Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

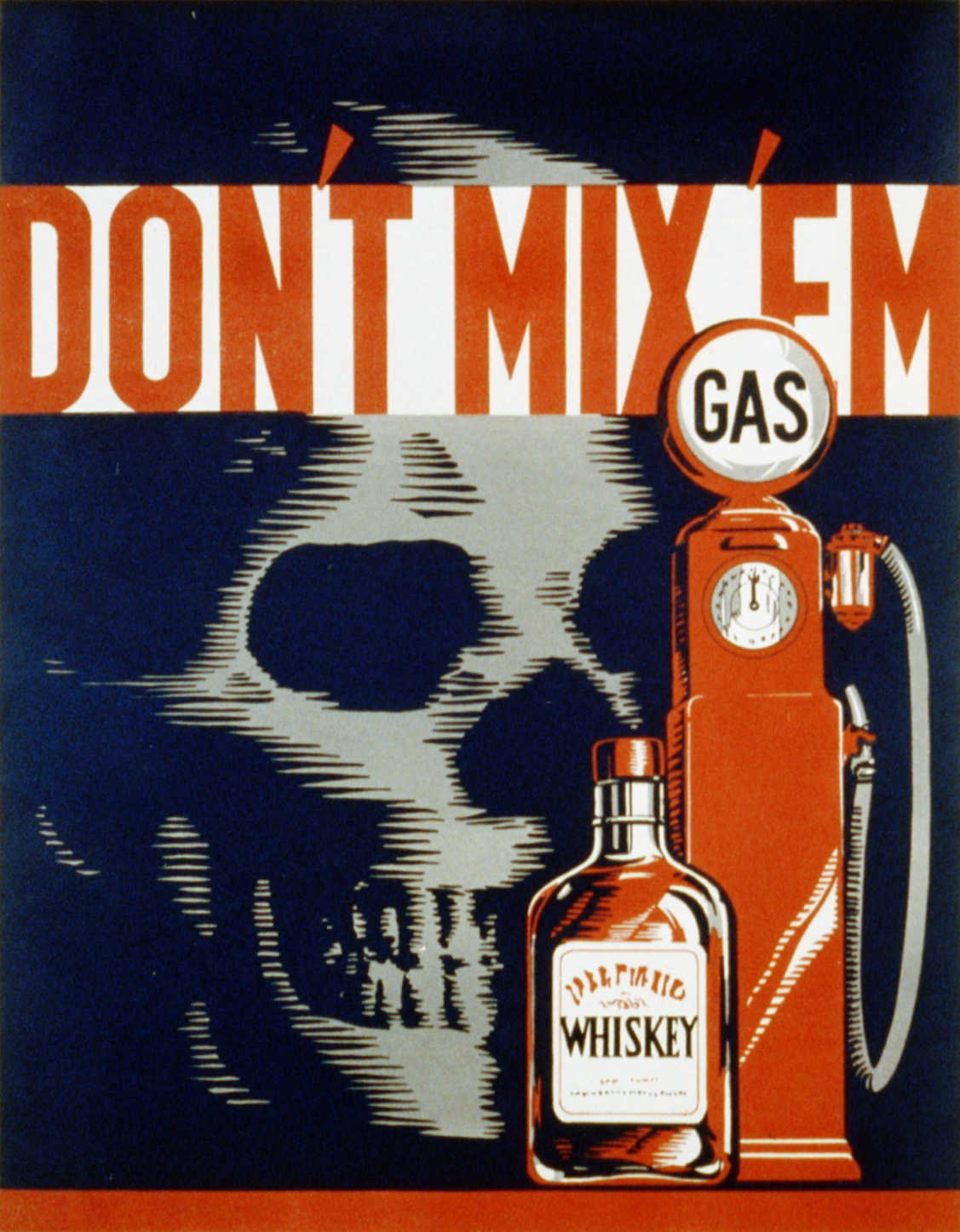

Driving under the influence

View on Wikipedia

Driving under the influence (DUI) is the crime of driving, operating, or being in control of a vehicle while one is impaired from doing so safely by the effect of either alcohol (see drunk driving) or some other drug, whether recreational or prescription (see drug-impaired driving).[1] Multiple other terms are used for the offense in various jurisdictions.

Terminology

[edit]The name of the offense varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and from legal to colloquial terminology. In various jurisdictions the offense is termed "driving under the influence" [of alcohol or other drugs] (DUI), "driving under the influence of intoxicants" (DUII), "driving while impaired" (DWI), "impaired driving", "driving while intoxicated" (DWI), "operating while intoxicated" (OWI), "operating under the influence" (OUI), "operating [a] vehicle under the influence" (OVI), "drunk in charge", or "over the prescribed limit" (OPL) (in the UK). Alcohol-related DUI is referred to as "drunk driving", "drunken driving", or "drinking and driving" (US), or "drink-driving" (UK/Ireland/Australia). Cannabis-related DUI may be termed "driving high", and more generally drug-related DUI may be referred to as "drugged driving", "driving under the influence of drugs" (DUID), or "drug-impaired driving".[citation needed]

In the United States, the specific criminal offense is usually called driving under the influence, but states may use other names for the offense including "driving while intoxicated" (DWI), "operating while impaired" (OWI) or "operating while ability impaired", and "operating a vehicle under the influence" (OVI).[2]

Definition

[edit]In typical usage of the terms DUI, DWI, OWI, and OVI, the offense consists of driving a vehicle while affected by alcohol or drugs.[3][4] However, in the majority of US states, the criminal offense may not involve actual driving of the vehicle but rather may broadly include operating or being physically in control of a motor vehicle while under the influence, even if the person charged is not in the act of driving.[5][6] For example, individuals found in the driver's seat of a car while intoxicated and holding the car keys, even while parked, may be charged with DUI because they are in control of the vehicle.[7] In contrast, California only makes it illegal to drive a motor vehicle while under the influence, requiring actual "driving". "The distinction between these two terms is material, for it is generally held that the word 'drive,' as used in statutes of this kind, usually denotes movement of the vehicle in some direction, whereas the word 'operate' has a broader meaning so as to include not only the motion of the vehicle but also acts which engage the machinery of the vehicle that, alone or in sequence, will set in motion the motive power of the vehicle."[8]

Many DUI laws also apply to motorcycling, boating, piloting aircraft, use of mobile farm machinery such as tractors and combine harvesters, riding horses or driving a horse-drawn vehicle, cycling, or skateboarding, possibly with different BAC level than regular driving.[9][10][11] In some jurisdictions, there are separate charges depending on the vehicle used. In Washington state, for instance, BUI (bicycling under the influence) laws recognize that intoxicated cyclists are likely to primarily endanger themselves. Accordingly, law enforcement officers are empowered only to protect the cyclist by impounding the bicycle rather than filing DUI charges.[12]

George Smith, a London Taxi cab driver, ended up being the first person to be convicted of driving a motor vehicle while intoxicated, on September 10, 1897, under the "drunk in charge" provision of the 1872 Licensing Act. He was fined 25 shillings, which is equivalent to £179 in 2023.[13]

Alcohol

[edit]

Drunk driving (or drink-driving in British English[15]) is the act of driving under the influence of alcohol. A small increase in the blood alcohol content increases the relative risk of a motor vehicle crash.[16] In the United States, alcohol is involved in 30% of all traffic fatalities.[17] It is not known nationally how many people are killed each year in crashes involving drug-impaired drivers because of data limitations,[18] but one study of drivers who were seriously injured in crashes found that 23.6% of drivers were positive for alcohol and 12.2% were positive solely for alcohol.[19]

Other drugs

[edit]For drivers suspected of drug-impaired driving, drug testing screens are typically performed in scientific laboratories so that the results will be admissible in evidence at trial. Due to the overwhelming number of impairing substances that are not alcohol, drugs are classified into different categories for detection purposes. Drug impaired drivers still show impairment during the battery of standardized field sobriety tests, but there are additional tests to help detect drug impaired driving. In the US, one study found that 25.8% of drivers seriously injured in crashes tested positive for cannabinoids, 13.6% tested positive solely for cannabinoids, and 24.6% tested positive for a drug other than alcohol or cannabis.[19]

Recreational drugs

[edit]Drivers who have smoked or otherwise consumed cannabis products such as marijuana or hashish can be charged and convicted of impaired driving in some jurisdictions. A 2011 study in the B.C. Medical Journal stated that there "...is clear evidence that cannabis, like alcohol, impairs the psychomotor skills required for safe driving." The study stated that while "[c]annabis-impaired drivers tend to drive more slowly and cautiously than drunk drivers,... evidence shows they are also more likely to cause accidents than drug and alcohol-free drivers".[20] A more recent 2023 study found that when compared to alcohol, "the impairment effect of marijuana on driving is relatively mild" since drivers using cannabis "drive slower, avoid overtaking other vehicles, and increase following distances."[21] In Canada, police forces such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police have "...specially trained drug recognition and evaluation [DRE] officers... [who] can detect whether or not a driver is drug impaired, by putting suspects through physical examinations and co-ordination tests.[20] In 2014, in the Canadian province of Ontario, Bill 31, the Transportation Statute Law Amendment Act, was introduced to the provincial legislature. Bill 31 contains driver's license "...suspensions for those caught driving under the influence of drugs, or a combination of drugs and alcohol.[22] Ontario police officers "...use Standard Field Sobriety Tests (SFSTs) and drug recognition evaluations to determine whether the officer believes the driver is under the influence of drugs."[22] In the province of Manitoba, an "...officer can issue a physical coordination test. In B.C., the officer can further order a drug recognition evaluation by an expert, which can be used as evidence of drug use to pursue further charges."[22]

In the US state of Colorado, the state government indicates that "[a]ny amount of marijuana consumption puts you at risk of driving impaired." Colorado law states that "drivers with five nanograms of active tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in their whole blood can be prosecuted for driving under the influence (DUI). However, no matter the level of THC, law enforcement officers base arrests on observed impairment." In Colorado, if consumption of marijuana is impairing your ability to drive, "it is illegal for you to be driving, even if that substance is prescribed [by a doctor] or legally acquired."[23]

Prescription medications

[edit]Prescription medications such as opioids and benzodiazepines often cause side effects such as excessive drowsiness, and, in the case of opioids, nausea.[24] Other prescription drugs including antiepileptics and antidepressants are now also believed to have the same effect.[25] In the last ten years, there has been an increase in motor vehicle crashes, and it is believed that the use of impairing prescription drugs has been a major factor.[25] Workers are expected to notify their employer when prescribed such drugs to minimize the risk of motor vehicle crashes while at work.[citation needed]

If a worker who drives has a health condition which can be treated with opioids, then that person's doctor should be told that driving is a part of the worker's duties and the employer should be told that the worker could be treated with opioids.[26] Workers should not use impairing substances while driving or operating heavy machinery like forklifts or cranes.[26] If the worker is to drive, then the health care provider should not give them opioids.[26] If the worker is to take opioids, then their employer should assign them work which is appropriate for their impaired state and not encourage them to use safety sensitive equipment.[27]

Testing

[edit]Field sobriety testing

[edit]Field sobriety tests are a battery of tests used by police officers to determine if a person suspected of impaired driving is intoxicated with alcohol or other drugs. FSTs are primarily used in the United States, to meet "probable cause for arrest" requirements (or the equivalent), necessary to sustain a DWI or DUI conviction based on a chemical blood alcohol test. In the US, field sobriety tests are voluntary; however, some states mandate commercial drivers accept preliminary breath tests (PBT).[citation needed]

Drug Evaluation and Classification program

[edit]The Drug Evaluation and Classification program is designed to detect a drug impaired driver and classify the categories of drugs present in their system. The procedures are used post-arrest to gather evidence for trial, rather than for probable cause, as they would be difficult to conduct at the scene.[28]

Initially developed by the Los Angeles, California, Police Department in the 1970s, the DEC program breaks down detection into a twelve-step process that a government-certified Drug Recognition Expert (DRE) can use to determine the category or categories of drugs that a suspect is impaired by. The twelve steps are:

- Breath Alcohol Test

- Interview with arresting officer (who notes slurred speech, alcohol on breath, etc.)

- Preliminary evaluation

- Evaluation of the eyes

- Psychomotor tests

- Vital signs

- Dark room examinations

- Muscle tone

- Injection sites (for injection of heroin or other drugs)

- Interrogation of suspect

- Opinion of the evaluator

- Toxicological examination[29]

DREs are qualified to offer expert testimony in court that pertains to impaired driving on drugs.

The DEC program is recognized by all fifty states in the U.S., Canada, and the United Kingdom and DRE training in the use of the twelve-step [MS1] process is scientifically validated by both laboratory and field studies.[30]

Testing for cannabis

[edit]U.S. states prohibit the operation of a motor vehicle while under the influence of drugs, including marijuana.[31] For example, in Illinois it is illegal to operate a motor vehicle with a THC level of 5 nanograms or more per milliliter of whole blood or 10 nanograms or more per milliliter of other bodily substances.[32] Under that law, an individual can be arrested for driving under influence of cannabis at any THC level, including under the per se legal limits if an Officer believes the individual is impaired by cannabis.[32]

It can be important to perform testing soon after a traffic stop, as THC plasma levels decline significantly after the passage of one or two hours.[33] A number of companies are developing roadside THC breathalyzers that may be used by the police to help identify drivers impaired by the use of marijuana. Some nations use saliva swabs to test for THC levels at roadside, but questions remain about the reliability of saliva testing.[34]

Other charges

[edit]Child endangerment

[edit]In the US state of Colorado, impaired drivers may be charged with child endangerment if they are arrested for DUI with minor children in the vehicle.[35]

Wet reckless

[edit]"Wet reckless" is a term used informally when a driver takes a plea bargain, agreeing to plead guilty to reckless driving in exchange for the elimination of the drunk driving charge.[36] In California, a driver may not be charged or arrested for "wet reckless" driving, and the sole function of the charge is as a possible disposition following a plea bargain for a driver charged with DUI.[37]

Penalties

[edit]In the case of a crash, car insurance may be automatically declared invalid for the intoxicated driver; the drunk driver would be fully responsible for damages. In the American system, a citation for driving under the influence also causes a major increase in car insurance premiums.[38]

The German model serves to reduce the number of crashes by identifying unfit drivers and revoking their licenses until their fitness to drive has been established again. The medical-psychological assessment works for a prognosis of the fitness for drive in future, has an interdisciplinary basic approach, and offers the chance of individual rehabilitation to the offender.[39]

Worldwide

[edit]

The laws relating to DUI vary significantly between countries, particularly the thresholds at which a person is charged with a crime. In many countries, sobriety checkpoints (roadblocks of police cars where drivers are checked), driver's license suspensions, fines, and prison sentences for DUI offenders are used as part of an effort to deter impaired driving. In addition, many countries have prevention campaigns that use advertising to make people aware of the danger of driving while impaired and the potential fines and criminal charges, discourage impaired driving, and encourage drivers to take taxis or public transport home after using alcohol or other drugs. In some jurisdictions, a bar or restaurant that serves an impaired driver may face civil liability for injuries caused by that driver. In some countries, non-profit advocacy organizations, a well-known example being Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) run their own publicity campaigns against drunk or impaired driving.[citation needed]

US federal regulation

[edit]The United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) regulates many occupations and industries, and has a zero tolerance policy pertaining to the use of cannabis for any regulated employee whether he or she is on-duty or off-duty. Regardless of any State's DUI Statutes and DMV Administrative Penalties, a Commercial Driver's License "CDL" holder will have their CDL suspended for 1-year for a DUI arrest and will have their CDL revoked for life if they are subsequently arrested for driving impaired.[32]

European Union

[edit]In 2025, during the negotiation of the new rules for the European driving license an EU-wide two years probationary period was proposed without alcohol, but member states may have to apply stricter rules for driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs.[40]

See also

[edit]- Alcoholism

- Alcohol-related crime

- Breathalyzer

- Designated driver

- Driving laws

- Drug–impaired driving

- Drunk drivers

- Drunk walking

- DUI laws in California

- DWI court

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

- Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD)

- Mobile phones and driving safety

- National Motorists Association

- Open-container law

- Responsible drug use

- Driver's license: point system

- Zero tolerance

References

[edit]- ^ Walsh, J. Michael; Gier, Johan J.; Christopherson, Asborg S.; Verstraete, Alain G. (11 August 2010). "Drugs and Driving". Traffic Injury Prevention. 5 (3): 241–253. doi:10.1080/15389580490465292. PMID 15276925. S2CID 23160488.

- ^ Wanberg, Kenneth W.; Milkman, Harvey B.; Timkin, David S. (3 December 2004). Driving With Care:Education and Treatment of the Impaired Driving Offender-Strategies for Responsible Living: The Provider's Guide (1 ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 14. ISBN 9781412905961.

- ^ "driving under the influence". Cambridge English Dictionary. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ "DUI | the crime of driving a vehicle while drunk also: a person who is arrested for driving a vehicle while drunk". Merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Voas, Robert B.; Lacey, John H. (1989). Issues in the enforcement of impaired driving laws in the United States (PDF). Surgeon General's Workshop on Drunk Driving. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. pp. 136–156. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.553.1031. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2017.

- ^ Tekenos-Levy, Jordan (29 July 2015). "Impaired Driving in Canada: Cost and Effect of a Conviction". National College for DUI Defense. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Benikov, Alexander Y. (2012). "When Is an Arizona Drunk Driver Not a Driver: Zarogoza and Actual Physical Control". Phoenix Law Review. 6: 565.

- ^ State v. Graves (1977) 269 S.C. 356 [237 S.E.2d 584, 586–588, 586. fn. 8].

- ^ Rowling, Troy (14 October 2008). "In Mt Isa it's RUI: riding under the influence". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Pedestrian Safety". Police Department, University of Colorado. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017. ("[I]f you bicycle while intoxicated you will be held to the same standards as other motorists and may be issued a DUI.")

- ^ "Ore. skateboarder collides with van, charged with DUI". Crimesider. CBS News. 13 March 2013. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ McLeod, Ken (11 July 2013). "Bike Law University: Riding Under the Influence". League of American Bicyclists. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ "drink-driving". Collins Dictionary. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ "Why drunk drivers may get behind the wheel". Science Daily. 18 August 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Alcohol-Impaired Driving". NHTSA. 2018. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Impaired Driving: Get the Facts | Transportation Safety | Injury Center | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 19 July 2023. Archived from the original on 26 March 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ a b Thomas FD, Darrah J, Graham L, Berning A, Blomberg R, Finstad K, Griggs C, Crandall M, Schulman C, Kozar R, Lai J, Mohr N, Chenoweth J, Cunningham K, Babu K, Dorfman J, Van Heukelom J, Ehsani J, Fell J, Whitehill J, Brown T, Moore C (December 2022), Alcohol and Drug Prevalence Among Seriously or Fatally Injured Road Users (PDF), National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, DOT HS 813399, archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2024, retrieved 26 March 2024

- ^ a b "National Post". News.nationalpost.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Chen, Weiwei; French, Michael T. (7 September 2023). "Marijuana legalization and traffic fatalities revisited". Southern Economic Journal. 90 (2): 259–276. doi:10.1002/soej.12657. ISSN 0038-4038. Archived from the original on 11 January 2024. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Ontario to bring in stronger punishment for driving under influence of drugs". Ca.news.yahoo.com. 22 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Marijuana and Driving — Colorado Department of Transportation". Codot.gov. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Kaye, Adam M. (12 January 2013). "Basic Concepts in Opioid Prescribing and Current Concepts of Opioid-Mediated Effects on Driving". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (4): 525–32. PMC 3865831. PMID 24358001.

- ^ a b Sigona, Nicholas (13 October 2014). "Driving Under the Influence, Public Policy, and Pharmacy Practice". Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 28 (1): 119–123. doi:10.1177/0897190014549839. PMID 25312259. S2CID 45295600. Retrieved 16 April 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (February 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, archived from the original on 11 September 2014, retrieved 24 February 2014, which cites

- Weiss, MS; Bowden, K; Branco, F; et al. (2011). "Opioids Guideline". In Kurt T. Hegmann (ed.). Occupational medicine practice guidelines : evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers (online March 2014) (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. p. 11. ISBN 978-0615452272.

- ^ "The proactive role employers can take: Opioids in the Workplace" (PDF). National Safety Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "DRUG EVALUATION AND CLASSIFICATION TRAINING - ADMINISTRATOR'S GUIDE" (PDF). January 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Drug Evaluation and Classification Program. NHTSA. pp. Sev IV Pg. 5–6.

- ^ "Drug Evaluation and Classification Program (DECP) Annual Report 2018" (PDF). International Association of Chiefs of Police. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Walsh, J. Michael (2009). "A State-by-State Analysis of Laws Dealing With Driving Under the Influence of Drugs" (PDF). ems.gov. NHTSA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "2021 Illinois DUI Fact Book" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Marijuana-Impaired Driving : A Report to Congress" (PDF). Nhtsa.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Smith, Aaron (26 May 2017). "These companies are racing to develop a Breathalyzer for pot". Money.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "Child Endangerment Drunk Driving Laws" (PDF). MADD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "wet reckless". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Graham, Kyle (2011). "Facilitating Crimes: An Inquiry into the Selective Invocation of Offenses within the Continuum of Criminal Procedures". Lewis & Clark Law Review. 15: 667.

- ^ Tchir, Jason (10 June 2014). "How an impaired driving conviction can affect your car insurance rates". Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "The Medical Psychological Assessment: An Opportunity for the Individual, Safety for the Genera Public" (PDF). Archived from the original (PD) on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "EU ditches plans to allow 17-year-old trainee lorry drivers but learners still allowed to drink alcohol".

Further reading

[edit]- Barron H. Lerner (2011). One for the Road: Drunk Driving Since 1900. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

External links

[edit]Driving under the influence

View on GrokipediaDriving under the influence (DUI), also termed driving while impaired (DWI) or operating a vehicle under the influence of intoxicants, encompasses the control of a motor vehicle by an individual whose cognitive, perceptual, or psychomotor abilities are adversely affected by alcohol, illicit drugs, prescription medications, or combinations thereof, thereby elevating the probability of unsafe operation.[1][2] In jurisdictions such as the United States, statutory per se limits often designate a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.08% as presumptive evidence of impairment for non-commercial drivers aged 21 and older, though physiological and behavioral decrements manifest at substantially lower concentrations, with empirical analyses revealing a graded escalation in crash risk commencing near zero BAC.[3][4] Alcohol-impaired driving remains a principal contributor to roadway carnage, implicated in 32% of all U.S. traffic fatalities in 2022, totaling 13,524 deaths, while drug-impaired instances—predominantly involving cannabis, stimulants, or depressants—exhibit surging prevalence, with toxicology detecting substances in over 40% of fatally injured drivers in recent surveys, albeit presence alone does not invariably equate to acute impairment.[5][6] Drivers at a BAC of 0.08% face roughly fourfold heightened crash odds relative to sober counterparts, ballooning to twelvefold at 0.15%, a relationship corroborated by case-control investigations isolating alcohol's causal role in elevating single-vehicle collisions and overall accident severity.[3][7] Enforcement mechanisms, including breathalyzer thresholds and zero-tolerance provisions for juveniles, alongside countermeasures like sobriety checkpoints, have curbed incidences but confront challenges from evolving drug landscapes, such as post-legalization marijuana use, where self-reported impaired driving persists at elevated rates despite variable intoxication durations.[8][9] Defining characteristics include the disparity between observable intoxication and measurable substance levels, fueling debates over impairment-based versus concentration-based prosecutions, with data underscoring that even modest intoxication multiplicatively amplifies error rates in judgment, reaction time, and vehicle control.[4][10]

Historical Development

Origins in Early Automotive Era

The introduction of mass-produced automobiles, beginning with models like the Ford Model T in 1908, rapidly expanded personal mobility in the United States, increasing registered vehicles from about 194,000 in 1908 to over 23 million by 1930. This growth intersected with entrenched alcohol consumption norms, leading to early observations of impaired driving as a causal factor in accidents; rudimentary police reports from the 1910s documented cases where intoxicated operators contributed to fatalities, prompting initial municipal ordinances in cities like Chicago and New York to restrict driving by the inebriated.[11][12] New York enacted the nation's first state-level drunk driving statute in 1910, criminalizing operation of a motor vehicle while intoxicated, though prosecutions typically invoked broader charges such as reckless driving or manslaughter when deaths occurred, reflecting the era's reliance on observable impairment rather than chemical testing. By the 1930s, every state had adopted similar provisions, often embedded in general traffic codes, as empirical data from coroners' inquests and insurance investigations consistently linked alcohol to a substantial share of crashes—frequently estimated at 25% or more in urban areas based on witness testimonies and autopsy findings. These measures stemmed from first-hand accident causation analyses, where alcohol's disinhibiting effects were inferred from patterns like nighttime collisions and erratic vehicle paths.[12][13] The national Prohibition amendment from 1920 to 1933 temporarily curtailed alcohol-related incidents by limiting supply, with traffic safety records showing a measurable drop in impaired-driving crashes during enforcement peaks, as fewer drivers accessed intoxicants legally or via bootlegging risks. Repeal in 1933 reversed this trend, with post-Volstead accident rates rising amid renewed consumption, highlighting enforcement gaps in statutes that lacked specificity for impairment and relied on subjective judgments, thus underscoring the need for dedicated regulatory frameworks tied to observed causal risks.[12][14]Mid-20th Century Reforms and Standardization

Following World War II, rapid increases in automobile ownership and highway usage in the United States correlated with a surge in traffic fatalities, reaching over 40,000 annually by the mid-1960s, with alcohol involvement estimated in approximately 50% of nighttime crashes due to impaired judgment and reaction times documented in early epidemiological studies.[15][16] This rise exposed enforcement gaps, as pre-war laws relied on subjective officer observations rather than objective measures, leading to inconsistent prosecutions despite causal evidence from crash investigations linking blood alcohol concentrations above 0.05% to elevated collision risks.[17] The 1966 National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act marked a pivotal federal intervention, authorizing the creation of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and mandating state highway safety programs that addressed driver impairment, including requirements for analyzing alcohol content in fatal crash victims to inform policy.[18][19] These reforms standardized data collection on impairment factors, drawing on frameworks like the Haddon Matrix—developed by William Haddon in the 1960s—which systematically categorized alcohol as a pre-crash host factor increasing injury probability through reduced vehicle control.[20] Presumptive blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limits, initially set at 0.15% in states like New York by 1938 and adopted widely by the 1940s based on Widmark's pharmacokinetic research quantifying impairment thresholds, saw gradual refinement in the 1960s as chemical testing became admissible evidence in 46 states, shifting from behavioral symptoms to measurable per se violations.[21][22] Scandinavian precedents, such as Norway's 0.05% limit in 1936 and Sweden's 0.08% in 1941, indirectly influenced U.S. discourse through international safety literature, though domestic standards remained higher until data-driven advocacy highlighted their leniency relative to dose-response crash risks.[15][23] This era's emphasis on empirical causation over anecdotal enforcement laid groundwork for uniform testing protocols, reducing variability in DUI adjudications.[24]Late 20th to Early 21st Century Expansions

In 1984, the U.S. Congress enacted the National Minimum Drinking Age Act, conditioning federal highway funding on states establishing a minimum purchase and public possession age of 21 for alcohol, with full compliance achieved by 1988. Meta-analyses of studies on raising the minimum legal drinking age (MLDA) indicate an average 13% reduction in alcohol-related traffic fatalities, particularly among drivers under 21.[25] The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimates these laws prevent approximately 900 fatalities annually by limiting youth access and reducing novice driver impairment.[26] From the late 1990s through the early 2000s, all U.S. states adopted a per se 0.08% blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limit for non-commercial drivers, spurred by federal grant incentives under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (1998) and subsequent appropriations. Evaluations of early adopters, such as California (1990) and Utah (pre-2000s), found 16% to 18% relative declines in the proportion of fatal crashes involving alcohol-impaired drivers post-implementation, with overall alcohol-related fatalities dropping 3% to 7% after controlling for trends.[27][28] These standards facilitated objective enforcement via breath tests, reducing reliance on subjective field sobriety observations, though some analyses attribute part of the gains to concurrent administrative license suspension laws rather than the BAC threshold alone.[28] Early 21st-century expansions targeted drug-impaired driving amid rising cannabis use and state legalizations starting in 2012, prompting per se limits for THC and other substances in jurisdictions like Nevada and Colorado. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) analyses linked recreational marijuana legalization to a 6.5% increase in injury crash rates and 2.3% in fatal crash rates across legalized states, with police-reported crashes rising post-retail sales in California, Colorado, and others.[29] Technological integrations included portable oral fluid testing devices for roadside drug detection, validated in studies for identifying recent cannabis and other impairing substances, though challenges persist in correlating metabolite presence with real-time impairment. Federal initiatives, such as the End DWI Act reintroduced in 2024 and 2025, advocate mandatory ignition interlock devices for all DUI offenders to prevent vehicle startup at impairing BAC levels, building on state data showing recidivism reductions of up to 67% with interlocks.[30] State-level updates, like New York's 2024 assignment of 11 DMV points to DWI convictions, aim to accelerate license suspensions.[31] Despite these measures, FBI data recorded nearly 805,000 DUI arrests in 2024, while NHTSA reported over 12,000 alcohol-impaired driving fatalities in 2023, underscoring ongoing enforcement gaps.[32][33]Scientific Foundations of Impairment

Physiological Effects of Alcohol

Alcohol functions as a central nervous system (CNS) depressant by potentiating inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission and antagonizing excitatory N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, thereby reducing overall neural excitability and signal propagation speed. This manifests in cerebellar disruption, impairing balance, posture, and fine motor coordination critical for vehicle control, as evidenced by increased body sway and slowed psychomotor responses in laboratory assessments. Frontal lobe functions, including executive processes like impulse control and risk assessment, are similarly compromised, with neuroimaging and behavioral studies linking acute intoxication to diminished prefrontal cortex activation and heightened error rates in decision-making tasks.[34] Empirical data from simulator and psychomotor testing reveal dose-dependent elevations in reaction time, with blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) of 0.05% yielding approximately 50% longer response latencies in pedestrian detection and braking simulations compared to sober baselines, escalating risks in dynamic driving environments. Metabolism adheres to zero-order kinetics post-absorption, eliminating alcohol at a near-constant rate of 0.015-0.02% BAC per hour regardless of concentration, while peak impairment aligns with maximum BAC, typically 30-90 minutes after ingestion, influenced by gastric emptying rates.[35][36][37] Alcohol promotes diuresis via suppression of antidiuretic hormone, inducing mild dehydration that compounds fatigue through reduced cerebral perfusion and heightened subjective drowsiness, as quantified by doubled minor errors in prolonged simulated drives under hypohydrated conditions mimicking alcohol's secondary effects. Vasodilation further diverts blood flow peripherally, exacerbating central fatigue without compensatory thermoregulation, per controlled dehydration protocols. Gender variances arise from pharmacokinetic differences, with females attaining higher peak BAC for equivalent doses due to diminished gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity—reducing first-pass metabolism by up to 30%—coupled with lower total body water distribution volumes, as modeled in isotopic tracer studies.[38][39][40]Impacts of Drugs and Other Substances

Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component in cannabis, impairs drivers' ability to maintain lane position, track visual stimuli, and make time-sensitive decisions, with acute psychomotor deficits typically lasting 3-4 hours after consumption.[41] Meta-analyses of culpability studies estimate that cannabis-positive drivers experience 1.2 to 1.9 times higher odds of crash involvement compared to drug-free drivers, with unadjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.25 to 1.92.[42][43] These risks are amplified among inexperienced users, who exhibit greater lane weaving and slower reaction times than chronic users who may develop partial tolerance.[44] Post-legalization data from U.S. states indicate lagged increases in traffic fatalities, including a 2.3% rise in fatal crashes and up to 6.5% in injury crashes following recreational access, attributed partly to higher prevalence of THC-positive drivers.[45][46] Opioids, such as heroin and prescription analgesics, cause central nervous system depression leading to sedation, slowed reflexes, and potential respiratory compromise, all of which elevate crash susceptibility by reducing vigilance and coordination.[47] Sedatives including benzodiazepines similarly induce drowsiness and cognitive slowing; their use correlates with doubled crash risk due to impaired divided attention and judgment.[48] Stimulants like cocaine counteract fatigue but heighten impulsivity and risk-taking, resulting in aggressive maneuvers; drivers positive for stimulants or opioids in emergency department samples show 2-3 times overrepresentation in collision-involved cases relative to population prevalence.[49][50] Prescription and over-the-counter medications, encompassing antidepressants, antihistamines, and opioids, contribute to impairment through mechanisms like dizziness, blurred vision, and delayed processing, with benzodiazepines exemplifying sedative effects that persist variably based on dosage and individual metabolism.[8] The Governors Highway Safety Association highlights that hundreds of such substances complicate enforcement, as pharmacological profiles yield inconsistent blood concentration thresholds for impairment unlike alcohol's predictable kinetics.[51] Variable detection windows—ranging from hours for acute sedatives to days for certain metabolites—hinder per se legal standards, necessitating reliance on observed behaviors for assessment.[52] Polydrug combinations, prevalent in up to 20-30% of toxicology-positive crash victims, synergistically amplify impairment via additive or potentiating effects, such as cannabis with opioids enhancing sedation or stimulants masking depressant cues until sudden performance drops.[50] Latent class analyses reveal polydrug users, particularly those mixing depressants and stimulants, face elevated crash odds beyond single-substance risks, driven by unpredictable interactions disrupting executive function and perceptual accuracy.[53] Empirical crash data underscore that multiple drugs correlate with higher culpability rates, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions beyond isolated substance focus.[50]Dose-Response Relationships and Risk Thresholds

Epidemiological research, including the landmark Grand Rapids Study by Borkenstein et al., demonstrates a dose-response relationship where crash involvement risk rises exponentially with blood alcohol concentration (BAC), exhibiting a gradient rather than a binary impairment threshold. Relative risk begins to elevate detectably at BAC levels as low as 0.02%, with probabilities of accident involvement increasing progressively; for instance, BACs exceeding 0.04% are associated with definite risk elevation.[54][55] Contemporary meta-analyses quantify this gradient: compared to zero BAC, relative risks are 1.33 at 0.001–0.019%, 2.68 at 0.02–0.049%, and 6.24 at 0.05–0.079% among all drivers. These data indicate that impairment and crash risk commence near zero BAC, establishing that the safest approach to blood alcohol content when driving is not to consume alcohol at all. At the standard U.S. legal limit of 0.08% BAC, crash risk multiplies approximately 4-fold for general involvement but 10–12-fold for fatal crashes, with even greater escalation at higher concentrations like 0.15%.[56][7][57] Utah's 2018 lowering of the per se BAC limit to 0.05%—effective December 30—correlated with a 19.8% reduction in the state's fatal crash rate from 2016 to 2019, equating to over 1,200 fewer motor vehicle deaths nationally if scaled, per modeling of the policy's deterrence effects on moderate drinkers. This outcome supports targeting sub-0.08% levels, though empirical impairment at 0.05% BAC manifests primarily as mild coordination deficits and judgment lapses, prompting debate over whether such thresholds excessively penalize low-risk social consumption without proportional safety gains.[58][59] Alcohol-impaired driving (BAC ≥0.08%) contributes disproportionately to severe outcomes, accounting for 30% of U.S. traffic fatalities in recent years while comprising far less than 5% of total reported crashes, as minor incidents rarely involve high BACs. This severity skew parallels fatigue, where crash odds at low BACs (e.g., 0.05%) approximate those of 18–24 hours wakefulness, but contrasts with speeding's broader prevalence, implicated in 29% of fatal crashes via higher incident volume across impairment levels.[57][60][61] Alcohol-related fatalities have declined about 50% since the 1980s—from 48% to 30% of total traffic deaths—amid legal reforms, yet absolute numbers and proportional shares have stabilized or slightly rebounded post-2010, indicating deterrence yields plateau beyond which complementary interventions, like addressing polydrug use or behavioral factors, are needed for further causal reductions.[60][62]Legal Frameworks

Core Definitions and Per Se Standards

Driving under the influence (DUI) is legally defined as the operation of a motor vehicle by a person whose mental or physical faculties are impaired to the point of being unable to drive safely due to the consumption of alcohol, drugs, or a combination thereof.[63] This impairment-based definition relies on evidence of observable deficits in coordination, judgment, or reaction time, often established through field sobriety tests or officer testimony, placing a higher evidentiary burden on prosecutors compared to proxy measures.[64] In contrast, per se DUI laws establish illegality based solely on exceeding a specified blood alcohol concentration (BAC) threshold, irrespective of demonstrated impairment. All U.S. states except Utah criminalize driving with a BAC of 0.08 grams per 100 milliliters of blood or higher as a per se offense, a standard incentivized by federal legislation in the Transportation Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2001, which conditioned highway funding on state adoption by fiscal year 2004.[65][66] This proxy approach leverages BAC as a quantifiable correlate to elevated crash risk, derived from epidemiological data showing exponential increases in impairment likelihood above this level, though individual physiological variations—such as tolerance from chronic use—can result in safe driving by some above 0.08% or impairment below it.[63] To facilitate enforcement of per se standards, all U.S. jurisdictions incorporate implied consent doctrines, whereby obtaining a driver's license constitutes agreement to submit to chemical testing (e.g., breath or blood) upon reasonable suspicion of DUI; refusal triggers automatic administrative license suspension, typically for 6 to 12 months, independent of criminal proceedings.[67][68] Certain circumstances elevate standard DUI to aggravated forms, often reclassifying misdemeanors as felonies. These include transporting a minor (generally under 15 years old) in the vehicle during the offense, reflecting heightened endangerment to vulnerable passengers, or prior convictions—such as a third or subsequent DUI within a defined period (e.g., 7-10 years)—indicating recidivism and persistent risk.[69][70]Variations in Impairment vs. Zero-Tolerance Approaches

In the United States, DUI laws employ two primary approaches: impairment-based models, which require prosecutors to demonstrate that a driver's ability to operate a vehicle safely was substantially impaired by alcohol or drugs through observational evidence such as field sobriety tests or erratic driving, and zero-tolerance or per se models, which establish strict chemical thresholds where exceeding the limit constitutes an offense regardless of observed impairment.[64][71] Per se laws facilitate enforcement by relying on objective chemical tests, reducing reliance on subjective judgments, but they risk convicting individuals whose substance levels do not correspond to actual performance deficits, particularly for drugs.[72] Impairment models, conversely, prioritize evidence of causal impact on driving skills but demand more resources for proof, potentially leading to lower conviction rates in ambiguous cases.[73] Zero-tolerance provisions for drivers under 21, mandated nationwide since the 1990s under federal incentives, set BAC limits at 0.02% or lower—such as 0.01% in California—triggering automatic license suspensions even for minimal consumption equivalent to one drink.[74] These stem from empirical data showing younger drivers exhibit heightened sensitivity to alcohol's effects on reaction time and divided attention at low doses, with studies indicating a 21% reduction in underage alcohol-related crashes post-implementation in select areas.[74] Critics argue, however, that such thresholds penalize non-impairing levels, as BACs below 0.05% often produce negligible effects on mature driving tasks in controlled settings, potentially undermining public trust by conflating presence with incapacity.[75][76] For controlled substances, per se laws in 20 states as of 2023 impose fixed thresholds like Colorado's 5 ng/mL of delta-9 THC in whole blood, presuming impairment upon detection to streamline prosecutions amid rising cannabis legalization.[77] Yet, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration analyses reveal THC blood concentrations correlate weakly with crash risk or psychomotor deficits, unlike alcohol's dose-response curve, as THC's fat-soluble nature causes lingering detectability hours after acute effects subside, leading to convictions of non-impaired drivers or missed detections in tolerant users.[78][79] This mismatch highlights enforcement trade-offs: per se simplifies arrests via blood tests but sacrifices precision, with Virginia studies finding no elevated risk for THC-positive drivers after controlling for confounders like alcohol co-use.[78] Hybrid approaches in states like those adopting the Drug Evaluation and Classification Program mitigate these issues by integrating per se thresholds with observational assessments from certified Drug Recognition Experts (DREs), who conduct 12-step evaluations including eye nystagmus checks, vital signs, and psychophysical tests to corroborate chemical evidence with impairment signs.[80] DRE protocols achieve 79-81% accuracy in identifying cannabis influence but yield false positives in 16% of drug-free cases, offering a balanced evidentiary tool where pure per se risks overreach and pure impairment demands excessive subjectivity.[81] Such models enhance prosecutorial success in drug cases, where standalone thresholds falter, though their efficacy depends on officer training and judicial acceptance of DRE testimony as reliable adjunct evidence.[82]Related Offenses and Aggravating Factors

In many jurisdictions, driving under the influence with a minor passenger constitutes child endangerment, triggering mandatory sentence enhancements due to the elevated vulnerability of children in impaired driving scenarios. For instance, 47 U.S. states have enacted specific DUI child endangerment laws (DUI-CELs) that impose additional penalties when underage passengers are present, reflecting empirical evidence that such incidents double the odds of child injury compared to sober-driven crashes involving minors.[83] These enhancements are justified by data showing alcohol-impaired drivers contribute to disproportionate child passenger fatalities; a CDC analysis of 1990–2001 Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) data found that 23% of child passenger deaths (ages 0–14) involved alcohol-impaired drivers, with risks amplified by improper restraint use and crash severity.[84][85] A related offense in California is "wet reckless," a plea bargain reducing a DUI charge to reckless driving involving alcohol (California Vehicle Code § 23103.5) for cases with marginal blood alcohol concentrations (BACs), often below 0.15%. This downgrade aims to curb recidivism through lighter penalties like shorter license suspensions and no mandatory DUI designation on records, with California DMV studies indicating wet reckless pleas correlate with somewhat lower reoffense rates than full DUI convictions, potentially by encouraging compliance without overly punitive barriers.[86] However, critics note it may underdeter high-risk drivers, as recidivism remains elevated relative to non-offenders.[87] Open container laws, prohibiting accessible alcohol in vehicle passenger compartments, function as proxies for intoxication risk and are enforced alongside DUI statutes in 39 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Violations correlate with heightened crash involvement; states lacking these laws exhibit significantly higher percentages of alcohol-positive fatal crashes (up to 15% greater alcohol-involved single-vehicle incidents per National Highway Traffic Safety Administration comparisons), underscoring their role in preempting impairment escalation.[88][89] Aggravating factors in DUI prosecutions often include prior convictions, which signal chronic impairment patterns linked to 2–4 times higher crash recidivism risks, prompting felony escalations after 2–3 offenses in most states. For example, in Illinois, a third DUI offense is classified as a Class 2 felony under 625 ILCS 5/11-501.[90] Elevated BAC levels (e.g., ≥0.15%) similarly aggravate charges, as they causally amplify impairment and collision severity, with data from the National Safety Council showing exponential risk increases beyond 0.08%.[91] These elements, when combined with endangerment, substantiate enhanced sanctions grounded in probabilistic harm data rather than mere moral hazard.[60]Detection and Evidence Gathering

Field Sobriety and Preliminary Assessments

Field sobriety tests, developed and standardized by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in the 1970s and refined through laboratory and field validation studies, serve as preliminary on-scene assessments to evaluate suspected impairment from alcohol or other substances. The Standardized Field Sobriety Test (SFST) battery consists of three psychophysical tests: horizontal gaze nystagmus (HGN), walk-and-turn (WAT), and one-leg stand (OLS). These tests aim to detect divided attention deficits and balance issues indicative of impairment, with validation studies conducted between 1977 and 1998 demonstrating their utility in predicting blood alcohol concentration (BAC) above legal thresholds.[92][93] The HGN test observes involuntary eye jerking, which becomes more pronounced at BAC levels of 0.04% or higher, particularly at maximum deviation and onset before 45 degrees. NHTSA's San Diego field validation study of 297 subjects found HGN alone to be 77% accurate in discriminating BAC at or above 0.10%, making it the most reliable single indicator due to its physiological basis in central nervous system depression by alcohol. When combined with WAT and OLS, the full SFST battery achieved 91% accuracy for BAC ≥0.08% in the same study, with WAT at 68% and OLS at 65% individually. These figures derive from controlled comparisons of officer observations against subsequent chemical tests, though accuracy drops for lower BAC thresholds like 0.05%.[94][93][95] Despite their empirical validation, SFSTs are susceptible to false positives influenced by non-impairment factors, particularly medical conditions affecting balance, coordination, or eye movement. Conditions such as inner ear disorders (e.g., vertigo), neurological issues (e.g., multiple sclerosis), leg injuries, or even fatigue and age-related declines can mimic impairment cues, reducing specificity in field applications. Validation studies acknowledge these confounders but prioritize overall discriminatory power over perfect sensitivity, with real-world error rates potentially higher due to suboptimal testing conditions like poor lighting or uneven surfaces.[92][96] For suspected drug impairment, where alcohol cues are absent, officers may employ the Drug Recognition Expert (DRE) protocol, a 12-step evaluation standardized by NHTSA and the International Association of Chiefs of Police since 1984. This systematic process includes checks for vital signs, eye examinations (including HGN and lack of convergence), psychophysical tests similar to SFST, and darkroom pupil analysis to identify drug categories like CNS depressants or stimulants. Recent field studies report DRE accuracy rates of 88% overall, rising to 91.8% for single-drug cases, based on comparisons with toxicological confirmation, though multi-drug scenarios lower reliability to around 80%. The protocol's validity stems from physiological indicators unique to drug classes, validated through controlled evaluations rather than alcohol-focused SFST data.[80][97][98]Chemical Testing Methods and Protocols

Breath testing devices, commonly used for preliminary and evidentiary alcohol detection, operate primarily through infrared spectroscopy, which measures the absorption of infrared light by ethanol molecules in exhaled breath at wavelengths around 3.4 micrometers.[99] These instruments convert breath alcohol concentration to an estimated blood alcohol concentration (BAC) using a fixed partition ratio of 2100:1, assuming 2100 parts of alveolar air correspond to one part of alcohol in blood.[100] Evidential-grade breathalyzers achieve accuracy within ±0.01% to ±0.02% BAC under controlled conditions, though factors like device calibration, subject temperature, and residual mouth alcohol can introduce variability.[101] Blood testing remains the gold standard for BAC measurement, directly quantifying alcohol via gas chromatography or enzymatic assays on venous samples, offering precision unmatched by indirect methods but requiring medical personnel for invasive venipuncture.[102] Protocols mandate collection within two hours of driving in many jurisdictions to align with legal per se limits, yet the breath-to-blood conversion's 2100:1 ratio assumption proves flawed for approximately 20% of individuals, whose actual ratios fall below this average due to physiological differences in lung function, hematocrit, or absorption phase, potentially inflating breath-derived BAC estimates.[102] [103] For drug-impaired driving, particularly cannabis, chemical protocols increasingly employ oral fluid swabbing to detect delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), targeting recent use via immunoassay followed by confirmatory mass spectrometry, with cutoff levels like 5 ng/mL for screening.[104] Oral fluid correlates better with recent smoking than blood for acute impairment, but THC persistence in chronic users—detectable up to 24 hours or more post-use despite impairment waning after 2-6 hours—risks false positives unrelated to current psychomotor deficits.[105] Studies report false positive rates of 5-17% in simulated driving scenarios when using 10 ng/mL confirmatory thresholds, highlighting mismatches between detection windows and operational impairment.[104] [106] Under implied consent statutes in all U.S. states, drivers are deemed to have consented to chemical testing upon licensure; refusal triggers automatic administrative license suspension—typically 6-12 months for first offenses—independent of criminal DUI charges.[107] Courts have upheld these penalties as civil sanctions rather than unconstitutional self-incrimination, despite Fourth Amendment challenges arguing they coerce warrantless searches, with the U.S. Supreme Court affirming breath tests as search-incident exceptions but requiring warrants for blood absent exigent circumstances.[108] [109] Protocols often include observation periods (15-20 minutes pre-breath test) to prevent adulteration and duplicate samples for defendant confirmation testing.[110]Technological Advances and Reliability Issues

Ignition interlock devices (IIDs), which prevent vehicles from starting if breath alcohol concentration exceeds a preset limit, have shown measurable reductions in DUI recidivism during periods of use. A review of multiple studies found that IID participants were 15% to 69% less likely to face re-arrest for driving while intoxicated compared to non-users.[111] The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reports that offenders with IIDs installed experienced arrest recidivism rates 75% lower than those without, based on evaluations across various programs.[112] However, recidivism often rebounds after device removal unless paired with extended monitoring, as evidenced by longitudinal data from state implementations.[113] By October 2025, 34 U.S. states mandate IIDs for first-time DUI offenders, with some extending requirements to all convicted drivers regardless of prior offenses.[114] Federal initiatives, including the End DWI Act of 2025 (H.R. 2788), seek to standardize IID requirements nationwide for repeat offenders, while the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act advances mandates for passive alcohol-detection technology in new vehicles starting as early as 2026.[30][115] These systems aim for seamless integration without active breath tests, though full deployment faces technical and cost hurdles. Emerging wearable devices, such as transdermal alcohol monitors like SCRAM, enable continuous remote monitoring by detecting ethanol in sweat, with trials showing low false positive rates of approximately 0.07% per 12-hour period under controlled conditions.[116] Roadside passive scanners and smartphone-linked apps for preliminary alcohol detection remain speculative for widespread enforcement, with preliminary evaluations indicating false positive rates of 10% or higher due to interferents like mouthwash residues or environmental volatiles.[117] Reliability challenges persist, as non-ethanol substances and calibration errors can trigger alerts, potentially leading to unwarranted interventions.[118] Data logging in IIDs and wearables, which records breath samples, start attempts, and GPS coordinates downloaded every 30-67 days, has sparked privacy concerns over potential surveillance.[119] Critics, including the American Civil Liberties Union, argue that aggregated logs could enable tracking of personal movements beyond impairment verification, especially with proposed vehicle-wide mandates.[120] State regulations limit data access, but breaches or expanded use remain risks in post-installation analysis.[121]Empirical Data and Risk Analysis

Prevalence and Self-Reported Behaviors

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), self-reported past-year driving under the influence of alcohol declined to approximately 8.5% among adults in 2016–2017, with rates of 11.1% for men and 6.1% for women, reflecting a reduction from earlier periods but likely underestimating true incidence due to social desirability bias and underreporting in surveys.[122] More recent estimates indicate that about 1.2% of adults self-reported driving after excessive alcohol consumption in the past 30 days in 2020, equating to roughly 127 million episodes annually, though annual figures remain lower than observed enforcement data suggests.[123] Observed prevalence through arrests provides a counterpoint, with U.S. law enforcement making approximately 805,000 DUI arrests in 2024, per estimates derived from FBI Uniform Crime Reporting data, indicating that self-reports capture only a fraction of incidents due to non-detection and deterrence effects.[124] Demographic patterns show males aged 21–34 as the highest-risk group, comprising the largest share of both self-reported and arrested DUI offenders, with alcohol involved in about 80–86% of cases based on primary substance reports in treatment and enforcement contexts.[3][125] For drug-involved DUI, self-reported annual driving under the influence of cannabis stands at around 4.5% nationally, with state variations from 3.0% to 8.4%, and post-legalization trends in states like Colorado showing increased self-reported marijuana use overall, though direct DUI self-reports have not uniformly surged and arrests have remained stable.[126][127] This distinction highlights underreporting for both alcohol and cannabis, as surveys rely on voluntary disclosure while arrests reflect targeted policing.[123]Crash and Fatality Statistics

In 2023, alcohol-impaired driving crashes in the United States resulted in 12,429 fatalities, representing approximately 30% of the total 40,901 motor vehicle traffic deaths that year.[33][128] These figures are derived from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS), which attributes alcohol impairment to crashes involving at least one driver with a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.08 grams per deciliter or higher.[33] The alcohol-impaired fatality rate per 100 million vehicle miles traveled (VMT) stood at 0.42 in 2022, a 2.3% decline from 0.43 in 2021, reflecting improved per-mile safety amid rising total VMT.[5] From 2022 to 2023, absolute alcohol-impaired fatalities decreased by 7.6%, though overall traffic fatalities fell by 4.3%, indicating a relative improvement in the alcohol-attributable fraction.[128] Despite these trends, absolute numbers remain elevated compared to pre-pandemic levels, with over 10,000 annual deaths consistently reported since 2014.[3] Drug involvement complicates attribution, as toxicology testing detects presence but not necessarily causation or impairment levels at crash time. In a NHTSA study of seriously or fatally injured road users, 55.8% tested positive for at least one drug (including alcohol), with cannabinoids detected in 25.1% of cases and alcohol in 23.1%; however, only a subset of crashes can reliably link drugs to driver error via FARS coding.[129] Approximately 56% of drivers in serious injury and fatal crashes tested positive for drugs in sampled trauma centers from late 2020, often involving multiple substances in 18% of cases, though polydrug effects and passive exposure limit causal inferences.[6][130] FARS data underreports drug-attributable fatalities due to inconsistent testing (around 63% of fatally injured drivers tested in recent years) and challenges in distinguishing therapeutic from impairing levels.[131]Comparative Risks with Other Driving Hazards

Driving under the influence of alcohol at a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.08% elevates the odds ratio for fatal crash involvement to approximately 4 to 7 times that of sober driving, based on epidemiological analyses of crash data.[56] This relative risk arises from impaired reaction times, judgment, and vehicle control, though a substantial portion—up to 50% at 0.08% BAC—stems from associated behaviors like excessive speeding rather than alcohol's direct physiological effects alone.[132] In contrast, distracted driving via cell phone conversation produces impairments comparable to a BAC of 0.05%, with odds ratios for crash risk around 2 to 4 times higher, while texting elevates it further to 6 to 23 times depending on the metric and study controls.[133][134] Speeding contributes to a greater absolute number of fatalities than alcohol impairment across U.S. roadways, with 12,151 passenger vehicle occupant deaths involving a speeding driver in 2022 compared to 10,854 fatalities in alcohol-impaired driving crashes (BAC ≥0.08%).[135] This disparity reflects speeding's higher prevalence as a behavioral factor, implicated in 29% of all fatal crashes versus alcohol impairment in about 25%.[3] Case-control studies confirm that while alcohol independently heightens crash odds (e.g., odds ratio of 11.2 for BAC ≥0.08% in controlled samples), its effects often compound with speeding, which independently doubles or triples crash risk in multivariate models.[7] Among high-risk demographics like young male drivers aged 15-24, excess speed accounts for a larger share of crash involvement than impairment alone, with 35% of male drivers aged 15-20 in fatal crashes exceeding speed limits versus lower proportions attributable solely to alcohol.[136][137] Peer-reviewed analyses indicate that for this group, the per capita risk from all forms of impaired driving remains lower than from speeding or aggressive maneuvers, underscoring how baseline risk-taking behaviors amplify hazards beyond substance effects.[138] Empirical deterrence models emphasize that perceived risk of detection for any hazard, including speeding, correlates more strongly with reduced incidence than absolute risk magnitude, as drivers weigh enforcement certainty over inherent crash probabilities.[139]Enforcement and Judicial Processes

Policing Tactics and Arrest Procedures

Sobriety checkpoints and saturation patrols constitute primary operational tactics for detecting impaired drivers. Checkpoints systematically stop vehicles at fixed locations, allowing officers to observe signs of intoxication such as slurred speech or alcohol odor, with research indicating they reduce alcohol-related crashes by 17% and all crashes by 10-15% when publicized.[140] These operations, supported by organizations like Mothers Against Drunk Driving, prove effective even with minimal staffing of three to five officers, though they demand substantial resources for setup and public notification to maximize deterrence.[141][142] Saturation patrols deploy heightened officer presence in targeted zones, often during peak-risk periods like holidays, to identify erratic driving behaviors including swerving or speeding. A national survey found 63% of local agencies and 96% of state patrols utilize these patrols, which serve as general deterrents but yield inconsistent arrest increases compared to checkpoints, particularly in suburban settings where geographic spread limits efficiency.[143][144] Data-driven approaches, emphasizing high-incident areas and times, have gained traction post-2024, with initiatives like Saturation Saturday events in multiple states incorporating increased patrols alongside checkpoints.[145][146] Arrest procedures hinge on establishing reasonable suspicion for initial stops via observable violations—such as weaving across lanes or strong alcohol odor—escalating to probable cause through field assessments. Officers may request consent for preliminary breath tests or vehicle searches, but positive yields remain low, typically under 2% in non-targeted encounters, underscoring the value of behavioral cues over random screening.[147][148] Once probable cause is met, handcuffing and transport to a station for evidentiary testing follow standardized protocols to preserve chain of custody.[149] Recent enforcement shifts prioritize high-risk zones identified via crash data, enhancing patrol allocation without broadening scope to low-yield areas.[150][151]Prosecution Challenges and Defenses

Prosecutors in driving under the influence (DUI) cases frequently encounter evidentiary challenges related to the integrity of blood test results, particularly breaches in the chain of custody from collection to analysis. Any undocumented gaps, improper storage, or mishandling during transport can lead to suppression of the evidence, as courts require strict documentation to ensure the sample's authenticity. Such chain-of-custody errors have been documented to nullify blood alcohol concentration (BAC) evidence in approximately 12% of tested cases.[152] These procedural hurdles contribute to dismissals or reductions, with defense motions often succeeding when prosecution logs reveal inconsistencies, underscoring the need for meticulous forensic protocols.[153] Affirmative defenses commonly invoked include the rising BAC argument, which contends that the driver's alcohol level was below the legal threshold (typically 0.08%) while operating the vehicle but increased subsequently due to delayed absorption from recent consumption. This defense relies on pharmacokinetic evidence, such as the timing of intake relative to testing, and has been upheld in jurisdictions where retroactive extrapolation models fail to account for individual metabolic variations.[154] Similarly, the fermentation defense challenges elevated BAC readings by alleging post-collection microbial activity in the blood sample, which produces additional alcohol and inflates results; this requires expert testimony on storage conditions like temperature lapses or contamination.[155] Courts have recognized this in cases of documented lab mishandling, though success depends on rebutting prosecution safeguards like preservatives.[155] Medical necessity serves as a narrow affirmative defense, applicable only in exceptional scenarios where impaired driving was the least harmful option to prevent imminent peril, such as transporting someone in acute medical distress without alternatives. This defense demands proof of no reasonable substitute actions and that the harm avoided outweighed the DUI risk, with limited judicial acceptance due to strict elements like unforeseeability.[156][157] Over 90% of DUI prosecutions resolve via plea bargains before trial, enabling prosecutors to manage caseloads by negotiating reduced charges—such as reckless driving—in exchange for guilty pleas, thereby sidestepping full evidentiary contests.[158][159] This high resolution rate reflects mutual incentives: defenses leverage evidentiary weaknesses for concessions, while prosecutors prioritize convictions over protracted litigation.[160]Sentencing Guidelines and Recidivism Factors

Sentencing guidelines for first-time driving under the influence (DUI) offenses in the United States typically include fines ranging from $250 to $2,000 and potential incarceration of up to six months, though actual jail time is often avoided through probation, community service, or alcohol education programs, with mandatory minimums like 24-72 hours in some states.[161][162] Harsher penalties apply to repeat offenders, escalating to longer jail terms (e.g., 30 days minimum in certain jurisdictions) and license revocation, guided by state-specific statutes that factor in blood alcohol concentration (BAC) levels, prior convictions, and injury involvement to prioritize deterrence and public safety.[163][164] Recidivism rates among DUI offenders vary by study and jurisdiction but commonly range from 10% to 47% within three years of the initial conviction, with National Institutes of Health-funded research indicating an annual rate of approximately 2.4% among first offenders, compounding to higher cumulative risks over time.[87][165][166] Causal predictors of reoffense emphasize psychological and attitudinal elements over demographics; for instance, low perceived certainty of punishment or personal invulnerability to consequences doubles the odds of recidivism, as low deterrence belief fosters continued risk-taking behavior rooted in cognitive biases rather than socioeconomic status.[167][168] Judicial guidelines increasingly incorporate these factors into sentencing, such as mandating assessments for antisocial attitudes or alcohol preoccupation to tailor interventions, with evidence showing that untreated psychological drivers like attentional bias toward alcohol heighten repeat offense likelihood independently of BAC at arrest.[169][170] Alternative measures, including structured education programs, demonstrate modest efficacy in reducing recidivism by 7-9% compared to fines alone, particularly for non-alcoholic-dependent offenders, by addressing attitudinal deficits through targeted cognitive-behavioral content rather than punitive isolation.[171][172] Such programs, when completed as part of sentencing, lower reoffense odds by enhancing risk awareness, though effects diminish without follow-up monitoring for high-risk profiles.[173]Penalties and Societal Costs

Criminal and Administrative Sanctions

In the United States, first-offense driving under the influence (DUI) convictions generally result in criminal fines ranging from $500 to $2,000, varying by state and factors such as blood alcohol concentration (BAC).[174] [175] Many jurisdictions classify a first DUI as a misdemeanor, imposing minimum jail terms of 24 to 48 hours, with maximum sentences up to one year; for example, Georgia mandates at least 24 hours unless probated.[161] [176] In Georgia, however, DUI charges can often be reduced to reckless driving via plea bargain; reckless driving is a misdemeanor under O.C.G.A. § 40-6-390, punishable by a fine up to $1,000 and/or up to 12 months jail, though plea deals typically result in $300–$1,000 fines, community service, and minimal or no jail for first-time or negotiated cases.[177] [178] Benefits include avoiding a DUI conviction on the criminal record (which carries greater stigma and impacts employment and insurance more severely), no mandatory one-year driver's license suspension, no required DUI alcohol/drug risk reduction program, and addition of 4 points to the license (compared to more points and administrative actions for DUI). Aggravated cases, such as those involving high BAC levels or injury, can elevate the offense to a felony, leading to prison terms of one to several years.[162] Administrative sanctions focus on driver licensing, typically suspending privileges for 6 to 12 months following an administrative per se action based on failed sobriety tests.[179] [180] Some states permit restricted or hardship licenses for essential travel, such as work or medical needs, after an ignition interlock device installation period.[174] In 2025, New York enhanced its administrative framework by incorporating points for DWI convictions into the DMV system—previously excluded—and extending the look-back period for suspensions to 24 months at 11 points, aiming to deter persistent impaired driving through permanent revocation after four alcohol- or drug-related convictions.[181] [182] Compliance with these sanctions remains inconsistent; for instance, among repeat offenders eligible for ignition interlocks as part of administrative restrictions, only about 25% fully adhere to installation and usage requirements.[183] License suspension evasion contributes to ongoing enforcement challenges, though enhanced sanctions for high-BAC offenders (e.g., 0.20 g/dL or above) correlate with reduced one-year recidivism rates compared to lower-BAC cases.[184]Economic and Personal Consequences

A conviction for driving under the influence often triggers sharp rises in automobile insurance premiums, with averages increasing 70% to 150% nationwide, though some insurers impose hikes exceeding 200% depending on state laws and driver history.[185] [186] These surcharges, frequently requiring SR-22 filings, can endure 3 to 10 years, cumulatively adding $5,000 to $15,000 or more to premiums over that period based on baseline rates around $2,000 annually.[187] Direct outlays for fines, court fees, and attorney costs in a first-offense case typically total $1,000 to $5,000, pushing overall immediate financial hits to $10,000–$25,000 when combined with towing, ignition interlock, and related expenses.[188] Employment disruptions compound these burdens, as DUI records prompt terminations or hiring rejections in 10–30% of cases involving licensed professionals or transportation roles, per analyses of arrest outcomes and pretrial detention effects.[189] [190] Lost wages from suspensions or unemployment can exceed $10,000 in the first year for median earners, while long-term wage suppression from criminal records erodes lifetime earnings by 10–20% through reduced promotions and job mobility, particularly for those without college degrees.[191] Beyond finances, personal ramifications include strained family relations, especially when children are passengers, elevating risks of child endangerment charges that trigger custody evaluations or removals in severe instances. Roughly one in five child passenger deaths annually stems from alcohol-impaired drivers, underscoring heightened vulnerability and potential for intergenerational trauma.[192] At a societal level, alcohol-impaired crashes exact over $123 billion yearly in the U.S., factoring medical treatments, productivity losses, and property damage from 2020 data, though total crash costs reached $340 billion in 2019 with alcohol contributing disproportionately to fatalities and injuries.[123] [193] These aggregates reflect causal chains from impaired operation to emergency responses and rehabilitation, dwarfing individual penalties in scale.Rehabilitation vs. Punitive Measures

Specialized DUI courts, which integrate therapeutic treatment, frequent judicial monitoring, and sanctions for non-compliance, have demonstrated superior outcomes in reducing recidivism compared to traditional punitive processing. A meta-analysis of 28 evaluations found that participation in DWI courts lowered recidivism rates by approximately 50% relative to conventional court handling, attributing efficacy to structured accountability and substance abuse interventions rather than incarceration alone.[194] Ignition interlock devices, requiring a breath test to start a vehicle and functioning as a rehabilitative deterrent, further outperform isolated jail terms; meta-analyses indicate reductions in repeat DUI offenses by 67% during installation periods, with sustained effects when combined with treatment mandates, as they directly prevent impaired operation without the criminogenic risks of imprisonment.[111] Mandatory alcohol education programs yield mixed results, often achieving only modest recidivism decreases of 7-9% in meta-analyses of remedial interventions, with greater success when emphasizing personal accountability over rote instruction; standalone sessions without follow-up monitoring frequently fail to alter entrenched behaviors.[172] Purely punitive measures like short-term jail, while symbolically deterrent, overlook underlying alcohol dependence prevalent among offenders—lifetime rates estimated at 61% for female and 70% for male DWI arrestees in national surveys—potentially exacerbating recidivism by neglecting causal factors such as addiction-driven impulsivity.[195]| Approach | Recidivism Reduction | Key Evidence Source |

|---|---|---|

| DUI Courts | ~50% vs. traditional courts | NHTSA meta-analysis of 28 studies[194] |

| Ignition Interlocks | 67% during use | MADD-cited meta-analysis[196] |

| Mandatory Education | 7-9% | Meta-analysis of 215 evaluations[172] |