Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Construction

View on Wikipedia

Construction is the process involved in delivering buildings, infrastructure, industrial facilities, and associated activities through to the end of their life. It typically starts with planning, financing, and design that continues until the asset is built and ready for use. Construction also covers repairs and maintenance work, any works to expand, extend and improve the asset, and its eventual demolition, dismantling or decommissioning.

The construction industry contributes significantly to many countries' gross domestic products (GDP). Global expenditure on construction activities was about $4 trillion in 2012. In 2022, expenditure on the construction industry exceeded $11 trillion a year, equivalent to about 13 percent of global GDP. This spending was forecasted to rise to around $14.8 trillion in 2030.[1]

The construction industry promotes economic development and brings many non-monetary benefits to many countries, but it is one of the most hazardous industries. For example, about 20% (1,061) of US industry fatalities in 2019 happened in construction.[2]

Etymology

[edit]"Construction" stems from the Latin word constructio (which comes from com- "together" and struere "to pile up") as well as Old French construction.[3] "To construct" is a verb: the act of building. The noun is "construction": how something is built or the nature of its structure.

History

[edit]

The first huts and shelters were constructed by hand or with simple tools. As cities grew during the Bronze Age, a class of professional craftsmen, like bricklayers and carpenters, appeared. Occasionally, slaves were used for construction work. In the Middle Ages, the artisan craftsmen were organized into guilds. In the 19th century, steam-powered machinery appeared, and later, diesel- and electric-powered vehicles such as cranes, excavators and bulldozers.

Fast-track construction has been increasingly popular in the 21st century. Some estimates suggest that 40% of construction projects are now fast-track construction.[4]

Construction industry sectors

[edit]

Broadly, there are three sectors of construction: buildings, infrastructure and industrial:[5]

- Building construction is usually further divided into residential and non-residential.

- Infrastructure, also called 'heavy civil' or 'heavy engineering', includes large public works, dams, bridges, highways, railways, water or wastewater and utility distribution.

- Industrial construction includes offshore construction (mainly of energy installations), mining and quarrying, refineries, chemical processing, mills and manufacturing plants.

The industry can also be classified into sectors or markets.[6] For example, Engineering News-Record (ENR), a US-based construction trade magazine, has compiled and reported data about the size of design and construction contractors. In 2014, it split the data into nine market segments: transportation, petroleum, buildings, power, industrial, water, manufacturing, sewage/waste, telecom, hazardous waste, and a tenth category for other projects.[7] ENR used data on transportation, sewage, hazardous waste and water to rank firms as heavy contractors.[8]

The Standard Industrial Classification and the newer North American Industry Classification System classify companies that perform or engage in construction into three subsectors: building construction, heavy and civil engineering construction, and specialty trade contractors. There are also categories for professional services firms (e.g., engineering, architecture, surveying, project management).[9][10]

Building construction

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Building construction is the process of adding structures to areas of land, also known as real property sites. Typically, a project is instigated by or with the owner of the property (who may be an individual or an organisation); occasionally, land may be compulsorily purchased from the owner for public use.[11]

Residential construction

[edit]

Residential construction may be undertaken by individual land-owners (self-built), by specialist housebuilders, by property developers, by general contractors, or by providers of public or social housing (e.g.: local authorities, housing associations). Where local zoning or planning policies allow, mixed-use developments may comprise both residential and non-residential construction (e.g.: retail, leisure, offices, public buildings, etc.).

Residential construction practices, technologies, and resources must conform to local building authority's regulations and codes of practice. Materials readily available in the area generally dictate the construction materials used (e.g.: brick versus stone versus timber). Costs of construction on a per square meter (or per square foot) basis for houses can vary dramatically based on site conditions, access routes, local regulations, economies of scale (custom-designed homes are often more expensive to build) and the availability of skilled tradespeople.[12]

Non-residential construction

[edit]

Depending upon the type of building, non-residential building construction can be procured by a wide range of private and public organisations, including local authorities, educational and religious bodies, transport undertakings, retailers, hoteliers, property developers, financial institutions and other private companies. Most construction in these sectors is undertaken by general contractors.

Infrastructure construction

[edit]

Civil engineering covers the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, tunnels, airports, water and sewerage systems, pipelines, and railways.[13][14] Some general contractors have expertise in civil engineering; civil engineering contractors are firms dedicated to work in this sector, and may specialise in particular types of infrastructure.

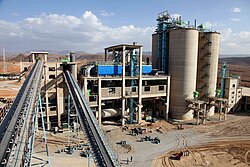

Industrial construction

[edit]

Industrial construction includes offshore construction (mainly of energy installations: oil and gas platforms, wind power), mining and quarrying, refineries, breweries, distilleries and other processing plants, power stations, steel mills, warehouses and factories.

Construction processes

[edit]Some construction projects are small renovations or repair jobs, like repainting or fixing leaks, where the owner may act as designer, paymaster and laborer for the entire project. However, more complex or ambitious projects usually require additional multi-disciplinary expertise and manpower, so the owner may commission one or more specialist businesses to undertake detailed planning, design, construction and handover of the work. Often the owner will appoint one business to oversee the project (this may be a designer, a contractor, a construction manager, or other advisors); such specialists are normally appointed for their expertise in project delivery and construction management and will help the owner define the project brief, agree on a budget and schedule, liaise with relevant public authorities, and procure materials and the services of other specialists (the supply chain, comprising subcontractors and materials suppliers). Contracts are agreed for the delivery of services by all businesses, alongside other detailed plans aimed at ensuring legal, timely, on-budget and safe delivery of the specified works.

Design, finance, and legal aspects overlap and interrelate. The design must be not only structurally sound and appropriate for the use and location, but must also be financially possible to build, and legal to use. The financial structure must be adequate to build the design provided and must pay amounts that are legally owed. Legal structures integrate design with other activities and enforce financial and other construction processes.

These processes also affect procurement strategies. Clients may, for example, appoint a business to design the project, after which a competitive process is undertaken to appoint a lead contractor to construct the asset (design–bid–build); they may appoint a business to lead both design and construction (design-build); or they may directly appoint a designer, contractor and specialist subcontractors (construction management).[15] Some forms of procurement emphasize collaborative relationships (partnering, alliancing) between the client, the contractor, and other stakeholders within a construction project, seeking to ameliorate often highly competitive and adversarial industry practices. DfMA (design for manufacture and assembly) approaches also emphasize early collaboration with manufacturers and suppliers regarding products and components.

Construction or refurbishment work in a "live" environment (where residents or businesses remain living in or operating on the site) requires particular care, planning and communication.[16]

Planning

[edit]

When applicable, a proposed construction project must comply with local land-use planning policies including zoning and building code requirements. A project will normally be assessed (by the 'authority having jurisdiction', AHJ, typically the municipality where the project will be located) for its potential impacts on neighbouring properties, and upon existing infrastructure (transportation, social infrastructure, and utilities including water supply, sewerage, electricity, telecommunications, etc.). Data may be gathered through site analysis, site surveys and geotechnical investigations. Construction normally cannot start until planning permission has been granted, and may require preparatory work to ensure relevant infrastructure has been upgraded before building work can commence. Preparatory works will also include surveys of existing utility lines to avoid damage-causing outages and other hazardous situations.

Some legal requirements come from malum in se considerations, or the desire to prevent indisputably bad phenomena, e.g. explosions or bridge collapses. Other legal requirements come from malum prohibitum considerations, or factors that are a matter of custom or expectation, such as isolating businesses from a business district or residences from a residential district. An attorney may seek changes or exemptions in the law that governs the land where the building will be built, either by arguing that a rule is inapplicable (the bridge design will not cause a collapse), or that the custom is no longer needed (acceptance of live-work spaces has grown in the community).[17]

During the construction of a building, a municipal building inspector usually inspects the ongoing work periodically to ensure that construction adheres to the approved plans and the local building code. Once construction is complete, any later changes made to a building or other asset that affect safety, including its use, expansion, structural integrity, and fire protection, usually require municipality approval.

Finance

[edit]Depending on the type of project, mortgage bankers, accountants, and cost engineers may participate in creating an overall plan for the financial management of a construction project. The presence of the mortgage banker is highly likely, even in relatively small projects since the owner's equity in the property is the most obvious source of funding for a building project. Accountants act to study the expected monetary flow over the life of the project and to monitor the payouts throughout the process. Professionals including cost engineers, estimators and quantity surveyors apply expertise to relate the work and materials involved to a proper valuation.

Financial planning ensures adequate safeguards and contingency plans are in place before the project is started, and ensures that the plan is properly executed over the life of the project. Construction projects can suffer from preventable financial problems.[18] Underbids happen when builders ask for too little money to complete the project. Cash flow problems exist when the present amount of funding cannot cover the current costs for labour and materials; such problems may arise even when the overall budget is adequate, presenting a temporary issue. Cost overruns with government projects have occurred when the contractor identified change orders or project changes that increased costs, which are not subject to competition from other firms as they have already been eliminated from consideration after the initial bid.[19] Fraud is also an issue of growing significance within construction.[20]

Large projects can involve highly complex financial plans and often start with a conceptual cost estimate performed by a building estimator. As portions of a project are completed, they may be sold, supplanting one lender or owner for another, while the logistical requirements of having the right trades and materials available for each stage of the building construction project carry forward. Public–private partnerships (PPPs) or private finance initiatives (PFIs) may also be used to help deliver major projects. According to McKinsey in 2019, the "vast majority of large construction projects go over budget and take 20% longer than expected".[21]

Legal

[edit]

A construction project is a complex net of construction contracts and other legal obligations, each of which all parties must carefully consider. A contract is the exchange of a set of obligations between two or more parties, and provides structures to manage issues. For example, construction delays can be costly, so construction contracts set out clear expectations and clear paths to manage delays. Poorly drafted contracts can lead to confusion and costly disputes.

At the start of a project, legal advisors seek to identify ambiguities and other potential sources of trouble in the contract structures, and to present options for preventing problems. During projects, they work to avoid and resolve conflicts that arise. In each case, the lawyer facilitates an exchange of obligations that matches the reality of the project.

Procurement

[edit]Traditional or design-bid-build

[edit]Design-bid-build is the most common and well-established method of construction procurement. In this arrangement, the architect, engineer or builder acts for the client as the project coordinator. They design the works, prepare specifications and design deliverables (models, drawings, etc.), administer the contract, tender the works, and manage the works from inception to completion. In parallel, there are direct contractual links between the client and the main contractor, who, in turn, has direct contractual relationships with subcontractors. The arrangement continues until the project is ready for handover.

Design-build

[edit]Design-build became more common from the late 20th century, and involves the client contracting a single entity to provide design and construction. In some cases, the design-build package can also include finding the site, arranging funding and applying for all necessary statutory consents. Typically, the client invites several Design & Build (D&B) contractors to submit proposals to meet the project brief and then selects a preferred supplier. Often this will be a consortium involving a design firm and a contractor (sometimes more than one of each). In the United States, departments of transportation usually use design-build contracts as a way of progressing projects where states lack the skills or resources, particularly for very large projects.[22]

Construction management

[edit]In a construction management arrangement, the client enters into separate contracts with the designer (architect or engineer), a construction manager, and individual trade contractors. The client takes on the contractual role, while the construction or project manager provides the active role of managing the separate trade contracts, and ensuring that they complete all work smoothly and effectively together. This approach is often used to speed up procurement processes, to allow the client greater flexibility in design variation throughout the contract, to enable the appointment of individual work contractors, to separate contractual responsibility on each individual throughout the contract, and to provide greater client control.

Design

[edit]In the industrialized world, construction usually involves the translation of designs into reality. Most commonly (i.e.: in a design-bid-build project), the design team is employed by (i.e. in contract with) the property owner. Depending upon the type of project, a design team may include architects, civil engineers, mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, structural engineers, fire protection engineers, planning consultants, architectural consultants, and archaeological consultants. A 'lead designer' will normally be identified to help coordinate different disciplinary inputs to the overall design. This may be aided by integration of previously separate disciplines (often undertaken by separate firms) into multi-disciplinary firms with experts from all related fields,[23] or by firms establishing relationships to support design-build processes.

The increasing complexity of construction projects creates the need for design professionals trained in all phases of a project's life-cycle and develop an appreciation of the asset as an advanced technological system requiring close integration of many sub-systems and their individual components, including sustainability. For buildings, building engineering is an emerging discipline that attempts to meet this new challenge.

Traditionally, design has involved the production of sketches, architectural and engineering drawings, and specifications. Until the late 20th century, drawings were largely hand-drafted; adoption of computer-aided design (CAD) technologies then improved design productivity, while the 21st-century introduction of building information modeling (BIM) processes has involved the use of computer-generated models that can be used in their own right or to generate drawings and other visualisations as well as capturing non-geometric data about building components and systems.

On some projects, work on-site will not start until design work is largely complete; on others, some design work may be undertaken concurrently with the early stages of on-site activity (for example, work on a building's foundations may commence while designers are still working on the detailed designs of the building's internal spaces). Some projects may include elements that are designed for off-site construction (see also prefabrication and modular building) and are then delivered to the site ready for erection, installation or assembly.

On-site construction

[edit]

Once contractors and other relevant professionals have been appointed and designs are sufficiently advanced, work may commence on the project site. Some projects require preliminary works, such as land preparation and levelling, demolition of existing structures (see below), or laying foundations, and there are circumstances where this work may be contracted for in advance of finalising the contract and costs for the whole project.

Typically, a construction site will include a secure perimeter to restrict unauthorised access, site access control points, office and welfare accommodation for personnel from the main contractor and other firms involved in the project team, and storage areas for materials, machinery and equipment. According to the McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Architecture and Construction's definition, construction may be said to have started when the first feature of the permanent structure has been put in place, such as pile driving, or the pouring of slabs or footings.[24]

Commissioning and handover

[edit]Commissioning is the process of verifying that all subsystems of a new building (or other assets) work as intended to achieve the owner's project requirements and as designed by the project's architects and engineers.

Defects liability period

[edit]A period after handover (or practical completion) during which the owner may identify any shortcomings in relation to the building specification ('defects'), with a view to the contractor correcting the defect.[25]

Maintenance, repair and improvement

[edit]Maintenance involves functional checks, servicing, repairing or replacing of necessary devices, equipment, machinery, building infrastructure, and supporting utilities in industrial, business, governmental, and residential installations.[26][27]

Demolition

[edit]Demolition is the discipline of safely and efficiently tearing down buildings and other artificial structures. Demolition contrasts with deconstruction, which involves taking a building apart while carefully preserving valuable elements for reuse purposes (recycling – see also circular economy).

Industry scale and characteristics

[edit]Economic activity

[edit]

The output of the global construction industry was worth an estimated $10.8 trillion in 2017, and in 2018 was forecast to rise to $12.9 trillion by 2022,[28] and to around $14.8 trillion in 2030.[1] As a sector, construction accounts for more than 10% of global GDP (in developed countries, construction comprises 6–9% of GDP),[29] and employs around 7% of the total employed workforce around the globe[30] (accounting for over 273 million full- and part-time jobs in 2014).[31] Since 2010,[32] China has been the world's largest single construction market.[33] The United States is the second largest construction market with a 2018 output of $1.581 trillion.[34]

- In the United States in February 2020, around $1.4 trillion worth of construction work was in progress, according to the Census Bureau, of which just over $1.0 trillion was for the private sector (split roughly 55:45% between residential and nonresidential); the remainder was public sector, predominantly for state and local government.[35]

- In Armenia, the construction sector experienced growth during the latter part of 2000s. Based on National Statistical Service, Armenia's construction sector generated approximately 20% of Armenia's GDP during the first and second quarters of 2007. In 2009, according to the World Bank, 30% of Armenia's economy was from construction sector.[36]

- In Vietnam, the construction industry plays an important role in the national economy.[37][38][39] The Vietnamese construction industry has been one of the fastest growing in the Asia-Pacific region in recent years.[40][41] The market was valued at nearly $60 billion in 2021.[42] In the first half of 2022, Vietnam's construction industry growth rate reached 5.59%.[42][43][44] In 2022, Vietnam's construction industry accounted for more than 6% of the country's GDP, equivalent to over 589.7 billion Vietnamese dong.[45][46] The industry of industry and construction accounts for 38.26% of Vietnam's GDP.[47][48][49] At the same time, the industry is one of the most attractive industries for foreign direct investment (FDI) in recent years.[50][51][52]

Construction is a major source of employment in most countries; high reliance on small businesses, and under-representation of women are common traits. For example:

- In the US, construction employed around 11.4m people in 2020, with a further 1.8m employed in architectural, engineering, and related professional services – equivalent to just over 8% of the total US workforce.[53] The construction workers were employed in over 843,000 organisations, of which 838,000 were privately held businesses.[54] In March 2016, 60.4% of construction workers were employed by businesses with fewer than 50 staff.[55] Women are substantially underrepresented (relative to their share of total employment), comprising 10.3% of the US construction workforce, and 25.9% of professional services workers, in 2019.[53]

- The United Kingdom construction sector contributed £117 billion (6%) to UK GDP in 2018, and in 2019 employed 2.4m workers (6.6% of all jobs). These worked either for 343,000 'registered' construction businesses, or for 'unregistered' businesses, typically self-employed contractors;[56] just over one million small/medium-sized businesses, mainly self-employed individuals, worked in the sector in 2019, comprising about 18% of all UK businesses.[57] Women comprised 12.5% of the UK construction workforce.[58]

According to McKinsey research, productivity growth per worker in construction has lagged behind many other industries across different countries including in the United States and in European countries. In the United States, construction productivity per worker has declined by half since the 1960s.[59]

Construction GVA by country

[edit]| Economy | Construction GVA in 2018 (billions in USD)

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (01) |

|||||||||

| (02) |

|||||||||

| (03) |

|||||||||

| (04) |

|||||||||

| (05) |

|||||||||

| (06) |

|||||||||

| (07) |

|||||||||

| (08) |

|||||||||

| (09) |

|||||||||

| (10) |

|||||||||

| (11) |

|||||||||

| (12) |

|||||||||

| (13) |

|||||||||

| (14) |

|||||||||

| (15) |

|||||||||

| (16) |

|||||||||

| (17) |

|||||||||

| (18) |

|||||||||

| (19) |

|||||||||

| (20) |

|||||||||

| (21) |

|||||||||

| (22) |

|||||||||

| (23) |

|||||||||

| (24) |

|||||||||

| (25) |

|||||||||

|

The twenty-five largest countries in the world by construction GVA (2018)[60] | |||||||||

Employment

[edit]

Some workers may be engaged in manual labour[61] as unskilled or semi-skilled workers; they may be skilled tradespeople; or they may be supervisory or managerial personnel. Under safety legislation in the United Kingdom, for example, construction workers are defined as people "who work for or under the control of a contractor on a construction site";[62] in Canada, this can include people whose work includes ensuring conformance with building codes and regulations, and those who supervise other workers.[63]

Laborers comprise a large grouping in most national construction industries. In the United States, for example, in May 2023, the construction sector employed just over 7.9 million people, of whom 859,000 were laborers, while 3.7 million were construction trades workers (including 603,000 carpenters, 559,000 electricians, 385,000 plumbers, and 321,000 equipment operators).[64] Like most business sectors, there is also substantial white-collar employment in construction - out of 7.9 million US construction sector workers, 681,000 were recorded by the United States Department of Labor in May 2023 as in 'office and administrative support occupations', 620,000 in 'management occupations' and 480,000 in 'business and financial operations occupations'.[64]

Large-scale construction requires collaboration across multiple disciplines. A project manager normally manages the budget on the job, and a construction manager, design engineer, construction engineer or architect supervises it. Those involved with the design and execution must consider zoning requirements and legal issues, environmental impact of the project, scheduling, budgeting and bidding, construction site safety, availability and transportation of building materials, logistics, and inconvenience to the public, including those caused by construction delays.

Some models and policy-making organisations promote the engagement of local labour in construction projects as a means of tackling social exclusion and addressing skill shortages. In the UK, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation reported in 2000 on 25 projects which had aimed to offer training and employment opportunities for locally based school leavers and unemployed people.[65] The Foundation published "a good practice resource book" in this regard at the same time.[66] Use of local labour and local materials were specified for the construction of the Danish Storebaelt bridge, but there were legal issues which were challenged in court and addressed by the European Court of Justice in 1993. The court held that a contract condition requiring use of local labour and local materials was incompatible with EU treaty principles.[67] Later UK guidance noted that social and employment clauses, where used, must be compatible with relevant EU regulation.[68] Employment of local labour was identified as one of several social issues which could potentially be incorporated in a sustainable procurement approach, although the interdepartmental Sustainable Procurement Group recognised that "there is far less scope to incorporate [such] social issues in public procurement than is the case with environmental issues".[69]

There are many routes to the different careers within the construction industry. There are three main tiers of construction workers based on educational background and training, which vary by country:

Unskilled and semi-skilled workers

[edit]Unskilled and semi-skilled workers provide general site labor, often have few or no construction qualifications, and may receive basic site training.

Skilled tradespeople

[edit]Skilled tradespeople have typically served apprenticeships (sometimes in labor unions) or received technical training; this group also includes on-site managers who possess extensive knowledge and experience in their craft or profession. Skilled manual occupations include carpenters, electricians, plumbers, ironworkers, heavy equipment operators and masons, as well as those involved in project management. In the UK these require further education qualifications, often in vocational subject areas, undertaken either directly after completing compulsory education or through "on the job" apprenticeships.[70]

Professional, technical or managerial personnel

[edit]Professional, technical and managerial personnel often have higher education qualifications, usually graduate degrees, and are trained to design and manage construction processes. These roles require more training as they demand greater technical knowledge, and involve more legal responsibility. Example roles (and qualification routes) include:

- Architect – Will usually have studied architecture to degree level, and then undertaken further study and gained professional experience. In many countries, the title of "architect" is protected by law, strictly limiting its use to qualified people.

- Civil engineer – Typically holds a degree in a related subject and may only be eligible for membership of a professional institution (such as the UK's ICE) following completion of additional training and experience. In some jurisdictions, a new university graduate must hold a master's degree to become chartered,[a] and persons with bachelor's degrees may become Incorporated Engineers.

- Building services engineer – May also be referred to as an "M&E" or "mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) engineer" and typically holds a degree in mechanical or electrical engineering.[a]

- Project manager – Typically holds a 4-year or greater higher education qualification, but are often also qualified in another field such as architecture, civil engineering or quantity surveying.

- Structural engineer – Typically holds a bachelor's or master's degree in structural engineering.[a]

- Quantity surveyor – Typically holds a bachelor's degree in quantity surveying. UK chartered status is gained from the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

Safety

[edit]

Construction is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world, incurring more occupational fatalities than any other sector in both the United States and in the European Union.[2][71] In the US in 2019, 1,061, or about 20%, of worker fatalities in private industry occurred in construction.[2] In 2017, more than a third of US construction fatalities (366 out of 971 total fatalities) were the result of falls;[72] in the UK, half of the average 36 fatalities per annum over a five-year period to 2021 were attributed to falls from height.[73] Proper safety equipment such as harnesses, hard hats and guardrails and procedures such as securing ladders and inspecting scaffolding can curtail the risk of occupational injuries in the construction industry.[74] Other major causes of fatalities in the construction industry include electrocution, transportation accidents, and trench cave-ins.[75]

Other safety risks for workers in construction include hearing loss due to high noise exposure, musculoskeletal injury, chemical exposure, and high levels of stress.[76] Besides that, the high turnover of workers in construction industry imposes a huge challenge of accomplishing the restructuring of work practices in individual workplaces or with individual workers.[citation needed] Construction has been identified by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as a priority industry sector in the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) to identify and provide intervention strategies regarding occupational health and safety issues.[77][78] A study conducted in 2022 found “significant effect of air pollution exposure on construction-related injuries and fatalities”, especially with the exposure of nitrogen dioxide.[79]

Sustainability

[edit]Sustainability is an aspect of "green building", defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as "the practice of creating structures and using processes that are environmentally responsible and resource-efficient throughout a building's life-cycle from siting to design, construction, operation, maintenance, renovation and deconstruction."[80]

Decarbonising construction

[edit]The construction industry may require transformation at pace and at scale if it is to successfully contribute to achieving the target set out in The Paris Agreement of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C above industrial levels.[81][82] The World Green Building Council has stated the buildings and infrastructure around the world can reach 40% less embodied carbon emissions but that this can only be achieved through urgent transformation.[83][84]

Conclusions from industry leaders have suggested that the net zero transformation is likely to be challenging for the construction industry, but it does present an opportunity. Action is demanded from governments, standards bodies, the construction sector, and the engineering profession to meet the decarbonising targets.[85]

In 2021, the National Engineering Policy Centre published its report Decarbonising Construction: Building a new net zero industry,[85] which outlined key areas to decarbonise the construction sector and the wider built environment. This report set out around 20 different recommendations to transform and decarbonise the construction sector, including recommendations for engineers, the construction industry and decision makers, plus outlined six-overarching ‘system levers’ where action taken now will result in rapid decarbonisation of the construction sector.[85] These levels are:

- Setting and stipulating progressive targets for carbon reduction

- Embedding quantitative whole-life carbon assessment into public procurement

- Increasing design efficiency, materials reuse and retrofit of buildings

- Improving whole-life carbon performance

- Improving skills for net zero

- Adopting a joined up, systems approach to decarbonisation across the construction sector and with other sectors

Progress is being made internationally to decarbonise the sector including improvements to sustainable procurement practice such as the CO2 performance ladder in the Netherlands and the Danish Partnership for Green Public Procurement.[86][87] There are also now demonstrations of applying the principles of circular economy practices in practice such as Circl, ABN AMRO's sustainable pavilion and the Brighton Waste House.[88][89][90]

Construction magazines

[edit]See also

[edit]- Agile construction – Management system in the construction industry

- Building material – Material which is used for construction purposes

- Civil engineering – Engineering discipline focused on physical infrastructure

- Commissioning (construction) – Process to ensure that all building systems perform according to the "Design Intent"

- Environmental impact of concrete

- Impervious surface – Artificial structures such as pavements covered with water-tight materials

- Index of construction articles

- Land degradation – Gradual destruction of land

- List of tallest structures

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- Modern methods of construction – Processes designed to improve upon traditional methods

- Outline of construction – Overview of and topical guide to construction

- Real estate development – Process that creates or renovates new or existing spaces

- Structural robustness – Ability of a structure to withstand physical strain

- Umarell – Bolognese slang term

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c In the UK, the Chartered Engineer qualification is controlled by the Engineering Council, and is often achieved through membership of the relevant professional institution (ICE, CIBSE, IStructE, etc).

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Global Construction Report 2030". GCP DBA. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "Commonly Used Statistics: Worker fatalities". Occupational Safety and Health Administration. United States Department of Labor. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Construction". Online Etymology Dictionary http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=construction accessed 3/6/2014

- ^ Knecht B. Fast-track construction becomes the norm. Architectural Record.

- ^ Chitkara, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Halpin, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "The Top 250", Engineering News-Record, September 1, 2014

- ^ "The Top 400" (PDF), Engineering News-Record, May 26, 2014

- ^ US Census Bureau,NAICS Search 2012 NAICS Definition, Sector 23 – Construction

- ^ US Department of Labor (OSHA), Division C: Construction

- ^ Proctor, J., What is a Compulsory Purchase Order?, Bidwells, published 10 June 2018, accessed 26 November 2023

- ^ Marshall, Duncan; Worthing, Derek (2006). The Construction of Houses (4th ed.). London: EG Books. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-08-097112-4.

- ^ "History and Heritage of Civil Engineering". ASCE. Archived from the original on 16 February 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- ^ "What is Civil Engineering". Institution of Civil Engineers. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Mosey, David (2019). Collaborative Construction Procurement and Improved Value. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119151913.

- ^ Willmott Dixon, Working in live environments, accessed 6 May 2023

- ^ Mason, Jim (2016). Construction Law: From Beginner to Practitioner. Routledge. ISBN 9781317391777.

- ^ Tabei, Sayed Mohammad Amin; Bagherpour, Morteza; Mahmoudi, Amin (2019-03-19). "Application of Fuzzy Modelling to Predict Construction Projects Cash Flow". Periodica Polytechnica Civil Engineering. doi:10.3311/ppci.13402. ISSN 1587-3773. S2CID 116421818.

- ^ "North County News – San Diego Union Tribune". www.nctimes.com.

- ^ "Global construction industry faces growing threat of economic crime". pwc. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ Alsever, Jennifer (December 2019). "Bots Start Building". Fortune (Paper). New York, New York: Fortune Media (USA) Corporation. p. 36. ISSN 0015-8259.

- ^ Cronin, Jeff (2005). "S. Carolina Court to Decide Legality of Design-Build Bids". Construction Equipment Guide. Archived from the original on 2006-10-19. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ^ Dynybyl, Vojtěch; Berka, Ondrej; Petr, Karel; Lopot, František; Dub, Martin (2015). The Latest Methods of Construction Design. Springer. ISBN 9783319227627.

- ^ McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Architecture and Construction, "Start of construction", accessed 8 September 2020

- ^ Designing Buildings Wiki, Defects liability period DLP, last updated 17 February 2022, accessed 16 May 2022

- ^ "Defense Logistics Agency". DLA.mil. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ "European Federation of National Maintenance Societies". EFNMS.org. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

All actions which have the objective of retaining or restoring an item in or to a state in which it can perform its required function. These include the combination of all technical and corresponding administrative, managerial, and supervision actions.

- ^ "Global construction set to rise to US$12.9 trillion by 2022, driven by Asia Pacific, Africa and the Middle East". Building Design and Construction. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Chitkara, K. K. (1998), Construction Project Management, New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill Education, p. 4, ISBN 9780074620625, retrieved May 16, 2015

- ^ "Global Construction: insights (26 May 2017)". Potensis. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Construction Sector Employment in Low-Income Countries: Size of the Sector". ICED. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Which countries are investing the most in construction?". PBC Today. 25 March 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Roumeliotis, Greg (3 March 2011). "Global construction growth to outpace GDP this decade – PwC". Reuters Economic News. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Global Construction Perspectives & Construction Economics (2019), Future of Consultancy: Global Export Strategy for UK Consultancy and Engineering, ACE, London.

- ^ Value of Construction Put in Place at a Glance. United States Census Bureau. Accessed: 29 April 2020. Also see Manufacturing & Construction Statistics for more information.

- ^ "Armenian Growth Still In Double Digits", Armenia Liberty (RFE/RL), September 20, 2007.

- ^ "Tầm quan trọng của ngành xây dựng đối với sự phát triển của Vùng kinh tế trọng điểm phía Nam". Tạp chí Kinh tế và Dự báo - Bộ Kế hoạch và Đầu tư (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Xây dựng là lĩnh vực quan trọng, mang tính chiến lược, có vai trò rất lớn trong phát triển kinh tế - xã hội". toquoc.vn (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Ngành Xây dựng - hành trình 60 năm phát triển". Cục giám định nhà nước về chất lượng công trình xây dựng (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Topic: Construction industry in Vietnam". Statista. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Kinh tế Việt Nam 2023: Nhiều điểm sáng nổi bật". Vietnam Business Forum – Liên đoàn Thương mại và Công nghiệp Việt Nam-Kinh tế - Thị trường. 2023-04-12. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b "The Growth of the Construction Industry in Vietnam". www.researchinvietnam.com. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Tốc độ tăng trưởng ngành xây dựng tăng 4,47% so với cùng kỳ". baochinhphu.vn (in Vietnamese). 2023-07-06. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "9 tháng năm 2022, ngành Xây dựng tăng trưởng 5%-5,6% so với cùng kỳ năm trước". Tạp chí Kinh tế và Dự báo - Bộ Kế hoạch và Đầu tư (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Topic: Construction industry in Vietnam". Statista. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Kinh tế Việt Nam năm 2022 và triển vọng năm 2023". www.mof.gov.vn. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ Hoàng, Hiếu (2022-02-12). "Chuyển nhà Hà Nội". kienvang.vn (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ Ngọc, Dương (2023-02-25). "Tăng trưởng GDP: Kết quả 2022, kỳ vọng 2023". Nhịp sống kinh tế Việt Nam & Thế giới (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Vietnam attracts over 39,100 FDI projects with registered capital of nearly 469 billion USD so far | Business | Vietnam+ (VietnamPlus)". VietnamPlus. 2024-01-15. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Đầu tư trực tiếp nước ngoài và vấn đề phát triển kinh tế - xã hội ở Việt Nam". mof.gov.vn. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Đầu tư trực tiếp nước ngoài vào lĩnh vực xây dựng và bất động sản - thực trạng và những vấn đề đặt ra - Tạp chí Cộng sản". tapchicongsan.org.vn. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b "Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey". US Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Industries at a glance: Construction: NAICS 23". US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- ^ "TED: The Economics Daily (March 3, 2017)". US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Rhodes, Chris (16 December 2019). Briefing Paper: Construction industry: statistics and policy. London: House of Commons Library.

- ^ Rhodes, Chris (16 December 2019). Briefing Paper: Business statistics. London: House of Commons Library.

- ^ "Construction industry just 12.5% women and 5.4% BAME". GMB Union. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "The construction industry's productivity problem". The Economist. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ^ Source: National Accounts Estimates of Main Aggregates | United Nations Statistics Division. Gross Value Added by Kind of Economic Activity at current prices – US dollars. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Construction worker definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- ^ "Are you a construction worker? Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015 (CDM 2015) – What you need to know". Health and Safety Executive. HSE. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Construction Worker – General". Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety. CCOHS. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b "May 2023 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates - Sector 23 - Construction". US Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Local labour in construction: tackling social exclusion and skill shortages, published November 2000, accessed 17 February 2024

- ^ Macfarlane, R., Using local labour in construction: A good practice resource book, The Policy Press/Joseph Rowntree Foundation, published 17 November 2000, accessed 17 February 2024

- ^ Heard, E., Evaluation and the audit trail, Bevan Brittan, published 8 June 2016, accessed 31 December 2023

- ^ Dawn Primarolo, Construction Industry: Treasury written question – answered at on 19 April 2004, TheyWorkForYou, accessed 29 April 2024

- ^ Sustainable Procurement Group, REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE SUSTAINABLE PROCUREMENT GROUP, January 2003, paragraph 8.4, accessed 29 April 2024

- ^ Wood, Hannah (17 January 2012). "UK Construction Careers, Certifications/Degrees and occupations". TH Services. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ "Health and safety at work statistics". eurostat. European Commission. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Garza, Elizabeth (10 April 2019). "Construction Fall Fatalities Still Highest Among All Industries: What more can we do? (April 10, 2019)". NIOSH Science blog. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Construction statistics in Great Britain, 2021" (PDF). HSE. Health & Safety Executive. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "OSHA's Fall Prevention Campaign". Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "The Construction Chart Book: The US Construction Industry and its Workers" (PDF). CPWR, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ^ Swanson, Naomi; Tisdale-Pardi, Julie; MacDonald, Leslie; Tiesman, Hope M. (13 May 2013). "Women's Health at Work". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "CDC – NIOSH Program Portfolio : Construction Program". www.cdc.gov. 2018-04-05. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- ^ "CDC – NIOSH – NORA Construction Sector Council". www.cdc.gov. 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- ^ "Air pollution increases the likelihood of accidents in construction sites". London School of Economics Business Review. 6 Sep 2023. Retrieved 15 Sep 2023.

- ^ "Basic Information | Green Building |US EPA". archive.epa.gov. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ "The Paris Agreement". United Nations.

- ^ Donati, Angelica Krystle (February 6, 2023). "Decarbonisation And The Green Transition In Construction: Logical, Cost-Effective, And Inevitable". Forbes.

- ^ "Bringing embodied carbon upfront". World Green Building Council.

- ^ "Bringing embodied carbon upfront" (PDF). World Green Building Council.

- ^ a b c "Decarbonising construction". National Engineering Policy Centre.

- ^ "What is the Ladder". The CO2 Performance Ladder.

- ^ "Strategy for green public procurement". Economy Agency of Denmark.

- ^ "The Forum on Sustainable Procurement". Ministry of Environment Denmark. Archived from the original on 2023-05-24. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ Chua, Geraldine (May 4, 2018). "Designing the Dutch way". Architecture & Design.

- ^ Wainwright, Oliver (7 July 2014). "The house that 20,000 toothbrushes built". The Guardian.

Construction

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Etymology

Origins and Evolution of the Term

The term "construction" originates from the Latin constructio, a noun of action derived from the verb construere, meaning "to pile up together" or "to build," combining the prefix com- ("together") with struere ("to pile up" or "arrange").[10] This root reflects an emphasis on assembling parts into a coherent whole, initially applied in classical Latin to both physical edifices and abstract compositions, such as rhetorical structures.[11] The word entered English in the late 14th century as construccioun, borrowed via Old French construction, initially denoting the act of interpreting or explaining texts before shifting to the physical process of building or joining elements by the early 15th century.[10] By 1707, it had evolved to describe the manner or form in which something is built, and by 1796, it referred to the resulting structure itself, marking a transition from process-oriented to outcome-focused usage.[10] This semantic broadening paralleled advancements in engineering and architecture during the Enlightenment, where precise terminology became essential for documenting increasingly complex projects like bridges and fortifications. In the 19th and 20th centuries, "construction" solidified as the standard term for organized building activities, encompassing not only manual assembly but also industrialized processes, legal contracts, and economic sectors, as evidenced by its integration into trade classifications following the rise of mechanized production and urbanization.[12] For instance, by the early 1900s, it denoted systematic workflows in large-scale infrastructure, distinguishing it from artisanal crafting, though the core idea of cumulative assembly persisted.[13] This evolution underscores a causal link between technological demands—such as steam-powered machinery and standardized materials—and the term's adaptation to describe scalable, project-based endeavors rather than ad hoc fabrication.Scope and Distinctions from Related Fields

Construction encompasses the physical processes of erecting, altering, or repairing structures and infrastructure through on-site assembly of materials, labor, and equipment, spanning activities from foundational excavation to finishing trades. The industry, as defined by the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Sector 23, includes three primary subsectors: building construction (e.g., residential and nonresidential structures), heavy and civil engineering construction (e.g., highways, dams, and utilities), and specialty trade contracting (e.g., electrical, plumbing, and masonry work).[14] [1] This scope applies to new work, additions, renovations, maintenance, and repairs, but excludes off-site fabrication of components like prefabricated modules, which are classified under manufacturing sectors (NAICS 31-33).[14] Globally, similar delineations appear in classifications like the European Union's NACE Section F, emphasizing site-based execution over design or material production. Key distinctions from architecture and engineering lie in construction's focus on implementation rather than ideation or analysis. Architecture prioritizes conceptual design, spatial aesthetics, and user experience, often culminating in drawings and specifications, whereas construction translates these into tangible outcomes via sequencing, procurement, and labor coordination.[15] Civil engineering, conversely, emphasizes technical computations for load-bearing, geotechnical stability, and system integration, providing blueprints that construction firms execute with adaptations for real-world variables like terrain or supply delays.[15] [16] These fields overlap in the architecture-engineering-construction (AEC) triad, but construction uniquely bears on-site risks, such as safety compliance under standards like OSHA regulations, which mandate hazard mitigation during assembly absent in upstream design phases.[16] In contrast to manufacturing, construction involves bespoke, location-dependent projects subject to environmental externalities, regulatory variances, and sequential dependencies, rather than repetitive, climate-controlled production of uniform goods.[1] Manufacturing optimizes for economies of scale in factories, producing modular elements like steel beams or HVAC units that construction then integrates on-site, but lacks the iterative problem-solving required for site-specific adaptations, such as foundation adjustments for uneven subsoil.[17] This demarcation underscores construction's higher variability in timelines and costs, with U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicating average project overruns tied to these on-site factors, distinguishing it from manufacturing's predictable throughput metrics.[1]Historical Development

Prehistoric and Ancient Construction

Prehistoric construction marked the earliest known efforts to erect monumental structures using available natural materials and rudimentary techniques, primarily by hunter-gatherer societies without evidence of metal tools or settled agriculture. Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, dating to approximately 9600 BCE, represents one of the oldest examples, featuring large circular enclosures with T-shaped limestone pillars, some weighing up to 20 tons and decorated with animal carvings.[18][19] These were quarried, shaped, and transported using stone tools and possibly wooden levers or rollers, with geometric planning evident in the layout of enclosures up to 20 meters in diameter.[20] The site's construction by pre-agricultural groups challenges assumptions about the sequence of social complexity, as it predates farming and suggests ritual or communal purposes drove large-scale labor organization.[21] In Neolithic Europe, megalithic structures emerged around 5000–3000 BCE, involving the erection of massive stone slabs (megaliths) for tombs, circles, or alignments. Stonehenge in England, constructed in phases from circa 3000 BCE, utilized sarsen stones up to 30 tons hauled from 25 kilometers away and bluestones from Wales, likely via sledges, rollers, and ropes over land and water.[22] These feats relied on leverage, earthen ramps, and community effort, with astronomical alignments indicating functional roles in calendars or ceremonies. Similar dolmens and passage tombs across Britain, Ireland, and continental Europe demonstrate widespread adoption of dry-stone stacking and corbeling techniques without mortar. Ancient construction advanced with the rise of urban civilizations, incorporating fired bricks, ramps, and organized labor for temples, tombs, and infrastructure. In Mesopotamia, Sumerians built ziggurats—stepped pyramidal platforms—as religious centers, with the earliest around 4000 BCE using sun-dried mud bricks cored with reeds for stability and coated in baked bricks. The Ziggurat of Ur, completed circa 2100 BCE by King Ur-Nammu, rose in three terraces to about 30 meters, accessed by ramps and supporting a temple atop for the moon god Nanna.[23] Construction emphasized flood-resistant foundations and bitumen waterproofing, reflecting adaptations to the Tigris-Euphrates environment. Egyptian pyramids epitomized precision engineering, with the Great Pyramid of Giza built for Pharaoh Khufu around 2580–2560 BCE using approximately 2.3 million limestone and granite blocks averaging 2.5 tons each, quarried locally and from Aswan. Blocks were transported via Nile barges and sledges lubricated with water to reduce friction, then raised using straight or spiraling ramps, levers, and possibly counterweight systems.[24] The structure's alignment to cardinal points within 3 arcminutes and casing stones polished for reflectivity highlight surveying skills with plumb bobs and sighting tools. In the Indus Valley, cities like Mohenjo-Daro (circa 2600 BCE) featured standardized baked-brick construction for multi-story homes, grid-planned streets, and the world's earliest known sanitation systems with covered drains and wells, built over 250 hectares using uniform bricks measuring 28x14x7 cm.[25] Classical Greek architecture emphasized post-and-lintel systems with marble, as in the Parthenon (447–432 BCE) on Athens' Acropolis, where Doric columns and entablatures were assembled using cranes, pulleys, and iron clamps, with optical refinements like column entasis to counter visual illusions. Roman innovations scaled these with concrete (opus caementicium) and arches for durability and span. Aqueducts, such as the Aqua Appia (312 BCE), channeled water over 16 kilometers using gravity-fed channels on piers and inverted siphons, constructed with precisely cut stone facing hydraulic lime mortar. The Colosseum (70–80 CE) employed layered arches, vaults, and travertine facing over concrete, accommodating 50,000 spectators via radial corridors and elevating mechanisms for spectacles. These methods enabled empire-wide infrastructure, prioritizing functionality and public utility through state-organized skilled labor.[26]Classical to Medieval Periods

In ancient Greece, construction primarily relied on post-and-lintel systems using stone blocks such as limestone and marble, with temples exemplifying Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders characterized by columns supporting horizontal beams.[27] The Parthenon, constructed between 447 and 432 BCE on the Athenian Acropolis, featured precisely cut Pentelic marble blocks lifted via levers, ropes, and possibly early cranes, achieving a peristyle of 46 outer columns for structural stability and aesthetic proportion.[28] Greek builders emphasized modular planning and optical refinements like entasis to counteract visual distortions, prioritizing harmony derived from geometric ratios over expansive engineering.[27] Roman construction advanced these foundations through innovations in materials and structural forms, notably the development of concrete (opus caementicium) around the 2nd century BCE by mixing volcanic ash (pozzolana), lime, and aggregates, enabling durable, moldable forms resistant to seawater and tension.[29] This facilitated widespread use of arches, vaults, and domes, as seen in the Colosseum (completed circa 80 CE), which employed layered concrete arches and vaults to span 188 meters in length while supporting 50,000 spectators via innovative load distribution.[30] The Pantheon, rebuilt under Emperor Hadrian around 126 CE, showcased a massive unreinforced concrete dome with an oculus, reaching 43.3 meters in diameter through graduated aggregate sizes for weight reduction and pozzolanic reactivity ensuring longevity.[29] Romans integrated arcuated (arch-based) and trabeated (post-lintel) elements for infrastructure like aqueducts and roads, with over 400,000 kilometers of roads constructed by the 2nd century CE, reflecting centralized imperial organization and empirical trial-and-error refinement.[31] Following the Western Roman Empire's collapse in the 5th century CE, construction techniques regressed in Europe due to disrupted supply chains, lost knowledge, and decentralized feudal structures, shifting from large-scale public works to localized fortifications and ecclesiastical buildings using salvaged Roman materials.[32] Early medieval efforts revived Romanesque styles from the 10th century, featuring thick stone walls, rounded arches, and barrel vaults for stability in structures like castles and basilicas, as evidenced by the Tower of London’s White Tower (completed circa 1100 CE) with its quoining and rubble core.[32] Labor relied on monastic workshops and emerging guilds, with treadwheel cranes hoisting stones up to 1 ton for heights exceeding 30 meters.[33] High Medieval construction peaked in Gothic cathedrals from the 12th century, introducing pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses to distribute weight outward, allowing thinner walls, larger windows, and heights over 30 meters, such as Chartres Cathedral (begun 1194 CE) spanning 130 meters in length with innovative skeletal framing.[32] These advances stemmed from empirical experimentation by master masons, using temporary wooden centering for vault erection and lime mortar for bonding ashlar masonry, enabling rapid builds like Notre-Dame de Paris (1163–1345 CE) amid feudal patronage and pilgrimage economies.[34] Castles evolved from motte-and-bailey earthworks to concentric stone designs, like Bodiam Castle (1385 CE), incorporating moats and battlements for defense via compartmentalized construction phases.[32] Overall, medieval methods prioritized verticality and light through causal adaptations to stone's compressive strength, contrasting Roman massiveness, though reliant on manual scaffolding and seasonal labor without Roman concrete's scalability.[34]Industrial Revolution Transformations

The Industrial Revolution, originating in Britain during the late 18th century, marked a pivotal shift in construction from labor-intensive, site-specific craftsmanship to mechanized processes enabled by coal-fired steam engines and mass-produced materials. This era saw the widespread adoption of cast iron for structural components, such as columns and girders, due to advances in smelting and casting techniques that allowed for prefabricated elements capable of supporting greater loads over wider spans than traditional timber or stone.[35][36] Cast iron's compressive strength facilitated innovations like the Iron Bridge completed in 1779 over the River Severn, the first major structure cast entirely from iron, demonstrating the material's potential for arched spans exceeding 100 feet.[37] A key material breakthrough was the development of Portland cement, patented by British bricklayer Joseph Aspdin on October 21, 1824, after heating a mixture of limestone and clay to produce a hydraulic binder that set underwater and achieved greater durability than earlier limes.[38][39] This innovation enabled reliable concrete for foundations, canals, and harbors, reducing reliance on skilled masons and accelerating large-scale projects; by the 1830s, Portland cement production scaled commercially, supporting the era's infrastructure demands.[40] Infrastructure construction boomed with the railway mania, as steam locomotives necessitated extensive earthworks, bridges, and tunnels; the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, authorized in 1826 and opened in 1830 as Britain's first purpose-built passenger line, exemplified this, requiring 60 miles of track, viaducts, and cuttings that employed thousands in coordinated labor.[41] By the 1840s, speculative investments drove rapid expansion, with railway projects contributing to structural divergences in regional economies through population and employment growth rates increased by approximately 0.87% annually in connected areas from 1851 to 1891.[42] Steam power directly influenced on-site techniques by powering nascent machinery, such as pile drivers and dredgers, which mechanized excavation and foundation work previously done manually, though adoption lagged behind factory applications until the mid-19th century.[43] These changes scaled construction output, enabling urbanization via factories and worker housing, but often at the cost of hazardous conditions for unskilled laborers drawn from rural areas.[44]20th Century Mass Construction

The 20th century marked a shift toward industrialized mass construction, driven by advancements in materials like reinforced concrete and steel framing, which enabled large-scale urban and infrastructure projects. In the United States, the 1920s saw a skyscraper boom in cities like New York, where developers constructed numerous high-rises to accommodate growing commercial demands, with over 740,000 housing units built in New York alone from 1920 to 1929. This era's vertical expansion relied on innovations such as elevators and fireproof steel skeletons, exemplified by the completion of the Empire State Building in 1931 after a 410-day construction period that employed up to 3,400 workers daily.[45][46] During the Great Depression, government-funded mega-projects exemplified mass construction's role in employment and infrastructure. The Hoover Dam, initiated on July 7, 1930, and completed in 1936, involved over 21,000 workers pouring approximately 3.25 million cubic yards of concrete, transforming the Colorado River for flood control, irrigation, and power generation. Similar efforts, including the Shasta Dam started in 1938, highlighted the scale of civil engineering feats that employed thousands and utilized novel techniques like refrigerated concrete blocks to manage heat from mass pours. These projects not only addressed economic crises but also standardized construction processes for efficiency.[47][48] Post-World War II housing shortages spurred global mass production techniques, including prefabrication and modular assembly, to rapidly build suburbs and urban apartments. In the US, the 1950s boom saw tract developments like Levittown, New York, where standardized designs and materials such as plywood and composition board cut costs and enabled builders to construct homes at rates exceeding 30 per day. In the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev's 1950s-1960s program produced millions of low-cost "Khrushchevka" five-story panel buildings using prefabricated concrete, addressing acute shortages by prioritizing speed and volume over durability, with over 300 million square meters of housing added by the 1980s. These efforts reflected a causal emphasis on assembly-line methods to meet demographic pressures, though quality trade-offs emerged in rapid urbanization.[49][50][51]21st Century Globalization and Innovation

The global construction industry experienced significant expansion in the 21st century, driven by rapid urbanization and infrastructure development in emerging markets. The market size grew from approximately $10.2 trillion in 2020 to projections of $15.2 trillion by 2030, with much of the increase attributable to countries like China, India, the United States, and Indonesia, which accounted for 58.3% of global growth between 2020 and 2030.[52] In China, state-led investments in high-speed rail and urban projects exemplified this trend, constructing over 40,000 kilometers of high-speed rail by 2023, surpassing combined lengths in other nations.[53] India's construction sector, meanwhile, expanded at nearly twice the rate of China's, fueled by government initiatives like the Smart Cities Mission launched in 2015, which aimed to develop 100 sustainable urban areas.[54] Globalization facilitated cross-border collaborations and supply chain integration, enabling multinational firms to execute mega-projects in diverse regions. For instance, China's Belt and Road Initiative, initiated in 2013, spurred overseas construction contracts exceeding $1 trillion by 2023, linking infrastructure development across Asia, Africa, and Europe.[55] This interconnectedness, however, exposed the industry to risks such as supply chain disruptions, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 onward, which delayed projects worldwide due to material shortages and labor mobility restrictions.[7] Emerging markets' dominance shifted economic power dynamics, with Asia-Pacific regions projected to represent over 45% of global construction output by 2025.[56] Technological innovations transformed construction processes, enhancing efficiency and addressing labor shortages. Building Information Modeling (BIM), standardized in the early 2000s, enabled digital representations of projects, reducing errors by up to 20% in complex builds through collaborative 3D modeling.[57] Modular construction gained traction post-2010, with prefabricated components assembled on-site, cutting build times by 50% in projects like high-rise housing in Singapore.[58] 3D printing emerged as a disruptive method, with the first multi-story concrete-printed building completed in Dubai in 2019 using robotic extrusion techniques.[59] Automation and AI further revolutionized on-site operations, with drones deployed for surveying since the mid-2010s, improving accuracy and safety in inspections.[60] Robotics, including bricklaying machines introduced around 2015, mitigated skilled labor deficits, projected to affect 2.1 million U.S. jobs by 2025.[61] Sustainability innovations, such as low-carbon materials and renewable-integrated designs, aligned with regulatory pressures like the European Green Deal of 2019, aiming for net-zero buildings by 2050.[62] These advancements, while promising productivity gains of 50-60% by 2025 per industry analyses, faced adoption barriers in developing regions due to high initial costs.[63]Industry Sectors

Building Construction

Building construction encompasses the erection, alteration, and renovation of structures primarily designed for human occupancy, including residential homes, commercial offices, retail spaces, and institutional facilities such as schools and hospitals.[64] This sector focuses on enclosed buildings that provide shelter and functional interiors, distinguishing it from infrastructure construction, which involves non-enclosed public works like roads, bridges, and utilities systems essential for connectivity but not direct habitation.[65] Unlike heavy industrial construction, building projects emphasize occupant safety, interior fit-outs, and compliance with zoning and building codes tailored to end-user needs.[66] The global buildings construction market was valued at approximately $7.3 trillion in 2024, projected to reach $7.6 trillion in 2025, driven by urbanization, population growth, and demand for housing and commercial spaces in emerging economies.[67] In the United States, the broader construction sector, with building activities comprising a significant portion, reached nearly $2 trillion in output in 2023, reflecting steady growth amid residential and non-residential demand.[68] Key subtypes include residential construction, which accounted for a substantial share of activity in 2024 due to housing shortages in many regions; commercial, involving office and retail developments; and institutional, focused on public and educational buildings.[69] [64] Employment in the construction industry, including building construction, supports around 174 million jobs worldwide as of 2021, with building projects often requiring skilled trades like carpentry, masonry, and electrical work alongside general labor.[70] In 2024, trends such as modular prefabrication gained traction to address labor shortages and reduce on-site time, with prefabricated components enabling up to 20-50% faster assembly in some projects, though adoption varies by regulatory environments.[71] Digital tools like Building Information Modeling (BIM) have become standard for coordinating complex designs, improving accuracy and minimizing errors, as evidenced by widespread implementation in large-scale commercial builds.[72] Material innovations, including high-strength concrete and cross-laminated timber, support taller and more efficient structures while meeting seismic and fire safety standards.[73]Infrastructure and Civil Works

Infrastructure and civil works encompass the construction of large-scale public facilities essential for transportation, utilities, and resource management, including roads, bridges, tunnels, railways, dams, airports, water supply systems, and sewage networks.[74][75] These projects prioritize durability, public accessibility, and integration with natural environments over aesthetic or private-use features typical of building construction.[76] Civil works often involve geotechnical engineering to address soil stability, hydrology for water flow management, and structural design to withstand environmental loads like earthquakes or floods.[77] Major examples include the Itaipu Dam on the Brazil-Paraguay border, which generates over 100 billion kWh annually and required 12.6 million cubic meters of concrete, and the High Speed 2 (HS2) railway in the United Kingdom, spanning 225 miles with tunneling through challenging geology.[78][78] Such endeavors facilitate economic connectivity, with infrastructure enabling trade and mobility; for instance, highways and ports reduce logistics costs by up to 20% in developed networks.[79] Government funding predominates, supplemented by public-private partnerships to mitigate fiscal burdens, though these introduce risks of agency conflicts in procurement and oversight.[80] Challenges persist in execution, including labor shortages affecting 80% of projects, material cost volatility exceeding 10% annually in recent years, and regulatory delays from environmental assessments that can extend timelines by 25%.[72][81] Safety incidents remain elevated due to heavy machinery and remote sites, with productivity lagging 30-50% behind manufacturing benchmarks owing to fragmented workflows.[82] Addressing these requires advanced technologies like BIM for design optimization and modular prefabrication to cut on-site time, yet adoption varies by region due to upfront costs and skill gaps.[17] Global investment needs for resilient infrastructure are estimated at $106 trillion through 2040 to counter aging assets and climate pressures.[83]Industrial and Heavy Construction

Industrial and heavy construction refers to the development of large-scale facilities designed for manufacturing, energy generation, resource extraction, and processing operations, such as factories, power plants, refineries, chemical processing units, and mining infrastructure. These projects differ from building construction by emphasizing functional process integration over occupant comfort and from civil infrastructure by prioritizing specialized industrial equipment installation rather than public utilities like roads or bridges. Typical scopes include foundation systems capable of supporting massive loads, extensive piping networks for fluids and gases, and electrical systems for heavy machinery operation.[64][84][85] Key processes in this sector involve site preparation with heavy earthmoving equipment, modular prefabrication to minimize on-site assembly risks, and commissioning phases for testing integrated systems. Projects often require multidisciplinary engineering teams to handle seismic design, corrosion-resistant materials, and compliance with stringent environmental and safety regulations, such as those from the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) mandating hazard assessments for confined spaces and elevated work. Challenges include skilled labor shortages, with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting a need for over 500,000 additional construction workers annually through 2025, exacerbated by the technical demands of welding, rigging, and process engineering; supply chain disruptions for specialized steel and alloys; and rising costs from regulatory delays, as seen in permitting timelines averaging 2-3 years for major facilities.[86][87][88] Economically, heavy engineering construction in the United States generated $49.2 billion in revenue in 2025, growing at a compound annual rate of 5.2% over the prior five years, driven by investments in energy transition projects like liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and renewable power installations. Notable recent examples include the Port Arthur LNG facility in Texas, a $10 billion project under construction since 2022 to export 13.5 million tonnes of LNG annually, highlighting the sector's role in global energy supply chains despite environmental permitting hurdles. Internationally, facilities like the Dholera Solar Power Plant in India exemplify heavy construction's adaptation to sustainable technologies, with capacities targeting gigawatt-scale output by 2030. These undertakings underscore causal factors like resource demand and technological mandates propelling sector growth amid persistent risks of overruns, where projects frequently exceed budgets by 20-30% due to unforeseen geotechnical issues or material price volatility.[89][90][91]Core Processes

Planning and Design Phases