Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Allergy

View on Wikipedia

| Allergy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hives are a common allergic symptom. | |

| Specialty | Immunology |

| Symptoms | Red eyes, itchy rash, vomiting, runny nose, shortness of breath, swelling, sneezing, and cough |

| Types | Hay fever, food allergies, atopic dermatitis, allergic asthma, anaphylaxis[1] |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, skin prick test, blood test[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Food intolerances, food poisoning[4] |

| Prevention | Early exposure to potential allergens[5] |

| Treatment | Avoiding known allergens, medications, allergen immunotherapy[6] |

| Medication | Steroids, antihistamines, epinephrine, mast cell stabilizers, antileukotrienes[6][7][8][9] |

| Frequency | Common[10] |

An allergy is an exaggerated immune response where the body mistakenly identifies an ordinarily harmless allergen as a threat.[11][12][13][14] Allergic reactions give rise to allergic diseases such as hay fever, allergic conjunctivitis, allergic asthma, atopic dermatitis, food allergies, and anaphylaxis.[1] Symptoms of allergic diseases may include red eyes, an itchy rash, sneezing, coughing, a runny nose, shortness of breath, or swelling.[15][3][4]

Common allergens include pollen, certain foods, metals, insect stings, and medications.[11][2] The development of allergies is due to genetic and environmental factors.[2] The mechanism of allergic reactions involves immunoglobulin E antibodies (IgE) binding to an allergen and then to a receptor on mast cells or basophils, where they trigger the release of inflammatory chemicals such as histamine.[16] Diagnosis is typically based on a person's medical history.[3] Further testing of the skin or blood may be useful in certain cases.[3] Positive tests, however, may not necessarily mean there is a significant allergy to the substance in question.[17]

Early exposure of children to potential allergens may be protective.[5] Treatments for allergies include avoidance of known allergens and the use of medications such as steroids and antihistamines.[6] In severe reactions, injectable adrenaline (epinephrine) is recommended.[7] Allergen immunotherapy, which gradually exposes people to larger and larger amounts of allergen, is useful for some types of allergies such as hay fever and reactions to insect bites.[6] Its use in food allergies is unclear.[6]

Allergies are common.[10] In the developed world, about 20% of people are affected by allergic rhinitis,[18] food allergy affects 10% of adults and 8% of children,[19] and about 20% have or have had atopic dermatitis at some point in time.[20] Depending on the country, about 1–18% of people have asthma.[21][22] Anaphylaxis occurs in between 0.05–2% of people.[23] Rates of many allergic diseases appear to be increasing.[7][24][25] The word "allergy" was first used by Clemens von Pirquet in 1906.[2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]| Affected organ | Common signs and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Nose | Swelling of the nasal mucosa (allergic rhinitis) runny nose, sneezing |

| Sinuses | Allergic sinusitis |

| Eyes | Redness and itching of the conjunctiva (allergic conjunctivitis, watery) |

| Airways | Sneezing, coughing, bronchoconstriction, wheezing and dyspnea, sometimes outright attacks of asthma, in severe cases the airway constricts due to swelling known as laryngeal edema |

| Ears | Feeling of fullness, possibly pain, and impaired hearing due to the lack of eustachian tube drainage. |

| Skin | Rashes, such as eczema and hives (urticaria) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting, diarrhea |

Many allergens such as dust or pollen are airborne particles. In these cases, symptoms arise in areas in contact with air, such as the eyes, nose, and lungs. For instance, allergic rhinitis, also known as hay fever, causes irritation of the nose, sneezing, itching, and redness of the eyes.[26] Inhaled allergens can also lead to increased production of mucus in the lungs, shortness of breath, coughing, and wheezing.[27]

Aside from these ambient allergens, allergic reactions can result from foods, insect stings, and reactions to medications like aspirin and antibiotics such as penicillin. Symptoms of food allergy include abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting, diarrhea, itchy skin, and hives. Food allergies rarely cause respiratory (asthmatic) reactions, or rhinitis.[28] Insect stings, food, antibiotics, and certain medicines may produce a systemic allergic response that is also called anaphylaxis; multiple organ systems can be affected, including the digestive system, the respiratory system, and the circulatory system.[29][30][31] Depending on the severity, anaphylaxis can include skin reactions, bronchoconstriction, swelling, low blood pressure, coma, and death. This type of reaction can be triggered suddenly, or the onset can be delayed. The nature of anaphylaxis is such that the reaction can seem to be subsiding but may recur throughout a period of time.[31]

Skin

[edit]Substances that come into contact with the skin, such as latex, are also common causes of allergic reactions, known as contact dermatitis or eczema.[32] Skin allergies frequently cause rashes, or swelling and inflammation within the skin, in what is known as a "wheal and flare" reaction characteristic of hives and angioedema.[33]

With insect stings, a large local reaction may occur in the form of an area of skin redness greater than 10 cm in size that can last one to two days.[34] This reaction may also occur after immunotherapy.[35]

The way the body responds to foreign invaders on the molecular level is similar to how allergens are treated even on the skin. The skin forms an effective barrier to the entry of most allergens but this barrier cannot withstand everything that comes at it. A situation such as an insect sting can breach the barrier and inject allergen to the affected spot. When an allergen enters the epidermis or dermis, it triggers a localized allergic reaction which activates the mast cells in the skin resulting in an immediate increase in vascular permeability, leading to fluid leakage and swelling in the affected area.[36] Mast-cell activation also stimulates a skin lesion called the wheal-and-flare reaction.[37] This is when the release of chemicals from local nerve endings by a nerve axon reflex, causes the vasodilatations of surrounding cutaneous blood vessels, which causes redness of the surrounding skin.[37]

As a part of the allergy response, the body has developed a secondary response which in some individuals causes a more widespread and sustained edematous response.[36] This usually occurs about 8 hours after the allergen originally comes in contact with the skin. When an allergen is ingested, a dispersed form of wheal-and-flare reaction, known as urticaria or hives will appear when the allergen enters the bloodstream and eventually reaches the skin.[36][38] The way the skin reacts to different allergens gives allergists the upper hand and allows them to test for allergies by injecting a very small amount of an allergen into the skin.[36] Even though these injections are very small and local, they still pose the risk of causing systematic anaphylaxis.[36]

Cause

[edit]Risk factors for allergies can be placed in two broad categories, namely host and environmental factors.[39] Host factors include heredity, sex, race, and age, with heredity being by far the most significant. However, there has been a recent increase in the incidence of allergic disorders that cannot be explained by genetic factors alone. Four major environmental candidates are alterations in exposure to infectious diseases during early childhood, environmental pollution, allergen levels, and dietary changes.[40]

Dust mites

[edit]Dust mite allergy, also known as house dust allergy, is a sensitization and allergic reaction to the droppings of house dust mites. The allergy is common[41][42] and can trigger allergic reactions such as asthma, eczema, or itching. The mite's gut contains potent digestive enzymes (notably peptidase 1) that persist in their feces and are major inducers of allergic reactions such as wheezing. The mite's exoskeleton can also contribute to allergic reactions. Unlike scabies mites or skin follicle mites, house dust mites do not burrow under the skin and are not parasitic.[43]

Foods

[edit]A wide variety of foods can cause allergic reactions, but 90% of allergic responses to foods are caused by cow's milk, soy, eggs, wheat, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish.[44] Other food allergies, affecting less than 1 person per 10,000 population, may be considered "rare".[45] The most common food allergy in the US population is a sensitivity to crustacea.[45] Although peanut allergies are notorious for their severity, peanut allergies are not the most common food allergy in adults or children. Severe or life-threatening reactions may be triggered by other allergens and are more common when combined with asthma.[44]

Rates of allergies differ between adults and children. Children can sometimes outgrow peanut allergies. Egg allergies affect one to two percent of children but are outgrown by about two-thirds of children by the age of 5.[46] The sensitivity is usually to proteins in the white, rather than the yolk.[47]

Milk-protein allergies—distinct from lactose intolerance—are most common in children.[48] Approximately 60% of milk-protein reactions are immunoglobulin E–mediated, with the remaining usually attributable to inflammation of the colon.[49] Some people are unable to tolerate milk from goats or sheep as well as from cows, and many are also unable to tolerate dairy products such as cheese. Roughly 10% of children with a milk allergy will have a reaction to beef.[50] Lactose intolerance, a common reaction to milk, is not a form of allergy at all, but due to the absence of an enzyme in the digestive tract.[51]

Those with tree nut allergies may be allergic to one or many tree nuts, including pecans, pistachios, and walnuts.[47] In addition, seeds, including sesame seeds and poppy seeds, contain oils in which protein is present, which may elicit an allergic reaction.[47]

Allergens can be transferred from one food to another through genetic engineering; however, genetic modification can also remove allergens. Little research has been done on the natural variation of allergen concentrations in unmodified crops.[52][53]

Latex

[edit]Latex can trigger an IgE-mediated cutaneous, respiratory, and systemic reaction. The prevalence of latex allergy in the general population is believed to be less than one percent. In a hospital study, 1 in 800 surgical patients (0.125 percent) reported latex sensitivity, although the sensitivity among healthcare workers is higher, between seven and ten percent. Researchers attribute this higher level to the exposure of healthcare workers to areas with significant airborne latex allergens, such as operating rooms, intensive-care units, and dental suites. These latex-rich environments may sensitize healthcare workers who regularly inhale allergenic proteins.[54]

The most prevalent response to latex is an allergic contact dermatitis, a delayed hypersensitive reaction appearing as dry, crusted lesions. This reaction usually lasts 48–96 hours. Sweating or rubbing the area under the glove aggravates the lesions, possibly leading to ulcerations.[54] Anaphylactic reactions occur most often in sensitive patients who have been exposed to a surgeon's latex gloves during abdominal surgery, but other mucosal exposures, such as dental procedures, can also produce systemic reactions.[54]

Latex and banana sensitivity may cross-react. Furthermore, those with latex allergy may also have sensitivities to avocado, kiwifruit, and chestnut.[55] These people often have perioral itching and local urticaria. Only occasionally have these food-induced allergies induced systemic responses. Researchers suspect that the cross-reactivity of latex with banana, avocado, kiwifruit, and chestnut occurs because latex proteins are structurally homologous with some other plant proteins.[54]

Medications

[edit]About 10% of people report that they are allergic to penicillin; however, of that 10%, 90% turn out not to be.[56] Serious allergies only occur in about 0.03%.[56]

Insect stings

[edit]One of the main sources of human allergies is insects. An allergy to insects can be brought on by bites, stings, ingestion, and inhalation.[57]

Toxins interacting with proteins

[edit]Another non-food protein reaction, urushiol-induced contact dermatitis, originates after contact with poison ivy, eastern poison oak, western poison oak, or poison sumac. Urushiol, which is not itself a protein, acts as a hapten and chemically reacts with, binds to, and changes the shape of integral membrane proteins on exposed skin cells. The immune system does not recognize the affected cells as normal parts of the body, causing a T-cell-mediated immune response.[58]

Of these poisonous plants, sumac is the most virulent.[59][60] The resulting dermatological response to the reaction between urushiol and membrane proteins includes redness, swelling, papules, vesicles, blisters, and streaking.[61]

Estimates vary on the population fraction that will have an immune system response. Approximately 25% of the population will have a strong allergic response to urushiol. In general, approximately 80–90% of adults will develop a rash if they are exposed to 0.0050 mg (7.7×10−5 gr) of purified urushiol, but some people are so sensitive that it takes only a molecular trace on the skin to initiate an allergic reaction.[62]

Genetics

[edit]Allergic diseases are strongly familial; identical twins are likely to have the same allergic diseases about 70% of the time; the same allergy occurs about 40% of the time in non-identical twins.[63] Allergic parents are more likely to have allergic children[64] and those children's allergies are likely to be more severe than those in children of non-allergic parents. Some allergies, however, are not consistent along genealogies; parents who are allergic to peanuts may have children who are allergic to ragweed. The likelihood of developing allergies is inherited and related to an irregularity in the immune system, but the specific allergen is not.[64]

The risk of allergic sensitization and the development of allergies varies with age, with young children most at risk.[65] Several studies have shown that IgE levels are highest in childhood and fall rapidly between the ages of 10 and 30 years.[65] The peak prevalence of hay fever is highest in children and young adults and the incidence of asthma is highest in children under 10.[66]

Ethnicity may play a role in some allergies; however, racial factors have been difficult to separate from environmental influences and changes due to migration.[64] It has been suggested that different genetic loci are responsible for asthma, to be specific, in people of European, Hispanic, Asian, and African origins.[67]

Researchers have worked to characterize genes involved in inflammation and the maintenance of mucosal integrity. The identified genes associated with allergic disease severity, progression, and development primarily function in four areas: regulating inflammatory responses (IFN-α, TLR-1, IL-13, IL-4, IL-5, HLA-G, iNOS), maintaining vascular endothelium and mucosal lining (FLG, PLAUR, CTNNA3, PDCH1, COL29A1), mediating immune cell function (PHF11, H1R, HDC, TSLP, STAT6, RERE, PPP2R3C), and influencing susceptibility to allergic sensitization (e.g., ORMDL3, CHI3L1).[68]

Multiple studies have investigated the genetic profiles of individuals with predispositions to and experiences of allergic diseases, revealing a complex polygenic architecture. Specific genetic loci, such as MIIP, CXCR4, SCML4, CYP1B1, ICOS, and LINC00824, have been directly associated with allergic disorders.[68] Additionally, some loci show pleiotropic effects, linking them to both autoimmune and allergic conditions, including PRDM2, G3BP1, HBS1L, and POU2AF1.[68] These genes engage in shared inflammatory pathways across various epithelial tissues—such as the skin, esophagus, vagina, and lung—highlighting common genetic factors that contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma and other allergic diseases.[68]

In atopic patients, transcriptome studies have identified IL-13-related pathways as key for eosinophilic airway inflammation and remodeling. That causes the body to experience the type of airflow restriction of allergic asthma.[68] Expression of genes was quite variable: genes associated with inflammation were found almost exclusively in superficial airways, while genes related to airway remodeling were mainly present in endobronchial biopsy specimens.[68] This enhanced gene profile was similar across multiple sample sizes – nasal brushing, sputum, endobronchial brushing – demonstrating the importance of eosinophilic inflammation, mast cell degranulation and group 3 innate lymphoid cells in severe adult-onset asthma.[68] IL-13 is an immunoregulatory cytokine that is made mostly by activated T-helper 2 (Th2) cells.[69] It is an important cytokine for many steps in B-cell maturation and differentiation, since it increases CD23 and MHC class II molecules, and aids in B-cell isotype switching to IgE.[68][69] IL-13 also suppresses macrophage function by reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.[69][70] The more striking thing is that IL-13 is the prime mover in allergen-induced asthma via pathways that are independent of IgE and eosinophils.[69]

Hygiene hypothesis

[edit]Allergic diseases are caused by inappropriate immunological responses to harmless antigens driven by a TH2-mediated immune response. Many bacteria and viruses elicit a TH1-mediated immune response, which down-regulates TH2 responses. The first proposed mechanism of action of the hygiene hypothesis was that insufficient stimulation of the TH1 arm of the immune system leads to an overactive TH2 arm, which in turn leads to allergic disease.[71] In other words, individuals living in too sterile an environment are not exposed to enough pathogens to keep the immune system busy. Since our bodies evolved to deal with a certain level of such pathogens, when they are not exposed to this level, the immune system will attack harmless antigens, and thus normally benign microbial objects—like pollen—will trigger an immune response.[72]

The hygiene hypothesis was developed to explain the observation that hay fever and eczema, both allergic diseases, were less common in children from larger families, which were, it is presumed, exposed to more infectious agents through their siblings, than in children from families with only one child.[73] It is used to explain the increase in allergic diseases that have been seen since industrialization, and the higher incidence of allergic diseases in more developed countries.[74] The hygiene hypothesis has now expanded to include exposure to symbiotic bacteria and parasites as important modulators of immune system development, along with infectious agents.[75]

Epidemiological data support the hygiene hypothesis. Studies have shown that various immunological and autoimmune diseases are much less common in the developing world than the industrialized world, and that immigrants to the industrialized world from the developing world increasingly develop immunological disorders in relation to the length of time since arrival in the industrialized world.[76] Longitudinal studies in the third world demonstrate an increase in immunological disorders as a country grows more affluent and, it is presumed, cleaner.[77] The use of antibiotics in the first year of life has been linked to asthma and other allergic diseases.[78] The use of antibacterial cleaning products has also been associated with higher incidence of asthma, as has birth by caesarean section rather than vaginal birth.[79][80]

Stress

[edit]Chronic stress can aggravate allergic conditions. This has been attributed to a T helper 2 (TH2)-predominant response driven by suppression of interleukin 12 by both the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Stress management in highly susceptible individuals may improve symptoms.[81]

Other environmental factors

[edit]Allergic diseases are more common in industrialized countries than in countries that are more traditional or agricultural, and there is a higher rate of allergic disease in urban populations versus rural populations, although these differences are becoming less defined.[82] Historically, the trees planted in urban areas were predominantly male to prevent litter from seeds and fruits, but the high ratio of male trees causes high pollen counts, a phenomenon that horticulturist Tom Ogren has called "botanical sexism".[83]

Alterations in exposure to microorganisms is another plausible explanation, at present, for the increase in atopic allergy.[40] Endotoxin exposure reduces release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFNγ, interleukin-10, and interleukin-12 from white blood cells (leukocytes) that circulate in the blood.[84] Certain microbe-sensing proteins, known as Toll-like receptors, found on the surface of cells in the body are also thought to be involved in these processes.[85]

Parasitic worms and similar parasites are present in untreated drinking water in developing countries, and were present in the water of developed countries until the routine chlorination and purification of drinking water supplies.[86] Recent research has shown that some common parasites, such as intestinal worms (e.g., hookworms), secrete chemicals into the gut wall (and, hence, the bloodstream) that suppress the immune system and prevent the body from attacking the parasite.[87] This gives rise to a new slant on the hygiene hypothesis theory—that co-evolution of humans and parasites has led to an immune system that functions correctly only in the presence of the parasites. Without them, the immune system becomes unbalanced and oversensitive.[88]

In particular, research suggests that allergies may coincide with the delayed establishment of gut flora in infants.[89] However, the research to support this theory is conflicting, with some studies performed in China and Ethiopia showing an increase in allergy in people infected with intestinal worms.[82] Clinical trials have been initiated to test the effectiveness of helminthic therapy with certain worms in treating some allergies.[90] It may be that the term 'parasite' could turn out to be inappropriate, and in fact a hitherto unsuspected symbiosis is at work.[90]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

Acute response

[edit]

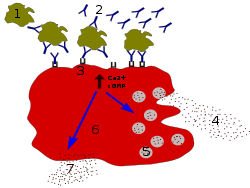

In the initial stages of allergy, a type I hypersensitivity reaction against an allergen encountered for the first time and presented by a professional antigen-presenting cell causes a response in a type of immune cell called a TH2 lymphocyte, a subset of T cells that produce a cytokine called interleukin-4 (IL-4). These TH2 cells interact with other lymphocytes called B cells, whose role is production of antibodies. Coupled with signals provided by IL-4, this interaction stimulates the B cell to begin production of a large amount of a particular type of antibody known as IgE. Secreted IgE circulates in the blood and binds to an IgE-specific receptor (a kind of Fc receptor called FcεRI) on the surface of other kinds of immune cells called mast cells and basophils, which are both involved in the acute inflammatory response. The IgE-coated cells, at this stage, are sensitized to the allergen.[40]

If later exposure to the same allergen occurs, the allergen can bind to the IgE molecules held on the surface of the mast cells or basophils. Cross-linking of the IgE and Fc receptors occurs when more than one IgE-receptor complex interacts with the same allergenic molecule and activates the sensitized cell. Activated mast cells and basophils undergo a process called degranulation, during which they release histamine and other inflammatory chemical mediators (cytokines, interleukins, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins) from their granules into the surrounding tissue causing several systemic effects, such as vasodilation, mucous secretion, nerve stimulation, and smooth muscle contraction.

This results in rhinorrhea, itchiness, dyspnea, and anaphylaxis. Depending on the individual, allergen, and mode of introduction, the symptoms can be system-wide (classical anaphylaxis) or localized to specific body systems. Asthma is localized to the respiratory system and eczema is localized to the dermis.[40]

Late-phase response

[edit]After the chemical mediators of the acute response subside, late-phase responses can often occur. This is due to the migration of other leukocytes such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and macrophages to the initial site. The reaction is usually seen 2–24 hours after the original reaction.[91] Cytokines from mast cells may play a role in the persistence of long-term effects. Late-phase responses seen in asthma are slightly different from those seen in other allergic responses, although they are still caused by release of mediators from eosinophils and are still dependent on activity of TH2 cells.[92]

Allergic contact dermatitis

[edit]Although allergic contact dermatitis is termed an "allergic" reaction (which usually refers to type I hypersensitivity), its pathophysiology involves a reaction that more correctly corresponds to a type IV hypersensitivity reaction.[93] In type IV hypersensitivity, there is activation of certain types of T cells (CD8+) that destroy target cells on contact, as well as activated macrophages that produce hydrolytic enzymes.[94]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Effective management of allergic diseases relies on the ability to make an accurate diagnosis.[95] Allergy testing can help confirm or rule out allergies.[96][97] Correct diagnosis, counseling, and avoidance advice based on valid allergy test results reduce the incidence of symptoms and need for medications, and improve quality of life.[96] To assess the presence of allergen-specific IgE antibodies, two different methods can be used: a skin prick test, or an allergy blood test. Both methods are recommended, and they have similar diagnostic value.[97][98]

Skin prick tests and blood tests are equally cost-effective, and health economic evidence shows that both tests were cost-effective compared with no test.[96] Early and more accurate diagnoses save cost due to reduced consultations, referrals to secondary care, misdiagnosis, and emergency admissions.[99]

Allergy undergoes dynamic changes over time. Regular allergy testing of relevant allergens provides information on if and how patient management can be changed to improve health and quality of life. Annual testing is often the practice for determining whether allergy to milk, egg, soy, and wheat have been outgrown, and the testing interval is extended to 2–3 years for allergy to peanut, tree nuts, fish, and crustacean shellfish.[97] Results of follow-up testing can guide decision-making regarding whether and when it is safe to introduce or re-introduce allergenic food into the diet.[100]

Skin prick testing

[edit]

Skin testing is also known as "puncture testing" and "prick testing" due to the series of tiny punctures or pricks made into the patient's skin. Tiny amounts of suspected allergens and/or their extracts (e.g., pollen, grass, mite proteins, peanut extract) are introduced to sites on the skin marked with pen or dye (the ink/dye should be carefully selected, lest it cause an allergic response itself). A negative and positive control are also included for comparison (eg, negative is saline or glycerin; positive is histamine). A small plastic or metal device is used to puncture or prick the skin. Sometimes, the allergens are injected "intradermally" into the patient's skin, with a needle and syringe. Common areas for testing include the inside forearm and the back.

If the patient is allergic to the substance, then a visible inflammatory reaction will usually occur within 30 minutes. This response will range from slight reddening of the skin to a full-blown hive (called "wheal and flare") in more sensitive patients similar to a mosquito bite. Interpretation of the results of the skin prick test is normally done by allergists on a scale of severity, with +/− meaning borderline reactivity, and 4+ being a large reaction. Increasingly, allergists are measuring and recording the diameter of the wheal and flare reaction. Interpretation by well-trained allergists is often guided by relevant literature.[101]

In general, a positive response is interpreted when the wheal of an antigen is ≥3mm larger than the wheal of the negative control (eg, saline or glycerin).[102] Some patients may believe they have determined their own allergic sensitivity from observation, but a skin test has been shown to be much better than patient observation to detect allergy.[103]

If a serious life-threatening anaphylactic reaction has brought a patient in for evaluation, some allergists will prefer an initial blood test prior to performing the skin prick test. Skin tests may not be an option if the patient has widespread skin disease or has taken antihistamines in the last several days.

Patch testing

[edit]

Patch testing is a method used to determine if a specific substance causes allergic inflammation of the skin. It tests for delayed reactions. It is used to help ascertain the cause of skin contact allergy or contact dermatitis. Adhesive patches, usually treated with several common allergic chemicals or skin sensitizers, are applied to the back. The skin is then examined for possible local reactions at least twice, usually at 48 hours after application of the patch, and again two or three days later.

Blood testing

[edit]An allergy blood test is quick and simple and can be ordered by a licensed health care provider (e.g., an allergy specialist) or general practitioner. Unlike skin-prick testing, a blood test can be performed irrespective of age, skin condition, medication, symptom, disease activity, and pregnancy. Adults and children of any age can get an allergy blood test. For babies and very young children, a single needle stick for allergy blood testing is often gentler than several skin pricks.

An allergy blood test is available through most laboratories. A sample of the patient's blood is sent to a laboratory for analysis, and the results are sent back a few days later. Multiple allergens can be detected with a single blood sample. Allergy blood tests are very safe since the person is not exposed to any allergens during the testing procedure. After the onset of anaphylaxis or a severe allergic reaction, guidelines recommend emergency departments obtain a time-sensitive blood test to determine blood tryptase levels and assess for mast cell activation.[104]

The test measures the concentration of specific IgE antibodies in the blood. Quantitative IgE test results increase the possibility of ranking how different substances may affect symptoms. A rule of thumb is that the higher the IgE antibody value, the greater the likelihood of symptoms. Allergens found at low levels that today do not result in symptoms cannot help predict future symptom development. The quantitative allergy blood result can help determine what a patient is allergic to, help predict and follow the disease development, estimate the risk of a severe reaction, and explain cross-reactivity.[105][106]

A low total IgE level is not adequate to rule out sensitization to commonly inhaled allergens.[107] Statistical methods, such as ROC curves, predictive value calculations, and likelihood ratios have been used to examine the relationship of various testing methods to each other. These methods have shown that patients with a high total IgE have a high probability of allergic sensitization, but further investigation with allergy tests for specific IgE antibodies for a carefully chosen of allergens is often warranted.

Laboratory methods to measure specific IgE antibodies for allergy testing include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, or EIA),[108] radioallergosorbent test (RAST),[108] fluorescent enzyme immunoassay (FEIA),[109] and chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA).[110][111]

Other testing

[edit]Challenge testing: Challenge testing is when tiny amounts of a suspected allergen are introduced to the body orally, through inhalation, or via other routes. Except for testing food and medication allergies, challenges are rarely performed. When this type of testing is chosen, it must be closely supervised by an allergist.

Elimination/challenge tests: This testing method is used most often with foods or medicines. A patient with a suspected allergen is instructed to modify his diet to totally avoid that allergen for a set time. If the patient experiences significant improvement, he may then be "challenged" by reintroducing the allergen, to see if symptoms are reproduced.

Unreliable tests: There are other types of allergy testing methods that are unreliable, including applied kinesiology (allergy testing through muscle relaxation), cytotoxicity testing, urine autoinjection, skin titration (Rinkel method), and provocative and neutralization (subcutaneous) testing or sublingual provocation.[112]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Before a diagnosis of allergic disease can be confirmed, other plausible causes of the presenting symptoms must be considered.[113] Vasomotor rhinitis, for example, is one of many illnesses that share symptoms with allergic rhinitis, underscoring the need for professional differential diagnosis.[114] Once a diagnosis of asthma, rhinitis, anaphylaxis, or other allergic disease has been made, there are several methods for discovering the causative agent of that allergy.

Prevention

[edit]Giving peanut products early in childhood may decrease the risk of allergies, and only breastfeeding during at least the first few months of life may decrease the risk of allergic dermatitis.[115][116] There is little evidence that a mother's diet during pregnancy or breastfeeding affects the risk of allergies,[115] although there has been some research to show that irregular cow's milk exposure might increase the risk of cow's milk allergy.[117] There is some evidence that delayed introduction of certain foods is useful,[115] and that early exposure to potential allergens may actually be protective.[5]

Fish oil supplementation during pregnancy is associated with a lower risk of food sensitivities.[116] Probiotic supplements during pregnancy or infancy may help to prevent atopic dermatitis.[118][119]

Management

[edit]Management of allergies typically involves avoiding the allergy trigger and taking medications to improve the symptoms.[6] Allergen immunotherapy may be useful for some types of allergies.[6]

Medication

[edit]Several medications may be used to block the action of allergic mediators, or to prevent activation of cells and degranulation processes. These include antihistamines, glucocorticoids, epinephrine (adrenaline), mast cell stabilizers, and antileukotriene agents are common treatments of allergic diseases.[120] Anticholinergics, decongestants, and other compounds thought to impair eosinophil chemotaxis are also commonly used. Although rare, the severity of anaphylaxis often requires epinephrine injection, and where medical care is unavailable, a device known as an epinephrine autoinjector may be used.[31]

Immunotherapy

[edit]

Allergen immunotherapy is useful for environmental allergies, allergies to insect bites, and asthma.[6][121] Its benefit for food allergies is unclear and thus not recommended.[6] Immunotherapy involves exposing people to larger and larger amounts of allergen in an effort to change the immune system's response.[6]

Meta-analyses have found that injections of allergens under the skin is effective in the treatment in allergic rhinitis in children[122][123] and in asthma.[121] The benefits may last for years after treatment is stopped.[124] It is generally safe and effective for allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis, allergic forms of asthma, and stinging insects.[125]

To a lesser extent, the evidence also supports the use of sublingual immunotherapy for rhinitis and asthma.[124] For seasonal allergies the benefit is small.[126] In this form the allergen is given under the tongue and people often prefer it to injections.[124] Immunotherapy is not recommended as a stand-alone treatment for asthma.[124]

Alternative medicine

[edit]An experimental treatment, enzyme potentiated desensitization (EPD), has been tried for decades but is not generally accepted as effective.[127] EPD uses dilutions of allergen and an enzyme, beta-glucuronidase, to which T-regulatory lymphocytes are supposed to respond by favoring desensitization, or down-regulation, rather than sensitization. EPD has also been tried for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, but evidence does not show effectiveness.[127]

A review found no effectiveness of homeopathic treatments and no difference compared with placebo. The authors concluded that based on rigorous clinical trials of all types of homeopathy for childhood and adolescence ailments, there is no convincing evidence that supports the use of homeopathic treatments.[128]

According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, U.S., the evidence is relatively strong that saline nasal irrigation and butterbur are effective, when compared to other alternative medicine treatments, for which the scientific evidence is weak, negative, or nonexistent, such as honey, acupuncture, omega 3's, probiotics, astragalus, capsaicin, grape seed extract, Pycnogenol, quercetin, spirulina, stinging nettle, tinospora, or guduchi. [129][130]

Epidemiology

[edit]The allergic diseases—hay fever and asthma—have increased in the Western world over the past 2–3 decades.[131] Increases in allergic asthma and other atopic disorders in industrialized nations, it is estimated, began in the 1960s and 1970s, with further increases occurring during the 1980s and 1990s,[132] although some suggest that a steady rise in sensitization has been occurring since the 1920s.[133] The number of new cases per year of atopy in developing countries has, in general, remained much lower.[132]

| Allergy type | United States | United Kingdom[134] |

|---|---|---|

| Allergic rhinitis | 35.9 million[135] (about 11% of the population[136]) | 3.3 million (about 5.5% of the population[137]) |

| Asthma | 10 million have allergic asthma (about 3% of the population). The prevalence of asthma increased 75% from 1980 to 1994. Asthma prevalence is 39% higher in African Americans than in Europeans.[138] | 5.7 million (about 9.4%). In six- and seven-year-olds asthma increased from 18.4% to 20.9% over five years, during the same time the rate decreased from 31% to 24.7% in 13- to 14-year-olds. |

| Atopic eczema | About 9% of the population. Between 1960 and 1990, prevalence has increased from 3% to 10% in children.[139] | 5.8 million (about 1% severe). |

| Anaphylaxis | At least 40 deaths per year due to insect venom. About 400 deaths due to penicillin anaphylaxis. About 220 cases of anaphylaxis and 3 deaths per year are due to latex allergy.[140] An estimated 150 people die annually from anaphylaxis due to food allergy.[141] | Between 1999 and 2006, 48 deaths occurred in people ranging from five months to 85 years old. |

| Insect venom | Around 15% of adults have mild, localized allergic reactions. Systemic reactions occur in 3% of adults and less than 1% of children.[142] | Unknown |

| Drug allergies | Anaphylactic reactions to penicillin cause 400 deaths per year. | Unknown |

| Food allergies | 7.6% of children and 10.8% of adults.[143] Peanut and/or tree nut (e.g. walnut) allergy affects about three million Americans, or 1.1% of the population.[141] | 5–7% of infants and 1–2% of adults. A 117.3% increase in peanut allergies was observed from 2001 to 2005, an estimated 25,700 people in England are affected. |

| Multiple allergies (Asthma, eczema and allergic rhinitis together) | Unknown | 2.3 million (about 3.7%), prevalence has increased by 48.9% between 2001 and 2005.[144] |

Changing frequency

[edit]Although genetic factors govern susceptibility to atopic disease, increases in atopy have occurred within too short a period to be explained by a genetic change in the population, thus pointing to environmental or lifestyle changes.[132] Several hypotheses have been identified to explain this increased rate. Increased exposure to perennial allergens may be due to housing changes and increased time spent indoors, and a decreased activation of a common immune control mechanism may be caused by changes in cleanliness[145] or hygiene, and exacerbated by dietary changes, obesity, and decline in physical exercise.[131] The hygiene hypothesis maintains[146] that high living standards and hygienic conditions exposes children to fewer infections. It is thought that reduced bacterial and viral infections early in life direct the maturing immune system away from TH1 type responses, leading to unrestrained TH2 responses that allow for an increase in allergy.[88][147]

Changes in rates and types of infection alone, however, have been unable to explain the observed increase in allergic disease, and recent evidence has focused attention on the importance of the gastrointestinal microbial environment. Evidence has shown that exposure to food and fecal-oral pathogens, such as hepatitis A, Toxoplasma gondii, and Helicobacter pylori (which also tend to be more prevalent in developing countries), can reduce the overall risk of atopy by more than 60%,[148] and an increased rate of parasitic infections has been associated with a decreased prevalence of asthma.[149] It is speculated that these infections exert their effect by critically altering TH1/TH2 regulation.[150] Important elements of newer hygiene hypotheses also include exposure to endotoxins, exposure to pets and growing up on a farm.[150]

History

[edit]Some symptoms attributable to allergic diseases are mentioned in ancient sources.[151] Particularly, three members of the Roman Julio-Claudian dynasty (Augustus, Claudius and Britannicus) are suspected to have a family history of atopy.[151][152] The concept of "allergy" was originally introduced in 1906 by the Viennese pediatrician Clemens von Pirquet, after he noticed that patients who had received injections of horse serum or smallpox vaccine usually had quicker, more severe reactions to second injections.[153] Pirquet called this phenomenon "allergy" from the Ancient Greek words ἄλλος allos meaning "other" and ἔργον ergon meaning "work".[154]

All forms of hypersensitivity used to be classified as allergies, and all were thought to be caused by an improper activation of the immune system. Later, it became clear that several different disease mechanisms were implicated, with a common link to a disordered activation of the immune system. In 1963, a new classification scheme was designed by Philip Gell and Robin Coombs that described four types of hypersensitivity reactions, known as Type I to Type IV hypersensitivity.[155]

With this new classification, the word allergy, sometimes clarified as a true allergy, was restricted to type I hypersensitivities (also called immediate hypersensitivity), which are characterized as rapidly developing reactions involving IgE antibodies.[156]

A major breakthrough in understanding the mechanisms of allergy was the discovery of the antibody class labeled immunoglobulin E (IgE). IgE was simultaneously discovered in 1966–67 by two independent groups:[157] Ishizaka's team at the Children's Asthma Research Institute and Hospital in Denver, USA,[158] and by Gunnar Johansson and Hans Bennich in Uppsala, Sweden.[159] Their joint paper was published in April 1969.[160]

Diagnosis

[edit]Radiometric assays include the radioallergosorbent test (RAST test) method, which uses IgE-binding (anti-IgE) antibodies labeled with radioactive isotopes for quantifying the levels of IgE antibody in the blood.[161]

The RAST methodology was invented and marketed in 1974 by Pharmacia Diagnostics AB, Uppsala, Sweden, and the acronym RAST is actually a brand name. In 1989, Pharmacia Diagnostics AB replaced it with a superior test named the ImmunoCAP Specific IgE blood test, which uses the newer fluorescence-labeled technology.[162]

American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) and the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) issued the Joint Task Force Report "Pearls and pitfalls of allergy diagnostic testing" in 2008, and is firm in its statement that the term RAST is now obsolete:

The term RAST became a colloquialism for all varieties of (in vitro allergy) tests. This is unfortunate because it is well recognized that there are well-performing tests and some that do not perform so well, yet they are all called RASTs, making it difficult to distinguish which is which. For these reasons, it is now recommended that use of RAST as a generic descriptor of these tests be abandoned.[17]

The updated version, the ImmunoCAP Specific IgE blood test, is the only specific IgE assay to receive Food and Drug Administration approval to quantitatively report to its detection limit of 0.1kU/L.[162]

Medical specialty

[edit]| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names |

|

Occupation type | Specialty |

Activity sectors | Medicine |

| Specialty | immunology |

| Description | |

Education required |

|

Fields of employment | Hospitals, Clinics |

The medical speciality that studies, diagnoses and treats diseases caused by allergies is called allergology.[163] An allergist is a physician specially trained to manage and treat allergies, asthma, and the other allergic diseases. In the United States physicians holding certification by the American Board of Allergy and Immunology (ABAI) have successfully completed an accredited educational program and evaluation process, including a proctored examination to demonstrate knowledge, skills, and experience in patient care in allergy and immunology.[164] Becoming an allergist/immunologist requires completion of at least nine years of training.

After completing medical school and graduating with a medical degree, a physician will undergo three years of training in internal medicine (to become an internist) or pediatrics (to become a pediatrician). Once physicians have finished training in one of these specialties, they must pass the exam of either the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), the American Osteopathic Board of Pediatrics (AOBP), the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), or the American Osteopathic Board of Internal Medicine (AOBIM). Internists or pediatricians wishing to focus on the sub-specialty of allergy-immunology then complete at least an additional two years of study, called a fellowship, in an allergy/immunology training program. Allergist/immunologists listed as ABAI-certified have successfully passed the certifying examination of the ABAI following their fellowship.[165]

In the United Kingdom, allergy is a subspecialty of general medicine or pediatrics. After obtaining postgraduate exams (MRCP or MRCPCH), a doctor works for several years as a specialist registrar before qualifying for the General Medical Council specialist register. Allergy services may also be delivered by immunologists. A 2003 Royal College of Physicians report presented a case for improvement of what were felt to be inadequate allergy services in the UK.[166]

In 2006, the House of Lords convened a subcommittee. It concluded likewise in 2007 that allergy services were insufficient to deal with what the Lords referred to as an "allergy epidemic" and its social cost; it made several recommendations.[167]

Research

[edit]Low-allergen foods are being developed, as are improvements in skin prick test predictions; evaluation of the atopy patch test, wasp sting outcomes predictions, a rapidly disintegrating epinephrine tablet, and anti-IL-5 for eosinophilic diseases.[168]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Types of Allergic Diseases". NIAID. 29 May 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d Kay AB (2000). "Overview of 'allergy and allergic diseases: with a view to the future'". British Medical Bulletin. 56 (4): 843–64. doi:10.1258/0007142001903481. PMID 11359624.

- ^ a b c d National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (July 2012). "Food Allergy An Overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b Bahna SL (December 2002). "Cow's milk allergy versus cow milk intolerance". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 89 (6 Suppl 1): 56–60. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62124-2. PMID 12487206.

- ^ a b c Sicherer SH, Sampson HA (February 2014). "Food allergy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 133 (2): 291–307, quiz 308. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.020. PMID 24388012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Allergen Immunotherapy". 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Simons FE (October 2009). "Anaphylaxis: Recent advances in assessment and treatment" (PDF). The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 124 (4): 625–36, quiz 637–38. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.025. PMID 19815109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2013.

- ^ Finn DF, Walsh JJ (September 2013). "Twenty-first century mast cell stabilizers". British Journal of Pharmacology. 170 (1): 23–37. doi:10.1111/bph.12138. PMC 3764846. PMID 23441583.

- ^ May JR, Dolen WK (December 2017). "Management of Allergic Rhinitis: A Review for the Community Pharmacist". Clinical Therapeutics. 39 (12): 2410–2419. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.10.006. PMID 29079387.

- ^ a b "Allergic Diseases". NIAID. 21 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b McConnell TH (2007). The Nature of Disease: Pathology for the Health Professions. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7817-5317-3.

- ^ "Allergy Defined | AAAAI". www.aaaai.org. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ "Allergy | British Society for Immunology". www.immunology.org. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ Resch, Klaus; Martin, Michael U. (2008), "Allergy", Encyclopedia of Molecular Pharmacology, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 58–64, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-38918-7_231, ISBN 978-3-540-38918-7, retrieved 4 July 2025

- ^ "Environmental Allergies: Symptoms". NIAID. 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ "How Does an Allergic Response Work?". NIAID. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b Cox L, Williams B, Sicherer S, Oppenheimer J, Sher L, Hamilton R, Golden D (December 2008). "Pearls and pitfalls of allergy diagnostic testing: report from the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Specific IgE Test Task Force". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 101 (6): 580–92. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60220-7. PMID 19119701.

- ^ Wheatley LM, Togias A (January 2015). "Clinical practice. Allergic rhinitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (5): 456–63. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1412282. PMC 4324099. PMID 25629743.

- ^ Bartha, Irene; Almulhem, Noorah; Santos, Alexandra F. (1 March 2024). "Feast for thought: A comprehensive review of food allergy 2021-2023". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 153 (3): 576–594. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2023.11.918. ISSN 0091-6749. PMC 11096837. PMID 38101757.

- ^ Thomsen SF (2014). "Atopic dermatitis: natural history, diagnosis, and treatment". ISRN Allergy. 2014 354250. doi:10.1155/2014/354250. PMC 4004110. PMID 25006501.

- ^ "Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention: Updated 2015" (PDF). Global Initiative for Asthma. 2015. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention" (PDF). Global Initiative for Asthma. 2011. pp. 2–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2012.

- ^ Grammer, Leslie C. (2012). Patterson's Allergic Diseases (7 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-4863-3.

- ^ Anandan C, Nurmatov U, van Schayck OC, Sheikh A (February 2010). "Is the prevalence of asthma declining? Systematic review of epidemiological studies". Allergy. 65 (2): 152–67. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02244.x. PMID 19912154. S2CID 19525219.

- ^ Pongdee T. "Increasing Rates of Allergies and Asthma". American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

- ^ Bope, Edward T.; Rakel, Robert E. (2005). Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. p. 880. ISBN 978-0-7216-3864-5.

- ^ Holgate ST (March 1998). "Asthma and allergy--disorders of civilization?". QJM. 91 (3): 171–84. doi:10.1093/qjmed/91.3.171. PMID 9604069.

- ^ Rusznak C, Davies RJ (February 1998). "ABC of allergies. Diagnosing allergy". BMJ. 316 (7132): 686–89. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7132.686. PMC 1112683. PMID 9522798.

- ^ Golden DB (May 2007). "Insect sting anaphylaxis". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 27 (2): 261–72, vii. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2007.03.008. PMC 1961691. PMID 17493502.

- ^ Schafer JA, Mateo N, Parlier GL, Rotschafer JC (April 2007). "Penicillin allergy skin testing: what do we do now?". Pharmacotherapy. 27 (4): 542–5. doi:10.1592/phco.27.4.542. PMID 17381381. S2CID 42870541.

- ^ a b c Tang AW (October 2003). "A practical guide to anaphylaxis". American Family Physician. 68 (7): 1325–32. PMID 14567487.

- ^ Brehler R, Kütting B (April 2001). "Natural rubber latex allergy: a problem of interdisciplinary concern in medicine". Archives of Internal Medicine. 161 (8): 1057–64. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.8.1057. PMID 11322839.

- ^ Muller BA (March 2004). "Urticaria and angioedema: a practical approach". American Family Physician. 69 (5): 1123–28. PMID 15023012.

- ^ Ludman SW, Boyle RJ (2015). "Stinging insect allergy: current perspectives on venom immunotherapy". Journal of Asthma and Allergy. 8: 75–86. doi:10.2147/JAA.S62288. PMC 4517515. PMID 26229493.

- ^ Slavin RG, Reisman RE, eds. (1999). Expert guide to allergy and immunology. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-943126-73-9.

- ^ a b c d e Janeway, CA; Travers, P; Walport, M (2001). "Effector mechanisms in allergic reactions". The Immune System in Health and Disease (5th ed.). New York: Garland Science.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b Robinson, Dan. "Wheal and Flare". ENT Clinics.

- ^ Oakley, Amanda (26 October 2023). "Urticaria (hives): A complete overview". DermNet®.

- ^ Grammatikos AP (2008). "The genetic and environmental basis of atopic diseases". Annals of Medicine. 40 (7): 482–95. doi:10.1080/07853890802082096. PMID 18608118. S2CID 188280.

- ^ a b c d Janeway C, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M (2001). Immunobiology (Fifth ed.). New York and London: Garland Science. pp. e–book. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009.

- ^ Alderman L (4 March 2011). "Who Should Worry About Dust Mites (and Who Shouldn't)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ "Dust Mite Allergy" (PDF). NHS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Ogg B. "Managing House Dust Mites" (PDF). Extension, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America". Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ a b Maleki SJ, Burks AW, Helm RM (2006). Food Allergy. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-1-55581-375-8.

- ^ Järvinen KM, Beyer K, Vila L, Bardina L, Mishoe M, Sampson HA (July 2007). "Specificity of IgE antibodies to sequential epitopes of hen's egg ovomucoid as a marker for persistence of egg allergy". Allergy. 62 (7): 758–65. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01332.x. PMID 17573723. S2CID 23540584.

- ^ a b c Sicherer 63

- ^ Maleki, Burks & Helm 2006, pp. 41

- ^ "World Allergy Organization". Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ Sicherer 64

- ^ Cleveland Clinic medical professional (3 March 2023). "Lactose Intolerance". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Herman EM (May 2003). "Genetically modified soybeans and food allergies". Journal of Experimental Botany. 54 (386): 1317–19. doi:10.1093/jxb/erg164. PMID 12709477.

- ^ Panda R, Ariyarathna H, Amnuaycheewa P, Tetteh A, Pramod SN, Taylor SL, Ballmer-Weber BK, Goodman RE (February 2013). "Challenges in testing genetically modified crops for potential increases in endogenous allergen expression for safety". Allergy. 68 (2): 142–51. doi:10.1111/all.12076. PMID 23205714. S2CID 13814194.

- ^ a b c d Sussman GL, Beezhold DH (January 1995). "Allergy to latex rubber". Annals of Internal Medicine. 122 (1): 43–46. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-122-1-199501010-00007. PMID 7985895. S2CID 22549639.

- ^ Fernández de Corres L, Moneo I, Muñoz D, Bernaola G, Fernández E, Audicana M, Urrutia I (January 1993). "Sensitization from chestnuts and bananas in patients with urticaria and anaphylaxis from contact with latex". Annals of Allergy. 70 (1): 35–39. PMID 7678724.

- ^ a b Gonzalez-Estrada A, Radojicic C (May 2015). "Penicillin allergy: A practical guide for clinicians". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 82 (5): 295–300. doi:10.3949/ccjm.82a.14111. PMID 25973877. S2CID 6717270.

- ^ Fukutomi, Yuma; Kawakami, Yuji (2021). "Respiratory sensitization to insect allergens: Species, components and clinical symptoms". Allergology International. 70 (3). Elsevier BV: 303–312. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2021.04.001. ISSN 1323-8930. PMID 33903033.

- ^ Hogan CM (2008). Stromberg N (ed.). "Western poison-oak: Toxicodendron diversilobum". GlobalTwitcher. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Keeler HL (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 94–96.

- ^ Frankel E (1991). Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, Poison Sumac and Their Relatives; Pistachios, Mangoes and Cashews. Pacific Grove, CA: The Boxwood Press. ISBN 978-0-940168-18-3.

- ^ DermAtlas -1892628434

- ^ Armstrong W.P.; Epstein W.L. (1995). "Poison oak: more than just scratching the surface". Herbalgram. 34: 36–42. cited in "Poison Oak". Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Galli SJ (February 2000). "Allergy". Current Biology. 10 (3): R93–5. Bibcode:2000CBio...10..R93G. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00322-5. PMID 10679332. S2CID 215506771.

- ^ a b c De Swert LF (February 1999). "Risk factors for allergy". European Journal of Pediatrics. 158 (2): 89–94. doi:10.1007/s004310051024. PMID 10048601. S2CID 10311795.

- ^ a b Croner S (November 1992). "Prediction and detection of allergy development: influence of genetic and environmental factors". The Journal of Pediatrics. 121 (5 Pt 2): S58–63. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81408-8. PMID 1447635.

- ^ Jarvis D, Burney P (1997). "Epidemiology of atopy and atopic disease". In Kay AB (ed.). Allergy and allergic diseases. Vol. 2. London: Blackwell Science. pp. 1208–24.

- ^ Barnes KC, Grant AV, Hansel NN, Gao P, Dunston GM (January 2007). "African Americans with asthma: genetic insights". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 4 (1): 58–68. doi:10.1513/pats.200607-146JG. PMC 2647616. PMID 17202293.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Falcon, Robbi Miguel G.; Caoili, Salvador Eugenio C. (2023). "Immunologic, genetic, and ecological interplay of factors involved in allergic diseases". Frontiers in Allergy. 4 1215616. Frontiers. doi:10.3389/falgy.2023.1215616. PMC 10435091. PMID 37601647.

- ^ a b c d "IL13 interleukin 13 [homo sapiens (human)] - gene". National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Zhu, Chunhua; Zhang, Aihua; Songming, Huang; Ding, Guixia; Pan, Xiaoqin; Chen, Ronghua (2010). "Interleukin-13 inhibits cytokines synthesis by blocking nuclear factor-ΚB and c-jun N-terminal kinase in human mesangial cells". Journal of Biomedical Research. 24 (4). U.S. National Library of Medicine: 308–316. doi:10.1016/S1674-8301(10)60043-7. PMC 3596597. PMID 23554645.

- ^ Folkerts G, Walzl G, Openshaw PJ (March 2000). "Do common childhood infections 'teach' the immune system not to be allergic?". Immunology Today. 21 (3): 118–20. doi:10.1016/S0167-5699(00)01582-6. PMID 10777250.

- ^ "The Hygiene Hypothesis". Edward Willett. 30 January 2013. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ Perkin, Michael R; Strachan, David P (24 November 2022). "The hygiene hypothesis for allergy – conception and evolution". Frontiers in Allergy. 3 1051368. Frontiers Media SA. doi:10.3389/falgy.2022.1051368. ISSN 2673-6101. PMC 9731379. PMID 36506644.

- ^ Bonis, Peter A. L. (2009). "Putting the Puzzle Together: Epidemiological and Clinical Clues in the Etiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 29 (1). Elsevier BV: 41–52. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2008.09.005. ISSN 0889-8561. PMID 19141340.

- ^ Stiemsma, Leah; Reynolds, Lisa; Turvey, Stuart; Finlay, Brett (2015). "The hygiene hypothesis: current perspectives and future therapies". ImmunoTargets and Therapy. 4. Informa UK Limited: 143–157. doi:10.2147/itt.s61528. ISSN 2253-1556. PMC 4918254. PMID 27471720.

- ^ Gibson PG, Henry RL, Shah S, Powell H, Wang H (September 2003). "Migration to a western country increases asthma symptoms but not eosinophilic airway inflammation". Pediatric Pulmonology. 36 (3): 209–15. doi:10.1002/ppul.10323. hdl:1959.4/11209. PMID 12910582. S2CID 29589706.. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ^ Addo-Yobo EO, Woodcock A, Allotey A, Baffoe-Bonnie B, Strachan D, Custovic A (February 2007). "Exercise-induced bronchospasm and atopy in Ghana: two surveys ten years apart". PLOS Medicine. 4 (2) e70. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040070. PMC 1808098. PMID 17326711.

- ^ Marra F, Lynd L, Coombes M, Richardson K, Legal M, Fitzgerald JM, Marra CA (March 2006). "Does antibiotic exposure during infancy lead to development of asthma?: a systematic review and metaanalysis". Chest. 129 (3): 610–18. doi:10.1378/chest.129.3.610. PMID 16537858.

- ^ Thavagnanam S, Fleming J, Bromley A, Shields MD, Cardwell CR (April 2008). "A meta-analysis of the association between Caesarean section and childhood asthma". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 38 (4): 629–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02780.x. PMID 18352976. S2CID 23077809.

- ^ Zock JP, Plana E, Jarvis D, Antó JM, Kromhout H, Kennedy SM, Künzli N, Villani S, Olivieri M, Torén K, Radon K, Sunyer J, Dahlman-Hoglund A, Norbäck D, Kogevinas M (October 2007). "The use of household cleaning sprays and adult asthma: an international longitudinal study". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 176 (8): 735–41. doi:10.1164/rccm.200612-1793OC. PMC 2020829. PMID 17585104.

- ^ Dave ND, Xiang L, Rehm KE, Marshall GD (February 2011). "Stress and allergic diseases". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 31 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.009. PMC 3264048. PMID 21094923.

- ^ a b Cooper PJ (2004). "Intestinal worms and human allergy". Parasite Immunology. 26 (11–12): 455–67. doi:10.1111/j.0141-9838.2004.00728.x. PMID 15771681. S2CID 23348293.

- ^ Ogren TL (29 April 2015). "Botanical Sexism Cultivates Home-Grown Allergies". Scientific American. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Braun-Fahrländer C, Riedler J, Herz U, Eder W, Waser M, Grize L, Maisch S, Carr D, Gerlach F, Bufe A, Lauener RP, Schierl R, Renz H, Nowak D, von Mutius E (September 2002). "Environmental exposure to endotoxin and its relation to asthma in school-age children". The New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (12): 869–77. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020057. PMID 12239255.

- ^ Garn H, Renz H (2007). "Epidemiological and immunological evidence for the hygiene hypothesis". Immunobiology. 212 (6): 441–52. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2007.03.006. PMID 17544829.

- ^ Macpherson CN, Gottstein B, Geerts S (April 2000). "Parasitic food-borne and water-borne zoonoses". Revue Scientifique et Technique. 19 (1): 240–58. doi:10.20506/rst.19.1.1218. PMID 11189719.

- ^ Carvalho EM, Bastos LS, Araújo MI (October 2006). "Worms and allergy". Parasite Immunology. 28 (10): 525–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00894.x. PMID 16965288. S2CID 12360685.

- ^ a b Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG, van Ree R (April 2002). "Allergy, parasites, and the hygiene hypothesis". Science. 296 (5567): 490–94. Bibcode:2002Sci...296..490Y. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.570.9502. doi:10.1126/science.296.5567.490. PMID 11964470.

- ^ Emanuelsson C, Spangfort MD (May 2007). "Allergens as eukaryotic proteins lacking bacterial homologues". Molecular Immunology. 44 (12): 3256–60. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.01.019. PMID 17382394.

- ^ a b Falcone FH, Pritchard DI (April 2005). "Parasite role reversal: worms on trial". Trends in Parasitology. 21 (4): 157–60. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2005.02.002. PMID 15780835.

- ^ Grimbaldeston MA, Metz M, Yu M, Tsai M, Galli SJ (December 2006). "Effector and potential immunoregulatory roles of mast cells in IgE-associated acquired immune responses". Current Opinion in Immunology. 18 (6): 751–60. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.011. PMID 17011762.

- ^ Holt PG, Sly PD (October 2007). "Th2 cytokines in the asthma late-phase response". Lancet. 370 (9596): 1396–98. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61587-6. PMID 17950849. S2CID 40819814.

- ^ Martín A, Gallino N, Gagliardi J, Ortiz S, Lascano AR, Diller A, Daraio MC, Kahn A, Mariani AL, Serra HM (August 2002). "Early inflammatory markers in elicitation of allergic contact dermatitis". BMC Dermatology. 2 9. doi:10.1186/1471-5945-2-9. PMC 122084. PMID 12167174.

- ^ Hou, Wanzhu; Xu, Guangpi; Wang, Hanjie (2011). "Basic immunology and immune system disorders". Treating Autoimmune Disease with Chinese Medicine. Elsevier. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-06974-1.00001-4. ISBN 978-0-443-06974-1.

- ^ Portnoy JM; et al. (2006). "Evidence-based Allergy Diagnostic Tests". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 6 (6): 455–61. doi:10.1007/s11882-006-0021-8. PMID 17026871. S2CID 33406344.

- ^ a b c NICE Diagnosis and assessment of food allergy in children and young people in primary care and community settings, 2011

- ^ a b c Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, et al. (December 2010). "Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 126 (6 Suppl): S1–58. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007. PMC 4241964. PMID 21134576.

- ^ Cox L (2011). "Overview of Serological-Specific IgE Antibody Testing in Children". Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 11 (6): 447–53. doi:10.1007/s11882-011-0226-3. PMID 21947715. S2CID 207323701.

- ^ "CG116 Food allergy in children and young people: costing report". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 23 February 2011. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ^ "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Summary of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel Report" (PDF). NIH. 2010. 11-7700. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Verstege A, Mehl A, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Staden U, Nocon M, Beyer K, Niggemann B, et al. (September 2005). "The predictive value of the skin prick test weal size for the outcome of oral food challenges". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 35 (9): 1220–26. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.2324.x. PMID 16164451. S2CID 38060324.

- ^ "Appropriate use of allergy testing in primary care - Best Tests December 2011". bpac.org.nz. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Li JT, Andrist D, Bamlet WR, Wolter TD (November 2000). "Accuracy of patient prediction of allergy skin test results". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 85 (5): 382–84. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62550-1. PMID 11101180.

- ^ Reinhold, Lauren (February 2023). "An Update on Test use Evaluation of Serum Tryptase Levels". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 151 (2): AB10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.12.038.

- ^ Yunginger JW, Ahlstedt S, Eggleston PA, Homburger HA, Nelson HS, Ownby DR, et al. (June 2000). "Quantitative IgE antibody assays in allergic diseases". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 105 (6): 1077–84. doi:10.1067/mai.2000.107041. PMID 10856139.

- ^ Sampson HA (May 2001). "Utility of food-specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergy". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 107 (5): 891–96. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.114708. PMID 11344358.

- ^ Kerkhof M, Dubois AE, Postma DS, Schouten JP, de Monchy JG (September 2003). "Role and interpretation of total serum IgE measurements in the diagnosis of allergic airway disease in adults". Allergy. 58 (9): 905–11. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00230.x. PMID 12911420. S2CID 34461177.

- ^ a b "Blood Testing for Allergies". WebMD. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ Khan FM, Ueno-Yamanouchi A, Serushago B, Bowen T, Lyon AW, Lu C, Storek J (January 2012). "Basophil activation test compared to skin prick test and fluorescence enzyme immunoassay for aeroallergen-specific Immunoglobulin-E". Allergy, Asthma, and Clinical Immunology. 8 (1) 1. doi:10.1186/1710-1492-8-1. PMC 3398323. PMID 22264407.

- ^ Casas ML, Esteban Á, González-Muñoz M, Labrador-Horrillo M, Pascal M, & Teniente-Serra A (2020). VALIDA project: Validation of allergy in vitro diagnostics assays (Tools and recommendations for the assessment of in vitro tests in the diagnosis of allergy). In Advances in Laboratory Medicine (Vol. 1, Issue 4). Walter de Gruyter GmbH. https://doi.org/10.1515/almed-2020-0051

- ^ Bulat Lokas S, Plavec D, Rikić Pišković J, Živković J, Nogalo B, & Turkalj M (2017). Allergen-Specific IgE Measurement: Intermethod Comparison of Two Assay Systems in Diagnosing Clinical Allergy. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis, 31(3), e22047. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.22047

- ^ "Allergy Diagnosis". Archived from the original on 11 August 2010.The Online Allergist. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ Allergic and Environmental Asthma at eMedicine – Includes discussion of differentials

- ^ Wheeler PW, Wheeler SF (September 2005). "Vasomotor rhinitis". American Family Physician. 72 (6): 1057–62. PMID 16190503. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW (April 2019). "The Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Hydrolyzed Formulas, and Timing of Introduction of Allergenic Complementary Foods". Pediatrics. 143 (4) e20190281. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-0281. PMID 30886111.

- ^ a b Garcia-Larsen V, Ierodiakonou D, Jarrold K, Cunha S, Chivinge J, Robinson Z, Geoghegan N, Ruparelia A, Devani P, Trivella M, Leonardi-Bee J, Boyle RJ (February 2018). "Diet during pregnancy and infancy and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 15 (2) e1002507. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002507. PMC 5830033. PMID 29489823.

- ^ Abrams, Elissa (May 2023). "Prevention of food allergy in infancy: the role of maternal interventions and exposures during pregnancy and lactation". The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 7 (5): 358–366. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00349-2. PMID 36871575.

- ^ Pelucchi C, Chatenoud L, Turati F, Galeone C, Moja L, Bach JF, La Vecchia C (May 2012). "Probiotics supplementation during pregnancy or infancy for the prevention of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis". Epidemiology. 23 (3): 402–14. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824d5da2. PMID 22441545. S2CID 40634979.

- ^ Osborn DA, Sinn JK (March 2013). Osborn D (ed.). "Prebiotics in infants for prevention of allergy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3) CD006474. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006474. PMID 23543544.

- ^ Frieri M (June 2018). "Mast Cell Activation Syndrome". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 54 (3): 353–65. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8487-6. PMID 25944644. S2CID 5723622.

- ^ a b Abramson MJ, Puy RM, Weiner JM (August 2010). "Injection allergen immunotherapy for asthma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8) CD001186. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001186.pub2. PMID 20687065.

- ^ Penagos M, Compalati E, Tarantini F, Baena-Cagnani R, Huerta J, Passalacqua G, Canonica GW (August 2006). "Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy in the treatment of allergic rhinitis in pediatric patients 3 to 18 years of age: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 97 (2): 141–48. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60004-X. PMID 16937742.

- ^ Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A, Durham S (January 2007). "Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (1) CD001936. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001936.pub2. PMC 7017974. PMID 17253469.

- ^ a b c d Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Casale T, Lockey RF, Baena-Cagnani CE, Pawankar R, et al. (December 2009). "Sub-lingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization Position Paper 2009" (PDF). Allergy. 64 (Suppl 91): 1–59. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02309.x. PMID 20041860. S2CID 10420738. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2011.

- ^ Rank MA, Li JT (September 2007). "Allergen immunotherapy". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 82 (9): 1119–23. doi:10.4065/82.9.1119. PMID 17803880.

- ^ Di Bona D, Plaia A, Leto-Barone MS, La Piana S, Di Lorenzo G (August 2015). "Efficacy of Grass Pollen Allergen Sublingual Immunotherapy Tablets for Seasonal Allergic Rhinoconjunctivitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 175 (8): 1301–09. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2840. hdl:11586/181026. PMID 26120825.

- ^ a b Terr AI (2004). "Unproven and controversial forms of immunotherapy". Clinical Allergy and Immunology. 18: 703–10. PMID 15042943.

- ^ Altunç U, Pittler MH, Ernst E (January 2007). "Homeopathy for childhood and adolescence ailments: systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 82 (1): 69–75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.456.5352. doi:10.4065/82.1.69. PMID 17285788.

- ^ "12 Natural Ways to Defeat Allergies". Archived from the original on 2 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ "Seasonal Allergies and Complementary Health Approaches: What the Science Says". 11 April 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ a b Platts-Mills TA, Erwin E, Heymann P, Woodfolk J (2005). "Is the hygiene hypothesis still a viable explanation for the increased prevalence of asthma?". Allergy. 60 (nSuppl 79): 25–31. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00854.x. PMID 15842230. S2CID 36479898.

- ^ a b c Bloomfield SF, Stanwell-Smith R, Crevel RW, Pickup J (April 2006). "Too clean, or not too clean: the hygiene hypothesis and home hygiene". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 36 (4): 402–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02463.x. PMC 1448690. PMID 16630145.

- ^ Isolauri E, Huurre A, Salminen S, Impivaara O (July 2004). "The allergy epidemic extends beyond the past few decades". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 34 (7): 1007–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01999.x. PMID 15248842. S2CID 33703088.

- ^ "Chapter 4: The Extent and Burden of Allergy in the United Kingdom". House of Lords – Science and Technology – Sixth Report. 24 July 2007. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ "AAAAI – rhinitis, sinusitis, hay fever, stuffy nose, watery eyes, sinus infection". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ Based on an estimated population of 303 million in 2007 "U.S. POPClock Projection". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012.

- ^ Based on an estimated population of 60.6 million "UK population grows to 60.6 million". National Statistics. UK Web Archive. Archived from the original on 2 December 2002.

- ^ "AAAAI – asthma, allergy, allergies, prevention of allergies and asthma, treatment for allergies and asthma". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ "AAAAI – skin condition, itchy skin, bumps, red irritated skin, allergic reaction, treating skin condition". Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ "AAAAI – anaphylaxis, cause of anaphylaxis, prevention, allergist, anaphylaxis statistics". Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ a b "AAAAI – food allergy, food reactions, anaphylaxis, food allergy prevention". Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ "AAAAI – stinging insect, allergic reaction to bug bite, treatment for insect bite". Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ "Allergy Facts | AAFA.org". www.aafa.org. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Simpson CR, Newton J, Hippisley-Cox J, Sheikh A (November 2008). "Incidence and prevalence of multiple allergic disorders recorded in a national primary care database". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 101 (11): 558–63. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2008.080196. PMC 2586863. PMID 19029357.

- ^ Dablo, Rose (20 December 2022). "Reduce Allergens By Cleanliness". CooperClean.

- ^ Strachan DP (November 1989). "Hay fever, hygiene, and household size". BMJ. 299 (6710): 1259–60. doi:10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. PMC 1838109. PMID 2513902.

- ^ Renz H, Blümer N, Virna S, Sel S, Garn H (2006). "The immunological basis of the hygiene hypothesis". Allergy and Asthma in Modern Society: A Scientific Approach. Chemical Immunology and Allergy. Vol. 91. pp. 30–48. doi:10.1159/000090228. ISBN 978-3-8055-8000-7. PMID 16354947.