Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

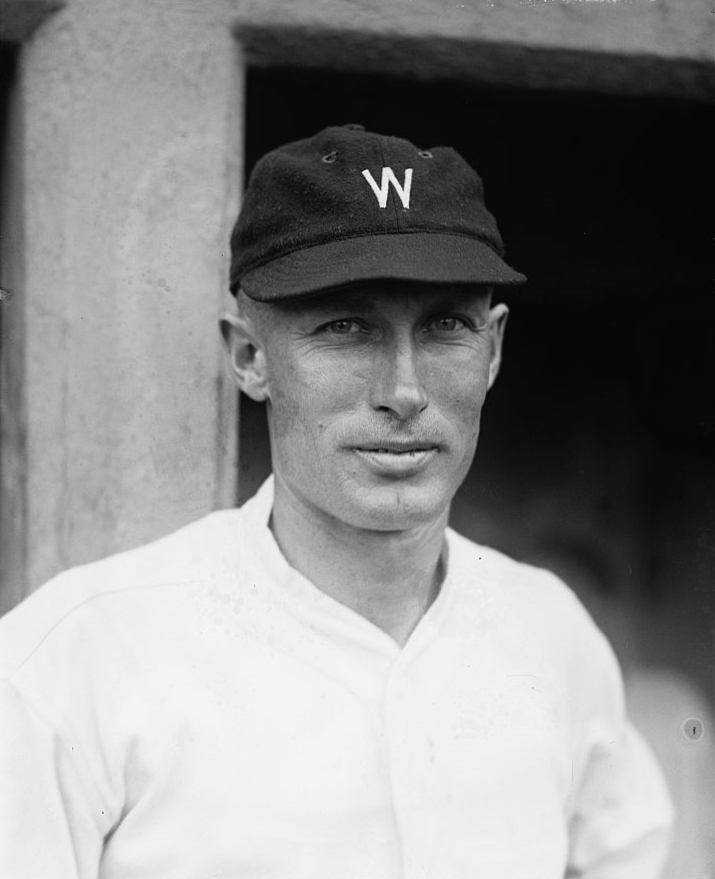

Sam Rice

View on Wikipedia

Edgar Charles "Sam" Rice (February 20, 1890 – October 13, 1974) was an American pitcher and outfielder in Major League Baseball. Although Rice made his debut as a relief pitcher, he is best known as an outfielder. Playing for the Washington Senators from 1915 until 1933, he was regularly among the American League leaders in runs scored, hits, stolen bases and batting average. He led the Senators to three postseasons and a World Series championship in 1924. He batted left-handed but threw right-handed. Rice played his final year, 1934, for the Cleveland Indians. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1963.

Key Information

Rice was best known for making a controversial catch in the 1925 World Series which carried him over the fence and into the stands. While he was alive, Rice maintained a sense of mystery around the catch, which had been ruled an out. He wrote a letter that was only opened after his 1974 death; it claimed that he had maintained possession of the ball the entire time. He collected nearly 3,000 hits in his career, with his 2,889 as a Senator being the most in franchise history.

Early life

[edit]Rice was the first of six children born to Charles Rice and Louisa Newmyer. Charles and Louisa married about two months after his birth. He grew up in various towns near Morocco, Indiana, on the Indiana-Illinois border, and considered Morocco his hometown.[1] He was known as "Eddie" during his childhood. In 1908, Rice married 16-year-old Beulah Stam.[2] They lived in Watseka, Illinois, where Rice ran the family farm, worked at several jobs in the area, and attended tryouts for various professional baseball teams.[3]

By April 1912, Rice and his wife had two children, aged 18 months and three years. While Rice's wife cared for the children, Rice traveled to Galesburg, Illinois, to play for a spot on a minor league baseball team, the Galesburg Pavers of the Central Association.[4] Rice spent about a week with the team, appearing in three exhibition games. In an appearance on April 21, Rice entered the game as a relief pitcher and finished the last three innings of a Pavers victory, giving up one run in a game marked by forceful winds.[5]

That same day, Rice's wife took their children on a day trip to the homestead of Rice's parents in Morocco, about 20 miles from Watseka. A storm arose and a tornado swept across the homestead, destroying the house and most of the outbuildings. The tornado killed Rice's wife, his two children, his mother, his two younger sisters and a farmhand. Rice's father survived for another week before also succumbing to his injuries. Rice had to attend two funerals: one for his parents and sisters, and a second for his wife and children.[6]

Rice played for the Muscatine Muskies of the Central Association in 1912, hitting .194 in 18 games. He did not play in 1913.[7]

Early baseball career

[edit]Perhaps wracked with grief, Rice spent the next year wandering the area and working at several jobs. In 1913, he joined the United States Navy and served on the USS New Hampshire, a 16,000-ton battleship that was large enough to field a baseball team. Rice played on that team during one season.[8] He was on the ship when it took part in the United States occupation of Veracruz, Mexico.[9]

In 1914, Rice joined the Petersburg Goobers of the Virginia League as a pitcher. He compiled a 9–2 record with a 1.54 earned run average (ERA) that year, then returned in 1915, earning an 11-12 record with a 1.82 ERA.[10] Petersburg team owner "Doc" Leigh owed a $300 debt to Clark Griffith, who owned the major-league Washington Senators at the time, and he offered Rice's contract to Griffith in payment of the debt. Leigh is credited with two acts which influenced Rice's subsequent career: he changed the player's name from "Edgar" to "Sam", and he convinced the Senators to let Rice play in the outfield instead of pitching.

Major league career

[edit]First MLB seasons

[edit]

Rice played 19 of his 20 seasons with the Washington Senators. He appeared in only 62 total major league games in 1915 and 1916. He played 155 games in 1917, registering a .302 batting average in 656 plate appearances.[11] Rice was recalled up to the army in 1918.[12] He joined the 68th Coast Artillery Regiment and was stationed at Fort Terry in New York. He appeared with the Senators in a few games during two furloughs.[13] By September, his company was sent to France and they prepared for combat, but the men did not see any action before the signing of the Armistice of 11 November 1918.[14]

In 1919, Rice played in 141 games and hit .321, one of 13 seasons in which he hit at least .300. He hit .338 in 1920, recorded a league-leading and career-high 63 stolen bases and was caught stealing a league-high 30 times. In 1921, he hit 13 triples, the first of ten consecutive seasons in which he finished in double digits in that category. He collected a league-high 216 hits in 1924,[15] which culminated in Rice and the Senators winning the 1924 World Series in a dramatic 7 game series against the New York Giants.[16] Though not the league leader in 1925, Rice recorded a career-high 227 hits, 87 RBI, and a .350 batting average, career highs among his full seasons.

The catch

[edit]The most famous moment in Rice's career came on defense. In Game 3 of the 1925 World Series, the Senators were leading the Pittsburgh Pirates, 4–3. In the middle of the 8th inning, Rice was moved from center field to right field. With two out in the top of the inning,[17] Pirate catcher Earl Smith drove a ball to right-center field. Rice ran the ball down and appeared to catch it at the fence, robbing Smith of a home run that would have tied the game. After the catch, Rice toppled over the fence and into the stands, disappearing from sight. When Rice reappeared, he had the ball in his glove and the umpire called Smith out. The umpire's explanation was that as soon as the catch was made the play was over, so it did not matter where Rice ended up. His team lost the Series in seven games.

Controversy persisted over whether Rice had actually caught the ball and whether he had kept possession of it. Some Pittsburgh fans sent signed and notarized documents claiming that they saw a fan pick up the ball and put it back in Rice's glove. Rice himself would not tell, answering only, "The umpire said I caught it." Magazines offered to pay him for the story, but Rice turned them down, saying, "I don't need the money. The mystery is more fun." He would not even tell his wife or his daughter. The controversy became so great that Rice wrote a letter when he was selected to the Hall of Fame, to be opened upon his death.[18] After Rice's death, a Hall of Fame official located the letter describing his World Series play and delivered it to Rice’s family. It was opened and read after his funeral. In an interview, his wife Mary said, "He did catch it. You don't have to worry about that anymore."[18] The letter concluded by stating, "At no time did I lose possession of the ball."[19]

Later career

[edit]Leading the league in hits again in 1926, Rice finished fourth in the Most Valuable Player Award voting.[11] His batting average dipped to .297 in 1927, but he hit .328, .323 and .349 from, respectively, the 1928 through 1930 seasons.[11] Though Rice hit .310 in 1931 across 120 games, Dave Harris got significant playing time when the team was facing lefthanded pitchers. The Senators also began to explore younger players for their outfield spots.[11][20]

The Senators held "Sam Rice Day" in late 1932, where the team presented him with several gifts, including a check for more than $2,200 and a new Studebaker automobile. He played only 106 games that year, often appearing as a pinch hitter. In 1933, the team returned to the World Series. Though the team lost, Rice batted once in the second game, picking up a pinch hit single.[21] The Senators released him after the season.[22]

He played in 1934 with the Cleveland Indians, then retired at the age of 44. Cleveland manager Walter Johnson talked to Rice about returning in 1935, but Rice refused.[22] Rice retired with a .322 career average. He stood erect at the plate and used quick wrists to slash pitches to all fields. He never swung at the first pitch and seldom struck out, once completing a 616-at-bat season (1929) with nine strikeouts. Rice struck out only 275 times in 9,269 at-bats, or once every 33.71 at-bats, making him the 11th all-time most difficult MLB player to strike out.[23] He recorded six 200-hit seasons in the major leagues. As the ultimate contact man with the picture-perfect swing, Rice was never a home run threat, but his speed often turned singles into doubles, and his 1920 stolen base total of 63 earned him the timely nickname "Man o' War".

With 2,987 hits, Rice has the most hits of any player not to reach 3,000. Rice later said, "The truth of the matter is I did not even know how many hits I had. A couple of years after I quit, [Senators owner] Clark Griffith told me about it, and asked me if I'd care to have a comeback with the Senators and pick up those 13 hits. But I was out of shape, and didn't want to go through all that would have been necessary to make the effort. Nowadays, with radio and television announcers spouting records every time a player comes to bat, I would have known about my hits and probably would have stayed to make 3,000 of them."[24] In postseason play, Rice produced 19 hits and a .302 batting average.[15]

Career statistics

[edit]See:Career Statistics for a complete explanation.

| G | AB | H | 2B | 3B | HR | R | RBI | BB | SO | AVG | OBP | SLG | FP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,404 | 9,269 | 2,987 | 498 | 184 | 34 | 1,514 | 1,078 | 708 | 275 | .322 | .374 | .427 | .965 |

Rice accumulated 7 five-hit games and 52 four-hit games in his career.[26] In the years that Rice played from 1915 to 1934, no major league player had more hits than Rice did.[27]

Later life

[edit]By the 1940s, Rice had become a poultry farmer. His farm was located in Olney, Maryland next to that of Harold L. Ickes, the United States Secretary of the Interior. Rice and Ickes employed several workers of Japanese descent who were displaced from the West Coast by order of the U.S. Army after the outbreak of World War II.[28]

Rice was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1963. He and three other players – John Clarkson, Elmer Flick and Eppa Rixey – were elected unanimously that year by the Hall of Fame's Veterans Committee, which considered players who had been inactive for 20 or more years. Rice said that he was glad to be inducted and said that he thought he would probably be elected if he survived long enough.[29]

Rice remarried twice, first to Edith and at age 69 to Mary Kendall Adams. Mary had two daughters by a prior marriage, Margaret and Christine.[30] In 1965, Rice and his family were interviewed in advance of a program to honor his career. The interviewer asked Rice about the tornado, and as he told of the storm and its destruction, his wife and children learned for the first time of the existence of his previous family.[31]

Rice made one of his last public appearances at the Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremonies honoring Whitey Ford and Mickey Mantle in August 1974. He died of cancer that year on October 13.[18] He was buried in Woodside Cemetery in Brinklow, Maryland.

See also

[edit]- List of Major League Baseball hit records

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career total bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual stolen base leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

Notes

[edit]- ^ Carroll, p. 9.

- ^ Carroll, pp. 9-10.

- ^ Paul Niemann, Red, White & True Mysteries, Tooele Transcript-Bulletin, 10 November 2011

- ^ Carroll, p. 11.

- ^ Carroll, pp. 11-12.

- ^ Carroll, pp. 12-15.

- ^ "Sam Rice Minor Leagues Statistics & History".

- ^ Red, White & True

- ^ "Sam Rice Biography at SABR". sabr.org. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ "Sam Rice Minor League Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Sam Rice Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ Carroll, p. 40.

- ^ Carroll, pp. 43-44.

- ^ Carroll, p. 47.

- ^ a b "Sam Rice Stats".

- ^ "1924 World Series".

- ^ "1925 World Series Game 3, Pittsburgh Pirates at Washington Senators, October 10, 1925".

- ^ a b c "Baseball Hall of Famer Sam Rice is dead at 84". Bangor Daily News. October 15, 1974. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ "Rice claims he never lost ball". Ellensburg Daily Record. November 5, 1974. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ Vosburgh, Ted (August 17, 1931). "Johnson leads in tribute to A's great club". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ "1933 World Series Game 2, Washington Senators at New York Giants, October 4, 1933".

- ^ a b Fleitz, David L. (April 3, 2007). More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown. McFarland. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7864-8062-3. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ "All-Time At-Bats Per Strikeout Rankings From Baseball Reference". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ The 3,000 Hit Club. Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ Sam Rice Stats at baseball-almanac.com

- ^ "Sam Rice Top Performances At Retrosheet". retrosheet.org. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ "For combined seasons, from 1915 to 1934, in the regular season, sorted by descending Hits". Stathead. Retrieved July 16, 2025.

- ^ Eads, Jane (January 31, 1945). "200 Japanese-Americans work in important government jobs". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved December 21, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Rixey, Sam Rice in Baseball Hall of Fame". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 28, 1963. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ Sports Illustrated, August 23, 1993, Letters- Margaret Adams Robinson. [1]

- ^ "There is one thing about Edgar 'Sam' Rice that no one could dispute: He sure could keep a secret." Red, White & True

References

[edit]- Carroll, Jeff (2007). Sam Rice: A Biography of the Washington Senators Hall of Famer. ISBN 0786431199. McFarland.

External links

[edit]- Sam Rice at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference · Baseball Reference (Minors) · Retrosheet · Baseball Almanac

- Sam Rice at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Sam Rice at Find a Grave

Sam Rice

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Upbringing

Edgar Charles Rice, professionally known as Sam Rice, was born on February 20, 1890, in the small rural town of Morocco, Newton County, Indiana, to parents Charles Rice and Louisa Newmyer Rice, both of whom worked as farmers.[2][4] As the eldest of six children, Rice grew up in an agrarian household that soon relocated across the state line to a farm near Donovan in Iroquois County, Illinois, where the family continued their farming life.[2] His childhood involved typical rural labors, with limited formal education confined to the one-room Rhode Island Country School, after which he contributed as a farmhand to support the family.[2] At age 18, Rice married Beulah Stam on September 17, 1908, and the couple moved to nearby Watseka, Illinois, where they started a family.[2] Their first child, daughter Berniece "Bernie" Rice, was born in 1909, followed by a second daughter, Adelma Ethel Rice, in 1910.[2][5] Rice's early interest in baseball developed through informal sandlot games in the Watseka area, where he played with local amateur teams like the Watseka Pastimes, honing his skills as an outfielder and pitcher before considering more structured play.[2]Family Tragedy

On April 21, 1912, a violent F4 tornado tore through the rural community near Donovan, Illinois, devastating the Rice family farmhouse and claiming the lives of Sam Rice's wife, Beulah Stam Rice, their three-year-old daughter Bernie, and 18-month-old daughter Ethel, along with his mother and two sisters (Bernadine and Genevieve).[2][6] The storm, part of a larger outbreak that killed dozens across the Midwest, reduced the home to rubble and scattered debris over a wide area, with property damage exceeding $1 million in 1912 dollars.[2] At the time, the 22-year-old Rice was away in Galesburg, Illinois, participating in a semi-professional baseball game, leaving his family vulnerable to the sudden catastrophe.[2] Notified by telegraph the following day, Rice rushed home to confront the horror of the destruction, where he discovered the bodies of his wife and children amid the wreckage, an experience that plunged him into overwhelming grief.[2] He arranged and attended double funerals on April 23 and 24 for his immediate family and extended relatives, while tending to his severely injured father, who died from complications a week later on April 30.[2] In the immediate aftermath, Rice temporarily withdrew from social interactions and baseball, exhibiting signs of deep emotional distress through aimless wandering and withdrawal from his community near Donovan, Illinois.[2][7] The tragedy's long-term effects haunted Rice with profound sorrow and a persistent sense of guilt for his absence during the storm, reshaping his early adulthood into a period of isolation and reflection.[7] This personal loss ultimately channeled his energies into baseball as a means of escape from the pain and a silent tribute to his family, intensifying his dedication to the sport in the years that followed.[7] The full extent of the event remained largely unknown to the public during Rice's playing career, only surfacing through local historical research in the 1980s, including a 1984 article by John Yost in the Newton County Enterprise and subsequent national coverage.[2] This delayed his entry into minor league baseball until 1915.[2]Early Baseball Career

Minor League Beginnings

Following the family tragedy in April 1912, Sam Rice demonstrated remarkable resilience by continuing his nascent professional baseball career in the minor leagues. He had begun the season with a tryout for the Galesburg Pavers of the Class D Central Association, where he pitched in four exhibition games, including a three-inning stint against the Monmouth Browns in which he allowed one run on one hit while striking out four.[2] Shortly after the tornado, however, he was released by Galesburg and signed with the Muscatine Wallopers, also of the Central Association, appearing in 18 games primarily as a second baseman and batting .194 with 12 hits in 62 at-bats.[8] This limited success underscored the emotional and professional hurdles Rice faced, fueling his determination to persist despite profound personal loss.[2] Seeking financial stability amid inconsistent minor league earnings, Rice enlisted in the U.S. Navy in early 1913 and did not play organized baseball that year while serving aboard the USS New Hampshire.[2] In mid-1914, while on furlough, he signed with the Petersburg Goobers of the Class C Virginia League, where he established himself more firmly as a pitcher. His discharge from the Navy was arranged later that year, allowing him to join full-time.[2] In 15 appearances for Petersburg, Rice compiled a strong 9-2 record, the best winning percentage in the league, while logging 123 innings pitched, allowing 73 hits and 38 walks, and striking out 62 batters for a WHIP of 0.902 and a runs-allowed average of 2.12.[8] He also contributed offensively, batting .310 with 22 hits in 71 at-bats across 31 games.[8] These performances marked a key step in refining his pitching fundamentals and gaining notice from scouts, though the rigors of low-level minors continued to test his resolve for reliable livelihood.[2]Military Service and Professional Entry

In 1913, at the age of 23, Edgar Charles "Sam" Rice enlisted in the United States Navy in Norfolk, Virginia.[2] Assigned as a fireman aboard the battleship USS New Hampshire, Rice served for approximately 18 months, during which the vessel was involved in routine patrols and training exercises along the East Coast.[2] His enlistment provided stability following a period of personal hardship and transient work, marking a pivotal chapter that would soon intersect with his emerging athletic talents.[2] Rice's service took a dramatic turn in April 1914 when the USS New Hampshire participated in the United States occupation of Veracruz, Mexico, amid escalating tensions with Mexican forces under Victoriano Huerta.[2] On April 22, Rice landed with a contingent of sailors, engaging in combat operations against entrenched positions; he later recalled bullets "humming around" him and striking nearby, highlighting the intensity of the brief but hazardous intervention.[2] Throughout his naval tenure, Rice played baseball for the ship's team, competing in exhibition games at ports including Norfolk, Guantanamo Bay, and other U.S. naval bases, where his pitching prowess drew attention from local baseball enthusiasts and scouts.[2] These contests, often against civilian or rival naval squads like the USS Louisiana and Columbia University, served as informal showcases that amplified his visibility beyond military duties.[2] In mid-1914, while on furlough, Rice pitched for the Petersburg Goobers of the Class C Virginia League, impressing team owner John H. Leary with his skill.[4] With advocacy from influential Virginia politicians known as the "Virginia Senators," Leary secured Rice's honorable discharge from the Navy later that year by purchasing his remaining enlistment for $800.[2] This arrangement allowed Rice to sign immediately with the Goobers as a full-time professional, bridging his military experience to organized baseball; the team had loose ties to the Washington Senators franchise, facilitating his rapid ascent to the major leagues in July 1915.[2] The structured environment of naval life, where Rice was regarded as a "splendid soldier—loyal, smart," fostered the discipline and reliability that underpinned his professional work ethic.[9]Major League Career

Debut and Positional Shift

Sam Rice made his Major League Baseball debut on August 7, 1915, with the Washington Senators as a 25-year-old pitcher, entering in relief during a 6-2 loss to the Chicago White Sox and allowing one unearned run over 1⅔ innings.[2] He appeared in four games that season, all as a pitcher, compiling a 1-0 record with a 2.00 ERA over 18 innings pitched, though his overall performance was limited by inexperience at the major league level.[3] This brief stint followed his minor league background as a pitcher, where he had shown promise but struggled to secure a consistent role.[2] In 1916, Rice continued pitching initially, making five appearances with a 0-1 record and a 2.95 ERA in 21⅓ innings, but his effectiveness waned due to a shoulder injury and broader team needs.[2] Under manager and owner Clark Griffith, Rice transitioned to the outfield midway through the season, starting as a right fielder on July 17, a move driven by his strong throwing arm, speed, and demonstrated hitting ability, which Griffith envisioned addressing the Senators' offensive shortcomings.[2] He played 46 games in the outfield that year (primarily right field), marking the beginning of his shift away from pitching entirely after just nine total major league mound appearances.[3] As a new outfielder, Rice showed early promise at the plate, batting .299 with 59 hits in 197 at-bats across 59 games, including 8 doubles, 3 triples, and 1 home run.[10] However, the adjustment brought challenges, including a period where he hit below .200 from late July to mid-August amid malaria-like symptoms and a three-week absence due to fever, testing his adaptability to defensive positioning and the demands of regular outfield play.[2] Griffith's foresight proved correct, as Rice's transition laid the foundation for his emergence as a full-time hitter, with his speed and arm strength quickly proving assets in right field.[1]Peak Performance Years

Sam Rice's peak performance years unfolded in the 1920s with the Washington Senators, following his early positional shift from pitching to outfield that allowed him to thrive as a full-time player. During this period, he became a model of hitting consistency, posting batting averages above .300 in four of the five seasons from 1920 to 1924, with 211 hits in 1920 at .338 and a league-leading 216 hits in 1924 at .334.[3] His plate discipline and line-drive swing enabled him to compile 987 hits over those years, averaging nearly 200 per season while maintaining a low strikeout rate that underscored his contact-oriented approach.[2] In 1925, Rice elevated his game to new heights, batting .350 with 227 hits—both career bests—and driving in 87 runs to anchor the Senators' lineup.[3][1] Defensively, Rice distinguished himself in the outfield, primarily right field by the mid-1920s, where his accurate throwing arm made him a standout. He led American League outfielders in assists once during the decade and ranked among the league leaders multiple times, including 21 assists in 1923 that helped thwart opposing runners.[1][3] Earlier in the 1920s, while playing center field, Rice set an AL single-season record with 454 putouts in 1920, demonstrating his range and reliability in patrolling vast territory.[1] His fielding prowess complemented his batting, earning him a reputation as a complete player who minimized errors—committing just 13 in 1923 across 147 games—and contributed to the Senators' improved outfield stability.[3] Rice's contributions were instrumental to the Senators' rise, particularly through clutch hitting in tight pennant races that propelled the team to American League titles in 1924 and 1925. In 1924, his 106 runs scored and timely extra-base hits—39 doubles and 14 triples—provided the offensive spark needed for Washington to overtake the New York Yankees for the pennant.[2][1] The following year, Rice's league-high 227 hits and consistent production in high-pressure situations helped the Senators repeat as champions, showcasing his ability to perform when the stakes were highest.[3][1] Off the field, Rice's disciplined lifestyle during these peak years emphasized focused training regimens and abstention from nightlife distractions, habits that preserved his stamina for playing 141 to 154 games annually from 1919 to 1923.[2] He cultivated deep team camaraderie, especially with pitcher Walter Johnson, whose mentorship and shared work ethic strengthened the Senators' cohesion and mirrored Rice's own dedication to the game.[2]World Series Participation

Sam Rice participated in three World Series with the Washington Senators, showcasing his versatility and reliability in postseason play despite varying team outcomes. In the 1924 World Series against the New York Giants, which the Senators won in seven games for their first championship, Rice batted .207 with six hits in 29 at-bats across all seven games.[11] His defensive contributions proved pivotal, particularly in Game 7, where his outfield plays helped maintain a narrow 2-1 lead entering the ninth inning before Walter Johnson's relief appearance sealed the victory.[12] The following year, in the 1925 World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates, the Senators fell in another seven-game series. Rice delivered a standout offensive performance, hitting .364 with 12 hits in 33 at-bats, including five runs scored and three RBIs, while providing strong defensive support in center field.[13] His speed on the basepaths added pressure to Pirate defenses, complementing his consistent contact hitting during the high-stakes matchup.[1] By the 1933 World Series against the Giants, at age 43, Rice's role had diminished amid the Senators' 4-1 defeat. Appearing in only one game, he recorded a pinch-hit single in his sole at-bat during Game 2, going 1-for-1 for a perfect 1.000 average in limited action.[14] Throughout his postseason career, spanning 15 games, Rice maintained a .302 batting average with 19 hits, four RBIs, and seven runs scored, often leveraging his renowned speed—evident in 184 career stolen bases—and sure-handed fielding to impact games beyond the box score.[15][16]The Famous Catch Controversy

In Game 3 of the 1925 World Series on October 10, between the Washington Senators and Pittsburgh Pirates at Griffith Stadium, right fielder Sam Rice made a spectacular diving catch in the eighth inning that preserved a 4-3 victory for the Senators.[17] With a runner on first and the Pirates trailing by one, catcher Earl Smith hit a deep line drive toward the temporary stands in right field; Rice raced back, leaped, backhanded the ball, and tumbled headfirst over the low railing into the front row of spectators, disappearing from view for several seconds before emerging with the ball in his glove.[18] Umpire Cy Rigler ruled it a catch after Rice showed him the ball, robbing Smith of extra bases and thwarting a potential Pirates rally in what would become a pivotal moment in the closely contested series, which the Pirates ultimately won in seven games.[17] The play ignited immediate and intense controversy among the Pirates' bench, players, and fans, who protested vehemently that the ball had either hit the ground or popped out of Rice's glove during his fall into the stands.[19] Pirates manager Bill McKechnie argued the call with Rigler and the other umpires, insisting it should have been ruled a ground-rule double or home run, but the decision stood, fueling post-game disputes that even prompted some eyewitness fans to later submit affidavits to baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis claiming the catch was invalid.[18] Despite the uproar, Rice remained stoic on the field, simply handing the ball to the umpire without elaboration, and the Senators held on to win the game, giving the Senators a 2-1 lead in the series.[17] Throughout his life, Rice steadfastly refused to discuss the details of the catch, deflecting questions with the curt response, "The umpire called it a catch," which only heightened the mystery surrounding one of baseball's most debated plays.[19] In 1965, weary of persistent inquiries, he wrote a sealed letter to the National Baseball Hall of Fame instructing that it be opened only after his death, promising to reveal the truth.[20] Following Rice's death on October 13, 1974, the letter was opened on November 6, 1974, in Cooperstown, where it confirmed the catch's legitimacy: Rice described securing the ball in the webbing of his glove with a "death grip," stating that it never touched the ground or any spectators and that he maintained possession throughout the tumble.[20] This posthumous clarification finally resolved the 49-year-old debate, affirming Rice's defensive prowess in a moment that had long symbolized the drama and uncertainty of World Series play.[21]Career Statistics and Achievements

Batting and Fielding Records

Sam Rice compiled an impressive 20-year career in Major League Baseball from 1915 to 1934, primarily with the Washington Senators, amassing 2,987 hits while batting .322, driving in 1,077 runs, stealing 351 bases, and appearing in 2,404 games.[3] These totals reflect his consistency as a contact hitter during the transition from the dead-ball era to the live-ball era, where he adapted effectively to maintain a high batting average despite changing pitching and equipment dynamics.[22] His career also included 498 doubles, placing him 68th all-time in that category.[23] Rice achieved several seasonal peaks that underscored his offensive prowess, including a career-high 227 hits in 1925 (second in the AL) and a .350 batting average that same year.[3] He recorded six 200-hit seasons—1920, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1928, and 1930—highlighting his ability to accumulate base knocks over extended stretches. For context, his 2,987 hits rank 34th in MLB history, a testament to his longevity and reliability at the plate.[24] Defensively, Rice excelled as a right fielder, recording 2,420 putouts in that position with a .983 fielding percentage, contributing to his overall outfield totals of 4,774 putouts, 278 assists, 184 errors, and a .970 fielding percentage.[3] He led the American League in outfield assists twice, with 23 in 1922 (as a center fielder) and 25 in 1926, while also topping the league in outfield games played in 1917, 1919, 1928, and 1929. This defensive reliability complemented his batting, allowing him to accumulate statistics across multiple roles early in his career before settling into right field.[22]| Category | Career Total | Notable Ranking/High |

|---|---|---|

| Hits | 2,987 | 34th all-time; 227 in 1925 (2nd in AL) |

| Batting Average | .322 | .350 in 1925 (career high) |

| Doubles | 498 | 68th all-time |

| RBI | 1,077 | - |

| Stolen Bases | 351 | - |

| Games Played | 2,404 | - |

| Outfield Putouts | 4,774 | - |

| Outfield Assists | 278 | AL lead in 1922, 1926 |

| Fielding Percentage (OF) | .970 | .983 as RF |