Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fortune-telling

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

Fortune-telling is the spiritual practice of predicting information about a person's life.[1] The scope of fortune telling is in principle identical with the practice of divination. The difference is that divination is the term used for predictions considered part of a religious ritual, invoking deities or spirits, while the term fortune telling implies a less serious or formal setting, even one of popular culture, where belief in occult workings behind the prediction is less prominent than the concept of suggestion, spiritual or practical advisory or affirmation.

Historically, Pliny the Elder describes use of the crystal ball in the 1st century CE by soothsayers ("crystallum orbis", later written in Medieval Latin by scribes as orbuculum).[2] Contemporary Western images of fortune telling grow out of folkloristic reception of Renaissance magic, specifically associated with Romani people.[1] During the 19th and 20th century, methods of divination from non-Western cultures, such as the I Ching, were also adopted as methods of fortune telling in Western popular culture.

An example of divination or fortune telling as purely an item of pop culture, with little or no vestiges of belief in the occult, would be the Magic 8 Ball sold as a toy by Mattel, or Paul the Octopus, an octopus at the Sea Life Aquarium at Oberhausen used to predict the outcome of matches played by the Germany national football team.[3] There is opposition to fortune telling in Christianity, Islam, Baháʼísm and Judaism based on scriptural prohibitions against divination. Terms for one who claims to see into the future include fortune teller, crystal-gazer, spaewife, seer, soothsayer, sibyl, clairvoyant, and prophet; related terms which might include this among other abilities are oracle, augur, and visionary. Fortune telling is dismissed by skeptics as being based on pseudoscience, magical thinking and superstition.

Methods

[edit]

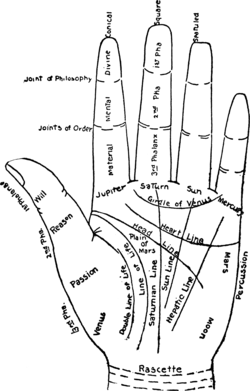

Common methods used for fortune telling in Europe and the Americas include astromancy, horary astrology, pendulum reading, spirit board reading, tasseography (reading tea leaves in a cup), cartomancy (fortune telling with cards), tarot card reading, crystallomancy (reading of a crystal sphere), and chiromancy (palmistry, reading of the palms). The last three have traditional associations in the popular mind with the Roma and Sinti people.

Another form of fortune telling, sometimes called "reading" or "spiritual consultation", does not rely on specific devices or methods, but rather the practitioner gives the client advice and predictions which are said to have come from spirits or in visions:

- Aeromancy: by interpreting atmospheric conditions.

- Alectromancy: by observation of a rooster pecking at grain.

- Aleuromancy: by flour.

- Astrology: by the movements of celestial bodies.

- Astromancy: by the stars.

- Augury: by the flight of birds.

- Auramancy by someone's aura or feelings

- Bazi or four pillars: by hour, day, month, and year of birth.

- Bibliomancy: by books; frequently, but not always, religious texts.

- Cartomancy: by playing cards, tarot cards, or oracle cards.

- Ceromancy: by patterns in melting or dripping wax.

- Chiromancy: by the shape of the hands and lines in the palms.

- Chronomancy: by determination of lucky and unlucky days.

- Clairvoyance: by spiritual vision or inner sight.

- Cleromancy: by casting of lots, or casting bones or stones.

- Cold reading: by using visual and aural clues.

- Crystallomancy: by crystal ball also called scrying.

- Extispicy: by the entrails of animals.

- Face reading: by means of variations in face and head shape.

- Feng shui: by earthen harmony.

- Gastromancy: by stomach-based ventriloquism (historically).

- Geomancy: by markings in the ground, sand, earth, or soil.

- Hafez fal: by poems of Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī

- Haruspicy: by the livers of sacrificed animals.

- Horary astrology: the astrology of the time the question was asked.

- Hydromancy: by water.

- I Ching divination: by yarrow stalks or coins and the I Ching.

- Kau cim by means of numbered bamboo sticks shaken from a tube.

- Lithomancy: by stones or gems.

- Molybdomancy: by molten metal after dumped in cold water.

- Naeviology: by moles, scars, or other bodily marks.

- Necromancy: by the dead, or by spirits or souls of the dead.

- Nephomancy: by shapes of clouds.

- Numerology: by numbers.

- Oneiromancy: by dreams.

- Onomancy: by names.

- Onychomancy: by a form of palmistry looking at the fingernails.

- Palmistry: by lines and mounds on the hand.

- Parrot astrology: by parakeets picking up fortune cards

- Paper fortune teller: origami used in fortune-telling games.

- Pendulum reading: by the movements of a suspended object.

- Pyromancy: by gazing into fire.

- Rhabdomancy: divination by rods.

- Runecasting or Runic divination: by runes.

- Scrying: by looking at or into reflective objects.

- Spirit board: by planchette or talking board.

- Taromancy: by a form of cartomancy using tarot cards.

- Tasseography or tasseomancy: by tea leaves or coffee grounds.

Sociology

[edit]

Western fortune tellers typically attempt predictions on matters such as future romantic, financial, and childbearing prospects. Many fortune tellers will also give "character readings". These may use numerology, graphology, palmistry (if the subject is present), and astrology. [citation needed]

In contemporary Western culture, it appears that women consult fortune tellers more than men.[4] Some women have maintained long relationships with their personal readers. Telephone consultations with psychics grew in popularity through the 1990s, and by the 2010s additional contact methods such as email and videoconferencing also became available, but none of these have completely replaced traditional in-person methods of consultation.[5]

Children's fortune-telling games

[edit]Children's fortune-telling games are informal activities that mimic traditional divination practices, often serving as a form of play rather than serious attempts to predict the future. These games are prevalent in various cultures and have been documented in folklore studies.[example needed] They are often played with simple objects like folded paper or pencils like MASH and Cootie Catchers.[citation needed]

As a business

[edit]

Discussing the role of fortune telling in society, Ronald H. Isaacs, an American rabbi and author, opined, "Since time immemorial humans have longed to learn that which the future holds for them. Thus, in ancient civilization, and even today with fortune telling as a true profession, humankind continues to be curious about its future, both out of sheer curiosity as well as out of desire to better prepare for it."[6] Although soothsayers were viewed as prized advisers in ancient and premodern civilizations such as the Assyrians, they lost respect and reverence during the Age of Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries.[7]

With the rise of commercialism, "the sale of occult practices [adapted to survive] in the larger society," according to sociologists Danny L. and Lin Jorgensen.[8] Ken Feingold, writer of "Interactive Art as Divination as a Vending Machine," stated that with the invention of money, fortune telling became "a private service, a commodity within the marketplace".[9]

As J. Peder Zane wrote in The New York Times in 1994, referring to the Psychic Friends Network, "Whether it's 3 P.M. or 3 A.M., there's Dionne Warwick and her psychic friends selling advice on love, money and success. In a nation where the power of crystals and the likelihood that angels hover nearby prompt more contemplation than ridicule, it may not be surprising that one million people a year call Ms. Warwick's friends."[7]

Clientele

[edit]In 1994, the psychic counsellor Rosanna Rogers of Cleveland, Ohio, explained to J. Peder Zane that a wide variety of people consulted her: "Couch potatoes aren't the only people seeking the counsel of psychics and astrologers. Clairvoyants have a booming business advising Philadelphia bankers, Hollywood lawyers and CEO's of Fortune 500 companies... If people knew how many people, especially the very rich and powerful ones, went to psychics, their jaws would drop through the floor."[7] Rogers "claims to have 4,000 names in her rolodex."[7]

Janet Lee, also known as the Greenwich psychic, claims that her clientele often included Wall Street brokers who were looking for any advantage they could get. Her usual fee was around $150 for a session but some clients would pay between $2,000 and $9,000 per month to have her available 24 hours a day to consult.[10]

Typical clients

[edit]In 1982, Danny Jorgensen, a professor of Religious Studies at the University of South Florida offered a spiritual explanation for the popularity of fortune telling. He said that people visit psychics or fortune tellers to gain self-understanding,[11] and knowledge which will lead to personal power or success in some aspect of life.[12]

In 1995, Ken Feingold offered a different explanation for why people seek out fortune tellers:[9]

We desire to know other people's actions and to resolve our own conflicts regarding decisions to be made and our participation in social groups and economies. ... Divination seems to have emerged from our knowing the inevitability of death. The idea is clear—we know that our time is limited and that we want things in our lives to happen in accord with our wishes. Realizing that our wishes have little power, we have sought technologies for gaining knowledge of the future... gain power over our own [lives].

Ultimately, the reasons a person consults a diviner or fortune teller depend on cultural and personal expectations.

Services

[edit]Traditional fortune tellers vary in methodology, generally using techniques long established in their cultures and thus meeting the cultural expectations of their clientele.

In the United States and Canada, among clients of European ancestry, palmistry is popular[13] and, as with astrology and tarot card reading, advice is generally given about specific problems besetting the client.

Non-religious spiritual guidance may also be offered. An American clairvoyant by the name of Catherine Adams has written, "My philosophy is to teach and practice spiritual freedom, which means you have your own spiritual guidance, which I can help you get in touch with."[14]

In the African American community, where many people practice a form of folk magic called hoodoo or rootworking, a fortune-telling session or "reading" for a client may be followed by practical guidance in spell-casting and Christian prayer, through a process called "magical coaching".[15]

In addition to sharing and explaining their visions, fortune tellers can also act like counselors by discussing and offering advice about their clients' problems.[13] They want their clients to exercise their own willpower.[16]

Full-time careers

[edit]

Some fortune tellers support themselves entirely on their divination business; others hold down one or more jobs, and their second jobs may or may not relate to the occupation of divining. In 1982, Danny L., and Lin Jorgensen found that "while there is considerable variation among [these secondary] occupations, [part-time fortune tellers] are over-represented in human service fields: counseling, social work, teaching, health care."[17] The same authors, making a limited survey of North American diviners, found that the majority of fortune tellers are married with children, and a few claim graduate degrees.[18] "They attend movies, watch television, work at regular jobs, shop at K-Mart, sometimes eat at McDonald's, and go to the hospital when they are seriously ill."[19]

Legality

[edit]

In 1982, the sociologists Danny L., and Lin Jorgensen found that, "when it is reasonable, [fortune tellers] comply with local laws and purchase a business license."[17] However, in the United States, a variety of local and state laws restrict fortune telling, require the licensing or bonding of fortune tellers, or make necessary the use of terminology that avoids the term "fortune teller" in favor of terms such as "spiritual advisor" or "psychic consultant." There are also laws that outright forbid the practice in certain districts.

For instance, fortune telling is a class B misdemeanor in the state of New York. Under New York State law, S 165.35:

A person is guilty of fortune telling when, for a fee or compensation which he directly or indirectly solicits or receives, he claims or pretends to tell fortunes, or holds himself out as being able, by claimed or pretended use of occult powers, to answer questions or give advice on personal matters or to exercise, influence or affect evil spirits or curses; except that this section does not apply to a person who engages in the aforedescribed conduct as part of a show or exhibition solely for the purpose of entertainment or amusement.[20]

Lawmakers who wrote this statute acknowledged that fortune tellers do not restrict themselves to "a show or exhibition solely for the purpose of entertainment or amusement" and that people will continue to seek out fortune tellers even though fortune tellers operate in violation of the law. In the states of Minnesota, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, all forms of fortune-telling are illegal.[21]

In Australia, fortune-telling is illegal in South Australia and the Northern Territory.[22]

Saudi Arabia also bans the practice outright, considering fortune telling to be sorcery and thus contrary to Islamic teaching and jurisprudence. It has been punishable by death.[23]

In the United Kingdom, there was The Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951 which prohibited a person from claiming to be a fortune teller in order to make money for another reason than the purpose of entertainment. This act was repealed in 2008, and replaced by The Consumer Protection Act.[citation needed]

Critical analysis

[edit]

Fortune telling is easily dismissed by critics as magical thinking and superstition.[24][25][26]

Skeptic Bergen Evans suggested that fortune telling is the result of a "naïve selection of something that have happened from a mass of things that haven't, the clever interpretation of ambiguities, or a brazen announcement of the inevitable."[27] Other skeptics claim that fortune telling is nothing more than cold reading.[28]

A large amount of fraud has been proven in the practice of fortune telling.[29]

Fortune telling and how it works raises many critical questions. For example, fortune-telling occurs through various methods such as psychic readings and tarot cards. Similarly, these methods are largely based on random phenomena. For example, astrologers believe that the movement of stars in the sky can have implications on one's life.[30] In the case of tarot cards, people believe that images displayed on the cards have significant meanings on their lives. However, there is a lack of evidence to support why such things, such as the stars, would have any implications on our lives.

Additionally, fortune-telling readings and predictions made by horoscopes, for example, are often general enough to apply to anyone. In cold reading, for example, readers often begin by stating general descriptions and continuing to make specifics based on the reactions they receive from the person whose life they are predicting.[31] The tendency for people to deem general descriptions as being representative to themselves has been termed the Barnum effect and has been studied by psychologists for many years.[31]

Nonetheless, even with a lack of evidence supporting the various methods of fortune-telling and the many frauds that have occurred by psychic readers, amongst others, fortune-telling continues to become popular around the world. There are many reasons for the appealing nature of fortune-telling such as that people often experience stress when there is uncertainty and thus seek to gain deeper insight into their lives.

See also

[edit]- Chinese fortune telling

- Chinese spiritual world concepts

- Divination

- Divination in African traditional religion

- Flim-Flam! Psychics, ESP, Unicorns and other Delusions

- Fortune teller machine

- Kumari

- Ka-Bala board game

- Houdini's debunking spiritualists

- I Ching divination

- Bob Nygaard (psychic investigator)

- Peter Popoff investigated by James Randi

- Prophecy

- Psychic Blues: Confessions of a Conflicted Medium

- Rose Mackenberg (American investigator of psychic mediums)

- Tengenjutsu (fortune telling)

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Melton, J. Gordon. (2008). The Encyclopedia of Religious Phenomena. Visible Ink Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 1-57859-209-7

- ^ Pliny the Elder (1831). Caii Plinii Secundi Historiæ naturalis libri xxxvii, cum selectis comm. J. Harduini ac recentiorum interpretum novisque adnotationibus. p. 579. Retrieved 7 November 2015. (in Latin)

- ^ Associated Press6 July 2010

- ^ Blécourt, Willem de; Usborne, Cornelle. (1999). Women's Medicine, Women's Culture: Abortion and Fortune telling in Early Twentieth-Century Germany and the Netherlands. Medical History 43: 376–392.

- ^ Burton, Valentina. The Fortune Teller's Guide to Success: Creating a Wonderful Career as a Psychic. 2011; Lucky Mojo Curio Co. (revised) Fourth Edition 2018.

- ^ Isaacs, Ronald H. Divination, Magic, and Healing the Book of Jewish Folklore. Northvale N.J.: Jason Aronson, 1998. pg 55

- ^ a b c d (Zane 1994)

- ^ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 376)

- ^ a b (Feingold 1995, p. 399)

- ^ Kadet, Anne (8 March 2014). "In Greenwich, Where Money Is No Object". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 381)

- ^ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 375)

- ^ a b "Clairvoyant or counsellor? Meet the woman who walks a fine line." The Northern Echo. 27 October 2000.

- ^ Adams, Catherine. "What is Clairvoyance and What Can I Expect in a Session With Catherine?" Archived 18 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Magical Coaching and Spiritual Advice are among the ancillary services offered by some diviners and root doctors. These consultation services are usually engaged on an hourly basis." – excerpt from an article on "magical coaching" at the Association of Independent Readers and Rootworkers web site

- ^ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 384)

- ^ a b (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 377)

- ^ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 337)

- ^ (Jorgensen & Jorgensen 1982, p. 387)

- ^ Leginfo.state.ny.us

- ^ "The First Amendment is for Fortune-tellers, Too | Free Inquiry". 2 June 2003.

- ^ Piper, Alana (3 February 2020). Beaumont, Lucy (ed.). "Did they see it coming? How fortune-telling took hold in Australia - with women as clients and criminals". doi:10.64628/AA.qxau7ycp7.

- ^ Fortune Teller Faces Execution in Saudi Arabia Archived 4 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine pattayadailynews.com Archived 23 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine 1 April 2010 retrieved 17 July 2010

- ^ Pronko, Nicholas Henry. (1969). Panorama of Psychology. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. p. 18

- ^ Miller, Gale. (1978). Odd Jobs: The World of Deviant Work. Prentice-Hall. pp. 66–68

- ^ Regal, Brian. (2009). Pseudoscience: A Critical Encyclopedia. Greenwood. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-313-35507-3

- ^ Evans, Bergen. (1955). The Spoor of Spooks: And Other Nonsense. Purnell. p. 16

- ^ Cogan, Robert. (1998). Critical Thinking: Step by Step. University Press of America. p. 212. ISBN 0-7618-1067-6

- ^ Steiner, Robert A. (1996). Fortunetelling. In Gordon Stein. The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 281–290. ISBN 1-57392-021-5

- ^ Thagard, Paul R. (1978). Why astrology is a pseudoscience in The Philosophy of Science Association, 1978 Volume 1, pp. 223–234.

- ^ a b Dutton, D.L. (1988). The Cold Reading Technique in Experientia, Volume 44, pp. 326–332

References

[edit]- Feingold, Ken (1995), "OU: Interactivity as Divination as Vending Machine", Leonardo, Third Annual New York Digital Salon, 28 (5): 399–402, doi:10.2307/1576224, JSTOR 1576224, S2CID 61727726

- Hughes, M., Behanna, R; Signorella, M. (2001). Perceived Accuracy of Fortune Telling and Belief in the Paranormal. Journal of Social Psychology 141: 159–160.

- Jorgensen, Danny L.; Jorgensen, Lin (1982), "Social Meanings of the Occult", The Sociological Quarterly, 23 (3): 373–389, doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1982.tb01019.x.

- Zane, J. Peder (11 September 1994), "Soothsayers as Business Advisers; You Are Going to Go on a Long Trip...", The New York Times.

External links

[edit] Media related to Fortune-telling at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fortune-telling at Wikimedia Commons

Fortune-telling

View on GrokipediaFortune-telling is the practice of claiming to predict future events or discern hidden personal information through methods deemed irrational or supernatural, such as interpreting celestial positions, hand lines, or card layouts. These techniques encompass astrology, palmistry (chiromancy), tarot card reading (cartomancy), tea leaf reading (tasseography), and scrying with crystal balls or mirrors, among others.[1] Originating in ancient civilizations like Babylonia, Egypt, and China around 4000 BC, fortune-telling has persisted across cultures as a means to address uncertainty, often integrated into religious or shamanistic rituals.[2] Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that fortune-telling lacks predictive validity, with outcomes indistinguishable from chance or vague generalizations tailored to elicit agreement.[3] Perceived accuracy stems from psychological mechanisms, including confirmation bias—where individuals recall hits and ignore misses—and the Forer (or Barnum) effect, whereby broad statements are interpreted as personally insightful.[4] Greater understanding of scientific methods correlates with reduced belief in such practices, highlighting their incompatibility with evidence-based reasoning.[5] While proponents assert intuitive or spiritual efficacy, no controlled experiments have substantiated supernatural foresight, and many practitioners employ cold reading—observing cues and making educated guesses—to simulate prescience.[3] Historically, fortune-telling has faced legal restrictions as fraud or superstition, with bans in various jurisdictions underscoring its exploitative potential, particularly among the vulnerable seeking guidance amid life's ambiguities.[6] Despite debunking, its cultural endurance reflects human tendencies toward pattern-seeking and aversion to randomness, often resulting in addictive dependencies or misguided decisions.[7]

Historical Development

Ancient Origins and Early Practices

Divination, the precursor to formalized fortune-telling, emerged in Mesopotamia around the fourth millennium BCE as a method to discern divine intentions through observable signs. Archaeological evidence from Sumerian and Akkadian sites reveals early practices of extispicy, involving the examination of animal entrails, particularly sheep livers, to predict outcomes such as military campaigns or royal decisions. Clay liver models, known as barûtu tablets, dating to approximately 1900 BCE from Mari and other sites, document standardized interpretations of liver markings, indicating a systematized profession of diviners (bārû) who advised kings based on these readings.[8][9] In ancient Egypt, divination practices paralleled Mesopotamian ones but emphasized dream incubation and oracular consultations from the Old Kingdom onward (c. 2686–2181 BCE). Priests interpreted dreams in temple settings, as recorded in texts like the Chester Beatty Papyrus, where pharaohs sought guidance on state matters through divine responses. Astrology also featured prominently, with decans—star groups tracked for horoscopic predictions—evident in pyramid texts and astronomical ceilings from tombs like that of Senenmut (c. 1479–1458 BCE), reflecting beliefs in celestial influences on terrestrial events.[10] Chinese oracle bone divination, or pyromancy, dates to the late Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), where royal diviners inscribed questions on ox scapulae or turtle plastrons, heated them to produce cracks, and interpreted patterns as ancestral or divine replies. Over 150,000 fragments excavated from Anyang sites contain the earliest known Chinese script, detailing queries on harvests, battles, and health, underscoring divination's role in governance and ritual.[11][12] In ancient Greece, the Oracle of Delphi, operational by the eighth century BCE and possibly rooted in Bronze Age Mycenaean practices (c. 1600–1100 BCE), involved the Pythia inhaling vapors or entering trance states to deliver ambiguous prophecies interpreted by priests. Historical records, including Herodotus's accounts of consultations influencing events like the Persian Wars (499–449 BCE), attest to its political impact, though geological analyses suggest natural fissures emitting ethylene gas may have induced altered states rather than supernatural agency.[13]Evolution in Major Civilizations

In ancient Mesopotamia, divination practices emerged prominently around 2000 BCE, with hepatoscopy—the examination of sheep livers for omens—serving as a primary method to interpret divine will regarding events like sieges or royal decisions.[14] Clay models of livers, inscribed with interpretations, were used to standardize readings from abnormalities in the organ's shape and markings, reflecting a belief that gods inscribed messages on the liver as the seat of the soul.[15] These techniques influenced later Near Eastern and Mediterranean practices, emphasizing empirical observation of sacrificial entrails over random chance.[16] Ancient Egyptian divination centered on dreams as direct communications from gods, with records from the Middle Kingdom (c. 2050–1710 BCE) onward documenting interpretations by priests to predict outcomes like health or Nile floods.[17] Techniques included trance induction, scrying in water or oil, and invoking deities like Thoth for prophetic insight, often tied to temple rituals rather than individual fortune-tellers.[18] Oracles, such as those consulting sacred animals or statues, provided communal guidance, evolving from pharaonic consultations to broader societal use by the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE).[19] In China, oracle bone divination arose during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), involving heating inscribed ox scapulae or turtle plastrons to produce cracks interpreted as responses from ancestors or deities on matters like harvests or warfare.[20] This pyromantic method, yielding over 150,000 discovered bones by the 20th century, transitioned into the I Ching (Book of Changes) by the Western Zhou period (c. 1046–771 BCE), where yarrow stalks or coins systematized hexagram-based prognostication without physical remains.[21] These practices persisted as state rituals, prioritizing patterned causality over mysticism. Indian divination integrated with Vedic traditions by c. 1500 BCE, featuring Jyotisha (astral observation) for calendrical and horoscopic predictions, alongside early palmistry (hast rekha) linked to hand lines as indicators of karma-influenced fate.[22] Nadi astrology, using ancient palm-leaf manuscripts attributed to sages, emerged later but drew from proto-Vedic omen reading, focusing on nakshatras (lunar mansions) for personalized forecasts rather than generalized oracles.[23] Greek practices evolved from Near Eastern imports, with the Delphic Oracle—operational by the 8th century BCE—employing the Pythia priestess in trance states to deliver Apollo's ambiguous prophecies on state affairs, influencing decisions like colonization until Hellenistic decline.[24] Astrology, adapted from Babylonian models by the 5th century BCE via figures like Hipparchus, shifted emphasis to natal charts for individual destinies.[25] Romans incorporated Etruscan haruspicy (entrail reading) and Greek oracles, formalizing augury under the Republic (509–27 BCE) for military and political validation, blending empirical signs with imperial policy.[26]Modern Commercialization and Persistence

The psychic services industry in the United States, encompassing astrology, palm reading, tarot, and fortune-telling, generated an estimated $2.3 billion in revenue in 2024, employing approximately 105,000 individuals.[27] This sector has exhibited steady growth, with revenue expanding at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.5% leading up to 2025.[27] Commercialization accelerated in the late 20th century through psychic hotlines, such as the Psychic Friends Network, which peaked at over $100 million annually in the early 1990s before facing competition and filing for bankruptcy in 1998.[28][29] Similarly, the Psychic Readers Network, featuring "Miss Cleo," amassed roughly $1 billion in telephone charges over several years in the late 1990s and early 2000s through high per-minute fees.[30] In the digital era, fortune-telling has shifted to online platforms and mobile applications, further entrenching its commercial viability. The global astrology app market, a key segment, was valued at approximately $4.02 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $29.82 billion by 2033, growing at a CAGR of 24.93%.[31] This expansion reflects integration with technology, including AI-driven personalization and subscription models for horoscopes, readings, and virtual consultations.[32] Broader astrology services worldwide are estimated at $12.8 billion as of 2021, forecasted to grow to $22.8 billion by 2031 at a CAGR of 5.7%.[33] In regions like Hong Kong and mainland China, online divination has surged among younger demographics, with fortune-telling bars and apps catering to demands for quick, accessible guidance amid economic uncertainties.[34][35] Europe reports a fortune-telling industry worth €3 billion annually as of 2025, driven by rising demand.[36] Persistence of these practices stems from sustained public interest, with 30% of U.S. adults reporting consultation of astrology, tarot cards, or fortune tellers at least once a year, though most characterize it as entertainment rather than serious belief.[37] Usage is particularly prevalent among millennials and Generation Z, who engage via social media, apps, and pop culture integrations, blending traditional methods with modern spirituality.[38] Despite regulatory scrutiny and instances of fraud—such as bans lifted in U.S. cities amid industry growth—the market endures due to low barriers to entry, repeat consumer demand, and cultural embedding in uncertain times.[39][40] This commercialization underscores a divergence from ancient ritualistic origins, prioritizing profit through scalable, technology-enabled delivery over empirical validation.Methods and Techniques

Celestial and Astrological Divination

Celestial divination refers to the interpretation of astronomical phenomena, such as the positions and movements of stars, planets, the Sun, Moon, and other sky events like eclipses or comets, as omens or predictors of terrestrial events. Originating in ancient Mesopotamia during the second millennium BCE, Babylonian priests systematically recorded celestial observations in omen texts to guide royal decisions, viewing anomalies like planetary retrogrades or lunar eclipses as divine signals of impending fortune or misfortune.[41] This practice distinguished itself from pure astronomy by attributing causal influence from the heavens to human affairs, a premise lacking empirical support in modern scientific scrutiny.[42] Astrological divination formalized celestial methods into predictive systems, most notably through horoscopic astrology, which personalizes forecasts based on an individual's birth moment. The earliest known horoscopes date to Babylonian cuneiform tablets from around 500 BCE, calculating planetary positions to forecast outcomes for individuals rather than states.[43] By the Hellenistic period, following Alexander the Great's conquests around 330 BCE, Babylonian techniques merged with Greek geometry, yielding the 12-sign tropical zodiac aligned to seasons rather than constellations, despite the precession of equinoxes—discovered by Hipparchus circa 130 BCE—shifting stellar alignments by about one sign over two millennia.[8] Core techniques include natal chart construction, a diagrammatic representation of celestial bodies' ecliptic longitudes at birth, divided into zodiac signs, houses (12 spatial sectors symbolizing life areas like career or relationships), and aspects (angular relationships between planets purportedly indicating tensions or harmonies). Astrologers interpret these to delineate traits—e.g., Sun in Aries suggesting assertiveness—or events, such as Saturn transits predicting challenges.[44] Additional methods encompass electional astrology for optimal timing of actions (e.g., selecting wedding dates via favorable lunar phases) and mundane astrology for collective events like wars via national charts. These rely on ephemerides for positions, but controlled studies, including double-blind tests matching charts to personalities, consistently find matches no better than random guessing, undermining claims of efficacy.[42] In practice, Western astrology employs software or tables for chart calculation using birth date, time, and location, with interpretations varying by school—e.g., Vedic sidereal systems adjust for precession, differing from tropical by roughly 24 degrees. Historical texts like Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos (2nd century CE) codified rules linking planets to humors (e.g., Mars to blood and aggression), influencing medieval and Renaissance Europe, where courts consulted astrologers despite Church prohibitions. Modern persistence includes daily horoscopes in media, derived from simplified Sun-sign positions, which overlook full charts and exhibit Barnum effects—vague statements applicable to most. Empirical reviews confirm no causal mechanism exists for celestial influence on earthly events, as gravitational or electromagnetic effects from distant bodies are negligible compared to local factors like Earth's magnetic field.[42][44]Card-Based and Symbolic Interpretation

Card-based divination, known as cartomancy, employs decks of cards to derive symbolic meanings for purported insights into personal circumstances or future events. Standard playing cards, introduced to Europe in the 14th century from Asian origins, were adapted for fortune-telling by the 18th century, with records of such use appearing in French literature as early as 1480 and gaining popularity among itinerant practitioners.[45] Interpretations assign significances to suits—such as hearts for emotions, diamonds for material matters—and numerical values, often arranged in spreads like the three-card past-present-future layout to contextualize outcomes relative to the querent's query.[46] Tarot cards, a specialized 78-card deck comprising 22 Major Arcana (archetypal figures like The Fool or The Tower) and 56 Minor Arcana (divided into four suits mirroring playing cards), originated in northern Italy during the 1440s as a trick-taking game rather than a divinatory tool.[47] Divinatory applications emerged in the late 18th century through occultists such as Jean-Baptiste Alliette (Etteilla), who published systematic interpretive methods in 1783, linking cards to esoteric traditions like Kabbalah and astrology despite lacking historical precedent for such uses in medieval Europe.[48] Readings typically involve shuffling while focusing on a question, then laying cards in patterns such as the 10-card Celtic Cross, where upright or reversed orientations modify meanings—e.g., The Lovers upright signifying harmony, reversed indicating discord—drawn from memorized symbolic associations rather than empirical prediction.[49] Symbolic interpretation extends beyond cards to systems of fixed icons or generated patterns, where meanings derive from cultural lore rather than randomization alone. The I Ching, an ancient Chinese text dating to the Western Zhou period (c. 1000–750 BCE), uses 64 hexagrams—combinations of six broken (yin) or solid (yang) lines—generated via yarrow stalks or three-coin tosses to yield probabilistic outcomes, with each hexagram offering interpretive judgments on change, such as Hexagram 1 (Qian) symbolizing creative force.[50] Traditional consultation emphasizes consulting the text's appended commentaries for nuanced readings, focusing on relational dynamics over literal prophecy.[51] Rune divination involves casting or drawing from sets of ancient Germanic symbols, primarily the 24-rune Elder Futhark alphabet attested from the 2nd to 8th centuries CE in inscriptions for writing and occasional magical purposes, though systematic divinatory practices lack archaeological or textual evidence prior to 20th-century reconstructions.[52] Modern methods, popularized by authors like Ralph Blum in the 1980s, assign each rune (e.g., Fehu for wealth or Ansuz for communication) interpretive values when drawn from a pouch, often in three-rune casts representing situation, action, and outcome, relying on subjective associations to mythic narratives.[53] These approaches prioritize pattern recognition in symbols over verifiable forecasting, with interpretations varying by practitioner despite standardized meanings in contemporary guides.Physical and Observational Methods

Palmistry, known technically as chiromancy, entails the divination of personality traits and future events through scrutiny of the hand's lines, shapes, and mounts. Medieval European texts, including Anglo-Norman manuscripts from the 12th century, document early systematic approaches to hand interpretation during the Plantagenet era and Reconquista periods.[54] By the 17th century in England, practitioners like Richard Saunders formalized chiromancy with over 700 aphorisms linking palm features to outcomes, aspiring to scientific legitimacy amid broader occult interests.[55] Interpretive techniques emphasize major palm lines—the heart line for emotions, head line for intellect, and life line for vitality—along with finger lengths and dermal patterns, purportedly revealing inherited potentials on the non-dominant hand and acquired influences on the dominant one. Mounts under fingers, such as the mount of Venus for passion, are assessed for prominence to infer strengths or weaknesses. These methods persist in contemporary practice despite lacking empirical validation. Physiognomy, the assessment of character and fate via facial and bodily morphology, traces to Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets predating Greek adoption.[56] Ancient Greek thinkers, including Aristotle, integrated it with humoral theory, positing that physical symmetries reflect temperament dictated by bodily fluids like blood or phlegm.[57] Features such as forehead breadth for intellect or jaw structure for aggression were mapped to virtues or vices, influencing judgments in philosophy, medicine, and divination until disfavor in the 16th century due to associations with charlatans. Tasseography involves interpreting sediment patterns in tea leaves, coffee grounds, or similar residues left in cups after consumption. Attributed to ancient Chinese Buddhist monks using ceremonial bell-shaped vessels, the practice spread to Europe in the 17th century following tea importation from Asia.[58] Diviners swirl remaining liquid to form symbols—lines for journeys, circles for financial gain—near cup rims for near-future events and bases for distant ones, peaking in Victorian occult fascination.[59] Other observational techniques include onychomancy, examining fingernail whiteness or shapes for health portents, and ancient haruspicy analogs in sediment reading, though these remain niche. Such methods uniformly depend on subjective pattern recognition, with no controlled studies demonstrating predictive power beyond chance.Miscellaneous Divinatory Practices

Tasseography, or the reading of tea leaves and coffee grounds, entails interpreting sediment patterns left in a cup after consumption. Practitioners claim these formations symbolize future events or personal traits, with symbols like hearts indicating love or birds suggesting travel. The method gained prominence in Europe during the 17th century following tea's introduction from China, peaking in popularity during the Victorian era amid interest in occult practices.[59] In Turkish tradition, coffee ground reading dates back at least 500 years, involving swirling the cup to form patterns interpreted for insights into relationships or finances.[60] Scrying involves gazing into reflective or translucent surfaces, such as crystal balls, black mirrors, or bodies of water, to induce visions or receive intuitive messages. This technique, documented across ancient cultures including Greece and medieval Europe, requires entering a trance-like state through focused staring, often in dim light, to perceive images purportedly revealing hidden knowledge.[61] Tools vary, with obsidian mirrors used by Mesoamerican shamans and quartz spheres favored in 19th-century Western esotericism for their clarity in evoking symbolic apparitions.[62] Bibliomancy employs random selection of passages from books, typically sacred texts like the Bible, to derive guidance or predictions. The querent poses a question, opens the book haphazardly, and interprets the revealed text as divine response, a method attested in Jewish and Christian traditions since antiquity.[63] Historical examples include its use in medieval Europe for resolving disputes, where the spine-balanced book would fall open to a page deemed providential.[64] Cleromancy, or casting lots, determines outcomes by throwing marked objects like dice, bones, or sticks, interpreting their positions as fateful indicators. This random sortition appears in biblical accounts, such as the apostles selecting Matthias in Acts 1:26 around 30 CE to replace Judas, relying on lots before the Holy Spirit's descent rendered such methods obsolete.[65] Ancient variants include Roman sortes using inscribed lots for oracular queries at temples, persisting in tribal practices like Zulu bone-throwing for ancestral counsel.[66]Psychological Underpinnings

Cognitive Biases Enabling Belief

Belief in fortune-telling persists despite empirical disconfirmation due to cognitive biases that systematically distort perception and judgment, favoring the interpretation of ambiguous or random information as meaningful and predictive. Psychological research identifies these as evolved mental shortcuts that once aided survival in uncertain environments but now enable susceptibility to pseudoscientific claims, including divination practices like astrology and palmistry. Studies link such beliefs to intuitive thinking styles that prioritize pattern detection over analytical scrutiny, with cognitive biases mediating up to 40% of the variance in paranormal endorsement among non-clinical populations.[67][68] A primary mechanism is the Barnum effect, also termed the Forer effect, wherein individuals rate vague, universally applicable statements as highly accurate descriptions of themselves. In Bertram Forer's 1949 classroom experiment involving 39 undergraduate students, participants received identical composite personality sketches drawn from horoscopes, yet rated their personal accuracy at an average of 4.26 on a 5-point scale, with many assuming the assessments were tailored diagnostics. This bias exploits the human preference for flattering, ego-syntonic content, explaining why fortune-tellers' generalized pronouncements—such as "you face inner conflicts but possess untapped potential"—elicit assent across diverse clients. Peer-reviewed replications confirm the effect's robustness, with belief strength correlating positively with narcissism and negatively with critical thinking skills.[69] Confirmation bias further entrenches adherence by prompting selective recall of verifying instances while discounting contradictions. Believers in divinatory systems disproportionately remember fulfilled predictions, such as a tarot card aligning with a subsequent event, and attribute misses to misinterpretation or external interference, a pattern observed in surveys of astrology adherents where 70% reported "hits" without tracking overall failure rates. This bias interacts with the availability heuristic, amplifying memorable coincidences over base-rate probabilities; for instance, rare alignments in celestial events are overinterpreted as causal omens despite statistical independence. Experimental data from pseudoscience endorsement models show these processes propagate via social transmission, as individuals share confirming anecdotes, polarizing group beliefs away from falsifying evidence. Illusory correlations, perceiving spurious links between diviner cues (e.g., palm lines) and outcomes, compound this, particularly under stress when need for closure heightens.[70][71]Techniques of Persuasion and Manipulation

Cold reading constitutes a primary method employed by fortune-tellers to create the illusion of supernatural insight into a client's personal circumstances, relying on probabilistic guesses, observation of behavioral cues, and verbal feedback loops rather than genuine precognition. Practitioners begin with broad, high-probability statements derived from demographic norms—such as references to family tensions or career uncertainties common to many adults—and refine them based on subtle client reactions like nods, hesitations, or verbal confirmations. This technique, detailed by psychologist Ray Hyman, exploits incomplete communication where clients fill in ambiguities, attributing accuracy to the reader while overlooking misses.[72][73] Central to cold reading are Barnum statements, vague yet personally resonant assertions that apply broadly to human experience, often phrased flatteringly to encourage acceptance; for instance, "You have a great need for other people to like and admire you, and yet you tend to be critical of yourself." Coined after showman P.T. Barnum's maxim of "something for everyone," this effect was empirically demonstrated in Bertram Forer's 1948 experiment, where students rated identical generic personality profiles—drawn from horoscopes—as 86% accurate on average when presented as individualized assessments. Fortune-tellers leverage this by embedding such statements in readings, ignoring disconfirmations and amplifying validations through selective reinforcement, thereby fostering perceived specificity.[72][74] Additional manipulative tactics include shotgunning, wherein the reader rapidly delivers multiple guesses to increase the likelihood of hits—e.g., naming common ailments or relationships—and discards failures while recapping confirmed details as proprietary revelations; and the rainbow ruse, presenting dual-edged propositions like "You are outgoing in groups but introspective alone" to ensure partial applicability regardless of truth. These methods, as analyzed in psychological literature, depend on client cooperation and the practitioner's skill in directing conversation toward confirmatory responses, often under low-light or atmospheric conditions that heighten suggestibility. Empirical scrutiny, including Hyman's observations of professional readers, reveals no paranormal basis, attributing success to these observable heuristics rather than divination.[75][72]Scientific Evaluation

Empirical Tests of Predictive Accuracy

Numerous controlled experiments have tested the predictive claims of fortune-telling methods, such as astrology and psychic readings, by comparing practitioners' forecasts or interpretations against chance expectations under double-blind conditions. These studies consistently find performance indistinguishable from random guessing, with no evidence of supernatural foresight. For instance, in predictive tasks involving future events or trait matching, success rates hover around baseline probabilities, failing statistical thresholds for significance.[76] A landmark double-blind study published in Nature in 1985 examined astrology's core claim that natal charts predict personality traits. Twenty-eight experienced astrologers attempted to match 23 sets of astrological charts to corresponding California Psychological Inventory (CPI) questionnaires from 116 participants, with charts and profiles shuffled to prevent cues. Astrologers selected the "best matching" chart for each profile, achieving a 33.9% success rate against an expected 33.3% by chance; a chi-square test yielded p ≈ 0.95, confirming no predictive validity. A follow-up matching task using astrologers' own personality ratings fared similarly, with p = 0.83. The experiment's rigor—pre-tested matching criteria, blinded raters, and statistical controls—has withstood critiques, though some astrologers argue it undervalued interpretive nuance; however, replication attempts, including a 2024 test involving over 100 astrologers predicting life outcomes from charts, similarly detected no above-chance accuracy.[76] Tests of other methods, like tarot card readings for future predictions or trait assessment, yield comparable null results, though fewer large-scale double-blind trials exist due to methodological challenges in standardizing symbolic interpretations. Small-scale experiments, such as those pitting tarot readers against random card assignments for personality or event forecasts, report hit rates near 50% for binary outcomes—matching chance—attributable to vagueness rather than prescience. Psychic prediction trials, including government-funded programs like the U.S. CIA's Stargate Project (1970s–1995), evaluated remote viewing and precognition for intelligence purposes but found no reliable accuracy beyond educated guesses, leading to termination after reviews deemed results inconsistent and non-replicable. Meta-analyses of parapsychological claims for anomalous prediction occasionally report marginal effects (e.g., 6–14% above chance in mediumship hit rates), but these draw from non-blinded, low-powered studies prone to publication bias and fail independent replication in stringent conditions; mainstream statistical scrutiny attributes them to error or fraud.[77]| Method | Key Test | Success Rate vs. Chance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astrology (Natal Matching) | Carlson (1985): 28 astrologers matched charts to CPI profiles | 33.9% vs. 33.3% (p=0.95) | Nature |

| Astrology (Outcome Prediction) | 2024 multi-phase trial: 100+ astrologers forecasted traits/events | No significant deviation | ZME Science[76] |

| Tarot/Psychic Readings | Analogous blind trials for binary predictions | ~50% for chance-level tasks | Skeptical reviews[78] |

| Precognition/Remote Viewing | Stargate Project evaluations (1978–1995) | Inconsistent; no operational utility | CIA declassified |

Explanations for Apparent Successes

Apparent successes in fortune-telling are often attributed to psychological mechanisms rather than supernatural insight. Practitioners employ techniques that exploit human cognitive tendencies, creating the illusion of prescience through observation, vagueness, and selective interpretation. Empirical studies demonstrate that these methods succeed not due to predictive power but because clients' responses and memories align predictions retroactively with reality.[75] Cold reading, a core technique, involves making high-probability statements about a client's background or traits, then refining them based on subtle verbal and non-verbal cues such as nods, hesitations, or facial expressions. For instance, a reader might state, "You have experienced a significant loss in your life," which applies broadly, and gauge reactions to pivot toward specifics like family or career. This process, described in psychological literature as calculated guessing dependent on client feedback, accounts for much of the perceived accuracy in one-on-one sessions. Skilled readers achieve this without prior knowledge, relying on statistical likelihoods—e.g., most people have faced relationship challenges—and rapid adaptation to signals.[75][80] The Barnum effect, also known as the Forer effect, explains why vague, universally applicable descriptions feel uniquely personal. In a 1948 experiment by psychologist Bertram Forer, students rated identical generic personality profiles (e.g., "You have a great need for other people to like and admire you") as highly accurate for themselves, averaging 4.26 out of 5. This effect underpins fortune-telling formats like horoscopes or tarot interpretations, where statements are flattering or neutral and broad enough to fit diverse experiences, leading believers to overlook mismatches. It has been replicated in contexts mimicking divination, confirming its role in sustaining faith in such practices.[81][82] Confirmation bias further amplifies these illusions by prompting individuals to recall "hits" while dismissing "misses." Clients remember accurate-seeming predictions but forget or rationalize failures, such as vague prophecies that partially align post-event. In divination contexts, this bias manifests as selective attention to confirming instances, like interpreting a tarot card's "change is coming" as fulfilled by any life shift, ignoring non-fulfillments. Studies on paranormal beliefs link this to reduced critical scrutiny, where prior expectations filter evidence.[83][84] Self-fulfilling prophecies contribute when predictions influence behavior, indirectly realizing them. A fortune-teller's forecast of career success might motivate the client to pursue opportunities more aggressively, leading to outcomes that validate the reading. Psychological research identifies this as expectation-driven action: beliefs alter conduct, creating feedback loops, as seen in educational settings where teacher expectations shape student performance. However, this applies only to actionable, positive predictions; dire warnings often fail without behavioral change, underscoring its limits in genuine foresight.[85][86] Collectively, these non-paranormal factors—without empirical support for extrasensory perception—explain reported accuracies, as rigorous tests show fortune-telling performs no better than chance when controlled for biases.[87]Cultural and Social Contexts

Integration with Religion and Folklore

In ancient Near Eastern religions, divination served as a primary mechanism for interpreting the will of the gods, with practices such as extispicy—examining animal entrails—documented in Mesopotamian texts from the third millennium BCE onward. These methods were integral to religious rituals, guiding kings in military decisions and private individuals in personal matters, as evidenced by cuneiform tablets recording omens and their interpretations.[8] Similarly, in ancient Greece, the Oracle of Delphi, dedicated to Apollo, functioned as a central religious institution where priestesses delivered prophecies in trance-like states, consulted by figures like Croesus of Lydia around 560 BCE for strategic advice, though interpretations often proved ambiguous and retrospectively fitted to outcomes.[88] Shamans and oracles held high status in these societies, advising leaders on matters of state and war. Such integrations positioned divination not as mere superstition but as a structured religious epistemology for navigating uncertainty, often extending to social rituals in group gatherings that facilitated storytelling and community bonding. Eastern traditions exhibit deeper symbiosis, as seen in the I Ching (Book of Changes), composed during the Western Zhou period (1046–771 BCE) and foundational to Taoist philosophy, where hexagram consultations via yarrow stalks or coins facilitate alignment with the Tao through symbolic interpretation rather than literal prediction. Taoist adepts like Liu I-ming (1737–1828) elaborated on its use for moral and existential guidance, emphasizing change's impermanence over deterministic foresight.[89] In contrast, African and Indigenous folk religions, such as Zulu osteomancy involving thrown bones, embedded divination within communal rituals to resolve disputes or foresee communal fates, persisting as oral traditions independent of written scriptures. Mesoamerican societies, including the Aztecs and Mayans, employed similar practices, using obsidian mirrors for scrying visions from deities like Tezcatlipoca and casting maize kernels to form patterns interpreted as omens.[90][91] These methods fostered community continuity by embedding predictions within shared cultural narratives.[66] Abrahamic faiths, however, largely rejected divination as antithetical to monotheistic revelation, with the Hebrew Bible prohibiting practices like necromancy and augury in Deuteronomy 18:10–12 (circa 7th century BCE) to centralize prophetic authority in Yahweh. Early Christian and Islamic doctrines echoed this, viewing such arts as idolatrous or shirk, though folk customs—such as Sicilian favomancy with beans or Scottish seer traditions like the 17th-century Brahan Seer—blended pre-Christian elements into Christian folklore, often rationalized as harmless superstition rather than overt religious rite. In Islamic folklore, dream interpretation and fal-e Hafez—randomly selecting verses from the poet Hafez for guidance—persisted as cultural practices.[92] Despite prohibitions, European monarchs in the Middle Ages consulted astrologers and diviners for counsel on governance and warfare.[93] This tension highlights divination's folkloric resilience, where empirical patterns in nature or symbols supplanted doctrinal bans, fostering syncretic practices in rural European and Mediterranean communities into the modern era.[94][95][96]Sociological Patterns of Adherence

Belief in and adherence to fortune-telling practices exhibit distinct sociological patterns, with surveys indicating that approximately 30% of American adults consult astrology, tarot cards, or fortune-tellers at least once a year.[37] This engagement is not uniform but correlates strongly with demographic variables, including gender, age, and socioeconomic status, reflecting broader patterns of vulnerability to uncertainty and limited access to empirical decision-making resources. Gender disparities are pronounced, with women demonstrating higher rates of belief and participation than men; for instance, 43% of U.S. women aged 18 to 49 report belief in astrology, compared to 20% of men in the same age group.[37] Similarly, adherence is elevated among younger cohorts, as 37% of U.S. adults under 30 express belief in astrology, versus lower rates in older populations.[97] These patterns persist across related divinatory beliefs, where self-identified LGBT individuals also show increased propensity for engagement with such practices.[37] Socioeconomic factors further delineate adherence, with lower-income individuals approximately twice as likely to endorse beliefs in astrology (37%) compared to those in upper-income brackets (16%).[37] Education level exhibits a robust inverse correlation, as higher educational attainment—often tied to compulsory schooling reforms—reduces propensity for superstitious beliefs, including reliance on fortune-tellers and lucky charms.[98] [99] Empirical analyses confirm that greater scientific literacy and exposure to rational inquiry diminish endorsement of fortune-telling, positioning it as more prevalent among those with fewer years of formal education or in socio-demographic contexts emphasizing traditionalism over evidence-based reasoning.[100] Cross-nationally, patterns align with social control theories, where marginalized or secularized groups—facing higher instability or weaker institutional ties—display elevated paranormal adherence, including divination.[98] Religiosity and historical factors, such as exposure to communist regimes, also predict higher superstition levels, though these interact with modern urbanization to modulate fortune-telling's appeal in transitional societies.[101] Overall, these patterns underscore fortune-telling's role as a coping mechanism in contexts of informational asymmetry or existential uncertainty, as well as in fostering social cohesion through communal practices, with persistence into contemporary societies for entertainment and emotional support, rather than a uniformly distributed cultural artifact.Manifestations in Play and Entertainment

Fortune-telling motifs emerged in English literature by the late 16th century, with William Shakespeare employing the term "fortune-teller" in The Comedy of Errors (circa 1594), portraying the figure as a "hungry lean-faced villain" engaged in deceitful prophecy.[102] Such depictions often highlighted skepticism toward divinatory claims, aligning with Elizabethan views of soothsayers as charlatans rather than seers. In theater, Charles Johnson's comedy The Female Fortune-Teller (1726), staged at Lincoln's Inn Fields, satirized gender roles in prophecy through a plot involving disguised practitioners and romantic intrigue, reflecting Enlightenment-era mockery of superstition.[103] By the 19th century, fortune-telling infiltrated domestic entertainment as parlor games among the British middle class, including palmistry sessions, tea-leaf reading, and "husband divination" rituals where participants used cards or objects to forecast marital prospects.[104] These activities, documented in periodicals and etiquette manuals, blended amusement with mild occult curiosity but frequently led to legal scrutiny when professionalized, as courts distinguished recreational play from fraudulent commerce. The Ouija board, patented on February 10, 1891, by Elijah Bond in Baltimore, epitomized this shift; marketed by William Fuld as a "wonderful talking board" for family entertainment and spirit contact, it sold approximately 2,000 units weekly by 1891 amid the Spiritualist movement's popularity.[105][106] Initially positioned as a harmless parlor game akin to table-tipping, its mechanics relied on ideomotor effect—subconscious muscle movements—rather than supernatural agency, though later cultural associations with horror eclipsed its origins.[107] In modern board games, fortune-telling elements persist as thematic devices, such as in MASH (reissued 2020 by Spin Master), a card-elimination game simulating life predictions through randomized scenarios, or legacy solitaire titles like Hoki: Fortune Telling (2023), which incorporates prophetic mechanics for solo narrative progression.[108] Video games occasionally integrate divination for gameplay or lore, though empirical analysis reveals these as procedural randomization rather than genuine foresight; for instance, tarot-inspired decision trees in role-playing titles simulate choice outcomes via algorithms, not prescience.[109] Film and television frequently trope fortune-tellers as enigmatic or manipulative archetypes, often in horror or noir genres to underscore human gullibility. In Nightmare Alley (1947 adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham's novel), a carny mentalist exploits clients through cold reading disguised as clairvoyance, a portrayal grounded in mid-20th-century carnival fraud exposés. Tarot readings appear in thrillers like those cataloged in horror analyses, where card interpretations drive plot via confirmation bias, as seen in Penny Dreadful (2014–2016), though dramatized spreads deviate from historical layouts for narrative tension.[110] Such representations, while entertaining, rarely depict empirical validation, instead amplifying psychological ploys like the Forer effect—vague statements perceived as personal insights.[111]Commercial Operations

Professional Practitioners and Services

Professional practitioners in fortune-telling include astrologers, who base predictions on planetary alignments and birth charts; tarot card readers, interpreting symbolic cards drawn from decks like the Rider-Waite-Smith; palmists or chiromancers, examining hand lines and mounts; mediums, purporting to contact deceased individuals; and clairvoyants, claiming extrasensory perception for future insights.[1][27] Other specialties encompass numerologists, using numerical patterns from names and dates, and rune casters, drawing from ancient Nordic symbols.[112] These roles typically involve self-directed learning or apprenticeships rather than formalized education, with practitioners often marketing credentials from non-accredited metaphysical academies. Services are provided via in-person consultations at dedicated parlors or events, telephone hotlines operational since the 1990s for remote access, and online platforms enabling video, chat, or app-based sessions.[113][114] Major networks like Psychic Source and Kasamba connect clients to screened advisors charging $1–$10 per minute, with introductory offers to attract users.[115] Mobile apps, such as those simulating fingerprint or tarot scans, offer automated or live readings for convenience.[116] The U.S. psychic services sector, covering these modalities, reported $2.3 billion in revenue for 2025, driven by a 4% annual growth post-2020 amid rising demand for guidance during uncertainty.[27] Globally, online psychic readings generated $2.2 billion in 2024, with forecasts reaching $5.4 billion by 2031 at a 9.4% CAGR, fueled by digital accessibility.[117] The broader astrology market, overlapping with fortune-telling, stood at $12.8 billion in 2021 and is projected to hit $22.8 billion by 2031.[118] Practitioners frequently specialize in domains like love, career, or health predictions, bundling sessions with ancillary offerings such as aura cleansings or crystal therapies, though empirical validation of efficacy remains absent in controlled studies.[27] Independent operators dominate, with platforms taking commissions of 20–50% on fees, while high-volume hotlines emphasize volume over depth to sustain profitability.[119] In regions like the U.S. and Europe, services target urban demographics via advertising on social media and search engines, adapting to cultural preferences—e.g., Vedic astrology in South Asian markets.[114]Client Demographics and Vulnerabilities

Clients of fortune-telling services predominantly include younger adults, with 14% of U.S. adults under age 30 reporting consultations with fortune tellers compared to 2% of those aged 65 and older, according to a 2025 Pew Research Center survey of over 10,000 adults.[37] Women are significantly more likely to engage than men, with surveys indicating that female respondents outnumber males in psychic consultations by ratios exceeding 2:1 in some datasets.[120] Belief in related practices like astrology, which correlates with fortune-telling use, stands at 37% among those under 30 and is highest among Millennials, per a 2024 Harris Poll finding 70% overall belief but elevated rates in younger cohorts.[121] LGBT adults show elevated reliance, with 21% incorporating such consultations into major life decisions.[37] Socioeconomic and educational factors reveal patterns of lower formal education and intelligence correlating with higher adherence, as a 2025 study in Personality and Individual Differences found that higher IQ and education levels predict disbelief in astrology, with believers averaging lower scores on cognitive tests.[122] Overall, approximately 22-30% of U.S. adults have consulted a fortune teller or psychic at least once, often sporadically rather than habitually, though Generation Z reports 51% engagement with tarot or fortune-telling practices.[123] [124] Vulnerabilities arise from situational stressors, such as grief, financial instability, or life transitions, which prompt seeking external reassurance amid uncertainty, as evidenced by increased consultations during economic downturns reported in industry analyses.[27] [125] Psychological profiles include tendencies toward cognitive distortions like premature negative predictions, mirroring the fortune-telling itself, and contingent self-esteem tied to uncontrollable outcomes, heightening susceptibility to manipulative affirmations or warnings.[126] [127] Case studies document addictive patterns akin to behavioral dependencies, characterized by salience, tolerance, withdrawal, and relapse, where repeated sessions exacerbate financial harm despite recognized futility.[7] [128] These factors enable exploitation through cold reading techniques that exploit universal hopes and fears, particularly in clients with limited critical reasoning tools.[122]Economic Models and Revenue Streams

The fortune-telling industry, often classified under psychic services, primarily generates revenue through fee-based consultations encompassing practices such as tarot card readings, palmistry, astrology, and mediumship. In the United States, total industry revenue reached $2.3 billion in 2025, driven by a compound annual growth rate of 5.5% in prior years, with approximately 85,000 practitioners contributing to this figure through direct client interactions.[27] Globally, the online segment of psychic readings, a key growth area, was valued at $2.8 billion in 2023 and is projected to expand to $5.4 billion by 2031 at a CAGR of 9.4%, reflecting the shift toward digital platforms.[117] Core economic models revolve around pay-per-service structures, with individual sessions typically lasting 30 to 60 minutes and priced between $50 and $200, varying by practitioner experience, location, and method—such as in-person visits versus remote video calls. Pay-per-minute billing predominates in phone and chat-based services, averaging $3 to $5 per minute for established readers, allowing scalability but introducing platform commissions of 20% to 50% in networked models like psychic hotlines or apps. Independent sole proprietorships dominate, benefiting from low overhead costs (primarily marketing and basic props), while larger operations employ subscription tiers for ongoing advisory services, such as daily horoscopes or email updates, to foster client retention and recurring revenue.[129][130][131] Supplementary streams include group events at psychic fairs or private parties, where shorter 15- to 30-minute readings command $20 to $60 per participant, enabling higher volume throughput. Sales of merchandise—tarot decks, crystals, incense, and self-published guides—often bundled with readings or sold online, augment per-client yields by 10% to 30% in diversified businesses. Workshops and downloadable content, such as pre-recorded astrology reports, further extend models toward passive income, though these remain secondary to live consultations, which account for over 70% of total earnings in surveyed operations.[132] Business owners report average annual incomes of $30,000 to $80,000, influenced by client volume and pricing strategy, underscoring the viability of lean, service-centric operations amid minimal fixed costs.[133]Legal Frameworks

Global Regulatory Variations

Regulations on fortune-telling exhibit substantial variation worldwide, often reflecting cultural attitudes toward superstition, fraud prevention, and religious doctrine. In jurisdictions where prohibited, penalties range from fines and imprisonment to severe corporal or capital punishment, typically justified by concerns over deception or incompatibility with state ideology. Conversely, in permissive regions, practice is allowed under consumer protection laws or free speech protections, with enforcement focused on fraudulent intent rather than the activity itself.[134][135] In Saudi Arabia, fortune-telling is outright banned under Islamic law prohibiting sorcery and divination, classified as a form of witchcraft punishable by death; for example, a 2011 execution involved beheading for black magic including fortune-telling elements.[135] Similar prohibitions exist in other strict Islamic states, where such practices are deemed haram and subject to religious police enforcement.[136] Tajikistan has enforced a ban on fortune-telling since 2008, with 2024 amendments introducing penalties of up to six months compulsory labor for practitioners and proposed fines for clients, amid police raids targeting sorcery and faith healing.[137][138] In China, while not explicitly outlawed, fortune-telling falls under public security regulations against disruptive superstitious activities, with historical suppression during the Cultural Revolution giving way to contemporary tolerance for non-fraudulent cultural practices, though large-scale scams trigger penalties.[139][140]| Jurisdiction | Legal Status | Key Provisions |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (Northern Territory, South Australia) | Criminal offense if deceptive | Punishable when intent to defraud is proven; other states regulate via consumer laws.[134] |

| United States (varies by state) | Regulated or prohibited if fraudulent | New York: Class B misdemeanor with up to 90 days jail or $500 fine for scams (1967 law); First Amendment protects non-commercial practice in many areas.[141][142] |

| India | Generally permitted | No central ban; state anti-superstition laws (e.g., Maharashtra 2013) target harm or exploitation, but cultural astrology and palmistry remain unregulated.[143][144] |

| France | Proposed regulation | Government considering oversight for ~100,000 clairvoyants, citing 75% incompetence per industry estimates; currently falls under fraud statutes.[145] |

| United Kingdom | Legal with fraud safeguards | Historical Vagrancy Act provisions repealed; enforced via Fraud Act 2006 for deception, no specific ban on divination.[146] |

_Циганка-ворожка.jpg/250px-Шевченко_Т._Г._(1841)_Циганка-ворожка.jpg)

_Циганка-ворожка.jpg/1534px-Шевченко_Т._Г._(1841)_Циганка-ворожка.jpg)