Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

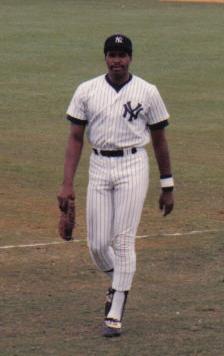

Dave Winfield

View on Wikipedia

David Mark Winfield (born October 3, 1951) is an American former Major League Baseball (MLB) right fielder. He is the special assistant to the executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association.[1] Over his 22-year career, he played for six teams: the San Diego Padres, New York Yankees, California Angels, Toronto Blue Jays, Minnesota Twins, and Cleveland Indians. He had the winning hit in the 1992 World Series with the Blue Jays over the Atlanta Braves.

Key Information

Winfield is a 12-time MLB All-Star, a seven-time Gold Glove Award winner, and a six-time Silver Slugger Award winner. The Padres retired Winfield's No. 31 in his honor. He also wore No. 31 while playing for the Yankees and Indians and wore No. 32 with the Angels, Blue Jays and Twins. In 2004, ESPN named him the third-best all-around athlete of all time in any sport.[2] He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001 in his first year of eligibility, and was an inaugural inductee into the College Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Early life

[edit]David Mark Winfield was born on October 3, 1951, in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and grew up in the city's Rondo neighborhood.[3][4] His parents divorced when he was three years old, leaving him and his older brother Stephen to be raised by their mother, Arline, and a large extended family of aunts, uncles, grandparents, and cousins.[5] The Winfield brothers honed their athletic skills in Saint Paul's Oxford Field, where coach Bill Peterson was one of the first to notice Winfield. Winfield did not reach his full height of 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) until his senior year at Saint Paul Central High School.[5]

College career

[edit]Winfield earned a full baseball scholarship to the University of Minnesota in 1969, where he starred in baseball and basketball for the Minnesota Golden Gophers. Winfield's 1971–72 Minnesota team won a Big Ten Conference basketball championship, the school's first outright championship in 53 years. During the 1972–73 basketball season, he was involved in a brawl when Ohio State played at Minnesota.[6][7] Winfield also played college summer baseball for the Alaska Goldpanners of Fairbanks for two seasons (1971–72) and was the MVP in 1972. In 1973, he was named All-American and voted MVP of the College World Series—as a pitcher.

Following college, Winfield was drafted by four teams in three different sports. The San Diego Padres selected him as a pitcher with the fourth overall pick in the MLB draft. Winfield was also drafted by the Atlanta Hawks in the 5th round of the 1973 NBA draft and by the Utah Stars in the 6th round of the 1973 ABA Draft.[8][9] Though he never played college football, the Minnesota Vikings selected Winfield in the 17th round of the 1973 NFL draft. He is one of five players ever to be drafted by three professional sports (the others being George Carter, Noel Jenke, Mickey McCarty and Dave Logan) and one of three athletes, along with Carter and McCarty, to be drafted by four leagues.[10]

Professional career

[edit]Draft and San Diego Padres (1973–1980)

[edit]

Winfield chose baseball; the San Diego Padres selected him in the first round, with the fourth overall selection, of the 1973 MLB draft. Winfield signed with the Padres, who promoted him directly to the major leagues. Although he was a pitcher, the Padres wanted his powerful bat in the lineup and put him in right field, where he could still use his powerful arm. He batted .277 in 56 games for his first season.

The next three seasons saw gradual improvement: he had his first 20-HR season in 1974 while batting .265 in 145 games that had him play mostly in left field. The following year saw him shifted to right field, where he would play most of the next six seasons. By the time of his fourth season being over, his best average in the majors was .283 (1976). Over the next several years, he developed into an All-Star player in San Diego, gradually increasing his ability to hit for both power and average. In 1977, he had his first All-Star season, doing so while batting .275 in 157 games with 25 home runs. He would be an All-Star every year until 1988. In 1978, he was named team captain. That year, he finished 10th in MVP voting and had his first .300 season with a .308 year in 158 games. He had his first 100-RBI season the following year while batting .308 with a league-leading 118 RBIs to go with 24 intentional walks; he had his first season with more walks (85) than strikeouts (71). He won a Gold Glove and finished 3rd in the MVP voting. In his final season with the Padres in 1980, he played in all 162 games for the only time and batted .276 to go with 20 home runs and a Gold Glove victory.

New York Yankees (1981–1990)

[edit]In December 1980, New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner made Winfield the game's highest-paid player by signing him to a ten-year, $23 million contract (equivalent to $87.8 million in 2024). Steinbrenner mistakenly thought he was signing Winfield for $16 million, unaware of the meaning of a cost-of-living clause in the contract,[11] a misunderstanding that led to an infamous public feud.[12] The $2.3 million annual average value of the contract set a record. He more than doubled the previous record set when Nolan Ryan signed with the Houston Astros in 1979.

Winfield was among the highest-rated players in the game throughout his Yankee contract. He was a key factor in leading the Yankees to the 1981 American League pennant. In the 1981 American League Division Series, Winfield batted .350 with two doubles and a triple and made some important defensive plays helping the Yankees to victory over the Milwaukee Brewers. Unfortunately, Winfield had a sub-par World Series, which the Yankees lost to the Los Angeles Dodgers in six games. After getting his only series hit, Winfield jokingly asked for the ball.[13] Steinbrenner did not find this humorous, and criticized Winfield at the end of the series. Many commentators have since noted that Winfield's postseason doldrums were somewhat overstated when compared to those of his teammates. Four of his seven hits came in games won by the Yankees. The team's offense for the most part was inconsistent, and they were also set back by key injuries to Reggie Jackson and Graig Nettles, who each only played three games with one combined RBI (the same as Winfield).

Winfield did not let Steinbrenner's comments affect his play. He hit 37 home runs during the 1982 season.

On August 4, 1983, Winfield killed a seagull by throwing a ball while warming up before the fifth inning of a game at Toronto's Exhibition Stadium.[14] Fans responded by hurling obscenities and objects onto the field. After the game, he was brought to a nearby Metropolitan Toronto Police station and charged with cruelty to animals. He was released after posting a $500 bond. Yankee manager Billy Martin quipped, "It's the first time he's hit the cutoff man all season."[14] Charges were dropped the following day.[15] As Winfield missed the Yankees team bus to Hamilton that night to catch their flight home, he was driven to Hamilton personally by Blue Jays general manager Pat Gillick.[14] In the offseason, Winfield returned to Toronto and donated two paintings for an Easter Seals auction, which raised over $60,000.[5][16] For years afterward, Winfield's appearances in Toronto were greeted by fans standing and flapping their arms.

From 1981 through 1984, Winfield was the most effective run producer in MLB.[17] In 1984, he and teammate Don Mattingly were in a race for the batting title[18] in which Mattingly won out by .003 points on the last day of the season; Winfield finished with a .340 average. In the last few weeks of the race, it became obvious to most observers that the fans were partial to Mattingly.[19] Winfield took this in stride, noting that a similar thing happened in 1961 when Mantle and Maris competed for the single season home run record.[20]

In 1985, Steinbrenner derided Winfield by saying to The New York Times writer Murray Chass, "Where is Reggie Jackson? We need a Mr. October or a Mr. September. Winfield is Mr. May."[21] This criticism has become somewhat of an anachronism as many cite the statement to Steinbrenner after the 1981 World Series. Winfield was struggling while the Yankees eventually lost the division title to Toronto on the second to last day of the season.[21] The "Mr. May" sobriquet lived with Winfield until he won the 1992 World Series with Toronto.[22]

Throughout the late 1980s, Steinbrenner regularly leaked derogatory and fictitious stories about Winfield to the press.[23] He also forced Yankee managers to move him down in the batting order and bench him. Steinbrenner frequently tried to trade him, but Winfield's status as a 10-and-5 player (10 years in the majors, five years with a single team) meant he could not be traded without his consent. Winfield continued to put up excellent numbers with the Yankees, driving in 744 runs between 1982 and 1988, and was selected to play in the All-Star Game every season. Winfield won five (of his seven) Gold Glove Awards for his stellar outfield play as a Yankee.

In 1989, Winfield missed the entire season due to a back injury.[24] 1990 was the last year of his contract with the Yankees, but the troubles with Steinbrenner in his feud with Winfield continued to escalate. He had a rusty spring training before being relegated from the field to being the designated hitter. Further troubles led to being just the DH against left-handed pitchers. On May 11, manager Bucky Dent and general manager Pete Peterson met in a room with the intent of stating a trade of Winfield for Mike Witt of the California Angels. Winfield stepped in the room and stated his refusal to be traded; the argument over whether his 10-and-5 rights overrode his list of having the Angels on his trade list failed to meet at an impasse when Angels owner Gene Autry came in with a three-year extension. He proceeded to hit 19 home runs in 112 games for the Angels in the remainder of the 1990 season. As for Steinbrenner, he attempted to curry favor by stating to Winfield that he would welcome back Winfield openly if he had won the arbitration case; by this point in the month of May, he was already under investigation by commissioner Fay Vincent for his apparent connections to Howard Spira, a known gambler with supposed Mafia connections, whom he had paid $40,000 for embarrassing information on Winfield. A month later, the team received a fine that required them to pay money to the league and the Angels for tampering and Steinbrenner soon received a life-time ban.[25] However, the suspension lasted only two years.[24]

California Angels (1990–1991)

[edit]Winfield was traded for Mike Witt during the 1990 season and won The Sporting News Comeback Player of the Year Award.[26] He hit for the cycle in June 1991 against the Kansas City Royals, hitting 5-for-5 in the game.[27] He also recorded his 400th home run against the Twins in his hometown.[28]

Toronto Blue Jays (1992)

[edit]Winfield was still a productive hitter after his 40th birthday. On December 19, 1991, he signed with the Toronto Blue Jays as their designated hitter, and also made "Winfieldian" plays when he periodically took his familiar position in right field. He batted .290 with 26 home runs and 108 RBI during the 1992 season.

Winfield proved to be a lightning rod for the Blue Jays, providing leadership and experience as well as his potent bat. Winfield was a fan favorite and also demanded fan participation. In August 1992, he made an impassioned plea to the reserved fans during an interview for more crowd noise. The phrase "Winfield Wants Noise" became a popular slogan for the rest of the season, appearing on T-shirts, dolls, buttons, and signs.

The Blue Jays won the pennant, giving Winfield a chance at redemption for his previous post-season futility. In Game 6 of the World Series, he became "Mr. Jay"[22] as he delivered the game-winning two-run double in the 11th inning off Atlanta's Charlie Leibrandt to win the World Series Championship for Toronto. At 41 years of age, Winfield became the third-oldest player to hit an extra base hit in the World Series, trailing only Pete Rose and Enos Slaughter.[29]

Minnesota Twins (1993–1994)

[edit]After the 1992 season, Winfield was granted free agency and signed with his hometown Minnesota Twins. In 1993, he batted .271 with 21 home runs, appearing in 143 games for the 1993 Twins, mostly as their designated hitter. On September 16, 1993, at age 41, he collected his 3,000th career hit with a single off Oakland Athletics closer Dennis Eckersley.[30]

During the 1994 baseball strike, which began on August 12, Winfield was traded to the Cleveland Indians at the trade waiver deadline on August 31 for a player to be named later. The 1994 season had been halted two weeks earlier (it was eventually canceled a month later on September 14), so Winfield did not get to play for the Indians that year and no player was ever named in exchange. To settle the trade, Cleveland and Minnesota executives went to dinner, with the Indians picking up the tab. This makes Winfield the only player in major league history to be "traded" for a dinner (although official sources list the transaction as Winfield having been sold by the Twins to the Indians).[31]

Cleveland Indians (1995)

[edit]Winfield, who was the oldest player in MLB at the time, was again granted free agency in October but re-signed with the Indians as spring training began in April 1995. A rotator cuff injury kept him on the disabled list for most of the season, thus he played in only 46 games and hit .191 for Cleveland's first pennant winner in 41 years. He did not participate in the Indians' postseason.

Honors and awards

[edit]

Winfield retired in 1996 and, in his first year of eligibility, was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001 as a San Diego Padre, the first Padre to be so honored. The move reportedly irked Yankees' owner George Steinbrenner, however Winfield sounded a conciliatory note toward him, saying, "He's said he regrets a lot of things that happened. We're fine now. Things have changed."[32][33]

In 1998, Winfield was inducted by the San Diego Hall of Champions into the Breitbard Hall of Fame, honoring San Diego's finest athletes both on and off the playing surface.[34]

In 1999, Winfield ranked number 94 on The Sporting News list of Baseball's Greatest Players,[35] and was a nominee for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

He was inducted into the San Diego Padres Hall of Fame in 2000.[36] The Padres retired Winfield's No. 31 on April 14, 2001.[37]

On July 4, 2006, Winfield was inducted into the College Baseball Hall of Fame in its inaugural class.

In 2010, Winfield was selected as one of 28 members of the NCAA Men's College World Series Legends Team.[38]

The Big Ten Network named Winfield its #15 ranked Big Ten Conference "Icon" in 2010.[39]

The 2016 MLB All-Star Game, played at Petco Park in San Diego, was dedicated to Winfield. He had represented the Padres at the first All-Star Game to be played in San Diego.

On June 21, 2024, Winfield returned to Fairbanks for the unveiling of a bronze statue near Growden Park, where he had played for the Alaska Goldpanners of Fairbanks. Winfield also threw out the ceremonial first pitch for the annual Midnight Sun Game.[40]

Post-playing career and appearances

[edit]In 1996, Winfield joined the new Major League Baseball on Fox program as studio analyst for their Saturday MLB coverage.

From 2001 to 2013, Winfield served as executive vice president/senior advisor of the San Diego Padres.

In 2006, Winfield teamed up with conductor Bob Thompson to create The Baseball Music Project, a series of concerts that celebrate the history of baseball, with Winfield serving as host and narrator.[41]

In 2008, Winfield participated in both the final Old Timers' Day ceremony and final game ceremony at Yankee Stadium.[42]

On June 5, 2008, Major League Baseball held a special draft of the surviving Negro league players to acknowledge and rectify their exclusion from the major leagues on the basis of race. The idea of the special draft was conceived by Winfield. Each major league team drafted one player from the Negro leagues.[43]

On March 31, 2009, Winfield joined ESPN as an analyst on their Baseball Tonight program.[44]

On December 5, 2013, Winfield was named special assistant to Executive Director Tony Clark at the Major League Baseball Players Association.[45]

On July 14, 2014, Winfield returned to Minnesota to throw out the first pitch at the 2014 Home Run Derby along with fellow St. Paul natives Joe Mauer, Paul Molitor, and Jack Morris.[46]

In March 2016, Winfield helped represent Major League Baseball in Cuba during President Obama's trip to the island in an attempt to help normalize relations. On March 21 he gave a press conference with Joe Torre, Derek Jeter, and Luis Tiant in Havana and attended the baseball game between the Tampa Bay Rays and the Cuba National Team the next day.

In July 2022, Winfield delivered Bud Fowler's Hall of Fame speech in Cooperstown.[47]

In popular media

[edit]On Thanksgiving Day 1981, Winfield sang "I'll Take Manhattan" atop the Big Apple Float at the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade.[48]

In 1985, the video game Dave Winfield's Batter Up! was released on computers by Avant-Garde, a producer of interactive educational software.[49] The game featured a 55-page manual co-authored by Winfield[50] and was marketed as an educational tool aimed to teach players about batting. The game was conceived after Winfield was seated next to an Avant-Garde investor on a cross-country flight.[49]

During the 1994–95 MLB strike, Winfield and a handful of other striking players appeared as themselves in the November 27, 1994, episode of Married With Children (Season 9, Episode 11).[51]

In 1995, he made a guest appearance in season 1, episode 10 of The Drew Carey Show.

Activism

[edit]Philanthropy

[edit]Well known for his philanthropic work, Winfield was the first active athlete to create a philanthropic foundation, The David M. Winfield Foundation.[52] He began giving back to the communities in which he played from 1973, his first year with the Padres, when he began buying blocks of tickets to Padres games for families who could not afford to go to games, in a program known as "pavilions." Winfield then added health clinics to the equation, by partnering with San Diego's Scripps Clinic who had a mobile clinic which was brought into the stadium parking lot.[53] When Winfield joined the Toronto Blue Jays, he learned teammate David Wells was one of the "Winfield kids" who attended Padres games.[54]

In his hometown of St. Paul, he began a scholarship program (which continues to this day). In 1977, he organized his efforts into an official 501(c)(3) charitable organization known as the David M. Winfield Foundation for Underprivileged Youth.[53] As his salary increased, Foundation programs expanded to include holiday dinner giveaways and national scholarships. In 1978, San Diego hosted the All-Star game, and Winfield bought his usual block of pavilion tickets. Winfield then went on a local radio station and inadvertently invited "all the kids of San Diego" to attend. To accommodate the unexpected crowd, the Foundation brought the kids into batting practice. The All-Star open-practice has since been adopted by Major League Baseball and continues to this day.[5]

When Winfield joined the New York Yankees, he set aside $3 million of his contracted salary for the Winfield Foundation. The foundation created a partnership with the Hackensack University Medical Center[55] including founding The Dave Winfield Nutrition Center,[56] near his Teaneck, New Jersey, home. The Foundation also partnered with Merck Pharmaceuticals and created an internationally acclaimed bilingual substance abuse prevention program called "Turn it Around".[54]

The Winfield Foundation also became a bone of contention in Steinbrenner's public feud with Winfield. Steinbrenner alleged that the foundation was mishandling funds and often held back payments to the organization, which resulted in long, costly court battles. It also created the appearance that Steinbrenner was contributing to the foundation, when in actuality, Steinbrenner was holding back a portion of Winfield's salary. Ultimately, the foundation received all of its funding and the alleged improprieties proved unfounded.

Winfield's philanthropic endeavors had as much influence on many of MLB's players as his on-field play. Yankee Derek Jeter, who grew up idolizing Winfield for both his athleticism and humanitarianism, credits Winfield as the inspiration for his own Turn 2 Foundation.[57] In turn, Winfield continues to help raise funds and awareness for Jeter's Foundation and for many other groups and causes throughout the country.

Quotes

[edit]- Now it's on to May, and you know about me and May.[22] —after setting an American League record for RBI in April 1988.

- I am truly sorry that a fowl of Canada is no longer with us.[22] —to the press after being released following the 1983 bird-killing incident.

- These days baseball is different. You come to spring training, you get your legs ready, your arms loose, your agents ready, your lawyer lined up.[58]—at spring training, 1988, in response to his on-going feud with Steinbrenner.

- I have no problem with Bruce Springsteen.—when asked by the New York Daily News why he has such a problematic relationship with "the Boss" (a nickname shared by both Springsteen and Steinbrenner).

- "Three-ninety-nine sounds like something you'd purchase at a discount store. Four hundred sounds so much better.[28]—upon hitting his 400th home run after 10 days mired at 399.

See also

[edit]- 3,000 hit club

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball home run records

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball retired numbers

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of baseball players who went directly to Major League Baseball

- List of athletes on Wheaties boxes

- List of multi-sport athletes

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "David Winfield joins MLBPA as special assistant to Clark". ESPN. December 5, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Merron, Jeff (April 26, 2004). "The best all-around athletes". ESPN. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ Melo, Frederick (November 7, 2015). "St. Paul: Signs to mark former Rondo Avenue proposed". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Larry (May 16, 2012). "It all started with Dave Winfield". Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Winfield: A Player's Life autobiography

- ^ Oller, Rob (January 25, 2007). "Brawl of 35 years ago serves as a warning today". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

{{cite web}}:|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Oller, Rob (January 23, 2022). "Violence erupted 50 years ago when Ohio State played Minnesota in basketball". Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Jet, February 2001, Vol. 99, No. 8, p.46

- ^ Baseball Digest, August 1975, Vol. 34, No. 8, p.56-57

- ^ "The Alaska Goldpanners of Fairbanks Baseball Club – "Home of Midnight Sun Baseball"". Goldpanners.com. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (February 28, 2005). "Steinbrenner's Rule: When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Blame an Agent". The New York Times.

- ^ "Steinbrenner vs. Dave Winfield – The 13 Greatest Yankees Feuds". ESPN. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Swift, E.M. (April 11, 1988). "Bringing their feud to a head, George Steinbrenner sought – 04.11.88 – SI Vault". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c Hunter, Ian (September 9, 2011). "Acid Flashback Friday: Dave Winfield Hits a Seagull". The Blue Jay Hunter. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Gross, Jane (August 6, 1983). "Winfield charges will be dropped". The New York Times. p. 1.29.

- ^ "PROFILES: Dave Winfield". The Diamond Angle Archive. Archived from the original on October 23, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2018 – via webcitation.org.

- ^ Chass, Murray (January 21, 1985). "Winfield Really Does Produce". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Wulf, Steve (September 10, 1984). "Teammates Dave Winfield and Don Mattingly are in a tight – 09.10.84 – SI Vault". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ "Don Mattingly remains a fan favorite at Yankee Stadium". Newsday. June 19, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ "Roger Maris 1961 Home Run Season". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ a b "Murray Chass On Baseball | Sorry, Harvey". Murray Chass. July 19, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Dave Winfield". SABR. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Hammill, Stephen (July 13, 2010). "A New York native and Tampa resident remembers the George Steinbrenner soap opera". Creative Loafing Tampa. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Winfield Agrees To Join Angels". Chicago Tribune. May 17, 1990. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ "MLB – Union challenges Rocker suspension with grievance". ESPN. February 1, 2000. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Plaschke, Bill (October 20, 1990). "Offerman Cited and Promoted". The Los Angeles Times. pp. C9. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ "BASEBALL; Winfield Hits for the Cycle". The New York Times. Associated Press. June 25, 1991.

- ^ a b Norwood, Robyn (August 15, 1991). "No Place Like This for Winfield's 400th : Angels: He becomes 23rd player to reach home run milestone, doing it in the area where he grew up". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Nemec, David; Flatow, Scott (2008). Great Baseball Feats, Facts and Figures. New York: Penguin Group. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-451-22363-0.

- ^ "The 3,000 Hit Club: Dave Winfield". Baseball Hall of Fame. September 16, 1993. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Keegan, Tom (September 11, 1994). "Owners try on global thinking cap". The Baltimore Sun. p. 2C.

- ^ Stark, Jayson (August 6, 2001). "Detente? Winfield gives thanks to the Boss". ESPN Classic. Retrieved November 30, 2025.

- ^ Media Player, Baseball Hall of Fame

- ^ "Dave Winfield". San Diego Hall of Champions Sports Museum. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ "100 Greatest Baseball Players by The Sporting News : A Legendary List by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ "Padres Hall of Fame". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014.

- ^ Antonen, Mel (August 3, 2001). "How to cap career is hard call Winfield picks the Padres for his plaque in Cooperstown". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012.

- ^ "NCAA And CWS, INC., Announce College World Series Legends Team". NCAA. May 6, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ "Big Ten Icons: Dave Winfield". Big Ten Network. October 19, 2010. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Hall-of-Famer David Winfield in Fairbanks to see his statue unveiled Friday". KUAC.org. June 21, 2024. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ "BMP Health Network". BMP Health Network. Archived from the original on May 26, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ Altman, Billy (August 3, 2008). "Yankee Greats, and Not-So-Greats, Celebrate the End of Many Eras". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ^ Brown, Tim (June 4, 2008). "Winfield's brainchild thrills Negro Leaguers – MLB". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ "Winfield Joining ESPN As Analyst". Yahoo! Sports. March 31, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ Simon, Andrew (December 5, 2013). "Winfield joins MLBPA staff as special assistant". Major League Baseball. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "Twins Legends to throw 2014 All-Star Game and Home Run Derby first pitches". Minnesota Twins. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ Randhawa, Manny. "Bud Fowler takes his place among baseball's immortals". mlb.com. MLB Advanced Media, LP. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (November 30, 1981). "WINFIELD LOOKS BACK ON SATISFYING SEASON". The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2025.

- ^ a b Murray, William D. (November 2, 1985). "Sports Instruction Enters Computer Age". UPI. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Lindstrom, Robert (July 11, 1985). "PC disk steps up to plate". The Oregonian. p. 20. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ "'Married... with Children' A Man for No Seasons (TV Episode 1994) - Dave Winfield as Dave Winfield". IMDb.

- ^ "Dave Winfield – Society for American Baseball Research".

- ^ a b "Dave Winfield Hall of Fame - The Official Website of Dave Winfield". davewinfieldhof.com.

- ^ a b Winfield Foundation: The First 20 Years publication

- ^ "The David M. Winfield Foundation, headed by the New..." UPI. September 26, 1983. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Eliason, Todd (August 18, 2011). "Making a Difference: MLB Hall of Famer Dave Winfield". SUCCESS. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "DerekJeter.com". Major League Baseball. June 29, 2006. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ "Dave Winfield Quotes". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

Further reading

- Schoor, Gene (1982). Dave Winfield : The 23 Million Dollar Man. Stein and Day. ISBN 0812828410.

- Skipper, Doug. "Dave Winfield". SABR.

- Winfield, Dave (1988). Winfield: A Player's Life. with Tom Parker. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393024679.

- Winfield, Dave (2007). Dropping the Ball: Baseball's Troubles and How We Can and Must Solve Them. with Michael Levin. Scribner. ISBN 978-1416534488.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB · ESPN · Baseball Reference · Fangraphs · Baseball Reference (Minors) · Retrosheet · Baseball Almanac

- Dave Winfield at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Dave Winfield at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Official website

- Dave Winfield at IMDb

- Career statistics from Basketball Reference

Dave Winfield

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Upbringing and Family Background

David Mark Winfield was born on October 3, 1951, in St. Paul, Minnesota, to Frank Winfield, a waiter on passenger trains, and Arline Winfield, a public school employee.[5][6] His parents separated when he was three years old, leaving his mother to raise him and his older brother, Steve, alone in the city's predominantly Black Rondo neighborhood.[6][7] Arline Winfield supported the family through her employment while emphasizing discipline, education, and perseverance amid economic challenges typical of the working-class community.[7] The Rondo area, a vibrant hub for St. Paul's Black residents during Winfield's youth, provided a close-knit environment where family and community ties influenced his early development, though it later faced disruption from urban renewal projects.[8] The brothers' upbringing in this setting fostered resilience, with Winfield later crediting his mother's influence for shaping his work ethic and community orientation.[7]Initial Athletic Development

David Mark Winfield, born October 3, 1951, in St. Paul, Minnesota, initiated his athletic pursuits in local youth programs amid a challenging family environment following his parents' divorce around age three. Raised by his mother, Arline Vivian Winfield, in a modest row house on Carroll Avenue in a predominantly African American neighborhood near the state capitol, he was instilled with an emphasis on education and discipline, learning a new word each night from his mother. These early years laid the foundation for his multi-sport involvement, reflecting the diverse athletic opportunities available in mid-20th-century urban Minnesota.[5] Winfield's initial development centered on baseball and hockey, sports he played as a youngster at community facilities like Oxford Playgrounds. There, under the coaching of Bill Peterson—one of the earliest figures to identify his raw talent—he refined fundamental skills such as hand-eye coordination and competitive drive, which would later distinguish him in higher levels of play. This playground-based training, common in St. Paul during the era, emphasized informal yet rigorous practice without early specialization, allowing Winfield to build versatility across sports before formal high school competition.[5] By his pre-teen and early teen years, Winfield's engagement extended to organized youth baseball, where he demonstrated leadership and prowess, foreshadowing achievements like captaining teams to regional successes. His mother's support and the neighborhood's sports culture fostered resilience, as Winfield balanced athletics with academic focus in a context where such multi-faceted development was normative rather than exceptional.[5]Amateur Career

High School Achievements

Winfield attended St. Paul Central High School in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he distinguished himself as a multi-sport athlete, primarily in baseball and basketball.[5] He earned All-St. Paul and All-Minnesota honors in both sports, reflecting his standout performances despite not achieving his full physical stature until his senior year.[5] In basketball, Winfield contributed significantly as a senior, averaging 9.0 points and 5.8 rebounds per game, helping to showcase his versatility as an athlete.[5] His baseball prowess drew professional attention early, as the Baltimore Orioles selected him in the 40th round of the 1969 MLB June Amateur Draft, though he declined to sign and instead accepted a full scholarship to the University of Minnesota.[2][5] Beyond school teams, Winfield teamed with his brother Steve on the Attucks-Brooks Post 606 American Legion baseball squad, leading it to two state championships and further honing his skills in competitive summer play.[5] These accomplishments underscored his raw talent and athletic potential, earning him posthumous induction into the St. Paul Central High School Athletic Hall of Fame in 1995.[5]College Performance at Minnesota

Winfield enrolled at the University of Minnesota in 1971, competing in both baseball and basketball for the Golden Gophers as a two-sport athlete. In basketball, he appeared in 46 games over two seasons as a forward, averaging 9.0 points and 5.8 rebounds per game.[5] His primary focus, however, was baseball, where he developed as a right-handed pitcher and outfielder from 1971 to 1973, contributing to a team that emphasized his versatile skills.[5] Over his collegiate baseball career, Winfield posted a 19-4 pitching record, demonstrating dominance on the mound for the Gophers.[5] His junior and senior years showcased increasing prowess, with standout performances in key games that highlighted his ability to overpower hitters through velocity and control.[9] Winfield's pinnacle came in 1973, his final season, when he earned All-America honors as a pitcher and led Minnesota to its only College World Series appearance.[9] In the tournament held in Omaha, Nebraska, from June 8 to 16, he started two games, pitching 17⅓ innings while allowing just one earned run, striking out 29 batters, and maintaining a shutout through much of the semifinal against USC before an unearned run scored.[5] [10] Offensively, he batted .467 during the series, underscoring his two-way threat.[10] Despite the Gophers finishing third overall, Winfield's exceptional contributions earned him College World Series Most Valuable Player recognition.[5] These feats solidified his status as one of the program's all-time greats, paving the way for his professional transition.[9]Professional Career

San Diego Padres Tenure (1973–1980)

Winfield was selected by the San Diego Padres with the fourth overall pick in the first round of the 1973 Major League Baseball Draft.[3] The Padres signed him shortly thereafter and promoted him directly to the major leagues without minor league seasoning, a rare occurrence for a recent draftee.[1] He made his MLB debut on June 19, 1973, at age 21, starting in right field against the Philadelphia Phillies at San Diego Stadium.[2] In his rookie season, Winfield appeared in 100 games, batting .277 with 12 home runs and 68 runs batted in (RBI), while splitting time between the outfield and pitching in two games.[2] During his initial years with the Padres, Winfield transitioned fully to outfield duties, establishing himself as a power-hitting corner outfielder with speed and defensive prowess. From 1974 to 1976, he posted batting averages above .280 each season, culminating in a .303 mark in 1976 accompanied by 25 home runs and 90 RBI.[2] His breakout came in 1977, when he earned his first All-Star selection and hit .280 with 21 home runs. Winfield maintained All-Star status annually through 1980, reflecting his rising dominance in the National League.[11] In 1978, he was named the Padres' team MVP after batting .289 with 24 home runs and 92 RBI, and he contributed to the National League's All-Star victory by scoring the game-winning run in the eighth inning.[12] Winfield's peak performance in San Diego occurred in 1979, when he led the National League with 118 RBI despite the Padres scoring only 603 runs as a team that year, finishing third in MVP voting.[1] He won his first Gold Glove Award that season for exceptional right field defense, followed by another in 1980.[11] Over his eight seasons with the Padres, Winfield compiled a .284 batting average, 154 home runs, 626 RBI, and 133 stolen bases, serving as the franchise's cornerstone player amid otherwise struggling teams that never finished above .500 during his tenure.[13] His contributions included leading the team in multiple offensive categories annually and providing stability in the outfield, though the Padres' lack of overall success limited postseason opportunities.[14]New York Yankees Period (1981–1990)

Winfield joined the New York Yankees on December 15, 1980, signing a 10-year contract valued at $23 million, the largest in professional sports history at that time.[15] In his debut season of 1981, he batted .294 with 13 home runs and 68 RBIs over 105 games, contributing defensively and offensively to the Yankees' American League pennant victory.[2] [1] However, his World Series performance was ineffective, managing only 1 hit in 22 at-bats against the Los Angeles Dodgers.[16] From 1982 to 1988, Winfield established himself as a perennial All-Star, earning selections each year while posting consistent power production, including six seasons with 100 or more RBIs.[2] [1] He won Gold Glove Awards for outstanding right field play in 1982–1985 and 1987, and Silver Slugger Awards from 1981 to 1985 recognizing his offensive prowess among American League outfielders.[2] His career batting line with the Yankees reflected durability and productivity, though tempered by occasional slumps and injuries; he averaged approximately 142 games per full season in that span, with a .290 batting average, 23 home runs, and 99 RBIs annually from 1982–1988.[2]| Year | Games | PA | Hits | HR | RBI | AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 105 | 440 | 114 | 13 | 68 | .294 | .360 | .464 | .824 |

| 1982 | 140 | 597 | 151 | 37 | 106 | .280 | .331 | .560 | .891 |

| 1983 | 152 | 664 | 169 | 32 | 116 | .283 | .345 | .513 | .858 |

| 1984 | 141 | 626 | 193 | 19 | 100 | .340 | .393 | .515 | .908 |

| 1985 | 155 | 689 | 174 | 26 | 114 | .275 | .328 | .471 | .799 |

| 1986 | 154 | 652 | 148 | 24 | 104 | .262 | .349 | .462 | .811 |

| 1987 | 156 | 655 | 158 | 27 | 97 | .275 | .358 | .457 | .815 |

| 1988 | 149 | 631 | 180 | 25 | 107 | .322 | .398 | .530 | .927 |

| 1990 | 20 | 67 | 13 | 2 | 6 | .213 | .269 | .361 | .629 |

Later Team Affiliations (1990–1995)

Winfield was traded from the New York Yankees to the California Angels on May 11, 1990, in exchange for pitcher Mike Witt, marking the end of his contentious tenure in New York and initiating a resurgence in his production at age 38.[17] With the Angels, he posted a .275 batting average and 72 home runs over 1990 and 1991, including 26 homers and 72 RBIs in 1990 alone, demonstrating sustained power despite his advancing age.[2] This period revitalized his career, as he ranked among the American League leaders in on-base percentage and slugging in limited action, contributing to the Angels' competitive push before departing as a free agent following the 1991 season.[17] Signing with the Toronto Blue Jays for the 1992 season, Winfield provided veteran leadership and clutch hitting to a contending team, batting .246 with 26 home runs and 72 RBIs in the regular season.[2] His most notable contribution came in Game 6 of the World Series against the Atlanta Braves on October 24, 1992, where his two-run double in the 11th inning scored Devon White and Candy Maldonado, securing a 4-2 victory and clinching Toronto's first championship.[18] This hit silenced earlier postseason critiques, as Winfield became the first player to deliver the decisive blow in a World Series-deciding game at age 41.[19] Winfield returned to his hometown Minnesota Twins via free agency in December 1992, signing a two-year contract to chase milestones with the team that drafted him years earlier.[20] Primarily serving as a designated hitter, he batted .212 with 9 home runs in 1993, reaching his 3,000th career hit on September 16 against the Oakland Athletics—a single to left field off Dennis Eckersley in the Metrodome—becoming the 19th player and first Minnesotan to achieve the feat for a local club.[20] The 1994 season was abbreviated by the players' strike after 115 games, during which he hit .161 in 47 appearances for the Twins before being traded to the Cleveland Indians on August 31; however, the deal did not result in play that year due to the work stoppage.[2] Reuniting with Cleveland after the strike's resolution, Winfield signed a minor-league contract on April 5, 1995, and made the Opening Day roster as the league's oldest active player at 43.[5] Limited to 46 games as a part-time designated hitter, he managed a .191 average with 5 home runs and 17 RBIs, including a pivotal pinch-hit home run on May 25 that sparked a comeback win against the Chicago White Sox.[21] A torn rotator cuff sidelined him late in the season, excluding him from the postseason roster despite the Indians' World Series appearance, after which he announced his retirement on February 7, 1996, concluding a 22-year career with 3,110 hits and 465 home runs.[22][5]Career Evaluation

Statistical Accomplishments and Records

Over his 22-season Major League Baseball career spanning 1973 to 1995, Dave Winfield accumulated 3,110 hits, 465 home runs, and 1,833 runs batted in (RBI), establishing himself as one of the most durable and productive outfielders of his era.[2] He played in 2,973 games, recording a .283 batting average, .353 on-base percentage, .475 slugging percentage, and .828 OPS across 11,003 at-bats.[2] Winfield's 64.2 Wins Above Replacement (WAR) reflect his value as both an offensive and defensive contributor, with 1,669 runs scored, 540 doubles, 88 triples, 223 stolen bases, and 5,221 total bases.[2]| Statistic | Career Total |

|---|---|

| Games Played | 2,973 |

| At-Bats | 11,003 |

| Hits | 3,110 |

| Home Runs | 465 |

| RBI | 1,833 |

| Batting Average | .283 |

| OPS | .828 |

| WAR | 64.2 |