Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geography of Chad

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2019) |

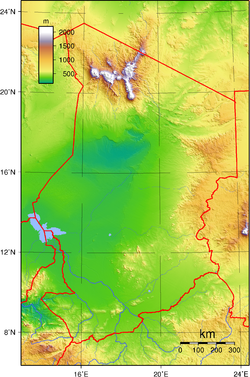

Chad is one of the 47 landlocked countries in the world and is located in North Central Africa, measuring 1,284,000 square kilometers (495,755 sq mi), nearly twice the size of France and slightly more than three times the size of California. Most of its ethnically and linguistically diverse population lives in the south, with densities ranging from 54 persons per square kilometer in the Logone River basin to 0.1 persons in the northern B.E.T. (Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti) desert region, which itself is larger than France. The capital city of N'Djaména, situated at the confluence of the Chari and Logone Rivers, is cosmopolitan in nature, with a current population in excess of 700,000 people.

Chad has four climatic zones. The northernmost Saharan zone averages less than 200 mm (7.9 in) of rainfall annually. The sparse human population is largely nomadic, with some livestock, mostly small ruminants and camels. The central Sahelian zone receives between 200 and 700 mm (7.9 and 27.6 in) rainfall and has vegetation ranging from grass/shrub steppe to thorny, open savanna. The southern zone, often referred to as the Sudan zone, receives between 700 and 1,000 mm (27.6 and 39.4 in), with woodland savanna and deciduous forests for vegetation. Rainfall in the Guinea zone, located in Chad's southwestern tip, ranges between 1,000 and 1,200 mm (39.4 and 47.2 in). In Chad forest cover is around 3% of the total land area, equivalent to 4,313,000 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, down from 6,730,000 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 4,293,000 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 19,800 hectares (ha). For the year 2015, 100% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership.[1][2]

The country's topography is generally flat,[3] with the elevation gradually rising as one moves north and east away from Lake Chad. The highest point in Chad is Emi Koussi, a mountain that rises 3,100 m (10,171 ft) in the northern Tibesti Mountains. The Ennedi Plateau and the Ouaddaï highlands in the east complete the image of a gradually sloping basin, which descends towards Lake Chad. There are also central highlands in the Guera region rising to 1,500 m (4,921 ft).

Lake Chad is the second largest lake in west Africa[4] and is one of the most important wetlands on the continent.[5] Home to 120 species of fish and at least that many species of birds, the lake has shrunk dramatically in the last four decades due to increased water usage from an expanding population and low rainfall. Bordered by Chad, Niger, Nigeria, and Cameroon, Lake Chad currently covers only 1,350 square kilometers, down from 25,000 square kilometers in 1963. The Chari and Logone Rivers, both of which originate in the Central African Republic and flow northward, provide most of the surface water entering Lake Chad. Chad is also next to Niger.

Geographical placement

[edit]

Located in north-central Africa, Chad stretches for about 1,800 kilometers from its northernmost point to its southern boundary.[6] Except in the far northwest and south, where its borders converge, Chad's average width is about 800 kilometers.[6] Its area of 1,284,000 square kilometers is roughly equal to the combined areas of Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and Arizona.[6] Chad's neighbors include Libya to the north, Niger and Nigeria to the west, Sudan to the east, Central African Republic to the south, and Cameroon to the southwest.[6]

Chad exhibits two striking geographical characteristics.[6] First, the country is landlocked.[6] N'Djamena, the capital, is located more than 1,100 kilometers northeast of the Atlantic Ocean; Abéché, a major city in the east, lies 2,650 kilometers from the Red Sea; and Faya-Largeau, a much smaller but strategically important center in the north, is in the middle of the Sahara Desert, 1,550 kilometers from the Mediterranean Sea.[6] These vast distances from the sea have had a profound impact on Chad's historical and contemporary development.[6]

The second noteworthy characteristic is that the country borders on very different parts of the African continent: North Africa, with its Islamic culture and economic orientation toward the Mediterranean Basin; and West Africa, with its diverse religions and cultures and its history of highly developed states and regional economies.[6]

Chad also borders Northeast Africa, oriented toward the Nile Valley and the Red Sea region - and Central or Equatorial Africa, some of whose people have retained classical African religions while others have adopted Christianity, and whose economies were part of the great Congo River system.[6] Although much of Chad's distinctiveness comes from this diversity of influences, since independence the diversity has also been an obstacle to the creation of a national identity.[6]

Land

[edit]Although Chadian society is economically, socially, and culturally fragmented, the country's geography is unified by the Lake Chad Basin.[6] Once a huge inland sea (the Pale-Chadian Sea) whose only remnant is shallow Lake Chad, this vast depression extends west into Nigeria and Niger.[6] The larger, northern portion of the basin is bounded within Chad by the Tibesti Mountains in the northwest, the Ennedi Plateau in the northeast, the Ouaddaï Highlands in the east along the border with Sudan, the Guéra Massif in central Chad, and the Mandara Mountains along Chad's southwestern border with Cameroon.[6] The smaller, southern part of the basin falls almost exclusively in Chad.[6] It is delimited in the north by the Guéra Massif, in the south by highlands 250 kilometers south of the border with Central African Republic, and in the southwest by the Mandara Mountains.[6]

Lake Chad, located in the southwestern part of the basin at an altitude of 282 meters, surprisingly does not mark the basin's lowest point; instead, this is found in the Bodele and Djourab regions in the north-central and northeastern parts of the country, respectively.[6] This oddity arises because the great stationary dunes (ergs) of the Kanem region create a dam, preventing lake waters from flowing to the basin's lowest point.[6] At various times in the past, and as late as the 1870s, the Bahr el Ghazal Depression, which extends from the northeastern part of the lake to the Djourab, acted as an overflow canal; since independence, climatic conditions have made overflows impossible.[6]

North and northeast of Lake Chad, the basin extends for more than 800 kilometers, passing through regions characterized by great rolling dunes separated by very deep depressions.[6] Although vegetation holds the dunes in place in the Kanem region, farther north they are bare and have a fluid, rippling character.[6] From its low point in the Djourab, the basin then rises to the plateaus and peaks of the Tibesti Mountains in the north.[6] The summit of this formation—as well as the highest point in the Sahara Desert—is Emi Koussi, a dormant volcano that reaches 3,414 meters above sea level.[6]

The basin's northeastern limit is the Ennedi Plateau, whose limestone bed rises in steps etched by erosion.[6] East of the lake, the basin rises gradually to the Ouaddaï Highlands, which mark Chad's eastern border and also divide the Chad and Nile watersheds.[6] These highland areas are part of the East Saharan montane xeric woodlands ecoregion.

Southeast of Lake Chad, the regular contours of the terrain are broken by the Guéra Massif, which divides the basin into its northern and southern parts.[6] South of the lake lie the floodplains of the Chari and Logone rivers, much of which are inundated during the rainy season.[6] Farther south, the basin floor slopes upward, forming a series of low sand and clay plateaus, called koros, which eventually climb to 615 meters above sea level.[6] South of the Chadian border, the koros divide the Lake Chad Basin from the Ubangi-Zaire river system.[6]

Water systems

[edit]

Permanent streams do not exist in northern or central Chad.[6] Following infrequent rains in the Ennedi Plateau and Ouaddaï Highlands, water may flow through depressions called enneris and wadis.[6] Often the result of flash floods, such streams usually dry out within a few days as the remaining puddles seep into the sandy clay soil.[6] The most important of these streams is the Batha, which in the rainy season carries water west from the Ouaddaï Highlands and the Guéra Massif to Lake Fitri.[6]

Chad's major rivers are the Chari and the Logone and their tributaries, which flow from the southeast into Lake Chad.[6] Both river systems rise in the highlands of Central African Republic and Cameroon, regions that receive more than 1,250 millimeters of rainfall annually.[6] Fed by rivers of Central African Republic, as well as by the Bahr Salamat, Bahr Aouk, and Bahr Sara rivers of southeastern Chad, the Chari River is about 1,200 kilometers long.[6] From its origins near the city of Sarh, the middle course of the Chari makes its way through swampy terrain; the lower Chari is joined by the Logone River near N'Djamena.[6] The Chari's volume varies greatly, from 17 cubic meters per second during the dry season to 340 cubic meters per second during the wettest part of the year.[6]

The Logone River is formed by tributaries flowing from Cameroon and Central African Republic.[6] Both shorter and smaller in volume than the Chari, it flows northeast for 960 kilometers; its volume ranges from five to eighty-five cubic meters per second.[6] At N'Djamena the Logone empties into the Chari, and the combined rivers flow together for thirty kilometers through a large delta and into Lake Chad.[6] At the end of the rainy season in the fall, the river overflows its banks and creates a huge floodplain in the delta.[6]

The seventh largest lake in the world (and the fourth largest in Africa), Lake Chad is located in the sahelian zone, a region just south of the Sahara Desert.[6] The Chari River contributes 95 percent of Lake Chad's water, an average annual volume of 40 billion cubic meters, 95% of which is lost to evaporation.[6] The size of the lake is determined by rains in the southern highlands bordering the basin and by temperatures in the Sahel.[6] Fluctuations in both cause the lake to change dramatically in size, from 9,800 square kilometers in the dry season to 25,500 at the end of the rainy season.[6]

Lake Chad also changes greatly in size from one year to another.[6] In 1870 its maximum area was 28,000 square kilometers.[6] The measurement dropped to 12,700 in 1908.[6] In the 1940s and 1950s, the lake remained small, but it grew again to 26,000 square kilometers in 1963.[6] The droughts of the late 1960s, early 1970s, and mid-1980s caused Lake Chad to shrink once again, however.[6] The only other lakes of importance in Chad are Lake Fitri, in Batha Prefecture, and Lake Iro, in the marshy southeast.[6]

Climate

[edit]

The Lake Chad Basin embraces a great range of tropical climates from north to south, although most of these climates tend to be dry.[6] Apart from the far north, most regions are characterized by a cycle of alternating rainy and dry seasons.[6] In any given year, the duration of each season is determined largely by the positions of two great air masses—a maritime mass over the Atlantic Ocean to the southwest and a much drier continental mass.[6]

During the rainy season, winds from the southwest push the moister maritime system north over the African continent where it meets and slips under the continental mass along a front called the "intertropical convergence zone".[6] At the height of the rainy season, the front may reach as far as Kanem Prefecture.[6] By the middle of the dry season, the intertropical convergence zone moves south of Chad, taking the rain with it.[6] This weather system contributes to the formation of three major regions of climate and vegetation.[6]

Saharan region

[edit]

The Saharan region covers roughly the northern half of the country, including Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Prefecture along with the northern parts of Kanem, Batha, and Biltine prefectures.[6] Much of this area receives only traces of rain during the entire year; at Faya-Largeau, for example, annual rainfall averages less than 12 millimeters (0.47 in), and there are nearly 3800 hours of sunshine.[6] Scattered small oases and occasional wells provide water for a few date palms or small plots of millet and garden crops.[6]

In much of the north, the average daily maximum temperature is about 32 °C (89.6 °F) during January, the coolest month of the year, and about 45 °C (113 °F) during May, the hottest month.[6] On occasion, strong winds from the northeast produce violent sandstorms.[6] In northern Biltine Prefecture, a region called the Mortcha plays a major role in animal husbandry.[6] Dry for eight months of the year, it receives 350 millimeters (13.8 in) or more of rain, mostly during July and August.[6]

A carpet of green springs from the desert during this brief wet season, attracting herders from throughout the region who come to pasture their cattle and camels.[6] Because very few wells and springs have water throughout the year, the herders leave with the end of the rains, turning over the land to the antelopes, gazelles, and ostriches that can survive with little groundwater.[6] Northern Chad averages over 3500 hours of sunlight per year, the south somewhat less.

| Climate data for Faya-Largeau (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 39 (102) |

43 (109) |

44 (111) |

49 (120) |

49 (120) |

49 (120) |

47 (117) |

46 (115) |

46 (115) |

47 (117) |

39 (102) |

36 (97) |

49 (120) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.4 (79.5) |

29.4 (84.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

39.1 (102.4) |

41.0 (105.8) |

42.1 (107.8) |

41.0 (105.8) |

40.2 (104.4) |

39.8 (103.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

31.1 (88.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

35.7 (96.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

30.8 (87.4) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.6 (56.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4 (39) |

7 (45) |

11 (52) |

14 (57) |

17 (63) |

17 (63) |

16 (61) |

16 (61) |

17 (63) |

12 (54) |

9 (48) |

3 (37) |

3 (37) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.3 (0.01) |

3.0 (0.12) |

7.0 (0.28) |

0.8 (0.03) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

11.7 (0.46) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 25 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 20 | 27 | 33 | 22 | 25 | 23 | 25 | 23 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 306.9 | 291.2 | 306.9 | 309.0 | 344.1 | 333.0 | 334.8 | 319.3 | 312.0 | 319.3 | 309.0 | 306.9 | 3,792.4 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 9.9 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 9.9 | 10.4 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization (temperatures and precipitation days)[7] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun and humidity),[8] Annales de Géographie[9][10] | |||||||||||||

Sahelian region

[edit]The semiarid sahelian zone, or Sahel, forms a belt about 500 kilometers (311 mi) wide that runs from Lac and Chari-Baguirmi prefectures eastward through Guéra, Ouaddaï, and northern Salamat prefectures to the Sudanese frontier.[6] The climate in this transition zone between the desert and the southern sudanian zone is divided into a rainy season (from June to September) and a dry period (from October to May).[6]

In the northern Sahel, thorny shrubs and acacia trees grow wild, while date palms, cereals, and garden crops are raised in scattered oases.[6] Outside these settlements, nomads tend their flocks during the rainy season, moving southward as forage and surface water disappear with the onset of the dry part of the year.[6] The central Sahel is characterized by drought-resistant grasses and small woods.[6] Rainfall is more abundant there than in the Saharan region.[6] For example, N'Djamena records a maximum annual average rainfall of 580 millimeters (22.8 in), while Ouaddaï Prefecture receives just a bit less.[6]

During the hot season, in April and May, maximum temperatures frequently rise above 40 °C (104 °F).[6] In the southern part of the Sahel, rainfall is sufficient to permit crop production on unirrigated land, and millet and sorghum are grown.[6] Agriculture is also common in the marshlands east of Lake Chad and near swamps or wells.[6] Many farmers in the region combine subsistence agriculture with the raising of cattle, sheep, goats, and poultry.[6]

| Climate data for N'Djamena (1961-1990, extremes 1904-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 41.8 (107.2) |

47.6 (117.7) |

46.5 (115.7) |

48.3 (118.9) |

49.1 (120.4) |

44.0 (111.2) |

46.0 (114.8) |

38.6 (101.5) |

40.5 (104.9) |

43.6 (110.5) |

47.5 (117.5) |

40.5 (104.9) |

49.1 (120.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 32.4 (90.3) |

35.2 (95.4) |

38.7 (101.7) |

41.0 (105.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

37.2 (99.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

33.7 (92.7) |

36.9 (98.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

33.5 (92.3) |

35.8 (96.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.4 (74.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

29.9 (85.8) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.9 (91.2) |

30.9 (87.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

29.4 (84.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

28.3 (83.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.8 (76.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

24.7 (76.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.8 (58.6) |

20.8 (69.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.1 (59.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

10.3 (0.41) |

25.8 (1.02) |

51.0 (2.01) |

143.8 (5.66) |

174.4 (6.87) |

84.3 (3.32) |

20.3 (0.80) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

510.3 (20.1) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 60 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 29 | 23 | 21 | 28 | 39 | 52 | 68 | 76 | 72 | 49 | 33 | 31 | 43 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 297.6 | 277.2 | 282.1 | 273.0 | 285.2 | 258.0 | 213.9 | 201.5 | 228.0 | 285.2 | 300.0 | 303.8 | 3,205.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 9.6 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 9.2 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 8.8 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization (precipitation)[11] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, humidity, temperatures),[12] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[13] | |||||||||||||

Sudanian region

[edit]The humid sudanian zone includes the Sahel,[14] the southern prefectures of Mayo-Kebbi, Tandjilé, Logone Occidental, Logone Oriental, Moyen-Chari, and southern Salamat.[6] Between April and October, the rainy season brings between 750 and 1,250 millimeters (29.5 and 49.2 in) of precipitation.[6] Temperatures are high throughout the year.[6] Daytime readings in Moundou, the major city in the southwest, range from 27 °C (80.6 °F) in the middle of the cool season in January to about 40 °C (104 °F) in the hot months of March, April, and May.[6]

The sudanian region is predominantly East Sudanian savanna, or plains covered with a mixture of tropical or subtropical grasses and woodlands.[6] The growth is lush during the rainy season but turns brown and dormant during the five-month dry season between November and March.[6] Over a large part of the region, however, natural vegetation has yielded to agriculture.

| Climate data for Sarh (1961-1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 35.8 (96.4) |

38.0 (100.4) |

39.1 (102.4) |

38.5 (101.3) |

36.2 (97.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

33.6 (92.5) |

35.5 (95.9) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.9 (94.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.1 (0.00) |

1.6 (0.06) |

9.5 (0.37) |

37.4 (1.47) |

82.1 (3.23) |

135.9 (5.35) |

234.4 (9.23) |

243.7 (9.59) |

165.5 (6.52) |

55.8 (2.20) |

3.3 (0.13) |

0.0 (0.0) |

969.3 (38.16) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 16 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 86 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 33 | 29 | 37 | 50 | 61 | 72 | 79 | 82 | 80 | 73 | 57 | 42 | 58 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 266.6 | 243.6 | 244.9 | 237.0 | 241.8 | 207.0 | 173.6 | 176.7 | 186.0 | 232.5 | 261.0 | 266.6 | 2,737.3 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.6 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 8.7 | 8.6 | 7.5 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization (temperatures and rainy days)[15] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, humidity and precipitation)[16] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Moundou (1961-1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 34.1 (93.4) |

36.7 (98.1) |

38.6 (101.5) |

38.0 (100.4) |

35.7 (96.3) |

32.3 (90.1) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

33.1 (91.6) |

35.1 (95.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.01) |

4.6 (0.18) |

39.2 (1.54) |

89.8 (3.54) |

147.7 (5.81) |

257.8 (10.15) |

284.8 (11.21) |

200.1 (7.88) |

57.1 (2.25) |

1.5 (0.06) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1,082.8 (42.63) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 19 | 13 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 85 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 36 | 28 | 31 | 50 | 63 | 73 | 80 | 81 | 78 | 73 | 56 | 45 | 58 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 279.0 | 249.2 | 248.0 | 234.0 | 241.8 | 210.0 | 182.9 | 170.5 | 186.0 | 235.6 | 282.0 | 291.4 | 2,810.4 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 9.0 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 7.7 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun and humidity)[18] | |||||||||||||

2010 drought

[edit]On 22 June, the temperature reached 47.6 °C (117.7 °F) in Faya, breaking a record set in 1961 at the same location. Similar temperature rises were also reported in Niger, which began to enter a famine situation.[19]

On 26 July the heat reached near-record levels over Chad and Niger.[20]

Area

[edit]Area:

total:

1.284 million km2

land:

1,259,200 km2

water:

24,800 km2

Area — comparative:

- Canada: slightly less than twice the size of Alberta

- US: slightly more than three times the size of California

- Australia: slightly smaller than the Northern Territory

Boundaries

[edit]Land boundaries:

total:

6,406 km

border countries:

Cameroon 1,116 km, Central African Republic 1,556 km, Libya 1,050 km, Niger 1,196 km, Nigeria 85 km, Sudan 1,403 km

Coastline: 0 km (landlocked)

Maritime claims: none (landlocked)

Elevation extremes:

lowest point:

Bodélé Depression 160 m[21]

highest point:

Emi Koussi 3,415 m[22]

Land use and resources

[edit]Natural resources: petroleum, uranium, natron, kaolin, fish (Chari River, Logone River), gold, limestone, sand and gravel, salt

Land use:

arable land:

3.89%

permanent crops:

0.03%

other:

96.08% (2012)

Irrigated land: 302.7 km2 (2003)

Total renewable water resources: 43 km3 (2011)

Freshwater withdrawal (domestic/industrial/agricultural):

total:

0.88 km3/yr (12%/12%/76%)

per capita:

84.81 m3/yr (2005)

Environmental issues

[edit]Natural hazards: hot, dry, dusty, Harmattan winds occur in north; periodic droughts; locust plagues

Environment - current issues: inadequate supplies of potable water; improper waste disposal in rural areas contributes to soil and water pollution; desertification

See also

[edit]Extreme points

[edit]This is a list of the extreme points of Chad, the points that are farther north, south, east or west than any other location.

- Northernmost point - an unnamed location on the border with Libya, Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti region

- Easternmost point - the northern section of the Chad-Sudan border, Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti region *

- Southernmost point - unnamed location on the border with Central African Republic at a confluence in the Lébé river, Logone Oriental region

- Westernmost point - unnamed location west of the town of Kanirom and immediately north of Lake Chad, Lac Region

*Note: technically Chad does not have an easternmost point, the easternmost section of the border being formed by the 24° of longitude

References

[edit]- ^ Terms and Definitions FRA 2025 Forest Resources Assessment, Working Paper 194. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2023.

- ^ "Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, Chad". Food Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas M. (2005). Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Routledge. pp. 311–312. ISBN 978-1-57958-388-0. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Mueckenheim, J.K. (2007). Countries of the World & Their Leaders Yearbook 08. Gale virtual reference library. Thomson Gale. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-7876-8107-4. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "Lake Chad fishermen pack up their nets". BBC News. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Collelo, Thomas, ed. (1990). Chad: A Country Study (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 35–42. ISBN 0-16-024770-5.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Collelo, Thomas, ed. (1990). Chad: A Country Study (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 35–42. ISBN 0-16-024770-5.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service–Faya-Largeau". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Faya–Largeau Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Mainguet, Monique (1968). "Le Borkou. Aspects d'un modèle éolien". Annales de Géographie (in French). 77 (421): 296–322. doi:10.3406/geo.1968.15662.

- ^ bbc.co.uk

- ^ "World Weather Information Service–Ndjamena". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "ND'Jamena Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 22 June 2024. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "Station N'Djamena" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ Gorse, J.E.; Steeds, D.R. (1987). Desertification in the Sahelian and Sudanian Zones of West Africa. World Bank. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8213-0897-4. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Sarh". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Sarh Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Moundou". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Moundou Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Masters, Jeff. "NOAA: June 2010 the globe's 4th consecutive warmest month on record". Weather Underground. Jeff Masters' WunderBlog. Archived from the original on 19 July 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ "Wunder Blog : Weather Underground". Wunderground.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Bristow, Charlie S.; Drake, Nick; Armitage, Simon (1 April 2009). "Deflation in the dustiest place on Earth: The Bodélé Depression, Chad". Geomorphology. Contemporary research in aeolian geomorphology. 105 (1): 50–58. Bibcode:2009Geomo.105...50B. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.12.014. ISSN 0169-555X.

- ^ "Emi Koussi". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

Sources

[edit] This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

External links

[edit]- 15°N 19°E / 15°N 19°E – title=Field Listing: Geographic Coordinates. Geo-links for Geography of Chad.

- Detailed map of Chad from www.izf.net

Geography of Chad

View on GrokipediaLocation and Extent

Coordinates and Placement

Chad is a landlocked country in north-central Africa, positioned south of Libya and at the convergence of North, Central, and West African regions.[3] It shares borders with six nations: Libya (1,050 km to the north), Sudan (1,400 km to the east), Central African Republic (1,197 km to the south), Cameroon (1,110 km to the southwest), Nigeria (85 km at Lake Chad), and Niger (1,175 km to the west).[3] The total land boundary length is 6,017 km.[3] The representative geographic coordinates for Chad are 15°00′N latitude and 19°00′E longitude, denoting an approximate central location.[3] This places the country entirely within the Northern Hemisphere, north of the equator, and the Eastern Hemisphere, east of the Prime Meridian. Chad's position spans the Sahel belt, transitioning from Saharan desert in the north to Sudanese savanna in the south, influencing its arid to semi-arid climatic zones.[3]Borders and Neighboring Countries

Chad, a landlocked country in Central Africa, shares land borders totaling 6,406 kilometers with six neighboring countries.[3] To the north, Chad borders Libya along 1,050 kilometers, a frontier that includes rugged terrain such as the Tibesti Mountains and was the site of the Aouzou Strip territorial dispute resolved by the International Court of Justice in 1994 in Chad's favor.[3][4] To the east, it adjoins Sudan for 1,403 kilometers, following roughly latitudinal lines north of the Central African Republic tripoint.[3] On the south, Chad's 1,556-kilometer border with the Central African Republic generally follows the 9th parallel north, encompassing savanna and forested regions.[3] To the west and southwest, the borders are with Niger (1,196 km), Nigeria (85 km), and Cameroon (1,116 km), with the short Nigeria boundary concentrated around the fluctuating shores of Lake Chad and involving complex delineations due to the lake's shrinkage since the 1960s.[3][5] These western borders traverse Sahelian and Sudanian zones, marked by rivers like the Chari and Logone that influence hydrological boundaries near Cameroon and Nigeria.[5] The following table summarizes Chad's border lengths:| Neighboring Country | Approximate Direction | Length (km) |

|---|---|---|

| Libya | North | 1,050 |

| Sudan | East | 1,403 |

| Central African Republic | South | 1,556 |

| Cameroon | Southwest | 1,116 |

| Nigeria | West | 85 |

| Niger | Northwest | 1,196 |

Total Area and Internal Divisions

Chad possesses a total area of 1,284,000 square kilometers, ranking it as the fifth-largest country in Africa by land area and the twentieth-largest globally.[3] This encompasses 1,259,200 square kilometers of land and 24,800 square kilometers of inland water bodies, primarily associated with Lake Chad and associated wetlands in the southwest.[3] The country's expansive territory spans diverse physiographic zones, from the Saharan desert in the north to savannas and semi-arid steppes in the south, contributing to its significant ecological variability despite low overall population density. Administratively, Chad is structured into 23 regions, established through reforms culminating in 2012 that subdivided larger northern territories for enhanced governance.[6] These regions, also referred to as provinces since a 2018 nomenclature update, serve as the primary level of internal division and are further subdivided into 120 departments and 454 sub-prefectures as of July 2024, facilitating local administration and resource allocation.[7] Regional capitals, such as N'Djamena for the Chari-Baguirmi region, anchor these units, though disparities in size and population persist, with northern regions like Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti covering vast arid expanses exceeding 500,000 square kilometers while southern ones are more compact and densely inhabited.[8] This hierarchical system supports decentralized management amid Chad's challenges with security and infrastructure in remote areas.[9]Physical Geography

Geological Foundations

Chad's geological structure rests on a Precambrian crystalline basement composed primarily of metamorphic and igneous rocks, which forms the foundational layer across much of the country and underlies younger sedimentary deposits. This basement is exposed in elevated regions such as the Tibesti Massif in the northwest, the Ennedi Plateau in the northeast, and the Ouaddaï highlands in the east, where it consists of gneisses, schists, and granitic intrusions dating back over 2 billion years. These ancient rocks, part of the Saharan Metacraton, underwent multiple orogenic events during the Proterozoic era, resulting in folding, faulting, and metamorphism before stabilizing as part of the stable African craton.[10][11] The central Chad Basin, an intracratonic sedimentary depression covering approximately 2.4 million square kilometers, overlies the Precambrian basement and represents the dominant geological feature, filled with Mesozoic to Quaternary sediments reaching thicknesses of up to 5 kilometers in places. The basin's formation began in the Early Cretaceous around 140 million years ago, linked to rifting during the initial separation of the African and South American plates as part of the breakup of Gondwana, which created fault-bounded grabens that subsided and accumulated continental clastic sediments. Subsequent tectonic quiescence allowed for marine incursions in the Late Cretaceous, depositing shales and sandstones, followed by Tertiary fluvial and lacustrine fills as peripheral uplifts, starting about 25 million years ago, restricted drainage and promoted intra-continental sedimentation.[12][13][14] In the northern Tibesti Mountains, the Precambrian basement supports Cenozoic volcanic edifices, with two principal formations separated by an unconformity and intruded by post-tectonic granites that induced weak metamorphism; alkaline basalts and trachytes erupted from Miocene to Recent times, building peaks like Emi Koussi to 3,415 meters. The southern Bongor Basin, a Cretaceous-Paleogene rift extending into Chad, directly overlies fractured Precambrian basement, which serves as a reservoir for hydrocarbons due to weathering and faulting that enhance porosity. Paleozoic glacial features, including exhumed Carboniferous ice stream channels, are preserved in northern landscapes like the Ennedi Plateau, indicating ancient polar conditions before the region's aridification.[10][15][16][17]Terrain and Landforms

Chad's terrain consists primarily of a broad, shallow basin that rises gradually eastward and northward from the Lake Chad lowlands, encompassing arid central plains, northern desert expanses, and elevated massifs. The landscape features low elevations averaging 300-500 meters in the south and center, transitioning to rugged highlands exceeding 3,000 meters in isolated northern ranges. This topography results from sedimentary deposition in ancient lake basins, overlaid by volcanic activity and prolonged aeolian and fluvial erosion.[5][1][11] In the north, the Sahara Desert dominates, covering over half the country with ergs of longitudinal dunes, regs of gravel pavements, and hamadas of exposed bedrock plateaus. The Tibesti Mountains in the northwest form the most prominent relief, a volcanic chain of shield volcanoes and extinct craters spanning 500 by 300 kilometers, with Emi Koussi volcano rising to 3,415 meters as Chad's highest point. These mountains, uplifted by mantle plumes during the Miocene, exhibit calderas like that of Toussidé and extensive lava fields shaped by subaerial erosion.[5][18][19] The Ennedi Plateau in the northeast presents a starkly eroded sandstone escarpment, reaching elevations of 1,450 meters, dissected into labyrinthine canyons, natural arches, pillars, and inselbergs by differential weathering and wind abrasion over geological timescales. This massif, part of the broader Saharan platform, bounds the northern basin edge and hosts sparse wadis that channel rare flash floods.[20][21][22] Central Chad includes the Bodélé Depression, a 500-kilometer-long topographic low at approximately 320 meters above sea level, representing the desiccated floor of paleo-Mega-Chad Lake and serving as a major deflation basin for mineral dust mobilization. Flanking this are low clay and sand plateaus known as koros, ascending to 615 meters, interspersed with seasonal wadis. To the east, the Ouaddaï Massif rises 500-1,000 meters along the Sudanese border, while the Guéra Massif in the center peaks at 1,600 meters, both comprising Precambrian granites and gneisses exposed by uplift. Southern lowlands feature undulating savanna plains with ferruginous soils, rarely exceeding 600 meters, graded by fluvial incision from the Chari-Logone system.[23][24][25]Extreme Points of Chad

The northernmost point of Chad is situated on the border with Libya in the Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti region, near the Tibesti Massif, at a latitude of 23°29′ N.[26] This location marks the extent of Chad's Saharan territory, encompassing rugged volcanic highlands with elevations exceeding 3,000 meters in the vicinity.[3] The southernmost point lies on the international border with the Central African Republic, at 7°27′ N longitude approximately 15°48′ E.[27] This remote area falls within the Sudanian savanna zone, characterized by low-lying plains and seasonal flooding from tributaries of the Chari River system. Chad's easternmost point is found along the northern section of the border with Sudan, at 24°00′ E.[28] Positioned in the Ennedi Est region, it delineates the edge of the arid Ennedi Plateau, featuring sandstone formations and minimal vegetation adapted to hyper-arid conditions with annual precipitation below 50 mm. The westernmost point occurs near Lake Chad in the Lac region, west of Koulfane or similar settlements north of the lake's variable shoreline, at approximately 13°32′ E (derived from national bounding coordinates spanning 13.54° E to 23.41° E).[29] This vicinity is influenced by the lake's shrinking basin, where the boundary follows irregular depressions and marshlands shared with Nigeria and Cameroon, subject to hydrological fluctuations from Sahelian climate variability.[3]Hydrology

Major Rivers and Drainage Systems

Chad's hydrology is dominated by the endorheic Lake Chad Basin, which encompasses nearly the entire country and features internal drainage with no outlet to the sea.[30] The southern regions receive perennial river flows primarily from the Chari-Logone system, which supplies approximately 95% of the annual water inflow to Lake Chad.[30] In contrast, the arid northern territories lack permanent rivers and rely on ephemeral wadis that channel seasonal runoff into depressions or evaporate without contributing significantly to major basins.[31] The Chari River, Chad's principal waterway, originates in the Central African Republic and traverses southeastern Chad before merging with the Logone River at N'Djamena and discharging into Lake Chad.[32] Stretching approximately 1,400 kilometers in length, it sustains vital irrigation and fisheries in the Chari-Logone floodplains, with its basin covering about 523,000 square kilometers across multiple countries.[32] [33] The river's flow, generated largely from southern rainfall, varies seasonally but provides over 90% of Lake Chad's surface water input under normal conditions.[30] The Logone River, a major tributary of the Chari, rises in northern Cameroon and the Central African Republic, forming a significant portion of the Chad-Cameroon border for over 300 kilometers before joining the Chari near the capital.[34] Approximately 965 kilometers long, it features extensive papyrus swamps and seasonal flooding that link to adjacent systems like the Mayo Kébbi during high water periods.[34] Together with the Chari, the Logone drains southern Chad's savanna zones, supporting agriculture in the floodplains while contributing to the basin's overall endorheic dynamics.[35] Minor tributaries such as the Salamat and Bahr el Ghazal augment the Chari-Logone network in the southeast, while northern endorheic sub-basins, including those in the Batha region, collect sporadic runoff in closed depressions amid hyper-arid conditions.[31] These internal systems highlight Chad's hydrological gradient, from perennial southern flows to ephemeral northern arroyos, underscoring the country's reliance on the Lake Chad Basin for surface water resources.[36]Lakes and Wetlands

Chad possesses limited permanent lakes and wetlands, constrained by its predominantly arid and semi-arid climate, with surface water bodies concentrated in the southwest, central Sahel, and isolated northern desert oases. The most prominent is Lake Chad, a shallow endorheic lake in the southwest straddling borders with Nigeria, Niger, and Cameroon, covering approximately 1,350 square kilometers within Chad as of recent estimates, though its extent has diminished by over 90% since the 1960s due to reduced inflows, evaporation, and upstream diversions.[37] Its surrounding wetlands, encompassing marshes, papyrus swamps, and seasonal floodplains, span hundreds of thousands of hectares during high-water periods, fostering habitats for over 120 fish species, numerous waterbirds, and riparian vegetation such as Cyperus papyrus and Phragmites mauritianus.[38] These wetlands are integral to the Lake Chad flooded savanna ecoregion, providing seasonal grazing, fishing grounds, and migration stopovers, though they face degradation from drought cycles and overexploitation.[39] In northeastern Chad, the Lakes of Ounianga form a unique cluster of 18 permanent lakes within the hyperarid Sahara, receiving less than 2 mm of annual rainfall yet sustained by fossil groundwater from ancient aquifers discharging at rates sufficient to counter extreme evaporation.[40] Divided into the saline lakes of Ounianga Serir (covering about 10 square kilometers) and the freshwater Ounianga Kebir (including the deepest lake, Yoan, at around 27 meters), these oases span a tectonic basin amid Ennedi mountains, exhibiting vivid colors from algal blooms and mineral precipitates; designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2012 for their geological and hydrological rarity as the largest permanent surface waters in the Sahara.[40] The system supports sparse desert-adapted life, including fish in freshwater bodies and endemic microbial communities, but remains fragile to groundwater depletion.[41] Lake Fitri, a shallow endorheic freshwater lake in central Chad about 300 km east of N'Djaména, exemplifies Sahelian wetland variability, fed primarily by seasonal runoff from the Batha River and episodic rains, with surface area expanding from under 10,000 hectares in dry years to over 50,000 hectares during wet phases, occasionally tripling in extent. Designated a Ramsar site of international importance encompassing 195,000 hectares including fringing marshes and grasslands, it serves as a critical wintering ground for Palearctic migratory waterbirds, hosting tens of thousands annually, alongside resident species and fluctuating fish populations adapted to muddy, nutrient-rich waters.[43] Southern Chad's wetlands are more ephemeral, consisting of riverine floodplains and small lagoons along the Chari and Logone rivers during rainy seasons (June-October), supporting temporary grassy marshes that enhance soil moisture retention and biodiversity in savanna zones but contract sharply in dry periods, contributing minimally to permanent wetland coverage.[44] Overall, these features underscore Chad's hydrological dependence on sporadic precipitation and groundwater, with wetlands totaling under 5% of national land area and increasingly pressured by climate variability.[1]Lake Chad Basin Dynamics

The Lake Chad Basin encompasses an endorheic drainage area of approximately 2.5 million km² across Chad, Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and the Central African Republic, with Lake Chad as its terminal water body. Hydrology is driven primarily by seasonal inflows from the Chari-Logone River system, which supplies over 90% of the lake's water from upstream catchments in humid equatorial regions.[45] Annual mean river inflows have decreased by 47%, from 39.8 km³ in pre-1970s drought eras to 21.8 km³ in recent decades, reflecting reduced precipitation in the Sahel.[46] Evaporation dominates outflows, comprising about 96% of losses in the southern pool due to high temperatures and shallow depths, with negligible surface runoff to external systems.[47] Surface area fluctuations have defined the basin's modern dynamics, with the lake contracting from roughly 25,000 km² in the early 1960s—its post-colonial peak—to under 2,500 km² by the 1980s, a 90% decline sustained into the 21st century.[48] [49] The southern pool, hydrologically linked to Chad's Chari inflows, averaged 2,030 km² in 2004, rising slightly to 2,051 km² by 2021 amid variable wet seasons, while the northern pool remains largely desiccated except during floods.[50] This variability stems from the lake's shallow bathymetry (average depth 1.5–3 m), where modest volume shifts yield disproportionate area changes.[51] Primary drivers include climate-induced reductions in rainfall and inflows since the 1970s Sahelian droughts, compounded by upstream irrigation diversions—estimated at several km³ annually in Nigeria—and population-driven water demands.[51] [52] Quantitative assessments attribute 60–80% of inflow declines to climatic factors like altered monsoon patterns, with human extractions accelerating desiccation in an already marginal balance.[52] Recent data indicate volume stabilization or modest increases post-2000 from episodic wetter conditions, though persistent warming elevates evaporation and constrains recovery.[53]| Period | Approximate Surface Area (km²) | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Early 1960s | 25,000 | Peak post-drought inflows; wetter Sahel phase[48] |

| 1980s | 2,000–5,000 | Onset of prolonged droughts; initial irrigation expansions[49] |

| 2000s–2020s | 1,500–2,500 (southern pool dominant) | Stabilized low levels; seasonal variability[50] [52] |

Climate

Zonal Climate Divisions

Chad's climate exhibits distinct zonal divisions aligned with its latitudinal extent, transitioning from hyper-arid conditions in the north to more humid savanna climates in the south. These zones reflect the influence of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and proximity to the Sahara Desert, with the northern third dominated by hot desert (BWh) under Köppen-Geiger classification, the central Sahelian belt featuring hot semi-arid (BSh) conditions, and the southern Sudanian region characterized by tropical savanna (Aw) climates.[55][56] In the northern Saharan zone, encompassing Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti and parts of Kanem, annual precipitation averages less than 50 mm, with vast areas receiving under 200 mm, supporting minimal vegetation and extreme diurnal temperature swings—daytime highs exceeding 45°C in summer and nocturnal lows dropping below 10°C. This arid regime persists due to persistent high-pressure systems and distance from moist equatorial air masses, rendering the region unsuitable for agriculture without irrigation.[57][58] The central Sahelian zone, stretching across Bahr el Ghazal and Guéra regions, experiences semi-arid conditions with annual rainfall between 200 and 600 mm, concentrated in a brief wet season from June to September driven by ITCZ migration. Average temperatures range from 25°C to 35°C year-round, with occasional sandstorms exacerbating aridity; this transitional belt sustains pastoralism but faces recurrent droughts, as evidenced by historical data showing rainfall variability of up to 30% decade-to-decade.[59][58] Southern Chad, including Logone Occidental and Mayo-Kebbi, falls within the tropical savanna zone, receiving 800 to 1,100 mm of rainfall annually, primarily during the June-October monsoon, supporting denser grasslands and limited forestry. Temperatures average 25-32°C, with higher humidity mitigating extremes, though dry harmattan winds from the north influence the cooler season; cities like Moundou record peaks near 1,100 mm, enabling rain-fed agriculture but exposing the area to flooding risks.[57][60]Seasonal Patterns and Variability

Chad experiences a pronounced seasonal cycle dominated by the alternation between a dry season and a short rainy season, driven by the migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and monsoon influences. The dry season spans from October to May across the country, with the most intense phase from December to February featuring the Harmattan winds—northeast trade winds originating from the Sahara that bring cool, dry air, high dust loads from the Bodélé Depression, and reduced humidity.[61][62] These winds lower daytime temperatures slightly in northern and central regions to averages of 25–33°C while causing nocturnal lows to drop to 14–17°C, and they exacerbate aridity, increasing fire risks in savanna areas.[63][64] The rainy season, influenced by the West African Monsoon, typically lasts from June to September in central Sahel zones like N'Djamena, with peak precipitation in August averaging 145 mm monthly, though southern savanna regions such as Sarh and Moundou extend it from May to October with totals of 800–1200 mm annually concentrated in these months.[65][66] Rainfall occurs primarily through convective thunderstorms and organized mesoscale systems, delivering 80–90% of annual totals during this period, but northern desert areas receive less than 50 mm yearly, often in sporadic events.[67] Temperatures during the wet season remain high, with daytime maxima exceeding 35°C and minimal relief from humidity, transitioning to pre-monsoon heat peaks of up to 42°C in April–May.[57] Seasonal variability is marked by high intra- and interannual fluctuations in rainfall onset, duration, and intensity, particularly in the Sahel transition zone, where the Intertropical Front's northward advance can vary by weeks, leading to erratic wet spells or prolonged dry intrusions.[68] In N'Djamena, monthly rainfall exhibits standard deviations up to 1.87 cm, contributing to frequent floods in wet years or early-season droughts affecting agriculture.[55] Dust mobilization during Harmattan peaks depends on Mediterranean pressure variability, amplifying visibility reductions and respiratory health impacts in variable years.[69] Historical data from 1950–2020 show declining trends in wet-season totals post-1970s (e.g., 1.07 mm/year decrease basin-wide), with partial recovery since the 1990s linked to strengthened monsoon dynamics, underscoring vulnerability to large-scale modes like El Niño.[70][71]Recent Climate Data and Trends

Chad's average annual temperatures have risen by more than 0.5°C since the 1990s, nearly double the global average warming rate, contributing to its status as one of the world's hottest countries.[72] Historical climatological data from 1991 to 2020 reveal a pronounced warming signal in mean surface air temperatures, with annual averages ranging from approximately 25.5°C to 29°C and seasonal maxima exceeding 36–42°C in April–May.[59] This trend aligns with broader post-1980s global patterns but is amplified in Chad's arid and semi-arid zones by reduced cloud cover and intensified solar radiation.[59] Precipitation has shown increased irregularity since the 1990s, with volatile seasonal patterns exacerbating droughts and floods rather than a uniform decline.[72] In the Lake Chad Basin, mean annual rainfall rose in major stations like N’Djamena and Sarh from 2018 to 2022 (excluding a dip in 2021), culminating in above-average totals in 2022 that included extreme events with rainfall intensity amplified up to 80-fold by climate variability.[71] Wet season peaks, typically July–August with 100–150 mm monthly, have thus become more erratic, transitioning from prolonged dry spells to intense downpours.[59][71] These dynamics are evident in the Lake Chad Basin's hydrology, where river inflows from the Chari-Logone system (supplying 82% of the lake's water) and direct precipitation have driven recent recoveries amid historical declines.[71] Water levels at N’Djamena reached 7.47 m in 2020 and peaked at 8.14 m in November 2022, with lake levels hitting 3.3 m by December 2022 and surface area expanding to 18,800 km²—a 7.5% rise over the 2012–2022 mean—indicating a temporary strengthening of the hydrological cycle despite high evaporation rates over 2,000 mm annually.[71] Floods from these events displaced 1.3 million people in 2022 and 1.7 million in 2024, underscoring heightened variability over steady desiccation.[72] Desertification persists as a counter-trend, with the Sahara advancing southward at approximately 60 km per decade, driven by cumulative aridity and land-use pressures rather than solely recent precipitation shifts.[72] Satellite-derived analyses confirm ongoing soil degradation in northern regions, though southern vegetation responses to episodic rains have shown localized resilience.[71] Projections suggest continued warming of 0.65–1.6°C and potential precipitation reductions of 11–13% over the next two decades, though basin-specific data indicate risks of amplified extremes over linear drying.[73]Biophysical Features

Vegetation Zones

Chad's vegetation zones align with its latitudinal bioclimatic divisions, driven by a pronounced north-south precipitation gradient from less than 200 mm annually in the Sahara to over 800 mm in the Sudanian region. The country spans three primary zones: the arid Sahara in the north, the semi-arid Sahel centrally, and the subhumid Sudanian savannas in the south, encompassing desert shrublands, acacia-dominated steppes, and woodland mosaics respectively. These zones reflect adaptations to water scarcity, with total vascular plant diversity reaching 4,318 species, including 71 endemics.[74] The northern Saharan zone, occupying roughly the northern half of Chad's 1,284,000 km² territory, supports xerophytic shrublands and ephemeral grasses suited to hyper-arid conditions. Vegetation is sparse, featuring drought-tolerant species such as Acacia tortilis and Balanites aegyptiaca amid sand dunes and rocky plateaus, with oases sustaining Phoenix dactylifera palms. Montane extensions in the Tibesti Mountains host elevated diversity, with approximately 450–568 species incorporating Saharan, Sahelian, Mediterranean, and Afromontane elements, including relict conifers and endemics.[75][74] Transitioning southward, the central Sahelian zone features open savannas and tree steppes characterized by thorny acacias, notably Acacia seyal across over 38 million hectares, interspersed with grasses like Cenchrus biflorus. Annual rainfall of 200–600 mm sustains this grassland-shrub matrix, which grades into denser woodlands near watercourses, though overgrazing and fuelwood extraction have thinned cover in recent decades.[74] In the southern Sudanian zone, comprising about 10% of the land area but supporting denser biomass, vegetation includes tall perennial grasses (Andropogon spp.), broad-leaved deciduous trees, and gallery forests along rivers. Key species encompass the shea butter tree (Vitellaria paradoxa), numbering 50–60 million individuals, and diverse flora in protected areas like Zakouma National Park, where over 700 species occur. This zone's woodland-savanna mosaic facilitates higher productivity, with shrubs and forbs dominating post-fire regrowth cycles.[74][72] Specialized habitats interrupt these gradients, such as the Lake Chad flooded savannas, where aquatic and semi-aquatic vegetation thrives on seasonal inundation. Dominant taxa include reeds (Phragmites mauritianus), sedges (Cyperus papyrus), and grasses (Echinochloa pyramidalis, Vossia cuspidata), forming critical buffers against erosion but vulnerable to basin shrinkage. Chad's seven ecoregions—spanning these biomes—underscore micro-variations, including East Saharan xeric woodlands and montane enclaves.[38][76]Soil Composition and Fertility

Chad's soils exhibit significant regional variation, reflecting the country's transition from Saharan desert in the north to Sudanian savanna in the south. In the northern arid zones, dominant soil types include Arenosols, Regosols, and Yermosols, primarily composed of loose quartz-rich sands with minimal clay or organic content, resulting in very low water retention and nutrient-holding capacity. These soils, often featuring shifting sands and stony surfaces derived from sandstone and shale parent materials, possess organic matter levels typically below 0.5% and are deficient in nitrogen and other essential nutrients, rendering them largely infertile for agriculture and suitable only for nomadic pastoralism.[77] In the central Sahelian belt, Lixisols and Luvisols prevail, characterized by ferruginous tropical profiles with sandy loam textures overlying clay-enriched subsoils, formed from weathered basement complex rocks like granitic gneiss and schist. These soils suffer from low cation exchange capacity (CEC), pronounced leaching of bases under episodic rainfall, and shallow rooting depths in areas with petroferric horizons, leading to moderate fertility constrained by phosphorus fixation and nitrogen volatility; nutrient depletion is exacerbated by overgrazing and wind erosion.[77][78] Southern Chad features more varied soils, including Ferric Acrisols, Vertisols, and Fluvisols in alluvial plains along the Chari and Logone rivers, with clay-rich compositions from lacustrine and fluvial sediments providing higher initial fertility through better structure and moisture retention. Vertisols, with their high smectite clay content, exhibit shrink-swell properties that enhance tilth but promote cracking and erosion, while Fluvisols benefit from periodic sediment deposition yet face sodicity in poorly drained Gleysols. Overall fertility here supports subsistence cropping of millet and sorghum, though widespread degradation from continuous cultivation without replenishment has reduced organic matter to 0.5-1% and intensified nutrient mining, necessitating practices like manure application or fallowing for sustainability.[77][79]| Soil Type | Region | Key Composition | Fertility Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arenosols/Regosols/Yermosols | North | Quartz sands, low clay | Low nutrients, poor retention; N deficiency |

| Lixisols/Luvisols | Central | Sandy loam over clay, iron oxides | Leaching, low CEC; P fixation |

| Acrisols/Vertisols/Fluvisols | South | Clay-rich alluvium, smectites | Erosion, sodicity; organic matter decline |

Biodiversity and Ecosystems

Chad's ecosystems span three primary bioclimatic zones: the hyper-arid Sahara in the north, the semi-arid Sahel in the center, and the sub-humid Sudanian savanna in the south, each hosting distinct flora and fauna adapted to varying precipitation and soil conditions.[74] The Sahara zone features sparse vegetation dominated by drought-resistant shrubs and succulents, supporting nomadic herbivores such as the critically endangered addax (Addax nasomaculatus) and dorcas gazelle (Gazella dorcas), alongside reptiles like the Sahara crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus).[81] In the Sahelian belt, ecosystems transition to acacia-dominated thorn savannas and grasslands, sustaining species including cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), ostriches (Struthio camelus), and various antelopes, though populations have declined due to habitat fragmentation and poaching.[74] The southern Sudanian zone, with taller grasses and scattered deciduous trees like Ficus and Khaya species, harbors higher biomass, including African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana), West African lions (Panthera leo leo), Kordofan giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis), and hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius), particularly in floodplains and gallery forests along rivers.[82] Aquatic and wetland ecosystems, concentrated around Lake Chad and the Chari-Logone river system, form critical refugia for biodiversity, with over 179 fish species recorded in Lake Chad alone, alongside migratory waterfowl such as African fish eagles (Haliaeetus vocifer) and marabou storks (Leptoptilos crumenifer).[83] These habitats, characterized by papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) and reed (Phragmites mauritianus) marshes, support 532 bird species nationwide, many dependent on seasonal flooding for breeding.[84] Floral diversity peaks in protected southern areas, with Zakouma National Park documenting over 700 plant species, including medicinal and timber varieties, while the Tibesti Mountains host 568 vascular plants adapted to rocky, ephemeral wadis.[74] Conservation efforts emphasize protected areas covering key habitats, including three national parks (Zakouma, Aoukala, and Manda), seven wildlife reserves, and ten classified forests, which safeguard remaining large mammal populations amid threats like desertification and illegal hunting.[82] Reintroduction programs have bolstered species such as the scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah), downlisted from Extinct in the Wild to Endangered by IUCN in 2023 following releases in the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Reserve.[85] However, Chad records 136 mammal species, with five critically endangered (e.g., addax) and nine vulnerable, reflecting pressures from overgrazing, agricultural expansion, and climate-induced wetland shrinkage, which have reduced faunal ranges by up to 90% in some Sahelian zones since the 1970s.[83] Initiatives by organizations like African Parks in Ennedi and Sahara Conservation monitor flagship species, using eco-guard patrols to curb poaching rates that previously decimated herds.[81]Resources and Land Utilization

Mineral and Hydrocarbon Deposits

Chad's hydrocarbon resources are dominated by petroleum deposits in the Doba Basin in the southern part of the country, where commercial production began in 2003 following discoveries in the 1970s and 1990s by ExxonMobil and partners.[86] Proven oil reserves stand at approximately 1.5 billion barrels, ranking tenth in Africa, with crude oil production averaging around 127,000 barrels per day as of mid-2025, though output has faced declines due to field maturation and delays in new developments.[87][88] The oil is exported via a 1,070-kilometer pipeline to the Cameroonian port of Kribi, contributing significantly to government revenue despite challenges like infrastructure limitations and security risks in the producing region.[89] Natural gas reserves are associated with oil fields but remain largely undeveloped, with potential for future extraction limited by market access and investment constraints.[90] Non-hydrocarbon minerals are extracted on a smaller scale, with natron (sodium carbonate) historically the primary commodity, sourced from deposits around Lake Chad, the Kanem Prefecture wadis, and near Faya-Largeau oasis, used traditionally for salt, soap production, and animal fodder preservation.[91] Artisanal gold mining predominates, targeting alluvial deposits along rivers such as the Mayo N'Dala—estimated to hold several tonnes—and across approximately 40 sites spanning 1,200 kilometers from south to west, though formal production remains minimal due to informal operations and lack of large-scale investment.[92][93] Chad possesses untapped potential in other minerals, including uranium occurrences in Precambrian basement rocks and northern sedimentary formations, particularly in the Tibesti massif and Chad Basin, where exploration has identified prospects but no commercial mining as of 2025.[11] Additional deposits of tin, tungsten, bauxite, limestone, kaolin, and salt are noted in geological surveys, with the Tibesti region highlighted for base and precious metals, yet exploitation is hindered by remoteness, political instability, and insufficient infrastructure.[10][91] Overall, mineral development lags behind hydrocarbons, constrained by artisanal practices and limited foreign investment.[94]Agricultural and Pastoral Practices

Agriculture in Chad predominantly consists of rainfed, subsistence-based farming systems, with extensive practices yielding low productivity per hectare due to reliance on traditional techniques and limited mechanization. Approximately 80 percent of the population engages in agriculture or related activities, focusing on staple crops such as sorghum, millet, maize, and peanuts, primarily in the more fertile southern Sudanese zone where rainfall exceeds 800 mm annually. Cereal production reached an estimated 2.9 million metric tons in the 2022-2023 season, sufficient to meet basic domestic needs but vulnerable to erratic precipitation patterns. Cash crops like cotton, grown mainly along the Logone and Chari river basins, account for a smaller share of output but provide export revenue, with production fluctuating between 100,000 and 150,000 tons annually in recent years.[79][95][96][72] Pastoral practices form the backbone of livestock production, encompassing mobile herding systems that utilize transhumant movements across arid and semi-arid zones to follow seasonal pastures and water sources. Chad's livestock inventory exceeded 120 million animals in 2019, including around 30 million cattle, 25 million sheep, 20 million goats, and significant camel populations in the north, contributing 6-7 percent to national GDP and over 35 percent to rural household assets. These systems, practiced by ethnic groups such as Arab, Fulani, and Toubou nomads, emphasize extensive grazing on natural rangelands, with herd sizes adapted to environmental carrying capacity rather than intensive feeding. Pastoralism accounts for about 80 percent of the total livestock sector, enabling economic resilience in marginal lands but facing pressures from overgrazing and conflict over resources.[97][98][99] Agro-pastoral integration prevails in transitional zones like the Lake Chad basin, where sedentary crop farming combines with seasonal livestock rearing, utilizing crop residues as fodder and manure for soil fertility. Farming techniques remain largely manual, involving hoe-based tillage and minimal irrigation, though flood-recession agriculture along riverine wadis supports secondary crops such as rice and vegetables. Recent data indicate food production indices rising to 130.3 in 2022 from a 2004-2006 base of 100, reflecting modest gains from improved seed varieties and extension services, yet overall yields lag behind regional averages due to soil degradation and climate variability.[100][101][102]Forestry and Land Cover Changes

Chad's natural forest cover stood at 9.32 million hectares in 2020, comprising 7.3% of its total land area, primarily concentrated in the southern savanna and Sahel zones.[103] Between 2001 and 2020, the country experienced a net loss of 49.9 thousand hectares of tree cover, representing a 12% decline from 2000 levels, with annual deforestation rates rising modestly from 0.6% in the 1990-2000 period to 0.65% during 2005-2010.[104] In 2024 alone, Chad lost 86.7 thousand hectares of natural forest, equivalent to 23.8 million tons of CO₂ emissions.[103] Primary drivers of these losses include shifting agriculture, extraction of firewood and charcoal for domestic energy needs, and commodity-driven logging, accounting for 93% of tree cover loss transitioning to full deforestation from 2001 to 2024.[103] Population growth exacerbates demand for fuelwood and agricultural expansion, while overgrazing and bushfires degrade remaining wooded areas, particularly in the vulnerable Sahel transition zone.[74] These anthropogenic pressures compound natural aridity, leading to sparse, open woodlands rather than dense forests, with southern regions bearing the brunt of conversion to cropland and pasture.[105] Efforts to counteract deforestation include participation in the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100), targeting afforestation, agroforestry, and restoration of degraded lands across Sahelian states.[106] The Great Green Wall initiative has expanded reforestation in Chad since the 2010s, aiming to combat desert encroachment through tree planting and sustainable land management, though uncontrolled logging threatens project efficacy.[107] [108] Complementary measures, such as promoting "green charcoal" production from invasive species and community-based riverbank reforestation in regions like Mayo Kebbi, seek to reduce reliance on native trees, but implementation faces challenges from poverty and governance constraints.[109] [110]Environmental Dynamics

Desertification Processes

Desertification in Chad primarily involves the southward encroachment of the Sahara Desert into the Sahelian zone, characterized by progressive land degradation through soil erosion, vegetation loss, and dune mobilization. This process has advanced at a rate of approximately 3 kilometers per year in northern regions since the 1960s, shifting the 300 mm isohyet southward from the 14th to the 13th parallel between 1951 and 2000.[111][112] Approximately 58% of Chad's land area is already classified as desert, with an additional 30% highly vulnerable to further degradation.[101] Wind erosion constitutes a dominant mechanism, driven by the strong, dry Harmattan winds that prevail during the extended dry season, stripping exposed topsoil and mobilizing sand particles into dunes that migrate southward. Loss of woody vegetation, critical for dune stabilization, intensifies this erosion, as trees and shrubs anchor sands and reduce wind velocity near the surface. Overgrazing by dense livestock herds, accounting for 62% of observed land damage, exacerbates the process by denuding grasslands, compacting soils, and hindering regrowth, thereby leaving surfaces barren and susceptible to aeolian transport.[74][111][113] Anthropogenic deforestation for fuelwood and charcoal production, coupled with agricultural expansion, further depletes vegetative cover; open forests declined by 29% (equivalent to 4,700 km² lost) between 1975 and 2013, while cultivated land expanded by 190% over the same period. These activities reduce organic matter input to soils, leading to nutrient depletion, crust formation, and diminished water infiltration, which in turn promotes sheet and gully erosion during infrequent heavy rains. Salinization from evaporative concentration in shallow groundwater areas and overexploitation of phreatic waters compound fertility loss, creating feedback loops where degraded lands support less biomass, accelerating bare soil exposure.[111][114] In 2003 assessments, degraded lands spanned 428,000 km², or 33.43% of the national territory, underscoring the interplay of climatic aridity—marked by recurrent droughts since the 1960s—and human-induced pressures in perpetuating these biophysical processes.[111]Water Scarcity and Resource Depletion

Chad's water resources are dominated by Lake Chad in the southwest, which receives inflows primarily from the Chari and Logone rivers originating in the Central African Republic and Cameroon, alongside sporadic rainfall in the Sahelian zone averaging 300-600 mm annually in the lake basin. High evaporation rates, exceeding 2,000 mm per year due to intense solar radiation and temperatures often surpassing 40°C, compound scarcity across the arid and semi-arid landscapes. Surface water availability is seasonal and unreliable, with groundwater from the Lake Chad Basin Aquifer System providing supplementary but unevenly distributed reserves estimated at 11.5 km³ annually renewable, though shared across basin countries and vulnerable to overabstraction.[115][116] Lake Chad's surface area has contracted dramatically, from approximately 25,000 km² in the early 1960s to less than 2,500 km² by the 2000s, representing a 90% reduction attributed to diminished river inflows, expanded irrigation upstream, and population pressures exceeding 40 million in the basin by 2020. Inflows from the Chari-Logone system, which historically supplied 90% of the lake's water, declined due to dam constructions like Nigeria's Alau Dam (completed 1985) and increased agricultural withdrawals for rice and cotton farming, alongside natural variability in precipitation. While climatic drying contributed—Sahelian rainfall dropped 20-30% during 1970-1980s droughts—studies emphasize anthropogenic factors, including unplanned irrigation diverting up to 50% of potential inflows and basin population tripling since 1960, as primary drivers over pure climate attribution. Recent satellite data indicate stabilization or minor fluctuations since the 2000s, with occasional refilling from heavy rains, though the northern pool remains largely desiccated.[48][117][118] Groundwater depletion manifests in falling water tables, particularly in the Quaternary shallow aquifers around Lake Chad, where abstraction for irrigation has risen since the mid-20th century, with 80% of withdrawals supporting agriculture amid only 20% for domestic use. In eastern regions like Kanem and Batha, arid conditions limit recharge, leading to localized overexploitation and salinization, while the deeper Nubian Sandstone Aquifer offers potential but faces extraction rates outpacing renewal in high-demand southern areas. Overall, infrastructure deficits leave 68% open defecation rates and millions without safe drinking water, fueling resource conflicts and migration, as evidenced by clashes over shrinking pastoral wells and fisheries. Sustainable management remains challenged by transboundary dependencies, with Chad relying 65% on shared groundwater flows.[119][116][120]Debates on Climate Attribution and Policy Responses