Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tracheal intubation

View on Wikipedia| Tracheal intubation | |

|---|---|

Anesthesiologist using the Glidescope video laryngoscope to intubate the trachea of a morbidly obese elderly person with challenging airway anatomy | |

| Specialty | Anesthesiology, emergency medicine, critical care medicine |

| ICD-9-CM | 96.04 |

| MeSH | D007442 |

| OPS-301 code | 8-701 |

| MedlinePlus | 003449 |

Tracheal intubation, usually simply referred to as intubation, is the placement of a flexible plastic tube into the trachea (windpipe) to maintain an open airway or to serve as a conduit through which to administer certain drugs. It is frequently performed in critically injured, ill, or anesthetized patients to facilitate ventilation of the lungs, including mechanical ventilation, and to prevent the possibility of asphyxiation or airway obstruction.

The most widely used route is orotracheal, in which an endotracheal tube is passed through the mouth and vocal apparatus into the trachea. In a nasotracheal procedure, an endotracheal tube is passed through the nose and vocal apparatus into the trachea. Other methods of intubation involve surgery and include the cricothyrotomy (used almost exclusively in emergency circumstances) and the tracheotomy, used primarily in situations where a prolonged need for airway support is anticipated.

Because it is an invasive and uncomfortable medical procedure, intubation is usually performed after administration of general anesthesia and a neuromuscular-blocking drug. It can, however, be performed in the awake patient with local or topical anesthesia or in an emergency without any anesthesia at all. Intubation is normally facilitated by using a conventional laryngoscope, flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope, or video laryngoscope to identify the vocal cords and pass the tube between them into the trachea instead of into the esophagus. Other devices and techniques may be used alternatively.

After the trachea has been intubated, a balloon cuff is typically inflated just above the far end of the tube to help secure it in place, to prevent leakage of respiratory gases, and to protect the tracheobronchial tree from receiving undesirable material such as stomach acid. The tube is then secured to the face or neck and connected to a T-piece, anesthesia breathing circuit, bag valve mask device, or a mechanical ventilator. Once there is no longer a need for ventilatory assistance or protection of the airway, the tracheal tube is removed; this is referred to as extubation of the trachea (or decannulation, in the case of a surgical airway such as a cricothyrotomy or a tracheotomy).

For centuries, tracheotomy was considered the only reliable method for intubation of the trachea. However, because only a minority of patients survived the operation, physicians undertook tracheotomy only as a last resort, on patients who were nearly dead. It was not until the late 19th century, however, that advances in understanding of anatomy and physiology, as well an appreciation of the germ theory of disease, had improved the outcome of this operation to the point that it could be considered an acceptable treatment option. Also at that time, advances in endoscopic instrumentation had improved to such a degree that direct laryngoscopy had become a viable means to secure the airway by the non-surgical orotracheal route. By the mid-20th century, the tracheotomy as well as endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation had evolved from rarely employed procedures to becoming essential components of the practices of anesthesiology, critical care medicine, emergency medicine, and laryngology.

Tracheal intubation can be associated with complications such as broken teeth or lacerations of the tissues of the upper airway. It can also be associated with potentially fatal complications such as pulmonary aspiration of stomach contents which can result in a severe and sometimes fatal chemical aspiration pneumonitis, or unrecognized intubation of the esophagus which can lead to potentially fatal anoxia. Because of this, the potential for difficulty or complications due to the presence of unusual airway anatomy or other uncontrolled variables is carefully evaluated before undertaking tracheal intubation. Alternative strategies for securing the airway must always be readily available.

Indications

[edit]Tracheal intubation is indicated in a variety of situations when illness or a medical procedure prevents a person from maintaining a clear airway, breathing, and oxygenating the blood. In these circumstances, oxygen supplementation using a simple face mask is inadequate.

Depressed level of consciousness

[edit]Perhaps the most common indication for tracheal intubation is for the placement of a conduit through which nitrous oxide or volatile anesthetics may be administered. General anesthetic agents, opioids, and neuromuscular-blocking drugs may diminish or even abolish the respiratory drive. Although it is not the only means to maintain a patent airway during general anesthesia, intubation of the trachea provides the most reliable means of oxygenation and ventilation[1] and the greatest degree of protection against regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration.[2]

Damage to the brain (such as from a massive stroke, non-penetrating head injury, intoxication or poisoning) may result in a depressed level of consciousness. When this becomes severe to the point of stupor or coma (defined as a score on the Glasgow Coma Scale of less than 8),[3] dynamic collapse of the extrinsic muscles of the airway can obstruct the airway, impeding the free flow of air into the lungs. Furthermore, protective airway reflexes such as coughing and swallowing may be diminished or absent. Tracheal intubation is often required to restore patency (the relative absence of blockage) of the airway and protect the tracheobronchial tree from pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents.[4]

Hypoxemia

[edit]Intubation may be necessary for a patient with decreased oxygen content and oxygen saturation of the blood caused when their breathing is inadequate (hypoventilation), suspended (apnea), or when the lungs are unable to sufficiently transfer gasses to the blood.[5] Such patients, who may be awake and alert, are typically critically ill with a multisystem disease or multiple severe injuries.[1] Examples of such conditions include cervical spine injury, multiple rib fractures, severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or near-drowning. Specifically, intubation is considered if the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) is less than 60 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) while breathing an inspired O2 concentration (FIO2) of 50% or greater. In patients with elevated arterial carbon dioxide, an arterial partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2) greater than 45 mm Hg in the setting of acidemia would prompt intubation, especially if a series of measurements demonstrate a worsening respiratory acidosis. Regardless of the laboratory values, these guidelines are always interpreted in the clinical context.[6]

Airway obstruction

[edit]Actual or impending airway obstruction is a common indication for intubation of the trachea. Life-threatening airway obstruction may occur when a foreign body becomes lodged in the airway; this is especially common in infants and toddlers. Severe blunt or penetrating injury to the face or neck may be accompanied by swelling and an expanding hematoma, or injury to the larynx, trachea or bronchi. Airway obstruction is also common in people who have suffered smoke inhalation or burns within or near the airway or epiglottitis. Sustained generalized seizure activity and angioedema are other common causes of life-threatening airway obstruction which may require tracheal intubation to secure the airway.[1]

Manipulation of the airway

[edit]Diagnostic or therapeutic manipulation of the airway (such as bronchoscopy, laser therapy or stenting of the bronchi) may intermittently interfere with the ability to breathe; intubation may be necessary in such situations.[4]

Newborns

[edit]Syndromes such as respiratory distress syndrome, congenital heart disease, pneumothorax, and shock may lead to breathing problems in newborn infants that require endotracheal intubation and mechanically assisted breathing (mechanical ventilation).[7] Newborn infants may also require endotracheal intubation during surgery while under general anaesthesia.[7]

Equipment

[edit]Laryngoscopes

[edit]

The vast majority of tracheal intubations involve the use of a viewing instrument of one type or another. The modern conventional laryngoscope consists of a handle containing batteries that power a light and a set of interchangeable blades, which are either straight or curved. This device is designed to allow the laryngoscopist to directly view the larynx. Due to the widespread availability of such devices, the technique of blind intubation[8] of the trachea is rarely practiced today, although it may still be useful in certain emergency situations, such as natural or man-made disasters.[9] In the prehospital emergency setting, digital intubation may be necessitated if the patient is in a position that makes direct laryngoscopy impossible. For example, digital intubation may be used by a paramedic if the patient is entrapped in an inverted position in a vehicle after a motor vehicle collision with a prolonged extrication time.

The decision to use a straight or curved laryngoscope blade depends partly on the specific anatomical features of the airway, and partly on the personal experience and preference of the laryngoscopist. The Miller blade, characterized by its straight, elongated shape with a curved tip, is frequently employed in patients with challenging airway anatomy, such as those with limited mouth opening or a high larynx. Its design allows for direct visualization of the epiglottis, facilitating precise glottic exposure.[10] Conversely, the Macintosh blade, with its curved configuration reminiscent of the letters "C" or "J," is favored in routine intubations for patients with normal airway anatomy. Its curved design enables indirect laryngoscopy, providing enhanced visualization of the vocal cords and glottis in most adult patients.[11]

The choice between the Miller and Macintosh blades is influenced by specific anatomical considerations and the preferences of the laryngoscopist. While the Macintosh blade is the most commonly utilized curved laryngoscope blade, the Miller blade is the preferred option for straight blade intubation. Both blades are available in various sizes, ranging from size 0 (infant) to size 4 (large adult), catering to patients of different ages and anatomies. Additionally, there exists a myriad of specialty blades with unique features, including mirrors for enhanced visualization and ports for oxygen administration, primarily utilized by anesthetists and otolaryngologists in operating room settings.[12][10]

Fiberoptic laryngoscopes have become increasingly available since the 1990s. In contrast to the conventional laryngoscope, these devices allow the laryngoscopist to indirectly view the larynx. This provides a significant advantage in situations where the operator needs to see around an acute bend in order to visualize the glottis, and deal with otherwise difficult intubations. Video laryngoscopes are specialized fiberoptic laryngoscopes that use a digital video camera sensor to allow the operator to view the glottis and larynx on a video monitor.[13][14] Other "noninvasive" devices which can be employed to assist in tracheal intubation are the laryngeal mask airway[15] (used as a conduit for endotracheal tube placement) and the Airtraq.[16]

Stylets

[edit]

An intubating stylet is a malleable metal wire designed to be inserted into the endotracheal tube to make the tube conform better to the upper airway anatomy of the specific individual. This aid is commonly used with a difficult laryngoscopy. Just as with laryngoscope blades, there are also several types of available stylets,[17] such as the Verathon Stylet, which is specifically designed to follow the 60° blade angle of the GlideScope video laryngoscope.[18]

The Eschmann tracheal tube introducer (also referred to as a "gum elastic bougie") is specialized type of stylet used to facilitate difficult intubation.[19] This flexible device is 60 cm (24 in) in length, 15 French (5 mm diameter) with a small "hockey-stick" angle at the far end. Unlike a traditional intubating stylet, the Eschmann tracheal tube introducer is typically inserted directly into the trachea and then used as a guide over which the endotracheal tube can be passed (in a manner analogous to the Seldinger technique). As the Eschmann tracheal tube introducer is considerably less rigid than a conventional stylet, this technique is considered to be a relatively atraumatic means of tracheal intubation.[20][21]

The tracheal tube exchanger is a hollow catheter, 56 to 81 cm (22.0 to 31.9 in) in length, that can be used for removal and replacement of tracheal tubes without the need for laryngoscopy.[22] The Cook Airway Exchange Catheter (CAEC) is another example of this type of catheter; this device has a central lumen (hollow channel) through which oxygen can be administered.[23] Airway exchange catheters are long hollow catheters which often have connectors for jet ventilation, manual ventilation, or oxygen insufflation. It is also possible to connect the catheter to a capnograph to perform respiratory monitoring.

The lighted stylet is a device that employs the principle of transillumination to facilitate blind orotracheal intubation (an intubation technique in which the laryngoscopist does not view the glottis).[24]

Tracheal tubes

[edit]

A tracheal tube is a catheter that is inserted into the trachea for the primary purpose of establishing and maintaining a patent (open and unobstructed) airway. Tracheal tubes are frequently used for airway management in the settings of general anesthesia, critical care, mechanical ventilation, and emergency medicine. Many different types of tracheal tubes are available, suited for different specific applications. An endotracheal tube is a specific type of tracheal tube that is nearly always inserted through the mouth (orotracheal) or nose (nasotracheal). It is a breathing conduit designed to be placed into the airway of critically injured, ill or anesthetized patients in order to perform mechanical positive pressure ventilation of the lungs and to prevent the possibility of aspiration or airway obstruction.[25] The endotracheal tube has a fitting designed to be connected to a source of pressurized gas such as oxygen. At the other end is an orifice through which such gases are directed into the lungs and may also include a balloon (referred to as a cuff). The tip of the endotracheal tube is positioned above the carina (before the trachea divides to each lung) and sealed within the trachea so that the lungs can be ventilated equally.[25] A tracheostomy tube is another type of tracheal tube; this 50–75-millimetre-long (2.0–3.0 in) curved metal or plastic tube is inserted into a tracheostomy stoma or a cricothyrotomy incision.[26]

Tracheal tubes can be used to ensure the adequate exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, to deliver oxygen in higher concentrations than found in air, or to administer other gases such as helium,[27] nitric oxide,[28] nitrous oxide, xenon,[29] or certain volatile anesthetic agents such as desflurane, isoflurane, or sevoflurane. They may also be used as a route for administration of certain medications such as bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids, and drugs used in treating cardiac arrest such as atropine, epinephrine, lidocaine and vasopressin.[2]

Originally made from latex rubber,[30] most modern endotracheal tubes today are constructed of polyvinyl chloride. Tubes constructed of silicone rubber, wire-reinforced silicone rubber or stainless steel are also available for special applications. For human use, tubes range in size from 2 to 10.5 mm (0.1 to 0.4 in) in internal diameter. The size is chosen based on the patient's body size, with the smaller sizes being used for infants and children. Most endotracheal tubes have an inflatable cuff to seal the tracheobronchial tree against leakage of respiratory gases and pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents, blood, secretions, and other fluids. Uncuffed tubes are also available, though their use is limited mostly to children (in small children, the cricoid cartilage is the narrowest portion of the airway and usually provides an adequate seal for mechanical ventilation).[13]

In addition to cuffed or uncuffed, preformed endotracheal tubes are also available. The oral and nasal RAE tubes (named after the inventors Ring, Adair and Elwyn) are the most widely used of the preformed tubes.[31]

There are a number of different types of double-lumen endo-bronchial tubes that have endobronchial as well as endotracheal channels (Carlens, White and Robertshaw tubes). These tubes are typically coaxial, with two separate channels and two separate openings. They incorporate an endotracheal lumen which terminates in the trachea and an endobronchial lumen, the distal tip of which is positioned 1–2 cm into the right or left mainstem bronchus. There is also the Univent tube, which has a single tracheal lumen and an integrated endobronchial blocker. These tubes enable one to ventilate both lungs, or either lung independently. Single-lung ventilation (allowing the lung on the operative side to collapse) can be useful during thoracic surgery, as it can facilitate the surgeon's view and access to other relevant structures within the thoracic cavity.[32]

The "armored" endotracheal tubes are cuffed, wire-reinforced silicone rubber tubes. They are much more flexible than polyvinyl chloride tubes, yet they are difficult to compress or kink. This can make them useful for situations in which the trachea is anticipated to remain intubated for a prolonged duration, or if the neck is to remain flexed during surgery. Most armored tubes have a Magill curve, but preformed armored RAE tubes are also available. Another type of endotracheal tube has four small openings just above the inflatable cuff, which can be used for suction of the trachea or administration of intratracheal medications if necessary. Other tubes (such as the Bivona Fome-Cuf tube) are designed specifically for use in laser surgery in and around the airway.[33]

Methods to confirm tube placement

[edit]

No single method for confirming tracheal tube placement has been shown to be 100% reliable. Accordingly, the use of multiple methods for confirmation of correct tube placement is now widely considered to be the standard of care.[34] Such methods include direct visualization as the tip of the tube passes through the glottis, or indirect visualization of the tracheal tube within the trachea using a device such as a bronchoscope. With a properly positioned tracheal tube, equal bilateral breath sounds will be heard upon listening to the chest with a stethoscope, and no sound upon listening to the area over the stomach. Equal bilateral rise and fall of the chest wall will be evident with ventilatory excursions. A small amount of water vapor will also be evident within the lumen of the tube with each exhalation and there will be no gastric contents in the tracheal tube at any time.[33]

Ideally, at least one of the methods utilized for confirming tracheal tube placement will be a measuring instrument. Waveform capnography has emerged as the gold standard for the confirmation of tube placement within the trachea. Other methods relying on instruments include the use of a colorimetric end-tidal carbon dioxide detector, a self-inflating esophageal bulb, or an esophageal detection device.[35] The distal tip of a properly positioned tracheal tube will be located in the mid-trachea, roughly 2 cm (1 in) above the bifurcation of the carina; this can be confirmed by chest x-ray. If it is inserted too far into the trachea (beyond the carina), the tip of the tracheal tube is likely to be within the right main bronchus—a situation often referred to as a "right mainstem intubation". In this situation, the left lung may be unable to participate in ventilation, which can lead to decreased oxygen content due to ventilation/perfusion mismatch.[36]

Special situations

[edit]Emergencies

[edit]Tracheal intubation in the emergency setting can be difficult with the fiberoptic bronchoscope due to blood, vomit, or secretions in the airway and poor patient cooperation. Because of this, patients with massive facial injury, complete upper airway obstruction, severely diminished ventilation, or profuse upper airway bleeding are poor candidates for fiberoptic intubation.[37] Fiberoptic intubation under general anesthesia typically requires two skilled individuals.[38] Success rates of only 83–87% have been reported using fiberoptic techniques in the emergency department, with significant nasal bleeding occurring in up to 22% of patients.[39][40] These drawbacks limit the use of fiberoptic bronchoscopy somewhat in urgent and emergency situations.[41][42]

Personnel experienced in direct laryngoscopy are not always immediately available in certain settings that require emergency tracheal intubation. For this reason, specialized devices have been designed to act as bridges to a definitive airway. Such devices include the laryngeal mask airway, cuffed oropharyngeal airway and the esophageal-tracheal combitube (Combitube).[43][44] Other devices such as rigid stylets, the lightwand (a blind technique) and indirect fiberoptic rigid stylets, such as the Bullard scope, Upsher scope and the WuScope can also be used as alternatives to direct laryngoscopy. Each of these devices have its own unique set of benefits and drawbacks, and none of them is effective under all circumstances.[17]

Rapid-sequence induction and intubation

[edit]

Rapid sequence induction and intubation (RSI) is a particular method of induction of general anesthesia, commonly employed in emergency operations and other situations where patients are assumed to have a full stomach. The objective of RSI is to minimize the possibility of regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents during the induction of general anesthesia and subsequent tracheal intubation.[34] RSI traditionally involves preoxygenating the lungs with a tightly fitting oxygen mask, followed by the sequential administration of an intravenous sleep-inducing agent and a rapidly acting neuromuscular-blocking drug, such as rocuronium, succinylcholine, or cisatracurium besilate, before intubation of the trachea.[45]

One important difference between RSI and routine tracheal intubation is that the practitioner does not manually assist the ventilation of the lungs after the onset of general anesthesia and cessation of breathing, until the trachea has been intubated and the cuff has been inflated. Another key feature of RSI is the application of manual 'cricoid pressure' to the cricoid cartilage, often referred to as the "Sellick maneuver", prior to instrumentation of the airway and intubation of the trachea.[34]

Named for British anesthetist Brian Arthur Sellick (1918–1996) who first described the procedure in 1961,[46] the goal of cricoid pressure is to minimize the possibility of regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents. Cricoid pressure has been widely used during RSI for nearly fifty years, despite a lack of compelling evidence to support this practice.[47] The initial article by Sellick was based on a small sample size at a time when high tidal volumes, head-down positioning and barbiturate anesthesia were the rule.[48] Beginning around 2000, a significant body of evidence has accumulated which questions the effectiveness of cricoid pressure. The application of cricoid pressure may in fact displace the esophagus laterally[49] instead of compressing it as described by Sellick. Cricoid pressure may also compress the glottis, which can obstruct the view of the laryngoscopist and actually cause a delay in securing the airway.[50]

Cricoid pressure is often confused with the "BURP" (Backwards Upwards Rightwards Pressure) maneuver.[51] While both of these involve digital pressure to the anterior aspect (front) of the laryngeal apparatus, the purpose of the latter is to improve the view of the glottis during laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation, rather than to prevent regurgitation.[52] Both cricoid pressure and the BURP maneuver have the potential to worsen laryngoscopy.[53]

RSI may also be used in prehospital emergency situations when a patient is conscious but respiratory failure is imminent (such as in extreme trauma). This procedure is commonly performed by flight paramedics. Flight paramedics often use RSI to intubate before transport because intubation in a moving fixed-wing or rotary-wing aircraft is extremely difficult to perform due to environmental factors. The patient will be paralyzed and intubated on the ground before transport by aircraft.

Cricothyrotomy

[edit]

A cricothyrotomy is an incision made through the skin and cricothyroid membrane to establish a patent airway during certain life-threatening situations, such as airway obstruction by a foreign body, angioedema, or massive facial trauma.[54] A cricothyrotomy is nearly always performed as a last resort in cases where orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation are impossible or contraindicated. Cricothyrotomy is easier and quicker to perform than tracheotomy, does not require manipulation of the cervical spine and is associated with fewer complications.[55]

The easiest method to perform this technique is the needle cricothyrotomy (also referred to as a percutaneous dilational cricothyrotomy), in which a large-bore (12–14 gauge) intravenous catheter is used to puncture the cricothyroid membrane.[56] Oxygen can then be administered through this catheter via jet insufflation. However, while needle cricothyrotomy may be life-saving in extreme circumstances, this technique is only intended to be a temporizing measure until a definitive airway can be established.[57] While needle cricothyrotomy can provide adequate oxygenation, the small diameter of the cricothyrotomy catheter is insufficient for elimination of carbon dioxide (ventilation). After one hour of apneic oxygenation through a needle cricothyrotomy, one can expect a PaCO2 of greater than 250 mm Hg and an arterial pH of less than 6.72, despite an oxygen saturation of 98% or greater.[58] A more definitive airway can be established by performing a surgical cricothyrotomy, in which a 5 to 6 mm (0.20 to 0.24 in) endotracheal tube or tracheostomy tube can be inserted through a larger incision.[59]

Several manufacturers market prepackaged cricothyrotomy kits, which enable one to use either a wire-guided percutaneous dilational (Seldinger) technique, or the classic surgical technique to insert a polyvinylchloride catheter through the cricothyroid membrane. The kits may be stocked in hospital emergency departments and operating suites, as well as ambulances and other selected pre-hospital settings.[60]

Tracheotomy

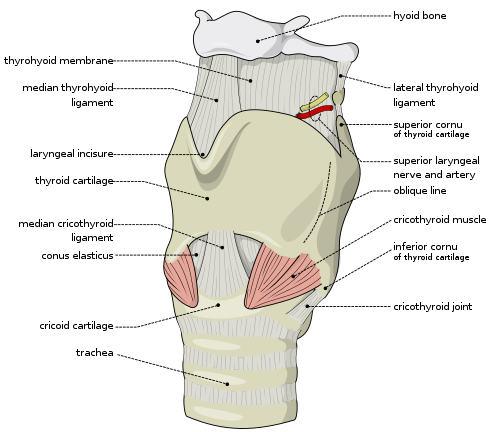

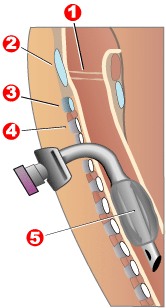

[edit]

1 - Vocal folds

2 - Thyroid cartilage

3 - Cricoid cartilage

4 - Tracheal rings

5 - Balloon cuff

Tracheotomy consists of making an incision on the front of the neck and opening a direct airway through an incision in the trachea. The resulting opening can serve independently as an airway or as a site for a tracheostomy tube to be inserted; this tube allows a person to breathe without the use of his nose or mouth. The opening may be made by a scalpel or a needle (referred to as surgical[59] and percutaneous[61] techniques respectively) and both techniques are widely used in current practice. In order to limit the risk of damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerves (the nerves that control the voice box), the tracheotomy is performed as high in the trachea as possible. If only one of these nerves is damaged, the patient's voice may be impaired (dysphonia); if both of the nerves are damaged, the patient will be unable to speak (aphonia). In the acute setting, indications for tracheotomy are similar to those for cricothyrotomy. In the chronic setting, indications for tracheotomy include the need for long-term mechanical ventilation and removal of tracheal secretions (e.g., comatose patients, or extensive surgery involving the head and neck).[62][63]

Children

[edit]

There are significant differences in airway anatomy and respiratory physiology between children and adults, and these are taken into careful consideration before performing tracheal intubation of any pediatric patient. The differences, which are quite significant in infants, gradually disappear as the human body approaches a mature age and body mass index.[64]

For infants and young children, orotracheal intubation is easier than the nasotracheal route. Nasotracheal intubation carries a risk of dislodgement of adenoids and nasal bleeding. Despite the greater difficulty, nasotracheal intubation route is preferable to orotracheal intubation in children undergoing intensive care and requiring prolonged intubation because this route allows a more secure fixation of the tube. As with adults, there are a number of devices specially designed for assistance with difficult tracheal intubation in children.[65][66][67][68] Confirmation of proper position of the tracheal tube is accomplished as with adult patients.[69]

Because the airway of a child is narrow, a small amount of glottic or tracheal swelling can produce critical obstruction. Inserting a tube that is too large relative to the diameter of the trachea can cause swelling. Conversely, inserting a tube that is too small can result in inability to achieve effective positive pressure ventilation due to retrograde escape of gas through the glottis and out the mouth and nose (often referred to as a "leak" around the tube). An excessive leak can usually be corrected by inserting a larger tube or a cuffed tube.[70]

The tip of a correctly positioned tracheal tube will be in the mid-trachea, between the collarbones on an anteroposterior chest radiograph. The correct diameter of the tube is that which results in a small leak at a pressure of about 25 cm (10 in) of water. The appropriate inner diameter for the endotracheal tube is estimated to be roughly the same diameter as the child's little finger. The appropriate length for the endotracheal tube can be estimated by doubling the distance from the corner of the child's mouth to the ear canal. For premature infants 2.5 mm (0.1 in) internal diameter is an appropriate size for the tracheal tube. For infants of normal gestational age, 3 mm (0.12 in) internal diameter is an appropriate size. For normally nourished children 1 year of age and older, two formulae are used to estimate the appropriate diameter and depth for tracheal intubation. The internal diameter of the tube in mm is (patient's age in years + 16) / 4, while the appropriate depth of insertion in cm is 12 + (patient's age in years / 2).[33]

Newborn infants

[edit]Endotrachael suctioning is often used during intubation in newborn infants to reduce the risk of a blocked tube due to secretions, a collapsed lung, and to reduce pain.[7] Suctioning is sometimes used at specifically scheduled intervals, "as needed", and less frequently. Further research is necessary to determine the most effective suctioning schedule or frequency of suctioning in intubated infants.[7]

In newborns free flow oxygen used to be recommended during intubation however as there is no evidence of benefit the 2011 NRP guidelines no longer do.[71]

Predicting difficulty

[edit]

Tracheal intubation is not a simple procedure and the consequences of failure are grave. Therefore, the patient is carefully evaluated for potential difficulty or complications beforehand. This involves taking the medical history of the patient and performing a physical examination, the results of which can be scored against one of several classification systems. The proposed surgical procedure (e.g., surgery involving the head and neck, or bariatric surgery) may lead one to anticipate difficulties with intubation.[34] Many individuals have unusual airway anatomy, such as those who have limited movement of their neck or jaw, or those who have tumors, deep swelling due to injury or to allergy, developmental abnormalities of the jaw, or excess fatty tissue of the face and neck. Using conventional laryngoscopic techniques, intubation of the trachea can be difficult or even impossible in such patients. This is why all persons performing tracheal intubation must be familiar with alternative techniques of securing the airway. Use of the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope and similar devices has become among the preferred techniques in the management of such cases. However, these devices require a different skill set than that employed for conventional laryngoscopy and are expensive to purchase, maintain and repair.[72]

When taking the patient's medical history, the subject is questioned about any significant signs or symptoms, such as difficulty in speaking or difficulty in breathing. These may suggest obstructing lesions in various locations within the upper airway, larynx, or tracheobronchial tree. A history of previous surgery (e.g., previous cervical fusion), injury, radiation therapy, or tumors involving the head, neck and upper chest can also provide clues to a potentially difficult intubation. Previous experiences with tracheal intubation, especially difficult intubation, intubation for prolonged duration (e.g., intensive care unit) or prior tracheotomy are also noted.[34]

A detailed physical examination of the airway is important, particularly:[73]

- the range of motion of the cervical spine: the subject should be able to tilt the head back and then forward so that the chin touches the chest.

- the range of motion of the jaw (the temporomandibular joint): three of the subject's fingers should be able to fit between the upper and lower incisors.

- the size and shape of the upper jaw and lower jaw, looking especially for problems such as maxillary hypoplasia (an underdeveloped upper jaw), micrognathia (an abnormally small jaw), or retrognathia (misalignment of the upper and lower jaw).

- the thyromental distance: three of the subject's fingers should be able to fit between the Adam's apple and the chin.

- the size and shape of the tongue and palate relative to the size of the mouth.

- the teeth, especially noting the presence of prominent maxillary incisors, any loose or damaged teeth, or crowns.

Many classification systems have been developed in an effort to predict difficulty of tracheal intubation, including the Cormack-Lehane classification system,[74] the Intubation Difficulty Scale (IDS),[75] and the Mallampati score.[76] The Mallampati score is drawn from the observation that the size of the base of the tongue influences the difficulty of intubation. It is determined by looking at the anatomy of the mouth, and in particular the visibility of the base of palatine uvula, faucial pillars and the soft palate. Although such medical scoring systems may aid in the evaluation of patients, no single score or combination of scores can be trusted to specifically detect all and only those patients who are difficult to intubate.[77][78] Furthermore, one study of experienced anesthesiologists, on the widely used Cormack–Lehane classification system, found they did not score the same patients consistently over time, and that only 25% could correctly define all four grades of the widely used Cormack–Lehane classification system.[79] Under certain emergency circumstances (e.g., severe head trauma or suspected cervical spine injury), it may be impossible to fully utilize these the physical examination and the various classification systems to predict the difficulty of tracheal intubation.[80] A Cochrane systematic review examined the sensitivity and specificity of various bedside tests commonly used for predicting difficulty in airway management.[81] In such cases, alternative techniques of securing the airway must be readily available.[82]

Complications

[edit]Tracheal intubation is generally considered the best method for airway management under a wide variety of circumstances, as it provides the most reliable means of oxygenation and ventilation and the greatest degree of protection against regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration.[2] However, tracheal intubation requires a great deal of clinical experience to master[83] and serious complications may result even when properly performed.[84]

Four anatomic features must be present for orotracheal intubation to be straightforward: adequate mouth opening (full range of motion of the temporomandibular joint), sufficient pharyngeal space (determined by examining the back of the mouth), sufficient submandibular space (distance between the thyroid cartilage and the chin, the space into which the tongue must be displaced in order for the larygoscopist to view the glottis), and adequate extension of the cervical spine at the atlanto-occipital joint. If any of these variables is in any way compromised, intubation should be expected to be difficult.[84]

Minor complications are common after laryngoscopy and insertion of an orotracheal tube. These are typically of short duration, such as sore throat, lacerations of the lips or gums or other structures within the upper airway, chipped, fractured or dislodged teeth, and nasal injury. Other complications which are common but potentially more serious include accelerated or irregular heartbeat, high blood pressure, elevated intracranial and introcular pressure, and bronchospasm.[84]

More serious complications include laryngospasm, perforation of the trachea or esophagus, pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents or other foreign bodies, fracture or dislocation of the cervical spine, temporomandibular joint or arytenoid cartilages, decreased oxygen content, elevated arterial carbon dioxide, and vocal cord weakness.[84] In addition to these complications, tracheal intubation via the nasal route carries a risk of dislodgement of adenoids and potentially severe nasal bleeding.[39][40] Newer technologies such as flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy have fared better in reducing the incidence of some of these complications, though the most frequent cause of intubation trauma remains a lack of skill on the part of the laryngoscopist.[84]

Complications may also be severe and long-lasting or permanent, such as vocal cord damage, esophageal perforation and retropharyngeal abscess, bronchial intubation, or nerve injury. They may even be immediately life-threatening, such as laryngospasm and negative pressure pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs), aspiration, unrecognized esophageal intubation, or accidental disconnection or dislodgement of the tracheal tube.[84] Potentially fatal complications more often associated with prolonged intubation or tracheotomy include abnormal communication between the trachea and nearby structures such as the innominate artery (tracheoinnominate fistula) or esophagus (tracheoesophageal fistula). Other significant complications include airway obstruction due to loss of tracheal rigidity, ventilator-associated pneumonia and narrowing of the glottis or trachea.[33] The cuff pressure is monitored carefully in order to avoid complications from over-inflation, many of which can be traced to excessive cuff pressure restricting the blood supply to the tracheal mucosa.[85][86] A 2000 Spanish study of bedside percutaneous tracheotomy reported overall complication rates of 10–15% and procedural mortality of 0%,[61] which is comparable to those of other series reported in the literature from the Netherlands[87] and the United States.[88]

Inability to secure the airway, with subsequent failure of oxygenation and ventilation is a life-threatening complication which if not immediately corrected leads to decreased oxygen content, brain damage, cardiovascular collapse, and death.[84] When performed improperly, the associated complications (e.g., unrecognized esophageal intubation) may be rapidly fatal.[89] Without adequate training and experience, the incidence of such complications is high.[2] The case of Andrew Davis Hughes, from Emerald Isle, NC is a widely known case in which the patient was improperly intubated and, due to the lack of oxygen, sustained severe brain damage and died. For example, among paramedics in several United States urban communities, unrecognized esophageal or hypopharyngeal intubation has been reported to be 6%[90][91] to 25%.[89] Although not common, where basic emergency medical technicians are permitted to intubate, reported success rates are as low as 51%.[92] In one study, nearly half of patients with misplaced tracheal tubes died in the emergency room.[89] Because of this, the American Heart Association's Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation have de-emphasized the role of tracheal intubation in favor of other airway management techniques such as bag-valve-mask ventilation, the laryngeal mask airway and the Combitube.[2] Higher quality studies demonstrate favorable evidence for this shift, as they have shown no survival or neurological benefit with endotracheal intubation over supraglottic airway devices (Laryngeal mask or Combitube).[93]

One complication—unintentional and unrecognized intubation of the esophagus—is both common (as frequent as 25% in the hands of inexperienced personnel)[89] and likely to result in a deleterious or even fatal outcome. In such cases, oxygen is inadvertently administered to the stomach, from where it cannot be taken up by the circulatory system, instead of the lungs. If this situation is not immediately identified and corrected, death will ensue from cerebral and cardiac anoxia.

Of 4,460 claims in the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Closed Claims Project database, 266 (approximately 6%) were for airway injury. Of these 266 cases, 87% of the injuries were temporary, 5% were permanent or disabling, and 8% resulted in death. Difficult intubation, age older than 60 years, and female gender were associated with claims for perforation of the esophagus or pharynx. Early signs of perforation were present in only 51% of perforation claims, whereas late sequelae occurred in 65%.[94]

During the SARS and COVID-19 pandemics, tracheal intubation has been used with a ventilator in severe cases where the patient struggles to breathe. Performing the procedure carries a risk of the caregiver becoming infected.[95][96][97]

Alternatives

[edit]Although it offers the greatest degree of protection against regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration, tracheal intubation is not the only means to maintain a patent airway. Alternative techniques for airway management and delivery of oxygen, volatile anesthetics or other breathing gases include the laryngeal mask airway, i-gel, cuffed oropharyngeal airway, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP mask), nasal BiPAP mask, simple face mask, and nasal cannula.[98]

General anesthesia is often administered without tracheal intubation in selected cases where the procedure is brief in duration, or procedures where the depth of anesthesia is not sufficient to cause significant compromise in ventilatory function. Even for longer duration or more invasive procedures, a general anesthetic may be administered without intubating the trachea, provided that patients are carefully selected, and the risk-benefit ratio is favorable (i.e., the risks associated with an unprotected airway are believed to be less than the risks of intubating the trachea).[98]

Airway management can be classified into closed or open techniques depending on the system of ventilation used. Tracheal intubation is a typical example of a closed technique as ventilation occurs using a closed circuit. Several open techniques exist, such as spontaneous ventilation, apnoeic ventilation or jet ventilation. Each has its own specific advantages and disadvantages which determine when it should be used.

Spontaneous ventilation has been traditionally performed with an inhalational agent (i.e. gas induction or inhalational induction using halothane or sevoflurane) however it can also be performed using intravenous anaesthesia (e.g. propofol, ketamine or dexmedetomidine). SponTaneous Respiration using IntraVEnous anaesthesia and High-flow nasal oxygen (STRIVE Hi) is an open airway technique that uses an upwards titration of propofol which maintains ventilation at deep levels of anaesthesia. It has been used in airway surgery as an alternative to tracheal intubation.[99]

History

[edit]- Tracheotomy

The earliest known depiction of a tracheotomy is found on two Egyptian tablets dating back to around 3600 BC.[100] The 110-page Ebers Papyrus, an Egyptian medical papyrus which dates to roughly 1550 BC, also makes reference to the tracheotomy.[101] Tracheotomy was described in the Rigveda, a Sanskrit text of ayurvedic medicine written around 2000 BC in ancient India.[102] The Sushruta Samhita from around 400 BC is another text from the Indian subcontinent on ayurvedic medicine and surgery that mentions tracheotomy.[103] Asclepiades of Bithynia (c. 124–40 BC) is often credited as being the first physician to perform a non-emergency tracheotomy.[104] Galen of Pergamon (AD 129–199) clarified the anatomy of the trachea and was the first to demonstrate that the larynx generates the voice.[105] In one of his experiments, Galen used bellows to inflate the lungs of a dead animal.[106] Ibn Sīnā (980–1037) described the use of tracheal intubation to facilitate breathing in 1025 in his 14-volume medical encyclopedia, The Canon of Medicine.[107] In the 12th century medical textbook Al-Taisir, Ibn Zuhr (1092–1162)—also known as Avenzoar—of Al-Andalus provided a correct description of the tracheotomy operation.[108]

The first detailed descriptions of tracheal intubation and subsequent artificial respiration of animals were from Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) of Brussels. In his landmark book published in 1543, De humani corporis fabrica, he described an experiment in which he passed a reed into the trachea of a dying animal whose thorax had been opened and maintained ventilation by blowing into the reed intermittently.[106] Antonio Musa Brassavola (1490–1554) of Ferrara successfully treated a patient with peritonsillar abscess by tracheotomy. Brassavola published his account in 1546; this operation has been identified as the first recorded successful tracheotomy, despite the many previous references to this operation.[109] Towards the end of the 16th century, Hieronymus Fabricius (1533–1619) described a useful technique for tracheotomy in his writings, although he had never actually performed the operation himself. In 1620 the French surgeon Nicholas Habicot (1550–1624) published a report of four successful tracheotomies.[110] In 1714, anatomist Georg Detharding (1671–1747) of the University of Rostock performed a tracheotomy on a drowning victim.[111]

Despite the many recorded instances of its use since antiquity, it was not until the early 19th century that the tracheotomy finally began to be recognized as a legitimate means of treating severe airway obstruction. In 1852, French physician Armand Trousseau (1801–1867) presented a series of 169 tracheotomies to the Académie Impériale de Médecine. 158 of these were performed for the treatment of croup, and 11 were performed for "chronic maladies of the larynx".[112] Between 1830 and 1855, more than 350 tracheotomies were performed in Paris, most of them at the Hôpital des Enfants Malades, a public hospital, with an overall survival rate of only 20–25%. This compares with 58% of the 24 patients in Trousseau's private practice, who fared better due to greater postoperative care.[113]

In 1871, the German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg (1844–1924) published a paper describing the first successful elective human tracheotomy to be performed for the purpose of administration of general anesthesia.[114] In 1888, Sir Morell Mackenzie (1837–1892) published a book discussing the indications for tracheotomy.[115] In the early 20th century, tracheotomy became a life-saving treatment for patients affected with paralytic poliomyelitis who required mechanical ventilation. In 1909, Philadelphia laryngologist Chevalier Jackson (1865–1958) described a technique for tracheotomy that is used to this day.[116]

- Laryngoscopy and non-surgical techniques

In 1854, a Spanish singing teacher named Manuel García (1805–1906) became the first man to view the functioning glottis in a living human.[117] In 1858, French pediatrician Eugène Bouchut (1818–1891) developed a new technique for non-surgical orotracheal intubation to bypass laryngeal obstruction resulting from a diphtheria-related pseudomembrane.[118] In 1880, Scottish surgeon William Macewen (1848–1924) reported on his use of orotracheal intubation as an alternative to tracheotomy to allow a patient with glottic edema to breathe, as well as in the setting of general anesthesia with chloroform.[119] In 1895, Alfred Kirstein (1863–1922) of Berlin first described direct visualization of the vocal cords, using an esophagoscope he had modified for this purpose; he called this device an autoscope.[120]

In 1913, Chevalier Jackson was the first to report a high rate of success for the use of direct laryngoscopy as a means to intubate the trachea.[121] Jackson introduced a new laryngoscope blade that incorporated a component that the operator could slide out to allow room for passage of an endotracheal tube or bronchoscope.[122] Also in 1913, New York surgeon Henry H. Janeway (1873–1921) published results he had achieved using a laryngoscope he had recently developed.[123] Another pioneer in this field was Sir Ivan Whiteside Magill (1888–1986), who developed the technique of awake blind nasotracheal intubation,[124][125] the Magill forceps,[126] the Magill laryngoscope blade,[127] and several apparati for the administration of volatile anesthetic agents.[128][129][130] The Magill curve of an endotracheal tube is also named for Magill. Sir Robert Macintosh (1897–1989) introduced a curved laryngoscope blade in 1943;[131] the Macintosh blade remains to this day the most widely used laryngoscope blade for orotracheal intubation.[10]

Between 1945 and 1952, optical engineers built upon the earlier work of Rudolph Schindler (1888–1968), developing the first gastrocamera.[132] In 1964, optical fiber technology was applied to one of these early gastrocameras to produce the first flexible fiberoptic endoscope.[133] Initially used in upper GI endoscopy, this device was first used for laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation by Peter Murphy, an English anesthetist, in 1967.[134] The concept of using a stylet for replacing or exchanging orotracheal tubes was introduced by Finucane and Kupshik in 1978, using a central venous catheter.[135]

By the mid-1980s, the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope had become an indispensable instrument within the pulmonology and anesthesia communities.[13] The digital revolution of the 21st century has brought newer technology to the art and science of tracheal intubation. Several manufacturers have developed video laryngoscopes which employ digital technology such as the CMOS active pixel sensor (CMOS APS) to generate a view of the glottis so that the trachea may be intubated.[32]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Benumof (2007), Ezri T and Warters RD, Chapter 15: Indications for tracheal intubation, pp. 371–8

- ^ a b c d e International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation, American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council (2005). "2005 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Part 4: Advanced life support". Resuscitation. 67 (2–3): 213–47. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.09.018. PMID 16324990.

- ^ Advanced Trauma Life Support Program for Doctors (2004), Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons, Head Trauma, pp. 151–76

- ^ a b Kabrhel, C; Thomsen, TW; Setnik, GS; Walls, RM (2007). "Videos in clinical medicine: orotracheal intubation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (17): e15. doi:10.1056/NEJMvcm063574. PMID 17460222.

- ^ Mallinson, Tom; Worrall, Mark; Price, Richard; Duff, Lorna (2022). "Prehospital endotracheal intubation in cardiac arrest by BASICS Scotland clinicians". doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.24988.56969.

- ^ Doherty (2010), Holcroft JW, Anderson JT and Sena MJ, Shock & Acute Pulmonary Failure in Surgical Patients, pp. 151–75

- ^ a b c d Bruschettini, Matteo; Zappettini, Simona; Moja, Lorenzo; Calevo, Maria Grazia (2016-03-07). "Frequency of endotracheal suctioning for the prevention of respiratory morbidity in ventilated newborns". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (5) CD011493. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011493.pub2. hdl:2434/442812. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8915721. PMID 26945780.

- ^ James, NR (1950). "Blind Intubation". Anaesthesia. 5 (3): 159–60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1950.tb12674.x. S2CID 221389855.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Christodolou CC, Murphy MF and Hung OR, Chapter 17: Blind digital intubation, pp. 393–8

- ^ a b c Scott, J; Baker, PA (2009). "How did the Macintosh laryngoscope become so popular?". Pediatric Anesthesia. 19 (Suppl 1): 24–9. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03026.x. PMID 19572841. S2CID 6345531.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Berry JM, Chapter 16: Conventional (laryngoscopic) orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation (single lumen tube), pp. 379–92

- ^ Barash, Paul G.; Cullen, Bruce F.; Stoelting, Robert K.; Cahalan, Michael K.; Stock, M. Christine; Ortega, Rafael; Sharar, Sam R.; Holt, Natalie F., eds. (2017). Clinical anesthesia (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia Baltimore New York London Buenos Aires: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4963-3700-9.

- ^ a b c Benumof (2007), Wheeler M and Ovassapian A, Chapter 18: Fiberoptic endoscopy-aided technique, p. 399-438

- ^ Hansel J, Rogers AM, Lewis SR, Cook TM, Smith AF (April 2022). "Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adults undergoing tracheal intubation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 (4) CD011136. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011136.pub3. PMC 8978307. PMID 35373840.

- ^ Brain, AIJ (1985). "Three cases of difficult intubation overcome by the laryngeal mask airway". Anaesthesia. 40 (4): 353–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1985.tb10788.x. PMID 3890603. S2CID 35038041.

- ^ Maharaj, CH; Costello, JF; McDonnell, JG; Harte, BH; Laffey, JG (2007). "The Airtraq as a rescue airway device following failed direct laryngoscopy: a case series". Anaesthesia. 62 (6): 598–601. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05036.x. PMID 17506739. S2CID 21106547.

- ^ a b Benumof (2007), Hung OR and Stewart RD, Chapter 20: Intubating stylets, pp. 463–75

- ^ Agrò, F; Barzoi, G; Montecchia, F (2003). "Tracheal intubation using a Macintosh laryngoscope or a GlideScope in 15 patients with cervical spine immobilization". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 90 (5): 705–6. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg560. PMID 12697606.

- ^ El-Orbany, MI; Salem, MR (2004). "The Eschmann tracheal tube introducer is not an airway exchange device". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 99 (4): 1269–70, author reply 1270. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000133955.92363.B1. PMID 15385401.

- ^ Armstrong, P; Sellers, WF (2004). "A response to 'Bougie trauma—it is still possible', Prabhu A, Pradham P, Sanaka R and Bilolikar A, Anaesthesia 2003; 58: 811–2". Anaesthesia. 59 (2): 204. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2003.03632.x. PMID 14725554. S2CID 7977609.

- ^ Hodzovic, I; Latto, IP; Wilkes, AR; Hall, JE; Mapleson, WW (2004). "Evaluation of Frova, single-use intubation introducer, in a manikin. Comparison with Eschmann multiple-use introducer and Portex single-use introducer". Anaesthesia. 59 (8): 811–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03809.x. PMID 15270974. S2CID 13037753.

- ^ "Sheridan endotracheal tubes catalog" (PDF). Hudson RCI. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-09. Retrieved 2010-07-25.

- ^ Loudermilk EP, Hartmannsgruber M, Stoltzfus DP, Langevin PB (June 1997). "A prospective study of the safety of tracheal extubation using a pediatric airway exchange catheter for patients with a known difficult airway". Chest. 111 (6): 1660–5. doi:10.1378/chest.111.6.1660. PMID 9187190. S2CID 18358131.

- ^ Davis, L; Cook-Sather, SD; Schreiner, MS (2000). "Lighted stylet tracheal intubation: a review" (PDF). Anesthesia & Analgesia. 90 (3): 745–56. doi:10.1097/00000539-200003000-00044. PMID 10702469. S2CID 26644781.

- ^ a b US patent 5329940, Adair, Edwin L., "Endotracheal tube intubation assist device", published 1994-07-19, issued July 19, 1994

- ^ "Tracheostomy tube". Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02.

- ^ Tobias, JD (2009). "Helium insufflation with sevoflurane general anesthesia and spontaneous ventilation during airway surgery". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 56 (3): 243–6. doi:10.1007/s12630-008-9034-1. PMID 19247745.

- ^ Chotigeat, U; Khorana, M; Kanjanapattanakul, W (2007). "Inhaled nitric oxide in newborns with severe hypoxic respiratory failure" (PDF). Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 90 (2): 266–71. PMID 17375630. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- ^ Goto T, Nakata Y, Morita S (January 2003). "Will xenon be a stranger or a friend?: the cost, benefit, and future of xenon anesthesia". Anesthesiology. 98 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1097/00000542-200301000-00002. PMID 12502969. S2CID 19119058.

- ^ Macewen, W (1880). "Clinical observations on the introduction of tracheal tubes by the mouth instead of performing tracheotomy or laryngotomy". British Medical Journal. 2 (1022): 163–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1022.163. PMC 2241109. PMID 20749636.

- ^ Ring, WH; Adair, JC; Elwyn, RA (1975). "A new pediatric endotracheal tube". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 54 (2): 273–4. doi:10.1213/00000539-197503000-00030. PMID 1168437.

- ^ a b Benumof (2007), Sheinbaum R, Hammer GB, Benumof JL, Chapter 24: Separation of the two lungs, pp. 576–93

- ^ a b c d Barash, Cullen and Stoelting (2009), Rosenblatt WH. and Sukhupragarn W, Management of the airway, pp. 751–92

- ^ a b c d e Miller (2000), Stone DJ and Gal TJ, Airway management, pp. 1414–51

- ^ Wolfe, T (1998). "The Esophageal Detector Device: Summary of the current articles in the literature". Salt Lake City, Utah: Wolfe Tory Medical. Archived from the original on 2006-11-14. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Salem MR and Baraka A, Chapter 30: Confirmation of tracheal intubation, pp. 697–730

- ^ Morris, IR (1994). "Fibreoptic intubation". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 41 (10): 996–1007, discussion 1007–8. doi:10.1007/BF03010944. PMID 8001220.

- ^ Ovassapian, A (1991). "Fiberoptic-assisted management of the airway". ASA Annual Refresher Course Lectures. 19 (1): 101–16. doi:10.1097/00126869-199119000-00009.

- ^ a b Delaney, KA; Hessler, R (1988). "Emergency flexible fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation: a report of 60 cases". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 17 (9): 919–26. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(88)80672-3. PMID 3415064.

- ^ a b Mlinek, EJ Jr; Clinton, JE; Plummer, D; Ruiz, E (1990). "Fiberoptic intubation in the emergency department". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 19 (4): 359–62. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)82333-9. PMID 2321818.

- ^ American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on the management of the difficult airway (2003). "Practice guidelines for the management of the difficult airway: an updated report". Anesthesiology. 98 (5): 1269–77. doi:10.1097/00000542-200305000-00032. PMID 12717151. S2CID 39762822.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Hagberg CA and Benumof JL, Chapter 9: The American Society of Anesthesiologists' management of the difficult airway algorithm and explanation-analysis of the algorithm, pp. 236–54

- ^ Foley, LJ; Ochroch, EA (2000). "Bridges to establish an emergency airway and alternate intubating techniques". Critical Care Clinics. 16 (3): 429–44, vi. doi:10.1016/S0749-0704(05)70121-4. PMID 10941582.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Frass M, Urtubia RM and Hagberg CA, Chapter 25: The Combitube: esophageal-tracheal double-lumen airway, pp. 594–615

- ^ Benumof (2007), Suresh MS, Munnur U and Wali A, Chapter 32: The patient with a full stomach, pp. 752–82

- ^ Sellick, BA (1961). "Cricoid pressure to control regurgitation of stomach contents during induction of anaesthesia". The Lancet. 278 (7199): 404–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)92485-0. PMID 13749923.

- ^ Salem, MR; Sellick, BA; Elam, JO (1974). "The historical background of cricoid pressure in anesthesia and resuscitation". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 53 (2): 230–2. doi:10.1213/00000539-197403000-00011. PMID 4593092.

- ^ Maltby, JR; Beriault, MT (2002). "Science, pseudoscience and Sellick". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 49 (5): 443–7. doi:10.1007/BF03017917. PMID 11983655.

- ^ Smith KJ, Dobranowski J, Yip G, Dauphin A, Choi PT (July 2003). "Cricoid pressure displaces the esophagus: an observational study using magnetic resonance imaging". Anesthesiology. 99 (1): 60–4. doi:10.1097/00000542-200307000-00013. PMID 12826843. S2CID 18535821.

- ^ Haslam, N; Parker, L; Duggan, JE (2005). "Effect of cricoid pressure on the view at laryngoscopy". Anaesthesia. 60 (1): 41–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04010.x. PMID 15601271. S2CID 42387260.

- ^ Knill, RL (1993). "Difficult laryngoscopy made easy with a "BURP"". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 40 (3): 279–82. doi:10.1007/BF03037041. PMID 8467551.

- ^ Takahata, O; Kubota, M; Mamiya, K; Akama, Y; Nozaka, T; Matsumoto, H; Ogawa, H (1997). "The efficacy of the "BURP" maneuver during a difficult laryngoscopy". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 84 (2): 419–21. doi:10.1097/00000539-199702000-00033. PMID 9024040. S2CID 16579238.

- ^ Levitan RM, Kinkle WC, Levin WJ, Everett WW (June 2006). "Laryngeal view during laryngoscopy: a randomized trial comparing cricoid pressure, backward-upward-rightward pressure, and bimanual laryngoscopy". Ann Emerg Med. 47 (6): 548–55. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.013. PMID 16713784.

- ^ Mohan, R; Iyer, R; Thaller, S (2009). "Airway management in patients with facial trauma". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 20 (1): 21–3. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e318190327a. PMID 19164982. S2CID 5459569.

- ^ Katos, MG; Goldenberg, D (2007). "Emergency cricothyrotomy". Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology. 18 (2): 110–4. doi:10.1016/j.otot.2007.05.002.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Melker RJ and Kost KM, Chapter 28: Percutaneous dilational cricothyrotomy and tracheostomy, pp. 640–77

- ^ Advanced Trauma Life Support Program for Doctors (2004), Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons, Airway and Ventilatory Management, pp. 41–68

- ^ Frumin, MJ; Epstein, RM; Cohen, G (1959). "Apneic oxygenation in man". Anesthesiology. 20 (6): 789–98. doi:10.1097/00000542-195911000-00007. PMID 13825447. S2CID 33528267.

- ^ a b Benumof (2007), Gibbs MA and Walls RM, Chapter 29: Surgical airway, pp. 678–96

- ^ Benkhadra, M; Lenfant, F; Nemetz, W; Anderhuber, F; Feigl, G; Fasel, J (2008). "A comparison of two emergency cricothyroidotomy kits in human cadavers" (PDF). Anesthesia & Analgesia. 106 (1): 182–5. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000296457.55791.34. PMID 18165576. S2CID 24568104.

- ^ a b Añón, JM; Gómez, V; Escuela, MP; De Paz, V; Solana, LF; De La Casa, RM; Pérez, JC; Zeballos, Eugenio; Navarro, Luis (2000). "Percutaneous tracheostomy: comparison of Ciaglia and Griggs techniques". Critical Care. 4 (2): 124–8. doi:10.1186/cc667. PMC 29040. PMID 11056749.

- ^ Heffner JE (July 1989). "Medical indications for tracheotomy". Chest. 96 (1): 186–90. doi:10.1378/chest.96.1.186. PMID 2661159.

- ^ Lee, W; Koltai, P; Harrison, AM; Appachi, E; Bourdakos, D; Davis, S; Weise, K; McHugh, M; Connor, J (2002). "Indications for tracheotomy in the pediatric intensive care unit population: a pilot study". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 128 (11): 1249–52. doi:10.1001/archotol.128.11.1249. PMID 12431164. S2CID 20209753.

- ^ Barash, Cullen and Stoelting (2009), Cravero JP and Cain ZN, Pediatric anesthesia, pp. 1206–20

- ^ Borland, LM; Casselbrant, M (1990). "The Bullard laryngoscope. A new indirect oral laryngoscope (pediatric version)". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 70 (1): 105–8. doi:10.1213/00000539-199001000-00019. PMID 2297088.

- ^ Theroux, MC; Kettrick, RG; Khine, H (1995). "Laryngeal mask airway and fiberoptic endoscopy in an infant with Schwartz-Jampel syndrome". Anesthesiology. 82 (2): 605. doi:10.1097/00000542-199502000-00044. PMID 7856930.

- ^ Kim, JE; Chang, CH; Nam, YT (2008). "Intubation through a Laryngeal Mask Airway by Fiberoptic Bronchoscope in an Infant with a Mass at the Base of the Tongue" (PDF). Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. 54 (3): S43–6. doi:10.4097/kjae.2008.54.3.S43.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hackell, R; Held, LD; Stricker, PA; Fiadjoe, JE (2009). "Management of the difficult infant airway with the Storz Video Laryngoscope: a case series". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 109 (3): 763–6. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ad8a05. PMID 19690244.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Rabb MF and Szmuk P, Chapter 33: The difficult pediatric airway, pp. 783–833

- ^ Sheridan, RL (2006). "Uncuffed endotracheal tubes should not be used in seriously burned children". Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 7 (3): 258–9. doi:10.1097/01.PCC.0000216681.71594.04. PMID 16575345. S2CID 24736705.

- ^ Zaichkin, J; Weiner, GM (February 2011). "Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) 2011: new science, new strategies". Advances in Neonatal Care. 11 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1097/ANC.0b013e31820e429f. PMID 21285656.

- ^ Rozman, A; Duh, S; Petrinec-Primozic, M; Triller, N (2009). "Flexible bronchoscope damage and repair costs in a bronchoscopy teaching unit". Respiration. 77 (3): 325–30. doi:10.1159/000188788. PMID 19122449. S2CID 5827594.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Reed AP, Chapter 8: Evaluation and recognition of the difficult airway, pp. 221–35

- ^ Zadrobilek, E (2009). "The Cormack-Lehane classification: twenty-fifth anniversary of the first published description". Internet Journal of Airway Management. 5.

- ^ Adnet, F; Borron, SW; Racine, SX; Clemessy, JL; Fournier, JL; Plaisance, P; Lapandry, C (1997). "The intubation difficulty scale (IDS): proposal and evaluation of a new score characterizing the complexity of endotracheal intubation". Anesthesiology. 87 (6): 1290–7. doi:10.1097/00000542-199712000-00005. PMID 9416711. S2CID 10561049.

- ^ Mallampati, SR; Gatt, SP; Gugino, LD; Desai, SP; Waraksa, B; Freiberger, D; Liu, PL (1985). "A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study". Canadian Anaesthetists' Society Journal. 32 (4): 429–34. doi:10.1007/BF03011357. PMID 4027773.

- ^ Shiga, T; Wajima, Z; Inoue, T; Sakamoto, A (2005). "Predicting difficult intubation in apparently normal patients: a meta-analysis of bedside screening test performance". Anesthesiology. 103 (2): 429–37. doi:10.1097/00000542-200508000-00027. PMID 16052126. S2CID 12600824.

- ^ Gonzalez, H; Minville, V; Delanoue, K; Mazerolles, M; Concina, D; Fourcade, O (2008). "The importance of increased neck circumference to intubation difficulties in obese patients". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 106 (4): 1132–6. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181679659. PMID 18349184. S2CID 22147759.

- ^ Krage, R; van Rijn, C; van Groeningen, D; Loer, SA; Schwarte, LA; Schober, P (2010). "Cormack-Lehane classification revisited". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 105 (2): 220–7. doi:10.1093/bja/aeq136. PMID 20554633.

- ^ Levitan RM, Everett WW, Ochroch EA (October 2004). "Limitations of difficult airway prediction in patients intubated in the emergency department". Ann Emerg Med. 44 (4): 307–13. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.006. PMID 15459613.

- ^ Roth D, Pace NL, Lee A, Hovhannisyan K, Warenits AM, Arrich J, Herkner H (May 2018). "Airway physical examination tests for detection of difficult airway management in apparently normal adult patients". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5 (5) CD008874. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008874.pub2. PMC 6404686. PMID 29761867.

- ^ Levitan (2004), Levitan RM, The limitations of difficult airway prediction in emergency airways, pp. 3–11

- ^ von Goedecke, A; Herff, H; Paal, P; Dörges, V; Wenzel, V (2007). "Field airway management disasters" (PDF). Anesthesia & Analgesia. 104 (3): 481–3. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000255964.86086.63. PMID 17312190.

- ^ a b c d e f g Benumof (2007), Hagberg CA, Georgi R and Krier C, Chapter 48: Complications of managing the airway, pp. 1181–218

- ^ Sengupta, P; Sessler, DI; Maglinger, P; Wells, S; Vogt, A; Durrani, J; Wadhwa, A (2004). "Endotracheal tube cuff pressure in three hospitals, and the volume required to produce an appropriate cuff pressure". BMC Anesthesiology. 4 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/1471-2253-4-8. PMC 535565. PMID 15569386.

- ^ Benumof (2007), Pousman RM and Parmley CL, Chapter 44: Endotracheal tube and respiratory care, pp. 1057–78

- ^ Polderman KH, Spijkstra JJ, de Bree R, Christiaans HM, Gelissen HP, Wester JP, Girbes AR (May 2003). "Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy in the ICU: optimal organization, low complication rates, and description of a new complication". Chest. 123 (5): 1595–602. doi:10.1378/chest.123.5.1595. PMID 12740279.

- ^ Hill, BB; Zweng, TN; Maley, RH; Charash, WE; Toursarkissian, B; Kearney, PA (1996). "Percutaneous dilational tracheostomy: report of 356 cases". Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 41 (2): 238–43. doi:10.1097/00005373-199608000-00007. PMID 8760530.

- ^ a b c d Katz, SH; Falk, JL (2001). "Misplaced endotracheal tubes by paramedics in an urban emergency medical services system" (PDF). Annals of Emergency Medicine. 37 (1): 32–7. doi:10.1067/mem.2001.112098. PMID 11145768.

- ^ Jones, JH; Murphy, MP; Dickson, RL; Somerville, GG; Brizendine, EJ (2004). "Emergency physician-verified out-of-hospital intubation: miss rates by paramedics". Academic Emergency Medicine. 11 (6): 707–9. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2003.12.026. PMID 15175215.

- ^ Pelucio, M; Halligan, L; Dhindsa, H (1997). "Out-of-hospital experience with the syringe esophageal detector device". Academic Emergency Medicine. 4 (6): 563–8. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03579.x. PMID 9189188.

- ^ Sayre, MR; Sackles, JC; Mistler, AF; Evans, JL; Kramer, AT; Pancioli, AM (1998). "Field trial of endotracheal intubation by basic EMTs". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 31 (2): 228–33. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70312-9. PMID 9472186.

- ^ White L, Melhuish T, Holyoak R, Ryan T, Kempton H, Vlok R (December 2018). "Advanced airway management in out of hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Am J Emerg Med. 36 (12): 2298–2306. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.09.045. PMID 30293843. S2CID 52931036.

- ^ Domino, KB; Posner, KL; Caplan, RA; Cheney, FW (1999). "Airway injury during anesthesia: a closed claims analysis". Anesthesiology. 91 (6): 1703–11. doi:10.1097/00000542-199912000-00023. PMID 10598613. S2CID 6525904.

- ^ Zuo, Mingzhang; Huang, Yuguang; Ma, Wuhua; Xue, Zhanggang; Zhang, Jiaqiang; Gong, Yahong; Che, Lu (2020). "Expert Recommendations for Tracheal Intubation in Critically ill Patients with Noval Coronavirus Disease 2019". Chinese Medical Sciences Journal. 35 (2): 105–109. doi:10.24920/003724. PMC 7367670. PMID 32102726.

high-risk aerosol-producing procedures such as endotracheal intubation may put the anesthesiologists at high risk of nosocomial infections

- ^ "World Federation Of Societies of Anaesthesiologists - Coronavirus". www.wfsahq.org. 25 June 2020.

Anaesthesiologists and other perioperative care providers are particularly at risk when providing respiratory care and tracheal intubation of patients with COVID-19

- ^ "Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infections when novel coronavirus is suspected: What to do and what not to do" (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 4.

The most consistent association of in-creased risk of transmission to healthcare workers (based on studies done during the SARS outbreaks of 2002–2003) was found for tracheal intubation.

- ^ a b Benumof (2007), McGee JP, Vender JS, Chapter 14: Nonintubation management of the airway: mask ventilation, pp. 345–70

- ^ Booth, A. W. G.; Vidhani, K.; Lee, P. K.; Thomsett, C.-M. (2017-03-01). "SponTaneous Respiration using IntraVEnous anaesthesia and Hi-flow nasal oxygen (STRIVE Hi) maintains oxygenation and airway patency during management of the obstructed airway: an observational study". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 118 (3): 444–451. doi:10.1093/bja/aew468. ISSN 0007-0912. PMC 5409133. PMID 28203745.

- ^ Pahor, AL (1992). "Ear, nose and throat in ancient Egypt: Part I". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 106 (8): 677–87. doi:10.1017/S0022215100120560. PMID 1402355. S2CID 35712860.

- ^ Frost, EA (1976). "Tracing the tracheostomy". Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 85 (5 Pt.1): 618–24. doi:10.1177/000348947608500509. PMID 791052. S2CID 34938843.

- ^ Stock, CR (1987). "What is past is prologue: a short history of the development of tracheostomy". Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal. 66 (4): 166–9. PMID 3556136.

- ^ Bhishagratna (1907), Bhishagratna, Introduction, p. iv

- ^ Yapijakis, C (2009). "Hippocrates of Kos, the father of clinical medicine, and Asclepiades of Bithynia, the father of molecular medicine. Review". In Vivo. 23 (4): 507–14. PMID 19567383.

- ^ Singer (1956), Galeni Pergameni C, De anatomicis administrationibus, pp. 195–207

- ^ a b Baker, AB (1971). "Artificial respiration: the history of an idea". Medical History. 15 (4): 336–51. doi:10.1017/s0025727300016896. PMC 1034194. PMID 4944603.

- ^ Longe (2005), Skinner P, Unani-tibbi

- ^ Shehata, M (2003). "The Ear, Nose and Throat in Islamic Medicine" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine. 2 (3): 2–5.

- ^ Goodall, EW (1934). "The story of tracheostomy". British Journal of Children's Diseases. 31: 167–76, 253–72.

- ^ Habicot (1620), Habicot N, Question chirurgicale, p. 108

- ^ Price, JL (1962). "The evolution of breathing machines". Medical History. 6 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1017/s0025727300026867. PMC 1034674. PMID 14488739.

- ^ Trousseau, A (1852). "Nouvelles recherches sur la trachéotomie pratiquée dans la période extrême du croup". Annales de Médecine Belge et étrangère (in French). 1: 279–88.

- ^ Rochester TF (1858). "Tracheotomy in Pseudo-Membranous Croup". Buffalo Medical Journal and Monthly Review. 14 (2): 78–98. PMC 8687930. PMID 35376437.

- ^ Hargrave, R (1934). "Endotracheal anesthesia in surgery of the head and neck". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 30 (6): 633–7. PMC 403396. PMID 20319535.

- ^ Mackenzie (1888), Mackenzie M, The case of Emperor Frederick III, p. 276

- ^ Jackson, C (1909). "Tracheostomy". The Laryngoscope. 19 (4): 285–90. doi:10.1288/00005537-190904000-00003. S2CID 221922284.

- ^ Radomski, T (2005). "Manuel García (1805–1906):A bicentenary reflection" (PDF). Australian Voice. 11: 25–41.

- ^ Sperati, G; Felisati, D (2007). "Bouchut, O'Dwyer and laryngeal intubation in patients with croup". Acta Otorhinolaryngolica Italica. 27 (6): 320–3. PMC 2640059. PMID 18320839.

- ^ Macmillan, M (2010). "William Macewen [1848–1924]". Journal of Neurology. 257 (5): 858–9. doi:10.1007/s00415-010-5524-5. PMID 20306068.

- ^ Hirsch, NP; Smith, GB; Hirsch, PO (1986). "Alfred Kirstein. Pioneer of direct laryngoscopy". Anaesthesia. 41 (1): 42–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb12702.x. PMID 3511764. S2CID 12259652.

- ^ Jackson, C (1913). "The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 17: 507–9. Abstract reprinted in Jackson, Chevalier (1996). "The technique of insertion of intratracheal insufflation tubes". Pediatric Anesthesia. 6 (3). Wiley: 230. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.1996.tb00434.x. ISSN 1155-5645. S2CID 72582327.

- ^ Jackson (1922), Jackson C, Instrumentarium, pp. 17–52

- ^ Burkle, CM; Zepeda, FA; Bacon, DR; Rose, SH (2004). "A historical perspective on use of the laryngoscope as a tool in anesthesiology". Anesthesiology. 100 (4): 1003–6. doi:10.1097/00000542-200404000-00034. PMID 15087639. S2CID 36279277.

- ^ Magill, I (1930). "Technique in endotracheal anaesthesia". British Medical Journal. 2 (1243): 817–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1243.817-a. PMC 2451624. PMID 20775829.

- ^ McLachlan, G (2008). "Sir Ivan Magill KCVO, DSc, MB, BCh, BAO, FRCS, FFARCS (Hon), FFARCSI (Hon), DA, (1888–1986)". Ulster Medical Journal. 77 (3): 146–52. PMC 2604469. PMID 18956794.

- ^ Magill, I (1920). "Forceps for intratracheal anaesthesia". British Medical Journal. 2 (571): 670. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.571.670. PMC 2338485. PMID 20770050.

- ^ Magill, I (1926). "An improved laryngoscope for anaesthetists". The Lancet. 207 (5349): 500. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)17109-6.

- ^ Magill, I (1921). "A Portable Apparatus for Tracheal Insufflation Anaesthesia". The Lancet. 197 (5096): 918. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)55592-5.

- ^ Magill, I (1921). "Warming Ether Vapour for Inhalation". The Lancet. 197 (5102): 1270. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)24908-3.

- ^ Magill, I (1923). "An apparatus for the administration of nitrous oxide, oxygen, and ether". The Lancet. 202 (5214): 228. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)22460-X.

- ^ Macintosh, RR (1943). "A new laryngoscope". The Lancet. 241 (6233): 205. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)89390-3.

- ^ "History of endoscopes. Volume 2: Birth of gastrocameras". Olympus Corporation. 2010.

- ^ "History of endoscopes. Volume 3: Birth of fiberscopes". Olympus Corporation. 2010.

- ^ Murphy, P (1967). "A fibre-optic endoscope used for nasal intubation". Anaesthesia. 22 (3): 489–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1967.tb02771.x. PMID 4951601. S2CID 33586314.

- ^ Finucane, BT; Kupshik, HL (1978). "A flexible stilette for replacing damaged tracheal tubes". Canadian Anaesthetists' Society Journal. 25 (2): 153–4. doi:10.1007/BF03005076. PMID 638831.

References

[edit]- Barash, PG; Cullen, BF; Stoelting, RK, eds. (2009). Clinical Anesthesia (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-8763-5.

- Benumof, JL, ed. (2007). Benumof's Airway Management: Principles and Practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby-Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-02233-0.

- Bhishagratna, KL, ed. (1907). Sushruta Samhita, Volume1: Sutrasthanam. Calcutta: Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna.