Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Allergic rhinitis

View on Wikipedia| Allergic rhinitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hay fever, pollenosis |

| |

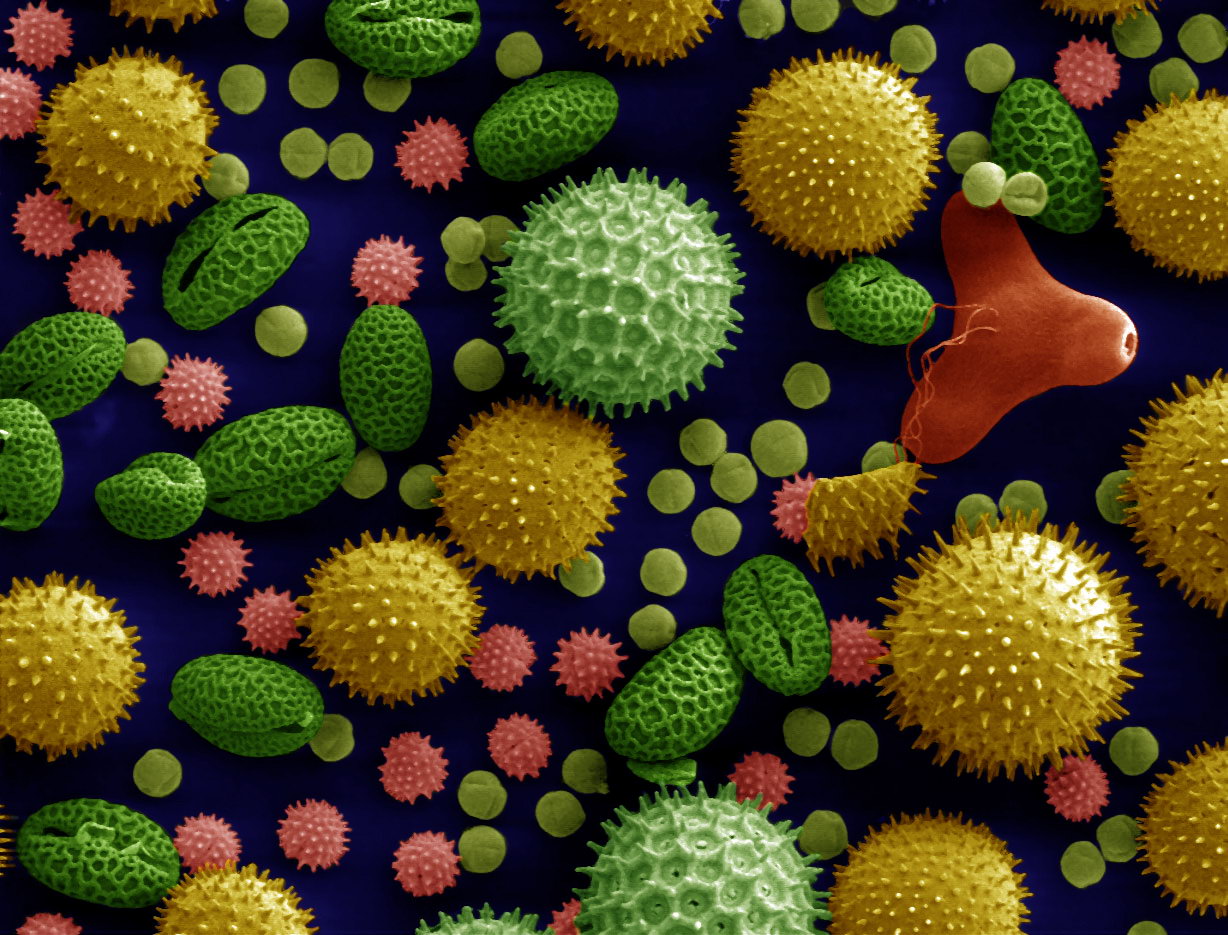

| SEM Microscope image of pollen grains from a variety of common plants: sunflower (Helianthus annuus), morning glory (Ipomoea purpurea), prairie hollyhock (Sidalcea malviflora), oriental lily (Lilium auratum), evening primrose (Oenothera fruticosa), and castor bean (Ricinus communis). | |

| Specialty | Allergy and immunology |

| Symptoms | Stuffy itchy nose, sneezing, red, itchy, and watery eyes, swelling around the eyes, itchy ears[1] |

| Usual onset | 20 to 40 years old[2] |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors[3] |

| Risk factors | Asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, skin prick test, blood tests for specific antibodies[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Common cold[3] |

| Prevention | Exposure to animals early in life[3] |

| Medication | Nasal steroids, antihistamines such as loratadine, cromolyn sodium, leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast, allergen immunotherapy[5][6] |

| Frequency | ~20% (Western countries)[2][7] Approximately 10% to 40% of the global population[8] |

Allergic rhinitis, of which the seasonal type is called hay fever, is a type of inflammation in the nose that occurs when the immune system overreacts to allergens in the air.[6] It is classified as a type I hypersensitivity reaction.[9] Signs and symptoms include a runny or stuffy nose, sneezing, red, itchy, and watery eyes, and swelling around the eyes.[1] The fluid from the nose is usually clear.[2] Symptom onset is often within minutes following allergen exposure, and can affect sleep and the ability to work or study.[2][10] Some people may develop symptoms only during specific times of the year, often as a result of pollen exposure.[3] Many people with allergic rhinitis also have asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, or atopic dermatitis.[2]

Allergic rhinitis is typically triggered by environmental allergens such as pollen, pet hair, dust mites, or mold.[3] Inherited genetics and environmental exposures contribute to the development of allergies.[3] Growing up on a farm and having multiple older siblings are associated with a reduction of this risk.[2] The underlying mechanism involves IgE antibodies that attach to an allergen, and subsequently result in the release of inflammatory chemicals such as histamine from mast cells.[2] It causes mucous membranes in the nose, eyes and throat to become inflamed and itchy as they work to eject the allergen.[11] Diagnosis is typically based on a combination of symptoms and a skin prick test or blood tests for allergen-specific IgE antibodies.[4] These tests, however, can give false positives.[4] The symptoms of allergies resemble those of the common cold; however, they often last for more than two weeks and, despite the common name, typically do not include a fever.[3]

Exposure to animals early in life might reduce the risk of developing these specific allergies.[3] Several different types of medications reduce allergic symptoms, including nasal steroids, intranasal antihistamines such as olopatadine or azelastine, 2nd generation oral antihistamines such as loratadine, desloratadine, cetirizine, or fexofenadine; the mast cell stabilizer cromolyn sodium, and leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast.[12][5] Oftentimes, medications do not completely control symptoms, and they may also have side effects.[2] Exposing people to larger and larger amounts of allergen, known as allergen immunotherapy, is often effective and is used when first line treatments fail to control symptoms.[6] The allergen can be given as an injection under the skin or as a tablet under the tongue.[6] Treatment typically lasts three to five years, after which benefits may be prolonged.[6]

Allergic rhinitis is the type of allergy that affects the greatest number of people.[13] In Western countries, between 10 and 30% of people are affected in a given year.[2][7] It is most common between the ages of twenty and forty.[2] The first accurate description is from the 10th-century physician Abu Bakr al-Razi.[14] In 1859, Charles Blackley identified pollen as the cause.[15] In 1906, the mechanism was determined by Clemens von Pirquet.[13] The link with hay came about due to an early (and incorrect) theory that the symptoms were brought about by the smell of new hay.[16][17]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The characteristic symptoms of allergic rhinitis are: rhinorrhea (excess nasal secretion), itching, sneezing fits, and nasal congestion/obstruction.[18] Characteristic physical findings include conjunctival swelling and erythema, eyelid swelling with Dennie–Morgan folds, lower eyelid venous stasis (rings under the eyes known as "allergic shiners"), swollen nasal turbinates, and middle ear effusion.[19] Nasal endoscopy may show findings such as pale and boggy inferior turbinates from mucosal edema, stringy mucus throughout the nasal cavities, and cobblestoning.[20][21]

There can also be behavioral signs; in order to relieve the irritation or flow of mucus, people may wipe or rub their nose with the palm of their hand in an upward motion: an action known as the "nasal salute" or the "allergic salute". This may result in a crease running across the nose (or above each nostril if only one side of the nose is wiped at a time), commonly referred to as the "transverse nasal crease", and can lead to permanent physical deformity if repeated enough.[22]

People might also find that cross-reactivity occurs.[23] For example, people allergic to birch pollen may also find that they have an allergic reaction to the skin of apples or potatoes.[24] A clear sign of this is the occurrence of an itchy throat after eating an apple or sneezing when peeling potatoes or apples. This occurs because of similarities in the proteins of the pollen and the food.[25] There are many cross-reacting substances. Hay fever is not a true fever, meaning it does not cause a core body temperature in the fever over 37.5–38.3 °C (99.5–100.9 °F).[citation needed]

Cause

[edit]Pollen is often considered as a cause of allergic rhinitis, hence called hay fever (See sub-section below).[citation needed]

Predisposing factors to allergic rhinitis include eczema (atopic dermatitis) and asthma. These three conditions can often occur together which is referred to as the atopic triad.[26] Additionally, environmental exposures such as air pollution and maternal tobacco smoking can increase an individual's chances of developing allergies.[26]

Pollen-related causes

[edit]Allergic rhinitis triggered by the pollens of specific seasonal plants is commonly known as "hay fever", because it is most prevalent during haying season. However, it is possible to have allergic rhinitis throughout the year. The pollen that causes hay fever varies between individuals and from region to region; in general, the tiny, hardly visible pollens of wind-pollinated plants are the predominant cause. The study of the dispersion of these bioaerosols is called Aerobiology. Pollens of insect-pollinated plants are too large to remain airborne and pose no risk. Examples of plants commonly responsible for hay fever include:

- Trees: such as pine (Pinus), mulberry (Morus), birch (Betula), alder (Alnus), cedar (Cedrus), hazel (Corylus), hornbeam (Carpinus), horse chestnut (Aesculus), willow (Salix), poplar (Populus), plane (Platanus), linden/lime (Tilia), and olive (Olea). In northern latitudes, birch is considered to be the most common allergenic tree pollen, with an estimated 15–20% of people with hay fever sensitive to birch pollen grains. A major antigen in these is a protein called Bet V I. Olive pollen is most predominant in Mediterranean regions. Hay fever in Japan is caused primarily by sugi (Cryptomeria japonica) and hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa) tree pollen.

- "Allergy friendly" trees include: female ash, red maple, yellow poplar, dogwood, magnolia, double-flowered cherry, fir, spruce, and flowering plum.[27]

- Grasses (Family Poaceae): especially ryegrass (Lolium sp.) and timothy (Phleum pratense). An estimated 90% of people with hay fever are allergic to grass pollen.

- Weeds: ragweed (Ambrosia), plantain (Plantago), nettle/parietaria (Urticaceae), mugwort (Artemisia Vulgaris), Fat hen (Chenopodium), and sorrel/dock (Rumex)

Allergic rhinitis may also be caused by allergy to Balsam of Peru, which is in various fragrances and other products.[28][29][30]

Genetic factors

[edit]The causes and pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis are hypothesized to be affected by both genetic and environmental factors, with many recent studies focusing on specific loci that could be potential therapeutic targets for the disease. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified a number of different loci and genetic pathways that seem to mediate the body's response to allergens and promote the development of allergic rhinitis, with some of the most promising results coming from studies involving single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the interleukin-33 (IL-33) gene.[31][32] The IL-33 protein that is encoded by the IL-33 gene is part of the interleukin family of cytokines that interact with T-helper 2 (Th2) cells, a specific type of T cell. Th2 cells contribute to the body's inflammatory response to allergens, with specific ST2 receptors—also known as IL1RL1—on these cells binding to the ligand IL-33. This IL-33/ST2 signaling pathway has been found to be one of the main genetic determinants in bronchial asthma pathogenesis, and because of the pathological linkage between asthma and rhinitis, the experimental focus of IL-33 has now turned to its role in the development of allergic rhinitis in humans and mouse models.[33] Recently, it was found that allergic rhinitis patients expressed higher levels of IL-33 in their nasal epithelium and had a higher concentration of ST2 serum in nasal passageways following their exposure to pollen and other allergens, indicating that this gene and its associated receptor are expressed at a higher rate in allergic rhinitis patients.[34] In a 2020 study on polymorphisms of the IL-33 gene and their link to allergic rhinitis within the Han Chinese population, researchers found that five SNPs specifically contributed to the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis, with three of those five SNPs previously identified as genetic determinants for asthma.[35]

Another study focusing on Han Chinese children found that certain SNPs in the protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor 22 (PTPN22) gene and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) gene can be associated with childhood allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma.[36] The encoded PTPN22 protein, which is found primarily in lymphoid tissue, acts as a post-translational regulator by removing phosphate groups from targeted proteins. Importantly, PTPN22 can affect the phosphorylation of T cell responses, and thus the subsequent proliferation of the T cells. As mentioned earlier, T cells contribute to the body's inflammatory response in a variety of ways, so any changes to the cells' structure and function can have potentially deleterious effects on the body's inflammatory response to allergens. To date, one SNP in the PTPN22 gene has been found to be significantly associated with allergic rhinitis onset in children. On the other hand, CTLA-4 is an immune-checkpoint protein that helps mediate and control the body's immune response to prevent overactivation. It is expressed only in T cells as a glycoprotein for the Immunoglobulin (Ig) protein family, also known as antibodies. There have been two SNPs in CTLA-4 that were found to be significantly associated with childhood allergic rhinitis. Both SNPs most likely affect the associated protein's shape and function, causing the body to exhibit an overactive immune response to the posed allergen. The polymorphisms in both genes are only beginning to be examined, therefore more research is needed to determine the severity of the impact of polymorphisms in the respective genes.[citation needed]

Finally, epigenetic alterations and associations are of particular interest to the study and ultimate treatment of allergic rhinitis. Specifically, microRNAs (miRNA) are hypothesized to be imperative to the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis due to the post-transcriptional regulation and repression of translation in their mRNA complement. Both miRNAs and their common carrier vessel exosomes have been found to play a role in the body's immune and inflammatory responses to allergens. miRNAs are housed and packaged inside of exosomes until they are ready to be released into the section of the cell that they are coded to reside and act. Repressing the translation of proteins can ultimately repress parts of the body's immune and inflammatory responses, thus contributing to the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis and other autoimmune disorders. There are many miRNAs that have been deemed potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of allergic rhinitis by many different researchers, with the most widely studied being miR-133, miR-155, miR-205, miR-498, and let-7e.[32][37][38][39]

Air pollution

[edit]Numerous studies confirm that ambient air pollution particularly traffic-related pollutants like nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and fine particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) is significantly associated with both the prevalence and severity of allergic rhinitis. One Taiwanese study found that a 10 ppb increase in NOx corresponded to an 11% higher odds of physician‑diagnosed allergic rhinitis, with smaller yet significant associations for CO, SO2, and PM10.[40] Chinese meta-analysis data echoed this trend: increases in SO2 (OR ≈ 1.03), NO2 (OR ≈ 1.11), PM10 (OR ≈ 1.02), and PM2.5 (OR ≈ 1.15) all correlated with heightened risk of childhood allergic rhinitis, while ozone exposure showed no significant association.[41]

Air pollutants impair the respiratory epithelial barrier, increasing permeability and inflammation. This occurs through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, immune modulation, and epigenetic changes. Diesel exhaust particles (DEP), for example, have been shown to enhance allergic inflammation by boosting eosinophil activation when allergens are present. Meanwhile, damaged nasal mucosa facilitates deeper allergen penetration, intensifying rhinitis symptoms.[42] Urbanization, vehicle emissions, and fossil fuel combustion have accelerated in recent decades, coinciding with a steady rise in allergic rhinitis prevalence. For instance, in Southeast Asia and parts of Latin America, higher AR rates align strongly with poorer air quality.[43]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The pathophysiology of allergic rhinitis involves Th2 Helper T cell and IgE mediated inflammation with overactive function of the adaptive and innate immune systems.[12] The process begins when an aeroallergen penetrates the nasal mucosal barrier. This barrier may be more permeable in susceptible individuals. The allergen is then engulfed by an antigen presenting cell (APC) (such as a dendritic cell).[12] The APC then presents the antigen to a Naive CD4+ helper T cell stimulating it to differentiate into a Th2 helper T cell. The Th2 helper T cell then secretes inflammatory cytokines including IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-14, and IL-31. These inflammatory cytokines stimulate B cells to differentiate into plasma cells and release allergen specific IgE immunoglobulins.[12] The IgE immunoglobulins attach to mast cells. The inflammatory cytokines also recruit inflammatory cells such as basophils, eosinophils and fibroblasts to the area.[12] The person is now sensitized, and upon re-exposure to the allergen, mast cells with allergen specific IgE will bind the allergens and release inflammatory molecules including histamine, leukotrienes, platelet activating factor, prostaglandins and thromboxane with these inflammatory molecules' local effects on blood vessels (dilation), mucous glands (secrete mucous) and sensory nerves (activation) leading to the clinical signs and symptoms of allergic rhinitis.[12]

Disruption of the nasal mucosal epithelial barrier may also release alarmins (a type of damage associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecule) such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin, IL-25 and IL-33 which activate group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) which then also releases inflammatory cytokines leading to activation of immune cells.[12]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Allergy testing may reveal the specific allergens to which an individual is sensitive. Skin testing is the most common method of allergy testing.[44] [failed verification] This may include a patch test to determine if a particular substance is causing the rhinitis, or an intradermal, scratch, or other test. Less commonly, the suspected allergen is dissolved and dropped onto the lower eyelid as a means of testing for allergies. This test should be done only by a physician, since it can be harmful if done improperly. In some individuals not able to undergo skin testing (as determined by the doctor), the RAST blood test may be helpful in determining specific allergen sensitivity. Peripheral eosinophilia can be seen in differential leukocyte count.[citation needed]

Allergy testing is not definitive. At times, these tests can reveal positive results for certain allergens that are not actually causing symptoms, and can also not pick up allergens that do cause an individual's symptoms. The intradermal allergy test is more sensitive than the skin prick test, but is also more often positive in people that do not have symptoms to that allergen.[45]

Even if a person has negative skin-prick, intradermal and blood tests for allergies, they may still have allergic rhinitis, from a local allergy in the nose. This is called local allergic rhinitis.[46] Specialized testing is necessary to diagnose local allergic rhinitis.[47]

Classification

[edit]- Seasonal allergic rhinitis (hay fever): Caused by seasonal peaks in the airborne load of pollens.

- Perennial allergic rhinitis (nonseasonal allergic rhinitis; atopic rhinitis): Caused by allergens present throughout the year (e.g., dander).

Allergic rhinitis may be seasonal, perennial, or episodic.[10] Seasonal allergic rhinitis occurs in particular during pollen seasons. It does not usually develop until after 6 years of age. Perennial allergic rhinitis occurs throughout the year. This type of allergic rhinitis is commonly seen in younger children.[48]

Allergic rhinitis may also be classified as mild-intermittent, moderate-severe intermittent, mild-persistent, and moderate-severe persistent. Intermittent is when the symptoms occur <4 days per week or <4 consecutive weeks. Persistent is when symptoms occur >4 days/week and >4 consecutive weeks. The symptoms are considered mild with normal sleep, no impairment of daily activities, no impairment of work or school, and if symptoms are not troublesome. Severe symptoms result in sleep disturbance, impairment of daily activities, and impairment of school or work.[49]

Local allergic rhinitis

[edit]Local allergic rhinitis is an allergic reaction in the nose to an allergen, without systemic allergies. So skin-prick and blood tests for allergy are negative, but there are IgE antibodies produced in the nose that react to a specific allergen. Intradermal skin testing may also be negative.[47]

The symptoms of local allergic rhinitis are the same as the symptoms of allergic rhinitis, including symptoms in the eyes. Just as with allergic rhinitis, people can have either seasonal or perennial local allergic rhinitis. The symptoms of local allergic rhinitis can be mild, moderate, or severe. Local allergic rhinitis is associated with conjunctivitis and asthma.[47]

In one study, about 25% of people with rhinitis had local allergic rhinitis.[50] In several studies, over 40% of people having been diagnosed with nonallergic rhinitis were found to actually have local allergic rhinitis.[46] Steroid nasal sprays and oral antihistamines have been found to be effective for local allergic rhinitis.[47]

As of 2014, local allergenic rhinitis had mostly been investigated in Europe; in the United States, the nasal provocation testing necessary to diagnose the condition was not widely available.[51]: 617

Prevention

[edit]Prevention often focuses on avoiding specific allergens that cause an individual's symptoms. These methods include not having pets, not having carpets or upholstered furniture in the home, and keeping the home dry.[52] Specific anti-allergy zippered covers on household items like pillows and mattresses have also proven to be effective in preventing dust mite allergies.[44]

Studies have shown that growing up on a farm and having many older siblings are associated with a reduction in individual's risk for developing allergic rhinitis.[2]

Studies in young children have shown that there is higher risk of allergic rhinitis in those who have early exposure to foods or formula or heavy exposure to cigarette smoking within the first year of life.[53][54]

Treatment

[edit]The goal of rhinitis treatment is to prevent or reduce the symptoms caused by the inflammation of affected tissues. Measures that are effective include avoiding the allergen.[18] Intranasal corticosteroids are the preferred medical treatment for persistent symptoms, with other options if this is not effective.[18] Second line therapies include antihistamines, decongestants, cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and nasal irrigation.[18] Antihistamines by mouth are suitable for occasional use with mild intermittent symptoms.[18] Mite-proof covers, air filters, and withholding certain foods in childhood do not have evidence supporting their effectiveness.[18]

Antihistamines

[edit]Antihistamine drugs can be taken orally and nasally to control symptoms such as sneezing, rhinorrhea, itching, and conjunctivitis.[55]

It is best to take oral antihistamine medication before exposure, especially for seasonal allergic rhinitis. In the case of nasal antihistamines like azelastine antihistamine nasal spray, relief from symptoms is experienced within 15 minutes allowing for a more immediate 'as-needed' approach to dosage. There is not enough evidence of antihistamine efficacy as an add-on therapy with nasal steroids in the management of intermittent or persistent allergic rhinitis in children, so its adverse effects and additional costs must be considered.[56]

Ophthalmic antihistamines (such as azelastine in eye drop form and ketotifen) are used for conjunctivitis, while intranasal forms are used mainly for sneezing, rhinorrhea, and nasal pruritus.[57]

Antihistamine drugs can have undesirable side-effects, the most notable one being drowsiness in the case of oral antihistamine tablets. First-generation antihistamine drugs such as diphenhydramine cause drowsiness, while second- and third-generation antihistamines such as fexofenadine and loratadine are less likely to.[57][58]

Pseudoephedrine is also indicated for vasomotor rhinitis. It is used only when nasal congestion is present and can be used with antihistamines. In the United States, oral decongestants containing pseudoephedrine must be purchased behind the pharmacy counter in an effort to prevent the manufacturing of methamphetamine.[57] Desloratadine/pseudoephedrine can also be used for this condition[citation needed]

Steroids

[edit]Intranasal corticosteroids are used to control symptoms associated with sneezing, rhinorrhea, itching, and nasal congestion.[26] Steroid nasal sprays are effective and safe, and may be effective without oral antihistamines. They take several days to act and so must be taken continually for several weeks, as their therapeutic effect builds up with time.[citation needed]

In 2013, a study compared the efficacy of mometasone furoate nasal spray to betamethasone oral tablets for the treatment of people with seasonal allergic rhinitis and found that the two have virtually equivalent effects on nasal symptoms in people.[59]

Systemic steroids such as prednisone tablets and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide or glucocorticoid (such as betamethasone) injection are effective at reducing nasal inflammation, [citation needed] but their use is limited by their short duration of effect and the side-effects of prolonged steroid therapy.[60]

Others

[edit]Other measures that may be used second line include: decongestants, cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and nonpharmacologic therapies such as nasal irrigation.[18]

Topical decongestants may also be helpful in reducing symptoms such as nasal congestion, but should not be used for long periods, as stopping them after protracted use can lead to a rebound nasal congestion called rhinitis medicamentosa.[citation needed]

For nocturnal symptoms, intranasal corticosteroids can be combined with nightly oxymetazoline, an adrenergic alpha-agonist, or an antihistamine nasal spray without risk of rhinitis medicamentosa.[61]

Nasal saline irrigation (a practice where salt water is poured into the nostrils), may have benefits in both adults and children in relieving the symptoms of allergic rhinitis and it is unlikely to be associated with adverse effects.[62]

Allergen immunotherapy

[edit]Allergen immunotherapy, also called desensitization, treatment involves administering doses of allergens to accustom the body to substances that are generally harmless (pollen, house dust mites), thereby inducing specific long-term tolerance.[63] Allergen immunotherapy is the only treatment that alters the disease mechanism.[64] Immunotherapy can be administered orally (as sublingual tablets or sublingual drops), or by injections under the skin (subcutaneous). Subcutaneous immunotherapy is the most common form and has the largest body of evidence supporting its effectiveness.[65]

Alternative medicine

[edit]There are no forms of complementary or alternative medicine that are evidence-based for allergic rhinitis.[44] Therapeutic efficacy of alternative treatments such as acupuncture and homeopathy is not supported by available evidence.[66][67] While some evidence shows that acupuncture is effective for rhinitis, specifically targeting the sphenopalatine ganglion acupoint, these trials are still limited.[68] Overall, the quality of evidence for complementary-alternative medicine is not strong enough to be recommended by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.[44][69]

Epidemiology

[edit]Allergic rhinitis is the type of allergy that affects the greatest number of people.[13] In Western countries, between 10 and 30 percent of people are affected in a given year.[2] It is most common between the ages of twenty and forty.[2]

History

[edit]The first accurate description is from the 10th century physician Rhazes.[14] Pollen was identified as the cause in 1859 by Charles Blackley.[15] In 1906 the mechanism was determined by Clemens von Pirquet.[13] The link with hay came about due to an early (and incorrect) theory that the symptoms were brought about by the smell of new hay.[16][17] Although the scent per se is irrelevant, the correlation with hay checks out, as peak hay-harvesting season overlaps with peak pollen season, and hay-harvesting work puts people in close contact with seasonal allergens.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Environmental Allergies: Symptoms". NIAID. April 22, 2015. Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wheatley LM, Togias A (January 2015). "Clinical practice. Allergic rhinitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (5): 456–63. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1412282. PMC 4324099. PMID 25629743.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Cause of Environmental Allergies". NIAID. April 22, 2015. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Environmental Allergies: Diagnosis". NIAID. May 12, 2015. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "Environmental Allergies: Treatments". NIAID. April 22, 2015. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Immunotherapy for Environmental Allergies". NIAID. May 12, 2015. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Dykewicz MS, Hamilos DL (February 2010). "Rhinitis and sinusitis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 125 (2 Suppl 2): S103-15. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.989. PMID 20176255.

- ^ Siti Sarah, Che Othman; Mohd Ashari, Noor Suryani (October 2024). "Exploration of Allergic Rhinitis: Epidemiology, Predisposing Factors, Clinical Manifestations, Laboratory Characteristics, and Emerging Pathogenic Mechanisms". Cureus. 16 (10) e71409. doi:10.7759/cureus.71409. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 11558229. PMID 39539885.

- ^ "Types of Allergic Diseases". June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Covar R (2018). "Allergic Disorders". Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics (24th ed.). NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1-259-86290-8.

- ^ "Allergic Rhinitis (Hay Fever): Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bernstein, Jonathan A.; Bernstein, Joshua S.; Makol, Richika; Ward, Stephanie (March 12, 2024). "Allergic Rhinitis: A Review". JAMA. 331 (10): 866–877. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.0530. PMID 38470381.

- ^ a b c d Fireman P (2002). Pediatric otolaryngology vol 2 (4th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: W. B. Saunders. p. 1065. ISBN 978-99976-198-4-6. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Colgan R (2009). Advice to the young physician on the art of medicine. New York: Springer. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4419-1034-9. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Justin Parkinson (July 1, 2014). "John Bostock: The man who 'discovered' hay fever". BBC News Magazine. Archived from the original on July 31, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Hall M (May 19, 1838). "Dr. Marshall Hall on Diseases of the Respiratory System; III. Hay Asthma". The Lancet. 30 (768): 245. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)95895-2. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

With respect to what is termed the exciting cause of the disease, since the attention of the public has been turned to the subject an idea has very generally prevailed, that it is produced by the effluvium from new hay, and it has hence obtained the popular name of hay fever. [...] the effluvium from hay has no connection with the disease.

- ^ a b History of Allergy. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. 2014. p. 62. ISBN 978-3-318-02195-0. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sur DK, Plesa ML (December 2015). "Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis". American Family Physician. 92 (11): 985–92. PMID 26760413. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Valet RS, Fahrenholz JM (2009). "Allergic rhinitis: update on diagnosis". Consultant. 49: 610–3. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010.

- ^ Ziade, Georges K.; Karami, Reem A.; Fakhri, Ghina B.; Alam, Elie S.; Hamdan, Abdul latif; Mourad, Marc M.; Hadi, Usama M. (2016). "Reliability assessment of the endoscopic examination in patients with allergic rhinitis". Allergy & Rhinology. 7 (3): e135 – e138. doi:10.2500/ar.2016.7.0176. ISSN 2152-6575. PMC 5244268. PMID 28107144.

- ^ La Mantia, Ignazio; Andaloro, Claudio (October 2017). "Cobblestone Appearance of the Nasopharyngeal Mucosa". The Eurasian Journal of Medicine. 49 (3): 220–221. doi:10.5152/eurasianjmed.2017.17257. ISSN 1308-8734. PMC 5665636. PMID 29123450.

- ^ Pray WS (2005). Nonprescription Product Therapeutics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7817-3498-1.

- ^ Czaja-Bulsa G, Bachórska J (December 1998). "[Food allergy in children with pollinosis in the Western sea coast region]" [Food allergy in children with pollinosis in the Western sea coast region]. Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski (in Polish). 5 (30): 338–40. PMID 10101519.

- ^ Yamamoto T, Asakura K, Shirasaki H, Himi T, Ogasawara H, Narita S, Kataura A (October 2005). "[Relationship between pollen allergy and oral allergy syndrome]" [Relationship between Pollen Allergy and Oral Allergy Syndrome]. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho (in Japanese). 108 (10): 971–9. doi:10.3950/jibiinkoka.108.971. PMID 16285612.

- ^ Malandain H (September 2003). "[Allergies associated with both food and pollen]" [Allergies associated with both food and pollen]. European Annals of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (in French). 35 (7): 253–6. PMID 14626714. INIST 15195402.

- ^ a b c Cahill K (2018). "Urticaria, Angioedema, and Allergic Rhinitis." 'Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (20th ed.). NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 345. ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0.

- ^ "Allergy Friendly Trees". Forestry.about.com. March 5, 2014. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Pamela Brooks (2012). The Daily Telegraph: Complete Guide to Allergies. Little, Brown Book. ISBN 978-1-4721-0394-9.

- ^ Denver Medical Times: Utah Medical Journal. Nevada Medicine. January 1, 2010. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ George Clinton Andrews; Anthony Nicholas Domonkos (July 1, 1998). Diseases of the Skin: For Practitioners and Students. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Kamekura R, Kojima T, Takano K, Go M, Sawada N, Himi T (2012). "The Role of IL-33 and Its Receptor ST2 in Human Nasal Epithelium with Allergic Rhinitis". Clin Exp Allergy. 42 (2): 218–228. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03867.x. PMID 22233535. S2CID 21799632.

- ^ a b Zhang XH, Zhang YN, Liu Z (2014). "MicroRNA in Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Allergic Rhinitis". Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 14 (2) 415. doi:10.1007/s11882-013-0415-3. PMID 24408538. S2CID 39239208.

- ^ Baumann R, Rabaszowski M, Stenin I, Tilgner L, Gaertner-Akerboom M, Scheckenbach K, Wiltfang J, Chaker A, Schipper J, Wagenmann M (2013). "Nasal Levels of Soluble IL-33R ST2 and IL-16 in Allergic Rhinitis: Inverse Correlation Trends with Disease Severity". Clin Exp Allergy. 43 (10): 1134–1143. doi:10.1111/cea.12148. PMID 24074331. S2CID 32689683.

- ^ Ran H, Xiao H, Zhou X, Guo L, Lu S (2020). "Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Haplotypes in the Interleukin-33 Gene Are Associated with a Risk of Allergic Rhinitis in the Chinese Population". Exp Ther Med. 20 (5): 102. doi:10.3892/etm.2020.9232. PMC 7506885. PMID 32973951.

- ^ Ran, He; Xiao, Hua; Zhou, Xing; Guo, Lijun; Lu, Shuang (November 2020). "Single-nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes in the interleukin-33 gene are associated with a risk of allergic rhinitis in the Chinese population". Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 20 (5): 102. doi:10.3892/etm.2020.9232. ISSN 1792-0981. PMC 7506885. PMID 32973951.

- ^ Song SH, Wang XQ, Shen Y, Hong SL, Ke, X. "Association between PTPN22/CTLA-4 Gene Polymorphism and Allergic Rhinitis with Asthma in Children". Iranian Journal of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology: 413–419.

- ^ Suojalehto H, Toskala E, Kilpeläinen M, Majuri ML, Mitts C, Lindström I, Puustinen A, Plosila T, Sipilä J, Wolff H, Alenius H (2013). "MicroRNA Profiles in Nasal Mucosa of Patients with Allergic and Nonallergic Rhinitis and Asthma". International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology. 3 (8): 612–620. doi:10.1002/alr.21179. PMID 23704072. S2CID 29759402.

- ^ Sastre B, Cañas JA, Rodrigo-Muñoz JM, del Pozo V (2017). "Novel Modulators of Asthma and Allergy: Exosomes and MicroRNAs". Front Immunol. 8: 826. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00826. PMC 5519536. PMID 28785260.

- ^ Xiao L, Jiang L, Hu Q, Li Y. "MicroRNA-133b Ameliorates Allergic Inflammation and Symptom in Murine Model of Allergic Rhinitis by Targeting NIrp3". CPB. 42 (3): 901–912.

- ^ Hwang, Bing-Fang; Jaakkola, Jouni JK; Lee, Yung-Ling; Lin, Ying-Chu; Leon Guo, Yue-liang (February 9, 2006). "Relation between air pollution and allergic rhinitis in Taiwanese schoolchildren". Respiratory Research. 7 (1): 23. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-7-23. ISSN 1465-993X. PMC 1420289. PMID 16469096.

- ^ Zhang, Shipeng; Fu, Qinwei; Wang, Shuting; Jin, Xin; Tan, Junwen; Ding, Kaixi; Zhang, Qinxiu; Li, Xinrong (September 1, 2022). "Association between air pollution and the prevalence of allergic rhinitis in Chinese children: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 43 (5): e47 – e57. doi:10.2500/aap.2022.43.220044. ISSN 1539-6304. PMID 36065105.

- ^ Kanjanawasee, Dichapong; Limjunyawong, Nathachit; Tantilipikorn, Pongsakorn (July 3, 2025). "Role of air pollution in rhinitis". Exploration of Asthma & Allergy. 3 100985. doi:10.37349/eaa.2025.100985. ISSN 2837-5076.

- ^ Rosario Filho, Nelson A.; Satoris, Rogério Aranha; Scala, Wanessa Ruiz (August 2021). "Allergic rhinitis aggravated by air pollutants in Latin America: A systematic review". The World Allergy Organization Journal. 14 (8) 100574. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100574. ISSN 1939-4551. PMC 8387759. PMID 34471459.

- ^ a b c d "American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology". Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Allergy Tests". WebMD. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Rondón C, Canto G, Blanca M (February 2010). "Local allergic rhinitis: a new entity, characterization and further studies". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 10 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e328334f5fb. PMID 20010094. S2CID 3472235.

- ^ a b c d Rondón C, Fernandez J, Canto G, Blanca M (2010). "Local allergic rhinitis: concept, clinical manifestations, and diagnostic approach". Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 20 (5): 364–71, quiz 2 p following 371. PMID 20945601. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ "Rush University Medical Center". Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- ^ Bousquet J, Reid J, van Weel C, Baena Cagnani C, Canonica GW, Demoly P, et al. (August 2008). "Allergic rhinitis management pocket reference 2008". Allergy. 63 (8): 990–6. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01642.x. PMID 18691301. S2CID 11933433.

- ^ Rondón C, Campo P, Galindo L, Blanca-López N, Cassinello MS, Rodriguez-Bada JL, et al. (October 2012). "Prevalence and clinical relevance of local allergic rhinitis". Allergy. 67 (10): 1282–8. doi:10.1111/all.12002. PMID 22913574. S2CID 22470654.

- ^ Flint PW, Haughey BH, Robbins KT, Thomas JR, Niparko JK, Lund VJ, Lesperance MM (November 28, 2014). Cummings Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-27820-1. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Prevention". nhs.uk. October 3, 2018. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ Akhouri S, House SA. Allergic Rhinitis. [Updated 2020 Nov 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538186/ Archived March 18, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Skoner DP (July 2001). "Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 108 (1 Suppl): S2-8. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.115569. PMID 11449200.

- ^ "Antihistamines for Allergies". MedlinePlus.gov. Archived from the original on March 19, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Nasser M, Fedorowicz Z, Aljufairi H, McKerrow W (July 2010). "Antihistamines used in addition to topical nasal steroids for intermittent and persistent allergic rhinitis in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (7) CD006989. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006989.pub2. PMC 7388927. PMID 20614452.

- ^ a b c May JR, Smith PH (2008). "Allergic Rhinitis". In DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke G, Wells B, Posey LM (eds.). Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1565–75. ISBN 978-0-07-147899-1.

- ^ Craun, Kari L.; Patel, Preeti; Schury, Mark P. (2024), "Fexofenadine", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32310564, retrieved August 16, 2024

- ^ Karaki M, Akiyama K, Mori N (June 2013). "Efficacy of intranasal steroid spray (mometasone furoate) on treatment of patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis: comparison with oral corticosteroids". Auris, Nasus, Larynx. 40 (3): 277–81. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2012.09.004. PMID 23127728.

- ^ Ohlander BO, Hansson RE, Karlsson KE (1980). "A comparison of three injectable corticosteroids for the treatment of patients with seasonal hay fever". The Journal of International Medical Research. 8 (1): 63–9. doi:10.1177/030006058000800111. PMID 7358206. S2CID 24169670.

- ^ Baroody FM, Brown D, Gavanescu L, DeTineo M, Naclerio RM (April 2011). "Oxymetazoline adds to the effectiveness of fluticasone furoate in the treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 127 (4): 927–34. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.037. PMID 21377716.

- ^ Head K, Snidvongs K, Glew S, Scadding G, Schilder AG, Philpott C, Hopkins C (June 2018). "Saline irrigation for allergic rhinitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (6) CD012597. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012597.pub2. PMC 6513421. PMID 29932206.

- ^ Van Overtvelt L, Batard T, Fadel R, Moingeon P (December 2006). "Mécanismes immunologiques de l'immunothérapie sublinguale spécifique des allergènes". Revue Française d'Allergologie et d'Immunologie Clinique. 46 (8): 713–720. doi:10.1016/j.allerg.2006.10.006.

- ^ Creticos P. "Subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic disease: Indications and efficacy". UpToDate. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A, Durham S (January 2007). "Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (1) CD001936. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001936.pub2. PMC 7017974. PMID 17253469.

- ^ Passalacqua G, Bousquet PJ, Carlsen KH, Kemp J, Lockey RF, Niggemann B, et al. (May 2006). "ARIA update: I—Systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine for rhinitis and asthma". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 117 (5): 1054–62. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1308. PMID 16675332.

- ^ Terr AI (2004). "Unproven and controversial forms of immunotherapy". Clinical Allergy and Immunology. 18: 703–10. PMID 15042943.

- ^ Fu Q, Zhang L, Liu Y, Li X, Yang Y, Dai M, Zhang Q (March 12, 2019). "Effectiveness of Acupuncturing at the Sphenopalatine Ganglion Acupoint Alone for Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2019 6478102. doi:10.1155/2019/6478102. PMC 6434301. PMID 30992709.

- ^ Witt CM, Brinkhaus B (October 2010). "Efficacy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of acupuncture for allergic rhinitis – An overview about previous and ongoing studies". Autonomic Neuroscience. 157 (1–2): 42–5. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2010.06.006. PMID 20609633. S2CID 31349218.

Further reading

[edit]- "Sublingual Immunotherapy (SLIT) Allergy Tablets - American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology". Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

External links

[edit]