Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Raised beach

View on Wikipedia

A raised beach, coastal terrace,[1] or perched coastline is a relatively flat, horizontal or gently inclined surface of marine origin,[2] mostly an old abrasion platform which has been lifted out of the sphere of wave activity (sometimes called "tread"). Thus, it lies above or under the current sea level, depending on the time of its formation.[3][4] It is bounded by a steeper ascending slope on the landward side and a steeper descending slope on the seaward side[2] (sometimes called "riser"). Due to its generally flat shape, it is often used for anthropogenic structures such as settlements and infrastructure.[3]

A raised beach is an emergent coastal landform. Raised beaches and marine terraces are beaches or wave-cut platforms raised above the shoreline by a relative fall in the sea level.[5]

Around the world, a combination of tectonic coastal uplift and Quaternary sea-level fluctuations has resulted in the formation of marine terrace sequences, most of which were formed during separate interglacial highstands that can be correlated to marine isotope stages (MIS).[6]

A marine terrace commonly retains a shoreline angle or inner edge, the slope inflection between the marine abrasion platform and the associated paleo sea cliff. The shoreline angle represents the maximum shoreline of a transgression and therefore a paleo-sea level.

Morphology

[edit]

The platform of a marine terrace usually has a gradient between 1°–5° depending on the former tidal range with, commonly, a linear to concave profile. The width is quite variable, reaching up to 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), and seems to differ between the northern and southern hemispheres.[9] The cliff faces that delimit the platform can vary in steepness depending on the relative roles of marine and subaerial processes.[10] At the intersection of the former shore (wave-cut/abrasion-) platform and the rising cliff face the platform commonly retains a shoreline angle or inner edge (notch) that indicates the location of the shoreline at the time of maximum sea ingression and therefore a paleo-sea level.[11] Sub-horizontal platforms usually terminate in a low-tide cliff, and it is believed that the occurrence of these platforms depends on the tidal activity.[10] Marine terraces can extend for several tens of kilometers parallel to the coast.[3]

Older terraces are covered by marine and/or alluvial or colluvial materials while the uppermost terrace levels usually are less well preserved.[12] While marine terraces in areas of relatively rapid uplift rates (> 1 mm/year) can often be correlated to individual interglacial periods or stages, those in areas of slower uplift rates may have a polycyclic origin with stages of returning sea levels following periods of exposure to weathering.[2]

Marine terraces can be covered by a wide variety of soils with complex histories and different ages. In protected areas, allochthonous sandy parent materials from tsunami deposits may be found. Common soil types found on marine terraces include planosols and solonetz.[13]

Formation

[edit]It is now widely thought that marine terraces are formed during the separated high stands of interglacial stages correlated to marine isotope stages (MIS).[14][15][16][17][18]

Causes

[edit]

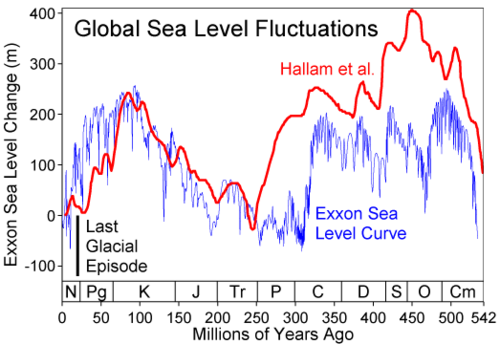

The formation of marine terraces is controlled by changes in environmental conditions and by tectonic activity during recent geological times. Changes in climatic conditions have led to eustatic sea-level oscillations and isostatic movements of the Earth's crust, especially with the changes between glacial and interglacial periods.

Processes of eustasy lead to glacioeustatic sea level fluctuations due to changes in the water volume in the oceans, and hence to regressions and transgressions of the shoreline. At times of maximum glacial extent during the last glacial period, the sea level was about 100 metres (330 ft) lower compared to today. Eustatic sea level changes can also be caused by changes in the void volume of the oceans, either through sedimento-eustasy or tectono-eustasy.[19]

Processes of isostasy involve the uplift of continental crusts along with their shorelines. Today, the process of glacial isostatic adjustment mainly applies to Pleistocene glaciated areas.[19] In Scandinavia, for instance, the present rate of uplift reaches up to 10 millimetres (0.39 in)/year.[20]

In general, eustatic marine terraces were formed during separate sea-level highstands of interglacial stages[19][21] and can be correlated to marine oxygen isotopic stages (MIS).[22][23] Glacioisostatic marine terraces were mainly created during stillstands of the isostatic uplift.[19] When eustasy was the main factor for the formation of marine terraces, derived sea level fluctuations can indicate former climate changes. This conclusion has to be treated with care, as isostatic adjustments and tectonic activities can be extensively overcompensated by an eustatic sea level rise. Thus, in areas of both eustatic and isostatic or tectonic influences, the course of the relative sea level curve can be complicated.[24] Hence, most of today's marine terrace sequences were formed by a combination of tectonic coastal uplift and Quaternary sea level fluctuations.

Jerky tectonic uplifts can also lead to marked terrace steps while smooth relative sea level changes may not result in obvious terraces, and their formations are often not referred to as marine terraces.[11]

Processes

[edit]Marine terraces often result from marine erosion along rocky coastlines[2] in temperate regions due to wave attacks and sediment carried in the waves. Erosion also takes place in connection with weathering and cavitation. The speed of erosion is highly dependent on the shoreline material (hardness of rock[10]), the bathymetry, and the bedrock properties and can be between only a few millimeters per year for granitic rocks and more than 10 metres (33 ft) per year for volcanic ejecta.[10][25] The retreat of the sea cliff generates a shore (wave-cut/abrasion-) platform through the process of abrasion. A relative change in the sea level leads to regressions or transgressions and eventually forms another terrace (marine-cut terrace) at a different altitude, while notches in the cliff face indicate short stillstands.[25]

It is believed that the terrace gradient increases with tidal range and decreases with rock resistance. In addition, the relationship between terrace width and the strength of the rock is inverse, and higher rates of uplift and subsidence as well as a higher slope of the hinterland increase the number of terraces formed during a certain time.[26]

Furthermore, shore platforms are formed by denudation and marine-built terraces arise from accumulations of materials removed by shore erosion.[2] Thus, a marine terrace can be formed by both erosion and accumulation. However, there is an ongoing debate about the roles of wave erosion and weathering in the formation of shore platforms.[10]

Reef flats or uplifted coral reefs are another kind of marine terrace found in intertropical regions. They are a result of biological activity, shoreline advance and accumulation of reef materials.[2]

While a terrace sequence can date back hundreds of thousands of years, its degradation is a rather fast process. A deeper transgression of cliffs into the shoreline may destroy previous terraces; but older terraces might be decayed[25] or covered by deposits, colluvia or alluvial fans.[3] Erosion and backwearing of slopes caused by incisive streams play another important role in this degradation process.[25]

Land and sea level history

[edit]The total displacement of the shoreline relative to the age of the associated interglacial stage allows the calculation of a mean uplift rate or the calculation of eustatic level at a particular time if the uplift is known.

To estimate vertical uplift, the eustatic position of the considered paleo sea levels relative to the present one must be known as precisely as possible. Current chronology relies principally on relative dating based on geomorphologic criteria, but in all cases, the shoreline angle of the marine terraces is associated with numerical ages. The best-represented terrace worldwide is the one correlated to the last interglacial maximum (MIS 5e).[27][28][29] The age of MISS 5e is arbitrarily fixed to range from 130 to 116 ka[30] but is demonstrated to range from 134 to 113 ka in Hawaii and Barbados with a peak from 128 to 116 ka on tectonically stable coastlines. Older marine terraces well represented in worldwide sequences are those related to MIS 9 (~303–339 ka) and 11 (~362–423 ka).[31] Compilations show that sea level was 3 ± 3 meters higher during MIS 5e, MIS 9 and 11 than during the present one and −1 ± 1 m to the present one during MIS 7.[32][33] Consequently, MIS 7 (~180-240 ka) marine terraces are less pronounced and sometimes absent. When the elevations of these terraces are higher than the uncertainties in paleo-eustatic sea level mentioned for the Holocene and Late Pleistocene, these uncertainties don't affect on overall interpretation.

The sequence can also occur where the accumulation of ice sheets has depressed the land so that when the ice sheets melt the land readjusts with time thus raising the height of the beaches (glacial-isostatic rebound) and in places where co-seismic uplift occurs. In the latter case, the terrace is not correlated with sea-level highstands even if co-seismic terraces are known only for the Holocene.

Mapping and surveying

[edit]

For exact interpretations of the morphology, extensive datings, surveying and mapping of marine terraces are applied. This includes stereoscopic aerial photographic interpretation (ca. 1 : 10,000 – 25,000[11]), on-site inspections with topographic maps (ca. 1 : 10,000) and analysis of eroded and accumulated material. Moreover, the exact altitude can be determined with an aneroid barometer or preferably with a levelling instrument mounted on a tripod. It should be measured with an accuracy of 1 cm (0.39 in) and at about every 50–100 metres (160–330 ft), depending on the topography. In remote areas, the techniques of photogrammetry and tacheometry can be applied.[24]

Correlation and dating

[edit]Different methods for dating and correlation of marine terraces can be used and combined.

Correlational dating

[edit]The morphostratigraphic approach focuses especially in regions of marine regression on the altitude as the most important criterion to distinguish coastlines of different ages. Moreover, individual marine terraces can be correlated based on their size and continuity. Also, paleo-soils as well as glacial, fluvial, eolian and periglacial landforms and sediments may be used to find correlations between terraces.[24] On New Zealand's North Island, for instance, tephra and loess were used to date and correlate marine terraces.[34] At the terminus advance of former glaciers marine terraces can be correlated by their size, as their width decreases with age due to the slowly thawing glaciers along the coastline.[24]

The lithostratigraphic approach uses typical sequences of sediment and rock strata to prove sea-level fluctuations based on an alternation of terrestrial and marine sediments or littoral and shallow marine sediments. Those strata show typical layers of transgressive and regressive patterns.[24] However, an unconformity in the sediment sequence might make this analysis difficult.[35]

The biostratigraphic approach uses remains of organisms which can indicate the age of a marine terrace. For that, often mollusc shells, foraminifera or pollen are used. Especially Mollusca can show specific properties depending on their depth of sedimentation. Thus, they can be used to estimate former water depths.[24]

Marine terraces are often correlated to marine oxygen isotopic stages (MIS)[22] and can also be roughly dated using their stratigraphic position.[24]

Direct dating

[edit]There are various methods for the direct dating of marine terraces and their related materials. The most common method is 14C radiocarbon dating,[36] which has been used, for example, on the North Island of New Zealand to date several marine terraces.[37] It utilizes terrestrial biogenic materials in coastal sediments, such as mollusc shells, by analyzing the 14C isotope.[24] In some cases, however, dating based on the 230Th/234U ratio was applied, in case detrital contamination or low uranium concentrations made finding a high-resolution dating difficult.[38] In a study in southern Italy, paleomagnetism was used to carry out paleomagnetic datings[39] and luminescence dating (OSL) was used in different studies on the San Andreas Fault[40] and on the Quaternary Eupcheon Fault in South Korea.[41] In the last decade, the dating of marine terraces has been enhanced since the arrival of the terrestrial cosmogenic nuclides method, particularly through the use of 10Be and 26Al cosmogenic isotopes produced on site.[42][43][44] These isotopes record the duration of surface exposure to cosmic rays.[45] This exposure age reflects the age of abandonment of a marine terrace by the sea.

To calculate the eustatic sea level for each dated terrace, it is assumed that the eustatic sea-level position corresponding to at least one marine terrace is known and that the uplift rate has remained essentially constant in each section.[2]

Relevance for other research areas

[edit]

Marine terraces play an important role in the research on tectonics and earthquakes. They may show patterns and rates of tectonic uplift[40][44][46] and thus may be used to estimate the tectonic activity in a certain region.[41] In some cases the exposed secondary landforms can be correlated with known seismic events such as the 1855 Wairarapa earthquake on the Wairarapa Fault near Wellington, New Zealand which produced a 2.7-metre (8 ft 10 in) uplift.[47] This figure can be estimated from the vertical offset between raised shorelines in the area.[48]

Furthermore, with the knowledge of eustatic sea level fluctuations, the speed of isostatic uplift can be estimated[49] and eventually the change of relative sea levels for certain regions can be reconstructed. Thus, marine terraces also provide information for the research on climate change and trends in future sea level changes.[10][50]

When analyzing the morphology of marine terraces, it must be considered, that both eustasy and isostasy can influence on the formation process. This way can be assessed, whether there were changes in sea level or whether tectonic activities took place.

Prominent examples

[edit]

Raised beaches are found in a wide variety of coast and geodynamical backgrounds such as subduction on the Pacific coasts of South and North America, passive margin of the Atlantic coast of South America,[51] collision context on the Pacific coast of Kamchatka, Papua New Guinea, New Zealand, Japan, passive margin of the South China Sea coast, on west-facing Atlantic coasts, such as Donegal Bay, County Cork and County Kerry in Ireland; Bude, Widemouth Bay, Crackington Haven, Tintagel, Perranporth and St Ives in Cornwall, the Vale of Glamorgan, Gower Peninsula, Pembrokeshire and Cardigan Bay in Wales, Jura and the Isle of Arran in Scotland, Finistère in Brittany and Galicia in Northern Spain and at Squally Point in Eatonville, Nova Scotia within the Cape Chignecto Provincial Park.

Other important sites include various coasts of New Zealand, e.g. Turakirae Head near Wellington being one of the world's best and most thoroughly studied examples.[47][48][52] Also along the Cook Strait in New Zealand, there is a well-defined sequence of uplifted marine terraces from the late Quaternary at Tongue Point. It features a well-preserved lower terrace from the last interglacial, a widely eroded higher terrace from the penultimate interglacial and another still higher terrace, which is nearly completely decayed.[47] Furthermore, on New Zealand's North Island at the eastern Bay of Plenty, a sequence of seven marine terraces has been studied.[12][37]

Along many coasts of the mainland and islands around the Pacific, marine terraces are typical coastal features. An especially prominent marine terraced coastline can be found north of Santa Cruz, near Davenport, California, where terraces probably have been raised by repeated slip earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault.[40][53] Hans Jenny famously researched the pygmy forests of the Mendocino and Sonoma county marine terraces. The marine terrace's "ecological staircase" of Salt Point State Park is also bound by the San Andreas Fault.

Along the coasts of South America marine terraces are present,[44][54] where the highest ones are situated where plate margins lie above subducted oceanic ridges and the highest and most rapid rates of uplift occur.[7][46] At Cape Laundi, Sumba Island, Indonesia an ancient patch reef can be found at 475 m (1,558 ft) above sea level as part of a sequence of coral reef terraces with eleven terraces being wider than 100 m (330 ft).[55] The coral marine terraces at Huon Peninsula, New Guinea, which extend over 80 km (50 mi) and rise over 600 m (2,000 ft) above present sea level[56] are currently on UNESCO's tentative list for world heritage sites under the name Houn Terraces - Stairway to the Past.[57]

Other considerable examples include marine terraces rising to 360 m (1,180 ft) on some Philippine Islands[58] and along the Mediterranean Coast of North Africa, especially in Tunisia, rising to 400 m (1,300 ft).[59]

Related coastal geography

[edit]Uplift can also be registered through tidal notch sequences. Notches are often portrayed as lying at sea level; however, notch types form a continuum from wave notches formed in quiet conditions at sea level to surf notches formed in more turbulent conditions and as much as 2 m (6.6 ft) above sea level.[60] As stated above, there was at least one higher sea level during the Holocene, so some notches may not contain a tectonic component in their formation.

See also

[edit]- Similar features

- Beach erosion and accretion

- Coastal management, to prevent coastal erosion and creation of beach

- Erosion

- Longshore drift

References

[edit]- ^ a b Pinter, N (2010): 'Coastal Terraces, Sealevel, and Active Tectonics' (educational exercise), from "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-10. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) [02/04/2011] - ^ a b c d e f g Pirazzoli, PA (2005a): 'Marine Terraces', in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 632–633

- ^ a b c d e Strahler AH; Strahler AN (2005): Physische Geographie. Ulmer, Stuttgart, 686 p.

- ^ Leser, H (ed)(2005): ‚Wörterbuch Allgemeine Geographie. Westermann&Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Braunschweig, 1119 p.

- ^ "The Nat -". www.sdnhm.org.

- ^ Johnson, ME; Libbey, LK (1997). "Global review of Upper Pleistocene (Substage 5e) Rocky Shores: tectonic segregation, substrate variation and biological diversity". Journal of Coastal Research.

- ^ a b Goy, JL; Macharé, J; Ortlieb, L; Zazo, C (1992). "Quaternary shorelines in Southern Peru: a Record of Global Sea-level Fluctuations and Tectonic Uplift in Chala Bay". Quaternary International. 15–16: 9–112. Bibcode:1992QuInt..15...99G. doi:10.1016/1040-6182(92)90039-5.

- ^ Rosenbloom, NA; Anderson, RS (1994). "Hillslope and channel evolution in a marine terraced landscape, Santa Cruz, California". Journal of Geophysical Research. 99 (B7): 14013–14029. Bibcode:1994JGR....9914013R. doi:10.1029/94jb00048.

- ^ Pethick, J (1984): An Introduction to Coastal Geomorphology. Arnold&Chapman&Hall, New York, 260p.

- ^ a b c d e f Masselink, G; Hughes, MG (2003): Introduction to Coastal Processes & Geomorphology. Arnold&Oxford University Press Inc., London, 354p.

- ^ a b c Cantalamessa, G; Di Celma, C (2003). "Origin and chronology of Pleistocene marine terraces of Isla de la Plata and of flat, gently dipping surfaces of the southern coast of Cabo San Lorenzo (Manabí, Ecuador)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 16 (8): 633–648. Bibcode:2004JSAES..16..633C. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2003.12.007.

- ^ a b Ota, Y; Hull, AG; Berryman, KR (1991). "Coseismic Uplift of Holocene Marine Terraces in the Pakarae River Area, Eastern North Island, New Zealand". Quaternary Research. 35 (3): 331–346. Bibcode:1991QuRes..35..331O. doi:10.1016/0033-5894(91)90049-B. S2CID 129630764.

- ^ Finkl, CW (2005): 'Coastal Soils' in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 278–302

- ^ James, N.P.; Mountjoy, E.W.; Omura, A. (1971). "An early Wisconsin reef Terrace at Barbados, West Indies, and its climatic implications". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 82 (7): 2011–2018. Bibcode:1971GSAB...82.2011J. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1971)82[2011:aewrta]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Chappell, J (1974). "Geology of coral terraces, Huon Peninsula, New Guinea: a study of Quaternary tectonic movements and sea Level changes". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 85 (4): 553–570. Bibcode:1974GSAB...85..553C. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1974)85<553:gocthp>2.0.co;2.

- ^ Bull, W.B., 1985. Correlation of flights of global marine terraces. In: Morisawa M. & Hack J. (Editor), 15th Annual Geomorphology Symposium. Hemel Hempstead, State University of New York at Binghamton, pp. 129–152.

- ^ Ota, Y (1986). "Marine terraces as reference surfaces in late Quaternary tectonics studies: examples from the Pacific Rim". Royal Society of New Zealand Bulletin. 24: 357–375.

- ^ Muhs, D.R.; et al. (1990). "Age Estimates and Uplift Rates for Late Pleistocene Marine Terraces: Southern Oregon Portion of the Cascadia Forearc". Journal of Geophysical Research. 95 (B5): 6685–6688. Bibcode:1990JGR....95.6685M. doi:10.1029/jb095ib05p06685.

- ^ a b c d Ahnert, F (1996) – Einführung in die Geomorphologie. Ulmer, Stuttgart, 440 p.

- ^ Lehmkuhl, F; Römer, W (2007): 'Formenbildung durch endogene Prozesse: Neotektonik', in Gebhardt, H; Glaser, R; Radtke, U; Reuber, P (ed) Geographie, Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. Elsevier, München, pp. 316–320

- ^ James, NP; Mountjoy, EW; Omura, A (1971). "An Early Wisconsin Reef Terrace at Barbados, West Indies, and ist Climatic Implications". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 82 (7): 2011–2018. Bibcode:1971GSAB...82.2011J. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1971)82[2011:AEWRTA]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Johnson, ME; Libbey, LK (1997). "Global Review of Upper Pleistocene (Substage 5e) Rocky Shores: Tectonic Segregation, Substrate Variation, and Biological Diversity". Journal of Coastal Research. 13 (2): 297–307.

- ^ Muhs, D; Kelsey, H; Miller, G; Kennedy, G; Whelan, J; McInelly, G (1990). "'Age Estimates and Uplift Rates for Late Pleistocene Marine Terraces' Southern Oregon Portion of the Cascadia Forearc'". Journal of Geophysical Research. 95 (B5): 6685–6698. Bibcode:1990JGR....95.6685M. doi:10.1029/jb095ib05p06685.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Worsley, P (1998): 'Altersbestimmung – Küstenterrassen', in Goudie, AS (ed) Geomorphologie, Ein Methodenhandbuch für Studium und Praxis. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 528–550

- ^ a b c d Anderson, RS; Densmore, AL; Ellis, MA (1999). "The Generation and degradation of Marine Terraces". Basin Research. 11 (1): 7–19. Bibcode:1999BasR...11....7A. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2117.1999.00085.x. S2CID 19075109.

- ^ Trenhaile, AS (2002). "Modeling the development of marine terraces on tectonically mobile rock coasts". Marine Geology. 185 (3–4): 341–361. Bibcode:2002MGeol.185..341T. doi:10.1016/S0025-3227(02)00187-1.

- ^ Pedoja, K.; Bourgeois, J.; Pinegina, T.; Higman, B. (2006). "Does Kamchatka belong to North America? An extruding Okhotsk block suggested by coastal neotectonics of the Ozernoi Peninsula, Kamchatka, Russia". Geology. 34 (5): 353–356. Bibcode:2006Geo....34..353P. doi:10.1130/g22062.1. Archived from the original on 2019-02-19. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ Pedoja, K.; Dumont, J-F.; Lamothe, M.; Ortlieb, L.; Collot, J-Y.; Ghaleb, B.; Auclair, M.; Alvarez, V.; Labrousse, B. (2006). "Quaternary uplift of the Manta Peninsula and La Plata Island and the subduction of the Carnegie Ridge, central coast of Ecuador". South American Journal of Earth Sciences. 22 (1–2): 1–21. Bibcode:2006JSAES..22....1P. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2006.08.003. S2CID 59487926.

- ^ Pedoja, K.; Ortlieb, L.; Dumont, J-F.; Lamothe, J-F.; Ghaleb, B.; Auclair, M.; Labrousse, B. (2006). "Quaternary coastal uplift along the Talara Arc (Ecuador, Northern Peru) from new marine terrace data". Marine Geology. 228 (1–4): 73–91. Bibcode:2006MGeol.228...73P. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2006.01.004. S2CID 129024575. Archived from the original on 2019-02-19. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ^ Kukla, G.J.; et al. (2002). "Last Interglacial Climates". Quaternary Research. 58 (1): 2–13. Bibcode:2002QuRes..58....2K. doi:10.1006/qres.2001.2316. S2CID 55262041.

- ^ Imbrie, J. et al., 1984. The orbital theory of Pleistocene climate: support from revised chronology of the marine 18O record. In: A. Berger, J. Imbrie, J.D. Hays, G. Kukla and B. Saltzman (Editors), Milankovitch and Climate. Reidel, Dordrecht, pp. 269–305.

- ^ Hearty, P.J.; Kindler, P. (1995). "Sea-Level Highstand Chronology from Stable Carbonate Platforms (Bermuda and the Bahamas)". Journal of Coastal Research. 11 (3): 675–689.

- ^ Zazo, C (1999). "Interglacial sea levels". Quaternary International. 55 (1): 101–113. Bibcode:1999QuInt..55..101Z. doi:10.1016/s1040-6182(98)00031-7.

- ^ Berryman, K (1992). "A stratigraphic age of Rotoehu Ash and late Pleistocene climate interpretation based on marine terrace chronology, Mahia Peninsula, North Island, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 35 (1): 1–7. Bibcode:1992NZJGG..35....1B. doi:10.1080/00288306.1992.9514494.

- ^ Bhattacharya, JP; Sheriff, RE (2011). "Practical problems in the application of the sequence stratigraphic method and key surfaces: integrating observations from ancient fluvial–deltaic wedges with Quaternary and modelling studies". Sedimentology. 58 (1): 120–169. Bibcode:2011Sedim..58..120B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.2010.01205.x. S2CID 128395986.

- ^ Schellmann, G; Brückner, H (2005): 'Geochronology', in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 467–472

- ^ a b Ota, Y (1992). "Holocene marine terraces on the northeast coast of North Island, New Zealand, and their tectonic significance". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 35 (3): 273–288. Bibcode:1992NZJGG..35..273O. doi:10.1080/00288306.1992.9514521.

- ^ Garnett, ER; Gilmour, MA; Rowe, PJ; Andrews, JE; Preece, RC (2003). "230Th/234U dating of Holocene tufas: possibilities and problems". Quaternary Science Reviews. 23 (7–8): 947–958. Bibcode:2004QSRv...23..947G. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.06.018.

- ^ Brückner, H (1980): 'Marine Terrassen in Süditalien. Eine quartärmorphologische Studie über das Küstentiefland von Metapont', Düsseldorfer Geographische Schriften, 14, Düsseldorf, Germany: Düsseldorf University

- ^ a b c Grove, K; Sklar, LS; Scherer, AM; Lee, G; Davis, J (2010). "Accelerating and spatially varying crustal uplift and ist geomorphic expression, San Andreas Fault zone north of San Francisco, California". Tectonophysics. 495 (3): 256–268. Bibcode:2010Tectp.495..256G. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2010.09.034.

- ^ a b Kim, Y; Kihm, J; Jin, K (2011). "Interpretation of the rupture history of a low slip-rate active fault by analysis of progressive displacement accumulation: an example from the Quaternary Eupcheon Fault, SE Korea". Journal of the Geological Society, London. 168 (1): 273–288. Bibcode:2011JGSoc.168..273K. doi:10.1144/0016-76492010-088. S2CID 129506275.

- ^ Perg, LA; Anderson, RS; Finkel, RC (2001). "Use of a new 10Be and 26Al inventory method to date marine terraces, Santa Cruz, California, USA". Geology. 29 (10): 879–882. Bibcode:2001Geo....29..879P. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0879:uoanba>2.0.co;2.

- ^ Kim, KJ; Sutherland, R (2004). "Uplift rate and landscape development in southwest Fiordland, New Zealand, determined using 10Be and 26Al exposure dating of marine terraces". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 68 (10): 2313–2319. Bibcode:2004GeCoA..68.2313K. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2003.11.005.

- ^ a b c Saillard, M; Hall, SR; Audin, L; Farber, DL; Hérail, G; Martinod, J; Regard, V; Finkel, RC; Bondoux, F (2009). "Non-steady long-term uplift rates and Pleistocene marine terrace development along the Andean margin of Chile (31°S) inferred from 10Be dating". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 277 (1–2): 50–63. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.277...50S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.09.039.

- ^ Gosse, JC; Phillips, FM (2001). "Terrestrial in situ cosmogenic nuclides: theory and application". Quaternary Science Reviews. 20 (14): 1475–1560. Bibcode:2001QSRv...20.1475G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.298.3324. doi:10.1016/s0277-3791(00)00171-2.

- ^ a b Saillard, M; Hall, SR; Audin, L; Farber, DL; Regard, V; Hérail, G (2011). "Andean coastal uplift and active tectonics in southern Peru: 10Be surface exposure dating of differentially uplifted marine terrace sequences (San Juan de Marcona, ~15.4°S)". Geomorphology. 128 (3): 178–190. Bibcode:2011Geomo.128..178S. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.01.004.

- ^ a b c Crozier, MJ; Preston NJ (2010): 'Wellington's Tectonic Landscape: Astride a Plate Boundary' in Migoń, P. (ed) Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. Springer, New York, pp. 341–348

- ^ a b McSaveney; et al. (2006). "Late Holocene uplift of beach ridges at Turakirae Head, south Wellington coast, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics. 49 (3): 337–358. Bibcode:2006NZJGG..49..337M. doi:10.1080/00288306.2006.9515172. S2CID 129074978.

- ^ Press, F; Siever, R (2008): Allgemeine Geologie. Spektrum&Springer, Heidelberg, 735 p.

- ^ Schellmann, G; Radtke, U (2007). "Neue Befunde zur Verbreitung und chronostratigraphischen Gliederung holozäner Küstenterrassen an der mittel- und südpatagonischen Atlantikküste (Argentinien) – Zeugnisse holozäner Meeresspiegelveränderungen". Bamberger Geographische Schriften. 22: 1–91.

- ^ Rostami, K.; Peltier, W.R.; Mangini, A. (2000). "Quaternary marine terraces, sea-level changes and uplift history of Patagonia, Argentina: comparisons with predictions of the ICE-4G (VM2) model for the global process of glacial isostatic adjustment". Quaternary Science Reviews. 19 (14–15): 1495–1525. Bibcode:2000QSRv...19.1495R. doi:10.1016/s0277-3791(00)00075-5.

- ^ Wellman, HW (1969). "Tilted Marine Beach Ridges at Cape Turakirae, N.Z.". Tuatara. 17 (2): 82–86.

- ^ Pirazzoli, PA (2005b.): 'Tectonics and Neotectonics', Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 941–948

- ^ Saillard, M; Riotte, J; Regard, V; Violette, A; Hérail, G; Audin, A; Riquelme, R (2012). "Beach ridges U-Th dating in Tongoy bay and tectonic implications for a peninsula-bay system, Chile". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 40: 77–84. Bibcode:2012JSAES..40...77S. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2012.09.001.

- ^ Pirazzoli, PA; Radtke, U; Hantoro, WS; Jouannic, C; Hoang, CT; Causse, C; Borel Best, M (1991). "Quaternary Raised Coral-Reef Terraces on Sumba Island, Indonesia". Science. 252 (5014): 1834–1836. Bibcode:1991Sci...252.1834P. doi:10.1126/science.252.5014.1834. PMID 17753260. S2CID 36558992.

- ^ Chappell, J (1974). "Geology of Coral Terraces, Huon Peninsula, New Guinea: A Study of Quaternary Tectonic Movements and Se-Level Changes". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 85 (4): 553–570. Bibcode:1974GSAB...85..553C. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1974)85<553:gocthp>2.0.co;2.

- ^ UNESCO (2006): Huon Terraces – Stairway to the Past. from https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5066/ [13/04/2011]

- ^ Eisma, D (2005): 'Asia, eastern, Coastal Geomorphology', in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 67–71

- ^ Orme, AR (2005): 'Africa, Coastal Geomorphology', in Schwartz, ML (ed) Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 9–21

- ^ Rust, D.; Kershaw, S. (2000). "Holocene tectonic uplift patternes in northeastern Sicily: evidence from marine notches in coastal outcrops". Marine Geology. 167 (1–2): 105–126. Bibcode:2000MGeol.167..105R. doi:10.1016/s0025-3227(00)00019-0.

External links

[edit]- Notes at NAHSTE

- US Geological Survey Marine Terrace Fact Sheet - Wikimedia link, USGS link

Raised beach

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Definition

A raised beach is a coastal landform consisting of a wave-cut platform or associated beach deposits, such as gravel or sand, that has been elevated above the present sea level due to a relative change in land and sea positions.[1] These features represent former shorelines preserved as flat or gently sloping terraces, often backed by cliffs or escarpments, and are distinct from active contemporary beaches that remain at or near current tidal levels.[8] In coastal geomorphology, their formation requires wave action to erode bedrock into platforms during higher relative sea levels, followed by sediment deposition from longshore currents and swash processes, creating accumulations like shingle ridges or shell fragments.[9] The concept of raised beaches emerged in the 19th century through geological observations of elevated shorelines bearing marine fossils, notably documented by Charles Darwin during his voyage on the HMS Beagle. Darwin described such features along the coasts of South America, including shelly beds near Valparaíso raised several hundred feet above the sea, interpreting them as evidence of recent land elevation.[10] These early accounts highlighted the role of vertical earth movements in preserving ancient coastal features, laying groundwork for understanding post-glacial landscapes.[11] Raised beaches differ from lowered beaches, also known as submarine terraces, which are submerged wave-cut platforms below current sea level resulting from relative sea level rise or land subsidence.[12] Unlike the exposed and often eroded raised forms, submarine terraces are typically preserved under sediment cover and require underwater surveying for identification. Morphological elements, such as erosional notches or depositional ridges, may be present but are secondary to the elevation defining the feature.[9]Morphological Features

Raised beaches are characterized by elevated wave-cut platforms, which form flat or gently inclined abrasion surfaces resulting from prolonged marine erosion. These platforms are often backed by sea cliffs or escarpments representing former coastal bluffs, with heights typically reaching 10-15 meters in areas like Scotland's west coast. Notches, as indentations carved at the platform-cliff junction, and beach ridges—linear mounds of coarser sediments parallel to the shore—commonly accompany these structures. Associated sediments include well-sorted gravel, sand, and shell deposits, which overlie the platforms and reflect wave-driven sorting and accumulation.[13][2][8] Morphological variations occur between inner and outer margins of the platforms, where inner edges near ancient cliffs exhibit steeper profiles and thicker sediment veneers, while outer margins slope more gradually toward the sea. Stepped profiles emerge from successive uplift episodes, creating tiered terraces such as the multiple platforms at Loch Tarbert, with higher levels up to 40 meters and lower ones at 3-5 meters above Ordnance Datum. Weathering on older beaches manifests as solution pits, up to 2 inches deep, or partial soil formation, softening the once-sharp landform edges.[2][14][8] These landforms generally occur at elevations of 1-30 meters above present sea level, though some reach up to 45 meters in glaciated regions, and extend 100-300 meters inland. For example, in southwest England, platforms at 5-25 feet above Ordnance Datum span widths suitable for modern agricultural use. Diagnostic criteria include abrupt seaward edges delineating the original abrasion limit and sorted sediments, such as rounded gravels or erratics, signaling former high-energy wave conditions.[8][14][13]Formation Processes

Tectonic and Isostatic Causes

Tectonic uplift contributes to the formation of raised beaches through vertical movements associated with faulting and folding along active plate margins. In subduction zones, where oceanic plates converge beneath continental plates, compressional forces lead to crustal deformation that elevates coastal landforms, often rapidly during seismic events. For instance, the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake caused coseismic uplift of up to 10 meters along parts of the southern Alaskan coast, preserving raised beaches on Montague Island through the sudden elevation of shorelines above sea level.[15] Such mechanisms are prevalent in the Pacific Ring of Fire, a belt of intense tectonic activity encircling the Pacific Ocean, where subduction-driven uplift has produced sequences of emergent marine terraces in regions like coastal Chile and Oregon.[16][17] Isostatic rebound, another key process, occurs when the Earth's crust rises in response to the removal of overlying ice loads following deglaciation. During periods of glaciation, the weight of ice sheets depresses the crust into the denser mantle; upon melting, the buoyant crust rebounds upward, elevating former shorelines to form raised beaches. This adjustment is particularly evident in formerly glaciated regions like Scandinavia, where postglacial rebound rates have reached up to 1-2 cm per year in areas such as northern Norway, gradually decreasing over millennia as equilibrium is approached.[18][19]Eustatic Sea Level Changes

Eustatic sea level changes refer to global variations in ocean water volume, primarily driven by the addition or removal of water to the world's oceans, independent of local tectonic or isostatic movements. These changes occur on a worldwide scale and are typically measured relative to the Earth's center, affecting the position of coastlines uniformly if land levels remain stable.[20][21] The primary drivers of eustatic changes include fluctuations in continental ice volume during glacial-interglacial cycles, where melting of ice sheets adds water to the oceans, and thermal expansion of seawater due to temperature variations. For instance, following the Last Glacial Maximum around 20,000 years ago, deglaciation led to a eustatic sea level rise of over 120 meters as vast ice sheets melted and contributed water to the global ocean. Additional factors, such as sedimentation in ocean basins, can gradually reduce basin capacity and influence long-term eustatic trends by altering the volume available for seawater.[22][23][24] Reconstructions of eustatic sea level curves rely heavily on oxygen isotope records (δ¹⁸O) from benthic foraminifera in deep-sea sediment cores, which serve as proxies for global ice volume and ocean temperature. These records reveal cyclic patterns tied to Milankovitch orbital forcings, with pronounced lowstands during glacial maxima and highstands during interglacials; for example, the Holocene epoch features a mid-Holocene highstand peaking between 6,000 and 4,000 years before present, reflecting residual ice melt and climatic optima. Such curves provide timelines for eustatic fluctuations, enabling correlations with coastal geomorphic features like raised beaches.[23][25][26] While absolute eustasy represents the global signal, relative sea level at any locality results from the superposition of eustatic changes with local tectonic or isostatic adjustments, which can elevate former shorelines to form raised beaches when the net effect exposes coastal deposits above the present sea level. In tectonically stable regions, eustatic falls during glacial advances directly contribute to beach uplift relative to the ocean, whereas in active areas, even minor eustatic variations can amplify exposure through interaction with vertical land motions.[21][20]Depositional and Erosional Processes

Raised beaches form through a combination of erosional and depositional processes active during their time at sea level, primarily driven by wave and tidal actions that sculpt coastal bedrock and accumulate sediments. Erosional processes dominate initial formation, where persistent wave abrasion erodes bedrock to create gently sloping platforms and associated notches at the base of cliffs.[27] In high-energy environments, waves grind against the shore, undercutting cliffs and producing planar benches that extend seaward, often covered by thin sediment veneers derived from the eroded material.[28] Tidal influences further contribute to cliff retreat by varying the zone of wave attack, exposing different elevations to abrasion during tidal cycles and accelerating overall coastal erosion.[27] As wave energy fluctuates, depositional processes become prominent, with sediments sorted and accumulated in characteristic landforms. Wave action sorts clastic materials by size and density, depositing coarser gravels and shingles near the high-tide mark while finer sands settle farther offshore, creating well-stratified sequences.[29] Berms emerge as low ridges of coarse sediment pushed up by storm waves at the backshore, often composed of rounded pebbles and cobbles that reflect high-energy sorting.[29] Shingle beaches, dominated by flattened or disc-shaped gravels, form through repeated wave swash and backwash, while cuspate forelands develop where converging longshore drifts accumulate sediment into pointed projections.[27] These features, observed in systems like those in Greenland's raised beach ridges, exhibit irregular stone arrangements indicating episodic storm deposition.[29] The typical sequence begins with erosion-dominated phases, where wave abrasion carves platforms and retreats cliffs, followed by quieter periods of sediment accumulation as energy wanes, leading to berm and ridge progradation.[27] Ground-penetrating radar studies of raised beach systems in Denmark reveal seaward-dipping beachface deposits overlying shoreface layers, marking this transition from erosional cut to depositional buildup over millennia.[30] In Alaska's Turnagain Arm, post-uplift observations confirm this progression, with initial rapid erosion of newly exposed surfaces giving way to sediment stabilization.[27] Preservation of these features occurs when sudden tectonic or isostatic uplift elevates the coastline above active marine processes, effectively fossilizing the platforms, berms, and associated deposits.[27] For instance, in southwest Korea's Sinan Archipelago, wave-cut benches at 4-5 meters above sea level remain intact due to episodic uplift, halting further erosion and deposition.[28] In Greenland, downlap points within beach ridges—transitions from beachface to shoreface—persist as reliable markers, protected from surface reworking by the uplift event.[29] This rapid elevation, often from seismic activity or glacial rebound, contrasts with gradual changes and ensures the morphological integrity of the raised beach.[30]Geological and Historical Context

Quaternary Sea Level Fluctuations

The Quaternary Period encompasses the last 2.58 million years of Earth's history and is defined by over 50 glacial-interglacial cycles, driven by orbital forcings that alternated between cold glacial phases with expanded ice sheets and warmer interglacials with reduced ice cover.[31][32] These cycles resulted in substantial eustatic sea level variations, with amplitudes exceeding 120 meters between glacial maxima and interglacial peaks, as water was repeatedly locked into or released from continental ice sheets.[33] The period's climate instability, particularly since the Mid-Pleistocene Transition around 1 million years ago, shifted cycle durations from about 41,000 years to dominant 100,000-year Milankovitch cycles, amplifying the scale of sea level oscillations.[34] A pivotal event in the late Quaternary was the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), centered around 21,000 to 19,000 years ago, when eustatic sea level reached approximately 120 meters below present levels due to the maximum extent of Northern Hemisphere ice sheets and expanded Antarctic ice.[35] This lowstand exposed vast continental shelves and facilitated land bridges, such as Beringia. Subsequent deglaciation triggered the Holocene transgression, a rapid rise in sea level averaging 10-20 millimeters per year from about 19,000 to 7,000 years ago, as meltwater from disintegrating ice sheets flooded ocean basins.[26] The transgression slowed after 7,000 years ago, leading to a mid-Holocene eustatic highstand around 6,000 years ago, when global sea levels stood 2 to 5 meters above present in far-field tropical regions, reflecting residual ice melt and thermal expansion before stabilization.[36] Reconstructions of Quaternary eustatic sea level curves rely on multiple proxies, including coral reef terraces in stable tectonic settings like the Huon Peninsula and Barbados, which preserve in situ growth at former sea levels and indicate stepwise rises during terminations.[37] Complementary data come from ice cores, such as the Vostok and EPICA Dome C records, and deep-sea sediment cores, where benthic foraminiferal δ¹⁸O values serve as a proxy for global ice volume and deep-ocean temperature, with heavier isotopes signaling glacial conditions and lighter ones interglacials. These curves depict quasi-periodic fluctuations, with rapid 5,000- to 10,000-year interglacial rises of up to 130 meters contrasting slower glacial buildups, and highlight meltwater pulses like those around 14,500 and 11,500 years ago that accelerated deglaciation.[26] Globally, eustatic signals exhibit latitudinal variations influenced by ice sheet proximity, with greater relative sea level falls near polar ice loads during glacials due to gravitational attraction and subsequent rebounds, exemplifying polar amplification in the overall climate-sea level system.[38] These patterns underscore the Quaternary's role as a template for understanding ice-volume-driven sea level dynamics, though local isostatic adjustments must be considered for regional interpretations.[39]Regional Land Uplift Histories

In the Fennoscandian region, postglacial isostatic rebound following the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) has resulted in substantial land uplift, with total crustal elevation reaching up to 830 meters in the central uplift cone relative to the pre-LGM baseline.[40] This uplift interacts with eustatic sea-level rise to produce extensive flights of raised beaches, particularly along the coasts of the Gulf of Bothnia, where relative sea-level fall has exposed shorelines elevated by 100–200 meters above modern levels. The process exemplifies how isostatic adjustment dominates local relative sea-level (RSL) curves, outpacing global meltwater contributions during deglaciation and leading to regressive beach sequences that record Holocene emergence rates exceeding 5 mm/year in peripheral zones.[41] On the tectonically active Huon Peninsula in Papua New Guinea, episodic uplift driven by subduction-related tectonics has formed a prominent staircase of raised coral terraces, with over 30 distinct levels preserving a record spanning the past 420,000 years.[42] Uplift rates vary spatially from 0.5 mm/year in the northwest to 3.5 mm/year in the southeast, elevating paleo-reefs and beaches to heights exceeding 400 meters, which allows precise reconstruction of interstadial highstands when combined with global eustatic curves.[42] This integration highlights how local tectonic forcing amplifies or counters eustatic signals, creating stepped morphologies that document coseismic events and long-term convergence dynamics.[43] Relative sea-level curves for the British Isles demonstrate the interplay of eustasy, isostatic rebound from the Celtic Ice Sheet, and peripheral forebulge collapse, with RSL histories varying markedly over 100–500 km scales. In northern regions like Scotland, post-LGM uplift of 10–20 meters during the early Holocene produced emergence-dominated curves, while southern areas experienced submergence due to collapsing Fennoscandian forebulges, resulting in raised beaches at elevations up to 40 meters above present. These curves, derived from over 2,100 indexed data points, constrain glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) models by isolating eustatic components from local vertical motions. Recent GPS measurements in the Holocene reveal ongoing uplift rates in Fennoscandia peaking at 10.2 mm/year near the Gulf of Bothnia, directly linking contemporary GIA to the elevation of late Holocene raised beaches observed at 5–10 meters above sea level.[44] These rates, consistent with GIA models like ICE-5G, indicate decelerating rebound that continues to influence beach morphology and coastal erosion patterns. In contrast, 2020s research highlights anthropogenic influences, such as groundwater extraction accelerating subsidence in coastal aquifers, which can enhance relative sea-level rise by 2–6 mm/year in urbanized regions and potentially reverse recent beach emergence trends.Identification and Mapping

Field Surveying Techniques

Field surveying techniques for raised beaches involve direct observation and measurement in coastal terrains to locate, document, and characterize these elevated marine landforms. Traditional methods emphasize systematic ground-based approaches to capture topographic, sedimentary, and stratigraphic details. Transect surveys, for instance, entail establishing linear profiles perpendicular to the coastline across suspected raised beach platforms, allowing geologists to record changes in slope, sediment type, and surface morphology along the line. These transects are typically spaced at regular intervals (e.g., 50–100 meters) to map the extent of terraces and ridges, providing a cross-sectional view of uplift or emergence patterns.[45] Leveling with optical instruments, such as automatic levels or theodolites, is a cornerstone for determining the elevation of raised beach features relative to modern sea level. Surveyors establish benchmarks tied to nearby tide gauges to measure heights accurately, often achieving precisions of ±0.01 meters over distances up to several kilometers. This technique reveals the vertical displacement of former shorelines, with elevations commonly ranging from a few meters to over 100 meters above present datum in glaciated regions. Sediment coring complements these surface methods by extracting vertical samples to examine stratigraphy beneath the beach platform. Hand augers or piston corers penetrate up to 5–10 meters, revealing layered deposits of beach sands, gravels, and overlying soils that indicate marine origins and post-depositional alterations. Cores help distinguish raised beaches from fluvial or glacial features through grain size gradients and bedding structures, such as cross-laminated foreshore sands overlain by peat or till. In tectonically active areas like coastal Portugal, conventional coring has documented Pleistocene sequences with marine sands at depths corresponding to isotope stages 5 and 7.[46] Key identification relies on diagnostic marine indicators preserved in the field. Marine fossils, including mollusks (e.g., Patella spp.) and barnacles, embedded in cemented gravels or notches, confirm a littoral environment, often appearing as articulated shells or borings in bedrock platforms. Soil profiles across raised beaches show progressive development with age, from weakly podzolized sands on younger terraces to deeply weathered, humic layers on older ones, with rubification and melanization signaling exposure duration. Elevation measurements, benchmarked against tide gauges, quantify emergence; for instance, platforms at 5–15 meters above mean sea level typically correlate with Holocene highstands. These proxies collectively differentiate raised beaches from erosional benches or talus slopes.[47][29] Fieldwork faces several challenges that can obscure or complicate documentation. Dense vegetation cover, such as grasses or shrubs colonizing platforms within years of emergence, rapidly masks subtle topographic steps and sediment exposures, particularly on low-relief terraces under 10 meters high; in Alaska's 1964 earthquake-raised beaches, conifer seedlings obliterated marine forms in just 15 months. Erosion further degrades features, with wave undercutting, gullying, and talus accumulation smoothing cliffs and burying break-of-slope indicators, leading to up to 50% volume loss in bay-head deposits over short timescales. Safety concerns are paramount on cliffed coasts, where unstable overhangs, rockfalls, and tidal surges pose risks; protocols include maintaining distance from edges, using harnesses for descents, and monitoring weather to avoid isolation.[45] Historically, field surveying of raised beaches evolved from 19th-century manual mapping, where geologists like De la Beche (1839) and Prestwich (1892) sketched distributions and elevations using tape measures and spirit levels along British coasts, identifying over 20 platforms through visual inspection. Early 20th-century efforts incorporated Geological Survey memoirs for regional correlations, emphasizing fossil content and cliff profiles. By the mid-20th century, integration of stratigraphic logging refined age assignments, as in Arkell's (1943) work on relative dating. Modern practice builds on these foundations by incorporating digital tools like GPS for transect positioning, though core methods remain analog to ensure precision in rugged terrains; this hybrid approach often references remote sensing for initial site selection.[14]Remote Sensing and GIS Methods

Remote sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) technologies have revolutionized the large-scale mapping and analysis of raised beaches by providing high-resolution topographic data and enabling the integration of multi-temporal datasets. These methods allow for the non-invasive detection of subtle coastal terraces, which are key indicators of past sea-level positions and land uplift. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), in particular, generates detailed digital elevation models (DEMs) with resolutions as fine as 0.5 meters, facilitating the identification of terrace morphology through elevation profiling and slope analysis.[48] For broader regional coverage, satellite imagery from platforms like Landsat and Sentinel-2 contributes to DEM creation and vegetation/sediment differentiation, often achieving 10-30 meter resolutions suitable for initial terrace delineation.[49] GIS platforms, such as ArcGIS, integrate these DEMs with historical sea-level reconstructions to overlay paleoshoreline data, enabling the quantification of uplift rates. By querying low-relief, gently sloping surfaces (e.g., slopes ≤15° and relief ≤15 m), GIS algorithms extract terrace boundaries and correlate elevations with dated sea-level highstands, yielding uplift estimates like 0.2-2.5 m/ka in tectonically active regions.[50] This approach has been applied to model isostatic rebound, as seen in Antarctic Peninsula raised beaches where DEM overlays reveal Holocene uplift of up to 50 m.[51] Recent advances include drone-based photogrammetry, which produces centimeter-scale DEMs for high-resolution terrace mapping in inaccessible coastal areas, complementing LiDAR for site-specific validation.[52] Machine learning techniques, such as Gaussian Mixture Models, automate terrace classification in DEMs by clustering elevation and slope data, improving detection accuracy over manual methods and enabling global-scale analysis of marine versus fluvial landforms.[48] Post-2020 developments in hyperspectral imaging, often integrated with Sentinel data, enhance sediment composition analysis on raised beach deposits, distinguishing lithologies through spectral signatures for refined paleoenvironmental mapping.[53] These tools collectively support scalable monitoring, though field validation remains essential for accuracy.[50]Dating and Correlation

Relative Dating Approaches

Relative dating approaches for raised beaches rely on establishing chronological sequences through geological relationships and environmental markers, without providing numerical ages. Stratigraphic superposition is a foundational technique, where the vertical stacking of beach deposits and overlying sediments indicates relative age; for instance, higher-elevation terraces, formed during earlier highstands and subsequently uplifted, overlie or are cut into lower ones, allowing reconstruction of terrace formation order.[54] This method is particularly effective in sequences with non-marine cover deposits, such as loess or tephras, which enable local correlations across sites.[54] Additional techniques involve biological markers, including index fossils and amino acid racemization (AAR). Marine mollusks, such as those from genera like Patella or Strombus, serve as index fossils when their assemblages match known faunal ranges tied to specific interglacial periods, facilitating correlation between local beach deposits and broader Quaternary chronologies.[55] AAR measures the post-mortem conversion of L-amino acids to D-forms in mollusk shells, yielding D/L ratios that increase predictably with time under stable temperature conditions; for example, ratios around 0.40–0.43 in Epilucina shells from California terraces indicate relative ages of approximately 125 ka.[54][56] This closed-system analysis of intracrystalline proteins provides resolution on the order of 20–200 ka, depending on climate.[56] Correlation to global sea-level index points further refines relative sequences by matching beach "flights"—sets of terraces at similar elevations—to marine oxygen isotope stages (OIS), which record interglacial highstands. For example, terrace elevations and fossil signatures in south-central California correlate lower flights to OIS 5a (80 ka) and 5e (120 ka), with higher ones to OIS 7 (210 ka) and 9 (330 ka), based on consistent altitudinal spacing and geomorphic expression.[57] These alignments assume linkages between eustatic sea-level peaks and terrace formation, enabling regional comparisons.[57] Despite their utility, these approaches have limitations, including the assumption of uniform tectonic uplift rates, which can lead to errors of tens to hundreds of thousands of years if rates vary, as observed near faults in California where terrace spacing is inconsistent.[57][54] Temperature fluctuations also affect AAR rates, reducing precision in variable climates.[56] In applications, relative dating excels at establishing sequences in multi-terrace sites, such as those along the Pacific coast, where it delineates formation order for tectonic and paleoenvironmental analyses; absolute methods can calibrate these sequences for refined chronologies.[54][57]Absolute Dating Techniques

Absolute dating techniques provide numerical ages in calendar years for raised beach deposits, enabling precise reconstruction of formation events and associated sea-level changes. These methods are essential for establishing chronologies beyond relative sequencing, particularly for Quaternary coastal landforms influenced by eustatic fluctuations and isostatic uplift. Common approaches include radiocarbon dating for organic materials, uranium-thorium (U-Th) dating for corals, and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) for sediments, each suited to specific time ranges and materials found in raised beach sequences.[58][59] Radiocarbon (¹⁴C) dating is widely applied to organic shells and plant remains in raised beach deposits, offering reliable ages up to approximately 50 ka. Sample preparation involves physical cleaning to remove contaminants, followed by acid etching or bleaching to isolate pure carbonate or organic fractions, and analysis via accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS). Ages are calibrated using curves such as IntCal20 for terrestrial samples or Marine20 for marine-influenced materials, incorporating reservoir corrections (ΔR) of 200–300 years for coastal shells to account for oceanic carbon reservoir effects. Error ranges typically span ±50–200 years at 95% confidence, though older samples (>30 ka) may reach ±500 years due to calibration uncertainties and low carbon levels. For instance, in Iranian Makran raised beaches, ¹⁴C dating of mollusk shells yielded calibrated ages of 33.4 ± 0.42 ka for terrace T1, confirming Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 3 deposition.[60][58][59] U-Th dating targets aragonitic corals preserved in raised beach or reef sequences, providing high-precision ages up to 500 ka without needing calibration curves, as it relies on the decay of uranium isotopes to thorium. Protocols include micro-drilling clean coral interiors to avoid diagenetic alteration, chemical dissolution in nitric acid, and mass spectrometry to measure ²³⁰Th/²³⁸U and ²³⁴U/²³⁸U ratios, with initial ²³⁴U/²³⁸U assumed at secular equilibrium (1.0–1.2). Error ranges are typically ±1–5% of the age, or ±50–500 years for Holocene samples, though open-system behavior from uranium migration can yield minimum ages. In Saudi Arabian Red Sea raised coral terraces, U-Th dates ranged from 120–130 ka for MIS 5e platforms, establishing eustatic sea-level benchmarks.[61][62] OSL dating measures the time since quartz or feldspar grains in beach sediments were last exposed to sunlight, ideal for sandy deposits lacking organics and extending to 100–200 ka. Sample preparation entails collecting opaque tubes to prevent light exposure, followed by wet sieving for 90–125 µm grains, etching with hydrofluoric acid (HF) to purify quartz, and testing for feldspar contamination via infrared stimulation. The single aliquot regenerative (SAR) protocol assesses equivalent dose (D_e) through dose-response curves, with environmental dose rates calculated from radionuclide concentrations (U, Th, K) via gamma spectrometry and assuming 15–25% water content. Error ranges are 5–15% (±500–2000 years), influenced by incomplete bleaching or signal fading, which is corrected using g-value assessments. In Norwegian southeastern raised beaches, OSL ages of 10–12 ka confirmed post-glacial emergence rates.[63][64][58] Advances in absolute dating include Bayesian modeling to refine age-depth relationships in stratigraphic sequences of raised beaches, integrating multiple dates with prior depositional assumptions for probabilistic outputs. Software like OxCal or Bacon incorporates calibration curves and stratigraphic constraints to model accumulation rates, reducing uncertainties by 20–50% in composite profiles. For example, Bayesian analysis of ¹⁴C and OSL dates from Scottish coastal sequences yielded refined Holocene emergence curves with 95% confidence intervals narrowed to ±100 years.[65][66] Emerging applications in the 2020s involve cosmogenic nuclide dating, such as ¹⁰Be exposure ages, to quantify surface stabilization times in rocky raised beach platforms up to 100 ka. Protocols extract ¹⁰Be from quartz via chemical isolation and AMS, scaling production rates for latitude and elevation with erosion corrections (<1 mm/ka). Errors range ±5–10% (±300–1000 years), with recent Antarctic Peninsula studies dating raised beaches to 8–12 ka, linking emergence to ice unloading. These methods complement traditional techniques by targeting bedrock exposure rather than sediments.[67][68]Scientific Significance

Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction

Raised beaches preserve sedimentary archives that enable paleoenvironmental reconstructions of past coastal climates and ecosystems through various proxies embedded in their deposits. Pollen grains found in organic-rich sediments associated with raised beach formations, such as peat layers or backshore lagoons, serve as indicators of contemporaneous vegetation cover, revealing shifts in terrestrial plant communities driven by climate variability and sea-level changes.[69] Foraminiferal assemblages in the marine sands and gravels of raised beaches provide insights into water temperatures, salinity, and depth during deposition; for instance, benthic species like those from Arctic-Boreal assemblages in Svalbard's Pleistocene raised beaches indicate moderate salinities and temperatures influenced by Atlantic water inflows, with ecological preferences allowing inference of paleotemperatures around 4–8°C during interglacial phases.[70] Storm deposits within these elevated shorelines, such as overwash layers or coarse gravel lags, act as proxies for paleotempests by recording extreme wave events, with their elevation and sedimentology reflecting past storm intensity and frequency in regions like Antarctica, where Holocene raised beaches link coastal morphology to climatic shifts in storminess.[71] These proxies facilitate reconstructions of key paleoenvironmental conditions, including interglacial warmth and sea-level stability. During the Last Interglacial (~129–116 ka), raised beaches in northwest Europe, such as those in Britain at elevations of 4–6 m above present, indicate higher global mean sea levels (up to 5.7 m eustatic equivalent from Antarctic sources) driven by warmer polar temperatures and partial ice sheet retreat, with stable coastal positions suggesting prolonged highstands under warmer-than-present climates.[72] Sea-level stability is inferred from the morphostratigraphy of raised beach ridges, where consistent elevations and minimal erosion in Holocene sequences point to periods of equilibrium between eustatic rise and isostatic adjustment, supporting reconstructions of balanced coastal ecosystems with diverse marine-terrestrial interfaces.[5] Coastal ecosystems are further illuminated by integrated proxy data, showing transitions from open marine to brackish environments that harbored mixed assemblages of foraminifera and pollen-indicated vegetation, such as salt-tolerant herbs and shrubs during mid-Holocene stability.[70] Elevations of raised beaches are instrumental in validating geophysical models of ice sheet dynamics and future sea-level projections. In Greenland, ground-penetrating radar profiling of Holocene raised beach ridges reveals internal structures marking former low-tide levels at heights up to 80 m, providing precise relative sea-level curves that calibrate models of Greenland Ice Sheet thickness variations and their isostatic effects on global sea level.[5] Key studies highlight mid-Holocene climate optima through raised beach data; for example, macrofossil-bearing beaches at Potter Peninsula, Antarctica (~6–4 ka), preserve evidence of warmer conditions with elevated sea levels and penguin colony expansions, aligning with regional optima of 1–2°C above present temperatures before Neoglacial cooling.[73] Recent advancements as of 2025, including cosmogenic ¹⁰Be dating of raised beaches in Arctic regions, further refine relative sea-level histories and ice sheet contributions to past and future changes.[74] These findings underscore raised beaches' role in testing ice sheet models against empirical sea-level histories, enhancing predictions of centennial-scale changes under ongoing warming.[5]Archaeological and Cultural Relevance

Raised beaches serve as important archaeological repositories, preserving evidence of prehistoric human activity tied to fluctuating sea levels. Shell middens—accumulations of discarded shellfish remains—frequently occur on these elevated coastal platforms, indicating that early hunter-gatherers exploited marine resources when the beaches were at or near contemporary sea levels before subsequent uplift or regression. For instance, at the Tarradale site in Scotland, multiple Mesolithic shell middens dating to around 6000–7000 years ago were discovered on a raised beach, suggesting repeated occupation and adaptation to post-glacial environmental shifts.[75] Similarly, in Cape York Peninsula, Australia, shell mounds and middens on raised beaches from the mid-Holocene reflect sustained coastal foraging strategies amid sea level stabilization.[76] These deposits often contain associated artifacts, such as lithic tools and bone implements, demonstrating technological responses to marine habitats that are now inland.[77] Stone tools and other artifacts found on raised beaches further highlight human adaptation to dynamic coastal environments during the Paleolithic. In western Portugal's Estremadura region, Late Pleistocene raised beaches from Marine Isotope Stages 5 and 3 (approximately 120,000–30,000 years ago) yield flint tools and debitage, evidencing episodic occupations by Neanderthals and early modern humans along tectonically active coasts.[78] These elevated platforms provided stable locations for processing marine and terrestrial resources, with tools like scrapers and points adapted for shellfish harvesting and hunting. In Atlantic Iberia, coastal sites on raised marine terraces reveal a pattern of resilient hunter-gatherer mobility, linking Paleolithic populations to now-uplifted shorelines that facilitated resource access during interglacial periods.[79] Raised beaches in Europe connect to broader Paleolithic migration patterns, particularly along submerged or uplifted coastal corridors. Sites near the present-day coasts of Britain, such as Pakefield and Happisburgh in East Anglia, contain Acheulean handaxes and flakes from raised beach contexts dating to 500,000–700,000 years ago, suggesting early hominins followed coastal routes during glacial-interglacial cycles.[80] In the western Mediterranean, raised beaches in Portugal's paleo-seascapes indicate that coastal adaptations supported migrations from Africa into Iberia around 40,000 years ago, with artifacts reflecting exploitation of now-elevated estuaries.[81] These locations underscore raised beaches as waypoints in human dispersal, bridging terrestrial and marine ecosystems. The cultural significance of raised beaches extends to indigenous perspectives on landscape transformation and contemporary heritage efforts. Among Australian Aboriginal communities, shell middens on raised beaches encode oral histories of sea level changes and resource management, preserving knowledge of ancestral adaptations to coastal uplift and erosion over millennia.[82] In North America, Native American groups in regions like the Chesapeake Bay recognize elevated shell middens as cultural landmarks, integrating traditional ecological knowledge of land changes into modern stewardship practices.[83] Today, these sites face threats from erosion and development, prompting international initiatives for protection; for example, UNESCO and local agencies advocate for monitoring and conservation of raised beach archaeology to safeguard intangible cultural values.[84] Recent genomic research in the 2020s has begun integrating raised beach chronologies with ancient DNA to refine models of human dispersal along prehistoric coasts. Studies of South American Atlantic coast populations reveal genetic signals of coastal migrations around 15,000–10,000 years ago, corroborated by dated raised beach sites that align with admixture events in indigenous genomes.[85] In Europe, paleogenomic analyses tie Iberian raised beach occupations to early Upper Paleolithic gene flows, highlighting how beach chronologies provide temporal anchors for tracking population movements.[86] These findings emphasize the interplay between anthropogenic evidence on raised beaches and broader human evolutionary histories.Applications in Hazard Assessment

Raised beaches serve as valuable analogues for predicting future land uplift or subsidence patterns, enabling assessments of relative sea level changes that influence coastal hazards such as erosion and inundation. By dating these features using methods like radiocarbon analysis on associated sediments, scientists quantify historical isostatic rebound rates, which inform models of ongoing vertical land movements in glaciated regions. For example, in near-field areas like Scotland, raised beaches reveal uplift rates that counteract eustatic sea level rise, providing baseline data for projecting local coastal stability under climate-driven scenarios.[87] Analysis of paleotsunami deposits preserved in raised beaches facilitates modeling of tsunami run-up heights and inland flooding risks, enhancing preparedness for seismic coastal hazards. These deposits record past wave energies and flow dynamics, allowing reconstruction of event magnitudes through sediment characteristics and topographic context. In Seaside, Oregon, studies of cobble ridges overtopped by paleotsunamis approximately 1.3 ka and 2.6 ka indicate run-up heights exceeding 10 m (adjusted for paleo-sea level), with modeled flow depths of 0.5–2 m generating bed shear stresses up to 3,300 dyne cm⁻²—critical thresholds for hazard zoning in interridge valleys.[88] Incorporation of raised beach data into IPCC-aligned risk modeling refines evaluations of coastal vulnerability by accounting for local tectonic influences on sea level projections. These features help validate and calibrate scenarios for accelerated rise, such as those estimating 0.44–0.76 m (likely range, median 0.55 m) by 2100 under SSP2-4.5, by evidencing past contributions from ice sheet melt.[89] For instance, fossilized beaches in southwest England document a 5.7 m rise from Antarctic deglaciation during the last interglacial (129–116 ka), isolated from northern hemisphere effects due to isostatic rebound, thus informing regional hazard assessments.[72] Recent studies as of 2025 using raised beach records to fingerprint ancient ice sheet contributions further support refined projections of future sea level rise under warming scenarios.[90] Assessments of accelerated sea level rise increasingly focus on threats to preserved raised beach sites, which face erosion or re-inundation that could obscure geological records essential for long-term hazard forecasting. In tectonically active areas, historical uplift rates derived from these sites—such as 1–2 mm/year in parts of the UK—briefly contextualize potential subsidence reversals, but primary emphasis remains on integrating such data into dynamic vulnerability frameworks to protect these indicators. Emerging integrations of raised beach chronologies with climate models support probabilistic hazard mapping, combining uplift histories with sea level projections to delineate risk zones for compound events like storms and tectonics. This approach enhances spatial accuracy in tools like coastal vulnerability indices, prioritizing adaptation in low-lying areas by simulating scenarios with uncertainties in ice melt and land motion.Notable Examples

European Raised Beaches

Prominent raised beach sequences in Europe are exemplified by the multiple Holocene terraces along the Scottish west coast, where glacial isostatic rebound has preserved well-defined shorelines in areas such as the mainland Ayrshire coast and the offshore Isle of Bute in southwest Scotland. These terraces include the Main Postglacial Shoreline, dated to approximately 7800–6500 BP and marked by the highest beach ridges at 12–13 meters above present sea level, alongside the younger Blairdrummond Shoreline at around 4200 cal BP.[91] In the Mediterranean region, the Italian Tyrrhenian coast features elaborate staircase sequences of raised marine terraces, notably between Civitavecchia and the Fiora River in central Italy, where three terraces correlate with Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 5e, 5c, and 5a, forming stepped morphologies at elevations of 0–40 meters above sea level.[92] Further examples occur along the Latium coast, with terraces from MIS 9 to MIS 5 creating staircases up to 108 meters high, illustrating long-term coastal evolution.[93] In northern Europe, glacial rebound dominates the characteristics of these raised beaches, elevating Holocene features to 5–20 meters above current sea levels through post-glacial isostatic adjustment in regions like Scotland and Scandinavia, where rapid land uplift followed the retreat of the last Ice Age ice sheets.[94] These beaches often consist of wave-deposited sands and gravels overlying older sediments, with sequences reflecting relative sea-level falls after an early Holocene rise around 9900–9500 BP.[95] They are frequently associated with Mesolithic sites, evidencing early hunter-gatherer exploitation of coastal resources; for instance, in the Forth lowland of Scotland, Mesolithic activity aligns with rising sea levels, while in northeast Ireland, abundant sites from Carlingford Lough to the Lower Bann River overlie post-glacial raised beach deposits, revealing stratified tool assemblages and middens.[96] In southern Europe, such as the Tyrrhenian staircases, tectonic uplift combines with eustatic influences to produce biodetrital conglomerates and cemented "panchina" layers, highlighting differential preservation compared to northern rebound-dominated forms.[92] Research on European raised beaches originated with British geologists in the 19th century, who conducted early surveys and measurements in Scotland, including Robert Chambers' documentation of post-glacial elevations that advanced understanding of isostatic changes.[97] Foundational work by the Geological Survey mapped features like the "25 ft beach" in the Northern Highlands, establishing stratigraphic correlations for late-glacial and Holocene shorelines with gradients of 0.12 m/km near Inverness.[8] Modern studies have incorporated LiDAR mapping to refine terrace morphology and coastal evolution, as demonstrated in southwest Scotland's Luce Bay, where high-resolution topographic data reveal mid- to late-Holocene shoreline migrations and dune interactions with raised beaches.[98] A distinctive feature of Scottish raised beaches is their incorporation of Storegga Slide tsunami deposits from approximately 8100 BP (around 7000 14C years BP), identified as prominent sand sheets within Holocene sediments along both eastern and western coasts, attaining run-up heights of 3–6 meters on the mainland and up to 20 meters in Shetland.[99] These deposits, unique for their integration into the Main Postglacial Shoreline sequence, offer evidence of a massive submarine landslide off Norway's coast that disrupted Mesolithic coastal settlements and contributed to the geological record of prehistoric hazards.[95]Global Case Studies