Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein

View on Wikipedia| Sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

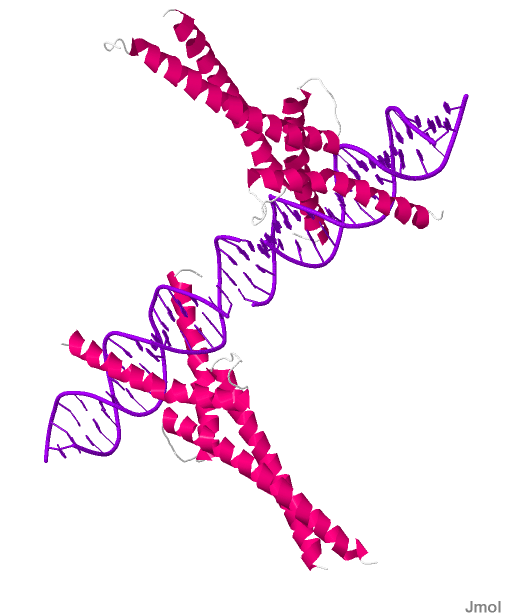

X-ray crystallography of Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein 1A with polydeoxyribonucleotide.[1] | |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | SREBF1 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 6720 | ||||||

| HGNC | 11289 | ||||||

| OMIM | 184756 | ||||||

| PDB | 1am9 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_004176 | ||||||

| UniProt | P36956 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 17 p11.2 | ||||||

| |||||||

| sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | SREBF2 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 6721 | ||||||

| HGNC | 11290 | ||||||

| OMIM | 600481 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_004599 | ||||||

| UniProt | Q12772 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 22 q13 | ||||||

| |||||||

Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) are transcription factors that bind to the sterol regulatory element DNA sequence TCACNCCAC.[2] Mammalian SREBPs are encoded by the genes SREBF1 and SREBF2. SREBPs belong to the basic-helix-loop-helix leucine zipper class of transcription factors.[3] Unactivated SREBPs are attached to the nuclear envelope and endoplasmic reticulum membranes. In cells with low levels of sterols, SREBPs are cleaved to a water-soluble N-terminal domain that is translocated to the nucleus. These activated SREBPs then bind to specific sterol regulatory element DNA sequences, thus upregulating the synthesis of enzymes involved in sterol biosynthesis.[4][5] Sterols in turn inhibit the cleavage of SREBPs and therefore synthesis of additional sterols is reduced through a negative feed back loop.

Isoforms

[edit]Mammalian genomes have two separate SREBP genes (SREBF1 and SREBF2):

- SREBP-1 expression produces two different isoforms, SREBP-1a and -1c. These isoforms differ in their first exons owing to the use of different transcriptional start sites for the SREBP-1 gene. SREBP-1c was also identified in rats as ADD-1. SREBP-1c is responsible for regulating the genes required for de novo lipogenesis.[6]

- SREBP-2 regulates the genes of cholesterol metabolism.[6]

Function

[edit]SREB proteins are indirectly required for cholesterol biosynthesis and for uptake and fatty acid biosynthesis. These proteins work with asymmetric sterol regulatory element (StRE). SREBPs have a structure similar to E-box-binding helix-loop-helix (HLH) proteins. However, in contrast to E-box-binding HLH proteins, an arginine residue is replaced with tyrosine making them capable of recognizing StREs and thereby regulating membrane biosynthesis.[7]

Mechanism of action

[edit]

Animal cells maintain proper levels of intracellular lipids (fats and oils) under widely varying circumstances (lipid homeostasis).[8][9][10] For example, when cellular cholesterol levels fall below the level needed, the cell makes more of the enzymes necessary to make cholesterol. A principal step in this response is to make more of the mRNA transcripts that direct the synthesis of these enzymes. Conversely, when there is enough cholesterol around, the cell stops making those mRNAs and the level of the enzymes falls. As a result, the cell quits making cholesterol once it has enough.

A notable feature of this regulatory feedback machinery was first observed for the SREBP pathway - regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP). Subsequently, RIP was found to be used in almost all organisms from bacteria to human beings and regulates a wide range of processes ranging from development to neurodegeneration.

A feature of the SREBP pathway is the proteolytic release of a membrane-bound transcription factor, SREBP. Proteolytic cleavage frees it to move through the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, SREBP can bind to specific DNA sequences (the sterol regulatory elements or SREs) that are found in the control regions of the genes that encode enzymes needed to make lipids. This binding to DNA leads to the increased transcription of the target genes.

The ~120 kDa SREBP precursor protein is anchored in the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and nuclear envelope by virtue of two membrane-spanning helices in the middle of the protein. The precursor has a hairpin orientation in the membrane, so that both the amino-terminal transcription factor domain and the COOH-terminal regulatory domain face the cytoplasm. The two membrane-spanning helices are separated by a loop of about 30 amino acids that lies in the lumen of the ER. Two separate, site-specific proteolytic cleavages are necessary for release of the transcriptionally active amino-terminal domain. These cleavages are carried out by two distinct proteases, called site-1 protease (S1P) and site-2 protease (S2P).

In addition to S1P and S2P, the regulated release of transcriptionally active SREBP requires the cholesterol-sensing protein SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP), which forms a complex with SREBP owing to interaction between their respective carboxy-terminal domains. SCAP, in turn, can bind reversibly with another ER-resident membrane protein, INSIG. In the presence of sterols, which bind to INSIG and SCAP, INSIG and SCAP also bind one another. INSIG always stays in the ER membrane and thus the SREBP-SCAP complex remains in the ER when SCAP is bound to INSIG. When sterol levels are low, INSIG and SCAP no longer bind. Then, SCAP undergoes a conformational change that exposes a portion of the protein ('MELADL') that signals it to be included as cargo in the COPII vesicles that move from the ER to the Golgi apparatus. In these vesicles, SCAP, dragging SREBP along with it, is transported to the Golgi. The regulation of SREBP cleavage employs a notable feature of eukaryotic cells, subcellular compartmentalization defined by intracellular membranes, to ensure that cleavage occurs only when needed.

Once in the Golgi apparatus, the SREBP-SCAP complex encounters active S1P. S1P cleaves SREBP at site-1, cutting it into two halves. Because each half still has a membrane-spanning helix, each remains bound in the membrane. The newly generated amino-terminal half of SREBP (which is the ‘business end' of the molecule) then goes on to be cleaved at site-2 that lies within its membrane-spanning helix. This is the work of S2P, an unusual metalloprotease. This releases the cytoplasmic portion of SREBP, which then travels to the nucleus where it activates transcription of target genes (e.g. LDL receptor gene)

Regulation

[edit]Absence of sterols activates SREBP, thereby increasing cholesterol synthesis.[11]

Insulin, cholesterol derivatives, T3 and other endogenous molecules have been demonstrated to regulate the SREBP1c expression, particularly in rodents. Serial deletion and mutation assays reveal that both SREBP (SRE) and LXR (LXRE) response elements are involved in SREBP-1c transcription regulation mediated by insulin and cholesterol derivatives. Peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) agonists enhance the activity of the SREBP-1c promoter via a DR1 element at -453 in the human promoter. PPARα agonists act in cooperation with LXR or insulin to induce lipogenesis.[12]

A medium rich in branched-chain amino acids stimulates expression of the SREBP-1c gene via the mTORC1/S6K1 pathway. The phosphorylation of S6K1 was increased in the liver of obese db/db mice. Furthermore, depletion of hepatic S6K1 in db/db mice with the use of an adenovirus vector encoding S6K1 shRNA resulted in down-regulation of SREBP-1c gene expression in the liver as well as a reduced hepatic triglyceride content and serum triglyceride concentration.[13]

mTORC1 activation is not sufficient to stimulate hepatic SREBP-1c in the absence of Akt signaling, revealing the existence of an additional downstream pathway also required for this induction which is proposed to involve mTORC1-independent Akt-mediated suppression of INSIG-2a, a liver-specific transcript encoding the SREBP-1c inhibitor INSIG2.[14]

FGF21 has been shown to repress the transcription of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c). Overexpression of FGF21 ameliorated the up-regulation of SREBP-1c and fatty acid synthase (FAS) in HepG2 cells elicited by FFAs treatment. Moreover, FGF21 could inhibit the transcriptional levels of the key genes involved in processing and nuclear translocation of SREBP-1c, and decrease the protein amount of mature SREBP-1c. Unexpectedly, overexpression of SREBP-1c in HepG2 cells could also inhibit the endogenous FGF21 transcription by reducing FGF21 promoter activity.[15]

SREBP-1c has also been shown to upregulate in a tissue specific manner the expression of PGC1alpha expression in brown adipose tissue.[16]

Nur77 is suggested to inhibit LXR and downstream SREBP-1c expression modulating hepatic lipid metabolism.[17]

History

[edit]The SREBPs were elucidated in the laboratory of Nobel laureates Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Their first publication on this subject appeared in October 1993.[3][18]

References

[edit]- ^ PDB: 1AM9; Párraga A, Bellsolell L, Ferré-D'Amaré AR, Burley SK (1998). "Co-crystal structure of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1a at 2.3 A resolution". Structure. 6 (5): 661–72. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00067-7. PMID 9634703.

- ^ Smith JR, Osborne TF, Goldstein JL, Brown MS (Feb 1990). "Identification of nucleotides responsible for enhancer activity of sterol regulatory element in low density lipoprotein receptor gene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (4): 2306–10. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)39976-4. PMID 2298751. S2CID 26062629.

- ^ a b Yokoyama C, Wang X, Briggs MR, Admon A, Wu J, Hua X, Goldstein JL, Brown MS (Oct 1993). "SREBP-1, a basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper protein that controls transcription of the low density lipoprotein receptor gene". Cell. 75 (1): 187–97. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80095-9. PMID 8402897. S2CID 2784016.

- ^ Wang X, Sato R, Brown MS, Hua X, Goldstein JL (Apr 1994). "SREBP-1, a membrane-bound transcription factor released by sterol-regulated proteolysis". Cell. 77 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90234-8. PMID 8156598. S2CID 44899129.

- ^ Gasic GP (Apr 1994). "Basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factor and sterol sensor in a single membrane-bound molecule". Cell. 77 (1): 17–9. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90230-5. PMID 8156593. S2CID 42988814.

- ^ a b Guo D, Bell EH, Mischel P, Chakravarti A (2014). "Targeting SREBP-1-driven lipid metabolism to treat cancer". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 20 (15): 2619–2626. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990486. PMC 4148912. PMID 23859617.

- ^ Párraga A, Bellsolell L, Ferré-D'Amaré AR, Burley SK (May 1998). "Co-crystal structure of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1a at 2.3 A resolution". Structure. 6 (5): 661–72. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00067-7. PMID 9634703.

- ^ Brown MS, Goldstein JL (May 1997). "The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor". Cell. 89 (3): 331–40. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5. PMID 9150132. S2CID 17882616.

- ^ Brown MS, Goldstein JL (Sep 1999). "A proteolytic pathway that controls the cholesterol content of membranes, cells, and blood". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (20): 11041–8. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9611041B. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.20.11041. PMC 34238. PMID 10500120.

- ^ Brown MS, Ye J, Rawson RB, Goldstein JL (Feb 2000). "Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans". Cell. 100 (4): 391–8. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80675-3. PMID 10693756. S2CID 12194770.

- ^ Espenshade PJ, Hughes AL (2007). "Regulation of sterol synthesis in eukaryotes". Annual Review of Genetics. 41 (7): 401–427. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130315. PMID 17666007. S2CID 18964672.

- ^ Fernández-Alvarez A, Alvarez MS, Gonzalez R, Cucarella C, Muntané J, Casado M (Jun 2011). "Human SREBP1c expression in liver is directly regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (24): 21466–77. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.209973. PMC 3122206. PMID 21540177.

- ^ Li S, Ogawa W, Emi A, Hayashi K, Senga Y, Nomura K, Hara K, Yu D, Kasuga M (Aug 2011). "Role of S6K1 in regulation of SREBP1c expression in the liver". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 412 (2): 197–202. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.038. PMID 21806970.

- ^ Yecies JL, Zhang HH, Menon S, Liu S, Yecies D, Lipovsky AI, Gorgun C, Kwiatkowski DJ, Hotamisligil GS, Lee CH, Manning BD (Jul 2011). "Akt stimulates hepatic SREBP1c and lipogenesis through parallel mTORC1-dependent and independent pathways". Cell Metabolism. 14 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.002. PMC 3652544. PMID 21723501.

- ^ Zhang Y, Lei T, Huang JF, Wang SB, Zhou LL, Yang ZQ, Chen XD (Aug 2011). "The link between fibroblast growth factor 21 and sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c during lipogenesis in hepatocytes". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 342 (1–2): 41–7. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2011.05.003. PMID 21664250. S2CID 24001799.

- ^ Hao Q, Hansen JB, Petersen RK, Hallenborg P, Jørgensen C, Cinti S, Larsen PJ, Steffensen KR, Wang H, Collins S, Wang J, Gustafsson JA, Madsen L, Kristiansen K (Apr 2010). "ADD1/SREBP1c activates the PGC1-alpha promoter in brown adipocytes". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1801 (4): 421–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.11.008. PMID 19962449.

- ^ Pols TW, Ottenhoff R, Vos M, Levels JH, Quax PH, Meijers JC, Pannekoek H, Groen AK, de Vries CJ (Feb 2008). "Nur77 modulates hepatic lipid metabolism through suppression of SREBP1c activity". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 366 (4): 910–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.039. PMID 18086558.

- ^ Anderson RG (Oct 2003). "Joe Goldstein and Mike Brown: from cholesterol homeostasis to new paradigms in membrane biology". Trends in Cell Biology. 13 (10): 534–9. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2003.08.007. PMID 14507481.

External links

[edit]- Sterol+Regulatory+Element+Binding+Proteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- The Brown and Goldstein Lab Archived 2009-05-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cholesterol Synthesis Archived 2017-07-04 at the Wayback Machine - has some good regulatory details

- Protein Data Base (PDB), Sterol Regulatory Element Binding 1A structure.