Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anointing

View on Wikipedia

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.[1] By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or other fat.[2] Scented oils are used as perfumes and sharing them is an act of hospitality. Their use to introduce a divine influence or presence is recorded from the earliest times; anointing was thus used as a form of medicine, thought to rid persons and things of dangerous spirits and demons which were believed to cause disease.

In present usage, "anointing" is typically used for ceremonial blessings such as the coronation of European monarchs. This continues an earlier Hebrew practice most famously observed in the anointings of Aaron as high priest and both Saul and David by the prophet Samuel. The concept is important to the figure of the Messiah or the Christ (Hebrew and Greek[3] for "The Anointed One") who appear prominently in Jewish and Christian theology and eschatology. Anointing—particularly the anointing of the sick—may also be known as unction; the anointing of the dying as part of last rites in the Catholic church is sometimes specified as "extreme unction".

Name

[edit]The present verb derives from the now obsolete adjective anoint, equivalent to anointed.[4] The adjective is first attested in 1303,[n 1] derived from Old French enoint, the past participle of enoindre, from Latin inung(u)ere,[6] an intensified form of ung(u)ere 'to anoint'. It is thus cognate with "unction".

The oil used in a ceremonial anointment may be called "chrism", from Greek χρῖσμα (khrîsma) 'anointing'.[7]

Purpose

[edit]Anointing served and serves three distinct purposes: it is regarded as a means of health and comfort, as a token of honor, and as a symbol of consecration.[1] It seems probable that its sanative purposes were enjoyed before it became an object of ceremonial religion, but the custom appears to predate written history and the archaeological record, and its genesis is impossible to determine with certainty.[1]

Health

[edit]Used in conjunction with bathing, anointment with oil closes pores. It was regarded as counteracting the influence of the sun, reducing sweating. Aromatic oils naturally masked body and other offensive odors.[1]

Applications of oils and fats are also used as traditional medicines. The Bible records olive oil being applied to the sick and poured into wounds.[n 2][11] Known sources date from times when anointment already served a religious function; therefore, anointing was also used to combat the malicious influence of demons in Persia, Armenia, and Greece.[2] Anointing was also understood to "seal in" goodness and resist corruption, probably via analogy with the use of a top layer of oil to preserve wine in ancient amphoras, its spoiling usually being credited to demonic influence.[12]

For sanitary and religious reasons, the bodies of the dead are sometimes anointed.[n 3][11] In medieval and early modern Christianity, the practice was particularly associated with protection against vampires and ghouls who might otherwise take possession of the corpse.[12]

Hospitality

[edit]Anointing guests with oil as a mark of hospitality and token of honor is recorded in Egypt, Greece, and Rome, as well as in the Hebrew scriptures.[1] It was a common custom among the ancient Hebrews[n 4] and continued among the Arabs into the 20th century.[11]

Religion

[edit]In the sympathetic magic common to prehistoric and primitive religions, the fat of sacrificial animals and persons is often reckoned as a powerful charm, second to blood as the vehicle and seat of life.[2][18] East African Arabs traditionally anointed themselves with lion's fat to gain courage and provoke fear in other animals. Australian Aborigines would rub themselves with a human victim's caul fat to gain his powers.[2]

In religions like Christianity where animal sacrifice is no longer practiced, it is common to consecrate the oil in a special ceremony.[12]

Egypt

[edit]According to scholars belonging to the early part of the twentieth century (Wilhelm Spiegelberg,[19] Bonnet,[20] Cothenet,[21] Kutsch,[22] Martin-Pardey[23]) officials of ancient Egypt were anointed as part of a ceremony that installed them into office. This assumption has been questioned by scholars like Stephen Thompson, who doubt such anointing ever existed:[24]

After a review of the evidence for the anointing of officials in ancient Egypt as a part of their induction into office, I must conclude that there is no evidence that such a ceremony was ever practiced in ancient Egypt. Attempts to trace the origin of the Hebrew practice of anointing kings to an Egyptian source are misdirected. The only definite case in which an Egyptian king anointed one of his officials is that of EA 51. In this instance, it is probable that Thutmosis III was engaging in a custom common among Asiatics, rather than that he was introducing an Egyptian custom into Syria-Palestine

Anointment of the corpse with scented oils was however a well attested practice as an important part of mummification.[25]

India

[edit]

In Indian religion, late Vedic rituals developed involving the anointing of government officials, worshippers, and idols. These are now known as abhisheka. The practice spread to Indian Buddhists.[citation needed] In modern Hinduism and Jainism, anointment is common, although the practice typically employs water or yoghurt, milk, or (particularly) butter[2] from the holy cow, rather than oil. Many devotees are anointed as an act of consecration or blessing at every stage of life, with rituals accompanying birthing, educational enrollments, religious initiations, and death.[citation needed] New buildings, houses, and ritual instruments are anointed,[citation needed] and some idols are anointed daily. Particular care is taken in such rituals to the direction of the smearing. People are anointed from head to foot, downwards.[2] The water may derive from one of the holy rivers or be scented with saffron, turmeric, or flower infusions; the waste water produced when cleaning certain idols or when writing certain verses of scripture may also be used.[citation needed] Ointments may include ashes, clay, powdered sandalwood, or herbal pastes.

Buddhism

[edit]Buddhist practices of anointing are largely derived from Indian practices but tend to be less elaborate and more ritualized. Buddhists may sprinkle assembled practitioners with water or mark idols of Buddha or the Bodhisattvas with cow or yak butter. Flower-scented water is also used, as are ink-water and "saffron water" stained yellow using saffron or turmeric.[citation needed]

Judaism

[edit]

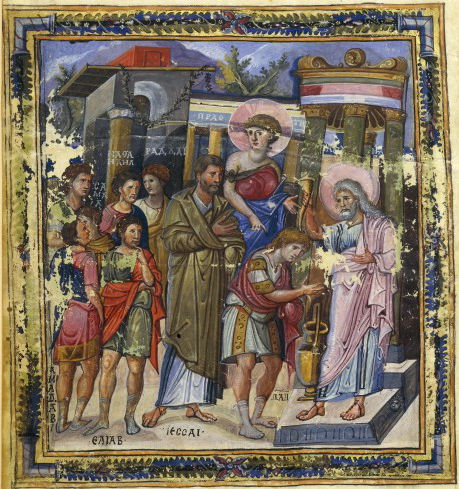

In antiquity, use of a holy anointing oil was significant in the Hebrews' consecration of priests,[26] the Kohen Gadol (High Priest),[27][28] and the sacred vessels.[29][11] Prophets[n 5] and the Israelite kings were anointed as well,[11] the kings from a horn.[33] Anointment by the chrism prepared according to the ceremony described in the Book of Exodus[34] was considered to impart the "Spirit of the Lord".[33] It was performed by Samuel in place of a coronation of both Saul[35] and David.[11] The practice was not always observed and seems to have been essential only at the consecration of a new line or dynasty.[1]

Because of its importance, the High Priest and the king were sometimes called "the Anointed One".[n 6][11] The term—מָשִׁיחַ, Mashiaẖ—gave rise to the prophesied figure of the Messiah (q.v.)[n 7] and a long history of claimants.

The expression "anoint the shield" which occurs in Isaiah[43] is a related or poetic usage, referring to the practice of rubbing oil on the leather of the shield to keep it supple and fit for war.[11] The practice of anointing a shield predates the anointing of other objects in that the "smearing" (Hebrew "mashiach") of the shield renewed the leather covering on a wooden shield. A victorious soldier was elevated on his shield by his comrades after a battle or upon his selection as a new king. The idea of protection and selection arose from this and was extended to the idea of a "chosen one" thus leading to the modern concept of a Messiah (Hebrew for the one who was anointed.)[citation needed]

Christianity

[edit]

Christianity developed from the association of Jesus of Nazareth with the Jewish prophecies of an "Anointed One".[n 8] His epithet "Christ" is a form of the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew title. He was not anointed by the High Priest in accordance with the ceremony described in Exodus, but he was considered to have been anointed by the Holy Spirit during his baptism.[n 9] A literal anointing of Jesus also occurs when he was lavishly oiled by Mary of Bethany.[50][51] Performed out of affection, the anointment is said by Jesus to have been preparation for his burial.

In the New Testament, John describes "anointing from the Holy One"[52] and "from Him abides in you".[53] Both this spiritual anointment[citation needed] and literal anointment with oil are usually associated with the Holy Spirit. Eastern Orthodox churches in particular attach great importance to the oil said to have been originally blessed by the Twelve Apostles.[citation needed]

The practice of "chrismation" (baptism with oil) appears to have developed in the early church during the later 2nd century as a symbol of Christ, rebirth, and inspiration.[54] The earliest surviving account of such an act seems to be the letter written "To Autolycus" by Theophilus, bishop of Antioch. In it, he calls the act "sweet and useful", punning on khristós (Ancient Greek: χριστóς, "anointed") and khrēstós (χρηστóς, "useful"). He seems to go on to say "wherefore we are called Christians on this account, because we are anointed with the oil of God",[55][n 10] and "what person on entering into this life or being an athlete is not anointed with oil?"[54] The practice is also defended by Hippolytus in his "Commentary on the Song of Songs"[56] and by Origen in his "Commentary on Romans". Origen opines that "all of us may be baptized in those visible waters and in a visible anointing, in accordance with the form handed down to the churches".[57]

Anointing was particularly important among the Gnostics. Many early apocryphal and Gnostic texts state that John the Baptist's baptism by water was incomplete and that anointment with oil is a necessary part of the baptismal process. The Gospel of Philip claims that

chrism is superior to baptism, for it is from the word "chrism" that we have been called "Christians", certainly not from the word "baptism". And it is from the "chrism" that the "Christ" has his name. For the Father anointed the Son, and the Son anointed the apostles, and the apostles anointed us. He who has been anointed possesses everything. He possesses the Resurrection, the Light, the Cross, the Holy Spirit. The Father gave him this in the bridal chamber; he merely accepted the gift. The Father was in the Son and the Son in the Father. This is the Kingdom of Heaven.

In the Acts of Thomas, the anointing is the beginning of the baptismal ritual and essential to becoming a Christian, as it says God knows his own children by his seal and that the seal is received through the oil. Many such chrismations are described in detail through the work.

In medieval and early modern Christianity, the oil from the lamps burnt before the altar of a church was felt to have particular sanctity. New churches and altars were anointed at their four corners during their dedication, as were tombs, gongs, and some other ritual instruments and utensils.[12]

Latin Catholicism

[edit]

The Roman Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran Churches bless three types of holy oils for anointing: "Oil of the Catechumens" (abbreviated OS, from the Latin oleum sanctum, meaning holy oil), "Oil of the Infirm" (OI), and "Sacred Chrism" (SC). The first two are said to be blessed, while the chrism is consecrated.

The Oil of Catechumens is used to people immediately before baptism, whether they are infants or adult catechumens. In the early church converts seeking baptism, known as "catechumens", underwent a period of formation known as catechumenate, and during that period of instruction received one or more anointings with the oil of cathecumens for the purpose of expelling evil spirits.[12] Before the 1968 revision of the rite of ordination the ordaining bishop anointed the hands of the new priest with the Oil of Catechumens,[59] The older form is now used only in ordaining members of associations, such as the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter, dedicated to the preservation of the pre-Vatican II liturgy. In the later form, priests,[60] like bishops,[61] are anointed with chrism, the hands of a priest, the head of a bishop. (In the older form, a bishop's hands, as well as the head, are anointed with chrism. The traditional Roman Pontifical also has a rite of coronation of kings and queens including anointing with the Oil of Catechumens. In some countries, as in France, the oil used in that rite was chrism.

Oil of the Infirm is used for administration of the sacrament of anointing of the sick, the ritual treatment of the sick and infirm through what was usually called Extreme Unction in Western Christianity from the late 12th to the late 20th century.[62]

Sacred Chrism is used in the sacraments of baptism, confirmation, and holy orders. It is also used in the dedication of new churches, new altars, and in the consecration of new patens and chalices for use in Mass. In the case of the sacrament of baptism, the subject receives two distinct unctions: one with the oil of catechumens, prior to being baptized, and then, after baptism with water is performed, the subject receives an unction with chrism. In the case of the sacrament of confirmation, anointing with chrism is the essential part of the rite.

Any bishop may consecrate the holy oils. They normally do so every Holy Thursday at a special "Chrism Mass". In the Gelasian sacramentary, the formula for doing so is:[12]

Send forth, O Lord, we beseech thee, thy Holy Spirit the Paraclete from heaven into this fatness of oil, which thou hast deigned to bring forth out of the green wood for the refreshing of mind and body; and through thy holy benediction may it be for all who anoint with it, taste it, touch it, a safeguard of mind and body, of soul and spirit, for the expulsion of all pains, of every infirmity, of every sickness of mind and body. For with the same thou hast anointed priests, kings, and prophets and martyrs with this thy chrism, perfected by thee, O Lord, blessed, abiding within our bowels in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Orthodoxy and Greek Catholicism

[edit]

In the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches, confirmation is known as chrismation. The Mystery of Chrismation is performed immediately after the Mystery of Baptism as part of a single ceremony. The ritual employs the sacred myron (μύρον, "chrism"), which is said to contain a remnant of oil blessed by the Twelve Apostles. In order to maintain the apostolic blessing unbroken, the container is never completely emptied[12] but it is refilled as needed, usually at a ceremony held on Holy Thursday at the Patriarchate of Constantinople[63] or the patriarchal cathedrals of the autocephalous churches.[64] At the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the process is under the care of the Archontes Myrepsoi, lay officials of the patriarchate. Various members of the clergy may also participate in the preparation, but the consecration itself is always performed by the patriarch or a bishop deputed by him for that purpose. The new myron contains olive oil, myrrh, and numerous spices and perfumes. This myron is normally kept on the Holy Table or on the Table of Oblation. During chrismation, the "newly illuminate" person is anointed by using the myron to make the sign of the cross on the forehead, eyes, nostrils, lips, both ears, breast, hands, and feet. The priest uses a special brush for this purpose. Prior to the 20th century, the myron was also used for the anointing of Orthodox monarchs.

The oil that is used to anoint the catechumens before baptism is simple olive oil which is blessed by the priest immediately before he pours it into the baptismal font. Then, using his fingers, he takes some of the blessed oil floating on the surface of the baptismal water and anoints the catechumen on the forehead, breast, shoulders, ears, hands, and feet. He then immediately baptizes the catechumen with threefold immersion in the name of the Trinity.

Anointing of the sick is called the "Sacred Mystery of Unction". The practice is used for spiritual ailments as well as physical ones, and the faithful may request unction any number of times at will. In some churches, it is normal for all of the faithful to receive unction during a service on Holy Wednesday of Holy Week. The holy oil used at unction is not stored in the church like the myron, but consecrated anew for each individual service. When an Orthodox Christian dies, if he has received the Mystery of Unction and some of the consecrated oil remains, it is poured over his body just before burial. It is also common to bless using oils which have been blessed either with a simple blessing by a priest (or even a venerated monastic), or by contact with some sacred object, such as relics of a saint, or which has been taken from an oil lamp burning in front of a wonderworking icon or some other shrine.[citation needed]

In the Armenian Church, crosses are traditionally not considered holy until they have been anointed and prayed over, thus introducing the Holy Spirit into them. The same ritual was formerly observed in the other Orthodox churches.[12]

Protestantism

[edit]Owing to their particular focus upon the action of the Holy Spirit, Pentecostal churches sometimes continue to employ anointing for consecration and ordination of pastors and elders, as well as for healing the sick.[citation needed]

The Pentecostal expression "the anointing breaks the yoke" derives from a passage in Isaiah[65] which discusses the power given the prophet Hezekiah by the Holy Spirit over the tyrant Sennacherib.[citation needed]

Latter-day Saints

[edit]Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints practice anointing with pure, consecrated olive oil[66] in two ways: 1) as a priesthood ordinance in preparation for the administration of a priesthood blessing, and 2) in conjunction with washing as part of the endowment.[67] The Doctrine and Covenants contains numerous references to anointing[68] and administration to the sick[69] by those with authority to perform the laying on of hands.[70] On 21 January 1836, Joseph Smith instituted anointing during the rites of sanctification and consecration preparatory to the rites practiced in the Kirtland Temple.[71] The anointing would prepare church members to receive the endowment of "power from on high" promised in an earlier 1831 revelation.[72] At the present time, any holder of the Melchizedek priesthood may anoint the head of an individual by the laying on of hands. Olive oil must be used if available, and it must have been consecrated earlier in a short ordinance that any holder of the Melchizedek priesthood may perform.[73]

Royalty

[edit]

In addition to its use for the Israelite kingship, anointing has been an important ritual in Christian rites of Coronation, especially in Europe. As reported by the jurisconsult Tancredus, initially only the kings of Jerusalem, France, England and Sicily were crowned and anointed:

Et sunt quidam coronando, et quidam non, tamen illi, qui coronatur, debent inungi: et tales habent privilegium ab antiquo, et de consuetudine. Alii modo non debent coronari, nec inungi sine istis: et si faciunt; ipsi abutuntur indebite. […] Rex Hierosolymorum coronatur et inungitur; Rex Francorum Christianissimus coronatur et inungitur; Rex Anglorum coronatur et inungitur; Rex Siciliae coronatur et inungitur.

And [the kings] are both crowned and not, among them, those who are crowned must be anointed: they have this privilege by ancient custom. The others, instead, must not be crowned or anointed: and if they do so unduly it is abuse.[74]

Later French legend held that a vial of oil, the Holy Ampulla, descended from Heaven to anoint Clovis I as the king of the Franks following his conversion to Christianity in 493. The Visigoth Wamba is the earliest Catholic king known to have been anointed,[75][76] although the practice apparently preceded him in Spain.[77][n 11] The ceremony, which closely followed the rite described by the Old Testament.,[79] was performed in 672 by Quiricus, the archbishop of Toledo;[77] It was apparently copied a year later when Flavius Paulus defected and joined the Septimanian rebels he had been tasked with quieting.[n 12][80] The rite epitomized the Catholic Church's sanctioning the monarch's rule; it was notably employed by usurpers such as Pepin, whose dynasty replaced the Merovingians in 751. While it might be argued that the practice subordinated the king to the church, in practice the sacral anointing of kings was seen as elevating the king to priestly or even saintly status.[81] Lupoi argues that this set in motion the conflicting claims that developed into the Investiture Crisis.[82] At the same time, royal unction recontextualized the elections and popular acclamations still legally responsible for the elevation of new rulers. They were no longer understood as autonomous authorities but merely agents in service of God's will.[81] The nature of anointment was alluded to in Shakespeare's Richard II:

Not all the water in the rough rude sea

Can wash the balm off an anointed king.[83]

Napoleon was reportedly anointed in the presence of the Pope at his coronation.[84]

In Eastern Orthodoxy, the anointing of a new king is considered a Sacred Mystery. The act is believed to empower him—through the grace of the Holy Spirit—with the ability to discharge his divinely appointed duties, particularly his ministry in defending the faith. The same myron used in Chrismation is used for the ceremony. In Russian Orthodox ceremonial, the anointing took place during the coronation of the tsar towards the end of the service, just before his receipt of Holy Communion. The sovereign and his consort were escorted to the Holy Doors (Iconostasis) of the cathedral and jointly anointed by the metropolitan. Afterwards, the tsar was taken alone through the Holy Doors—an action normally reserved only for priests—and received communion at a small table set next to the Holy Table.

In the present day, royal unction is less common, being practiced only upon the monarchs of Britain and of Tonga.[citation needed] The utensils for the practice are sometimes reckoned as regalia, like the ampulla and spoon used in the Kingdom of France and the anointing horns used in Sweden and Norway.[citation needed] The Biblical formula is not necessarily followed. For the 1626 coronation of King Charles I of England, the holy oil was made of a concoction of orange, jasmine, distilled roses, distilled cinnamon, and ben oil.

See also

[edit]- Coronation, the assumption of an office by wearing a crown

- Enthronement, the assumption of an office by sitting upon a throne

- Investiture, the assumption of an office by wearing an item of clothing

- Messiah, the "Anointed One" in the Abrahamic religions

Notes

[edit]- ^ Robert Manning's Handling Sin: . ..Þe prest þat ys a noynt...[5]

- ^ This occurs both in the Old[8] and New Testament.[9][10]

- ^ The Bible records the practice at the time of the New Testament.[13][14]

- ^ In the Old Testament, it is mentioned in the Second Book of Samuel[15] and the Book of Psalms[16] among other places.[11] In the New Testament, Chapter 7 of the Book of Luke records Jesus's being anointed while visiting the house of a Pharisee.[17]

- ^ See, e.g., the 1st Book of Kings,[30] the 1st Book of Chronicles,[31] and Psalm 105.[32]

- ^ As, e.g., in Leviticus[36][37][38] and Psalm 132.[39]

- ^ As, e.g., in Psalm 2[40] and the Book of Daniel.[41][42]

- ^ The claim is explicit in John[44] and the Book of Acts.[45][46][47][48]

- ^ A passage in Isaiah[49] is understood by Christians as saying that the Messiah will be baptized by the Holy Spirit rather than in a formal ceremony at the Temple.[11]

- ^ The passage is somewhat uncertain as the earliest surviving manuscript has "mercy" (ἔλεoς, éleos) instead of "oil" (ἔλαιoν, élaion), but a corrector has emended this to "oil" in agreement with the other two manuscripts.

- ^ See King for the argument in favor of dating the practice to the 631 coronation of Sisenand.[78]

- ^ The rebel general began his letter to his former liege "Flavius Paulus, anointed king in the east, [sends his greetings] to Wamba, king in the east" (Flavius Paulus unctus rex orientalis Wambani regi austro).[80]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f EB (1878).

- ^ a b c d e f EB (1911), p. 79.

- ^ James Strong, The New Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible (Nashville: T. Nelson, 1990) Heb. No. 4899 Gr. No. 5547.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "anoint, v." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1884.

- ^ Mannyng, Robert (1303), Handlyng Synne, l. 7417

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "† aˈnoint, adj." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1884.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "chrism, n." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1889.

- ^ Isaiah 1:6

- ^ Mark 6:13

- ^ James 5:14–15

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Easton (1897).

- ^ a b c d e f g h EB (1911), p. 80.

- ^ Mark 14:8

- ^ Luke 23:56

- ^ 2 Samuel 14:2

- ^ Psalms 104:15

- ^ Luke 7:38–46

- ^ Smith, William Robertson, Lectures on the Religion of the Semites

- ^ 1 W. Spiegelberg, "Die Symbolik des Salbens im A.gyptischen," Recueil de travaux relatifs... (RT) 28 (1906): 184-85

- ^ 10 H. Bonnet, Reallexikon der dgyptischen Reli gionsgeschichte (Berlin, 1952

- ^ " E. Cothenet, "Onction," in L. Pirot, A. Robert, H. Cazelles, eds., Dictionnaire de la Bible, Suppld ment, vol. 6 (Paris, 1960

- ^ 12 E. Kutsch, Salbung als Rechtsakt (Berlin, 1963), pp.

- ^ 13 E. Martin-Pardey, "Salbung," LA, vol. 5, cols. 367-69

- ^ Thompson, Stephen E. (1994). "he Anointing of Officials in Ancient Egypt". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 53 (1): 25. doi:10.1086/373652. JSTOR 545354. S2CID 162870303.

- ^ McCreesh, N.C. (2009). Ritual anointing: analyses of hair and coffin coatings in ancient Egypt. The University of Manchester Library (PhD). Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Exodus 29:7

- ^ Exodus 29:29

- ^ Leviticus 4:3

- ^ Exodus 30:26

- ^ 1 Kings 19:16

- ^ 1 Chronicles 16:22

- ^ Psalm 105:15

- ^ a b 1 Samuel 16:13

- ^ Exodus 30:22–25

- ^ 1 Sam 10:1

- ^ Leviticus 4:3–5

- ^ 4:16

- ^ 6:20

- ^ Psalm 132:10

- ^ Psalm 2:2

- ^ Daniel 7:13

- ^ Daniel 9:25–26

- ^ Isaiah 21:5

- ^ John 1:41

- ^ Acts 9:22

- ^ 17:2–3

- ^ 18:5

- ^ 18:28

- ^ Isaiah 61:1

- ^ John 12:1–12:11; also Matthew 26:6–26:13, Mark 14:1–14:11, and Luke 7:36–7:50.

- ^ Fleming, Daniel (1998). "The Biblical Tradition of Anointing Priests". Journal of Biblical Literature. 117 (3): 401–414. doi:10.2307/3266438. JSTOR 3266438.

- ^ 1 John 2:20

- ^ 1 John 2:27

- ^ a b Ferguson, Everett (2009). Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries. Kindle Locations 5142-5149: Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 269. ISBN 978-0802827487.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Theophilus of Antioch, "To Autolycus", 1.12.

- ^ Smith, Yancy (2013). The Mystery of Anointing. Gorgias. p. 30. ISBN 978-1463202187.

- ^ Origen, "Commentary on Romans", 5.8.3.

- ^ Vatican Library MS Reginensis 316.

- ^ "Rituale Romanum: Rite for ordination of priests". Archived from the original on 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ Ordination of Priests, 133

- ^ Rite of Ordination of a Bishop, 28

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article "unction"

- ^ Pavlos Menesoglou. "The Sanctification of the Holy Chrism". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Archived from the original on 2003-03-01. Retrieved 2008-03-09..

- ^ "The Consecration of Holy Christ". Orthodox Church in America. 5 April 2004. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- ^ Isaiah 10:27

- ^ "When did the use of consecrated olive oil in priesthood blessings originate?". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ "Prophetic Teachings on Temples: Washing and Anointing - Initiatory". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ "Anointing, Anoint". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ "Administration to the Sick". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ "Hands, Laying on of". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ "Anoint", The Joseph Smith Papers, archived from the original on September 10, 2013, retrieved 24 October 2012

- ^ "Endowment of Power". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ "Consecrating Oil". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ Tancredus, De Regibus Catholicorum et Christianorum 6:18 (https://books.google.com/books?id=CTVgAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA130)

- ^ Lupoi (2000), pp. 251 f.

- ^ Moorhead (2001), p. 173.

- ^ a b Darras (1866), p. 270.

- ^ King (1972), pp. 48–49.

- ^ Wolfram (1997), pp. 273–274.

- ^ a b Wolfram (1997), p. 273.

- ^ a b Lupoi (2000), p. 252.

- ^ Lupoi (2000), pp. 251 f..

- ^ Shakespeare, William. Richard II, II.ii.

- ^ Merieau, Eugenie (2019). "French authoritarian constitutionalism and its legacy". Elgar.

References

[edit]- , Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 3d ed., London: T. Nelson & Sons, 1897.

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 90

- Conybeare, Frederick Cornwallis (1911), , in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 79–80

- Darras, Joseph Éphiphane (1866), A General History of the Catholic Church: From the Commencement of the Christian Era until the Present Time, Vol. II, New York: P. O'Shea [Originally published in French; translated by Martin Spalding].

- King, Paul David (1972), Law & Society in the Visigothic Kingdom, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-03128-8.

- Lupoi, Maurizio (2000), The Origins of the European Legal Order, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [Originally published in Italian as Alle radici del mondo giuridico europeo by Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato in 1994; translated by Adrian Belton], ISBN 0-521-62107-0.

- Moorhead, John (2001), The Roman Empire Divided: 400–700, London: Pearson Education [Republished 2013 by Routledge], ISBN 9781317861447.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1997), The Roman Empire and its Germanic Peoples, University of California Press [Originally published in German as Das Reich und die Germanen by Wolf Jobst Siedler Verlag in 1990; translated by Thomas Dunlap], ISBN 9780520085114.

Further reading

[edit]- Spieckermann, Hermann (1999), "Anointing", The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Vol. I, Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, p. 66, ISBN 0802824137.