Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wandering Jew

View on Wikipedia

The Wandering Jew (occasionally referred to as the Eternal Jew, a translation of the German "der Ewige Jude") is a mythical immortal man whose legend began to spread in Europe in the 13th century.[a] In the original legend, a Jew who taunted Jesus on the way to the Crucifixion was then cursed to walk the Earth until the Second Coming. The exact nature of the wanderer's indiscretion varies in different versions of the tale, as do aspects of his character; sometimes he is said to be a shoemaker or other tradesman, while sometimes he is the doorman at the estate of Pontius Pilate.

Name

[edit]An early extant manuscript containing the legend is the Flores Historiarum by Roger of Wendover, where it appears in the part for the year 1228, under the title Of the Jew Joseph who is still alive awaiting the last coming of Christ.[3][4][5] The central figure is named Cartaphilus before being baptized later by Ananias as Joseph.[6] The root of the name Cartaphilus can be divided into kartos and philos, which can be translated roughly as "dearly" and "loved", connecting the legend of the Wandering Jew to "the disciple whom Jesus loved".[7]

At least from the 17th century, the name Ahasver has been given to the Wandering Jew, apparently adapted from Ahasuerus (Xerxes), the Persian king in the Book of Esther, who was not a Jew, and whose very name among medieval Jews was an exemplum of a fool.[8] This name may have been chosen because the Book of Esther describes the Jews as a persecuted people, scattered across every province of Ahasuerus' vast empire, similar to the later Jewish diaspora in countries whose state and/or majority religions were forms of Christianity.[9]

A variety of names have since been given to the Wandering Jew, including Matathias, Buttadeus and Isaac Laquedem, which is a name for him in France and the Low Countries in popular legend as well as in a novel by Dumas. The name Paul Marrane (an anglicized version of Giovanni Paolo Marana, the alleged author of Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy) was incorrectly attributed to the Wandering Jew by a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article, yet the mistake influenced popular culture.[10] The name given to the Wandering Jew in the spy's Letters is Michob Ader.[11]

The name Buttadeus (Botadeo in Italian; Boutedieu in French) most likely has its origin in a combination of the Vulgar Latin version of batuere ("to beat or strike") with the word for God, deus. Sometimes this name is misinterpreted as Votadeo, meaning "devoted to God", drawing similarities to the etymology of the name Cartaphilus.[7]

Where German or Russian is spoken, the emphasis has been on the perpetual character of his punishment, and thus he is known there as Ewiger Jude and vechny zhid (вечный жид), the "Eternal Jew". In French and other Romance languages, the usage has been to refer to the wanderings, as in le Juif errant (French), judío errante (Spanish) or l'ebreo errante (Italian), and this has been followed in English from the Middle Ages as the Wandering Jew.[5] In Finnish, he is known as Jerusalemin suutari ("Shoemaker of Jerusalem"), implying he was a cobbler by his trade. In Hungarian, he is known as the bolyongó zsidó ("Wandering Jew" but with a connotation of aimlessness).

Origin and evolution

[edit]Biblical sources

[edit]The origins of the legend are uncertain; perhaps one element is the story in Genesis of Cain, who is issued with a similar punishment—to wander the Earth, scavenging and never reaping, although without the related punishment of endlessness. According to Jehoshua Gilboa, many commentators have pointed to Hosea 9:17 as a statement of the notion of the "eternal/wandering Jew".[12] The legend stems from Jesus' words given in Matthew 16:28:

Ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν, εἰσίν τινες ὧδε ἑστῶτες, οἵτινες οὐ μὴ γεύσωνται θανάτου, ἕως ἂν ἴδωσιν τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐρχόμενον ἐν τῇ βασιλείᾳ αὐτοῦ.

Truly I tell you, some who are standing here will not taste death before they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom. (New International Version)

Verily I say unto you, There be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom. (King James Version)[b][13]

A belief that the disciple whom Jesus loved would not die was apparently popular enough in the early Christian world to be denounced in the Gospel of John:

And Peter, turning about, seeth the disciple following whom Jesus loved, who had also leaned on His breast at the supper, and had said, Lord, which is he who betrayeth Thee? When, therefore, Peter saw him, he said to Jesus, Lord, and what shall he do? Jesus saith to him, If I will that he remain till I come, what is that to thee? follow thou Me. Then this saying went forth among the brethren, that that disciple would not die; yet Jesus had not said to him that he would not die; but, If I will that he tarry till I come, what is that to thee?

— John 21:20-23, KJV

Another passage in the Gospel of John speaks about a guard of the high priest who slaps Jesus (John 18:19–23). Earlier, the Gospel of John talks about Simon Peter striking the ear from Malchus, a servant of the high priest (John 18:10). Although this servant is probably not the same guard who struck Jesus, Malchus is nonetheless one of the many names given to the wandering Jew in later legend.[14]

Early Christianity

[edit]

The later amalgamation of the fate of the specific figure of legend with the condition of the Jewish people as a whole, well established by the 18th century, had its precursor even in early Christian views of Jews and the diaspora.[15] Extant manuscripts have shown that as early as the time of Tertullian (c. 200), some Christian proponents were likening the Jewish people to a "new Cain", asserting that they would be "fugitives and wanderers (upon) the earth".[16]

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens (b. 348) writes in his Apotheosis (c. 400): "From place to place the homeless Jew wanders in ever-shifting exile, since the time when he was torn from the abode of his fathers and has been suffering the penalty for murder, and having stained his hands with the blood of Christ whom he denied, paying the price of sin."[17]

A late 6th and early 7th century monk named Johannes Moschos records an important version of a Malchean figure. In his Leimonarion, Moschos recounts meeting a monk named Isidor who had purportedly met a Malchus-type of figure who struck Christ and is therefore punished to wander in eternal suffering and lament:[7]

I saw an Ethiopian, clad in rags, who said to me, "You and I are condemned to the same punishment." I said to him, "Who are you?" And the Ethiopian who had appeared to me replied, "I am he who struck on the cheek the creator of the universe, our Lord Jesus Christ, at the time of the Passion. That is why," said Isidor, "I cannot stop weeping."

Medieval legend

[edit]Some scholars have identified components of the legend of the Eternal Jew in Teutonic legends of the Eternal Hunter, some features of which are derived from Odin mythology.[18]

"In some areas the farmers arranged the rows in their fields in such a way that on Sundays the Eternal Jew might find a resting place. Elsewhere they assumed that he could rest only upon a plough or that he had to be on the go all year and was allowed a respite only on Christmas."[18]

Most likely drawing on centuries of unwritten folklore, legendry, and oral tradition[citation needed] brought to the West as a product of the Crusades, a Latin chronicle from Bologna, Ignoti Monachi Cisterciensis S. Mariae de Ferraria Chronica et Ryccardi de Sancto Germano Chronica priora, contains the first written articulation of the Wandering Jew. In the entry for the year 1223, the chronicle describes the report of a group of pilgrims who meet "a certain Jew in Armenia" (quendam Iudaeum) who scolded Jesus on his way to be crucified and is therefore doomed to live until the Second Coming. Every hundred years the Jew returns to the age of 30.[7]

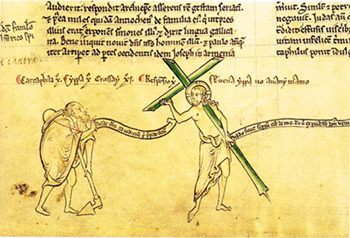

A variant of the Wandering Jew legend is recorded in the Flores Historiarum by Roger of Wendover around the year 1228.[19][20][21] An Armenian archbishop, then visiting England, was asked by the monks of St Albans Abbey about the celebrated Joseph of Arimathea, who had spoken to Jesus, and was reported to be still alive. The archbishop answered that he had himself seen such a man in Armenia, and that his name was Cartaphilus, a Jewish shoemaker, who, when Jesus stopped for a second to rest while carrying his cross, hit him, and told him "Go on quicker, Jesus! Go on quicker! Why dost Thou loiter?", to which Jesus, "with a stern countenance", is said to have replied: "I shall stand and rest, but thou shalt go on till the last day." The Armenian bishop also reported that Cartaphilus had since converted to Christianity and spent his wandering days proselytizing and leading a hermit's life.

Matthew Paris included this passage from Roger of Wendover in his own history; and other Armenians appeared in 1252 at the Abbey of St Albans, repeating the same story, which was regarded there as a great proof of the truth of the Christian religion.[22] The same Armenian told the story at Tournai in 1243, according to the Chronicles of Phillip Mouskes (chapter ii. 491, Brussels, 1839). After that, Guido Bonatti writes people saw the Wandering Jew in Forlì (Italy), in the 13th century; other people saw him in Vienna and elsewhere.[23]

There were claims of sightings of the Wandering Jew throughout Europe and later the Americas, since at least 1542 in Hamburg up to 1868 in Harts Corners, New Jersey.[24] Joseph Jacobs, writing in the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), commented, "It is difficult to tell in any one of these cases how far the story is an entire fiction and how far some ingenious impostor took advantage of the existence of the myth".[5]

Another legend about Jews, the so-called "Red Jews", was similarly common in Central Europe in the Middle Ages.[25]

In literature

[edit]17th and 18th centuries

[edit]The legend became more popular after it appeared in a 17th-century pamphlet of four leaves, Kurtze Beschreibung und Erzählung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasverus (Short Description and Tale of a Jew with the Name Ahasuerus).[c] "Here we are told that some fifty years before, a bishop met him in a church at Hamburg, repentant, ill-clothed and distracted at the thought of having to move on in a few weeks."[8] As with urban legends, particularities lend verisimilitude: the bishop is specifically Paulus von Eitzen, General Superintendent of Schleswig. The legend spread quickly throughout Germany, no less than eight different editions appearing in 1602; altogether forty appeared in Germany before the end of the 18th century. Eight editions in Dutch and Flemish are known; and the story soon passed to France, the first French edition appearing in Bordeaux, 1609, and to England, where it appeared in the form of a parody in 1625.[26] The pamphlet was translated also into Danish and Swedish; and the expression "eternal Jew" is current in Czech, Slovak, and German, der ewige Jude. Apparently the pamphlets of 1602 borrowed parts of the descriptions of the wanderer from reports (most notably by Balthasar Russow) about an itinerant preacher called Jürgen.[27][dead link]

In France, the Wandering Jew appeared in Simon Tyssot de Patot's La Vie, les Aventures et le Voyage de Groenland du Révérend Père Cordelier Pierre de Mésange (1720).

In Britain, a ballad with the title The Wandering Jew was included in Thomas Percy's Reliques published in 1765.[28]

In England, the Wandering Jew makes an appearance in one of the secondary plots in Matthew Lewis's Gothic novel The Monk (1796). The Wandering Jew is depicted as an exorcist whose origin remains unclear. The Wandering Jew also plays a role in St. Leon (1799) by William Godwin.[29] The Wandering Jew also appears in two English broadside ballads of the 17th and 18th centuries, The Wandering Jew, and The Wandering Jew's Chronicle. The former recounts the biblical story of the Wandering Jew's encounter with Christ, while the latter tells, from the point of view of the titular character, the succession of English monarchs from William the Conqueror through either King Charles II (in the 17th-century text) or King George II and Queen Caroline (in the 18th-century version).[30][31]

In 1797, the operetta The Wandering Jew, or Love's Masquerade by Andrew Franklin was performed in London.[32]

19th century

[edit]Britain

[edit]In 1810, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote a poem in four cantos with the title The Wandering Jew but it remained unpublished until 1877.[33] In two other works of Shelley, Ahasuerus appears, as a phantom in his first major poem Queen Mab: A Philosophical Poem (1813) and later as a hermit healer in his last major work, the verse drama Hellas.[34]

John Galt published a book in 1820 called The Wandering Jew.

Thomas Carlyle, in his Sartor Resartus (1833–34), compares its hero Diogenes Teufelsdröckh on several occasions to the Wandering Jew (also using the German wording der Ewige Jude).

In Chapter 15 of Great Expectations (1861) by Charles Dickens, the journeyman Orlick is compared to the Wandering Jew.

George MacDonald includes pieces of the legend in Thomas Wingfold, Curate (London, 1876).

United States

[edit]Nathaniel Hawthorne's stories "A Virtuoso's Collection" and "Ethan Brand" feature the Wandering Jew serving as a guide to the stories' characters.[35]

In 1873, a publisher in the United States (Philadelphia, Gebbie) produced The Legend of the Wandering Jew, a series of twelve designs by Gustave Doré (Reproduced by Photographic Printing) with Explanatory Introduction, originally made by Doré in 1856 to illustrate a short poem by Pierre-Jean de Béranger. For each one, there was a couplet, such as "Too late he feels, by look, and deed, and word, / How often he has crucified his Lord".[d]

Eugene Field's short story "The Holy Cross" (1899) features the Jew as a character.[35]

In 1901, a New York publisher reprinted, under the title "Tarry Thou Till I Come", George Croly's "Salathiel", which treated the subject in an imaginative form. It had appeared anonymously in 1828.

In Lew Wallace's novel The Prince of India (1893), the Wandering Jew is the protagonist. The book follows his adventures through the ages, as he takes part in the shaping of history.[e] An American rabbi, H. M. Bien, turned the character into the "Wandering Gentile" in his novel Ben-Beor: A Tale of the Anti-Messiah; in the same year John L. McKeever wrote a novel, The Wandering Jew: A Tale of the Lost Tribes of Israel.[35]

A humorous account of the Wandering Jew appears in chapter 54 of Mark Twain's 1869 travel book The Innocents Abroad.[38]

Germany

[edit]The legend has been the subject of German poems by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, Aloys Schreiber, Wilhelm Müller, Nikolaus Lenau, Adelbert von Chamisso, August Wilhelm von Schlegel, Julius Mosen (an epic, 1838), and Ludwig Köhler;[which?] of novels by Franz Horn (1818), Oeklers,[who?] and Levin Schücking; and of tragedies by Ernst August Friedrich Klingemann ("Ahasuerus", 1827) and Joseph Christian Freiherr von Zedlitz (1844). It is either the Ahasuerus of Klingemann or that of Achim von Arnim in his play, Halle and Jerusalem, to whom Richard Wagner refers in the final passage of his notorious essay Das Judenthum in der Musik.

There are clear echoes of the Wandering Jew in Wagner's The Flying Dutchman, whose plot line is adapted from a story by Heinrich Heine in which the Dutchman is referred to as "the Wandering Jew of the ocean",[39] and his final opera Parsifal features a woman called Kundry who is in some ways a female version of the Wandering Jew. It is alleged that she was formerly Herodias, and she admits that she laughed at Jesus on his route to the Crucifixion, and is now condemned to wander until she meets with him again (cf. Eugene Sue's version, below).

Robert Hamerling, in his Ahasver in Rom (Vienna, 1866), identifies Nero with the Wandering Jew. Goethe had designed a poem on the subject, the plot of which he sketched in his Dichtung und Wahrheit.[40][41]

Denmark

[edit]Hans Christian Andersen made his "Ahasuerus" the Angel of Doubt, and was imitated by Heller in a poem on "The Wandering of Ahasuerus", which he afterward developed into three cantos. Martin Andersen Nexø wrote a short story named "The Eternal Jew", in which he also refers to Ahasuerus as the spreading of the Jewish gene pool in Europe.

The story of the Wandering Jew is the basis of the essay "The Unhappiest One" in Søren Kierkegaard's Either/Or (published 1843 in Copenhagen). It is also discussed in an early portion of the book that focuses on Mozart's opera Don Giovanni.

In the play Genboerne (The Residents) by Jens Christian Hostrup (1844), the Wandering Jew is a character (in this context called "Jerusalem's shoemaker") and his shoes make the wearer invisible. The protagonist of the play borrows the shoes for a night and visits the house across the street as an invisible man.

France

[edit]The French writer Edgar Quinet published his prose epic on the legend in 1833, making the subject the judgment of the world; and Eugène Sue wrote his Juif errant in 1844, in which the author connects the story of Ahasuerus with that of Herodias. Grenier's 1857 poem on the subject may have been inspired by Gustave Doré's designs, which were published the preceding year. One should also note Paul Féval, père's La Fille du Juif Errant (1864), which combines several fictional Wandering Jews, both heroic and evil, and Alexandre Dumas' incomplete Isaac Laquedem (1853), a sprawling historical saga. In Guy de Maupassant's short story "Uncle Judas", the local people believe that the old man in the story is the Wandering Jew.

In the late 1830's, the epic novel "The Wandering Jew," written by Eugene Sue was published in serialized form.

Russia

[edit]In Russia, the legend of the Wandering Jew appears in an incomplete epic poem by Vasily Zhukovsky, "Ahasuerus" (1857) and in another epic poem by Wilhelm Küchelbecker, "Ahasuerus, a Poem in Fragments", written between 1832 and 1846 but not published until 1878, long after the poet's death. Alexander Pushkin also began a long poem on Ahasuerus (1826) but later abandoned the project, completing fewer than thirty lines.

Other literature

[edit]The Wandering Jew makes a notable appearance in the gothic masterpiece of the Polish writer Jan Potocki, The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, written about 1797.[35]

Brazilian writer and poet Machado de Assis often used Jewish themes in his writings. One of his short stories, Viver! ("To Live!"), is a dialog between the Wandering Jew (named as Ahasverus) and Prometheus at the end of time. It was published in 1896 as part of the book Várias histórias (Several stories).

Castro Alves, another Brazilian poet, wrote a poem named "Ahasverus e o gênio" ("Ahasverus and the genie"), in a reference to the Wandering Jew.

The Hungarian poet János Arany also wrote a ballad called "Az örök zsidó" ("The Eternal Jew").

The Slovenian poet Anton Aškerc wrote a poem called "Ahasverjev tempelj" ("Ahasverus' Temple").

The Spanish military writer José Gómez de Arteche's novel Un soldado español de veinte siglos (A Spanish soldier of twenty centuries) (1874–1886) depicts the Wandering Jew as serving in the Spanish military of different periods.[42]

20th century

[edit]Latin America

[edit]In Mexican writer Mariano Azuela's 1920 novel set during the Mexican Revolution, The Underdogs (Spanish: Los de abajo), the character Venancio, a semi-educated barber, entertains the band of revolutionaries by recounting episodes from The Wandering Jew, one of two books he had read.[43]

In Argentina, the topic of the Wandering Jew has appeared several times in the work of Enrique Anderson Imbert, particularly in his short-story El Grimorio (The Grimoire), included in the eponymous book.

Chapter XXXVII, "El Vagamundo", in the collection of short stories, Misteriosa Buenos Aires, by the Argentine writer Manuel Mujica Láinez also centres round the wandering of the Jew.

The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges named the main character and narrator of his short story "The Immortal" Joseph Cartaphilus (in the story he was a Roman military tribune who gained immortality after drinking from a magical river and dies in the 1920s).

In Green Mansions, W. H. Hudson's protagonist Abel references Ahasuerus, as an archetype of someone, like himself, who prays for redemption and peace, while condemned to walk the earth.

In 1967, the Wandering Jew appears as an unexplained magical realist townfolk legend in Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude. In his short story, “One Day After Saturday,” the character Father Anthony Isabel claims to encounter the Wandering Jew again in the mythical town of Macondo.

Colombian writer Prospero Morales Pradilla, in his novel Los pecados de Inés de Hinojosa (The sins of Ines de Hinojosa), describes the famous Wandering Jew of Tunja that has been there since the 16th century. He talks about the wooden statue of the Wandering Jew that is in Santo Domingo church and every year during the holy week is carried around on the shoulders of the Easter penitents around the city. The main feature of the statue are his eyes; they can express the hatred and anger in front of Jesus carrying the cross.

Brazil

[edit]In 1970, Polish-Brazilian writer Samuel Rawet published "Viagens de Ahasverus à Terra Alheia em Busca de um Passado que não existe porque é Futuro e de um Futuro que já passou porque sonhado" ("Travels of Ahasverus to foreign lands in search of a past that does not exist because it is a future and a future that has already passed because it was dreamed"), a short story in which the main character, Ahasverus, or The Wandering Jew, is capable of transforming into various other figures.

France

[edit]Guillaume Apollinaire parodies the character in "Le Passant de Prague" in his collection L'Hérésiarque et Cie (Heresiarch & Co., 1910).[44]

Jean d'Ormesson wow Histoire du juif errant in (1991).

In Simone de Beauvoir's novel Tous les Hommes sont Mortels (All Men are Mortal, 1946), the leading figure Raymond Fosca undergoes a fate similar to the wandering Jew, who is explicitly mentioned as a reference.

Germany

[edit]In both Gustav Meyrink's The Green Face (1916) and Leo Perutz's The Marquis of Bolibar (1920), the Wandering Jew features as a central character.[45] The German writer Stefan Heym in his novel Ahasver (translated into English as The Wandering Jew)[46] maps a story of Ahasuerus and Lucifer ranging between ancient times, the Germany of Luther and socialist East Germany. In Heym's depiction, the Wandering Jew is a highly sympathetic character.

Belgium

[edit]The Belgian writer August Vermeylen published in 1906 a novel called De wandelende Jood (The Wandering Jew).

Romania

[edit]Mihai Eminescu, an influential Romanian Romantic writer, depicts a variation in his 1872 fantasy novella Poor Dionysus (Romanian: Sărmanul Dionis). A student named Dionis goes on a surreal journey through the book of Zoroaster, which seemingly grants him godlike abilities. The book is given to him by Ruben, his Jewish master who is a philosopher. Dionis awakens as Friar Dan, and is eventually tricked by Ruben, being sentenced by God to a life of insanity. This he can only escape by resurrection or metempsychosis.

Similarly, Mircea Eliade presents in his novel Dayan (1979) a student's mystic and fantastic journey through time and space under the guidance of the Wandering Jew, in the search of a higher truth and of his own self.

Russia

[edit]The Soviet satirists Ilya Ilf and Yevgeni Petrov had their hero Ostap Bender tell the story of the Wandering Jew's death at the hands of Ukrainian nationalists in The Little Golden Calf. In Vsevolod Ivanov's story Ahasver a strange man comes to a Soviet writer in Moscow in 1944, introduces himself as "Ahasver the cosmopolite" and claims he is Paul von Eitzen, a theologian from Hamburg, who concocted the legend of the Wandering Jew in the 16th century to become rich and famous but then turned himself into a real Ahasver against his will. The novel Overburdened with Evil (1988) by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky involves a character in modern setting who turns out to be Ahasuerus, identified at the same time in a subplot with John the Divine. In the novel Going to the Light (Идущий к свету, 1998) by Sergey Golosovsky, Ahasuerus turns out to be Apostle Paul, punished (together with Moses and Mohammed) for inventing false religion.

South Korea

[edit]The 1979 Korean novel Son of Man by Yi Mun-yol (introduced and translated into English by Brother Anthony, 2015), is framed within a detective story. It describes the character of Ahasuerus as a defender of humanity against unreasonable laws of the Jewish god, Yahweh. This leads to his confrontations with Jesus and withholding of aid to Jesus on the way to Calvary. The unpublished manuscript of the novel was written by a disillusioned theology student, Min Yoseop, who has been murdered. The text of the manuscript provides clues to solving the murder. There are strong parallels between Min Yoseop and Ahasuerus, both of whom are consumed by their philosophical ideals.[47]

Sweden

[edit]In Pär Lagerkvist's 1956 novel The Sibyl, Ahasuerus and a woman who was once the Delphic Sibyl each tell their stories, describing how an interaction with the divine damaged their lives. Lagerkvist continued the story of Ahasuerus in Ahasverus död (The Death of Ahasuerus, 1960).

Ukraine

[edit]In Ukrainian legend, there is a character of Marko Pekelnyi (Marko of Hell, Marko the Infernal) or Marko the Accursed. This character is based on the archetype of the Wandering Jew. The origin of Marko's image is also rooted in the legend of the traitor Mark, who struck Christ with an iron glove before his death on the cross, for which God punished him by forcing him to eternally walk underground around a pillar, not stopping even for a minute; he bangs his head against a pillar from time to time, disturbs even hell and its master with these sounds and complains that he cannot die. Another explanation for Mark's curse is that he fell in love with his own sister, then killed her along with his mother, for which he was punished by God.

Ukrainian authors Oleksa Storozhenko, Lina Kostenko, Ivan Malkovych and others have written prose and poetry about Marko the Infernal. Also, Les Kurbas Theatre made a stage performance "Marko the Infernal, or the Easter Legend" based on the poetry of Vasyl Stus.

United Kingdom

[edit]Bernard Capes' story "The Accursed Cordonnier" (1900) depicts the Wandering Jew as a figure of menace.[35]

Robert Nichols' novella "Golgotha & Co." in his collection Fantastica (1923) is a satirical tale where the Wandering Jew is a successful businessman who subverts the Second Coming.[35]

In Evelyn Waugh's Helena, the Wandering Jew appears in a dream to the protagonist and shows her where to look for the Cross, the goal of her quest.

J. G. Ballard's short story "The Lost Leonardo", published in The Terminal Beach (1964), centres on a search for the Wandering Jew. The Wandering Jew is revealed to be Judas Ischariot, who is so obsessed with all known depictions of the crucifixion that he travels all around the world to steal them from collectors and museums, replacing them with forged duplicates. The story's first German translation, published the same year as the English original, translates the story's title as Wanderer durch Zeit und Raum ("Wanderer through Time and Space"), directly referencing the concept of the "eternally Wandering" Jew.

The horror novel Devil Daddy (1972) by John Blackburn features the Wandering Jew.[48]

The Wandering Jew appears as a sympathetic character in Diana Wynne Jones's young adult novel The Homeward Bounders (1981). His fate is tied in with larger plot themes regarding destiny, disobedience, and punishment.

In Ian McDonald's 1991 story Fragments of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria (originally published in Tales of the Wandering Jew, ed. Brian Stableford), the Wandering Jew first violates and traumatizes a little girl during the Edwardian era, where her violation is denied and explained away by Sigmund Freud analyzing her and coming to the erroneous conclusion that her signs of abuse are actually due to a case of hysteria or prudishness. A quarter of a century later, the Wandering Jew takes on the guise of a gentile éminence grise who works out the genocidal ideology and bureaucracy of the Holocaust and secretly incites the Germans into carrying it out according to his plans. In a meeting with one of the victims where he's gloatingly telling her that she and millions of others will die, he reveals that he did it out of self-hatred.

United States

[edit]In O. Henry's 1911 story "The Door of Unrest", a drunk shoemaker Mike O'Bader comes to a local newspaper editor and claims to be the Jerusalem shoemaker Michob Ader who did not let Christ rest upon his doorstep on the way to crucifixion and was condemned to live until the Second Coming. However, Mike O'Bader insists he is a Gentile, not a Jew.

"The Wandering Jew" is the title of a short poem by Edwin Arlington Robinson which appears in his 1920 book The Three Taverns.[49] In the poem, the speaker encounters a mysterious figure with eyes that "remembered everything". He recognizes him from "his image when I was a child" and finds him to be bitter, with "a ringing wealth of old anathemas"; a man for whom the "world around him was a gift of anguish". The speaker does not know what became of him, but believes that "somewhere among men to-day / Those old, unyielding eyes may flash / And flinch—and look the other way."

George Sylvester Viereck and Paul Eldridge wrote a trilogy of novels My First Two Thousand Years: an Autobiography of the Wandering Jew (1928), in which Isaac Laquedem is a Roman soldier who, after being told by Jesus that he will "tarry until I return", goes on to influence many of the great events of history. He frequently encounters Solome (described as "The Wandering Jewess"), and travels with a companion, to whom he has passed on his immortality via a blood transfusion (another attempt to do this for a woman he loved ended in her death).

"Ahasver", a cult leader identified with the Wandering Jew, is a central figure in Anthony Boucher's classic mystery novel Nine Times Nine (originally published 1940 under the name H. Holmes).

Written by Isaac Asimov in October 1956, the short story "Does a Bee Care?" features a highly influential character named Kane who is stated to have spawned the legends of the Walking Jew and the Flying Dutchman in his thousands of years maturing on Earth, guiding humanity toward the creation of technology which would allow it to return to its far-distant home in another solar system. The story originally appeared in the June 1957 edition of If: Worlds of Science Fiction magazine and is collected in the anthology Buy Jupiter and Other Stories (Isaac Asimov, Doubleday Science Fiction, 1975).

A Jewish Wanderer appears in A Canticle for Leibowitz, a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel by Walter M. Miller, Jr. first published in 1960; some children are heard saying of the old man, "What Jesus raises up STAYS raised up", and introduces himself in Hebrew as Lazarus, implying that he is Lazarus of Bethany, whom Christ raised from the dead. Another possibility hinted at in the novel is that this character is also Isaac Edward Leibowitz, founder of the (fictional) Albertian Order of St. Leibowitz (and who was martyred for trying to preserve books from burning by a savage mob). The character speaks and writes in Hebrew and English, and wanders around the desert, though he has a tent on a mesa overlooking the abbey founded by Leibowitz, which is the setting for almost all the novel's action. The character appears again in three subsequent novellas which take place hundreds of years apart, and in Miller's 1997 follow-up novel, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman.

Ahasuerus must remain on Earth after space travel is developed in Lester del Rey's "Earthbound" (1963).[50] The Wandering Jew also appears in Mary Elizabeth Counselman's story "A Handful of Silver" (1967).[51] Barry Sadler has written a series of books featuring a character called Casca Rufio Longinus who is a combination of two characters from Christian folklore, Saint Longinus and the Wandering Jew. Jack L. Chalker wrote a five-book series called The Well World Saga in which it is mentioned many times that the creator of the universe, a man named Nathan Brazil, is known as the Wandering Jew. The 10th issue of DC Comics' Secret Origins (January 1987) gave The Phantom Stranger four possible origins. In one of these explanations, the Stranger confirms to a priest that he is the Wandering Jew.[52] Angela Hunt's novel The Immortal (2000) features the Wandering Jew under the name of Asher Genzano.

Although he does not appear in Robert A. Heinlein's novel Time Enough for Love (1973), the central character, Lazarus Long, claims to have encountered the Wandering Jew at least once, possibly multiple times, over the course of his long life. According to Lazarus, he was then using the name Sandy Macdougal and was operating as a con man. He is described as having red hair and being, in Lazarus' words, a "crashing bore".

The Wandering Jew is revealed to be Judas Iscariot in George R. R. Martin's distant-future science fiction parable of Christianity, the 1979 short story "The Way of Cross and Dragon".

In the first two novels of science fiction author Dan Simmons' Hyperion Cantos (1989-1997), a central character is referred to as the Wandering Jew as he roams the galaxy in search of a cure for his daughter's illness. In his later novel Ilium (2003), a woman who is addressed as the Wandering Jew also plays a pivotal role, acting as witness and last remaining Jew during a period where all other Jewish people have been locked away.

The Wandering Jew encounters a returned Christ in Deborah Grabien's 1990 novel Plainsong.[53]

21st century

[edit]Brazil

[edit]Brazilian writer Glauco Ortolano in his 2000 novel Domingos Vera Cruz: Memorias de um Antropofago Lisboense no Brasil uses the theme of the Wandering Jew for its main character, Domingos Vera Cruz, who flees to Brazil in one of the first Portuguese expeditions to the New World after murdering his wife's lover in Portugal. In order to avoid eternal damnation, he must fully repent of his crime. The book of memoirs Domingos dictates in the 21st century to an anonymous transcriber narrates his own saga throughout 500 years of Brazilian history. At the end, Domingos indicates he is finally giving in as he senses the arrival of the Son of Man.

Ireland

[edit]Local history and legends have made reference to The Wandering Jew having haunted an abandoned watermill on the edge of Dunleer town.[54]

United Kingdom

[edit]English writer Stephen Gallagher uses the Wandering Jew as a theme in his 2007 novel The Kingdom of Bones. The Wandering Jew is a character, a theater manager and actor, who turned away from God and toward depravity in exchange for long life and prosperity. He must find another person to take on the persona of the wanderer before his life ends or risk eternal damnation. He eventually does find a substitute in his protégé, Louise. The novel revolves around another character's quest to find her and save her from her assumed damnation.

Sarah Perry's 2018 novel Melmoth is part-inspired by the Wandering Jew and makes several references to the legend in discussing the origin of its titular character.

J. G. Ballard's short story "The Lost Leonardo" features the Wandering Jew as a mysterious art thief.

United States

[edit]- In Glen Berger's play Underneath the Lintel, the main character suspects a 113-year overdue library book was checked out and returned by the Wandering Jew.

- The Wandering Jew appears in "An Arkham Halloween" in the October 30, 2017, issue of Bewildering Stories, as a volunteer to help Miskatonic University prepare a new translation of the Necronomicon, particularly qualified because he knew the author.

- The Wandering Jew appears in Angela Hunt’s inspirational novel The Immortal (2000) and is named Asher Genzano.

- Kenneth Johnson's novel The Man of Legend is a retelling of the story of the Wandering Jew, who is in fact a Roman soldier and head of Pilate's personal guard.

Uzbekistan

[edit]Uzbek writer Isajon Sulton published his novel The Wandering Jew in 2011.[55] In this novel, the Jew does not characterize a symbol of curse; however, they appear as a human being, who is aware of God's presence, after being cursed by Him. Moreover, the novel captures the fortune of present-day wandering Jews, created by humans using high technology.

In art

[edit]19th century

[edit]

Nineteenth-century works depicting the legendary figure as the Wandering (or Eternal) Jew or as Ahasuerus (Ahasver) include:

- 1846, Wilhelm von Kaulbach, Titus destroying Jerusalem. Neue Pinakothek Munich. Commissioned from Kaulbach in 1842 and completed in 1866, it was destroyed by war damage during World War II.

- 1836 Kaulbach's work initially commissioned by Countess Angelina Radzwill.

- 1840 Kaulbach published a booklet of Explanations identifying the main figures.[f]

- 1846 finished work purchased by King Ludwig I of Bavaria for the royal collections; 1853 installed in Neue Pinakothek, Munich.[57]

- 1842 Kaulbach's replica for the stairway murals of the Neues Museum, Berlin commissioned by King Frederick William IV of Prussia.

- 1866 completed.

- 1943 destroyed by war damage.[g]

- 1848–1851, Théophile Schuler's monumental painting The Chariot of Death features a prominent depiction of the Wandering Jew (who is driven away by Death).

- 1852, a coloured caricature was used as a cover design for the June number of the satirical Journal pour rire, published by Charles Philipon.[59][h]

- 1854, Gustave Courbet, The Meeting.[60]

- 1856, Gustave Doré, twelve folio-size illustrations produced for a short poem by Pierre-Jean de Béranger, The Legend of the Wandering Jew, derived from a novel by Eugène Sue (1845)[2]

- 1876, Maurycy Gottlieb, Ahasver. National Museum, Kraków.[56]: Fig.5

- 1888, Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl, Ahasuerus at the End of the World. Private Collection.

- 1899, Samuel Hirszenberg, The Eternal Jew. Exhibited in Łódź, Warsaw and Paris in 1899, now in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.[56]: Fig.6

20th century

[edit]In another artwork, exhibited at Basel in 1901, the legendary figure with the name Der ewige Jude, The Eternal Jew, was shown redemptively bringing the Torah back to the Promised Land.[61]

Among the paintings of Marc Chagall having a connection with the legend, one has the explicit title Le Juif Errant (1923–1925).[i]

In his painting The Wandering Jew (1983)[63] Michael Sgan-Cohen depicts a man with bird's head wearing a Jewish hat, with the Hand of God pointing down from the heaven to the man. The empty chair in the foreground of the painting is a symbol of how the figure cannot settle down and is forced to keep wandering.[64]

In ideology (19th century and after)

[edit]By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the figure of the "Wandering Jew" as a legendary individual had begun to be identified with the fate of the Jewish people as a whole. After the ascendancy of Napoleon Bonaparte at the end of the century and the emancipating reforms in European countries connected with the policy of Napoleon and the Jews, the "Eternal Jew" became an increasingly "symbolic ... and universal character" as the continuing struggle for Jewish emancipation in Prussia and elsewhere in Europe in the course of the nineteenth century gave rise to what came to be referred to as "the Jewish Question".[15]

Before Kaulbach's mural replica of his painting Titus destroying Jerusalem had been commissioned by the King of Prussia in 1842 for the projected Neues Museum, Berlin, Gabriel Riesser's essay "Stellung der Bekenner des mosaischen Glaubens in Deutschland" ("On the Position of Confessors of the Mosaic Faith in Germany") had been published in 1831 and the journal Der Jude, periodische Blätter für Religions und Gewissensfreiheit (The Jew, Periodical for Freedom of Religion and Thought) had been founded in 1832. In 1840 Kaulbach himself had published a booklet of Explanations identifying the main figures for his projected painting, including that of the Eternal Jew in flight as an outcast for having rejected Christ. In 1843 Bruno Bauer's book The Jewish Question was published,[65] where Bauer argued that religious allegiance must be renounced by both Jews and Christians as a precondition of juridical equality and political and social freedom.[66] to which Karl Marx responded with an article by the title "On the Jewish Question".[67]

A caricature which had first appeared in a French publication in 1852, depicting the legendary figure with "a red cross on his forehead, spindly legs and arms, huge nose and blowing hair, and staff in hand", was co-opted by anti-Semites.[68] It was shown at the Nazi exhibition Der ewige Jude in Germany and Austria in 1937–1938. A reproduction of it was exhibited at Yad Vashem in 2007 (shown here).

The exhibition had been held at the Library of the German Museum in Munich from 8 November 1937 to 31 January 1938 showing works that the Nazis considered to be "degenerate art". A book containing images of these works was published under the title The Eternal Jew.[69] It had been preceded by other such exhibitions in Mannheim, Karlsruhe, Dresden, Berlin and Vienna. The works of art displayed at these exhibitions were generally executed by avant-garde artists who had become recognized and esteemed in the 1920s, but the objective of the exhibitions was not to present the works as worthy of admiration but to deride and condemn them.[70]

Portrayal in popular media

[edit]Stage

[edit]Fromental Halévy's opera Le Juif errant, based on the novel by Sue, was premiered at the Paris Opera (Salle Le Peletier) on 23 April 1852, and had 48 further performances over two seasons. The music was sufficiently popular to generate a Wandering Jew Mazurka, a Wandering Jew Waltz, and a Wandering Jew Polka.[71]

A Hebrew-language play titled The Eternal Jew premiered at the Moscow Habimah Theatre in 1919 and was performed at the Habima Theatre in New York in 1926.[72]

Donald Wolfit made his debut as the Wandering Jew in a stage adaptation in London in 1924.[73] The play Spikenard (1930) by C. E. Lawrence, has the Jew wander an uninhabited Earth along with Judas and the Impenitent thief.[35] Glen Berger's 2001 play Underneath the Lintel is a monologue by a Dutch librarian who delves into the history of a book that is returned 113 years overdue and becomes convinced that the borrower was the Wandering Jew.[74]

Film

[edit]There have been several films on the topic of The Wandering Jew:

- 1904 silent film called Le Juif Errant by Georges Méliès[75]

- 1923 saw The Wandering Jew, a British silent film by Maurice Elvey from the basis of E. Temple Thurston's play, starring Matheson Lang. The play had been produced both in Twickenham, London and on Broadway in 1921, the latter co-produced by David Belasco. The play, as well as the two films based upon it, attempts to tell the legend literally, taking the Jew from Biblical times to the Spanish Inquisition.

- Elvey also directed the sound remake The Wandering Jew (1933), with Conrad Veidt in the title role; the film was so popular it broke box office records at the time.[76]

- In 1933, the Jewish Talking Picture Company released a Yiddish-language film entitled The Eternal Jew.[77]

- In 1940, a propaganda pseudo-documentary film was made in Nazi Germany entitled Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew), reflecting Nazism's antisemitism, linking the legend with alleged Jewish malpractices over the ages.

- Another film version of the story, made in Italy in 1948, starred Vittorio Gassman.

- In 1986 film Prison Ship: Star Slammer - The Escape - Adventures of Taura, Part 1, it begins with the wandering priest Zaal, obviously appearing like the Wandering Jew who gets killed by fascist bounty hunters.

- In 1988 film The Seventh Sign the Wandering Jew appears as Father Lucci, who identifies himself as the centuries-old Cartaphilus, Pilate's porter, who took part in the scourging of Jesus before his crucifixion.

- The 1993 film Needful Things, based on the 1991 novel of the same name by Stephen King, has elements of the Wandering Jew legend.[78]

- The 2000 horror film Dracula 2000 and its sequels equate the Wandering Jew with Judas Iscariot.

- A 2007 science fiction film The Man from Earth is similar to the Wandering Jew story in many aspects.

- The 2009 film An Education described both Graham and David Goldman this way, though Lynn Barber's original memoirs it was based on did not.

Television

[edit]- In the third episode of the first season of The Librarians, the character Jenkins mentions the Wandering Jew as an "immortal creature that can be injured, but never killed".

- In the third season of the FX series Fargo, a character named Paul Murrane (played by Ray Wise) appears to three major characters. He acts as a source of counsel to two of them (one of whom he provides a chance at redemption), while forcing the third to confront his past involvement in numerous killings. Though the character is widely believed to represent the Wandering Jew, the name is associated with a historical mistake: it is an anglicized version of Paolo Marana (Giovanni Paolo Marana allegedly authored Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy whose second volume features the Wandering Jew), rather than a known alias of the legendary figure.

- In the Japanese manga and accompanying anime series The Ancient Magus' Bride, the Wandering Jew is represented in the antagonist of Cartaphilus. In his search to end his eternal suffering, Cartaphilus serves as a nuisance to the progression of Chise's training.

- In the television series Peaky Blinders, Jewish gangster Alfie Solomons (played by Tom Hardy), described himself as "The Wandering Jew".

- In "Lagrimas", an episode of the second season of Witchblade, he is portrayed by Jeffrey Donovan as a mysterious drifter who develops a romantic relationship with protagonist Sara Pezzini. His true identity is later revealed to be the cursed Roman soldier Cartaphilus, who hopes the Witchblade can finally bring an end to his suffering.

- In the television series Rawhide the Wandering Jew features in the episode "Incident of the Wanderer" (Season 6, episode 21).[79]

- In the television adaptation of The Sandman, in reference to a meeting of the characters Morpheus and Hob Gadling, Johanna Constantine remarks on a rumor that the Devil (Morpheus) and the Wandering Jew (Hob) meet once every hundred years in a tavern.

Comics

[edit]In Arak: Son of Thunder issue 8, the titular character encounters the Wandering Jew. Arak intervenes on behalf of a mysterious Jewish man who is about to be stoned by the people of a village. Later on, that same individual serves as a guide through the Catacombs of Rome as they seek out the lair of the Black Pope, who holds Arak's allies hostage. His name is given as Josephus and he tells Arak that he is condemned to wander the Earth after mocking Christ en route to the crucifixion.[80]

The DC Comics character Phantom Stranger, a mysterious hero with paranormal abilities, was given four possible origins in an issue of Secret Origins with one of them identifying him as the Wandering Jew. He now dedicates his time to helping mankind, even declining a later offer from God to release him from his penance.[81]

In Deitch's A Shroud for Waldo, serialized in weekly papers such as New York Press and released in book form by Fantagraphics, the hospital attendant who revives Waldo as a hulking demon so he can destroy the AntiChrist, is none other than the Wandering Jew. For carrying out this mission, he is awarded a normal life and, it is implied, marries the woman he just rescued. Waldo, having reverted to cartoon cat form, is also rewarded, finding it in a freight car.

In Neil Gaiman's The Sandman comic series, the character Hob Gadling represents the archetypal Wandering Jew.

In Kore Yamazaki's manga The Ancient Magus' Bride, the character Cartaphilus, also known as Joseph, is a mysterious being that looks like a young boy, but is much older. He is dubbed "The Wandering Jew" and is said to have been cursed with immortality for throwing a rock at the Son of God. It is later revealed that Joseph and Cartaphilus used to be two different people until Joseph fused with Cartaphilus in an attempt to remove his curse, only to become cursed himself.

In chapter 24 (titled "Immortality") of Katsuhisa Kigitsu's manga "Franken Fran", the main character Fran discovers a man who can't die. Once the man is allowed to write he reveals he is in fact The Wandering Jew.

In "Raqiya: The New Book of Revelation Series" by Masao Yajima and Boichi, the main character has multiple encounters with a man who is seeking to die but unable to. Initially called Mr Snow, he later reveals his identity as The Wandering Jew.

In the Wildstorm comic book universe, a man named Manny Weiss is revealed to be The Wandering Jew. He is one of a handful of sentient beings still alive billions of years in the future to witness the heat death of the universe.[82]

Plants

[edit]Various types of plants are called by the common name "wandering Jew", apparently because of these plants' ability to resist gardener's attempt to prevent them from "wandering over the earth until the second coming of Christ" (see Wandering Jew (disambiguation) § Plants). In 2016, to avoid anti-Semitism, the name "wandering dude" to describe Tradescantia has been proposed in an online plant community by Pedram Navid, instead of "Wandering Jew" and "silver inch plant".[83] [84][85][86]

See also

[edit]

- Ashwatthama, a similar legend in Hinduism

- Three Nephites, a similar legend in Mormonism

Notes

[edit]- ^ As described in the first chapter of Curious Myths of the Middle Ages where Sabine Baring-Gould attributed the earliest extant mention of the myth of the Wandering Jew to Matthew Paris. The chapter began with a reference to Gustave Doré's series of twelve illustrations to the legend, and ended with a sentence remarking that, while the original legend was so "noble in its severe simplicity" that few could develop it with success in poetry or otherwise, Doré had produced in this series "at once a poem, a romance, and a chef-d'œuvre of art".[1] First published in two parts in 1866 and 1868, the work was republished in 1877 and in many other editions.[2]

- ^ This verse is quoted in the German pamphlet Kurtze Beschreibung und Erzählung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasverus, 1602.

- ^ This professes to have been printed at Leiden in 1602 by an otherwise unrecorded printer "Christoff Crutzer"; the real place and printer cannot be ascertained.

- ^ a b Gebbie's edition, 1873. A similar title was used for an edition under the imprint of Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, Paris & New York.[2]

- ^ William Russo's 1999 novella Mal Tempo details Wallace's research and real-life attempt to find the mythical character for his novel. Russo also wrote a sequel, entitled Mal Tempo & Friends in 2001.[36][37]

- ^ Kaulbach's booklet had quotations from Old and New Testament prophecies and references to Josephus Flavius' Jewish War as his principal literary source.[56]

- ^ Replica for the stairway murals of the New Museum in Berlin (see fig.5 "The New Museum, Berlin")[58]

- ^ Attribution to Doré uncertain.[56]

- ^ For works of some other artists with 'Wandering Jew' titles, and connected with the theme of the continuing social and political predicament of Jews or the Jewish people see: Brichetto (2006): figs. 24 (1968), 26 (1983), 27 (1996), 28 (2002)[62]

References

[edit]- ^ Baring-Gould, Sabine (1876). "The Wandering Jew". Curious myths of the Middle Ages. London: Rivingtons. pp. 1−31.

- ^ a b c Zafran, Eric (2007). Rosenblum, Robert; Small, Lisa (eds.). Fantasy and faith: The art of Gustave Doré. New York: Dahesh Museum of Art; Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300107371.

- ^ Roger of Wendover (1849). De Joseph, qui ultimum Christi adventum adhuc vivus exspectat (in Latin). p. 175.

- ^ Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History. Vol. 4. H. G. Bohn. 1842.

- ^ a b c Jacobs 1911.

- ^ Roger of Wendover (1849). Roger of Wendover's Flowers of history, Comprising the history of England from the descent of the Saxons to A.D. 1235; formerly ascribed to Matthew Paris. Bohn's antiquarian library. London. hdl:2027/yale.39002013002903.

- ^ a b c d Anderson 1965.

- ^ a b Daube, David (January 1955). "Ahasver". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 45 (3): 243−244. doi:10.2307/1452757. JSTOR 1452757. New Series.

- ^ "Ahasver, Ahasverus, Wandering Jew—People—Virtual Shtetl". Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Crane, Jacob (29 April 2013). "The long transatlantic career of the Turkish spy". Atlantic Studies: Global Currents. 10 (2). Berlin: Routledge: 228–246. doi:10.1080/14788810.2013.785199. S2CID 162189668.

- ^ The Turkish Spy. Vol. 2, Book 3, Letter I. 1691.

- ^ Sweeney, Marvin Alan; Cotter, David W.; Walsh, Jerome T.; Franke, Chris (October 2000). The Twelve Prophets: Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi. Liturgical Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8146-5095-0. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Matthew 16:28 in the King James Version at Wikisource.

- ^ Thomas Frederick Crane (1885). Italian Popular Tales. Macmillan. p. 197. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ a b Bein, Alex (1990). The Jewish question: Biography of a world problem. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8386-3252-9.

- ^ Salo Wittmayer Baron (1993). Social and Religious History of the Jews (18 vols., 2nd ed.). Columbia University Press, 1952–1983. ISBN 0231088566.

- ^ Aurelius Prudentius Clemens (c. 400). Apotheosis. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ a b Baron, Salo Wittmayer (1965). A social and religious history of the Jews: Citizen or alien conjurer. Vol. 11. Columbia University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-231-08847-3. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Roger of Wendover; Matthew Paris (1849). Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Flores historiarum. H.M. Stationery Office. 1890. p. 149. Retrieved 11 October 2010 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ For the 13th century expulsion of Jews, see History of the Jews in England and Edict of Expulsion.

- ^ Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. H. R. Luard, London, 1880, v. 340–341

- ^ Anderson 1991, pp. 22–23.

- ^ "Editorial Summary", Deseret News, 23 September 1868.

- ^ Voß, Rebekka (April 2012). "Entangled Stories: The Red Jews in Premodern Yiddish and German Apocalyptic Lore". AJS Review. 36 (1): 1–41. doi:10.1017/S0364009412000013. ISSN 1475-4541. S2CID 162963937.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph; Wolf, Lucien (2013) [1888]. "[221]: The Wandering Jew telling fortunes to Englishmen. 1625". Bibliotheca Anglo-Judaica: A Bibliographical Guide to Anglo-Jewish History (digital facsimile ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9781108053747. Jacobs and Wolf: Compilers. Reprinted in Halliwell, Books of Character. London, 1857.[full citation needed]

- ^ Beyer, Jürgen (2008). "Jürgen und der ewige Jude. Ein lebender Heiliger wird unsterblich". ARV. Nordic Yearbook of Folklore (in German) (64): 125–140.

- ^ Reliques of ancient English poetry: consisting of old heroic ballads, songs and other pieces of our earlier poets, (chiefly of the lyric kind.) Together with some few of later date, 3rd ed. (Volume 3). pp. 295−301, 128 lines of verse, with prose introduction

- ^ Wallace Austin Flanders (Winter 1967). "Godwin and Gothicism: St. Leon". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 8 (4): 533–545.

- ^ "The Wandering Jew". English Broadside Ballad Archive. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "The Wandering Jew's Chronicle". English Broadside Ballad Archive. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "Andrew Franklin". Ricorso.

- ^ Percy Bysshe Shelley (1877) [posthumous, written 1810]. The Wandering Jew. London: Shelley Society, Reeves and Turner.

- ^ Tamara Tinker (2010), The Impiety of Ahasuerus: Percy Shelley's Wandering Jew, revised ed.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brian Stableford, "Introduction" to Tales of the Wandering Jew edited by Stableford. Dedalus, Sawtry, 1991. ISBN 0-946626-71-5. pp. 1–25.

- ^ Russo, William (1999). Mal Tempo: From the Lost Papers of Lew Wallace. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1470029449. (Novel).

- ^ Russo, William (2001). Mal Tempo & Friends. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1470091880.

- ^ Mark Twain. "Chapter 54". The Innocents Abroad. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ Heinrich Heine, Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski, 1834. See Barry Millington, The Wagner Compendium, London (1992), p. 277

- ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von (1881). "Fifteenth Book". The autobiography of Goethe: Truth and poetry, from my own life. Vol. II: Books XIV-XX. Translated by Morrison, A. J. W. London: George Bell. pp. 35−37. [Translated from the German].

- ^ P. Hume Brown, The Youth of Goethe (London, 1913). Chapter XI, "Goethe and Spinoza—Der ewige Jude 1773–1774"

- ^ Córdoba, José María Gárate (2006). "José Gómez de Arteche y Moro (1821–1906)". Militares y marinos en la Real Sociedad Geográfica (PDF). pp. 79–102. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2011.

- ^ Azuela, Mariano (2008) [1915]. The Underdogs. New York: Penguin. pp. 15, 34.

- ^ Guillaume Apollinaire, L'Hérésiarque & Cie

- ^ Franz Rottensteiner, "Afterword" in Meyrinck, Gustav, The Green Face, translated by Mike Mitchell. Sawtry: Dedalus/Ariadne, 1992, pp.218–224. ISBN 0-946626-92-8

- ^ Heym, Stefan (1999) [first published 1983 as Ahasver]. The Wandering Jew. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-1706-8.

- ^ Yi, Mun-yŏl (2015). Son of man: A novel (1st ed.). Victoria, Texas: Dalkey Archive Press. ISBN 978-1628971194.

- ^ Alan Warren, "The Curse", in S. T. Joshi, ed., Icons of Horror and the Supernatural: an Encyclopedia of our Worst Nightmares (Greenwood, 2007), (op. 129-160) ISBN 0-31333-781-0

- ^ Robinson, Edwin Arlington (1 January 1920). "The three taverns; a book of poems". New York Macmillan Co – via Internet Archive.

- ^ del Rey, Lester (August 1963). "Earthbound". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 44–45.

- ^ Mary Elizabeth Counselman, William Kimber (1980). "A Handful of Silver". In Half In Shadow, pp. 205–212.

- ^ Barr, Mike W. (w), Aparo, Jim (p), Ziuko, Tom (i). "The Phantom Stranger" Secret Origins, vol. 2, no. 10, p. 2–10 (January 1987). DC Comics.

- ^ Chris Gilmore, "Grabien, Deborah" in St. James Guide To Fantasy Writers, edited by David Pringle. St. James Press, 1996. ISBN 1-55862-205-5. pp. 238–39.

- ^ Murphy, Hubert (3 December 2013). "Town's religious history proves a fascinating read". Drogheda Independent. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Uzbekistan Today". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Ronen, Avraham (1998). "Kaulbach's Wandering Jew: An Anti-Jewish Allegory and Two Jewish Responses" (PDF). Assaph: Section B. Studies in Art History. 1998 (3). Tel-Aviv University, Faculty of Fine Arts: 243–262. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ art gallery of 19c. work Pinacotheca

- ^ fig.5 "The New Museum, Berlin" http://www.colbud.hu/mult_ant/Getty-Materials/Bazant7.htm Archived 30 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Levy, Richard S. (2005). Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution. ABC-CLIO. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-85109-439-4.

- ^ Linda Nochlin (September 1967), "Gustave Courbet's Meeting: A Portrait of the Artist as a Wandering Jew". Art Bulletin, vol. 49 No. 3; pp. 209−222

- ^ Sculpture by Alfred Nossig. Fig.3.3, p.79 in Todd Presner Muscular Judaism: The Jewish Body and the Politics of Regeneration. Routledge, 2007. The sculpture was exhibited in 1901 at the Fifth Zionist Congress, which established the Jewish National Fund. At Google Books.

- ^ Brichetto, Joanna L. (20 April 2006). The Wandering Image: Converting the Wandering Jew (Thesis). Vanderbilt University. p. https://etd.library.vanderbilt.edu/etd-03272006-123911.

- ^ Michael Sgan-Cohen.Israeli, 1944-1999. The Wandering Jew, 1983, Israel Museum, Jerusalem

- ^ "Educator's Resources for Passover". Jewish Learning Works. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Die Judenfrage", Brunswick, 1843 [1],

- ^ Moggach, Douglas, "Bruno Bauer", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2010 Edition)[2]

- ^ On the Jewish Question, Karl Marx, written 1843, first published in Paris in 1844 under the German title "Zur Judenfrage" in the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher.[3]

- ^ Mosse, George L. (1998). The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-19-512660-0.

- ^ "Der ewige Jude: "The Eternal Jew or The Wandering Jew"". Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ West, Shearer (2000). The visual arts in Germany 1890-1937: Utopia and despair. Manchester University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-7190-5279-8.

- ^ Anderson 1991, p. 259.

- ^ Nahshon, Edna (15 September 2008). Jews and shoes. Berg. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-84788-050-5. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Harwood, Ronald, "Wolfit, Sir Donald (1902–1968)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008, accessed 14 July 2009

- ^ Alley Theatre (8 August 2008). "Underneath the Lintel". Alley Theatre. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Georges Méliès (Director) (1904). Le Juif Errant. Star Film Company. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ The Film Daily. Wid's Films and Film Folk, inc. 24 January 1935. p. 242. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "FILMS A to Z". jewishfilm.org. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "SF Encyclopedia Editorial Home".

- ^ "Rawhide 'Incident of the Wanderer' (TV Episode 1964)". IMDb. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Roy, Gerry Conway, Mike W. Barr (w), Aparo, Jim (p), Colon, Ernie (i). "A Dark, Unlighted Place..." Arak: Son of Thunder, vol. 1, no. 8 (March 1982).

- ^ Barr, Mike W. (w), Aparo, Jim (p), Aparo, Jim (i). "Tarry Till I Come Again" Secret Origins, vol. 2, no. 10 (January 1987).

- ^ Callahan, Tim (9 July 2012). "The Great Alan Moore Reread: Mr. Majestic, Voodoo, and Deathblow". Tor.com. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ "Wandering Dude History". X. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ "Racism in Taxonomy: What's in a Name?". Hoyt Arboretum. 9 August 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Why We're No Longer Using the Name Wandering Jew". Bloombox Club. 26 June 2019. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Goldwyn, Brittany (23 July 2019). "How to Care for a Wandering Tradescantia Zebrina Plant". by Brittany Goldwyn. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Anderson, George K. (1965). "The Beginnings of the Legend". The legend of the Wandering Jew. Hanover, N.H. (U.S.): Brown University Press. pp. 11–37. Collects both literary versions and folk versions.

- Anderson, George K. (1991). The legend of the Wandering Jew. Hanover, N.H. (U.S.): Brown University Press. ISBN 0-87451-547-5.

- Camilla Rockwood, ed. (2009). Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (18th ed.). Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap. p. 1400. ISBN 9780550104113.

- Cohen, Richard I. The "Wandering Jew" from Medieval Legend to Modern Metaphor, in Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jonathan Karp (eds), The Art of Being Jewish in Modern Times (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007) (Jewish Culture and Contexts)

- Gaer, Joseph (Fishman) The Legend of the Wandering Jew New American Library, 1961 (Dore illustrations) popular account

- Hasan-Rokem, Galit and Alan Dundes The Wandering Jew: Essays in the Interpretation of a Christian Legend (Bloomington:Indiana University Press) 1986. 20th-century folkloristic renderings.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 362−363.

- Manning, Robert Douglas Wandering Jew and Wandering Jewess ISBN 978-1-895507-90-4

- Sabine Baring-Gould, Curious Myths of the Middle Ages (1894)

External links

[edit]- Wandering Jew and Jewess dramatic screenplays

- The Wandering Jew, by Eugène Sue at Project Gutenberg

- David Hoffman, Hon. J.U.D. of Gottegen (1852). Chronicles of the Wandering Jew selected from the originals of Carthaphilus, embracing a period of nearly XIX centuries—detailed description of facts related to Jesus's preaching from a Pharisees coverage

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry

- The (presumed) End of the Wandering Jew from The Golden Calf by Ilf and Petrov

- Israel's First President, Chaim Weizmann, "A Wandering Jew" Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- "The Wandering Image: Converting the Wandering Jew" Iconography and visual art. Archived 9 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Wandering Jew" and "The Wandering Jew's Chronicle" English Broadside Ballad Archive

- Full text: The autobiography of Goethe: Truth and poetry, from my own life. Vol. II: Books XIV-XX. London: George Bell. 1881 – via Internet Archive. [Alternative format]

Wandering Jew

View on GrokipediaOrigins of the Legend

Biblical and Early Christian Foundations

The legend of the Wandering Jew, depicting a Jewish figure cursed with immortality for taunting Jesus en route to the Crucifixion, finds no explicit basis in canonical biblical texts.[6] New Testament accounts of the Passion, such as those in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, describe interactions with unnamed individuals who struck or mocked Jesus (e.g., John 18:22, where an officer slaps Jesus during his trial), but none specify a curse of eternal wandering.[7] This absence underscores that the figure emerged from extra-canonical traditions rather than scriptural narrative. Early Christian exegesis loosely connected the motif to eschatological promises of longevity in passages like Matthew 16:28, where Jesus declares, "Truly I say to you, there are some of those who are standing here who will not taste death until they see the Son of Man coming in His kingdom."[8] Interpreters occasionally extrapolated this to imply divinely imposed endurance as punishment or compelled witness, aligning with broader apocalyptic expectations of survival until the parousia. Similarly, Matthew 24:34—"this generation will not pass away until all these things take place"—fueled typological readings of collective Jewish persistence amid tribulation, though such links represent interpretive expansion rather than direct etiology for the legend.[9] Patristic theology further grounded these ideas in covenantal frameworks, portraying Jewish unbelief in Christ as warranting ongoing exile and dispersion as divine chastisement, a theme evident in early discussions of supersessionism. Church fathers like those addressing Israel's role post-Christ emphasized perpetual suffering as evidentiary of theological rejection, prefiguring motifs of unending testimony or retribution without naming an individual wanderer.[10] These typologies, rooted in first-century Jewish-Christian polemics over fulfillment of prophecy, provided conceptual soil for later hagiographic elaborations, though the specific immortal figure appears absent from verified apocryphal gospels or ante-Nicene writings.Medieval Formulation and Spread

The legend of the Wandering Jew first gained written form in 13th-century European chronicles as a narrative of divine curse and eschatological witness, rooted in an account relayed by Eastern pilgrims. In Roger of Wendover's Flores Historiarum, composed around 1236 but recording events for 1228, an Armenian archbishop on pilgrimage to England described encountering in Armenia a man named Cartaphilus, formerly doorkeeper for Pontius Pilate, who struck and mocked Jesus en route to Calvary, prompting Jesus to declare, "I will stand and rest, but thou shalt go on till the last day."[1] [11] This portrayal framed Cartaphilus as an immortal relic, aged to decrepitude yet rejuvenated periodically, confessing his sin and affirming Christ's predicted return.[1] Matthew Paris, who continued Wendover's chronicle at St. Albans Abbey in his Chronica Majora (c. 1240–1259), replicated and expanded the tale, integrating it into broader historical narrative to emphasize the figure's role as living testimony to the Passion.[12] [13] Paris's version, circulated in illuminated manuscripts among monastic communities, preserved Cartaphilus's Eastern origins while adapting details to underscore his perpetual wandering as punishment for rejecting the Messiah.[14] These chronicles marked the legend's transition from oral pilgrim lore—likely influenced by Byzantine and Armenian traditions—to fixed Latin text, prioritizing the figure's utility in exemplifying eternal judgment over speculative biography. The narrative disseminated swiftly through clerical networks, sermons, and manuscript copies in England and continental Europe, with reports of "sightings" echoing the 1228 Armenian account in German chronicles by the mid-13th century.[15] This spread reinforced medieval Christian doctrine, drawing on Augustine's view of Jews as preserved witnesses to divine truth, by casting the wanderer as an undead corroborator of Christ's miracles and resurrection, without direct incitement to violence against contemporary Jews.[13] The legend's appeal lay in its alignment with apocalyptic expectations, portraying immortality not as redemption but as unending exile, a motif crystallized in these early texts amid Crusader-era exchanges between Western Europe and the Levant.[16]Core Narrative and Variations

The Curse and Eternal Wandering

The foundational element of the Wandering Jew legend involves a direct supernatural curse imposed by Jesus Christ on a Jewish figure during the events leading to the Crucifixion. In the narrative, this individual, often portrayed as refusing Jesus respite or verbally mocking him while bearing the cross, receives the rebuke: "I am going, but you shall wait until I return," enforcing immortality and perpetual exile from death or rest until the Second Coming.[17] This penalty operates as a causal mechanism within the myth's logic, linking the personal act of rejection—construed as complicity in deicide—to unending physical and existential dislocation, without natural cessation.[3] Accompanying this immortality are ascribed traits that sustain the wanderer's existence across eras and locales, including exceptional physical endurance to withstand centuries of hardship, innate multilingualism from accumulated exposure to diverse cultures, and occasional prophetic knowledge derived from longevity and remorseful reflection on scripture. A 1602 German pamphlet, Kurze Beschreibung und Erzählung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasverus, exemplifies these by attributing to the figure an ageless vigor, command of ancient and modern tongues, and insights into eschatological timelines, all as inevitable outcomes of the curse's prolongation of life.[18] These attributes underscore the legend's internal coherence, portraying the curse not as arbitrary but as a tailored retribution that amplifies isolation through heightened awareness and capability without relief.[19] While names for the cursed figure vary across retellings—such as Cartaphilus in medieval Latin accounts, Ahasuerus in Protestant German traditions, or Buttadeus in other variants—the punitive theme remains invariant: enforced rootlessness as the inexorable consequence of scorning the divine figure at the pivotal moment of redemption.[12] This consistency preserves the myth's core as a supernatural covenant of endurance, binding the individual to witness history's unfolding until apocalyptic resolution, independent of collective implications.[20]Historical Encounters and Identifications

The earliest documented account of an encounter with the figure later identified as the Wandering Jew dates to 1228, as recorded in Roger of Wendover's Flores Historiarum. An Armenian archbishop, while visiting the monastery at St. Albans in England, reported meeting a man named Cartaphilus in Armenia; Cartaphilus claimed to have been a Jewish shoemaker or porter in Pontius Pilate's service who struck Jesus en route to the crucifixion, after which Jesus declared, "I go; but thou shalt wait till I come," dooming him to prolonged life and wandering until the Second Coming.[1] This narrative was subsequently incorporated and expanded by chronicler Matthew Paris in his Chronica Majora around 1240, portraying Cartaphilus as having assumed the name Joseph after conversion and possessing detailed knowledge of biblical events.[1] Subsequent medieval reports echoed this theme. In 1243, the same Armenian archbishop recounted the story during a visit to Tournai, as noted in the Chronicles of Phillip Mouskes.[1] By the early 15th century, identifications shifted: a figure called Johannes Buttadæus was said to have appeared in Mugello, Italy, in 1413, and in Florence in 1415, claiming the eternal wandering curse.[1] These accounts, drawn from ecclesiastical chronicles, served to authenticate the legend through purported eyewitness testimony from clergy, though they lack independent corroboration beyond hagiographic traditions. The legend gained wider circulation in the early modern period through a surge of reported sightings across Europe, often documented in pamphlets and local records to evoke eschatological awe or moral warning. A notable early claim occurred in Hamburg in 1542 (or 1547 in some variants), where the figure allegedly conversed with a young Paul von Eitzen in a church, recounting ancient events and displaying unnatural vitality.[1] Similar identifications proliferated: Spain in 1575; Vienna in 1599; Lübeck in 1601 and 1603; Prague in 1602, where he was named Ahasuerus in a widely circulated German pamphlet Kurtze Beschreibung und Erzählung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasverus, describing his appearance as aged yet vigorous and his testimony of the Passion; Bavaria in 1604; and others in Ypres (1623), Brussels (1640 and 1774), Paris (1644), and Leipsic (1642).[1] These reports, typically from Protestant regions amid Reformation-era anxieties, emphasized the figure's role as a living witness to Christ's divinity, though skeptics attributed them to folklore or fraud designed to bolster Christian narratives against Jewish communities.[1] Sightings continued sporadically into later centuries, reflecting the legend's enduring appeal. In 1658, he was reportedly seen in Stamford, England; in 1672 near Astrakhan, Russia; and in Munich in 1721.[1] A 19th-century American claim placed him in Harts Corners, New York, in 1868, interacting with a Mormon settler, as reported in the Deseret News.[1] Such identifications, while unsubstantiated by empirical evidence, illustrate how the Wandering Jew motif adapted to local contexts, often amplifying antisemitic tropes of perpetual Jewish exile as divine punishment, yet occasionally inspiring reflections on immortality and repentance in Christian thought.[1]Theological Interpretations

Christian Moral and Eschatological Significance

In Christian theology, the legend of the Wandering Jew exemplifies the moral consequences of impiety and rejection of divine revelation, portraying eternal wandering as a direct retribution for scorning Christ during his Passion. This narrative underscores accountability, where the individual's refusal to grant Jesus rest—echoing the taunt "Go on quicker!"—results in perpetual unrest, serving as a cautionary parable against unbelief. Analogous to Cain's curse in Genesis 4:12, which doomed him to be "a fugitive and a vagabond" for fratricide, the Wanderer's immortality without repose illustrates the causal link between sin and unending exile from peace, observable in the historical dispersion of Jews as empirical corroboration of prophetic judgments like Deuteronomy 28:64-65 on covenant breach.[21][17] Patristic writings laid groundwork for this moral framework by interpreting Jewish exile collectively as divine punishment for deicide, a theme Tertullian elaborated in his Apology (c. 197 AD), describing Jews as "a race of wanderers, exiles from their own land" whose scattering validates Christian claims over paganism. The medieval legend personalizes this into an immortal witness, amplifying the lesson: impenitence yields not mere temporal hardship but unending torment, contrasting with the rest promised to believers in Hebrews 4:9-10. This individualized curse functions evangelically, as the Wanderer, compelled to recount his encounter, testifies to Christ's historicity and the folly of rejection.[22][23] Eschatologically, the figure marks the axis of divine history, cursed to endure until Christ's Second Coming, when his death signals the consummation of judgment and redemption. This aligns with Revelation's motifs of final accountability, where unrepentant humanity faces eternal separation (Revelation 20:11-15), the Wanderer's longevity providing a living relic of the first advent while heralding the parousia. In chronicles like Matthew Paris's Chronica Majora (13th century), sightings of the Wanderer reinforce apocalyptic expectation, positioning him as a providential signpost amid temporal woes, his release coinciding with universal vindication for the faithful.[17][21]Views as Divine Retribution for Rejecting Christ