Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

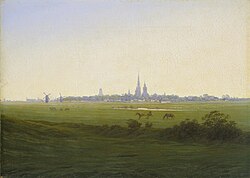

Greifswald

View on WikipediaGreifswald (German pronunciation: [ˈɡʁaɪfsvalt] ⓘ; Low German: Griepswold), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (German: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald) is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin and Neubrandenburg. In 2021 it surpassed Stralsund for the first time, and became the largest city in the Pomeranian part of the state. It sits on the River Ryck, at its mouth into the Danish Wiek, a sub-bay of the Bay of Greifswald, which is itself a sub-bay of the Bay of Pomerania of the Baltic Sea.

Key Information

It is the seat of the district of Western Pomerania-Greifswald, and is located roughly in the middle between the two largest Pomeranian islands of Rügen and Usedom. The closest larger cities are Stralsund, Rostock, Szczecin and Schwerin. It lies west of the River Zarow, the historical cultural and linguistic boundary between West (west of the river) and Central Pomerania (east of the river). The city derives its name from the dukes of Pomerania, the House of Griffin, and thus ultimately from the Pomeranian Griffin, and its name hence translates as "Griffin's Forest".

The University of Greifswald, which was founded in 1456, is the second-oldest university in the Baltic Region after the University of Rostock. The city is well-known for the ruins of Eldena Abbey (formerly Hilda Abbey), a frequent subject of the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich, who was born in the city when it was part of Swedish Pomerania. Greifswald is the seat of the Pomeranian State Museum (Pommersches Landesmuseum). The recently built Ryck Barrier (Rycksperrwerk) protects the city from exceptionally high tides and storm surges moving up from the Baltic.

The city's population was listed at 59,332 in 2021, including many of the 12,500 students and 5,000 employees of the University of Greifswald. Greifswald draws international attention due to the university, its surrounding BioCon Valley, the Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline which ends at nearby Lubmin, and the Wendelstein 7-X nuclear fusion projects.

Geography

[edit]Greifswald is located in the northeast of Germany, approximately equidistant from Germany's two largest islands, Rügen and Usedom. The city is situated at the south end of the Bay of Greifswald, the historic centre being about five kilometres (three miles) up the river Ryck that crosses the city. The area around Greifswald is mainly flat, and hardly reaches more than 20 m above sea level. Two islands, Koos and Riems, are also part of Greifswald. Three of Germany's fourteen national parks can be reached by car in one hour or less from Greifswald.

Greifswald is also roughly equidistant from Germany's two largest cities, Berlin (240 km or 150 mi) and Hamburg (260 km or 160 mi). The nearest larger cities are Stralsund and Rostock.

The coastal part of Greifswald at the mouth of the Ryck, named Greifswald-Wieck, evolved from a fishing village. Today it provides a small beach, a marina and the main port for Greifswald.

Climate

[edit]Greifswald features an oceanic climate with some humid continental influence. Summers are pleasantly warm, although chilly at night. Due to its coastal location, heatwaves in Greifswald tend to be less extreme than other nearby locations inland. Winters are mild to cold, with occasional cold fronts coming in from Scandinavia or Siberia. Precipitation is spread throughout the year and comparatively low by German standards, while sunshine hours are above the German average.

| Climate data for Greifswald (1991–2020 normals, extremes since 1975) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

32.1 (89.8) |

36.6 (97.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.5 (97.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

25.7 (78.3) |

19.1 (66.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

36.6 (97.9) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 9.7 (49.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.8 (60.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.9 (84.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

32.3 (90.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.2 (39.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

1.6 (34.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.1 (46.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

2.2 (36.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −9.7 (14.5) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.1 (−9.6) |

−23.2 (−9.8) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−12.1 (10.2) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−23.2 (−9.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45.7 (1.80) |

36.9 (1.45) |

39.0 (1.54) |

32.3 (1.27) |

52.3 (2.06) |

60.5 (2.38) |

67.1 (2.64) |

71.7 (2.82) |

52.3 (2.06) |

49.9 (1.96) |

43.3 (1.70) |

48.4 (1.91) |

599.4 (23.60) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 16.6 | 15.1 | 13.4 | 11.2 | 12.5 | 13.2 | 14.4 | 13.4 | 12.8 | 15.7 | 15.7 | 17.1 | 171.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 8.6 | 9.8 | 5.0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 5.2 | 30.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.8 | 83.2 | 79.2 | 74.9 | 74.5 | 73.9 | 74.8 | 76.1 | 80.1 | 83.6 | 87.4 | 87.6 | 80.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 47.4 | 67.5 | 127.2 | 196.6 | 243.7 | 239.0 | 242.4 | 217.2 | 162.2 | 110.2 | 50.7 | 35.7 | 1,739.7 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[3] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat[4] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]Greifswald was founded in 1199 when Cistercian monks founded the Eldena Abbey.[5] In 1250, Wartislaw III, Duke of Pomerania, granted town privileges to Greifswald according to the Lübeck law.[5]

Middle Ages and Reformation

[edit]

In medieval times, the site of Greifswald was an unsettled woodland which marked the border between the Danish Principality of Rügen and the Pomeranian County of Gützkow, which at that time was also under Danish control. In 1199, the Rugian Prince Jaromar I allowed Danish Cistercian monks to build Hilda Abbey, now Eldena Abbey, at the mouth of the River Ryck. Among the lands granted the monks was a natural salt evaporation pond a short way up the river, a site also crossed by an important south–north via regia trade route. This site was named Gryp(he)swold(e), which is the Low German precursor of the city's modern name – which means "Griffin's Forest." Legend says the monks were shown the best site for settlement by a mighty griffin living in a tree that supposedly grew on what became Greifswald's oldest street, the Schuhagen. The town's construction followed a scheme of rectangular streets, with church and market sites reserved in central positions. It was settled primarily by Germans in the course of the Ostsiedlung, but settlers from other nations and Wends from nearby were attracted, too.

The salt trade helped Eldena Abbey to become an influential religious center, and Greifswald became a widely known market. When the Danes had to surrender their Pomeranian lands south of the Ryck, after losing the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227, the town succeeded to the Pomeranian dukes. In 1241, the Rugian prince Wizlaw I and the Pomeranian duke Wartislaw III both granted Greifswald market rights. In 1250, the latter granted the town a charter under Lübeck law, after he had been permitted to acquire the town site as a fief from Eldena Abbey in 1248.

When Jazco of Salzwedel from Gützkow founded a Franciscan friary within the walls of Greifswald, the Cistercians at Eldena lost much of their influence on the city's further development. Just beyond Greifswald's western limits, a town-like suburb (Neustadt) arose, separated from Greifswald by a ditch. In 1264, Neustadt was incorporated and the ditch was filled in.

Eldena Abbey and the major buildings of Greifswald were erected in the North German Brick Gothic (Backsteingotik) style, found along the entire southern coast of the Baltic.

Due to a steady population increase, Greifswald became at the end of the 13th century one of the earliest members of the Hanseatic League, which further increased its trade and wealth. After 1296, Greifswald's citizens no longer needed to serve in the Pomeranian army, and Pomeranian dukes did not reside in the city.

In 1456, Greifswald's mayor Heinrich Rubenow laid the foundations of one of the oldest universities in the world, the University of Greifswald, which was one of the first in Germany, and was, successively, the single oldest in Sweden and Prussia.

In the course of Reformation, Eldena Abbey ceased to function as a monastery. Its possessions fell to the Pomeranian dukes; the bricks of its Gothic buildings were used by the locals for other construction. Eldena lost its separate status and was later absorbed into the town of Greifswald. The religious houses within the town walls, the priories of the Blackfriars (Dominicans) in the northwest and the Greyfriars (Franciscans) in the southeast, were secularized. The buildings of the Dominicans (the "black monastery") were turned over to the university; the site is still used as part of the medical campus. The Franciscan friary ("the "grey monastery") and its succeeding buildings are now the Pomeranian State Museum.

During the Thirty Years' War, Greifswald was occupied by (Catholic) Imperial forces from 1627 to 1631,[6] and thereafter, under the Treaty of Stettin (1630), by (Protestant) Swedish forces.[7]

1631/48—1815: Sweden

[edit]

During the Thirty Years' War, Swedish forces entered the Duchy of Pomerania in 1630.[6] Greifswald was besieged by Swedish troops on 12 June 1631[6] and surrendered on 16 June.[6] Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden had returned from Brandenburg to supervise the siege, and upon his arrival received the university's homage for the liberation from Catholic forces.[6] After the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), Greifswald and the region surrounding it became part of the Kingdom of Sweden. Swedish Pomerania, as it was then called, remained part of the Swedish kingdom until 1815,[8] when it became part of the Kingdom of Prussia as the Province of Pomerania. In 1871, it devolved to Germany.

The Thirty Years' War had caused starvation throughout Germany, and by 1630 Greifswald's population had shrunk by two-thirds. Many buildings were left vacant and fell into decay. Soon, other wars followed: the Swedish-Polish War and the Swedish-Brandenburg War both involved the nominally Swedish town of Greifswald. In 1659 and 1678, Brandenburgian troops bombarded the town. The first bombardment hit mainly the northeast part of town, wrecking 16 houses. The second bombardment leveled 30 houses and damaged hundreds more all over the city. Cannonballs of this second bombardment can still be seen in the walls of St Mary's Church.

During the Great Northern War (1700–1721, Greifswald was compelled to house soldiers. While besieging neighboring Stralsund, Russian tsar Peter the Great allied with George I of Great Britain in the Treaty of Greifswald. Large fires in 1713 and 1736 destroyed houses and other buildings, including City Hall. The Swedish government had issued decrees in 1669 and 1689 absolving anyone of taxes who built or rebuilt a house. These decrees remained essentially in force, under Prussian administration, until 1824.[9]

In 1763, Greifswald Botanic Garden was founded.

1815 – today: Germany

[edit]

During the 19th century, Greifswald attracted many Polish students.[10] After Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland) and Berlin, Greifswald hosted the third-largest group of Polish students in Germany.[11]

About 1900, the town – for the first time since the Middle Ages – expanded significantly beyond the old town walls. Also, a major railway connected Greifswald to Stralsund and Berlin; a local railway line further connected Greifswald to Wolgast.

The city survived World War II without much destruction, even though it housed a large German Army (Wehrmacht) garrison. During the war, in May 1940, the Stalag II-C prisoner-of-war camp was relocated to Greifswald from Dobiegniew, and it housed French, Belgian, Serbian and Soviet POWs with many sent to forced labor detachments in the region.[12] In the spring of 1945, the camp was evacuated to the west.[12] In April 1945, German Army Colonel (Oberst) Rudolf Petershagen defied orders and surrendered the city to the Red Army without a fight.

From 1949 to 1990, Greifswald was part of the German Democratic Republic (DDR). During this time, most historical buildings in the medieval parts of the city were neglected and a number of old buildings were pulled down. The population increased significantly, because of the construction of a nominal 1760 MW Soviet-made nuclear power plant in Lubmin, which was closed in the early 1990s. New suburbs were erected in the monolithic industrial socialist style (see Plattenbau). They still house most of the city's population.[citation needed] These new suburbs were placed east and southeast of central Greifswald, shifting the former town center to the northwestern edge of the modern town.

Reconstruction of the old town began in the late 1980s. Nearly all of it has been restored. Before that almost all of the old northern town adjacent to the port was demolished and subsequently rebuilt. The historic marketplace is considered one of the most beautiful in northern Germany. The town attracts many tourists, due in part to its proximity to the Baltic Sea.

Greifswald's greatest population was reached in 1988, with about 68,000 inhabitants, but it decreased afterward to 55,000, where it has now stabilized. Reasons for this included migration to western German cities as well as suburbanisation. However, the number of students quadrupled from 3,000 in 1990 to more than 11,000 in 2007 and the university employs 5,000 people; nearly one in three people in Greifswald are linked in some way to higher education.

Despite its relatively small population, Greifswald retains a supra-regional relevance linked to its intellectual role as a university town and to the taking of the central functions of the former Prussian Province of Pomerania after World War II, such as the seat of the bishop of the Pomeranian Lutheran Church, the state archives (Landesarchiv) and the Pomeranian Museum (Pommersches Landesmuseum). Three courts of the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern are also based at Greifswald:

- the Supreme Administrative Court (Oberverwaltungsgericht);

- the Supreme Constitutional Court (Landesverfassungsgericht); and

- the Fiscal Court Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Finanzgericht)

Administrative division

[edit]| District (modern) |

District (historical) |

Amalgamation | Size (ha) |

Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| „Innenstadt“ (downtown) |

Innenstadt | 87.0 | 3.883 | |

| Steinbeckervorstadt | 349.6 | 163 | ||

| Fleischervorstadt | 52.7 | 2.911 | ||

| Nördliche Mühlenvorstadt | 173.8 | 4.097 | ||

| Südliche Mühlenvorstadt, Obstbausiedlung |

108.1 | 4.650 | ||

| Fettenvorstadt, Stadtrandsiedlung |

657.3 | 2.853 | ||

| Industriegebiet | 634.7 | 583 | ||

| „Schönwalde I und Südstadt“ |

Schönwalde I, Südstadt |

132.1 | 12.583 | |

| „Schönwalde II“ | Schönwalde II | 88.0 | 9.994 | |

| Groß Schönwalde | 1974 | 580.8 | 749 | |

| „Ostseeviertel“ | Ostseeviertel | 219.7 | 8.577 | |

| „Wieck“ | Ladebow | 1939 | 544.4 | 499 |

| Wieck | 1939 | 44.2 | 395 | |

| „Eldena“ | Eldena | 1939 | 675.5 | 1.994 |

| „Friedrichshagen“ | Friedrichshagen | 1960 | 436.5 | 196 |

| „Riems“ | Riems, Insel Koos |

233.6 | 814 | |

| (Size and population data as of 2002) | ||||

Economy

[edit]

Greifswald and Stralsund are the largest cities in the Vorpommern part of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Of great importance to the city's economy is the local university with its 12,000 students and nearly 5,000 employees in addition to many people employed at independent research facilities such as the Friedrich Loeffler Institute and spin-off firms.

Greifswald is also the seat of the diocese of the Pomeranian Evangelical Church as well as the seat of the state's chief constitutional court, and chief financial court.

Tourism plays a vital role as Greifswald is situated between the islands of Rügen and Usedom on the popular German Baltic coast, which brings in many tourists.

One of Europe's largest producers of photovoltaic modules, Berlin-based Solon SE, has a production site in Greifswald. The world's third-largest producer of yachts worldwide, HanseYachts, is based in Greifswald. In the energy sector, an offshore natural gas pipeline from Russia to Germany, Nord Stream 1, stops in Lubmin (near Greifswald). Riemser Arzneimittel is a pharmaceutical company based on the island of Riems, which is part of the city of Greifswald. Siemens Communications F & E produces goods here as well.

In a 2008 study,[13] Greifswald was declared Germany's most dynamic city. According to another 2008 study, Greifswald is the "youngest city" in Germany having the highest percentage of heads of household under 30 years of age.[14]

Politics

[edit]The current mayor of Greifswald is Stefan Fassbinder (Greens) since 2015. The most recent mayoral election was held on 12 June 2022, with a runoff held on 26 June, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Stefan Fassbinder | Greens/SPD/Left | 9,351 | 48.5 | 9,329 | 56.1 | |

| Madeleine Tolani | Christian Democratic Union | 6,385 | 33.1 | 7,308 | 43.9 | |

| Ina Schuppa-Wittfoth | dieBasis | 1,569 | 8.1 | |||

| Konstantin Zirwick | Free Democratic Party | 529 | 2.8 | |||

| Daniel Küther | Independent | 520 | 2.7 | |||

| Gamal Khalil | Independent | 511 | 2.6 | |||

| Lea Alexandra Siewert | Independent | 399 | 2.1 | |||

| Valid votes | 19,264 | 99.4 | 16,637 | 99.3 | ||

| Invalid votes | 114 | 0.6 | 121 | 0.7 | ||

| Total | 19,378 | 100.0 | 16,758 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 47,409 | 40.9 | 47,290 | 35.4 | ||

| Source: City of Greifswald (1st round, 2nd round) | ||||||

The most recent city council election was held on 9 June 2024, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 17,490 | 20.1 | 9 | |||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 14,155 | 16.2 | 7 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 11,470 | 13.2 | 6 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 8,001 | 9.2 | 4 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 7,644 | 8.8 | 4 | |||

| Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) | 5,966 | 6.8 | New | 3 | New | |

| Animal Protection Party (Tierschutz) | 4,871 | 5.6 | 2 | |||

| Initiative Referendum Greifswald (IBG) | 4,823 | 5.5 | New | 2 | New | |

| Citizens' List Greifswald (BG) | 3,856 | 4.4 | 2 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 2,431 | 2.8 | 1 | |||

| Alternative List (AL) | 1,633 | 1.9 | 1 | |||

| Alliance of the Civic Centre (AdbM) | 1,286 | 1.5 | New | 1 | New | |

| Die PARTEI | 1,117 | 1.3 | New | 1 | New | |

| Volt Germany (Volt) | 1,079 | 1.2 | New | 0 | New | |

| Free Voters (FW) | 500 | 0.6 | New | 0 | New | |

| German Communist Party (DKP) | 97 | 0.1 | New | 0 | New | |

| Independents | 781 | 0.9 | New | 0 | New | |

| Valid votes | 87,200 | 100.0 | ||||

| Invalid ballots | 1,109 | 3.7 | ||||

| Total ballots | 30,007 | 100.0 | 43 | ±0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 47,059 | 63.8 | ||||

| Source: City of Greifswald | ||||||

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Education

[edit]University

[edit]

Founded in 1456, the University of Greifswald is one of the oldest universities in both Germany and Europe. Currently, about 12,300 students study at five faculties: theology, law/economics, medicine, humanities and social sciences, and mathematics/natural sciences.

The university co-operates with many research facilities, such as:

- the Max-Planck-Institut für Plasmaphysik (plasma physics) has its second site (after Garching) in Greifswald and is experimenting with a stellarator, Wendelstein 7-X.

- Alfried Krupp Institute of Advanced Study

- Friedrich Loeffler Institute on the Isle of Riems (National Research Institute for Animal Health)

- Institut für Niedertemperatur-Plasmaphysik (Institute of Low Temperature Plasma Physics)

- Technologiezentrum (Centre for Technology)

- Biotechnikum (Centre for Bioscience)

Secondary schools

[edit]- Alexander-von-Humboldt-Gymnasium

- Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Gymnasium (founded in 1561 as schola senatoria and one of the oldest schools still existing in Germany)

- Johann-Gottfried-Herder-Gymnasium (fused with the Jahn-Gymnasium in 2006)

- Ostseegymnasium

Culture

[edit]Museums, exhibitions, and cultural events

[edit]

Greifswald has a number of museums and exhibitions, most notably the Pomeranian State Museum (German: Pommersches Landesmuseum): history of Pomerania and arts, including works by Caspar David Friedrich, a native of Greifswald. The University of Greifswald also has a large number of collections, some of which are on display for the public.

Events and attractions hosted in Greifswald include:

- Theater Vorpommern: theatre, orchestra and opera

- Stadthalle Greifswald: medium-sized convention centre

- Festspiele Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Greifswald is one of several sites of the state's classical music festival

- Nordischer Klang is the largest festival of Nordic culture outside of the Nordic countries themselves

- Bach festival

- Eldena Jazz Evenings

- Gaffelrigg summer fair

- Museumshafen: historic ships in the "museum port"

- regular literary events in the Koeppenhaus

- St. Spiritus cultural centre

- Greifswald International Students Festival (GrIStuF e. V.)

- Radio 98eins (open radio)

- Greifswald Night of Music (Greifswalder Musiknacht)

- Greifswald long-ship festival (Greifswalder Drachenbootfest)

Cinemas

[edit]Art house is shown regularly at the film club "Casablanca",[17] which has existed since 1992. It puts its focus on the heritage of 35mm films. The Koeppenhaus shows art house cinema as part of its special programmes. The cinema initiative "KinoAufSegeln"[18] screening art house open air on the site of the Greifswalder Museumswerft, Greifswald's shipyard museum. It exists since 2015. All three are active members of the Verband für Filmkommunikation (Association for Film Communication) of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, the umbrella organisation of art house cinemas and film clubs.

Sightseeing

[edit]

Medieval churches

[edit]Among Greifswald's brick gothic churches is the Dom St. Nikolai (St. Nicholas collegiate church) in the city center, which, with its 100 meters (330 ft) tall tower, is the symbol of the city. The exact date of its founding is unknown, but the original church dates from the late 13th century. The tower was built, and an organ installed in the church, in the late 14th century. In the mid-17th century, when Greifswald was part of Swedish Pomerania, severe storm damage was repaired with support from the Swedish Crown. Neglect during the early DDR period necessitated extensive refurbishment, completed in 1989, the last full year of the DDR.

The St.-Marien-Kirche (St. Mary's Church), built adjacent to the Old Town marketplace in the mid-13th century, contains ground-level brick walls four and one-half meters (14 ft) thick. Medieval murals depicting scenes from the Passion of Christ were restored in 1977–84. The church organ, known as the Marienorgel (St. Mary's Organ), was installed by the Stralsund organ builder Friedrich Mehmel in 1866, replacing an earlier instrument. It features 37 registers.

On the west side of the Old Town stands the St.-Jacobi-Kirche (St. James's Church), dating from the early 13th century. In 1400 it was rebuilt to contain a nave and two transepts, requiring the addition of four buttresses. The original half-timbered tower, heavily damaged in a 1955 fire, was rebuilt in brick.

Stolpersteine

[edit]

Stolpersteine, part of the European Stolperstein (literally "stumbling stone") memorial project, are scattered around Greifswald. The brass plaques, engraved with the names of Jewish residents who were murdered in the Holocaust, are embedded in the sidewalk in front of houses where they once lived. Some of the Stolpersteine in Greifswald mark the nationwide November 9, 1938, Kristallnacht pogroms in which members of the Nazi SA and SS murdered many German Jews, vandalized Jewish property and burned down synagogues – including the Greifswald Synagogue, dating from 1787. In 2012 all the 13 Stolpersteine were stolen, presumably by pro-Nazi extremists. The following year (2013) they were replaced.[19][20]

A memorial plaque was installed on the site of the synagogue in 2008 in a ceremony attended by German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

- Alfried Krupp Wissenschaftskolleg Greifswald (Alfried Krupp Institute for Advanced Study)[21][22]

- Ferdinand Sauerbruch Street[23][24]

Transport

[edit]

According to a 2009 study, 44% of all people in Greifswald use their bicycle for daily transport within the city, which, at the time, was the highest rate in Germany.[25] There are also public local and regional bus operators. Local buses are run by SWG (Stadtwerke Greifswald).

Greifswald is situated at an equal distance of about 250 km (160 mi) to Germany's two largest cities, Berlin and Hamburg, which can be reached via the Autobahn 20 by car in about two hours. There are also train connections to and from Hamburg (via Stralsund and Rostock), and Berlin. The popular summer tourist destinations Usedom and Rügen can be reached both by car and train.

Greifswald railway station connects Greifswald with Stralsund, Züssow, Usedom, Angermünde, Eberswalde, Berlin and Szczecin (through Pasewalk). The station is also served by ICE and EuroCity services to cities in Germany and the Czech Republic.

The nearest airports to the city are Berlin Brandenburg Airport and Solidarity Szczecin–Goleniów Airport.

Greifswald has a port on the Baltic Sea as well as several marinas. The historic city centre is about 3 kilometres (2 miles) off the shore, and can be reached by yachts and small boats on the river Ryck. The Bay of Greifswald is a popular place for sailing and surfing, with Germany's two largest islands, Rügen and Usedom, just off the coast.

Notable people

[edit]

Early Times

[edit]- Bartholomäus Sastrow (1520–1603), mayor of Stralsund and autobiographer

- Sibylla Schwarz (1621–1638), poet

- Count Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld (1651–1722), Swedish field marshal

- Christian Thomsen Carl (1676–1713), a Danish naval officer, saved the town council's archives

- Joh. Chr. Andreas Mayer (1747–1801), physician

- Christian Wilhelm Ahlwardt (1760–1830), philologist

- Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), Romantic painter.[26]

- Karl Schildener (1777–1843), lawyer and local historian

- Ludwig Julius Caspar Mende (1779–1832), gynecologist, obstetrician and coroner

- Friedrich Christian Rosenthal (1780–1829), anatomist

- Adolph Wilhelm Otto (1786–1845), anatomist

19th C.

[edit]- Heinrich Eddelien (1802–1852), a Danish history painter

- Johann Karl Rodbertus (1805–1875), economist and socialist.[27]

- Edmund Hoefer (1819–1882), novelist and literary critic.[28]

- Wilhelm Ahlwardt (1828–1909), orientalist

- Rudolf Schirmer (1831–1896), ophthalmologist

- Heinrich Heydemann (1842–1889), classical philologist and archaeologist

- Elisabeth of Wied (1843–1916) first queen of Romania as the wife of King Carol I.[29]

- Hans Hartwig von Beseler (1850–1921), WWI Colonel general

- Max Lenz (1850–1932), historian

- Heinrich Bandlow (1855–1933), author, writing in Standard as well as in Low German

- Otto Schirmer (1864–1918), ophthalmologist

- Georg Engel (1866–1931), writer, dramatist and literary critic

- Percival Pollard (1869–1911), literary critic, novelist and short story writer

- Ludwig Tessnow (1872–1904), child serial killer

- Gertrud Berger (1876–1949), landscape painter who lived here

- Konrad Haenisch (1876–1925), journalist, editor and politician

- Friedrich Baethgen (1890–1972), historian, specialized in medieval studies

- Heinrich Zimmer (1890–1943), Indologist and historian of South Asian art

- Hans Fallada (1893–1947), author

- Kurt Wolff (1895–1917), WWI flying ace

20th C.

[edit]- Wolfgang Koeppen (1906–1996), author

- Magnus von Braun (1919–2003), chemical engineer, aviator and rocket scientist

- Gerhard Gentzen (1909–1945), mathematician and logician

- Ray Guillery FRS (1929–2017), physiologist and neuroanatomist

- Josef Sommer (born 1934), actor

- Doris Gercke (1937–2025), writer of crime thrillers

- Hans Lüssow (born 1942), naval officer, Vice Admiral of the German navy, inspector of the navy

- Lutz Feldt (born 1945), naval officer, Vice Admiral of the German navy, inspector of the navy

- Joachim Dreifke (born 1952), rower, medallist in the 1976 and 1980 Summer Olympics

- Cornelia Linse (born 1959), rower and medallist in the 1980 Summer Olympics

- Caren Metschuck (born 1963), swimmer, gold medalist at the 1980 Summer Olympics

- Martin Jankowski (born 1965), author

- Susanne Wiest (born 1967), activist for the unconditional basic income

- Jarkko Martikainen (born 1970), a Finnish singer, songwriter and member of the rock band YUP

- Alexander Kowalski (born 1978), techno music artist

- Robin Szolkowy, (born 1979), pair figure skater and twice Olympic bronze medalist

- Judith Schalansky (born 1980), writer, book designer and publisher

- Sebastian Sylvester (born 1980), former middleweight boxing champion

- Luise Amtsberg (born 1984), politician, member of the Bundestag for Alliance 90/The Greens.

- Franz-Robert Liskow (born 1987), politician

- Verena Schott (born 1989), Paralympic swimmer and Paralympic medal winner.

- Toni Kroos (born 1990), former footballer for Real Madrid and Germany national football team

- Felix Kroos (born 1991), former footballer and brother of Toni Kroos

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Kommunalwahlen in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Ergebnisse der Bürgermeisterwahlen, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Landesamt für innere Verwaltung, accessed 13 November 2022.

- ^ "Alle politisch selbständigen Gemeinden mit ausgewählten Merkmalen am 31.12.2023" (in German). Federal Statistical Office of Germany. 28 October 2024. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Normales et records climatologiques 1991–2020 à Greifswald" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ a b "No Name". Greifswald. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Langer, Herbert (2003). "Die Anfänge des Garnisionswesens in Pommern". In Asmus, Ivo; Droste, Heiko; Olesen, Jens E. (eds.). Gemeinsame Bekannte: Schweden und Deutschland in der Frühen Neuzeit (in German). Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 403. ISBN 3-8258-7150-9.

- ^ Langer, Herbert (2003). "Die Anfänge des Garnisionswesens in Pommern". In Asmus, Ivo; Droste, Heiko; Olesen, Jens E. (eds.). Gemeinsame Bekannte: Schweden und Deutschland in der Frühen Neuzeit (in German). Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 397. ISBN 3-8258-7150-9.

- ^ Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, Tom II (in Polish). Warszawa. 1881. p. 883.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Felix Schönrock's studies in: Frank Braun, Stefan Kroll, Städtesystem und Urbanisierung im Ostseeraum in der frühen Neuzeit: Wirtschaft, Baukultur und historische Informationssysteme: Beiträge des wissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums in Wismar vom 4. Und 5. September 2003, 2004, pp.184ff, ISBN 3-8258-7396-X, 9783825873967, [1]

- ^ S. Wierzchosławski, Polskie organizacje studenckie na uniwersytecie w Gryfii w drugiej połowie XIX i początkach XX wieku, Studia Historica Slavo- Germanica T. X — 1981, s. 127 – 140

- ^ Die Universität Greifswald in der Bildungslandschaft des Ostseeraums, page 372 Dirk Alvermann, Nils Jörn, Jens E. Olesen

- ^ a b Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ Siehe Handelsblatt: https://www.handelsblatt.com/news/Default.aspx?_p=302919&_t=ft&_b=1245899

- ^ Study shows: Greifswald is Germany's 'youngest city'

- ^ "Städtepartnerschaften". greifswald.de (in German). Greifswald. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- ^ "Städtefreundschaften". greifswald.de (in German). Greifswald. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- ^ "Home". casablanca-greifswald.de.

- ^ "Kino auf Segeln". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ^ Nach Diebstahl: Greifswalder Stolpersteine werden neu verlegt. 2013. Ostsee Zeitung. 15 May.

- ^ GERMANY-WWII-HISTORY-NAZIS-JEWS-STUMBLING STONES.

- ^ Lev Golinkin. 2022 (interactive map). Monuments and Streets Named After Nazis Worldwide. Forward

- ^ Tomasz Kamusella. 2019. Krupp in Greifswald: On the Perils of Forgetting about the Holocaust. New Eastern Europe. 18 June.

- ^ Lev Golinkin. 2022 (interactive map). Monuments and Streets Named After Nazis Worldwide. Forward

- ^ Gerhard Baader, Susan E. Lederer, Morris Low, Florian Schmaltz and Alexander V. Schwerin. 2005. Pathways to Human Experimentation, 1933-1945: Germany, Japan, and the United States (pp 205-231). In: Carola Sachse and Mark Walker, eds. Politics and Science in Wartime: Comparative International Perspectives on the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (Ser: Osiris, 2nd Series, Vol. 20). Washington DC: Georgetown University. BMW Center for German & European Studies, p 216.

- ^ Greifswald ist Fahrradhauptstadt Deutschlands, press release 2009-10-20

- ^ . New International Encyclopedia. Vol. VIII. 1905.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 437.

- ^ . Collier's New Encyclopedia. Vol. V. 1921.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 286.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XI (9th ed.). 1880. pp. 183–184.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 577.

- Official website

(in German)

(in German) - University of Greifswald (official website) (in German)

- Pomeranian State Museum, Greifswald (official website) (in German)

- Theater Vorpommern (in German)

- Greifswald, damals und heute (in German) (private photo series on the urban agenda in the last 20 years)

Greifswald

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and physical features

Greifswald is situated in northeastern Germany within the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, specifically in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district. The city's geographic coordinates are approximately 54°05′42″N 13°23′13″E.[3] It lies roughly 30 kilometers southeast of Stralsund and about 200 kilometers north of Berlin, near the Baltic Sea coast.[4] The urban area occupies a compact footprint of around 50.5 square kilometers, encompassing the historic core along the Ryck River, which flows northward through the city and empties into the Greifswalder Bodden, a shallow brackish lagoon extending into the Baltic Sea.[5] This riverine position has historically facilitated trade and fishing, with the Bodden providing sheltered waters. The municipality also includes the islands of Koos and Riems in the Bodden. The physical terrain is predominantly flat and low-lying, with average elevations of about 5 meters above sea level and maximum heights rarely surpassing 20 meters in the vicinity.[6] [7] The surrounding landscape features coastal marshes, reed-fringed shores, and meadows typical of the Pomeranian bodden region, rendering it vulnerable to sea-level rise and flooding.[8]