Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

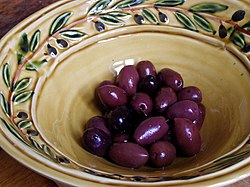

Kalamata

View on Wikipedia

Kalamata (Greek: Καλαμάτα [kalaˈmata]) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece after Patras, and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regional unit, it lies along the Nedon River at the head of the Messenian Gulf.[3]

Key Information

The 2021 census recorded 72,906 inhabitants for the wider Kalamata Municipality, of which 66,135 resided in the municipal unit of Kalamata, and 58,816 in the city proper.[2] Kalamata is renowned as the land of the Kalamatianos dance, Kalamata olives and Kalamata olive oil.

Name

[edit]The modern name Kalamáta likely comes from Παναγία η Καλαμάτα, Panagía i Kalamáta, 'Virgin Mary with beautiful eyes'; another hypothesis is a corruption of the older name Καλάμαι, Kalámai, 'reeds'.[4]

Administration

[edit]The municipality Kalamata was formed as part of the 2011 local government reform by the merger of the following four former municipalities, each of which subsequently became municipal units:[5]

The municipality has an area of 440 km2 (170 mi2), the area of the municipal unit is 253 km2 (98 mi2).[6]

Subdivisions

[edit]The municipal unit of Kalamata is subdivided into the following communities (population according to the 2021 census, settlements within the community listed):[2]

Municipal Unit:

- Kalamata (population: 66,135)

Local communities:

- Kalamata city proper (population 58,816)

- Alagonia (population: 154; Alagonia, Machalas)

- Antikalamos (population: 390; Antikalamos, Goulismata)

- Artemisia (population: 88; Agios Ioannis Theologos, Artemisia, Theotokos)

- Asprochoma (population: 1,244; Akovitika, Asprochoma, Kagkareika, Kalami, Katsikovo, Lagkada-Dimitrakopouleika)

- Verga (population: 2,125; Paralia Vergas, Ano Verga, Kato Verga )

- Elaiochori (population: 243; Arachova, Dendra, Diasella, Elaiochori, Moni Dimiovis, Perivolakia)

- Karveli (population: 74; Agia Triada, Emialoi, Karveli, Kato Karveli)

- Ladas (population: 102; Agia Marina, Agios Vasileios, Ladas, Silimpoves-Agios Vasilis)

- Laiika (population: 1,449; Laiika, Katsaraiika, Spitakia, Xerokampi)

- Mikri Mantineia (population: 615; Alimoneika, Mikra Mantineia, Zouzouleika)

- Nedousa (population: 86)

- Piges (population: 71; Piges, Skourolakkos)

- Sperchogeia (population: 678)

Province

[edit]The province of Kalamata (Greek: Επαρχία Καλαμών) was one of the provinces of the Messenia Prefecture. Its territory corresponded with that of the current municipalities Kalamata and West Mani.[7] It was abolished in 2006.

History

[edit]

Kalamata occupies the site of an ancient city, the identity of which has been disputed. The name clearly refers to ancient Calamae, but it has been established in the 20th century that the actual site is that of ancient Pharae,[8][9] a city already mentioned by Homer. It was long believed that the area that the city presently occupies was covered by the sea during ancient times, but the proto-Greek and Archaic-period remains (Temple of Poseidon) that were unearthed at Akovitika region prove otherwise.

Middle Ages

[edit]

Pharae was rather unimportant in antiquity, and the site continued in obscurity until middle Byzantine times.[8] Kalamata is first mentioned in the 10th-century Life of St. Nikon the Metanoeite with its modern name.[8][10] Medieval Kalamata was not a port, as the local coast offered no shelter to ships from the weather, but lay further inland, at the foot of the western outliers of Mount Taygetos.[11] As the capital of the fertile Messenian plain,[12] the town experienced a period of prosperity in the 11th–12th centuries, as attested by the five surviving churches built in this period, including the Church of the Holy Apostles, as well as the comments of the Arab geographer al-Idrisi, who calls it a "large and populous" town.[8]

Following the Fourth Crusade, Kalamata was conquered by Frankish feudal lords William of Champlitte and Geoffrey of Villehardouin in 1205, when its Byzantine fortress was apparently in so bad a state that it could not be defended against them. Thus, the town became part of the Principality of Achaea, and after Champlitte granted its possession to Geoffrey of Villehardouin, the town was the center of the Villehardouins' patrimony in the Principality. Prince William II of Villehardouin was born and died there.[8][13] After William II's death in 1278, Kalamata remained in the hands of his widow, Anna Komnene Doukaina, but when she remarried to Nicholas II of Saint Omer, King Charles of Anjou was loath to see this important castle in the hands of a vassal, and in 1282 Anna exchanged it with lands elsewhere in Messenia.[13]

In 1292 or 1293, two local Melingoi Slavic captains managed to capture the castle of Kalamata by a ruse and, aided by 600 of their fellow villagers, took over the entire lower town as well in the name of the Byzantine emperor, Andronikos II Palaiologos. Constable John Chauderon in vain tried to secure their surrender, and was sent to Constantinople, where Andronikos agreed to hand the town over, but then immediately ordered his governor in Mystras not to do so. In the event, the town was recovered by the Franks through the intercession of a local Greek, a certain Sgouromalles.[14] In 1298, the town formed the dowry of Princess Matilda of Hainaut upon her marriage to Guy II de la Roche. Matilda retained Kalamata as her fief until 1322, when she was dispossessed and the territory reverted to the princely domain.[13] In 1358, Prince Robert gifted the châtellenie of Kalamata (comprising also Port-de-Jonc and Mani) to his wife, Marie de Bourbon, who kept it until her death in 1377.[13] The town remained one of the largest in the Morea—a 1391 document places it, with 300 hearths, on par with Glarentza—but it nevertheless declined in importance throughout the 14th and 15th centuries in favour of other nearby sites like Androusa. Kalamata remained in Frankish hands until near the end of the Principality of Achaea, coming under the control of the Byzantine Despotate of the Morea only in 1428.[13]

Ottoman period and War of Independence

[edit]

Kalamata was occupied by the Ottomans in 1481.[citation needed] In 1659, during the long war between Ottomans and Venetians over Crete, the Venetian commander Francesco Morosini, captured Kalamata in an effort to divert Ottoman attention from the Siege of Candia, and raise a wider revolt. The Venetian fleet took Kalamata without effort, as the Ottomans abandoned the town. The town and its castle were plundered and destroyed, and all able-bodied men were carried off to serve as rowers in the Venetian galleys.[15][16] Morosini returned in 1685, at the start of the Morean War: on 14 September 1685 the Venetians defeated an Ottoman army before Kalamata, and again plundered and destroyed the town's castle, as it was judged obsolete.[17][18] Kalamata was then ruled by Venice as part of the "Kingdom of the Morea" (Italian: Regno di Morea). During the Venetian occupation the city was developed and thrived economically. However, the Ottomans reoccupied Kalamata in the war of 1715 and controlled it until the Greek War of Independence.

Kalamata was the first city to be liberated as the Greeks rose in the Greek War of Independence. On 23 March 1821, it was taken over by the Greek revolutionary forces under the command of generals Theodoros Kolokotronis, Petros Mavromichalis and Papaflessas. However, in 1825, the invading Ottoman officer Ibrahim Pasha destroyed the city.

Modern period

[edit]

In independent Greece, Kalamata was rebuilt and became one of the most important ports in the Mediterranean Sea. It is not surprising that the second-oldest Chamber of Commerce in the Mediterranean, after that of Marseille, exists in Kalamata. In 1934, a large strike of harbor workers occurred in Kalamata. The strike was violently suppressed by the government, resulting in the death of five workers and two other residents of the town.[19]

During World War II on 29 April 1941, a battle was fought near the port between the invading German forces and the 2nd New Zealand Division, for which Jack Hinton was later awarded the Victoria Cross. Kalamata was liberated on 9 September 1944, after a battle between ELAS and the local Nazi collaborators.

Kalamata was again in the news on 13 September 1986, when it was hit by an earthquake that measured 6.2 on the surface wave magnitude scale. It was described as "moderately strong" but caused heavy damage throughout the city, killed 20 people and injured 330 others.[20][21][22][23]

Kalamata has developed into a modern provincial capital and has returned to growth in recent years. Today, Kalamata has the second largest population and mercantile activity in Peloponnese. It makes important exports, particularly of local products such as raisins, olives and olive oil. It is also the seat of the Metropolitan Bishop of Messenia. The current Metropolitan Bishop is Chrysostomus III of Kalamata, since 15 March 2007.

Sights

[edit]

Maria Callas Alumni Association of the Music School of Kalamata / "Maria Callas Museum"

There are numerous historical and cultural sights in Kalamata, such as the Villehardouin castle, the Ypapanti Byzantine church, the Kalograion monastery with its silk-weaving workshop where the Kalamata scarves are made, and the municipal railway park. The Church of the Holy Apostles is where Mavromichalis declared the revolt against Ottoman rule in 1821. Art collections are housed at the Municipal Gallery, the Archaeological Museum of Messenia and the Folk Art Museum.

- Benakeion Archaeological Museum of Kalamata,[24] located in the heart of the historical centre of Kalamata.

- Cultural events, such as the Kalamata International Dance Festival

- The Kalamata Dance Megaron

- Kalamata Drama International Summer School

- Kalamata Castle from the 13th century AD.[25]

- The marina and the Port of Kalamata, located SW of the city centre, is the main and largest port in Messenia and the southern part of the Peloponnese.

- Kalamata Municipal Stadium, home of Messiniakos, seats 5,400 spectators

- The Railway Museum of the Municipality of Kalamata,[26] a railway museum which first opened since 1986

- Ancient Messene, some 15–20 km (9–12 mi) north-west of modern Messini

- The Maria Callas Alumni Association of the Music School of Kalamata (www.mariacallas.gr) with the exhibition of the personal letters of the legendary Maria Callas.

Cathedral of Ypapanti

[edit]Kalamata's cathedral of the Ypapanti (Presentation of the Lord to the Temple) nestles beneath the 14th-century Frankish castle. The foundation stone was laid on 25 January 1860, and the building was consecrated on 19 August 1873. It suffered great damage during the 1986 earthquake,[22] but was subsequently restored. The Festival of the Ypapanti (27 January through 9 February) is of national importance for the Greek Orthodox Church and, locally, the occasion for a holiday (2 February), when the procession of what is believed to be a miraculous icon, first introduced in 1889, takes place.

In late January 2010, the city hosted the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the cathedral. He was offered the golden key of the city. The region around Kalamata has provided two Ecumenical patriarchs in the past.

Economy

[edit]

Kalamata's Chamber of Commerce is the second-oldest in the Mediterranean after Marseille. Kalamata is well known for its black Kalamata olives.

Karelia Tobacco Company has been in operation in Kalamata since 1888.

Historical population

[edit]| Year | City | Municipal unit | Municipality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 42,075 | – | – |

| 1991 | 43,625 | 50,693 | – |

| 2001 | 49,550 | 57,620 | – |

| 2011 | 54,567 | 62,409 | 69,849 |

| 2021 | 58,816 | 66,135 | 72,906 |

Climate

[edit]According to the meteorological station in the nearby airport, Kalamata has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) with mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers.[27] Kalamata receives plenty of precipitation during the winter, while summers are hot and generally dry with plenty of sunshine. The highest maximum temperature ever recorded in Kalamata is 45.0 °C or 113.0 °F on 24 June 2007 and the lowest minimum ever recorded is −5 °C or 23 °F on 14 February 2004. A reading of 45.1 °C (113.2 °F) was reported in the city station which is operated by the National Observatory of Athens on 23 July 2023.[28]

| Climate data for Kalamata airport, HNMS 1971–2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

39.9 (103.8) |

45.0 (113.0) |

44.4 (111.9) |

43.2 (109.8) |

38.9 (102.0) |

37.0 (98.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

45.0 (113.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

14.9 (58.8) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

29.1 (84.4) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.4 (88.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.8 (49.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.0 (23.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 105.6 (4.16) |

95.0 (3.74) |

66.3 (2.61) |

51.9 (2.04) |

22.8 (0.90) |

7.8 (0.31) |

6.0 (0.24) |

10.9 (0.43) |

36.7 (1.44) |

85.7 (3.37) |

141.7 (5.58) |

141.2 (5.56) |

780.3 (30.72) |

| Average precipitation days | 14.4 | 13.7 | 11.8 | 10.3 | 6.8 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 6.1 | 9.9 | 12.8 | 15.7 | 108.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.0 | 73.5 | 73.3 | 70.3 | 66.3 | 57.7 | 57.8 | 61.3 | 66.8 | 72.1 | 77.6 | 77.3 | 70.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 143.6 | 140.8 | 185.9 | 212.2 | 286.0 | 338.2 | 367.6 | 346.6 | 269.9 | 205.6 | 150.6 | 131.1 | 2,778.1 |

| Source: HNMS climate means,[29] NOAA extremes & sunshine 1961-1990[30] Info Climat extremes 1991-present[31] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

[edit]

Kalamata is accessed by GR-7/E55/E65 in the west, and GR-82 runs through Kalamata and into the Taygetus. The motorway to Kalamata from Tripoli is complete.[32]

Kalamata is served by a metre gauge railway line of the former Piraeus, Athens and Peloponnese Railways, now owned by the Hellenic Railways Organisation (OSE). There is a station and a small freight yard in the city, as well as a rolling stock maintenance depot to the north. There used to be a mainline train service to Kyparissia, Pyrgos and Patras, and a suburban service to Messini and the General Hospital. However, in December 2010, all train services from Kalamata, along with those in the rest of the Peloponnese south of Corinth, were discontinued on economic grounds, and the train station is now closed. A previously disused extension line to the port is now a Railway Park, with old steam engines on display, and a café in the old station building. Since 10 June 2025, there has been an effort in the Kalamata municipal council to restore the Kalamata - Messinia part of the line. The Municipal government wishes for the line to connect the port of Kalamata, Kalamata International Airport, the Courts and finally Messinia. The vice-mayor supported the plan and wished to install traffic lights should construction be implemented finishing to say that by the end of 2025 3km of the line will have been completed. The local KKE-backed Councillor claimed that the shutting down of the train tracks is one of the most destructive decisions made.[33]

There is a bus link, operated by the KTEL company, to Tripoli, Corinth, and Athens, with frequent services. Ferries are available to places such as the Greek islands of Kythira and Crete in the summer months. Also in the summer months, charter and scheduled flights fly direct to Kalamata International Airport from some European cities. A scheduled service by Aegean Airlines once a day linking Kalamata and Athens International Airport commenced in 2010.

Kalamata also has four urban bus lines that cross the city and its suburbs.[34]

Cuisine

[edit]

Local specialities:

Notable people

[edit]

- Andreas Apostolopoulos (born 1952), real estate developer and sports team owner

- John Barounis, Greek Australian politician

- Giannis Christopoulos (born 1972), football coach

- Yiannis Chryssomallis ("Yanni") (born 1954), composer and musician

- Vassilis C. Constantakopoulos (1935–2011), shipowner

- Aggeliki Daliani (born 1979) actress

- Nikolaos Doxaras, painter

- Panagiotis Doxaras, painter

- Lawrence Durrell (1912–1990), writer [35]

- Nikolaos Georgeas (born 1976), footballer

- Alexandros Koumoundouros, Prime Minister of Greece in the 19th century

- Elia Markopoulos, American professional wrestler who spent his childhood summers at his family's home in Kalamata.

- Gerasimos Michaleas (1945), American Eastern Orthodox bishop

- Panos Mihalopoulos (born 1949), actor

- Nikos Moulatsiotis, footballer and coach

- Sokratis Papastathopoulos (born 1988), footballer

- Prokopis Pavlopoulos (born 1950) lawyer, university professor, politician, former President of Greece from 2015 to 2020

- Vassilis Photopoulos (1934–2007) painter, film director, art director and set designer

- Nikolaos Politis (1872–1942), diplomat, lawyer

- Maria Polydouri (1902–1930), poet

- Aris San (born Aristides Saisanas, 1940–1992), Greek-Israeli singer

- Angelos Skafidas, footballer and coach

- Kenny Stamatopoulos (born 1979), footballer

- Michail Stasinopoulos (1903–2002) lawyer, President of the Republic of Greece

- Gregory Stephanopoulos (born 1950) Professor of Chemical Engineering, MIT

- William II of Villehardouin (died 1278) the last Villehardouin prince of Achaea

- Mihalis Papagiannakis (1941–2009), Greek politician

- Panagiotis Benakis (1700–1771), Greek notable

- Stavros Kostopoulos (1900–1968), Greek banker and politician

- Dimitrios Stefanakos (1936–2021), Greek footballer

- Konstantinos Ventiris (1892–1960), Greek army officer

- Panagiotis Bachramis (1976–2010), Greek footballer

- Nikos Economopoulos (born 1953), Greek photographer

- Bleepsgr, Greek street artist

Sporting teams

[edit]Kalamata hosts a lot of notable sport clubs with earlier presence in the higher national divisions in Greek football. It also hosts one of the oldest Greek club, the club Messiniakos FC founded in 1888.

| Sport clubs based in Kalamata | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Club | Founded | Sports | Achievements |

| Messiniakos GS | 1888 | Football, Volleyball | Earlier presence in Beta Ethniki football, earlier presence in A1 Ethniki volleyball |

| A.E.K. Kalamata | 1926 | Football | Earlier presence in Beta Ethniki |

| Apollon Kalamata | 1927 | Football | Earlier presence in Beta Ethniki |

| Prasina Poulia Kalamata | 1938 | Football | Earlier presence in Beta Ethniki |

| Kalamata FC | 1967 | Football | Earlier presence in A Ethniki |

| AO Kalamata 1980 | 1980 | Basketball, Volleyball | Presence in A2 Ethniki volleyball |

| Argis Kalamata | 1994 | Athletics | |

International relations

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Municipality of Kalamata, Municipal elections – October 2023 Archived 8 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Ministry of Interior

- ^ a b c "Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2021, Μόνιμος Πληθυσμός κατά οικισμό" [Results of the 2021 Population - Housing Census, Permanent population by settlement] (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 29 March 2024.

- ^ For a detailed introduction to various aspects of the city, see the Kalamata Municipality’s online guide Archived 18 June 2024 at the Wayback Machine (undated)(retrieved 18/06/2024).

- ^ Kolonia, Amalia; Peri, Massimo, eds. (2008). "Gli scambi linguistici fra Italia e Grecia". Greco antico neogreco e italiano (in Italian and Greek). Bologna: Zanichelli. p. 95. ISBN 978-88-08-06429-5.

- ^ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette. Archived from the original on 18 July 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2015.

- ^ "Detailed census results 1991" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. (39 MB) (in Greek and French)

- ^ a b c d e Gregory, Timothy E. (1991). "Kalamata". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1091. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- ^ Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe [The Frankish Morea. Historical, Topographic and Archaeological Studies on the Principality of Achaea] (in French). Paris: De Boccard. pp. 408, 666 (note 4). OCLC 869621129.

- ^ Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe [The Frankish Morea. Historical, Topographic and Archaeological Studies on the Principality of Achaea] (in French). Paris: De Boccard. p. 408. OCLC 869621129.

- ^ Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe [The Frankish Morea. Historical, Topographic and Archaeological Studies on the Principality of Achaea] (in French). Paris: De Boccard. pp. 408–409. OCLC 869621129.

- ^ Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe [The Frankish Morea. Historical, Topographic and Archaeological Studies on the Principality of Achaea] (in French). Paris: De Boccard. p. 409. OCLC 869621129.

- ^ a b c d e Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe [The Frankish Morea. Historical, Topographic and Archaeological Studies on the Principality of Achaea] (in French). Paris: De Boccard. pp. 409–410. OCLC 869621129.

- ^ Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe [The Frankish Morea. Historical, Topographic and Archaeological Studies on the Principality of Achaea] (in French). Paris: De Boccard. p. 168. OCLC 869621129.

- ^ Andrews, Kevin (1978) [1953]. Castles of the Morea. Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert. p. 30. ISBN 90-256-0794-2.

- ^ Finlay, George (1877). A History of Greece from its Conquest by the Romans to the Present Time, B.C. 146 to A.D. 1864, Vol. V: Greece under Othoman and Venetian Domination A.D. 1453–1821. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 177.

- ^ Andrews, Kevin (1978) [1953]. Castles of the Morea. Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert. p. 28. ISBN 90-256-0794-2.

- ^ Finlay, George (1877). A History of Greece from its Conquest by the Romans to the Present Time, B.C. 146 to A.D. 1864, Vol. V: Greece under Othoman and Venetian Domination A.D. 1453–1821. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 177–178.

- ^ Μπιτσάνης, Ηλίας. "80 χρόνια από την εξέγερση των λιμενεργατών Καλαμάτας". ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑ Online (in Greek). Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Anagnostopolous, S. A.; Rinaldis, D.; Lekidis, V. A.; Margaris, V. N.; Theodulidis, N. P. (1987). "The Kalamata, Greece, Earthquake of September 13, 1986". Earthquake Spectra. 3 (2): 365–402. Bibcode:1987EarSp...3..365A. doi:10.1193/1.1585434. S2CID 128902740.

- ^ "GREECE Kalamata now tent city". The Canberra Times. Vol. 61, no. 18, 614. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 18 September 1986. p. 4. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 24 February 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "World news: Earthquake in south Greece kills ten". The Canberra Times. Vol. 61, no. 18, 611. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 15 September 1986. p. 4. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 24 February 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "More tremors in Greek town". The Canberra Times. Vol. 61, no. 18, 612. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 16 September 1986. p. 4. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 24 February 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Καλαμάτα - Μουσεία". Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Castle of Kalamata Archived 11 July 2024 at the Wayback Machine Greek Castles

- ^ "Hellenic Ministry of Culture | Railway Museum of the Municipality of Kalamata". Odysseus.culture.gr. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ "Kalamata, Greece Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "Latest Conditions in Kalamata". penteli.meteo.gr. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ "Κλιματικά Δεδομένα ανά Πόλη- ΜΕΤΕΩΓΡΑΜΜΑΤΑ, ΕΜΥ, Εθνική Μετεωρολογική Υπηρεσία". Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ "Kalamata Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (FTP).[dead ftp link] (To view documents see Help:FTP)

- ^ "Normales et records climatologiques 1991-2020 à Kalamata Airport - Infoclimat". Archived from the original on 16 June 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Παραδόθηκε στην κυκλοφορία ο περιφερειακός της Καλαμάτας (βίντεο) Archived 3 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 19 Νοεμβρίου 2016, - ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑ Online

- ^ "Αίτημα επαναλειτουργίας σιδηρόδρομου στο Δημοτικό Συμβούλιο: Πίεση για τη γραμμή Καλαμάτα - Μεσσήνη" eleftheriaonline.gr Retrieved 14 June 2025

- ^ "Urban Bus". terrabook. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Durrell was the director of the British Council’s English Language Institute in Kalamata from September 1940 to April 1941. The little house provided for him on Navarinou Street (no. 83), on the seafront, remains. With his first wife Nancy (née Myers) and baby daughter Penelope, the family fled to Egypt as the German army advanced (see, e.g., Ian MacNiven (1998), Lawrence Durrell: a biography, Faber, pp.226-7; Nikos Zervis (1999), Lawrence Durrell in Kalamata, isbn: 978-960-90690-1-0 (published privately) (in Greek); Joanna Hodgkin (2023), Amateurs in Eden: the story of a bohemian marriage; Nancy and Lawrence Durrell, Virago, pp.258-63

- ^ Municipality of Kalamata. "Εκδηλώσεις τιμής και μνήμης για τα θύματα και τους αγνοούμενους στην Κύπρο το 1974". Kalamata.gr. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ https://www.kalamata.gr/el/dimos/adelfopoiiseis

- ^ "China's Xi'an forges sister city ties with Greece's Kalamata _English_Xinhua". News.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Kampouris, Nick (12 February 2020). "Lowell, Massachusetts and Kalamata, Greece to Become Sister Cities". Greek Reporter. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

External links

[edit]- Municipality of Kalamata (in Greek)

- Historic maps of Kalamata Archived 25 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Messinian Chamber of Commerce and Industry Archived 7 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Ministry of Culture – Messinia

- Kalamata The Official website of the Greek National Tourism Organisation

Kalamata

View on GrokipediaKalamata is the capital and largest city of the Messenia regional unit in the Peloponnese peninsula of southern Greece, serving as a key port on the Messenian Gulf and the second-most populous urban center in the region after Patras.[1][2]

With a municipal population of 72,906 according to the 2021 census, the city lies at the foothills of the Taygetus mountain range and is built near the site of ancient Pharae, with archaeological evidence of habitation dating to the Proto-Helladic period around 2600–2300 BC.[2][3]

Kalamata's economy centers on agriculture, particularly the production and export of PDO-protected Kalamata olives, alongside tourism drawn to its beaches, medieval castle, and cultural events such as the International Dance Festival.[4][5]

Historically significant as the first Greek city liberated from Ottoman rule on March 23, 1821, during the War of Independence, it endured major destruction from the 1986 earthquake but has since rebuilt into a modern hub blending heritage sites with commercial activity.[6][3]

Geography

Location and physical features

Kalamata is situated on the northern coast of the Messenian Gulf in the southwestern Peloponnese peninsula of Greece, serving as the capital of the Messenia regional unit.[7] Its geographic coordinates are approximately 37°02′N 22°07′E.[8] The city occupies a position at the foot of the Taygetus Mountains to the east, which form a steep barrier rising to elevations exceeding 2,000 meters, contrasting with the expansive coastal plain to the west.[9] This coastal plain, part of the broader Messenian plain, consists of alluvial soils deposited by rivers, fostering intensive agriculture, notably the cultivation of olive groves that produce the renowned Kalamata olives.[10] The Pamisos River, the principal waterway of the region at 44 km in length, traverses the plain from its source in the Taygetus foothills, providing irrigation and discharging into the Messenian Gulf adjacent to the city.[8] Sandy beaches extend approximately 4 km along the gulf shoreline, characterized by clear waters and gentle slopes conducive to maritime activities.[9] The terrain's juxtaposition of mountainous hinterland and low-lying coastal zone, within the tectonically active Hellenic subduction zone, renders the area susceptible to seismic events, shaping its geohazard profile.[11]Climate

Kalamata experiences a Mediterranean climate characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, with precipitation concentrated from October to March.[12] Annual average precipitation totals approximately 782 mm, with December recording the highest monthly amount at 152.6 mm over an average of 11.6 rain days, while July sees only 4.2 mm across 1.3 days.[13] Mean annual temperature is around 17–18 °C, derived from monthly averages ranging from 9.8 °C in January to 26.2 °C in August.[12] Summer months (June to August) feature average high temperatures of 28.8–31.3 °C and low humidity levels around 58–60%, moderated by breezes from the nearby Messenian Gulf that prevent extreme heat buildup despite occasional peaks exceeding 40 °C.[13] Winters (December to February) are mild with average highs of 15.3–16.7 °C and lows of 5.7–7.2 °C, accompanied by higher humidity near 75% and the bulk of annual rainfall.[12] [13] Long-term records from local meteorological stations since the 1950s show relatively stable patterns, with a minor observed warming trend of less than 1 °C in annual averages through recent decades, alongside slight increases in summer drought frequency consistent with broader Mediterranean shifts.[14] Extreme events remain infrequent, with the highest recorded temperature of 45 °C on June 24, 2007, and the lowest of -5 °C on January 14, 1895, though such outliers have not significantly altered baseline variability.[15]History

Ancient and Byzantine eras

The site of modern Kalamata corresponds to ancient Pharae, established as a significant Mycenaean center during the Late Helladic period (1580–1120 BC).[3] Pottery sherds dated to 1200–1100 BC provide evidence of this early settlement phase.[3] Earlier traces of human activity appear in the Proto-Helladic period (2600–2300 BC) at Akovitika, approximately 2–3 km northwest.[3] Following the Dorian invasion circa 1100 BC, Pharae declined and functioned as a perioecic town subordinate to Sparta during the Messenian Wars (743–459 BC).[3] Classical period remains are limited but include foundations of walls and a tower from Pharae's fortifications, located about 250 meters south of the later castle site.[3] After liberation from Spartan control in 369 BC by Theban forces led by Epaminondas, Pharae joined the Messenian federation.[3] Additional artifacts, such as 4th-century BC retaining walls, grave relief stelae, inscriptions, votive offerings, and fragments of a relief sarcophagus, attest to activity from Geometric times through the Roman era.[16] Roman administrative reassignments oscillated Pharae between Messenian and Laconian territories under emperors Augustus (31 BC), Tiberius (14–37 AD), and Vespasian (78 AD).[3] Pausanias noted temples and a sanctuary of Tyche (Fortune) in the 2nd century AD, though continuous later occupation has obscured major architectural features.[17] In the Byzantine period, the acropolis atop the ancient Pharae site was fortified by the 7th century to defend against Slavic incursions into the Peloponnese, exploiting the hill's elevated terrain for strategic advantage despite regional vulnerabilities to overland and naval threats.[3] Slavic groups settled nearby in areas like Kalames (later Yiannitsa) and Selitsa but were largely eliminated by mid-9th century Byzantine military efforts.[3] The settlement, known as Kalamata by the 10th century, is first documented in the Life of Saint Nikon Metanoeite (968–998 AD).[3] Numismatic evidence includes coins of Constantine VI and Irene (780–790 AD) and Leo VI (886–912 AD), suggesting ties to imperial trade routes along a royal road.[3] Ecclesiastical structures like the churches of the Holy Apostles and Saint Charalambos emerged in the 11th–12th centuries, indicating cultural persistence amid broader disruptions from Arab raids, though direct impacts on the site lack specific attestation.[3]Ottoman period

Kalamata came under Ottoman control as part of the conquest of the Morea peninsula between 1458 and 1460, integrating the region into the empire's administrative framework following the collapse of the Byzantine Despotate.[18] The city was assigned to the Sanjak of Modon, where Ottoman authorities imposed the timar system, allocating land grants to sipahis in exchange for military service and revenue from agricultural taxes.[19] Local agriculture, particularly olive cultivation, formed the backbone of the economy, with taxation targeting harvests to fund imperial expenditures; by the late Ottoman era, Kalamata functioned as a market hub for wheat, cotton, and olive products from the hinterland.[3] Heavy impositions, including the cizye poll tax on non-Muslims and tithes on produce, prompted periodic migrations and depopulation, as families sought refuge in autonomous areas like Mani or Venetian-held islands.[20] Episodes of resistance occurred, such as alignments with Venetian forces during the Morean War (1684–1699), when Kalamata briefly fell to Republic of Venice troops in 1685 before reverting to Ottoman rule in 1715 after the subsequent Ottoman-Venetian conflict.[21] Pragmatic adaptation characterized much of the period, with Christian elites participating in trade and the devshirme levy supplying recruits to the Janissary corps, while the Orthodox millet afforded ecclesiastical governance under Phanariote oversight. Ottoman authorities reinforced infrastructure, adding fortifications to the medieval castle to counter internal unrest and external threats.[22] Under the millet system, cultural and economic stagnation prevailed relative to prior eras, as fiscal extraction prioritized short-term revenues over investment, contributing to infrastructural decay amid the empire's 18th-century decline; empirical tax registers reveal consistent reliance on agrarian levies without significant innovation in local production.[23]Greek War of Independence

The liberation of Kalamata on March 23, 1821, marked one of the earliest and most significant victories in the Greek War of Independence, as Maniot forces under Petros Mavromichalis captured the city from Ottoman control after a brief two-day siege. Approximately 2,000 Maniot warriors, known for their guerrilla tactics and autonomy from Ottoman rule, advanced from Areopoli following their declaration of war on March 17, overwhelming the smaller Ottoman garrison led by Albanian troops who ultimately surrendered with minimal resistance. This success, supported by local leaders including Papaflessas and Theodoros Kolokotronis, secured the castle and port, disrupting Ottoman supply lines and providing a strategic base for further operations in the Peloponnese.[24][21][25] The tactical advantages stemmed from Maniot alliances, which leveraged rugged terrain familiarity and clan-based irregular warfare to outmaneuver Ottoman forces, resulting in low Greek casualties compared to the rapid capitulation of defenders estimated at several hundred. Kalamata's fall ignited the broader Peloponnesian revolt, inspiring uprisings in nearby regions and establishing a foothold that facilitated arms smuggling via the port, though initial gains were hampered by internal divisions among Greek chieftains, including rivalries between mainland and island factions that delayed unified command structures. Despite these challenges, the event's causal role in national momentum was evident, as it preceded the formal Patriarchal excommunication of the Sultan on March 24 and Germanos' flag-raising in Patras on March 25, galvanizing widespread rebellion.[26][27][28]19th to 20th century developments

Following the establishment of the Kingdom of Greece in 1832, Kalamata integrated into the new state as the administrative center of Messenia, fostering steady urban expansion driven by its strategic port position and agricultural hinterland.[3] By mid-century, the city had rebuilt from wartime devastation, with population rising from approximately 7,000 in 1879 to over 15,000 by century's end, supported by commerce in figs, raisins, olive oil, and silk production that employed hundreds in local looms until World War I.[3] Infrastructure advancements accelerated trade in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including port reconstruction initiated in 1882 and completed by 1901, which enhanced export capacities and earned the city the moniker "Marseilles of the Morea."[3] The Piraeus-Athens-Peloponnese railway network extended to Kalamata via Corinth by the 1890s, connecting it to Athens and facilitating agricultural outflows, while olive presses proliferated after 1875 amid expanding cultivation.[3] These developments solidified Kalamata's role as a regional economic hub, though growth remained tethered to volatile commodity markets and limited industrialization. The 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe spurred a refugee influx, with Asia Minor Greeks settling along the coast and contributing to rapid demographic and urban expansion through the 1920s and 1930s, augmenting the labor pool for agriculture and small-scale manufacturing.[29] During World War II Axis occupation (1941–1944), Kalamata endured resource extraction and reprisals, with communist-led ELAS partisans engaging in sabotage and clashes against Italian and German forces, alongside documented collaboration by local security battalions that aided occupation authorities in suppressing dissent.[30] ) Post-1949 Greek Civil War recovery emphasized agricultural stabilization in Messenia, where state-backed land reforms under laws like 1950 redistribution acts parcelled larger estates to smallholders, boosting olive and citrus output but entailing bureaucratic delays and uneven enforcement that strained rural credit access.[31] Efforts to promote voluntary cooperatives for marketing and inputs faced resistance from independent farmers wary of centralized control, reflecting broader tensions between state directives and local agrarian traditions amid Marshall Plan aid.[32] By mid-century, these measures underpinned export-led rebound, though dependency on EU precursors for modernization persisted into the late 20th century.[33]Contemporary history

The restoration of democracy in Greece following the 1974 collapse of the military junta enabled Kalamata's integration into national modernization efforts, with the city undergoing urbanization as its population grew from approximately 40,000 in the mid-1970s to over 50,000 by the 1980s, driven by internal migration and economic opportunities in trade and services.[34] Greece's accession to the European Economic Community in 1981 facilitated access to structural funds, which supported infrastructure enhancements in the Peloponnese, including road networks connecting Kalamata to Athens and upgrades to its port facilities, contributing to a period of relative prosperity through the 1980s.[35] A major setback occurred on September 13, 1986, when a magnitude 6.2 earthquake epicentered near Kalamata caused 22 fatalities, injured hundreds, and inflicted severe damage on unreinforced masonry structures, exposing deficiencies in building codes and seismic retrofitting that amplified casualties despite the moderate intensity.[36] Reconstruction was aided by European Regional Development Fund grants totaling about 5 million ECU (55% of eligible costs), which funded housing and public works, though delays in implementation highlighted bureaucratic inefficiencies in post-disaster response.[37] The event underscored Kalamata's location in a high-seismic zone along the Hellenic Arc, prompting incremental improvements in urban planning but persistent vulnerabilities due to aging infrastructure. The 1990s and early 2000s saw continued EU-financed development, including expansions at Kalamata International Airport to handle increased charter flights, bolstering tourism and exports amid Greece's pre-crisis growth spurt. The 2009 sovereign debt crisis, rooted in chronic fiscal deficits and public spending exceeding 50% of GDP, disrupted this trajectory in Kalamata through a sharp tourism downturn—visitor arrivals nationwide fell by over 10% annually from 2010-2012—leading to localized unemployment rates exceeding 20% and prompting emigration of young professionals abroad for better prospects.[38] [39] This outflow, peaking at net migration losses of around 100,000 Greeks yearly by 2015, reflected deeper policy failures in debt management and over-reliance on state employment, though remittances from expatriates provided some economic stabilization. In response to austerity-induced stagnation, recent initiatives emphasize privatization to foster efficiency; in December 2024, a Fraport-led consortium secured a 30-year concession for Kalamata Airport, pledging $29.7 million in terminal and runway upgrades to enhance capacity and operational reliability, contrasting with prior state-managed underinvestment.[40] These reforms, part of broader Greek efforts to concessionalize 22 regional airports by 2025, aim to leverage private capital for resilience against cyclical shocks, while seismic monitoring and zoning updates address ongoing earthquake risks evidenced by minor tremors in the 2010s.[41]Government and administration

Municipal organization

The Municipality of Kalamata was formed in 2011 under the Kallikratis Programme, a national administrative reform that merged former municipalities to streamline local governance and reduce the total number of units across Greece.[42] It encompasses four municipal units—Kalamata, Thouria, Aris, and Arfara—spanning 440.3 km² and incorporating urban, suburban, and rural areas from the pre-reform entities of Kalamata, Thouria, Arfara, and parts of adjacent communities.[43] [44] The core municipal unit of Kalamata, with an area of 253.2 km² and housing approximately 66,135 residents as of the 2021 census, includes the city center and suburbs such as Verga, Alagonia, and Artemisia, organized into local communities for localized administration.[45] [46] The remaining units—Thouria, Aris, and Arfara—primarily cover peri-urban and agricultural zones, with populations contributing to the municipality's total of 72,906 inhabitants in 2021, enabling coordinated services like infrastructure maintenance across diverse terrains.[43] Governance follows the standard structure for Greek second-degree municipalities: an elected mayor heads the executive, supported by a municipal council of 33 members (scaled to population over 50,000), a financial committee, and executive bodies handling operations such as urban planning and public works.[42] Athanasios Vasilopoulos has served as mayor since 2019, securing re-election in October 2023 with a coalition emphasizing local development, amid a voter turnout reflecting 97.10% valid ballots from 66,942 registered.[47] [48] Fiscal operations depend heavily on state allocations via Central Autonomous Funds, which provide annual grants for core functions, augmented by limited local revenues from property taxes, fees, and EU projects, constraining autonomy as municipalities generate under 30% of budgets independently in practice.[42] [49] This structure has facilitated decentralized service delivery, including waste management through municipal crews maintaining systems in outer units, though broader inefficiencies in revenue collection persist due to centralized oversight.Regional significance

Kalamata functions as the administrative capital of the Messenia regional unit within the Peloponnese, serving as the central hub for coordinating regional services, including agriculture and tourism initiatives that underpin the local economy. This role extends to overseeing infrastructure and development projects that benefit the broader Messenian population, estimated at around 143,000 residents as of recent census data, with Kalamata concentrating processing, distribution, and export activities for key products like olives and olive oil.[50][51] The city hosts significant judicial institutions, including the primary courts for the regional unit, handling legal proceedings that extend beyond municipal boundaries to cover Messenia's rural and coastal areas. Educationally, Kalamata accommodates branches of the University of the Peloponnese, offering programs in fields such as agriculture and engineering that train professionals for regional needs, alongside the legacy facilities of the former Technological Educational Institute of Peloponnese.[52][53] Kalamata's port facilitates the export of agricultural goods, contributing to the regional unit's GDP through trade volumes that support Messenia's position as a leading producer of olives and related products in the Peloponnese; export values from the municipality rose by 25% in recent assessments, underscoring its logistical centrality despite national averages for export-to-GDP ratios remaining below benchmarks.[54] Amid Greece's sovereign debt crisis (2009–2018), which contracted national GDP by over 25%, Messenia under Kalamata's hub maintained relative economic stability via resilient agricultural output, avoiding the sharp industrial declines seen elsewhere. Critiques of Greece's centralized governance, as outlined in OECD analyses, point to overconcentration of decision-making in Athens as a factor limiting decentralized innovation and rural adaptability in units like Messenia, potentially constraining localized responses to fiscal pressures.[55]Demographics

Population statistics

According to the 2021 Population-Housing Census conducted by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT), the Municipality of Kalamata recorded 72,906 permanent residents, encompassing the city proper and surrounding communities.[54][7] The municipal unit of Kalamata, which includes the urban core, had 66,135 inhabitants, while the densely settled city proper stood at 57,706 to 58,816 depending on delineation boundaries.[56] This reflects a modest annual growth rate of 0.61% from the 2011 census, when the municipality totaled 69,849 residents.[56] Historical census data indicate episodic spikes driven by migration. In 1991, the city proper population was approximately 43,625, with subsequent urbanization contributing to steady increases into the early 21st century.[57] A notable surge occurred in the 1920s following the Greco-Turkish population exchange of 1923, as Kalamata absorbed refugees from Asia Minor and eastern Thrace, bolstering local numbers amid national resettlement efforts; precise local increments from this era remain tied to broader regional inflows estimated in the tens of thousands for Messenia prefecture. Post-2009 Greek debt crisis emigration tempered national growth but spared Kalamata relative stagnation, as internal rural exodus from Messenia's depopulating villages offset outflows, maintaining urban density below national averages at around 286 residents per square kilometer in the municipal unit.[56] Demographic trends reveal an aging structure, with Greece's total fertility rate (TFR) hovering below replacement at 1.3-1.4 births per woman in recent years—patterns mirrored locally through ELSTAT age distributions showing contraction in the 0-15 cohort and expansion among those over 65.[58] This yields a dependency ratio strained by fewer working-age contributors, exacerbated by youth emigration during the crisis. Empirical projections, extrapolated from national models, forecast Kalamata's population stagnating or contracting slightly to under 72,000 by 2030 absent net positive migration, aligning with Greece's anticipated decline to 9.7 million overall amid persistent sub-replacement fertility projected at 1.5 by 2050.[59][60] Such dynamics underscore rural-to-urban shifts as a stabilizing factor, countering myths of urban overcrowding given Messenia's low regional density of 37 inhabitants per square kilometer.[61]| Census Year | Municipality Population | Growth Rate (from prior decade) |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 69,849 | - |

| 2021 | 72,906 | +4.4% |