Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

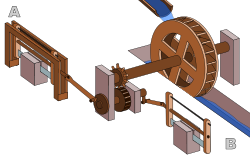

Water wheel

View on Wikipedia

A water wheel is a machine for converting the kinetic energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a large wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with numerous blades or buckets attached to the outer rim forming the drive mechanism. Water wheels were still in commercial use well into the 20th century, although they are no longer in common use today. Water wheels are used for milling flour in gristmills, grinding wood into pulp for papermaking, hammering wrought iron, machining, ore crushing and pounding fibre for use in the manufacture of cloth.

Some water wheels are fed by water from a mill pond, which is formed when a flowing stream is dammed. A channel for the water flowing to or from a water wheel is called a mill race. The race bringing water from the mill pond to the water wheel is a headrace; the one carrying water after it has left the wheel is commonly referred to as a tailrace.[1]

Waterwheels were used for various purposes from things such as agriculture to metallurgy in ancient civilizations spanning the Near East, Hellenistic world, China, Roman Empire and India. Waterwheels saw continued use in the post-classical age, like in medieval Europe and the Islamic Golden Age, but also elsewhere. In the mid- to late 18th century John Smeaton's scientific investigation of the water wheel led to significant increases in efficiency, supplying much-needed power for the Industrial Revolution.[2][3] Water wheels began being displaced by the smaller, less expensive and more efficient turbine, developed by Benoît Fourneyron, beginning with his first model in 1827.[3] Turbines are capable of handling high heads, or elevations, that exceed the capability of practical-sized waterwheels.

The main difficulty of water wheels is their dependence on flowing water, which limits where they can be located. Modern hydroelectric dams can be viewed as the descendants of the water wheel, as they too take advantage of the movement of water downhill.

Types

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

Water wheels come in two basic designs:[4]

- a horizontal wheel with a vertical axle; or

- a vertical wheel with a horizontal axle.

The latter can be subdivided according to where the water hits the wheel into backshot (pitch-back[5]), overshot, breastshot, undershot, and stream-wheels.[6][7][8] The term undershot can refer to any wheel where the water passes under the wheel[9] but it usually implies that the water entry is low on the wheel.

Overshot and backshot water wheels are typically used where the available height difference is more than a couple of meters. Breastshot wheels are more suited to large flows with a moderate head. Undershot and stream wheel use large flows at little or no head.

There is often an associated millpond, a reservoir for storing water and hence energy until it is needed. Larger heads store more gravitational potential energy for the same amount of water so the reservoirs for overshot and backshot wheels tend to be smaller than for breast shot wheels.

Overshot and pitchback water wheels are suitable where there is a small stream with a height difference of more than 2 metres (6.5 ft), often in association with a small reservoir. Breastshot and undershot wheels can be used on rivers or high volume flows with large reservoirs.

Summary of types

[edit]Vertical axis also known as tub or Norse mills.

|

|

Stream (also known as free surface). Ship wheels are a type of stream wheel.

|

|

Undershot

|

|

Breastshot

|

|

Overshot

|

|

Backshot (also known as pitchback)

|

|

Vertical axis

[edit]

A horizontal wheel with a vertical axle.

Commonly called a tub wheel, Norse mill or Greek mill,[10][11] the horizontal wheel is a primitive and inefficient form of the modern turbine. However, if it delivers the required power then the efficiency is of secondary importance. It is usually mounted inside a mill building below the working floor. A jet of water is directed on to the paddles of the water wheel, causing them to turn. This is a simple system usually without gearing so that the vertical axle of the water wheel becomes the drive spindle of the mill.

Stream

[edit]

A stream wheel[6][12] is a vertically mounted water wheel that is rotated by the water in a water course striking paddles or blades at the bottom of the wheel. This type of water wheel is the oldest type of horizontal axis wheel.[citation needed] They are also known as free surface wheels because the water is not constrained by millraces or wheel pits. [citation needed]

Stream wheels are cheaper and simpler to build and have less of an environmental impact than other types of wheels. They do not constitute a major change of the river. Their disadvantages are their low efficiency, which means that they generate less power and can only be used where the flow rate is sufficient. A typical flat board undershot wheel uses about 20 percent of the energy in the flow of water striking the wheel as measured by English civil engineer John Smeaton in the 18th century.[13] More modern wheels have higher efficiencies.

Stream wheels gain little or no advantage from the head, a difference in water level.

Stream wheels mounted on floating platforms are often referred to as hip wheels and the mill as a ship mill. They were sometimes mounted immediately downstream from bridges where the flow restriction of the bridge piers increased the speed of the current.[citation needed]

Historically they were very inefficient but major advances were made in the eighteenth century.[14]

Undershot wheel

[edit]

An undershot wheel is a vertically mounted water wheel with a horizontal axle that is rotated by the water from a low weir striking the wheel in the bottom quarter. Most of the energy gain is from the movement of the water and comparatively little from the head. They are similar in operation and design to stream wheels.

The term undershot is sometimes used with related but different meanings:

- all wheels where the water passes under the wheel[15]

- wheels where the water enters in the bottom quarter.

- wheels where paddles are placed into the flow of a stream. See the stream above.[16][12]

This is the oldest type of vertical water wheel.

Breastshot wheel

[edit]

The word breastshot is used in a variety of ways. Some authors restrict the term to wheels where the water enters at about the 10 o’clock position, others 9 o’clock, and others for a range of heights.[17] In this article it is used for wheels where the water entry is significantly above the bottom and significantly below the top, typically the middle half.

They are characterized by:

- buckets carefully shaped to minimize turbulence as water enters

- buckets ventilated with holes in the side to allow air to escape as the water enters

- a masonry "apron" closely conforming to the wheel face, which helps contain the water in the buckets as they progress downwards

Both kinetic (movement) and potential (height and weight) energy are utilised.

The small clearance between the wheel and the masonry requires that a breastshot wheel has a good trash rack ('screen' in British English) to prevent debris from jamming between the wheel and the apron and potentially causing serious damage.

Breastshot wheels are less efficient than overshot and backshot wheels but they can handle high flow rates and consequently high power. They are preferred for steady, high-volume flows such as are found on the Fall Line of the North American East Coast. Breastshot wheels are the most common type in the United States of America[citation needed] and are said to have powered the industrial revolution.[14]

Overshot wheel

[edit]

A vertically mounted water wheel that is rotated by water entering buckets just past the top of the wheel is said to be overshot. The term is sometimes, erroneously, applied to backshot wheels, where the water goes down behind the wheel.

A typical overshot wheel has the water channeled to the wheel at the top and slightly beyond the axle. The water collects in the buckets on that side of the wheel, making it heavier than the other "empty" side. The weight turns the wheel, and the water flows out into the tail-water when the wheel rotates enough to invert the buckets. The overshot design is very efficient, it can achieve 90%,[18] and does not require rapid flow.

Nearly all of the energy is gained from the weight of water lowered to the tailrace although a small contribution may be made by the kinetic energy of the water entering the wheel. They are suited to larger heads than the other type of wheel so they are ideally suited to hilly countries. However even the largest water wheel, the Laxey Wheel in the Isle of Man, only utilises a head of around 30 m (100 ft). The world's largest head turbines, Bieudron Hydroelectric Power Station in Switzerland, utilise about 1,869 m (6,132 ft).

Overshot wheels require a large head compared to other types of wheel which usually means significant investment in constructing the headrace. Sometimes the final approach of the water to the wheel is along a flume or penstock, which can be lengthy.

Backshot wheel

[edit]

A backshot wheel (also called pitchback) is a variety of overshot wheel where the water is introduced just before the summit of the wheel. In many situations, it has the advantage that the bottom of the wheel is moving in the same direction as the water in the tailrace which makes it more efficient. It also performs better than an overshot wheel in flood conditions when the water level may submerge the bottom of the wheel. It will continue to rotate until the water in the wheel pit rises quite high on the wheel. This makes the technique particularly suitable for streams that experience significant variations in flow and reduces the size, complexity, and hence cost of the tailrace.

The direction of rotation of a backshot wheel is the same as that of a breastshot wheel but in other respects, it is very similar to the overshot wheel. See below.

Hybrid

[edit]Overshot and backshot

[edit]

Some wheels are overshot at the top and backshot at the bottom thereby potentially combining the best features of both types. The photograph shows an example at Finch Foundry in Devon, UK. The head race is the overhead timber structure and a branch to the left supplies water to the wheel. The water exits from under the wheel back into the stream.

Reversible

[edit]

A special type of overshot/backshot wheel is the reversible water wheel. This has two sets of blades or buckets running in opposite directions so that it can turn in either direction depending on which side the water is directed. Reversible wheels were used in the mining industry in order to power various means of ore conveyance. By changing the direction of the wheel, barrels or baskets of ore could be lifted up or lowered down a shaft or inclined plane. There was usually a cable drum or a chain basket on the axle of the wheel. It is essential that the wheel have braking equipment to be able to stop the wheel (known as a braking wheel). The oldest known drawing of a reversible water wheel was by Georgius Agricola and dates to 1556.

History

[edit]As in all machinery, rotary motion is more efficient in water-raising devices than oscillating motion.[19] In terms of power source, waterwheels can be turned by either human respectively animal force or by the water current itself. Waterwheels come in two basic designs, either equipped with a vertical or a horizontal axle. The latter type can be subdivided, depending on where the water hits the wheel paddles, into overshot, breastshot and undershot wheels. The two main functions of waterwheels were historically water-lifting for irrigation purposes and milling, particularly of grain. In case of horizontal-axle mills, a system of gears is required for power transmission, which vertical-axle mills do not need.

Ancient Near East

[edit]The water wheel first appeared in the ancient Near East,[20][21][22] specifically ancient Egypt, in the 4th century BC.[22][23][21] Elsewhere in the Near East, there is archaeological evidence indicating possible water wheel usage in West Asia during the 4th century BC,[24] but there is a lack of literary evidence for water wheel usage in Mesopotamia[25][26] prior to the 3rd century BC.[27][28] The water wheel was used in the Near East by the 3rd century BC for use in moving millstones and small-scale grain grinding.[20] Terry S. Reynolds suggests that the first water wheels were norias and, by the 2nd century BC, evolved into the vertical watermill in Syria and Asia Minor, from where it spread to Greece and the Roman Empire.[29] Water wheels were used in the Near East during the Hellenistic period between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC,[30] and the sāqiya spread rapidly across the Near East during this period.[31]

Water-lifting in Egypt

[edit]The compartmented water wheel comes in two basic forms, the wheel with compartmented body (Latin tympanum) and the wheel with compartmented rim or a rim with separate, attached containers.[19] The wheels could be either turned by men treading on its outside or by animals by means of a sakia gear.[32] While the tympanum had a large discharge capacity, it could lift the water only to less than the height of its own radius and required a large torque for rotating.[32] These constructional deficiencies were overcome by the wheel with a compartmented rim which was a less heavy design with a higher lift.[33]

Paddle-driven water-lifting wheels had appeared in ancient Egypt by the 4th century BC.[34][23] The Egyptians are credited with inventing the water wheel with attached pots, a water wheel with water compartments and a bucket chain, which ran over a pulley with buckets attached to it. The invention of the compartmentalized water wheel occurred in ancient Egypt around the 4th century BC, in a rural context, away from the metropolis of Hellenistic Alexandria, and then spread to other parts of North Africa.[22][23][21]

According to John Peter Oleson, both the compartmented wheel and the hydraulic noria appeared in Egypt by the 4th century BC, with the Sakia being invented there a century later. This is supported by archeological finds at Faiyum, where the oldest archeological evidence of a water-wheel has been found, in the form of a Sakia dating back to the 3rd century BC. A papyrus dating to the 2nd century BC also found in Faiyum mentions a water wheel used for irrigation, a 2nd-century BC fresco found at Alexandria depicts a compartmented Sakia, and the writings of Callixenus of Rhodes mention the use of a Sakia in Ptolemaic Egypt during the reign of Ptolemy IV in the late 3rd century BC.[35][23][21]

In Ptolemaic Egypt, water wheels were used between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC.[30] The earliest literary reference to a water-driven, compartmented wheel appears in a medieval Arabic translation of Pneumatica (chap. 61) by Philo of Byzantium (c. 280 – c. 220 BC), describing its use in Egyptian irrigation.[36] In his Parasceuastica (91.43−44), Philo advises the use of such wheels for submerging siege mines as a defensive measure against enemy sapping.[37] Unlike other water-lifting devices and pumps of the period, the invention of the compartmented wheel cannot be traced to any particular Hellenistic engineer and may have been made in the late 4th century BC in a rural Egyptian context away from the Hellenistic metropolis of Alexandria. The origins of water power is attributed to the reality of rural Egyptian life along the Nile, rather than the intellectual capital of Alexandria which had no stream suitable for driving a paddle wheel.[21] Compartmented wheels later appear to have been the means of choice for draining dry docks in Alexandria under the reign of Ptolemy IV (221−205 BC).[37] Several Greek papyri from Ptolemaic Egypt dated to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC mention the use of these wheels, but do not give further details.[37]

The earliest depiction of a compartmented wheel is from a tomb painting in Ptolemaic Egypt which dates to the 2nd century BC. It shows a pair of yoked oxen driving the wheel via a sakia gear, which is here for the first time attested, too.[38] The sakia gear system is already shown fully developed to the point that "modern Egyptian devices are virtually identical".[38] It is believed that scientists or technicians from the Museum of Alexandria may have been involved in its development.[39] An episode from the Alexandrian War in 48 BC tells of how Caesar's enemies employed geared waterwheels to pour sea water from elevated places on the position of the trapped Romans.[40]

Watermills

[edit]The invention of the watermill is a question open to scholarly discussion.[41] According to historian Helaine Selin, there is evidence indicating that the watermill originated from the Persian Empire before 350 BC, likely in what are today Iran or Iraq, originally for the purpose of grinding corn. There were quarries known for their millstones in Iran and on the upper Tigris in what is today Turkey. The mills invented at this date had horizontal, propeller-like water wheels that drove the millstones directly.[24] However, there is a lack of literary evidence of water wheels being used in Mesopotamia at the time.[25][26]

Taking indirect evidence into account from the work of the Greek technician Apollonius of Perge, the British historian of technology M.J.T. Lewis hypothesizes the appearance of the vertical-axle watermill to the early 3rd century BC, and the horizontal-axle watermill to around 240 BC, assigning Byzantium (in Asia Minor) and Alexandria (in Ptolemaic Egypt) as the places of invention.[42] However, Örjan Wikander notes the hypothesis is open to scholarly discussion.[41] A watermill is reported by the Greek geographer Strabon (c. 64 BC – c. AD 24) to have existed sometime before 71 BC in the palace of the Pontian king Mithradates VI Eupator, but its exact construction cannot be gleaned from the text (XII, 3, 30 C 556).[43]

China

[edit]

According to Joseph Needham and other historians, the text known as the Xin Lun written by Huan Tan about 20 AD (during the usurpation of Wang Mang) infers that water wheels had been used for pounding machinery in grain mills.[44][45][46] The Xin Lun states that the legendary mythological king known as Fu Xi was the one responsible for the pestle and mortar, which evolved into the tilt-hammer and then trip hammer device (see trip hammer). Although the author speaks of the mythological Fu Xi, a passage of his writing gives hint that the water wheel was in widespread use by the 1st century AD in China (Wade-Giles spelling):

Fu Hsi invented the pestle and mortar, which is so useful, and later on it was cleverly improved in such a way that the whole weight of the body could be used for treading on the tilt-hammer (tui), thus increasing the efficiency ten times. Afterwards the power of animals—donkeys, mules, oxen, and horses—was applied by means of machinery, and water-power too used for pounding, so that the benefit was increased a hundredfold.[45]

In the year 31 AD, the engineer and Prefect of Nanyang, Du Shi (d. 38), applied a complex use of the water wheel and machinery to power the bellows of the blast furnace to create cast iron. Du Shi is mentioned briefly in the Book of Later Han (Hou Han Shu) as follows (in Wade-Giles spelling):

In the seventh year of the Chien-Wu reign period (31 AD) Tu Shih was posted to be Prefect of Nanyang. He was a generous man and his policies were peaceful; he destroyed evil-doers and established the dignity (of his office). Good at planning, he loved the common people and wished to save their labor. He invented a water-power reciprocator (shui phai) for the casting of (iron) agricultural implements. Those who smelted and cast already had the push-bellows to blow up their charcoal fires, and now they were instructed to use the rushing of the water (chi shui) to operate it ... Thus the people got great benefit for little labor. They found the 'water(-powered) bellows' convenient and adopted it widely.[47]

According to the Book of Jin, Zhang Heng (78-139) invented a water-powered armillary sphere which could "turn around by water leakage" around 130. Later generations speculated that this meant a water wheel.[48]

According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms, the mechanical engineer Ma Jun (c. 200–265) from Cao Wei used a water wheel to power and operate a large mechanical puppet theater for Emperor Ming of Wei (r. 226–239).[49] The device was carved using large wood, wheel shaped, and operated parallel to the ground to lift water in order to drive an assortment of puppets as well as mills with pestle.[50] The Prefect Han Ji was made Superintendent of Metallurgical Production sometime before 238. He "adapted the furnace bellows to the use of ever-flowing water, and an efficiency three times greater than before was attained."[47] Twenty years later, a new design was introduced by a man named Du Yu.[47] A record dated to 263 or later mentions a device known as shui dui that made use of water wheels:

Beside the river, a shui dui is made, and water wheels are set behind it. A crosspiece is installed to run through the wheels. The two ends of the crosspiece are linked alternately to a long wood of about two chi and directly impact the rear wood of the shui dui. When the water is lifted to impact the wheel, the wheel will rotate, which drives the alternate wood to impact the rear wood of the shui dui to hull grain, using no manpower. The device is thus called shui dui.[44]

In the beginning of the Yuanjia era (424-429), an artificial lake was created for water powered blowing bellows used in smelting and casting works. However it was discovered that the earthworks of the lake leaked and were insufficient for their intended purpose. They were destroyed and replaced by man-powered "treadmill bellows".[51]

Roman Empire

[edit]A poem by Antipater of Thessalonica praised the water wheel for freeing women from the exhausting labor of milling and grinding.[52][53]

Around 300 AD, the noria was introduced when the wooden compartments were replaced with inexpensive ceramic pots that were tied to the outside of an open-framed wheel.[21]

Watermilling

[edit]

The first clear description of a geared watermill offers the late 1st century BC Roman architect Vitruvius who tells of the sakia gearing system as being applied to a watermill.[54] Vitruvius's account is particularly valuable in that it shows how the watermill came about, namely by the combination of the separate Greek inventions of the toothed gear and the waterwheel into one effective mechanical system for harnessing water power.[55] Vitruvius' waterwheel is described as being immersed with its lower end in the watercourse so that its paddles could be driven by the velocity of the running water (X, 5.2).[56]

About the same time, the overshot wheel appears for the first time in a poem by Antipater of Thessalonica, which praises it as a labour-saving device (IX, 418.4–6).[57] The motif is also taken up by Lucretius (ca. 99–55 BC) who likens the rotation of the waterwheel to the motion of the stars on the firmament (V 516).[58] The third horizontal-axled type, the breastshot waterwheel, comes into archaeological evidence by the late 2nd century AD context in central Gaul.[59] Most excavated Roman watermills were equipped with one of these wheels which, although more complex to construct, were much more efficient than the vertical-axle waterwheel.[60] In the 2nd century AD Barbegal watermill complex a series of sixteen overshot wheels was fed by an artificial aqueduct, a proto-industrial grain factory which has been referred to as "the greatest known concentration of mechanical power in the ancient world".[61]

In Roman North Africa, several installations from around 300 AD were found where vertical-axle waterwheels fitted with angled blades were installed at the bottom of a water-filled, circular shaft. The water from the mill-race which entered tangentially the pit created a swirling water column that made the fully submerged wheel act like true water turbines, the earliest known to date.[62]

Navigation

[edit]

Apart from its use in milling and water-raising, ancient engineers applied the paddled waterwheel for automatons and in navigation. Vitruvius (X 9.5–7) describes multi-geared paddle wheels working as a ship odometer, the earliest of its kind. The first mention of paddle wheels as a means of propulsion comes from the 4th–5th century military treatise De Rebus Bellicis (chapter XVII), where the anonymous Roman author describes an ox-driven paddle-wheel warship.[63]

Islamic world

[edit]

After the spread of Islam, engineers of the Islamic world continued the water technologies of the ancient Near East; as evident in the excavation of a canal in the Basra region with remains of a water wheel dating from the 7th century. Hama in Syria still preserves some of its large wheels, on the river Orontes, although they are no longer in use.[64] One of the largest had a diameter of about 20 metres (66 ft) and its rim was divided into 120 compartments. Another wheel that is still in operation is found at Murcia in Spain, La Nora, and although the original wheel has been replaced by a steel one, the Moorish system during al-Andalus is otherwise virtually unchanged. Some medieval Islamic compartmented water wheels could lift water as high as 30 metres (100 ft).[65] Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi's Kitab al-Hawi in the 10th century described a noria in Iraq that could lift as much as 153,000 litres per hour (34,000 imp gal/h), or 2,550 litres per minute (560 imp gal/min). This is comparable to the output of modern norias in East Asia, which can lift up to 288,000 litres per hour (63,000 imp gal/h), or 4,800 litres per minute (1,100 imp gal/min).[66]

The industrial uses of watermills in the Islamic world date back to the 7th century, while horizontal-wheeled and vertical-wheeled water mills were both in widespread use by the 9th century. A variety of industrial watermills were used in the Islamic world, including gristmills, hullers, sawmills, shipmills, stamp mills, steel mills, sugar mills, and tide mills. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Islamic world had these industrial watermills in operation, from al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia.[67] Muslim engineers also used crankshafts and water turbines, gears in watermills and water-raising machines, and dams as a source of water, used to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines.[68] Fulling mills and steel mills may have spread from Islamic Spain to Christian Spain in the 12th century. Industrial water mills were also employed in large factory complexes built in al-Andalus between the 11th and 13th centuries.[69]

The engineers of the Islamic world developed several solutions to achieve the maximum output from a water wheel. One solution was to mount them to piers of bridges to take advantage of the increased flow. Another solution was the shipmill, a type of water mill powered by water wheels mounted on the sides of ships moored in midstream. This technique was employed along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in 10th-century Iraq, where large shipmills made of teak and iron could produce 10 tons of flour from grain every day for the granary in Baghdad.[70] The flywheel mechanism, which is used to smooth out the delivery of power from a driving device to a driven machine, was invented by Ibn Bassal (fl. 1038–1075) of Al-Andalus; he pioneered the use of the flywheel in the saqiya (chain pump) and noria.[71] The engineers Al-Jazari in the 13th century and Taqi al-Din in the 16th century described many inventive water-raising machines in their technological treatises. They also employed water wheels to power a variety of devices, including various water clocks and automata.

Indian subcontinent

[edit]The early history of the watermill in the Indian subcontinent is obscure. Ancient Indian texts dating back to the 4th century BC refer to the term cakkavattaka (turning wheel), which commentaries explain as arahatta-ghati-yanta (machine with wheel-pots attached). On this basis, Joseph Needham suggested that the machine was a noria. Terry S. Reynolds, however, argues that the "term used in Indian texts is ambiguous and does not clearly indicate a water-powered device." Thorkild Schiøler argued that it is "more likely that these passages refer to some type of tread- or hand-operated water-lifting device, instead of a water-powered water-lifting wheel."[72]

According to Greek historical tradition, India received water-mills from the Roman Empire in the early 4th century AD when a certain Metrodoros introduced "water-mills and baths, unknown among them [the Brahmans] till then".[73] Irrigation water for crops was provided by using water raising wheels, some driven by the force of the current in the river from which the water was being raised. This kind of water raising device was used in ancient India, predating, according to Pacey, its use in the later Roman Empire or China,[74] though earlier literary, archaeological and pictorial evidence of the water wheel appeared in the Hellenistic world.[75]

Around 1150, the astronomer Bhaskara Achārya observed water-raising wheels and imagined such a wheel lifting enough water to replenish the stream driving it, effectively, a perpetual motion machine.[76] The construction of water works and aspects of water technology in India is described in Arabic and Persian works. During medieval times, the diffusion of Indian and Persian irrigation technologies gave rise to an advanced irrigation system which bought about economic growth and also helped in the growth of material culture.[77]

Ismail al-Jazari's Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (1206) uses the term "Sindhi wheel" to describe a sāqiya. This indicates it may have originated in the northwestern Indian subcontinent (modern Pakistan).[31] During the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526), geared water-raising wheels were introduced from the Islamic world to India.[78]

Medieval Europe

[edit]Early medieval Europe

[edit]Ancient water-wheel technology continued unabated in the early medieval period where the appearance of new documentary genres such as legal codes, monastic charters, but also hagiography was accompanied with a sharp increase in references to watermills and wheels.[79]

The earliest vertical-wheel in a tide mill is from 6th-century Killoteran near Waterford, Ireland,[80] while the first known horizontal-wheel in such a type of mill is from the Irish Little Island (c. 630).[81] As for the use in a common Norse or Greek mill, the oldest known horizontal-wheels were excavated in the Irish Ballykilleen, dating to c. 636.[81]

Cistercian monasteries, in particular, made extensive use of water wheels to power watermills of many kinds.[46] An early example of a very large water wheel is the still extant wheel at the early 13th century Real Monasterio de Nuestra Senora de Rueda, a Cistercian monastery in the Aragon region of Spain. Grist mills (for grain) were undoubtedly the most common, but there were also sawmills, fulling mills and mills to fulfil many other labour-intensive tasks. The water wheel remained competitive with the steam engine well into the Industrial Revolution. At around the 8th to 10th century, a number of irrigation technologies were brought into Spain and thus introduced to Europe. One of those technologies is the Noria, which is basically a wheel fitted with buckets on the peripherals for lifting water. It is similar to the undershot water wheel mentioned later in this article. It allowed peasants to power watermills more efficiently. According to Thomas Glick's book, Irrigation and Society in Medieval Valencia, the Noria probably originated from somewhere in Persia. It has been used for centuries before the technology was brought into Spain by Arabs who had adopted it from the Romans. Thus the distribution of the Noria in the Iberian peninsula "conforms to the area of stabilized Islamic settlement".[82]

Late medieval Europe

[edit]The assembly convened by William of Normandy, commonly referred to as the "Domesday" or Doomsday survey, took an inventory of all potentially taxable property in England, which included over six thousand mills spread across three thousand different locations,[83] up from less than a hundred in the previous century.[46]

The type of water wheel selected was dependent upon the location. Generally if only small volumes of water and high waterfalls were available a millwright would choose to use an overshot wheel. The decision was influenced by the fact that the buckets could catch and use even a small volume of water.[84] For large volumes of water with small waterfalls the undershot wheel would have been used, since it was more adapted to such conditions and cheaper to construct. So long as these water supplies were abundant the question of efficiency remained irrelevant. By the 18th century, with increased demand for power coupled with limited water locales, an emphasis was made on efficiency scheme.[84]

By the 11th century there were parts of Europe where the exploitation of water was commonplace.[83] The water wheel is understood to have actively shaped and forever changed the outlook of Westerners. Europe began to transit from human and animal muscle labor towards mechanical labor with the advent of the water wheel. Medievalist Lynn White Jr. contended that the spread of inanimate power sources was eloquent testimony to the emergence of the West of a new attitude toward, power, work, nature, and above all else technology.[83]

Harnessing water-power enabled gains in agricultural productivity, food surpluses and the large scale urbanization starting in the 11th century. The usefulness of water power motivated European experiments with other power sources, such as wind and tidal mills.[85] Waterwheels influenced the construction of cities, more specifically canals. The techniques that developed during this early period such as stream jamming and the building of canals, put Europe on a hydraulically focused path, for instance water supply and irrigation technology was combined to modify supply power of the wheel.[86]

The water mill was used for grinding grain, producing flour for bread, malt for beer, or coarse meal for porridge.[87]

Early modern Western world

[edit]Early modern Europe

[edit]Millwrights distinguished between the two forces, impulse and weight, at work in water wheels long before 18th-century Europe. Fitzherbert, a 16th-century agricultural writer, wrote "druieth the wheel as well as with the weight of the water as with strengthe [impulse]".[88] Leonardo da Vinci also discussed water power, noting "the blow [of the water] is not weight, but excites a power of weight, almost equal to its own power".[89] However, even realisation of the two forces, weight and impulse, confusion remained over the advantages and disadvantages of the two, and there was no clear understanding of the superior efficiency of weight.[90] Prior to 1750 it was unsure as to which force was dominant and was widely understood that both forces were operating with equal inspiration amongst one another.[91] The waterwheel sparked questions of the laws of nature, specifically the laws of force. Evangelista Torricelli's work on water wheels used an analysis of Galileo's work on falling bodies, that the velocity of a water sprouting from an orifice under its head was exactly equivalent to the velocity a drop of water acquired in falling freely from the same height.[92]

Industrial Europe

[edit]

The water wheel was a driving force behind the earliest stages of industrialization in Britain. Water-powered reciprocating devices were used in trip hammers and blast furnace bellows. Richard Arkwright's water frame was powered by a water wheel.[93]

North America

[edit]Water wheels were used to power sawmills, grist mills and for other purposes during development of the United States. The 40 feet (12 m) diameter water wheel at McCoy, Colorado, built in 1922, is a surviving one out of many which lifted water for irrigation out of the Colorado River.

Two early improvements were suspension wheels and rim gearing. Suspension wheels are constructed in the same manner as a bicycle wheel, the rim being supported under tension from the hub- this led to larger lighter wheels than the former design where the heavy spokes were under compression. Rim-gearing entailed adding a notched wheel to the rim or shroud of the wheel. A stub gear engaged the rim-gear and took the power into the mill using an independent line shaft. This removed the rotative stress from the axle which could thus be lighter, and also allowed more flexibility in the location of the power train. The shaft rotation was geared up from that of the wheel which led to less power loss. An example of this design pioneered by Thomas Hewes and refined by William Armstrong Fairburn can be seen at the 1849 restored wheel at the Portland Basin Canal Warehouse.[94]

Australia

[edit]

Australia has a relatively dry climate, nonetheless, where suitable water resources were available, water wheels were constructed in 19th-century Australia. These were used to power sawmills, flour mills, and stamper batteries used to crush gold-bearing ore. Notable examples of water wheels used in gold recovery operations were the large Garfield water wheel near Chewton—one of at least seven water wheels in the surrounding area—and the two water wheels at Adelong Falls; some remnants exist at both sites.[95][96][97][98] The mining area at Walhalla once had at least two water wheels, one of which was rolled to its site from Port Albert, on its rim using a novel trolley arrangement, taking nearly 90 days.[99] A water wheel at Jindabyne, constructed in 1847, was the first machine used to extract energy—for flour milling—from the Snowy River.[100]

Compact water wheels, known as Dethridge wheels, were used not as sources of power but to measure water flows to irrigated land.[101]

New Zealand

[edit]Water wheels were used extensively in New Zealand.[102] The well-preserved remains of the Young Australian mine's overshot water wheel exist near the ghost town of Carricktown,[103] and those of the Phoenix flour mill's water wheel are near Oamaru.[104]

Modern developments

[edit]A recent development of the breastshot wheel is a hydraulic wheel which effectively incorporates automatic regulation systems. The Aqualienne is one example. It generates between 37 kW and 200 kW of electricity from a 20 m3 (710 cu ft) waterflow with a head of 1 to 3.5 m (3 to 11 ft).[105] It is designed to produce electricity at the sites of former watermills.

Efficiency

[edit]Overshot (and particularly backshot) wheels are the most efficient type; a backshot steel wheel can be more efficient (about 60%) than all but the most advanced and well-constructed turbines. In some situations an overshot wheel is preferable to a turbine.[106]

The development of the hydraulic turbine wheels with their improved efficiency (>67%) opened up an alternative path for the installation of water wheels in existing mills, or redevelopment of abandoned mills.

The power of a wheel

[edit]The energy available to the wheel has two components:

- Kinetic energy – depends on how fast the water is moving when it enters the wheel

- Potential energy – depends on the change in height of the water between entry to and exit from the wheel

The kinetic energy can be accounted for by converting it into an equivalent head, the velocity head, and adding it to the actual head. For still water the velocity head is zero, and to a good approximation it is negligible for slowly moving water, and can be ignored. The velocity in the tail race is not taken into account because for a perfect wheel the water would leave with zero energy which requires zero velocity. That is impossible, the water has to move away from the wheel, and represents an unavoidable cause of inefficiency.

The power is how fast that energy is delivered which is determined by the flow rate. It has been estimated that the ancient donkey or slave-powered quern of Rome made about one-half of a horsepower, the horizontal waterwheel creating slightly more than one-half of a horsepower, the undershot vertical waterwheel produced about three horsepower, and the medieval overshot waterwheel produced up to forty to sixty horsepower.[107]

Quantities and units

[edit]- efficiency

- density of water (1000 kg/m3)

- cross sectional area of the channel (m2)

- diameter of wheel (m)

- power (W)

- distance (m)

- strength of gravity (9.81 m/s2 = 9.81 N/kg)

- head (m)

- pressure head, the difference in water levels (m)

- velocity head (m)

- velocity correction factor. 0.9 for smooth channels.[108]

- velocity (m/s)

- volume flow rate (m3/s)

- time (s)

Measurements

[edit]

The pressure head is the difference in height between the head race and tail race water surfaces. The velocity head is calculated from the velocity of the water in the head race at the same place as the pressure head is measured from. The velocity (speed) can be measured by the pooh sticks method, timing a floating object over a measured distance. The water at the surface moves faster than water nearer to the bottom and sides so a correction factor should be applied as in the formula below.[108]

There are many ways to measure the volume flow rate. Two of the simplest are:

- From the cross sectional area and the velocity. They must be measured at the same place but that can be anywhere in the head or tail races. It must have the same amount of water going through it as the wheel.[108]

- It is sometimes practicable to measure the volume flow rate by the bucket and stop watch method.[109]

Formulae

[edit]| Quantity | Formula |

|---|---|

| Power | [110] |

| Effective head | [111] |

| Velocity head | [112][111] |

| Volume flow rate | [108] |

| Water velocity (speed) | [108] |

Rules of thumb

[edit]Breast and overshot

[edit]| Quantity | Approximate formula |

|---|---|

| Power (assuming 70% efficiency) | |

| Optimal rotational speed | rpm[113] |

Traditional undershot wheels

[edit]| Quantity | Approximate formula[113] |

|---|---|

| Power (assuming 20% efficiency) | |

| Optimal rotational speed | rpm |

Hydraulic wheel part reaction turbine

[edit]A parallel development is the hydraulic wheel/part reaction turbine that also incorporates a weir into the centre of the wheel but uses blades angled to the water flow. The WICON-Stem Pressure Machine (SPM) exploits this flow.[114] Estimated efficiency 67%.

The University of Southampton School of Civil Engineering and the Environment in the UK has investigated both types of Hydraulic wheel machines and has estimated their hydraulic efficiency and suggested improvements, i.e. The Rotary Hydraulic Pressure Machine. (Estimated maximum efficiency 85%).[115]

These type of water wheels have high efficiency at part loads / variable flows and can operate at very low heads, < 1 m (3 ft 3 in). Combined with direct drive Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Alternators and power electronics they offer a viable alternative for low head hydroelectric power generation.

See also

[edit]- For devices to lift water for irrigation

- Devices to lift water for land drainage

Explanatory notes

[edit]^ Dotted notation. A dot above the quantity indicates that it is a rate. In other how much each second or how much per second. In this article q is a volume of water and is a volume of water per second. q, as in quantity of water, is used to avoid confusion with v for velocity.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Dictionary definition of "tailrace"

- ^ Musson; Robinson (1969). Science and Technology in the Industrial Revolution. University of Toronto Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780802016379.

- ^ a b Thomson, Ross (2009). Structures of Change in the Mechanical Age: Technological Invention in the United States 1790–1865. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8018-9141-0.

- ^ "Types of Water Wheels – The Physics of a Water Wheel". ffden-2.phys.uaf.edu. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ^ pitch-back

- ^ a b "Stream wheel term and specifics". Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- ^ Merriam Webster

- ^ Power in the Landscape

- ^ Collins English Dictionary

- ^ Denny, Mark (2007). Ingenium: Five Machines That Changed the World. Johns Hopkins University. ISBN 9780801885860. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ "Waterwheel". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ a b Power in the landscape. "Types of water wheels". Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ The History of Science and Technology by Bryan Bunch with Alexander Hellmans p. 114

- ^ a b The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (December 2006). "Noria al-Muhammadiyya". The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 12 Feb 2017.

- ^ Collins English Dictionary. "undershot". Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Merriam Webster. "stream wheel".

- ^ Müller, G.; Wolter, C. (2004). "The breastshot waterwheel: design and model tests" (PDF). Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Engineering Sustainability. 157 (4): 203–211. doi:10.1680/ensu.2004.157.4.203. ISSN 1478-4629. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-02-11. Retrieved 2022-03-04 – via Semantic Scholar.

- ^ "What type of water wheel is most efficient?". faq-ans.com. 2021-04-12. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ a b Oleson 2000, p. 229

- ^ a b Adriana de Miranda (2007), Water architecture in the lands of Syria: the water-wheels, L'Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 37–8, ISBN 978-8882654337

- ^ a b c d e f Oleson 2000, pp. 235–6

- ^ a b c Stavros I. Yannopoulos, Gerasimos Lyberatos, Nicolaos Theodossiou, Wang Li, Mohammad Valipour, Aldo Tamburrino, Andreas N. Angelakis (2015). "Evolution of Water Lifting Devices (Pumps) over the Centuries Worldwide". Water. 7 (9). MDPI: 5031–5060. doi:10.3390/w7095031.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Ahmed, Abdelkader T.; El Gohary, Fatma; Tzanakakis, Vasileios A.; Angelakis, Andreas N. (January 2020). "Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times". Sustainability. 12 (22): 9760. doi:10.3390/su12229760. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ a b Selin, Helaine (2013). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Westen Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 282. ISBN 9789401714167.

- ^ a b As for a Mesopotamian connection: Schioler 1973, p. 165−167:

References to water-wheels in ancient Mesopotamia, found in handbooks and popular accounts, are for the most part based on the false assumption that the Akkadian equivalent of the logogram GIS.APIN was nartabu and denotes an instrument for watering ("instrument for making moist").

As a result of his investigations, Laessoe writes as follows on the question of the saqiya: "I consider it unlikely that any reference to the saqiya will appear in ancient Mesopotamian sources." In his opinion, we should turn our attention to Alexandria, "where it seems plausible to assume that the saqiya was invented."

- ^ a b Adriana de Miranda (2007), Water architecture in the lands of Syria: the water-wheels, L'Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 48f, ISBN 978-8882654337 concludes that the Akkadian passages "are counched in terms too general too allow any conclusion as to the excat structure" of the irrigation apparatus, and states that "the latest official Chicago Assyrian Dictionary reports meanings not related to types of irrigation system".

- ^ Oleson 2000, pp. 235:

The sudden appearance of literary and archaological evidence for the compartmented wheel in the third century B.C. stand in marked contrast to the complete absence of earlier testimony, suggesting that the device was invented not long before.

- ^ An isolated passage in the Hebrew Deuteronomy (11.10−11) about Egypt as a country where you sowed your seed and watered it with your feet is interpreted as an metaphor referring to the digging of irrigation channels rather than treading a waterwheel (Oleson 2000, pp. 234).

- ^ Terry S. Reynolds (2003), Stronger Than a Hundred Men: A History of the Vertical Water Wheel, Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 25, ISBN 0801872480

- ^ a b Wikander 2000, p. 395; Oleson 2000, p. 229

It is no surprise that all the water-lifting devices that depend on subdivided wheels or cylinders originate in the sophisticated, scientifically advanced Hellenistic period, ...

- ^ a b Hill, Donald Routledge (1974). The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (Kitab fi Ma'rifat al-Hiyal al-Handasiyya) by ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari. D. Reidel Publishing Company. pp. 273–4.

- ^ a b Oleson 2000, p. 230

- ^ Oleson 2000, pp. 231f.

- ^ Örjan Wikander (2008). "Chapter 6: Sources of Energy and Exploitation of Power". In John Peter Oleson (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World. Oxford University Press. pp. 141–2. ISBN 978-0-19-518731-1.

- ^ Adriana de Miranda (2007). Water architecture in the lands of Syria: the water-wheels. L'Erma di Bretschneider. pp. 38–9. ISBN 978-88-8265-433-7.

- ^ Oleson 2000, p. 233

- ^ a b c Oleson 2000, pp. 234

- ^ a b Oleson 2000, pp. 234, 270

- ^ Oleson 2000, pp. 271f.

- ^ Oleson 2000, p. 271

- ^ a b Wikander 2000, pp. 394–6

- ^ Wikander 2000, p. 396f.; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 11; Wilson 2002, pp. 7f.

- ^ Wikander 1985, p. 160; Wikander 2000, p. 396

- ^ a b Huang & Zhang 2020, p. 298.

- ^ a b Needham 1965, p. 392.

- ^ a b c Hansen, Roger D. (2005). "Water Wheels" (PDF). waterhistory.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Needham 1965, p. 370.

- ^ Huang & Zhang 2020, p. 304.

- ^ Needham 1965, p. 158.

- ^ Huang & Zhang 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Needham 1965, p. 371-372.

- ^ Jahren, Per; Sui, Tongbo (2016-11-22). How Water Influences Our Lives. Springer. ISBN 978-981-10-1938-8.

- ^ "Antipater of Thessalonica: Epigrams - translation". www.attalus.org. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ Oleson 2000, pp. 234, 269

- ^ Oleson 2000, pp. 269−271

- ^ Wikander 2000, p. 373f.; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 12

- ^ Wikander 2000, p. 375; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 13

- ^ Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 11; Oleson 2000, p. 236

- ^ Wikander 2000, p. 375

- ^ Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, pp. 12f.

- ^ Greene 2000, p. 39

- ^ Wilson 1995, pp. 507f.; Wikander 2000, p. 377; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 13

- ^ De Rebus Bellicis (anon.), chapter XVII, text edited by Robert Ireland, in: BAR International Series 63, part 2, p. 34

- ^ al-Hassani et al., p. 115

- ^ Lucas, Adam (2006), Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology, Brill Publishers, p. 26, ISBN 978-90-04-14649-5

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill (1996), A history of engineering in classical and medieval times, Routledge, pp. 145–6, ISBN 978-0-415-15291-4

- ^ Lucas, p. 10

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering Archived 2019-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lucas, p. 11

- ^ Hill; see also Mechanical Engineering Archived 2000-12-12 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Flywheel Effect for a Saqiya Archived 2007-12-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Reynolds, p. 14

- ^ Wikander 2000, p. 400:

This is also the period when water-mills started to spread outside the former Empire. According to Cedrenus (Historiarum compendium), a certain Metrodoros who went to India in c. A.D. 325 "constructed water-mills and baths, unknown among them [the Brahmans] till then".

- ^ Pacey, p. 10

- ^ Oleson 1984, pp. 325ff.; Oleson 2000, pp. 217–302[page range too broad]; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, pp. 10−15[page range too broad]; Wikander 2000, pp. 371−400[page range too broad]

- ^ Pacey, p. 36

- ^ Siddiqui

- ^ Pacey, Arnold (1991) [1990]. Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History (1st MIT Press paperback ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp. 26–29.

- ^ Wikander 2000, p. 372f.; Wilson 2002, p. 3

- ^ Murphy 2005

- ^ a b Wikander 1985, pp. 155–157

- ^ Glick, p. 178

- ^ a b c Robert, Friedel, A Culture of Improvement. MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England. (2007). pp. 31–2b.

- ^ a b Howard, Robert A. (1983). "Primer on Water Wheels". Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. 15 (3): 26–33. doi:10.2307/1493973. JSTOR 1493973.

- ^ Terry S, Reynolds, Stronger than a Hundred Men; A History of the Vertical Water Wheel. Baltimore; Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Robert, Friedel, A Culture of Improvement. MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England. (2007). p. 33.

- ^ Robert, Friedel, A Culture of Improvement. MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England. (2007). p. 34

- ^ Robert, Friedel, A Culture of Improvement. MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England. (2007)

- ^ Anthony Fitzherbert, Surveying (London, 1539, reprinted in [Robert Vansitarrt, ed] Certain Ancient Tracts Concerning the Management of Landed Property Reprinted [London, 1767.] pg. 92.

- ^ Leonardo da Vinci, MS F, 44r, in Les manuscrits de Leonardo da Vinci, ed Charles Ravaisson-Moilien (Paris, 1889), vol.4; cf, Codex Madrid, vol. 1, 69r [The Madrid Codices], trans. And transcribed by Ladislao Reti (New York, 1974), vol. 4.

- ^ Smeaton, "An Experimental Inquiry Concerning the Natural Powers of Water and Wind to Turn Mills, and Other Machines, depending on Circular Motion," Royal Society, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 51 (1759); 124–125

- ^ Torricelli, Evangelista, Opere, ed. Gino Loria and Giuseppe Vassura (Rome, 1919.)

- ^ Torricella, Evangelica, Opere, ed. Gino Loria and Giuseppe Vassura (Rome, 1919.)

- ^ "Hydro Power from the Early Modern to the Industrial Age: Ca. 1500–1850 - Electricity & Alternative Energy - Alberta's Energy Heritage". Archived from the original on 2019-11-15.

- ^ *Nevell, Mike; Walker (2001). Portland Basin and the archaeology of the Canal Warehouse. Tameside Metropolitan Borough with University of Manchester Archaeological Unit. ISBN 978-1-871324-25-9.

- ^ Davies, Peter; Lawrence, Susan (2013). "The Garfield water wheel: hydraulic power on the Victorian goldfields" (PDF). Australasian Historical Archaeology. 31: 25–32.

- ^ "Garfield Water Wheel". www.goldfieldsguide.com.au. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ "Adelong Falls Gold Workings/Reserve". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00072. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ Pearson, Warwick (1997). "Water-Powered Flourmills in Nineteenth-Century Tasmania" (PDF). Australasian Historical Archaeology. 15: 66–78.

- ^ "Walhalla's Water Wheels". www.walhalla.org.au. Archived from the original on 2022-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- ^ "THE SOIL". Daily Telegraph. 1918-06-10. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ McNicoll, Ronald, "Dethridge, John Stewart (1865–1926)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 2022-02-06

- ^ "Watermills and waterwheels of New Zealand". www.windmillworld.com. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ COMB (2014-09-03). "Young Australian Water Wheel". DigitalNZ. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ "Water wheel of mill nears restoration". Otago Daily Times Online News. 2015-09-19. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ "Comment fonctionne une Aqualienne?" (in French). Archived from the original on 2017-07-11.

- ^ For a discussion of the different types of water wheels, see Syson, pp. 76–91

- ^ Gies, Frances; Gies, Joseph (1994). Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel: Technology and Invention in the Middle Ages. HarperCollins Publishers. p. 115. ISBN 0060165901.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e "Float Method for Estimating Discharge". United States Forest Service. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Michaud, Joy P.; Wierenga, Marlies. "Estimating Discharge and Stream Flows" (PDF). State of Washington. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "Calculation of Hydro Power". The Renewable Energy Website. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ a b Nagpurwala, Q.H. "Hydraulic Turbines". M.S. Ramaiah School of Advanced Studies. p. 44. Retrieved 25 February 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Velocity Head". Neutrium. September 27, 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Waterwheels". British Hydropower Association. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- ^ Oewatec

- ^ Low Head Hydro

General references

[edit]- Soto Gary, Water Wheel. vol. 163. No. 4. (Jan., 1994), p. 197

- al-Hassani, S.T.S., Woodcock, E. and Saoud, R. (2006) 1001 inventions : Muslim heritage in our world, Manchester: Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation, ISBN 0-9552426-0-6

- Allan. April 18, 2008. Undershot Water Wheel

- Donners, K.; Waelkens, M.; Deckers, J. (2002), "Water Mills in the Area of Sagalassos: A Disappearing Ancient Technology", Anatolian Studies, vol. 52, Anatolian Studies, Vol. 52, pp. 1–17, doi:10.2307/3643076, JSTOR 3643076, S2CID 163811541

- Glick, T.F. (1970) Irrigation and society in medieval Valencia, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-46675-6

- Greene, Kevin (2000), "Technological Innovation and Economic Progress in the Ancient World: M.I. Finley Re-Considered", The Economic History Review, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 29–59, doi:10.1111/1468-0289.00151, hdl:10.1111/1468-0289.00151

- Hill, D.R. (1991) "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", Scientific American, 264 (5:May), pp. 100–105

- Huang, Xing; Zhang, Xing (2020), "11 Water Wheel", Thirty Great Inventions of China: From Millet Agriculture to Artemisinin, Springer

- Lucas, A.R. (2005). "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe". Technology and Culture. 46 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1353/tech.2005.0026. S2CID 109564224.

- Lewis, M.J.T. (1997) Millstone and Hammer: the origins of water power, University of Hull Press, ISBN 0-85958-657-X

- Morton, W.S. and Lewis, C.M. (2005) China: Its History and Culture, 4th Ed., New York : McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-141279-4

- Murphy, Donald (2005), Excavations of a Mill at Killoteran, Co. Waterford as Part of the N-25 Waterford By-Pass Project (PDF), Estuarine/ Alluvial Archaeology in Ireland. Towards Best Practice, University College Dublin and National Roads Authority, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-18, retrieved 2010-03-17

- Needham, Joseph (1965), Science and Civilization in China – Vol. 4: Physics and physical technology – Part 2: Mechanical engineering, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-05803-1

- Nuernbergk, D.M. (2005) Wasserräder mit Kropfgerinne: Berechnungsgrundlagen und neue Erkenntnisse, Detmold : Schäfer, ISBN 3-87696-121-1

- Nuernbergk, D.M. (2007) Wasserräder mit Freihang: Entwurfs- und Berechnungsgrundlagen, Detmold : Schäfer, ISBN 3-87696-122-X

- Pacey, A. (1991) Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-year History, 1st MIT Press ed., Cambridge, Massachusetts : MIT, ISBN 0-262-66072-5

- Oleson, John Peter (1984), Greek and Roman Mechanical Water-Lifting Devices: The History of a Technology, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-90-277-1693-4

- Quaranta Emanuele, Revelli Roberto (2015), "Performance characteristics, power losses and mechanical power estimation for a breastshot water wheel", Energy, 87, Energy, Elsevier: 315–325, Bibcode:2015Ene....87..315Q, doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.04.079

- Oleson, John Peter (2000), "Water-Lifting", in Wikander, Örjan (ed.), Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, Technology and Change in History, vol. 2, Leiden: Brill, pp. 217–302, ISBN 978-90-04-11123-3

- Reynolds, T.S. (1983) Stronger Than a Hundred Men: A History of the Vertical Water Wheel, Johns Hopkins studies in the history of technology: New Series 7, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-2554-7

- Schioler, Thorkild (1973), Roman and Islamic Water-Lifting Wheels, Odense University Press, ISBN 978-87-7492-090-8

- Shannon, R. 1997. "Water Wheel Engineering". Archived from the original on 2017-09-20..

- Siddiqui, Iqtidar Husain (1986). "Water Works and Irrigation System in India during Pre-Mughal Times". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 29 (1): 52–77. doi:10.1163/156852086X00036.

- Syson, l. (1965) British Water-mills, London : Batsford, 176 p.

- Wikander, Örjan (1985), "Archaeological Evidence for Early Water-Mills. An Interim Report", History of Technology, vol. 10, pp. 151–179

- Wikander, Örjan (2000), "The Water-Mill", in Wikander, Örjan (ed.), Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, Technology and Change in History, vol. 2, Leiden: Brill, pp. 371–400, ISBN 978-90-04-11123-3

- Wilson, Andrew (1995), "Water-Power in North Africa and the Development of the Horizontal Water-Wheel", Journal of Roman Archaeology, vol. 8, pp. 499–510

- Wilson, Andrew (2002), "Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy", The Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 92, [Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, Cambridge University Press], pp. 1–32, doi:10.2307/3184857, JSTOR 3184857, S2CID 154629776

External links

[edit]- Glossary of water wheel terms

- Essay/audio clip

- WaterHistory.org Several articles concerning water wheels

- Computer simulation of an undershot water wheel Archived 2009-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Persian Wheel in India, 1814–1815 Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine painting with explanatory text, at British Library website.

- Computer simulation of an overshot water wheel Archived 2009-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Guide to the Water Wheel Construction: A Thesis Presented to N.C. College of Agri. and Mech. Arts by L. T. Yarbrough 1893 June

- Foundry Patterns for 18 different Welsh waterwheel shrouds- 2015

Water wheel

View on GrokipediaTypes

Vertical-axle water wheels

Vertical-axle water wheels, also known as noria-type or impulse wheels, consist of a horizontal wheel plane rotating around a vertical axle, with water directed radially onto blades or buckets to produce motion. This design contrasts with horizontal-axle wheels by emphasizing vertical lift and radial water impact rather than tangential flow along the wheel's circumference. The mechanism relies on water jets or channels from an elevated source striking the wheel's periphery, causing rotation through impulse forces that turn the central shaft.[4] Key components include the sturdy central vertical shaft, which serves as the axle and power transmission element, often supported by bearings or piers; radial blades or flat paddles for impulse reception in stream-driven variants; and buckets, pots, or compartments attached to the rim for capturing and lifting water. In animal- or human-powered versions, gears or pegs on a horizontal sweep wheel connect to the vertical axle for torque application. Water supply systems, such as flumes or nozzles, ensure precise delivery to minimize spillage.[5][6] Prominent historical examples include the noria, invented around the 3rd century BCE in Hellenistic Egypt for irrigation and water lifting, which spread widely through the Roman Empire and to the Islamic world by the 9th century CE, with notable installations like those in Hama, Syria, and Córdoba, Spain. The saqiya, or Persian wheel, an animal-powered variant originating in the Persian Empire around 500 BCE, features a vertical wheel with an endless chain of earthenware pots that fill at the bottom and discharge at the top, enabling continuous lifting up to 20 meters for agricultural use in arid regions. In China, the dragon backbone water lift, a vertical-axle chain pump developed during the Eastern Han dynasty (ca. 1st–2nd century CE), employed linked compartments or scoops on a rotating chain to raise water from rivers or wells, primarily for irrigation rather than direct mechanical power generation. These devices marked early innovations in hydraulic engineering, prioritizing water elevation over rotary output.[7][6][4] Vertical-axle water wheels excel in high-head, low-flow environments, such as steep streams or wells, where their radial impact design efficiently converts limited water volume into vertical lift, supporting irrigation in water-scarce areas without requiring large flows. However, they suffer from lower overall efficiency—typically 50–70% in historical contexts—due to energy dissipation from water splashing, air entrainment, and frictional losses on the vertical shaft and buckets, making them less suitable for high-power mechanical applications compared to horizontal-axle alternatives.[4][5]Horizontal-axle undershot and stream wheels

Horizontal-axle undershot water wheels feature a vertical wheel mounted on a horizontal axle, with open paddles or flat blades positioned primarily on the lower half to interact with flowing water.[8] The water impinges directly on these blades from below, propelling the wheel through direct contact with the stream's current.[8] A variant known as the stream wheel operates by partially submerging the wheel in a river's natural flow, eliminating the need for a dam or headrace and making it suitable for low-head, high-flow environments where water velocity is consistent but elevation drop is minimal.[9] These wheels are typically constructed from wood for simplicity and cost-effectiveness, though metal components have been used in later designs for durability.[10] In operation, undershot and stream wheels function on an impulse principle, where the kinetic energy of the water's velocity transfers momentum to the blades, causing rotation without relying on gravitational potential.[11] This direct-drive mechanism transmits power via the horizontal axle to connected machinery, such as millstones.[12] As the oldest form of water wheel, undershot designs date to the 1st century BCE in the Roman Empire, where they were employed for grain grinding.[13] The Roman architect Vitruvius provided the earliest detailed description of an undershot wheel in his De Architectura around 25 BCE, outlining its use in a right-angle geared system for milling.[12] These wheels remained common in medieval Europe for powering grain mills and, by the 12th century, early sawmills that processed timber using the stream's flow.[14] Undershot and stream wheels offer advantages including low maintenance due to their robust, simple construction and adaptability to natural streams without extensive infrastructure.[10] However, they suffer from low efficiency, historically around 20-30% as measured by 18th-century engineer John Smeaton, owing to energy losses from water splash and drag on the returning blades.[15] This compares unfavorably to overshot wheels, which achieve up to 60-70% efficiency by incorporating gravitational potential.[15]Horizontal-axle breastshot wheels

Horizontal-axle breastshot wheels direct water into the buckets at the mid-height of the wheel, typically through a breast or side channel aligned with the horizontal axis, allowing the water to enter near the center of the wheel's diameter. The buckets are often flat but can be curved for improved performance, and the wheel features partial enclosure along the entry side to contain the water and reduce backflow or spillage. This configuration balances the impulse from the water's velocity with the reaction force from its weight, enabling operation under moderate hydraulic heads of 1.5 to 4 meters and requiring a relatively steady flow rate for optimal function.[16][17] In the 18th and 19th centuries, breastshot wheels were commonly constructed using wooden frames reinforced with iron rims to withstand the stresses of continuous operation, though later examples incorporated more cast iron components for enhanced durability. French engineer Jean-Victor Poncelet contributed to better performance in the 1820s by advocating curved buckets that minimized water impact and improved energy transfer, an advancement that influenced breastshot designs beyond his primary focus on undershot wheels. As an evolution from undershot wheels, the breastshot configuration captures more potential energy by elevating the entry point, thereby increasing torque without requiring excessive head.[18] These wheels achieved efficiencies of around 50-60% in historical applications, making them suitable for sites with variable flows where overshot designs might falter due to inconsistent water levels. Their primary advantages include adaptability to moderate conditions and reduced vulnerability to flooding compared to higher-entry wheels, though they necessitate a dam or weir to maintain the required head and channel the flow effectively. Breastshot wheels gained popularity in 18th-century France and Britain, particularly powering textile mills such as those for flax processing at sites like Castleford Mills in England, where they drove machinery for spinning and weaving operations.[19][20]Horizontal-axle overshot and backshot wheels

Horizontal-axle overshot water wheels feature water supplied at or near the top of the wheel via a flume, allowing the water to fill individual closed buckets positioned on the wheel's rim. The weight of the accumulated water in these buckets generates torque, causing the wheel to rotate under the force of gravity as the filled buckets descend. This design maximizes the use of gravitational potential energy, distinguishing it from lower-entry configurations.[21] These wheels are typically constructed with large diameters, often reaching up to 10 meters, using wooden frameworks reinforced with iron fittings for durability and to support the substantial load. They require a significant head, or vertical drop, of 4 to 10 meters to effectively deliver water to the top, necessitating careful site preparation such as dams or leats to achieve the necessary elevation. The closed bucket design prevents premature spillage, ensuring the water's weight acts over the full descent.[21][22] Overshot wheels offer the highest efficiency among traditional water wheel types, achieving about 65 percent under optimal conditions, primarily due to minimal energy loss from water velocity and effective harnessing of potential energy. Their slow rotational speed facilitates direct gearing to machinery without complex speed-increasing mechanisms, making them suitable for applications like milling. However, the need for substantial elevation and large-scale construction results in high initial costs and limits their use to sites with adequate topography.[21][23] The overshot design was in use by Roman times and became prominent in medieval Europe.[21] The backshot variant modifies the overshot principle by directing water to enter the buckets just before the top on the ascending side, causing the wheel to rotate in the opposite direction to a standard overshot while maintaining a similar downward flow path and efficiency of about 65 percent. This configuration was particularly employed in 19th-century Scotland, where it enabled reversible operation to adapt to varying power needs in mills.[24][23]Hybrid and reversible designs

Hybrid overshot-backshot water wheels integrate elements of both top-entry and rear-entry water delivery to accommodate fluctuating water levels in the headrace, allowing the mechanism to switch between overshot operation—where water pours over the top—for high heads and backshot configuration—where water enters just behind the wheel's summit—for lower heads, thereby maintaining consistent power output without structural alterations.[22] This adaptability stems from adjustable flumes or nozzles that redirect flow, optimizing the wheel's torque under variable conditions while leveraging the high efficiency potential of overshot designs.[25] Reversible water wheels feature bidirectional rotation capabilities, enabling operation in tidal streams or dual-flow environments such as reversing river currents, typically achieved through dual sets of oppositely oriented buckets and adjustable gates that alternate water entry to drive the wheel in either direction without mechanical reconfiguration.[26] For instance, in tidal applications, these wheels use reversible gearing in the power train to harness both ebb and flood tides, generating power for up to 18 hours daily by flipping rotation via gear mechanisms patented in the late 19th century.[27] A notable early example is the 1875 U.S. Patent for an improvement in reversible water wheels, which allowed vertical positioning as a breast wheel while enabling reversal for versatile hydraulic use.[28] Other variants include dual-wheel systems, where two wheels are connected via a shared shaft to amplify power from limited flows, and pony wheels—smaller auxiliary units providing supplementary torque to primary wheels during low-flow periods.[29] These configurations enhance overall system reliability in intermittent water sources. Design innovations in the 19th century focused on gear reversals for seamless direction changes, as seen in patents adapting wheels for mining hoists where flow direction varied.[30] In modern applications, composite materials such as fiberglass-reinforced polymers have been incorporated into wheel buckets and frames to improve durability against corrosion and wear in micro-hydro setups, extending service life in harsh aquatic environments.[31] These hybrid and reversible designs offer key advantages in adaptability to fluctuating hydrological conditions, such as seasonal streams or tidal cycles, but introduce disadvantages like increased mechanical complexity, which can raise maintenance demands and initial costs.[30] Reversible backshot wheels, for example, were employed in 19th-century mining operations like the Grube Samson silver mine in Germany, where a 9-meter-diameter wheel hoisted ore from depths up to 700 meters by reversing via water flow adjustments.[30] Hybrid variants have seen revival in 20th-century micro-hydro projects, such as the reinstatement of historic wheels for low-head electricity generation in rural settings.[32]Operation and Efficiency

Mechanics of operation