Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

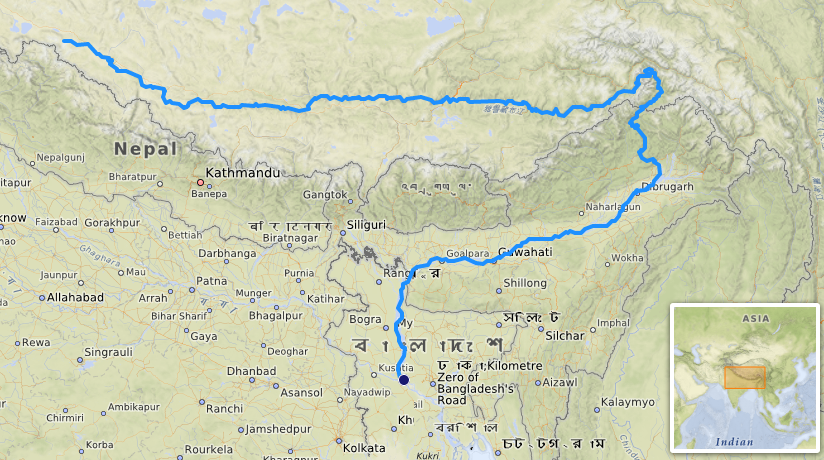

Brahmaputra River

View on Wikipedia

| Brahmaputra | |

|---|---|

| |

Path of the Brahmaputra River | |

| |

| Etymology | From Sanskrit ब्रह्मपुत्र (brahmaputra, "son of Brahma"), from ब्रह्मा (brahmā, "Brahma") + पुत्र (putra, "son"). |

| Location | |

| Countries | |

| Autonomous Region | Tibet |

| Cities | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Chemayungdung glacier, Manasarovar |

| • location | Himalayas |

| • coordinates | 30°19′N 82°08′E / 30.317°N 82.133°E |

| • elevation | 5,210 m (17,090 ft) |

| Mouth | Ganges |

• location | Ganges Delta |

• coordinates | 23°47′46.7376″N 89°45′45.774″E / 23.796316000°N 89.76271500°E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 2,880 km (1,790 mi)[1] 3,080 km (1,910 mi)[n 1] |

| Basin size | 625,726.9 km2 (241,594.5 sq mi)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Confluence of the Ganges |

| • average | (Period: 1971–2000)21,319.2 m3/s (752,880 cu ft/s)[3][4] Brahmaputra (Jamuna)–Old Brahmaputra–Upper Meghna → 26,941.1 m3/s (951,420 cu ft/s)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Bahadurabad |

| • average | (Period: 1980–2012)24,027 m3/s (848,500 cu ft/s)[5] (Period: 2000–2015)21,993 m3/s (776,700 cu ft/s)[1] |

| • minimum | 3,280 m3/s (116,000 cu ft/s)[1] |

| • maximum | 102,585 m3/s (3,622,800 cu ft/s)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Guwahati |

| • average | (Period: 1971–2000)18,850.4 m3/s (665,700 cu ft/s)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Dibrugarh |

| • average | (Period: 1971–2000)8,722.3 m3/s (308,030 cu ft/s)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Pasighat |

| • average | (Period: 1971–2000)5,016.3 m3/s (177,150 cu ft/s)[3] |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Padma → Meghna → Bay of Bengal |

| River system | Ganges River |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Lhasa, Nyang, Parlung Zangbo, Lohit, Nao Dihing, Buri Dihing, Dangori, Disang, Dikhow, Jhanji, Dhansiri, Kolong, Kopili, Bhorolu, Kulsi, Krishnai, Upper Meghna |

| • right | Kameng, Jia Bhoroli, Manas, Beki, Raidak, Jaldhaka, Teesta, Subansiri, Jia dhol, Simen, Pagladia, Sonkosh, Gadadhar |

The Brahmaputra is a trans-boundary river which flows through Southwestern China, Northeastern India, and Bangladesh. It is known as the Brahmaputra or Luit in Assamese, Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibetan, the Siang/Dihang River in Arunachali, and Jamuna River in East Bengal. By itself, it is the 9th largest river in the world by discharge, and the 15th longest.

It originates in the Manasarovar Lake region, near Mount Kailash, on the northern side of the Himalayas in Burang County of Tibet where it is known as the Yarlung Tsangpo River.[2] The Brahmaputra flows along southern Tibet to break through the Himalayas in great gorges (including the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon) and into Arunachal Pradesh.[6] It enters India near the village of Gelling in Arunachal Pradesh and flows southwest through the Assam Valley as the Brahmaputra and south through Bangladesh as the Jamuna (not to be confused with the Yamuna of India). In the vast Ganges Delta, it merges with the Ganges, popularly known as the Padma in Bangladesh, and becomes the Meghna and ultimately empties into the Bay of Bengal.[7]

At 3,000 km (1,900 mi) long, the Brahmaputra is an important river for irrigation and transportation in the region.[1][2] The average depth of the river is 30 m (100 ft) and its maximum depth is 135 m (440 ft) (at Sadiya).[8] The river is prone to catastrophic flooding in the spring when the Himalayan snow melts. The average discharge of the Brahmaputra is about ~22,000 m3/s (780,000 cu ft/s),[1][6] and floods reach about 103,000 m3/s (3,600,000 cu ft/s).[1][9] It is a classic example of a braided river and is highly susceptible to channel migration and avulsion.[10] It is also one of the few rivers in the world that exhibits a tidal bore. It is navigable for most of its length.

The Brahmaputra drains the Himalayas east of the Indo-Nepal border, south-central portion of the Tibetan plateau above the Ganga basin, south-eastern portion of Tibet, the Patkai hills, the northern slopes of the Meghalaya hills, the Assam plains, and northern Bangladesh. The basin, especially south of Tibet, is characterized by high levels of rainfall. Kangchenjunga (8,586 m) is the highest point within the Brahmaputra basin and the only peak above 8,000 m.

The Brahmaputra's upper course was long unknown, and its identity with the Yarlung Tsangpo was only established by exploration in 1884–1886. The river is often called the Tsangpo-Brahmaputra river.[citation needed]

The lower reaches are sacred to Hindus. While most rivers on the Indian subcontinent have female names, this river has a rare male name. Brahmaputra means "son of Brahma" in Sanskrit.[11]

Names

[edit]It is known by various names in different regional languages: Brôhmôputrô in Assamese; Tibetan: ཡར་ཀླུངས་གཙང་པོ་, Wylie: yar klung gtsang po Yarlung Tsangpo; simplified Chinese: 雅鲁藏布江; traditional Chinese: 雅魯藏布江; pinyin: Yǎlǔzàngbù Jiāng. It is also called Tsangpo-Brahmaputra and red river of India (when referring to the whole river including the stretch within the Tibet Autonomous Region).[12] In its Tibetan and Indian names, the river is unusually masculine in gender.[13]

Geography

[edit]Course

[edit]Tibet

[edit]

The upper reaches of the Brahmaputra River, known as the Yarlung Tsangpo from the Tibetan language, originates on the Angsi Glacier, near Mount Kailash, located on the northern side of the Himalayas in Burang County of Tibet. The source of the river was earlier thought to be on the Chemayungdung glacier, which covers the slopes of the Himalayas about 60 mi (97 km) southeast of Lake Manasarovar in southwestern Tibet.

From its source, the river runs for nearly 1,100 km (680 mi) in a generally easterly direction between the main range of the Himalayas to the south and the Kailas Range to the north.

In Tibet, the Tsangpo receives a number of tributaries. The most important left-bank tributaries are the Raka Zangbo (Raka Tsangpo), which joins the river west of Xigazê (Shigatse), and the Lhasa (Kyi), which flows past the Tibetan capital of Lhasa and joins the Tsangpo at Qüxü. The Nyang River joins the Tsangpo from the north at Zela (Tsela Dzong). On the right bank, a second river called the Nyang Qu (Nyang Chu) meets the Tsangpo at Xigazê.

After passing Pi (Pe) in Tibet, the river turns suddenly to the north and northeast and cuts a course through a succession of great narrow gorges between the mountainous massifs of Gyala Peri and Namcha Barwa in a series of rapids and cascades. Thereafter, the river turns south and southwest and flows through a deep gorge (the "Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon") across the eastern extremity of the Himalayas with canyon walls that extend upward for 5,000 m (16,000 ft) and more on each side. During that stretch, the river crosses the China-India line of actual control to enter northern Arunachal Pradesh, where it is known as the Dihang (or Siang) River, and turns more southerly.

Arunachal Pradesh

[edit]

The Yarlung Tsangpo leaves the part of Tibet to enter Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, where the river is called Siang. It makes a very rapid descent from its original height in Tibet and finally appears in the plains, where it is called Dihang. It flows for about 35 km (22 mi) southward after which, it is joined by the Dibang River and the Lohit River at the head of the Assam Valley. Below the Lohit, the river is called Brahmaputra and Doima (mother of water) and Burlung-Buthur by native Bodo tribals, it then enters the state of Assam, and becomes very wide—as wide as 20 km (12 mi) in parts of Assam.

The reason for such an unusual course and drastic change is that the river is antecedent to the Himalayas, meaning that it had existed before them and has entrenched itself since they started rising.

Assam

[edit]

The Dihang, winding out of the mountains, turns towards the southeast and descends into a low-lying basin as it enters northeastern Assam state. Just west of the town of Sadiya, the river again turns to the southwest and is joined by two mountain streams, the Lohit, and the Dibang. Below that confluence, about 1,450 km (900 mi) from the Bay of Bengal, the river becomes known conventionally as the Brahmaputra ("Son of Brahma"). In Assam, the river is mighty, even in the dry season, and during the rains, its banks are more than 8 km (5.0 mi) apart. As the river follows its braided 700 km (430 mi) course through the valley, it receives several rapidly flowing Himalayan streams, including the Subansiri, Kameng, Bhareli, Dhansiri, Manas, Champamati, Saralbhanga, and Sankosh Rivers. The main tributaries from the hills and from the plateau to the south are the Burhi Dihing, the Disang, the Dikhu, and the Kopili.

Between Dibrugarh and Lakhimpur Districts, the river divides into two channels—the northern Kherkutia channel and the southern Brahmaputra channel. The two channels join again about 100 km (62 mi) downstream, forming the Majuli island, which is the largest river island in the world.[14] At Guwahati, near the ancient pilgrimage centre of Hajo, the Brahmaputra cuts through the rocks of the Shillong Plateau, and is at its narrowest at 1 km (1,100 yd) bank-to-bank. The terrain of this area made it logistically ideal for the Battle of Saraighat, the military confrontation between the Mughal Empire and the Ahom Kingdom in March 1671. The first combined railroad/roadway bridge across the Brahmaputra was constructed at Saraighat. It was opened to traffic in April 1962.

The environment of the Brahmaputra floodplains in Assam have been described as the Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests ecoregion.

Bangladesh

[edit]

In Bangladesh, the Brahmaputra is joined by the Teesta River (or Tista), one of its largest tributaries. Below the Tista, the Brahmaputra splits into two distributary branches. The western branch, which contains the majority of the river's flow, continues due south as the Jamuna (Jomuna) to merge with the lower Ganga, called the Padma River (Pôdma). The eastern branch, formerly the larger, but now much smaller, is called the lower or Old Brahmaputra (Brommoputro). It curves southeast to join the Meghna River near Dhaka. The Padma and Meghna converge near Chandpur and flow out into the Bay of Bengal. This final part of the river is called Meghna.[15]

The Brahmaputra enters the plains of Bangladesh after turning south around the Garo Hills below Dhuburi, India. After flowing past Chilmari, Bangladesh, it is joined on its right bank by the Tista River and then follows a 240 km (150 mi) course due south as the Jamuna River. (South of Gaibanda, the Old Brahmaputra leaves the left bank of the mainstream and flows past Jamalpur and Mymensingh to join the Meghna River at Bhairab Bazar.) Before its confluence with the Ganga, the Jamuna receives the combined waters of the Baral, Atrai, and Hurasagar Rivers on its right bank and becomes the point of departure of the large Dhaleswari River on its left bank. A tributary of the Dhaleswari, the Buriganga ("Old Ganga"), flows past Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, and joins the Meghna River above Munshiganj.[15]

The Jamuna joins with the Ganga north of Goalundo Ghat, below which, as the Padma, their combined waters flow to the southeast for a distance of about 120 km (75 mi). After several smaller channels branch off to feed the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta to the south, the main body of the Padma reaches its confluence with the Meghna River near Chandpur and then enters the Bay of Bengal through the Meghna estuary and lesser channels flowing through the delta. The growth of the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta is dominated by tidal processes.[15]

The Ganga Delta, fed by the waters of numerous rivers, including the Ganga and Brahmaputra, is 105,000 km2 (41,000 sq mi), one of the largest river deltas in the world.[16]

Hydrology

[edit]The Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna system has the second-greatest average discharge of the world's rivers—roughly ~44,000 m3/s (1,600,000 cu ft/s), and the river Brahmaputra alone supplies about 50% of the total discharge.[17][1] The rivers' combined suspended sediment load of about 1.87 billion tonnes (1.84 billion tons) per year is the world's highest.[6][18]

In the past, the lower course of the Brahmaputra was different and passed through the Jamalpur and Mymensingh districts. In an 8.8 magnitude earthquake on 2 April 1762, however, the main channel of the Brahmaputra at Bhahadurabad point was switched southwards and opened as Jamuna due to the result of tectonic uplift of the Madhupur tract.[19]

Climate

[edit]Rising temperatures significantly contribute to snow melting in the upper Brahmaputra catchment.[20] The discharge of the Brahmaputra River is significantly influenced by the melting of snow in the upper part of its catchment area. This increase in river flow, caused by the substantial retreat of snow, leads to a higher downstream discharge. Such a rise in discharge often results in severe catastrophic issues, including flooding and erosion.

Discharge

[edit]

The Brahmaputra River is characterized by its significant rates of sediment discharge, the large and variable flows, along with its rapid channel aggradations and accelerated rates of basin denudation. Over time, the deepening of the Bengal Basin caused by erosion will result in the increase in hydraulic radius, and hence allowing for the huge accumulation of sediments fed from the Himalayan erosion by efficient sediment transportation. The thickness of the sediment accumulated above the Precambrian basement has increased over the years from a few hundred meters to over 18 km (11 mi) in the Bengal fore-deep to the south. The ongoing subsidence of the Bengal Basin and the high rate of Himalayan uplift continues to contribute to the large water and sediment discharges of fine sand and silt, with 1% clay, in the Brahmaputra River.

Climatic change plays a crucial role in affecting the basin hydrology. Throughout the year, there is a significant rise in hydrograph, with a broad peak between July and September. The Brahmaputra River experiences two high-water seasons, one in early summer caused by snowmelt in the mountains, and one in late summer caused by runoff from monsoon rains. The river flow is strongly influenced by snow and ice melting of the glaciers, which are located mainly on the eastern Himalaya regions in the upstream parts of the basin. The snow and glacier melt contribution to the total annual runoff is about 27%, while the annual rainfall contributes to about 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in) and 22,000 m3/s (780,000 cu ft/s) of discharge.[1] The highest recorded daily discharge in the Brahmaputra at Pandu was 72,726 m3/s (2,568,300 cu ft/s) August 1962 while the lowest was 1,757 m3/s (62,000 cu ft/s) in February 1968. The increased rates of snow and glacial melt are likely to increase summer flows in some river systems for a few decades, followed by a reduction in flow as the glaciers disappear and snowfall diminishes. This is particularly true for the dry season when water availability is crucial for the irrigation systems.

Floodplain evolution

[edit]The course of the Brahmaputra River has changed drastically in the past two and a half centuries, moving its river course westwards for a distance of about 80 km (50 mi), leaving its old river course, appropriately named the old Brahmaputra river, behind. In the past, the floodplain of the old river course had soils which were more properly formed compared to graded sediments on the operating Jamuna river. This change of river course resulted in modifications to the soil-forming process, which include acidification, the breakdown of clays and buildup of organic matter, with the soils showing an increasing amount of biotic homogenization, mottling, the coating around Peds and maturing soil arrangement, shape and pattern. In the future, the consequences of local ground subsidence coupled with flood prevention propositions, for instance, localised breakwaters, that increase flood-plain water depths outside the water breakers, may alter the water levels of the floodplains. Throughout the years, bars, scroll bars, and sand dunes are formed at the edge of the flood plain by deposition. The height difference of the channel topography is often not more than 1–2 m (3–7 ft). Furthermore, flooding over the history of the river has caused the formation of river levees due to deposition from the overbank flow. The height difference between the levee top and the surrounding floodplains is typically 1 m (3 ft) along small channels and 2–3 m (7–10 ft) along major channels. Crevasse splay, a sedimentary fluvial deposit which forms when a stream breaks its natural or artificial levees and deposits sediment on a floodplain, are often formed due to a breach in the levee, forming a lobe of sediments which progrades onto the adjacent floodplain. Lastly, flood basins are often formed between the levees of adjacent rivers.

Flooding

[edit]

During the monsoon season (June–October), floods are a very common occurrence. Deforestation in the Brahmaputra watershed has resulted in increased siltation levels, flash floods, and soil erosion in critical downstream habitat, such as the Kaziranga National Park in middle Assam. Occasionally, massive flooding causes huge losses to crops, life, and property. Periodic flooding is a natural phenomenon which is ecologically important because it helps maintain the lowland grasslands and associated wildlife. Periodic floods also deposit fresh alluvium, replenishing the fertile soil of the Brahmaputra River Valley. Thus flooding, agriculture, and agricultural practices are closely connected.[21][22][23]

The effects of flooding can be devastating and cause significant damage to crops and houses, serious bank erosive with consequent loss of homesteads, school and land, and loss of many lives, livestock, and fisheries. During the 1998 flood, over 70% of the land area of Bangladesh was inundated, affecting 31 million people and 1 million homesteads. In the 1998 flood which had an unusually long duration from July to September, claimed 918 human lives and was responsible for damaging 1,600 km (990 mi) of roads and 6,000 km (3,700 mi) embankments, and affecting 6,000 km2 (2,300 sq mi) of standing crops. The 2004 floods, over 25% of the population of Bangladesh or 36 million people, were affected by the floods; 800 people died; 952 000 houses were destroyed and 1.4 million were badly damaged; 24 000 educational institutions were affected including the destruction of 1200 primary schools, 2 million governments and private tube wells were affected, over 3 million latrines were damaged or washed away, this increases the risks of waterborne diseases including diarrhea and cholera. Also, 1.1 million ha (2.7 million acres) of the rice crop was submerged and lost before it could be harvested, with 7% of the yearly aus (early season) rice crop lost; 270,000 ha (670,000 acres) of grazing land was affected, 5600 livestock perished together with 254 00 poultry and 63 million tonnes (69 million short tons) of lost fish production.

Flood-control measures are taken by the water resource department and the Brahmaputra Board, but until now the flood problem remains unsolved. At least a third of the land of Majuli Island has been eroded by the river. Recently, it is suggested that a highway protected by concrete mat along the river bank and excavation of the river bed can curb this menace. This project, named the Brahmaputra River Restoration Project, is yet to be implemented by the government. Recently the Central Government approved the construction of Brahmaputra Express Highways.

Channel morphology

[edit]The course of the Brahmaputra River has changed dramatically over the past 250 years, with evidence of large-scale avulsion, in the period 1776–1850, of 80 km (50 mi) from east of the Madhupur tract to the west of it. Prior to 1843, the Brahmaputra flowed within the channel now termed the "Old Brahmaputra". The banks of the river are mostly weakly cohesive sand and silts, which usually erodes through large scale slab failure, where previously deposited materials undergo scour and bank erosion during flood periods. Presently, the river's erosion rate has decreased to 30 m (98 ft) per year as compared to 150 m (490 ft) per year from 1973 to 1992. This erosion has, however, destroyed so much land that it has caused 0.7 million people to become homeless due to loss of land.

Several studies have discussed the reasons for the avulsion of the river into its present course, and have suggested a number of reasons including tectonic activity, switches in the upstream course of the Teesta River, the influence of increased discharge, catastrophic floods and river capture into an old river course. From an analysis of maps of the river between 1776 and 1843, it was concluded in a study that the river avulsion was more likely gradual than catastrophic and sudden, and may have been generated by bank erosion, perhaps around a large mid-channel bar, causing a diversion of the channel into the existing floodplain channel.

The Brahmaputra channel is governed by the peak and low flow periods during which its bed undergoes tremendous modification. The Brahmaputra's bank line migration is inconsistent with time. The Brahmaputra river bed has widened significantly since 1916 and appears to be shifting more towards the south than towards the north. Together with the contemporary slow migration of the river, the left bank is being eroded away faster than the right bank.[24]

River engineering

[edit]The Brahmaputra River experiences high levels of bank erosion (usually via slab failure) and channel migration caused by its strong current, lack of riverbank vegetation, and loose sand and silt which compose its banks. It is thus difficult to build permanent structures on the river, and protective structures designed to limit the river's erosional effects often face numerous issues during and after construction. In fact, a 2004 report[25] by the Bangladesh Disaster and Emergency Sub-Group (BDER) has stated that several of such protective systems have 'just failed'. However, some progress has been made in the form of construction works which stabilize sections of the river, albeit with the need for heavy maintenance. The Bangabandhu Bridge, the only bridge to span the river's major distributary, the Jamuna, was thus opened in June 1998. Constructed at a narrow braid belt of the river, it is 4.8 km (3.0 mi) long with a platform 18.5 m (61 ft) wide, and it is used to carry railroad traffic as well as gas, power and telecommunication lines. Due to the variable nature of the river, the prediction of the river's future course is crucial in planning upstream engineering to prevent flooding on the bridge.

China built the Zangmu Dam in the upper course of the Brahmaputra River in the Tibet region and it was operationalised on 13 October 2015.[26]

Tributaries

[edit]The main tributaries from the mouth:[3]

| Left

tributary |

Right

tributary |

Length

(km) |

Basin size

(km2) |

Average discharge

(m3/s)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Brahmaputra | ||||

| Upper Meghna–Kalni–Kushyiara–Barak | 1,040 | 85,385 | 5,603.2 | |

| Shaldha | 555.3 | 28 | ||

| Beltoly | 232.7 | 11.6 | ||

| Jamuna | ||||

| Atrai–Gumani | 390 | 22,876.1 | 800.9 | |

| Ghaghat–Alay | 148 | 1,388.6 | 46.6 | |

| Jinjiram | 2,798.5 | 103 | ||

| Teesta | 414 | 12,466.1 | 463.2 | |

| Dharla–Jaldhaka | 289 | 5,929.4 | 245.1 | |

| Torsa | 12,183 | 361.7 | ||

| Middle Brahmaputra | ||||

| Gangadhar

(Sunkosh) |

11,413.9 | 231.5 | ||

| Tipkai–Gaurang | 108 | 3,202.9 | 118.7 | |

| Champabuti (Bhur) | 135 | 1,259.3 | 43.1 | |

| Krishnai | 105 | 2,251.5 | 82.3 | |

| Manas–Beki | 400 | 36,835.1 | 875 | |

| Kulsi | 220 | 4,615.2 | 339.7 | |

| Puthimari | 190 | 2,737.4 | 149.7 | |

| Kalbog Nadi | 283.7 | 23.4 | ||

| Kopili (Kalang) | 297 | 19,705.7 | 1,802 | |

| Pokoriya (Kolong) | 1,265.5 | 103.3 | ||

| Bhola | 726.2 | 69.2 | ||

| Tangni | 500.9 | 40.4 | ||

| Dhansiri Nadi | 123 | 1,821.8 | 122.2 | |

| Leteri | 305.7 | 24.4 | ||

| Belsiri Nadi | 808.7 | 67.1 | ||

| Gabhara Nadi | 697.7 | 57.8 | ||

| Kameng

(Bhareli) |

264 | 10,841.3 | 780.8 | |

| Gamiripal | 262.4 | 22.2 | ||

| Diphlu | 1,050.3 | 91.3 | ||

| Bargang | 42 | 640.5 | 57.5 | |

| Bihmāri Nadi | 208.4 | 18.6 | ||

| Baroi | 64 | 712.7 | 68.5 | |

| Holongi | 167 | 970.9 | 92.2 | |

| Dhansiri | 352 | 12,780.1 | 978.9 | |

| Subansiri | 518 | 34,833.1 | 3,153.4 | |

| Tuni | 186.3 | 20.2 | ||

| Jhānzi | 108 | 2,102.2 | 213.3 | |

| Dikhu | 200 | 3,268.7 | 359 | |

| Disang | 253 | 4,415.1 | 477.8 | |

| Burhi Dihing | 380 | 5,975.2 | 652.8 | |

| Simen | 68.5 | 1,438 | 232.1 | |

| Poba | 599.1 | 89.4 | ||

| Lohit | 560 | 29,330.1 | 2,138.2 | |

| Dibang | 324 | 12,502.5 | 1,337.2 | |

| Siang | ||||

| Mora Lāli Korong | 201.2 | 30.1 | ||

| Siku | 254.8 | 40.7 | ||

| Yamne | 1,266.3 | 205.6 | ||

| Sireng | 11 | |||

| Yembung | 171 | 30 | ||

| Sike

(Siyom) |

170 | 5,818.3 | 843.4 | |

| Simyuk (Simaang) | 12.1 | |||

| Siring | 143.2 | 21.3 | ||

| Angong | 141.4 | 19.9 | ||

| Niogang (Sirapatang) | 151.2 | 21.5 | ||

| Shapateng | 1,044.5 | 88.9 | ||

| Siyi (Pall Si) | 154.8 | 14.6 | ||

| Ringong (Ripong Asi) | 785.6 | 53.3 | ||

| Yang Sang Chu | 1,302.1 | 156 | ||

| Yarlung Tsangpo | ||||

| Nagöng (Lugong) | 314.6 | 17.4 | ||

| Nilechu | 134.2 | 10 | ||

| Baimu Xiri | 695.2 | 33.9 | ||

| Sikong | 273.6 | 18.8 | ||

| Simo Chu | 636.7 | 37.6 | ||

| Chimdro Chu | 2,161.3 | 99.2 | ||

| Yanglang | 451.1 | 20.5 | ||

| Parlung Zangbo | 266 | 28,631 | 867.6 | |

| Nyang | 307.5 | 17,928.7 | 441.9 | |

| Nanyi | 633.3 | 42.2 | ||

| Ga Sacouren | 1,119.9 | 32.7 | ||

| Lilong | 1,562.9 | 89.6 | ||

| Mulucuo | 1,150.1 | 23.7 | ||

| Jindong Qu | 958.1 | 26.7 | ||

| Baqu Qu | 1,624.6 | 23 | ||

| Zengqiqu | 1,453.5 | 12 | ||

| Momequ | 2,029.7 | 23.1 | ||

| Yalong | 68 | 2,263.9 | 26 | |

| Lhasa | 568 | 32,471 | 335 | |

| Nima Maqu | 83 | 2,385.9 | 11.9 | |

| Menqu | 73 | 11,437.1 | 102.1 | |

| Wuyu Maqu | 1,609.8 | 3.4 | ||

| Xiangqu Qu | 7,427.6 | 21.2 | ||

| Nyang Qu (Nianchu) | 217 | 14,231.9 | 77.6 | |

| Nadong | 2,422.5 | 8.4 | ||

| Xiabu | 5,467.2 | 20.5 | ||

| Dogxung Zangbo | 303 | 19,885.7 | 58.2 | |

| Sa'gya Zangbo | 1,489.2 | 6.8 | ||

| Ji | 1,647.3 | 5.4 | ||

| Naxiong | 5,771.9 | 74.5 | ||

| Mang Zhaxiongqu | 524.1 | 14.8 | ||

| Galixiong | 411.1 | 12.3 | ||

| Xuede Zangbu | 807 | 25.5 | ||

| Jiajizi | 1,391 | 24.8 | ||

| Menqu Qu | 1,236.9 | 7.1 | ||

| Chai (Tsa Chu) | 4,319.6 | 9.7 | ||

| Maquan

(Matsang Tsangpo) |

270 | 21,502.3 | 164 | |

*Period: 1971–2000

History

[edit]

Earlier history

[edit]The Kachari group called the river "Dilao", "Tilao".[27] Early Greek accounts of Curtius and Strabo give its name as Dyardanes (Ancient greek Δυαρδάνης) and Oidanes.[28] In the past, the course of the lower Brahmaputra was different and passed through the Jamalpur and Mymensingh districts. Some water still flows through that course, now called the Old Brahmaputra, as a distributary of the main channel.

A question about the river system in Bangladesh is when and why the Brahmaputra changed its main course, at the site of the Jamuna and the "Old Brahmaputra" fork that can be seen by comparing modern maps to historic maps before the 1800s.[29] The Brahmaputra likely flowed directly south along its present main channel for much of the time since the last glacial maximum, switching back and forth between the two courses several times throughout the Holocene.

One idea about the most recent avulsion is that the change in the course of the main waters of the Brahmaputra took place suddenly in 1787, the year of the heavy flooding of the river Tista.

In the middle of the 18th century, at least three fair-sized streams flowed between the Rajshahi and Dhaka Divisions, viz., the Daokoba, a branch of the Tista, the Monash or Konai, and the Salangi. The Lahajang and the Elengjany were also important rivers. In Renault's time, the Brahmaputra as a first step towards securing a more direct course to the sea by leaving the Mahdupur Jungle to the east began to send a considerable volume of water down the Jinai or Jabuna from Jamalpur into the Monash and Salangi. These rivers gradually coalesced and kept shifting to the west till they met the Daokoba, which was showing an equally rapid tendency to cut towards the east. The junction of these rivers gave the Brahmaputra a course worthy of her immense power, and the rivers to right and left silted up. In Renault's Altas they very much resemble the rivers of Jessore, which dried up after the hundred-mouthed Ganga had cut her new channel to join the Meghna at the south of the Munshiganj subdivision.

In 1809, Francis Buchanan-Hamilton wrote that the new channel between Bhawanipur and Dewanranj "was scarcely inferior to the mighty river, and threatens to sweep away the intermediate country". By 1830, the old channel had been reduced to its present insignificance. It was navigable by country boats throughout the year and by launches only during rains, but at the point as low as Jamalpur it was formidable throughout the cold weather. Similar was the position for two or three months just below Mymensingh also.

International cooperation

[edit]The waters of the River Brahmaputra are shared by Tibet, India, and Bangladesh. In the 1990s and 2000s, there was repeated speculation that mentioned Chinese plans to build a dam at the Great Bend, with a view to diverting the waters to the north of the country. This has been denied by the Chinese government for many years.[30] At the Kathmandu Workshop of Strategic Foresight Group in August 2009 on Water Security in the Himalayan Region, which brought together in a rare development leading hydrologists from the basin countries, the Chinese scientists argued that it was not feasible for China to undertake such a diversion.[31] However, on 22 April 2010, China confirmed that it was indeed building the Zangmu Dam on the Brahmaputra in Tibet,[30] but assured India that the project would not have any significant effect on the downstream flow to India.[32] This claim has also been reiterated by the Government of India, in an attempt to assuage domestic criticism of Chinese dam construction on the river, but is one that remains hotly debated.[33] Recent years have seen an intensification of grassroots opposition, especially in the state of Assam, against Chinese upstream dam building, as well as growing criticism of the Indian government for its perceived failure to respond appropriately to Chinese hydropower plans.[34]

In a meeting of scientists at Dhaka at 2010, 25 leading experts from the basin countries issued a Dhaka Declaration on Water Security[35] calling for the exchange of information in low-flow periods, and other means of collaboration. Even though the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention does not prevent any of the basin countries from building a dam upstream, customary law offers some relief to the lower riparian countries. There is also the potential for China, India, and Bangladesh to cooperate on transboundary water navigation.

Significance to people

[edit]

The lives of many millions of Indian and Bangladeshi citizens are reliant on the Brahmaputra River. Its delta is home to 130 million people and 600 000 people live on the riverine islands. These people rely on the annual 'normal' flood to bring moisture and fresh sediments to the floodplain soils, hence providing the necessities for agricultural and marine farming. In fact, two of the three seasonal rice varieties (aus and aman) cannot survive without the floodwater. Furthermore, the fish caught both on the floodplain during flood season and from the many floodplain ponds are the main source of protein for many rural populations.

Dams and hydropower projects

[edit]Brahmaputra and Ganges floodwaters can be supplied to most lands in India by constructing a coastal reservoir to store water on the Bay of Bengal sea area.[36]

Bridges

[edit]

India

[edit]

Current bridges

[edit]

From east to west till Parashuram Kund, then from southwest to northeast from Parshuram Kund to Patum, finally from east to southwest from Parshuram Kund to Burhidhing:

- Naranarayan Setu, road and rail bridge near Bongaigaon in Assam, 2,285 metres (7,497 ft)

- Old Saraighat Bridge, road and rail bridge near Guwahati in Assam. 1,495 metres (4,905 ft)

- New Saraighat Bridge, road bridge near Guwahati in Assam. 1,521 metres (4,990 ft)

- Kolia Bhomora Setu, road bridge near Tezpur in Assam, 3,025 metres (9,925 ft)

- Bogibeel Bridge, road and rail bridge near Dibrugarh in Assam, 4,940 metres (16,210 ft), The Longest on Brahmaputra River.

- Ranaghat Bridge on the Brahmaputra at Pasighat in Arunachal Pradesh. 3,375 metres (11,073 ft)

Approved and under-construction bridges

[edit]

9 new bridges, including 3 bridges in Guwahati (New Saraighat bridge parallel to the old bridge, and 2 new bridges in greenfield locations at Bharalumukh and Kurua), 1 new bridge in Tezpur parallel to the old bridge, and 5 greenfield bridges in new locations (Dhubri, Bijoynagar, Gohpur tunnel, Nemtighat, & Sivasagar) elsewhere in Assam have been approved. 5 of these were announced in 2017 by India's Minister for MoRTH, Nitin Gadkari.[37][38][39]

From west to east:

- Dhubri: Dhubri-Phulbari bridge, road and rail bridge in Assam, near tri-junction of east Meghalaya, west Assam and north Bangladesh[38][39] 12,625 metres (41,421 ft)

- Bijoynagar: Palasbari-Sualkuchi bridge, to connect Nalbari to Bijoynagar, Guwahati Airport & Shillong.[40]

- Guwahati: New Saraighat Bridge is rail-cum-road bridge parallel to old bridge, will be completed by December 2023.[41]

- Guwahati: Kumar Bhaskar Varma Setu, 4,050 metres (13,290 ft) in central Guwahati connecting North Guwahati with Guwahati (Pan Bazar and Bharalmukh).[40]

- Guwahati: Narangi-Kurua bridge, 675 metres (2,215 ft) east of Guwahati was approved in 2022.[42]

- Tezpur: Bhomoraguri-Tezpur Bridge (few meters parallel to existing Kalia Bhomara Bridge at Bhomoraguri suburb of Tezpur town in Assam,[39] 3,250 metres (10,660 ft) was partially complete in 2021.

- Numaligarh-Gohpur Tunnel: under-water tunnel between Gohpur (Biswanath district) and Numaligarh (Golaghat district) in Assam[38][39] 4,500 metres (14,800 ft) tunnel with 33.7 total length including ramp, Rs6,000 cr DPR was ready in September 2025 and construction will take 5 years after the land acquisition and award of contract.[43]

- Jorhat-Majuli bridge:

Jorhat-Majuli bridge at Jorhat on Brahmaputra in Assam The Jorhat-Majuli bridege combined with Louit Khablu Bridge on a tributary will connect Jorhat with Bihpuria and Narayanpur. When completed, it will be about 8.25 km in length.[38][39] - Sivasagar: Disangmukh-Tekeliphuta Bridge between Disangmukh-Tekeliphuta near Sivasagar in Assam[38][39] 2.8 km

Proposed and awaiting approval by MoRTH

[edit]

- Bridges on Brahmaputra:

These will reduce risk of blockades, logistics cost, travel time, boost economy, and enable India's Look-East and Neighbourhood-first connectivity.

- Barpeta-Nitarkhola Reserve bridge: half-way between Narnarayan Setu (Jogighopa) and Guwahati bridge, will reduce 140 km distance by 100 km to 40 km, vital for east Assam connectivity to south Assam, Meghalaya, Bangladesh and Tripura.

- Bhuragaon-Kaupati Bridge: near Morigaon half-way between Guwahati and Tezpur, it will reduce 180 km distance by 140 km to 40 km, vital for connecting Tawang and eastern end of East-West Arunachal Industrial Corridor Highway to South Assam, Tripura, Bangladesh, Manipur, Mizoram and Myanmar (Kaladan Project), all of which are vital for tourism and trade.

- Sadiya Sille-Oyan bridge, 40 km long road including bridges, from Sille-Oyan-Chilling Madhupur-Sadia over Brahmputra river will existing 180 km Sille-Oyan to Sadiya distance by 140 km and existing 150 km Pasighat-Sadiya distance by 110 km. It is vital for National Waterway 2 and East-West Arunachal Industrial Corridor Highway.

- Bridges on Padma River

- Dhulian bridge: between Pakur and Malda.

- Bridges on Subansiri River

- Narayanpur-Majuli Bridge to connect Narayanpur and Bodti Miri to Majuli Bridge. There is existing NH bridge near Gogamukh in north, another under construction Majuli-North Lakhimpur NH bridge in centre, and Narayanpur-Majuli Bridge in south will be third bridge.

- Bridges on Manas and Beki rivers: between Chapar and Barpeta on greenfield expressway

- Chamabati-Oudubi bridge

- Barjana-Moinbari bridge

- Balikuri-Barpeta bridge

Under-river tunnel

[edit]

- Numaligarh-Gohpur under-river tunnel.[44] The 15.6 km long tunnel, 22 metres below the river bed, will have 18 km approach roads to connect the NH-52 and Numaligarh on NH-37. This total ~33 km route will boost economy and strategic defence connectivity, protect Kaziranga National Park by diverting traffic away from the congested 2-lane highway through the park, shorten 223 km 6 hour long Gohpur-Numaligarh route to 35 km and 30 minutes, This twin tube tunnel, with an under road water drainage and overhead ventilation fans, will have inter-connectivity the twin tubs for evacuation. It will be equipped with sensors, CCTV, automated safety and traffic control systems. It will cost Rs 12,807 crore (US$1.7 billion in 2021).[45]

Bangladesh

[edit]

Present bridges in Bangladesh

[edit]- Bridges on Brahmaputra (Jamuna River)

- Bangabandhu Bridge (formerly Jamuna Bridge), road and rail bridge connects Siraiganj and Tangail on either side of the river.

- Bangabandhu Railway Bridge is under contraction railway bridge over Bramhmaputra River. It is connect Bangabandhu Bridge East Railway Station to Bangabandhu West Railway station

- Bridges on Padma River tributary of Brahmaputra

- Padma Bridge, road and rail bridge, south of Dhaka.

- Lalon Shah Bridge road bridge on Padma River tributary of Brahmaputra, near Ishwardi & Pabna.

- Hardinge Bridge, rail bridge on Padma River next to Lalon Shah Bridge.

Planned bridges in Bangladesh

[edit]

- Bridges on Brahmaputra (Jamuna River)

- Kurigram-Mankachar bridge, rail and road bridge connecting west Meghalaya (Mankachar) and north Bangladesh (Kurigram, Rangpur & Dinajpur) to north West Bengal (Cooch Behar & Siliguri) and Sikkim.

- Gaibandha-Bakshiganj Bridge, road and rail bridge to connect existing rail and road heads at Gaibandha-Bakshiganj on either side of the river. It will connect southwest Meghalaya (India) & south Assam (Silchar, India) to Bogura (Bangladesh), Malda (India), Bhagalpur (India) as an alternative to the chicken-neck Siliguri Corridor.

- Bogura-Jamalpur Gaibandha-Bakshiganj Bridge, road and rail bridge to connect Imphal-Silcher to Sylhet-Mymensingh-Bogura to Malda-Gaya-Patna.

- Shivalya-Golanda-Bhagulpur Bridge, road and rail bridge to connect existing rail and road heads at Siraiganj-Tangail on either side of the river.

- Chandpur Bridge, rail and road bridge to connect Northeast India (Aizawal-Rikhawdar in Mizoram & Udaipur in Tripura) to Bangladesh (Cumilla-Khulna) and Kolkata.

- Elisha-Lakshmipur Bridge, rail and road bridge to connect south Mizoram (Lunglei-Talabung) and south Tripura Sabroom to Feni-Barisal-Port of Mongla and Diamond Harbour-Haldia ports.

- Bridges on Padma river

- Rajshahi bridge

Tibet (China)

[edit]In course of last 64 years, since Tibet became part of China as an Autonomous region, at least 10 Bridges have been built on Brahmaputra River. Currently as per satellite imagery, only 4–5 bridges built on River Brahmaputra have been confirmed. These are as follows as per Google Map Satellite View:-

- Ziajhulinzhen Bridge, Built in 2009–2012 at 4,350 metres (14,270 ft), this is the Second longest Bridge on Brahmaputra river.

- Nyingchi Bridge, built in 2014 to connect Nyingchi with Lhasa by railway, this bridge is 750 metres (2,460 ft) long.

- Lasahe Bridge, built over Lhasa River, this road bridge is 929 metres (3,048 ft) long.

- Shigatse Bridge, this 2,750 metres (9,020 ft) long bridge built over Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) River to connect Lhasa with Shigatse by both road & Rail.

- Lhatse Bridge, this 2,250 metres (7,380 ft) long bridge built over Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) River to connect Kailash-Mansarovar region with Lhasa by Road.

- Shannan Bridge, this 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) long bridge built over Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) River to connect Lhasa with Nyingchi by road.

- Shangri Bridge, this 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) long bridge built over Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) River to connect Lhasa with Nyingchi by road.

- 3 more Bridges over Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) River is in Tibet (China) Autonomous Region, but details are unknown.

National Waterway 2 in India

[edit]National Waterway 2 (NW2) is 891 km long Sadiya-Dhubri stretch of Brahmaputra River in Assam.[46][47]

Cultural depictions

[edit]- Namami Brahmaputra Theme Song (in Hindi and Assamese) of Namami Brahmaputra festival.[48]

See also

[edit]- BrahMos (missile) – A missile named partly after the Brahmaputra River

- Brahmaputra-class frigate

- Dhola-Sadiya bridge

- List of rivers of Asia

- List of rivers of Assam

- List of rivers of Bangladesh

- List of rivers of China

- List of rivers of India

- Peninsular River System

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Biswa, Bhattacharya; Maurizio, Mazzoleni; Reyne, Ugay (2019). "Flood Inundation Mapping of the Sparsely Gauged Large-Scale Brahmaputra Basin Using Remote Sensing Products". Remote Sensing. 11 (5): 501. Bibcode:2019RemS...11..501B. doi:10.3390/rs11050501.

- ^ a b c "Scientists pinpoint sources of four major international rivers". Xinhua News Agency. 22 August 2011. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ganga (Ganges)-Brahmaputra".

- ^ Webersik, Christian (2010). Climate Change and Security: A Gathering Storm of Global Challenges. ABC-CLIO. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-313-38007-5. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Anne, Gädeke; Michel, Wortmann; Christoph, Menz; Saiful, Islam; Muhammad, Masood; Valentina, Krysanova; Stefan, Lange; Fred, Fokko Hattermann (2022). "Climate impact emergence and flood peak synchronization projections in the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna basins under CMIP5 and CMIP6 scenarios". Environmental Research Letters. 17 (9). Bibcode:2022ERL....17i4036G. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac8ca1.

- ^ a b c "Brahmaputra River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Brahmaputra River Flowing Down From Himalayas Towards Bay of Bengal". Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Singh, Vijay; Sharma, Nayan; Ojha, C. Shekhar P. (29 February 2004). The Brahmaputra Basin Water Resources. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 120. ISBN 9789048164813. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ "Water Resources of Bangladesh". FAO. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Catling, David (1992). Rice in deep water. International Rice Research Institute. p. 177. ISBN 978-971-22-0005-2. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 80.

- ^

Michael Buckley (30 March 2015). "The Price of Damming Tibet's Rivers". The New York Times. p. A25. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

Two of the continent's wildest rivers have their sources in Tibet: the Salween and the Brahmaputra Though yes they are under threat from retreating glaciers, a more immediate concern is Chinese engineering plans. A cascade of five large dams is planned for both the Salween, which now flows freely, and the Brahmaputra, where one dam is already operational.

- ^ Simpson, Thomas (25 October 2023). "Find the river: Discovering the Tsangpo-Brahmaputra in the age of empire". Modern Asian Studies. 58: 127–162. doi:10.1017/S0026749X23000288. ISSN 0026-749X.

- ^ Majuli, River Island. "Largest river island". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ a b c "Brahmaputra River – Map Tributaries Flow Bridges Tunnel". Rivers Of India – All About Rivers. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Singh, Vijay P.; Sharma, Nayan; C. Shekhar; P. Ojha (2004). The Brahmaputra Basin Water Resources. Springer. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4020-1737-7. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Igor Alekseevich, Shiklomanov (2009). Hydrological Cycle Volume III. EOLSS Publications. ISBN 978-1-84826-026-9.

- ^ The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica Educational Publishing. 2010. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-1-61530-202-4. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Suess, Eduard (1904). The face of the earth: (Das antlitz der erde). Clarendon press. pp. 50–. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Barman, Swapnali; Bhattacharjya, R. K. (2015). "Change in snow cover area of Brahmaputra river basin and its sensitivity to temperature". Environmental Systems Research. 4. doi:10.1186/s40068-015-0043-0.

- ^ Das, D.C. 2000. Agricultural Landuse and Productivity Pattern in Lower Brahmaputra valley (1970–71 and 1994–95). PhD Thesis, Department of Geography, North Eastern Hill University, Shillong.

- ^ Mipun, B.S. 1989. Impact of Migrants and Agricultural Changes in the Lower Brahmaputra Valley : A Case Study of Darrang District. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Department of Geography, North Eastern Hill University, Shillong.

- ^ Shrivastava, R.J.; Heinen, J.T. (2005). "Migration and Home Gardens in the Brahmaputra Valley, Assam, India". Journal of Ecological Anthropology. 9: 20–34. doi:10.5038/2162-4593.9.1.2. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Gilfellon, George; Sarma, Jogendra; Gohain, K. (August 2003). "Channel and Bed Morphology of a Part of the Brahmaputra River in Assam". Journal of the Geological Society of India. 62.

- ^ Monsoon Floods 2004: Post Flood Needs Assessment Summary Report (PDF). Bangladesh Disaster and Emergency Sub-Group (Report). Dhaka, Bangladesh. 2004. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ "China operationalizes biggest dam on Brahmaputra in Tibet". The Times of India. 13 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Syed, Dr. M.H; Bright, P.S. Assam General Knowledge. Bright Publications. ISBN 9788171994519. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ Burnell, A. C.; Yule, Henry (24 October 2018). Hobson-Jobson: Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words And Phrases. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-136-60332-7. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ e.g. Rennell, 1776; Rennel, 1787

- ^ a b "Tibet admits to Brahmaputra project". The Economic Times. 22 April 2010. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ MacArthur Foundation, Asian Security Initiative Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Chinese dam will not impact the flow of Brahmaputra: Krishna". The Indian Express. 22 April 2010. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ BBC (20 March 2014). "Megadams: Battle on the Brahmaputra". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Yeophantong, Pichamon (2017). "River activism, policy entrepreneurship and transboundary water disputes in Asia". Water International. 42 (2): 163–186. doi:10.1080/02508060.2017.1279041. S2CID 157181000.

- ^ "The New Nation, Bangladesh, 17 January 2010". Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ^ Sasidhar, Nallapaneni (May 2023). "Multipurpose Freshwater Coastal Reservoirs and Their Role in Mitigating Climate Change" (PDF). Indian Journal of Environment Engineering. 3 (1): 31–46. doi:10.54105/ijee.A1842.053123. ISSN 2582-9289. S2CID 258753397. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "PM Modi launches Mahabahu-Brahmaputra initiative ahead of polls in Assam – INSIDE NE". 18 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Nitin Gadkari flags off cargo movement on Brahmaputra Archived 2 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Economic Times, 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Karmakar, Rahul (24 May 2018). "Fencing to be over by December: Sonowal". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b PM Modi to Lay Foundation Stone of New Bridge Over Brahmaputra, Sentinel Assam, 5 November 2022.

- ^ Three More Bridges Over Brahmaputra to be Completed in Next Five Yrs: Assam CM, News18, 10 November 2022.

- ^ Connecting Guwahati City Via 'Mountains' On Centre's Cards, Sentinel Assam, 10 November 2022.

- ^ Assams first underwater tunnel DPR ready, 6000 crore project awaits cabinet nod, Economic Times, 4 Oct 2025.

- ^ Chaturvedi, Amit, ed. (14 July 2020). "Centre gives in-principle approval for tunnel under the Brahmaputra amid tension with China: Report". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ DAS GUPTA, MOUSHUMI DAS GUPTA, ed. (9 September 2021). "Modi govt proposes 15.6-km twin road tunnel of strategic importance under Brahmaputra". The Print. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "The National Waterways Act, 2016" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Press Information Bureau". www.pib.nic.in. Government of India. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Borah, Prabalika M. (22 March 2017). "Namami Brahmaputra". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rahaman, M. M.; Varis, O. (2009). "Integrated Water Management of the Brahmaputra Basin: Perspectives and Hope for Regional Development". Natural Resources Forum. 33 (1): 60–75. doi:10.1111/j.1477-8947.2009.01209.x.

- Sarma, J N (2005). "Fluvial process and morphology of the Brahmaputra River in Assam, India". Geomorphology. 70 (3–4): 226–256. Bibcode:2005Geomo..70..226S. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2005.02.007.

- Ribhaba Bharali. The Brahmaputra River Restoration Project. Published in Assamese Pratidin, Amar Assam in October 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law. Peace Palace Library

- Rivers of Dhemaji and Dhakuakhana

- Background to Brahmaputra Flood Scenario

- The Mighty Brahmaputra

- Principal Rivers of Assam

- "The Brahmaputra", a detailed study of the river by renowned writer Arup Dutta. (Published by National Book Trust, New Delhi, India)

- Émilie Crémin. Entre mobilité et sédentarité : les Mising, "peuple du fleuve", face à l'endiguement du Brahmapoutre (Assam, Inde du Nord-Est). Milieux et Changements globaux. Université Paris 8 Vincennes Saint-Denis, 2014. Français. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01139754

- My Trip of Mighty Brahmaputra (in Gujarati)

External links

[edit] Media related to Brahmaputra at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Brahmaputra at Wikimedia Commons

Brahmaputra River

View on GrokipediaNames and Etymology

Regional Designations

The Brahmaputra River is designated by distinct names in the regions it traverses, corresponding to local linguistic and cultural contexts. In its upper reaches within the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, it is known as the Yarlung Tsangpo, a Tibetan name signifying "the purifier," as it flows eastward through the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon before turning south.[10][11] Upon crossing into India through Arunachal Pradesh, the river assumes the name Siang (or alternatively Dihang) among local communities, reflecting indigenous nomenclature for this stretch where it descends from the Himalayas and begins widening.[11][12] Further downstream in the Assam Valley, it is universally referred to as the Brahmaputra, a Sanskrit-derived term meaning "son of Brahma," which has been standardized in official Indian geographical records since at least the British colonial era's surveys in the 19th century.[12][11] In Bangladesh, the river's main channel is designated the Jamuna, a name used for its braided, sediment-laden course from the Indian border until its confluence with the Ganges near Goalanda, after which the combined flow is called the Padma until merging with the Meghna estuary.[11] These designations highlight the river's transboundary nature, with variations arising from phonetic adaptations and hydrological distinctions rather than unified international nomenclature.[13]Linguistic and Historical Origins

The name Brahmaputra originates from Sanskrit, where it is a compound of Brahma—referring to the creator deity in Hindu cosmology—and putra, meaning "son," thus signifying "son of Brahma."[14][15] This etymology underscores the river's mythological personification as a male entity, unique among major Indian rivers, which are typically denoted with the feminine suffix nadi (river); in regional Assamese and related scriptures, it is instead invoked as nad (masculine form).[16][17] Mythological narratives in ancient Hindu texts, such as the Kalikapurana, elaborate this origin by attributing the river's birth to Amogha, the wife of sage Shantanu, who conceived it through divine intervention linked to Brahma, thereby embedding the name in a framework of cosmic progeny and sacred geography.[18] Historical linguistic evidence from pre-Sanskrit influences in the Assam region points to earlier indigenous designations, including Lao-Tu—with its Bodo derivation Ti-Lao—ascribed to Austro-Asiatic speakers who inhabited the area prior to Indo-Aryan expansions, reflecting local ethnolinguistic layers predating the widespread adoption of the Sanskrit term around the early medieval period.[19] In its Tibetan upper course, the river bears the ancient name Tsangpo (or Yarlung Tsangpo), derived from Tibetan roots connoting "purifier," a term documented in historical accounts emphasizing its role in regional hydrology and Buddhist cosmology, independent of the downstream Sanskrit nomenclature.[13] These varied linguistic origins illustrate the river's traversal of distinct cultural spheres, with the Sanskrit Brahmaputra gaining prominence in Indian historical records from at least the 1st millennium CE, as Indo-Aryan influences integrated with local substrates in the Brahmaputra Valley.[20]Physical Geography

Origin and Upper Reaches in Tibet

The Brahmaputra River originates in western Tibet from the Angsi Glacier, also known as Jiemayangzong Glacier, at an elevation of approximately 5,390 meters above sea level, located near coordinates 30°20′N 82°03′E in Burang County, close to Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar.[21] [1] In Tibet, the river is known as the Yarlung Tsangpo, meaning "the purifier from high land" or "the river from the highest land," reflecting its high-altitude source on the Tibetan Plateau.[22] The initial flow emerges from glacial melt, with the Angsi Glacier spanning about 20 kilometers in length and contributing to the river's headwaters amid the Kailash Range's rugged terrain.[21] From its source, the Yarlung Tsangpo flows eastward for roughly 1,700 kilometers across the southern margin of the Tibetan Plateau, maintaining an average elevation of around 4,000 meters, the highest of any major river globally.[23] This upper course traverses the arid South Tibet Valley, a tectonically active region characterized by braided channels, glacial outwash plains, and minimal vegetation due to low annual precipitation of less than 500 millimeters, largely attributable to the rain-shadow effect of the Himalayan barrier.[23] [24] Discharge in this stretch remains modest, primarily sustained by seasonal snowmelt and contributions from smaller tributaries such as the Raka Chu and Kyichu, with average flows increasing gradually from under 100 cubic meters per second near the source to several hundred by Lhasa.[25] Near the eastern end of the plateau, at approximately longitude 95°E, the river executes a dramatic 180-degree turn southward, entering the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, where it descends over 2,000 meters in a distance of about 240 kilometers around Mount Namcha Barwa (7,782 meters).[23] This "Great Bend" features the world's deepest canyon, with local relief exceeding 5,300 meters carved into resistant granitic bedrock by megafloods and sustained fluvial incision, driven by high-velocity flows and tectonic uplift.[23] [26] The canyon's hydrology is influenced by episodic glacial lake outbursts and landslides, which have historically dammed the river, leading to sudden releases that enhance erosive power.[27] Beyond the bend, the river exits Tibet into Arunachal Pradesh, India, marking the transition from its Tibetan upper reaches.[26]Course Through India

The Brahmaputra enters India as the Siang or Dihang River in Arunachal Pradesh, west of the Namcha Barwa peak, after traversing a deep gorge across the eastern Himalayan ranges.[1] In this upper reach, the river flows southward through rugged terrain, characterized by narrow valleys and steep gradients, covering approximately 230 kilometers before broadening.[12] Near the town of Sadiya, it receives the Dibang and Lohit rivers, significant tributaries that substantially augment its discharge, at which point the river assumes the name Brahmaputra.[12] Upon entering the Assam plains, the Brahmaputra shifts to a southwesterly direction, transitioning from a single-channel flow to a wide, braided anastomosing system amid the alluvial floodplains of the Assam Valley.[1] This section spans roughly 916 kilometers through Assam, where the river's channel meanders extensively, with widths typically ranging from 12 to 18 kilometers, expanding further during monsoonal floods due to high sediment deposition and bank erosion.[28][29] The river's depth varies, reaching up to 100 meters in places, supporting navigation but prone to shifting sandbars and avulsions.[12] Key settlements along this course include Dibrugarh upstream, where tea estates border the banks; Tezpur and Guwahati, major urban centers connected by bridges such as the Saraighat Bridge near Guwahati, India's longest river bridge at the time of its 1962 completion; and Dhubri near the Bangladesh border.[12] The river bisects Majuli, the world's largest river island, formed by fluvial deposition and subject to ongoing erosion, highlighting the dynamic morphology driven by the Brahmaputra's immense sediment load exceeding 1 billion tons annually.[12] Exiting India at Dhubri, the Brahmaputra continues into Bangladesh as the Jamuna River, having traversed northeastern India's tectonically active and seismically vulnerable terrain.[1]Delta and Lower Reaches in Bangladesh

The Brahmaputra River enters Bangladesh from India near Chilmari and continues southward as the Jamuna River, spanning approximately 220 kilometers before its confluence with the Padma River.[30] The Jamuna constitutes one of the world's largest sand-bed braided rivers, characterized by multiple active channels, high sediment loads, and dynamic planform adjustments due to its high-energy flow regime.[31] River widths vary significantly, ranging from 3 to 20 kilometers, with frequent shifts in channel position driven by seasonal floods and sediment deposition.[32] The Jamuna merges with the Padma River—the lower course of the Ganges—north of Goalundo Ghat in central Bangladesh, forming the Padma, which carries the combined discharge southeastward toward the Bay of Bengal.[33] The Padma subsequently joins the Meghna River, collectively feeding into the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) delta, the largest Holocene delta globally, encompassing a subaerial area of about 110,000 square kilometers, with the majority situated within Bangladesh.[34] This delta plain features extensive tidal channels, mangrove forests such as the Sundarbans, and active sediment progradation, though portions face subsidence and erosion pressures.[35] Hydrologically, the Jamuna's average annual discharge measures around 19,600 cubic meters per second, escalating to bankfull levels of approximately 48,000 cubic meters per second during monsoons, contributing to the GBM system's total annual freshwater output of roughly 1 × 10¹² cubic meters, 80% of which occurs in the wet season from June to October.[36][37] Sediment transport through the Jamuna reaches 590 to 792 million tons annually, with the Brahmaputra's flux estimated at 135 to 615 million tons per year, fueling delta aggradation but also inducing channel avulsions and bank erosion impacting 2,000 to 5,000 hectares yearly.[38][39] Flooding patterns peak between July and September, exacerbated by the river's braided morphology and upstream monsoon precipitation, leading to widespread inundation across the floodplain.[6]Basin Extent and Topography

The Brahmaputra River basin encompasses an area of approximately 580,000 square kilometers, spanning four countries: China (primarily Tibet), India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh.[7] The basin's irregular shape features a maximum east-west extent of 1,540 kilometers and a maximum north-south width of 682 kilometers. In terms of distribution, China accounts for about 50.5% of the basin area, India 33.6%, Bangladesh 8.1%, and Bhutan 7.8%.[40] Specific catchment areas include 293,000 square kilometers in Tibet, 240,000 square kilometers jointly in India and Bhutan, and 47,000 square kilometers in Bangladesh.[3] Topographically, the basin transitions from the high-elevation Tibetan Plateau in its upper reaches, with average basin elevations around 1,923 meters, maximum heights up to 6,033 meters, and minimums near 180 meters.[41] In Tibet, the river descends steeply, dropping about 4,800 meters over roughly 1,700 kilometers, yielding an average slope of approximately 2.82 meters per kilometer before entering India.[3] This segment features rugged Himalayan terrain, deep gorges, and tectonic influences from ongoing orogenic activity associated with the India-Asia collision. Upon crossing into India via Arunachal Pradesh, the topography shifts to narrow, antecedent gorges through the Eastern Himalayas, followed by entry into the broader Assam Valley plains, where elevations drop to under 100 meters.[7] The middle basin in Assam comprises alluvial plains with braided river channels, extensive floodplains, and meandering tributaries dissecting the landscape. In Bangladesh, the lower basin flattens into the vast Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, characterized by low-lying sedimentary deposits, tidal influences, and subsiding coastal topography prone to sea-level interactions.[7]| Country/Region | Basin Area (km²) | Approximate Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| China (Tibet) | 293,000 | 50.5% |

| India | ~195,000 | 33.6% |

| Bhutan | ~45,000 | 7.8% |

| Bangladesh | 47,000 | 8.1% |

Hydrology and Flow Dynamics

Discharge Regimes and Seasonal Variations

The discharge regime of the Brahmaputra River is predominantly pluvial, dominated by monsoon precipitation across its extensive basin, with subordinate contributions from Himalayan snowmelt and glacial melt in the upper reaches. Annual average discharge, measured at gauging stations such as Bahadurabad in Bangladesh, reaches approximately 20,000 m³/s, ranking among the highest globally due to the basin's high rainfall intensity and relief-driven runoff efficiency.[37] This flow is sustained by a combination of surface runoff from intense seasonal rains and baseflow from permeable aquifers in the alluvial plains, though the latter diminishes markedly outside the monsoon period. Hydrological studies indicate that over 80% of annual discharge occurs during the four-month monsoon window, reflecting the river's sensitivity to atmospheric circulation patterns like the Indian Summer Monsoon.[43] Seasonal variations exhibit extreme contrasts, with dry-season (November–May) flows averaging 3,000–5,000 m³/s, primarily from residual snowmelt in Tibetan headwaters and minimal precipitation. Monsoon onset in June triggers rapid escalation, with monthly averages climbing to 44,800 m³/s by July before tapering through September.[4] Peak daily discharges frequently surpass 100,000 m³/s during July–August flood pulses, as documented in events like the 1998 monsoon when 10-day means hit 94,000 m³/s—over twice the seasonal median.[6] These surges result from synchronized heavy orographic rainfall in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam sub-basins, compounded by early snowmelt contributions estimated at 11% of monsoon flow.[44] Intra-seasonal variability introduces multiple discharge peaks, driven by staggered precipitation fronts and melt cycles, amplifying flood risks.[43] Long-term reconstructions reveal that while mean monsoon discharges have shown regime shifts, such as a 10–80% increase in water yield post-1990s linked to climatic warming and altered precipitation distribution, peak flows remain tightly coupled to seasonal totals.[45] ENSO phases and regional teleconnections further modulate variability, with El Niño conditions often suppressing pre-monsoon flows but enhancing post-monsoon extremes in downstream reaches.[46] Such dynamics underscore the river's high coefficient of variation in discharge—exceeding 50% annually—necessitating robust gauging networks for prediction, as evidenced by multi-model forecasts achieving low error margins at key stations.[47]Flooding Mechanisms and Patterns

The Brahmaputra River experiences recurrent flooding primarily due to intense monsoon precipitation across its basin, which elevates discharge levels from May to September, with peak flows often exceeding 100,000 cubic meters per second during extreme events. This seasonal surge, driven by orographic rainfall in the eastern Himalayas and upstream Tibetan Plateau, combines with contributions from over 50 tributaries and glacial meltwater, overwhelming the river's braided channel capacity in the Assam Valley and downstream delta regions. High sediment loads, estimated at up to 1.1 billion tons annually from Himalayan erosion, exacerbate flooding by promoting channel aggradation, shallowing, and lateral migration, which reduce conveyance efficiency and trigger overbank spilling.[6][48][35] Bank erosion and morphological instability further amplify flood vulnerability, as the river's multi-threaded, anabranching pattern in Assam leads to rapid shifts in active channels, with average annual southward migration rates of 109 meters observed over the past 50 years in the lower valley, resulting in approximately 100 square kilometers of land loss. Tectonic uplift and seismic activity in the basin can induce landslides that temporarily block tributaries, causing sudden releases of impounded water upon breaching, though monsoon hydrology remains the dominant trigger. In Bangladesh, confluence dynamics with the Ganges amplify inundation, where synchronized peaks can submerge up to 70% of the delta plain during prolonged events lasting over 10 days.[49][50][6] Flood patterns exhibit strong seasonality, with 80-90% of annual rainfall concentrated in the June-September monsoon, leading to near-annual inundations in Assam's 56,480 square kilometer floodplain and recurrent crises in Bangladesh's low-lying areas. Historical reconstructions from tree-ring data spanning seven centuries indicate that long-duration floods (>10 days) predominate in July-September, with modern risks underestimated by 24-38% relative to pre-industrial variability due to amplified discharge extremes. Notable events include the 1998 floods, which affected nearly 70% of Bangladesh and Assam through sustained high flows, and recurring incidents in 2007 and 2011 tied to excessive northeastern Indian and Bhutanese rainfall. Regional susceptibility mapping highlights high-risk zones in Assam districts like Dhemaji, Dibrugarh, and Majuli, where braided morphology and embankment breaches compound agricultural and infrastructural damage.[48][6][51]Sediment Transport and Channel Evolution

The Brahmaputra River exhibits one of the highest sediment transport capacities among global rivers, delivering an estimated 400–700 million tonnes of sediment annually to the Bengal Delta, primarily during the summer monsoon when ~95% of the load is mobilized.[43] [35] This flux arises from intense erosion in the Eastern Himalayan syntaxis and Tibetan Plateau, contributing ~45% of modern sediment, supplemented by inputs from the Himalayan foothills.[52] Suspended load dominates, consisting mainly of silt, while bedload (15–25% of total) comprises sand transported along the channel bed.[53] Overall efficiency remains low, with the Tibetan Plateau sourcing only ~18% of sands reaching downstream due to deposition in upstream gorges and valleys.[54] High sediment supply relative to discharge in the Assam plains fosters a braided channel morphology, characterized by multiple shifting anabranches, mobile sand bars, and meta-stable islands separated by nodal reaches prone to erosion.[55] This pattern evolves through aggradation-induced channel instability, where sediment deposition raises bed levels, promoting lateral migration and bifurcation; dominant discharges of ~20,000–30,000 m³/s exacerbate bar formation and bank scour.[56] Avulsions occur frequently as threads of braided channels shift coherently or abruptly, capturing adjacent distributaries and altering planform over decadal scales.[57] Historical records document six major avulsions in the Holocene, with the river alternating between eastern and western distributaries in Bangladesh; the latest cycle began in the 18th century when a small stream captured the main channel, initiating shifts around 1780–1800 via multi-channel breaches.[58] [59] These events, driven by sediment choking and floodplain gradient advantages, have redistributed ~40% of annual suspended load within the system, sustaining delta progradation while causing severe local erosion rates exceeding 100 m/year in unstable reaches.[60] Seismic events, such as the 1950 Assam earthquake, further accelerate morphological shifts by enhancing post-event sedimentation and channel widening.[61] Projections indicate potential increases in sediment flux by up to 40% under altered monsoon regimes, amplifying braiding dynamics and avulsion risks.[62]Tributaries and Drainage Network

Major Left-Bank Tributaries

The major left-bank tributaries of the Brahmaputra River drain from the southern hill ranges, including the Patkai and Naga hills, as well as Meghalaya plateau, joining the main stem from the left when facing downstream in its eastward course through Assam. These tributaries, such as the Burhi Dihing, Disang, Dikhu, Kopili, and Dhansiri, contribute sediment and water volume influenced by monsoon precipitation in their catchments, supporting agricultural and ecological systems in the valley but also exacerbating flood risks due to their seasonal high discharges.[63][1] The Burhi Dihing River, one of the larger left-bank contributors, originates in the Naga hills of Nagaland and extends approximately 362 kilometers northward to confluence with the Brahmaputra near Dibrugarh in Assam, with its basin covering parts of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam and characterized by braided channels prone to shifting.[1] The Disang and Dikhu rivers, both rising in the Patkai range, flow northwest for about 200-300 kilometers each, merging with the Brahmaputra downstream of Sivasagar; their combined flow adds to the sediment load, promoting deltaic deposition downstream.[63] Further west, the Kopili River emerges from the Saipong Reserve Forest in southern Karbi Anglong district, traversing roughly 297 kilometers through Meghalaya and Assam before joining near Guwahati, notable for its hydropower potential and role in linking the Barak and Brahmaputra systems via the Jamuna.[1] The Dhansiri River, with its southern branch from Nagaland hills, spans over 350 kilometers and joins near Jorhat, draining a catchment of about 11,540 square kilometers and contributing to frequent flooding in adjacent lowlands due to its steep gradient and heavy siltation.[12] These tributaries collectively account for a substantial portion of the Brahmaputra's southern inflow, though their discharges vary markedly, peaking at 5,000-10,000 cubic meters per second during monsoons based on gauged records from regional hydrological stations.[64]Major Right-Bank Tributaries

The major right-bank tributaries of the Brahmaputra River originate predominantly from the Himalayan ranges in Arunachal Pradesh, Bhutan, and Sikkim, entering the main channel from the northern (right) bank as the river flows westward through India and into Bangladesh. These tributaries, characterized by steep gradients in their upper reaches and significant sediment loads, contribute substantially to the Brahmaputra's high discharge, with collective inputs accounting for a large portion of the river's annual flow volume, particularly during the monsoon season when peak discharges can exceed tens of thousands of cubic meters per second. Their basins cover rugged terrain, fostering hydropower potential but also exacerbating downstream flooding due to rapid runoff and erosion.[1][12] The Subansiri River, the largest right-bank tributary, originates from glacial sources near Mount Kula in the Tibet Autonomous Region at an elevation of approximately 5,000 meters, flowing southward for about 442 kilometers through Arunachal Pradesh before joining the Brahmaputra near Lakhimpur in Assam. Its catchment area spans roughly 35,000 square kilometers, predominantly in steep Himalayan terrain, and it contributes around 10% of the Brahmaputra's total annual discharge, with recorded maximum flows reaching 18,500 cubic meters per second. The river's high sediment transport supports delta formation downstream but poses challenges for infrastructure, including the proposed 2,000 MW Subansiri Lower Dam, which has faced delays due to seismic risks and ecological concerns.[1][65][66] Further downstream, the Kameng River (also known as Jia Bharali or Bharali) rises in the Tawang district of Arunachal Pradesh from Himalayan snowmelt and rainfall, traversing approximately 264 kilometers through West Kameng and East Kameng districts before merging with the Brahmaputra near Tezpur in Assam. With a basin area of about 10,000 square kilometers, it delivers peak discharges exceeding 5,000 cubic meters per second during monsoons, feeding into biodiversity hotspots like Kaziranga National Park and enabling hydropower projects such as the 1,000 MW Kameng Hydroelectric Project. Its course features braided channels prone to shifting, influencing local agriculture and flood patterns.[12][1] The Manas River, a transboundary waterway, emerges from the southern slopes of Bhutan's Black Mountains at elevations over 4,000 meters, covering 376 kilometers (of which 272 kilometers are in Bhutan) before confluence with the Brahmaputra at Jogighopa in Assam's Dhubri district. Its 41,000 square kilometer basin yields maximum discharges of 7,641 cubic meters per second, supporting the Manas Wildlife Sanctuary—a UNESCO World Heritage Site harboring endangered species like the Bengal tiger—and facilitating cross-border water sharing agreements between India and Bhutan. The river's meandering lower reaches contribute to fertile alluvial soils but amplify erosion in the Indo-Bhutan border regions.[12][1][67] In the western reaches, the Sankosh (or Raidak) River originates from Bhutan's northern Himalayan glaciers, flowing 320 kilometers southward to join the Brahmaputra near the India-Bangladesh border. Its basin, covering 6,970 square kilometers in India, experiences high seasonal variability with monsoonal peaks aiding irrigation but contributing to avulsions and channel migration. Similarly, the Teesta River, sourcing from Tso Lhamo Lake in Sikkim at 5,330 meters, travels 414 kilometers through steep gorges, augmented by the Rangeet tributary, before entering the Brahmaputra (as Jamuna) in Bangladesh near Chilmari; its 12,540 square kilometer basin drives the contentious Teesta barrage projects amid India-Bangladesh water disputes, with average discharges around 1,000 cubic meters per second rising dramatically in floods. These tributaries collectively enhance the Brahmaputra's hydrological regime while underscoring regional interdependencies in water management.[12][1][63]| Tributary | Origin | Length (km) | Catchment Area (km²) | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subansiri | Tibet (near Mt. Kula) | 442 | ~35,000 | ~10% of Brahmaputra discharge; hydropower potential[65] |

| Kameng (Jia Bharali) | Arunachal Pradesh (Tawang) | ~264 | ~10,000 | Flood peaks >5,000 m³/s; biodiversity support[12] |

| Manas | Bhutan (Black Mountains) | 376 | ~41,000 (total) | Max discharge 7,641 m³/s; UNESCO sanctuary[67] |

| Sankosh (Raidak) | Bhutan Himalayas | 320 | ~6,970 (India) | Seasonal irrigation; border erosion[12] |

| Teesta | Sikkim (Tso Lhamo Lake) | 414 | ~12,540 | Barrage disputes; avg. 1,000 m³/s[63] |

Hydrological Contributions