Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Deep Space Climate Observatory

View on Wikipedia

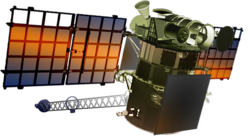

An artist's rendering of DSCOVR satellite | |||||||||||||

| Names | DSCOVR Triana AlGoreSat | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Space weather | ||||||||||||

| Operator | NASA / NOAA | ||||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 2015-007A | ||||||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 40390 | ||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||

| Mission duration | 5 years (planned)[1] 10 years, 8 months, 22 days (elapsed) | ||||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||||

| Bus | SMEX-Lite | ||||||||||||

| Manufacturer | Goddard Space Flight Center | ||||||||||||

| Launch mass | 570 kg (1,260 lb)[2] | ||||||||||||

| Dimensions | Undeployed: 1.4 × 1.8 m (4 ft 7 in × 5 ft 11 in) | ||||||||||||

| Power | 600 watts | ||||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||||

| Launch date | 11 February 2015, 23:03:42 UTC | ||||||||||||

| Rocket | Falcon 9 v1.1 | ||||||||||||

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral, SLC-40 | ||||||||||||

| Contractor | SpaceX | ||||||||||||

| Entered service | 8 June 2015 | ||||||||||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||||||||||

| Reference system | Heliocentric orbit[1] | ||||||||||||

| Regime | Sun-Earth Lagrange point L1 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

DSCOVR logo Space Weather program | |||||||||||||

Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR; formerly known as Triana, unofficially known as GoreSat[3]) is a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) space weather, space climate, and Earth observation satellite. It was launched by SpaceX on a Falcon 9 v1.1 launch vehicle on 11 February 2015, from Cape Canaveral.[4] This is NOAA's first operational deep space satellite and became its primary system of warning Earth in the event of solar magnetic storms.[5]

DSCOVR was originally proposed as an Earth observation spacecraft positioned at the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, providing live video of the sunlit side of the planet through the Internet as well as scientific instruments to study climate change. Political changes in the United States resulted in the mission's cancellation, and in 2001 the spacecraft was placed into storage.

Proponents of the mission continued to push for its reinstatement, and a change in presidential administration in 2009 resulted in DSCOVR being taken out of storage and refurbished, and its mission was refocused to solar observation and early warning of coronal mass ejections while still providing Earth observation and climate monitoring. It launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 launch vehicle on 11 February 2015, and reached L1 on 8 June 2015, joining the list of objects orbiting at Lagrange points.

NOAA operates DSCOVR from its Satellite and Product Operations Facility in Suitland, Maryland. The acquired space data that allows for accurate weather forecasts are carried out in the Space Weather Prediction Center in Boulder, Colorado. Archival records are held by the National Centers for Environmental Information, and processing of Earth sensor data is carried out by NASA.[1]

History

[edit]

DSCOVR began as a proposal in 1998 by then-Vice President Al Gore for the purpose of whole-Earth observation at the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, 1.5×106 km (0.93×106 mi) from Earth.[3][6] Originally known as Triana, named after Rodrigo de Triana, the first of Columbus's crew to sight land in the Americas, the spacecraft's original purpose was to provide a near-continuous view of the entire Earth and make that live image available via the Internet. Gore hoped not only to advance science with these images, but also to raise awareness of the Earth itself, updating the influential Blue Marble photograph that was taken by Apollo 17.[7] In addition to an imaging camera, a radiometer would take the first direct measurements of how much sunlight is reflected and emitted from the whole Earth (albedo). This data could constitute a barometer for the process of global warming. The scientific goals expanded to measure the amount of solar energy reaching Earth, cloud patterns, weather systems, monitor the health of Earth's vegetation, and track the amount of UV light reaching the surface through the ozone layer.

In 1999, NASA's Inspector General reported that "the basic concept of the Triana mission was not peer reviewed", and "Triana's added science may not represent the best expenditure of NASA's limited science funding".[8] Members of the U.S. Congress asked the National Academy of Sciences whether the project was worthwhile. The resulting report, released March 2000, stated that the mission was "strong and scientifically vital".[9]

The Bush administration put the project on hold shortly after George W. Bush's inauguration in January 2001.[6] Triana was removed from its original launch opportunity on STS-107 (the ill-fated Columbia mission in 2003).[3] The US$150 million[3] spacecraft was placed into nitrogen blanketed storage at Goddard Space Flight Center in November 2001 and remained there for the duration of the Bush administration.[10] NASA renamed the spacecraft Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) in 2003 in an attempt to regain support for the project,[3] but the mission was formally terminated by NASA in 2005.[11]

In November 2008, funded by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Air Force, the spacecraft was removed from storage and underwent testing to determine its viability for launch.[12][13] After the Obama administration took presidency in 2009, that year's budget included US$9 million marked for refurbishment and readiness of the spacecraft,[14] resulting in NASA refurbishing the EPIC instrument and recalibrating the NISTAR instrument.[15] Al Gore used part of his book Our Choice (2009) as an attempt to revive debate on the DSCOVR payload. The book mentions legislative efforts by senators Barbara Mikulski and Bill Nelson to get the spacecraft launched.[16] In February 2011, the Obama administration attempted to secure funding to re-purpose the DSCOVR spacecraft as a solar observatory to replace the aging Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) spacecraft, and requested US$47.3 million in the 2012 fiscal budget toward this purpose.[11] Part of this funding was to allow the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) to construct a coronal mass ejection imager for the spacecraft, but the time required would have delayed DSCOVR's launch and it was ultimately not included.[1][11] NOAA allocated US$2 million in its 2011 budget to initiate the refurbishment effort, and increased funding to US$29.8 million in 2012.[3]

In 2012, the Air Force allocated US$134.5 million to procure a launch vehicle and fund launch operations, both of which were awarded to SpaceX for their Falcon 9 rocket.[3][17] In September 2013, NASA cleared DSCOVR to proceed to the implementation phase targeting an early 2015 launch,[18] which ultimately took place on 11 February 2015.[12] NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center is providing management and systems engineering to the mission.

In the 2017 documentary, An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power, Al Gore speaks of the history of the DSCOVR spacecraft and its relation to climate change.[19]

Spacecraft

[edit]

DSCOVR is built on the SMEX-Lite spacecraft bus and has a launch mass of approximately 570 kg (1,260 lb). The main science instrument sets are the Sun-observing Plasma Magnetometer (PlasMag) and the Earth-observing NIST Advanced Radiometer (NISTAR) and Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC). DSCOVR has two deployable solar arrays, a propulsion module, boom, and antenna.[20]

The propulsion module had 145 kg of hydrazine propellant.[21]

From its vantage point, DSCOVR monitors variable solar wind conditions, provides early warning of approaching coronal mass ejections and observes phenomena on Earth, including changes in ozone, aerosols, dust and volcanic ash, cloud height, vegetation cover and climate. At its Sun-Earth L1 location it has a continuous view of the Sun and of the sunlit side of the Earth. After the spacecraft arrived on-site and entered its operational phase, NASA began releasing near-real-time images of Earth through the EPIC instrument's website.[22] DSCOVR takes full-Earth pictures about every two hours and is able to process them faster than other Earth observation satellites.[23]

The spacecraft is in a looping halo orbit around the Sun-Earth Lagrange point L1 in a six-month period, with a spacecraft–Earth–Sun angle varying from 4° to 15°.[24][25]

Instruments

[edit]PlasMag

[edit]The Plasma-Magnetometer (PlasMag) measures solar wind for space weather predictions. It can provide early warning detection of solar activity that could cause damage to existing satellite systems and ground infrastructure. Because solar particles reach L1 about an hour before Earth, PlasMag can provide a warning of 15 to 60 minutes before a coronal mass ejection (CME) arrives. It does this by measuring "the magnetic field and the velocity distribution functions of the electron, proton and alpha particles (helium nuclei) of solar wind".[26] It has three instruments:[26]

- Magnetometer measures magnetic field

- Faraday cup measures positively charged particles

- Electrostatic analyzer measures electrons

EPIC

[edit]

The Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) takes images of the sunlit side of Earth for various Earth science monitoring purposes in ten different channels from ultraviolet to near-infrared. Ozone and aerosol levels are monitored along with cloud dynamics, properties of the land, and vegetation.[29]

EPIC has an aperture diameter of 30.5 cm (12.0 in), a focal ratio of 9.38, a field of view of 0.61°, and an angular sampling resolution of 1.07 arcseconds. Earth's apparent diameter varies from 0.45° to 0.53° full width. Exposure time for each of the 10 narrowband channels (317, 325, 340, 388, 443, 552, 680, 688, 764, and 779 nm) is about 40 ms. The camera produces 2048 × 2048 pixel images, but to increase the number of downloadable images to ten per hour the resolution is averaged to 1024 × 1024 on board. The final resolution is 25 km/pixel (16 mi/pixel).[29]

NISTAR

[edit]The National Institute of Standards and Technology Advanced Radiometer (NISTAR) was designed and built between 1999 and 2001 by NIST in Gaithersburg, MD and Ball Aerospace & Technologies in Boulder, Colorado. NISTAR measures irradiance of the sunlit face of the Earth. This means that NISTAR measures if the atmosphere of Earth is taking in more or less solar energy than it is radiating back towards space. This data is to be used to study changes in Earth's radiation budget caused by natural and human activities.[30]

Using NISTAR data, scientists can help determine the impact that humanity is having on the atmosphere of Earth and make the necessary changes to help balance the radiation budget.[31] The radiometer measures in four channels:

- For total radiation in ultraviolet, visible and infrared in the range 0.2–100 μm

- For reflected solar radiation in the ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared in the range 0.2–4 μm

- For reflected solar radiation in infrared in the range 0.7–4 μm

- For calibration purposes in the range 0.3–1 μm

Launch

[edit]The DSCOVR launch was conducted by launch provider SpaceX using their Falcon 9 v1.1 rocket. The launch of DSCOVR took place on 11 February 2015, following two scrubbed launches. It took DSCOVR 110 days from when it left Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Florida, to reach its target destination 1.5×106 km (0.93×106 mi) away from Earth at the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point.[32][33]

Launch attempt history

[edit]| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 Feb 2015, 11:10:00 pm | Scrubbed | — | Technical | (T02:40:00) | >90 | Range issues: tracking,[34] first-stage video transmitter issues noted |

| 2 | 10 Feb 2015, 11:04:49 pm | Scrubbed | 1 day 23 hours 55 minutes | Weather | 80 | Upper-level winds at the launch pad exceeded 100 knots (190 km/h; 120 mph) at 7,600 m (24,900 ft) | |

| 3 | 11 Feb 2015, 11:03:42 pm | Success | 0 days 23 hours 59 minutes | >90 |

Operation

[edit]On 6 July 2015, DSCOVR returned its first publicly released view of the entire earthlight side of Earth from 1,475,207 km (916,651 mi) away, taken by the EPIC instrument. EPIC provides a daily series of Earth images, enabling the first-time study of daily variations over the entire globe. The images, available 12 to 36 hours after they are made, have been posted to a dedicated web page since September 2015.[27]

DSCOVR was placed in operation at the L1 Lagrange point to monitor the Sun, because the constant stream of particles from the Sun (the solar wind) reaches L1 about 60 minutes before reaching Earth. DSCOVR will usually be able to provide a 15- to 60-minute warning before a surge of particles and magnetic field from a coronal mass ejection (CME) reaches Earth and creates a geomagnetic storm. DSCOVR data will also be used to improve predictions of the impact locations of a geomagnetic storm to be able to take preventative action. Electronic technologies such as satellites in geosynchronous orbit are at risk of unplanned disruptions without warnings from DSCOVR and other monitoring satellites at L1.[35]

On 16–17 July 2015, DSCOVR took a series of images showing the Moon during a transit of Earth. The images were taken between 19:50 and 00:45 UTC. The animation was composed of monochrome images taken in different color filters at 30-second intervals for each frame, resulting in a slight color fringing for the Moon in each finished frame. Due to its position at Sun–Earth L1, DSCOVR will always see the Moon illuminated and will always see its far side when it passes in front of Earth.[36]

On 19 October 2015, NASA opened a new website to host near-live "Blue Marble" images taken by EPIC of Earth.[22] Twelve images are released each day, every two hours, showcasing Earth as it rotates on its axis.[37] The resolution of the images ranges from 10 to 15 km per pixel (6 to 9 mi/pixel), and the short exposure times renders points of starlight invisible.[37]

On 27 June 2019, DSCOVR was put into safe mode due to an anomaly with the laser gyroscope of the Miniature Inertial Measurement Unit (MIMU), part of the spacecraft's attitude control system.[38] Operators programmed a software patch that allows DSCOVR to operate without a laser gyroscope, using only the star tracker for angular rate information.[39] DSCOVR came out of the safe hold on 2 March 2020, and resumed normal operations.[40]

On 16 July 2025, DSCOVR suffered a software bus anomaly, which put it offline without an estimated date for recovery.[41] On 12 October 2025, the amateur-operated Dwingeloo Radio Observatory received signals again.[42], after which AMSAT-DL successfully downloaded EPIC images on 23 October 2025[43].

Picture Sequences

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "NOAA Satellite and Information Service: Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR)" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "DSCOVR: Deep Space Climate Observatory" (PDF). NOAA. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mellow, Craig (August 2014). "Al Gore's Satellite". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (10 February 2015). "SpaceX Scrubs Falcon 9's DSCOVR Launch (Again) Due to Winds". NBC News. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "DSCOVR completes its first year in deep space!". NOAA. 7 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Donahue, Bill (7 April 2011). "Who killed the Deep Space Climate Observatory?". Popular Science. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Leary, Warren (1 June 1999). "Politics Keeps a Satellite Earthbound". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ "Assessment of the Triana Mission, G-99-013, Final Reportwork=Office of Inspector General" (PDF). NASA. 10 September 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA's Triana Mission Scientific Evaluation Completed". Earth Observatory. NASA. 8 March 2000. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (2 March 2009). "Mothballed satellite sits in warehouse, waits for new life". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ a b c Clark, Stephen (21 February 2011). "NOAA taps DSCOVR satellite for space weather mission". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011.

- ^ a b Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle od Deep Space Exploration, 1958-2016 (PDF). NASA. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-62683-043-1. LCCN 2017058675.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Triana/DSCOVR Spacecraft Successfully Revived from Mothballs". NASA. 15 February 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Donahue, Bill (6 April 2011). "Who Killed The Deep Space Climate Observatory?". Popular Science. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Smith, R. C.; et al. (December 2011). Earth Science Instrument Refurbishment, Testing and Recalibration for the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR). American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting 2011. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. Vol. 2011. pp. A43G–03. Bibcode:2011AGUFM.A43G..03S.

- ^ Gore, Al (2009). "Chapter 17". Our Choice. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-734-7.

- ^ "Spacex awarded two EELV-class missions from the United States Air Force" (Press release). SpaceX. 5 December 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Leslie, John (10 September 2013). "DSCOVR Mission Moves Forward to 2015 Launch". NASA/NOAA.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Adams, Sam (20 January 2017). "Film review: Is Al Gore's An Inconvenient Sequel worthwhile?". BBC. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ "Spacecraft and Instruments". NOAA. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ The little satellite that could 2021 See diagram.

- ^ a b "DSCOVR: EPIC – Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera". NASA. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Phillips, Ari (4 February 2015). "A Sneak Peek at NASA's New Satellite That has Been 16 Years in the Making". ThinkProgress.

- ^ "DSCOVR Mission Hosts Two NASA Earth-Observing Instruments". NOAA. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (7 June 2015). "DSCOVR space weather sentinel reaches finish line". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ a b "NOAA Satellite and Information Service: Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR): Plasma-Magnetometer (PlasMag)" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Northon, Karen (20 July 2015). "NASA Captures "EPIC" Earth Image". NASA.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "DSCOVR: EPIC". NASA. 6 July 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "NOAA Satellite and Information Service: Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR): Enhanced Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC)" (PDF). NOAA. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NOAA Satellite and Information Service: Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR): National Institute of Standards and Technology Advanced Radiometer (NISTAR)" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jenner, Lynn (20 January 2015). "NOAA's DSCOVR NISTAR Instrument Watches Earth's "Budget"". NASA. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "DSCOVR - Satellite Missions". directory.eoportal.org. ESA. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ "NOAA's First Operational Satellite in Deep Space Reaches Final Orbit". NASA. 8 June 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Cresswell, Miriam (8 February 2015). "SpaceX DISCOVR launch scrubbed". Space Alabama. WAAYTV. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015.

- ^ "DSCOVR: Deep Space Climate Observatory". NOAA. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (5 August 2015). "Watch the moon transit the Earth". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (19 October 2015). "NASA to post new "blue marble" pictures every day". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (5 July 2019). "DSCOVR spacecraft in safe mode". SpaceNews.

- ^ "Software fix planned to restore DSCOVR". SpaceNews. 1 October 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "DSCOVR back in operation". SpaceNews. 3 March 2020.

- ^ "DSCOVR Processor Reset". 16 July 2025.

- ^ "DSCOVR signals received by Dwingeloo Radio Observatory".

- ^ "DSCOVR EPIC images downloaded by AMSAT-DL".

External links

[edit]- DSCOVR website at NOAA.gov

- DSCOVR at eoPortal.org

- EPIC global images at NASA.gov

Further reading

[edit]- National Research Council (March 2000). Review of Scientific Aspects of the NASA Triana Mission: Letter Report. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/9789. ISBN 978-0-309-13169-8.

- Harris, Melissa (15 July 2001). "Politics Puts $100 Million Satellite On Ice". Orlando Sentinel.

- Park, Robert L. (15 January 2006). "Scorched Earth". The New York Times. Opinion Editorial.

- Rebuttal: Pielke Jr., Roger A. (15 January 2006). "Re-Politicizing Triana". Center for Science and Technology Policy Research. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Donahue, Bill (6 April 2011). "Who Killed The Deep Space Climate Observatory?". Popular Science.

- Doody, Dave (28 July 2015). "DSCOVR's Halo". The Planetary Society.

Deep Space Climate Observatory

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Political Context

Conception as Triana

The Triana mission originated as a proposal in 1998 from then-Vice President Al Gore to NASA, envisioning an Earth-observing spacecraft stationed at the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point to enable continuous monitoring of the planet's sunlit hemisphere.[3] The concept drew inspiration from Apollo 8's 1968 Earthrise photographs, prompting Gore to advocate for a dedicated platform that would stream live, full-disk imagery of Earth, akin to viewing the Moon from space, to foster public awareness of global environmental dynamics.[9] Positioned approximately 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, the satellite would exploit the L1 vantage for uninterrupted views, avoiding the orbital limitations of low-Earth satellites that capture only partial glimpses.[1] Named after Rodrigo de Triana, the sailor who first sighted land during Christopher Columbus's 1492 voyage, the mission prioritized Earth science objectives, including real-time imaging to track weather systems, vegetation changes, and atmospheric phenomena with a targeted spatial resolution of about 10 km per pixel.[10] Initial plans called for a simple, cost-effective design featuring a wide-field camera for periodic full-Earth snapshots every 10-15 minutes, supplemented by basic radiometers to measure reflected sunlight and assess planetary albedo variations relevant to climate studies.[4] NASA evaluated the scientific merits through peer review, confirming feasibility for deployment via a low-cost launch, with preliminary development advancing under the Earth Science Enterprise despite debates over its novelty relative to existing geostationary observations.[1]Initial Controversies and Cancellation

The Triana mission, proposed by Vice President Al Gore in March 1998, faced immediate political scrutiny due to its association with Gore's environmental advocacy and its proposed continuous imaging of Earth from the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, which critics derided as a publicity stunt rather than a scientifically essential endeavor.[11][10] Republicans in Congress, viewing it as a partisan project amid Gore's 2000 presidential campaign, labeled it "Gore-sat" and questioned its $100 million cost and utility, arguing it prioritized symbolic imagery over pressing NASA priorities like human spaceflight.[12][13] In May 1999, House Republicans removed Triana's funding from a $41 billion NASA authorization bill, citing concerns over its scientific justification and potential as environmental propaganda, despite Democratic defenses that emphasized its role in monitoring global climate and weather patterns.[10][13] A subsequent review by the National Academy of Sciences in early 2000 affirmed the mission's technical feasibility and potential contributions to Earth science data collection, including full-disk imaging for climate studies, which provided some defense against claims of frivolity but failed to overcome entrenched partisan opposition.[12] Following the 2000 U.S. presidential election and the transition to the George W. Bush administration, Triana's prospects dimmed further amid shifting federal priorities toward defense and space exploration over Earth observation initiatives linked to the prior administration.[14] In 2001, NASA formally canceled the mission after the spacecraft had completed environmental testing and partial integration of instruments, citing budgetary constraints and the program's political baggage, leading to its indefinite storage in a Delaware warehouse at a cost of approximately $1 million annually for preservation.[15][12] Efforts to rebrand it as the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) in 2003 aimed to refocus on space weather monitoring but did not immediately revive the project, as ongoing debates highlighted skepticism regarding its value relative to alternatives like the aging Advanced Composition Explorer satellite.[9][14]Mission Revival and Redesign

Storage Period and Reactivation

Following its cancellation in November 2001, the Triana spacecraft—later redesignated DSCOVR—was placed in environmentally controlled storage at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland to preserve its components and prevent degradation.[16][4] By 2003, it had been secured in a white metal crate within a clean room in Building 29, where it remained largely untouched for over seven years amid debates over mission viability and funding.[17] Storage costs, initially estimated by some reports at approximately $1 million annually, were later clarified by NASA officials as lower, reflecting minimal maintenance needs for the inert hardware.[15] In 2008, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), in collaboration with the U.S. Air Force, initiated reactivation efforts by removing the spacecraft from storage for comprehensive testing to assess its structural integrity, electronic systems, and propulsion readiness after prolonged inactivity.[4][16] These evaluations confirmed the satellite's overall condition remained viable, with no major failures attributable to storage, though some thermal coatings and components required inspection and minor refurbishment to mitigate potential environmental degradation.[16] Congress subsequently allocated $9 million in fiscal year 2009 to support recertification, enabling NASA to proceed with updates for a repurposed deep-space mission focused on solar wind monitoring at the L1 Lagrange point.[18] Reactivation involved rigorous ground-based simulations, software validations, and integration of space weather instruments, transforming the original Earth-viewing prototype into the operational DSCOVR platform without necessitating full redesign.[17] By 2014, post-reactivation preparations culminated in flight certification, paving the way for launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket on February 11, 2015, after which it achieved its halo orbit and began commissioning.[4] This revival demonstrated the feasibility of long-term storage for high-value space hardware, though it highlighted challenges in preserving sensitive avionics over extended periods without active power or thermal cycling.[16]Shift to Space Weather Focus

Following its cancellation in 2001, the Triana spacecraft underwent a name change to Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) in 2003, aiming to reframe its purpose amid ongoing debates, though it remained in storage at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center until 2008.[9] The revival effort, authorized by a NASA reauthorization bill signed by President George W. Bush in October 2008, marked a pivotal reorientation toward operational space weather monitoring, driven by the need to replace NASA's aging Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) satellite, launched in 1997 and operating beyond its design life.[17] [3] In January 2009, a NOAA-commissioned study known as the Serotine Report estimated refurbishment costs at $47.3 million and explicitly recommended repurposing the existing hardware for real-time solar wind observations, positioning DSCOVR as NOAA's first deep-space asset for space weather forecasting.[17] This shift emphasized the spacecraft's L1 Lagrange point placement—approximately 1 million miles sunward of Earth—for upstream monitoring of solar activity, enabling 15- to 60-minute advance warnings of geomagnetic storms capable of disrupting power grids, satellites, telecommunications, and GPS systems.[3] The primary instruments for this role, the Plasma-Magnetometer (PlasMag) suite—including solar wind electron sensors, proton/alpha particle sensors, and a magnetometer—were part of the original design but redefined as core operational tools, with data relayed continuously to NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center for alerts and forecasts.[1] [17] Earth-facing instruments like the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) and National Institute of Standards and Technology Advanced Radiometer (NISTAR), originally central to continuous planetary views, were retained for secondary applications such as daily atmospheric and climate monitoring but operated at reduced cadence (4–6 images per day, with processing delays) to prioritize space weather utility over real-time Earth broadcasting.[17] [9] The redesign rationale addressed earlier criticisms of the mission's Earth-observation emphasis, which had been labeled politically motivated, by aligning it with practical national security and economic needs for solar storm prediction, as evidenced by ACE's limitations in providing reliable, high-cadence data.[17] No significant new hardware was added; refurbishment focused on recertification, software updates, and integration with NOAA and U.S. Air Force operations, costing approximately $97 million including launch preparations.[1] This evolution transformed DSCOVR from a controversial Earth-science demonstrator into a joint NASA-NOAA-U.S. Air Force mission succeeding ACE, with space weather as its operational cornerstone upon commissioning in 2015.[3]Spacecraft and Instruments

Overall Design and Capabilities

The Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) is built on NASA's SMEX-Lite spacecraft bus, developed by the Goddard Space Flight Center. This three-axis stabilized platform employs reaction wheels and a star tracker for precise attitude control, enabling continuous orientation toward the Sun and Earth from the L1 Lagrange point. The bus dimensions are approximately 137 cm by 187 cm, with a launch mass of 570 kg.[19][1] Propulsion is handled by a monopropellant hydrazine blowdown system, including a single tank, ten 4.5 N thrusters, and associated valves and transducers, supporting orbit insertion, station-keeping, and momentum dumping maneuvers.[1] The design facilitates a nominal mission lifetime of five years, with power generation and thermal management optimized for the deep-space environment at approximately 1.5 million km from Earth.[1] DSCOVR's core capabilities center on real-time space weather monitoring, measuring solar wind speed, density, direction, and interplanetary magnetic field strength to provide 15- to 60-minute warnings of coronal mass ejections that could trigger geomagnetic storms affecting power grids, satellites, and communications.[2] Secondary Earth science functions include full-disk imaging of the sunlit hemisphere and radiometric observations of ozone, aerosols, clouds, vegetation, and UV radiation, leveraging the L1 vantage for unique global views unobscured by atmospheric interference.[5] This dual-role architecture ensures operational continuity for NOAA's space weather suite while contributing to broader heliophysics and climatology datasets.[5]Key Instruments

The Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) carries three primary instrument suites: the Plasma-Magnetometer (PlasMag) for space weather monitoring, the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) for multispectral Earth imaging, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology Advanced Radiometer (NISTAR) for radiation budget measurements.[3] These instruments support the mission's core objectives of solar wind observation and secondary Earth science data collection from the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, approximately 1.5 million kilometers from Earth.[1] PlasMag consists of two Faraday cup electrostatic analyzers and a triaxial fluxgate magnetometer. The Faraday cups measure in-situ solar wind plasma parameters, including density, bulk velocity (typically 300–800 km/s), and temperature for protons and helium ions (alpha particles), with a time resolution of 1 minute.[20] The magnetometer detects interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) strength and orientation, with sensitivities down to 0.008 nT/√Hz in the 0.001–10 Hz range.[21] Together, these enable real-time alerts for geomagnetic storms, providing up to 60 minutes of advance warning by detecting coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and high-speed solar wind streams as they exit the corona.[22] EPIC is a fixed, nadir-pointing 30-cm aperture Cassegrain telescope equipped with a 10-channel spectroradiometer spanning 317–780 nm (ultraviolet to near-infrared), using a 2048 × 2048 pixel CCD detector.[6] It captures full-disk images of the sunlit Earth every 65–110 minutes, with a spatial resolution of about 8–28 km per pixel depending on wavelength, enabling observations of atmospheric dynamics, ozone distribution, aerosol optical depth, cloud properties, vegetation indices, and vegetation fire detection.[23] The instrument's design supports continuous monitoring without moving parts, producing over 10 terabytes of data annually for climate and environmental studies.[24] NISTAR functions as a four-channel active-cavity radiometer, measuring Earth's broadband radiances in ultraviolet-visible (0.22–0.3 μm), visible-near infrared (0.7–2.5 μm), total solar reflectance (0.2–>100 μm), and infrared thermal emission (>1 μm).[25] Positioned to view the entire illuminated Earth disk, it quantifies the planetary radiation budget with an absolute accuracy of 1% or better, calibrated against NIST standards, and detects variations in outgoing longwave radiation and reflected shortwave flux linked to cloud cover, sea ice extent, and energy imbalances.[26] Data from NISTAR contribute to validating Earth energy budget models and tracking decadal-scale climate trends.[24]Launch and Deployment

Pre-Launch Preparations and Delays

Following its reactivation and refurbishment at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) spacecraft was transported by truck to the Astrotech Space Operations payload processing facility in Titusville, Florida, on November 21, 2014, initiating final pre-launch preparations including environmental testing, system verifications, and propellant loading with hydrazine fuel.[27][1] These activities, contracted to Astrotech since October 2013, ensured spacecraft readiness for integration with the U.S. Air Force-procured SpaceX Falcon 9 v1.1 launch vehicle at Space Launch Complex 40 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.[28] By February 2, 2015, processing in Astrotech's Building 1 high bay was nearing completion, with mating to the Falcon 9 occurring on February 3.[29][30] A pre-launch readiness review and press conference followed on February 7, confirming the payload adapter integration and overall vehicle configuration for the mission to the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point.[31] The launch timeline faced multiple disruptions stemming from upstream scheduling constraints and on-site technical issues. In December 2014, a delay in Orbital Sciences' Antares resupply mission to the International Space Station—caused by an October explosion—created a ripple effect, postponing DSCOVR's liftoff by several weeks from mid-January targets to no earlier than January 29, 2015, to accommodate range availability and orbital insertion windows optimized for minimal velocity adjustments to L1.[32][33] Further slips pushed the window into February due to these cascading effects and coordination among NOAA, NASA, and the Air Force. Immediate pre-liftoff delays compounded these setbacks. On February 8, 2015, a malfunction in an Air Force Eastern Range tracking radar halted countdown activities, deferring the attempt to the next day.[34] The February 9 window was scrubbed due to unresolved radar issues, rescheduling for February 10.[35] High winds exceeding safety limits prompted another scrub on February 10 with only 12 minutes remaining in the countdown.[36][37] Falcon 9 fueling with RP-1 kerosene and liquid oxygen proceeded successfully on February 10 in anticipation of the subsequent attempt, validating propulsion systems.[38] These delays, while frustrating operational timelines, allowed additional verifications without compromising the spacecraft's post-storage integrity.Orbital Insertion and Commissioning

The Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) was launched on February 11, 2015, at 23:03 UTC aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 v1.1 rocket from Space Launch Complex 40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.[1] Approximately 35 minutes after liftoff, the spacecraft separated from the rocket's upper stage and was placed on a high-energy transfer trajectory toward the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, approximately 1.5 million kilometers from Earth.[39] Initial post-separation operations included transition to Sun Acquisition mode and calibration of the Miniature Inertial Measurement Unit (MIMU) on February 12, 2015.[39] A mid-course correction maneuver (MCC-1) was executed on February 13, 2015, at 07:00 UTC, lasting 37 seconds and imparting a delta-V of 0.49 m/s to refine the trajectory.[39] The spacecraft reached the halfway point of its journey, about 0.8 million kilometers from Earth, by February 24, 2015.[1] On February 15, 2015, the instrument boom was deployed in a 1-minute, 10-second operation to position sensors for plasma and magnetometer measurements.[39] Calibration of the Plasma and Magnetometer (PlasMag) instrument occurred on March 10, 2015, over 2 hours and 10 minutes.[39] Early operations addressed anomalies, such as a Deep Space Station (DSS) issue resolved by May 21, 2015, using Coarse Sun Sensors (CSSs), and a Star Tracker (ST) Line-of-Sight (LIS) anomaly similarly mitigated.[39] DSCOVR arrived at the L1 point and performed its Lissajous Orbit Insertion (LOI) maneuver on June 7, 2015, at 17:00 UTC (mission day 158), consisting of a 4-hour, 27-minute hydrazine thruster burn divided into two segments with attitude bias corrections.[39] This inserted the spacecraft into a Lissajous orbit around L1, enabling continuous monitoring of solar wind upstream of Earth.[40] The LOI positioned DSCOVR for stable operations, avoiding the Sun-Earth line during initial phases to maximize communication windows.[41] Commissioning activities commenced immediately post-LOI, with instrument checkouts completed by June 8, 2015.[1] The Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) began imaging on June 9, 2015, capturing initial full-disk Earth images by June 13, 2015, and publicly releasing data on July 20, 2015.[39] Space weather instruments, including those for solar wind plasma and magnetic fields, were activated and calibrated during this phase to support real-time forecasting.[1] NOAA assumed full operational command on October 28, 2015, marking the transition from commissioning to routine science operations.[1]Operational History

Primary Operations at L1 Point

The Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) reached the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point in June 2015 following orbital insertion maneuvers, including mid-course corrections and Lissajous orbit adjustments, after its launch on February 11, 2015.[19] Positioned approximately 1.5 million kilometers from Earth toward the Sun, the spacecraft maintains a Lissajous orbit that provides an uninterrupted view of incoming solar activity.[5] This vantage enables continuous monitoring of the solar wind, arriving at L1 up to an hour before reaching Earth, facilitating early space weather warnings.[42] DSCOVR's core operations at L1 center on real-time solar wind observations using its magnetometer for interplanetary magnetic field measurements and Faraday cup instruments for plasma parameters such as velocity, density, and temperature.[43] These data streams support NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center in forecasting geomagnetic storms and radiation hazards, with DSCOVR assuming primary operational status for L1 solar wind data on July 27, 2016, succeeding the Advanced Composition Explorer mission.[44] [2] Continuous data transmission to ground stations occurs via NASA's Deep Space Network, with NOAA taking full command on October 28, 2015.[45] Orbit maintenance involves thruster-based station-keeping maneuvers every 30 to 90 days to counteract perturbations and preserve the unstable Lissajous trajectory, minimizing propellant use through optimized Solar Exclusion Zone procedures implemented from October 2020.[19] [46] As of 2025, these operations continue reliably, providing essential inputs for global space weather services amid Solar Cycle 25.[47]Earth Observation Activities

The Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) on DSCOVR conducts Earth observation by capturing multispectral images of the sunlit disk of Earth from the L1 Lagrange point, approximately 1.5 million kilometers from Earth.[6] EPIC utilizes a 2048x2048 pixel charge-coupled device (CCD) detector paired with a 30-cm aperture telescope to acquire ten narrow-band spectral images across ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths ranging from 317 nm to 780 nm.[6] These observations occur at intervals of approximately every two hours during daylight hours, enabling continuous monitoring of the entire illuminated hemisphere from sunrise to sunset.[48] [49] EPIC's primary operational activity involves generating daily natural color composites and derived environmental products, including aerosol indices, cloud fraction, cloud height, and atmospheric trace gases such as ozone (O3) and sulfur dioxide (SO2).[50] Vegetation monitoring is supported through products like the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Leaf Area Index (LAI), and Sunlit Leaf Area Index (SLAI), which track diurnal variations in photosynthetic activity and canopy structure.[51] Level 1A and 1B data products provide calibrated radiance images with geolocation metadata in HDF5 format, while Level 2 products deliver geophysical parameters such as aerosol optical depth and cloud properties essential for climate and atmospheric studies.[52] [53] Since commissioning in July 2015, EPIC has facilitated observations of dynamic Earth phenomena, including cloud dynamics, aerosol distributions over oceans and continents, polar ice extent via reflected sunlight detection, and rare events such as lunar transits and solar eclipses visible across the full disk.[54] [55] [56] These activities complement geostationary and low-Earth orbit satellites by offering a unique synoptic view, aiding in the validation of global models for weather, air quality, and vegetation health without the limitations of regional coverage.[49] Data from EPIC are archived and distributed by NASA’s Atmospheric Science Data Center, supporting research into atmospheric composition changes and surface reflectance variations.[57]Anomalies and Recovery

Following commissioning at the L1 Lagrange point on June 7, 2015, the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) experienced spurious reboots that reset the spacecraft and placed it into safe hold mode multiple times.[44] These events, occurring soon after arrival, stemmed from unidentified software or hardware triggers but did not prevent eventual stabilization and transition to nominal operations by late July 2015, when NOAA assumed full flight control from NASA Goddard.[44] [19] On June 27, 2019, DSCOVR entered safehold mode due to a technical fault in its attitude determination and control system, halting data transmission for space weather monitoring and Earth imaging.[58] The issue involved navigation performance degradation, potentially linked to the miniature inertial measurement unit (MIMU) or star tracker malfunctions, interrupting real-time solar wind observations for over three months.[59] [44] Operations teams from NOAA, NASA, and contractors diagnosed the problem remotely and developed a targeted flight software patch, with testing yielding positive results by September 2019; the fix was uploaded and verified, restoring full functionality by March 2, 2020, after approximately nine months of downtime.[59] [60] During the outage, the NASA Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) spacecraft provided backup solar wind data to maintain forecasting continuity.[61] A software bus anomaly on July 15, 2025, at 1742Z necessitated a processor reset, rendering DSCOVR offline and suspending data feeds without an initial recovery timeline.[62] [63] This event disrupted primary space weather inputs, forcing reliance on ACE for solar wind monitoring amid heightened Solar Cycle 25 activity.[63] As of late September 2025, no official restoration had been announced by NOAA or NASA.[64]Scientific Contributions

Space Weather Monitoring and Forecasting

The Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) serves as NOAA's primary operational satellite for real-time solar wind monitoring from the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, approximately 1.5 million kilometers sunward of Earth, providing advance data on solar wind conditions to support space weather alerts and forecasts.[3] Positioned at L1 since June 2015, DSCOVR delivers measurements with a lead time of 15 to 60 minutes before solar wind disturbances reach Earth's magnetosphere, enabling predictions of geomagnetic storms that could disrupt power grids, satellite operations, and communications.[2] Its data have been validated as comparable in accuracy to predecessor missions like ACE, with statistical analyses showing high correlation in solar wind parameters such as velocity and magnetic field orientation.[44] DSCOVR's space weather instrumentation includes two Faraday cup sensors within the Plasma-Magnetometer (PlasMag) system, which measure the bulk properties of solar wind ions—specifically protons and alpha particles—including density (typically 1–10 particles per cubic centimeter), velocity (300–800 km/s), and temperature—along with flow direction.[22] [65] A triaxial fluxgate magnetometer complements these by recording the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) vector, with components Bx, By, Bz resolved to within 0.1 nT accuracy, critical for assessing southward Bz orientations that facilitate magnetic reconnection with Earth's field.[47] These instruments operate continuously, sampling at 1-minute cadences for plasma and 0.25-second for magnetic fields, with data downlinked in real-time via the Deep Space Network to NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC).[66] In forecasting applications, SWPC integrates DSCOVR observations into empirical models and numerical simulations, such as the WSA-ENLIL model for coronal mass ejection (CME) propagation, to issue geomagnetic storm warnings (e.g., G1–G5 scales) when solar wind speeds exceed 500 km/s or IMF Bz turns strongly negative.[67] For instance, during the September 2017 solar events, DSCOVR data enabled timely alerts for enhanced radiation and auroral activity, supporting mitigation for high-altitude aviation and GPS users.[47] The mission's real-time data portal disseminates processed products, including 1-hour forecasts of storm probabilities, sustaining U.S. space weather readiness since assuming operational primacy from ACE in 2016.[43] As of 2022, validation studies confirm DSCOVR's solar wind archive supports reliable operational forecasting with minimal gaps, though redundancy with ACE persists for data assurance.[44]Earth Science Data Outputs

The Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) instrument on the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) produces Earth science data through multispectral imaging of the entire sunlit Earth disk, acquired approximately every 65 to 110 minutes from the L1 Lagrange point.[6] These observations utilize 10 narrow spectral channels spanning 317 to 780 nm, enabling the retrieval of geophysical parameters such as atmospheric composition, cloud dynamics, and surface characteristics.[6] Calibrated Level 1B radiance data serve as input for higher-level products, which are generated using algorithms validated against ground-based and other satellite measurements.[53] Key Level 2 products include aerosol optical depth and spectral absorption indices, derived primarily from ultraviolet and visible channels to quantify particulate loading and type across the globe.[4] Ozone products provide total column amounts and vertical profiles, leveraging absorption features in the ultraviolet spectrum for monitoring stratospheric and tropospheric distributions.[68] Cloud properties encompass effective height, top pressure, optical thickness, and phase, obtained via oxygen A- and B-band measurements that exploit rotational Raman scattering for height retrieval.[69] Vegetation data outputs feature biophysical parameters like leaf area index and sunlit fraction, supporting assessments of photosynthetic activity and land cover changes.[70] These datasets facilitate unique applications in Earth system science, such as diurnal cycle analysis of aerosols and clouds without the regional limitations of geostationary satellites, and global monitoring of phenomena like volcanic ash dispersion or biomass burning impacts.[71] Publicly available RGB composite images and select products are hosted on the EPIC science portal, while comprehensive Level 2 and gridded Level 3 data are archived at NASA's Atmospheric Science Data Center (ASDC) for research access.[4] Derived products, including erythemal UV irradiance and sulfur dioxide plumes, further extend utility for environmental and health-related studies.[49]