Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Celtic Britons

View on Wikipedia

The Britons (*Pritanī, Latin: Britanni, Welsh: Brythoniaid), also known as Celtic Britons[1] or ancient Britons, were the Celtic people[2] who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age until the High Middle Ages, at which point they diverged into the Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons (among others).[2] They spoke Common Brittonic, the ancestor of the modern Brittonic languages.[2]

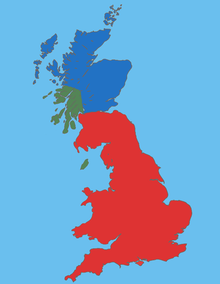

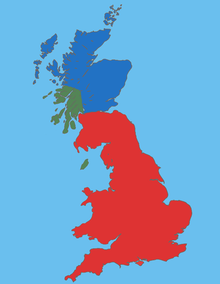

The earliest written evidence for the Britons is from Greco-Roman writers and dates to the Iron Age.[2] Ancient Britain was made up of many tribes and kingdoms, associated with various hillforts. The Britons followed an ancient Celtic religion overseen by druids. Some of the southern tribes had strong links with mainland Europe, especially Gaul and Belgica, and minted their own coins. The Roman Empire conquered most of Britain in the 1st century AD, creating the province of Britannia. The Romans invaded northern Britain, but the Britonnic tribes such as the Caledonians and Picts in the north remained unconquered, and Hadrian's Wall which bisects modern Northumbria and Cumbria became the edge of the empire. A Romano-British culture emerged, mainly in the southeast, and British Latin coexisted with Brittonic.[3] It is unclear what relationship the Britons had with the Picts, who lived outside of the empire in northern Britain; however, most scholars today accept the fact that the Pictish language was closely related to Common Brittonic.[4]

Following the end of Roman rule in Britain during the 5th century, Anglo-Saxon settlement of eastern and southern Britain began. The culture and language of the Britons gradually fragmented, and much of their territory gradually became Anglo-Saxon, while the north and the Isle of Man became subject to a similar settlement by Gaelic-speaking tribes from Ireland who would eventually form Scotland. The extent to which this cultural change was accompanied by wholesale population changes is still debated. During this time, Britons migrated to mainland Europe and established significant colonies in Brittany (now part of France), the Channel Islands,[5] and Britonia (now part of Galicia, Spain).[2] By the 11th century, Brittonic-speaking populations had split into distinct groups: the Welsh in Wales, the Cornish in Cornwall, the Bretons in Brittany, the Cumbrians of the Hen Ogledd ("Old North") in modern southern Scotland and northern England, and the remnants of the Pictish people in northern Scotland.[6] Common Brittonic developed into the distinct Brittonic languages: Welsh, Cumbric, Cornish and Breton.[2]

Name

[edit]In Celtic studies, 'Britons' refers to native speakers of the Brittonic languages in the ancient and medieval periods, "from the first evidence of such speech in the pre-Roman Iron Age, until the central Middle Ages".[2]

The earliest known reference to the inhabitants of Britain was made by Pytheas, a Greek geographer who made a voyage of exploration around the British Isles between 330 and 320 BC. Although none of his writings remain, writers during the following centuries make frequent reference to them. The ancient Greeks called the people of Britain the Pretanoí or Bretanoí.[2] Pliny's Natural History (77 AD) says the older name for the island was Albion,[2] and Avienius calls it insula Albionum, "island of the Albions".[7]The name could have reached Pytheas from the Gauls.[8]

The P-Celtic ethnonym has been reconstructed as *Pritanī, from Common Celtic *kʷritu, which became Old Irish cruth and Old Welsh pryd.[2] This likely means "people of the forms, shapely people", and could be linked to the Latin name Picti (the Picts), which is usually explained as meaning "painted people".[2] The Old Welsh name for the Picts was Prydyn.[9] Linguist Kim McCone suggests the name became restricted to inhabitants of the far north after Cymry displaced it as the name for the Welsh and Cumbrians.[10] The Welsh prydydd, "maker of forms", was also a term for the highest grade of a bard.[2]

The medieval Welsh form of Latin Britanni was Brython (singular and plural).[2] Brython was introduced into English usage by John Rhys in 1884 as a term unambiguously referring to the P-Celtic speakers of Great Britain, to complement Goidel; hence the adjective Brythonic refers to the group of languages.[11] "Brittonic languages" is a more recent coinage (first attested in 1923 according to the Oxford English Dictionary).

In the early Middle Ages, following the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, the Anglo-Saxons called all Britons Bryttas or Wealas (Welsh), while they continued to be called Britanni or Brittones in Medieval Latin.[2] From the 11th century, they are more often referred to separately as the Welsh, Cumbrians, Cornish, and Bretons, as they had separate political histories from then.[2] From the early 16th century, and especially after the Acts of Union 1707, the terms British and Briton could be applied to all inhabitants of the Kingdom of Great Britain, including the English, Scottish, and some Irish, or the subjects of the British Empire generally.[12]

Language

[edit]

The Britons spoke an Insular Celtic language known as Common Brittonic. Brittonic was spoken throughout the island of Britain (in modern terms, England, Wales, and Scotland) and the Isle of Man.[2][a] According to early medieval historical tradition, such as The Dream of Macsen Wledig, the post-Roman Celtic speakers of Armorica were colonists from Britain, resulting in the Breton language, a language related to Welsh and identical to Cornish in the early period, and is still used today. Thus, the area today is called Brittany (Br. Breizh, Fr. Bretagne, derived from Britannia).

Common Brittonic developed from the Insular branch of the Proto-Celtic language that developed in the British Isles after arriving from the continent at some point between the 10th and the 7th century BC. The language eventually began to diverge; some linguists have grouped subsequent developments as Western and Southwestern Brittonic languages. Western Brittonic developed into Welsh in Wales and the Cumbric language in the Hen Ogledd or "Old North" of Britain (modern northern England and southern Scotland), while the Southwestern dialect became Cornish in Cornwall and South West England and Breton in Armorica. Pictish is now generally accepted to descend from Common Brittonic rather than being a separate Celtic language. Welsh and Breton survive today; Cumbric and Pictish became extinct in the 12th century. Cornish had become extinct by the 19th century but has been the subject of language revitalization since the 20th century.[13]

Tribal groups

[edit]

Celtic Britain was made up of many territories controlled by Brittonic tribes. They are generally believed to have dwelt throughout the whole island of Great Britain, at least as far north as the Clyde–Forth isthmus. The territory north of this was largely inhabited by the Picts; little direct evidence has been left of the Pictish language, but place names and Pictish personal names recorded in the later Irish annals suggest it was indeed related to the Common Brittonic language.[14][15][page needed][16][17] Their Goidelic (Gaelic) name, Cruithne, is cognate with Pritenī.

The following is a list of the major Brittonic tribes, in both the Latin and Brittonic languages, as well as their capitals during the Roman period.

Art

[edit]

The La Tène style, which covers British Celtic art, was late arriving in Britain, but after 300 BC the ancient British seem to have had generally similar cultural practices to the Celtic cultures nearest to them on the continent. There are significant differences in artistic styles, and the greatest period of what is known as the "Insular La Tène" style, surviving mostly in metalwork, was in the century or so before the Roman conquest, and perhaps the decades after it.[citation needed]

The carnyx, a trumpet with an animal-headed bell, was used by Celtic Britons during war and ceremony.[18][19]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]There are competing hypotheses for when Celtic peoples, and the Celtic languages, first arrived in Britain, none of which have gained consensus. The traditional view during most of the twentieth century was that Celtic culture grew out of the central European Hallstatt culture, from which the Celts and their languages reached Britain in the first millennium BC.[20][21][page needed] More recently, John Koch and Barry Cunliffe have challenged that with their 'Celtic from the West' theory, which has the Celtic languages developing as a maritime trade language in the Atlantic Bronze Age cultural zone before it spread eastward.[22] Alternatively, Patrick Sims-Williams criticizes both of these hypotheses to propose 'Celtic from the Centre', which suggests Celtic originated in Gaul and spread during the first millennium BC, reaching Britain towards the end of this period.[23]

In 2021, a major archaeogenetics study uncovered a migration into southern Britain during the Bronze Age, over a 500-year period from 1,300 BC to 800 BC.[24][page needed] The migrants were "genetically most similar to ancient individuals from France" and had higher levels of Early European Farmers ancestry.[24][page needed] From 1000 to 875 BC, their genetic marker swiftly spread through southern Britain,[25] making up around half the ancestry of subsequent Iron Age people in this area, but not in northern Britain.[24][page needed] The "evidence suggests that rather than a violent invasion or a single migratory event, the genetic structure of the population changed through sustained contacts between mainland Britain and Europe over several centuries, such as the movement of traders, intermarriage, and small-scale movements of family groups".[25] The authors describe this as a "plausible vector for the spread of early Celtic languages into Britain".[24][page needed] There was much less migration into Britain during the subsequent Iron Age, so it is more likely that Celtic reached Britain before then.[24][page needed] Barry Cunliffe suggests that a branch of Celtic was already being spoken in Britain and that the Bronze Age migration introduced the Brittonic branch.[26]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was originally compiled by the orders of King Alfred the Great in approximately 890, starts with this, incorporated into the Chronicle from Bede's Ecclesiastical History:[27]

Brittene igland is ehta hund mila lang ⁊ twa hun brad ⁊ her sind on þis igland fif geþeode Englisc ⁊ Brittisc ⁊ Wilsc[b] ⁊ Scyttisc ⁊ Pyhtisc ⁊ Bocleden. Erest weron bugend þises landes Brittes þa coman of Armenia.

Roman conquest

[edit]

In 43 AD, the Roman Empire invaded Britain. The British tribes opposed the Roman legions for many decades, but by 84 the Romans had decisively conquered southern Britain and had pushed into Brittonic areas of what would later become northern England and southern Scotland. During the same period, Belgic tribes from the Gallic-Germanic borderlands settled in southern Britain. Caesar asserts the Belgae had first crossed the channel as raiders, only later establishing themselves on the island.[32] In 122 the Romans fortified the northern border with Hadrian's Wall, which spanned what is now Northern England. In 142 Roman forces pushed north again and began construction of the Antonine Wall, which ran between the Forth–Clyde isthmus, but they retreated back to Hadrian's Wall after 20 years. Although the native Britons south of Hadrian's Wall mostly kept their land, they were subject to the Roman governors, whilst the Brittonic-Pictish Britons north of the wall probably remained fully independent and unconquered. The Roman Empire retained control of "Britannia" until its departure about 410, although parts of Britain had effectively shrugged off Roman rule decades earlier.[citation needed]

Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain

[edit]

Fifty years or so after the time of the Roman departure, the Germanic-speaking Anglo-Saxons began a migration to the south-eastern coast of Britain, where they began to establish their own kingdoms, and the Gaelic-speaking Scots migrated from Dál nAraidi (modern Northern Ireland) to the west coast of Scotland and the Isle of Man.[33][page needed][34][page needed] At the same time, Britons established themselves in what is now called Brittany and the Channel Islands. There they set up their own small kingdoms and the Breton language developed from Brittonic Insular Celtic rather than Gaulish or Frankish. A further Brittonic colony, Britonia, was also set up at this time in Gallaecia in northwestern Spain.

Many of the old Brittonic kingdoms began to gradually disappear in the centuries after the Anglo-Saxon and Scottish Gaelic invasions; Parts of the regions of modern East Anglia, East Midlands, North East England, Argyll, and South East England were the first to fall to the Germanic and Gaelic Scots invasions. The kingdom of Ceint (modern Kent) fell in 456 AD. Linnuis (which stood astride modern Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire) was subsumed as early as 500 AD and became the English Kingdom of Lindsey.

Regni (essentially modern Sussex and eastern Hampshire) was likely fully conquered by 510. Ynys Weith (Isle of Wight) fell in 530, Caer Colun (essentially modern Essex) by 540. The Gaels arrived on the northwest coast of Britain from Ireland, dispossessed the native Britons, and founded Dal Riata which encompassed modern Argyll, Skye, and Iona between 500 and 560. Deifr (Deira) which encompassed modern-day Teesside, Wearside, Tyneside, Humberside, Lindisfarne (Medcaut), and the Farne Islands fell to the Anglo-Saxons in 559, and Deira became an Anglo-Saxon kingdom after this point.[35] Caer Went had officially disappeared by 575, becoming the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of East Anglia. Gwent was only partly conquered; its capital Caer Gloui (Gloucester) was taken by the Anglo-Saxons in 577, handing Gloucestershire and Wiltshire to the invaders, while the westernmost part remained in Brittonic hands, and continued to exist in modern Wales.

Caer Lundein, encompassing London, St. Albans and parts of the Home Counties,[36] fell from Brittonic hands by 600, and Bryneich, which existed in modern Northumbria and County Durham with its capital of Din Guardi (modern Bamburgh) and which included Ynys Metcaut (Lindisfarne), had fallen by 605 becoming Anglo-Saxon Bernicia.[37] Caer Celemion (in modern Hampshire and Berkshire) had fallen by 610. Elmet, a large kingdom that covered much of modern Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Cheshire and likely had its capital at modern Leeds, was conquered by the Anglo-Saxons in 627. Pengwern, which covered Staffordshire, Shropshire, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire, was largely destroyed in 656, with only its westernmost parts in modern Wales remaining under the control of the Britons, and it is likely that Cynwidion, which had stretched from modern Bedfordshire to Northamptonshire, fell in the same general period as Pengwern, though a sub-kingdom of Calchwynedd may have clung on in the Chilterns for a time.[38]

Novant, which occupied Galloway and Carrick, was subsumed by fellow Brittonic-Pictish polities by 700. Aeron, which encompassed modern Ayrshire,[39] was conquered by the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria by 700.

Yr Hen Ogledd (the Old North)

[edit]

Some Brittonic kingdoms were able to successfully resist these incursions: Rheged (encompassing much of modern Northumberland and County Durham and areas of southern Scotland and the Scottish Borders) survived well into the 8th century, before the eastern part peacefully joined with the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia–Northumberland by 730, and the west was taken over by the fellow Britons of Ystrad Clud.[40][page needed][41][page needed] Similarly, the kingdom of Gododdin, which appears to have had its court at Din Eidyn (modern Edinburgh) and encompassed parts of modern Northumbria, County Durham, Lothian and Clackmannanshire, endured until approximately 775 before being divided by fellow Brittonic Picts, Gaelic Scots and Anglo-Saxons.

The Kingdom of Cait, covering modern Caithness, Sutherland, Orkney, and Shetland, was conquered by Gaelic Scots in 871. Dumnonia (encompassing Cornwall, Devonshire, and the Isles of Scilly) was partly conquered during the mid 9th century AD, with most of modern Devonshire being annexed by the Anglo-Saxons, but leaving Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly (Enesek Syllan), and for a time part of western Devonshire (including Dartmoor), still in the hands of the Britons, where they became the Brittonic state of Kernow. The Channel Islands (colonised by Britons in the 5th century) came under attack from Norse and Danish Viking attack in the early 9th century, and by the end of that century had been conquered by Viking invaders.

The Kingdom of Ce, which encompassed modern Marr, Banff, Buchan, Fife, and much of Aberdeenshire, disappeared soon after 900. Fortriu, the largest Brittonic-Pictish kingdom which covered Strathearn, Morayshire and Easter Ross, had fallen by approximately 950 to the Gaelic Kingdom of Alba (Scotland). Other Pictish kingdoms such as Circinn (in modern Angus and The Mearns), Fib (modern Fife), Fidach (Inverness and Perthshire), and Ath-Fotla (Atholl), had also all fallen by the beginning of the 11th century or shortly after.

The Brythonic languages in these areas were eventually replaced by the Old English of the Anglo-Saxons, and Scottish Gaelic, although this was likely a gradual process in many areas. Similarly, the Brittonic colony of Britonia in northwestern Spain appears to have disappeared soon after 900. The kingdom of Ystrad Clud (Strathclyde) was a large and powerful Brittonic kingdom of the Hen Ogledd (the 'Old North') which endured until the end of the 11th century, successfully resisting Anglo-Saxon, Gaelic Scots and later also Viking attacks. At its peak it encompassed modern Strathclyde, Dumbartonshire, Cumbria, Stirlingshire, Lanarkshire, Ayrshire, Dumfries and Galloway, Argyll and Bute, and parts of North Yorkshire, the western Pennines, and as far as modern Leeds in West Yorkshire.[41][page needed][42][43][44][f] Thus the Kingdom of Strathclyde became the last of the Brittonic kingdoms of the 'Old North' to fall in the 1090s when it was effectively divided between England and Scotland.[45][46]

Wales, Cornwall and Brittany

[edit]The Britons also retained control of Wales and Kernow (encompassing Cornwall, parts of Devon including Dartmoor, and the Isles of Scilly) until the mid 11th century when Cornwall was effectively annexed by the English, with the Isles of Scilly following a few years later, although at times Cornish lords appear to have retained sporadic control into the early part of the 12th century.

Wales remained free from Anglo-Saxon, Gaelic Scots and Viking control, and was divided among varying Brittonic kingdoms, the foremost being Gwynedd (including Clwyd and Anglesey), Powys, Deheubarth (originally Ceredigion, Seisyllwg and Dyfed), Gwent, and Morgannwg (Glamorgan). These Brittonic-Welsh kingdoms initially included territories further east than the modern borders of Wales; for example, Powys included parts of modern Merseyside, Cheshire and the Wirral and Gwent held parts of modern Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Somerset and Gloucestershire, but had largely been confined to the borders of modern Wales by the beginning of the 12th century.

However, by the early 12th century, the Anglo-Saxons and Gaels had become the dominant cultural force in most of the formerly Brittonic ruled territory in Britain, and the language and culture of the native Britons was thereafter gradually replaced in those regions,[47][failed verification] remaining only in Wales, Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and Brittany, and for a time in parts of Cumbria, Strathclyde, and eastern Galloway. Cornwall (Kernow, Dumnonia) had certainly been largely absorbed by England by the 1050s to early 1100s, although it retained a distinct Brittonic culture and language.[48]. Wales and Brittany remained independent for a considerable time, however, with Brittany united with France in 1532, and Wales united with England by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542 in the mid 16th century during the rule of the Tudors (Y Tuduriaid), who were themselves of Welsh heritage on the male side.

Wales, Cornwall, Brittany and the Isles of Scilly continued to retain a distinct Brittonic culture, identity and language, which they have maintained to the present day. The Welsh and Breton languages remain widely spoken, and the Cornish language, once close to extinction, has experienced a revival since the 20th century. The vast majority of place names and names of geographical features in Wales, Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and Brittany are Brittonic, and Brittonic family and personal names remain common. During the 19th century, many Welsh farmers migrated to Patagonia in Argentina, forming a community called Y Wladfa, which today consists of over 1,500 Welsh speakers.

Eastern England

[edit]Eastern England was populated by Brythonic tribes such as the Iceni, Corieltauvi, and Catuvellauni. In the most common view, the Britons of Eastern England were assimilated by Anglo-Saxons in the first 200 years of invasion, from 450-600 AD, as their kingdoms were conquered. This view is often supported by the lack of Brythonic toponyms in the region, and by various mentions such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 491 AD: "Aelle and Cissa begirt Andredesceaster and slay all who dwell therein, nor was there for that reason one Briton left alive".[49]

Evidence of continuing Brythonic presence in Eastern England can be found in the Life of Saint Guthlac, a biography of the East Anglian hermit who lived in the Fens during the early 8th century. Saint Guthlac was described as attacked on several occasions by people he believed were Britons living in the Fens.[50] The 12th century story Havelok the Dane includes a Saxon king Alsi, of Brittonic origin, who ruled over Lincoln, Lindsey, Rutland and Stamford. In the year 1090 a monk in Ramsey wrote that "the savage and untamable race of the Britons was ravaging far and wide in the province of Huntingdon". This suggests that Britons were still living in the Fens by 11th century and most likely practiced their own style of Christianity, which was considered pagan by local Anglo-Saxons.[50] Another story from Ramsey mentions raids of Britons not far from Royston in the 10th century.[51] In The Memorials of Cambridge we can find a line "If any of the gild slay a man, and he be an avenger by compulsion (neadwraca) and compensate for his violence, and the slain man be a twelfhynde man, let each of the gild give half a mark for his aid: if the slain man be a ceorl, two oras: if he be Welsh (Wylisc) one ora", where "Wylisc" refers to a Briton. We may infer that, though a Welsh servile population existed in Cambridgeshire in the tenth century, it was not so numerous as elsewhere, and that there the Welshman's life was more respected.[50] The legend of Wandlebury, popular in Cambridge, contains several pagan elements, mentioning a town Cantabrica and a tribe of Wandali near Ely, who were "savagely murdering the Christians".[52] The legend was first written in 1211 by Gervase of Tilbury, and can be seen an original Celtic story, originated at the end of the Roman Empire during the raids of Vandals, which later passed to local Anglo-Saxon population.[53]

Oosthuizen (2016) mentions six placenames in the region with the "wealh-" root, which means 'Briton', including Walewrth, Walsoken and Walpole. Other examples of Brythonic toponyms include River Great Ouse, from Proto-Celtic *Udso-s ('water'), River Welland (possibly from "wealh-" root), River Cam (Granta), from Proto-Celtic *kambos ('crooked'), Chettisham (compare Welsh "coed", meaning 'wood'), Chatteris (from the same root), King's Lynn, from Brythonic *llɨnn ('lake').[54][55] Comberton, a parish in South Cambridgeshire, is derived from the root "cymry", that refers to all Britons.[56]

Northern Iberia

[edit]In the late 5th and early 6th centuries AD, a colony called Britonia was established in northern Galicia. The British settlements first appeared at the First Council of Lugo in 569 and later, a separate bishopric was established, with the first Bishop being Maeloc.[57] Despite the exact location of the diocese isn't known, as well as how long did Brythonic culture and language perfromed in the region, several toponyms across Galicia and Asturias containing root bret- or brit- can be still found,[58] including Bretelo in Ourense, Bertoña in A Capela or El Breton in Corvera, Asturias.[59]

Genetics

[edit]Schiffels et al. (2016) examined the remains of three Iron Age Britons buried ca. 100 BC.[60] A female buried in Linton, Cambridgeshire carried the maternal haplogroup H1e, while two males buried in Hinxton both carried the paternal haplogroup R1b1a2a1a2, and the maternal haplogroups K1a1b1b and H1ag1.[61] Their genetic profile was considered typical for Northwest European populations.[60] Though sharing a common Northwestern European origin, the Iron Age individuals were markedly different from later Anglo-Saxon samples, who were closely related to Danes and Dutch people.[62]

Martiniano et al. (2018) examined the remains of a female Iron Age Briton buried at Melton between 210 BC and 40 AD.[63] She was found to be carrying the maternal haplogroup U2e1e.[64] The study also examined seven males buried in Driffield Terrace near York between the 2nd century AD and the 4th century AD during the period of Roman Britain.[63] Six of these individuals were identified as native Britons.[65] The six examined native Britons all carried types of the paternal R1b1a2a1a and carried the maternal haplogroups H6a1a, H1bs, J1c3e2, H2, H6a1b2 and J1b1a1.[64] The indigenous Britons of Roman Britain were genetically closely related to the earlier Iron Age female Briton, and displayed close genetic links to modern Celts of the British Isles, particularly Welsh people, suggesting genetic continuity between Iron Age Britain and Roman Britain, and partial genetic continuity between Roman Britain and modern Britain.[66][65] On the other hand, they were genetically substantially different from the examined Anglo-Saxon individual and modern English populations of the area, suggesting that the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain left a profound genetic impact.[67]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ While there have been attempts in the past to align the Pictish language with non-Celtic language, the current academic view is that it was Brittonic. See: Forsyth 1997, p. 37: "[T]he only acceptable conclusion is that, from the time of our earliest historical sources, there was only one language spoken in Pictland, the most northerly reflex of Brittonic."

- ^ Thorpe's parallel Cott. Tober. B.iv text reads Brytwylsc.[28]

- ^ Swanton notes that MS E says Brittisc ond Wilsc giving six languages and possibly meaning Cornish by Brittisc, whereas MS D says Bryt-Wylsc as one language.[29]

- ^ Swanton notes that this means Latin.[29]

- ^ Swanton's 20th century translation substitutes Armorica directly with a note about the original manuscript.[29] The 19th century translation by Ingram retains the original manuscript error in translation and notes that the Saxon transcriber of the Chronicle misquoted Bede, who wrote Armoricano meaning an area in northwestern Gaul that includes modern Brittany.[30] Thorpe notes the same.[31]

- ^ cf. Bannerman 1999, Chapter 3/"The Scottish takeover of Pictland and the relics of Columba", representing the "traditional" view.

References

[edit]- ^ Webster 1996, p. 623.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Koch 2006, pp. 291–292, Britons.

- ^ Sawyer 1998, pp. 69–74.

- ^ Forsyth 1997, p. 9.

- ^ "The Germanic invasions of Britain". www.uni-due.de.

- ^ Scottish Archaeological Research Framework (ScARF), Highland Framework, Early Medieval (accessed May 2022).

- ^ Snyder, Christopher A. (2008). The Britons. John Wiley & Sons. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-470-75821-2.

- ^ Foster, Robert Fitzroy (2001). The Oxford History of Ireland (reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-280202-6.

- ^ Fraser 2009, p. 48.

- ^ McCone 2013, p. 25.

- ^ "brythonic | Origin and meaning of Brythonic by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Briton". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Why Cornwall is resurrecting its indigenous language". www.bbc.com. 24 April 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Forsyth 2006, p. 1447.

- ^ Forsyth 1997.

- ^ Fraser 2009, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Woolf 2007, pp. 322–340.

- ^ Corbishley et al. 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Hunter, Fraser (of Museum of Scotland), Carnyx and Co- piece by Hunter on the carnyx

- ^ MacAulay 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Karl 2010.

- ^ Cunliffe & Koch 2016, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2020, p. 523.

- ^ a b c d e Patterson, Isakov & Booth 2021.

- ^ a b "Ancient DNA study reveals large scale migrations into Bronze Age Britain". University of York. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Ancient mass migration transformed Britons' DNA". BBC News. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Giles 1887, p. 303.

- ^ a b Thorpe 1861, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Swanton 1998, p. 3.

- ^ Ingram & Giles 1847, p. 103.

- ^ Thorpe 1861, p. 394.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 2.4, 5.2

- ^ Pattison 2008.

- ^ Pattison 2011.

- ^ "Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons - Deira". www.historyfiles.co.uk.

- ^ Nennius (c. 828). History of the Britons. Chapter 6: "Cities of Britain".

- ^ Koch 2006, pp. 515–516, Cumbric.

- ^ Kessler, P. L. "Kingdoms of British Celts - Cynwidion". The History Files. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Bromwich, Foster & Jones 1978, p. 157.

- ^ Chadwick & Chadwick 1940.

- ^ a b Kapelle 1979.

- ^ Broun 1999, "Dunkeld and the origin of Scottish identity".

- ^ Forsyth 2005, pp. 28–32.

- ^ Woolf 2007, "Constantine II".

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 12, 575.

- ^ Clarkson 2014, pp. 12, 63–66, 154–158.

- ^ "Germanic invaders may not have ruled by apartheid". New Scientist, 23 April 2008.

- ^ Williams & Martin 2002, pp. 341–357.

- ^ Hodgkin, Thomas. "The history of England, from the earliest times to the Norman Conquest". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 9 May 2025.

- ^ a b c "Late survival of Celtic population in E. Anglia". www.cantab.net. Retrieved 9 May 2025.

- ^ Chronicon Abbatiae Rameseiensis, p. 140

- ^ Gervase of Tilbury, Otia Imperialia (c.13th century)

- ^ "On The Wandlebury legend". www.cantab.net. Retrieved 21 May 2025.

- ^ Oosthuizen, Susan (2016). "Culture and identity in the early medieval fenland landscape" (PDF).

- ^ Green, T., 2012. Britons and Anglo-‐Saxons.

- ^ "Key to English Place-names". kepn.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ Young, Simon (2003). "Young, Bishops of the Early Medieval Spanish Diocese of Britonia.pdf". Univercity of Florence.

- ^ Fleuriot, Leon (1980) Les origines de la Bretagne

- ^ Young, Simon. "Young, Iberian Addenda to Fleuriot's Toponymes.pdf". Acaedmia.

- ^ a b Schiffels et al. 2016, p. 1.

- ^ Schiffels et al. 2016, p. 3, Table 1.

- ^ Schiffels et al. 2016, p. 5.

- ^ a b Martiniano et al. 2018, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Martiniano et al. 2018, p. 3, Table 1.

- ^ a b Martiniano et al. 2018, p. 6. "Six of the seven individuals sampled here are clearly indigenous Britons in their genomic signal. When considered together, they are similar to the earlier Iron-Age sample, whilst the modern group with which they show closest affinity are Welsh. These six are also fixed for the Y-chromosome haplotype R1b-L51, which shows a cline in modern Britain, again with maximal frequencies among western populations. Interestingly, these people do not differ significantly from modern inhabitants of the same region (Yorkshire and Humberside) suggesting major genetic change in Eastern Britain within the last millennium and a half. That this could have been, in part, due to population influx associated with the Anglo-Saxon migrations is suggested by the different genetic signal of the later Anglo-Saxon genome."

- ^ Martiniano et al. 2018, pp. 1.

- ^ Martiniano et al. 2018, pp. 1, 6.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bannerman, John (1999). "The Scottish Takeover of Pictland and the relics of Columba". In Broun, Dauvit; Clancy, Thomas Owen (eds.). Spes Scotorum: Hope of Scots: Saint Columba, Iona and Scotland. Edinburgh: T.& T. Clark.

- Bromwich, Rachel; Foster, Idris Llewelyn; Jones, R. Brinley (1978). Astudiaethau ar yr Hengerdd: Studies in Old Welsh Poetry. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-0696-9.

- Broun, Dauvit (1999). "Dunkeld and the origin of Scottish identity". In Broun, Dauvit; Clancy, Thomas Owen (eds.). Spes Scotorum: Hope of Scots: Saint Columba, Iona and Scotland. Edinburgh: T.& T. Clark.

- Chadwick, Hector Munro; Chadwick, Nora K. (1940). The Growth of Literature. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511710988. ISBN 978-0-511-71098-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clarkson, Tim (2014). Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-1-906566-78-4.

- Corbishley, Mike; Gillingham, John; Kelly, Rosemary; Dawson, Ian; Mason, James; Morgan, Kenneth O. (1996) [1996]. "Celtic Britain". The Young Oxford History of Britain & Ireland. Walton St., Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019-910035-7. (The Young Oxford History of Britain & Ireland at the Internet Archive)

- Cunliffe, Barry; Koch, John T. (2016). "Introduction". In Cunliffe, Barry; Koch, John T. (eds.). Celtic from the West 3 : Atlantic Europe in the Metal Ages: questions of shared language. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-228-0. OCLC 936687654.

- Forsyth, Katherine (1997). Language in Pictland (PDF). De Keltische Draak. ISBN 90-802785-5-6.

- Forsyth, Katherine (2005). "Origins: Scotland to 1100". In Wormald, J. (ed.). Scotland: a History. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–37. ISBN 978-0-19-820615-6.

- Forsyth, Katherine (2006), "Pictish Language and Documents", in Koch, John T. (ed.), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, vol. 1: Aberdeen breviary - Celticism, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO

- Fraser, James E. (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Vol. 1. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1232-1.

- Giles, John Allen (1887). The Venerable Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England: Also the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. With Illustrative Notes, a Map of Anglo-Saxon England and a General Index (5th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons.

- Ingram, James; Giles, John Allen (1847). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: Everyman.

- Kapelle, W. E. (1979). The Norman Conquest of the North: the Region and its Transformation, 1000–1135. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-7099-0040-6.

- Karl, Raimund (2010). "The Celts from everywhere and nowhere: a re-evaluation of the origins of the Celts and the emergence of Celtic cultures". In Cunliffe, Barry; Koch, John T. (eds.). Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Vol. 15. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 39–64. doi:10.2307/j.ctv13pk64k.5. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4. JSTOR j.ctv13pk64k.5.

- Koch, John, ed. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- MacAulay, Donald (1992). The Celtic languages. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23127-2. OCLC 24541026.

- McCone, Kim (2013). "The Celts: questions of nomenclature and identity". In Ronan, Patricia (ed.). Ireland and its Contacts. University of Lausanne. pp. 19–36. ISBN 978-2-9700801-1-4.

- Martiniano, Rui; et al. (19 January 2016). "Genomic signals of migration and continuity in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons". Nature Communications. 7 10326. Nature Research. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710326M. doi:10.1038/ncomms10326. PMC 4735653. PMID 26783717.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1 November 2001). R F Foster (ed.). The Oxford History of Ireland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280202-X. (The Oxford History of Ireland at the Internet Archive)

- Patterson, N.; Isakov, M.; Booth, T. (2021). "Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age". Nature. 601 (7894): 588–594. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..588P. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4. PMC 8889665. PMID 34937049.

- Pattison, John E. (2008). "Is it necessary to assume an apartheid-like social structure in early Anglo-Saxon England?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 275 (1650): 2423–2429. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0352. PMC 2603190. PMID 18430641.

- Pattison, John E. (2011). "Integration versus Apartheid in post-Roman Britain: a Response to Thomas et al. (2008)". Human Biology. 83 (6): 715–733. doi:10.1353/hub.2011.a465108. JSTOR 41466778. PMID 22276970.

- Sawyer, P.H. (1998). "Britain and the Romans". From Roman Britain to Norman England. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17894-0.

- Schiffels, Stephan; et al. (19 January 2016). "Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history". Nature Communications. 7 (10408) 10408. Nature Research. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710408S. doi:10.1038/ncomms10408. PMC 4735688. PMID 26783965.

- Sims-Williams, Patrick (2020). "An Alternative to 'Celtic from the East' and 'Celtic from the West'". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 30 (3): 511–529. doi:10.1017/S0959774320000098. hdl:2160/317fdc72-f7ad-4a66-8335-db8f5d911437. ISSN 0959-7743. S2CID 216484936.

- Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22260-X. The Britons at the Internet Archive

- Swanton, Michael (1998). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-92129-9.

- Thorpe, Benjamin (1861). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Rerum Britannicarum medii aevi scriptores. Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts.

- Webster, Graham (1996). "The Celtic Britons under Rome". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge.

- Williams, Ann; Martin, G. H. (2002). Domesday Book: a complete translation. London: Penguin.

- Woolf, Alex (2007), "From Pictland to Alba 789–1070", The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, vol. 2, Edinburgh University Press

- Young, Simon (2002). Britonia: camiños novos. Serie Keltia (in Spanish). Vol. 17. Noia: Toxosoutos. ISBN 978-84-95622-58-7.