Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lundy

View on Wikipedia

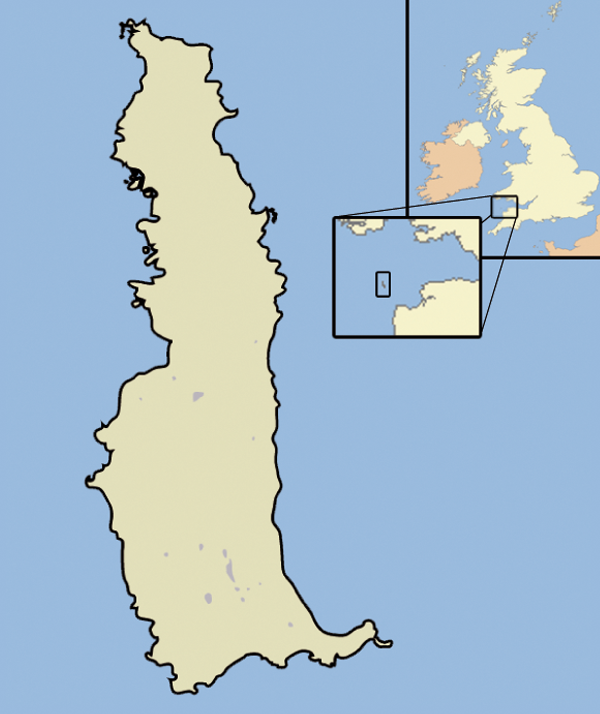

Lundy is an English island in the Bristol Channel. It forms part of the district of Torridge in the county of Devon.

Key Information

About 3 miles (5 kilometres) long and 5⁄8 mi (1 km) wide, Lundy has had a long and turbulent history, frequently changing hands between the British crown and various usurpers. In the 1920s, the island's owner, Martin Harman, tried to issue his own coinage and was fined. In 1941, two German Heinkel He 111 bombers crash landed on the island, and their crews were captured.

In 1969, Lundy was purchased by British millionaire Jack Hayward, who donated it to the National Trust. It is now managed by the Landmark Trust, a conservation charity that derives its income from day trips and holiday lettings, most visitors arriving by boat from Bideford or Ilfracombe. A local tourist curiosity is the special "Puffin" postage stamp, a category known by philatelists as "local carriage labels", a collector's item.

As a steep, rocky island, often shrouded by fog, Lundy has been the scene of many shipwrecks, and the remains of its old lighthouse installations are of both historic and scientific interest. Its present-day lighthouses, one of which is solar-powered, are fully automated. Lundy has a rich bird life, as it lies on major migration routes, and attracts many vagrant as well as indigenous species. It also boasts a variety of marine habitats, with rare seaweeds, sponges and corals. In 2010, the island became Britain's first Marine Conservation Zone.

Profile

[edit]

Lundy is the largest island in the Bristol Channel. It lies 10 nautical miles (19 km) off the coast of Devon, about a third of the distance across the channel from Devon to Pembrokeshire in Wales.[3] Lundy gives its name to a British sea area.[4] Lundy is included in the district of Torridge in Devon. In 2007, it had a resident population of 28 people. These include a warden, a ranger, an island manager, a farmer, bar and housekeeping staff, and volunteers. Most live in and around the village at the south of the island. Visitors include day-trippers and holiday makers staying overnight in rental properties or camping.[5]

In a 2005 opinion poll of Radio Times readers, Lundy was named as Britain's tenth greatest natural wonder.[6] The island has been designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest[7] and it was England's first statutory Marine Nature reserve, and the first Marine Conservation Zone,[8] because of its unique flora and fauna.[9] It is managed by the Landmark Trust on behalf of the National Trust.[10]

Etymology

[edit]

The place-name Lundy is first attested in 1189 in the Records of the Templars in England, where it appears as [Insula de] Lundeia. It appears in the Charter Rolls as Lundeia again in 1199, and as Lunday in 1281. The name is Scandinavian and means 'puffin island', from the Old Norse lundi meaning 'puffin' (compare the three Lundey islands in Iceland); it appears in the 12th-century Orkneyinga saga as Lundey.[11]

Lundy is known in Welsh as Ynys Wair, 'Gwair's Island', in reference to an alternative name for the wizard Gwydion.[12][13]

History

[edit]Lundy has evidence of visitation or occupation from the Mesolithic period onward, with Neolithic flintwork, Bronze Age burial mounds, four inscribed gravestones from the early medieval period,[14][15] and an early medieval monastery (possibly dedicated to St Elen or St Helen).

Beacon Hill Cemetery

[edit]

Beacon Hill Cemetery was excavated by Charles Thomas in 1969.[16] The cemetery contains four inscribed stones, dated to the 5th or 6th century AD.[17] The site was originally enclosed by a curvilinear bank and ditch, which is still visible in the southwest corner, however, the other walls were moved when the Old Light was constructed in 1819.[18] Celtic Christian enclosures of this type were common in Western Britain and are known as Llans in Welsh and Lanns in Cornish. There are surviving examples in Luxulyan, in Cornwall; Mathry, Meidrim and Clydau in the south of Wales; and Stowford, Jacobstowe, Lydford and Instow, in Devon.[citation needed]

Thomas proposed the following sequence of site usage:[19]

- An area of round huts and fields. These huts may have fallen into disuse before the construction of the cemetery.

- The construction of the focal grave, an 11 by 8 ft (3.4 by 2.4 m) rectangular stone enclosure containing a single cist grave. The interior of the enclosure was filled with small granite pieces. Two more cist graves located to the west of the enclosure may also date from this time.

- Perhaps 100 years later, the focal grave was opened and the infill removed. The body may have been moved to a church at this time.

- Two further stages of cist grave construction around the focal grave.

Twenty-three cist graves were found during this excavation. Considering that the excavation only uncovered a small area of the cemetery, there may be as many as 100 graves.

Inscribed stones

[edit]

Four Celtic inscribed stones have been found in Beacon Hill Cemetery:

- 1400 OPTIMI,[16] or TIMI;[20] the name (or perhaps epithet) Optimus is Latin and male. Discovered in 1962 by D. B. Hague.[21]

- 1401 RESTEVTAE,[16] or RESGEVT[A],[20] Latin, female i.e. Resteuta or Resgeuta. Discovered in 1962 by D. B. Hague.[21]

- 1402 POTIT[I],[16] or [PO]TIT,[20] Latin, male. Discovered in 1961 by K. S. Gardener and A. Langham.[21]

- 1403 --]IGERNI [FIL]I TIGERNI,[16] or—I]GERNI [FILI] [T]I[G]ERNI,[20] Brittonic, male i.e. Tigernus son of Tigernus. Discovered in 1905.[21]

Knights Templar

[edit]Lundy was granted to the Knights Templar by Henry II in 1160. The Templars were a major international maritime force at this time, with interests in North Devon, and almost certainly an important port at Bideford or on the River Taw in Barnstaple. This was probably because of the increasing threat posed by the Norse sea raiders; however, it is unclear whether they ever took possession of the island. Ownership was disputed by the Marisco family who may have already been on the island during King Stephen's reign. The Mariscos were fined, and the island was cut off from necessary supplies.[22] Evidence of the Templars' weak hold on the island came when King John, on his accession in 1199, confirmed the earlier grant.[23]

Marisco family

[edit]

In 1235, William de Marisco was implicated in the murder of Henry Clement, a messenger of Henry III.[24] Three years later, an attempt was made to kill Henry III by a man who later confessed to being an agent of the Marisco family. William de Marisco fled to Lundy where he lived as a virtual king. He built a stronghold in the area now known as Bulls' Paradise with walls 9 feet (3 metres) thick.[23]

In 1242, Henry III sent troops to the island. They scaled the island's cliff and captured William de Marisco and 16 of his "subjects". Henry III built the castle (sometimes referred to as the Marisco Castle) in an attempt to establish the rule of law on the island and its surrounding waters.[25] In 1275, the island is recorded as being in the Lordship of King Edward I[26] but by 1322 it was in the possession of Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster and was among the large number of lands seized by Edward II following Lancaster's execution for rebelling against the King.[27] At some point in the 13th century the monks of the Cistercian order at Cleeve Abbey in Somerset held the rectory of the island.[28]

Piracy

[edit]Over the next few centuries, the island was hard to govern. Trouble followed as both English and foreign pirates and privateers – including other members of the Marisco family – took control of the island for short periods. Ships were forced to navigate close to Lundy because of the dangerous shingle banks in the fast flowing River Severn and Bristol Channel, with its tidal range of 27 feet (8.2 metres),[29][30] one of the greatest in the world.[31][32] This made the island a profitable location from which to prey on passing Bristol-bound merchant ships bringing back valuable goods from overseas.[33]

In 1627, a group known as the Salé Rovers, from the Republic of Salé (now Salé in Morocco) occupied Lundy for five years. These Barbary pirates, under the command of a Dutch renegade named Jan Janszoon, flew a Moorish flag over the island. Slaving raids were made embarking from Lundy by the Barbary Pirates, and captured Europeans were held on Lundy before being sent to Salé and Algiers to be sold as slaves as part of the Barbary coast slave trade.[34][35][36][37]

From 1628 to 1634, in addition to the Barbary Pirates, the island was plagued by privateers of French, Basque, English and Spanish origin targeting the lucrative shipping routes passing through the Bristol Channel. These incursions were eventually ended by John Penington, but in the 1660s and as late as the 1700s the island still fell prey to French privateers.[38]

Civil war

[edit]In the English Civil War, Thomas Bushell held Lundy for King Charles I, rebuilding Marisco Castle and garrisoning the island at his own expense. He was a friend of Francis Bacon, a strong supporter of the Royalist cause and an expert on mining and coining. It was the last Royalist territory held between the first and second civil wars. After receiving permission from Charles I, Bushell surrendered the island on 24 February 1647 to Richard Fiennes, representing General Fairfax.[39] In 1656, the island was acquired by Lord Saye and Sele.[40]

18th and 19th centuries

[edit]The late 18th and early 19th centuries were years of lawlessness on Lundy, particularly during the ownership of Thomas Benson (1708–1772), a Member of Parliament for Barnstaple in 1747 and Sheriff of Devon, who notoriously used the island for housing convicts whom he was supposed to be deporting. Benson leased Lundy from its owner, John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower (1694–1754) (who was an heir of the Grenville family of Bideford and of Stowe, Kilkhampton in Cornwall), at a rent of £60 per annum and contracted with the Government to transport a shipload of convicts to Virginia, but diverted the ship to Lundy to use the convicts as his personal slaves. Later Benson was involved in an insurance swindle. He purchased and insured the ship Nightingale and loaded it with a valuable cargo of pewter and linen. Having cleared the port on the mainland, the ship put into Lundy, where the cargo was removed and stored in a cave built by the convicts, before setting sail again. Some days afterwards, when a homeward-bound vessel was sighted, the Nightingale was set on fire and scuttled. The crew were taken off the stricken ship by the other ship, which landed them safely at Clovelly.[41]

Sir Vere Hunt, 1st Baronet of Curragh, a rather eccentric Irish politician and landowner, and unsuccessful man of business, purchased the island from John Cleveland in 1802 for £5,270. Hunt planted in the island a small, self-contained Irish colony with its own constitution and divorce laws, coinage, and stamps. The tenants came from Hunt's Irish estate and they experienced agricultural difficulties while on the island. This led Hunt to seek someone who would take the island off his hands, failing in his attempt to sell the island to the British government as a base for troops.

After the 1st Baronet's death his son, Sir Aubrey (Hunt) de Vere, 2nd Baronet, also had great difficulty in securing any profit from the property. In the 1820s, John Benison agreed to purchase the island for £4,500 but then refused to complete the sale, as he felt that de Vere could not make out a good title in respect of the sale terms, namely that the island was free from tithes and taxes.[42]

William Hudson Heaven purchased Lundy in 1834, as a summer retreat and for hunting, at a cost of 9,400 guineas (£9,870). He claimed it to be a "free island", and successfully resisted the jurisdiction of the mainland magistrates. Lundy was in consequence sometimes referred to as "the kingdom of Heaven". It belonged in law to the county of Devon, and had long been part of the hundred of Braunton.[40] Many of the buildings on the island, including St. Helen's Church, designed by the architect John Norton, and Millcombe House (originally known simply as "the Villa"), date from the Heaven period. The Georgian-style villa was built in 1836.[43] However, the expense of building the road from the beach (no financial assistance being provided by Trinity House, despite their frequent use of the road following the construction of the lighthouses), maintaining the villa, and the general cost of running the island had a ruinous effect on the family's finances, which had been diminished by reduced profits from their sugar plantations, rum production, and livestock rearing in Jamaica.[44]

In 1957, a message in a bottle from one of the seamen of HMS Caledonia was washed ashore between Babbacombe and Peppercombe in Devon. The letter, dated 15 August 1843, read: "Dear Brother, Please e God i be with y against Michaelmas. Prepare y search Lundy for y Jenny ivories. Adiue William, Odessa". The bottle and letter are on display at the Portledge Hotel at Fairy Cross, in Devon, England. Jenny was a three-masted full-rigged ship reputed to be carrying ivory and gold dust that was wrecked on Lundy on 20 January 1797 at a place thereafter called Jenny's Cove. Some ivory was apparently recovered some years later but the leather bags supposed to contain gold dust were never found.[45][46]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]William Heaven was succeeded by his son the Reverend Hudson Grosset Heaven who, thanks to a legacy from Sarah Langworthy (née Heaven), was able to fulfill his life's ambition of building a stone church on the island. St Helen's was completed in 1896, and stands today as a lasting memorial to the Heaven period. It has been designated by English Heritage a Grade II listed building.[47] He is said to have been able to afford either a church or a new harbour. His choice of the church was not however in the best financial interests of the island. The unavailability of the money for re-establishing the family's financial soundness, coupled with disastrous investment and speculation in the early 20th century, caused severe financial hardship.[48]

Hudson Heaven died in 1916, and was succeeded by his nephew, Walter Charles Hudson Heaven.[49] With the outbreak of the First World War, matters deteriorated seriously, and in 1918 the family sold Lundy to Augustus Langham Christie. In 1924, the Christie family sold the island along with the mail contract and the MV Lerina to the businessman Martin Coles Harman. Harman issued two coins of Half Puffin and One Puffin denominations in 1929, nominally equivalent to the British halfpenny and penny, resulting in his prosecution under the United Kingdom's Coinage Act of 1870. His case was heard by Devon magistrates in April 1930, and he was fined £5 and ordered to pay £15 15 shillings (£15.75 in decimal currency) costs.[50] He appealed to the King's Bench Division of the High Court of Justice in 1931, but the appeal was dismissed.[51] The coins were withdrawn and became collector's items. In 1965, a "fantasy" restrike four-coin set, a few in gold, was issued to commemorate 40 years since Harman purchased the island.[52] Harman's son, John Pennington Harman was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross during the Battle of Kohima, India in 1944.[53] There is a memorial to him at the VC Quarry on Lundy.[54] Martin Coles Harman died in 1954.[55]

Residents did not pay taxes to the United Kingdom and had to pass through customs when they travelled to and from Lundy Island.[56] Although the island was ruled as a virtual fiefdom, its owner never claimed to be independent of the United Kingdom, in contrast to later territorial "micronations".

Following the death of Harman's son Albion in 1968,[57] Lundy was put up for sale in 1969. Jack Hayward, a British millionaire, purchased the island for £150,000 (£3,118,000 today) and gave it to the National Trust,[52] who leased it to the Landmark Trust. The Trust has managed the island since then, deriving its income from arranging day trips, letting out holiday cottages and from donations. In May 2015 a sculpture by Antony Gormley was erected on Lundy. It is one of five life-sized sculptures, Land, placed near the centre and at four compass points of the UK in a commission by the Landmark Trust, to celebrate its 50th anniversary. The others are at Lowsonford (Warwickshire), Saddell Bay (Scotland), the Martello Tower (Aldeburgh, Suffolk), and Clavell Tower (Kimmeridge Bay, Dorset).[58][59]

The island is visited by over 20,000 day trippers a year, but during September 2007 had to be closed for several weeks owing to an outbreak of norovirus.[60]

An inaugural Lundy Island half-marathon took place on 8 July 2018 with 267 competitors.[61]

Wrecked ships and aircraft

[edit]Wreck of Jenny

[edit]Near the end of a voyage from Africa to Bristol, the British merchant ship Jenny was wrecked on the coast of Lundy on 20 January 1797.[62] Only the first mate survived.[63] The site of the tragedy (51°10.87′N 4°40.48′W / 51.18117°N 4.67467°W) has since been known as Jenny's Cove.[64]

Wreck of Battleship Montagu

[edit]

Steaming in heavy fog, the Royal Navy battleship HMS Montagu ran hard aground near Shutter Rock on Lundy's southwest corner at about 2:00 a.m. on 30 May 1906.[65] Thinking they were aground at Hartland Point on the English mainland, a landing party went ashore for help, only finding out where they were after encountering the lighthouse keeper at the island's north light.[66]

Strenuous efforts by the Royal Navy to salvage the badly damaged battleship during the summer of 1906 failed, and in 1907 it was decided to give up and sell her for scrap.[67] Montagu was scrapped at the scene over the next fifteen years. Diving clubs still visit the site, where armour plating remains among the rocks and kelp.[68]

Remains of a German Heinkel 111H bomber

[edit]

During the Second World War two German Heinkel He 111 bombers crash landed on the island in 1941. The first was on 3 March, when all the crew survived and were taken prisoner.[69]

The second was on 1 April when the pilot was killed and the other crew members were taken prisoner.[70] This plane had bombed a British ship and one engine was damaged by anti aircraft fire, forcing it to crash land. Most of the metal was salvaged, although a few remains can be found at the crash site to date. Reportedly, to avoid reprisals, the crew concocted the story that they were on a reconnaissance mission.[71]

Geography

[edit]

The island of Lundy is 3 miles (5 km) long from north to south by a little over 5⁄8 mile (1 kilometre) wide, with an area of 1,100 acres (450 hectares).[1][2] The highest point on Lundy is Beacon Hill, 469 feet (143 metres) above sea level.[72] A few yards off the northeastern coast is Seal's Rock which is so called after the seals which rest on and inhabit the islet.[73][74] It is less than 55 yards (50 metres) wide.[74] Near the jetty is a small pocket beach. One of the Meteorological Office's 31 sea areas announced on the BBC Radio 4 shipping forecast is named Lundy.[75][76]

Geology

[edit]The island is primarily composed of granite of 59.8 ± 0.4 – 58.4 ± 0.4 million years[77] (from the Palaeocene epoch), with slate at the southern end; the plateau soil is mainly loam, with some peat.[7][78] Among the igneous dykes cutting the granite are a small number composed of a unique orthophyre. This was given the name Lundyite in 1914, although the term – never precisely defined – has since fallen into disuse.[77][79][full citation needed] It is possible, based on emplacement of magmas of the basalt, trachyte and rhyolite types at a high levels in Earth's crust, that a volcano system existed above Lundy.[80]

Climate

[edit]Lundy lies on the line where the North Atlantic Ocean and the Bristol Channel meet, so it has quite a mild climate. The island has cool, wet winters and mild, wet summers. It is often windy and fog is frequently experienced.[81] The record high temperature is 29.5 °C (85.1 °F) on 2 August 1990,[82] and the record low temperature is −5.5 °C (22.1 °F) recorded just six months later on 8 February 1991.[82] Lundy is in the USDA 9a plant hardiness zone.[83]

| Climate data for Lundy (1973–1994) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

29.5 (85.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

13.5 (56.3) |

11.1 (52.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.6 (49.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.8 (51.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

6.3 (43.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.7 (49.4) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.1 (34.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.0 (23.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

3.2 (37.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

| Average rainy days | 19.2 | 14.5 | 17.4 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 13.2 | 13.1 | 16.5 | 18.5 | 18.8 | 19.5 | 189.4 |

| Average snowy days | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.4 | 85.6 | 86.1 | 85.6 | 83.4 | 84.9 | 84.9 | 80.2 | 82.5 | 81.7 | 82.0 | 80.3 | 83.5 |

| Source 1: En.tutiempo[84] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Starlings Roost Weather[85] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]Flora

[edit]

The vegetation on the plateau is mainly dry heath, with an area of waved Calluna heath; the northern end of the island is largely bare rock.[86] This area is also rich in lichens, such as Teloschistes flavicans and several species of Cladonia and Parmelia.[87]

Other areas are either a dry heath/acidic grassland mosaic, characterised by heaths and western gorse (Ulex gallii), or semi-improved acidic grassland in which Yorkshire fog (Holcus lanatus) is abundant. Tussocky (Thrift) (Holcus/Armeria) communities occur mainly on the western side, and some patches of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) on the eastern side.[7]

There is one endemic plant species, the Lundy cabbage (Coincya wrightii), a species of primitive brassica.[88]

By the 1980s, the eastern side of the island had become overgrown by rhododendrons (Rhododendron ponticum) which had spread from a few specimens planted in the garden of Millcombe House in Victorian times, but in recent years significant efforts have been made to eradicate this non-native plant.[89]

Fauna

[edit]Terrestrial invertebrates

[edit]Two invertebrate taxa are endemic to Lundy, with both feeding on the endemic Lundy cabbage (Coincya wrightii). These are the Lundy cabbage flea beetle (Psylliodes luridipennis), a species of leaf beetle (family Chrysomelidae) and the Lundy cabbage weevil (Ceutorhynchus contractus var. pallipes), a variety of true weevil (family Curculionidae).[90][91] In addition, the Lundy cabbage is the main host of a flightless form of Psylliodes napi (another species of flea beetle) and a wide variety of other invertebrate species which are not endemic to the island.[91] Another resident invertebrate of note is Atypus affinis, the only British species of purseweb spider.[90][92]

Birds

[edit]The population of puffins (Fratercula arctica) on the island declined in the late 20th and early 21st centuries as a consequence of depredations by brown and black rats (Rattus rattus) and possibly also as a result of commercial fishing for sand eels, the puffins' principal prey. Since the elimination of rats in 2006, seabird numbers have increased. By 2023 the number of puffins had risen to 1,355 and the number of Manx shearwater to 25,000, representing 95% of England's breeding population of this seabird. The island has since 2014 become colonised by European storm petrel.[93]

As an isolated island on major migration routes, Lundy has a rich bird life and is a popular site for birdwatching. Large numbers of black-legged kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) nest on the cliffs, as do razorbill (Alca torda), common guillemot (Uria aalge), European herring gull (Larus argentatus), lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus), northern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis), European shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis), Eurasian oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus), Eurasian skylark (Alauda arvensis), meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis), common blackbird (Turdus merula), European robin (Erithacus rubecula), and linnet (Carduelis cannabina). There are also smaller populations of peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) and raven (Corvus corax).[94][95]

Lundy has attracted many vagrant birds, in particular species from North America. As of 2007, the island's bird list totals 317 species.[96] This has included the following species, each of which represents the sole British record: Ancient murrelet, eastern phoebe, and eastern towhee. Records of bimaculated lark, American robin, and common yellowthroat were also firsts for Britain (American robin has also occurred two further times on Lundy).[96] Veerys in 1987 and 1997 were Britain's second and fourth records, a Rüppell's warbler in 1979 was Britain's second, an eastern Bonelli's warbler in 2004 was Britain's fourth, and a black-faced bunting in 2001 Britain's third.[96]

Other British Birds rarities that have been sighted (single records unless otherwise indicated) are: little bittern; gyrfalcon (3 records); little and Baillon's crakes; collared pratincole; semipalmated (5 records), least (2 records), white-rumped, and Baird's (2 records) sandpipers; Wilson's phalarope; laughing gull; bridled tern; Pallas's sandgrouse; great spotted, black-billed, and yellow-billed (3 records) cuckoos; European roller; olive-backed pipit; citrine wagtail; Alpine accentor; thrush nightingale; red-flanked bluetail; western black-eared (2 records) and desert wheatears; White's, Swainson's (3 records), and grey-cheeked (2 records) thrushes; Sardinian (2 records), Arctic (3 records), Radde's, and western Bonelli's warblers; Isabelline and lesser grey shrikes; red-eyed vireo (7 records); two-barred crossbill; yellow-rumped and blackpoll warblers; yellow-breasted (2 records) and black-headed buntings (3 records); rose-breasted grosbeak (2 records); bobolink; and Baltimore oriole (2 records).[96]

Mammals

[edit]

Lundy is home to an unusual range of introduced mammals, including a distinct breed of wild pony, the Lundy pony, as well as Soay sheep (Ovis aries), sika deer (Cervus nippon), feral goats (Capra aegagrus hircus), and European rabbit, some of which are melanistic.[97]

Other mammals which have made the island their home include the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) and the Eurasian pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus). Until their elimination in 2006, in order to protect the nesting seabirds, Lundy was one of the few places in the UK where the black rat (Rattus rattus) could be found regularly.[98]

Marine habitat

[edit]In 1971, a proposal was made by the Lundy Field Society to establish a marine reserve, and the survey was led by Dr Keith Hiscock, supported by a team of students from Bangor University. Provision for the establishment of statutory Marine Nature Reserves was included in the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, and on 21 November 1986 the Secretary of State for the Environment announced the designation of a statutory reserve at Lundy.[99]

There is an outstanding variety of marine habitats and wildlife, and a large number of rare and unusual species in the waters around Lundy, including some species of seaweed, branching sponges, sea fans, and cup corals.[99]

In 2003, the first statutory No Take Zone (NTZ) for marine nature conservation in the UK was set up in the waters to the east of Lundy island.[100] In 2008, this was declared as having been successful in several ways including the increasing size and number of lobsters within the reserve, and potential benefits for other marine wildlife.[101] However, the no take zone has received a mixed reaction from local fishermen.[102]

On 12 January 2010 the island became Britain's first Marine Conservation Zone designated under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009, designed to help to preserve important habitats and species.[9][103][104]

Three species of cetacean are regularly seen from the island; them being the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatrus), common dolphin (Delphinus delphis), and harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena). Other cetacean species that are sighted from Lundy, albeit more rarely, are the minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), Risso's dolphin (Grampus griseus), and long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas). Basking sharks (Cetorhinus maximus), ocean sunfish (Mola mola), and leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) are also seen around Lundy, especially off the more sheltered eastern coast and only during the warmer months. Furthermore, there is a grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) colony consisting of roughly 60 animals that live around the island.[105][106]

Transport

[edit]

To the island

[edit]There are two ways to get to Lundy, depending on the time of year. In the summer months (April to October) visitors are carried on the Landmark Trust's own vessel, MS Oldenburg, which sails from both Bideford and Ilfracombe. Sailings are usually three days a week, on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, with additional sailings on Wednesdays during July and August. The voyage takes on average two hours, depending on ports, tides and weather. The Oldenburg was first registered in Bremen, Germany, in 1958 and has been sailing to Lundy since being bought by the Lundy Company Ltd in 1985.[107] In the winter months (November to March) the island is served by a scheduled helicopter service from Hartland Point. The helicopter operates on Mondays and Fridays.[108] A grass runway of 435 by 30 yd (398 by 27 m) is available, allowing access to small STOL aircraft.[109]

On the island

[edit]In 2007, Derek Green, Lundy's general manager, launched an appeal to raise £250,000 to save the 1-mile-long (1.5-kilometre) Beach Road, which had been damaged by heavy rain and high seas. The road was built in the first half of the 19th century to provide people and goods with safe access to the top of the island, 120 m (394 ft) above the only jetty.[110] The fund-raising was completed on 10 March 2009.[111]

Lighthouses

[edit]The island has a pair of active lights built in 1897, and an older lighthouse no longer in service.[112][113]

Flags

[edit] | |

| Adopted | 15 May 2010 |

|---|---|

| Design | A white L on the hoist on a blue background |

A number of flags have been used to represent Lundy. Since 2010, the Landmark Trust management has flown a 1954 flag to represent Lundy, being a white capital L on the hoist of a blue field.

History

[edit]-

The first flag, introduced in 1932

-

The Puffin Flag, introduced in the 1930s–40s

-

The flag of Iceland, which was flown on the island from the end of World War Two in 1945

-

The current flag of Lundy, used 1954–1969 and 2010–present

-

The flag of England, which was flown by the Landmark Trust administration from 1969 (when it gained control over the island) until 2010

The first flag of Lundy was introduced in 1932 by Martin Coles Harman, as part of his assertion that the island was "a self-governing dominion of the British Empire".[114][115] The flag was a simple red capital L on a white field with a blue border.[114]

The single flag would eventually rot, and a new one would be made by Harman at least before 1945.[114] The new flag displayed a puffin on a white background with an outer blue and inner red border, and was named the 'Puffin Flag'.[114]

That flag, too, would rot, and Harman would fly the flag of Iceland from the end of World War Two.[114] Tony Langham, who wrote a number of books on the topic of Lundy,[116] wrote in 1989 that he believed Harman's son, John Pennington Harman, who died in the war in 1944,[53] may have been gifted the flag as a "keen flag flyer".[114]

In 1954, a new flag design was produced which displayed a white capital L on the hoist of a blue field.[114]

In 1969, after the death of Albion Harman, the island ended up in the management of the Landmark Trust, which opted to instead fly the flag of England.[114] However, in 2010, the trust restored the 1954 flag.[117]

Naval ensign

[edit] | |

| Adopted | June 2000 |

|---|---|

| Design | A puffin on a white circle on a red field |

The MS Oldbenburg has flown an ensign displaying a puffin on a white circle on a red background since June 2000.[118]

Electricity supply

[edit]There is a small power station comprising three Cummins B and C series diesel engines, offering an approximately 150 kVA 3-phase supply to most of the island buildings. Waste heat from the engine jackets is used for a district heating pipe. There are also plans to collect the waste heat from the engine exhaust heat gases to feed into the district heat network to improve the efficiency further.[119] The power is normally switched off between 00:00 and 06:30.[120]

Administration

[edit]The island is an unparished area of Torridge district in the county of Devon.[121] It forms part of the ward of Clovelly Bay.[122][123] It is part of the constituency electing the Member of Parliament for Torridge and Tavistock and was from 1999 to 2020 part of the South West England constituency for the European Parliament.[123]

In 2013, the island became a separate Church of England ecclesiastical parish.[124]

Stamps

[edit]Owing to a decline in population and lack of interest in the mail contract, the GPO ended its presence on Lundy at the end of 1927.[125] For the next two years Harman handled the mail to and from the island without charge.

On 1 November 1929, he decided to offset the expense by issuing two postage stamps (1⁄2 puffin in pink and 1 puffin in blue). One puffin is equivalent to one English penny. The printing of Puffin stamps continues to this day and they are available at face value from the Lundy Post Office. One used to have to stick Lundy stamps on the back of the envelope; but from 1962 Royal Mail allowed their use on the front of the envelope, but placed on the left side, with the right side reserved for the Royal Mail postage stamp or stamps. Lundy stamps are cancelled by a circular Lundy hand stamp. In 1974, the face value of the Lundy Island stamps was increased to include Royal Mail charges in addition to the charge for transporting mail to the mainland and so from that year it has not been necessary to affix a separate Royal Mail postage stamp.[126]

Lundy stamps are a type of postage stamp known to philatelists as "local carriage labels" or "local stamps". Issues of increasing value were made over the years, including air mail, featuring a variety of subjects. The market value of the early issues has risen substantially over the years. For the many thousands of annual visitors Lundy stamps have become part of the collection of the many British Local Posts collectors. The first catalogues of these stamps included Gerald Rosen's 1970 Catalogue of British Local Stamps. Later specialist catalogues include Stamps of Lundy Island by Stanley Newman, first published in 1984, Phillips Modern British Locals CD Catalogue, published since 2003, and Labbe's Specialised Guide to Lundy Island Stamps, published since 2005 and now in its 11th Edition. Labbe's Guide is considered the gold standard of Lundy catalogues owing to its extensive approach to varieties, errors, specialised items, and "fantasy" issues.[127]

There is a comprehensive collection of these stamps in the Chinchen Collection, donated by Barry Chinchen[128] to the British Library Philatelic Collections in 1977 and now held by the British Library. This is also the home of the Landmark Trust Lundy Island Philatelic Archive which includes artwork, texts and essays as well as postmarking devices and issued stamps.[129]

See also

[edit]- Barbara Whitaker, former warden

- Coins of Lundy

- Puffin Island

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Lundy". Devonbirds. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Geographic Areas: Torridge parishes". Devon.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Marine conservation zone 2013 designation: Lundy". Government UK. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Joint Nature Conservation Committee and Natural England. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ Collyer, Peter (1998) Rain Later, Good: illustrating the Shipping Forecast. Bradford on Avon: Thomas Reed ISBN 0-901281-33-6

- ^ "Lundy Island". Visit North Devon & Exmoor. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Caves win 'natural wonder' vote". BBC. 2 August 2005. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Lundy SSSI citation sheet" (PDF). Natural England. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ "Lundy Marine Conservation Zone". Natural England. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Lundy Marine Conservation Zone". Lundy Marine Conservation Zone. Archived from the original on 29 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Stratton, Mark (18 September 2023). "The tiny British island still stuck in a wonderful, bygone era". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Eilert Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names, p.307.

- ^ Bromwich, Rachel (15 November 2014). Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain. University of Wales Press. p. 147. ISBN 9781783161461.

- ^ Monaghan, Patricia (14 May 2014). The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase. p. 477. ISBN 9781438110370.

- ^ See the discussion and bibliography in Elisabeth Okasha, Corpus of early Christian inscribed stones of South-west Britain (Leicester: University Press, 1993), pp. 154–66.

- ^ Lundy Field Society 40th Annual Report for 1989. pp. 34–47.

- ^ a b c d e Charles Thomas, And Shall These Mute Stones Speak? (1994) Cardiff: University of Wales Press

- ^ "CISP - Site: Beacon Hill, Lundy". UCL.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Historic England. "Chapel remains, cemetery and prehistoric settlement on Beacon Hill, Lundy (1016040)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "CISP - Site: Beacon Hill, Lundy". UCL.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Elisabeth Okasha, (1993) Corpus of Early Christian Inscribed Stones of South-west Britain. Leicester: University Press

- ^ a b c d "Celtic Inscribed Stones Project history". Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ "Lundy Island Pirates — William de Marisco". FairyJo. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ a b Robson, Pete (2012). "History". LundyPete.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018.

- ^ Maitland, F. W. (April 1895). "The Murder of Henry Clement". The English Historical Review. 10 (38): 294–297. doi:10.1093/ehr/X.XXXVIII.294. JSTOR 547790.

- ^ Historic England. "Marisco Castle, Keep and Bailey (1104957)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ Calendarium Inquisitionum Post Mortem Edward I, Anno. 3 (1275), entry 54, p.56, https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/records/item/27355-redirection

- ^ Inquisitions Post Mortem Edward II, (1322), No. 49, p.307, https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/records/item/27355-redirection

- ^ Harrison, Stuart A. (2000). Cleeve Abbey. English Heritage. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-85074-760-4.

- ^ Sailing Directions for the West Coast of England from the Scilly Islands to the Mull of Galloway, including the Isle of Man. London: Admiralty Hydrographic Department. 1891. p. 54.

- ^ "Tides and Currents". Lundy Marine Protection Zone. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Severn Estuary Barrage". UK Environment Agency. 31 May 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ "Coast: Bristol Channel". BBC. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ "Pirate Island". Rodney Broome. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ Milton, Giles (2005). White Gold: The Forgotten Story of North Africa's One Million European Slaves. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0340895092.

- ^ de Bruxelles, Simon (28 February 2007). "Pirates who got away with it by sailing closer to the wind". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007.

The pirates ceased to be a problem after the French conquered their raiding base, Algiers, in 1830 — and the secret of their crucial advantage was lost. ... Barbary pirates raided villages along the Devon and Cornwall coast, setting up a base on Lundy Island .... Those taken were sold in Algiers slave markets or worked to death as galley slaves.

- ^ Konstam, Angus (2008). Piracy: The Complete History. Osprey Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-84603-240-0.

- ^ Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 561. ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7.

- ^ Chanter, John Roberts (1877). Lundy Island: A Monograph, Descriptive and Historical. Cassell, Petter & Galpin. pp. 78–89.

- ^ Boundy, Wyndham Sydney (1961). Bushell and Harman of Lundy. Bideford: Gazette Printing Service.

- ^ a b "Lundy Community Page". Devon County Libraries. Archived from the original on 8 September 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ "Lundy, the Mariscos and Benson". Lerwill-Life.org.uk. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ "Limerick City Archives, P22, De Vere Papers". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ Historic England. "Millcombe House (1326626)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ Gambrill, Anthony (26 May 2019). "Kingdom of Heaven". The Gleaner. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ Page, John Lloyd Warden (1895). The Coasts of Devon and Lundy Island: Their Towns, Villages, Scenery, Antiquities and Legends. London: Horace Cox. p. 227.

- ^ Langham, A. F. (1994). The Island of Lundy. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-7509-0661-6.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Helen (1104955)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ Heaven, Will (5 November 2011). "Lundy: My family and the Kingdom of Heaven". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ "Lundy Island". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 24 January 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ "Lundy Island Coinage". The Times. 17 April 1930. p. 16.

- ^ "High Court of Justice". The Times. 14 January 1931. p. 5.

- ^ a b Bruce, Colin R. (1988). Unusual World Coins (2nd ed.). KP Books. ISBN 978-0-87341-116-5.

- ^ a b "No. 36574". The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 June 1944. p. 2961.

- ^ "MNA100302 | National Trust Heritage Records". heritagerecords.nationaltrust.org.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "'King of Lundy Island' Is Dead at 69". The New York Times. 7 December 1954. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Fogle, Ben (2007). Offshore: In Search of an Island of My Own. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141930435.

- ^ "Island owner dies after air lift" (source unknown). 24 June 1968

- ^ "Land – An art installation for all to mark Landmark's 50th year". Landmark Trust. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ "Sir Antony Gormley sculptures placed at five UK beauty spots". BBC. 12 May 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ de Bruxelles, Simon (21 September 2007). "Island closes down after stomach bug". Times Online. London. Archived from the original on 16 May 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ "The Lundy Island Race – Sunday 8th July 2018". Pure Trail Running. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ "The Marine List". Lloyd's List (2893). Westmead, Hampshire: Gregg International Publishers: 1. 1969 [27 January 1797] – via HathiTrust.

- ^ "Report of the wrecking of the Jenny". The Bath Journal. 30 January 1797. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ "Jenny's Cove". The North Devon Herald. 17 June 1897. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ Burt, R. A. (1988). British Battleships 1889–1904. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 978-0-87021-061-7.

- ^ Coutanche, André. "History 1836–1925 – the Heaven era". The Lundy Field Society. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Shepstone, Harold J. (21 September 1907). "Breaking Up the Ill-fated British Battleship Montagu". Scientific American. 97 (12): 211. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican09211907-211 – via Zenodo.

- ^ Booth, Tony (2007). Admiralty Salvage: In Peace & War 1906–2006. Barnsley, S. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Maritime. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-84415-565-1.

- ^ Lloyd, Howard (21 March 2021). "German bombers crash-landing on Lundy Island provoked angry mob". Devon Live. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Gade, Mary; Michael, Harman (1995). Lundy's War. Appledore: Mary Gade. ISBN 978-0-9525602-0-3.

- ^ "Heinkel He-111 3911 - Lundy". AIRCRAFT WRECKS in the UK & Ireland. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ "Geography Place and People: On the Map". Channel 4. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "LUNDY ISLAND" Archived 9 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine in A Handbook for Travellers in Devonshire (9th ed.), London, J. Murray, (1879).

- ^ a b "Diving". Lundy Field Society. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "Shipping forecast key". Met Office. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "150 years of the Shipping Forecast". BBC Weather. 23 August 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ a b Charles, J. H.; Whitehouse, M. J.; Andersen, J. C. Ø.; Shail, R. K.; Searle, M. P. (4 October 2017). "Age and petrogenesis of the Lundy granite: Paleocene intraplate peraluminous magmatism in the Bristol Channel, UK" (PDF). Journal of the Geological Society. 175 (1): 44–59. Bibcode:2018JGSoc.175...44C. doi:10.1144/jgs2017-023. hdl:10871/29676. S2CID 56117113.

- ^ "Lundy island, virtual tour — geology". Natural England. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ Hall, T. C. F. (1915). "Summer Programme of the Geological Survey". Monographs of the United States Geological Survey. Vol. 53.

- ^ "The Geology of Lundy" (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Climate in Lundy Island, Temperature of Lundy Island, Weather in Lundy Island". TravelTill.com. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Monthly Temperature Extremes". www.roostweather.com/index.php. Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- ^ "Plant Cold Hardiness Zone Map of the British Isles". TreBrown.com. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Lundy Climate Period: 1973-1994". En.tutiempo. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "Monthly Temperature Extremes". Roost Weather. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- ^ Hubbard, Elizabeth (1997). "Botanical studies" (PDF). Lundy Field Society. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Allen, Anne (2008). "Lichen Specialities of Lundy: An Overview" (PDF). Journal of the Lundy Field Society. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "The Lundy Cabbage". Lundy Field Society. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Crompton, Stephen G.; Key, Roger S.; Pratt, Steve (2016). "Progress Towards Eradication of Rhododendrum ponticum on Lundy" (PDF). Journal of the Lundy Field Society. 5. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Lundy island, virtual tour — wildlife". Natural England. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ a b Compton, S. G.; Key, R. S. (2000). "Coincya wrightii (O. E. Schulz) Stace (Rhynchosinapis wrightii (O. E. Schulz) Dandy ex A. R. Clapham)". Journal of Ecology. 88 (3): 535–547. Bibcode:2000JEcol..88..535C. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00477.x.

- ^ "Lundy: A Wildlife Haven". BBC. 15 August 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ "'Shear' success for Lundy's seabirds thanks to decades of conservation effort". Inside Ecology. 12 October 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Lymbery, Philip (21 March 2017). "Plight of the falcon: Why the birds are under threat". inews.co.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Birds". Lundy.org.uk. Lundy Field Society. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Tim; Jones, Tim (2007). The Birds of Lundy. Langman, Mike (ill.). Berrynarbor: Devon Bird Watching & Preservation Society / Lundy Field Society. ISBN 978-0-9540088-7-1.

- ^ Timmermans, Martijn; Elmi, Hanna; Kett, Stephen (2018). "Black rabbits on Lundy: Tudor treasures or post-war phonies?" (PDF). Journal of the Lundy Field Society (6). Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "British Isles Exotic and Introduced Mammals". World of European Exotic and Introduced Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Lundy Island Marine Nature Reserve". Lundy Field Society. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "Protection for Lundy Island's sea life boosted: The First No Take Zone in UK confirmed by Government". Press Release. Natural England. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ "Natural England says it's time to sink or swim to save our seas" (press release). Natural England. Retrieved 28 May 2014 – via Wired-Gov.net.

- ^ "Fishing ban brings seas to life". BBC News. 16 July 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ "Lundy sea is England's first Maritime Conservation Zone". BBC. 12 January 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "Lundy Island becomes England's first marine conservation zone". The Guardian. London. 12 January 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "Marine life". LandmarkTrust.org.uk.

- ^ "Mammals". Lundy.org.uk. Lundy Field Society. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "MS Oldenburg". CaptainsVoyage. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Visiting Lundy". LundyBirdObs.org.uk. Lundy Bird Observatory. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ UK VFR flight guide, 2003 edition, ISBN 1-874783-62-4

- ^ Morris, Steven (5 September 2007). "£250,000 plea to save remote island's lifeline". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ "Lundy road appeal completed". Landmark Trust. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ "Lundy North Lighthouse, Lundy, Devon". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Historic England. "The Old Lighthouse, Lundy (1016039)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h A.F. Langham (1989). "The Flags and Flagpoles of Lundy" (PDF). Lundy Field Society Newsletter. No. 20. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 February 2025. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "History 1925-1969 – the Harman era". Lundy Field Society. Archived from the original on 14 September 2025. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "Books". www.lundy.org.uk. Lundy Field Society. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ "History since 1969 – the Landmark Trust era". Lundy Field Society. Archived from the original on 14 September 2025. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ Coutanche, André. "M.S. Oldenburg flags". Flags Of The World. Retrieved 14 September 2025.

- ^ Green, Derek. "Lundy General Managers Report for 2005" (PDF). Lundy.org.uk. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2016.

- ^ "Lundy Island Before You Depart Guide 2016" (PDF). Landmark Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "North Devon District Council & Torridge District Council Core Strategy DPDs: Evidence Base" (PDF). Community Appraisals and Parish Plans in Torridge. North Devon Council. pp. 15–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ "The District of Torridge (Electoral Changes) Order 1999" (PDF). UK Statutory Instruments. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ a b Ordnance Survey Election Maps

- ^ Saxbee, Helen (20 December 2013). "Lundy island becomes parish". Church Times. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ "Lundy Puffin Postage Stamps". Stamp Collecting Blog. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014. With images of "puffin" stamps.

- ^ "Lundy Postal Service". LandmarkTrust.org.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "The Lundy Changeling?". Lost Post Collectors Society. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Chinchen, Barry N. D. (1969). A Catalogue of Lundy Stamps. Eastleigh, Hampshire: self-published. OCLC 558737398. British Library X.512/621.

- ^ Philatelic Research at the British Library Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine by David Beech

Further reading

[edit]- Powicke, F. M. (1951). "The murder of Henry Clement and the pirates of Lundy Island". Ways of Medieval Life and Thought: Essays and Addresses. Biblo & Tannen. pp. 38−38–68. ISBN 9780819601377.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Sack, John (2000). Report from Practically Nowhere. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-08918-5.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Lundy Marine Reserve at Protect Planet Ocean

- Lundy Isle (1956) from British Pathé at YouTube