Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ordinary differential equation

View on Wikipedia

| Differential equations |

|---|

| Scope |

| Classification |

| Solution |

| People |

In mathematics, an ordinary differential equation (ODE) is a differential equation (DE) dependent on only a single independent variable. As with any other DE, its unknown(s) consists of one (or more) function(s) and involves the derivatives of those functions.[1] The term "ordinary" is used in contrast with partial differential equations (PDEs) which may be with respect to more than one independent variable,[2] and, less commonly, in contrast with stochastic differential equations (SDEs) where the progression is random.[3]

Differential equations

[edit]A linear differential equation is a differential equation that is defined by a linear polynomial in the unknown function and its derivatives, that is an equation of the form

where and are arbitrary differentiable functions that do not need to be linear, and are the successive derivatives of the unknown function of the variable .[4]

Among ordinary differential equations, linear differential equations play a prominent role for several reasons. Most elementary and special functions that are encountered in physics and applied mathematics are solutions of linear differential equations (see Holonomic function). When physical phenomena are modeled with non-linear equations, they are generally approximated by linear differential equations for an easier solution. The few non-linear ODEs that can be solved explicitly are generally solved by transforming the equation into an equivalent linear ODE (see, for example Riccati equation).[5]

Some ODEs can be solved explicitly in terms of known functions and integrals. When that is not possible, the equation for computing the Taylor series of the solutions may be useful. For applied problems, numerical methods for ordinary differential equations can supply an approximation of the solution[6].

Background

[edit]Ordinary differential equations (ODEs) arise in many contexts of mathematics and social and natural sciences. Mathematical descriptions of change use differentials and derivatives. Various differentials, derivatives, and functions become related via equations, such that a differential equation is a result that describes dynamically changing phenomena, evolution, and variation. Often, quantities are defined as the rate of change of other quantities (for example, derivatives of displacement with respect to time), or gradients of quantities, which is how they enter differential equations.[7]

Specific mathematical fields include geometry and analytical mechanics. Scientific fields include much of physics and astronomy (celestial mechanics), meteorology (weather modeling), chemistry (reaction rates),[8] biology (infectious diseases, genetic variation), ecology and population modeling (population competition), economics (stock trends, interest rates and the market equilibrium price changes).

Many mathematicians have studied differential equations and contributed to the field, including Newton, Leibniz, the Bernoulli family, Riccati, Clairaut, d'Alembert, and Euler.

A simple example is Newton's second law of motion—the relationship between the displacement and the time of an object under the force , is given by the differential equation

which constrains the motion of a particle of constant mass . In general, is a function of the position of the particle at time . The unknown function appears on both sides of the differential equation, and is indicated in the notation .[9][10][11][12]

Definitions

[edit]In what follows, is a dependent variable representing an unknown function of the independent variable . The notation for differentiation varies depending upon the author and upon which notation is most useful for the task at hand. In this context, the Leibniz's notation is more useful for differentiation and integration, whereas Lagrange's notation is more useful for representing higher-order derivatives compactly, and Newton's notation is often used in physics for representing derivatives of low order with respect to time.

General definition

[edit]Given , a function of , , and derivatives of . Then an equation of the form

is called an explicit ordinary differential equation of order .[13][14]

More generally, an implicit ordinary differential equation of order takes the form:[15]

There are further classifications:

- Autonomous

- A differential equation is autonomous if it does not depend on the variable x.

- Linear

-

A differential equation is linear if can be written as a linear combination of the derivatives of ; that is, it can be rewritten as

- Homogeneous

- A linear differential equation is homogeneous if . In this case, there is always the "trivial solution" .

- Nonhomogeneous (or inhomogeneous)

- A linear differential equation is nonhomogeneous if .

- Non-linear

- A differential equation that is not linear.

System of ODEs

[edit]A number of coupled differential equations form a system of equations. If is a vector whose elements are functions; , and is a vector-valued function of and its derivatives, then

is an explicit system of ordinary differential equations of order and dimension . In column vector form:

These are not necessarily linear. The implicit analogue is:

where is the zero vector. In matrix form

For a system of the form , some sources also require that the Jacobian matrix be non-singular in order to call this an implicit ODE [system]; an implicit ODE system satisfying this Jacobian non-singularity condition can be transformed into an explicit ODE system. In the same sources, implicit ODE systems with a singular Jacobian are termed differential algebraic equations (DAEs). This distinction is not merely one of terminology; DAEs have fundamentally different characteristics and are generally more involved to solve than (nonsingular) ODE systems.[19][20][21] Presumably for additional derivatives, the Hessian matrix and so forth are also assumed non-singular according to this scheme,[citation needed] although note that any ODE of order greater than one can be (and usually is) rewritten as system of ODEs of first order,[22] which makes the Jacobian singularity criterion sufficient for this taxonomy to be comprehensive at all orders.

The behavior of a system of ODEs can be visualized through the use of a phase portrait.

Solutions

[edit]Given a differential equation

a function , where is an interval, is called a solution or integral curve for , if is -times differentiable on , and

Given two solutions and , is called an extension of if and

A solution that has no extension is called a maximal solution. A solution defined on all of is called a global solution.

A general solution of an th-order equation is a solution containing arbitrary independent constants of integration. A particular solution is derived from the general solution by setting the constants to particular values, often chosen to fulfill set 'initial conditions or boundary conditions'.[23] A singular solution is a solution that cannot be obtained by assigning definite values to the arbitrary constants in the general solution.[24]

In the context of linear ODE, the terminology particular solution can also refer to any solution of the ODE (not necessarily satisfying the initial conditions), which is then added to the homogeneous solution (a general solution of the homogeneous ODE), which then forms a general solution of the original ODE. This is the terminology used in the guessing method section in this article, and is frequently used when discussing the method of undetermined coefficients and variation of parameters.

Solutions of finite duration

[edit]For non-linear autonomous ODEs it is possible under some conditions to develop solutions of finite duration,[25] meaning here that from its own dynamics, the system will reach the value zero at an ending time and stays there in zero forever after. These finite-duration solutions can't be analytical functions on the whole real line, and because they will be non-Lipschitz functions at their ending time, they are not included in the uniqueness theorem of solutions of Lipschitz differential equations.

As example, the equation:

Admits the finite duration solution:

Theories

[edit]Singular solutions

[edit]The theory of singular solutions of ordinary and partial differential equations was a subject of research from the time of Leibniz, but only since the middle of the nineteenth century has it received special attention. A valuable but little-known work on the subject is that of Houtain (1854). Darboux (from 1873) was a leader in the theory, and in the geometric interpretation of these solutions he opened a field worked by various writers, notably Casorati and Cayley. To the latter is due (1872) the theory of singular solutions of differential equations of the first order as accepted circa 1900.

Reduction to quadratures

[edit]The primitive attempt in dealing with differential equations had in view a reduction to quadratures, that is, expressing the solutions in terms of known function and their integrals. This is possible for linear equations with constant coefficients, it appeared in the 19th century that this is generally impossible in other cases. Hence, analysts began the study (for their own) of functions that are solutions of differential equations, thus opening a new and fertile field. Cauchy was the first to appreciate the importance of this view. Thereafter, the real question was no longer whether a solution is possible by quadratures, but whether a given differential equation suffices for the definition of a function, and, if so, what are the characteristic properties of such functions.

Fuchsian theory

[edit]Two memoirs by Fuchs[26] inspired a novel approach, subsequently elaborated by Thomé and Frobenius. Collet was a prominent contributor beginning in 1869. His method for integrating a non-linear system was communicated to Bertrand in 1868. Clebsch (1873) attacked the theory along lines parallel to those in his theory of Abelian integrals. As the latter can be classified according to the properties of the fundamental curve that remains unchanged under a rational transformation, Clebsch proposed to classify the transcendent functions defined by differential equations according to the invariant properties of the corresponding surfaces under rational one-to-one transformations.

Lie's theory

[edit]From 1870, Sophus Lie's work put the theory of differential equations on a better foundation. He showed that the integration theories of the older mathematicians can, using Lie groups, be referred to a common source, and that ordinary differential equations that admit the same infinitesimal transformations present comparable integration difficulties. He also emphasized the subject of transformations of contact.

Lie's group theory of differential equations has been certified, namely: (1) that it unifies the many ad hoc methods known for solving differential equations, and (2) that it provides powerful new ways to find solutions. The theory has applications to both ordinary and partial differential equations.[27]

A general solution approach uses the symmetry property of differential equations, the continuous infinitesimal transformations of solutions to solutions (Lie theory). Continuous group theory, Lie algebras, and differential geometry are used to understand the structure of linear and non-linear (partial) differential equations for generating integrable equations, to find its Lax pairs, recursion operators, Bäcklund transform, and finally finding exact analytic solutions to DE.

Symmetry methods have been applied to differential equations that arise in mathematics, physics, engineering, and other disciplines.

Sturm–Liouville theory

[edit]Sturm–Liouville theory is a theory of a special type of second-order linear ordinary differential equation. Their solutions are based on eigenvalues and corresponding eigenfunctions of linear operators defined via second-order homogeneous linear equations. The problems are identified as Sturm–Liouville problems (SLP) and are named after J. C. F. Sturm and J. Liouville, who studied them in the mid-1800s. SLPs have an infinite number of eigenvalues, and the corresponding eigenfunctions form a complete, orthogonal set, which makes orthogonal expansions possible. This is a key idea in applied mathematics, physics, and engineering.[28] SLPs are also useful in the analysis of certain partial differential equations.

Existence and uniqueness of solutions

[edit]There are several theorems that establish existence and uniqueness of solutions to initial value problems involving ODEs both locally and globally. The two main theorems are

Theorem Assumption Conclusion Peano existence theorem continuous local existence only Picard–Lindelöf theorem Lipschitz continuous local existence and uniqueness

In their basic form both of these theorems only guarantee local results, though the latter can be extended to give a global result, for example, if the conditions of Grönwall's inequality are met.

Also, uniqueness theorems like the Lipschitz one above do not apply to DAE systems, which may have multiple solutions stemming from their (non-linear) algebraic part alone.[29]

Local existence and uniqueness theorem simplified

[edit]The theorem can be stated simply as follows.[30] For the equation and initial value problem: if and are continuous in a closed rectangle in the plane, where and are real (symbolically: ) and denotes the Cartesian product, square brackets denote closed intervals, then there is an interval for some where the solution to the above equation and initial value problem can be found. That is, there is a solution and it is unique. Since there is no restriction on to be linear, this applies to non-linear equations that take the form , and it can also be applied to systems of equations.

Global uniqueness and maximum domain of solution

[edit]When the hypotheses of the Picard–Lindelöf theorem are satisfied, then local existence and uniqueness can be extended to a global result. More precisely:[31]

For each initial condition there exists a unique maximum (possibly infinite) open interval

such that any solution that satisfies this initial condition is a restriction of the solution that satisfies this initial condition with domain .

In the case that , there are exactly two possibilities

- explosion in finite time:

- leaves domain of definition:

where is the open set in which is defined, and is its boundary.

Note that the maximum domain of the solution

- is always an interval (to have uniqueness)

- may be smaller than

- may depend on the specific choice of .

- Example.

This means that , which is and therefore locally Lipschitz continuous, satisfying the Picard–Lindelöf theorem.

Even in such a simple setting, the maximum domain of solution cannot be all since the solution is

which has maximum domain:

This shows clearly that the maximum interval may depend on the initial conditions. The domain of could be taken as being but this would lead to a domain that is not an interval, so that the side opposite to the initial condition would be disconnected from the initial condition, and therefore not uniquely determined by it.

The maximum domain is not because

which is one of the two possible cases according to the above theorem.

Reduction of order

[edit]Differential equations are usually easier to solve if the order of the equation can be reduced.

Reduction to a first-order system

[edit]Any explicit differential equation of order ,

can be written as a system of first-order differential equations by defining a new family of unknown functions

for . The -dimensional system of first-order coupled differential equations is then

more compactly in vector notation:

where

Summary of exact solutions

[edit]Some differential equations have solutions that can be written in an exact and closed form. Several important classes are given here.

In the table below, , , , , and , are any integrable functions of , ; and are real given constants; are arbitrary constants (complex in general). The differential equations are in their equivalent and alternative forms that lead to the solution through integration.

In the integral solutions, and are dummy variables of integration (the continuum analogues of indices in summation), and the notation just means to integrate with respect to , then after the integration substitute , without adding constants (explicitly stated).

Separable equations

[edit]| Differential equation | Solution method | General solution |

|---|---|---|

| First-order, separable in and (general case, see below for special cases)[32]

|

Separation of variables (divide by ). | |

| First-order, separable in [30]

|

Direct integration. | |

| First-order, autonomous, separable in [30]

|

Separation of variables (divide by ). | |

| First-order, separable in and [30]

|

Integrate throughout. |

General first-order equations

[edit]| Differential equation | Solution method | General solution |

|---|---|---|

| First-order, homogeneous[30]

|

Set y = ux, then solve by separation of variables in u and x. | |

| First-order, separable[32]

|

Separation of variables (divide by ). |

If , the solution is . |

| Exact differential, first-order[30]

where |

Integrate throughout. |

where and |

| Inexact differential, first-order[30]

where |

Integration factor satisfying

|

If can be found in a suitable way, then

where and |

General second-order equations

[edit]| Differential equation | Solution method | General solution |

|---|---|---|

| Second-order, autonomous[33]

|

Multiply both sides of equation by , substitute , then integrate twice. |

Linear to the nth order equations

[edit]| Differential equation | Solution method | General solution |

|---|---|---|

| First-order, linear, inhomogeneous, function coefficients[30]

|

Integrating factor: | |

| Second-order, linear, inhomogeneous, function coefficients

|

Integrating factor: | |

| Second-order, linear, inhomogeneous, constant coefficients[34]

|

Complementary function : assume , substitute and solve polynomial in , to find the linearly independent functions .

Particular integral : in general the method of variation of parameters, though for very simple inspection may work.[30] |

If , then

If , then

If , then

|

| th-order, linear, inhomogeneous, constant coefficients[34]

|

Complementary function : assume , substitute and solve polynomial in , to find the linearly independent functions .

Particular integral : in general the method of variation of parameters, though for very simple inspection may work.[30] |

Since are the solutions of the polynomial of degree : , then: for all different, for each root repeated times, for some complex, then setting , and using Euler's formula, allows some terms in the previous results to be written in the form where is an arbitrary constant (phase shift). |

Guessing solutions

[edit]When all other methods for solving an ODE fail, or in the cases where we have some intuition about what the solution to a DE might look like, it is sometimes possible to solve a DE simply by guessing the solution and validating it is correct. To use this method, we simply guess a solution to the differential equation, and then plug the solution into the differential equation to verify whether it satisfies the equation. If it does then we have a particular solution to the DE, otherwise we start over again and try another guess. For instance we could guess that the solution to a DE has the form: since this is a very common solution that physically behaves in a sinusoidal way.

In the case of a first order ODE that is non-homogeneous we need to first find a solution to the homogeneous portion of the DE, otherwise known as the associated homogeneous equation, and then find a solution to the entire non-homogeneous equation by guessing. Finally, we add both of these solutions together to obtain the general solution to the ODE, that is:

Software for ODE solving

[edit]- Maxima, an open-source computer algebra system.

- COPASI, a free (Artistic License 2.0) software package for the integration and analysis of ODEs.

- MATLAB, a technical computing application (MATrix LABoratory)

- GNU Octave, a high-level language, primarily intended for numerical computations.

- Scilab, an open source application for numerical computation.

- Maple, a proprietary application for symbolic calculations.

- Mathematica, a proprietary application primarily intended for symbolic calculations.

- SymPy, a Python package that can solve ODEs symbolically

- Julia (programming language), a high-level language primarily intended for numerical computations.

- SageMath, an open-source application that uses a Python-like syntax with a wide range of capabilities spanning several branches of mathematics.

- SciPy, a Python package that includes an ODE integration module.

- Chebfun, an open-source package, written in MATLAB, for computing with functions to 15-digit accuracy.

- GNU R, an open source computational environment primarily intended for statistics, which includes packages for ODE solving.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Dennis G. Zill (15 March 2012). A First Course in Differential Equations with Modeling Applications. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-285-40110-2. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ "What is the origin of the term "ordinary differential equations"?". hsm.stackexchange.com. Stack Exchange. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- ^ Karras, Tero; Aittala, Miika; Aila, Timo; Laine, Samuli (2022). "Elucidating the Design Space of Diffusion-Based Generative Models". arXiv:2206.00364 [cs.CV].

- ^ Butcher, J. C. (2000-12-15). "Numerical methods for ordinary differential equations in the 20th century". Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics. Numerical Analysis 2000. Vol. VI: Ordinary Differential Equations and Integral Equations. 125 (1): 1–29. Bibcode:2000JCoAM.125....1B. doi:10.1016/S0377-0427(00)00455-6. ISSN 0377-0427.

- ^ Greenberg, Michael D. (2012). Ordinary differential equations. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-23002-2.

- ^ Acton, Forman S. (1990). Numerical methods that work. Spectrum. Washington, D.C: Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-1-4704-5727-3.

- ^ Denis, Byakatonda (2020-12-10). "An Overview of Numerical and Analytical Methods for solving Ordinary Differential Equations". arXiv:2012.07558 [math.HO].

- ^ Mathematics for Chemists, D.M. Hirst, Macmillan Press, 1976, (No ISBN) SBN: 333-18172-7

- ^ Kreyszig (1972, p. 64)

- ^ Simmons (1972, pp. 1, 2)

- ^ Halliday & Resnick (1977, p. 78)

- ^ Tipler (1991, pp. 78–83)

- ^ a b Harper (1976, p. 127)

- ^ Kreyszig (1972, p. 2)

- ^ Simmons (1972, p. 3)

- ^ a b Kreyszig (1972, p. 24)

- ^ Simmons (1972, p. 47)

- ^ Harper (1976, p. 128)

- ^ Kreyszig (1972, p. 12)

- ^ Ascher & Petzold (1998, p. 12)

- ^ Achim Ilchmann; Timo Reis (2014). Surveys in Differential-Algebraic Equations II. Springer. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-3-319-11050-9.

- ^ Ascher & Petzold (1998, p. 5)

- ^ Kreyszig (1972, p. 78)

- ^ Kreyszig (1972, p. 4)

- ^ Vardia T. Haimo (1985). "Finite Time Differential Equations". 1985 24th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. pp. 1729–1733. doi:10.1109/CDC.1985.268832. S2CID 45426376.

- ^ Crelle, 1866, 1868

- ^ Dresner (1999, p. 9)

- ^ Logan, J. (2013). Applied mathematics (4th ed.).

- ^ Ascher & Petzold (1998, p. 13)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Elementary Differential Equations and Boundary Value Problems (4th Edition), W.E. Boyce, R.C. Diprima, Wiley International, John Wiley & Sons, 1986, ISBN 0-471-83824-1

- ^ Boscain; Chitour 2011, p. 21

- ^ a b Mathematical Handbook of Formulas and Tables (3rd edition), S. Lipschutz, M. R. Spiegel, J. Liu, Schaum's Outline Series, 2009, ISC_2N 978-0-07-154855-7

- ^ Further Elementary Analysis, R. Porter, G.Bell & Sons (London), 1978, ISBN 0-7135-1594-5

- ^ a b Mathematical methods for physics and engineering, K.F. Riley, M.P. Hobson, S.J. Bence, Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISC_2N 978-0-521-86153-3

References

[edit]- Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert (1977), Physics (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-71716-9

- Harper, Charlie (1976), Introduction to Mathematical Physics, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-487538-9

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1972), Advanced Engineering Mathematics (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-50728-8.

- Polyanin, A. D. and V. F. Zaitsev, Handbook of Exact Solutions for Ordinary Differential Equations (2nd edition), Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2003. ISBN 1-58488-297-2

- Simmons, George F. (1972), Differential Equations with Applications and Historical Notes, New York: McGraw-Hill, LCCN 75173716

- Tipler, Paul A. (1991), Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Extended version (3rd ed.), New York: Worth Publishers, ISBN 0-87901-432-6

- Boscain, Ugo; Chitour, Yacine (2011), Introduction à l'automatique (PDF) (in French)

- Dresner, Lawrence (1999), Applications of Lie's Theory of Ordinary and Partial Differential Equations, Bristol and Philadelphia: Institute of Physics Publishing, ISBN 978-0750305303

- Ascher, Uri; Petzold, Linda (1998), Computer Methods for Ordinary Differential Equations and Differential-Algebraic Equations, SIAM, ISBN 978-1-61197-139-2

Bibliography

[edit]- Coddington, Earl A.; Levinson, Norman (1955). Theory of Ordinary Differential Equations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hartman, Philip (2002) [1964], Ordinary differential equations, Classics in Applied Mathematics, vol. 38, Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, doi:10.1137/1.9780898719222, ISBN 978-0-89871-510-1, MR 1929104

- W. Johnson, A Treatise on Ordinary and Partial Differential Equations, John Wiley and Sons, 1913, in University of Michigan Historical Math Collection

- Ince, Edward L. (1944) [1926], Ordinary Differential Equations, Dover Publications, New York, ISBN 978-0-486-60349-0, MR 0010757

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Witold Hurewicz, Lectures on Ordinary Differential Equations, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-49510-8

- Ibragimov, Nail H. (1993). CRC Handbook of Lie Group Analysis of Differential Equations Vol. 1-3. Providence: CRC-Press. ISBN 0-8493-4488-3..

- Teschl, Gerald (2012). Ordinary Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems. Providence: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-8328-0.

- A. D. Polyanin, V. F. Zaitsev, and A. Moussiaux, Handbook of First Order Partial Differential Equations, Taylor & Francis, London, 2002. ISBN 0-415-27267-X

- D. Zwillinger, Handbook of Differential Equations (3rd edition), Academic Press, Boston, 1997.

External links

[edit]- "Differential equation, ordinary", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- EqWorld: The World of Mathematical Equations, containing a list of ordinary differential equations with their solutions.

- Online Notes / Differential Equations by Paul Dawkins, Lamar University.

- Differential Equations, S.O.S. Mathematics.

- A primer on analytical solution of differential equations from the Holistic Numerical Methods Institute, University of South Florida.

- Ordinary Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems lecture notes by Gerald Teschl.

- Notes on Diffy Qs: Differential Equations for Engineers An introductory textbook on differential equations by Jiri Lebl of UIUC.

- Modeling with ODEs using Scilab A tutorial on how to model a physical system described by ODE using Scilab standard programming language by Openeering team.

- Solving an ordinary differential equation in Wolfram|Alpha

Ordinary differential equation

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Overview and Importance

An ordinary differential equation (ODE) is an equation that relates a function of a single independent variable to its derivatives with respect to that variable.[1] Unlike partial differential equations (PDEs), which involve functions of multiple independent variables and their partial derivatives, ODEs are restricted to one independent variable, typically time or space along a single dimension.[1] This fundamental distinction allows ODEs to model phenomena evolving along a one-dimensional parameter, making them essential for describing dynamic processes in various fields.[9] ODEs arise naturally in modeling real-world systems across disciplines. In physics, Newton's second law of motion expresses the relationship between force, mass, and acceleration as , where is mass, is position, and is the net force, forming a second-order ODE for the trajectory of a particle.[1] In biology, population growth is often modeled by the logistic equation , where is population size, is the growth rate, and is the carrying capacity, capturing growth limited by resource constraints.[10] In engineering, circuit analysis uses ODEs such as the first-order equation for an RC circuit, , where is charge, is resistance, is capacitance, and is voltage, to predict transient responses.[11] The importance of ODEs stems from their role in analyzing dynamical systems, where they describe how states evolve over time, enabling predictions of long-term behavior and stability.[12] In control theory, ODEs model feedback mechanisms, such as in PID controllers, to ensure system stability and performance in applications like robotics and aerospace.[7] Scientific computing relies on numerical solutions of ODEs for simulations in weather forecasting, chemical reactions, and epidemiology, where analytical solutions are infeasible.[13] Common formulations include initial value problems (IVPs), specifying conditions at a starting point to determine future evolution, and boundary value problems (BVPs), imposing conditions at endpoints for steady-state or spatial analyses.[14] The foundations of ODEs trace back to the calculus developed by Newton and Leibniz in the late 17th century.[15]Historical Development

The origins of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) trace back to the late 17th century, coinciding with the invention of calculus. Isaac Newton developed his method of fluxions around 1665–1666, applying it to solve inverse tangent and quadrature problems in mechanics, such as deriving the paths of bodies under gravitational forces, which implicitly involved solving ODEs for planetary motion. These ideas were elaborated in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica published in 1687. Independently, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz introduced the differential notation in 1675 and published his calculus framework in 1684, enabling the formulation of explicit differential relations; by the 1690s, he collaborated with the Bernoulli brothers—Jacob and Johann—to solve early examples of first-order ODEs, including the separable and Bernoulli types, marking the formal beginning of systematic DE studies.[16] In the 18th century, Leonhard Euler advanced the field by devising general methods for integrating first- and second-order ODEs, including homogeneous equations, exact differentials, and linear types, often motivated by problems in celestial mechanics and fluid dynamics. His comprehensive treatments appear in works like Introductio in analysin infinitorum (1748) and Institutionum calculi integralis (1768–1770). Joseph-Louis Lagrange built on this by linking ODEs to variational calculus in the 1760s, formulating the Euler-Lagrange equation to derive differential equations from optimization principles in mechanics; this was detailed in his Mécanique Analytique (1788), establishing analytical mechanics as a cornerstone of ODE applications.[17][18] The 19th century brought rigor to ODE theory, beginning with Augustin-Louis Cauchy's foundational work on existence and convergence. In 1824, Cauchy proved the existence of solutions to first-order ODEs using successive polygonal approximations (the precursor to the Euler method), showing uniform convergence under Lipschitz conditions in his Mémoire sur les intégrales définies. Charles-François Sturm and Joseph Liouville then developed the theory for linear second-order boundary value problems in 1836–1837, introducing separation of variables, oscillation theorems, and eigenvalue expansions that form the basis of Sturm-Liouville theory, published in the Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées. Sophus Lie pioneered symmetry methods in the 1870s, using continuous transformation groups to reduce the order of nonlinear ODEs and find invariants, with core ideas outlined in his 1874 paper "Über die Integration durch unbestimmte Transcendenten" and expanded in Theorie der Transformationsgruppen (1888–1893).[19][20] Late 19th- and early 20th-century developments emphasized qualitative analysis and computation. Henri Poincaré initiated qualitative theory in the 1880s–1890s, analyzing periodic orbits, stability, and bifurcations in nonlinear systems via phase portraits and the Poincaré-Bendixson theorem, primarily in Les Méthodes Nouvelles de la Mécanique Céleste (1892–1899). Concurrently, Aleksandr Lyapunov established stability criteria in 1892 through his doctoral thesis Общая задача об устойчивости движения (The General Problem of the Stability of Motion), introducing Lyapunov functions for asymptotic stability without explicit solutions. On the numerical front, Carl David Tolmé Runge proposed iterative methods for accurate approximation in 1895, detailed in "Über die numerische Auflösung von Differentialgleichungen" (Mathematische Annalen), while Wilhelm Kutta refined it to a fourth-order scheme in 1901, published as "Beitrag zur näherungsweisen Integration totaler Differentialgleichungen" (Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik), laying the groundwork for modern numerical solvers.[21]Fundamental Definitions

General Form and Classification

An ordinary differential equation (ODE) is an equation involving a function of a single independent variable and its derivatives with respect to that variable. The general form of an nth-order ODE is given by where is the unknown function and is a given function of arguments.[22] This form encompasses equations where the derivatives are taken with respect to only one independent variable, distinguishing ODEs from partial differential equations.[1] ODEs are classified by their order, which is the highest order of derivative appearing in the equation. A first-order ODE involves only the first derivative, such as ; a second-order ODE includes up to the second derivative, like ; and higher-order equations follow analogously.[1] Another key classification is by linearity: an nth-order ODE is linear if it can be expressed as where the coefficients and are functions of , and the dependent variable and its derivatives appear only to the first power with no products among them or nonlinear functions applied. Otherwise, the equation is nonlinear.[1] Within linear ODEs, homogeneity refers to the case where the forcing term , yielding the homogeneous linear equation if , the equation is nonhomogeneous. ODEs are further classified as autonomous or non-autonomous based on explicit dependence on the independent variable. An autonomous ODE does not contain explicitly in the function , so it takes the form , meaning the right-hand side depends only on and its derivatives. Non-autonomous ODEs include explicit -dependence.[22] A representative example of a first-order linear ODE is where and are continuous functions; this is nonhomogeneous if and non-autonomous due to the explicit -dependence in the coefficients.[23] To specify a unique solution, an initial value problem (IVP) for an nth-order ODE pairs the equation with n initial conditions of the form , , ..., , where is a given initial point. The solution to the IVP is a function defined on some interval containing that satisfies both the ODE and the initial conditions.[1]Systems of ODEs

A system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) arises when multiple dependent variables evolve interdependently over time, extending the single-equation framework to model complex phenomena involving several interacting components. Such systems are compactly represented in vector form as , where is an -dimensional vector of unknown functions, and is a sufficiently smooth vector-valued function specifying the rates of change.[24] This notation unifies the equations into a single vector equation, facilitating analysis through linear algebra and dynamical systems theory.[25] First-order systems, where each component equation is of first order, serve as the canonical form for studying higher-order ODEs, allowing reduction of any th-order single equation to an equivalent system of first-order equations. To achieve this, introduce auxiliary variables representing successive derivatives; for instance, a second-order equation converts to the system , by setting and .[24] This transformation preserves the original dynamics while enabling uniform treatment, such as matrix methods for linear cases.[26] Practical examples illustrate the power of systems in capturing real-world interactions. In ecology, the Lotka-Volterra equations model predator-prey dynamics as the coupled system , , where and represent prey and predator populations, respectively, are parameters reflecting growth and interaction rates, and periodic oscillations emerge from the balance of these terms; this model originated from Alfred Lotka's 1925 analysis of chemical kinetics applied to biology and Vito Volterra's 1926 mathematical extensions to population fluctuations.[27] In mechanics, systems describe multi-degree-of-freedom setups, such as two coupled pendulums or masses connected by springs, yielding equations like and , which reduce to first-order vector form to analyze energy transfer and resonance modes.[24] The phase space provides a geometric interpretation of systems, representing the state of the system as a point in (for first-order systems) or (including velocities for second-order), with solution curves tracing trajectories that evolve according to .[28] Equilibrium points occur where , and the topology of trajectories reveals qualitative behaviors like stability or chaos without solving explicitly.[29]Solution Concepts

A solution to an ordinary differential equation (ODE) is a function that satisfies the equation identically over some domain.[1] For an ODE involving a single dependent variable and independent variable , such a solution must hold for all points in its domain where the derivatives are defined.[1] An explicit solution expresses directly as a function of , denoted as , where is differentiable and substituting and its derivatives into the ODE yields an identity on an open interval .[1] In contrast, an implicit solution is given by an equation , where is continuously differentiable, and the implicit function theorem ensures that can be locally solved for as a function of , with the resulting satisfying the ODE on an interval.[30] Implicit solutions often arise when explicit forms are not elementary or feasible.[30] The general solution of an th-order ODE is the family of all solutions, typically comprising linearly independent particular solutions combined with arbitrary constants, reflecting the integrations needed to solve it.[31] A particular solution is obtained by assigning specific values to these arbitrary constants, yielding a unique member of the general solution family.[1] For initial value problems, these constants are chosen to match given initial conditions.[1] Solutions are defined on intervals, and the maximal interval of existence for a solution to an initial value problem is the largest open interval containing the initial point where the solution remains defined and satisfies the ODE.[32] Solutions of finite duration occur when this maximal interval is bounded, often due to singularities in the ODE coefficients or nonlinear terms causing blow-up in finite time.[32]Existence and Uniqueness

While general ordinary differential equations may have solutions defined only on limited maximal intervals due to finite-time blow-up or other obstructions, linear ordinary differential equations with continuous coefficients defined on an interval guarantee that any local solution extends uniquely to a global solution on the entire interval. This important special case is discussed in detail in the "Global Solutions and Maximal Intervals" subsection below.Picard-Lindelöf Theorem

The Picard–Lindelöf theorem establishes local existence and uniqueness of solutions for first-order ordinary differential equations under suitable regularity conditions on the right-hand side function. Specifically, consider the initial value problem where is defined on a rectangular domain with , . Assume is continuous on and satisfies the Lipschitz condition with respect to the -variable: there exists a constant such that for all . Let . Then, there exists an with and such that the initial value problem has a unique continuously differentiable solution defined on the interval .[33][34] The Lipschitz condition ensures that does not vary too rapidly in the -direction, preventing solutions from "branching" or diverging excessively near the initial point. This condition is local, applying within the rectangle , and can be verified, for instance, if is continuously differentiable with respect to and the partial derivative is bounded on , since the mean value theorem implies the Lipschitz bound with . Without the Lipschitz condition, while existence may still hold under mere continuity (as in the Peano existence theorem), uniqueness can fail dramatically.[35][36] The proof relies on the method of successive approximations, known as Picard iteration. Define the sequence of functions by (the constant initial value) and for , with each considered on the interval . The continuity of ensures that each is continuous on , and the Lipschitz condition allows application of the Banach fixed-point theorem in the complete metric space of continuous functions on equipped with the sup-norm, scaled appropriately by a factor involving . Specifically, the integral operator is a contraction mapping on a closed ball of radius in this space, so it has a unique fixed point , which satisfies the integral equation equivalent to the differential equation and initial condition. The iterates converge uniformly to this fixed point, yielding the unique solution.[33][34][35] A classic counterexample illustrating the necessity of the Lipschitz condition occurs with the equation , , defined for and extended appropriately. Here, is continuous at but not Lipschitz continuous near , as the difference quotient can become arbitrarily large for small . Solutions include the trivial for all , and the non-trivial for and for , both satisfying the equation and initial condition, demonstrating non-uniqueness. Further solutions can be constructed by piecing together zero and quadratic segments up to any point, confirming that multiple solutions emanate from the initial point without the Lipschitz restriction.[36][35]Peano Existence Theorem

The Peano existence theorem establishes local existence of solutions to first-order ordinary differential equations under minimal regularity assumptions on the right-hand side function. Consider the initial value problem where is continuous on an open rectangle containing the initial point , with and . Let . Then there exists (specifically, ) such that at least one continuously differentiable function defined on the interval satisfies the differential equation and the initial condition. This result, originally proved by Giuseppe Peano in 1890, relies solely on the continuity of and guarantees existence without addressing uniqueness. A standard proof constructs a sequence of Euler polygonal approximations on a fine partition of the interval . For step size , the approximations are defined recursively by and , where . Since is continuous on the compact closure of , it is bounded by , making the approximations uniformly bounded by . Moreover, the approximations are equicontinuous, as changes between steps are controlled by . By the Arzelà-Ascoli theorem, a subsequence converges uniformly to a continuous limit function , which satisfies the integral equation and hence solves the ODE on ; a symmetric argument covers .[37] An illustrative example of the theorem's scope, due to Peano himself, is the initial value problem Here, is continuous everywhere, so the theorem guarantees local solutions exist. Indeed, is a solution for all . Additionally, for any , the function defined by for and for is also a solution, yielding infinitely many solutions through the origin. This demonstrates non-uniqueness, as the partial derivative is unbounded near , violating Lipschitz continuity there. The theorem's limitation lies in its weaker hypothesis of mere continuity, which suffices for existence but permits multiple solutions, unlike stronger results requiring Lipschitz continuity for both existence and uniqueness.[37]Global Solutions and Maximal Intervals

For an initial value problem (IVP) given by with , where is continuous on some domain , local existence theorems guarantee a solution on some interval around . However, such solutions can often be extended to a larger domain. The maximal interval of existence is the largest open interval containing such that the solution is defined and satisfies the equation on this interval, with , and the solution cannot be extended continuously to any larger interval while remaining in . This interval may be bounded or unbounded, depending on the behavior of and the solution trajectory.[38][32] The solution on the maximal interval possesses key properties related to continuation. Specifically, if , then as , the solution must escape every compact subset of the domain, meaning or approaches the boundary of in a way that prevents further extension. This criterion ensures that the maximal interval is indeed the full domain of the solution; the process stops precisely when the solution "blows up" or hits an obstacle in the domain. Similarly, if , blow-up occurs as . Under local Lipschitz continuity of in , this extension is unique, so global solutions, if they exist, are unique on their common domain.[39] Global existence occurs when the maximal interval is the entire real line , meaning the solution is defined for all . A sufficient condition for this is that satisfies a linear growth bound, such as for some constant and all . This bound prevents the solution from growing exponentially fast enough to escape compact sets in finite time, ensuring it remains bounded on any finite interval and thus extendable indefinitely. Without such growth restrictions, solutions may exhibit blow-up phenomena, where they become unbounded in finite time. For instance, consider the scalar equation with ; its explicit solution is which satisfies the IVP on , the maximal interval, and blows up as since . This quadratic nonlinearity allows superlinear growth, leading to the finite-time singularity.[38][32] In contrast to the general nonlinear case, linear ordinary differential equations exhibit unconditional global existence on the interval where the coefficients are defined and continuous. Specifically, consider the homogeneous linear system where is continuous (or smooth) on . Any local solution extends uniquely to a solution on all of . The proof proceeds in steps. First, the maximal interval of existence is considered. On any compact subinterval , continuity of gives a uniform bound . The norm satisfies and by Grönwall's inequality, on , so is bounded on compact subintervals. To show that there is no finite-time breakdown, assume toward a contradiction that the right endpoint . Choose such that . By compactness of and the continuity of on , we have Using the exponential bound from Grönwall's inequality applied on compact subintervals of , there exists Consider the rectangle where . The vector field is continuous on and Lipschitz in with constant ; moreover, on . By the uniform local existence and uniqueness theorem on rectangles (a consequence of the Picard–Lindelöf theorem with uniform estimates), there exists (depending only on ) such that for any and any with , the IVP , , has a unique solution on that remains in . In particular, choose and set (note ). The corresponding solution extends to with . By uniqueness, this solution agrees with the original on , hence it extends past , contradicting maximality. A similar argument, applied to a right neighborhood of and extending backward in time, shows that also leads to a contradiction. Thus, and . A concise summary: On compact intervals, continuity of bounds it uniformly; Grönwall yields an exponential bound on , preventing blow-up. Near a putative endpoint, compactness bounds both and ; the uniform Picard–Lindelöf theorem on a rectangle provides continuation, yielding a contradiction. Hence, solutions are global on . One may also argue by the integral equation : boundedness of and on implies that has a limit as ; starting the IVP at with that limit and using uniqueness again yields the continuation.[32] This property extends to the nonhomogeneous case with continuous , using similar boundedness arguments.[40][41]Analytical Solution Techniques

First-Order Equations

First-order ordinary differential equations, typically written as , can often be solved exactly when they possess specific structures that allow for analytical integration or transformation. These methods exploit the form of the equation to reduce it to integrable expressions, providing explicit or implicit solutions in terms of elementary functions. The primary techniques apply to separable, homogeneous, exact, linear, and Bernoulli equations, each addressing distinct classes of first-order ODEs.[42] These methods yield general solutions containing an arbitrary constant . For Cauchy problems (initial value problems), where an initial condition is specified, substitute the initial values into the general solution to determine and obtain the unique particular solution. Separable equations are those that can be expressed as , where the right-hand side separates into a product of a function of alone and a function of alone. To solve, rearrange to and integrate both sides: , yielding an implicit solution that may be solved explicitly for if possible. This method works because the separation allows independent integration with respect to each variable.[43][44] For example, consider . Here, and , so . Integrating gives , or where . This solution satisfies the original equation for , with as a trivial singular solution. Separable equations commonly arise in modeling exponential growth or decay processes.[43][45] Homogeneous equations are those of the form , where depends only on the ratio . Use the substitution , so and . Substituting gives , which rearranges to or . Integrating both sides yields , resulting in an implicit relation for (and thus ) in terms of . This reduces the homogeneous equation to a separable one.[46] For example, consider . Here . Substituting yields , so and . Integrating gives , so . Homogeneous equations often model phenomena invariant under scaling. Exact equations take the differential form , where the equation is exact if . In this case, there exists a function such that and , so the solution is . To find , integrate with respect to (treating constant) to get , then determine by differentiating with respect to and matching to . If the equation is not exact, an integrating factor or may render it exact, provided it satisfies certain conditions like being a function of alone.[47][48] As an illustration, for , compute , confirming exactness. Integrating gives ; then implies . Thus . Verification shows it satisfies equivalent to the original. Exact methods stem from conservative vector fields in multivariable calculus.[47] Linear first-order equations are written in standard form , where P and Q are functions of x. The solution involves an integrating factor . Multiplying through by yields , which is . Integrating gives , so . This technique, attributed to Euler, transforms the equation into an exact derivative. For the homogeneous case (): .[42][49] For instance, solve . Here P(x)=2, so . Then , integrating: e^{2x} y = e^x + C, thus y = e^{-x} + C e^{-2x}. Initial condition y(0)=0 gives C=1, so y= e^{-x} - e^{-2x}. Linear equations model phenomena like mixing problems or electrical circuits.[42][50] Bernoulli equations generalize linear ones to for n ≠ 0,1. The substitution v = y^{1-n} reduces it to a linear equation in v: divide by y^n to get y^{-n} y' + P y^{1-n} = Q, then v' = (1-n) y^{-n} y', so y^{-n} y' = v' / (1-n); plug in: v'/(1-n) + P v = Q, or v' + (1-n) P v = (1-n) Q. Solve this linear for v, then y = v^{1/(1-n)}. This reduction, due to Jacob Bernoulli, handles nonlinear terms via power substitution.[51][52] Consider . Here n=3, P=1, Q=x; let v= y^{-2}, then v' = -2 y^{-3} y', so y^{-3} y' = - (1/2) v'; equation becomes - (1/2) v' + v = x, or v' - 2 v = -2 x. Integrating factor μ= e^{\int -2 dx}= e^{-2x}; d/dx (e^{-2x} v)= -2 x e^{-2x}, integrate: e^{-2x} v = ∫ -2 x e^{-2x} dx. Using integration by parts (u=x, dv=-2 e^{-2x} dx, du=dx, v= e^{-2x}): ∫ = x e^{-2x} - ∫ e^{-2x} dx = x e^{-2x} + (1/2) e^{-2x} + C = e^{-2x} (x + 1/2) + C. Thus e^{-2x} v = e^{-2x} (x + 1/2) + C, v= x + 1/2 + C e^{2x}. Then y= v^{-1/2}. For C=0, y= (x + 1/2)^{-1/2}. Bernoulli equations appear in logistic growth models with nonlinear terms.[51][53]Second-Order Equations

Second-order ordinary differential equations (ODEs) are fundamental in modeling oscillatory and other dynamic systems, often appearing in physics and engineering. The linear homogeneous case with constant coefficients takes the form where and are constants.[54] Solutions are found by assuming , leading to the characteristic equation .[55] The roots determine the general solution form.[56] If the roots are distinct real numbers, , the general solution is , where are arbitrary constants.[54] For repeated roots , the solution is . When the roots are complex conjugates with , the solution is .[57] These cases cover all possibilities for constant-coefficient homogeneous equations.[58] For nonhomogeneous equations of the form , the general solution is the sum of the homogeneous solution and a particular solution , so .[59] The method of undetermined coefficients finds by guessing a form similar to , adjusted for overlaps with . For polynomial right-hand sides, assume a polynomial of the same degree; for exponentials , assume ; modifications like multiplying by or handle resonances. This method works efficiently when is a polynomial, exponential, sine, cosine, or their products.[60] Cauchy-Euler equations, a variable-coefficient subclass, have the form for , where are constants.[61] The substitution , , transforms it into a constant-coefficient equation , solvable via the characteristic method.[62] The roots yield solutions in terms of powers of or logarithms for repeated roots.[63] A classic example is the simple harmonic oscillator , where is constant, modeling undamped vibrations like a mass-spring system.[64] The characteristic roots are , giving the solution , or equivalently , with period .[64] This illustrates oscillatory behavior central to many physical applications.[65]Higher-Order Linear Equations

A higher-order linear ordinary differential equation of order takes the general form where the coefficients for are continuous functions with , and is the nonhomogeneous term, often called the forcing function.[66][67] This equation generalizes lower-order cases, such as second-order equations, to arbitrary .[68] For the associated homogeneous equation, obtained by setting , the set of all solutions forms an -dimensional vector space over the reals.[69] The general solution to the homogeneous equation is a linear combination , where are arbitrary constants and is a fundamental set of linearly independent solutions.[66][70] Linear independence of this set can be verified using the Wronskian determinant, which is nonzero on intervals where the solutions are defined.[71] The general solution to the nonhomogeneous equation is , where is any particular solution.[68] A systematic approach to finding is the method of variation of parameters, originally developed by Joseph-Louis Lagrange in 1774.[72][73] This method posits , where the functions are determined by solving a system of first-order linear equations for the derivatives .[74][75] The system arises from substituting the assumed form into the original equation and imposing conditions to ensure the derivatives of do not introduce extraneous terms, with the coefficients involving the Wronskian of the fundamental set.[76] When the coefficients are constants, the homogeneous equation simplifies to , and a standard solution technique involves assuming solutions of the form .[77] Substituting this form yields the characteristic equation , a polynomial whose roots dictate the fundamental solutions.[69][66] Distinct real roots produce terms ; repeated roots of multiplicity introduce factors like for ; and complex conjugate roots yield and .[77] This approach, known as the method of undetermined coefficients for the exponential ansatz, traces back to Leonhard Euler.[69] For equations with variable coefficients, explicit fundamental solutions are often unavailable in closed form, and techniques such as power series methods or reduction of order are applied to construct solutions, particularly around regular singular points.[70][78]Advanced Analytical Methods

Reduction of Order

The reduction of order method provides a systematic way to determine additional linearly independent solutions to linear homogeneous ordinary differential equations when one nontrivial solution is already known, thereby lowering the effective order of the equation to be solved. This technique is especially valuable for second-order equations, where knowing one solution allows the construction of a second, completing the general solution basis. For a second-order linear homogeneous ODE of the form if is a known nonzero solution, a second solution can be sought in the form , where is a function to be determined. Substituting this ansatz into the ODE yields Since satisfies the original equation, the terms involving simplify, leaving an equation that depends only on : Dividing by (assuming ) reduces this to a first-order ODE in : which is separable and solvable explicitly for , followed by integration to find . The general solution is then .[79][80] This substitution leverages the structure of linear homogeneous equations, ensuring the resulting first-order equation lacks the original dependent variable , thus simplifying the problem without requiring full knowledge of the coefficient functions. For instance, consider the equation , where one solution is (verifiable by direct substitution). Applying the method gives , yielding the general solution .[81] The approach generalizes to nth-order linear homogeneous ODEs. For an nth-order equation with a known solution , assume . Differentiation produces higher-order terms, but upon substitution, the equation for reduces to an (n-1)th-order ODE in , as the terms involving itself vanish due to satisfying the original ODE. Iterating this process allows construction of a full basis of n linearly independent solutions if needed.[82] Beyond cases with known solutions, reduction of order applies to nonlinear ODEs missing certain variables, exploiting symmetries in the equation structure. For a second-order equation missing the dependent variable , such as , set , transforming it into a first-order equation in , which can then be solved followed by integration for . This substitution works because , eliminating entirely.[79] For autonomous second-order equations missing the independent variable , like , the substitution leads to , reducing to the first-order equation . This chain rule application exploits the absence of explicit -dependence to treat as a function of . An example is the equation ; the reduction yields , or , solvable as , with subsequent integration for .[83] In the linear case with variable coefficients, such as , if one solution is known to be (e.g., from assuming a simple exponential form), the method proceeds as described, often simplifying the integrating factor in the reduced first-order equation to . This confirms the second solution's form without resolving the full characteristic equation.[84]Integrating Factors and Variation of Parameters

The method of integrating factors provides a systematic approach to solving first-order linear ordinary differential equations of the form , where and are continuous functions.[23] An integrating factor is defined as , which, when multiplied through the equation, transforms the left-hand side into the exact derivative .[23] Integrating both sides yields , allowing the general solution to be obtained directly.[23] This technique, originally developed by Leonhard Euler in his 1763 paper "De integratione aequationum differentialium," leverages the product rule to render the equation integrable.[49] Although primarily associated with first-order equations, integrating factors can extend to second-order linear ordinary differential equations in specific forms, such as when the equation admits a known solution that allows reduction to first-order or possesses symmetries enabling factorization.[85] However, for general second-order linear equations , the method is not always applicable without additional structure, and alternative approaches like variation of parameters are typically preferred.[76] The variation of parameters method, attributed to Joseph-Louis Lagrange and first used in his work on celestial mechanics in 1766, addresses nonhomogeneous linear ordinary differential equations of nth order, , where a fundamental set of solutions to the associated homogeneous equation is known.[86] A particular solution is sought in the form , where the functions vary with . Substituting into the original equation and imposing the system of conditions for and ensures the derivatives align properly without introducing extraneous terms. This linear system for the is solved using Cramer's rule, involving the Wronskian , the determinant of the matrix formed by the fundamental solutions and their derivatives up to order . The solutions are , where is the determinant obtained by replacing the i-th column of the Wronskian matrix with the column .[76] Integrating each then yields the , and thus ; the general solution is , with the homogeneous solution. A representative example arises in the forced harmonic oscillator, governed by , with fundamental solutions and , where the Wronskian . For with , the particular solution via variation of parameters is , with and , leading to integrals that evaluate to a resonant or non-resonant form depending on .[87] This method highlights the flexibility of variation of parameters for handling arbitrary forcing terms in physical systems like damped oscillators or circuits.[88]Reduction to Quadratures

Reduction to quadratures encompasses techniques that transform ordinary differential equations (ODEs) into integral forms, allowing solutions to be expressed explicitly or implicitly through quadratures, often via targeted substitutions that exploit the equation's structure. These methods are particularly effective for certain classes of first-order nonlinear ODEs, where direct integration becomes feasible after reduction. Unlike general numerical approaches, reduction to quadratures yields analytical expressions in terms of integrals, providing closed-form insights when the integrals are evaluable. For first-order autonomous equations of the form , the variables can be separated directly, yielding the integral form , which integrates to an implicit solution relating and . This represents the simplest case of reduction to quadratures, where the left-hand integral depends solely on and the right on . Such separation is possible because the right-hand side lacks explicit dependence on the independent variable.[89] The Clairaut equation, given by , where , admits a general solution via straight-line families obtained by treating as a constant parameter , yielding . To find the singular solution, which forms the envelope of this family, differentiate the parametric form with respect to : , solving for in terms of and substituting back into the general solution. This process reduces the problem to algebraic manipulation followed by quadrature for the envelope curve, without requiring further integration of the ODE itself.[90] The Lagrange equation, , with , is solved by differentiating to eliminate the parameter: , rearranging to . Introducing the substitution (so ), and noting , the equation becomes , but since is expressed from the original as , substitution yields a first-order equation in : . This separable form integrates to , reducing the original second-degree equation to a quadrature.[91] In general, substitutions or integrating factors can lead to exact differentials or separable forms amenable to quadrature, particularly for equations missing certain variables or possessing specific symmetries. For instance, the Riccati equation is reducible via the substitution , transforming it into the second-order linear homogeneous ODE . Solving this linear equation yields two independent solutions, from which is recovered as the logarithmic derivative, effectively reducing the nonlinear problem to quadratures through the known methods for linear ODEs.[92]Special Theories and Solutions

Singular and Envelope Solutions

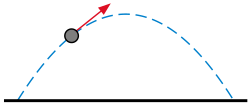

In ordinary differential equations, a singular solution is an envelope or other curve that satisfies the differential equation but cannot be derived from the general solution by assigning specific values to the arbitrary constants.[93] These solutions typically arise in first-order nonlinear equations and represent exceptional cases where the uniqueness theorem fails, often forming the boundary or limiting behavior of the family of general solutions.[94] Unlike particular solutions obtained by fixing constants, singular solutions are independent of those parameters and may touch multiple members of the general solution family at infinitely many points.[95] Envelope solutions specifically refer to the locus of a one-parameter family of curves defined by , where is the parameter, obtained by eliminating from the system This process yields the envelope as a curve that is tangent to each member of the family. If this envelope satisfies the original differential equation, it constitutes a singular solution.[93] The envelope often captures the "outermost" or bounding curve of the solution family, providing insight into the geometric structure of the solutions.[96] A classic example occurs in Clairaut's equation, a first-order nonlinear form , where . The general solution is the straight-line family . To find the singular solution, differentiate the general solution with respect to : solve for , and substitute back into the general solution. For , the equation is , yielding the general solution and the singular solution which is the parabola enveloping the family of straight lines.[95] This parabolic envelope touches each line at the point where the slope matches .[96] Cusp solutions and tac-loci represent subtypes or related features in the analysis of singular solutions. A cusp solution emerges when the envelope exhibits cusps, points where two branches of the envelope meet with the same tangent but opposite curvature, often indicating a failure of smoothness in the solution family.[93] The tac-locus (or tangent locus) is the curve traced by points of tangency between family members and the envelope, where curves touch with identical first derivatives but may differ in higher-order contact; unlike the envelope, the tac-locus does not always satisfy the differential equation.[93] These structures arise during the elimination process for the envelope and help classify the geometric singularities.[97] In geometry, envelope solutions describe boundaries of regions filled by curve families, such as the caustic formed by reflected rays in optics, where the envelope of reflected paths satisfies a derived ODE.[98] In physics, they model limiting trajectories; for instance, the envelope of projectile paths under gravity with fixed initial speed but varying angles forms a bounding parabola, representing the maximum range and height achievable, derived from the parametric family of parabolic arcs.Lie Symmetry Methods

Lie symmetry methods, pioneered by Sophus Lie in the late 19th century, offer a powerful framework for analyzing ordinary differential equations (ODEs) by identifying underlying symmetries that facilitate exact solutions or order reduction, particularly for nonlinear equations. These methods rely on continuous groups of transformations, known as Lie groups, that map solutions of an ODE to other solutions while preserving the equation's structure. Unlike ad-hoc techniques, Lie symmetries provide a systematic classification of all possible infinitesimal transformations, enabling the construction of invariant solutions and canonical forms. At the heart of these methods are Lie point symmetries, represented by infinitesimal generators in the form of vector fields , where and are smooth functions depending on the independent variable and dependent variable . A symmetry exists if the flow generated by leaves the solution manifold of the ODE invariant. To determine and , the generator must be prolonged to match the order of the ODE, incorporating higher derivatives. The first prolongation, for instance, extends to act on the derivative via , where and is the total derivative operator. Applying to the ODE and setting the result to zero on the solution surface yields the determining equations, a system of partial differential equations constraining and . For higher-order ODEs, such as second-order equations , the second prolongation is used: , with . Substituting into the ODE and collecting terms produces overdetermined determining equations, often linear in and , solvable by assuming polynomial dependence on and derivatives. These equations classify symmetries based on the ODE's form; for example, autonomous first-order ODEs admit the translation symmetry (, ), reflecting time-invariance.[99] Once symmetries are identified, they enable order reduction through invariant coordinates. The characteristics of the symmetry, solved from , yield first integrals that serve as new independent variables. Canonical coordinates are chosen such that the symmetry acts as a simple translation , transforming the original ODE into one of lower order in terms of and its derivatives with respect to . For the autonomous example , the invariants are and , reducing the equation to the quadrature , integrable by separation. Similarly, homogeneous first-order ODEs possess the scaling symmetry , with canonical coordinates , , yielding , again reducible to quadrature. These techniques extend effectively to nonlinear second-order ODEs, where a single symmetry reduces the equation to a first-order one. For instance, the nonlinear oscillator admits the symmetry , allowing reduction to a solvable first-order equation via invariants like , . In general, the maximal symmetry algebra for second-order ODEs is eight-dimensional (the projective group), achieved by equations linearizable to free particle motion, while nonlinear cases often have fewer symmetries but still benefit from reduction. Lie methods thus reveal the integrable structure of many nonlinear ODEs, with applications in physics, such as Painlevé equations, where symmetries classify transcendency.[99]Fuchsian and Sturm-Liouville Theories

Fuchsian ordinary differential equations are linear equations whose singular points are all regular singular points, including possibly at infinity. A point is a regular singular point of the linear ODE if and are analytic at , allowing solutions to exhibit controlled behavior near the singularity.[100][101] To solve such equations near a regular singular point at , the Frobenius method assumes a series solution of the form , where is to be determined and . Substituting this ansatz into the ODE yields the indicial equation, a quadratic in derived from the lowest-order terms, whose roots determine the possible exponents for the leading behavior of the solutions. The recurrence relations for the coefficients then follow, often leading to one or two linearly independent Frobenius series solutions, depending on whether the indicial roots differ by a non-integer./7:_Power_series_methods/7.3:_Singular_Points_and_the_Method_of_Frobenius) A classic example is the Bessel equation of order , given by which has a regular singular point at and an irregular singular point at infinity. The Frobenius method applied here produces the Bessel functions of the first and second kinds as solutions. Sturm-Liouville theory addresses boundary value problems for second-order linear ODEs in the self-adjoint form where , are positive on the interval , and is the eigenvalue parameter, subject to separated boundary conditions like and . This form ensures the operator is self-adjoint with respect to the weighted inner product .[102]/04:_Sturm-Liouville_Boundary_Value_Problems/4.02:_Properties_of_Sturm-Liouville_Eigenvalue_Problems) Key properties include that all eigenvalues are real and can be ordered as with as , and the corresponding eigenfunctions form an orthogonal basis in the weighted space, meaning for . The eigenfunctions are complete, allowing any sufficiently smooth function in the space to be expanded as a convergent series with ./04:_Sturm-Liouville_Boundary_Value_Problems/4.02:_Properties_of_Sturm-Liouville_Eigenvalue_Problems)[103] The Legendre equation, on , can be cast into Sturm-Liouville form with , , and , yielding eigenvalues and orthogonal eigenfunctions that are the Legendre polynomials .[104]Numerical and Computational Approaches

Basic Numerical Methods

Numerical methods provide approximations to solutions of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) when exact analytical solutions are unavailable or impractical to compute. These techniques discretize the continuous problem into a sequence of algebraic equations, typically by dividing the interval of interest into small steps of size . Basic methods, such as the Euler method and its variants, form the foundation for more sophisticated schemes and are particularly useful for illustrating key concepts like truncation error and stability.[105] The forward Euler method is the simplest explicit one-step scheme for solving the initial value problem , . It advances the approximation from to using the formula where . This method derives from the tangent line approximation to the solution curve at , effectively using the local linearization of the ODE. The local truncation error, which measures how closely the exact solution satisfies the numerical scheme over one step, is for the forward Euler method, arising from the neglect of higher-order terms in the Taylor expansion of the solution. Under suitable smoothness assumptions on and the existence of a unique solution (as guaranteed by the Picard-Lindelöf theorem), the global error accumulates to over a fixed interval.[106][107][8] To improve accuracy, the modified Euler method, also known as Heun's method, employs a predictor-corrector approach. It first predicts an intermediate value , then corrects using the average of the slopes at the endpoints: This trapezoidal-like averaging reduces the local truncation error to , making it a second-order method, though it requires two evaluations of per step compared to one for the forward Euler. The global error for the modified Euler method is thus , offering better efficiency for moderately accurate approximations.[108][109] For problems involving stiff ODEs—where the solution components decay at vastly different rates—the implicit backward Euler method provides enhanced stability. Defined by it uses the slope at the future point , requiring the solution of a nonlinear equation at each step (often via fixed-point iteration or Newton's method). Like the forward Euler, its local truncation error is , leading to a global error of , but its implicit nature ensures unconditional stability for linear test equations with negative eigenvalues, allowing larger step sizes without oscillations in stiff scenarios.[110][111] A simple example illustrates these methods: consider the ODE with , whose exact solution is . Applying the forward Euler method with over yields approximations like , , compared to the exact , showing the method's underestimation due to its explicit nature. The modified Euler method on the same problem produces , closer to the exact value, while the backward Euler gives , slightly overestimating but remaining stable even for larger . These errors align with the theoretical orders, highlighting the trade-offs in accuracy and computational cost.[106][108][110]Advanced Numerical Schemes