Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Flavonoid

View on Wikipedia

Flavonoids (or bioflavonoids; from the Latin word flavus, meaning yellow, their color in nature) are a class of polyphenolic secondary metabolites found in plants. Blackberry, black currant, chokeberry, and red cabbage are examples of plants with rich contents of flavonoids. In plant biology, flavonoids fulfill diverse functions, including attraction of pollinating insects, antioxidant protection against ultraviolet light, deterrence of environmental stresses and pathogens, and regulation of cell growth.[1][2]

Although commonly consumed in human and animal plant foods and in dietary supplements, flavonoids are not considered to be nutrients or biological antioxidants essential to body functions, and have no established effects on human health or prevention of diseases.[1][2][3]

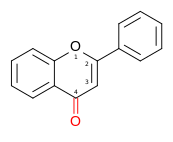

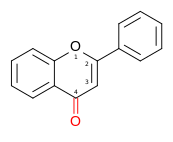

Chemically, flavonoids have the general structure of a 15-carbon skeleton, which consists of two phenyl rings (A and B) and a heterocyclic ring (C, the ring containing the embedded oxygen).[1][4] This carbon structure can be abbreviated C6-C3-C6. According to the IUPAC nomenclature, they can be classified into flavonoids or bioflavonoids, isoflavonoids, derived from 3-phenylchromen-4-one (3-phenyl-1,4-benzopyrone) structure, and neoflavonoids, derived from 4-phenylcoumarin (4-phenyl-1,2-benzopyrone) structure.[5]

As ketone-containing compounds, the three flavonoid classes are grouped as anthoxanthins (flavones and flavonols).[1] This class was the first to be termed bioflavonoids. The terms flavonoid and bioflavonoid have also been more loosely used to describe non-ketone polyhydroxy polyphenol compounds, which are more specifically termed flavanoids.[4]

History

[edit]In the 1930s, Albert Szent-Györgyi and other scientists discovered that vitamin C alone was not as effective at preventing scurvy as the crude yellow extract from oranges, lemons or paprika. They attributed the increased activity of this extract to the other substances in this mixture, which they referred to as "citrin" (referring to citrus) or "vitamin P" (a reference to its effect on reducing the permeability of capillaries). The substances in question (hesperidin, eriodictyol, hesperidin methyl chalcone and neohesperidin) were later shown not to fulfil the criteria of a vitamin,[6] so that the term "vitamin P" is now obsolete.[7]

-

Molecular structure of the flavone backbone (2-phenyl-1,4-benzopyrone)

-

Isoflavan structure

-

Neoflavonoids structure

Biosynthesis

[edit]Flavonoids are secondary metabolites synthesized mainly by plants. The general structure of flavonoids is a fifteen-carbon skeleton, containing two benzene rings connected by a three-carbon linking chain.[1] Therefore, they are depicted as C6-C3-C6 compounds. Depending on the chemical structure, degree of oxidation, and unsaturation of the linking chain (C3), flavonoids can be classified into different groups, such as anthocyanidins, flavonols, flavanones, flavan-3-ols, flavanonols, flavones, and isoflavones.[1] Chalcones, also called chalconoids, although lacking the heterocyclic ring, are also classified as flavonoids. Furthermore, flavonoids can be found in plants in glycoside-bound and free aglycone forms. The glycoside-bound form is the most common flavone and flavonol form consumed in the diet.[1]

Functions in plants

[edit]Numbering some 5,000 individual compounds, flavonoids are widely distributed in plants, fulfilling numerous functions, including attraction of pollinating insects, deterrence of environmental stresses, and regulation of cell growth.[1] They are the most important plant pigments for flower coloration, producing yellow, red or blue pigmentation in petals evolved to attract pollinators.[1]

In higher plants, they are involved in antioxidant roles in plant cells, filtration of ultraviolet light, symbiotic nitrogen fixation, and defense against pathogens and pests. They also act as plant chemical messengers, physiological regulators, and cell cycle inhibitors.[1][2] Flavonoids secreted by the root of their host plant help Rhizobia in the infection stage of their symbiotic relationship with legumes like peas, beans, clover, and soy. Rhizobia living in soil are able to sense the flavonoids and this triggers the secretion of Nod factors, which in turn are recognized by the host plant and can lead to root hair deformation and several cellular responses such as ion fluxes and the formation of a root nodule. In addition, some flavonoids have inhibitory activity against organisms that cause plant diseases, e.g. Fusarium oxysporum.[8]

Subgroups

[edit]Flavonoids have been classified according to their chemical structure, and are usually subdivided into the following subgroups:[1][9]

Anthocyanidins

[edit]

Anthocyanidins are the aglycones of anthocyanins; they use the flavylium (2-phenylchromenylium) ion skeleton.[1]

- Examples: cyanidin, delphinidin, malvidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, petunidin

Anthoxanthins

[edit]Anthoxanthins are divided into two groups:[10]

Group Skeleton Examples Description Functional groups Structural formula 3-hydroxyl 2,3-dihydro Flavone 2-phenylchromen-4-one ✗ ✗

Luteolin, Apigenin, Tangeritin Flavonol

or

3-hydroxyflavone3-hydroxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one ✓ ✗

Quercetin, Kaempferol, Myricetin, Fisetin, Galangin, Isorhamnetin, Pachypodol, Rhamnazin, Pyranoflavonols, Furanoflavonols,

Flavanones

[edit]| Group | Skeleton | Examples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Functional groups | Structural formula | |||

| 3-hydroxyl | 2,3-dihydro | ||||

| Flavanone | 2,3-dihydro-2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✗ | ✓ |

|

Hesperetin, Naringenin, Eriodictyol, Homoeriodictyol |

Flavanonols

[edit]| Group | Skeleton | Examples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Functional groups | Structural formula | |||

| 3-hydroxyl | 2,3-dihydro | ||||

| Flavanonol or 3-Hydroxyflavanone or 2,3-dihydroflavonol |

3-hydroxy-2,3-dihydro-2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Taxifolin (or Dihydroquercetin), Dihydrokaempferol |

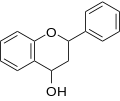

Flavans

[edit]

Include flavan-3-ols (flavanols), flavan-4-ols, and flavan-3,4-diols.

| Skeleton | Name |

|---|---|

|

Flavan-3-ol (flavanol) |

|

Flavan-4-ol |

|

Flavan-3,4-diol (leucoanthocyanidin) |

- Flavan-3-ols (flavanols)

- Flavan-3-ols use the 2-phenyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-chromen-3-ol skeleton

- Examples: catechin (C), gallocatechin (GC), catechin 3-gallate (Cg), gallocatechin 3-gallate (GCg), epicatechins (EC), epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin 3-gallate (ECg), epigallocatechin 3-gallate (EGCg)

- Thearubigin

- Proanthocyanidins are dimers, trimers, oligomers, or polymers of the flavanols

Isoflavonoids

[edit]- Isoflavonoids

- Isoflavones use the 3-phenylchromen-4-one skeleton (with no hydroxyl group substitution on carbon at position 2)

Dietary sources

[edit]

Flavonoids (specifically flavanoids such as the catechins) are "the most common group of polyphenolic compounds in the human diet and are found ubiquitously in plants".[1][2][11] Flavonols, the original bioflavonoids such as quercetin, are also found ubiquitously, but in lesser quantities. The widespread distribution of flavonoids, their variety and their relatively low toxicity compared to other active plant compounds (for instance alkaloids) mean that many animals, including humans, ingest significant quantities in their diet.[1][2][3]

Foods with a high flavonoid content include blackberries, black currants, parsley, onions, blueberries and strawberries, red cabbage, black tea, dark chocolate, and citrus fruits.[1][2][12] One study found high flavonoid content in buckwheat.[13]

Citrus flavonoids include hesperidin (a glycoside of the flavanone hesperetin), quercitrin, rutin (two glycosides of quercetin, and the flavone tangeritin.[1] The flavonoids are less concentrated in the pulp than in the peels (for example, 165 versus 1156 mg/100 g in pulp versus peel of satsuma mandarin, and 164 vis-à-vis 804 mg/100 g in pulp versus peel of clementine).[14]

Peanut (red) skin contains significant polyphenol content, including flavonoids.[15][16]

Dietary intake

[edit]

Food composition data for flavonoids were provided by the USDA database on flavonoids.[12] In the United States NHANES survey, mean flavonoid intake was 190 mg per day in adults, with flavan-3-ols as the main contributor.[18] In the European Union, based on data from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), mean flavonoid intake was 140 mg/d, although there were considerable differences among individual countries.[17] The main type of flavonoids consumed in the EU and USA were flavan-3-ols (80% for USA adults), mainly from tea or cocoa in chocolate, while intake of other flavonoids was considerably lower.[1][17][18]

Non-nutrient status in humans

[edit]Flavonoids are not considered as nutrients because there is no evidence for a cause-and-effect on specific cells or organs in vivo.[1][2][3] The European Food Safety Authority determined that dietary flavonoids do not have the characteristics of nutrients, as they do not reduce disease risk, affect physiological or behavioral functions, improve satiety, contribute calories, or influence the growth and development of children.[3] The bioavailability of flavonoids is low because they are extensively metabolized in the stomach, small intestine and liver, and are rapidly excreted.[1][2]

In the United States, flavonoids and other polyphenols are not included on the FDA list of nutrients.[19]

Metabolism and excretion

[edit]Flavonoids are poorly absorbed in the human body (less than 5%), then are quickly metabolized into smaller fragments with unknown properties, and rapidly excreted.[1][2][20][21][22] Flavonoids have negligible antioxidant activity in the body, and the increase in antioxidant capacity of blood seen after consumption of flavonoid-rich foods is not caused directly by flavonoids, but by production of uric acid resulting from flavonoid depolymerization and excretion.[1][2][3] Microbial metabolism is a major contributor to the overall metabolism of dietary flavonoids.[1][2][23]

Safety

[edit]Likely due to the low bioavailability and rapid metabolism and excretion of flavonoids, there are no safety concerns and no adverse effects associated with high dietary intakes of flavonoids from plant foods.[1]

Regulatory status

[edit]Due to the absence of proof for flavonoid health effects in clinical research, neither the United States FDA nor the European Food Safety Authority has approved any flavonoids as prescription drugs.[1][20][24][25]

The FDA has warned numerous dietary supplement and food manufacturers, including Unilever, producer of Lipton tea in the U.S., about illegal advertising and misleading health claims regarding flavonoids, such as that they lower cholesterol or relieve pain.[26][27]

From 2020 to 2023, the FDA issued 11 warning letters to American manufacturers of flavonoid dietary supplements for false advertising of health claims and illegal misbranding of products.[28]

Research

[edit]Antioxidant research

[edit]Although flavonoids inhibit free radical activity in vitro, high dietary intakes in humans would be 100 to 1,000 times less than circulating concentrations of dietary and endogenous antioxidants, such as vitamin C, glutathione, and uric acid.[1][2] Further, after digestion and metabolism in the body, flavonoid derivatives would have lower antioxidant activity than the parent flavonoid, rendering the smaller flavonoid metabolite with negligible antioxidant function.[1][2][3]

Clinical research

[edit]Although numerous preliminary clinical studies have been conducted to assess the potential for dietary flavonoid intake to affect disease risk, research has been inconclusive due to limitations of experimental design and absence of cause-and-effect evidence.[1][2][3]

Inflammation

[edit]Inflammation has been implicated as a possible origin of numerous local and systemic diseases, such as cancer,[29] cardiovascular disorders,[30] diabetes mellitus,[31] and celiac disease.[32] There is no clinical evidence that dietary flavonoids affect any of these diseases.[1]

Cancer

[edit]Clinical studies investigating the relationship between flavonoid consumption and cancer prevention or development are conflicting for most types of cancer, probably because most human studies have weak designs, such as a small sample size.[1][33] There is little evidence to indicate that dietary flavonoids affect human cancer risk in general.[1]

Cardiovascular diseases

[edit]Although no significant association has been found between flavan-3-ol intake and cardiovascular disease mortality, clinical trials have shown improved endothelial function and reduced blood pressure (with a few studies showing inconsistent results).[1] Reviews of cohort studies in 2013 found that the studies had too many limitations to determine a possible relationship between increased flavonoid intake and decreased risk of cardiovascular disease, although a trend for an inverse relationship existed.[1][34]

In 2013, the EFSA decided to permit health claims that 200 mg/day of cocoa flavanols "help[s] maintain the elasticity of blood vessels."[35][36] The FDA followed suit in 2023, stating that there is "supportive, but not conclusive" evidence that 200 mg per day of cocoa flavanols can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. This is greater than the levels found in typical chocolate bars, which can also contribute to weight gain, potentially harming cardiovascular health.[37][38]

Synthesis, detection, quantification, and semi-synthetic alterations

[edit]Color spectrum

[edit]Flavonoid synthesis in plants is induced by light color spectrums at both high and low energy radiations. Low energy radiations are accepted by phytochrome, while high energy radiations are accepted by carotenoids, flavins, cryptochromes in addition to phytochromes. The photomorphogenic process of phytochrome-mediated flavonoid biosynthesis has been observed in Amaranthus, barley, maize, Sorghum and turnip. Red light promotes flavonoid synthesis.[39]

Availability through microorganisms

[edit]Research has shown production of flavonoid molecules from genetically engineered microorganisms.[40][41]

Tests for detection

[edit]Shinoda test

[edit]Four pieces of magnesium filings are added to the ethanolic extract followed by few drops of concentrated hydrochloric acid. A pink or red colour indicates the presence of flavonoid.[42] Colours varying from orange to red indicated flavones, red to crimson indicated flavonoids, crimson to magenta indicated flavonones.

Sodium hydroxide test

[edit]About 5 mg of the compound is dissolved in water, warmed, and filtered. 10% aqueous sodium hydroxide is added to 2 ml of this solution. This produces a yellow coloration. A change in color from yellow to colorless on addition of dilute hydrochloric acid is an indication for the presence of flavonoids.[43]

p-Dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde test

[edit]A colorimetric assay based upon the reaction of A-rings with the chromogen p-dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde (DMACA) has been developed for flavanoids in beer that can be compared with the vanillin procedure.[44]

Quantification

[edit]Lamaison and Carnet have designed a test for the determination of the total flavonoid content of a sample (AlCI3 method). After proper mixing of the sample and the reagent, the mixture is incubated for ten minutes at ambient temperature and the absorbance of the solution is read at 440 nm. Flavonoid content is expressed in mg/g of quercetin.[45][46]

Semi-synthetic alterations

[edit]Immobilized Candida antarctica lipase can be used to catalyze the regioselective acylation of flavonoids.[47]

See also

[edit]- Phytochemical

- List of antioxidants in food

- List of phytochemicals in food

- Phytochemistry

- Secondary metabolites

- Homoisoflavonoids, related chemicals with a 16 carbons skeleton

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af "Flavonoids". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. 2025. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hollman PC, Cassidy A, Comte B, et al. (May 2011). "The biological relevance of direct antioxidant effects of polyphenols for cardiovascular health in humans is not established". The Journal of Nutrition. 141 (5): 989S – 1009S. doi:10.3945/jn.110.131490. PMID 21451125.

- ^ a b c d e f g Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies, European Food Safety Authority (8 April 2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to: flavonoids and ascorbic acid in fruit juices, including berry juices (ID 1186); flavonoids from citrus (ID 1471); flavonoids from Citrus paradisi Macfad. (ID 3324, 3325); flavonoids (ID 1470, 1693, 1920); flavonoids in cranberry juice (ID 1804); carotenoids (ID 1496, 1621, 1622, 1796); polyphenols (ID 1636, 1637, 1640, 1641, 1642, 1643); rye bread (ID 1179); protein hydrolysate (ID 1646); carbohydrates with a low/reduced glycaemic load (ID 476, 477, 478, 479, 602) and carbohydrates which induce a low/reduced glycaemic response (ID 727, 1122, 1171); alfalfa (ID 1361, 2585, 2722, 2793); caffeinated carbohydrate‐containing energy drinks (ID 1272); and soups (ID 1132, 1133) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006". EFSA Journal. 9 (4). doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2082.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b de Souza Farias SA, da Costa KS, Martins JB (April 2021). "Analysis of Conformational, Structural, Magnetic, and Electronic Properties Related to Antioxidant Activity: Revisiting Flavan, Anthocyanidin, Flavanone, Flavonol, Isoflavone, Flavone, and Flavan-3-ol". ACS Omega. 6 (13): 8908–8918. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c06156. PMC 8028018. PMID 33842761.

- ^ McNaught AD, Wilkinson A (1997), IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology (2nd ed.), Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, doi:10.1351/goldbook.F02424, ISBN 978-0-9678550-9-7

- ^ Vitamins and Hormones, Volume 7. New York: Academic Press. 1949.

- ^ Clemetson AB (10 January 2018). Vitamin C: Volume I. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-351-08601-1.

- ^ Galeotti F, Barile E, Curir P, et al. (2008). "Flavonoids from carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) and their antifungal activity". Phytochemistry Letters. 1 (1): 44–48. Bibcode:2008PChL....1...44G. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2007.10.001.

- ^ Ververidis F, Trantas E, Douglas C, et al. (October 2007). "Biotechnology of flavonoids and other phenylpropanoid-derived natural products. Part I: Chemical diversity, impacts on plant biology and human health". Biotechnology Journal. 2 (10): 1214–1234. doi:10.1002/biot.200700084. PMID 17935117. S2CID 24986941.

- ^ Zhao DQ, Han CX, Ge JT, et al. (15 November 2012). "Isolation of a UDP-glucose: Flavonoid 5-O-glucosyltransferase gene and expression analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.)". Electronic Journal of Biotechnology. 15 (6). doi:10.2225/vol15-issue6-fulltext-7.

- ^ Spencer JP (May 2008). "Flavonoids: modulators of brain function?". The British Journal of Nutrition. 99 (E Suppl 1): ES60 – ES77. doi:10.1017/S0007114508965776. PMID 18503736.

- ^ a b "Sources of Flavonoids in the U.S. Diet Using USDA's Updated Database on the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods" (PDF). Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture. 2006.

- ^ Oomah BD, Mazza G (1996). "Flavonoids and Antioxidative Activities in Buckwheat". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 44 (7): 1746–1750. doi:10.1021/jf9508357.

- ^ Levaj B, et al. (2009). "Determination of flavonoids in pulp and peel of mandarin fruits (table 1)" (PDF). Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus. 74 (3): 223. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ De Camargo AC, Regitano-d'Arce MA, Gallo CR, et al. (2015). "Gamma-irradiation induced changes in microbiological status, phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of peanut skin". Journal of Functional Foods. 12: 129–143. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2014.10.034.

- ^ Chukwumah Y, Walker LT, Verghese M (November 2009). "Peanut skin color: a biomarker for total polyphenolic content and antioxidative capacities of peanut cultivars". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 10 (11): 4941–4952. doi:10.3390/ijms10114941. PMC 2808014. PMID 20087468.

- ^ a b c d Vogiatzoglou A, Mulligan AA, Lentjes MA, et al. (2015). "Flavonoid intake in European adults (18 to 64 years)". PLoS One. 10 (5) e0128132. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1028132V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128132. PMC 4444122. PMID 26010916.

- ^ a b Chun OK, Chung SJ, Song WO (May 2007). "Estimated dietary flavonoid intake and major food sources of U.S. adults". The Journal of Nutrition. 137 (5): 1244–1252. doi:10.1093/jn/137.5.1244. PMID 17449588.

- ^ "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels - Reference Guide: Daily Values for Nutrients". US Food and Drug Administration. 5 March 2024. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ a b EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (2010). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to various food(s)/food constituent(s) and protection of cells from premature aging, antioxidant activity, antioxidant content and antioxidant properties, and protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061". EFSA Journal. 8 (2): 1489. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1489.

- ^ Lotito SB, Frei B (December 2006). "Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon?". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 41 (12): 1727–1746. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.033. PMID 17157175.

- ^ Williams RJ, Spencer JP, Rice-Evans C (April 2004). "Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules?". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 36 (7): 838–849. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.001. PMID 15019969.

- ^ Hidalgo M, Oruna-Concha MJ, Kolida S, et al. (April 2012). "Metabolism of anthocyanins by human gut microflora and their influence on gut bacterial growth". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 60 (15): 3882–3890. doi:10.1021/jf3002153. PMID 22439618.

- ^ "FDA approved drug products". US Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 11 October 2003. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ "Health Claims Meeting Significant Scientific Agreement". US Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 4 August 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Hensley S (7 September 2010). "FDA To Lipton: Tea Can't Do That". NPR. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ "Cherry companies warned by FDA against making health claims". The Produce News. 1 November 2005. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ "Warning letters to US supplement manufacturers (search "flavonoid")". US Food and Drug Administration. 28 August 2025. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ Ravishankar D, Rajora AK, Greco F, et al. (December 2013). "Flavonoids as prospective compounds for anti-cancer therapy". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 45 (12): 2821–2831. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2013.10.004. PMID 24128857.

- ^ Manach C, Mazur A, Scalbert A (February 2005). "Polyphenols and prevention of cardiovascular diseases". Current Opinion in Lipidology. 16 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1097/00041433-200502000-00013. PMID 15650567. S2CID 794383.

- ^ Babu PV, Liu D, Gilbert ER (November 2013). "Recent advances in understanding the anti-diabetic actions of dietary flavonoids". The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 24 (11): 1777–1789. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.06.003. PMC 3821977. PMID 24029069.

- ^ Ferretti G, Bacchetti T, Masciangelo S, et al. (April 2012). "Celiac disease, inflammation and oxidative damage: a nutrigenetic approach". Nutrients. 4 (4): 243–257. doi:10.3390/nu4040243. PMC 3347005. PMID 22606367.

- ^ Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI (2012). "Flavonoids and cancer prevention: a review of the evidence". Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics. 31 (3): 206–238. doi:10.1080/21551197.2012.702534. PMID 22888839. S2CID 205960210.

- ^ Wang X, Ouyang YY, Liu J, et al. (January 2014). "Flavonoid intake and risk of CVD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". The British Journal of Nutrition. 111 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1017/S000711451300278X. PMID 23953879.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of a health claim related to cocoa flavanols and maintenance of normal endothelium-dependent vasodilation pursuant to Article 13(5) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006". EFSA Journal. 10 (7). 27 June 2012. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2809. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ "Cocoa flavanol health claim becomes EU law". Confectionary News. 4 September 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ Kavanaugh C (1 February 2023). RE: Petition for a Qualified Health Claim – for Cocoa Flavanols and Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease (Docket No. FDA-2019-Q-0806) (Report). FDA.

- ^ Aubrey A (12 February 2023). "Is chocolate good for your heart? Finally the FDA has an answer – kind of". NPR. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ Sinha RK (January 2004). Modern Plant Physiology. CRC Press. p. 457. ISBN 9780849317149.

- ^ Trantas E, Panopoulos N, Ververidis F (November 2009). "Metabolic engineering of the complete pathway leading to heterologous biosynthesis of various flavonoids and stilbenoids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Metabolic Engineering. 11 (6): 355–366. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2009.07.004. PMID 19631278.

- ^ Ververidis F, Trantas E, Douglas C, et al. (October 2007). "Biotechnology of flavonoids and other phenylpropanoid-derived natural products. Part II: Reconstruction of multienzyme pathways in plants and microbes". Biotechnology Journal. 2 (10): 1235–1249. doi:10.1002/biot.200700184. PMID 17935118. S2CID 5805643.

- ^ Yisa J (2009). "Phytochemical Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of Scoparia dulcis and Nymphaea lotus". Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 3 (4): 3975–3979. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- ^ Bello IA, Ndukwe GI, Audu OT, et al. (October 2011). "A bioactive flavonoid from Pavetta crassipes K. Schum". Organic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 1 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/2191-2858-1-14. PMC 3305906. PMID 22373191.

- ^ Delcour JA (1985). "A New Colourimetric Assay for Flavanoids in Pilsner Beers". Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 91: 37–40. doi:10.1002/j.2050-0416.1985.tb04303.x.

- ^ Lamaison JL, Carnet A (1991). "Teneurs en principaux flavonoïdes des fleurs de Cratageus monogyna Jacq. et de Cratageus laevigata (Poiret D.C.) en fonction de la végétation" [Principal flavonoid content of flowers of Cratageus monogyna Jacq. and Cratageus laevigata (Poiret D.C.) dependent on vegetation]. Plantes Medicinales: Phytotherapie (in French). 25: 12–16.

- ^ Khokhlova K, Zdoryk O, Vyshnevska L (January 2020). "Chromatographic characterization on flavonoids and triterpenes of leaves and flowers of 15 crataegus L. species". Natural Product Research. 34 (2): 317–322. doi:10.1080/14786419.2018.1528589. ISSN 1478-6427. PMID 30417671.

- ^ Passicos E, Santarelli X, Coulon D (July 2004). "Regioselective acylation of flavonoids catalyzed by immobilized Candida antarctica lipase under reduced pressure". Biotechnology Letters. 26 (13): 1073–1076. doi:10.1023/B:BILE.0000032967.23282.15. PMID 15218382. S2CID 26716150.

Further reading

[edit]- Andersen ØM, Markham KR (2006). Flavonoids: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8493-2021-7.

- Grotewold E (2006). The science of flavonoids. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-74550-3.

- Harborne JB (1967). Comparative Biochemistry of the Flavonoids.

- Mabry TJ, Markham KR, Thomas MB (1971). "The systematic identification of flavonoids". Journal of Molecular Structure. 10 (2): 320. doi:10.1016/0022-2860(71)87109-0.