Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The Gold-Bug

View on Wikipedia

| "The Gold-Bug" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Edgar Allan Poe | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Short story |

| Publication | |

| Published in | Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper |

| Media type | Print (Periodical) |

| Publication date | June 21, 1843 |

"The Gold-Bug" is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe published in 1843. The plot follows William Legrand, who becomes fixated on an unusual gold-colored bug he has discovered. His servant Jupiter fears that Legrand is going insane and goes to Legrand's friend, an unnamed narrator, who agrees to visit his old friend. Legrand pulls the other two into an adventure after deciphering a secret message that will lead to a buried treasure.

The story, set on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, is often compared with Poe's "tales of ratiocination" as an early form of detective fiction. Poe became aware of the public's interest in secret writing in 1840 and asked readers to challenge his skills as a code-breaker. He took advantage of the popularity of cryptography as he was writing "The Gold-Bug", and the success of the story centers on one such cryptogram. Modern critics have judged the characterization of Legrand's servant Jupiter as racist, especially because of his dialect speech.

Poe submitted "The Gold-Bug" as an entry to a writing contest sponsored by the Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper. His story won the grand prize and was published in three installments, beginning in June 1843. The prize also included $100 (equivalent to $3,375 in 2024), probably the largest single sum that Poe received for any of his works. An instant success, "The Gold-Bug" was the most popular and widely read of Poe's prose works during his lifetime. It also helped popularize cryptograms and secret writing.

Plot

[edit]

After losing his family fortune, William Legrand has relocated from New Orleans to a remote cabin on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, along with his African-American servant Jupiter. The story's narrator, Legrand's friend, visits him one evening and Legrand tells him of an unusual scarab-like beetle ('bug') he has collected that day. Legrand has lent it to an officer stationed at nearby Fort Moultrie, but he draws a sketch of it and notes that its markings resemble a skull. When the narrator queries the accuracy of the drawing, Legrand becomes withdrawn and carefully locks it in his desk for safekeeping. Confused, the narrator takes his leave.

A month later, Jupiter visits the narrator and asks him to come to the cabin immediately. When they arrive, Legrand insists that the bug will be the key to restoring his lost fortune. Refusing to explain, he leads them on a night expedition to a prominent tree on the mainland, and has Jupiter climb it until he finds a skull nailed at the end of one branch. At Legrand's direction, Jupiter drops the bug through one eye socket, and Legrand lays out a line extending between the tree and the point at which the bug landed. Measuring a distance of fifty feet, he marks a spot and they begin to dig. After laboring for several hours and finding nothing, Legrand questions Jupiter and discovers that he had mistakenly dropped the bug through the skull's right eye socket rather than the left, resulting in the bug landing a few inches from where it should. He corrects the point, measures out a new distance of fifty feet, and the group dig at the new location. There, they unearth two skeletons and a chest packed with valuable gold coins and jewelry.

Legrand explains that on the day he found the bug, Jupiter had picked up a nearby scrap of parchment to wrap it in. Legrand kept the scrap and used it to sketch the bug. The narrator had been looking not at his sketch but at a rather similar image of a skull on the other side of the sheet, an image in invisible ink that was not initially visible but which was revealed by the heat of the fire burning on the hearth. Later study of the parchment showed it to contain a substitution cipher, which Legrand deciphered as a set of directions for finding treasure buried by the pirate Captain Kidd. He explains his working method in some detail. Legrand muses that the skeletons found with the treasure may be the remains of two members of Kidd's crew, who had buried the chest and were then killed to silence them.

Analysis

[edit]"The Gold-Bug" includes a simple substitution cipher. Though he did not invent "secret writing" or cryptography (he was probably inspired by an interest in Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe[1]), Poe certainly popularized it during his time. To most people in the 19th century, cryptography was mysterious and those able to break the codes were considered gifted with nearly supernatural ability.[2] Poe had drawn attention to it as a novelty over four months in the Philadelphia publication Alexander's Weekly Messenger in 1840. He had asked readers to submit their own substitution ciphers, boasting he could solve all of them with little effort.[3] The challenge brought about, as Poe wrote, "a very lively interest among the numerous readers of the journal. Letters poured in upon the editor from all parts of the country."[4] In July 1841, Poe published "A Few Words on Secret Writing"[5] and, realizing the interest in the topic, wrote "The Gold-Bug" as one of the few pieces of literature to incorporate ciphers as part of the story.[6] Poe's character Legrand's explanation of his ability to solve the cipher is very like Poe's explanation in "A Few Words on Secret Writing".[7]

The actual "gold-bug" in the story is not a real insect. Instead, Poe combined characteristics of two insects found in the area where the story takes place. The Callichroma splendidum, though not technically a scarab but a species of longhorn beetle (Cerambycidae), has a gold head and slightly gold-tinted body. The black spots noted on the back of the fictional bug can be found on the Alaus oculatus, a click beetle also native to Sullivan's Island.[8]

Poe's depiction of the African servant Jupiter is often considered stereotypical and racist. Jupiter is depicted as superstitious and so lacking in intelligence that he cannot tell his left from his right.[9] Poe scholar Scott Peeples summarizes Jupiter, as well as Pompey in "A Predicament", as a "minstrel-show caricature".[10] Leonard Cassuto, who called Jupiter "one of Poe's most infamous black characters", emphasizes that the character has been manumitted but refuses to leave the side of his "Massa Will". He sums up Jupiter by noting, he is "a typical Sambo: a laughing and japing comic figure whose doglike devotion is matched only by his stupidity".[11] Poe probably included the character after being inspired by a similar one in Sheppard Lee (1836) by Robert Montgomery Bird, which he had reviewed.[12] Black characters in fiction during this time period were not unusual, but Poe's choice to give him a speaking role was. Critics and scholars, however, question if Jupiter's accent was authentic or merely comic relief, suggesting it was not similar to accents used by blacks in Charleston but possibly inspired by Gullah.[13]

Though the story is often included amongst the short list of detective stories by Poe, "The Gold-Bug" is not technically detective fiction because Legrand withholds the evidence until after the solution is given.[14] Nevertheless, the Legrand character is often compared to Poe's fictional detective C. Auguste Dupin[15] due to his use of "ratiocination".[16][17][18] "Ratiocination", a term Poe used to describe Dupin's method, is the process by which Dupin detects what others have not seen or what others have deemed unimportant.[19]

Publication history and reception

[edit]

Poe wrote the short story in Philadelphia, where he resided at various locations from 1838 to 1844.[20][21]

Poe originally sold "The Gold-Bug" to George Rex Graham for Graham's Magazine for $52 (equivalent to $1,755 in 2024) but asked for it back when he heard about a writing contest sponsored by Philadelphia's Dollar Newspaper.[22] Incidentally, Poe did not return the money to Graham and instead offered to make it up to him with reviews he would write.[23] Poe won the grand prize; in addition to winning $100, the story was published in two installments on June 21 and June 28, 1843, in the newspaper.[24] His $100 payment from the newspaper may have been the most he was paid for a single work.[25] Anticipating a positive public response, the Dollar Newspaper took out a copyright on "The Gold-Bug" prior to publication.[26]

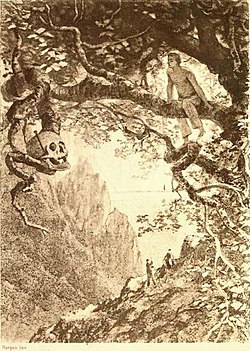

The story was republished in three installments in the Saturday Courier in Philadelphia on June 24, July 1, and July 8; the last two appeared on the front page and included illustrations by F. O. C. Darley.[27] Further reprintings in United States newspapers made "The Gold-Bug" Poe's most widely read short story during his lifetime.[24] By May 1844, Poe reported that it had circulated 300,000 copies,[28] though he was probably not paid for these reprints.[29] It also helped increase his popularity as a lecturer. One lecture in Philadelphia after "The Gold-Bug" was published drew such a large crowd that hundreds were turned away.[30] As Poe wrote in a letter in 1848, it "made a great noise."[31] He would later compare the public success of "The Gold-Bug" with "The Raven", though he admitted "the bird beat the bug".[32]

The Public Ledger in Philadelphia called it "a capital story".[26] George Lippard wrote in the Citizen Soldier that the story was "characterised by thrilling interest and a graphic though sketchy power of description. It is one of the best stories that Poe ever wrote."[33] Graham's Magazine printed a review in 1845 which called the story "quite remarkable as an instance of intellectual acuteness and subtlety of reasoning".[34] Thomas Dunn English wrote in the Aristidean in October 1845 that "The Gold-Bug" probably had a greater circulation than any other American story and "perhaps it is the most ingenious story Mr. POE has written; but... it is not at all comparable to the 'Tell-tale Heart'—and more especially to 'Ligeia'".[35] Poe's friend Thomas Holley Chivers said that "The Gold-Bug" ushered in "the Golden Age of Poe's Literary Life".[36]

The popularity of the story also brought controversy. Within a month of its publication, Poe was accused of conspiring with the prize committee by Philadelphia's Daily Forum.[28] The publication called "The Gold-Bug" an "abortion" and "unmitigated trash" worth no more than $15 (equivalent to $506 in 2024).[37] Poe filed for a libel lawsuit against editor Francis Duffee. It was later dropped[38] and Duffee apologized for suggesting Poe did not earn the $100 prize.[39] Editor John Du Solle accused Poe of stealing the idea for "The Gold-Bug" from "Imogine; or the Pirate's Treasure", a story written by a schoolgirl named Miss Sherburne.[40]

"The Gold-Bug" was republished as the first story in the Wiley & Putnam collection of Poe's Tales in June 1845, followed by "The Black Cat" and ten other stories.[41] The success of this collection inspired[42] the first French translation of "The Gold-Bug", published in November 1845 by Alphonse Borghers in the Revue Britannique[43] under the title, "Le Scarabée d'or", becoming the first literal translation of a Poe story into a foreign language.[44] In the French version, the enciphered message remained in English, with a parenthesized translation supplied alongside its solution. The story was translated into Russian from that version two years later, marking Poe's literary debut in that country.[45] In 1856, Charles Baudelaire published his translation of the tale in the first volume of Histoires extraordinaires.[46] Baudelaire was very influential in introducing Poe's work to Europe and his translations became the definitive renditions throughout the continent.[47]

Influence

[edit]

"The Gold-Bug" inspired Robert Louis Stevenson in his novel about treasure-hunting, Treasure Island (1883). Stevenson acknowledged this influence: "I broke into the gallery of Mr. Poe... No doubt the skeleton [in my novel] is conveyed from Poe."[48]

"The Gold-Bug" also inspired Leo Marks to become interested in cryptography at age 8 when he found the book in his father’s bookshop at 84 Charing Cross Road.[citation needed] Marks would go on to lead Britain’s code-breaking efforts during World War Two as a member of the Special Operations Executive (SOE).[citation needed]

Poe played a major role in popularizing cryptograms in newspapers and magazines in his time period[2] and beyond. William F. Friedman, America's foremost cryptologist, initially became interested in cryptography after reading "The Gold-Bug" as a child—interest that he later put to use in deciphering Japan's PURPLE code during World War II.[49] "The Gold-Bug" also includes the first use of the term cryptograph (as opposed to cryptogram).[50]

Poe had been stationed at Fort Moultrie from November 1827 through December 1828 and utilized his personal experience at Sullivan's Island in recreating the setting for "The Gold-Bug".[51] It was also here that Poe first heard the stories of pirates like Captain Kidd.[52] The residents of Sullivan's Island embrace this connection to Poe and have named their public library after him.[53] Local legend in Charleston says that the poem "Annabel Lee" was also inspired by Poe's time in South Carolina.[54] Poe also set part of "The Balloon-Hoax" and "The Oblong Box" in this vicinity.[52]

O. Henry alludes to the stature of "The Gold-Bug" within the buried-treasure genre in his short story "Supply and Demand". One character learns that the main characters are searching for treasure, and he asks them if they have been reading Edgar Allan Poe. The title of Richard Powers' 1991 novel The Gold Bug Variations is derived from "The Gold-Bug" and from Bach's composition Goldberg Variations, and the novel incorporates part of the short story's plot.[55]

Adaptations

[edit]The story proved popular enough in its day that a stage version opened on August 8, 1843.[56] The production was put together by Silas S. Steele and was performed at the American Theatre in Philadelphia.[57] The editor of the Philadelphia newspaper The Spirit of the Times said that the performance "dragged, and was rather tedious. The frame work was well enough, but wanted filling up".[58]

In film and television, an adaptation of the work appeared on Your Favorite Story on February 1, 1953 (Season 1, Episode 4). It was directed by Robert Florey with the teleplay written by Robert Libott. A later adaptation of the work appeared on ABC Weekend Special on February 2, 1980 (Season 3, Episode 7). This version was directed by Robert Fuest with the teleplay written by Edward Pomerantz.[59] A Spanish feature film adaptation of the work appeared in 1983 under the title En busca del dragón dorado. It was written and directed by Jesús Franco using the alias "James P. Johnson".[60]

"The Gold Bug" episode on the 1980 ABC Weekend Special series starred Roberts Blossom as Legrand, Geoffrey Holder as Jupiter, and Anthony Michael Hall. It won three Daytime Emmy Awards: 1) Outstanding Children's Anthology/Dramatic Programming, Linda Gottlieb (executive producer), Doro Bachrach (producer); 2) Outstanding Individual Achievement in Children's Programming, Steve Atha (makeup and hair designer); and, 3) Outstanding Individual Achievement in Children's Programming, Alex Thomson (cinematographer). It was a co-production of Learning Corporation of America.[61]

In 2001, Gregory Evans adapted the story for a BBC Radio drama. Directed by Ned Chaillet, it told the story from Jupiter's point of view and presented him as the protagonist; he was played by Rhashan Stone. John Sharian played Legrand.[62]

References

[edit]- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 13

- ^ a b Friedman, William F. (1993), "Edgar Allan Poe, Cryptographer", On Poe: The Best from "American Literature", Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 40–41, ISBN 0-8223-1311-1

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 152

- ^ Hutchisson 2005, p. 112

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 61

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 2

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 6

- ^ Quinn 1998, pp. 130–131

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 206

- ^ Peeples, Scott. The Afterlife of Edgar Allan Poe. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2004: 97. ISBN 1-57113218-X

- ^ Cassutto, Leonard. The Inhuman Race: The Racial Grotesque in American Literature and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997: 160. ISBN 978-0-231-10336-7

- ^ Bittner 1962, p. 184

- ^ Weissberg, Liliane. "Black, White, and Gold", Romancing the Shadow: Poe and Race, J. Gerald Kennedy and Liliane Weissberg, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001: 140–141. ISBN 0-19-513711-6

- ^ Haycraft, Howard. Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1941: 9.

- ^ Hutchisson 2005, p. 113

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 130

- ^ Stashower 2006, p. 295

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 135

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 74

- ^ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906: 286. ISBN 1-932109-45-5

- ^ "Edgar Allan Poe House", The Constitutional Walking Tour, August 22, 2018

- ^ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906: 239.

- ^ Bittner 1962, p. 185

- ^ a b Sova 2001, p. 97

- ^ Hoffman, Daniel. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Louisiana State University Press, 1998: 189. ISBN 0-8071-2321-8

- ^ a b Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 419

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 392

- ^ a b Meyers 1992, p. 136

- ^ Hutchisson 2005, p. 186

- ^ Stashower 2006, p. 252

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 539

- ^ Hutchisson 2005, p. 171

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 420

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 567

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, pp. 586–587

- ^ Chivers, Thomas Holley. Life of Poe, Richard Beale Davis, ed. E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1952: 36.

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, pp. 419–420

- ^ Meyers 1992, pp. 136–137

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 421

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 422

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 540

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 298

- ^ Salines, Emily. Alchemy and Amalgam: Translation in the Works of Charles Baudelaire. Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi, 2004: 81–82. ISBN 90-420-1931-X

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 585

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 320

- ^ Salines, Emily. Alchemy and Amalgam: Translation in the Works of Charles Baudelaire. Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi, 2004: 82. ISBN 90-420-1931-X

- ^ Harner, Gary Wayne (1990), "Edgar Allan Poe in France: Baudelaire's Labor of Love", in Fisher IV, Benjamin Franklin (ed.), Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu, Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, p. 218, ISBN 0-9616449-2-3

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 291

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 146

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 20

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 98

- ^ a b Poe, Harry Lee. Edgar Allan Poe: An Illustrated Companion to His Tell-Tale Stories. New York: Metro Books, 2008: 35. ISBN 978-1-4351-0469-3

- ^ Urbina, Ian. "Baltimore Has Poe; Philadelphia Wants Him". The New York Times. September 5, 2008: A10.

- ^ Crawford, Tom. "The Ghost by the Sea Archived 2012-05-10 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ^ "Genetic Coding and Aesthetic Clues: Richard Powers's 'Gold Bug Variations.'". Mosaic. Winnipeg. December 1, 1998.[dead link]

- ^ Bittner 1962, p. 186

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 268

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 434

- ^ ""ABC Weekend Specials" The Gold Bug (1980)". IMDb.

- ^ IMDb: En busca del dragón dorado

- ^ The Gold Bug. IMDB.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 Extra - Edgar Allan Poe, The Gold Bug". BBC. Retrieved February 26, 2025.

Sources

[edit]- Bittner, William (1962), Poe: A Biography, Boston: Little, Brown and Company

- Hutchisson, James M. (2005), Poe, Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 1-57806-721-9

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1992), Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy, Cooper Square Press, ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1998), Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- Rosenheim, Shawn James (1997), The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-5332-6

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991), Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance, New York: Harper Perennial, ISBN 0-06-092331-8

- Sova, Dawn B. (2001), Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z, New York: Checkmark Books, ISBN 0-8160-4161-X

- Stashower, Daniel (2006), The Beautiful Cigar Girl: Mary Rogers, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Invention of Murder, New York: Dutton, ISBN 0-525-94981-X

- Thomas, Dwight; Jackson, David K. (1987), The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, 1809–1849, Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., ISBN 0-7838-1401-1

External links

[edit]- "The Gold-Bug" – Full text from the Dollar Newspaper, 1843 (with two illustrations by F. O. C. Darley)

- The Gold-Bug – Introduction to Cryptography – The story, how to solve it, and Poe's essay on secret writing, on Cipher Machines and Cryptology

- "The Gold-Bug" Archived April 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine from the University of Virginia Library

- The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 1 at Project Gutenberg — includes "The Gold-Bug"

- "The Gold-Bug" with annotated vocabulary at PoeStories.com

- Publication history of "The Gold-Bug" at the Edgar Allan Poe Society

- William B. Cairns (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

The Gold-Bug public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Gold-Bug public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Gold-Bug

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context

Poe's Life and Inspirations

In 1843, Edgar Allan Poe resided in Philadelphia amid ongoing financial difficulties, having resigned from his editorship at Graham's Magazine the previous year due to disputes over creative control and compensation.[8] Upon learning of a short-story contest announced by the Dollar Newspaper in March 1843, offering a $100 prize for the best original tale, Poe submitted "The Gold-Bug," tailoring it to appeal to popular tastes for adventure and mystery.[9] The story won the contest outright, with no other submissions deemed competitive enough, and was published in two parts on June 21 and June 28, 1843, providing Poe a rare financial windfall equivalent to several months' wages.[10] Poe's longstanding interest in cryptography directly informed the tale's central cipher mechanism, stemming from his early essays and public demonstrations of code-breaking. In July 1841, he published "A Few Words About Secret Writing" in Graham's Magazine, an article demystifying substitution ciphers and asserting that most were easily solvable through frequency analysis, while challenging readers to submit enigmas for solution.[11] Building on this, Poe solved dozens of reader-submitted cryptograms printed in Philadelphia's Alexander's Weekly Messenger starting in late 1840, earning acclaim for his methodical approach and fostering a public persona as a master decoder.[12] This expertise, honed without formal training but through self-study of historical treatises like those by Blaise de Vigenère, positioned cryptography as a rational pursuit amenable to scientific deduction, a theme echoed in "The Gold-Bug."[11] The narrative's buried treasure plot drew from persistent 19th-century legends surrounding pirate Captain William Kidd (c. 1645–1701), whose purported hoards fueled treasure-hunting frenzies along the American Atlantic coast, including unverified claims of caches in Sullivan's Island, South Carolina—the story's setting.[1] Poe, raised in Richmond, Virginia, after his adoption by merchant John Allan following his parents' deaths in 1811, absorbed Southern folklore rife with tales of hidden riches from colonial privateers, reflecting regional economic disparities where sudden wealth symbolized escape from agrarian constraints.[13] These motifs of concealed fortune aligned with Poe's broader intellectual pursuits in ratiocination, though no direct autobiographical link to personal treasure-seeking exists in his records.[1]Cryptography in the 19th Century

In the early 19th century, military cryptography during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) primarily utilized codebooks and nomenclators for secure dispatches, though these systems proved vulnerable to interception, as seen in French army codes that were compromised through captured documents and inadequate key distribution.[14][15] Polyalphabetic ciphers, such as the Vigenère system described by Giovan Battista Bellaso in 1553 and later attributed to Blaise de Vigenère, offered greater complexity than monoalphabetic substitutions but remained confined to professional military or diplomatic use, with limited dissemination beyond elite circles.[16] Formal cryptographic theory was sparse, lacking the systematic frameworks that would emerge later, and practices often depended on ad hoc innovations rather than standardized methods. By the 1830s and 1840s in the United States, civilian interest in cryptography surged through periodicals featuring substitution cipher puzzles in "enigma" or "secret writing" columns, reflecting a broader amateur fascination with intellectual challenges amid rising literacy and print culture.[17] These monoalphabetic ciphers, where each plaintext letter maps to a unique ciphertext symbol, dominated public engagement, as they were accessible yet intriguing for solvers without specialized training.[18] Poe positioned himself as a cryptanalytic authority by decoding reader-submitted ciphers in outlets like Alexander's Weekly Messenger from late 1839 to mid-1840, reportedly solving dozens with high accuracy and thereby elevating cryptanalysis from mere pastime to a display of rational deduction.[19] This era's cryptographic trends drew from Enlightenment rationalism, emphasizing empirical observation and logical inference, which paralleled the development of detective fiction where ciphers functioned as puzzles testing deductive prowess.[20] Frequency analysis—tabulating letter occurrences to infer substitutions, a technique originating with 9th-century Arab cryptologists—remained underutilized in popular solving until dramatized in literary works, bridging military secrecy with public intellectual pursuits and highlighting the gap between wartime polyalphabetics and civilian simplicities.[21] Such practices underscored causal realism in code-breaking, prioritizing probabilistic patterns over intuition alone, though systematic military advancements like rotor precursors did not influence amateur domains.[22]Narrative Structure

Plot Summary

The story is narrated by an unnamed friend of William Legrand, a descendant of a respectable Huguenot family who has fallen into poverty and withdrawn to a secluded hut on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, accompanied only by his elderly servant Jupiter.[23] In mid-October of an unspecified year in the early 1800s, Legrand captures an unusual gold-colored scarabaeus beetle during an excursion on the nearby mainland and becomes preoccupied with it, prompting the narrator's visit where Legrand sketches the insect on a scrap of parchment.[23] Upon heating the parchment near a fire, Legrand discovers invisible ink revealing a cipher alongside faint images of a death's-head and a goat, which he deciphers over the following month as directions to a buried pirate treasure linked to Captain Kidd.[23] Insisting on the cipher's authenticity despite the narrator's skepticism about his sanity, Legrand organizes an expedition with the narrator and Jupiter, traveling several miles northwest from Sullivan's Island to a large tulip tree on a hillock.[23] Jupiter ascends the tree under Legrand's instructions, locating a skull nailed to a limb and dropping a string with the beetle attached through its left eye-socket to mark a spot on the ground fifty feet distant.[23] After initial digging yields nothing due to an error in eye alignment, they adjust and unearth a massive iron chest containing gold coins worth over $450,000, numerous jewels including 110 diamonds, 18 rubies, 310 emeralds, and 21 sapphires, plus gold ornaments and additional scarabaeus-like bugs; the group estimates the total value at a million and a half dollars upon later appraisal and sale of the contents.[23]Characters and Their Roles

William Legrand functions as the central protagonist, embodying intellectual fervor and analytical precision that propel the narrative's investigative core. Descended from a Huguenot family that once enjoyed wealth but suffered reversals leading to seclusion on Sullivan's Island, Legrand pursues natural history with intense focus, evident in his enthusiastic advocacy for a rare beetle specimen, which he deems "the loveliest thing in creation."[23] His traits of enthusiasm alternating with melancholy, combined with artistic skill in sketching the insect, highlight a mind capable of rigorous deduction amid perceived eccentricity, driving the story through methodical problem-solving rather than mere whimsy.[24] Interactions with others reveal his irritation at doubted competence, as when he defends his drawing abilities, underscoring his role in challenging skeptical viewpoints to advance the tale's logic.[23] The unnamed narrator operates as a first-person chronicler and foil, providing an external lens of skepticism and concern that frames Legrand's actions with observational reliability. An accidental acquaintance residing in Charleston, the narrator documents Legrand's behaviors with curiosity tempered by worry over his companion's mental state, stating he "could scarcely refrain from tears" at signs of aberration.[23] This witnessing role, akin to rational observers in early detective fiction, validates the protagonist's processes post-facto and injects narrative tension through reluctant participation, ensuring the account's credibility without dominating the intellectual labor.[25] Jupiter, Legrand's elderly Black servant, supports the narrative via loyal physical aid and superstitious interjections that contrast the protagonist's rationality, offering comic relief and practical facilitation. Devoted yet cautious, Jupiter exhibits fearfulness toward omens like the beetle, protesting "Dey aint no tin in him" in dialect, which amplifies dramatic irony and underscores his function as an enabler of exertions rather than an intellectual peer.[23] His interactions with Legrand reveal deference mixed with protective anxiety, such as fretting over his master's health—"Ise gittin to be skeered"—thereby grounding the high-stakes inquiry in everyday human apprehensions without resolving its puzzles.[23]Cryptographic Analysis

The Cipher Mechanism

The cipher employed in "The Gold-Bug" utilizes a monoalphabetic substitution scheme, wherein numerals from 0 to 9 and various symbols replace individual letters of the English alphabet, encoded on a parchment via invisible ink that manifests under applied heat.[23][26] This construction draws on chemical agents, such as zaffre dissolved in aqua regia or regulus of cobalt in spirit of nitre, which render the inscription latent until exposed to fire, thereby revealing both the cipher text and ancillary diagrams.[23] The cipher text sequence spans 138 characters, commencing with "53‡‡†305))6*;" and incorporating elements like numbers, parentheses, semicolons, asterisks, daggers (†), double daggers (‡), and paragraph marks (¶), as follows:53‡‡†305))6*;4826)4‡.)4‡);806*;48†8¶60))85;1‡(;:‡*8†83(88)5*†;46(;88*96*?;8)*‡(;485);5*†2:*‡(;4956*2(5*-4)8¶8*;4069285);)6†8)4‡‡;1(‡9;48081;8:8‡1;48†85;4)485†528806*81(‡9;48;(88;4(‡?34;48)4‡;161;:188;‡?

53‡‡†305))6*;4826)4‡.)4‡);806*;48†8¶60))85;1‡(;:‡*8†83(88)5*†;46(;88*96*?;8)*‡(;485);5*†2:*‡(;4956*2(5*-4)8¶8*;4069285);)6†8)4‡‡;1(‡9;48081;8:8‡1;48†85;4)485†528806*81(‡9;48;(88;4(‡?34;48)4‡;161;:188;‡?

Solution Methods and Accuracy

In "The Gold-Bug," William Legrand deciphers the substitution cipher through frequency analysis, tallying symbol occurrences to correlate them with English letter frequencies—such as the most common symbol to 'e'—followed by pattern recognition for single-letter words likely representing 'a' or 'i', and iterative substitution using probable word forms like 'the'.[20] This approach mirrors verifiable 19th-century cryptanalytic practices, including those outlined in early treatises on secret writing, where letter counts and contextual guesses enabled breaking monoalphabetic ciphers without keys.[27] Legrand's process avoids reliance on trial-and-error alone, instead building deductions incrementally, such as confirming mappings via doublets (repeated symbols in words) that match English digrams like 'eg' in 'egg'.[19] The solution's fidelity to real principles underscores Poe's accurate portrayal of cryptanalysis as a rational, empirical exercise, demonstrating that most period ciphers—typically simple substitutions—yield to methodical scrutiny rather than remaining impervious to analysis, countering era-specific myths of inherently unbreakable codes.[20] Historical records confirm such techniques' efficacy; for instance, frequency-based attacks had succeeded against diplomatic ciphers decades earlier, though Poe's narrative popularized their accessibility to non-experts.[28] The story's decryption succeeds fully, yielding precise coordinates to treasure, which validates the method's practicality for the cipher type employed, though it presumes a ciphertext long enough for reliable statistics—around 300 symbols here, sufficient per contemporary standards. Poe's contributions extended beyond fiction; prior to "The Gold-Bug"'s 1843 publication, he solved approximately 100 reader-submitted ciphers in Alexander's Weekly Messenger from 1839–1840, claiming success on all but two deemed deliberately malformed, thereby disseminating these techniques and fostering public engagement with cryptanalysis decades before computational aids.[19] This presaged formal advancements in the field, emphasizing substitution vulnerabilities through first-hand examples that influenced subsequent amateur and professional code-breaking, without invoking supernatural elements often sensationalized elsewhere.[29]Themes and Motifs

Rational Inquiry and Obsession

In Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug," published in 1843, protagonist William Legrand's intense fixation on a rare gold-colored beetle initially appears as a symptom of mental derangement to the unnamed narrator, who attributes it to a combination of financial ruin and a supposed insect bite inducing feverish delusion.[1] Legrand's behavior—such as sketching the bug with exaggerated precision and insisting on its extraordinary value—prompts the narrator to fear a permanent loss of reason, yet this perceived madness proves illusory upon revelation.[1] Instead, Legrand's obsession channels into a methodical cryptographic analysis of a parchment uncovered during the bug's discovery, where invisible ink manifests a cipher under heat, directing him to Captain Kidd's buried treasure through precise navigational instructions.[1] Legrand's decoding process exemplifies empirical validation of rational deduction: employing frequency analysis to identify recurrent symbols corresponding to English letter patterns—such as the common word "the"—he translates the cipher into actionable coordinates, including a bearing of "twenty-one degrees and thirteen minutes northeast and by north" from a specific tree limb aligned with a skull's eye socket, culminating in the exhumation of a chest containing gold coins exceeding $450,000 in value, alongside jewels appraised at over $1 million.[1] This causal chain—from logical substitution cipher resolution to physical treasure recovery—demonstrates intellect's triumph over initial skepticism, as Poe underscores that no human-constructed code evades human analytical prowess, affirming the reliability of evidence-based inquiry in yielding concrete outcomes.[30] Contrasting Legrand's approach, his servant Jupiter embodies superstition, interpreting the beetle as a malevolent "goole-bug" omen responsible for Legrand's altered state and refusing to handle it due to unfounded fears of supernatural harm.[1] Jupiter's reliance on folklore—linking the insect to curses and ghostly perils—yields no progress, serving instead as a narrative foil that highlights the inefficacy of non-empirical beliefs against Legrand's precise measurements and deductions during the treasure hunt.[1] Poe thus illustrates causality in rational pursuit: superstition correlates with paralysis and error, while directed obsession, grounded in systematic reasoning, drives empirical success akin to methodical scientific endeavors, where persistent analysis uncovers hidden realities without succumbing to irrationality.[7]Social Hierarchies and Racial Portrayals

In Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug," published in 1843, the relationship between protagonist William Legrand and his enslaved servant Jupiter exemplifies antebellum Southern social hierarchies, with Legrand wielding unquestioned authority rooted in his family's former aristocratic status. Legrand, a member of a ruined Creole family from New Orleans, relocated to Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, where he maintains command over Jupiter, inherited as property from his kin, despite their shared poverty and isolation in a humble hut.[31] This dynamic underscores class distinctions persisting amid economic decline, as Legrand directs Jupiter's actions—such as foraging for the titular scarab—without negotiation, reflecting the legal and cultural norms of slavery where enslaved individuals served as extensions of their owners' will.[31] Jupiter's characterization emphasizes subservience tempered by loyalty and superstition, traits drawn from observable patterns in slavery-era accounts rather than invention. He expresses deference through phrases like "Massa Will" and complies with Legrand's eccentric pursuits, including climbing trees to retrieve the bug, while voicing fears of its "charmed" nature, which Legrand dismisses as folly.[31] Such portrayals align with historical records of enslaved Africans and African Americans retaining folk beliefs, including animistic interpretations of insects and omens, as documented in traveler narratives and early ethnographies from the antebellum South. Poe's narrative neither endorses nor challenges this hierarchy, presenting it as the unquestioned backdrop for the plot, consistent with the era's acceptance of racial and class stratification as natural order.[32] Poe renders Jupiter's dialogue phonetically to evoke 19th-century Southern African American speech patterns, employing substitutions like "dis" for "this," "dey" for "they," and elided consonants such as "gwine" for "going," which replicate documented vernacular features including th-stopping and consonant cluster reduction prevalent among enslaved populations isolated from standard English instruction.[31][33] This technique, common in period literature by authors like Joel Chandler Harris or contemporary dialect studies, aimed for verisimilitude based on auditory observations, not exaggeration, as phonetic analyses of slave-era speech confirm similar traits stemming from creolization processes during Atlantic enslavement.[32] The absence of subversive agency in Jupiter—contrasted with Legrand's intellectual dominance—mirrors causal realities of slavery's coercive structure, which incentivized compliance and suppressed literacy or autonomy, per empirical data from plantation records and post-emancipation testimonies.[34] While modern critiques often label these elements as stereotypical, textual evidence shows Poe's depictions hew to contemporaneous empirical observations of enslaved behaviors, including deference and superstition, without unique deviation from Southern literary conventions or advocacy for reform.[35] The story's fidelity to such dynamics prioritizes narrative realism over ideological imposition, as Legrand's eventual wealth restoration via the treasure implicitly reinforces hierarchical stability rather than upheaval.[31]Reception and Criticism

Initial Publication and Contemporary Response

"The Gold-Bug" was first published in the Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper on June 21, 1843, after Poe submitted it to the paper's writing contest offering a $100 prize for the best tale.[36] The story won first prize, leading to its serialization accompanied by woodcut illustrations.[1] The tale's cryptographic elements and treasure-hunt adventure garnered immediate praise for ingenuity, prompting the Dollar Newspaper to issue several reprints to meet public demand.[37] Poe later included it in his 1845 collection Tales, affirming its early commercial viability over purely artistic works.[38] Publication success dramatically increased the newspaper's reach, with Poe claiming a circulation of 300,000 copies in correspondence, marking it as his most widely disseminated story at the time.[39] This surge elevated Poe's visibility, spurring readers to submit personal ciphers to his periodical columns on enigmas, reflecting enthusiasm for the narrative's puzzle-solving mechanics.[9]Modern Interpretations and Controversies

Scholars in the late 20th and early 21st centuries have positioned "The Gold-Bug" as a foundational text in the development of detective fiction, with protagonist William Legrand's methodical ratiocination—solving the cipher through frequency analysis and logical deduction—serving as a prototype for later analytical detectives like Sherlock Holmes.[40] This interpretation highlights Poe's innovation in emphasizing empirical observation and inductive reasoning over supernatural elements, distinguishing the tale from gothic predecessors and influencing the genre's focus on intellectual puzzle-solving.[41] The story's cryptographic elements have drawn attention for their historical foresight, as the substitution cipher's decryption process mirrored techniques later formalized in modern cryptanalysis, including those employed by Allied codebreakers during World War II.[42] Information theorist Claude Shannon, a key figure in 20th-century cryptography, cited "The Gold-Bug" as a favorite, underscoring Poe's intuitive grasp of pattern recognition in encoded messages, which prefigured computational approaches to codebreaking without reliance on advanced machinery.[43] Controversies surrounding the tale center on the character of Jupiter, Legrand's enslaved Black servant, whose dialect-heavy speech and superstitious demeanor have been critiqued by left-leaning academics as perpetuating racial stereotypes and evidencing Poe's complicity in antebellum racism.[44] Such readings, prevalent in postcolonial and critical race scholarship, often frame Jupiter's loyalty and intellectual deference as dehumanizing tropes reflective of systemic white supremacy.[45] Counterarguments, grounded in historical contextualization, contend that Jupiter's portrayal aligns with conventional 19th-century literary depictions of enslaved characters by authors across the political spectrum, and Poe's oeuvre—lacking explicit pro-slavery polemics and including subversive tales like "Hop-Frog," where a marginalized figure exacts violent retribution against tyranny—suggests ambivalence rather than endorsement of racial hierarchies.[46] These defenses emphasize that anachronistic judgments overlook the era's normalized slavery and Poe's personal circumstances, including his Southern upbringing without documented ownership of slaves or overt abolitionist opposition.[47] Recent scholarship from the 2020s has shifted toward the story's scientific and cryptographic ingenuity, analyzing its embedded allusions to empirical methods like entomology and optics as prescient of interdisciplinary invention, while global adaptations underscore its rationalist appeal transcending cultural lenses.[48] This focus critiques ideologically driven interpretations for subordinating textual evidence to modern political priors, affirming the tale's enduring value in demonstrating causal chains of deduction over speculative moralizing.[49]Legacy and Influence

Impact on Literature and Detection Genres

"The Gold-Bug" advanced the integration of cryptographic puzzles into mystery and adventure fiction, establishing a template for narratives where rational deduction unlocks hidden treasures through code-breaking. Published in 1843, the story featured protagonist William Legrand's methodical deciphering of a cipher leading to Captain Kidd's purported hoard, a device that Poe had earlier popularized in his Dupin tales but here applied to non-criminal pursuit.[3] This innovation marked an early fusion of intellectual ratiocination with exploratory quests, distinguishing it from Poe's predominant Gothic elements and elevating the short story's capacity for embedded logical challenges.[50] The tale's emphasis on analytical problem-solving influenced the detective genre's evolution, particularly in Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes series, where cryptic clues and deductive reasoning became staples. Scholars note that "The Gold-Bug," often viewed as Poe's fourth ratiocination story despite lacking a traditional crime, shaped Doyle's approach to puzzle-driven detection in works like "The Adventure of the Dancing Men" (1903), which employs a substitution cipher akin to Legrand's parchment code.[51] Doyle himself acknowledged Poe's foundational role in the genre, with "The Gold-Bug" contributing to the archetype of the eccentric genius unraveling enigmas through superior intellect.[52] Beyond detection, the story's treasure-hunt structure, combining empirical observation with adventurous pursuit, prefigured hybrid rationality-adventure narratives in subsequent literature. It served as a prototype for tales like Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island (1883), which similarly romanticized pirate lore and map-based quests, drawing on the same Captain Kidd myths that Poe dramatized through cryptographic means.[6] Literary analyses position "The Gold-Bug" as an originator of this subgenre, enhancing short fiction's appeal by demanding reader engagement with verifiable logical processes over mere sensationalism.[53] This legacy persisted in modern puzzle mysteries, where embedded ciphers continue to drive plots centered on intellectual triumph.[54]Enduring Influence on Cryptanalysis

"The Gold-Bug" exerted a notable influence on the development of cryptanalytic practices by demonstrating practical methods for deciphering substitution ciphers, particularly through frequency analysis, which Legrand employs to decode the parchment's message. Published in 1843, the story's detailed exposition of identifying frequent letters—such as mapping the most common symbol to 'e' based on English letter distributions—contributed to public awareness of these techniques at a time when cryptography was gaining interest among amateurs and professionals.[28] This approach, rooted in empirical observation of linguistic patterns, underscored the vulnerabilities of simple monoalphabetic ciphers and helped shift perceptions of code-breaking from arcane esotericism to an accessible intellectual pursuit.[20] The narrative's impact extended to inspiring key figures in 20th-century cryptanalysis. Leo Marks, a British cryptographer who devised unbreakable codes for Special Operations Executive agents during World War II, credited an early encounter with "The Gold-Bug" as pivotal to his career. At age eight in 1927, Marks' father, an antiquarian bookseller, showed him a first edition of the story, igniting his fascination with ciphers and leading him to self-teach decryption methods that he later applied in wartime intelligence.[55] Similarly, William Friedman, a pioneering American cryptologist who trained analysts for both world wars, cited Poe's tale as his entry point into the field, influencing his foundational work on systematic code-breaking.[56] In academic settings, "The Gold-Bug" continues to serve as a pedagogical tool for illustrating cipher vulnerabilities. University courses in cryptography, such as those at the University of Texas at Austin and Queen Mary University of London, incorporate the story's cryptogram to teach frequency analysis and the limitations of substitution schemes, enabling students to replicate Legrand's step-by-step solution using historical texts.[57] [58] This enduring educational role reinforces the story's legacy in demystifying cryptanalysis, fostering skills in pattern recognition that remain relevant despite advances in computational methods. The tale's techniques also echo in modern recreational cryptology, including escape rooms where participants decode puzzles mimicking Poe's substitution cipher to "unlock" hidden elements, thereby perpetuating its cultural dissemination of code-solving principles.[20]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Dollar_The_Gold_Bug_1843.jpg