of 2023[update], in the National League 1 (The third tier of English Professional Rugby Union).

There are five rugby league teams in Devon: Plymouth Titans, Exeter Centurions, and Devon Sharks from Torquay, North Devon Raiders from Barnstaple, and East Devon Eagles from Exmouth. They all play in the Rugby League Conference.

Plymouth City Patriots represent Devon in the British Basketball League. Formed in 2021, they replaced the former professional club, Plymouth Raiders, after the latter team were withdrawn from competition due to venue issues.[86] Motorcycle speedway is also supported in the county, with both the Exeter Falcons and Plymouth Gladiators succeeding in the National Leagues in recent years.

The University of Exeter Hockey Club enter teams in both the Men's and Women's England Hockey Leagues.

Horse Racing is also popular in the county, with two National Hunt racecourses (Exeter and Newton Abbot), and numerous point to point courses. There are also many successful professional racehorse trainers based in Devon.

The county is represented in cricket by Devon County Cricket Club, who play at a Minor counties level.

Notable Devonians

[edit]-

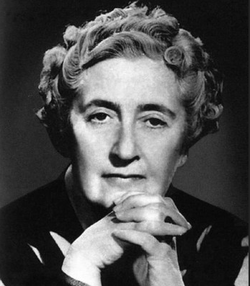

Agatha Christie, best selling crime novelist

-

Chris Martin, lead singer of Coldplay

-

Roger Deakins, multi-award winning cinematographer

-

Ollie Watkins, plays football for England

Devon is known for its mariners, such as Sir Francis Drake, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, Sir Richard Grenville, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Francis Chichester and Sir William Robert Patrick Knox-Johnston.[87] Henry Every, described as the most notorious pirate of the late 17th century, was probably born in the village of Newton Ferrers.[88] John Oxenham (1536–1580) was a lieutenant of Drake but considered a pirate by the Spanish. Thomas Morton (1576–1647) was an avid Elizabethan outdoorsman probably born in Devon who became an attorney for The Council For New England, and built the New England fur-trading-plantation called Ma-Re Mount or Merrymount around a West Country-style Maypole, much to the displeasure of Pilgrim and Puritan colonists. Morton wrote a 1637 book New English Canaan about his experiences, partly in verse, and may have thereby become America's first poet to write in English.[89] Another famous mariner and Devonian was Robert Falcon Scott, the leader of the unfortunate Terra Nova Expedition to reach the geographical South Pole.[90]

The actor Matthew Goode was raised in Devon, and Bradley James, also an actor, was born there. The singer Joss Stone was brought up in Devon and frontman Chris Martin from the British rock group Coldplay was born there. Matt Bellamy, Dominic Howard and Chris Wolstenholme from the English group Muse all grew up in Devon and formed the band there. Dave Hill of rock band Slade was born in Flete House which is in the South Hams district of Devon. Singer-songwriter Ben Howard grew up in Totnes, a small town in Devon. Another famous Devonian is the model and actress Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, who was born in Plymouth and raised in Tavistock. The singer and songwriter Rebecca Newman was born and raised in Exmouth.[91] Roger Deakins, called "the pre-eminent cinematographer of our time", was born and lives in Devon.[92]

Ollie Watkins, professional footballer was born in Devon.[93] Similarly, footballer Trevor Francis was raised in Devon.[94] Swimmer Sharron Davies[95] and diver Tom Daley[96] were born in Plymouth. The Olympic runner Jo Pavey was born in Honiton. Peter Cook the satirist, writer and comedian was born in Torquay, Devon. Leicester Tigers and British and Irish Lions Rugby player Julian White was born and raised in Devon and now farms a herd of pedigree South Devon beef cattle. The dog breeder John "Jack" Russell was also from Devon. Jane McGrath, who married Australian cricketer Glenn McGrath was born in Paignton, her long battle with and subsequent death from breast cancer inspired the formation of the McGrath Foundation, which is one of Australia's leading charities.

Devon has also been the home, inspiration or base for a number of notable writers, artists, entrepreneurs and politicians. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the crime writers Agatha Christie and Bertram Fletcher Robinson, the Irish writer William Trevor, and the poet Ted Hughes lived in Devon. The painter and founder of the Royal Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds, was born in Devon. Chris Dawson, the billionaire owner of retailer The Range was born in Devon, where his business retains its head office in Plymouth. Devon has also been represented in the House of Commons by notable Members of Parliament (MPs) such as Nancy Astor, Gwyneth Dunwoody, Michael Foot and David Owen and the Prime Ministers Lord John Russell and Lord Palmerston.

See also

[edit]- Category:Rivers of Devon

- Circular linhay

- Custos Rotulorum of Devon – Keepers of the Rolls

- Devon Sinfonia

- Duchy of Cornwall

- Healthcare in Devon

- List of High Sheriffs of Devon

- List of English and Welsh endowed schools (19th century)#Devon

- List of hills of Devon

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Devon

- List of monastic houses in Devon

- List of MPs for Devon constituency

- List of Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Devon

- North Devon Coast

- Tamar Valley AONB

- West Country English

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Data is collected by local authority areas (Devon, Plymouth, Torbay respectively). Total population of Devon is 1,133,742 (746,399 + 256,384 + 130,959). Percentage of ethnically Irish persons is 0.4%.[4]

- ^ Data is collected by local authority areas (Devon, Plymouth, Torbay respectively). Total population of Devon is 1,133,742 (746,399 + 256,384 + 130,959). Total population of White British persons is 1,071,015 (708,590 + 238,263 + 124,162). Percentage of White British persons is 94.467%.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "Lord-Lieutenant for Devon: David Fursdon – Press releases". GOV.UK. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "No. 64681". The London Gazette. 14 March 2025. p. 5010.

- ^ a b "Mid-2022 population estimates by Lieutenancy areas (as at 1997) for England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. 24 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ a b "2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Mid-Year Population Estimates, United Kingdom, June 2024". Office for National Statistics. 26 September 2025. Retrieved 26 September 2025.

- ^ "Custom report - Nomis - Official Census and Labour Market Statistics". www.nomisweb.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ "William Camden, Britannia (1607) with an English translation by Philemon Holland – Danmonii". The University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on 16 March 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ "Manuscript A: The Parker Chronicle". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2000). The Isles: A History. Macmillan. p. 207. ISBN 0-333-69283-7.

- ^ "Who do you think you really are? A genetic map of the British Isles – University of Oxford". Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Who do you think you really are? The first fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles". wellcome.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ jobs (18 March 2015). "UK mapped out by genetic ancestry : Nature News & Comment". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17136. S2CID 88369661. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Lydford Silver Pennies In The Stockholm Coin Museum". Lydford.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Heale, M. (2016). The Abbots and Priors of Late Medieval and Reformation England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-19870-253-5.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter (2014). Rebellion: The History of England from James I to the Glorious Revolution. Macmillan. p. 465. ISBN 978-1-4668-5599-1.

- ^ "Devon's Mining History and Stannary parliament". users.senet.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- ^ Dewey, Henry (1948) British Regional Geology: South West England, 2nd ed. London: H.M.S.O.

- ^ Whitaker's Almanack, 1972; p. 631

- ^ "NATIONAL PARK FACTS". Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ^ Edmonds, E. A., et al. (1975) South-West England; based on previous editions by H. Dewey (British Geological Survey UK Regional Geology Guide series no. 17, 4th ed.) London: HMSO ISBN 0-11-880713-7

- ^ Hesketh, Robert (2006). Devon's Geology: An Introduction. Bossiney Books. ISBN 978-1-899-383-89-4.

- ^ Laming, Deryck; Roche, David. "Devon Geology Guide – Devonian Slates, Sandstones and Volcanics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Devon's Rocks – A Geological Guide". Devon County Council. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Edmonds, E. A.; McKeown, M. C.; Williams, M. (1975). "Carboniferous Rocks". South-West England. British Geology. Dewey, H. (4th ed.). London: HMSO/British Geological Survey. p. 34. ISBN 0-11-880713-7.

- ^ "The Society – Introduction". Devon Birds. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "Designated sites view (Devon)". Natural England. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "Hippocampus Rafinesque, 1810". NBN Atlas. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ "Pancratium maritimum L." NBN Atlas. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Jones, John Pike & Kingston, J. F. (1829) Flora Devoniensis. 2 pts, in 1 vol. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green

- ^ Martin, W. Keble & Fraser, G. T. (eds.) (1939) Flora of Devon. Arbroath

- ^ Smith, R.; Hodgson, B.; Ison, J. (2016). A New Flora of Devon. Exeter: The Devonshire Association. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-5272-0525-3.

- ^ Paul Simons (14 May 2007). "Britain warms to the taste for home-grown olives". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Morris, Steven (29 January 2024). "More than 100,000 trees to be planted in Devon to boost Celtic rainforest". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Clarke, Lewis (9 March 2023). "Councillor quits over 'shocking state' of Devon roads". Devon Live. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ Merritt, Anita (12 January 2024). "Ex lord mayor blames 'gaslighting and bullying' for shock exit". Devon Live. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ "Councils Map | LocalCouncils.co.uk". www.localcouncils.co.uk. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ "'Disastrous night' for Conservatives in Devon, former MP says". BBC News. 5 July 2024. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ "Devon Hundreds". Newcastle University. 23 June 2013. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Devolution FAQs - Devon and Torbay Devolution Deal". 9 February 2024. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Devon and Torbay Combined County Authority – Final Proposal" (PDF). Torbay Council. 3 May 2024. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Signed legislation brings Devon and Torbay Combined County Authority into being". DevonAir Radio. 12 February 2025. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ^ "Britannia History: Overview of Devon". britannia.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Devon Libraries: Sources for Anglo-Saxon Devon" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017.

- ^ Bowen, E. G. (1977) Saints, Seaways and Settlements in the Celtic Lands. Cardiff: University of Wales Press ISBN 0-900768-30-4

- ^ "St. Patrick and Celtic Christianity: Did You Know?". Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Monasticism – The Heart of Celtic Christianity – Northumbria Community". Northumbria Community. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Stansfield-Cudworth, R. E. (2009). Political Elites in South-West England, 1450–1500: Politics, Governance, and the Wars of the Roses. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 165–73, 206–13, 321–29. ISBN 978-0-77344-714-1.

- ^ Stoyle, Mark (1994). Loyalty and Locality: Popular Allegiance in Devon During the English Civil War. Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press. p. passim. ISBN 978-0-85989-428-9.

- ^ "Home". Plymouth-diocese.org.uk. 15 February 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Fox-Davies, A. C. (1915) The Book of Public Arms, 2nd edition, London

- ^ W. C. Scott-Giles, Civic Heraldry of England and Wales, 2nd edition, London, 1953

- ^ "A brief history of Devon's coat of arms (Devon County Council)". Devon.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ "Council's designs cause logo row". BBC News. 27 March 2006. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ "Policy and Resources Overview Scrutiny Committee Minutes, 3 April 2006". Devon.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ "Flag celebrates Devon's heritage". BBC. 18 July 2003. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ Devon County Council Press Release, 16 October 2006 Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quick, Alan (24 May 2019). "St Boniface of Crediton to become Patron Saint of Devon". Crediton Country Courier. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Origins of Devon Place-Names". Newcastle University. 2 November 2014. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Ottery Tar Barrels". BBC. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- ^ "Regional gross value added (balanced) per head and income components – Office for National Statistics". Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "Strategic Plan 2021-2025". Devon County Council. 15 June 2021. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ In Devon, the county council estimated that 1,200 jobs would be lost in agriculture and ancillary rural industries – Hansard, 25 April 2001 Archived 4 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Economy Service Briefing" (PDF). Devon County Council. 15 August 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2024. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ "Devon Delivers". Invest Devon. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "NORTHERN DEVON Economic Strategy 2014 – 2020" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "tourism trends 2005.pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Key Statistics: Population; Quick Statistics: Economic indicators Archived 11 February 2003 at the Wayback Machine. (2011 census and 2001 census) Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "Enhanced Partnership Plan and Scheme". Devon County Council. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ "DevonBus Enhanced Partnership". TravelDevon. Devon County Council. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ Harris, Nigel (2008). "Taking trains back to Tavistock". Rail (590). Bauer: 40–45.

- ^ "West of Exeter Route Resilience Study" (PDF). Network Rail. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Dawlish Sea Wall". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Devon Metro – fulfilling the potential of rail" (PDF). Devon City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "Work starts on Marsh Barton rail station – News". Devon City Council. 15 April 2021. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Parker-Bray, Michael (4 July 2023). "Marsh Barton station now open". Devon and Cornwall Rail Partnership. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "D1 Train Times" (PDF). Great Western Railway. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Flights & Holidays". Exeter Airport. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Mason, Laura; Brown, Catherine (1999) From Bath Chaps to Bara Brith. Totnes: Prospect Books

- ^ Pettigrew, Jane (2004) Afternoon Tea. Andover: Jarrold

- ^ Fitzgibbon, Theodora (1972) A Taste of England: the West Country. London: J. M. Dent

- ^ BBC News, "Devon invented the Cornish pasty", 13 November 2006 Archived 4 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 January 2020

- ^ Bulmer, Joseph (20 October 2008). "Devon achieves Fairtrade status". North Devon Gazette. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ "Fairtrade". Devon County Council. 20 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ "Devon Wrestling". Crediton Museum. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ "Out Hurling". Football origins. 20 June 2013. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ "Plymouth Raiders replaced in BBL by new basketball team Plymouth Patriots". Plymouth Herald. 9 August 2021. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Sailing legend crosses the line". BBC News. 4 May 2007.

- ^ Marley, David F. (2010). Pirates of the Americas. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 589. ISBN 978-1-59884-201-2.

- ^ New English Canaan or New Canaan. Containing an abstract of New England, composed in three bookes. The first booke setting forth the originall of the natives, their manners and customes, together with their tractable nature and love towards the English. The second booke setting forth the naturall indowments of the country, and what staple commodities it yealdeth. The third booke setting forth, what people are planted there, their prosperity, what remarkable accidents have happened since the first planting of it, together with their tenents and practise of their church. Written by Thomas Morton of Cliffords Inne gent, upon tenne yeares knowledge and experiment of the country. Amsterdam: Jacob Stam

- ^ H. G. R. King, 'Scott, Robert Falcon (1868–1912)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, January 2011 accessed 21 June 2011

- ^ "'Rising star' returns to Exmouth to support RNLI". 23 October 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cinematographer Roger Deakins Takes Visceral Approach To His Craft". Variety. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "South Devon's star footballer Ollie Watkins fires England into Euro 24 final". Torbay Today. 10 July 2024. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Trevor Francis, Nottingham Forest and England striker who became Britain's first £1 million player – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. 24 July 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "New centre to honour Plymouth Olympian Sharron Davies". Plymouth City Council. 14 March 2007. Archived from the original on 30 March 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ^ "tom daley olympic hero goes back to school, Eggbuckland Community College in Plymouth, Devon". This is Bristol. 3 September 2008. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Oliver, George (1846–1889). Monasticon Dioecesis Exoniensis: being a collection of records and instruments illustrating the ancient conventual, collegiate, and eleemosynary foundations, in the Counties of Cornwall and Devon, with historical notices, and a supplement, comprising a list of the dedications of churches in the Diocese, an amended edition of the taxation of Pope Nicholas, and an abstract of the Chantry Rolls (with supplement and index). Exeter: P. A. Hannaford.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1952). North Devon. Buildings of England. London: Penguin Books.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1952). South Devon. Buildings of England. London: Penguin Books.

- Stabb, John (1908–1916). Some Old Devon Churches: Their Rood Screens, Pulpits, Fonts, Etc. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Vol. I, Vol. II, and Vol. III.

- Stansfield-Cudworth, R. E. (2009). Political Elites in South-West England, 1450–1500: Politics, Governance, and the Wars of the Roses. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-77344-714-1.

- Stansfield-Cudworth, R.E. (2013). "The Duchy of Cornwall and the Wars of the Roses: Patronage, Politics, and Power, 1453–1502". Cornish Studies. 2nd Series. 21: 104–50. doi:10.1386/corn.21.1.104_1 (inactive 11 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link)

External links

[edit]- Devon County Council

- BBC Devon Archived 15 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Genuki Devon Archived 1 April 2003 at the Wayback Machine Historical, geographical and genealogical information

- The Devonshire Association, a Devon-centric equivalent of the British Association

- Images of Devon at the English Heritage Archive

- Dartmoor Step Dancing and Broom Dance at South Tawton. 5PY Heritage. 30 September 2025 [1971].

Devon

View on GrokipediaDevon is a ceremonial county in South West England, encompassing approximately 6,700 square kilometres of varied terrain including moorlands, coastlines, and river valleys, with a population of around 1.2 million.[1][2] The county is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, the English Channel to the south, and the counties of Somerset and Dorset to the east and Cornwall to the west, featuring two national parks—Dartmoor and Exmoor—that preserve large expanses of upland and heathland. Administratively, it includes the Devon County Council area along with the unitary authorities of Plymouth and Torbay, with Exeter as the historic county town and administrative centre.[3] Devon's economy is anchored in tourism, agriculture, and public services, with tourism contributing over £2 billion annually and supporting more than 30,000 jobs through attractions like its 650 kilometres of coastline and rural landscapes. Agriculture represents 13% of the local economy—higher than the national average of 7.6%—with significant output in livestock exceeding £1 billion in value and crops around £196 million as of 2022, reflecting the county's fertile soils and pastoral farming traditions. The area's low population density of about 184 people per square kilometre underscores its rural character, which supports biodiversity but also poses challenges for infrastructure and economic diversification beyond seasonal tourism.[4][5][6][7]

Etymology

Origins and evolution of the name

The name of the county derives from the Dumnonii, a Celtic tribe that occupied southwestern Britain during the Iron Age, with their territory encompassing modern Devon and Cornwall.[8] The tribal name appears in Roman sources as Dumnonii, first recorded by Ptolemy in his Geography around 150 AD, likely stemming from the Proto-Celtic root dumno- meaning "deep" or "abyss," possibly alluding to the region's rugged topography of deep valleys or a mythological association with depth, as theorized by Celtic scholar John Rhys linking it to the goddess Domnu ("the deep").[8] Alternative interpretations suggest Dyfneint, a Brythonic form implying "deep valley dwellers," reflecting the landscape's features, though empirical linguistic evidence favors the "deep" etymology over unsubstantiated folk derivations.[9] Following the Anglo-Saxon settlement, the name evolved into Old English Defenascir or Defna scīr ("shire of the Dumnonii" or "Defnas"), denoting the tribal territory under West Saxon control, with early attestations in charters from the late 9th century, such as those referencing boundaries in Devon around 880–900 AD during the reign of Alfred the Great.[10] This Germanic adaptation preserved the Celtic core while integrating shire terminology, distinguishing it from neighboring regions like Cornwall. Norman influence after 1066 simplified it to Devon or Devonscira, as seen in the Domesday Book of 1086, where the county is enumerated as Devenschire, reflecting phonetic anglicization and administrative standardization without altering the underlying tribal root.[10] The modern form "Devon" emerged by the late medieval period, supplanting "Devonshire" in everyday usage by the 20th century, though the latter persists in formal contexts like Devonshire cream. This evolution avoids conflation with locales like Devonport (a Plymouth suburb named post-17th century for its port facilities, unrelated to the county's ancient tribal origin), emphasizing the name's continuity from prehistoric Celtic ethnonyms rather than later toponymic inventions.[10]History

Prehistoric and early human occupation

The earliest evidence of human occupation in Devon dates to the Paleolithic period, with significant finds at Kent's Cavern near Torquay, where stone tools and a human jaw fragment indicate the presence of early modern humans at least 40,000 years ago.[11] The site has yielded artifacts from multiple Paleolithic stages, including handaxes and other lithic tools, preserved in cave deposits spanning up to 500,000 years of intermittent sedimentation and frost action.[12] Mesolithic hunter-gatherer activity, from approximately 10,000 to 4,000 BCE, is attested by scatters of microlithic flint tools and temporary campsites, particularly on coastal sites like Baggy Point in North Devon and inland areas such as Dartmoor, where recent excavations uncovered stone fragments linked to foraging economies adapted to post-glacial woodlands and coasts.[13][14] These ephemeral settlements reflect mobile populations exploiting marine and terrestrial resources, with evidence often limited to debitage and barbs due to sea-level rise eroding many coastal sites.[15] Neolithic farming communities, emerging around 4,000 BCE, left traces of megalithic structures and field systems, though less monumental than in other regions; small-scale enclosures and standing stones, dated between 4,500 and 3,000 years ago, suggest ritual and territorial markers amid the transition to agriculture.[16] The Bronze Age (c. 2,500–800 BCE) saw intensified settlement and resource extraction, including the origins of tin mining around 2,000 BCE in stream works on Dartmoor and coastal areas, fueling early metallurgy with cassiterite deposits. Barrow cemeteries and enclosures like Grimspound on Dartmoor, a late Bronze Age village of 24 stone roundhouses within a 4-acre walled enclosure dated 1,450–700 BCE, indicate semi-permanent agro-pastoral communities managing livestock and crops on the moorland.[17][18] Iron Age populations (c. 800 BCE–43 CE), associated with the Dumnonii tribe, constructed over 40 hillforts across Devon, such as those documented in regional surveys, featuring ramparts and enclosures that supported defended settlements and controlled trade routes.[19] Archaeological estimates suggest these sites housed communities of dozens to hundreds, reflecting a tribal society with estimated regional populations growing amid broader British Iron Age demographic expansion to 4–5 million by the Roman era, though Devon-specific figures remain imprecise due to limited excavation data.[20][21]Roman era and early medieval period

The Roman conquest of the south-west of Britain, including the territory of the Dumnonii tribe in what is now Devon, followed the Claudian invasion of AD 43, with significant military advances occurring in the AD 50s under the governor Publius Ostorius Scapula and later Vespasian.[22] By around AD 55, the Legio II Augusta established Isca Dumnoniorum as a legionary fortress at modern Exeter, serving as a base for operations against tribal resistance and facilitating control over the region.[23] The fortress was succeeded by a civilian settlement that became the civitas capital of the Dumnonii, though archaeological evidence reveals limited urbanization: few substantial villas or towns beyond Exeter, with a focus on military infrastructure such as forts at sites like North Tawton and Old Burrow, and roads including Iter XV linking to other western outposts.[24] This contrasts with denser Roman development in south-eastern Britain, indicating shallower Romanization in Devon, where native Iron Age roundhouses persisted alongside imported pottery and coins, but with sparse evidence of widespread cultural assimilation.[23] Roman administration waned after AD 410 with the empire's withdrawal, leading to a sub-Roman phase marked by economic contraction and the emergence of the British kingdom of Dumnonia, encompassing Devon, Cornwall, and parts of Somerset as a successor polity to the Dumnonii.[21] Archaeological finds suggest some continuity of elite activity, including Mediterranean imports like amphorae and fine wares at coastal sites, pointing to sustained trade links despite the collapse of centralized Roman governance.[25] Early Christianization is evidenced by sparse sites, such as inscribed slates at Tintagel indicating literate Christian practices from the 5th to 7th centuries, potentially tied to a high-status stronghold rather than widespread monastic foundations.[25] From the 7th century, Anglo-Saxon expansion from the Kingdom of Wessex exerted pressure on Dumnonia, with kings like Cenwalh (r. 643–645, 648–672) and Ine (r. 688–726) advancing westward through military campaigns and settlement.[26] This is reflected in the proliferation of Old English place-name elements in Devon, such as -worthy (from OE *worðig, denoting enclosures), -cott (from OE cot, small huts), and -ham (from OE hām, homesteads), which cluster in eastern and central Devon and indicate phased Saxon colonization rather than abrupt conquest.[27] Brittonic resistance persisted, as seen in the Battle of Hehil around AD 721, where Dumnonian forces under Geraint defeated Wessex troops in west Devon, temporarily halting advances.[28] By the 9th century, under Egbert (r. 802–839) and Alfred the Great (r. 871–899), Wessex achieved fuller integration of Devon through further incursions and defensive burhs, consolidating control amid Viking raids, as demonstrated by the Wessex victory at the Battle of Cynwit in 878 near Countisbury.[21][29] This marked the effective end of independent Dumnonia, with Devon incorporated as a frontier shire of Wessex by the late 9th century, though Celtic linguistic and cultural traces lingered in western areas.[30]Medieval development and feudal structure

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, William I imposed a feudal system on Devon, redistributing lands primarily to Norman lords as tenants-in-chief holding directly from the crown in exchange for military service and other obligations, with the Domesday Book of 1086 serving as the foundational survey to record manors, resources, and taxable values across the county's boroughs and estates for assessing the geld tax and royal revenue potential.[31] This enumeration documented approximately 77 such tenants-in-chief in Devon, many non-resident, overseeing subdivided manors worked by villeins under customary tenures like socage or serfdom, which entrenched hierarchical obligations for labor and produce while enabling lords to extract rents and fines.[32] Monastic houses, initially limited to pre-Conquest Benedictine foundations like Tavistock Abbey (refounded c. 961 but reorganized post-1066) and Buckfast, expanded under feudal patronage, with around 30 religious institutions by the late medieval period exerting influence over estates through grants of demesne lands and tithes, fostering agricultural management and spiritual oversight amid the manorial economy.[33][34] Economic shifts from agrarian feudalism toward commodity production emerged by the 13th century, with Devon's wool trade gaining prominence as sheep farming on manorial pastures supplied raw fleece for export, underpinning regional wealth before the peak English wool economy of 1250–1350; Exeter's cloth industry, centered on fulling and weaving local wool into kerseys, became a key export driver from c. 1300, regulated by guilds like the Tuckers' Incorporation to standardize quality and control markets.[35][36] Tin mining, vital in western Devon, operated under stannary customs granting tinners exemptions from certain feudal dues and self-governing courts, with formalized regulations emerging via the 1494 Great Court of Devon tinners to organize streaming and smelting amid rising output taxed by the crown at coinage mills.[37] The Black Death of 1348–49 exacerbated labor shortages in Devon's manors, prompting pollen evidence of shifted land use toward pasture over arable as population fell sharply—mirroring broader European declines of 40% or more—eroding traditional serfdom by enabling surviving tenants to negotiate higher wages, commutation of labor services, and freer movement, thus weakening feudal bonds.[38][39] By the 15th century, recovering demographics and trade fueled prosperity, evidenced by widespread parish church reconstructions—such as the addition of Perpendicular-style towers and aisles from the 13th–15th centuries—reflecting manorial investments in communal piety and status, with over 620 surviving medieval or rebuilt structures indicating stabilized feudal hierarchies adapting to post-plague commodification rather than outright collapse.[40][41] Feudal land tenure persisted into 1500, with inheritance via primogeniture and subinfeudation maintaining lord-tenant relations, though enclosures for sheep and stannary privileges hinted at transitions toward proto-capitalist elements within the manorial framework.[42]Tudor and Stuart periods

The Dissolution of the Monasteries between 1536 and 1541, enacted by Henry VIII, led to the closure of religious houses across England, including several in Devon such as Buckfast Abbey and Torre Abbey, with their lands and assets seized by the Crown and subsequently redistributed to secular landowners, particularly the local gentry.[43] This transfer strengthened the economic position of Protestant-leaning gentry families, who benefited from the influx of former monastic estates, fostering a shift toward lay control over agrarian resources and indirectly supporting the erosion of traditional Catholic influence in the region.[44] However, the subsequent push for Protestant reforms under Edward VI provoked significant resistance; the Prayer Book Rebellion erupted in June 1549, beginning at Sampford Courtenay in Devon, where parishioners rejected the imposition of the Book of Common Prayer in English, demanding the restoration of Latin masses, the Six Articles, and relief from economic grievances like the sheep tax.[45] The uprising spread across Devon and into Cornwall, drawing up to 10,000 rebels who besieged Exeter but were ultimately defeated by forces under John Russell, Lord Privy Seal, resulting in approximately 4,000 rebel deaths by August 1549.[46] During the English Civil War (1642–1651), Devon exhibited divided allegiances, with Plymouth serving as a staunch Parliamentarian stronghold that withstood Royalist assaults, while Exeter became a key Royalist base under Prince Maurice, housing the court of Queen Henrietta Maria until its prolonged siege.[47] The Siege of Exeter from late 1645 to April 1646, conducted by Sir Thomas Fairfax's New Model Army, inflicted heavy losses primarily through plague rather than combat, with estimates indicating thousands of garrison and civilian deaths—exacerbated by famine and disease—leading to the city's surrender and the evacuation of Royalist forces, thereby securing Parliamentarian dominance in the Southwest.[48] Casualty figures from the siege are imprecise due to the dominance of epidemic mortality, but parish records and military accounts suggest over 5,000 perished within the walls, highlighting the war's demographic toll on the region without commensurate battlefield engagements.[49] Amid these upheavals, Devon's maritime economy demonstrated resilience through the expansion of fisheries and naval activities, particularly under Elizabeth I, when Plymouth emerged as a critical naval hub; Sir Francis Drake, a Devon native, departed from the port for his circumnavigation in 1577 and famously contributed to the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, with fleets assembling there for repairs and provisioning.[50] The Tudor-era fisheries grew substantially, with Devon vessels targeting Irish hake in the 1530s and expanding to Newfoundland cod by the early Stuart period, employing around 10,000 Devon sailors by the 1620s and integrating with broader Atlantic trade routes that bolstered local ports like Bideford and Barnstaple.[51] Smuggling supplemented legitimate trade, evading customs on goods like brandy and tea amid rising Stuart-era duties, though quantitative economic data remains sparse; court records indicate persistent illicit activity along Devon's rugged coastlines, sustaining coastal communities despite naval patrols and contributing to regional adaptability in the face of wartime disruptions.[52]Industrial Revolution and 19th century