Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

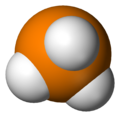

Phosphine

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Phosphane

| |||

| Other names

Hydrogen phosphide

Phosphamine Phosphorus trihydride Phosphorated hydrogen | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.328 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 287 | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2199 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| PH3 | |||

| Molar mass | 33.99758 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Colourless gas | ||

| Odor | odorless as pure compound; fish-like or garlic-like commercially[1] | ||

| Density | 1.379 g/L, gas (25 °C) | ||

| Melting point | −132.8 °C (−207.0 °F; 140.3 K) | ||

| Boiling point | −87.7 °C (−125.9 °F; 185.5 K) | ||

| 31.2 mg/100 ml (17 °C) | |||

| Solubility | Soluble in alcohol, ether, CS2 slightly soluble in benzene, chloroform, ethanol | ||

| Vapor pressure | 41.3 atm (20 °C)[1] | ||

| Conjugate acid | Phosphonium (PH+4) | ||

Refractive index (nD)

|

2.144 | ||

| Viscosity | 1.1×10−5 Pa⋅s | ||

| Structure | |||

| Trigonal pyramidal | |||

| 0.58 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

37 J/mol⋅K | ||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

210 J/mol⋅K[2] | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

5 kJ/mol[2] | ||

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

13 kJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | Flammable gas | ||

| 38 °C (100 °F; 311 K) (see text) | |||

| Explosive limits | 1.79–98%[1] | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

3.03 mg/kg (rat, oral) | ||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

11 ppm (rat, 4 hr)[3] | ||

LCLo (lowest published)

|

1000 ppm (mammal, 5 min) 270 ppm (mouse, 2 hr) 100 ppm (guinea pig, 4 hr) 50 ppm (cat, 2 hr) 2500 ppm (rabbit, 20 min) 1000 ppm (human, 5 min)[3] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 0.3 ppm (0.4 mg/m3)[1] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 0.3 ppm (0.4 mg/m3), ST 1 ppm (1 mg/m3)[1] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

50 ppm[1] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0694 | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other cations

|

|||

Related compounds

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Phosphine (IUPAC name: phosphane) is a colorless, flammable, highly toxic compound with the chemical formula PH3, classed as a pnictogen hydride. Pure phosphine is odorless, but technical grade samples have a highly unpleasant odor like rotting fish, due to the presence of substituted phosphine and diphosphane (P2H4). With traces of P2H4 present, PH3 is spontaneously flammable in air (pyrophoric), burning with a luminous flame. Phosphine is a highly toxic respiratory poison, and is immediately dangerous to life or health at 50 ppm. Phosphine has a trigonal pyramidal structure.

Phosphines are compounds that include PH3 and the organophosphines, which are derived from PH3 by substituting one or more hydrogen atoms with organic groups.[4] They have the general formula PH3−nRn. Phosphanes are saturated phosphorus hydrides of the form PnHn+2, such as triphosphane.[5] Phosphine (PH3) is the smallest of the phosphines and the smallest of the phosphanes.

History

[edit]Philippe Gengembre (1764–1838), a student of Lavoisier, first obtained phosphine in 1783 by heating white phosphorus in an aqueous solution of potash (potassium carbonate).[6][NB 1]

Perhaps because of its strong association with elemental phosphorus, phosphine was once regarded as a gaseous form of the element, but Lavoisier (1789) recognised it as a combination of phosphorus with hydrogen and described it as phosphure d'hydrogène (phosphide of hydrogen).[NB 2]

In 1844, Paul Thénard, son of the French chemist Louis Jacques Thénard, used a cold trap to separate diphosphine from phosphine that had been generated from calcium phosphide, thereby demonstrating that P2H4 is responsible for spontaneous flammability associated with PH3, and also for the characteristic orange/brown color that can form on surfaces, which is a polymerisation product.[7] He considered diphosphine's formula to be PH2, and thus an intermediate between elemental phosphorus, the higher polymers, and phosphine. Calcium phosphide (nominally Ca3P2) produces more P2H4 than other phosphides because of the preponderance of P-P bonds in the starting material.

The name "phosphine" was first used for organophosphorus compounds in 1857, being analogous to organic amines (NR3).[NB 3][8] The gas PH3 was named "phosphine" by 1865 (or earlier).[9]

Structure and reactions

[edit]PH3 is a trigonal pyramidal molecule with C3v molecular symmetry. The length of the P−H bond is 1.42 Å, the H−P−H bond angles are 93.5°. The dipole moment is 0.58 D, which increases with substitution of methyl groups in the series: CH3PH2, 1.10 D; (CH3)2PH, 1.23 D; (CH3)3P, 1.19 D. In contrast, the dipole moments of amines decrease with substitution, starting with ammonia, which has a dipole moment of 1.47 D. The low dipole moment and almost orthogonal bond angles lead to the conclusion that in PH3 the P−H bonds are almost entirely pσ(P) – sσ(H) and phosphorus 3s orbital contributes little to the P-H bonding. For this reason, the lone pair on phosphorus is predominantly formed by the 3s orbital of phosphorus. The upfield chemical shift of its 31P NMR signal accords with the conclusion that the lone pair electrons occupy the 3s orbital (Fluck, 1973). This electronic structure leads to a lack of nucleophilicity in general and lack of basicity in particular (pKaH = −14),[10] as well as an ability to form only weak hydrogen bonds.[11]

The aqueous solubility of PH3 is slight: 0.22 cm3 of gas dissolves in 1 cm3 of water. Phosphine dissolves more readily in non-polar solvents than in water because of the non-polar P−H bonds. It is technically amphoteric in water, but acid and base activity is poor. Proton exchange proceeds via a phosphonium (PH+4) ion in acidic solutions and via phosphanide (PH−2) at high pH, with equilibrium constants Kb = 4×10−28 and Ka = 41.6×10−29. Phosphine reacts with water only at high pressure and temperature, producing phosphoric acid and hydrogen:[12][13]

Burning phosphine in the air produces phosphoric acid:[14][12]

Preparation and occurrence

[edit]Phosphine may be prepared in a variety of ways.[15] Industrially it can be made by the reaction of white phosphorus with sodium or potassium hydroxide, producing potassium or sodium hypophosphite as a by-product.

Alternatively, the acid-catalyzed disproportionation of white phosphorus yields phosphoric acid and phosphine. Both routes have industrial significance; the acid route is the preferred method if further reaction of the phosphine to substituted phosphines is needed. The acid route requires purification and pressurizing.

Laboratory routes

[edit]It is prepared in the laboratory by disproportionation of phosphorous acid:[16]

Phosphine evolution occurs at around 200 °C.

Alternative methods include the hydrolysis of zinc phosphide:[17]

Some other metal phosphides could also be used, including aluminium phosphide or calcium phosphide. Pure samples of phosphine, free from P2H4, may be prepared using the action of potassium hydroxide on phosphonium iodide:

Occurrence

[edit]Phosphine is a worldwide constituent of the Earth's atmosphere at very low and highly variable concentrations.[18] It may contribute significantly to the global phosphorus biochemical cycle. The most likely source is reduction of phosphate in decaying organic matter, possibly via partial reductions and disproportionations, since environmental systems do not have known reducing agents of sufficient strength to directly convert phosphate to phosphine.[19]

It is also found in Jupiter's atmosphere.[20]

Possible extraterrestrial biosignature

[edit]In 2020 a spectroscopic analysis was reported to show signs of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus in quantities that could not be explained by known abiotic processes.[21][22][23] Later re-analysis of this work showed interpolation errors had been made, and re-analysis of data with the fixed algorithm do not result in the detection of phosphine.[24][25] The authors of the original study then claimed to detect it with a much lower concentration of 1 ppb.[26][disputed – discuss]

Applications

[edit]Organophosphorus chemistry

[edit]Phosphine is a precursor to many organophosphorus compounds. It reacts with formaldehyde in the presence of hydrogen chloride to give tetrakis(hydroxymethyl)phosphonium chloride, which is used in textiles. The hydrophosphination of alkenes is versatile route to a variety of phosphines. For example, in the presence of basic catalysts PH3 adds of Michael acceptors. Thus with acrylonitrile, it reacts to give tris(cyanoethyl)phosphine:[27]

Acid catalysis is applicable to hydrophosphination with isobutylene and related analogues:

where R is CH3, alkyl, etc.

Microelectronics

[edit]Phosphine is used as a dopant in the semiconductor industry, and a precursor for the deposition of compound semiconductors. Commercially significant products include gallium phosphide and indium phosphide.[28]

Fumigant (pest control)

[edit]Phosphine is an attractive fumigant because it is lethal to insects and rodents, but degrades to phosphoric acid, which is non-toxic. As sources of phosphine, for farm use, pellets of aluminium phosphide (AlP), calcium phosphide (Ca3P2), or zinc phosphide (Zn3P2) are used. These phosphides release phosphine upon contact with atmospheric water or rodents' stomach acid. These pellets also contain reagents to reduce the potential for ignition or explosion of the released phosphine.

An alternative is the use of phosphine gas itself which requires dilution with either CO2 or N2 or even air to bring it below the flammability point. Use of the gas avoids the issues related with the solid residues left by metal phosphide and results in faster, more efficient control of the target pests.

One problem with phosphine fumigants is the increased resistance by insects.[29]

Toxicity and safety

[edit]Deaths have resulted from accidental exposure to fumigation materials containing aluminium phosphide or phosphine.[30][31][32][33] It can be absorbed either by inhalation or transdermally.[30] As a respiratory poison, it affects the transport of oxygen or interferes with the utilization of oxygen by various cells in the body.[32] Exposure results in pulmonary edema (the lungs fill with fluid).[33] Phosphine gas is heavier than air so it stays near the floor.[34]

Phosphine appears to be mainly a redox toxin, causing cell damage by inducing oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction.[35] Resistance in insects is caused by a mutation in a mitochondrial metabolic gene.[29]

Phosphine can be absorbed into the body by inhalation. The main target organ of phosphine gas is the respiratory tract.[36] According to the 2009 U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) pocket guide, and U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulation, the 8 hour average respiratory exposure should not exceed 0.3 ppm. NIOSH recommends that the short term respiratory exposure to phosphine gas should not exceed 1 ppm. The Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health level is 50 ppm. Overexposure to phosphine gas causes nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, thirst, chest tightness, dyspnea (breathing difficulty), muscle pain, chills, stupor or syncope, and pulmonary edema.[37][38] Phosphine has been reported to have the odor of decaying fish or garlic at concentrations below 0.3 ppm. The smell is normally restricted to laboratory areas or phosphine processing since the smell comes from the way the phosphine is extracted from the environment. However, it may occur elsewhere, such as in industrial waste landfills. Exposure to higher concentrations may cause olfactory fatigue.[39]

Fumigation hazards

[edit]Phosphine is used for pest control, but its usage is strictly regulated due to high toxicity.[40][41] Gas from phosphine has high mortality rate[42] and has caused deaths in Sweden and other countries.[43][44][45]

Because the previously popular fumigant methyl bromide has been phased out in some countries under the Montreal Protocol, phosphine is the only widely used, cost-effective, rapidly acting fumigant that does not leave residues on the stored product. Pests with high levels of resistance toward phosphine have become common in Asia, Australia and Brazil. High level resistance is also likely to occur in other regions, but has not been as closely monitored. Genetic variants that contribute to high level resistance to phosphine have been identified in the dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase gene.[29] Identification of this gene now allows rapid molecular identification of resistant insects.

Explosiveness

[edit]Phosphine gas is denser than air and hence may collect in low-lying areas. It can form explosive mixtures with air, and may also self-ignite.[12]

In fiction

[edit]Anne McCaffrey's Dragonriders of Pern series features genetically engineered dragons that breathe fire by producing phosphine by extracting it from minerals of their native planet.

In the 2008 pilot of the crime drama television series Breaking Bad, Walter White poisons two rival gangsters by adding red phosphorus to boiling water to produce phosphine gas. However, this reaction in reality would require white phosphorus instead, and for the water to contain sodium hydroxide.[46]

See also

[edit]- Diphosphane, H2P−PH2, simplified to P2H4

- Diphosphene, HP=PH

Notes

[edit]- ^ For further information about the early history of phosphine, see:

- The Encyclopædia Britannica (1911 edition), vol. 21, p. 480: Phosphorus: Phosphine. Archived 4 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Thomas Thomson, A System of Chemistry, 6th ed. (London, England: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1820), vol. 1, p. 272. Archived 4 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Note:

- On p. 222 Archived 24 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine of his Traité élémentaire de chimie, vol. 1, (Paris, France: Cuchet, 1789), Lavoisier calls the compound of phosphorus and hydrogen "phosphure d'hydrogène" (hydrogen phosphide). However, on p. 216 Archived 24 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, he calls the compound of hydrogen and phosphorus "Combinaison inconnue." (unknown combination), yet in a footnote, he says about the reactions of hydrogen with sulfur and with phosphorus: "Ces combinaisons ont lieu dans l'état de gaz & il en résulte du gaz hydrogène sulfurisé & phosphorisé." (These combinations occur in the gaseous state, and there results from them sulfurized and phosphorized hydrogen gas.)

- In Robert Kerr's 1790 English translation of Lavoisier's Traité élémentaire de chimie ... — namely, Lavoisier with Robert Kerr, trans., Elements of Chemistry ... (Edinburgh, Scotland: William Creech, 1790) — Kerr translates Lavoisier's "phosphure d'hydrogène" as "phosphuret of hydrogen" (p. 204), and whereas Lavoisier — on p. 216 of his Traité élémentaire de chimie ... — gave no name to the combination of hydrogen and phosphorus, Kerr calls it "hydruret of phosphorus, or phosphuret of hydrogen" (p. 198). Lavoisier's note about this compound — "Combinaison inconnue." — is translated: "Hitherto unknown." Lavoisier's footnote is translated as: "These combinations take place in the state of gas, and form, respectively, sulphurated and phosphorated oxygen gas." The word "oxygen" in the translation is an error because the original text clearly reads "hydrogène" (hydrogen). (The error was corrected in subsequent editions.)

- ^ In 1857, August Wilhelm von Hofmann announced the synthesis of organic compounds containing phosphorus, which he named "trimethylphosphine" and "triethylphosphine", in analogy with "amine" (organo-nitrogen compounds), "arsine" (organo-arsenic compounds), and "stibine" (organo-antimony compounds).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0505". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles (6th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. A22. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ a b "Phosphine". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "phosphines". doi:10.1351/goldbook.P04553

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "phosphanes". doi:10.1351/goldbook.P04548

- ^ Gengembre (1783) "Mémoire sur un nouveau gas obtenu, par l'action des substances alkalines, sur le phosphore de Kunckel" (Memoir on a new gas obtained by the action of alkaline substances on Kunckel's phosphorus), Mémoires de mathématique et de physique, 10 : 651–658.

- ^ Paul Thénard (1844) "Mémoire sur les combinaisons du phosphore avec l'hydrogène" Archived 15 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine (Memoir on the compounds of phosphorus with hydrogen), Comptes rendus, 18 : 652–655.

- ^ A.W. Hofmann; Auguste Cahours (1857). "Researches on the phosphorus bases". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London (8): 523–527. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

(From page 524:) The bases Me3P and E3P, the products of this reaction, which we propose to call respectively trimethylphosphine and triethylphosphine, ...

- ^ William Odling, A Course of Practical Chemistry Arranged for the Use of Medical Students, 2nd ed. (London, England: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1865), pp. 227, 230.

- ^ Streitwieser, Andrew; Heathcock, Clayton H.; Kosower, Edward M. (2017) [1st ed. 1998]. Introduction to Organic Chemistry (revised 4th ed.). New Delhi: Medtech. p. 828. ISBN 978-93-85998-89-8.

- ^ Sennikov, P. G. (1994). "Weak H-Bonding by Second-Row (PH3, H2S) and Third-Row (AsH3, H2Se) Hydrides". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 98 (19): 4973–4981. doi:10.1021/j100070a006.

- ^ a b c Material Safety Data Sheet: Phosphine/hydrogen Gas Mixture (PDF) (Report). Matheson Tri-Gas. 8 September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Joseph; Woeller, Fritz; Flores, Jose; Krebsbach, Rita (November 1969). "Electric Discharge Reactions in Mixtures of Phosphine, Methane, Ammonia and Water". Nature. 224 (5221): 796–798. Bibcode:1969Natur.224..796R. doi:10.1038/224796a0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 5361652. S2CID 4195473.

- ^ "Phosphine: Lung Damaging Agent". United States: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). 8 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Toy, A. D. F. (1973). The Chemistry of Phosphorus. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.

- ^ Gokhale, S. D.; Jolly, W. L. (1967). "Phosphine". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 9. pp. 56–58. doi:10.1002/9780470132401.ch17. ISBN 978-0-470-13168-8.

- ^ Barber, Thomas; Baljournal=Organic Syntheses, Liam T. (2021). "Synthesis of tert-Alkyl Phosphines: Preparation of Di-(1-adamantyl)phosphonium Trifluoromethanesulfonate and Tri-(1-adamantyl)phosphine". Organic Syntheses. 98: 289–314. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.098.0289.

- ^ Glindemann, D.; Bergmann, A.; Stottmeister, U.; Gassmann, G. (1996). "Phosphine in the lower terrestrial troposphere". Naturwissenschaften. 83 (3): 131–133. Bibcode:1996NW.....83..131G. doi:10.1007/BF01142179. S2CID 32611695.

- ^ Roels, J.; Verstraete, W. (2001). "Biological formation of volatile phosphorus compounds, a review paper". Bioresource Technology. 79 (3): 243–250. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00032-3. PMID 11499578.

- ^ Kaplan, Sarah (11 July 2016). "The first water clouds are found outside our solar system – around a failed star". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Sousa-Silva, Clara; Seager, Sara; Ranjan, Sukrit; Petkowski, Janusz Jurand; Zhan, Zhuchang; Hu, Renyu; Bains, William (11 October 2019). "Phosphine as a Biosignature Gas in Exoplanet Atmospheres". Astrobiology. 20 (2) (published February 2020): 235–268. arXiv:1910.05224. Bibcode:2020AsBio..20..235S. doi:10.1089/ast.2018.1954. PMID 31755740. S2CID 204401807.

- ^ Chu, Jennifer (18 December 2019). "A sign that aliens could stink". MIT News. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Phosphine Could Signal Existence of Alien Anaerobic Life on Rocky Planets". Sci-News. 26 December 2019. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Snellen, I. A. G.; Guzman-Ramirez, L.; Hogerheijde, M. R.; Hygate, A. P. S.; van der Tak, F. F. S. (2020). "Re-analysis of the 267-GHz ALMA observations of Venus No statistically significant detection of phosphine". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 644: L2. arXiv:2010.09761. Bibcode:2020A&A...644L...2S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039717. S2CID 224803085.

- ^ Thompson, M. A. (2021). "The statistical reliability of 267 GHz JCMT observations of Venus: No significant evidence for phosphine absorption". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 501 (1): L18 – L22. arXiv:2010.15188. Bibcode:2021MNRAS.501L..18T. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slaa187. S2CID 225103303.

- ^ Greaves, Jane S.; Richards, Anita M. S.; Bains, William; Rimmer, Paul B.; Clements, David L.; Seager, Sara; Petkowski, Janusz J.; Sousa-Silva, Clara; Ranjan, Sukrit; Fraser, Helen J. (2021). "Reply to: No evidence of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus from independent analyses". Nature Astronomy. 5 (7): 636–639. arXiv:2011.08176. Bibcode:2021NatAs...5..636G. doi:10.1038/s41550-021-01424-x. S2CID 233296859.

- ^ Trofimov, Boris A.; Arbuzova, Svetlana N.; Gusarova, Nina K. (1999). "Phosphine in the Synthesis of Organophosphorus Compounds". Russian Chemical Reviews. 68 (3): 215–227. Bibcode:1999RuCRv..68..215T. doi:10.1070/RC1999v068n03ABEH000464. S2CID 250775640.

- ^ Bettermann, G.; Krause, W.; Riess, G.; Hofmann, T. (2002). "Phosphorus Compounds, Inorganic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_527. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ a b c Schlipalius, D. I.; Valmas, N.; Tuck, A. G.; Jagadeesan, R.; Ma, L.; Kaur, R.; et al. (2012). "A Core Metabolic Enzyme Mediates Resistance to Phosphine Gas". Science. 338 (6108): 807–810. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..807S. doi:10.1126/science.1224951. PMID 23139334. S2CID 10390339.

- ^ a b Ido Efrati; Nir Hasson (22 January 2014). "Two toddlers die after Jerusalem home sprayed for pests". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "La familia de Alcalá de Guadaíra murió tras inhalar fosfina de unos tapones". RTVE.es (in Spanish). Radio y Televisión Española. EFE. 3 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ a b Julia Sisler (13 March 2014). "Deaths of Quebec women in Thailand may have been caused by pesticide". CBC News. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ a b Amy B Wang (3 January 2017). "4 children killed after pesticide released toxic gas underneath their home, police say". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "Pesticide blamed in 8-month-old's death in Fort McMurray". CBC News. 23 February 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Nath, NS; Bhattacharya, I; Tuck, AG; Schlipalius, DI; Ebert, PR (2011). "Mechanisms of phosphine toxicity". Journal of Toxicology. 2011 494168. doi:10.1155/2011/494168. PMC 3135219. PMID 21776261.

- ^ "NIOSH Emergency Response Card". CDC. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "NIOSH pocket guide". CDC. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "WHO – Data Sheets on Pesticides – No. 46: Phosphine". Inchem.org. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ NIOSH alert: preventing phosphine poisoning and explosions during fumigation (Report). CDC. 1 September 1999. doi:10.26616/nioshpub99126. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Wallstén, Beata (13 February 2024). "Åklagaren bekräftar: Familjen i Söderhamn förgiftades av fosfin". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. "Hälsorisker och förebyggande rutiner vid hantering av fumigerade containrar" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ A Farrar, Ross; B Justus, Angelo; A Masurkar, Vikram; M Garrett, Peter (2022). "Unexpected survival after deliberate phosphine gas poisoning: An Australian experience of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation rescue in this setting". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 50 (3): 250–254. doi:10.1177/0310057X211047603. ISSN 0310-057X. PMID 34871510.

- ^ Berglin, Rikard (13 February 2024). "Giftgåtan i Söderhamn: Gas tros ha dödat flickan". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ LJ, Willers-Russo (1999). "Three fatalities involving phosphine gas, produced as a result of methamphetamine manufacturing". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 44 (3). J Forensic Sci: 647–652. doi:10.1520/JFS14525J. ISSN 0022-1198. PMID 10408124.

- ^ Moirangthem, Sangita; Vidua, Raghvendra; Jahan, Afsar; Patnaik, Mrinal; Chaurasia, Jai (8 July 2023). "Phosphine Gas Poisoning". American Journal of Forensic Medicine & Pathology. 44 (4). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 350–353. doi:10.1097/paf.0000000000000855. ISSN 1533-404X. PMID 37438888.

- ^ Hare, Jonathan (1 March 2011). "Breaking Bad – poisoning gangsters with phosphine gas". education in chemistry. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Fluck, E. (1973). "The Chemistry of Phosphine". Topics in Current Chemistry. Fortschritte der Chemischen Forschung. 35: 1–64. doi:10.1007/BFb0051358. ISBN 3-540-06080-4. S2CID 91394007.

- World Health Organization (1988). Phosphine and Selected Metal Phosphides. Environmental Health Criteria. Vol. 73. Geneva: Joint sponsorship of UNEP, ILO and WHO.