Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solvent

View on Wikipedia

A solvent (from the Latin solvō, "loosen, untie, solve") is a substance that dissolves a solute, resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can also be a solid, a gas, or a supercritical fluid. Water is a solvent for polar molecules, and the most common solvent used by living things; all the ions and proteins in a cell are dissolved in water within the cell.

Major uses of solvents are in paints, paint removers, inks, and dry cleaning.[2] Specific uses for organic solvents are in dry cleaning (e.g. tetrachloroethylene); as paint thinners (toluene, turpentine); as nail polish removers and solvents of glue (acetone, methyl acetate, ethyl acetate); in spot removers (hexane, petrol ether); in detergents (citrus terpenes); and in perfumes (ethanol). Solvents find various applications in chemical, pharmaceutical, oil, and gas industries, including in chemical syntheses and purification processes

Some petrochemical solvents are highly toxic and emit volatile organic compounds. Biobased solvents are usually more expensive, but ideally less toxic and biodegradable. Biogenic raw materials usable for solvent production are for example lignocellulose, starch and sucrose, but also waste and byproducts from other industries (such as terpenes, vegetable oils and animal fats).[3]

Solutions and solvation

[edit]When one substance is dissolved into another, a solution is formed.[4] This is opposed to the situation when the compounds are insoluble like sand in water. In a solution, all of the ingredients are uniformly distributed at a molecular level and no residue remains. A solvent-solute mixture consists of a single phase with all solute molecules occurring as solvates (solvent-solute complexes), as opposed to separate continuous phases as in suspensions, emulsions and other types of non-solution mixtures. The ability of one compound to be dissolved in another is known as solubility; if this occurs in all proportions, it is called miscible.[citation needed]

In addition to mixing, the substances in a solution interact with each other at the molecular level. When something is dissolved, molecules of the solvent arrange around molecules of the solute. Heat transfer is involved and entropy is increased making the solution more thermodynamically stable than the solute and solvent separately. This arrangement is mediated by the respective chemical properties of the solvent and solute, such as hydrogen bonding, dipole moment and polarizability.[5] Solvation does not cause a chemical reaction or chemical configuration changes in the solute. However, solvation resembles a coordination complex formation reaction, often with considerable energetics (heat of solvation and entropy of solvation) and is thus far from a neutral process.

When one substance dissolves into another, a solution is formed. A solution is a homogeneous mixture consisting of a solute dissolved into a solvent. The solute is the substance that is being dissolved, while the solvent is the dissolving medium. Solutions can be formed with many different types and forms of solutes and solvents.

Solvent classifications

[edit]Solvents can be broadly classified into two categories: polar and non-polar. A special case is elemental mercury, whose solutions are known as amalgams; also, other metal solutions exist which are liquid at room temperature.[citation needed]

Generally, the dielectric constant of the solvent provides a rough measure of a solvent's polarity. The strong polarity of water is indicated by its high dielectric constant of 88 (at 0 °C).[6] Solvents with a dielectric constant of less than 15 are generally considered to be nonpolar.[7]

The dielectric constant measures the solvent's tendency to partly cancel the field strength of the electric field of a charged particle immersed in it. This reduction is then compared to the field strength of the charged particle in a vacuum.[7] Heuristically, the dielectric constant of a solvent can be thought of as its ability to reduce the solute's effective internal charge. Generally, the dielectric constant of a solvent is an acceptable predictor of the solvent's ability to dissolve common ionic compounds, such as salts.[citation needed]

Other polarity scales

[edit]Dielectric constants are not the only measure of polarity. Because solvents are used by chemists to carry out chemical reactions or observe chemical and biological phenomena, more specific measures of polarity are required. Most of these measures are sensitive to chemical structure.

The Grunwald–Winstein mY scale measures polarity in terms of solvent influence on buildup of positive charge of a solute during a chemical reaction.

Kosower's Z scale measures polarity in terms of the influence of the solvent on UV-absorption maxima of a salt, usually pyridinium iodide or the pyridinium zwitterion.[8]

Donor number and donor acceptor scale measures polarity in terms of how a solvent interacts with specific substances, like a strong Lewis acid or a strong Lewis base.[9]

The Hildebrand parameter is the square root of cohesive energy density. It can be used with nonpolar compounds, but cannot accommodate complex chemistry.

Reichardt's dye, a solvatochromic dye that changes color in response to polarity, gives a scale of ET(30) values. ET is the transition energy between the ground state and the lowest excited state in kcal/mol, and (30) identifies the dye. Another, roughly correlated scale (ET(33)) can be defined with Nile red.

Gregory's solvent ϸ parameter is a quantum chemically derived charge density parameter.[10] This parameter seems to reproduce many of the experimental solvent parameters (especially the donor and acceptor numbers) using this charge decomposition analysis approach, with an electrostatic basis. The ϸ parameter was originally developed to quantify and explain the Hofmeister series by quantifying polyatomic ions and the monatomic ions in a united manner.

The polarity, dipole moment, polarizability and hydrogen bonding of a solvent determines what type of compounds it is able to dissolve and with what other solvents or liquid compounds it is miscible. Generally, polar solvents dissolve polar compounds best and non-polar solvents dissolve non-polar compounds best; hence "like dissolves like". Strongly polar compounds like sugars (e.g. sucrose) or ionic compounds, like inorganic salts (e.g. table salt) dissolve only in very polar solvents like water, while strongly non-polar compounds like oils or waxes dissolve only in very non-polar organic solvents like hexane. Similarly, water and hexane (or vinegar and vegetable oil) are not miscible with each other and will quickly separate into two layers even after being shaken well.

Polarity can be separated to different contributions. For example, the Kamlet-Taft parameters are dipolarity/polarizability (π*), hydrogen-bonding acidity (α) and hydrogen-bonding basicity (β). These can be calculated from the wavelength shifts of 3–6 different solvatochromic dyes in the solvent, usually including Reichardt's dye, nitroaniline and diethylnitroaniline. Another option, Hansen solubility parameters, separates the cohesive energy density into dispersion, polar, and hydrogen bonding contributions.

Polar protic and polar aprotic

[edit]Solvents with a dielectric constant (more accurately, relative static permittivity) greater than 15 (i.e. polar or polarizable) can be further divided into protic and aprotic. Protic solvents, such as water, solvate anions (negatively charged solutes) strongly via hydrogen bonding. Polar aprotic solvents, such as acetone or dichloromethane, tend to have large dipole moments (separation of partial positive and partial negative charges within the same molecule) and solvate positively charged species via their negative dipole.[11] In chemical reactions the use of polar protic solvents favors the SN1 reaction mechanism, while polar aprotic solvents favor the SN2 reaction mechanism. These polar solvents are capable of forming hydrogen bonds with water to dissolve in water whereas non-polar solvents are not capable of strong hydrogen bonds.

Physical properties

[edit]Properties table of common solvents

[edit]The solvents are grouped into nonpolar, polar aprotic, and polar protic solvents, with each group ordered by increasing polarity. The properties of solvents which exceed those of water are bolded.

| Solvent | Chemical formula | Boiling point[12] (°C) |

Dielectric constant[13] | Density (g/mL) |

Dipole moment (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nonpolar hydrocarbon solvents[edit] | |||||

| Pentane |

CH3CH2CH2CH2CH3 |

36.1 | 1.84 | 0.626 | 0.00 |

| Hexane |

CH3CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3 |

69 | 1.88 | 0.655 | 0.00 |

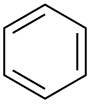

| Benzene |  C6H6 |

80.1 | 2.3 | 0.879 | 0.00 |

| Heptane |

H3C(CH2)5CH3 |

98.38 | 1.92 | 0.680 | 0.0 |

| Toluene |

C6H5-CH3 |

111 | 2.38 | 0.867 | 0.36 |

| 1,4-Dioxane |  C4H8O2 |

101.1 | 2.3 | 1.033 | 0.45 |

| Diethyl ether |

CH3CH2-O-CH2CH3 |

34.6 | 4.3 | 0.713 | 1.15 |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) |  C4H8O |

66 | 7.5 | 0.886 | 1.75 |

Nonpolar chlorocarbon solvents[edit] | |||||

| Chloroform |

CHCl3 |

61.2 | 4.81 | 1.498 | 1.04 |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) |

CH2Cl2 |

39.6 | 9.1 | 1.3266 | 1.60 |

| Ethyl acetate |  CH3-C(=O)-O-CH2-CH3 |

77.1 | 6.02 | 0.894 | 1.78 |

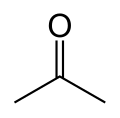

| Acetone |  CH3-C(=O)-CH3 |

56.1 | 21 | 0.786 | 2.88 |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) |  H-C(=O)N(CH3)2 |

153 | 38 | 0.944 | 3.82 |

| Acetonitrile (MeCN) | CH3-C≡N |

82 | 37.5 | 0.786 | 3.92 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) |  CH3-S(=O)-CH3 |

189 | 46.7 | 1.092 | 3.96 |

| Nitromethane |

CH3-NO2 |

100–103 | 35.87 | 1.1371 | 3.56 |

| Propylene carbonate |

C4H6O3 |

240 | 64.0 | 1.205 | 4.9 |

| Ammonia |

NH3 |

-33.3 | 17 | 0.674

(at −33.3 °C) |

1.42 |

| Formic acid |  H-C(=O)OH |

100.8 | 58 | 1.21 | 1.41 |

| n-Butanol | CH3CH2CH2CH2OH |

117.7 | 18 | 0.810 | 1.63 |

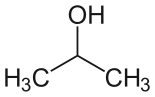

| Isopropyl alcohol (IPA) |  CH3-CH(-OH)-CH3 |

82.6 | 18 | 0.785 | 1.66 |

| n-Propanol |

CH3CH2CH2OH |

97 | 20 | 0.803 | 1.68 |

| Ethanol | CH3CH2OH |

78.2 | 24.55 | 0.789 | 1.69 |

| Methanol |

CH3OH |

64.7 | 33 | 0.791 | 1.70 |

| Acetic acid |  CH3-C(=O)OH |

118 | 6.2 | 1.049 | 1.74 |

| Water |  H-O-H |

100 | 80 | 1.000 | 1.85 |

The ACS Green Chemistry Institute maintains a tool for the selection of solvents based on a principal component analysis of solvent properties.[14]

Hansen solubility parameter values

[edit]The Hansen solubility parameter (HSP) values[15][16][17] are based on dispersion bonds (δD), polar bonds (δP) and hydrogen bonds (δH). These contain information about the inter-molecular interactions with other solvents and also with polymers, pigments, nanoparticles, etc. This allows for rational formulations knowing, for example, that there is a good HSP match between a solvent and a polymer. Rational substitutions can also be made for "good" solvents (effective at dissolving the solute) that are "bad" (expensive or hazardous to health or the environment). The following table shows that the intuitions from "non-polar", "polar aprotic" and "polar protic" are put numerically – the "polar" molecules have higher levels of δP and the protic solvents have higher levels of δH. Because numerical values are used, comparisons can be made rationally by comparing numbers. For example, acetonitrile is much more polar than acetone but exhibits slightly less hydrogen bonding.

| Solvent | Chemical formula | δD Dispersion | δP Polar | δH Hydrogen bonding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Non-polar solvents[edit] | ||||

| n-Pentane | CH3-(CH2)3-CH3 | 14.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| n-Hexane | CH3-(CH2)4-CH3 | 14.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| n-Heptane | CH3-(CH2)5-CH3 | 15.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cyclohexane | /-(CH2)6-\ | 16.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Benzene | C6H6 | 18.4 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Toluene | C6H5-CH3 | 18.0 | 1.4 | 2.0 |

| Diethyl ether | C2H5-O-C2H5 | 14.5 | 2.9 | 4.6 |

| Chloroform | CHCl3 | 17.8 | 3.1 | 5.7 |

| 1,4-Dioxane | /-(CH2)2O(CH2)2O-\ | 17.5 | 1.8 | 9.0 |

Polar aprotic solvents[edit] | ||||

| Ethyl acetate | CH3-C(=O)-O-C2H5 | 15.8 | 5.3 | 7.2 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | /-(CH2)4-O-\ | 16.8 | 5.7 | 8.0 |

| Dichloromethane | CH2Cl2 | 17.0 | 7.3 | 7.1 |

| Acetone | CH3-C(=O)-CH3 | 15.5 | 10.4 | 7.0 |

| Acetonitrile | CH3-C≡N | 15.3 | 18.0 | 6.1 |

| Dimethylformamide | H-C(=O)-N(CH3)2 | 17.4 | 13.7 | 11.3 |

| Dimethylacetamide | CH3-C(=O)-N(CH3)2 | 16.8 | 11.5 | 10.2 |

| Dimethylimidazolidinone | C5H10N2O | 18.0 | 10.5 | 9.7 |

| Dimethylpropyleneurea | C6H12N2O | 17.8 | 9.5 | 9.3 |

| N-Methylpyrrolidone | /-(CH2)3-N(CH3)-C(=O)-\ | 18.0 | 12.3 | 7.2 |

| Propylene carbonate | C4H6O3 | 20.0 | 18.0 | 4.1 |

| Pyridine | C5H5N | 19.0 | 8.8 | 5.9 |

| Sulfolane | /-(CH2)4-S(=O)2-\ | 19.2 | 16.2 | 9.4 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | CH3-S(=O)-CH3 | 18.4 | 16.4 | 10.2 |

Polar protic solvents[edit] | ||||

| Acetic acid | CH3-C(=O)-OH | 14.5 | 8.0 | 13.5 |

| n-Butanol | CH3-(CH2)3-OH | 16.0 | 5.7 | 15.8 |

| Isopropanol | (CH3)2-CH-OH | 15.8 | 6.1 | 16.4 |

| n-Propanol | CH3-(CH2)2-OH | 16.0 | 6.8 | 17.4 |

| Ethanol | C2H5-OH | 15.8 | 8.8 | 19.4 |

| Methanol | CH3-OH | 14.7 | 12.3 | 22.3 |

| Ethylene glycol | HO-(CH2)2-OH | 17.0 | 11.0 | 26.0 |

| Glycerol | HO-CH2-CH(OH)-CH2-OH | 17.4 | 12.1 | 29.3 |

| Formic acid | H-C(=O)-OH | 14.6 | 10.0 | 14.0 |

| Water | H-O-H | 15.5 | 16.0 | 42.3 |

If, for environmental or other reasons, a solvent or solvent blend is required to replace another of equivalent solvency, the substitution can be made on the basis of the Hansen solubility parameters of each. The values for mixtures are taken as the weighted averages of the values for the neat solvents. This can be calculated by trial-and-error, a spreadsheet of values, or HSP software.[15][16] A 1:1 mixture of toluene and 1,4 dioxane has δD, δP and δH values of 17.8, 1.6 and 5.5, comparable to those of chloroform at 17.8, 3.1 and 5.7 respectively. Because of the health hazards associated with toluene itself, other mixtures of solvents may be found using a full HSP dataset.

Boiling point

[edit]| Solvent | Boiling point (°C)[12] |

|---|---|

| ethylene dichloride | 83.48 |

| pyridine | 115.25 |

| methyl isobutyl ketone | 116.5 |

| methylene chloride | 39.75 |

| isooctane | 99.24 |

| carbon disulfide | 46.3 |

| carbon tetrachloride | 76.75 |

| o-xylene | 144.42 |

The boiling point is an important property because it determines the speed of evaporation. Small amounts of low-boiling-point solvents like diethyl ether, dichloromethane, or acetone will evaporate in seconds at room temperature, while high-boiling-point solvents like water or dimethyl sulfoxide need higher temperatures, an air flow, or the application of vacuum for fast evaporation.

- Low boilers: boiling point below 100 °C (boiling point of water)

- Medium boilers: between 100 °C and 150 °C

- High boilers: above 150 °C

Density

[edit]Most organic solvents have a lower density than water, which means they are lighter than and will form a layer on top of water. Important exceptions are most of the halogenated solvents like dichloromethane or chloroform will sink to the bottom of a container, leaving water as the top layer. This is crucial to remember when partitioning compounds between solvents and water in a separatory funnel during chemical syntheses.

Often, specific gravity is cited in place of density. Specific gravity is defined as the density of the solvent divided by the density of water at the same temperature. As such, specific gravity is a unitless value. It readily communicates whether a water-insoluble solvent will float (SG < 1.0) or sink (SG > 1.0) when mixed with water.

| Solvent | Specific gravity[18] |

|---|---|

| Pentane | 0.626 |

| Petroleum ether | 0.656 |

| Hexane | 0.659 |

| Heptane | 0.684 |

| Diethyl amine | 0.707 |

| Diethyl ether | 0.713 |

| Triethyl amine | 0.728 |

| tert-Butyl methyl ether | 0.741 |

| Cyclohexane | 0.779 |

| tert-Butyl alcohol | 0.781 |

| Isopropanol | 0.785 |

| Acetonitrile | 0.786 |

| Ethanol | 0.789 |

| Acetone | 0.790 |

| Methanol | 0.791 |

| Methyl isobutyl ketone | 0.798 |

| Isobutyl alcohol | 0.802 |

| 1-Propanol | 0.803 |

| Methyl ethyl ketone | 0.805 |

| 2-Butanol | 0.808 |

| Isoamyl alcohol | 0.809 |

| 1-Butanol | 0.810 |

| Diethyl ketone | 0.814 |

| 1-Octanol | 0.826 |

| p-Xylene | 0.861 |

| m-Xylene | 0.864 |

| Toluene | 0.867 |

| Dimethoxyethane | 0.868 |

| Benzene | 0.879 |

| Butyl acetate | 0.882 |

| 1-Chlorobutane | 0.886 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 0.889 |

| Ethyl acetate | 0.895 |

| o-Xylene | 0.897 |

| Hexamethylphosphorus triamide | 0.898 |

| 2-Ethoxyethyl ether | 0.909 |

| N,N-Dimethylacetamide | 0.937 |

| Diethylene glycol dimethyl ether | 0.943 |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide | 0.944 |

| 2-Methoxyethanol | 0.965 |

| Pyridine | 0.982 |

| Propanoic acid | 0.993 |

| Water | 1.000 |

| 2-Methoxyethyl acetate | 1.009 |

| Benzonitrile | 1.01 |

| 1-Methyl-2-pyrrolidinone | 1.028 |

| Hexamethylphosphoramide | 1.03 |

| 1,4-Dioxane | 1.033 |

| Acetic acid | 1.049 |

| Acetic anhydride | 1.08 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | 1.092 |

| Chlorobenzene | 1.1066 |

| Deuterium oxide | 1.107 |

| Ethylene glycol | 1.115 |

| Diethylene glycol | 1.118 |

| Propylene carbonate | 1.21 |

| Formic acid | 1.22 |

| 1,2-Dichloroethane | 1.245 |

| Glycerin | 1.261 |

| Carbon disulfide | 1.263 |

| 1,2-Dichlorobenzene | 1.306 |

| Methylene chloride | 1.325 |

| Nitromethane | 1.382 |

| 2,2,2-Trifluoroethanol | 1.393 |

| Chloroform | 1.498 |

| 1,1,2-Trichlorotrifluoroethane | 1.575 |

| Carbon tetrachloride | 1.594 |

| Tetrachloroethylene | 1.623 |

Multicomponent solvents

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Multicomponent solvents appeared after World War II in the USSR, and continue to be used and produced in the post-Soviet states. These solvents may have one or more applications, but they are not universal preparations.

Solvents

[edit]| Name | Composition |

|---|---|

| Solvent 645 | toluene 50%, butyl acetate 18%, ethyl acetate 12%, butanol 10%, ethanol 10%. |

| Solvent 646 | toluene 50%, ethanol 15%, butanol 10%, butyl- or amyl acetate 10%, ethyl cellosolve 8%, acetone 7%[19] |

| Solvent 647 | butyl- or amyl acetate 29.8%, ethyl acetate 21.2%, butanol 7.7%, toluene or benzopyrene 41.3%[20] |

| Solvent 648 | butyl acetate 50%, ethanol 10%, butanol 20%, toluene 20%[21] |

| Solvent 649 | ethyl cellosolve 30%, butanol 20%, xylene 50% |

| Solvent 650 | ethyl cellosolve 20%, butanol 30%, xylene 50%[22] |

| Solvent 651 | white spirit 90%, butanol 10% |

| Solvent KR-36 | butyl acetate 20%, butanol 80% |

| Solvent R-4 | toluene 62%, acetone 26%, butyl acetate 12%. |

| Solvent R-10 | xylene 85%, acetone 15%. |

| Solvent R-12 | toluene 60%, butyl acetate 30%, xylene 10%. |

| Solvent R-14 | cyclohexanone 50%, toluene 50%. |

| Solvent R-24 | solvent[clarification needed] 50%, xylene 35%, acetone 15%. |

| Solvent R-40 | toluene 50%, ethyl cellosolve 30%, acetone 20%. |

| Solvent R-219 | toluene 34%, cyclohexanone 33%, acetone 33%. |

| Solvent R-3160 | butanol 60%, ethanol 40%. |

| Solvent RCC | xylene 90%, butyl acetate 10%. |

| Solvent RML | ethanol 64%, ethylcellosolve 16%, toluene 10%, butanol 10%. |

| Solvent PML-315 | toluene 25%, xylene 25%, butyl acetate 18%, ethyl cellosolve 17%, butanol 15%. |

| Solvent PC-1 | toluene 60%, butyl acetate 30%, xylene 10%. |

| Solvent PC-2 | white spirit 70%, xylene 30%. |

| Solvent RFG | ethanol 75%, butanol 25%. |

| Solvent RE-1 | xylene 50%, acetone 20%, butanol 15%, ethanol 15%. |

| Solvent RE-2 | petroleum spirits 70%, ethanol 20%, acetone 10%. |

| Solvent RE-3 | petroleum spirits 50%, ethanol 20%, acetone 20%, ethyl cellosolve 10%. |

| Solvent RE-4 | petroleum spirits 50%, acetone 30%, ethanol 20%. |

| Solvent FK-1 (?) | absolute alcohol (99.8%) 95%, ethyl acetate 5% |

Thinners

[edit]| Name | Composition |

|---|---|

| Thinner RKB-1 | butanol 50%, xylene 50% |

| Thinner RKB-2 | butanol 95%, xylene 5% |

| Thinner RKB-3 | xylene 90%, butanol 10% |

| Thinner M | ethanol 65%, butyl acetate 30%, ethyl acetate 5%. |

| Thinner P-7 | cyclohexanone 50%, ethanol 50%. |

| Thinner R-197 | xylene 60%, butyl acetate 20%, ethyl cellosolve 20%. |

| Thinner of WFD | toluene 50%, butyl acetate (or amyl acetate) 18%, butanol 10%, ethanol 10%, ethyl acetate 9%, acetone 3%. |

Safety

[edit]Fire

[edit]Most organic solvents are flammable or highly flammable, depending on their volatility. Exceptions are some chlorinated solvents like dichloromethane and chloroform. Mixtures of solvent vapors and air can explode. Solvent vapors are heavier than air; they will sink to the bottom and can travel large distances nearly undiluted. Solvent vapors can also be found in supposedly empty drums and cans, posing a flash fire hazard; hence empty containers of volatile solvents should be stored open and upside down.

Both diethyl ether and carbon disulfide have exceptionally low autoignition temperatures which increase greatly the fire risk associated with these solvents. The autoignition temperature of carbon disulfide is below 100 °C (212 °F), so objects such as steam pipes, light bulbs, hotplates, and recently extinguished bunsen burners are able to ignite its vapors.

In addition some solvents, such as methanol, can burn with a very hot flame which can be nearly invisible under some lighting conditions.[23][24] This can delay or prevent the timely recognition of a dangerous fire, until flames spread to other materials.

Explosive peroxide formation

[edit]Ethers like diethyl ether and tetrahydrofuran (THF) can form highly explosive organic peroxides upon exposure to oxygen and light. THF is normally more likely to form such peroxides than diethyl ether. One of the most susceptible solvents is diisopropyl ether, but all ethers are considered to be potential peroxide sources.

The heteroatom (oxygen) stabilizes the formation of a free radical which is formed by the abstraction of a hydrogen atom by another free radical.[clarification needed] The carbon-centered free radical thus formed is able to react with an oxygen molecule to form a peroxide compound. The process of peroxide formation is greatly accelerated by exposure to even low levels of light, but can proceed slowly even in dark conditions.

Unless a desiccant is used which can destroy the peroxides, they will concentrate during distillation, due to their higher boiling point. When sufficient peroxides have formed, they can form a crystalline, shock-sensitive solid precipitate at the mouth of a container or bottle. Minor mechanical disturbances, such as scraping the inside of a vessel, the dislodging of a deposit, or merely twisting the cap may provide sufficient energy for the peroxide to detonate or explode violently.

Peroxide formation is not a significant problem when fresh solvents are used up quickly; they are more of a problem in laboratories which may take years to finish a single bottle. Low-volume users should acquire only small amounts of peroxide-prone solvents, and dispose of old solvents on a regular periodic schedule.

To avoid explosive peroxide formation, ethers should be stored in an airtight container, away from light, because both light and air can encourage peroxide formation.[25]

A number of tests can be used to detect the presence of a peroxide in an ether; one is to use a combination of iron(II) sulfate and potassium thiocyanate. The peroxide is able to oxidize the Fe2+ ion to an Fe3+ ion, which then forms a deep-red coordination complex with the thiocyanate.

Peroxides may be removed by washing with acidic iron(II) sulfate, filtering through alumina, or distilling from sodium/benzophenone. Alumina degrades the peroxides but some could remain intact in it, therefore it must be disposed of properly.[26] The advantage of using sodium/benzophenone is that moisture and oxygen are removed as well.[27]

Health effects

[edit]General health hazards associated with solvent exposure include toxicity to the nervous system, reproductive damage, liver and kidney damage, respiratory impairment, cancer, hearing loss,[28][29] and dermatitis.[30]

Acute exposure

[edit]Many solvents[which?] can lead to a sudden loss of consciousness if inhaled in large amounts.[citation needed] Solvents like diethyl ether and chloroform have been used in medicine as anesthetics, sedatives, and hypnotics for a long time.[when?] Many solvents (e.g. from gasoline or solvent-based glues) are abused recreationally in glue sniffing, often with harmful long-term health effects such as neurotoxicity or cancer. Fraudulent substitution of 1,5-pentanediol by the psychoactive 1,4-butanediol by a subcontractor caused the Bindeez product recall.[31]

Ethanol (grain alcohol) is a widely used and abused psychoactive drug. If ingested, the so-called "toxic alcohols" (other than ethanol) such as methanol, 1-propanol, and ethylene glycol metabolize into toxic aldehydes and acids, which cause potentially fatal metabolic acidosis.[32] The commonly available alcohol solvent methanol can cause permanent blindness or death if ingested. The solvent 2-butoxyethanol, used in fracking fluids, can cause hypotension and metabolic acidosis.[33]

Chronic exposure

[edit]Chronic solvent exposures are often caused by the inhalation of solvent vapors, or the ingestion of diluted solvents, repeated over the course of an extended period.

Some solvents can damage internal organs like the liver, the kidneys, the nervous system, or the brain. The cumulative brain effects of long-term or repeated exposure to some solvents is called chronic solvent-induced encephalopathy (CSE).[34]

Chronic exposure to organic solvents in the work environment can produce a range of adverse neuropsychiatric effects. For example, occupational exposure to organic solvents has been associated with higher numbers of painters suffering from alcoholism.[35] Ethanol has a synergistic effect when taken in combination with many solvents; for instance, a combination of toluene/benzene and ethanol causes greater nausea/vomiting than either substance alone.

Some organic solvents are known or suspected to be cataractogenic. A mixture of aromatic hydrocarbons, aliphatic hydrocarbons, alcohols, esters, ketones, and terpenes were found to greatly increase the risk of developing cataracts in the lens of the eye.[36]

Environmental contamination

[edit]A major pathway of induced health effects arises from spills or leaks of solvents, especially chlorinated solvents, that reach the underlying soil. Since solvents readily migrate substantial distances, the creation of widespread soil contamination is not uncommon; this is particularly a health risk if aquifers are affected.[37] Vapor intrusion can occur from sites with extensive subsurface solvent contamination.[38]

See also

[edit]- ASTDR

- Construction | Refurbishment | Renovation

- Free energy of solvation

- IARC

- Solvents are often refluxed with an appropriate desiccant prior to distillation to remove water. This may be performed prior to a chemical synthesis where water may interfere with the intended reaction

- List of water-miscible solvents

- Lyoluminescence

- Occupational health

- Partition coefficient (log P) is a measure of differential solubility of a compound in two solvents

- Pollution

- Solvation

- Solvent systems exist outside the realm of ordinary organic solvents: Supercritical fluids, ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents

- Superfund

- Volatile Organic Compound

- Water model

- Water pollution

References

[edit]- ^ "What's the Difference Between Acetone and Non-acetone Nail Polish Remover?". 3 November 2009.

- ^ Stoye, Dieter (2000). "Solvents". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_437. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ "Biobased Solvents Market Report: Market Analysis and Forecasts". Ceresana Market Research. Retrieved 12 February 2025.

- ^ Tinoco I, Sauer K, Wang JC (2002). Physical Chemistry. Prentice Hall. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-13-026607-1.

- ^ Lowery and Richardson, pp. 181–183

- ^ Malmberg CG, Maryott AA (January 1956). "Dielectric Constant of Water from 0° to 100 °C". Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards. 56 (1): 1. doi:10.6028/jres.056.001.

- ^ a b Lowery and Richardson, p. 177.

- ^ Kosower, E.M. (1969) "An introduction to Physical Organic Chemistry" Wiley: New York, p. 293

- ^ Gutmann V (1976). "Solvent effects on the reactivities of organometallic compounds". Coord. Chem. Rev. 18 (2): 225. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(00)82045-7.

- ^ Gregory, Kasimir P.; Wanless, Erica J.; Webber, Grant B.; Craig, Vincent S. J.; Page, Alister J. (2024). "A first-principles alternative to empirical solvent parameters". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26 (31): 20750–20759. Bibcode:2024PCCP...2620750G. doi:10.1039/D4CP01975J. PMID 38988220.

- ^ Lowery and Richardson, p. 183.

- ^ a b Solvent Properties – Boiling Point Archived 14 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Xydatasource.com. Retrieved on 26 January 2013.

- ^ Dielectric Constant Archived 4 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Macro.lsu.edu. Retrieved on 26 January 2013.

- ^ Diorazio, Louis J.; Hose, David R. J.; Adlington, Neil K. (2016). "Toward a More Holistic Framework for Solvent Selection". Organic Process Research & Development. 20 (4): 760–773. doi:10.1021/acs.oprd.6b00015.

- ^ a b Abbott S, Hansen CM (2008). Hansen solubility parameters in practice. Hansen-Solubility. ISBN 978-0-9551220-2-6.

- ^ a b Hansen, Charles M. (15 June 2007). Hansen Solubility Parameters: A User's Handbook, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-0683-4.

- ^ Bergin, Shane D.; Sun, Zhenyu; Rickard, David; Streich, Philip V.; Hamilton, James P.; Coleman, Jonathan N. (25 August 2009). "Multicomponent Solubility Parameters for Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube−Solvent Mixtures". ACS Nano. 3 (8): 2340–2350. doi:10.1021/nn900493u. ISSN 1936-0851.

- ^ Selected solvent properties – Specific Gravity Archived 14 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Xydatasource.com. Retrieved on 26 January 2013.

- ^ "dcpt.ru Solvent 646 Characteristics (ru)".

- ^ "dcpt.ru Solvent 647 Characteristics (ru)".

- ^ "dcpt.ru Solvent 648 Characteristics (ru)". Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ "dcpt.ru Solvent 650 Characteristics (ru)".

- ^ Fanick ER, Smith LR, Baines TM (1 October 1984). "Safety Related Additives for Methanol Fuel". SAE Technical Paper Series. Vol. 1. Warrendale, PA: SAE. doi:10.4271/841378. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017.

- ^ Anderson JE, Magyarl MW, Siegl WO (1 July 1985). "Concerning the Luminosity of Methanol-Hydrocarbon Diffusion Flames". Combustion Science and Technology. 43 (3–4): 115–125. doi:10.1080/00102208508947000. ISSN 0010-2202.

- ^ "Peroxides and Ethers | Environmental Health, Safety and Risk Management". www.uaf.edu. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "Handling of Peroxide Forming Chemicals". Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Inoue, Ryo; Yamaguchi, Mana; Murakami, Yoshiaki; Okano, Kentaro; Mori, Atsunori (31 October 2018). "Revisiting of Benzophenone Ketyl Still: Use of a Sodium Dispersion for the Preparation of Anhydrous Solvents". ACS Omega. 3 (10): 12703–12706. doi:10.1021/acsomega.8b01707. ISSN 2470-1343. PMC 6210062. PMID 30411016.

- ^ Preventing Hearing Loss Caused by Chemical (Ototoxicity) and Noise Exposure (PDF) (Report). 8 March 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Fuente, A.; McPherson, B. (2006). "Organic solvents and hearing loss: The challenge for audiology". International Journal of Audiology. 45 (7): 367–381. doi:10.1080/14992020600753205. PMID 16938795.

- ^ "Solvents". Occupational Safety & Health Administration. U.S. Department of Labor. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016.

- ^ Rood, David (7 November 2007). "National: Recall ordered for toy that turns into drug". www.theage.com.au.

- ^ Kraut JA, Mullins ME (January 2018). "Toxic Alcohols". The New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (3): 270–280. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1615295. PMID 29342392. S2CID 36652482.

- ^ Hung T, Dewitt CR, Martz W, Schreiber W, Holmes DT (July 2010). "Fomepizole fails to prevent progression of acidosis in 2-butoxyethanol and ethanol coingestion". Clinical Toxicology. 48 (6): 569–71. doi:10.3109/15563650.2010.492350. PMID 20560787. S2CID 23257894.

- ^ van der Laan, Gert; Sainio, Markku (1 August 2012). "Chronic Solvent induced Encephalopathy: A step forward". NeuroToxicology. Neurotoxicity and Neurodegeneration: Local Effect and Global Impact. 33 (4): 897–901. Bibcode:2012NeuTx..33..897V. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2012.04.012. ISSN 0161-813X. PMID 22560998.

- ^ Lundberg I, Gustavsson A, Högberg M, Nise G (June 1992). "Diagnoses of alcohol abuse and other neuropsychiatric disorders among house painters compared with house carpenters". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 49 (6): 409–15. doi:10.1136/oem.49.6.409. PMC 1012122. PMID 1606027.

- ^ Raitta C, Husman K, Tossavainen A (August 1976). "Lens changes in car painters exposed to a mixture of organic solvents". Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Klinische und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. Albrecht von Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 200 (2): 149–56. doi:10.1007/bf00414364. PMID 1086605. S2CID 31344706.

- ^ Matteucci, Federica; Ercole, Claudia; del Gallo, Maddalena (2015). "A study of chlorinated solvent contamination of the aquifers of an industrial area in central Italy: a possibility of bioremediation". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 924. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00924. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 4556989. PMID 26388862.

- ^ Forand SP, Lewis-Michl EL, Gomez MI (April 2012). "Adverse birth outcomes and maternal exposure to trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethylene through soil vapor intrusion in New York State". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (4): 616–21. doi:10.1289/ehp.1103884. PMC 3339451. PMID 22142966.

Bibliography

[edit]- Lowery TH, Richardson KS (1987). Mechanism and Theory in Organic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-364044-3.

External links

[edit]- Solvent selection tool ACS Green Chemistry Institute

- "European Solvents Industry Group – ESIG – ESIG European Solvents Industry Group" Solvents in Europe.

- Table and text O-Chem Lecture

- Tables Properties and toxicities of organic solvents

- CDC – Organic Solvents – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

- EPA – Solvent Contaminated Wipes

Solvent

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Solutions and Solvation

A solution is a homogeneous mixture composed of a solute dispersed at the molecular or ionic level within a solvent, the component present in excess.[1] The solute particles are uniformly distributed, resulting in a single phase with properties distinct from those of the pure components, such as altered boiling or freezing points.[5] Solutions form when the solute-solvent interactions are sufficiently strong to overcome the cohesive forces within the pure solute and solvent.[6] Solvation denotes the stabilization of solute particles through direct interactions with surrounding solvent molecules, often forming a solvation shell.[7] This process involves three sequential steps: separation of solute units against their lattice or intermolecular attractions (endothermic, positive ΔH), separation of solvent molecules to create space (also endothermic), and the exothermic formation of solute-solvent attractions that release energy exceeding the input from prior steps for spontaneous dissolution.[6] For ionic solutes, solvation typically manifests as ion-dipole interactions, where polar solvent molecules orient their negative ends toward cations and positive ends toward anions; in non-aqueous solvents, similar dipole or induced dipole forces apply.[5] The empirical principle "like dissolves like" governs solubility, positing that solvents dissolve solutes of similar polarity: polar or ionic solutes favor polar solvents via dipole-dipole or hydrogen bonding, while nonpolar solutes dissolve in nonpolar solvents through London dispersion forces.[8] This arises from the dominance of solute-solvent over solute-solute and solvent-solvent interactions, maximizing entropy by dispersing solute particles. Exceptions occur under high pressure or temperature, where miscibility deviates, as seen in partially miscible liquids like water and hexane at ambient conditions.[8] Thermodynamically, solvation is driven by the Gibbs free energy change ΔG_solv = ΔH_solv - TΔS_solv, where negative ΔG_solv indicates spontaneity; ΔH_solv reflects net enthalpic interactions, often negative for exothermic solvation, while ΔS_solv captures configurational entropy gains from mixing, tempered by solvent ordering around solutes (negative for hydrophobic effects).[7] For nonpolar solutes in water, ΔH_solv is near zero but ΔS_solv is negative due to structured water cages, rendering dissolution endergonic; in contrast, polar solvents yield favorable ΔG_solv for matching solutes.[9] Experimental solvation free energies, measured via transfer from gas to solution phases, quantify these effects, with values like -6.3 kcal/mol for Na+ hydration underscoring ion-solvent binding strength.[10]Classifications

Polarity Scales

Solvent polarity is quantified through various scales that assess the capacity for dipole-dipole, hydrogen bonding, and other electrostatic interactions, which dictate solubility, partitioning, and reaction kinetics in solution. Physical parameters like the static dielectric constant (ε_r) measure the solvent's ability to screen electric fields, with nonpolar solvents such as hexane exhibiting ε_r ≈ 1.9 and polar ones like water reaching ε_r = 78.5 at 25°C; however, ε_r conflates polarity with polarizability and is less predictive for specific solute-solvent interactions. The dipole moment (μ), determined via spectroscopy or computation, reflects intrinsic molecular asymmetry, e.g., μ = 0 D for nonpolar hexane versus μ = 1.85 D for acetone. These bulk properties correlate imperfectly with empirical behaviors, prompting the development of solvatochromic and interaction-specific scales.[11][12] Empirical polarity scales, derived from spectroscopic probes or thermodynamic measurements, offer refined metrics by isolating interaction types. Reichardt's E_T(30) scale, based on the charge-transfer absorption of a zwitterionic betaine dye, normalizes polarity from 0.000 (tetramethylsilane) to 1.000 (water), capturing solvatochromic shifts sensitive to both nonspecific dipolar forces and hydrogen bonding; for instance, ethanol scores 0.654. The Kamlet-Taft framework decomposes effects into π* (dipolarity/polarizability, e.g., 0.00 for alkanes to 1.10 for dimethyl sulfoxide), α (H-bond donation, e.g., 0.00 for aprotic solvents to 1.00+ for strong acids), and β (H-bond acceptance, e.g., 0.00 for nonbasic solvents to 0.88 for hexamethylphosphoramide), enabling linear solvation energy relationship (LSER) modeling of processes like extraction or catalysis. Snyder's P' index, from gas-liquid partition coefficients of probe solutes, ranks solvents linearly from 0.0 (hexane) to 10.2 (water), emphasizing eluotropic strength in chromatography. Gutmann's donor number (DN, kcal/mol) gauges Lewis basicity via calorimetric SbCl_5 adduct formation (e.g., 0 for water, 38.8 for pyridine), while the acceptor number (AN) uses ³¹P NMR shifts of triethylphosphine oxide (e.g., 0 for hexane, 100 for SbCl_5 reference), highlighting acid-base coordination.[11][13][14][15][16]| Solvent | ε_r (25°C) | μ (D) | P' | E_T(30) | π* | DN (kcal/mol) | AN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.009 | -0.08 | ~0 | 0 |

| Diethyl ether | 4.3 | 1.15 | 2.8 | 0.320 | 0.27 | 19.2 | 3.9 |

| Acetone | 20.7 | 2.88 | 5.1 | 0.355 | 0.71 | 17.0 | 12.5 |

| Ethanol | 24.5 | 1.69 | 4.3 | 0.654 | 0.54 | 32.0 | 37.9 |

| Water | 78.5 | 1.85 | 10.2 | 1.000 | 1.09 | 18 (ref.) | 54.8 |

Protic and Aprotic Distinctions

Protic solvents are defined as those capable of acting as hydrogen bond donors due to the presence of O-H or N-H bonds, where the hydrogen atom is attached to an electronegative atom such as oxygen or nitrogen.[2] This property arises from the partial positive charge on the hydrogen, enabling it to interact with electron-rich species like anions or lone pairs on other molecules.[2] Common examples include water (H₂O), methanol (CH₃OH), ethanol (C₂H₅OH), and ammonia (NH₃), which exhibit strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding leading to higher boiling points compared to structurally similar non-hydrogen-bonding compounds.[17] In protic solvents, anions are heavily solvated through hydrogen bonding networks, which stabilizes charged species but can diminish the reactivity of nucleophiles by encasing them in solvent shells.[18] Aprotic solvents, in contrast, lack O-H or N-H bonds and thus cannot donate hydrogen bonds, though polar aprotic solvents may still accept hydrogen bonds or solvate cations via dipole interactions.[2] This absence results in weaker solvation of anions, leaving them more free or "naked" and enhancing their nucleophilicity and basicity relative to protic environments.[18] Typical polar aprotic solvents include acetone (CH₃COCH₃), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, (CH₃)₂SO), dimethylformamide (DMF, HCON(CH₃)₂), and acetonitrile (CH₃CN), which possess high dielectric constants (e.g., DMSO at 47, acetone at 21) but do not form hydrogen bonds as donors.[2] Nonpolar aprotic solvents, such as hexane or benzene, further lack significant polarity but share the defining aprotic trait.[17] The primary distinction between protic and aprotic solvents manifests in their influence on reaction mechanisms, particularly nucleophilic substitutions and eliminations.[19] Protic solvents stabilize transition states involving carbocations or separated ion pairs via hydrogen bonding to leaving groups and anions, thereby favoring unimolecular mechanisms like SN1 and E1, as observed in solvolysis reactions where the solvent itself acts as the nucleophile (e.g., tert-butyl bromide in water).[19] [18] Conversely, aprotic solvents promote bimolecular pathways (SN2 and E2) by minimally solvating nucleophiles, increasing their effective concentration and attack rate on substrates; for instance, the rate of SN2 reactions with iodide ions can increase dramatically in acetone compared to ethanol.[18] This differential solvation also affects nucleophile ordering: in protic media, larger anions like iodide are more nucleophilic than smaller ones like fluoride due to less tight solvation, whereas aprotic solvents reverse this, making smaller anions more reactive.[20]| Aspect | Protic Solvents | Aprotic Solvents |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding | Can donate (O-H, N-H present) | Cannot donate (no O-H, N-H) |

| Anion Solvation | Strong via H-bonds; reduces nucleophilicity | Weak; enhances nucleophilicity |

| Favored Mechanisms | SN1, E1 (carbocation stabilization) | SN2, E2 (nucleophile activation) |

| Examples | H₂O, CH₃OH, C₂H₅OH, NH₃ | Acetone, DMSO, DMF, CH₃CN |

Physical Properties

Thermodynamic Characteristics

The enthalpy of vaporization, ΔH_vap, represents the heat absorbed during the phase transition from liquid to vapor at constant pressure, a critical parameter for assessing solvent volatility and energy requirements in evaporation processes. For many organic solvents, ΔH_vap at the normal boiling point falls between 25 and 45 kJ/mol, influenced by intermolecular forces; non-polar solvents like hexane exhibit lower values around 31.7 kJ/mol, while protic solvents such as ethanol show higher values of approximately 38.6 kJ/mol due to hydrogen bonding.[21][22] These enthalpies decrease with temperature, following the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, which relates vapor pressure to ΔH_vap and enables prediction of boiling points under varying conditions.[23] The standard molar entropy of vaporization, ΔS_vap, at the normal boiling point adheres approximately to Trouton's rule for non-associated solvents, yielding values near 85–88 J/mol·K, indicative of comparable increases in molecular freedom during vaporization.[24] This empirical relation holds well for aprotic solvents like diethyl ether (ΔS_vap ≈ 87 J/mol·K) but deviates positively for hydrogen-bonded solvents such as water (≈109 J/mol·K) or acetic acid, where structured liquid phases contribute additional entropy gain upon breaking associations.[25] Such deviations underscore causal links between molecular interactions and thermodynamic behavior, with lattice models attributing the baseline to balanced attractive-repulsive potentials in non-polar liquids.[26] Critical temperature (T_c) and critical pressure (P_c) mark the endpoints of the vapor-liquid coexistence curve, beyond which solvents enter a supercritical state with gas-like diffusivity and liquid-like solvating power. For typical solvents, T_c ranges from 100°C for low-boiling hydrocarbons like pentane (T_c = 196.5°C, P_c = 33.7 bar) to over 300°C for higher alcohols like butanol (T_c ≈ 295°C, P_c ≈ 44 bar), with P_c generally 30–50 bar.[27] These parameters dictate solvent usability in high-pressure applications, as exceeding T_c precludes phase distinction regardless of pressure.[28]| Solvent | ΔH_vap (kJ/mol) | ΔS_vap (J/mol·K) | T_c (°C) | P_c (bar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone | 31.3 | ≈86 | 235.0 | 47.0 |

| Ethanol | 38.6 | ≈110 | 240.8 | 61.4 |

| Hexane | 31.7 | ≈86 | 234.2 | 30.3 |

| Dichloromethane | 28.1 | ≈87 | 96.7 | 59.6 |

Solubility Parameters

The Hildebrand solubility parameter, denoted as δ, quantifies a solvent's cohesive energy density and serves as an indicator of solvency behavior, with the principle that solvents and solutes with similar δ values exhibit mutual solubility.[29] It is calculated as δ = √(ΔE_v / V_m), where ΔE_v represents the molar energy of vaporization and V_m the molar volume, typically yielding values in MPa^{1/2}.[29] This parameter, introduced by Joel H. Hildebrand in the 1930s, effectively predicts miscibility for nonpolar systems but shows limitations with polar or hydrogen-bonding interactions, as it aggregates all intermolecular forces into a single scalar value.[30] To overcome these shortcomings, Charles M. Hansen developed the Hansen solubility parameters (HSP) in 1967, decomposing δ into three orthogonal components reflecting distinct interaction types: δ_d for dispersion (van der Waals) forces, δ_p for polar (dipole-dipole) forces, and δ_h for hydrogen bonding (electron donor-acceptor) forces.[31] The total Hildebrand parameter relates to these via δ = √(δ_d² + δ_p² + δ_h²), maintaining compatibility with the original framework.[31] HSP values are determined experimentally through solubility tests or group contribution methods, with units in MPa^{1/2}. Solubility prediction using HSP employs a three-dimensional "solubility sphere" model, where a solute's parameters define a center point and interaction radius R_0, derived from empirical solubility data against reference solvents.[31] The relative distance Ra between solvent and solute coordinates is computed as Ra = √[4(δ_d,s - δ_d,t)² + (δ_p,s - δ_p,t)² + (δ_h,s - δ_h,t)²], where subscripts s and t denote solvent and test material, respectively; solubility occurs if Ra < R_0, or equivalently if the relative energy difference RED = Ra / R_0 < 1.[31] This approach enhances accuracy for complex systems, such as polymer dissolution or pigment dispersion, by weighting dispersion differences more heavily (factor of 4) to account for their ubiquity.[31] For solvent blends, HSP are averaged by volume fractions, enabling tailored formulations.[31]| Solvent | δ_d (MPa^{1/2}) | δ_p (MPa^{1/2}) | δ_h (MPa^{1/2}) | δ (MPa^{1/2}) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Hexane | 14.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.9 |

| Diethyl ether | 15.1 | 2.9 | 4.4 | 15.9 |

| Acetone | 15.5 | 10.4 | 7.0 | 19.9 |

| Ethanol | 15.8 | 8.8 | 19.4 | 26.5 |

| Water | 15.5 | 16.0 | 42.3 | 47.8 |

Chemical Properties

Reactivity and Stability

Solvents display a spectrum of chemical reactivity and stability influenced by molecular structure, environmental conditions, and exposure to reactive agents. Many organic solvents remain inert at ambient temperatures and pressures, facilitating their use in dissolving solutes without participating in reactions; however, stability diminishes under extremes like elevated temperatures, ultraviolet light, or contact with oxidants, acids, or bases.[34] Empirical data from laboratory safety protocols indicate that nonpolar solvents such as hydrocarbons exhibit high thermal stability, with boiling points and decomposition temperatures often exceeding 200°C, whereas polar solvents may undergo hydrolysis or thermal breakdown at lower thresholds.[35] A prominent instability arises in ether-based solvents through autoxidation, forming explosive peroxides upon prolonged exposure to atmospheric oxygen, particularly under light or heat catalysis. Diethyl ether and tetrahydrofuran, for instance, generate hydroperoxides that concentrate during distillation or evaporation, posing detonation risks from shock or friction; safety guidelines recommend testing for peroxides via colorimetric assays and discarding solvents after 3-12 months of storage, depending on the ether type.[34][36] This reactivity stems from the weak alpha C-H bonds in ethers, enabling radical chain propagation: initiation by trace metals or light abstracts hydrogen, propagation adds oxygen to form peroxy radicals, and termination yields peroxides.[34] Halogenated solvents demonstrate reactivity via dehydrohalogenation or reductive elimination, often triggered thermally or photolytically. Chloroform (CHCl₃) decomposes above 400°C into hydrogen chloride and dichlorocarbene (:CCl₂), a reactive intermediate used in synthesis but hazardous in uncontrolled conditions; in the presence of oxygen or moisture, it can further yield phosgene (COCl₂), a toxic gas, emphasizing the need for stabilizers like ethanol in commercial formulations.[37] Similarly, dichloromethane resists mild conditions but reacts explosively with alkali metals or under UV light to form carbenes.[38] Polar aprotic solvents like N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) offer enhanced stability toward nucleophiles and electrophiles due to the absence of labile protons, maintaining integrity in reactions up to 150-200°C; however, DMF hydrolyzes under acidic or basic catalysis to dimethylamine and formic acid, while DMSO oxidizes to dimethyl sulfone with strong oxidants.[39] These behaviors underscore causal dependencies on functional groups: carbonyls in amides confer resistance to oxidation but vulnerability to hydrolysis, whereas sulfoxides balance polarity with moderate thermal endurance. Storage under inert atmospheres and compatibility testing mitigate risks across solvent classes.[35]Applications

Industrial Processes

Solvents are integral to numerous industrial processes, particularly in extraction, cleaning, degreasing, and product formulation, where they facilitate the dissolution, separation, or dispersion of substances.[40] In manufacturing sectors such as chemicals, paints, and metals, organic solvents like hydrocarbons and chlorinated compounds dissolve contaminants or resins, enabling efficient material handling and processing.[41] Global solvent demand reached approximately $38.6 billion in 2024, driven largely by these applications, with projections for growth to $61.95 billion by 2032 at a 6.1% CAGR, reflecting their indispensable role despite environmental pressures for recovery and alternatives.[42] Solvent extraction is a primary process in the food and chemical industries, where solvents selectively dissolve target compounds from solid or liquid matrices. In vegetable oil production, hexane is commonly employed to percolate through flaked oilseeds like soybeans, extracting up to 99% of the oil by diffusion into cellular structures at temperatures near the solvent's boiling point, followed by distillation to recover both oil and solvent.[43] This method dominates global edible oil refining, processing millions of tons annually, as it achieves higher yields than mechanical pressing alone.[44] In hydrometallurgy, solvents such as kerosene-diluted extractants separate metals like uranium or copper from leach solutions via liquid-liquid partitioning, enabling purification at scales exceeding thousands of tons per facility.[45] Industrial cleaning and degreasing rely on solvents to remove oils, greases, and residues from metal parts and equipment, preventing corrosion and ensuring assembly integrity. Chlorinated solvents like trichloroethylene or non-chlorinated alternatives such as n-propyl bromide are vapor-degreased in enclosed systems, where parts are immersed or exposed to boiling solvent vapors that condense and dissolve contaminants before draining back.[46] This process is prevalent in aerospace and automotive manufacturing, handling components with tolerances under 0.01 mm, and consumes significant volumes—organic solvents account for a substantial portion of the $10 billion U.S. industrial solvents market in 2024.[47] Recovery techniques, including distillation, reclaim up to 95% of used solvents in closed-loop systems to minimize waste.[48] In paints and coatings production, solvents adjust viscosity, dissolve binders like alkyd resins, and aid application by enabling brushability or sprayability before evaporating to form durable films. Aromatic hydrocarbons such as toluene or xylene comprise 20-50% of solvent-based formulations, supporting a market segment valued at over $41 billion globally in 2024.[49] These processes occur in high-volume batch or continuous reactors, where solvents are mixed under controlled temperatures (typically 20-60°C) to prevent premature polymerization, followed by filtration and packaging.[50] Transition to water-based systems has reduced solvent use by 30-50% in some formulations since the 1990s, but solvent-based variants persist for high-performance applications like automotive primers due to superior penetration and drying control.[40]Laboratory and Pharmaceutical Uses

In organic chemistry laboratories, solvents enable key operations such as dissolving reactants for synthesis, performing liquid-liquid extractions, recrystallizations for purification, and mobile phases in chromatography.[51] Dichloromethane (CH₂Cl₂) is frequently employed for extractions due to its higher density than water (1.33 g/mL), facilitating phase separation, and its boiling point of 40°C, which allows easy removal post-extraction. [51] Chloroform and diethyl ether serve similar roles in extractions, though ether's high flammability limits its use in reactions involving oxidants. Acetone functions as a versatile solvent for cleaning glassware and dissolving polar compounds in reactions, with its miscibility in water and low cost contributing to widespread adoption.[52] Tetrahydrofuran (THF) and dimethylformamide (DMF) are staples in organometallic reactions and amide formations, respectively, owing to their ability to solvate cations and stabilize transition states.[51] In analytical laboratories, solvents like acetonitrile underpin high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for separating compounds based on polarity differences.[53] Ethanol and methanol support spectroscopic analyses by dissolving samples without interfering absorption in UV-Vis or NMR ranges.[54] In pharmaceutical applications, solvents act as reaction media during active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis, aids in extraction and purification of natural products, and vehicles in formulation for oral, topical, and injectable dosage forms.[55] [56] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) categorizes residual solvents by toxicity: Class 1 (e.g., benzene, avoided due to carcinogenicity); Class 2 (e.g., dichloromethane, limited to 6000 ppm daily exposure); and Class 3 (e.g., ethanol, acetone, acceptable without limits as they pose negligible risk).[53] Isopropyl alcohol extracts bioactive compounds from plants, while propylene glycol solubilizes APIs in syrups and creams to enhance bioavailability.[54] [57] In crystallization, solvents like methanol control polymorph formation, critical for drug stability and efficacy, as seen in the purification of antibiotics where solvent choice influences yield and purity above 99%.[58] Residual solvent levels are monitored via gas chromatography to comply with ICH Q3C guidelines, ensuring levels below permissible daily exposures for patient safety.[53]Advanced Solvent Systems

Multicomponent Mixtures

Multicomponent solvent mixtures, comprising three or more distinct solvents, enable precise tuning of physicochemical properties such as solubility parameters, viscosity, and dielectric constants, which are often unattainable with binary or single-component systems. These mixtures exploit synergistic interactions to expand the solvency range, facilitating the dissolution of complex solutes in applications where pure solvents fall short. Thermodynamic modeling of such systems relies on approaches like excess Gibbs free energy expressions to predict solubility, accounting for non-ideal behaviors arising from molecular interactions.[59][60] In industrial contexts, multicomponent mixtures are employed to optimize extraction and transport processes, particularly in heavy oil recovery where diluents are blended with bitumen to reduce viscosity. Experimental data show that varying diluent concentrations from 7 to 70 wt% in such mixtures decreases density linearly while viscosity drops exponentially, improving flow properties for pipeline transport. These systems require correlations for properties like K-values and solubility to predict phase behavior under reservoir conditions.[61][62] Advanced multicomponent systems, including deep eutectic solvents formed by hydrogen bond donors and acceptors (e.g., choline chloride-urea mixtures), exhibit depressed melting points and tunable thermal stability, making them suitable for reaction media in multicomponent syntheses. Their physicochemical properties, such as low volatility and high solvency, can be adjusted by component ratios, enhancing efficiency in processes like organic transformations. However, challenges persist in predictive modeling due to limited datasets, necessitating machine learning integrations for generalizable solubility forecasts across diverse compositions.[63][60] In pharmaceutical production, multicomponent solvent blends support drug formulation by accommodating varied boiling points and solubilities during synthesis and recovery, with distillation systems designed to handle azeotropic behaviors in mixtures like ethanol-water-acetone. Such applications underscore the economic viability of solvent mixtures in broadening parameter optimization without introducing entirely new compounds.[64]Green and Bio-Based Solvents

Green solvents encompass substances engineered to diminish adverse environmental and health effects relative to conventional petroleum-derived options, prioritizing attributes such as renewability, biodegradability, low toxicity, and reduced volatility.[65] These solvents aim to mitigate issues like volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions and persistent pollution through strategies including emission avoidance and substitution of hazardous alternatives, though comprehensive life-cycle assessments reveal that not all purportedly "green" options achieve net reductions in impact without contextual evaluation.[66] Bio-based solvents, a prominent subcategory, derive from renewable biomass feedstocks like agricultural crops or lignocellulosic materials, enabling compatibility with existing processes while curbing dependence on non-renewable petrochemicals.[67] Prominent examples include ethanol, obtained via microbial fermentation of edible or non-edible sugars, which stands as the most abundantly produced bio-solvent globally due to its versatility in extractions and reactions.[68] Other bio-based variants encompass ethyl lactate from lactic acid fermentation, dihydrolevoglucosenone (Cyrene) from cellulose-derived levoglucosenone, and 2,5-dimethyltetrahydrofuran from biomass sugars, each exhibiting aprotic or ethereal properties suitable for replacing toxic solvents like N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone or tetrahydrofuran.[69] [70] These solvents often demonstrate comparable solvency to fossil counterparts, with empirical studies confirming higher extraction yields for compounds like β-carotene in bio-based mixtures versus traditional hexane.[71] Advantages of bio-based solvents include inherent biodegradability—many degrade via natural microbial pathways—and lower acute toxicity profiles, reducing occupational hazards in industrial applications such as coatings and pharmaceuticals.[72] For instance, Cyrene supports supramolecular gel formation without the neurotoxic risks of dimethyl sulfoxide, while 2,5-dimethyltetrahydrofuran offers stability under aprotic conditions with a boiling point of 98°C, facilitating energy-efficient recovery.[69] [70] However, production scalability remains constrained by feedstock competition with food supplies and higher upfront energy demands in some cases, necessitating process optimizations for economic viability; claims of universal "greenness" overlook such trade-offs absent rigorous environmental accounting.[73] Ongoing research emphasizes hybrid systems, like bio-based entrainers in extractive distillation, to enhance separation efficiency for platform chemicals such as isobutyl acetate.[74]In practice, bio-based solvents have facilitated sustainable recoveries, as in the use of novel biogenic options for bacterial polyester extraction, yielding purities comparable to chloroform while minimizing waste via ethanol anti-solvent precipitation.[75] Selection guides for these solvents prioritize metrics like Hansen solubility parameters and partition coefficients to ensure efficacy in acid recoveries, underscoring the need for empirical validation over anecdotal endorsements.[76] Despite promotional narratives, systemic assessments indicate that while bio-based options lower direct emissions, full sustainability hinges on integrated process design rather than solvent substitution alone.[77]