Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Philistines

View on Wikipedia

Philistines (Hebrew: פְּלִשְׁתִּים, romanized: Pəlištīm; LXX Koine Greek: Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: Phulistieím; Latin: Philistaei) were ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan during the Iron Age in a confederation of city-states generally referred to as Philistia.

There is evidence to suggest that the Philistines originated from a Greek immigrant group from the Aegean.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] The immigrant group settled in Canaan around 1175 BC, during the Late Bronze Age collapse. Over time, they intermixed with the indigenous Canaanite societies and assimilated elements from them, while preserving their own unique culture.[8]

In 604 BC, the Philistines, who had been under the rule of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC), were ultimately vanquished by King Nebuchadnezzar II of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[9] Much like the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, the Philistines lost their autonomy by the end of the Iron Age, becoming vassals to the Assyrians, Egyptians, and later Babylonians. Historical sources suggest that Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed Ashkelon and Ekron due to the Philistines' rebellion, leading to the exile of many Philistines, who gradually lost their distinct identity in Babylonia. By the late fifth century BC, the Philistines no longer appear as a distinct group in historical or archaeological records,[10][11] though the extent of their assimilation remains subject to debate.

The Philistines are known for their biblical conflict with the peoples of the region, in particular, the Israelites. Though the primary source of information about the Philistines is the Hebrew Bible, they are first attested to in reliefs at the Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, in which they are called the Peleset (𓊪𓏲𓂋𓏤𓏤𓐠𓍘𓇋𓍑), accepted as cognate with Hebrew Peleshet;[12] the parallel Assyrian term is Palastu, Pilišti, or Pilistu (Akkadian: 𒉺𒆷𒀸𒌓, 𒉿𒇷𒅖𒋾, and 𒉿𒇷𒅖𒌓).[13] They also left behind a distinctive material culture.[8]

Name

[edit]The English term Philistine comes from Old French Philistin; from Classical Latin Philistinus; from Late Greek Philistinoi; from Koine Greek Φυλιστιείμ (Philistiim),[14] ultimately from Hebrew Pəlištī (פְּלִשְׁתִּי; plural Pəlištīm, פְּלִשְׁתִּים), meaning 'people of Pəlešeṯ' (פְּלֶשֶׁת). The name also had cognates in Akkadian Palastu and Egyptian Palusata.[15] The native Philistine endonym is unknown.

History

[edit]

During the Late Bronze Age collapse, an apparent confederation of seafarers known as the Sea Peoples are recorded as attacking ancient Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean civilizations.[16] While their exact origins are a mystery, and probably diverse, it is generally agreed that the Sea Peoples had origins in the greater Southern European and West Asian area, including western Asia Minor, the Aegean, and the islands of the East Mediterranean.[16][17] Egypt, in particular, repelled numerous attempted invasions from the Sea Peoples, most famously at the Battle of the Delta (c. 1175 BC),[18] where pharaoh Ramesses III defeated a massive invasion force which had already plundered Hattusa, Carchemish, Cyprus, and the Southern Levant. Egyptian sources name one of these implicated Sea Peoples as the pwrꜣsꜣtj, generally transliterated as either Peleset or Pulasti. Following the Sea Peoples' defeat, Ramesses III allegedly relocated a number of the pwrꜣsꜣtj to southern Canaan, as recorded in an inscription from his funerary temple in Medinet Habu,[19] and the Great Harris Papyrus.[20][21] Though archaeological investigation has been unable to correlate any such settlement existing during this time period,[22][23][24] this, coupled with the name Peleset/Pulasti and the peoples' supposed Aegean origins, has led many scholars to identify the pwrꜣsꜣtj with the Philistines.[25]

Typically "Philistine" artifacts begin appearing in Canaan by the 12th century BC. Pottery of Philistine origin has been found far outside of what would later become the core of Philistia, including at the majority of Iron Age I sites in the Jezreel Valley; however, because the quantity of said pottery finds are light, it is assumed that the Philistines' presence in these areas were not as strong as in their core territory, and that they probably were a minority which had assimilated into the native Canaanite population by the 10th century BC.[26]

There is little evidence that the Sea Peoples forcefully injected themselves into the southern Levant; and the cities which would become the core of Philistine territory, such as Ashdod,[27] Ashkelon,[28] Gath,[29] and Ekron,[30] show nearly no signs of an intervening event marked by destruction. The same can be said for Aphek where an Egyptian garrison was destroyed, likely in an act of warfare at the end of the 13th century, which was followed by a local Canaanite phase, which was then followed by the peaceful introduction of Philistine pottery.[31] The lack of destruction by the Sea Peoples in the southern Levant should not be surprising as Canaan was never mentioned in any text describing the Sea Peoples as a target of destruction or attack by the Sea Peoples.[32] Other sites such as Tell Keisan, Acco, Tell Abu Hawam, Tel Dor, Tel Mevorak, Tel Zeror, Tel Michal, Tel Gerisa, and Tel Batash, have no evidence of a destruction ca. 1200 BC.[33]

By Iron Age II, the Philistines had formed an ethnic state centered around a pentapolis consisting of Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron and Gath. Whether or not historians are inclined to accept the historicity of the old canonical books of the Hebrew nation, their writers describe a series of conflicts between the Philistines and the Israelites during the period of the Judges, and, allegedly, the Philistines exercised lordship over Israel in the days of Saul and Samuel the prophet, forbidding the Israelites from making iron implements of war.[34] According to their chronicles, the Philistines were eventually subjugated by David,[35] before regaining independence in the wake of the United Monarchy's dissolution, after which there are only sparse references to them. The accuracy of these narratives is a subject of debate among scholars.[36]

The Philistines seemed to have generally retained their autonomy, up until the mid-8th century BC, when Tiglath-Pileser III, the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, marched into the region, conquering much of the Levant that was not already under Assyrian rule (including Aram-Damascus and Phoenicia), and occupying the remaining kingdoms in the area (including Philistia). Decades later, Egypt began agitating its neighbours to rebel against Assyrian rule. A revolt in Israel was crushed by Sargon II in 722 BC, resulting in the kingdom's total destruction. In 712 BC, a Philistine named Iamani ascended to the throne of Ashdod, and organized another failed uprising against Assyria with Egyptian aid. The Assyrian King Sargon II invaded Philistia, which effectively became annexed by Assyria, although the kings of the five cities, including Iamani, were allowed to remain on their thrones as vassals.[37] In his annals concerning the campaign, Sargon II singled out his capture of Gath, in 711 BC.[38] Ten years later, Egypt once again incited its neighbors to rebel against Assyria, resulting in Ashkelon, Ekron, Judah, and Sidon revolting against Sargon's son and successor, Sennacherib. Sennacherib crushed the revolt, defeated the Egyptians, and destroyed much of the cities in southern Aramea, Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah, and entered the northern Sinai, though he was unable to capture the Judahite capital, Jerusalem, instead forcing it to pay tribute. As punishment, the rebel nations paid tribute to Assyria, and Sennacherib's annals report that he exacted such tribute from the kings of Ashdod, Ashkelon, Gaza, and Ekron, but Gath is never mentioned, which may indicate that the city was actually destroyed by Sargon II.

The Philistines were later occupied by the Egyptians in 609 BC, under Necho II.[39] In 604/603 BC, following a Philistine revolt, Nebuchadnezzar II, the king of Babylon, took over and destroyed Askhelon, Gaza, Aphek, and Ekron, which is proven by archaeological evidence and contemporary sources.[11][40] Some Philistine kings requested help from the Egyptians but they were ultimately ignored.[40] Following the destruction of the Philistine cities, their inhabitants were either killed or exiled to Mesopotamia.[11][10] Those exiled continued identifying themselves as the "men of Gaza" or Ashkelon for roughly 150 years, until they finally lost their distinct ethnic identity.[11]

Babylonian ration lists dating back to the early 6th century BC, which mention the offspring of Aga, the ultimate ruler of Ashkelon, provide clues to the eventual fate of the Philistines. This evidence is further illuminated by documents from the latter half of the 5th century BC found in the Murasu Archive at Nippur. These records, which link individuals to cities like Gaza and Ashkelon, highlight a continued sense of ethnic identity among the Philistines who were exiled in Babylonia. These instances represent the last known mentions of the Philistines, marking the end of their presence in historical accounts.[10]

During the Persian period, the region of Philistia saw resettlement, with its inhabitants being identified as Phoenicians, although evidence for continuity from earlier, Iron Age traditions in the region is scarce.[11] The citizens of Ashdod were reported to keep their language but it might have been an Aramaic dialect.[41]

Biblical accounts

[edit]Origins

[edit]In the Book of Genesis, 10:13–14 states, with regard to descendants of Mizraim, in the Table of Nations: "Mizraim begot the Ludim, the Anamim, the Lehabim, the Naphtuhim, the Pathrusim, the Casluhim, and the Caphtorim, whence the Philistines came forth."[42] There is debate among interpreters as to whether Genesis 10:13–14 was intended to signify that the Philistines were the offspring of the Caphtorim or Casluhim.[43] Some interpreters, such as Friedrich Schwally,[44] Bernhard Stade,[45] and Cornelis Tiele[46] have argued for a third, Semitic origin.

According to rabbinic sources, the name Philistines designated two separate groups; those said to descend from the Casluhim were different from those described in the Deuteronomistic history.[47][48] Deuteronomist sources describe the "Five Lords of the Philistines"[a] as based in five city-states of the southwestern Levant: Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath, from Wadi Gaza in the south to the Yarqon River in the north. This description portrays them at one period of time as among the Kingdom of Israel's most dangerous enemies.[49] In the Septuagint, the term allophiloi (Greek: ἀλλόφυλοι), which means simply "other nations", is used instead of "Philistines".

Theologian Matthew Poole suggests that Casluhim and Caphtorim were brother tribes who lived in the same territory. However, the Capthorim enslaved the Cashluhim and their Philistine descendants, forcing the latter to flee to Canaan, according to Amos 9:7.[50]

Torah (Pentateuch)

[edit]The Torah does not record the Philistines as one of the nations to be displaced from Canaan. In Genesis 15:18–21,[51] the Philistines are absent from the ten nations Abraham's descendants will displace as well as being absent from the list of nations Moses tells the people they will conquer, though the land in which they resided is included in the boundaries based on the locations of rivers described.[52] In fact, the Philistines, through their Capthorite ancestors, were allowed to conquer the land from the Avvites.[53] However, their de-facto control over Canaan appears to have been limited. Joshua 13:3 states that only five cities, Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Gath and Ekron, were controlled by Philistine lords. Three of these cities were later overtaken by the Anakim, making them a target for Israelite conquests as seen in Judges 3:3 and 2 Samuel 21:20.

God also directed the Israelites away from the Philistines upon their Exodus from Egypt, according to Exodus 13:17.[54] In Genesis 21:22–27,[55] Abraham agrees to a covenant of kindness with Abimelech, the Philistine king, and his descendants. Abraham's son Isaac deals with the Philistine king similarly, by concluding a treaty with them in chapter 26.[56]

Unlike most other ethnic groups in the Bible, the Philistines are almost always referred to without the definite article in the Torah.[57]

Deuteronomistic history

[edit]

Rabbinic sources state that the Philistines of Genesis were different people from the Philistines of the Deuteronomistic history (the series of books from Joshua to 2 Kings).[48]

According to the Talmud, Chullin 60b, the Philistines of Genesis intermingled with the Avvites. This differentiation was also held by the authors of the Septuagint (LXX), who translated (rather than transliterated) its base text as "foreigners" (Koine Greek: ἀλλόφυλοι, romanized: allóphylloi, lit. 'other nations') instead of "Philistines" throughout the Books of Judges and Samuel.[48][58] Based on the LXX's regular translation as "foreigners", Robert Drews states that the term "Philistines" means simply "non-Israelites of the Promised Land" when used in the context of Samson, Saul and David.[59]

Judges 13:1 tells that the Philistines dominated the Israelites in the times of Samson, who fought and killed over a thousand. According to 1 Samuel 5, they even captured the Ark of the Covenant and held it for several months; in 1 Samuel 6, the return of the Ark to the Israelites of Beth Shemesh is described.

A number of biblical texts, like the stories reflecting Philistine expansion and the importance of Gath, seem to portray Late Iron Age I and Early Iron Age II memories.[36][60] They are mentioned more than 250 times, the majority in the Deuteronomistic history,[61] and are depicted as among the arch-enemies of the Israelites,[62] a serious and recurring threat before being subdued by David. Not all relations were negative, with the Cherethites and Pelethites, who were of Philistine origin,[63][64] serving as David's bodyguards and soldiers.[63]

The Aramean, Assyrian and Babylonian threat eventually took over, with the Philistines themselves falling victim to these groups. They were conquered by the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the Achaemenid Empire, and disappeared as a distinct ethnic group by the late 5th century BC.[10]

The Prophets

[edit]Amos in 1:8 sets the Philistines / ἀλλοφύλοι at Ashdod and Ekron.[65] In 9:7 God is quoted asserting that, as he brought Israel from Egypt, he also brought the Philistines from Caphtor.[66][67] In the Greek this is, instead, bringing the ἀλλόφυλοι from Cappadocia.[68]

The Bible books of Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Amos and Zephaniah speak of the destruction of the Philistines.[69][70][71][72] Jeremiah 47:4 describes the Philistines as the remnant of the Caphtorim because the latter were mysteriously destroyed, either by divine or man-made means.[50]

Battles between the Israelites and the Philistines

[edit]

The following is a list of battles described in the Bible as having occurred between the Israelites and the Philistines:[73]

- The Battle of Shephelah[74]

- Israelites defeated at the Battle of Aphek, Philistines capture the Ark[75]

- Philistines defeated at the Battle of Eben-Ezer[76]

- Some Philistine military success must have taken place subsequently, allowing the Philistines to subject the Israelites to a localised disarmament regime. 1 Samuel 13:19-21 states that no Israelite blacksmiths were permitted and they had to go to the Philistines to sharpen their weapons and agricultural implements.[77]

- Battle of Michmash, Philistines routed by Jonathan and his men[78]

- Near the Valley of Elah, David defeats Goliath in single combat[79]

- The Philistines defeat Israelites on Mount Gilboa, killing King Saul and his three sons Jonathan, Abinadab and Malkishua[80]

- Hezekiah defeats the Philistines as far as Gaza and its territory.[81]

Origin

[edit]

Several theories are given about the origins of the Philistines. The Hebrew Bible mentions in two places that they originate from a geographical region known as Caphtor (possibly Crete/Minoa),[82] although the Hebrew chronicles also state that the Philistines were descended from Casluhim, one of the 7 sons of Ham's second son, Miṣrayim.[83] The Septuagint connects the Philistines to other biblical groups such as Caphtorim and the Cherethites and Pelethites, which have been identified with the island of Crete.[84] These traditions, among other things, have led to the modern theory of Philistines having an Aegean origin.[63]

Scholarly consensus

[edit]Most scholars agree that the Philistines were of Greek origin,[85][86] and that they came from Crete and the rest of the Aegean Islands or, more generally, from the area of modern-day Greece.[87] This view is based largely upon the fact that archaeologists, when digging up strata dated to the Philistine time-period in the coastal plains and in adjacent areas, have found similarities in material culture (figurines, pottery, fire-stands, etc.) between Aegean-Greek culture and that of Philistine culture, suggesting common origins.[88][89][90] A minority, dissenting, claims that the similarities in material culture are only the result of acculturation, during their entire 575 years of existence among Canaanite (Phoenician), Israelite, and perhaps other seafaring peoples.[91]

The "Peleset" from Egyptian inscriptions

[edit]

Since 1846, scholars have connected the biblical Philistines with the Egyptian "Peleset" inscriptions.[92][93][94][95][96] All five of these appear from c.1150 BC to c.900 BC just as archaeological references to Kinaḫḫu, or Ka-na-na (Canaan), come to an end;[97] and since 1873 comparisons were drawn between them and to the Aegean "Pelasgians."[98][99] Archaeological research to date has been unable to corroborate a mass settlement of Philistines during the Ramesses III era.[22][23][24]

"Walistina/Falistina" and "Palistin" in Syria

[edit]Pro

[edit]A Walistina is mentioned in Luwian texts already variantly spelled Palistina.[100][101][102] This implies dialectical variation, a phoneme ("f"?) inadequately described in the script,[103] or both. Falistina was a kingdom somewhere on the Amuq plain, where the Amurru kingdom had held sway before it.[104]

In 2003, a statue of a king named Taita bearing inscriptions in Luwian was discovered during excavations conducted by German archaeologist Kay Kohlmeyer in the Citadel of Aleppo.[105] The new readings of Anatolian hieroglyphs proposed by the Hittitologists Elisabeth Rieken and Ilya Yakubovich were conducive to the conclusion that the country ruled by Taita was called Palistin.[101] This country extended in the 11th-10th centuries BC from the Amouq Valley in the west to Aleppo in the east down to Mehardeh and Shaizar in the south.[106]

Due to the similarity between Palistin and Philistines, Hittitologist John David Hawkins (who translated the Aleppo inscriptions) hypothesizes a connection between the Syro-Hittite Palistin and the Philistines, as do archaeologists Benjamin Sass and Kay Kohlmeyer.[107] Gershon Galil suggests that King David halted the Arameans' expansion into the Land of Israel on account of his alliance with the southern Philistine kings, as well as with Toi, king of Ḥamath, who is identified with Tai(ta) II, king of Palistin (the northern Sea Peoples).[108]

Contra

[edit]However, the relation between Palistin and the Philistines is much debated. Israeli professor Itamar Singer notes that there is nothing (besides the name) in the recently discovered archaeology that indicates an Aegean origin to Palistin; most of the discoveries at the Palistin capital Tell Tayinat indicate a Neo-Hittite state, including the names of the kings of Palistin. Singer proposes (based on archaeological finds) that a branch of the Philistines settled in Tell Tayinat and were replaced or assimilated by a new Luwian population who took the Palistin name.[109]

phyle histia theory

[edit]Allen Jones (1972 & 1975) suggests that the name Philistine represents a corruption of the Greek phyle-histia ('tribe of the hearth'), with the Ionic spelling of hestia.[110][111] Stephanos Vogazianos (1993) states that Jones "only answers problems by analogy and he mainly speculates" but notes that the root phyle may not at all be out of place.[3]: 31 Regarding this theory, Israel Finkelstein & Nadav Na'aman (1994) note the hearth constructions which have been discovered at Tell Qasile and Ekron.[112]

Genetic evidence

[edit]A study carried out on skeletons at Ashkelon in 2019 by an interdisciplinary team of scholars from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the Leon Levy Expedition found that human remains at Ashkelon, associated with Philistines during the Iron Age, derived most of their ancestry from the local Levantine gene pool, but with a certain amount of Southern-European-related admixture. This confirms previous historic and archaeological records of a Southern-European migration event.[1][113] The DNA suggests an influx of people with European heritage into Ashkelon in the 12th century BC. The individuals' DNA shows similarities to that of ancient Cretans, but it is impossible to specify the exact place in Europe from where Philistines had migrated to Levant, due to limited number of ancient genomes available for study, "with 20 to 60 per cent similarity to DNA from ancient skeletons from Crete and Iberia and that from modern people living in Sardinia."[113][114]

After two centuries since their arrival, the Southern-European genetic markers were dwarfed by the local Levantine gene pool, suggesting intensive intermarriage, but the Philistine culture and peoplehood remained distinct from other local communities for six centuries.[115]

The finding fits with an understanding of the Philistines as an "entangled" or "transcultural" group consisting of peoples of various origins, said Aren Maeir, an archaeologist at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. "While I fully agree that there was a significant component of non-Levantine origins among the Philistines in the early Iron Age," he said, "these foreign components were not of one origin, and, no less important, they mixed with local Levantine populations from the early Iron Age onward." Laura Mazow, an archaeologist at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C., said the research paper supported the idea that there was some migration from the west.[113] She added that the findings "support the picture that we see in the archaeological record of a complex, multicultural process that has been resistant to reconstruction by any single historical model."[9]

Modern archaeologists agree that the Philistines were different from their neighbors: their arrival on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean in the early 12th century B.C. is marked by pottery with close parallels to the ancient Greek world, the use of an Aegean—instead of a Semitic—script, and the consumption of pork.[116]

Archaeological evidence

[edit]Territory

[edit]

According to Joshua 13:3[117] and 1 Samuel 6:17,[118] the land of the Philistines, called Philistia, was a pentapolis in the southwestern Levant comprising the five city-states of Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath, from Wadi Gaza in the south to the Yarqon River in the north, but with no fixed border to the east.[49]

Tell Qasile (a "port city") and Aphek were located on the northern frontier of Philistine territory, and Tell Qasile in particular may have been inhabited by both Philistine and non-Philistine people.[119]

The location of Gath is currently identified with the site of Tell es-Safi, not far from Ekron, based on archaeological and geographical evidence.[120]

The identity of the city of Ziklag, which according to the Bible marked the border between the Philistine and Israelite territory, remains uncertain.[121]

In the western part of the Jezreel Valley, 23 of the 26 Iron Age I sites (12th to 10th centuries BC) yielded typical Philistine pottery. These sites include Tel Megiddo, Tel Yokneam, Tel Qiri, Afula, Tel Qashish, Be'er Tiveon, Hurvat Hazin, Tel Risim, Tel Re'ala, Hurvat Tzror, Tel Sham, Midrakh Oz and Tel Zariq. Scholars have attributed the presence of Philistine pottery in northern Israel to their role as mercenaries for the Egyptians during the Egyptian military administration of the land in the 12th century BC. This presence may also indicate further expansion of the Philistines to the valley during the 11th century BC, or their trade with the Israelites. There are biblical references to Philistines in the valley during the times of the Judges. The quantity of Philistine pottery within these sites is still quite small, showing that even if the Philistines did settle the valley, they were a minority that blended within the Canaanite population during the 12th century BC. The Philistines seem to have been present in the southern valley during the 11th century, which may relate to the biblical account of their victory at the Battle of Gilboa.[26]

Egyptian inscriptions

[edit]Since Edward Hincks[92] and William Osburn Jr.[93] in 1846, biblical scholars have connected the biblical Philistines with the Egyptian "Peleset" inscriptions;[94][95] and since 1873, both have been connected with the Aegean "Pelasgians".[98] The evidence for these connections is etymological and has been disputed.[99]

Based on the Peleset inscriptions, it has been suggested that the Casluhite[citation needed] Philistines formed part of the conjectured "Sea Peoples" who repeatedly attacked Egypt during the later Nineteenth Dynasty.[122][123] Though they were eventually repulsed by Ramesses III, he finally resettled them, according to the theory, to rebuild the coastal towns in Canaan. Papyrus Harris I details the achievements of the reign (1186–1155 BC) of Ramesses III. In the brief description of the outcome of the battles in Year 8 is the description of the fate of some of the conjectured Sea Peoples. Ramesses claims that, having brought the prisoners to Egypt, he "settled them in strongholds, bound in my name. Numerous were their classes, hundreds of thousands strong. I taxed them all, in clothing and grain from the storehouses and granaries each year." Some scholars suggest it is likely that these "strongholds" were fortified towns in southern Canaan, which would eventually become the five cities (the pentapolis) of the Philistines.[124] Israel Finkelstein has suggested that there may be a period of 25–50 years after the sacking of these cities and their reoccupation by the Philistines. It is possible that at first, the Philistines were housed in Egypt; only subsequently late in the troubled end of the reign of Ramesses III would they have been allowed to settle Philistia.[citation needed]

The "Peleset" appear in four different texts from the time of the New Kingdom.[125] Two of these, the inscriptions at Medinet Habu and the Rhetorical Stela at Deir al-Medinah, are dated to the time of the reign of Ramesses III (1186–1155 BC).[125] Another was composed in the period immediately following the death of Ramesses III (Papyrus Harris I).[125] The fourth, the Onomasticon of Amenope, is dated to some time between the end of the 12th or early 11th century BC.[125]

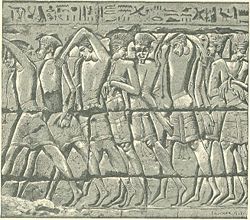

The inscriptions at Medinet Habu consist of images depicting a coalition of Sea Peoples, among them the Peleset, who are said in the accompanying text to have been defeated by Ramesses III during his Year 8 campaign. In about 1175 BC, Egypt was threatened with a massive land and sea invasion by the "Sea Peoples," a coalition of foreign enemies which included the Tjeker, the Shekelesh, the Deyen, the Weshesh, the Teresh, the Sherden, and the PRST. They were comprehensively defeated by Ramesses III, who fought them in "Djahy" (the eastern Mediterranean coast) and at "the mouths of the rivers" (the Nile Delta), recording his victories in a series of inscriptions in his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu. Scholars have been unable to conclusively determine which images match what peoples described in the reliefs depicting two major battle scenes. A separate relief on one of the bases of the Osiris pillars with an accompanying hieroglyphic text clearly identifying the person depicted as a captive Peleset chief is of a bearded man without headdress.[125] This has led to the interpretation that Ramesses III defeated the Sea Peoples, including Philistines, and settled their captives in fortresses in southern Canaan; another related theory suggests that Philistines invaded and settled the coastal plain for themselves.[126] The soldiers were quite tall and clean-shaven. They wore breastplates and short kilts, and their superior weapons included chariots drawn by two horses. They carried small shields and fought with straight swords and spears.[127]

The Rhetorical Stela are less discussed, but are noteworthy in that they mention the Peleset together with a people called the Teresh, who sailed "in the midst of the sea". The Teresh are thought to have originated from the Anatolian coast and their association with the Peleset in this inscription is seen as providing some information on the possible origin and identity of the Philistines.[128]

The Harris Papyrus, which was found in a tomb at Medinet Habu, also recalls Ramesses III's battles with the Sea Peoples, declaring that the Peleset were "reduced to ashes." The Papyrus Harris I, records how the defeated foe were brought in captivity to Egypt and settled in fortresses.[129] The Harris papyrus can be interpreted in two ways: either the captives were settled in Egypt and the rest of the Philistines/Sea Peoples carved out a territory for themselves in Canaan, or else it was Ramesses himself who settled the Sea Peoples (mainly Philistines) in Canaan as mercenaries.[130] Egyptian strongholds in Canaan are also mentioned, including a temple dedicated to Amun, which some scholars place in Gaza; however, the lack of detail indicating the precise location of these strongholds means that it is unknown what impact these had, if any, on Philistine settlement along the coast.[128]

The only mention in an Egyptian source of the Peleset in conjunction with any of the five cities that are said in the Bible to have made up the Philistine pentapolis comes in the Onomasticon of Amenope. The sequence in question has been translated as: "Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gaza, Assyria, Shubaru [...] Sherden, Tjekker, Peleset, Khurma [...]" Scholars have advanced the possibility that the other Sea Peoples mentioned were connected to these cities in some way as well.[128]

Material culture: Aegean origin and historical evolution

[edit]Aegean connection

[edit]

Many scholars have interpreted the ceramic and technological evidence attested to by archaeology as being associated with the Philistine advent in the area as strongly suggestive that they formed part of a large scale immigration to southern Canaan,[1][2][131] probably from Anatolia and Cyprus, in the 12th century BC.[132]

The proposed connection between Mycenaean culture and Philistine culture was further documented by finds at the excavation of Ashdod, Ekron, Ashkelon, and more recently Gath, four of the five Philistine cities in Canaan. The fifth city is Gaza. Especially notable is the early Philistine pottery, a locally made version of the Aegean Mycenaean Late Helladic IIIC pottery, which is decorated in shades of brown and black. This later developed into the distinctive Philistine pottery of the Iron Age I, with black and red decorations on white slip known as Philistine Bichrome ware.[133] Also of particular interest is a large, well-constructed building covering 240 square metres (2,600 sq ft), discovered at Ekron. Its walls are broad, designed to support a second story, and its wide, elaborate entrance leads to a large hall, partly covered with a roof supported on a row of columns. In the floor of the hall is a circular hearth paved with pebbles, as is typical in Mycenaean megaron hall buildings; other unusual architectural features are paved benches and podiums. Among the finds are three small bronze wheels with eight spokes. Such wheels are known to have been used for portable cultic stands in the Aegean region during this period, and it is therefore assumed that this building served cultic functions. Further evidence concerns an inscription in Ekron to PYGN or PYTN, which some have suggested refers to "Potnia", the title given to an ancient Mycenaean goddess. Excavations in Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath reveal dog and pig bones which show signs of having been butchered, implying that these animals were part of the residents' diet.[134][135] Among other findings there are wineries where fermented wine was produced, as well as loom weights resembling those of Mycenaean sites in Greece.[136] Further evidence of the Aegean origin of the initial Philistine settlers was provided by studying their burial practices in the so far only discovered Philistine cemetery, excavated at Ashkelon (see below).

However, for many years scholars such as Gloria London, John Brug, Shlomo Bunimovitz, Helga Weippert, and Edward Noort, among others, have noted the "difficulty of associating pots with people", proposing alternative suggestions such as potters following their markets or technology transfer, and emphasize the continuities with the local world in the material remains of the coastal area identified with "Philistines", rather than the differences emerging from the presence of Cypriote and/or Aegean/ Mycenaean influences. The view is summed up in the idea that 'kings come and go, but cooking pots remain', suggesting that the foreign Aegean elements in the Philistine population may have been a minority.[137][138] However, Louise A. Hitchcock has pointed that other elements of Philistine material culture like their language, art, technology, architecture, rituals and administrative practices are rooted in Cypriot and Minoan civilizations, supporting the view that the Philistines were connected to the Aegean.[90]

Following DNA sequencing using the modern method, DNA testing has concluded sufficient evidence that there was indeed a notable surge of immigration from Aegean,[1] supporting the Biblical/Aegean connection and theory that the Philistine people were initially a migrant group from Europe.

Geographic evolution

[edit]Material culture evidence, primarily pottery styles, indicates that the Philistines originally settled in a few sites in the south, such as Ashkelon, Ashdod and Ekron.[139] It was not until several decades later, about 1150 BC, that they expanded into surrounding areas such as the Yarkon region to the north (the area of modern Jaffa, where there were Philistine farmsteads at Tel Gerisa and Aphek, and a larger settlement at Tel Qasile).[139] Most scholars, therefore, believe that the settlement of the Philistines took place in two stages. In the first, dated to the reign of Ramesses III, they were limited to the coastal plain, the region of the Five Cities; in the second, dated to the collapse of Egyptian hegemony in southern Canaan, their influence spread inland beyond the coast.[140] During the 10th to 7th centuries BC, the distinctiveness of the material culture appears to have been absorbed with that of surrounding peoples.[141]

Early connections

[edit]There is evidence that Cretans traded with Levantine merchants since the Neolithic Minoan era,[142] which increased by the Early Bronze Age.[143] In the Middle Bronze Age, coastal plains in the southern Levant economically prospered due to long-distance exchange with the Aegean, Cypriot and Egyptian civilizations.[144]

The Cretans also influenced the architecture of Middle Bronze Age Canaanite palaces such as Tel Kabri. Dr. Assaf Yasur-Landau of the University of Haifa said that "it was, without doubt, a conscious decision made by the city's rulers who wished to associate with Mediterranean culture and not adopt Syrian and Mesopotamian styles of art like other cities in Canaan did; the Canaanites were living in the Levant and wanted to feel European."[145]

Burial practices

[edit]The Leon Levy Expedition, consisting of archaeologists from Harvard University, Boston College, Wheaton College and Troy University, conducted a 30-year investigation of the burial practices of the Philistines, by excavating a Philistine cemetery containing more than 150 burials dating from the 11th to 8th century BC Tel Ashkelon. In July 2016, the expedition finally announced the results of their excavation.[146]

Archaeological evidence, provided by architecture, burial arrangements, ceramics, and pottery fragments inscribed with non-Semitic writing, indicates that the Philistines were not native to Canaan. Most of the 150 dead were buried in oval-shaped graves, some were interred in ashlar chamber tombs, while there were 4 who were cremated. These burial arrangements were very common to the Aegean cultures, but not to the one indigenous to Canaan. Lawrence Stager of Harvard University believes that Philistines came to Canaan by ships before the Battle of the Delta (c. 1175 BC). DNA was extracted from the skeletons for archaeogenetic population analysis.[147]

The Leon Levy Expedition, which has been going on since 1985, helped break down some of the previous assumptions that the Philistines were uncultured people by having evidence of perfume near the bodies in order for the deceased to smell it in the afterlife.[148]

Population

[edit]The population of the area associated with Philistines is estimated to have been around 25,000 in the 12th century BC, rising to a peak of 30,000 in the 11th century BC.[149] The Canaanite nature of the material culture and toponyms suggest that much of this population was indigenous, such that the migrant element would likely constitute less than half the total, and perhaps much less.[149]

Language

[edit]Virtually nothing is known for certain about the language of the Philistines. Pottery fragments from the period of circa 1500–1000 BC have been found bearing inscriptions in non-Semitic languages, including one in a Cypro-Minoan script.[150] The Bible does not mention any language problems between the Israelites and the Philistines, as it does with other groups up to the Assyrian and Babylonian occupations.[151] Later, under the Achaemenids, Nehemiah 13:23-24 records that when Judean men intermarried women from Moab, Ammon and Philistine cities, half the offspring of Judean marriages with women from Ashdod could speak only their mother tongue, Ašdōdīṯ, not Judean Hebrew (Yehūdīṯ); although by then this language might have been an Aramaic dialect.[41] There is some limited evidence in favour of the assumption that the Philistines were originally Indo-European-speakers, either from Greece or Luwian speakers from the coast of Asia Minor, on the basis of some Philistine-related words found in the Bible not appearing to be related to other Semitic languages.[152] Such theories suggest that the Semitic elements in the language were borrowed from their neighbours in the region. For example, the Philistine word for captain, "seren", may be related to the Greek word tyrannos (thought by linguists to have been borrowed by the Greeks from an Anatolian language, such as Luwian or Lydian[152]). Although most Philistine names are Semitic (such as Ahimelech, Mitinti, Hanun, and Dagon)[151] some of the Philistine names, such as Goliath, Achish, and Phicol, appear to be of non-Semitic origin, and Indo-European etymologies have been suggested. Recent finds of inscriptions written in Hieroglyphic Luwian in Palistin substantiate a connection between the language of the kingdom of Palistin and the Philistines of the southwestern Levant.[153][154][155]

Religion

[edit]The deities worshipped in the area were Baal, Ashteroth (that is, Astarte), Asherah, and Dagon, whose names or variations thereof had already appeared in the earlier attested Canaanite pantheon.[49] The Philistines may also have worshipped Qudshu and Anat.[156] Beelzebub, a supposed hypostasis of Baal, is described in the Hebrew Bible as the patron deity of Ekron, though no explicit attestation of such a god or his worship has thus far been discovered, and the name Baal-zebub itself may be the result of an intentional distortion by the Israelites.[157][158][159] Another name, attested on the Ekron Royal Dedicatory Inscription, is PT[-]YH, unique to the Philistine sphere and possibly representing a goddess in their pantheon,[6] though an exact identity has been subject to scholarly debate.

Although the Bible cites Dagon as the main Philistine god, there is a stark lack of any evidence indicating the Philistines had any particular proclivity to his worship. In fact, no evidence of Dagon worship whatsoever is discernible at Philistine sites, with even theophoric names invoking the deity being unattested in the already limited corpus of known Philistine names. A further assessment of the Iron Age I finds worship of Dagon in any immediate Canaanite context, let alone one which is indisputably Philistine, as seemingly non-existent.[160] Still, Dagon-worship probably wasn't completely unheard of amongst the Philistines, as multiple mentions of a city known as Beth Dagon in Assyrian, Phoenician, and Egyptian sources may imply the god was venerated in at least some parts of Philistia.[160] Furthermore, the inscription of the sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, dating to the 6th century BC, calls Jaffa, a Philistine city, one of the "mighty lands of Dagon",[161] though this does little in the way of clarifying the god's importance to the Philistine pantheon.

The most common material religious artefact finds from Philistine sites are goddess figurines/chairs, sometimes called Ashdoda. This seems to imply a dominant female figure, which is consistent with Ancient Aegean religion.[6]

Economy

[edit]Cities excavated in the area attributed to Philistines give evidence of careful town planning, including industrial zones. The olive industry of Ekron alone includes about 200 olive oil installations. Engineers estimate that the city's production may have been more than 1,000 tons, 30 percent of Israel's present-day production.[127]

There is considerable evidence for a large industry in fermented drink. Finds include breweries, wineries, and retail shops marketing beer and wine. Beer mugs and wine kraters are among the most common pottery finds.[162]

The Philistines also seemed to be experienced metalworkers, as complex wares of gold, bronze, and iron, have been found at Philistine sites as early as the 12th century BC,[163] as well as artisanal weaponry.[164]

See also

[edit]- Museum of Philistine Culture, a museum displaying the major archaeological artifacts from the five ancient Philistine city-states

- Archaeological sites:

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Lords" is a translation of sarnei (סַרְנֵ֣י) in Hebrew. The equivalent in the Greek of the Septuagint is satraps (σατραπείαις).

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Clare Wilson (3 July 2019). "Ancient DNA reveals that Jews' biblical rivals were from Greece". New Scientist.

- ^ a b "Who Were the Philistines, and Where Did They Come From?". 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b Vogazianos, Stephanos (1994). "The philistine emergence and its possible bearing on the appearance and activities of Aegean invaders in the east Mediterranean area at the end of the Mycenaean period". Archaeologia Cypria (Κυπριακή Αρχαιολογία). III (14). University of Cyprus: 22–34. ISSN 0257-1951.

- ^ Russell, Anthony (2009). "Deconstructing Ashdoda: Migration, Hybridisation, and the Philistine Identity". Babesch. 84: 1–15. doi:10.2143/BAB.84.0.2041632.

- ^ Barako, Tristan (2003). "The Changing Perception of the Sea Peoples Phenomenon: Invasion, Migration or Cultural Diffusion?". University of Crete – via Academia.edu.

- ^ a b c Ben-Shlomo, David (2019). "Philistine Cult and Religion According to Archaeological Evidence". Religions. 10 (2): 74. doi:10.3390/rel10020074. ISSN 2077-1444.

- ^ Wylie, Jonathon; Master, Daniel (2020). "The conditions for Philistine ethnogenesis". Ägypten und Levante. XXX: 547–568. doi:10.1553/AEundL30s547. ISSN 1015-5104.

- ^ a b Aaron J. Brody; Roy J. King (2013). "Genetics and the Archaeology of Ancient Israel". Human Biology. 85 (6): 925. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.85.6.0925. ISSN 0018-7143.

- ^ a b St Fleur, Nicholas (3 July 2019). "DNA Begins to Unlock Secrets of the Ancient Philistines". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Meyers 1997, p. 313.

- ^ a b c d e Maeir, Aren M. (2018), Yasur-Landau, Assaf; Cline, Eric H.; Rowan, Yorke (eds.), "Iron Age I Philistines: Entangled Identities in a Transformative Period", The Social Archaeology of the Levant: From Prehistory to the Present, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 320, doi:10.1017/9781316661468.018, ISBN 978-1-107-15668-5, retrieved 24 March 2024

- ^ Raffaele D'Amato; Andrea Salimbeti (2015). Sea Peoples of the Bronze Age Mediterranean c. 1400 BC-1000 BC. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-1-4728-0683-3.

- ^ Hans Wildberger (1979) [1978]. Isaiah 13-27: A Continental Commentary. Translated by Thomas H. Trapp. Fortress Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4514-0934-5.

- ^ Perkins, Larry (2010). "What's in a Name—Proper Names in Greek Exodus". Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period. 41 (4): 447–471. doi:10.1163/157006310X503630. ISSN 0047-2212. JSTOR 24670934.

- ^ "Philistine." Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b "Sea People". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ Cohen, Yoram (2021). "The "Hunger Years" and the "Sea Peoples": Preliminary Observations on the Recently Published Letters from the "House of Urtenu" Archive at Ugarit". In Machinist, Peter; Harris, Robert A.; Berman, Joshua A.; Samet, Nili; Ayali-Darshan, Noga (eds.). Ve-'Ed Ya'aleh (Gen 2:6), Volume 1: Essays in Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies Presented to Edward L. Greenstein. SBL Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-88414-484-7.

- ^ Paine, Lincoln (27 October 2015). The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-101-97035-5.

- ^ Masalha 2018, p. 56: The 3200-year-old documents from Ramesses III, including an inscription dated c. 1150 BC, at the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III at the Medinat Habu Temple in Luxor – one of the best-preserved temples of Egypt – refers to the Peleset among those who fought against Ramesses III (Breasted 2001: 24; also Bruyère 1929‒1930), who reigned from 1186 to 1155 BC.

- ^ "Text of the Papyrus Harris". Specialtyinterests.net. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Killebrew 2005, p. 204.

- ^ a b Israel Finkelstein, Is The Philistine Paradigm Still Viable?, in: Bietak, M., (Ed.), The Synchronisation of Civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B. C. III. Proceedings of the SCIEM 2000 – 2nd Euro- Conference, Vienna, 28th of May–1st of June 2003, Denkschriften der Ge- samtakademie 37, Contributions to the Chronology of the Eastern Mediterranean 9, Vienna 2007, pages 517–524. Quote: "SUMMARY Was there a Sea Peoples migration to the coast of the Levant? Yes. Was it a maritime migration? Possibly. Was there a massive maritime Sea Peoples invasion? Probably not. Did the Philistines settle en-masse in Philistia in the days of Ramesses III? No. Were the Iron I Philistine cities fortified? No. Were the Iron I Philistines organized in a peer-polity system? Probably not. Was there a Philistine Pentapolis system in the Iron I? No. Are the Iron I Philistines the Philistines described in the Bible? No."

- ^ a b Drews 1995, p. 69: "For the modern myth that has replaced it, however, there is [no basis]. Instead of questioning the story of the Philistines Cretan origins, in an attempt to locate a core of historical probability, Maspero took the story at face value and proceeded to inflate it to fantastic dimensions. Believing that the Medinet Habu reliefs, with their ox carts, depict the Philistine nation on the eve of its settlement in Canaan, Maspero imagined a great overland migration. The Philistines moved first from Crete to Caria, he proposed, and then from Caria to Canaan in the time of Ramesses III. Whereas Amos and Jeremiah derived the Philistines directly from Crete, a five-day sail away, Maspero's myth credited them with an itinerary that, while reflecting badly on their intelligence, testified to prodigious physical stamina: the Philistines sail from Crete to Caria, where they abandon their ships and their maritime tradition; the nation then travels in ox carts through seven hundred miles of rough and hostile terrain until it reaches southern Canaan; at that point, far from being debilitated by their trek, the Philistines not only conquer the land and give it their name but come within a hair's breadth of defeating the Egyptian pharaoh himself. Not surprisingly, for the migration from Caria to Canaan imagined by Maspero there is no evidence at all, whether literary, archaeological, or documentary.

Since none of Maspero's national migrations is demonstrable in the Egyptian inscriptions, or in the archaeological or linguistic record, the argument that these migrations did indeed occur has traditionally relied on place-names. These place-names are presented as the source from which were derived the ethnica in Merneptahs and Ramesses inscriptions." - ^ a b Ussishkin 2008, p. 207: "Reconstruction of the Philistine migration and settlement on the basis of the above model is hard to accept. First, it is not supported by any factual evidence. Second, it assumes that the Philistines had at their disposal a large and strong naval force of a kind unknown in this period. Third, in the period immediately following their settlement in Philistia there is hardly any archaeological evidence connecting the Philistine culture and settlement with sea and navigation. Had the Philistines really possessed such a strong naval force and tradition, as suggested by Stager, we would expect to observe these associations in their material culture in later times."

- ^ Killebrew 2005, p. 202.

- ^ a b Avner Raban, "The Philistines in the Western Jezreel Valley", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 284 (November 1991), pp. 17–27, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The American Schools of Oriental Research. doi:10.2307/1357190

- ^ Ben-Shlomo, David. 2011. "Early Iron Age Domestic Material Culture in Philistia and an Eastern Mediterranean Koinי." Pages 183–206 in Household Archaeology in Ancient Israel and Beyond. Assaf Yasur-Landau, Jennie R. Ebeling, and Laura B. Mazow. CHANE 50. Leiden: Brill. DOI: 10.1163/ej.9789004206250.i-452.64. p 202

- ^ Stager, Lawrence (2008). "Stratigraphic Overview." Pages 215–326 in Ashkelon 1: Introduction and Overview. Edited by Lawrence E. Stager, David Schloen, and Daniel M. Master. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. p. 257.

- ^ Millek 2017, pp. 125–126

- ^ Millek 2017, p. 125

- ^ Millek 2017, pp. 120–122

- ^ Millek 2021, p. 62

- ^ Millek 2021, pp. 67–70

- ^ 1 Samuel 13:19–22

- ^ 1 Chronicles 18:1

- ^ a b Maeir 2022, p. 557.

- ^ Masalha 2018, p. 68: In 712, after an uprising by the Philistine city of Ashdod, supported militarily by Egypt, the Assyrian King Sargon II (reigned 722–705 BCE) invaded Pilishte to oust Iamani and annexed the whole region; Philistia was brought under direct Assyrian control, in effect becoming an Assyrian province (Thompson 2016: 165), although the King of Ashdod was allowed to remain on the throne (Galllagher 1995: 1159.

- ^ Naʼaman 2005, p. 145.

- ^ Bernd Schipper, 2010, Egypt and the Kingdom of Judah under Josiah and Jehoiakim, p. 218

- ^ a b Kahn, Dan'el (2023). "The History Leading Up to the Destruction of Judah". The Torah.com.

- ^ a b Peter Machinist (2013). "Biblical Traditions: The Philistines and Israelite History". In Eliezer D. Oren (ed.). The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 53–83., p. 64.

- ^ "Genesis 10:13-14". www.sefaria.org.

- ^ Macalister 1911, p. 14.

- ^ Friedrich Schwally, Die Rasse der Philistäer, in Zeitschrift für Wissenschaftliche Theologie, xxxiv. 103, 1891

- ^ Bernhard Stade, Geschichte des Volkes Israel, 1881

- ^ Cornelis Tiele, De goden der Filistijnen en hun dienst, in Geschiedenis van den godsdienst in de oudheid tot op Alexander den Groote, 1893

- ^ Mathews 2005, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Jobling, David; Rose, Catherine (1996), "Reading as a Philistine", in Mark G. Brett (ed.), Ethnicity and the Bible, Brill, p. 404, ISBN 978-0-391-04126-4,

Rabbinic sources insist that the Philistines of Judges and Samuel were different people altogether from the Philistines of Genesis. (Midrash Tehillim on Psalm 60 (Braude: vol. 1, 513); the issue here is precisely whether Israel should have been obliged, later, to keep the Genesis treaty.) This parallels a shift in the Septuagint's translation of Hebrew pĕlištim. Before Judges, it uses the neutral transliteration phulistiim, but beginning with Judges it switches to the pejorative allophuloi. [Footnote 26: To be precise, Codex Alexandrinus starts using the new translation at the beginning of Judges and uses it invariably thereafter, Vaticanus likewise switches at the beginning of Judges, but reverts to phulistiim on six occasions later in Judges, the last of which is 14:2.]

- ^ a b c Fahlbusch & Bromiley 2005, "Philistines", p. 185.

- ^ a b "Genesis 10 Matthew Poole's Commentary". Biblehub. 2023.

- ^ Genesis 15:18–21

- ^ Deut 7:1, 20:17

- ^ Deuteronomy 2:23

- ^ Exodus 13:17

- ^ Genesis 21:22–27

- ^ Genesis 26:28–29

- ^ Macalister 1911: "There is a peculiarity in the designation of the Philistines in Hebrew which has often been noticed, and which must have a certain significance. In referring to a tribe or nation, the Hebrew writers as a rule either (a) personified an imaginary founder, making his name stand for the tribe supposed to derive from him—e. g. 'Israel' for the Israelites; or (b) used the tribal name in the singular, with the definite article—a usage sometimes transferred to the Authorized Version, as in such familiar phrases as 'the Canaanite was then in the land' (Gen. xii. 6); but more commonly assimilated to the English idiom which requires a plural, as in 'the iniquity of the Amorite[s] is not yet full' (Gen. xv. 16). But in referring to the Philistines, the plural of the ethnic name is always used, and as a rule, the definite article is omitted. A good example is afforded by the name of the Philistine territory above mentioned, 'ereṣ Pelištīm, literally 'the land of Philistines': contrast such an expression as 'ereṣ hak-Kena'anī, literally 'the land of the Canaanite'. A few other names, such as that of the Rephaim, are similarly constructed: and so far as the scanty monuments of Classical Hebrew permit us to judge, it may be said generally that the same usage seems to be followed when there is question of a people not conforming to the model of Semitic (or perhaps we should rather say Aramaean) tribal organization. The Canaanites, Amorites, Jebusites, and the rest, are so closely bound together by the theory of blood-kinship which even yet prevails in the Arabian deserts, that each may logically be spoken of as an individual human unit. No such polity was recognized among the pre-Semitic Rephaim, or the intruding Philistines so that they had to be referred to as an aggregate of human units. This rule, it must be admitted, does not seem to be rigidly maintained; for instance, the name of the pre-Semitic Horites might have been expected to follow the exceptional construction. But a hard-and-fast adhesion to so subtle a distinction, by all the writers who have contributed to the canon of the Hebrew scriptures and by all the scribes who have transmitted their works, is not to be expected. Even in the case of the Philistines, the rule that the definite article should be omitted is broken in eleven places. [Namely Joshua xiii. 2; 1 Sam. iv. 7, vii. 12, xiii. 20, xvii. 51, 52; 2 Sam. v. 19, xxi. 12, 17; 1 Chron. xi. 13; 2 Chron. xxi. 16]"

- ^ Drews 1998, p. 49: "Our names 'Philistia' and 'Philistines' are unfortunate obfuscations, first introduced by the translators of the LXX and made definitive by Jerome's Vulgate. When turning a Hebrew text into Greek, the translators of the LXX might simply—as Josephus was later to do—have Hellenized the Hebrew פְּלִשְׁתִּים as Παλαιστίνοι, and the toponym פְּלִשְׁתִּ as Παλαιστίνη. Instead, they avoided the toponym altogether, turning it into an ethnonym. As for the ethnonym, they chose sometimes to transliterate it (incorrectly aspirating the initial letter, perhaps to compensate for their inability to aspirate the sigma) as φυλιστιιμ, a word that looked exotic rather than familiar, and more often to translate it as ἀλλόφυλοι. Jerome followed the LXX's lead in eradicating the names, 'Palestine' and 'Palestinians', from his Old Testament, a practice adopted in most modern translations of the Bible."

- ^ Drews 1998, p. 51: "The LXX's regular translation of פְּלִשְׁתִּים into ἀλλόφυλοι is significant here. Not a proper name at all, allophyloi is a generic term, meaning something like 'people of other stock'. If we assume, as I think we must, that with their word allophyloi the translators of the LXX tried to convey in Greek what p'lištîm had conveyed in Hebrew, we must conclude that for the worshippers of Yahweh p'lištîm and b'nê yiśrā'ēl were mutually exclusive terms, p'lištîm (or allophyloi) being tantamount to 'non-Judaeans of the Promised Land' when used in a context of the 3rd century BCE, and to 'non-Israelites of the Promised Land' when used in a context of Samson, Saul and David. Unlike an ethnonym, the noun פְּלִשְׁתִּים normally appeared without a definite article."

- ^ Killebrew 2025, p. 88.

- ^ Killebrew 2025, p. 60.

- ^ Alter, Robert (2009). The David Story: A Translation with Commentary of 1 and 2 Samuel. W. W. Norton & Company. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-393-07025-5. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ a b c

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hirsch, Emil G.; Muller, W. Max; Ginzberg, Louis (1901–1906). "Cherethites". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hirsch, Emil G.; Muller, W. Max; Ginzberg, Louis (1901–1906). "Cherethites". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Cheyne and Black, Encyclopedia Biblica

- ^ Amos 1:8

- ^ Amos 9:7

- ^ These particular Amos verses are earliest-witnessed in the Minor-Prophets scroll found in Wadi Murabbaat, "MurXII"; but both are decayed such that whatever stands in for "PLSTYM" is conjectural. [1] Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Read the Bible text :: academic-bible.com". www.academic-bible.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ "Jeremiah 47:4". Mechon-Mamre. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Ezekiel 25:16". Mechon-Mamre. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Amos 1:8". Mechon-Mamre. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Zephaniah 2:5". Mechon-Mamre. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Herzog & Gichon 2006.

- ^ 2 Chronicles 28:18

- ^ 1 Samuel 4:1–10

- ^ 1 Samuel 7:3–14

- ^ 1 Samuel 13:19–21

- ^ 1 Samuel 14

- ^ 1 Samuel 17

- ^ 1 Samuel 31

- ^ 2 Kings 18:5–8

- ^ "Philistine people". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 11 August 2023.

According to biblical tradition (Deuteronomy 2:23; Jeremiah 47:4), the Philistines came from Caphtor (possibly Crete, although there is no archaeological evidence of a Philistine occupation of the island.)

- ^ 1 Chronicles 1:12

- ^ Romey, Kristin. 2016. "Discovery of Philistine Cemetery May Solve Biblical Mystery." National Geographic. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Young, Ian; Rezetko, Robert (2016). Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts. Vol. 1. Routledge. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-134-93578-9.

First, there is widespread understanding that the Philistines, Israel's near neighbours, were of Greek, or more generally, Aegean origin.

- ^ Brug, John Frederick (1978). A Literary and Archaeological Study of the Philistines. British Archaeological Reports. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-86054-337-4.

Many scholars have identified the Philistines and other Sea Peoples as Mycenaean Greeks...

- ^ Arnold, Bill T.; Hess, Richard S. (2014). Ancient Israel's History: An Introduction to Issues and Sources. Baker Academic. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-4412-4634-9.

Most scholars conclude that the Philistines came from the area of Greece and the islands between Greece and Turkey.

- ^ Shai, Itzhaq (2011). "Philistia and the Philistines in the Iron Age IIA". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 127 (2). Deutscher verein zur Erforschung Palästinas: 124–125. JSTOR 41304095.

- ^ Killebrew, Ann E. (2017). "The Philistines during the Period of the Judges". In Ebeling, Jennie R.; Wright, J. Edward; Elliott, Mark Adam; Flesher, Paul V. McCracken (eds.). The Old Testament in Archaeology and History. Baylor University Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-1-4813-0743-7.

... a distinctive Aegean-style material culture associated with the Philistines

- ^ a b Hitchcock, Louise A. (2018). "'All the Cherethites, and all the Pelethites, and all the Gittites' (2 Samuel 2:15-18) – An Up-To-Date Account of the Minoan Connection with the Philistines". In Shai, Itzhaq; Chadwick, Jeffrey R.; Hitchcock, Louise; Dagan, Amit; McKinny, Chris; Uziel, Joe (eds.). Tell it in Gath: Studies in the History and Archaeology of Israel: Essays in Honor of Aren M. Maeir on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday. Zaphon. pp. 304–321. ISBN 978-3-96327-032-1.

- ^ Stone, Bryan Jack (1995). "The Philistines and Acculturation: Culture Change and Ethnic Continuity in the Iron Age". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 298 (298). The University of Chicago Press: 7–32. doi:10.2307/1357082. JSTOR 1357082. S2CID 155280448.

- ^ a b Hincks, Edward (1846). "An Attempt to Ascertain the Number, Names, and Powers, of the Letters of the Hieroglyphic, or Ancient Egyptian Alphabet; Grounded on the Establishment of a New Principle in the Use of Phonetic Characters". The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy. 21 (21): 176. JSTOR 30079013.

- ^ a b Osburn, William (1846). Ancient Egypt, Her Testimony to the Truth of the Bible. Samuel Bagster and sons. p. 107.

- ^ a b Vandersleyen 1985, pp. 40–41 n.9: [Original French]: "À ma connaissance, les plus anciens savants qui ont proposé explicitement l' identification des Pourousta avec les Philistins sont William Osburn Jr., Ancient Egypt, Her Testimony to the Truth of the Bible..., Londres 1846. p. 99. 107. 137. et Edward Hincks, An Attempt to Ascertain the Number, Names, and Powers, of the Letters of the Hieroglyphic or Ancient Egyptian Alphabet, Dublin, 1847, p. 47"

[Translation]: "To my knowledge, the earliest scholars who explicitly proposed the identification of Pourousta with the Philistines are William Osburn Jr., Ancient Egypt, Her Testimony to the Truth of the Bible ..., London, 1846. pp. 99, 107, 137, and Edward Hincks, An Attempt to Ascertain the Number, Names, and Powers, of the Letters of the Alphabet Egyptian Hieroglyphic gold Ancient , Dublin, 1847, p. 47" - ^ a b Vandersleyen 1985, pp. 39–41: "Quand Champollion visita Médinet Habou en juin 1829, il vit ces scénes, lut le nom des Pourosato, sans y reconnaître les Philistins; plus tard, dans son Dictionnaire égyptien et dans sa Grammaire égyptienne, il transcrivit le même nom Polosté ou Pholosté, mais contrairement à ce qu'affirmait Brugsch en 1858 et tous les auteurs postérieurs, Champollion n'a nulle part écrit que ces Pholosté étaient les Philistins de la Bible. [When Champollion visited Medinet Habu in June 1829, he experienced these scenes, reading the name of Pourosato, without recognizing the Philistines; Later, in his Dictionnaire égyptien and its Grammaire égyptienne, he transcribed the same name Polosté or Pholosté, but contrary to the assertion by Brugsch in 1858 and subsequent authors, Champollion has nowhere written that these Pholosté were the Philistines of the Bible.]"

- ^ Dothan & Dothan 1992, pp. 22–23, write of the initial identification: "It was not, however, until the spring of 1829, almost a year after they had arrived in Egypt, that Champollion and his entourage were finally ready to tackle the antiquities of Thebes… The chaotic tangle of ships and sailors, which Denon assumed was a panicked flight into the Indus, was actually a detailed portrayal of a battle at the mouth of the Nile. Because the events of the reign of Ramesses III were unknown from other, the context of this particular war remained a mystery. On his return to Paris, Champollion puzzled over the identity of the various enemies shown in the scene. Since each of them had been carefully labeled with a hieroglyphic inscription, he hoped to match the names with those of ancient tribes and peoples mentioned in Greek and Hebrew texts. Unfortunately, Champollion died in 1832 before he could complete the work, but he did have success with one of the names. […] proved to be none other than the biblical Philistines." Dothan and Dothan's description was incorrect in stating that the naval battle scene (Champollion, Monuments, Plate CCXXII) "carefully labeled with a hieroglyphic inscription" each of the combatants, and Champollion's posthumously published manuscript notes contained only one short paragraph on the naval scene with only the "Fekkaro" and "Schaïratana" identified (Champollion, Monuments, page 368). Dothan and Dothan's following paragraph "Dr. Greene's Unexpected Discovery" incorrectly confused John Beasley Greene with John Baker Stafford Greene [ca]. Champollion did not make a connection to the Philistines in his published work, and Greene did not refer to such a connection in his 1855 work which commented on Champollion (Greene 1855, p. 4)

- ^ Drews 1998, p. 49: "As the Egyptian province in Asia collapsed after the death of Merneptah, and as the area that identified itself as 'Canaan' shrank to the coastal cities beneath the Lebanon range, the names 'Philistia' and 'Philistines' (or, more plainly, 'Palestine' and 'Palestinians') came to the fore"

- ^ a b Drews 1995, p. 55: "A slight shift occurred in 1872, when F. Chabas published the first translation of all the texts relating to the wars of Merneptah and Ramesses III. Chabas found it strange that the Peleset shown in the reliefs were armed and garbed in the same manner as "European" peoples such as the Sicilians and Sardinians, and he therefore argued that these Peleset were not from Philistia after all, but were Aegean Pelasgians. It was this unfortunate suggestion that triggered Maspero's wholesale revision of the entire episode. In his 1873 review of Chabas's book, Maspero agreed that the Peleset of Medinet Habu were accoutred more like Europeans than Semites and also agreed that they were Aegean Pelasgians. But he proposed that it must have been at this very time — in the reign of Ramesses III — that these Pelasgians became Philistines."

- ^ a b Yasur-Landau 2010, p. 180: "It seems, then, that the etymological evidence for the origin of the Philistines and other Sea Peoples can be defined as unfocused and ambiguous at best."

- ^ Rieken, Elisabeth. A. Süel (ed.). "Das Zeichen <sà> im Hieroglyphen-luwischen". Acts of the VIIth International Congress of Hittitology, Çorum, August 25–31, 2008. 2. Ankara: Anıt Matbaa: 651–60.

- ^ a b Rieken, Elisabeth; Yakubovich, Ilya (2010). "The new values of Luwian signs L 319 and L 172". Ipamati Kistamati Pari Tumatimis: Luwian and Hittite Studies Presented to J. David Hawkins on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday. Tel-Aviv: Institute of Archaeology: 199–219 [215–216].

- ^ Hawkins, J. David (2011). "The inscriptions of the Aleppo Temple". Anatolian Studies. 61: 35–54. doi:10.1017/s0066154600008772. S2CID 162387945.

- ^ Ilya Yakubovich (2015). "Phoenician and Luwian in Early Iron Age Cilicia". Anatolian Studies. 65: 35–53. doi:10.1017/s0066154615000010. S2CID 162771440., 38

- ^ Inscription TELL TAYINAT 1: Hawkins, J. David (2000). Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions 1. Inscriptions of the Iron Age. Berlin: de Gruyter. p. 2.366.

- ^ Bunnens, Guy (2006). A New Luwian Stele and the Cult of the Storm-god at Til Barsib-Masuwari. Tell Ahmar, Volume 2. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 978-90-429-1817-7. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Trevor Bryce (6 March 2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. OUP Oxford. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- ^ Ann E. Killebrew (21 April 2013). The Philistines and Other "Sea Peoples" in Text and Archaeology. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 662. ISBN 978-1-58983-721-8.

- ^ Salner, Omri (17 December 2014). "The History of King David in Light of New Epigraphic and Archeological Data". Haifa University. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ See Before and After the Storm, Crisis Years in Anatolia and Syria between the Fall of the Hittite Empire and the Beginning of a New Era (c. 1220 – 1000 BCE), A Symposium in Memory of Itamar Singer, University of Pavia p. 7+8[dead link]

- ^ Jones 1972, pp. 343–350.

- ^ Jones, Allen H. (1975). Bronze Age Civilization: The Philistines and the Danites. Public Affairs Press. pp. VI. ISBN 978-0-685-57333-4.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Na'aman, Nadav (1994). From Nomadism to Monarchy: Archaeological and Historical Aspects of Early Israel. Ben Zvi Institute for the Study of Jewish Communities in the East. p. 336. ISBN 978-1-880317-20-4.

- ^ a b c Feldman, Michal; Master, Daniel M.; Bianco, Raffaela A.; Burri, Marta; Stockhammer, Philipp W.; Mittnik, Alissa; Aja, Adam J.; Jeong, Choongwon; Krause, Johannes (3 July 2019). "Ancient DNA sheds light on the genetic origins of early Iron Age Philistines". Science Advances. 5 (7) eaax0061. Bibcode:2019SciA....5...61F. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax0061. PMC 6609216. PMID 31281897.

- ^ "Ancient DNA reveals the roots of the Biblical Philistines". Nature. 571 (7764): 149. 4 July 2019. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02081-x. S2CID 195847736.

- ^ "Know thine enemy: DNA study solves ancient riddle of origins of the Philistines". The Times of Israel.

- ^ "Ancient DNA may reveal origin of the Philistines". National Geographic Society. 3 July 2019. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019.

- ^ Joshua 13:3

- ^ 1 Samuel 6:17

- ^ Gösta Werner Ahlström (1993). The History of Ancient Palestine. Fortress Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-8006-2770-6.

- ^ Levin, Yigal (2017). "Gath of the Philistines in the Bible and on the Ground: The Historical Geography of Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath". Near Eastern Archaeology. 80 (4): 232–240. doi:10.5615/neareastarch.80.4.0232. ISSN 1094-2076.

- ^ Trevor Bryce (10 September 2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. Routledge. p. 790. ISBN 978-1-134-15907-9.

- ^ Killebrew, Ann E. (2013), "The Philistines and Other "Sea Peoples" in Text and Archaeology", Society of Biblical Literature Archaeology and biblical studies, vol. 15, Society of Biblical Lit, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-58983-721-8. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the French Egyptologist G. Maspero (1896), the somewhat misleading term "Sea Peoples" encompasses the ethnonyms Lukka, Sherden, Shekelesh, Teresh, Eqwesh, Denyen, Sikil / Tjekker, Weshesh, and Peleset (Philistines). [Footnote: The modern term "Sea Peoples" refers to peoples that appear in several New Kingdom Egyptian texts as originating from "islands" (tables 1-2; Adams and Cohen, this volume; see, e.g., Drews 1993, 57 for a summary). The use of quotation marks in association with the term "Sea Peoples" in our title is intended to draw attention to the problematic nature of this commonly used term. It is noteworthy that the designation "of the sea" appears only in relation to the Sherden, Shekelesh, and Eqwesh. Subsequently, this term was applied somewhat indiscriminately to several additional ethnonyms, including the Philistines, who are portrayed in their earliest appearance as invaders from the north during the reigns of Merenptah and Ramesses Ill (see, e.g., Sandars 1978; Redford 1992, 243, n. 14; for a recent review of the primary and secondary literature, see Woudhuizen 2006). Hencefore the term Sea Peoples will appear without quotation marks.]"

- ^ Drews 1995, p. 48: "The thesis that a great "migration of the Sea Peoples" occurred ca. 1200 B.C. is supposedly based on Egyptian inscriptions, one from the reign of Merneptah and another from the reign of Ramesses III. Yet in the inscriptions themselves, such a migration nowhere appears. After reviewing what the Egyptian texts have to say about 'the sea peoples', one Egyptologist (Wolfgang Helck) recently remarked that although some things are unclear, "eins ist aber sicher: Nach den agyptischen Texten haben wir es nicht mit einer 'Volkerwanderung' zu tun." Thus the migration hypothesis is based not on the inscriptions themselves but on their interpretation."

- ^ Redford 1992, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e Killebrew 2005, p. 202.

- ^ Ehrlich 1996, p. 9.

- ^ a b "Philistines | Follow The Rabbi". followtherabbi.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Killebrew 2005, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Ehrlich 1996, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ehrlich 1996, p. 8 (Footnote #42).

- ^ "Philistine | Definition, People, Homeland, & Facts | Britannica". 27 August 2024.

- ^ Killebrew 2005, p. 230.

- ^ Maeir 2005, pp. 528–536.

- ^ Levy 1998, Chapter 20: Lawrence E. Stager, "The Impact of the Sea Peoples in Canaan (1185–1050 BCE)", p. 344.

- ^ Stager, Lawrence. "When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon". Biblical Archaeological Review. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Schloen, David (30 July 2007). "Recent Discoveries at Ashkelon". The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 2 April 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Ehrlich 1996, p. 10: "The difficulty of associating pots with peoples or ethnic groups has often been commented on. Nonetheless, the association of the Philistines with the Iron Age I bichrome pottery bearing their name is most often taken for granted. Although scholars have backed off from postulating that every site with bichrome pottery was under Philistine control, the ethnic association remains... A cautionary note has, however, been sounded in particular by Brug, Bunimovitz, H. Weippert, and Noort, among others. In essence, their theories rest on the fact that even among sites in the Philistine heartland, the supposed Philistine pottery does not represent the major portion of the finds... While not denying Cypriote and/or Aegean/ Mycenean influence in the material cultural traditions of coastal Canaan in the early Iron Age, in addition to that of Egyptian and local Canaanite traditions, the above named "minimalist" scholars emphasize the continuities between the ages and not the differences. As H. Weippert has stated, "Könige kommen, Könige gehen, aber die Kochtöpfe bleiben." In regard to the bichrome pottery, she follows Galling and speculates that it was produced by a family or families of Cypriote potters who followed their markets and immigrated into Canaan once the preexisting trade connections had been severed. The find at Tell Qasile of both bichrome and Canaanite types originating in the same pottery workshop would appear to indicate that the ethnic identification of the potters is at best an open question. At any rate, it cannot be facilely assumed that all bichrome ware was produced by "ethnic" Philistines. Thus Bunimovitz's suggestion to refer to "Philistia pottery" rather than to "Philistine" must be given serious consideration... What holds true for the pottery of Philistia also holds true for other aspects of the regional material culture. Whereas Aegean cultural influence cannot be denied, the continuity with the Late Bronze traditions in Philistia has increasingly come to attention. A number of Iron Age I features which were thought to be imported by the Philistines have been shown to have Late Bronze Age antecedents. It would hence appear that the Philistines of foreign (or "Philistine") origin were the minority in Philistia."

- ^ Gloria London (2003). "Ethnicity and Material Culture". In Suzanne Richard (ed.). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader. Eisenbrauns. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5.

- ^ a b Fantalkin & Yasur-Landau 2008, Yuval Gadot, "Continuity and Change in the Late Bronze to Iron Age Transition in Israel's Coastal Plain: A Long-Term Perspective", pp. 63–64: "Based on material culture studies, we know that the Philistines initially immigrated only to the southern Coastal Plain".

- ^ Grabbe 2008, p. 213.

- ^ Killebrew 2005, p. 234: "During the Iron II (tenth-seventh centuries B.C.E. ), the Philistines completed the process of acculturation with the surrounding indigenous culture (Stone 1995). By the end of the Iron II, the Philistines had lost much of their distinctiveness as expressed in their material culture (see Gitin 1998; 2003; 2004 and bibliography there). My suggested chronological framework for Philistine acculturation spans the tenth to seventh centuries B.C.E. (Tel Miqne-Ekron Strata IV-I; Ashdod Strata X-VI).".

- ^ Kieser, D. "CHAPTER 1: The Dawn of the Bronze Age – The Aegean in the 3rd Millennium" (PDF). Unisa International Repository.

- ^ Shelmerdine, Cynthia W. (2010). The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 209–229. ISBN 978-1-139-00189-2.

- ^ Marcus, Ezra S.; Porath, Yosef; Paley, Samuel M. (2008). "THE EARLY MIDDLE BRONZE AGE IIa PHASES AT TEL IFSHAR AND THEIR EXTERNAL RELATIONS". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 18: 221–244. doi:10.1553/AEundL18s221. JSTOR 23788614.

- ^ "Remains of Minoan fresco found at Tel Kabri"; "Remains Of Minoan-Style Painting Discovered During Excavations of Canaanite Palace", ScienceDaily, 7 December 2009