Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Qajar Iran

View on Wikipedia

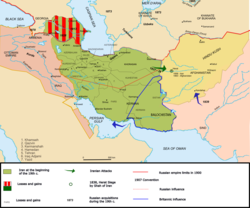

The Guarded Domains of Iran,[a] alternatively the Sublime State of Iran[b] and commonly called Qajar Iran, Qajar Persia or the Qajar Empire, was the Iranian state[8] under the rule of the Qajar dynasty, which was of Turkic origin,[9][10][11] specifically from the Qajar tribe, from 1789 to 1925.[8][12] The Qajar family played a pivotal role in the Unification of Iran (1779–1796), deposing Lotf 'Ali Khan, the last Shah of the Zand dynasty, and re-asserted Iranian sovereignty over large parts of the Caucasus. In 1796, Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar seized Mashhad with ease,[13] putting an end to the Afsharid dynasty. He was formally crowned as Shah after his punitive campaign against Iran's Georgian subjects.[14]

Key Information

In the Caucasus, the Qajar dynasty permanently lost much territory[15] to the Russian Empire over the course of the 19th century, comprising modern-day eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan, and Armenia.[16] Despite its territorial losses, Qajar Iran reinvented the Iranian notion of kingship[17] and maintained relative political independence, but faced major challenges to its sovereignty, predominantly from the Russian and British empires. Foreign advisers became powerbrokers in the court and military. They eventually partitioned Qajar Iran in the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention, carving out Russian and British influence zones and a neutral zone.[18][19][20]

In the early 20th century, the Persian Constitutional Revolution created an elected parliament or Majles, and sought the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, deposing Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar for Ahmad Shah Qajar, but many of the constitutional reforms were reversed by an intervention led by the Russian Empire.[18][21] Qajar Iran's territorial integrity was further weakened during the Persian campaign of World War I and the invasion by the Ottoman Empire. Four years after the 1921 Persian coup d'état, the military officer Reza Shah took power in 1925, thus establishing the Pahlavi dynasty, the last Iranian royal dynasty.

Name

[edit]Since the Safavid era, Mamâlek-e Mahruse-ye Irân (Guarded Domains of Iran) was the common and official name of Iran.[22][23] The idea of the Guarded Domains illustrated a feeling of territorial and political uniformity in a society where the Persian language, culture, monarchy, and Shia Islam became integral elements of the developing national identity.[24] The concept presumably had started to form under the Mongol Ilkhanate in the late 13th century, a period in which regional actions, trade, written culture, and partly Shia Islam, contributed to the establishment of the early modern Persianate world.[25] Its shortened variant was mamalik-i Iran ("Domains of Iran"), most commonly used in the writings from Qajar Iran.[26]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

A late legend holds that the Qajars first came to Iran in the 11th-century along with other Oghuz Turkic clans. However, the Qajars neither appear in the Oghuz tribal lists of Mahmud al-Kashgari nor Rashid al-Din Hamadani. It has been speculated that the Qajars were originally part of a larger tribal group, with the Bayats often considered the most likely tribe from which they later separated. According to the same late legend, the Qajar tribe's namesake ancestor was Qajar Noyan, said to be the son of a Mongol named Sartuq Noyan, who reportedly served as atabeg to the Ilkhanate ruler Arghun (r. 1284–1291). This legend also claims that the Turco-Mongol ruler Timur (r. 1370–1405) was descended from Qajar Noyan.[27] Based on the claims of the legend, Iranologist Gavin R. G. Hambly reconstructed the early history of the Qajars in a hypothetical manner, suggesting that they immigrated towards Anatolia or Syria following the collapse of the Ilkhanate in 1335. Then, during the late 15th century, the Qajars resettled in the historical region of Azerbaijan, becoming affiliated with the neighbouring Erivan, Ganja and Karabakh.[28] Like the other Oghuz tribes in Azerbaijan and eastern Anatolia during the rule of the Aq Qoyunlu, the Qajars likely also converted to Shia Islam and adopted the teachings of the Safavid order.[29]

The Qajar tribe first started to gain prominence during the establishment of the Safavids.[29] When Ismail led the 7,000 tribal soldiers on his successful expedition from Erzincan to Shirvan in 1500/1501, a contingent of Qajars was among them. After this, they emerged as a prominent group within the Qizilbash confederacy,[30] who were made up of Turkoman warriors and served as the main force of the Safavid military.[31] Despite being smaller than other tribes, the Qajars continued to play a major role in important events during the 16th century.[32]

The Safavids "left Arran (present-day Republic of Azerbaijan) to local Turkic khans",[33] and, "in 1554 Ganja was governed by Shahverdi Soltan Ziyadoglu Qajar, whose family came to govern Karabakh in southern Arran".[34] Qajars filled a number of diplomatic missions and governorships in the 16–17th centuries for the Safavids. The Qajars were resettled by Shah Abbas I throughout Iran. The great number of them also settled in Astarabad (present-day Gorgan, Iran) near the south-eastern corner of the Caspian Sea,[9] and it would be this branch of Qajars that would rise to power. The immediate ancestor of the Qajar dynasty, Shah Qoli Khan of the Quvanlu of Ganja, married into the Quvanlu Qajars of Astarabad. His son, Fath Ali Khan (born c. 1685–1693) was a renowned military commander during the rule of the Safavid shahs Sultan Husayn and Tahmasp II. He was killed in 1726. Fath Ali Khan's son Mohammad Hasan Khan Qajar (1722–1758) was the father of Mohammad Khan Qajar and Hossein Qoli Khan Qajar (Jahansouz Shah), father of "Baba Khan," the future Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. Mohammad Hasan Khan was killed on the orders of Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty.

Within 126 years between the demise of the Safavid state and the rise of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, the Qajars had evolved from a shepherd-warrior tribe with strongholds in northern Persia into a Persian dynasty with all the trappings of a Perso-Islamic monarchy.[8]

Rise to power

[edit]"Like virtually every dynasty that ruled Persia since the 11th century, the Qajars came to power with the backing of Turkic tribal forces, while using educated Persians in their bureaucracy".[35] Among these Turkic tribes, however, Turkmens of Iran played the most prominent role in bringing Qajars to power.[36] In 1779, following the death of Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty, Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, the leader of the Qajars, set out to reunify Iran. Agha Mohammad Khan was known as one of the cruelest kings, even by the standards of 18th-century Iran.[9] In his quest for power, he razed cities, massacred entire populations, and blinded some 20,000 men in the city of Kerman because the local populace had chosen to defend the city against his siege.[9]

The Qajar armies at that time were mostly composed of Turkoman warriors and Georgian slaves.[37] By 1794, Agha Mohammad Khan had eliminated all his rivals, including Lotf Ali Khan, the last of the Zand dynasty. He reestablished Iranian control over the territories in the entire Caucasus. Agha Mohammad established his capital at Tehran, a town near the ruins of the ancient city of Rayy. In 1796, he was formally crowned as shah. In 1797, Agha Mohammad Khan was assassinated in Shusha, the capital of Karabakh Khanate, and was succeeded by his nephew, Fath-Ali Shah Qajar.

Reconquest of Georgia and the rest of the Caucasus

[edit]In 1744, Nader Shah had granted the kingship of the Kartli and Kakheti to Teimuraz II and his son Erekle II (Heraclius II) respectively, as a reward for their loyalty.[38] When Nader Shah died in 1747, they capitalized on the chaos that had erupted in mainland Iran, and declared de facto independence. After Teimuraz II died in 1762, Erekle II assumed control over Kartli, and united the two kingdoms in a personal union as the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, becoming the first Georgian ruler to preside over a politically unified eastern Georgia in three centuries.[39] At about the same time, Karim Khan Zand had ascended the Iranian throne; Erekle II quickly tendered his de jure submission to the new Iranian ruler, however, de facto, he remained autonomous.[40][41] In 1783, Erekle II placed his kingdom under the protection of the Russian Empire in the Treaty of Georgievsk. In the last few decades of the 18th century, Georgia had become a more important element in Russo-Iranian relations than some provinces in northern mainland Iran, such as Mazandaran or even Gilan.[42] Unlike Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, the then-ruling monarch of Russia, viewed Georgia as a pivot for her Caucasian policy, as Russia's new aspirations were to use it as a base of operations against both Iran and the Ottoman Empire,[43] both immediate bordering geopolitical rivals of Russia. On top of that, having another port on the Georgian coast of the Black Sea would be ideal.[42] A limited Russian contingent of two infantry battalions with four artillery pieces arrived in Tbilisi in 1784,[40] but was withdrawn in 1787, despite the frantic protests of the Georgians, as a new war against Ottoman Turkey had started on a different front.[40]

The consequences of these events came a few years later when a strong new Iranian dynasty under the Qajars emerged victorious in the protracted power struggle in Iran. Their head, Agha Mohammad Khan, as his first objective,[44] resolved to bring the Caucasus again fully under the Persian orbit. For Agha Mohammad Khan, the resubjugation and reintegration of Georgia into the Iranian empire was part of the same process that had brought Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tabriz under his rule.[40] He viewed, like the Safavids and Nader Shah before him, the territories no different from the territories in mainland Iran. Georgia was a province of Iran the same way Khorasan was.[40] As The Cambridge History of Iran states, its permanent secession was inconceivable and had to be resisted in the same way as one would resist an attempt at the separation of Fars or Gilan.[40] It was therefore natural for Agha Mohammad Khan to perform whatever necessary means in the Caucasus in order to subdue and reincorporate the recently lost regions following Nader Shah's death and the demise of the Zands, including putting down what in Iranian eyes was seen as treason on the part of the vali of Georgia.[40]

Having secured northern, western, and central Iran and having found a temporary respite from their internal quarrels, the Iranians demanded that Erekle II renounce his treaty with Russia and once again acknowledge Iranian suzerainty,[44] in return for peace and the security of his kingdom. The Ottomans, Iran's neighboring rival, recognized the latter's rights over Kartli and Kakheti for the first time in four centuries.[45] Erekle appealed then to his theoretical protector, Empress Catherine II of Russia, asking for at least 3,000 Russian troops,[45] but he was ignored, leaving Georgia to fend off the Iranian threat alone.[46] Nevertheless, Erekle II still rejected Agha Mohammad Khan's ultimatum.[47]

In August 1795, Agha Mohammad Khan crossed the Aras River, and after a turn of events by which he gathered more support from his subordinate khans of Erivan and Ganja, and having re-secured the territories up to including parts of Dagestan in the north and up to the westernmost border of modern-day Armenia in the west, he sent Erekle the last ultimatum, which he also declined, but, sent couriers to St.Petersburg. Gudovich, who sat in Georgiyevsk at the time, instructed Erekle to avoid "expense and fuss",[45] while Erekle, together with Solomon II and some Imeretians headed southwards of Tbilisi to fend off the Iranians.[45]

With half of the troop's Agha Mohammad Khan crossed the Aras river with, he now marched directly upon Tbilisi, where it commenced into a huge battle between the Iranian and Georgian armies. Erekle had managed to mobilize some 5,000 troops, including some 2,000 from neighboring Imereti under its King Solomon II. The Georgians, hopelessly outnumbered, were eventually defeated despite stiff resistance. In a few hours, the Iranian king Agha Mohammad Khan was in full control of the Georgian capital. The Iranian army marched back laden with spoil and carrying off many thousands of captives.[46][48][49]

By this, after the conquest of Tbilisi and being in effective control of eastern Georgia,[14][50] Agha Mohammad was formally crowned Shah in 1796 in the Mughan plain.[14] As The Cambridge History of Iran notes; "Russia's client, Georgia, had been punished, and Russia's prestige, damaged." Erekle II returned to Tbilisi to rebuild the city, but the destruction of his capital was a death blow to his hopes and projects. Upon learning of the fall of Tbilisi General Gudovich put the blame on the Georgians themselves.[51] To restore Russian prestige, Catherine II declared war on Iran, upon the proposal of Gudovich,[51] and sent an army under Valerian Zubov to the Qajar possessions on April of that year, but the new Tsar Paul I, who succeeded Catherine in November, shortly recalled it.

Agha Mohammad Shah was later assassinated while preparing a second expedition against Georgia in 1797 in Shusha.[51] Reassessment of Iranian hegemony over Georgia did not last long; in 1799 the Russians marched into Tbilisi, two years after Agha Mohammad Khan's death.[52] The next two years were a time of muddle and confusion, and the weakened and devastated Georgian kingdom, with its capital half in ruins, was easily absorbed by Russia in 1801.[46][47] As Iran could not permit or allow the cession of Transcaucasia and Dagestan, which had formed part of the concept of Iran for centuries,[15] it would also directly lead up to the wars of even several years later, namely the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813) and Russo-Persian War (1826–1828), which would eventually prove for the irrevocable forced cession of aforementioned regions to Imperial Russia per the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828), as the ancient ties could only be severed by a superior force from outside.[15] It was therefore also inevitable that Agha Mohammad Khan's successor, Fath Ali Shah (under whom Iran would lead the two above-mentioned wars) would follow the same policy of restoring Iranian central authority north of the Aras and Kura rivers.[15]

Wars with Russia and irrevocable loss of territories

[edit]

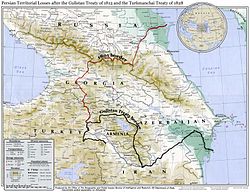

On 12 September 1801, four years after Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar's death, the Russians capitalized on the moment, and annexed Kartli-Kakheti (eastern Georgia).[53][54] In 1804, the Russians invaded and sacked the Iranian town of Ganja, massacring and expelling thousands of its inhabitants,[55] thereby beginning the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813.[56] Under Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797–1834), the Qajars set out to fight against the invading Russian Empire, who were keen to take the Iranian territories in the region.[57] This period marked the beginning of significant economic and military encroachments upon Iranian interests during the colonial era. The Qajar army suffered a major military defeat in the war, and under the terms of the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, Iran was forced to cede most of its Caucasian territories comprising modern-day Georgia, Dagestan, and most of Azerbaijan.[16]

About a decade later, in violation of the Gulistan Treaty, the Russians invaded Iran's Erivan Khanate.[58][59] This sparked the final bout of hostilities between the two; the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828. It ended even more disastrously for Qajar Iran with temporary occupation of Tabriz and the signing of the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828, acknowledging Russian sovereignty over the entire South Caucasus and Dagestan, as well as therefore the ceding of what is nowadays Armenia and the remaining part of Republic of Azerbaijan;[16] the new border between neighboring Russia and Iran were set at the Aras River. Iran had by these two treaties, in the course of the 19th century, irrevocably lost the territories which had formed part of the concept of Iran for centuries.[15] The territories lying to the north of the Aras River—including the lands of present-day Azerbaijan, eastern Georgia, Dagestan, and Armenia—remained part of Iran until their occupation by Russia in the course of the 19th century.[16][60][61][62][63][64][65]

As a further direct result and consequence of the Gulistan and Turkmenchay treaties of 1813 and 1828 respectively, the formerly Iranian territories became part of Russia for around the next 180 years, except Dagestan, which has remained a Russian possession ever since. Out of the greater part of the territory, six separate nations would be formed through the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, namely Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and three generally unrecognized republics Abkhazia, Artsakh and South Ossetia claimed by Georgia. Lastly and equally important, as a result of Russia's imposing of the two treaties, It also decisively parted the Azerbaijanis and Talysh[66] ever since between two nations.

-

Battle of Sultanabad, 13 February 1812. State Hermitage Museum.

-

Storming of Lankaran, 13 January 1813. Franz Roubaud.

-

Battle of Ganja, 1826. Franz Roubaud. Part of the collection of the Museum for History, Baku.

Migration of Caucasian Muslims

[edit]Following the official losing of the aforementioned vast territories in the Caucasus, major demographic shifts were bound to take place. Solidly Persian-speaking territories of Iran were lost, with all its inhabitants in it. Following the 1804–1814 War, but also per the 1826–1828 war which ceded the last territories, large migrations, so-called Caucasian Muhajirs, set off to migrate to mainland Iran. Some of these groups included the Ayrums, Qarapapaqs, Circassians, Shia Lezgins, and other Transcaucasian Muslims.[67]

Through the Battle of Ganja of 1804 during the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813), many thousands of Ayrums and Qarapapaqs were settled in Tabriz. During the remaining part of the 1804–1813 war, as well as through the 1826–1828 war, the absolute bulk of the Ayrums and Qarapapaqs that were still remaining in newly conquered Russian territories were settled in and migrated to Solduz (in modern-day Iran's West Azerbaijan province).[68] As The Cambridge History of Iran states; "The steady encroachment of Russian troops along the frontier in the Caucasus, General Yermolov's brutal punitive expeditions and misgovernment, drove large numbers of Muslims, and even some Georgian Christians, into exile in Iran."[69]

In 1864 until the early 20th century, another mass expulsion took place of Caucasian Muslims as a result of the Russian victory in the Caucasian War. Others simply voluntarily refused to live under Christian Russian rule, and thus disembarked for Turkey or Iran. These migrations once again, towards Iran, included masses of Caucasian Azerbaijanis, other Transcaucasian Muslims, as well as many North Caucasian Muslims, such as Circassians, Shia Lezgins and Laks.[67][70] Many of these migrants would prove to play a pivotal role in further Iranian history, as they formed most of the ranks of the Persian Cossack Brigade, which was also to be established in the late 19th century.[71] The initial ranks of the brigade would be entirely composed of Circassians and other Caucasian Muhajirs.[71] This brigade would prove decisive in the following decades to come in Qajar history.

Furthermore, the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay included the official rights for the Russian Empire to encourage settling of Armenians from Iran in the newly conquered Russian territories.[72][73] Until the mid-fourteenth century, Armenians had constituted a majority in Eastern Armenia.[74] At the close of the fourteenth century, after Timur's campaigns, Islam had become the dominant faith, and Armenians became a minority in Eastern Armenia.[74] After centuries of constant warfare on the Armenian Plateau, many Armenians chose to emigrate and settle elsewhere. Following Shah Abbas I's massive relocation of Armenians and Muslims in 1604–05,[75] their numbers dwindled even further.

At the time of the Russian invasion of Iran, some 80% of the population of Erivan Khanate in Iranian Armenia were Muslims (Persians, Turkics, and Kurds) whereas Christian Armenians constituted a minority of about 20%.[76] As a result of the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Iran was forced to cede Iranian Armenia (which also constituted the present-day Armenia), to the Russians.[77][78] After the Russian administration took hold of Iranian Armenia, the ethnic make-up shifted, and thus for the first time in more than four centuries, ethnic Armenians started to form a majority once again in one part of historic Armenia.[79]

Development and decline

[edit]

Fath Ali Shah's reign saw increased diplomatic contacts with the West and the beginning of intense European diplomatic rivalries over Iran. His grandson Mohammad Shah, who fell under the Russian influence and made two unsuccessful attempts to capture Herat, succeeded him in 1834. When Mohammad Shah died in 1848 the succession passed to his son Naser al-Din, who proved to be the ablest and most successful of the Qajar sovereigns. He founded the first modern hospital in Iran.[80]

During Naser al-Din Shah's reign, Western science, technology, and educational methods were introduced into Iran and the country's modernization was begun. Naser al-Din Shah tried to exploit the mutual distrust between Great Britain and Russia to preserve Iran's independence, but foreign interference and territorial encroachment increased under his rule. He was not able to prevent Britain and Russia from encroaching into regions of traditional Iranian influence.

In 1856, during the Anglo-Persian War, Britain prevented Iran from reasserting control over Herat. The city had been part of Iran in Safavid times, but Herat had been under Durrani rule since the mid–18th century. Britain also extended its control to other areas of the Persian Gulf during the 19th century. Meanwhile, by 1881, Russia had completed its conquest of present-day Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, bringing Russia's frontier to Persia's northeastern borders and severing historic Iranian ties to the cities of Bukhara, Merv and Samarqand. With the conclusion of the Treaty of Akhal on 21 September 1881, Iran ceased any claim to all parts of Turkestan and Transoxiana, setting the Atrek River as the new boundary with Imperial Russia. Hence Merv, Sarakhs, Ashgabat, and the surrounding areas were transferred to Russian control under the command of General Alexander Komarov in 1884.[81] Several trade concessions by the Iranian government put economic affairs largely under British control. By the late 19th century, many Iranians believed that their rulers were beholden to foreign interests.

Mirza Taghi Khan Amir Kabir, was the young prince Naser al-Din's advisor and constable. With the death of Mohammad Shah in 1848, Mirza Taqi was largely responsible for ensuring the crown prince's succession to the throne. When Nasser ed-Din succeeded to the throne, Amir Nezam was awarded the position of the prime minister and the title of Amir Kabir, the Great Ruler.

At that time, Iran was nearly bankrupt. During the next two and a half years Amir Kabir initiated important reforms in virtually all sectors of society. Government expenditure was slashed, and a distinction was made between the private and public purses. The instruments of central administration were overhauled, and Amir Kabir assumed responsibility for all areas of the bureaucracy. There were Bahai revolts and a revolt in Khorasan at the time but were crushed under Amir Kabir.[82] Foreign interference in Iran's domestic affairs was curtailed, and foreign trade was encouraged. Public works such as the bazaar in Tehran were undertaken. Amir Kabir issued an edict banning ornate and excessively formal writing in government documents; the beginning of a modern Persian prose style dates from this time.

One of the greatest achievements of Amir Kabir was the building of Dar ol Fonoon in 1851, the first modern university in Iran and the Middle East. Dar-ol-Fonoon was established for training a new cadre of administrators and acquainting them with Western techniques. It marked the beginning of modern education in Iran.[83] Amir Kabir ordered the school to be built on the edge of the city so it could be expanded as needed. He hired French and Russian instructors as well as Iranians to teach subjects as different as Language, Medicine, Law, Geography, History, Economics, and Engineering, amongst numerous others.[83] Unfortunately, Amir Kabir did not live long enough to see his greatest monument completed, but it still stands in Tehran as a sign of a great man's ideas for the future of his country.

These reforms antagonized various notables who had been excluded from the government. They regarded the Amir Kabir as a social upstart and a threat to their interests, and they formed a coalition against him, in which the queen mother was active. She convinced the young shah that Amir Kabir wanted to usurp the throne. In October 1851, the shah dismissed him and exiled him to Kashan, where he was murdered on the shah's orders. Through his marriage to Ezzat od-Doleh, Amir Kabir had been the brother-in-law of the shah.

Qajar Iran would become a victim of the Great Game between Russia and Britain for influence over central Asia. As the Qajar state's sovereignty was challenged this took the form of military conquests, diplomatic intrigues, and the competition of trade goods between two foreign empires.[19]: 20, 74 Ever since the 1828 Treaty of Turkmanchay, Russia had received territorial domination in Iran. With the Romanovs shifting to a policy of 'informal support' for the weakened Qajar dynasty — continuing to place pressure with advances in the largely nomadic Turkestan, a crucial frontier territory of the Qajars — this Russian domination of Iran continued for nearly a century.[18][84] The Iranian monarchy became more of a symbolic concept in which Russian diplomats were themselves powerbrokers in Iran and the monarchy was dependent on British and Russian loans for funds.[18]

In 1879, the establishment of the Cossack Brigade by Russian officers gave the Russian Empire influence over the modernization of the Qajar army. This influence was especially pronounced because the Iranian monarchy's legitimacy was predicated on an image of military prowess, first Turkic and then European-influenced.[18][85] By the 1890s, Russian tutors, doctors and officers were prominent at the Shah's court, influencing policy personally.[18][86] Russia and Britain had competing investments in the industrialisation of Iran including roads and telegraph lines,[87] as a way to profit and extend their influence. However, until 1907 the Great Game rivalry was so pronounced that mutual British and Russian demands to the Shah to exclude the other, blocked all railroad construction in Iran at the end of the 19th century.[19]: 20 In 1907 the British and Russian Empires partitioned Iran into spheres of influence with the Anglo-Russian Convention.

Constitutional Revolution

[edit]

When Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar was assassinated by Mirza Reza Kermani in 1896,[88] the crown passed to his son Mozaffar al-Din.[88] Mozaffar al-Din Shah was regarded as a moderate, but his reign was marked by ineffectiveness. Extravagant royal expenditures, coupled with the state’s limited capacity to generate revenue, intensified the financial difficulties of the Qajar dynasty. To address these problems, the shah secured two major loans from Russia, partly to finance his personal trips to Europe. Public discontent grew as the shah granted concessions—including road-building monopolies and the right to collect customs duties—to European interests in exchange for substantial payments to himself and his officials. These developments fueled popular demands to restrict arbitrary royal authority and to establish governance based on the rule of law, while also reflecting broader anxieties over the expansion of foreign influence.

The failure of the shah to adequately address the grievances of the religious establishment, the merchant class, and other social groups led, in January 1906, to the merchants and clerical leaders seeking sanctuary in mosques in Tehran and beyond the capital in order to avoid probable arrest. When the shah subsequently reneged on his earlier promise to authorize the establishment of a house of justice—a consultative assembly—approximately 10,000 individuals, led by the merchant community, took sanctuary in June within the compound of the British legation in Tehran. In August 1906, under mounting pressure, the shah issued a decree pledging the granting of a constitution. In October, an elected assembly convened and drew up a constitution that provided for strict limitations on royal power, an elected parliament, or Majles, with wide powers to represent the people and a government with a cabinet subject to confirmation by the Majles. The shah signed the constitution on 30 December 1906, but refusing to forfeit all of his power to the Majles, attached a caveat that made his signature on all laws required for their enactment. He died five days later. The Supplementary Fundamental Laws approved in 1907 provided, within limits, for freedom of press, speech, and association, and for the security of life and property. The hopes for the constitutional rule were not realized, however.

Mozaffar al-Din Shah's son Mohammad Ali Shah (reigned 1907–1909), who, through his mother, was also the grandson of Prime-Minister Amir Kabir (see before), with the aid of Russia, attempted to rescind the constitution and abolish parliamentary government. After several disputes with the members of the Majles, in June 1908 he used his Russian-officered Persian Cossack Brigade (almost solely composed of Caucasian Muhajirs), to bomb the Majlis building, arrest many of the deputies (December 1907), and close down the assembly (June 1908).[89] Resistance to the shah, however, coalesced in Tabriz, Isfahan, Rasht, and elsewhere. In July 1909, constitutional forces marched from Rasht to Tehran led by Mohammad Vali Khan Khalatbari Tonekaboni, deposed the Shah, and re-established the constitution. The ex-shah went into exile in Russia. Shah died in San Remo, Italy, in April 1925. Every future Shah of Iran would also die in exile.

On 16 July 1909, the Majles voted to place Mohammad Ali Shah's 11-year-old son, Ahmad Shah on the throne.[90] Although the constitutional forces had triumphed, they faced serious difficulties. The upheavals of the Constitutional Revolution and civil war had undermined stability and trade. In addition, the ex-shah, with Russian support, attempted to regain his throne, landing troops in July 1910. Most serious of all, the hope that the Constitutional Revolution would inaugurate a new era of independence from the great powers ended when, under the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907, Britain and Russia agreed to divide Iran into spheres of influence. The Russians were to enjoy exclusive right to pursue their interests in the northern sphere, the British in the south and east; both powers would be free to compete for economic and political advantage in a neutral sphere in the center. Matters came to a head when Morgan Shuster, a United States administrator hired as treasurer-general by the Persian government to reform its finances, sought to collect taxes from powerful officials who were Russian protégés and to send members of the treasury gendarmerie, a tax department police force, into the Russian zone. In December 1911, the Majlis unanimously rejected a Russian ultimatum calling for the dismissal of Morgan Shuster, the American financial advisor to the government. Russian troops already stationed in Iran then advanced toward the capital. On 20 December, in order to avert a Russian occupation, Bakhtiari chiefs and their forces surrounded the Majlis building, compelled acceptance of the ultimatum, and dissolved the assembly, thereby suspending the constitution once again.[21][91]

British and Russian officials coordinated as the Russian army, still present in Iran, invaded the capital again and suspended the parliament. The Tsar ordered the troops in Tabriz "to act harshly and quickly", while purges were ordered, leading to many executions of prominent revolutionaries. The British Ambassador, George Head Barclay reported disapproval of this "reign of terror", though would soon pressure Persian ministers to officialize the Anglo-Russian partition of Iran. By June 1914, Russia established near-total control over its northern zone, while Britain had established influence over Baluch and Bakhtiari autonomous tribal leaders in the southeastern zone.[92] Qajar Iran would become a battleground between Russian, Ottoman, and British forces in the Persian campaign of World War I.[92]

World War I and related events

[edit]Though Qajar Iran had announced strict neutrality on the first day of November 1914 (which was reiterated by each successive government thereafter),[93] the neighboring Ottoman Empire invaded it relatively shortly after, in the same year. At that time, large parts of Iran were under tight Russian influence and control, and since 1910 Russian forces were present inside the country, while many of its cities possessed Russian garrisons.[93] Due to the latter reason, as Prof. Dr. Touraj Atabaki states, declaring neutrality was useless, especially as Iran had no force to implement this policy.[93]

At the beginning of the war, the Ottomans invaded Iranian Azerbaijan.[94] Numerous clashes would take place there between the Russians, who were further aided by the Assyrians under Agha Petros as well as Armenian volunteer units and battalions, and the Ottomans on the other side.[citation needed] However, with the advent of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent withdrawal of most of the Russian troops, the Ottomans gained the upper hand in Iran, occupying significant portions of the country until the end of the war. Between 1914 and 1918, the Ottoman troops massacred many thousands of Iran's Assyrian and Armenian population, as part of the Assyrian and Armenian genocides, respectively.[95][96]

The front in Iran would last up to the Armistice of Mudros in 1918.

Battle of Robat Karim

[edit]In late 1915, due to pro-CP actions by Iranian gendarmerie (encouraged by Ahmad Shah Qajar and the Majlis), Russian forces in northwest Iran marched toward Tehran. Russian occupation of Tehran would mean complete Russian control of Iran.[97]

Local irregular forces under Heydar Latifiyan blocked the Russian advance at Robat Karim.[98][97]

The Russian force won the Battle of Robat Karim on 27 December, and Heydar Latifiyan was killed, but the Russian advance was delayed, long enough for the Majlis to dissolve and the Shah and his court to escape to Qom. This preserved the independence of Iran.[97]

Fall of the dynasty

[edit]Ahmad Shah Qajar was born 21 January 1898 in Tabriz, and succeeded to the throne at age 11. However, the occupation of Persia during World War I by Russian, British, and Ottoman troops was a blow from which Ahmad Shah never effectively recovered.

In February 1921, Reza Khan, commander of the Persian Cossack Brigade, staged a coup d'état, becoming the effective ruler of Iran. In 1923, Ahmad Shah went into exile in Europe. Reza Khan induced the Majles to depose Ahmad Shah in October 1925 and to exclude the Qajar dynasty permanently. Reza Khan was subsequently proclaimed monarch as Reza Shah Pahlavi, reigning from 1925 to 1941.[99][100]

Ahmad Shah died on February 21, 1930, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France.[101]

Government and administration

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

Iran was divided into five large provinces and a large number of smaller ones at the beginning of Fath Ali Shah's reign, about 20 provinces in 1847, 39 in 1886, but 18 in 1906.[102] In 1868, most province governors were Qajar princes.[103]

Foreign influence and economic concessions

[edit]During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Qajar dynasty granted extensive concessions to foreign powers, particularly the British Empire and Russian Empire, in exchange for loans, technical expertise, or diplomatic support. The dire economic conditions of the Qajar government forced it to give preferential treatment to foreign powers and allow them to access profitable industries, such as the Iranian oil and tobacco industries.[104]

The Reuters Concession was the first major concession between foreign powers and the Qajar state. The concession was established between the Qajar state and British entrepreneur Baron Julius de Reuter.[105]

The oil concession, established between Nasr el-Din Shah and Englishman William Knox D'arcy allowed Britain to explore for oil in the southern part of Iran.[106]

These agreements eroded Iran's sovereignty and became a focal point of nationalist resistance, most notably during the Tobacco Protest (1891–1892) and the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911).[107]

Major concessions

[edit]| Concession | Year | Foreign entity | Terms | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reuter Concession | 1872 | 70-year monopoly over railways, mining, and banking. | Revoked in 1873 due to public backlash and Russian pressure; exposed Qajar financial desperation.[108] | |

| Tobacco Concession | 1890 | Monopoly over production, sale, and export of Iranian tobacco. | Sparked nationwide protests (1891–1892), leading to its cancellation; galvanized anti-imperialist movements.[109] | |

| D'Arcy Concession | 1901 | 60-year oil exploration rights in southwestern Iran. | Led to the discovery of oil in Masjed Soleyman (1908) and the founding of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), a precursor to BP.[110] | |

| Russian Fishing Concession | 1888–1921 | Control of Caspian Sea fisheries. | Devastated local fishing communities; revoked after the 1921 Persian coup d'état.[111] |

Political repercussions

[edit]

Foreign concessions intensified the Great Game rivalry between Britain and Russia, culminating in the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention, which partitioned Iran into:

- A **Russian sphere** in the north (including Tehran and Tabriz).

- A **British sphere** in the southeast (protecting approaches to British India).

- A neutral "buffer zone" in central Iran.[112]

The concessions also fueled the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911), as intellectuals and merchants demanded an end to Qajar corruption and foreign domination. The 1906 Constitution established the Majlis (parliament), which attempted to annul the D'Arcy oil concession in 1908 but was suppressed by Mohammad Ali Shah.[113]

Legacy

[edit]Historian Nikki Keddie argues:

The concessions symbolized Iran's subjugation to European imperialism. They left a legacy of distrust that shaped 20th-century Iranian nationalism, from Reza Shah's modernization campaigns to Mohammad Mosaddegh's oil nationalization.

— Keddie, Nikki, [114]

Military

[edit]| History of Iran |

|---|

|

|

Timeline |

The Qajar military was one of the dynasty's largest conventional sources of legitimacy, albeit was increasingly influenced by foreign powers over the course of the dynasty.[18][85]

Irregular forces, such as tribal cavalry, were a major element until the late nineteenth century, and irregular forces long remained a significant part of the Qajar army.[115]

At the time of Agha Mohammad Khan's death in 1797, his military was at its apex and counted 60,000 men, consisting of 50,000 tribal cavalry (savar) and 10,000 infantry (tofangchi) recruited from the sedentary population.[116] The army of his nephew and successor Fath-Ali Shah was much larger and from 1805 onwards incorporated European-trained units.[117] According to the French general Gardane, who was stationed in Iran, the army under Fath-Ali Shah numbered 180,000 men in 1808, thus far surpassing the army of Agha Mohammad Khan in size.[117] The modern historian Maziar Behrooz explains that there are other estimates which roughly match Gardane's estimate, however, Gardane was the first to complete a full outline of the Qajar army as he and his men were tasked with training the Qajar army.[117] According to Gardane's report of Fath-Ali Shah's contemporaneous army, some 144,000 were tribal cavalry, 40,000 were infantry (which included those trained on European lines), whilst 2,500 were part of the artillery units (which included the zamburakchis). Some half of the total amount of cavalrymen, that is 70,000–75,000, were so-called rekabi.[117] This meant that they received their salaries from the shah's personal funds during periods of supposed mobilization.[117] All others were so-called velayati, that is, they were paid for and were under the command of provincial Iranian rulers and governors. They were mobilized to join the royal army when the call required to do so.[117] Also, as was custom, tribes were supposed to provide troops for the army depending on their size. Thus, larger tribes were supposed to provide larger numbers, whilst smaller tribes provided smaller numbers.[117] After receiving payment, the central government expected military men to (for the greater part) to pay for their own supplies.[117]

During the era of wars with Russia, with crown prince Abbas Mirza's command of the army of the Azerbaijan Province, his segment of the army was the main force that defended Iran against the Russian invaders. Hence, the quality and organization of his units were superior to that of the rest of the Iranian army. Soldiers of Abbas Mirza's units were furnished from the villages of Azerbaijan and according to quotas in line with the rent each village was responsible for. Abbas Mirza provided for the payment of his troops' outfits and armaments. James Justinian Morier estimated the force under Abbas Mirza's command at 40,000 men, consisting of 22,000 cavalry, 12,000 infantry which included an artillery force, as well as 6,000 Nezam infantry.

Russia established the Persian Cossack Brigade in 1879, a force which was led by Russian officers and served as a vehicle for Russian influence in Iran.[19][118]

By the 1910s, the Qajar Iran was decentralised to the extent that foreign powers sought to bolster the central authority of the Qajars by providing military aid. It was viewed as a process of defensive modernisation; however, this also led to internal colonisation.[119]

The Iranian Gendarmerie was founded in 1911 with the assistance of Sweden.[120][119] The involvement of a neutral country was seen to avoid "Great Game" rivalry between Russia and Britain, as well as avoid siding with any particular alliance (in the prelude to World War I). Iranian administrators thought the reforms could strengthen the country against foreign influences. The Swedish-influenced police had some success in building up Persian police in centralizing the country.[120] After 1915, Russia and Britain demanded the recall of the Swedish advisers. Some Swedish officers left, while others sided with the Germans and Ottomans in their intervention in Persia. The remainder of the Gendarmerie was named amniya after a patrol unit that existed in the early Qajar dynasty.[120]

The number of Russian officers in the Cossack Brigade would increase over time. Britain also sent sepoys to reinforce the Brigade. After the start of the Russian Revolution, many tsarist supporters remained in Iran as members of the Cossack Brigade rather than fighting for or against the Soviet Union.[118]

The British formed the South Persia Rifles in 1916, which was initially separate from the Persian army until 1921.[121]

In 1921, the Russian-officered Persian Cossack Brigade was merged with the gendarmerie and other forces, and would become supported by the British.[122]

At the end of the Qajar dynasty in 1925, Reza Shah's Pahlavi army would include members of the gendarmerie, Cossacks, and former members of the South Persia Rifles.[118]

Art

[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

Demographics

[edit]In the late 18th century, during the final period of Shah Agha Mohammad Khan's reign, Iran (including the Khanates of the Caucasus) numbered some five to six million inhabitants.[123]

In 1800, three years into Fath-Ali Shah's reign, Iran numbered an estimated six million people.[124] A few years later, in 1812, the population numbered an estimated nine million. At the time, the country numbered some 70,000 Jews, 170,000 Armenian Christians, and 20,000 Zoroastrians.[124] The city of Shiraz in the south numbered circa 50,000, while Isfahan was the largest city at the time, with a population of about 200,000 inhabitants.[124] More to the north, Tehran, which became the capital of Iran under the Qajars in 1786 under Agha Mohammad Khan, resembled more-so a garrison rather than a town prior to becoming the capital.[124] At the time, as a developing city, it held some 40,000 to 50,000 inhabitants, but only when the Iranian royal court was in residence.[124] During summer, the royal court moved to a cooler area of pasture such as at Soltaniyeh, near Khamseh (i.e. Zanjan), or at Ujan near Tabriz in the Azerbaijan Province.[125] Other Tehrani residents moved to Shemiran in Tehran's north during summer, which was located at a higher altitude and thus had a more cool climate. These seasonal movements used to reduce Tehran's population to a few thousand seasonally.[125]

In Iran's east, in Mashhad, holding the Imam Reza Shrine and being Iran's former capital during the Afsharid era, held a population of less than 20,000 by 1800.[125] Tabriz, the largest city of the Azerbaijan Province, as well as the seat of the Qajar vali ahd ("crown prince"), used to be a prosperous city, but the 1780 earthquake had devastated the city and reversed its fortunes.[125] In 1809, the population of Tabriz was estimated at 50,000 including 200 Armenian families who lived in their own quarter.[125] The Azerbaijan province's total population, as per a 1806 estimate, was somewhere between 500,000 and 550,000 souls. The towns of Khoy and Marand, which at the time were no more than an amalgam of villages, were estimated to hold 25,000 and 10,000 inhabitants respectively.[125]

In Iran's domains in the Caucasus, the town of Nakhchivan (Nakhjavan) held a total population of some 5,000 in the year 1807, whereas the total population of the Erivan Khanate was some 100,000 in 1811.[125] However, the latter figure does not account for the Kurdish tribes that had migrated into the province. A Russian estimate asserted that the Pambak region of the northern part of the Erivan Khanate, which had been occupied by the Russians after 1804, held a total population of 2,832, consisting of 1,529 Muslims and 1,303 Christian Armenians.[125] According to the Russian demographic survey of 1823 of the Karabakh Khanate, its largest city, Shusha, held 371 households, who were divided in four quarters or parishes (mahaleh). The province itself consisted of 21 districts, in which nine large domains were located that belonged to Muslims and Armenians, 21 Armenian villages, ninety Muslim villages (both settled and nomadic), with Armenians constituting an estimated minority.[125] In the Ganja Khanate, the city of Ganja held 10,425 inhabitants in 1804 at the time of the Russian conquest and occupation.[125]

In 1868, Jews were the most significant minority in Tehran, numbering 1,578 people.[126] By 1884, this figure had risen to 5,571.[126]

See also

[edit]- Qajar (tribe)

- Qajar dynasty

- Selected Collection of Qajar Era Maps of Iran

- Russo-Iranian War 1804–1813

- Ottoman–Iranian War 1821–1823

- Russo-Iranian War 1826–1828

- Anglo-Iranian War 1856–1857

- Treaty of Paris 1857

- Treaty of Gulistan

- Treaty of Turkmanchay

- Iranian famine of 1870–1872

- Iranian famine of 1917–1919

- Amir Kabir

- Dar ul-Funun

- Constitutionalization attempts in Iran

- Iranian Constitutional Revolution

- 1st Iranian Majlis

- Morteza Gholi Khan Hedayat (1st Speaker of the Majlis of Iran)

- Mirza Nasrullah Khan (1st Prime Minister of Iran)

- Iranian Constitution of 1906

- Treaty of Saint Petersburg 1907

- 1908 bombardment of the Majlis

- Minor Tyranny

- Occupation of Iran In World War I

- British occupation of Bushehr

- Iranian coup d'état 1921

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Homa Katouzian, State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis, published by I. B. Tauris, 2006. pg 327: "In post-Islamic times, the mother-tongue of Iran's rulers was often Turkic, but Persian was almost invariably the cultural and administrative language."

- ^ Katouzian 2007, p. 128.

- ^ "Ardabil Becomes a Province: Center-Periphery Relations in Iran", H. E. Chehabi, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2 (May, 1997), 235; "Azeri Turkish was widely spoken at the two courts in addition to Persian, and Mozaffareddin Shah (r. 1896–1907) spoke Persian with an Azeri Turkish accent."

- ^ Javadi & Burrill 1988, pp. 251–255.

- ^ Donzel, Emeri "van" (1994). Islamic Desk Reference. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09738-4. p. 285-286

- ^ Hughes, William (1873). A Class-book of Modern Geography: With Examination Questions. G. Philip & Son. p. 175. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

In size it is about 500,000 square miles

- ^ علیاصغر شمیم، ایران در دوره سلطنت قاجار، تهران: انتشارات علمی، ۱۳۷۱، ص ۲۸۷

- ^ a b c Amanat 1997, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c d Cyrus Ghani. Iran and the Rise of the Reza Shah: From Qajar Collapse to Pahlavi Power, I. B. Tauris, 2000, ISBN 1-86064-629-8, p. 1

- ^ William Bayne Fisher. Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 344, ISBN 0-521-20094-6

- ^ Dr Parviz Kambin, A History of the Iranian Plateau: Rise and Fall of an Empire, Universe, 2011, p.36, online edition.

- ^ Choueiri, Youssef M., A companion to the history of the Middle East, (Blackwell Ltd., 2005), 231,516.

- ^ H. Scheel; Jaschke, Gerhard; H. Braun; Spuler, Bertold; T. Koszinowski; Bagley, Frank (1981). Muslim World. Brill Archive. pp. 65, 370. ISBN 978-90-04-06196-5. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ a b c Michael Axworthy. Iran: Empire of the Mind: A History from Zoroaster to the Present Day, Penguin UK, 6 November 2008. ISBN 0-14-190341-4

- ^ a b c d e Fisher et al. 1991, p. 330.

- ^ a b c d Timothy C. Dowling. Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond, pp 728–730 ABC-CLIO, 2 December 2014 ISBN 1-59884-948-4

- ^ Amanat 2017, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d e f g Deutschmann, Moritz (2013). ""All Rulers are Brothers": Russian Relations with the Iranian Monarchy in the Nineteenth Century". Iranian Studies. 46 (3): 401–413. doi:10.1080/00210862.2012.759334. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 24482848. S2CID 143785614.

- ^ a b c d Andreeva, Elena (2007). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and Orientalism. London: Routledge. pp. 20, 63–76. ISBN 978-0-203-96220-6. OCLC 166422396.

- ^ "ANGLO-RUSSIAN CONVENTION OF 1907". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ a b Afary, Janet (1996). The Iranian Constitutional Revolution, 1906–1911: Grassroots Democracy, Social Democracy, & the Origins of Feminism. Columbia University Press. pp. 330–338. ISBN 978-0-231-10351-0.

- ^ Amanat 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Amanat 2017, p. 443.

- ^ Amanat 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Amanat 2019, p. 33.

- ^ Ashraf 2024, p. 82.

- ^ Hambly 1991, p. 104.

- ^ Hambly 1991, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b Hambly 1991, p. 105.

- ^ Hambly 1991, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Amanat 2017, p. 43.

- ^ Hambly 1991, p. 106.

- ^ K. M. Röhrborn. Provinzen und Zentralgewalt Persiens im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, Berlin, 1966, p. 4

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica. Ganja. Online Edition

- ^ Keddie, Nikki R. (1971). "The Iranian Power Structure and Social Change 1800–1969: An Overview". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 2 (1): 3–20 [p. 4]. doi:10.1017/S0020743800000842. S2CID 163247729.

- ^ Irons, William (1975). The Yomut Turkmen: A Study of Social Organization among a Central Asian Turkic-Speaking Population. University of Michigan Press. p. 8.

For example, the Turkmen of Iran were instrumental in the establishment of Kajar dynasty in Iran in the late eighteenth century, and opponents of the Iranian constitution sought Turkmen support in the revolution of 1909.

- ^ Lapidus, Ira Marvin (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 469. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- ^ Suny 1994, p. 55.

- ^ Hitchins 1998, pp. 541–542.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fisher et al. 1991, p. 328.

- ^ Perry 1991, p. 96.

- ^ a b Fisher et al. 1991, p. 327.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2011, p. 327.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze 2011, p. 409.

- ^ a b c d Donald Rayfield. Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia Reaktion Books, 15 February. 2013 ISBN 1-78023-070-2 p 255

- ^ a b c Lang, David Marshall (1962), A Modern History of Georgia, p. 38. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- ^ a b Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation, p. 59. Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-20915-3

- ^ P.Sykes, A history of Persia, 3rd edition, Barnes and Noble 1969, Vol. 2, p. 293

- ^ Malcolm, Sir John (1829), The History of Persia from the Earliest Period to the Present Time, pp. 189–191. London: John Murray.

- ^ Fisher, William Bayne (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge University Press. pp. 128–129.

(...) Agha Muhammad Khan remained nine days in the vicinity of Tiflis. His victory proclaimed the restoration of Iranian military power in the region formerly under Safavid domination.

- ^ a b c Fisher et al. 1991, p. 329.

- ^ Alekseĭ I. Miller. Imperial Rule Central European University Press, 2004 ISBN 963-9241-98-9 p 204

- ^ Gvosdev (2000), p. 86

- ^ Lang (1957), p. 249

- ^ Dowling 2014, p. 728.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 1035. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

January 1804. (...) Russo-Persian War. The Russian invasion of Persia. (...) In January 1804 Russian forces under General Paul Tsitsianov (Sisianoff) invade Persia and storm the citadel of Ganjeh, beginning the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813).

- ^ Hambly 1991a, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Behrooz 2013a, p. 63.

- ^ Dowling, Timothy C., ed. (2015). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 729. ISBN 978-1-59884-948-6.

In May 1826, Russia, therefore, occupied Mirak, in the Erivan khanate, in violation of the Treaty of Gulistan.

- ^ Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press. pp. 69, 133. ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3.

- ^ L. Batalden, Sandra (1997). The newly independent states of Eurasia: Handbook of former Soviet republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-89774-940-4.

- ^ Ebel, Robert E.; Menon, Rajan, eds. (2000). Energy and conflict in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7425-0063-1.

- ^ Andreeva, Elena (2010). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and orientalism (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-415-78153-4.

- ^ Kemal Çiçek; Ercüment Kuran (2000). The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation. University of Michigan. ISBN 978-975-6782-18-7.

- ^ Karl Ernest Meyer; Shareen Blair Brysac (2006). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-465-04576-1.

- ^ Michael P. Croissant, "The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict: causes and implications", Praeger/Greenwood,1998 – Page 67: The historical homeland of the Talysh was divided between Russia and Iran in 1813.

- ^ a b "Caucasus Survey". Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Mansoori, Firooz (2008). "17". Studies in History, Language and Culture of Azerbaijan (in Persian). Tehran: Hazar-e Kerman. p. 245. ISBN 978-600-90271-1-8.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 336.

- ^ А. Г. Булатова. Лакцы (XIX – нач. XX вв.). Историко-этнографические очерки. — Махачкала, 2000.

- ^ a b "The Iranian Armed Forces in Politics, Revolution and War: Part One". 22 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Griboedov not only extended protection to those Caucasian captives who sought to go home but actively promoted the return of even those who did not volunteer. Large numbers of Georgian and Armenian captives had lived in Iran since 1804 or as far back as 1795." Fisher, William Bayne;Avery, Peter; Gershevitch, Ilya; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles. The Cambridge History of Iran Cambridge University Press, 1991. p. 339.

- ^ (in Russian) A. S. Griboyedov. "Записка о переселеніи армянъ изъ Персіи въ наши области" Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Фундаментальная Электронная Библиотека

- ^ a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 11, 13–14.

- ^ Arakel of Tabriz. The Books of Histories; chapter 4. Quote: "[The Shah] deep inside understood that he would be unable to resist Sinan Pasha, i.e. the Sardar of Jalaloghlu, in a[n open] battle. Therefore he ordered to relocate the whole population of Armenia – Christians, Jews, and Muslims alike, to Persia, so that the Ottomans find the country depopulated."

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, p. 14.

- ^ Azizi, Mohammad-Hossein. "The historical backgrounds of the Ministry of Health foundation in Iran." Arch Iran Med 10.1 (2007): 119–23.

- ^ Adle, Chahryar (2005). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Towards the contemporary period: from the mid-nineteenth to the end of the twentieth century. UNESCO. pp. 470–477. ISBN 978-92-3-103985-0.

- ^ Algar, Hamid (1989). "AMĪR KABĪR, MĪRZĀ TAQĪ KHAN". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ a b "DĀR AL-FONŪN". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ Mojtahed-Zadeh, Pirouz (31 July 2004). The Small Players of the Great Game: The Settlement of Iran's Eastern Borderlands and the Creation of Afghanistan. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-38378-8.

- ^ a b Rabi, Uzi; Ter-Oganov, Nugzar (2009). "The Russian Military Mission and the Birth of the Persian Cossack Brigade: 1879–1894". Iranian Studies. 42 (3): 445–463. doi:10.1080/00210860902907396. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 25597565. S2CID 143812599.

- ^ Andreeva, Elena. "RUSSIA v. RUSSIANS AT THE COURT OF MOḤAMMAD-ʿALI SHAH". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "INDO-EUROPEAN TELEGRAPH DEPARTMENT". ENCYCLOPEDIA IRANICA. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ a b Amanat 1997, p. 440.

- ^ Kohn 2006, p. 408.

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 597.

- ^ Meyer, Karl E. (10 August 1987). "Opinion | The Editorial Notebook; Persia: The Great Game Goes On". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ a b Afary, Janet (1996). The Iranian Constitutional Revolution, 1906–1911: Grassroots Democracy, Social Democracy, & the Origins of Feminism. Columbia University Press. pp. 330–338. ISBN 978-0-231-10351-0.

- ^ a b c Atabaki 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Atabaki 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Üngör 2016, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Bahar, Mohammad Taghi (1992). A brief history of political parties in Iran: the extinction of the Qajar dynasty. J. First. Amir Kabir Publications. ISBN 978-964-00-0596-5

- ^ "جنگهای جهانی". مورخ (in Persian). Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Abrahamian, History of Modern Iran, (2008), p.91

- ^ Roger Homan, "The Origins of the Iranian Revolution," International Affairs 56/4 (Autumn 1980): 673–7.

- ^ "Portraits and Pictures of Soltan Ahmad Shah Qajar (Kadjar)". qajarpages.org. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Willem M. Floor, A Fiscal History of Iran in the Safavid and Qajar Periods, 1500–1925.

- ^ Frederick van Millingen, La Turquie sous le règne d'Abdul-Aziz.

- ^ Anderson, Betty S. (2016). A history of the modern Middle East: rulers, rebels, and rogues. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780804783248.

- ^ Khater, Akram Fouad (2004). Sources in the history of the modern Middle East. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin. p. 35. ISBN 9780395980675.

- ^ Anderson, Betty S. (2016). A history of the modern Middle East: rulers, rebels, and rogues. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780804783248.

- ^ Abrahamian 2008, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Keddie 1999, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Afary 1991, pp. 657–674.

- ^ Ferrier 1982, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1968, pp. 210–215.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1968, p. 328.

- ^ Abrahamian 2008, pp. 50–53.

- ^ Keddie 1999, p. 62.

- ^ Rabi, Uzi; Ter-Oganov, Nugzar (2012). "The Military of Qajar Iran: The Features of an Irregular Army from the Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Century". Iranian Studies. 45 (3): 333–354. doi:10.1080/00210862.2011.637776. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 41445213. S2CID 159730844.

- ^ Behrooz 2023, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Behrooz 2023, p. 47.

- ^ a b c "Cossack Brigade". Iranica Online. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ a b "The Swedish-led Gendarmerie in Persia 1911–1916 State Building and Internal Colonization". Sharmin and Bijan Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "SWEDEN ii. SWEDISH OFFICERS IN PERSIA, 1911–15". Iranica Online. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "South Persia Rifles". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Zirinsky, Michael P. (1992). "Imperial Power and Dictatorship: Britain and the Rise of Reza Shah, 1921–1926". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 24 (4): 639–663. doi:10.1017/S0020743800022388. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 164440. S2CID 159878744.

- ^ Behrooz 2023, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e Behrooz 2023, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Behrooz 2023, p. 39.

- ^ a b Sohrabi, Narciss M. (2023). "The politics of in/visibility: The Jews of urban Tehran". Studies in Religion. 53: 4. doi:10.1177/00084298231152642. S2CID 257370493.

Sources

[edit]- Atabaki, Touraj (2006). Iran and the First World War: Battleground of the Great Powers. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-964-6.

- Amanat, Abbas (1997). Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-097-1.

- Amanat, Abbas (2017). Iran: A Modern History. Yale University Press. pp. 1–992. ISBN 978-0-300-11254-2.

- Amanat, Abbas (2019). "Remembering the Persianate". In Amanat, Abbas; Ashraf, Assef (eds.). The Persianate World: Rethinking a Shared Sphere. Brill. pp. 15–62. ISBN 978-90-04-38728-7.

- Ashraf, Assef (2024). Making and Remaking Empire in Early Qajar Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-36155-2.

- Behrooz, Maziar (2013a). "From confidence to apprehension: early Iranian interaction with Russia". In Cronin, Stephanie (ed.). Iranian-Russian Encounters: Empires and Revolutions Since 1800. Routledge. pp. 49–68. ISBN 978-0-415-62433-6.

- Behrooz, Maziar (2023). Iran at War: Interactions with the Modern World and the Struggle with Imperial Russia. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-7556-3737-9.

- Bournoutian, George (1980). The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826–1832. The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies.

- Bosworth, Edmund (1983). Hillenbrand, Carole (ed.). Qajar Iran: Political, Social, and Cultural Change, 1800–1925. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-085-224-459-3.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2002). A Concise History of the Armenian People: (from Ancient Times to the Present) (2 ed.). Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56859-141-4.

- Caton, M. (1988). "BANĀN, ḠOLĀM-ḤOSAYN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Dowling, Timothy C. (2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-948-6.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20095-0.

- Floor, Willem M. (2003). Traditional Crafts in Qajar Iran (1800–1925). Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-156-859-147-6.

- Gleave, Robert, ed. (2005). Religion and Society in Qajar Iran. Routledge. ISBN 978-041-533-814-1.

- Hambly, Gavin R. G. (1991). "Āghā Muhammad Khān and the establishment of the Qājār dynasty". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin R. G.; Melville, Charles Peter (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 104–143. ISBN 0-521-20095-4.

- Hambly, Gavin R. G. (1991a). "Iran during the reigns of Fath 'Alī Shāh and Muhammad Shāh". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin R. G.; Melville, Charles Peter (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–173. ISBN 0-521-20095-4.

- Hitchins, Keith (1998). "EREKLE II". EREKLE II – Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5. pp. 541–542.

- Holt, P.M.; Lambton, Ann K.S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29136-1.

- Javadi, H.; Burrill, K. (1988). "Azerbaijan x. Azeri Turkish Literature". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III/3: Azerbaijan IV–Bačča(-ye) Saqqā. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 251–255. ISBN 978-0-71009-115-4.

- Katouzian, Homa (2007). Iranian History and Politics: The Dialectic of State and Society. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-29754-7.

- Keddie, Nikki R. (1999). Qajar Iran and the rise of Reza Khan, 1796–1925. Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-156-859-084-4.

- Kettenhofen, Erich; Bournoutian, George A.; Hewsen, Robert H. (1998). "EREVAN". Encyclopǣdia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5. pp. 542–551.

- Kohn, George C. (2006). Dictionary of Wars. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-2916-7.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-336-1.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-4146-6.

- Gvosdev, Nikolas K.: Imperial policies and perspectives towards Georgia: 1760–1819, Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, ISBN 0-312-22990-9

- Lang, David M.: The last years of the Georgian Monarchy: 1658–1832, Columbia University Press, New York 1957

- Paidar, Parvin (1997). Women and the Political Process in Twentieth-Century Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59572-8.

- Perry, John (1991). "The Zand dynasty". The Cambridge History of Iran Volume=7: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 63–104. ISBN 978-0-521-20095-0.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20915-3.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015). "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2016). "The Armenian Genocide in the Context of 20th-Century Paramilitarism". The Armenian Genocide Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-56163-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Abrahamian, Ervand (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52891-7.

- Afary, Janet (1991). "The Tobacco Protest of 1891–1892 in Iran". Middle Eastern Studies. 27 (4): 657–674. doi:10.1080/00263209108700885.

- Ferrier, Ronald (1982). The History of the British Petroleum Company. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24647-7.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1968). Russia and Britain in Persia, 1864–1914. Yale University Press.

- Behrooz, Maziar (2013b). "Revisiting the Second Russo-Iranian War (1826–28): Causes and Perceptions". Iranian Studies. 46 (3): 359–381. doi:10.1080/00210862.2012.758502. S2CID 143736977.

- Bournoutian, George (2020). From the Kur to the Aras: A Military History of Russia's Move into the South Caucasus and the First Russo-Iranian War, 1801–1813. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-44516-1.

- Deutschmann, Moritz (2013). ""All Rulers are Brothers": Russian Relations with the Iranian Monarchy in the Nineteenth Century". Iranian Studies. 46 (3): 383–413. doi:10.1080/00210862.2012.759334. S2CID 143785614.

- Grobien, Philip Henning (2021). "Iran and imperial nationalism in 1919". Middle Eastern Studies. 57 (2): 292–309. doi:10.1080/00263206.2020.1853535. S2CID 230604129.

- Sluglett, Peter (2014). "The Waning of Empires: The British, the Ottomans and the Russians in the Caucasus and North Iran, 1917–1921". Middle East Critique. 23 (2): 189–208. doi:10.1080/19436149.2014.905084. S2CID 143816605.

External links

[edit]Qajar Iran

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Name and Tribal Origins

The Qajar dynasty takes its name from the Qajar tribe, a Turkic-speaking clan originating among the Oghuz Turks, whose westward migrations from Central Asia brought them to the Caucasus and Iranian plateau by the 11th century alongside Seljuk forces.[8] The term "Qajar" itself derives from the Turkic root qacar or kaçar, evoking notions of a fugitive or resilient nomadic warrior lifestyle suited to the tribe's pastoralist and martial traditions.[9] Early records of the tribe appear in the 14th century, placing them in northern Azerbaijan as one of several Oghuz subgroups that formed semi-autonomous encampments (uymaq) amid the region's Turkic polities.[9] During the 15th century, the Qajars integrated into the Aq Qoyunlu confederation's tribal network in eastern Anatolia and western Iran, where they contributed cavalry forces and adopted Twelver Shiism under the confederation's influence, aligning with the emerging Persianate religious order that would define subsequent dynasties.[10] This period marked their transition from peripheral nomads to embedded actors in the Irano-Turkic political sphere, retaining tribal endogamy and Turkic dialects while engaging in feuds and alliances typical of Oghuz confederative structures.[8] Under the Safavids (1501–1736), the Qajars functioned as a loyal uymaq, supplying irregular tribal levies for campaigns rather than serving as manumitted ghulams, which preserved their confederative autonomy and facilitated internal promotions based on kinship and valor.[11] Over time, exposure to Persian bureaucracy and Shiite orthodoxy prompted a cultural synthesis, with Qajar elites adopting Perso-Islamic titulature and administrative norms, yet their core identity remained anchored in Turkic tribal loyalties that emphasized multi-ethnic coalition-building over ethnic Persian homogeneity.[8] This hybrid foundation enabled the dynasty's later rise through leveraging nomadic mobility and confederative alliances in a fragmented post-Safavid landscape.[11]Historical Rise

Post-Safavid Fragmentation

The fall of the Safavid dynasty commenced in 1722 when Afghan Hotaki forces, led by Mahmud, defeated Safavid armies at the Battle of Gulnabad on March 8 and subsequently sacked Isfahan, compelling Shah Sultan Husayn to abdicate.[12] This invasion exploited Safavid internal weaknesses, including weakened military cohesion and administrative decay, rather than overwhelming external superiority, as the Afghans numbered fewer than 20,000 against Safavid forces exceeding 40,000.[12] The Hotaki interlude lasted until 1729–1730, when Nader Qoli, an Afshar chieftain from Khorasan, expelled the Afghans, reinstalled a Safavid puppet, and by 1736 deposed the last Safavid claimant to proclaim himself shah, founding the Afsharid dynasty.[13] Nader Shah's rule (1736–1747) achieved transient reunification through relentless campaigns, incorporating tribal levies and restoring some territorial integrity, but his assassination by disaffected officers on June 20, 1747, triggered immediate fragmentation as his empire splintered into autonomous domains under rival generals and local potentates.[13] In the ensuing vacuum, the Zand tribe under Karim Khan consolidated control over southern and central Iran from 1751 to his death in 1779, establishing Shiraz as a stable administrative center and fostering limited economic recovery in those regions through pragmatic governance and avoidance of overexpansion.[14] However, northern and eastern Iran devolved into a mosaic of tribal fiefdoms, where Turkmen confederations—including Afshars, Qajars, and Jalayirs—waged endemic conflicts for supremacy, with no single authority dominating beyond local alliances.[4] The Qajars, a Turkmen clan of Oghuz origin numbering around 10,000 nomads, operated principally in northern Iran, leveraging mobility and kinship ties to contest territories against fellow Turkmen groups amid this decentralized strife.[4] Political instability precipitated economic contraction, as incessant warfare undermined agricultural output and caravan security, reducing trade volumes—once reliant on overland routes—to a fraction of prior levels and contributing to fiscal collapse.[15] Widespread anarchy fostered banditry and rural depopulation, with scholarly estimates placing Iran's population at approximately 9 million in the early 1700s, declining to about 6 million by century's end due to combat losses, famine, and emigration.[16] These internal dynamics, rooted in fragmented loyalties and eroded institutions, formed the primary catalysts for the era's disorder, priming the terrain for eventual centralizing efforts without predominant attribution to foreign incursions.[13]Agha Mohammad Khan's Unification Campaigns

Agha Mohammad Khan, chief of the Qoyunlu branch of the Turkic Qajar tribe and a eunuch castrated in childhood during captivity under the Afsharids, initiated unification campaigns in the late 1780s following the fragmentation after the Zand dynasty's internal strife. Having escaped Shiraz in 1779, he consolidated control in northern Iran, defeating rival Qajar factions and assassinating his brother Ja'far-qoli Khan to unify tribal loyalties through coercion rather than consensus. By 1786, he captured Tehran from Zand control, designating it his primary base and repairing its fortifications, which facilitated central authority amid decentralized khanates.[17][18][18] His campaigns targeted Zand remnants systematically: in the 1780s, he repeatedly defeated Ja'far Khan Zand, capturing Shiraz in 1792, demolishing its walls, and deporting 12,000 families to Astarabad and Mazandaran to prevent resurgence. The decisive blow came in 1794 with the siege of Kerman, where forces under Agha Mohammad Khan overcame Lotf-Ali Khan Zand after betrayal; the city fell after prolonged resistance, followed by mass enslavement of approximately 20,000 women and children distributed to troops, and the gouging out of eyes from all surviving adult males as a deterrent to rebellion, with Lotf-Ali Khan tortured and executed. These acts, exemplifying calculated brutality to enforce submission, eliminated the Zand dynasty and reasserted Persian sovereignty over southern and central territories fragmented since the Safavids.[18][17][19] In March 1796, after these internal victories, Agha Mohammad Khan was crowned shahanshah at the Mughan steppe, blending Qajar khanate traditions with imperial Persian legitimacy symbolized by girding the Safavid sword at Ardabil, though he named nephew Baba Khan (later Fath-Ali Shah) as heir due to his castration precluding direct succession. To secure flanks, he suppressed external rivals claiming Persian lands: in 1795-1796, he led 60,000 troops to sack Tbilisi, massacring the elderly, infirm, and clergy while enslaving 15,000, reincorporating Georgia as a vassal; he also conquered Khorasan, torturing and killing the blind Afsharid ruler Shah Rokh to dismantle Afghan-influenced holdouts. These coercive tribal alliances and punitive expeditions unified Iran proper by 1797, restoring centralized monarchy through raw power rather than ideological or administrative reform.[18][17][20][18]Reign of Early Shahs

Fath-Ali Shah's Expansion Attempts