Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Qara Khitai

View on Wikipedia

The Qara Khitai, or Kara Khitai (simplified Chinese: 哈剌契丹; traditional Chinese: 喀喇契丹; pinyin: Kālā Qìdān or Chinese: 黑契丹; pinyin: Hēi Qìdān; lit. 'Black Khitan'),[5] also known as the Western Liao (Chinese: 西遼; pinyin: Xī Liáo), officially the Great Liao (Chinese: 大遼; pinyin: Dà Liáo),[6][7] was a dynastic regime based in Central Asia ruled by the Yelü clan of the Khitan people.[8] Being a rump state of the Khitan-led Liao dynasty, Western Liao was culturally Sinicized to a large extent, especially among the elites consisting of Liao refugees.[8][9][10]

Key Information

The dynasty was founded by Yelü Dashi (Emperor Dezong), who led the remnants of the Liao dynasty from Manchuria to Central Asia after fleeing from the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty conquest of northern China. The empire was usurped by the Naimans under Kuchlug in 1211; traditional Chinese, Persian, and Arab sources consider the usurpation to be the end of the dynasty,[11] even though the empire would not fall until the Mongol conquest in 1218. Some remnants of the Qara Khitai would form the Qutlugh-Khanid dynasty in southern Iran.

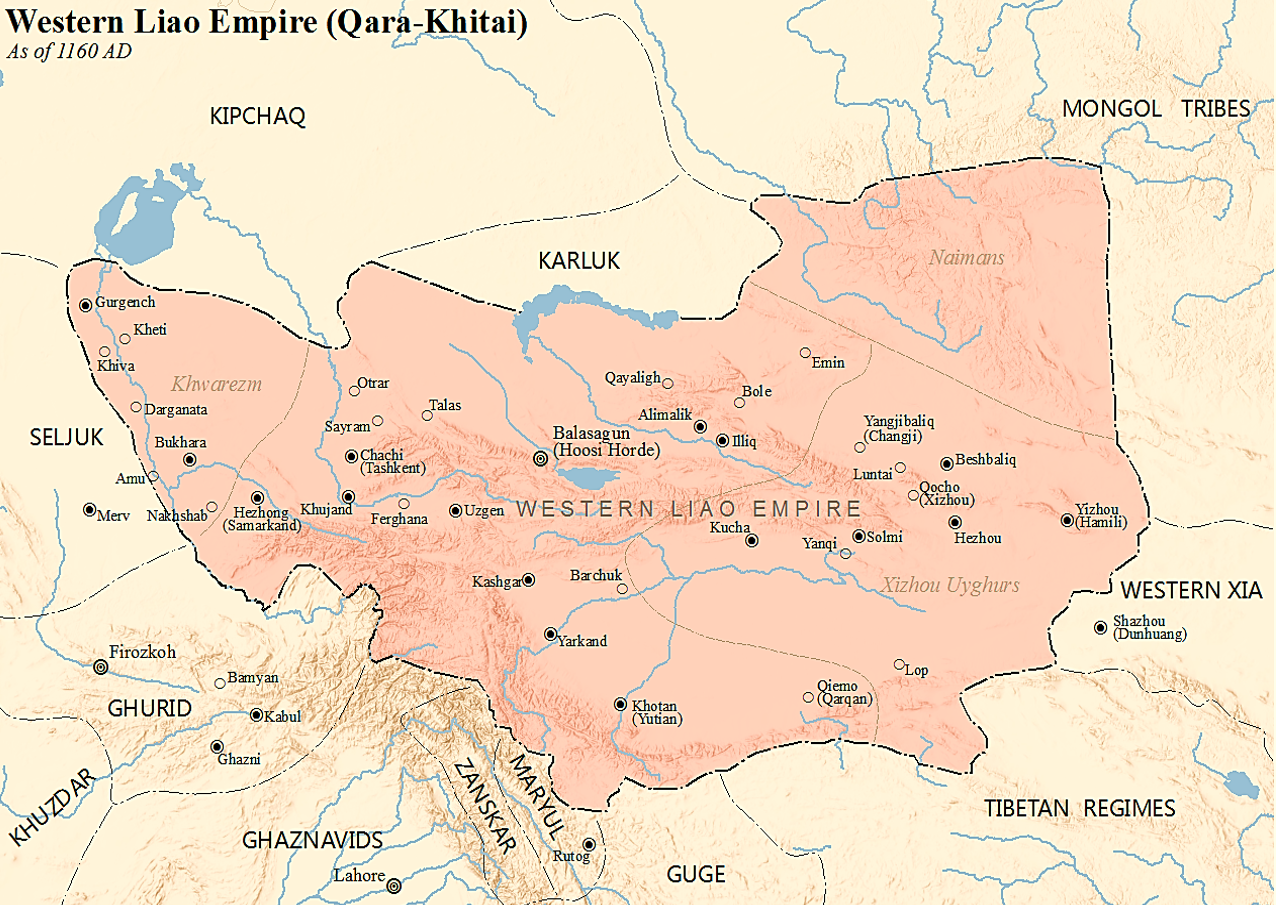

The territories of the Qara Khitai corresponded to parts of modern-day China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The Anushtegin dynasty, the Karluks, Qocho kingdom, the Kankalis, and the Kara-Khanid Khanate were vassal states of the Qara Khitai at some point in history. Chinese and Muslim historiographical sources, such as the History of Liao, considered the Qara Khitai to be a legitimate Chinese dynasty.[12][13]

Names

[edit]In 1124, the Qara Khitai established by Yelü Dashi continued to use the Chinese dynastic name of "Great Liao".[7][14][15] In historiography, however, this regime is more commonly called the "Western Liao" or "Qara Khitai". The Qara Khitans used neither "Western Liao" or "Qara Khitai" to refer to themselves. They regarded themselves as the legitimate continuation of the Liao dynasty and continued to use the Khitan name "Great Liao Khitan" ("Great Liao" in Chinese) as their self designation. Western Liao is a Chinese designation and Qara Khitai is a Turko-Mongol term. "Qara Khitai" cannot be found in any Muslim sources before the Mongol invasions, after which Turko-Mongol speakers mistook the word for "Liao" (Hura) as qara (black).[16] "Qara Khitai" became a common Central Asian name for the state and it is often translated as the "Black Khitans" according to the Turko-Mongol understanding of qara.[17] "Black Khitans" (黑契丹) has also been seen used in Chinese. "Qara", which literally means "black", corresponds with the Liao's dynastic color black and its dynastic element water, according to the theory of five elements (wuxing).[18] Muslim historians initially referred to the state as "Khitai", which may have come from the Uyghur form of "Khitan", in whose language the final -n or -ń became -y. They adopted the name "Qara Khitai" after the Mongol invasions.[19][20]

Due to the dominance of the Khitans during the Liao dynasty in Northeast China and Mongolia and later the Qara Khitai in Central Asia where they were seen as Chinese, the term "Khitai" came to mean "China" to people near them in Central Asia, Russia and northwestern China. The name was then introduced to medieval Europe via Islamic and Russian sources, and became "Cathay". In the modern era, words related to Khitay are still used as a name for China by Turkic peoples, such as the Uyghurs in China's Xinjiang region and the Kazakhs of Kazakhstan and areas adjoining it, and by some Slavic peoples, such as the Russians and Bulgarians.[21]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]The Qara Khitai empire, also known as the Western Liao dynasty, was the remnant offshoot of the Khitan-led Liao dynasty. From 1114 to 1125, the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty conquered the Liao. In 1122, two groups of Khitans fled westward to escape the Jin invasion. One of these groups was led by Yelü Dashi, who joined the Liao emperor, Tianzuo, at the border of the Western Xia kingdom. Dashi was captured by the Jin in 1123 and forced to lead them to Tianzuo's camp, resulting in the capture of the entire Liao imperial family except for Tianzuo and one of his sons. Dashi later rejoined Tianzuo but the emperor was captured in early 1125 and died at the Jin court in 1128.[22]

Founding of the Qara Khitai

[edit]

In 1124, Yelü Dashi fled northwest and established his headquarter at the military garrison of Kedun (Zhenzhou) on the Orkhon River. Dashi secured the allegiance of the garrison forces numbering 20,000 and set himself up as gurkhan (universal khan).[23] He conquered two Jin tribes in 1129.[24] In 1130, Dashi led his host further west in search of new territory, whereupon he settled a town and his first base by the Emil river.[25] Within a year, he had established himself as suzerain of Qocho and gained a foothold in Transoxiana. In 1131, he attacked the Karakhanids at Kashgar but was repelled.[23][26] Later though, after being occupied by Yelü Yudu in the east[27], he returned and strengthened his forces to eventually expand his authority in Qayaliq and Almaliq regions.[28] In 1134 he conquered the Karakhanid city of Balasaghun (in modern Kyrgyzstan), resulting in the vassalization of the nearby Kankalis, Karluks, Kyrgyz, and the Kingdom of Qocho. Kashgar, Khotan, and Beshbalik. In 1137, he defeated the Western Karakhanids near Khujand and annexed Fergana and Tashkent. Yelü Dashi's host was further bolstered by 10,000 Khitans who had previously been subjects of the Karakhanids. They went on to conquer Kashgar, Khotan, and Beshbalik.[29][2]

Battle of Qatwan

[edit]The Western Karakhanids were vassals of the Seljuk Empire and the Karakhanid ruler Mahmud II appealed to his Seljuk overlord Ahmad Sanjar for protection. In 1141, Sanjar with his army arrived in Samarkand. The Khitans were invited by the Khwarazmians (also a vassal of the Seljuks) to conquer the lands of the Seljuks and responded to an appeal to intervene by the Karluks who were involved in a conflict with the Karakhanids and Seljuks.[30]

Khitan forces ranging from 20,000 to 700,000 depending on the source met in battle with Seljuk forces numbering 100,000.[31][32][33] While many Muslim sources suggested that the Khitan forces greatly outnumbered the Seljuks, some contemporary Muslim authors also reported that the battle was fought between forces of equal size.[34] The Khitans were also said to have been given a reinforcement of 30,000–50,000 Karluk horsemen.[35]

The Battle of Qatwan took place on the Qatwan steppe, north of Samarkand, on 9 September 1141.[36][37] The Khitans attacked the Seljuk forces simultaneously, encircled them, and forced the Seljuq center into a wadi called Dargham, about 12 km from Samarkand. Encircled from all directions, the Seljuq army was destroyed and Sanjar barely escaped. Figures of the dead ranged from 11,000 to 100,000.[38] Among those captured at the battle were Seljuq military commanders and Sanjar's wife.[38] The Seljuk defeat resulted in the loss of all of Transoxiana to the Khitans.[2]

After his victory, Yelü Dashi spent 90 days in Samarkand, accepting the loyalty of Muslim nobles and appointing Mahmud's brother Ibrahim as the new ruler of Samarkand. Dashi allowed the Muslim Burhan family to continue to rule Bukhara. After this battle, Khwarazm became a vassal state of the Khitans. In 1142, Dashi sent Erbuz to Khwarazm to pillage the province, which forced Atsiz to agree to pay 30,000 dinars annual tribute.[38]

Territorial extent

[edit]The Qara Khitai in 1143 constituted a realm encompassing a territory roughly equivalent to modern Xinjiang, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and south Kazakhstan. Under the empire's direct rule was the region around their capital, Balasagun. Around it were the subject kingdoms of Qocho, the eastern and western Karakhanids, Khwarazm, and the Karluk tribes. Its western border was defined by the Amu Darya, but the Khitans were active in Khorasan until the 1180s while Balkh remained under their rule until 1198. In the north they bordered the Yenisei Kyrgyz north of Lake Balkhash until 1175 when they retreated further south. The southern boundary stretched from Balkh to Khotan to Hami. The boundary of the empire in the east is hard to define but the Khitans exercised some sovereignty over the Naimans east of the Altai Mountains until 1175.[39]

Conflict with Jin

[edit]Simultaneously during the invasion of Central Asia, Dashi also sent invasion forces to attack the Jin and retake Liao territory, however these efforts proved fruitless and ended in defeat.[40][41] Yelü Dashi had originally hoped to recapture northern China from the Jin dynasty and restore the territories once held by the Liao dynasty.[42][43] However, he soon discovered the relative weakness of his empire vis-a-vis the Jin dynasty and gave up the idea[43] after a disastrous attack on the Jin dynasty in 1134.[44] The Western Liao continued to defy Jin supremacy in 1146, and continued sending scouts and small military units against the Jin in 1156, 1177, 1185, 1188. This indicates that for the first 2 generations there remained considerable interest in reconquest.[45]

Xiao Tabuyan (r. 1143-1150)

[edit]

When Yelü Dashi died, his wife and paternal cousin, Xiao Tabuyan (1143-1150), became regent for their son. Tabuyan used the honorific titles of empress Gantian, Gurkhan, and Dashi. Her successors retained the titles of Gurkhan and Dashi. While the History of Liao states that Tabuyan was merely a regent, Muslim sources state that she held unlimited power over the realm as is implied by her titles.[46]

Taking advantage of Dashi's death, the Oghuz invaded Bukhara but were likely driven off sometime before 1152, when they were located in Khuttal and Balkh. In 1143, the Seljuk sultan Ahmad Sanjar attacked Khwarazm and occupied Khorasan. Although Atsiz once again became a Seljuk subject, in practice he continued to pay tribute to the Qara Khitai. According to Ibn al-Athir, Atsiz was only spared due to Sanjar's fear of the Khitans. Sanjar may have also wielded power in Transoxiana until his death, as implied by an 1148 coin minted in Bukhara. In 1144, Qocho offered tribute to the Jin. The Jin sent a messenger named Niange Hannu to the Qara Khitai. When he met Tabuyan in 1146, he refused to dismount in her presence and proclaimed that he had come from a superior court as an emissary of the Son of Heaven and demanded her to show obeisance to the Jin court. When he threatened that the Jin were ready to send an army to invade their lands, the empress executed him. His fate only became known to the Jin in 1175 as a result of deserters from the Qara Khitai.[47]

Yelü Yilie (r. 1150-1163)

[edit]

The son, Yelü Yilie, ruled from 1150 to 1163. The only known act he was involved in according to the History of Liao during his 13 year reign was taking a census of people over 18 years old. The result was 84,500 households in total. The small number, less than Samarkand's 100,000 households in the pre-Mongol era, was likely due to being geographically limited to only Balasagun and the surrounding area that the Khitans directly ruled. It is unknown if even the sedentary population was counted in the census.[48]

During Yilie's reign, the Oghuz rebelled against Ahmad Sanjar in Khorasan. The Khitans were at least partly responsible for this due to displacing the Oghuz in Transoxiana and pushing them into Balkh, where they were heavily taxed by Sanjar due to his losses at Qatwan. The Oghuz rebellion was caused by the governor of Balkh, Amir Qumach, who had enlisted Oghuz support against the Ghurids in 1152. However the Oghuz defected to the Ghurids, allowing them to temporarily occupy Balkh. After retaking the city, Qumach increased the tax burdens on the Oghuz. In 1153, the Oghuz killed a Seljuk tax collector and Qumach retaliated by attacking them. In the conflict that followed, Qumach and his sons were killed, and Sanjar was defeated and captured. The Oghuz plundered Khorasan, while Sanjar escaped captivity in 1156 but failed to restore his former authority. He died the following year.[49]

There is no evidence that the Khitans were directly involved in the conflict of Khorasan, however the Turkic leaders all paid tribute to them to gain their favor during this time. The lack of Khitan involvement may be due to conflict with the Jin to the east. In 1156, a Jin army led by Po Longdun met with a Qara Khitan raiding group several hundred strong at Kedun. The Khitan force withdrew after negotiations. Khitans under Jin rule rebelled in 1161. One of the rebel leaders, Saba, planned to defect to the Qara Khitai, but was killed by another Khitan leader, Yelü Wowo, who proclaimed himself the new Khitan emperor. Wowo was killed by the Jurchens in 1163.[50]

The Qara Khitai played a key role in the conflict between their vassals: the Karluks, Karakhanids, and Khwarazm. In early 1156, the Karluks killed Ibrahim Tabghach Khan, the Western Karakhanid ruler of Samarkand. Ibrahim was succeeded by his son, Mahmud, for a year before Ibrahim's brother, Ali Chaghri Khan, took power. Ali wanted to avenge his brother and soon after his accession, killed one of the Karluk leaders. In early 1156, the Karluks fled to Khwarazm and sought the help of its ruler, Il-Arslan, who sent an army against Samarkand. Ali sent for help from his sovereign, the Qara Khitai, who instructed the ruler of the Eastern Karakhanids to come to his aid. The Eastern Karakhanids sent 10,000 riders to reinforce Samarkand, however the Khwarazmian force was too large to comfortably engage, and a truce was achieved with the help of religious dignitaries. The Karluks were reinstalled to their former posts and Il-Arslan returned to Khwarazm. The Karluks continued to cause trouble for Samarkand until the Qara Khitai ordered the Western Karakhanids to drive them from Bukhara and Samarkand to Kashgar. Mas'ud Tabghach Khan, the brother of Ibrahim, took the occasion to purge Transoxiana of the Karluks.[51]

Yelü Pusuwan (r. 1164–1177)

[edit]

Yelü Pusuwan (r. 1164–1177) was explicitly chosen for succession by her brother, Yelü Yilie. Known as Empress Chengtian, Pusuwan refocused the Qara Khitai's attention westward. In 1165, the Qara Khitai participated in Mas'ud Tabghach Khan's invasion of Balkh and Andkhud, then under Oghuz domination, and incorporated Balkh under Qara Khitai rule lasting until 1198. In 1172, the Qara Khitai crossed the Amu Darya to attack Khwarazm, whose ruler Il-Arslan had neglected to pay tribute. Il-Arslan fell ill on the way to battle and let a Karluk commander lead his forces while he remained behind. The Khwarazmian army was soundly defeated and Il-Arslan returned to Khwarazm where he died in March 1172. However no new tribute collection agreement was enforced, possibly due to satisfaction from the spoils that the Qara Khitai had already collected from their victory.[52]

Il-Arslan's death led to a succession struggle between his two sons in which the Qara Khitai were involved. The younger son, Sultan Shah, was enthroned with the aid of his mother, Terken Khatun, who ruled in his name. The older brother, Tekish, fled to the Qara Khitai court and asked for their support in installing him as the new ruler of Khwarazm in return for a share of its treasures and annual tribute. Pusuwan sent her husband, Xiao Duolubu, with a large army to support Tekish's claim. Sultan Shah and his mother fled Khwarazm and Tekish was enthroned on 11 December 1172. Terken Khatun enlisted the help of Mu'ayyid al-Din Ai-Aba, a former Seljuk amir, to fight for their cause. However he was defeated and executed in Khwarazm in July 1174. Sultan Shah and his mother then fled to Dihistan, which Tekish then conquered and put to death Terken Khatun. Sultan Shah fled to Tughan Shah, the son of Mu'ayyid, in Nishapur, and then to the Ghurids.[53]

Tekish soon fell out with the Qara Khitai. Despite owing his crown to them, Tekish found the conduct of their emissaries to be insulting and their demands exceeding the original agreement. In the mid 1170s, Tekish killed the leader of the emissaries who was part of the Qara Khitai royal family, and ordered the Khwarazmian notables (ayan) to kill every Qara Khitai who entered Khwarazm. Pusuwan summoned Sultan Shah, who had already been in contact with the Qara Khitai court after realizing the Ghurids would not challenge Tekish for his claim, and sent a large army with him led by her husband to oust Tekish.[54]

During the conflict with Khwarazm, the Qara Khitai also faced rebellions by tribes to the north and east. In the early 1170s, the Qara Khitai sent an imperial son-in-law named Abensi against the Yebulian and other tribes in the north. Abensi could not defeat them and the conflict lasted until 1175. In the same year, the Naimans and Kangly surrendered to the Jin. In 1177, the Qara Khitai sent spies into Jin territory and news of them reached the Jin court. In response, the Jin resettled the Khitans in the northwest to the northeast. In addition, the border market of Suide was closed due to fear that it was being used as a hub for spies.[55]

While her husband was away, Pusuwan developed a romantic relationship with his brother, Xiao Fuguzhi. She planned to get rid of her husband in order to spend more time with his brother, however her father-in-law caught wind of her plans and conducted a coup. Xiao Wolila surrounded the palace with his troops and killed both his son and the empress.[54]

Yelü Zhilugu (r. 1177-1211)

[edit]Khwarazm war

[edit]Xiao Wolila installed Yelü Zhilugu (r. 1178–1211), the second son of Yelü Yilie, on the throne.[56]

At the time of Zhilugu's accession, a large Qara Khitai army under the command of the late empress's husband, Xiao Duolubu, was accompanying Sultan Shah to Khwarazm. Tekish managed to halt the Qara Khitai advance by flooding the Amu Darya's dikes and blocking their path. Xiao Duolubu decided to retreat but Sultan Shah offered him a large sum in return for leaving part of his troops behind. These troops accompanied Sultan Shah to fight against the Oghuz in Khorasan. In 1181, they helped him seize Merv, Sarakhs, Nasa, and Abiward.[57]

In 1181, the Kipchaks under Qara Ozan Khan, established in a marriage alliance with Tekish, attacked Talas in Qara Khitai territory.[58]

In 1182, Tekish attacked Bukhara. According to his own description, the city dwellers preferred the rule of non-believers to his Muslim army. Tekish captured the city but it is uncertain how long he held it. The lack of references as well as dismissive portrayal of his time there, referred to as "the business in Transoxania",[59] probably implies a short duration. By 1193, Bukhara was again ruled by the Karakhanid vassal of the Qara Khitai. Praises of Ibrahim Arslan Khan, the Karakhanid ruler, were sung by the Bukharan sadr around this time.[59]

The conflict between Tekish and his brother Sultan Shah continued in Khorasan until 1193 when Sultan Shah died. Although Tekish took precautions to guard the Amu Darya against Qara Khitai support of his brother during the conflict, the Qara Khitai offered no further responses to the matter. It is likely that there was a rapprochement between Tekish and the Qara Khitai court before 1194 and at the very latest before 1198, when the Qara Khitai aided Tekish against the Ghurids. The cessation of hostilities was probably a financial agreement as several Muslim sources assert that Tekish dutifully paid tribute to the Qara Khitai and ordered his son to continue to do so.[60]

Tribal conflict

[edit]In the east, there is some vague evidence according to Song dynasty spy reports that the Qara Khitai had tried to ally with the Tangut Western Xia dynasty to attack the Jin in 1185. Although nothing came of it, the Jin evidently took the Qara Khitai threat seriously. In 1188, Wanyan Xiang, a leading Jin official, came back from a tribute collecting mission among the northern tribes and presented to the emperor a detailed program and map to prevent their subjects from defecting to the Qara Khitai. Wanyan Xiang was promoted for his contributions. In 1190, one of the Qara Khitai subject tribes surrendered to the Jin, which may have been the result of this new policy.[61]

In the early 1190s, the khan of the Keraites, Toghrul, fled to the Qara Khitai seeking military support after he was ousted by his own family. When no support was forthcoming, Toghrul returned to Mongolia in 1196 seeking Temüjin's help. Toghrul later made an alliance with the Jin, through which he received his other title, Ong Khan, in 1197.[62]

Ghurid war

[edit]In 1198, Muhammad of Ghor, one of the Ghurid rulers, seized Balkh from the vassal of the Qara Khitai. The Qara Khitai were urged by the Khwarazm Shah Tekish (who was also in conflict with the Ghurids) not to let this slide, as the other Ghurid ruler Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad would seize Khwarazm and Transoxiana. The Qara Khitai invaded Ghurid lands around Kurzuban (around modern Taloqan). At first they were victorious, killing and capturing many Ghurid soldiers, but they were surprised by an attack in the night. When Ghiyath al-Din's reinforcements arrived in the morning, the Qara Khitai army was badly defeated, suffering 12,000 losses. The Qara Khitai turned to Tekish for compensation for the damage incurred and sent Xiao Duolubu to Khwarazm to collect. Tekish in turn asked the Ghurids for help. Ghiyath al-Din agreed to help with the compensation on the condition that Tekish offered his obedience to the Caliph and returned territories taken earlier by the Qara Khitai. As a result, Khwarazm managed to provide some manner of compensation to the Qara Khitai for their losses incurred fighting against the Ghurids, using Ghurid funds. Tekish died in 1200 and his son Muhammad II of Khwarazm started his reign as a tributary of the Qara Khitai.[63]

The Ghurids took advantage of Tekish's death to conquer certain parts of Khorasan, including Merv and Sarakhs, where they installed Hindu Khan, Muhammad II's nephew, as their subject. In September 1201, Muhammad II marched on Merv. Hindu Khan tried to escape to the Qara Khitai, but he was killed before reaching them. Muhammad II's conflict with the Ghurids in Khorasan continued for several years. In 1204, Muhammad of Ghor attacked Khwarazm directly. Muhammad II hurried back to Khwarazm and opened the dikes and burned the meadows in an effort to slow the Ghurid advance. The Khwarazmian forces suffered a heavy defeat against the Ghurids near a canal east of Gurganj and Muhammad II fled to the Qara Khitai. The Qara Khitai sent to his aid a force of 10,000 or 40,000 led by Tayangu and the Karakhanid rulers Uthman ibn Ibrahim and his cousin Taj al-Din Bilge Khan, the ruler of Otrar. The Ghurids retreated south upon receiving news of Qara Khitai reinforcements.[64]

The sequence of events after the Ghurid retreat is unclear. One version of events has the Ghurids being pursued by Khwarazmian forces until they fell into Qara Khitai hands. Another version states that the Ghurids first won a victory against the Qara Khitai before being overtaken from exhaustion. According to another version, the Ghurids split their forces while fleeing from the Khwarazmian army and the Qara Khitai caught them in the desert. The Qara Khitai then attacked the Ghurids with 20,000 horsemen while a strong wind blowing towards the Ghurids resulted in a Qara Khitai victory. All versions of events, however, agree that the Qara Khitai chased the Ghurids to Andkhud, a village between Merv and Balkh, where Muhammad of Ghor took refuge in a castle. As the Qara Khitai were about to capture him, Uthman intervened and negotiated the Ghurids' surrender. This act has been attributed to solidarity between Muslim leaders. According to one account, Uthman advised the Ghurids to move their forces in and out of the castle by night to create the appearance of reinforcements arriving, thereby boosting their negotiating position. Tayangu and the Qara Khitai agreed to let Muhammad of Ghor go in return for a ransom payment. According to one account, the payment was everything Muhammad of Ghor had in his possession, while another account states that the payment was much more modest, consisting of one elephant and an additional payment. The Ghurids kept Balkh and the Amu Darya was agreed upon as the border between the two realms.[65]

Muhammad of Ghor later returned to avenge himself against the Qara Khitai. In the summer of 1205, the Ghurid viceroy in Balkh seized Tirmidh and destroyed a Qara Khitai army stationed there. Plans were underway for a bridge to be built across the Amu Darya to facilitate a Ghurid invasion of Transoxiana. However before any of this came to fruition, Muhammad of Ghor was killed on 13 March 1206 and the Ghurid invasion came to an end.[66]

Rise of Khwarazm

[edit]Muhammad II of Khwarazm convinced the governor of Tirmidh to surrender and returned it to Qara Khitai control. In return, the Qara Khitai recognized the Khwarazm Shah's suzerainty over all of Khorasan.[67]

Muhammad II saw the Qara Khitai's recognition of his claims as a sign of weakness and started interfering in Transoxiana in 1207 when Sanjar, son of a shield maker, revolted against local leadership in Bukhara. Representatives of the Burhan family, who were responsible for tax collection, went to the Qara Khitai court for help. While the Qara Khitai reaffirmed the Burhan family's position, they offered no concrete assistance. In the absence of Qara Khitai backing, the notables of Bukhara and Samarkand sought out Muhammad II for help. Before challenging the Qara Khitai, Muhammad II made preparations by compromising with the Ghurids on certain domains and enlisting the aid of the Karakhanid ruler Uthman ibn Ibrahim, who had been insulted by the Qara Khitai's refusal to grant him a royal princess in marriage.[68]

In 1207, Muhammad II entered Bukhara and exiled Sanjar to Khwarazm. The Qara Khitai sent an army against him and warfare continued for some time before Tort-Aba, the new Khwarazmian commissioner in Samarkand, and the isfahbad of Kabud-Jama (in Tabaristan) defected to the Qara Khitai. Both sides retreated but the Qara Khitai took many captives. There are accounts that Muhammad II was actually taken captive at one point but was not recognized and released.[69]

During Muhammad II's absence, his brother Ali Shah (viceroy in Tabaristan) and Kozli (commander in Nishapur) had tried to set themselves up as rulers of Khorasan. When Muhammad II returned, Kozli fled and both he and his son were killed soon after, and Ali Shah fled to Firuzkuh. Muhammad II restored his position in Khorasan by conquering Herat and Firuzkuh. In 1208-9, Ali Shah was executed. Khwarazm returned to paying tribute to the Qara Khitai in 1209-10 when Muhammad II was planning a campaign against the Kipchaks. Not wanting to sever relations with the Qara Khitai at that moment, Muhammad II left the matter of tribute to his mother, who welcomed the Qara Khitai emissaries with great respect. However Mahmud Tai, the Qara Khitai's chief vizier, was unconvinced and reported that Muhammad II was unlikely to pay tribute again.[70]

Late in the period it expanded far to the south as the Khwarezmian Empire until it was conquered by the Mongols in 1220, two years after the Qara Kitai. In the south the Kara-Khanid vassals were lightly held and engaged in various conflicts with each other, the Qara Kitai, Khwarezm and the Gurids.[71]

Rebellions in the east

[edit]In 1204, the Qara Khitai put down a rebellion in Khotan and Kashgar. In 1209, Qocho rebelled against the Qara Khitai. The Qara Khitai commissioner was chased into a high building where he was put to death. The Uyghur ruler, Barchuq Art Tegin, reported the incident to the Qara Khitai, but at this point individuals at Qocho had already started defecting to the Mongols. When Genghis Khan's messengers arrived at Qocho, the Uyghur ruler offered his allegiance to the Mongol khan. Genghis gave Barchuq his daughter in return for his attendance at court as well as a sizable tribute. In late 1209 or early 1210, when Merkit refugees arrived in Qocho, Barchuq attacked them and drove them off. He made haste to report his loyal behaviour to Genghis, accompanying it with tribute. In 1211, the Uyghur Idiqut had an audience with Genghis on the Kerulen River. In the same year, another vassal of the Qara Khitai, the Karluk Arslan Khan surrendered to Genghis.[72]

Kuchlug's usurpation and end of the Khanate

[edit]In 1208, a Naiman prince, Kuchlug, fled his homeland after being defeated by Mongols. Kuchlug was welcomed by the Qara Khitai, and was allowed to marry Zhilugu's daughter. However, in 1211, Kuchlug revolted, and later captured Yelü Zhilugu while the latter was hunting. Zhilugu was allowed to remain as the nominal ruler but died two years later, and many historians regarded his death as the end of the Qara-Khitai empire. In 1216, Genghis Khan dispatched his general Jebe to pursue Kuchlug; Kuchlug fled, but in 1218, he was finally captured and decapitated. The Mongols fully conquered the former territories of the Qara-Khitai in 1220.

Aftermath

[edit]

The Qara Khitais became absorbed into the Mongol Empire; a segment of the Qara-Khitan troops had previously already joined the Mongol army fighting against Kuchlug. Another segment of the Qara-Khitans, in a dynasty founded by Buraq Hajib, survived in Kirman as a vassal of the Mongols, but ceased to exist as an entity during the reign of Öljaitü of the Ilkhanate.[73] The Qara-Khitans were dispersed widely all over Eurasia as part of the Mongol army. In the 14th century, they began to lose their ethnic identity, traces of their presence however may be found as clan names or toponyms from Afghanistan to Moldova. Today a Khitay tribe still lives in northern Kyrgyzstan.[19]

Qara Khitai is mentioned on the Asia map of Nicolas and Guillaume Sanson of 1669.[74]

Administration

[edit]The Khitans ruled from their capital at Balasagun (in today's Kyrgyzstan), directly controlling the central region of the empire. The rest of their empire consisted of highly autonomous vassalized states, primarily Khwarezm, the Karluks, the Kingdom of Qocho of the Uyghurs, the Kankalis, and the Western, Eastern, and Fergana Kara-Khanids. The late-arriving Naimans also became vassals, before usurping the empire under Kuchlug.[39]

The Khitan rulers inherited many administrative elements from the Liao dynasty, including the use of Confucian administration and imperial trappings. The empire also adopted the title of Gurkhan (universal Khan). The Khitans used the Chinese calendar, maintained Chinese imperial and administrative titles, gave its emperors reign names, used Chinese-styled coins, and sent imperial seals to its vassals.[75] Although most of its administrative titles were derived from Chinese, the empire also adopted local administrative titles, such as tayangyu (Turkic) and vizier.

The Khitans maintained their old customs, even in Central Asia. They remained nomads, adhered to their traditional dress, and maintained the religious practices followed by the Liao dynasty Khitans. The ruling elite tried to maintain the traditional marriages between the Yelü king clan and the Xiao queen clan, and were highly reluctant to allow their princesses to marry outsiders. The Qara-Khitai Khitans followed a mix of Buddhism and traditional Khitan religion, which included fire worship and tribal customs, such as the tradition of sacrificing a gray ox with a white horse. In an innovation unique to the Qara Khitai, the Khitans paid each of their soldiers a salary.

The empire ruled over a diverse population that was quite different from its rulers. The majority of the population was sedentary, although the population suddenly became more nomadic during the end of the empire, due to the influx of Naimans. The majority of their subjects were Muslims, although a significant minority practiced Buddhism and Nestorianism. Although Khitan was the languages of administration, Chinese also was important in the administration of Qara Khitai. The Uyghur might have been one of the administration's languages in the empire. Qara Khitai correspondence with the Muslims of Transoxania was wrilten in Persian and used Muslim formulas.[76]

Association with China

[edit]

In Chinese historiography, the Qara Khitai is most commonly called the "Western Liao" (西遼) and is considered to be an orthodox Chinese dynasty, as is the case for the Liao dynasty.[77] The history of the Qara Khitai was included in the History of Liao (one of the Twenty-Four Histories), which was compiled officially during the Yuan dynasty by Toqto'a et al.[77]

After the fall of the Tang dynasty, various dynasties of non-Han ethnic origins gained prestige by portraying themselves as the legitimate dynasty of China. Qara Khitai monarchs used the title of "Chinese emperor",[78][79] and were also called the "Khan of Chīn".[80] The Qara Khitai used the "image of China" to legitimize their rule to the Central Asians. The Chinese emperor, together with the rulers of the Turks, Arabs, India and the Byzantine Romans, were known to Islamic writers as the world's "five great kings".[81] Qara Khitai kept the trappings of a Chinese state, such as Chinese coins, Chinese imperial titles, the Chinese writing system, tablets, seals, and used Chinese products like porcelain, mirrors, jade and other Chinese customs. The adherence to Liao Chinese traditions has been suggested as a reason why the Qara Khitai did not convert to Islam.[82] Despite the Chinese trappings, there were comparatively few Han Chinese among the population of the Qara Khitai.[83] These Han Chinese had lived in Kedun during the Liao dynasty,[84] and in 1124 migrated with the Khitans under Yelü Dashi along with other people of Kedun, such as the Bohai, Jurchen, and Mongol tribes, as well as other Khitans in addition to the Xiao consort clan.[85]

Qara Khitai's rule over the Muslim-majority Central Asia has the effect of reinforcing the view among some Muslim writers that Central Asia was linked to China even though the Tang dynasty had lost control of the region a few hundred years before. Marwazī wrote that Transoxania was a former part of China,[86] while Fakhr al-Dīn Mubārak Shāh defined China as part of "Turkestan", and the cities of Balāsāghūn and Kashghar were considered part of China.[87]

Legacy

[edit]The association of Khitai with China meant that the most enduring trace of the Khitan's power is names that are derived from it, such as Cathay, which is the medieval Latin appellation for China. Names derived from Khitai are still current in modern usage, such as the Russian, Bulgarian, Uzbek and Mongolian names for China.[19] However, the use of the name Khitai to mean "China" or "Chinese" by Turkic speakers within China, such as the Uyghurs, is considered pejorative by the Chinese authorities, who tried to ban it.[88]

Seals

[edit]

In Autumn of the year 2019 a Chinese type bronze seal was discovered near a Caravanserai that was located near the Ustyurt Plateau.[89] This seal has a weight of 330 grams and has the dimensions of 50x52x13 millimeters with a handle that is 21 millimeters in height.[89] The inscription of the seal is written in Khitan large script and contains 20 characters.[89] This was the first seal that could be confidently attributed to the a Western Liao period as it is attributed to have been created during the 3rd month of the year Tianxi 20 (or the year 1197 in the Gregorian calendar) during the reign of Emperor Yelü Zhilugu.[89] The discovery of this seal further indicated that the Qara Khitai Khanate adopted the Chinese administrative practice, as such seals were commonly used in the Imperial Chinese government apparatus.[89]

As of 2020 it is unclear if the same regulations on seals existed in Qara Khitai as did in imperial China and if the sizes of Western Liao seals were standardised or not.[89]

Sovereigns of Qara Khitai

[edit]| Temple names (廟號 miàohào) | Posthumous names (諡號 shìhào) | Birth Names | Convention[citation needed] | Period of Reign | Era names (年號 niánhào) and their according range of years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dezong (德宗 Dézōng) | Emperor Tianyou Wulie (天祐武烈皇帝 Tiānyòu Wǔliè Huángdì) | Yelü Dashi (耶律大石 Yēlǜ Dàshí or 耶律達實 Yēlǜ Dáshí)1 | use birth name | 1124–1144 | Yanqing (延慶 Yánqìng) 1124 or 1125–1134 Kangguo (康國 Kāngguó) 1134–1144 |

| Not applicable | Empress Gantian (感天皇后 Gǎntiān Huánghòu) (regent) | Xiao Tabuyan (蕭塔不煙 Xiāo Tǎbùyān) | "Western Liao" + posthumous name | 1144–1150 | Xianqing (咸清 Xiánqīng) 1144–1150 |

| Renzong (仁宗 Rénzōng) | did not exist | Yelü Yilie (耶律夷列 Yēlǜ Yíliè) | "Western Liao" + temple name | 1150–1164 | Shaoxing (紹興 Shàoxīng) or Xuxing (Xùxīng 續興)2 1150–1164 |

| Not applicable | Empress Dowager Chengtian (承天太后 Chéngtiān Tàihòu) (regent) | Yelü Pusuwan (耶律普速完 Yēlǜ Pǔsùwán) | "Western Liao" + posthumous name | 1164–1178 | Chongfu (崇福 Chóngfú) 1164–1178 |

| did not exist | Mozhu (末主 Mòzhǔ "Last Lord") or Modi (末帝 Mòdì "Last Emperor") | Yelü Zhilugu (耶律直魯古 Yēlǜ Zhílǔgǔ) | use birth name | 1178–1211 | Tianxi (天禧 Tiānxī or Tiānxǐ 天喜)3 1178–1218 |

| did not exist | did not exist | Kuchlug (屈出律 Qūchūlǜ) | use birth name | 1211–1218 | |

| 1 "Dashi" might be the Chinese title "Taishi", meaning "vizier"; or, it could mean "Stone" in Turkish, as the Chinese transliteration suggests. 2 Recently discovered Western Liao coins have the era name "Xuxing", suggesting that the era name "Shaoxing" recorded in Chinese sources may be incorrect.[90] | |||||

See also

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

|---|

|

| History of Kazakhstan |

|---|

|

| History of Kyrgyzstan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Biran 2005, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d e Grousset 1991, p. 165.

- ^ Taagepera, Rein (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 497. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D. (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Lamb, Harold (1927). Genghis Khan: Emperor of All Men. International Collectors Library. p. 53.

- ^ Morgan & Stewart 2017, p. 57.

- ^ a b 中国历史大辞典:辽夏金元史 (in Chinese (China)). 1986. p. 131.

- ^ a b Sicker, Martin (2000). The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 57. ISBN 9780275968922.

- ^ Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780813513041.

- ^ Komaroff, Linda (2006). Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan. Brill. p. 77. ISBN 9789047418573.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Biran, Michal (30 June 2020). "The Qara Khitai" (PDF). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.59. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2025. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

The Qara Khitai or Western Liao 西遼 dynasty (1124–1218) is the only dynasty that did not rule any part of China proper but is still considered a Chinese dynasty by both Chinese and Muslim historiography.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 93, "Though firmly located in Central Asia, the Qara Khitai or Western Liao is considered by the Liao Shi to be a legitimate Chinese dynasty, whose basic annals follow that of the proper Liao".

- ^ Morgan & Stewart 2017, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Schouenborg, Laust (2016). International Institutions in World History: Divorcing International Relations Theory from the State and Stage Models. Taylor & Francis. p. 133. ISBN 9781315409887.

- ^ Kane 2009, p. 163.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Chen, Yuan Julian (2014). "Legitimation Discourse and the Theory of the Five Elements in Imperial China". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 44 (44): 325–364. doi:10.1353/sys.2014.0000. S2CID 147099574.

- ^ a b c Sinor, D. (1998), "Chapter 11 – The Kitan and the Kara Kitay" (PDF), in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E. (eds.), History of Civilisations of Central Asia, vol. 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2016

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 215–217.

- ^ Starr 2015, p. 43.

- ^ Twitchett 1994, pp. 149–151.

- ^ a b Twitchett 1994, p. 151.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 37-38.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 39.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 39-41.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Asimov 1999, p. 238.

- ^ Biran 2001, p. 61.

- ^ Nowell 1953, p. 442.

- ^ Biran 2001, p. 62.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 43.

- ^ Grousset 1970, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Biran 2005, p. 44.

- ^ a b Biran 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Twitchett 1994, p. 153.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Morgan & Stewart 2017, p. 56.

- ^ a b Biran, Michael (2001b). Chinggis Khan: Selected Readings. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781780742045.

- ^ Denis Twitchett, Herbert Franke, John K. Fairbank, in The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 153.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 95.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 51.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 53-54.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 54-55.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 55-56.

- ^ a b Biran 2005, p. 57-58.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 57.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 60-61.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 61.

- ^ a b Biran 2005, p. 62.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 62-63.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 64-65.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 65-66.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 68.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 68-69.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 70.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 70-71.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 72-73.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 73-74.

- ^ Biran, pp. 48–80 for the complex details

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 74-75.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 87.

- ^ 1669 Sanson Map of Asia. www.geographicus.com

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 93–131.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 127-128.

- ^ a b Biran 2005, p. 93.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Biran, Michal (2001). "Like a Might Wall: The armies of the Qara Khitai" (PDF). Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 25: 46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2015.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 102, 196–201.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 96–.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 27–.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 146.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Biran 2005, pp. 99–101.

- ^ James A. Millward; Peter C. Perdue (2004). S.F.Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Boarderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 43. ISBN 9781317451372.

- ^ a b c d e f Vladimir A. Belyaev; A.A. Mospanov; S.V. Sidorovich (March 2020). "Recently discovered Khitan script official seal of the Western Liao State (Russian Studies of Chinese Numismatics and Sigillography)". Numismatique Asiatique. 33. Academia.edu. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Belyaev, V.A.; Nastich, V.N.; Sidorovich, S.V. (2012). "The coinage of Qara Khitay: a new evidence (on the reign title of the Western Liao Emperor Yelü Yilie)". Proceedings of the 3rd Simone Assemani Symposium, September 23–24, 2011, Rome.

- ^ Belyaev (别利亚耶夫), V.A.; Sidorovich (西多罗维奇), S.V. (2022). "天喜元宝"辨—记新发现的西辽钱币" (PDF). 中国钱币: 36–38.

Sources

[edit]- Asimov, M. S. (1999). The Historical, Social and Economic setting. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Biran, Michal (2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521842266.

- Grousset, Rene (1991). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press.

- Kane, Daniel (2009). The Kitan Language and Script. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004168299.

- Morgan, David; Stewart, Sarah, eds. (2017). The Coming of the Mongols. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781786733832.

- Nowell, Charles E. (1953). "The Historical Prester John". Speculum. 28 (3 (Jul)).

- Pozzi, Alessandra; Janhunen, Juha Antero; Weiers, Michael, eds. (2006). Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku: Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05378-5.

- Starr, S. Frederick (2015). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45137-2.

- Twitchett, Denis (1994), "The Liao", The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 43–153, ISBN 0521243319

Qara Khitai

View on GrokipediaNomenclature and Sources

Names and Etymology

The term Qara Khitai (also rendered as Kara Khitai or Qarā Khitāy), prevalent in Turkic, Mongolian, and Persian sources, translates literally as "Black Khitai," with qara (or kara) denoting "black" in these languages and Khitai referring to the Khitan people who established the original Liao dynasty (907–1125 CE) in northern China.[3] This nomenclature emerged among Central Asian and Islamic chroniclers to identify the empire founded by Khitan exiles under Yelü Dashi in 1124 CE, distinguishing it from the defeated eastern Liao territories conquered by the Jurchen Jin dynasty.[3] The "black" qualifier likely signified a geographical or political differentiation, associating the western realm with directional color symbolism in steppe cultures (black for the north or west) or marking its opposition to the eastern Jin regime, rather than implying racial or cultural inferiority.[3] Chinese historiographical records designated the polity as Xī Liáo (Western Liao), reflecting its location relative to the original Liao heartland, while the rulers officially proclaimed it the Dà Liáo (Great Liao) to assert dynastic continuity and imperial legitimacy.[3] Muslim sources consistently employed Qarā Khitāy, reinforcing the Turkic-derived epithet in accounts of interactions with the Seljuks and Khwarazmians.[3] The root Khitai derives from the endonym of the Khitan tribal confederation, a Mongolic-speaking group whose precise etymology remains obscure and debated among linguists, potentially linked to proto-Mongolic terms for tribal identity or locality but without consensus on origins.[4] This name persisted in Eurasian nomenclature, influencing later designations like "Cathay" in medieval Europe for China via Arab intermediaries.[4]Primary Sources and Historiography

The historiography of the Qara Khitai draws from a limited corpus of primary sources, predominantly Chinese dynastic histories and Persian chronicles, owing to the scarcity of surviving indigenous Khitan documents such as court annals or inscriptions specific to the Western Liao period. The Liao shi (History of Liao), officially compiled in 1344 under Yuan auspices by Toqto'a and a team of scholars, remains the foundational Chinese text, integrating pre-existing Liao records to chronicle the empire's founding by Yelü Dashi in 1124, its expansions, and administrative continuity with the eastern Liao Dynasty up to the Mongol conquest in 1218. This source frames the Qara Khitai as a legitimate extension of Khitan rule, emphasizing bureaucratic and cultural retention of Liao practices amid nomadic adaptation.[5] Supplementary Chinese materials include the Jin shi (History of Jin), which records interactions from the Jurchen perspective, and to a lesser degree the Song shi (History of Song) and Yuan shi (History of Yuan), providing contemporaneous diplomatic and military details, such as tribute exchanges and border conflicts. These texts, while valuable for chronological precision—e.g., dating Yelü Dashi's victory at Qatwan to 1141—exhibit a Sinocentric bias, prioritizing legitimacy and imperial genealogy over internal dynamics or non-Chinese influences.[5] Persian sources offer complementary but often adversarial viewpoints, reflecting the empire's dominance over Muslim polities. ʿAṭā-Malik Juvāynī's Tārīkh-i Jahān-gushā (History of the World Conqueror), completed around 1260, details key events like the subjugation of the Qarakhanids and Seljuqs, portraying the Khitans as infidel conquerors who extracted tribute and enforced religious tolerance unevenly, though its pre-Mongol sections rely on secondhand reports from Central Asian informants. Rashīd al-Dīn's Jāmīʿ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles), composed in the early 1300s under Ilkhanid patronage, incorporates similar narratives alongside Mongol oral traditions, highlighting the Qara Khitai's role as a precursor to Chinggis Khan's expansions but amplifying perceptions of their religious otherness and administrative impositions on Islamic subjects. These Islamic texts, while rich in geographic and ethnographic details, introduce interpretive challenges due to unclear sourcing and a tendency to conflate Khitan rule with broader anti-Muslim sentiment.[5] Historiographical reconstruction faces obstacles from source fragmentation and bias: Chinese accounts understate nomadic elements and Muslim cultural impacts, while Persian ones exaggerate oppression to underscore religious legitimacy for later Muslim resistance, as seen in depictions of jizya collection post-Qatwan. Material evidence, including Khitan-script seals and coins from sites like Balasagun, corroborates textual claims of hybrid governance but adds little narrative depth. Contemporary scholarship, notably Michal Biran's synthesis of bilingual sources, mitigates these gaps by cross-verifying chronologies and institutions, revealing the Qara Khitai's Eurasian bridging function without over-relying on any single tradition's framing.[5][6]Origins and Establishment

Collapse of the Liao Dynasty

The Liao Dynasty, ruling over northern China and parts of Inner Asia since 907, entered a period of decline in the early 12th century due to internal mismanagement, economic pressures from excessive taxation and tribute demands on vassals, and factional strife within the Khitan elite. Emperor Tianzuo (r. 1101–1125) prioritized court luxuries and nomadic pursuits over military reforms, weakening defenses against emerging threats. Short-term climatic catastrophes, including intense cold spells and droughts spanning roughly a decade, triggered widespread famines, refugee migrations, and social violence, further eroding the dynasty's bureaucratic stability and agricultural base in Mongolia and northern China.[7][8] The decisive catalyst was the rebellion of the Jurchen tribes, semi-nomadic vassals in Manchuria who chafed under Liao's escalating exactions. In 1114, Wanyan Aguda unified disparate Jurchen clans and launched raids, capturing the fortress of Ningjiang Prefecture and refusing further tribute. Aguda proclaimed the Jin Dynasty in 1115, establishing a rival state that rapidly militarized with superior cavalry tactics and iron discipline, contrasting Liao's overstretched forces. Jin invasions progressed methodically, seizing Liao's northern strongholds and exploiting alliances; in 1120, the Southern Song Dynasty, seeking to reclaim lost territories like the Sixteen Prefectures, forged a pact with Jin to attack from the south, providing financial aid in exchange for territorial concessions.[8][8] By 1122, Jin had captured Liao's Southern Capital (Nanjing, modern Beijing), forcing Tianzuo into flight across the empire's vast domains. Aguda's death in 1123 did not halt the momentum; his successor, Wanyan Wuqimai, oversaw the fall of the Eastern Capital in 1124. Tianzuo's repeated evasions ended in March 1125 when Jin general Wanyan Zonghan ambushed and captured him near present-day Chaoyang in Liaoning Province, along with much of the imperial clan. This event precipitated the dynasty's collapse, as remaining Liao garrisons surrendered or fragmented; a puppet Northern Liao regime under Tianzuo's cousin Yelü Chun endured briefly until Jin subdued it in 1129. Loyalist remnants, numbering tens of thousands under princes like Yelü Dashi—a distant imperial relative appointed chancellor in 1123—evaded capture by migrating westward, preserving Khitan military traditions amid the ruin.[8][8]Migration and Founding under Yelü Dashi

In 1124, as Jurchen forces of the Jin dynasty overran Liao territories, Yelü Dashi, a scion of the imperial Yelü clan born around 1087–1094, fled northwest with loyal Khitan nobles, soldiers, and civilians, including Han Chinese administrators from Liao garrisons.[9] He established a temporary base at Kedun, a former Liao military outpost near the Orkhon River in the Mongolian plateau, where he rallied additional followers amid the chaos of the Liao collapse, forming a migratory force estimated at tens of thousands.[10] This exodus preserved Khitan elite continuity, incorporating nomadic tribes like Uyghurs and local Mongolic groups through alliances and recruitment, while avoiding direct confrontation with Jin until later failed attempts at reclamation.[11] Over the next several years, Yelü Dashi's group migrated further southwest into the steppes of modern Kazakhstan and Semirechye, navigating conflicts with Kara-Khanid rulers and consolidating authority by integrating Central Asian nomads and sedentary populations. By 1130–1131, having secured initial victories against local khans, he relocated to the vicinity of Yemil (near Lake Balkhash), where in February 1132 he proclaimed himself Gür-khān ("universal khan"), adopting the reign era Yānqìng ("extended celebration") and founding the Western Liao dynasty, later known as Qara Khitai among Muslim subjects for its "black" or western Khitan identity.[12][13] This act formalized the regime's dual Sinic-Khitan and steppe imperial structure, retaining Liao bureaucratic titles like dì (emperor) alongside Turkic-Mongolic ones, and marked the transition from refugee band to sovereign empire.[14] The founding solidified through military expansion, including the 1134 capture of Balasagun from the Kara-Khanids, establishing a capital and tax base in the fertile Ferghana Valley and Tian Shan regions, which supported a multi-ethnic administration blending Khitan military prowess with inherited Chinese fiscal systems.[15] Yelü Dashi ruled until his death in 1143, leaving a stable polity that endured until Mongol conquests, with primary accounts from Liao annals and Persian chroniclers confirming the migration's role in transmitting East Asian governance westward without romanticizing its hardships or scale.[16]Expansion and Military Achievements

Battle of Qatwan and Defeat of the Seljuks

In 1140, Yelü Dashi, ruler of the Qara Khitai, intervened in a civil conflict between the eastern and western branches of the Qarakhanid Khanate, vassals of the Seljuk Empire, by supporting the eastern Qarakhanids against their western rivals allied with the Karluks.[17] The western Qarakhanids appealed to Seljuk Sultan Ahmad Sanjar for aid, prompting him to mobilize an army and march toward Samarkand in 1141 to confront the encroaching Qara Khitai forces, which had already captured Balasagun in 1134 and expanded into Transoxiana.[18] This escalation stemmed from Qara Khitai ambitions to consolidate control over Central Asian trade routes and nomadic territories, clashing with Seljuk hegemony east of the Amu Darya. The two armies met on the Qatwan steppe north of Samarkand on September 9, 1141, where Qara Khitai forces, leveraging superior mobility and nomadic auxiliaries including Karluks and possibly Khwarazmian elements, launched a coordinated surprise attack that encircled the Seljuk center and flanks.[17] Contemporary chronicler Ibn al-Athir, drawing from eyewitness Muslim accounts, described Qara Khitai tactics involving feigned retreats to draw Seljuk pursuers into ambushes, followed by heavy cavalry charges that exploited the terrain, forcing Sanjar's main body into the narrow Dargham wadi approximately 12 kilometers from Samarkand; while Ibn al-Athir's troop estimates—300,000 for the Qara Khitai and 100,000 for the Seljuks—reflect hyperbolic medieval inflation typical of Arabic sources to emphasize the scale of disaster, the qualitative edge in steppe warfare tactics favored the Khitans.[19] Sanjar's army, reliant on Turkic tribal levies prone to desertion and less cohesive infantry, suffered heavy casualties from the envelopment, with Qara Khitai archers and lancers decimating disorganized counterattacks. The Seljuk rout was total, with Sanjar fleeing southward barely escaping capture, abandoning vast quantities of baggage, treasury, and banners; this catastrophe shattered Seljuk prestige and military capacity in the east, enabling Qara Khitai suzerainty over the Qarakhanids and Khwarazm, while triggering Oghuz revolts that further fragmented the empire by 1157.[20] The defeat exposed underlying Seljuk vulnerabilities, including overextension across diverse ethnic levies and fiscal strains from prolonged campaigns, marking a pivotal shift where Qara Khitai dominance redirected Central Asian power dynamics until the Mongol invasions.[19]Conquests and Territorial Peak

Following the decisive victory at the Battle of Qatwan in September 1141, the Qara Khitai consolidated their dominance over Transoxiana by subjugating local Muslim rulers and integrating the region into their empire, marking a significant expansion westward.[6] This conquest included the submission of the Khwarezmshah Atsïz, who acknowledged Qara Khitai suzerainty to avoid further conflict, thereby extending influence toward the Amu Darya River.[21] Prior eastern gains, such as the capture of Balasagun in 1134 and the defeat of the Western Kara-Khanid Khanate by 1137, were solidified, with puppet khans installed in Kashgar and other key centers like Khotan.[22] The empire reached its territorial zenith in the mid-12th century under Yelü Dashi (r. 1124–1143) and his successors, encompassing vast swathes of Central Asia from the Altai Mountains in the east to the Oxus River (Amu Darya) in the west.[23] This domain included the Semirechye region, the Chu Valley, the Tarim Basin oases, and Transoxiana, corresponding to modern-day eastern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and parts of Xinjiang in China.[6] Vassal relations with fragmented Karakhanid states and Khwarezm ensured tribute and military support, enhancing the Qara Khitai's control without direct occupation of every province.[21] By around 1160, the Qara Khitai maintained this extensive realm through a combination of Khitan military prowess and administrative continuity from Liao practices, ruling over a diverse population of Turkic, Iranian, and other groups.[1] However, internal stability waned after the regency of Xiao Tabuyan (c. 1143–1150), with later rulers facing revolts that began to erode peripheral territories by the late 12th century.[6]Conflicts with Neighboring Powers

In the early 1170s, the Qara Khitai encountered rebellions from northern and eastern tribes, including the Yebulian, amid broader instability during campaigns against Khwarazm; an imperial son-in-law named Abensi led an expedition to suppress them but failed to secure a decisive victory.[9] A major punitive campaign occurred in 1172 when the Qara Khitai crossed the Amu Darya to compel tribute from the Khwarazm Shah Il-Arslan, who had withheld payments; the Khwarazmian army suffered defeat, reinforcing Qara Khitai overlordship in Transoxiana temporarily.[24][25] Tensions with the Ghurids escalated in 1198 after Muhammad of Ghor captured Balkh from a Qara Khitai vassal; urged by Khwarazm Shah Tekish, the Qara Khitai dispatched approximately 20,000 horsemen, achieving victory in part due to a strong wind blowing dust into Ghurid faces, though exact battle details remain debated in historical accounts.[25] By 1210, under Ala al-Din Muhammad, Khwarazm forces decisively defeated Qara Khitai commander Tayangu near the Talas River, capturing Transoxiana and ending Qara Khitai suzerainty over the region; this reversal, combined with ongoing tribal unrest, critically weakened the empire's defenses against emerging threats like the Naimans and Mongols.[3]Governance and Administration

Central Structure and Bureaucracy

The Qara Khitai empire was governed by a supreme ruler titled Gur-khan, a Turkic term denoting universal authority, which Yelü Dashi adopted in 1132 following his victory over the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[1] This title underscored the ruler's position as an absolute monarch exercising personal control over the core territories, blending Inner Asian nomadic traditions with imperial pretensions inherited from the Liao dynasty. Unlike the more structured Liao administration, the Qara Khitai central government emphasized direct personal relations between the Gur-khan and elites rather than a rigid bureaucratic hierarchy.[23] Key administrative roles included ministers (daizhao in Chinese-derived titles) and viziers adapted from Islamic influences, with figures like Mahmud Tai serving as chief vizier to manage fiscal and diplomatic affairs.[26] The bureaucracy retained Liao-era Chinese administrative nomenclature for official seals, coinage, and edicts, but incorporated local Turkic terms such as tayanggu for regional overseers.[27] However, central institutions remained limited, lacking extensive civil service mechanisms or standardized examinations; appointments prioritized loyalty among Khitan elites and local collaborators over meritocratic selection.[1] Overall, the Qara Khitai bureaucracy was far less centralized than its Liao predecessor, relying on tribute extraction and oversight of vassal states rather than direct provincial governance.[1] This hybrid system facilitated rule over diverse Muslim and nomadic populations but contributed to vulnerabilities, as evidenced by the influence of powerful ministers during periods of weak rulership.[26]Provincial Control and Vassal Relations

The Qara Khitai exercised provincial control primarily through indirect rule, delegating authority to local vassal rulers and chieftains while maintaining oversight via appointed governors responsible for taxation, censuses, and enforcement.[3] This approach contrasted with more centralized systems, avoiding a formal appanage structure and instead relying on fiscal agents known as šeḥna or basqaq, who operated with small retinues to monitor tribute collection without large garrisons.[3] The central administration, centered near Balāsāḡun, focused on managing the nomadic Khitan core, while sedentary regions like Kāšḡar, Khotan, and Transoxania retained significant autonomy under local dynasties, preserving their economies and customs to ensure stability.[3] Vassal relations were formalized through symbols of submission, such as silver paizu (tablets) and seals granted by the Gurkhan, alongside requirements for annual tribute and the inclusion of the overlord's name in Friday sermons in Muslim territories.[3] The Kara-Khanid Khanate, particularly its western branch in Transoxania and Farghana, became a key vassal after Yelü Dashi provided aid against Qarluk and Qanqali tribes in the 1130s, relocating the ruler to Kāšḡar and conferring the title ilek-i türkmen; these rulers governed locally but faced potential dismissal by the Gurkhan.[3] Similarly, the Khwarazm Shahs paid an annual tribute of 30,000 gold dinars following the Qara Khitai victory over the Seljuks at Qatwan in 1141, acknowledging suzerainty over regions up to the Amu Darya.[3] Other vassals included the Gaochang Uighurs (Qocho kingdom), who submitted tribute and hosted governors until a rebellion in 1209 led to military reprisal after the killing of a šeḥna, and various Karluk and Mongolian tribes integrated through alliances or conquest.[3] Local rulers in cities like Samarqand received insignia to affirm loyalty, with the Qara Khitai enforcing compliance via a mobile cavalry force rather than permanent occupation, a strategy that sustained the empire's expanse from the Altai to the Oxus until internal upheavals in the early 13th century.[3]Economic Systems and Taxation

The economy of the Qara Khitai combined sedentary agriculture in irrigated oases of Turkestan with nomadic pastoralism across the steppe regions. Agricultural production focused on crops such as cotton, grapes, apples, onions, and watermelons, supported by established irrigation systems that ensured relative stability in settled areas. Nomadic elements emphasized animal husbandry, including horses, cattle, and camels, alongside hunting for subsistence and trade. This dual structure reflected the empire's inheritance of Liao dynasty practices adapted to Central Asian conditions, promoting economic continuity in villages, oases, and urban mercantile centers like Samarkand and Kashgar.[6] Taxation formed the core of fiscal revenue, levied primarily on a per-household basis through censuses conducted in central territories, with collection overseen by appointed governors known as šeḥna or basqaq. These officials managed direct assessments, ensuring systematic gathering rather than arbitrary exactions, though the system remained decentralized outside core areas. The empire issued minimal coinage, prioritizing in-kind and tribute-based revenues over a fully monetized economy. Vassal states provided significant supplementary income; Khwarazm, for example, paid an annual tribute of 30,000 gold dinars to the gurkhan, often in exchange for autonomy in local governance while acknowledging Qara Khitai suzerainty in official ceremonies like Friday sermons.[6] Trade along Silk Road routes bolstered revenues through transit duties and mercantile activity, with Uighur intermediaries facilitating exchanges with China via the Tangut empire. Policies under rulers like Yelü Dashi (r. 1124–1143) emphasized stability to sustain these flows, avoiding disruptive over-taxation that could undermine agricultural or commercial productivity. This approach contributed to economic resilience until internal strife and external pressures in the late 12th century, though specific tax rates or yields remain sparsely documented beyond tribute figures.[6]Society, Culture, and Religion

Ethnic Composition and Social Hierarchy

The Qara Khitai empire was governed by a Khitan elite of nomadic origin, constituting a small minority who settled primarily around their capital at Balasagun. These Khitans, descendants of the Liao dynasty rulers, preserved elements of their tribal structure while adopting administrative practices from Chinese traditions.[6] The ruling class maintained a nomadic lifestyle, emphasizing military prowess and loyalty to the gurkhan, the supreme title held by emperors like Yelü Dashi. The subject population was diverse and predominantly sedentary, featuring Turkic groups such as the Qarluks near Balasagun, Qarakhanid Turks in Kashgar and Khotan, and Uyghurs in the Tarim Basin, alongside Iranian communities in cities like Samarkand and Bukhara.[6] This majority adhered to Islam, with significant minorities practicing Buddhism or Nestorian Christianity, particularly among nomadic tribes like the Naimans and Kerayits.[6] Chinese officials and scribes, inherited from Liao bureaucratic systems, served in administrative roles, facilitating governance over the multicultural realm. Social hierarchy placed the Khitan nobility at the apex, exerting control through vassal rulers and appointed overseers such as shehna or basqaq, who managed taxation and local order among sedentary Muslims.[6] Local elites, including Qarakhanid sultans, retained autonomy under Khitan suzerainty, receiving imperial insignia like paizu tablets to symbolize subordination.[6] Commoners, encompassing urban artisans, farmers, and rural nomads, bore the tax burden via household assessments, with the nomadic Khitan warriors forming the military backbone that enforced hierarchical stability. This structure reflected a synthesis of Inner Asian nomadic dominance over Islamic and Chinese sedentary elements, without widespread assimilation of the ruling Khitans into subject cultures.Religious Policies and Tolerance

The Khitan elite of the Qara Khitai professed Buddhism alongside ancestral shamanistic beliefs, reflecting a syncretic religious identity inherited from the Liao dynasty.[6] This elite faith coexisted with the diverse practices of their subjects, who included a Muslim majority in conquered Transoxanian territories, Nestorian Christian communities among Uighurs, Naimans, and Kerayits—with a metropolitan see established in Kashgar by the 12th century—and pockets of Manicheism.[6] Religious policy emphasized tolerance characteristic of nomadic governance traditions, eschewing forced conversions or impositions on subject populations.[6] [1] Local Muslim administrations retained significant autonomy under indirect rule, enabling the continuation of Islamic legal and communal structures, though overlordship was affirmed through requirements like incorporating the Qara Khitai ruler's name into Friday khutba sermons.[6] Other faiths similarly enjoyed freedoms, fostering a multicultural stability that supported the empire's administration over heterogeneous sedentary and nomadic groups without religious strife as a primary governance challenge.[1] [23] This approach, marked by benign conquests and broad autonomy, preserved the Qara Khitai's distinct non-Islamic identity—rooted in ties to the Chinese cultural sphere—while avoiding the assimilation seen in other steppe polities.[23] The policy's efficacy is evidenced by the relative harmony in a realm spanning Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim adherents, contributing to the dynasty's endurance until external conquests in the early 13th century.[1]Cultural Synthesis and Influences

The Qara Khitai empire represented a distinctive cultural synthesis, blending Khitan nomadic heritage with entrenched Chinese administrative and imperial traditions while navigating influences from Central Asian Turkic and Persian Islamic societies. Ruling elites, descended from the Liao dynasty, preserved Sinicized elements such as bureaucratic titles, the emperor's designation, and Chinese-style coinage, which underscored their self-perception as a legitimate continuation of Chinese imperial lineage known as the Western Liao. This Sinicization was evident in governance practices imported from northern China, including the use of civil service examinations and Confucian-inspired hierarchy among the Khitan aristocracy, adapted to oversee a vast, multi-ethnic domain spanning modern Xinjiang, Kazakhstan, and parts of Uzbekistan from 1124 to 1218.[5] To consolidate power over predominantly Muslim subjects, the Qara Khitai rulers adopted the Central Asian title Gürkhān, meaning "universal ruler," alongside their Chinese imperial claims, facilitating legitimacy in steppe and Islamic contexts without abandoning Khitan shamanistic and Buddhist practices. Religious policy emphasized tolerance, allowing Buddhism, shamanism, and Islam to coexist; Khitan monarchs like Yelü Dashi refrained from converting to Islam, maintaining ancestral faiths while permitting local customs, which fostered relative harmony until later upheavals. This pragmatic eclecticism enabled cultural exchanges, as seen in the empire's role as a conduit between Chinese and Islamic worlds, with Khitan script persisting in official seals for administrative continuity.[5][28] In art and material culture, synthesis manifested through hybrid artifacts: Chinese-influenced coins circulated alongside rare issues bearing the Gürkhān's name in Arabic script, reflecting economic integration with Islamic trade networks. Architectural remnants, such as the 12th-century Ā'isha Bibi Mausoleum in Talas, display Chinese stylistic elements amid local forms, indicating adaptation of East Asian designs to Central Asian contexts. Jade artifacts from burial sites reveal East-West artistic fusion, with motifs blending Chinese carving techniques and steppe nomadic symbolism, underscoring the empire's diverse societal fabric where Khitan elites coexisted with Uighur, Karluk, and Persian populations. Limited archaeological evidence, including tomb murals depicting Khitan daily life like communal feasting, highlights retention of pastoral customs amid urban sedentarization.[29][5]Internal Challenges and Later Rulers

Reigns of Xiao Tabuyan, Yelü Yilie, and Yelü Pusuwan

Xiao Tabuyan, widow of founder Yelü Dashi, became regent upon his death in 1143, governing on behalf of their underage son Yelü Yilie until 1150. [30] Her administration focused on stabilizing the realm after Dashi's conquests, including oversight of tribute from vassal states like the Karluks and maintenance of alliances with the Western Xia, though primary Chinese annals such as the History of Liao record few specific initiatives or crises during this seven-year period.[30] This scarcity of detail in Sinocentric sources may reflect the remote location of the Qara Khitai court at Balasagun, limiting direct observation by Liao-era chroniclers. Yelü Yilie ascended the throne in 1150 at approximately age 12 and ruled until his death in 1163, marking a 13-year tenure of nominal Khitan imperial continuity. The History of Liao attributes only one concrete action to him: contracting a marriage alliance, interpreted by historians as an effort to bolster elite cohesion amid potential succession uncertainties.[30] No major internal rebellions or fiscal reforms are documented, suggesting effective delegation to bureaucratic holdovers from Dashi's era and a policy of non-intervention in peripheral vassal affairs, which preserved resources but may have fostered complacency in core administration. External pressures remained contained, with tribute flows from the Khwarazm Shahs and Seljuk remnants ensuring economic steadiness without demanding active campaigning. Before his death, Yelü Yilie designated his sister Yelü Pusuwan as successor, bypassing direct male heirs and initiating her regency for their nephew Yelü Zhilugu from 1164 to 1177. Pusuwan, titled Empress Chengtian, relied heavily on her husband Xiao Duolubu for military enforcement, dispatching him on campaigns to quell unrest among Uyghur and Karluk subjects and reaffirm suzerainty over Transoxiana, actions that temporarily reinforced fiscal inflows via renewed tribute.[30] However, this dependence highlighted nascent internal vulnerabilities, as familial command structures risked factionalism; later Persian sources like Juvayni's History of the World Conqueror imply strains from court intrigues, though these accounts, compiled post-Mongol conquest, warrant caution for potential exaggeration to underscore dynastic decadence. Her rule ended with her death in 1177, yielding power to Zhilugu amid unrecorded but probable elite maneuvering, signaling the onset of intensified succession disputes.[30]Yelü Zhilugu's Rule: Wars and Rebellions

Yelü Zhilugu ascended the throne in 1178 following the regency of Xiao Wolila, amid ongoing tensions with vassal states and emerging powers. Early in his reign, the Qara Khitai maintained alliances that led to joint military actions, including a campaign in 1198 allied with the Khwarazm Shah Tekish against the Ghurid dynasty. Qara Khitai forces under Zhilugu captured the region of Guzgan, while Tekish targeted Herat, temporarily weakening Ghurid control in parts of modern Afghanistan.[9] By the early 1200s, internal dissent escalated in the eastern territories. In 1204, Zhilugu quelled a rebellion in Khotan and Kashgar, regions with growing Muslim populations resistant to Khitan overlordship, restoring nominal control through military suppression. Around the same period, he intervened in Qayalïq, a Karluk vassal state in the Semirechye, deposing its hostile khan to secure loyalty amid tribal unrest. External pressures mounted as Khwarazm asserted independence. In 1210, Zhilugu's army, commanded by Tayangu, suffered defeat against Sultan ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Muḥammad near the Talas River, resulting in the loss of Transoxiana and marking a significant erosion of Qara Khitai authority in the west.[3] These conflicts highlighted the empire's overextension, with rebellions and wars straining resources against both internal separatists and ambitious neighbors.Usurpation by Kuchlug and Religious Persecution