Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

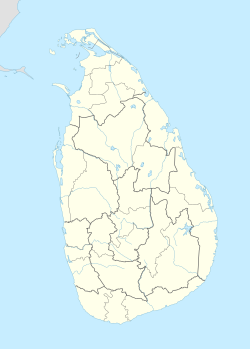

Colombo

View on Wikipedia

Colombo (/kəˈlʌmboʊ/ kə-LUM-boh;[2] Sinhala: කොළඹ, romanised: Koḷam̆ba, IPA: [ˈkoləᵐbə]; Tamil: கொழும்பு, romanised: Koḻumpu, IPA: [koɻumbɯ]) is the executive and judicial capital[3] and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million,[4][5][6][7] and 752,993[1] within the municipal limits. It is the financial centre of the island and a tourist destination.[8] It is located on the west coast of the island and adjacent to the Greater Colombo area which includes Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte, the legislative capital of Sri Lanka, and Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia. Colombo is often referred to as the capital since Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte is situated within the Colombo metro area. It is also the administrative capital of the Western Province and the district capital of Colombo District. Colombo is a busy and vibrant city with a mixture of modern life, colonial buildings and monuments.[9]

Key Information

It was made the capital of the island when Sri Lanka was ceded to the British Empire in 1815,[10] retaining its capital status when Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948. In 1978, when administrative functions were moved to Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte, Colombo was designated as the commercial capital of Sri Lanka.

Etymology

[edit]

The name 'Colombo', first introduced by the Portuguese explorers in 1505, is believed to be derived from the classical Sinhala name කොලොන් තොට, கொல்லம் துறைமுகம் Kolon thota, meaning "port on the river Kelani".[11]

Another belief is that the name is derived from the Sinhala name කොල-අඹ-තොට, பெருங்குடல் துறைமுகம் Kola-amba-thota which means 'Harbour with leafy/green mango trees'.[12] This coincides with Robert Knox's history of the island while he was a prisoner in Kandy. He writes that "On the West, the City of Columbo, so-called from a Tree the Natives call Ambo, (which bears the Mango-fruit) growing in that place; but this never bear fruit, but only leaves, which in their Language is kola and thence they called the Tree Colambo: which the Christians in honour of Christopher Columbus turned to Columbo."

The author of the oldest Sinhala grammar, Sidatsangarava, written in the 13th century wrote about a category of words that exclusively belonged to early Sinhala. It lists naramba (to see) and kolamba (fort or harbour) as deriving from the indigenous Vedda language. Kolamba may also be the source of the name of the commercial capital Colombo.[13][14]

History

[edit]Traveller Ibn Battuta who visited the island in the 14th century, referred to it as Kalanpu.[15] Arabs, whose primary interests were trade, began to settle in Colombo around the eighth century AD mostly because the port helped their business by the way of controlling much of the trade between the Sinhalese kingdoms and the outside world. It was popularly believed that their descendants comprised the local Sri Lankan Moor community, but their genetics are predominantly South Indian.[10][16]

Portuguese era

[edit]Portuguese explorers led by Dom Lourenço de Almeida first arrived in Sri Lanka in 1505. During their initial visit they made a treaty with the King of Kotte, Parakramabahu VIII (1484–1518), which enabled them to trade in the island's crop of cinnamon, which lay along with the coastal areas of the island, including in Colombo.[17] As part of the treaty, the Portuguese were given full authority over the coastline in exchange for the promise of guarding the coast against invaders. They were allowed to establish a trading post in Colombo.[17] Within a short time, however, they expelled the Muslim inhabitants of Colombo and began to build a fort in 1517.

The Portuguese soon realised that control of Sri Lanka was necessary for the protection of their coastal establishments in India, and they began to manipulate the rulers of the Kotte kingdom to gain control of the area. After skilfully exploiting rivalries within the royal family, they took control of a large area of the kingdom and the Sinhalese King Mayadunne established a new kingdom at Sitawaka, a domain in the Kotte kingdom.[17] Before long he annexed much of the Kotte kingdom and forced the Portuguese to retreat to Colombo, which was repeatedly besieged by Mayadunne and the later kings of Sitawaka, forcing them to seek reinforcement from their major base in Goa, India. Following the fall of the kingdom in 1593, the Portuguese were able to establish complete control over the coastal area, with Colombo as their capital.[17][18] This part of Colombo is still known as Fort and houses the presidential palace and the majority of Colombo's five star hotels. The area immediately outside Fort is known as Pettah (Sinhala: පිට කොටුව,Tamil: புறக் கோட்டை piṭa koṭuva, "outer fort") and is a commercial hub.

Dutch era

[edit]

In 1638 the Dutch signed a treaty with King Rajasinha II of Kandy which assured the king assistance in his war against the Portuguese in exchange for a monopoly of the island's major trade goods. The Portuguese resisted the Dutch and the Kandyans but were gradually defeated in their strongholds beginning in 1639.[19] The Dutch captured Colombo in 1656 after an epic siege, at the end of which a mere 93 Portuguese survivors were given safe conduct out of the fort. Although the Dutch (e.g., Rijcklof van Goens) initially restored the captured area back to the Sinhalese kings, they later refused to turn them over and gained control over the island's richest cinnamon lands including Colombo which then served as the capital of the Dutch maritime provinces under the control of the Dutch East India Company until 1796.[19][20]

British era

[edit]

Although the British captured Colombo in 1796, it remained a British military outpost until the Kandyan Kingdom was ceded to them in 1815 and they made Colombo the capital of their newly created crown colony of British Ceylon. Unlike the Portuguese and Dutch before them, whose primary use of Colombo was as a military fort, the British began constructing houses and other civilian structures around the fort, giving rise to the current City of Colombo.[10]

Initially, they placed the administration of the city under a "Collector", and John Macdowell of the Madras Service was the first to hold the office. Then, in 1833, the Government Agent of the Western Province was charged with the administration of the city. Centuries of colonial rule had meant a decline of indigenous administration of Colombo and in 1865 the British conceived a Municipal Council as a means of training the local population in self-governance. The Legislative Council of Ceylon constituted the Colombo Municipal Council in 1865 and the Council met for the first time on 16 January 1866. At the time, the population of the region was around 80,000.[10]

During the time they were in control of Colombo, the British were responsible for much of the planning of the present city. In some parts of the city, tram car tracks and granite flooring laid during the era are still visible today.[20][21]

After independence

[edit]

This era of colonialism ended peacefully in 1948 when Ceylon gained independence from Britain.[22] Due to the tremendous impact this caused on the city's inhabitants and on the country as a whole, the changes that resulted at the end of the colonial period were drastic. An entire new culture took root. Changes in laws and customs, clothing styles, religions and proper names were a significant result of the colonial era.[22] These cultural changes were followed by the strengthening of the island's economy. Even today, the influence of the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British is visible in Colombo's architecture, names, clothing, food, language and attitudes. Buildings from all three eras stand as reminders of the turbulent past of Colombo. The city and its people show an interesting mix of European clothing and lifestyles together with local customs.[22]

Historically, Colombo referred to the area around the Fort and Pettah Market which is known for the variety of products available as well as the Khan Clock Tower, a local landmark. At present, it refers to the city limits of the Colombo Municipal Council.[23] More often, the name is used for the Conurbation known as Greater Colombo, which encompasses several Municipal councils including Kotte, Dehiwela and Colombo.

Although Colombo lost its status as the capital of Sri Lanka in the 1980s to Sri Jayawardanapura, it continues to be the island's commercial centre. Despite the official capital of Sri Lanka moving to the adjacent Sri Jayawardanapura Kotte, most countries still maintain their diplomatic missions in Colombo.[24]

Geography

[edit]

The geography of Colombo consists of both land and water. The city has many canals and, in the heart of the city, the 65-hectare (160-acre) Beira Lake.[25] The lake is one of the most distinctive landmarks of Colombo and was used for centuries by colonists to defend the city.[25] It remains a tourist attraction, hosting regattas,[26] and theatrical events on its shores. The northern and north-eastern border of the city of Colombo is formed by the Kelani River, which meets the sea in a part of the city known as the Modera (mōdara in Sinhala) which means river delta.

Climate

[edit]Colombo features a tropical rainforest climate (Af). Colombo's climate is hot throughout the year. From March to April the average high temperature is around 31 °C (87.8 °F).[27] The only major change in the Colombo weather occurs during the monsoon seasons from April to June and September to November, when heavy rains occur. Colombo sees little relative diurnal range of temperature, although this is more marked in the drier winter months, where minimum temperatures average 22 °C (71.6 °F). Rainfall in the city averages around 2,500 millimetres (98 in) a year.[28]

| Climate data for Colombo, Sri Lanka (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1961–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.2 (95.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.2 (95.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

35.2 (95.4) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

33.6 (92.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.4 (97.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.4 (88.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.2 (81.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.1 (73.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24.8 (76.6) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.5 (74.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 79.6 (3.13) |

77.4 (3.05) |

102.7 (4.04) |

248.9 (9.80) |

313.6 (12.35) |

196.7 (7.74) |

122.6 (4.83) |

115.5 (4.55) |

264.2 (10.40) |

359.3 (14.15) |

345.8 (13.61) |

170.7 (6.72) |

2,397 (94.37) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.9 | 5.1 | 7.7 | 12.6 | 16.6 | 15.2 | 10.0 | 10.2 | 15.2 | 18.6 | 16.0 | 9.0 | 141.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at Daytime) | 69 | 69 | 71 | 75 | 78 | 79 | 78 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 76 | 73 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248.0 | 246.4 | 275.9 | 234.0 | 201.5 | 195.0 | 201.5 | 201.5 | 189.0 | 201.5 | 210.0 | 217.0 | 2,621.3 |

| Source 1: NOAA (humidity, sun 1961–1990)[29][30] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes)[31] | |||||||||||||

Attractions

[edit]

Galle Face Green is located in the heart of the city along the Indian Ocean coast and is a destination for tourists and residents alike. The Galle Face Hotel is a historic landmark on the southern edge of this promenade.

Gangaramaya Temple is one of the most important temples in Colombo. The temple's architecture demonstrates an eclectic mix of Sri Lankan, Thai, Indian and Chinese architecture.[32]

The Viharamahadevi Park (formerly Victoria Park) is an urban park located next to the National Museum of Colombo and the Town Hall. It is the oldest and largest park in Colombo and features a large Buddha statue.

As part of the Urban Regeneration Program of the Government of Sri Lanka, many old sites and buildings were revamped into modern public recreational spaces and shopping precincts. These include Independence Memorial Hall Square, Pettah Floating Market and Old Dutch Hospital, among others.

Demographics

[edit]- Sinhalese 36.9 (35.9%)

- Sri Lankan Tamils 29.6 (28.8%)

- Sri Lankan Moors 29 (28.2%)

- Indian Tamils 2.2 (2.14%)

- Others 5 (4.87%)

Colombo is a multi-religious, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural city. The population of Colombo is a mix of numerous ethnic groups, mainly Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Moor and Sri Lankan Tamils, . There are also small communities of people with Chinese, Portuguese Burgher, Dutch Burgher, Malay and Indian origins living in the city, as well as numerous European expatriates. Colombo is the most populous city in Sri Lanka, with 642,163 people living within the city limits.[34] In 1866 the city had a population of around 80,000.[35]

- Buddhism (31.4%)

- Islam (31.2%)

- Hinduism (22.6%)

- Christianity (14.5%)

- Other (0.10%)

Government and politics

[edit]

Local government

[edit]Colombo is a charter city, with a mayor-council government.[37] The mayor and council members are elected through local government elections held once in five years. For the past 50 years the city had been ruled by the United National Party (UNP), a right leaning party, whose business-friendly policies resonate with the population of Colombo. However, the UNP nomination list for the 2006 Municipal elections was rejected,[38] and an Independent Group supported by the UNP won the elections.[39] Uvais Mohamed Imitiyas was subsequently appointed Mayor of Colombo.[40]

The city government provides sewer, road and waste management services to the residents. In the case of water, electricity and telephone utility services, the council liaises with the National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWSDB), the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) and telephone service providers operating in the country respectively.

National capital status

[edit]Colombo was the capital of the coastal areas controlled by the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British from the 1700s to 1815 when the British gained control of the entire island following the Kandyan convention. From then until the 1980s the national capital of the island was Colombo.

During the 1980s plans were made to move the administrative capital to Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte and thus move all governmental institutions out of Colombo to make way for commercial activities. As a primary step, the Parliament was moved to a new complex in Kotte, with several ministries and departments also relocated. However, the move was never completed.

Today, many governmental institutions still remain in Colombo. These include the President's House, Presidential Secretariat, Prime Minister's House (Temple Trees), Prime Minister's Office, the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, important government ministries and departments; such as Finance (Treasury), Defence, Public Administration & Home affairs, Foreign affairs, Justice and the Military headquarters, Naval headquarters (SLNS Parakrama), Air Force headquarters (SLAF Colombo) and Police national and field force headquarters.[41][42]

Suburbs and postal codes

[edit]City limits

[edit]

Colombo is divided into 15 numbered areas for the purposes of postal services. Within these areas are the suburbs with their corresponding post office.

| Postal number | City suburb |

| Colombo 1 | Fort |

| Colombo 2 | Slave Island,[43] Union Place |

| Colombo 3 | Kollupitiya |

| Colombo 4 | Bambalapitiya |

| Colombo 5 | Havelock Town, Kirulapone, Kirulapone North, Narahenpita |

| Colombo 6 | Wellawatte, Kirulapone South |

| Colombo 7 | Cinnamon Gardens |

| Colombo 8 | Borella |

| Colombo 9 | Dematagoda |

| Colombo 10 | Maradana, Panchikawatte |

| Colombo 11 | Pettah |

| Colombo 12 | Hulftsdorp |

| Colombo 13 | Kotahena, Bloemendhal |

| Colombo 14 | Grandpass |

| Colombo 15 | Modara/Mutwal, Mattakkuliya, Madampitiya |

Economy

[edit]

The great majority of Sri Lankan corporations have their head offices in Colombo including Aitken Spence, Ceylinco Corporation, Stassen group of companies, John Keells Holdings, Cargills, Hemas Holdings, SenzMate and Akbar Brothers. Some of the industries include chemicals, textiles, glass, cement, leather goods, furniture and jewellery. In the city centre is the World Trade Centre. The 40-story Twin Tower complex is the centre of important commercial establishments, in the Fort district, the city's nerve centre. Right outside the Fort area is Pettah which is derived from the Sinhala word pita which means 'out' or 'outside'.[44]

The Colombo Metropolitan area has a GDP (PPP) of $122 billion or 40% of the GDP, making it the most important aspect of the Sri Lankan economy. [citation needed]The per capita income of the Colombo Metro area stood at US$8623 and purchasing power per capita of $25,117, making it one of the most prosperous regions in South Asia.[45] The Colombo Metropolitan (CM) area is the most important industrial, commercial and administrative centre in Sri Lanka. A major share of the country's export-oriented manufacturing takes place in the CM area, which is the engine of growth for Sri Lanka.

The Western province contributes less than 40% to the GDP and about 80% of industrial value additions although it accounts for only 5.7% of the country's geographic area and 25% of the national population. Given its importance as the primary international gateway for Sri Lanka and as the main economic driver of the country, the government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) has launched an ambitious program to transform Colombo and its area into a metropolis of international standards. Bottlenecks are preventing the Colombo metropolitan area from realizing its full economic potential. To facilitate the transformation of Colombo, the government has to address these bottlenecks which have for long been obstructing economic and physical urban regeneration.[46]

Pettah is more crowded than the Fort area. Pettah's roads are always packed and pavements are full of small stalls selling items from delicious sharbat to shirts. Main Street consists mostly of clothes shops and the crossroads, which are known as Cross-Streets where each of the five streets specialises in a specific business. For example, First Cross Street is mostly electronic goods shops, the Second cellular phones and fancy goods. Most of these businesses are dominated by Muslim traders. At the end of Main Street further away from Fort is Sea Street – Sri Lanka's gold market – dominated by Tamil interests. This mile-long street is full of jewellery shops,[44] including the former head office of SriLankan Airlines.[47]

Law enforcement and crime

[edit]

The Sri Lanka Police, the main law enforcement agency of the island, liaise with the municipal council but is under the control of the Ministry of Defence of the central government.[48] Policing in Colombo and its suburbs falls within the Metropolitan Range headed by the Deputy Inspector General of Police (Metropolitan), this also includes the Colombo Crime Division.[49] As with most Sri Lankan cities, the magistrate court handles felony crimes while the district court handles civil cases.

As in other large cities around the world, Colombo experiences certain levels of street crime and bribery. Indeed, the corruption extends to the very top, US reports show. In addition, in the period from the 1980s to 2009, there have been a number of major terrorist attacks.[50][51] The LTTE has been linked to most of the bombings and assassinations in the city.[52] Welikada Prison is situated in Colombo and it is one of the largest maximum-security prisons in the country.[53]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Colombo has most of the amenities that a modern city has. Compared to other parts of the country, Colombo has the highest degree of infrastructure. Electricity, water and transport to street lights and phone booths are to a considerably good standard. Apart from that, many luxurious hotels, clubs and restaurants are in the city. In recent times there has been an outpour of high-rise condominiums, mainly due to the very high land prices.[54]

Harbour

[edit]

Colombo Harbour is the largest and one of the busiest ports in Sri Lanka. Colombo was established primarily as a port city during the colonial era, with an artificial harbour that has been expanded over the years. The Sri Lanka Navy maintains a naval base, SLNS Rangalla, within the harbour.

The Port of Colombo handled 3.75 million twenty-foot equivalent units in 2008, 10.6% up on 2007 (which itself was 9.7% up on 2006), bucking the global economic trend. Of those, 817,000 were local shipments with the rest transshipments. With a capacity of 5.7 million TEUs and a dredged depth of over 15 m (49 ft), the Colombo Harbour is one of the busiest ports in the world and ranks among the top 25 ports (23rd). Sri Lanka's Port of Colombo is said to be the busiest, largest port in the Indian Ocean.[55]

Colombo is part of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road that runs from the Chinese coast to the Upper Adriatic region with its rail connections to Central and Eastern Europe.[56][57][58][59][60]

Transport

[edit]Bus

[edit]Colombo has an extensive public transport system based on buses operated both by private operators and the government-owned Sri Lanka Transport Board (SLTB). The three primary bus terminals – Bastian Mawatha, Central and the Gunasinghapura Bus Terminals – are in Pettah.[61] Bastian Mawatha handles long-distance services whereas Gunasinghapura and Central handle local services.

Rail

[edit]

Train transport in the city is limited since most trains are meant for transport to and from the city rather than within it and are often overcrowded. However, the Central Bus Stand and Fort Railway Station function as the island's primary hub for bus and rail transport respectively. Up until the 1970s, the city had tram services, which were discontinued. Other means of transport include auto rickshaws (commonly called "three-wheelers") and taxicabs. Three-wheelers are entirely operated by individuals and hardly regulated whilst cab services are run by private companies and are metered.

- Main Line – Colombo Fort to Veyangoda; onwards to Kandy, Badulla, Matale, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Jaffna, Kankesanturai. Trincomalee, Batticaloa, Talaimannar (presently just Madhu Road).

- Coastal Line – Colombo to Panadura; onwards to Galle, Matara and Beliaththa.

- Puttalam Line – Colombo to Ja-Ela; onwards to Negombo and Puttalam.

- Kelani Valley Line – Colombo to Avissawella.

Roads

[edit]Post-war development in the Colombo area also involves the construction of numerous expressway grade arterial road routes. The first of these constructed is the Southern Expressway, which goes from Kottawa, a southern suburb of Colombo, to Matara City in the south of the country. Expressways constructed in the Colombo metropolitan area include the Colombo–Katunayake Expressway, which was opened in October 2013 and the Colombo orbital bypass Outer Circular Highway (Arthur C. Clarke Expressway). The Colombo-Katunayake Expressway (E03) runs from Peliyagoda, a northern suburb of Colombo, to Colombo International Airport and it is linked with one of the major commercial hubs and a major tourist destination of the country, the city of Negombo.[62][63]

- A1 highway connects Colombo with Kandy.

- A2 highway connects Colombo with Galle and Matara

- A3 highway connects Colombo with Negombo and Puttalam

- A4 highway connects Colombo with Ratnapura and Batticaloa

Ferry

[edit]An international ferry liner, the Scotia Prince, is conducting a ferry service to Tuticorin, India. Ferry services between the two countries have been revived after more than 20 years.[64]

Air

[edit]Ratmalana Airport is the city's airport, located 15 km (9.3 mi) south of the city centre. It commenced operating in 1935 and was the country's first international airport until it was replaced by Bandaranaike Airport in 1967. Ratmalana Airport now primarily services domestic flights, aviation training and international corporate flights.

Landmarks

[edit]

The two World Trade Centre towers used to be the most recognised landmarks of the city. Before they were completed in 1997, the adjacent Bank of Ceylon tower was the tallest structure and the most prominent city landmark. Before the skyscrapers were built, the Old Parliament Building that stood in the Fort district with the Old Colombo Lighthouse close to it used to be the tallest building. Another important landmark is the Independence Hall at Independence Square in Cinnamon Gardens.

Another landmark is St.Paul's Church Milagiriya, one of the oldest churches in Sri Lanka, first built by the Portuguese and rebuilt by the British in 1848. The Cargills & Millers building in Fort is also a protected building of historical significance.

Cannons that were once mounted on the rampart of the old fort of Colombo were laid out for observance and prestige at the Green. The colonial styled Galle Face Hotel, known as Asia's Emerald on the Green since 1864, is adjacent to Galle Face Green. The hotel has played host to guests such as the British royal family and other royal guests and celebrities. After a stay at the hotel, Princess Alexandra of Denmark commented that "the peacefulness and generosity encountered at the Galle Face Hotel cannot be matched."[65] Also facing Galle Face Green is the Ceylon Inter-Continental Hotel.

Education

[edit]

Education institutions in Colombo have a long history. Colombo has many of the prominent public schools in the country, some of them government-owned and others private. Most of the prominent schools in the city date back to the 1800s when they were established during the British colonial rule,[66] such as the Royal College Colombo established in 1835. Certain urban schools of Sri Lanka have some religious alignment; this is partly due to the influence of the British, who established Christian missionary schools.[67][68] These include the Anglican, Bishop's College(1875); the Methodist, Wesley College Colombo (1874); the Buddhist, Ananda College (1886); the Muslim, Zahira College (1892); the Catholic, St. Benedict's College, Colombo (1865),St. Joseph's College (1896). The religious alignments do not affect the curriculum of the school except for the demographics of the student population.[67] The secular schools Mahanama College (1954)D. S. Senanayake College (1967) and Sirimavo Bandaranaike Vidyalaya (1973) have been established in the post independence era. Colombo has many International Schools that have come up in recent years.

Higher education in the city has a long history, beginning with the establishment of the Colombo Medical School (1870), the Colombo Law College (1875), the School of Agriculture (1884) and the Government Technical College (1893). The first step in the creation of a university in Colombo was taken in 1913 with the establishment of the University College Colombo which prepared students for the external examinations of the University of London. This was followed by the establishment of the University of Ceylon in Colombo.[69] Today the University of Colombo and the University of the Visual & Performing Arts are state universities in the city. The Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology has a metropolitan campus in the city centre. There are several private higher education institutions in the city.

Architecture

[edit]

Colombo has widely varying architecture that spans centuries and depicts many styles. Colonial buildings influenced by the Portuguese, Dutch and British exist alongside structures built in Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, Indian and Contemporary architectural styles. No other place is this more evident than in the Fort area. Here, one may find new, towering skyscrapers as well as historic buildings dating far back as the 1700s.[70][71]

Colombo Fort

[edit]The Portuguese were the first colonists to settle in Colombo. Establishing a small trading post, they had laid the foundations for a small fort which in time became the largest colonial fort on the island. The Dutch expanded the fort, thus creating a well fortified harbour. This came into the possession of the British in the late 1700s, and by the late 19th century, seeing no threat to the Colombo Harbour, began demolishing the ramparts to make way for the development of the city. Although now there is nothing left of the fortifications, the area which was once the fort is still referred to as Fort. The area outside is Pettah, Sri Lanka or පිටකොටුව Pitakotuwa in Sinhala which means outer fort.[70][71]

Dutch-era buildings

[edit]There are none of the buildings of the Portuguese era and only a few from the Dutch period. These include the oldest building in the fort area, the former Dutch Hospital, the Dutch House which is now the Colombo Dutch Museum and several churches. The President's House (formerly the Queen's House) was originally the Dutch governor's house and successive British governors made it their office and residence. However, it has undergone much change since the Dutch period. Adjoining the President's House are the Gordon Gardens, now off-limits to the public.[70][71][72]

British-era buildings

[edit]Much of the old buildings of the fort area and in other parts of the city date back to British times; these include governmental, commercial buildings, and private houses. Some of the notable government building of British colonial architecture includes the old Parliament building, which is now the Presidential Secretariat; the Republic Building, which houses the Ministry of Foreign affairs but once housed the Ceylon Legislative council; the General Treasury Building; the old General Post Office, an Edwardian-style building opposite the President's House; the Prime Minister's Office; the Central Telegraph Office; and the Mathematics department of the University of Colombo (formally the Royal College, Colombo).[69] Notable commercial buildings of the British era include the Galle Face Hotel, Cargills and Millers' complex, and the Grand Oriental Hotel.[70][71]

-

The historical Cargills & Millers building continues as the headquarters of Cargills

-

The Old Parliament Building near the Galle Face Green, now the Presidential Secretariat

Culture

[edit]Annual cultural events and fairs

[edit]

Colombo's most popular festival is the celebration of Buddha's birth, enlightenment and death all falling on the same day.[73] In Sinhala this is known as Vesak.[73] During this festival, much of the city is decorated with lanterns, lights and special displays of light (known as thoran). The festival falls in mid-May and lasts a week. Many Sri Lankans visit the city to see the lantern competitions and decorations. During this week people distribute, rice, drinks and other food items for free in dunsal which means charity place. These dunsal are popular amongst visitors from the suburbs.

Since there is a large number of Muslims in Colombo. Eid Ul Fitr and Eid Ul Adha are two Islamic festivals that are celebrated in Colombo. Many businesses flourish during the eventual countdown for Eid Ul Fitr which is a major Islamic festival celebrated by Muslims after a month-long fasting. Colombo is generally very busy on the eve of the festivals as people do their last-minute shopping.

Christmas is another major festival. Although Sri Lanka's Christians make up only just over 7% of the population, Christmas is one of the island's biggest festivals. Most streets and commercial buildings light up from the beginning of December and festive sales begin at all shopping centres and department stores. Caroling and nativity plays are frequent sights during the season.

The Sinhalese and Hindu Aluth Awurudda' is a cultural event that takes place on 13 and 14 April. This is the celebration of the Sinhalese and Hindu new year. The festivities include many events and traditions that display a great deal of Sri Lankan culture. Several old clubs of the city give a glimpse of the British equestrian lifestyle; these include the Colombo Club, Orient Club, the 80 Club, and the Colombo Cricket Club.

Performing arts

[edit]

Colombo has several performing arts centres, which are popular for their musical and theatrical performances, including the Lionel Wendt Theatre, the Elphinstone, and Tower Hall, all of which were made for western-style productions. The Navarangahala found in the city is the country's first national theatre designed and built for Asian and local style musical and theatrical productions.

The Nelum Pokuna Mahinda Rajapaksa Theatre is a world-class theatre that opened in December 2011.[74] Designed in the form of the Lotus Pond in Polonnaruwa,[75][better source needed] the theatre is a major theatre destination.

Museums and art collections

[edit]The National Museum of Colombo, established on 1 January 1877 during the tenure of the British Colonial Governor Sir William Henry Gregory, is in the Cinnamon Gardens area.[76] The museum houses the crown jewels and throne of the last king of the kingdom of Kandy, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha.[77]

There is also the Colombo Dutch Museum detailing the Dutch colonial history of the country. Colombo does not boast a very big art gallery. There is a small collection of random Sri Lankan paintings at the Art Gallery in Green Path; next to it is the Natural History Museum.

Sports

[edit]

One of the most popular sports in Sri Lanka is cricket. The country emerged as champions of the 1996 Cricket World Cup and became runners up in 2007 and 2011. In the ICC World Twenty20 they became runners up in 2009 and 2012 and winners in 2014. The sport is played in parks, playgrounds, beaches and even in the streets. Colombo is the home for two of the country's most popular international cricket stadiums, Singhalese Sports Club's Cricket Stadium and R. Premadasa Stadium (named after late president Premadasa). Colombo Stars represents the city in Lanka Premier League.

Colombo has the distinction of being the only city in the world to have four cricket test venues in the past: Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu Stadium, Singhalese Sports Club Cricket Ground, Colombo Cricket Club Ground and Ranasinghe Premadasa Stadium. The Sugathadasa Stadium is an international standard stadium for athletics, swimming and football, also held the South Asian Games in 1991 and 2006. Situated in Colombo the Royal Colombo Golf Club is one of the oldest in Asia. Other sporting clubs in Colombo include Colombo Swimming Club, Colombo Rowing Club and the Yachting Association of Sri Lanka.

Rugby is also a popular sport at the club and school levels. Colombo has its local football team Colombo FC and the sport is being developed as a part of the FIFA Goal program.

The Colombo Port City is to include a new Formula One track, constructed in the vicinity of the Colombo Harbour. According to Dr Priyath Wickrama, the Chairman of the Sri Lanka Ports Authority, an eight-lane F1 track will "definitely" be a part of the New Port City. This would host the Sri Lankan Grand Prix.

Colombo Marathon is an internationally recognised marathon established in 1998.

Media

[edit]Almost all major media businesses in Sri Lanka operate from Colombo. The state media has its offices in Bullers Road and carries out regional transmissions from there. These include the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC), formerly known as Radio Ceylon, and the Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation. The SLBC is the oldest radio station in South Asia and the second oldest in the world. Many private broadcasting companies have their offices and transmission stations in or around Colombo. As with most metro areas, radio bands are highly utilised for radio communications. Some of the prominent radio stations broadcasting in the Colombo area are Sirasa FM, FM Derana, Hiru FM, Shakthi FM, Vettri FM, Sooriyan FM, Kiss FM, Lite FM, Yes FM, Gold FM, Sith FM, Y FM, E FM and many more.

Television networks operating in the Colombo metro area include the state-owned television broadcasting networks which are broadcast by the Rupavahini Corporation of Sri Lanka, broadcasting television in the official languages Sinhala and Tamil. English language television is also broadcast, more targeted to the demographics of the English speaking Sri Lankans, expatriate communities and tourists. There are as well several private operators. Many of the privately run television station networks were often based upon operational expansions of pre-existing commercial radio networks and broadcast infrastructure.

Twin towns and sister cities

[edit]| Country | City | State / Region | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nepal | Biratnagar | Morang District | 1874 |

| Russia | Saint Petersburg | N/A | 1997 |

| China | Shanghai | N/A | 2003 |

| Mongolia | Ulaanbaatar | – | 2012 |

| Maldives | Malé | Kaafu Atoll | 2013 |

| Maldives | Maroshi | Shaviyani Atoll | 2015 |

Notable people

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Colombo's colonial heritage is visible throughout the city, as in the historical Wolvendaal Church, established by the Dutch in 1749

-

The Nelum Pokuna Theatre at night

-

The Town Hall of Colombo at night, it is the headquarters of the Colombo Municipal Council and the office of the Mayor of Colombo

-

Beira Lake and southern side of the Gangaramaya Temple

-

The Jami Ul-Alfar Mosque is one of the oldest Mosques in Colombo

-

Cathedral of Christ the Living Saviour is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Colombo

-

The statue of Sir Charles Henry de Soysa at De Soysa-Liptons Circus, is the first of a native, in Colombo.[78]

-

The Viharamahadevi Park, (formerly Victoria Park) is the oldest and largest park in Colombo

-

Built in 1857, the Old Colombo Lighthouse also known as the Colombo Fort Clock Tower is the oldest clock-tower

-

The BMICH Conference Hall

-

Ceylon bank headquarters and world trade center.

-

Galle Face Green

-

Arcade Independence Square shopping mall

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "A6 : Population by ethnicity and district according to Divisional Secretary's Division, 2012". Census of Population & Housing, 2011. Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Colombo". Collins English Dictionary (13th ed.). HarperCollins. 2018. ISBN 978-0-008-28437-4.

- ^ "Colombo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Kumarage A, Amal (1 November 2007). "Impacts of Transportation Infrastructure and Services on Urban Poverty and Land Development in Colombo, Sri Lanka" (PDF). Global Urban Development Volume 3 Issue 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "The 10 Traits of Globally Fluent Metro Areas" (PDF). 2013. Brookings Institution. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Colombo: The Heartbeat of Sri Lanka/ Metro Colombo Urban Development Project". The World Bank. 21 March 2013. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Turning Sri Lanka's Urban Vision into Policy and Action" (PDF). UN Habitat. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Colombo, The Famous Business Hub of Sri Lanka – Stories & Advice". Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Jayewarden. "How Colombo Derived its Name". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d "History of Colombo". Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ "Colombo – then and now". Padma Edirisinghe. The Sunday Observer. 14 February 2004. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ World Executive Colombo Hotels and City Guide Archived 2016-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Indrapala, Karthigesu (2007). The evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils in Sri Lanka C. 300 BCE to C. 1200 CE. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa. p. 70. ISBN 978-955-1266-72-1.

- ^ Gair, James (1998). Studies in South Asian Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-509521-0.

- ^ John, Still (1996). Index to the Mahawansa:Together with Chronological Table of Wars and Genealogical Trees. AES. p. 85. ISBN 978-81-206-1203-7.

- ^ Prof. Manawadu, Samitha. "Cultural Routes of Sri Lanka As Extensions of International Itineraries : Identification of Their Impacts on Tangible & Intangible Heritage" (PDF). p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d "European Encroachment and Dominance:The Portuguese". Sri Lanka: A Country Study. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ Ross, Russell R.; Savada, Andrea Matles (1990). Sri Lanka: A Country Study. Defence Dept., Army. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-16-024055-3.

- ^ a b "European Encroachment and Dominance: The Dutch". Sri Lanka: A Country study. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ a b Ross, Russell R.; Savada, Andrea Matles (1990). Sri Lanka: A Country Study. Defense Dept., Army. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-16-024055-3.

- ^ "European Encroachment and Dominance: The British Replace the Dutch". Sri Lanka: A Country study. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ a b c Adrian, Wijemanne (1996). War and Peace in Post-Colonial Ceylon 1948–1991. Orient Longman. p. 111. ISBN 978-81-250-0364-9.

- ^ "Administrative Districts of the Colombo Municipal Council". Colombo Municipal Council. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.[circular reference]

- ^ GoAbroad.com, Embassies located in Sri Lanka Archived 2016-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b The lake in the middle of Colombo Archived 2007-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, Lanka Library

- ^ 35th boat race and 31st Regatta: Oarsmen of Royal and S. Thomas' clash on Beira waters Archived 2014-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, Daily News, October 10, 2003

- ^ "Colombo weather". Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Colombo". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Colombo". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 8 December 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Colombo Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (FTP). Retrieved 19 November 2016. (To view documents see Help:FTP)

- ^ "Klimatafel von Colombo (Kolamba) / Sri Lanka (Ceylon)" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "Gangaramaya Temple". John Keells Hotels Group. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "Department of Census and Statistics Sri Lanka – Population by ethnicity and district according to Divisional Secretary's Division, 2012". Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Department of Census and Statistics". Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2016., Additional source "The case of Colombo, Sri Lanka" (PDF). Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

The totals are calculated through enumerations made from Colombo Divisional Secretariat and the Thimbirigasyaya Divisional Secretariat, which is also part of Colombo Municipal Council.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Port of Colombo Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine. World Port Source.

- ^ "Department of Census and Statistics Sri Lanka – Population by divisional secretariat division, religion and sex 2012". Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Colombo Municipal Council". Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Colombo UNP list rejected Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, February 16, 2006

- ^ Independent group wins CMC Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, May 21, 2006

- ^ Rotational mayors as Colombo gets trishaw driver as her first citizen Archived 2007-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, Sunday Times, May 28, 2006

- ^ "The Supreme Court of Sri Lanka". Justice Ministry. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Ministries of Sri Lanka Government". Government of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Prime Minister's Office, Sri Lanka". www.pmoffice.gov.lk. Archived from the original on 11 September 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Colombo Economy". Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Press release 20010712" (PDF). CBSL. 10 July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ "Executive Summary The Colombo Metropolitan (CM) area" (PDF). Ministry of Defence & Urban Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "World Airline Directory." Also ranked of the best land in the world of WWNEconomy Flight International. 14–20 March 1990 "Airlift International" 57 Archived 2011-08-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Organizational Structure Archived 2007-08-27 at the Wayback Machine, Ministry of Defence, Sri Lanka

- ^ Gunawardena, Edward. "The drama behind the arrest of Sepala Eknayake". The Island-Saturday Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011.

- ^ "CNS Reports". Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Archived from the original on 3 October 2001. Retrieved 3 October 2001.

- ^ "Travel Warning, United States Department of State". Archived from the original on 22 September 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Jane's Sentinel examines the success of the LTTE in resisting the Sri Lankan forces Archived April 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine[circular reference]

- ^ President orders SB's release Archived October 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, LankaNewspapers.com, February 16, 2006

- ^ "Colombo". lanka-houses.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Cost of Living in Colombo, Sri Lanka – PropertyInLanka.com". Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Seibt, Sébastian (24 March 2019). "In Sri Lanka, the new Chinese Silk Road is a disappointment". France 24.

- ^ China 'Silk Road' Project in Sri Lanka Delayed as Beijing Toughens Stance

- ^ Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: Chinas neue Seidenstraße. (2017).

- ^ Jean-Marc F. Blanchard "China's Maritime Silk Road Initiative and South Asia" (2018) pp 55.

- ^ Sri Lanka 'key component' in 21st Century Maritime Silk Road: China

- ^ Hasintha Weragala, Things to do in Sri Lanka (27 November 2018). "Guide map of bus terminals in Colombo". thingstodoinsrilanla.lk. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "A Speedy and safe journey to Galle". Dailynews.lk. 16 August 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ Gamini Gunaratna, Sri Lanka News Paper by LankaPage.com (LLC) (7 November 2011). "Nearly half of the work completed on outer circular highway around Sri Lankan capital". Colombopage.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ Tuticorin-Colombo ferry sets sail Archived 2016-10-03 at the Wayback Machine. Times of India. (2011-06-14).

- ^ "Princess Alexandra's Visit". Archived from the original on 13 April 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Historical Overview of Education in Sri Lanka, The British Period: (1796–1948)". Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b Harsha, Aturupane; Paul Glewwe; Wisniewski Suzanne (July 2007). "The Impact of School Quality, Socio-Economic Factors and Child Health on Students' Academic Performance: Evidence from Sri Lankan Primary Schools" (PDF). Colombo: World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ Harsha, Aturupane; Paul Glewwe; Wisniewski Suzanne (February 2005). Treasures of the Education System in Sri Lanka: Restoring Performance, Expanding Opportunities and Enhancing Prospects (PDF). Colombo: World Bank. ISBN 978-955-8908-14-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ a b "History of the University of Colombo". Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d Faz (19 February 2006). "Colombo Fort". F's Place. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Tintagel, Colombo". Red Dot Tours. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ Ramerini, Marco. "Asia. Dutch Colonial Remains 16th-18th centuries". Colonial Voyage. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ a b Venerable Mahinda. "Significance of Vesak". BuddhaNet. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ "Nelum Pokuna". Daily Mirror. 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Prins, Stephen. "A National Treasure". Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ "History of Colombo National Museum". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ "History of Colombo National Museum". Retrieved 22 November 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ceylon, the Land of Eternal Charm, Ali Foad Toulba (Asian Educational Services) p.237 ISBN 9788120614949

Further reading

[edit]The following books contain major components on Colombo:

- Changing Face of Colombo (1501–1972): Covering the Portuguese, Dutch and British Periods, by R.L. Brohier, 1984 (Lake House, Colombo)

- The Port of Colombo 1860–1939, K. Dharmasena, 1980 (Lake House, Colombo)

- Decolonizing Ceylon: Colonialism, Nationalism and the Politics of Space in Sri Lanka, by Nihal Perera, 1999 (Oxford University Press)

- the Essential guide for Colombo and its region, Philippe Fabry, Negombo, Viator Publications, 2011, 175 p., ISBN 978-955-8736-09-8

- The impact of the Tsunami on households and vulnerable groups in two districts in Sri Lanka : Galle and Colombo, Swarna Jayaweera, Centre for Women's Research, Colombo, 2005

- Patterns of Community Structure in Colombo, Sri Lanka, An investigation of Contemporary Urban Life in South Asia, Neville S. Arachchige-Don, University Press, Maryland, 1994

- Colombo, Carl Muller, Penguin Books, New Delhi, 1995

Colombo

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Linguistic origins and historical names

The name "Colombo" derives primarily from the ancient Sinhalese term kolamba, an old word signifying a "port" or "ferry," as referenced in the 13th-century Sinhala grammar Sidatsangarava.[5] This etymology aligns with the site's role as a longstanding harbor facilitating maritime trade, with roots traceable to the medieval Kotte Kingdom where it was known as Kolomtota, denoting the port area.[6] An alternative derivation posits origins in the classical Sinhala phrase kolon thota, meaning "port on the Kelani River," reflecting the geographical proximity to the river's estuary and its utility for ferrying goods.[7] Portuguese explorers adapted this to "Colombo" upon their arrival in 1505, marking the first European recording of the name in written accounts of the region.[7] Early references in non-local records include those from Arab traders, who by the 8th century CE identified the vicinity as a key cinnamon export hub, though without direct naming consistency; some Tamil traditions recall variants like Kollam-patuna or Ko'lamba, suggesting possible Dravidian linguistic overlays on the Sinhalese base, yet Sinhala sources provide the most direct philological linkage.[8] Claims of Sanskrit influence, such as through terms like kolamba implying a leafy grove or ford, remain speculative and lack primary textual corroboration beyond shared Indo-Aryan roots in regional nomenclature.[9]History

Pre-colonial and early settlement

The region of modern Colombo, situated on Sri Lanka's southwestern coast amid mangrove swamps and river estuaries, featured small indigenous settlements primarily consisting of fishing communities and spice gatherers during the protohistoric and early historic periods. Archaeological evidence from broader Sri Lankan coastal sites indicates human activity linked to Iron Age developments around the 3rd century BC, including trade-oriented ports with artifacts paralleling those at Godavaya, where Indo-Roman pottery and coins attest to early maritime exchanges. However, direct excavations in urbanized Colombo reveal limited pre-3rd-century AD remains due to later overbuilding, suggesting the area supported sparse, subsistence-based habitation under the influence of inland Sinhalese polities.[10][11] Under the Anuradhapura Kingdom (c. 377 BC–1017 AD), the Colombo vicinity contributed to island-wide trade networks as a secondary coastal outpost, facilitating the export of cinnamon harvested from adjacent wet-zone forests, alongside gems mined inland and elephants captured for regional markets. These commodities were transported via riverine routes to larger emporia, underscoring the area's economic integration into Sinhalese hydraulic and mercantile systems without developing into a primary urban center. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century AD) documents Taprobane (Sri Lanka) as a source of pearls, gems, tortoise shell, and spices traded with Roman merchants, implying southwestern ports like those near Colombo handled ancillary shipments amid dominant northern hubs such as Mantai.[12][13] During the Polonnaruwa Kingdom (1056–1232 AD), the region sustained its role in cinnamon procurement and elephant exports, with interactions expanding to Arab traders who frequented southwestern anchorages for spices before establishing more formal networks. These exchanges relied on indigenous Sinhalese oversight, with no evidence of large-scale foreign colonization, maintaining the area's character as a resource-extraction zone rather than a fortified settlement until the rise of the Kotte Kingdom in the 14th century.[12][14]Portuguese colonial period (1518–1658)

The Portuguese, following their initial exploratory voyages to Ceylon in 1505, received permission from the king of Kotte to erect a wooden fort in Colombo in 1518, marking the onset of formalized colonial control over the harbor as a strategic trading entrepôt. This structure, initially modest and later reinforced with stone ramparts, safeguarded shipments of cinnamon, elephants, gems, and areca nuts bound for Lisbon, while enabling the enforcement of trade concessions that bypassed local intermediaries.[15][16] Colombo's role expanded as the Portuguese imposed a royal monopoly on cinnamon production and export, compelling Sinhalese peasants through quotas and punitive oversight to harvest and peel bark from coastal groves, often under duress that blurred into forced labor practices amid inadequate compensation. Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries, arriving from the 1540s, proselytized aggressively, constructing chapels within the fort precincts and offering exemptions from corvée duties to converts, though mass conversions remained limited outside urban enclaves due to entrenched Buddhist loyalties.[17][18][19] Tensions with the Kotte kingdom escalated into intermittent warfare, as rival princes exploited dynastic fractures—exemplified by the 1521 fratricidal partition of Kotte—to ally against or submit to Portuguese captains, who razed villages and extracted tribute to quell uprisings. By the mid-16th century, Colombo had evolved into a garrisoned hub with rudimentary infrastructure, including warehouses and a customs house, yet this development served extractive ends, yielding annual cinnamon cargoes valued at over 6,000 cruzados while fueling local resistance that tied down Portuguese forces.[20][21]Dutch colonial period (1658–1796)

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) forces, allied temporarily with the Kingdom of Kandy, besieged Colombo Fort and captured it from the Portuguese on May 12, 1656, after a seven-month siege, marking the beginning of Dutch control over the city despite the formal end of Portuguese presence island-wide in 1658.[22][23] Unlike the Portuguese emphasis on religious conversion and fortification for territorial dominance, the Dutch prioritized commercial extraction, leveraging Colombo as a key entrepôt for exporting spices while minimizing costly missionary endeavors.[24][25] The VOC established a monopoly on cinnamon production and trade in Ceylon's southwestern coastal regions, which the Dutch expanded after 1658 by controlling cinnamon-growing lands and export points, generating substantial revenues that funded further infrastructure but often through forced labor systems like rajakariya.[25] This commerce-oriented approach yielded efficiency gains over Portuguese mismanagement, as Dutch administrative records and standardized shipping routes increased spice exports to Europe, with cinnamon comprising a primary commodity handled via Colombo's harbor.[26] Post-capture, the Dutch rebuilt Colombo's fortifications, transforming the Portuguese-era bastions into a structured military quarter in the western fort area while designating eastern spaces for civilian and commercial use, enhancing defense against potential Kandy incursions.[27] They also initiated canal networks, including extensions from the western system that linked Colombo to inland areas, facilitating spice transport and irrigation but primarily serving VOC logistical needs over local welfare.[25] The Dutch introduced Roman-Dutch law as the basis for civil administration in captured territories like Colombo, codifying property, inheritance, and contract rules derived from 17th-century Dutch jurisprudence blended with Roman principles, elements of which persisted in Sri Lankan legal practice post-independence due to their pragmatic applicability in colonial commerce.[28] Demographic changes included the settlement of Malay soldiers and families recruited by the VOC from Indonesian territories, who participated in anti-Portuguese campaigns such as the Colombo siege and numbered around 2,200 by the early 18th century, forming a loyal garrison community in and around the city that bolstered Dutch military presence with reduced reliance on European troops.[29] This influx contrasted with Portuguese-era forced conversions, as Dutch policy favored economic utility over evangelization, leading to less disruption of local Buddhist and Hindu practices in urban Colombo.[25]British colonial period (1796–1948)

The British East India Company forces, under the direction of the Madras Presidency, captured Colombo from the Dutch on 15 February 1796 after a brief siege, with Dutch Governor van Angelbeck surrendering the coastal territories including the fort and harbor.[30] This marked the transition of Ceylon to British administration, initially as a temporary conquest amid the Napoleonic Wars, with Colombo established as the primary administrative and commercial center.[31] The British retained the Dutch-era fortifications in the Fort area initially for defense but began demolishing walls and bastions from the 1860s onward to enable urban expansion, paving streets like York Street and constructing administrative buildings, barracks, and warehouses to support growing trade.[32] By the late 19th century, the Fort had evolved into a bustling European-style quarter with clock towers, hotels, and offices, reflecting colonial priorities of control and commerce over indigenous settlement patterns.

![Independence Memorial Hall, Colombo][float-right] Upon achieving independence from Britain on 4 February 1948, Ceylon (renamed Sri Lanka in 1972) retained Colombo as its executive, judicial, and commercial capital, serving as the focal point for early nation-building efforts amid a plantation-based export economy dominated by tea, rubber, and coconut.[41] The city's port handled over 90% of the island's trade, underscoring its role in sustaining foreign exchange earnings essential for post-colonial development, though urban infrastructure strained under population pressures from rural-urban migration.[42] The 1956 election of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike's Sri Lanka Freedom Party marked a pivot toward nationalist and socialist policies, including the Official Language Act—commonly known as the Sinhala Only Act—which designated Sinhala as the sole official language, sidelining Tamil and English despite Tamil speakers comprising about 20% of the population.[43] This measure, intended to empower the Sinhalese majority, triggered immediate protests in Colombo and galvanized Tamil opposition, fostering ethnic polarization that manifested in urban demonstrations and a gradual erosion of merit-based civil service recruitment favoring Sinhala speakers from rural areas.[44] Subsequent governments under Sirimavo Bandaranaike expanded nationalizations, seizing foreign-owned tea estates in 1971 and banks like the Bank of Ceylon's expansion into private institutions by 1968, aiming for self-reliance but resulting in bureaucratic inefficiencies, production shortfalls, and market distortions that hampered Colombo's commercial dynamism.[45] These closed-economy strategies, coupled with import controls, contributed to chronic shortages and a GDP growth averaging under 3% annually from 1956 to 1977, exacerbating urban unemployment rates that reached 20-25% among educated youth by the early 1970s.[46] Colombo's urban fabric expanded modestly, with the metropolitan population rising from approximately 500,000 in 1946 to over 1 million by 1981, driven by industrial hubs like textiles and food processing but constrained by land reforms and state-led housing initiatives that prioritized rural equity over city planning. Policy failures culminated in the 1971 Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) insurrection, where radicalized Sinhalese youth, disillusioned by job scarcity and perceived elite capture, launched coordinated attacks on police stations to seize arms, reflecting causal links between socialist distortions, youth bulge demographics, and ideological indoctrination rather than mere economic grievance alone.[47] The uprising, suppressed within months with over 10,000 arrests, highlighted Colombo's vulnerability as a governance nerve center, prompting fortified security measures. In 1978, amid decongesting efforts, Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte was designated the administrative capital, preserving Colombo's commercial primacy while relocating parliamentary functions by 1982.[48]Civil War era and ethnic conflicts (1983–2009)

The anti-Tamil riots known as Black July erupted in Colombo on July 24, 1983, following the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) ambush that killed 13 Sri Lankan soldiers on July 23 in Jaffna, precipitating widespread violence against Tamil civilians across the city and country. Mobs, often abetted by elements of the security forces and Sinhalese nationalist groups, targeted Tamil-owned businesses, homes, and individuals, resulting in an estimated 300 to 3,000 Tamil deaths nationwide, with Colombo bearing a significant portion of the destruction including the burning of Tamil commercial districts like Pettah. The riots displaced over 150,000 Tamils from Colombo, many fleeing to refugee camps or abroad, and inflicted economic damage valued at approximately $300 million through the systematic looting and arson of Tamil enterprises. This event marked the onset of intensified ethnic conflict, transforming Colombo from a multicultural hub into a flashpoint for retaliatory LTTE operations.[49][50] Throughout the civil war, the LTTE designated Colombo as a primary target for suicide bombings and truck attacks aimed at undermining government control and Sinhalese morale, conducting over 200 such operations nationwide by 2009, with dozens striking the capital directly. Notable incidents included the January 31, 1996, truck bombing of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, where an LTTE operative rammed a explosive-laden vehicle into the complex, killing 91 civilians and injuring over 1,400 while causing $42 million in structural damage to the financial district. Other attacks, such as the July 1997 Aranayake bus bombing en route to Colombo (killing 40) and multiple 2006-2008 suicide strikes on military and civilian targets in the city, contributed to hundreds of civilian deaths in Colombo alone, with LTTE tactics prioritizing high-casualty urban assaults to compensate for battlefield losses. These operations, documented in international reports, reflected the LTTE's strategy of asymmetric warfare, though they often blurred lines between military and civilian targets, exacerbating ethnic animosities.[51][52][53] In response, the Sri Lankan government imposed stringent security measures in Colombo, including pervasive checkpoints, identity verification for Tamils, vehicle searches to counter undercarriage bombs, and frequent curfews following major attacks, which militarized daily life and restricted movement. These countermeasures, while reducing some attack frequencies, led to temporary demographic shifts as internally displaced persons (IDPs)—primarily Tamils fleeing northern fighting—surged into Colombo, swelling urban slums and straining housing and services, with over 100,000 IDPs registered in the Western Province by the mid-2000s before partial relocations. Economic activity in Colombo suffered recurrent disruptions, with curfews halting commerce for days after bombings like the 1996 Central Bank incident, contributing to broader war-related losses estimated at billions in GDP nationwide, though Colombo's port and financial sectors remained vital despite vulnerabilities. By 2009, as LTTE operations waned, these measures had fortified the city but at the cost of civil liberties and ethnic trust.[54][55][56]Post-war reconstruction and economic challenges (2009–present)

Following the conclusion of the Sri Lankan civil war in May 2009, Colombo underwent accelerated urban reconstruction and infrastructure expansion to bolster its role as the commercial capital. Key initiatives included the Colombo Port City project, announced in 2011 and commencing reclamation works in September 2014, which created 269 hectares of artificial land for mixed-use development, financed primarily by China Harbour Engineering Company under a $1.4 billion investment.[57] Complementary efforts encompassed high-rise constructions in the central business district and enhancements to connectivity, such as the Colombo-Katunayake Expressway extensions, driving rapid urbanization with built-up areas expanding significantly post-2009 due to foreign capital inflows.[58] Tourism recovery further supported economic momentum, with Colombo serving as the primary gateway; national arrivals surged from 447,140 in 2009 to 2,333,796 by 2018, boosting hotel developments and service sectors in the city.[59] These advancements, however, coincided with accumulating fiscal strains from debt-financed projects, mirroring national trends where external borrowings for infrastructure escalated. Chinese loans, constituting about 10% of Sri Lanka's total foreign debt by 2021 but tied to high-profile ventures like Port City, exemplified the reliance on opaque financing that prioritized prestige over viability, contributing to overall debt sustainability issues alongside domestic policy errors such as 2019 tax reductions that widened deficits.[60] By early 2022, Colombo faced dire shortages in essentials like fuel and electricity amid forex reserves dropping below $50 million, precipitating the country's first sovereign default on April 12, 2022, with $51 billion in external obligations restructured amid GDP contraction of 7.8% that year.[61] Urban vulnerabilities amplified the crisis, as the city's dense population grappled with inflation exceeding 70% and supply chain disruptions.[62] Public discontent peaked in the Aragalaya movement, igniting on March 31, 2022, at Galle Face Green in Colombo, where protesters decried elite corruption, fiscal mismanagement, and the Rajapaksa family's influence, leading to widespread demonstrations that forced President Gotabaya Rajapaksa's resignation on July 13 after the storming of his official residence.[63] The protests highlighted systemic failures in governance, including nepotism and unsustainable borrowing, rather than attributing the crisis solely to external lenders, as evidenced by domestic revenue shortfalls predating heavy Chinese engagement.[64] The 2022 upheaval paved the way for political realignment, culminating in the September 21, 2024, presidential election where National People's Power (NPP) leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake secured 42% of votes, defeating establishment candidates amid vows to combat corruption and renegotiate debts.[65] His coalition's subsequent parliamentary triumph on November 14, 2024, capturing 159 seats, reflected Colombo's electorate's rejection of prior regimes, enabling reforms like anti-graft probes and fiscal stabilization, though implementation faces hurdles from entrenched interests and lingering debt burdens projected to require $5-6 billion annually in servicing post-restructuring.[66][67] By 2025, early NPP measures have stabilized inflation below 5%, but Colombo's reconstruction legacy underscores the tension between ambitious development and prudent economics.[68]Geography

Location, topography, and urban layout

Colombo lies on the southwestern coast of Sri Lanka at coordinates 6°56′N 79°51′E, positioned at the delta of the Kelani River as it discharges into the Indian Ocean.[69][70] The city center stands approximately 32 kilometers south of Bandaranaike International Airport, facilitating connectivity while exposing the urban expanse to riverine influences from the north. Its coastal alignment spans roughly 10 kilometers, encompassing harbor facilities and beaches that define its maritime orientation.[71] The topography consists of a low-lying alluvial plain, with most areas elevated less than 5 meters above mean sea level, rendering the terrain predominantly flat and prone to waterlogging.[72] This configuration, coupled with subsidence in reclaimed zones, heightens susceptibility to inundation, as evidenced by recurrent flooding that submerges up to 20% of the municipal area during peak events.[73] Colombo's urban layout is organized into 15 administrative divisions under the Colombo Municipal Council, covering 37 square kilometers, with zones such as Fort (commercial hub) and Cinnamon Gardens (diplomatic enclave) exemplifying functional segregation.[74] Population density in core districts averages 24,000 persons per square kilometer, surpassing 40,000 per square kilometer in high-density pockets like Pettah, straining infrastructure amid constrained topography.[75] The adjacent Colombo Port City, comprising 269 hectares of reclaimed land from marine sediments, extends the layout seaward but elevates flood exposure, with modeling indicating amplified surge penetration under projected sea-level increments of 0.5 meters by 2100.[76]Climate and environmental factors

Colombo features a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen classification Am), with consistently high temperatures averaging between 27°C and 31°C throughout the year and little diurnal or seasonal variation due to its equatorial proximity.[77] Relative humidity remains elevated at 75-90%, contributing to a muggy atmosphere, while average annual sunshine totals around 2,500 hours.[78] Precipitation totals approximately 2,387 mm annually, distributed bimodally across two monsoon periods: the Southwest monsoon (Yala), delivering heavy rains from May to September (peaking at 300-400 mm monthly), and the Northeast monsoon (Maha), from October to January (with November often seeing over 200 mm). [77] Drier inter-monsoon phases occur in February-March and briefly in January-February, though isolated showers persist year-round due to convective activity.[78] Flooding poses a recurrent environmental hazard, driven by intense monsoon downpours overwhelming the city's antiquated drainage infrastructure and low-lying topography, compounded by upstream siltation in the Kelani River basin. The 2010 event, triggered by over 440 mm of rain in a single day on November 10, inundated low-income areas, displacing more than 213,000 residents and causing at least 50 deaths citywide.[79] A comparable 2020 flood episode, amid prolonged Northeast monsoon rains, affected tens of thousands in Colombo's suburbs, with damages exceeding prior events due to clogged canals from urban waste.[80] These incidents highlight causal factors like impervious surface expansion—reducing natural infiltration by up to 50% in densified zones—over broader climatic shifts.[81] Urban heat island intensification has emerged post-2000 from accelerated concretization and vegetation loss, elevating local surface temperatures beyond regional baselines. Landsat-derived analyses indicate a rise in "very hot" land surface spots from 30.3% of the metropolitan area in 1997 to 37.2% by 2017, correlating with a 20-30% increase in built-up cover that traps heat via reduced evapotranspiration.[82] Ground observations post-2000 confirm mean air temperatures 1-2°C higher in central Colombo versus peri-urban greenspaces, attributable to anthropogenic landscape alterations rather than isolated meteorological variance.[83] Mitigation efforts, such as wetland restoration, have shown limited efficacy against these localized thermal gradients without addressing core drainage and land-use deficiencies.[84]Demographics

Population size and growth trends

The population of Colombo's city proper, encompassing the Colombo Municipal Council area of approximately 37 square kilometers, was recorded at 561,314 in the 2012 census conducted by Sri Lanka's Department of Census and Statistics.[85] Estimates for 2025 place this figure at around 648,000, reflecting modest urban expansion driven by internal migration and natural increase.[86] The broader Colombo metropolitan region, including adjacent suburbs in the Western Province such as Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia and Colombo District, is estimated to house about 5.6 million people, accounting for over a quarter of Sri Lanka's total population.[87] Annual population growth in Colombo has averaged approximately 0.8% since 2012, lower than pre-war rates due to decelerating fertility and net out-migration amid economic pressures, as extrapolated from district-level census data showing Colombo District's population rising from 2.32 million in 2012 to 2.37 million in the 2024 preliminary census.[88] [89] This contrasts with higher growth in the post-civil war period (2009–2012), when rural-to-urban migration from war-affected northern and eastern provinces boosted Colombo's influx by an estimated 5–7% through internal relocation for employment and reconstruction opportunities.[85] The 2022 economic crisis reversed these trends, prompting significant out-migration from Colombo, with over 1 million Sri Lankans departing the country for foreign employment or relocation—many originating from urban centers like Colombo—leading to a temporary dip in local growth rates to near zero in affected demographics.[90] Recovery has been uneven, with remittances partially offsetting losses but failing to fully restore pre-crisis inflows. High population density in the city proper, exceeding 17,000 persons per square kilometer based on 2012 census baselines and subsequent projections, has exacerbated housing shortages, estimated at 27,000 units in 2022 due to supply lagging demand by 3 percentage points annually.[91] [85] These pressures highlight urban-rural dynamics, where Colombo continues to serve as a magnet for provincial labor despite periodic reversals.Ethnic, linguistic, and religious composition