Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Four-stroke engine

View on Wikipedia

A four-stroke (also four-cycle) engine is an internal combustion (IC) engine in which the piston completes four separate strokes while turning the crankshaft. A stroke refers to the full travel of the piston along the cylinder, in either direction. The four separate strokes are termed:

- Intake: Also known as induction or suction. This stroke of the piston begins at top dead center (T.D.C.) and ends at bottom dead center (B.D.C.). In this stroke the intake valve must be in the open position while the piston pulls an air-fuel mixture into the cylinder by producing a partial vacuum (negative pressure) in the cylinder through its downward motion.

- Compression: This stroke begins at B.D.C, or just at the end of the suction stroke, and ends at T.D.C. In this stroke the piston compresses the air-fuel mixture in preparation for ignition during the power stroke (below). Both the intake and exhaust valves are closed during this stage.

- Combustion: Also known as power or ignition. This is the start of the second revolution of the four stroke cycle. At this point the crankshaft has completed a full 360 degree revolution. While the piston is at T.D.C. (the end of the compression stroke) the compressed air-fuel mixture is ignited by a spark plug (in a gasoline engine) or by heat generated by high compression (diesel engines), forcefully returning the piston to B.D.C. This stroke produces mechanical work from the engine to turn the crankshaft.

- Exhaust: Also known as outlet. During the exhaust stroke, the piston, once again, returns from B.D.C. to T.D.C. while the exhaust valve is open. This action expels the spent air-fuel mixture through the exhaust port.

Four-stroke engines are the most common internal combustion engine design for motorized land transport,[1] being used in automobiles, trucks, diesel trains, light aircraft and motorcycles. The major alternative design is the two-stroke cycle.[1]

History

[edit]Otto cycle

[edit]

Nikolaus August Otto was a traveling salesman for a grocery concern. In his travels, he encountered the internal combustion engine built in Paris by Belgian expatriate Jean Joseph Etienne Lenoir. In 1860, Lenoir successfully created a double-acting engine that ran on illuminating gas at 4% efficiency. The 18 litre Lenoir Engine produced only 2 horsepower. The Lenoir engine ran on illuminating gas made from coal, which had been developed in Paris by Philip Lebon.[2]

In testing a replica of the Lenoir engine in 1861, Otto became aware of the effects of compression on the fuel charge. In 1862, Otto attempted to produce an engine to improve on the poor efficiency and reliability of the Lenoir engine. He tried to create an engine that would compress the fuel mixture prior to ignition, but failed as that engine would run no more than a few minutes prior to its destruction. Many other engineers were trying to solve the problem, with no success.[2]

In 1864, Otto and Eugen Langen founded the first internal combustion engine production company, NA Otto and Cie (NA Otto and Company). Otto and Cie succeeded in creating a successful atmospheric engine that same year.[2] The factory ran out of space and was moved to the town of Deutz, Germany in 1869, where the company was renamed to Deutz Gasmotorenfabrik AG (The Deutz Gas Engine Manufacturing Company).[2] In 1872, Gottlieb Daimler was technical director and Wilhelm Maybach was the head of engine design. Daimler was a gunsmith who had worked on the Lenoir engine. By 1876, Otto and Langen succeeded in creating the first internal combustion engine that compressed the fuel mixture prior to combustion for far higher efficiency than any engine created to this time.

Daimler and Maybach left their employ at Otto and Cie and developed the first high-speed Otto engine in 1883. In 1885, they produced the first automobile to be equipped with an Otto engine. The Daimler Reitwagen used a hot-tube ignition system and the fuel known as Ligroin to become the world's first vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine. It used a four-stroke engine based on Otto's design. The following year, Karl Benz produced a four-stroke engined automobile that is regarded as the first car.[3]

In 1884, Otto's company, then known as Gasmotorenfabrik Deutz (GFD), developed electric ignition and the carburetor. In 1890, Daimler and Maybach formed a company known as Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft. Today, that company is Daimler-Benz.

Atkinson cycle

[edit]

The Atkinson-cycle engine is a type of single stroke internal combustion engine invented by James Atkinson in 1882. The Atkinson cycle is designed to provide efficiency at the expense of power density, and is used in some modern hybrid electric applications.

The original Atkinson-cycle piston engine allowed the intake, compression, power, and exhaust strokes of the four-stroke cycle to occur in a single turn of the crankshaft and was designed to avoid infringing certain patents covering Otto-cycle engines.[4]

Due to the unique crankshaft design of the Atkinson, its expansion ratio can differ from its compression ratio and, with a power stroke longer than its compression stroke, the engine can achieve greater thermal efficiency than a traditional piston engine. While Atkinson's original design is no more than a historical curiosity, many modern engines use unconventional valve timing to produce the effect of a shorter compression stroke/longer power stroke, thus realizing the fuel economy improvements the Atkinson cycle can provide.[5]

Diesel cycle

[edit]

The diesel engine is a technical refinement of the 1876 Otto-cycle engine. Where Otto had realized in 1861 that the efficiency of the engine could be increased by first compressing the fuel mixture prior to its ignition, Rudolf Diesel wanted to develop a more efficient type of engine that could run on much heavier fuel. The Lenoir, Otto Atmospheric, and Otto Compression engines (both 1861 and 1876) were designed to run on Illuminating Gas (coal gas). With the same motivation as Otto, Diesel wanted to create an engine that would give small industrial companies their own power source to enable them to compete against larger companies, and like Otto, to get away from the requirement to be tied to a municipal fuel supply.[citation needed] Like Otto, it took more than a decade to produce the high-compression engine that could self-ignite fuel sprayed into the cylinder. Diesel used an air spray combined with fuel in his first engine.

During initial development, one of the engines burst, nearly killing Diesel. He persisted, and finally created a successful engine in 1893. The high-compression engine, which ignites its fuel by the heat of compression, is now called the diesel engine, whether a four-stroke or two-stroke design.

The four-stroke diesel engine has been used in the majority of heavy-duty applications for many decades. It uses a heavy fuel containing more energy and requiring less refinement to produce. The most efficient Otto-cycle engines run near 30% thermal efficiency.[clarification needed]

Thermodynamic analysis

[edit]

The thermodynamic analysis of the actual four-stroke and two-stroke cycles is not a simple task. However, the analysis can be simplified significantly if air standard assumptions[6] are utilized. The resulting cycle, which closely resembles the actual operating conditions, is the Otto cycle.

During normal operation of the engine, as the air/fuel mixture is being compressed, an electric spark is created to ignite the mixture. At low rpm this occurs close to TDC (Top Dead Centre). As engine rpm rises, the speed of the flame front does not change so the spark point is advanced earlier in the cycle to allow a greater proportion of the cycle for the charge to combust before the power stroke commences. This advantage is reflected in the various Otto engine designs; the atmospheric (non-compression) engine operates at 12% efficiency whereas the compressed-charge engine has an operating efficiency around 30%.

Fuel considerations

[edit]A problem with compressed charge engines is that the temperature rise of the compressed charge can cause pre-ignition. If this occurs at the wrong time and is too energetic, it can damage the engine. Different fractions of petroleum have widely varying flash points (the temperatures at which the fuel may self-ignite). This must be taken into account in engine and fuel design.

The tendency for the compressed fuel mixture to ignite early is limited by the chemical composition of the fuel. There are several grades of fuel to accommodate differing performance levels of engines. The fuel is altered to change its self-ignition temperature. There are several ways to do this. As engines are designed with higher compression ratios the result is that pre-ignition is much more likely to occur since the fuel mixture is compressed to a higher temperature prior to deliberate ignition. The higher temperature more effectively evaporates fuels such as gasoline, which increases the efficiency of the compression engine. Higher compression ratios also mean that the distance that the piston can push to produce power is greater (which is called the expansion ratio).

The octane rating of a given fuel is a measure of the fuel's resistance to self-ignition. A fuel with a higher numerical octane rating allows for a higher compression ratio, which extracts more energy from the fuel and more effectively converts that energy into useful work while at the same time preventing engine damage from pre-ignition. High octane fuel is also more expensive.

Many modern four-stroke engines employ gasoline direct injection or GDI. In a gasoline direct-injected engine, the injector nozzle protrudes into the combustion chamber. The direct fuel injector injects gasoline under a very high pressure into the cylinder during the compression stroke, when the piston is closer to the top.[7]

Diesel engines by their nature do not have concerns with pre-ignition. They have a concern with whether or not combustion can be started. The description of how likely diesel fuel is to ignite is called the Cetane rating. Because diesel fuels are of low volatility, they can be very hard to start when cold. Various techniques are used to start a cold diesel engine, the most common being the use of a glow plug.

Design and engineering principles

[edit]Power output limitations

[edit]

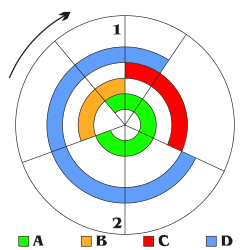

1=TDC

2=BDC

A: Intake

B: Compression

C: Power

D: Exhaust

The maximum amount of power generated by an engine is determined by the maximum amount of air ingested. The amount of power generated by a piston engine is related to its size (cylinder volume), whether it is a two-stroke engine or four-stroke design, volumetric efficiency, losses, air-to-fuel ratio, the calorific value of the fuel, oxygen content of the air and speed (RPM). The speed is ultimately limited by material strength and lubrication. Valves, pistons and connecting rods suffer severe acceleration forces. At high engine speed, physical breakage and piston ring flutter can occur, resulting in power loss or even engine destruction. Piston ring flutter occurs when the rings oscillate vertically within the piston grooves they reside in. Ring flutter compromises the seal between the ring and the cylinder wall, which causes a loss of cylinder pressure and power. If an engine spins too quickly, valve springs cannot act quickly enough to close the valves. This is commonly referred to as 'valve float', and it can result in piston to valve contact, severely damaging the engine. At high speeds the lubrication of piston cylinder wall interface tends to break down. This limits the piston speed for industrial engines to about 10 m/s.

Intake/exhaust port flow

[edit]The output power of an engine is dependent on the ability of intake (air–fuel mixture) and exhaust matter to move quickly through valve ports, typically located in the cylinder head. To increase an engine's output power, irregularities in the intake and exhaust paths, such as casting flaws, can be removed, and, with the aid of an air flow bench, the radii of valve port turns and valve seat configuration can be modified to reduce resistance. This process is called porting, and it can be done by hand or with a CNC machine.

Waste heat recovery of an internal combustion engine

[edit]An internal combustion engine is on average capable of converting only 40-45% of supplied energy into mechanical work. A large part of the waste energy is in the form of heat that is released to the environment through coolant, fins, etc. If somehow waste heat could be captured and turned to mechanical energy, the engine's performance and/or fuel efficiency could be improved by improving the overall efficiency of the cycle. It has been found that even if 6% of the entirely wasted heat is recovered it can increase the engine efficiency greatly.[8]

Many methods have been devised in order to extract waste heat out of an engine exhaust and use it further to extract some useful work, decreasing the exhaust pollutants at the same time. Use of the Rankine Cycle, turbocharging and thermoelectric generation can be very useful as a waste heat recovery system.

Supercharging

[edit]One way to increase engine power is to force more air into the cylinder so that more power can be produced from each power stroke. This can be done using some type of air compression device known as a supercharger, which can be powered by the engine crankshaft.

Supercharging increases the power output limits of an internal combustion engine relative to its displacement. Most commonly, the supercharger is always running, but there have been designs that allow it to be cut out or run at varying speeds (relative to engine speed). Mechanically driven supercharging has the disadvantage that some of the output power is used to drive the supercharger, while power is wasted in the high pressure exhaust, as the air has been compressed twice and then gains more potential volume in the combustion but it is only expanded in one stage.

Turbocharging

[edit]A turbocharger is a supercharger that is driven by the engine's exhaust gases, by means of a turbine. A turbocharger is incorporated into the exhaust system of a vehicle to make use of the expelled exhaust. It consists of a two-piece, high-speed turbine assembly with one side that compresses the intake air, and the other side that is powered by the exhaust gas outflow.

When idling, and at low-to-moderate speeds, the turbine produces little power from the small exhaust volume, the turbocharger has little effect and the engine operates nearly in a naturally aspirated manner. When much more power output is required, the engine speed and throttle opening are increased until the exhaust gases are sufficient to 'spool up' the turbocharger's turbine to start compressing much more air than normal into the intake manifold. Thus, additional power (and speed) is expelled through the function of this turbine.

Turbocharging allows for more efficient engine operation because it is driven by exhaust pressure that would otherwise be (mostly) wasted, but there is a design limitation known as turbo lag. The increased engine power is not immediately available due to the need to sharply increase engine RPM, to build up pressure and to spin up the turbo, before the turbo starts to do any useful air compression. The increased intake volume causes increased exhaust and spins the turbo faster, and so forth until steady high power operation is reached. Another difficulty is that the higher exhaust pressure causes the exhaust gas to transfer more of its heat to the mechanical parts of the engine.

Rod and piston-to-stroke ratio

[edit]The rod-to-stroke ratio is the ratio of the length of the connecting rod to the length of the piston stroke. A longer rod reduces sidewise pressure of the piston on the cylinder wall and the stress forces, increasing engine life. It also increases the cost and engine height and weight.

A "square engine" is an engine with a bore diameter equal to its stroke length. An engine where the bore diameter is larger than its stroke length is an oversquare engine, conversely, an engine with a bore diameter that is smaller than its stroke length is an undersquare engine.

Valve train

[edit]The valves are typically operated by a camshaft rotating at half the speed of the crankshaft. It has a series of cams along its length, each designed to open a valve during the appropriate part of an intake or exhaust stroke. A tappet between valve and cam is a contact surface on which the cam slides to open the valve. Many engines use one or more camshafts "above" a row (or each row) of cylinders, as in the illustration, in which each cam directly actuates a valve through a flat tappet. In other engine designs the camshaft is in the crankcase, in which case each cam usually contacts a push rod, which contacts a rocker arm that opens a valve, or in case of a flathead engine a push rod is not necessary. The overhead cam design typically allows higher engine speeds because it provides the most direct path between cam and valve.

Valve clearance

[edit]Valve clearance refers to the small gap between a valve lifter and a valve stem that ensures that the valve completely closes. On engines with mechanical valve adjustment, excessive clearance causes noise from the valve train. A too-small valve clearance can result in the valves not closing properly. This results in a loss of performance and possibly overheating of exhaust valves. Typically, the clearance must be readjusted each 20,000 miles (32,000 km) with a feeler gauge.

Most modern production engines use hydraulic lifters to automatically compensate for valve train component wear. Dirty engine oil may cause lifter failure.

Energy balance

[edit]Otto engines are about 30% efficient; in other words, 30% of the energy generated by combustion is converted into useful rotational energy at the output shaft of the engine, while the remainder being lost due to waste heat, friction and engine accessories.[9] There are a number of ways to recover some of the energy lost to waste heat. The use of a turbocharger in diesel engines is very effective by boosting incoming air pressure and in effect, provides the same increase in performance as having more displacement. The Mack Truck company, decades ago, developed a turbine system that converted waste heat into kinetic energy that it fed back into the engine's transmission. In 2005, BMW announced the development of the turbosteamer, a two-stage heat-recovery system similar to the Mack system that recovers 80% of the energy in the exhaust gas and raises the efficiency of an Otto engine by 15%.[10] By contrast, a six-stroke engine may reduce fuel consumption by as much as 40%.

Modern engines are often intentionally built to be slightly less efficient than they could otherwise be. This is necessary for emission controls such as exhaust gas recirculation and catalytic converters that reduce smog and other atmospheric pollutants. Reductions in efficiency may be counteracted with an engine control unit using lean burn techniques.[11]

In the United States, the Corporate Average Fuel Economy mandates that vehicles must achieve an average of 34.9 mpg‑US (6.7 L/100 km; 41.9 mpg‑imp) compared to the current standard of 25 mpg‑US (9.4 L/100 km; 30.0 mpg‑imp).[12] As automakers look to meet these standards by 2016, new ways of engineering the traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) have to be considered. Some potential solutions to increase fuel efficiency to meet new mandates include firing after the piston is farthest from the crankshaft, known as top dead centre, and applying the Miller cycle. Together, this redesign could significantly reduce fuel consumption and NOx emissions.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "4-STROKE ENGINES: WHAT ARE THEY AND HOW DO THEY WORK?". UTI. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "125 Jahre Viertaktmotor" [125 Years of the Four Stroke Engine]. Oldtimer Club Nicolaus August Otto e.V. (in German). Germany. 2009. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011.

- ^ Ralph Stein (1967). The Automobile Book. Paul Hamlyn Ltd

- ^ US 367496, J. Atkinson, "Gas Engine", issued 2 August 1887

- ^ "Auto Tech: Atkinson Cycle engines and Hybrids". Autos.ca. 14 July 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Best Place for Engineering and Technology, Air Standard Assumptions". Archived from the original on 21 April 2011.

- ^ "Four-stroke engine: how it works, animation". testingautos.com. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Sprouse III, Charles; Depcik, Christopher (1 March 2013). "Review of organic Rankine cycles for internal combustion engine exhaust waste heat recovery". Applied Thermal Engineering. 51 (1–2): 711–722. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2012.10.017.

- ^ Ferreira, Omar Campos (March 1998). "Efficiencies of Internal Combustion Engines". Economia & Energia (in Portuguese). Brasil. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ^ Neff, John (9 December 2005). "BMW Turbo Steamer Gets Hot and Goes". Autoblog. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ^ Faiz, Asif; Weaver, Christopher S.; Walsh, Michael P. (1996). Air pollution from motor vehicles: Standards and Technologies for Controlling Emissions. World Bank Publications. ISBN 9780821334447.

- ^ "Fuel Economy". US: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Retrieved 11 April 2016.

General sources

[edit]- Hardenberg, Horst O. (1999). The Middle Ages of the Internal combustion Engine. Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE). ISBN 978-0-7680-0391-8.

- scienceworld.wolfram.com/physics/OttoCycle.html

- Cengel, Yunus A; Michael A Boles; Yaling He (2009). Thermodynamics An Engineering Approach. N.p. The McGraw Hill Companies. ISBN 978-7-121-08478-2.

- Benson, Tom (11 July 2008). "4 Stroke Internal Combustion Engine". p. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

External links

[edit]- U.S. patent 194,047

- Four stroke engine animation

- Detailed Engine Animations

- How Car Engines Work

- Animated Engines, four stroke, another explanation of the four-stroke engine.

- CDX eTextbook, some videos of car components in action.

- New 4 stroke

- Engine Four Stroke Internal Combustion Engine

Four-stroke engine

View on GrokipediaHistory

Invention and early development

The theoretical basis for the four-stroke cycle was first articulated by French engineer Alphonse Beau de Rochas, who patented the principle on January 16, 1862, outlining intake, compression, power, and exhaust strokes for improved efficiency in gas engines, though he constructed no working prototype.[6] This concept built on earlier single-stroke designs like Étienne Lenoir's 1860 atmospheric engine but emphasized compression to enhance thermodynamic performance.[7] German engineer Nikolaus August Otto pursued practical internal combustion engines from the early 1860s, initially developing a failed compressed-charge prototype in 1861 and later partnering with Eugen Langen to produce a more efficient free-piston atmospheric engine in 1864.[4] By 1876, at the Gasmotoren-Fabrik Deutz in Cologne, Otto engineered the first viable four-stroke engine, achieving its initial successful run in early March of that year; this compressed-charge design operated on coal gas, delivering about 3 horsepower at 180 RPM with significantly higher thermal efficiency—around 12-15%—compared to prior engines' 4%.[8] The engine featured a horizontal single-cylinder configuration with slide valves and electric ignition, patented later in 1876 after resolving prior art challenges.[9] Early development focused on stationary applications for factories and farms, with Deutz producing over 50 units by 1884, incorporating refinements like improved carburetion for liquid fuels.[4] Otto's innovation displaced steam engines in many low-power uses due to its compact size, lower fuel consumption, and elimination of boilers, though initial models suffered from low speed and vibration issues addressed in subsequent iterations.[10] Legal disputes over the patent, including claims referencing Beau de Rochas' work, were ultimately upheld in Otto's favor in Germany, enabling widespread licensing across Europe.[8]Key thermodynamic cycles

The Otto cycle serves as the ideal thermodynamic model for spark-ignition four-stroke engines, consisting of four processes: isentropic compression from bottom dead center to top dead center, constant-volume heat addition via spark ignition, isentropic expansion driving the piston downward, and constant-volume heat rejection during exhaust.[11] This cycle approximates the operation of gasoline engines, where fuel-air mixture is compressed to a ratio typically between 8:1 and 12:1 before ignition to avoid autoignition knock. The thermal efficiency of the ideal Otto cycle is given by η = 1 - (1/r)^{γ-1}, where r is the compression ratio and γ ≈ 1.4 for air-fuel mixtures; higher r increases efficiency but is limited by material strength and detonation risks.[11] In contrast, the Diesel cycle models compression-ignition four-stroke engines, featuring isentropic compression, constant-pressure heat addition as fuel injects into hot compressed air, isentropic expansion, and constant-volume heat rejection.[12] Diesel engines achieve compression ratios of 14:1 to 25:1, enabling higher efficiencies through greater expansion work extraction without pre-ignition issues, though for identical r, Otto efficiency exceeds Diesel due to earlier heat addition timing.[13] The ideal Diesel efficiency formula is η = 1 - (1/r)^{γ-1} \cdot \frac{ρ^γ - 1}{γ(ρ - 1)}, with ρ as the cutoff ratio (volume at end of heat addition over compressed volume); real Diesel engines convert 35-45% of fuel energy to work, outperforming Otto's 25-30% under practical loads.[14] Variations like the Atkinson cycle modify the Otto process for improved efficiency in four-stroke engines, particularly hybrids, by extending the expansion stroke beyond the compression stroke via late intake valve closure, reducing pumping losses but sacrificing power density.[15] Patented in 1882, modern implementations in engines like Toyota's Prius achieve effective expansion ratios up to 1.5 times the geometric compression ratio, yielding efficiencies 5-10% higher than standard Otto at part loads through over-expansion.[16] The Miller cycle, a supercharged Atkinson variant, further boosts intake air density to compensate for volumetric inefficiency.Commercial adoption and engineering milestones

Following the successful demonstration of Nikolaus Otto's four-stroke engine in March 1876, commercial production commenced at N.A. Otto & Cie (later Deutz AG) for stationary applications, where the engines powered industrial machinery, gas works, and early electric generators using coal gas as fuel.[8][17] These low-speed, large-displacement units, typically single-cylinder, achieved widespread adoption in Europe by the early 1880s due to their superior efficiency over prior atmospheric engines.[4] Engineering adaptations for higher speeds enabled vehicular use; in 1885, Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach developed a compact, high-revving four-stroke engine producing 0.5 horsepower at 900 rpm for Daimler's Reitwagen motorcycle, marking the first mobile application.[18] The following year, Karl Benz installed a similar single-cylinder four-stroke unit (954 cc, 0.75 horsepower) in his Patent-Motorwagen, patented on January 29, 1886, recognized as the first practical automobile.[19] This transition from stationary to transport roles spurred rapid commercialization, with Benz producing about 25 units by 1893.[19] Key milestones included multi-cylinder designs for smoother operation; Wilhelm Maybach constructed the first production four-cylinder four-stroke engine in 1890 for Daimler applications.[18] Valve train advancements followed, with overhead camshaft (OHC) configurations appearing in 1902 on the Marr Auto Car's single-cylinder engine, allowing higher revs and better breathing.[20] Overhead valve (OHV) pushrod systems, patented in 1902 by Buick engineer Eugene Richard (awarded 1904), improved efficiency in mass-produced engines like the 1904 Ford Model B, Ford's first four-cylinder offering.[21][22] Aviation adoption accelerated development; the Wright brothers' 1903 Flyer featured a custom inline four-cylinder four-stroke engine delivering 12 horsepower, enabling the first powered flight on December 17, 1903.[23] By the 1910s, four-stroke engines dominated automotive production, exemplified by the 1908 Ford Model T's 177 ml inline-four, which facilitated mass adoption with over 15 million units built until 1927, transforming personal transport.[22] These advancements in cylinder configuration, valvetrain geometry, and power density established the four-stroke cycle as the foundational technology for internal combustion propulsion through the mid-20th century.Operating Principle

The four strokes

The four-stroke cycle of a reciprocating internal combustion engine comprises intake, compression, power, and exhaust strokes, executed over two full crankshaft revolutions to convert chemical energy in fuel into mechanical work.[2] This sequence ensures separation of gas exchange and combustion processes, enabling higher efficiency compared to two-stroke designs by reducing short-circuiting of fresh charge with exhaust gases.[1] In spark-ignition engines operating on the Otto cycle, the process begins with the piston at top dead center (TDC).[2] Intake stroke: The piston descends from TDC to bottom dead center (BDC) while the intake valve opens, creating a partial vacuum that draws the air-fuel mixture into the cylinder through the intake port.[2] The intake valve remains closed during the subsequent strokes to isolate the cylinder contents. Volumetric efficiency, typically 80-90% in naturally aspirated engines, determines the mass of charge inducted, influenced by intake manifold design and throttle position.[1] Compression stroke: With both valves closed, the piston rises from BDC to TDC, compressing the air-fuel mixture to increase its temperature and pressure, preparing it for ignition.[2] Compression ratios in gasoline engines range from 8:1 to 12:1, balancing efficiency gains against knock propensity.[24] The work input during this stroke is recovered partially in the expansion phase, per the Otto cycle thermodynamics.[2] Power stroke: Near TDC, the spark plug ignites the compressed mixture, causing rapid combustion that elevates cylinder pressure to 50-100 bar, forcing the piston downward to BDC and delivering torque to the crankshaft via the connecting rod.[2] This expansion stroke produces the net positive work of the cycle, with peak pressures occurring 10-15 degrees after TDC for optimal mechanical efficiency.[1] In diesel four-stroke engines, ignition occurs via compression heating without a spark, accommodating higher ratios up to 20:1.[23] Exhaust stroke: The piston ascends from BDC to TDC with the exhaust valve open, expelling combustion products through the exhaust port to the manifold.[2] Residual exhaust gas fraction, around 5-10%, affects subsequent cycle efficiency and emissions.[1] Valve overlap—brief simultaneous opening of intake and exhaust valves near TDC—scavenges residuals and initiates intake, tuned via camshaft phasing for specific engine speeds. The cycle repeats, with timing controlled by the valvetrain synchronized to crankshaft rotation at half speed.[2]Cycle variations and mechanics

The Otto cycle governs the operation of most spark-ignition four-stroke engines, featuring isentropic compression followed by constant-volume heat addition via spark ignition, isentropic expansion, and constant-volume heat rejection.[24] This cycle achieves thermal efficiencies typically around 30% in practical applications due to limitations in compression ratios, limited to 8:1 to 12:1 to avoid knocking.[25] In contrast, the Diesel cycle applies to compression-ignition four-stroke engines, where heat addition occurs at constant pressure after high compression ratios of 14:1 to 25:1, enabling auto-ignition of diesel fuel without spark.[25] This configuration yields higher thermal efficiencies, often exceeding 40% in heavy-duty variants, as the greater expansion ratio extracts more work from combustion gases before exhaust.[25] The Atkinson cycle, patented by James Atkinson in 1882, deviates from the Otto cycle by extending the expansion stroke relative to compression through delayed intake valve closure, which reduces effective compression volume and pumping losses while preserving a longer power stroke for improved thermodynamic efficiency.[26] Modern engines achieve this via variable valve timing, operating in Atkinson mode under light loads for fuel economy gains of up to 10-15% over standard Otto cycles, though at reduced torque output.[27] The Miller cycle, introduced by Ralph Miller in 1957, employs early or late intake valve closing combined with supercharging to limit trapped air mass during compression, mimicking Atkinson's expansion advantage while compensating for power loss through forced induction.[28] This results in elevated expansion ratios and efficiencies approaching those of Atkinson designs, particularly in boosted applications, with valve timing shifts altering the intake event to refrigerate the charge and lower peak temperatures.[28]Thermodynamic Analysis

Ideal vs. real cycle efficiency

The ideal Otto cycle, which models the four-stroke spark-ignition engine under air-standard assumptions, posits reversible adiabatic compression and expansion processes, instantaneous constant-volume heat addition during combustion, and constant-volume heat rejection, with the working fluid as an ideal gas exhibiting constant specific heats. These assumptions yield a thermal efficiency of , where is the volumetric compression ratio and is the ratio of specific heats for air. For practical compression ratios of 8 to 12 in gasoline engines—limited by knock to avoid auto-ignition—this formula predicts efficiencies of approximately 56% to 60%.[24][11] Real four-stroke engines achieve brake thermal efficiencies of 25% to 35% for gasoline spark-ignition variants and up to 40% to 45% for compression-ignition diesel types, reflecting substantial deviations from ideal conditions due to irreversibilities, non-ideal gas behavior, and parasitic losses. Indicated thermal efficiency, measured at the crankshaft before mechanical deductions, reaches 35% to 40% in optimized spark-ignition engines but is eroded by factors such as variable specific heats (reducing effective to below 1.3 at combustion temperatures exceeding 2000 K), chemical dissociation of combustion products, and incomplete fuel-air mixing.[29][30][31] Key losses include heat transfer to cylinder walls and coolant (20% to 30% of fuel energy, exacerbated by finite combustion duration and surface-area-to-volume ratios), mechanical friction from piston rings, bearings, and valvetrain (5% to 10% penalty on indicated work), and pumping work during throttled intake and exhaust strokes (up to 10% at part load in spark-ignition engines). Additional reductions stem from blow-by gases escaping past rings (1% to 3% fuel loss), incomplete combustion (2% to 5% at low loads), and exhaust residuals diluting the charge. Diesel cycles benefit from higher compression ratios (14 to 22), approaching ideal efficiencies closer to 65%, but still incur analogous losses scaled by their constant-pressure heat addition.[32][33][31]| Loss Mechanism | Typical Magnitude (% of Fuel Energy) | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Heat transfer | 20–30 | Conduction to walls during finite-rate combustion and expansion[32] |

| Mechanical friction | 5–10 | Viscous drag in lubricated contacts, valvetrain inertia[33] |

| Pumping | 5–10 (part load) | Throttling and backpressure in intake/exhaust[34] |

| Incomplete combustion/blow-by | 3–8 | Finite mixing, crevice volumes, ring leakage[31] |

Losses and performance factors

In real four-stroke engines operating on the Otto cycle, efficiency deviates from the ideal thermodynamic prediction due to several irreversible losses, primarily frictional dissipation, gas pumping work, heat transfer to surroundings, and incomplete combustion. Frictional losses arise from mechanical interactions such as piston ring-cylinder wall contact, crankshaft bearings, and valve train components, consuming 5-15% of indicated power depending on engine speed and load; these increase quadratically with rotational speed due to viscous drag and account for higher specific fuel consumption at elevated RPMs.[36][25] Pumping losses, unique to four-stroke cycles, stem from the net work required for intake and exhaust strokes, exacerbated in spark-ignition engines by throttling to control load, which creates a sub-atmospheric intake pressure and positive exhaust backpressure, resulting in a negative loop on the pressure-volume diagram that can consume up to 10-20% of gross indicated work at part throttle.[31][36] Heat transfer losses occur via convection and radiation from hot combustion gases to cylinder walls, piston crowns, and heads, with rates peaking during the power stroke; these typically dissipate 20-30% of fuel energy, influenced by thermal boundary layers and metal temperatures around 500-600 K, reducing the effective expansion ratio.[25][37] Additional losses include blow-by gases escaping past piston rings into the crankcase (1-5% of intake charge) and incomplete combustion from finite flame speeds and quench layers near walls, leading to unburned hydrocarbons and chemical energy losses in exhaust (5-10% of fuel input). Performance factors mitigating these include higher compression ratios (typically 8:1 to 12:1 in gasoline engines), which boost thermal efficiency per the relation η = 1 - (1/r)^{γ-1} (where γ ≈ 1.4 for air-fuel mixtures) by expanding gases closer to adiabatic conditions, though limited by autoignition knock to avoid pre-ignition.[25][38] Optimized air-fuel ratios near stoichiometric (14.7:1 for gasoline) minimize incomplete combustion, while advanced ignition timing advances peak pressure for better work extraction, and longer stroke-to-bore ratios reduce relative heat transfer surface area, enhancing efficiency by 2-5% in opposed-piston designs.[39][40] Variable valve timing reduces pumping losses by 5-10% at part loads through late intake valve closing, akin to Atkinson cycle extensions.[29] Overall, these factors yield brake thermal efficiencies of 25-35% in modern automotive four-stroke engines under optimal conditions, far below the 60% ideal Otto limit at r=10.[31][25]Design and Engineering Principles

Core components and assembly

The cylinder block serves as the foundational structure of a four-stroke engine, typically cast from iron or aluminum alloy, housing the cylinders where pistons reciprocate and supporting the crankshaft via main bearings.[41] It integrates the crankcase below the cylinders to contain lubricating oil and often includes coolant passages for thermal management.[42] Pistons, usually constructed from lightweight aluminum alloys, fit snugly within the cylinders and are equipped with rings to seal combustion gases, scrape oil from walls, and facilitate heat transfer.[41] Each piston connects to a connecting rod via a wrist pin, allowing pivotal motion, while the rod's lower end attaches to the crankshaft throw with a bearing for high-load rotation.[42] Forged steel connecting rods transmit the explosive forces from combustion, converting the piston's linear motion into the crankshaft's rotary output.[41] The crankshaft, forged from high-strength steel with counterweights for balance, rotates within the block's main bearings, transforming reciprocating piston forces into torque for propulsion.[42] The cylinder head, bolted atop the block with a gasket for sealing, encloses the combustion chamber and houses valvetrain elements including intake and exhaust valves.[41] These poppet valves, made of heat-resistant alloys, control charge admission and exhaust expulsion, held closed by coil springs against machined seats.[43] Assembly begins with installing the crankshaft into the cylinder block's bearings, followed by attaching connecting rods to its throws.[41] Pistons, fitted with rings and pinned to rods, are then inserted into cylinders and secured to the crankshaft.[42] The cylinder head is positioned with a multi-layer steel or composite gasket and torqued to specifications, integrating ports for intake, exhaust, and spark ignition.[41] The valvetrain assembly varies by configuration: in overhead valve (OHV) designs, the camshaft mounts in the block, actuating valves via lifters, pushrods, and rocker arms in the head; overhead cam (OHC) places the camshaft directly in the head for shorter, stiffer paths using bucket tappets or finger followers.[43] The camshaft, driven by timing chain or belt from the crankshaft at half speed, profiles lobe shapes to dictate valve timing, lift, and duration essential for efficient four-stroke operation.[43] Precision alignment during assembly ensures synchronization, preventing valve-piston interference.[44]Valve train and timing systems

The valve train, also known as the valvetrain, comprises the mechanical assembly responsible for opening and closing the intake and exhaust valves in a four-stroke engine to regulate the admission of the air-fuel mixture and expulsion of combustion gases. Core components include the camshaft, which features eccentrically shaped lobes that dictate valve lift and duration; cam followers or tappets that transmit motion from the camshaft; pushrods and rocker arms in certain configurations; poppet valves typically made of high-strength steel or alloys; coil springs to return valves to their seats; and hydraulic lash adjusters or solid lifters to maintain precise clearance. These elements ensure valves operate in synchrony with the crankshaft, with the camshaft driven at half crankshaft speed via a timing chain, belt, or gears to match the four-stroke cycle.[45][46] Valve train architectures vary by camshaft placement relative to the valves. In overhead valve (OHV) designs, also termed pushrod engines, the camshaft resides in the engine block, actuating valves in the cylinder head via pushrods and rocker arms; this configuration offers compact head design, lower production costs, and superior low-speed torque due to optimized leverage, though it incurs higher inertial mass limiting maximum engine speeds to around 6,000-7,000 rpm. Overhead camshaft (OHC) systems position the camshaft in the head for direct or near-direct valve actuation, subdivided into single overhead camshaft (SOHC) for both intake and exhaust valves or dual overhead camshaft (DOHC) with separate cams per valve type; OHC variants enable higher rev limits exceeding 8,000 rpm, improved airflow via straighter ports, and potential for four valves per cylinder, albeit at increased complexity and cost. DOHC engines, common in high-performance applications since the 1980s, facilitate independent control of intake and exhaust phasing for enhanced volumetric efficiency across rpm ranges.[47][48] Timing systems govern the precise phasing of valve events relative to piston position, with intake valves typically opening 10-20° before top dead center (BTDC) on the intake stroke and closing 40-70° after bottom dead center (ABDC), while exhaust valves open 40-70° before bottom dead center (BBDC) on the power stroke and close 10-20° after top dead center (ATDC) to optimize filling and scavenging without excessive overlap that risks charge dilution. Fixed timing suits basic engines but compromises efficiency; variable valve timing (VVT) addresses this by dynamically adjusting camshaft phase, lift, or duration using mechanisms like vane-type phasers actuated by engine oil pressure or electric motors, improving low-end torque by up to 10-15% and fuel economy by 5-10% via optimized timing maps. Pioneered in production by Alfa Romeo's Twin Cam in the 1950s for mechanical advance and refined electronically in Honda's VTEC system introduced in 1989, VVT has proliferated, with systems like BMW's VANOS (1992) and Toyota's VVT-i (1996) demonstrating causal links to broader power bands and reduced emissions through better combustion control.[49][50]Boosting and airflow optimization

Forced induction, commonly referred to as boosting, enhances the power output of four-stroke engines by elevating intake manifold pressure above atmospheric levels, thereby increasing the mass of air (and consequently fuel) per cycle. This is achieved through devices that compress incoming air, with turbochargers utilizing exhaust gas energy to drive a turbine-linked compressor, recovering otherwise wasted thermal energy from the exhaust stream.[51] Superchargers, in contrast, are mechanically driven by the engine crankshaft via belts or gears, providing immediate boost response without reliance on exhaust flow but incurring direct parasitic power losses typically ranging from 10 to 20 percent of engine output.[52] In diesel four-stroke engines, turbocharging is particularly prevalent due to their higher exhaust temperatures and compression ratios, enabling boost pressures up to 3-4 bar in modern heavy-duty applications, which can yield brake thermal efficiencies exceeding 45 percent under optimized loads.[53] Turbocharger efficiency hinges on matching compressor and turbine maps to engine operating conditions, with advancements like variable geometry turbines (VGT) adjusting vane angles to reduce lag and broaden the torque curve across RPM ranges. For instance, VGT systems in automotive diesels can minimize turbo lag to under 0.5 seconds at low speeds while preventing overboost at high loads, improving transient response by up to 30 percent compared to fixed-geometry units.[51] Twin-scroll turbochargers further optimize airflow by separating exhaust pulses from cylinder banks, preserving kinetic energy and enhancing low-end torque by 15-20 percent in inline-four engines. Superchargers, often positive displacement types like Roots or screw compressors, excel in high-RPM power delivery for spark-ignition engines, as seen in applications achieving 50 percent power increases without intercooling, though they demand robust engine internals to withstand detonation risks from elevated charge temperatures.[54] Airflow optimization complements boosting by minimizing restrictions and maximizing volumetric efficiency, defined as the ratio of actual air mass ingested to the theoretical maximum. In naturally aspirated or boosted four-stroke cycles, intake manifold runner length and diameter are tuned for inertial ram charging via Helmholtz resonance, where optimal lengths (typically 20-40 cm for automotive engines) align pressure waves to augment cylinder filling at target RPMs, potentially boosting volumetric efficiency by 5-10 percent.[55] Variable-length intake manifolds, employing rotary valves or sliders, switch geometries to adapt across engine speeds; for example, systems in production gasoline engines extend runners at low RPM for torque and shorten them at high RPM for power, achieving up to 12 percent gains in torque bandwidth.[56] Valve timing optimization via variable valve timing (VVT) systems, such as cam phasers or multi-profile cams, dynamically adjusts intake valve closing to exploit the Atkinson-like cycle for efficiency or Otto cycle for power, reducing pumping losses by 5-7 percent in boosted setups.[57] Intercoolers, or charge air coolers, are integral to boosted airflow management, densifying compressed air by 10-15 percent per 50°C temperature drop, mitigating knock in gasoline engines and enabling higher boost levels without efficiency penalties from excessive heat. Exhaust manifold design, including log-style versus tubular headers, further aids boosting by equalizing pulse timing, with tuned exhaust systems recovering 2-5 percent of energy for turbo drive while optimizing backpressure to under 1.2 times intake pressure. Overall, integrated boosting and airflow strategies can elevate specific power output to over 100 kW/L in downsized engines, though they introduce challenges like increased thermal stresses requiring materials such as Inconel alloys for durability.[51][52]Structural ratios and durability

The bore-to-stroke ratio in four-stroke engines defines the relative dimensions of the cylinder bore diameter to the piston stroke length, influencing mechanical stresses, friction, and operational limits. Oversquare configurations (bore exceeding stroke) reduce mean piston speed for a given rotational speed, mitigating inertial loads on reciprocating components and enhancing high-RPM durability by lowering peak accelerations.[40] Undersquare designs (stroke exceeding bore), common in torque-oriented applications, elevate mean piston speed—calculated as in meters per second—potentially accelerating wear through increased side thrust and bearing forces, though they favor low-end power.[58] Empirical studies identify an optimal bore-to-stroke ratio near 0.93 for balancing power output, fuel efficiency, and emissions while preserving structural integrity under cyclic combustion pressures.[58] The connecting rod length-to-stroke ratio further modulates durability by governing piston angulation relative to the cylinder wall. Ratios above 1.5 (longer rods) minimize lateral thrust forces during the compression and power strokes, reducing skirt scuffing, cylinder wall abrasion, and lubrication demands, thereby extending service life in high-load scenarios.[59] Lower ratios amplify these side loads due to greater rod angularity, increasing frictional losses and fatigue risks in piston rings and liners, particularly in stroker modifications where stroke extensions without proportional rod lengthening degrade wear resistance.[60] This geometric factor interacts with mean piston speed limits, conventionally capped at 20-25 m/s for automotive durability to avoid excessive inertial stresses on the crankshaft and bearings, with modern forged components permitting up to 30 m/s in racing contexts before reliability declines.[61] Overall engine durability hinges on these ratios' integration with material selection and finite element analysis of the block and head, where thin-wall cast aluminum designs demand precise stress distribution to resist thermal fatigue from peak cylinder pressures exceeding 100 bar.[62] Cyclic loading from combustion induces fatigue in critical junctions like main bearing caps, with ratios optimizing load paths to achieve 200,000-500,000 km lifespans in passenger vehicle applications under standard duty cycles.[63] Advanced simulations confirm that deviations from balanced ratios exacerbate vibration harmonics, accelerating crack propagation in high-mileage operation absent robust damping.[64]Fuel and Combustion

Fuel types and compatibility

Four-stroke engines operate using either spark-ignition or compression-ignition principles, with fuel types tailored to each mechanism. Spark-ignition variants predominantly utilize gasoline, a volatile hydrocarbon mixture refined to specific octane ratings (typically 87-93 AKI for automotive applications) to prevent pre-ignition under compression ratios of 8:1 to 12:1.[65] Diesel fuel, consisting of heavier hydrocarbons with cetane numbers of 40-55, powers compression-ignition four-stroke engines, which achieve ratios of 14:1 to 25:1, relying on auto-ignition from heat rather than sparks.[66] Cross-compatibility is absent; injecting diesel into a gasoline engine fails to ignite without a spark and risks injector clogging, while gasoline in a diesel engine causes incomplete combustion and potential hydraulic lock from low compressibility.[67] Gasoline engines exhibit broad compatibility with ethanol blends up to E10 (10% ethanol by volume), as evidenced by manufacturer certifications for unleaded fuels meeting ASTM D4814 standards, though higher blends like E15 or E85 demand corrosion-resistant materials (e.g., stainless steel fuel lines) and recalibrated fuel systems to mitigate phase separation and vapor lock.[68] [69] Small engines, such as those in lawn mowers or outboards, perform optimally on ethanol-free gasoline to avoid hygroscopic ethanol attracting water, leading to corrosion in carburetors and reduced lubricity.[70] Diesel engines tolerate biodiesel blends up to B20 (20% fatty acid methyl esters) without significant modifications, provided fuels meet ASTM D975 specifications, but higher percentages increase NOx emissions and require upgraded seals to counter solvent effects.[71] Alternative fuels like methanol, natural gas, and hydrogen offer potential for four-stroke engines but necessitate engine redesigns for compatibility. Methanol, with its high octane (108-110) and oxygen content, suits dual-fuel or dedicated spark-ignition setups, enabling lean-burn operation but demanding larger fuel tanks due to lower energy density (20 MJ/kg vs. 44 MJ/kg for gasoline) and anti-corrosion additives.[72] [73] Compressed natural gas (CNG) or liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) integrates via port injection in gasoline engines, reducing CO2 by 20-30% but requiring high-pressure storage and timing adjustments for slower flame speeds.[74] Hydrogen combustion in modified four-strokes yields zero carbon emissions but poses challenges from high flame speeds causing backfiring and the need for reinforced pistons against pre-ignition.[74] Biofuels and synthetic e-fuels expand options, yet empirical tests confirm that unmodified engines risk durability loss from altered viscosity and lubricity, underscoring the primacy of petroleum-derived fuels for standard applications.[75]Ignition and combustion processes

In spark-ignition four-stroke engines operating on the Otto cycle, ignition occurs near the end of the compression stroke when the spark plug delivers a high-voltage electrical discharge across its electrodes, creating a plasma kernel that initiates combustion of the premixed air-fuel charge.[2] This spark is timed to fire typically 10 to 40 degrees of crankshaft rotation before top dead center (BTDC), allowing the combustion process to begin while the piston is still rising, thereby maximizing pressure development during the subsequent power stroke.[76] Advancing the ignition timing increases peak cylinder pressure and torque output by aligning heat release more closely with the expansion stroke, though excessive advance risks engine knock due to auto-ignition of end gases.[76] Combustion proceeds as the initial flame kernel expands rapidly, transitioning from laminar to turbulent propagation influenced by in-cylinder flow structures such as swirl and tumble, with flame speeds reaching 20 to 50 meters per second under typical operating conditions.[77] The process approximates constant-volume heat addition in the ideal Otto cycle, where chemical energy release elevates combustion temperatures to approximately 2,000–2,500 K and pressures to 50–100 bar, driving the piston downward and converting thermal energy into mechanical work.[11] Incomplete combustion or misfires can occur if the air-fuel ratio deviates significantly from stoichiometric (around 14.7:1 for gasoline), with lean mixtures slowing flame propagation and rich mixtures quenching the flame front.[2] Turbulence generated by intake flow and piston motion enhances mixing and flame area, accelerating burn rates and reducing combustion duration to 1–2 milliseconds at wide-open throttle, but excessive turbulence can entrain unburned hydrocarbons into crevices, contributing to cycle-to-cycle variability in burn efficiency.[78] Ignition timing optimization, often via electronic control units adjusting for load, speed, and temperature, balances power, efficiency, and emissions; for instance, retarding timing by 5–10 degrees reduces peak temperatures and NOx formation while potentially increasing hydrocarbon emissions from slower, cooler burns.[76] In diesel four-stroke variants, ignition relies on compression-induced auto-ignition rather than spark, with fuel injected directly into high-temperature air (above 700 K at 15–20:1 compression ratios), leading to stratified diffusion flames rather than premixed propagation.[11]Emissions formation and mitigation

In four-stroke spark-ignition engines, the primary exhaust emissions consist of unburned hydrocarbons (HC), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulate matter (PM), with carbon dioxide (CO2) as a combustion byproduct.[79] [80] These form mainly during the power stroke, where incomplete combustion or high-temperature reactions in the cylinder deviate from ideal fuel oxidation. HC arises from flame quenching at cold cylinder walls, crevice entrapment of fuel-air mixture, and incomplete vaporization of fuel droplets, leading to unburned fuel exiting via the exhaust stroke.[81] [82] CO results from oxygen-deficient local zones in the combustion chamber, where fuel partially oxidizes to CO rather than fully to CO2 due to insufficient mixing or short residence times at high temperatures.[81] [82] NOx formation predominantly occurs via the thermal Zeldovich mechanism, where atmospheric nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2) react at peak combustion temperatures exceeding 1800 K (about 1500°C), producing nitric oxide (NO) that partially converts to NO2 post-combustion; supplemental pathways include prompt NOx from hydrocarbon radicals and fuel-bound nitrogen, though the latter is minimal in typical gasoline.[83] [84] PM, primarily in direct-injection variants, stems from rich fuel zones forming soot precursors during diffusion flames, though levels remain lower than in diesel engines due to premixed combustion dominance.[85] [80] Mitigation strategies integrate in-cylinder controls and aftertreatment. Precise air-fuel ratio (AFR) management near stoichiometry (14.7:1 for gasoline) via electronic fuel injection minimizes HC and CO by ensuring sufficient oxygen for oxidation while avoiding excess air that quenches flames.[81] Exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) dilutes intake charge with 5-15% recirculated exhaust, lowering peak combustion temperatures by 200-300 K to suppress NOx via reduced O2 availability and specific heat increase, though it can elevate HC and CO if unoptimized.[86] Three-way catalytic converters, standard since the 1970s, achieve over 90% simultaneous reduction of CO (to CO2), HC (to CO2 and H2O), and NOx (to N2) under closed-loop AFR control using oxygen sensors; they employ platinum, palladium, and rhodium on ceramic monoliths to facilitate redox reactions at 400-800°C.[81] [87] Advanced variants include close-coupled positioning for faster light-off and particulate filters for direct-injection engines to trap PM, oxidizing it via cerium additives.[80] Lean-burn configurations with NOx adsorbers or selective catalytic reduction (SCR) further enable efficiency gains but require urea injection for NOx hydrolysis in diesel-like applications.[88]Applications and Performance

Automotive and transportation uses

The four-stroke engine has been the predominant powerplant in passenger automobiles since Karl Benz fitted a single-cylinder four-stroke gasoline engine to his Patent-Motorwagen in 1886, marking the first practical automobile.[4] This design, based on Nikolaus Otto's 1876 cycle, enabled reliable operation with compression ratios yielding thermal efficiencies up to 30% in modern variants.[89] By the early 20th century, multi-cylinder four-stroke engines powered mass-produced vehicles like the Ford Model T starting in 1908, establishing the internal combustion engine as the standard for personal transportation due to its balance of power density and fuel economy.[2] Today, nearly all gasoline-powered passenger cars employ four-stroke Otto-cycle engines, with market projections indicating internal combustion propulsion, predominantly four-stroke, retaining about 41.8% revenue share in passenger vehicles as of 2025 amid electrification trends.[90] In commercial transportation, four-stroke diesel engines dominate heavy-duty trucks and buses for their superior torque and efficiency from higher compression ratios, typically 14:1 to 22:1.[91] These engines, operating on the four-stroke Diesel cycle invented by Rudolf Diesel in 1892, power the majority of global freight and public transit fleets, with virtually 100% of European diesel trucks using four-stroke configurations featuring turbocharging and direct injection.[92] Diesel four-strokes achieve better fuel economy than gasoline counterparts, contributing to their prevalence in applications requiring long-haul durability, though they produce higher nitrogen oxide emissions necessitating aftertreatment systems.[93] In the United States, medium- and heavy-duty trucks rely on four-stroke diesels from manufacturers like Cummins and Detroit Diesel, supporting logistics that move over 70% of freight by ton-miles.[94] Four-stroke engines have increasingly supplanted two-strokes in motorcycles, particularly since the 1990s, driven by stricter emissions regulations and demands for smoother power delivery. Yamaha's YZ400F in 1998 pioneered competitive four-stroke motocross bikes, leading to widespread adoption where four-strokes now constitute the standard for off-road and street models due to reduced oil consumption and lower unburnt hydrocarbon emissions.[95] Modern four-stroke motorcycle engines, often liquid-cooled and multi-valve, offer power outputs from 50 to over 200 horsepower in sport variants, with global motorcycle market growth projected at 4.1% to 6.1% CAGR through 2034, largely featuring four-stroke designs.[96] This shift reflects the four-stroke's inherent efficiency advantage, consuming fuel only every other crankshaft revolution compared to two-strokes, resulting in up to 50% better fuel economy in equivalent displacements.[97]Industrial and marine implementations

Four-stroke engines are extensively employed in industrial settings for stationary power generation, where natural gas variants predominate and achieve capacities up to 18 MW per unit, supporting combined heat and power systems with high reliability for continuous operation.[98] Diesel models from manufacturers like Caterpillar provide ratings from 429 to 597 kW (575 to 800 hp) at 1800–2000 rpm, powering applications in oil and gas extraction, pipeline transport, and emergency backup generators, valued for their durability under variable loads.[99][100] These engines often feature inline or V configurations, with displacements ranging from 4.4 L in compact units like the Caterpillar C4.4 (up to 150 kW) to larger 18 L blocks for heavy-duty tasks in construction and agriculture.[101] In marine environments, four-stroke engines serve primarily as medium-speed propulsion and auxiliary power sources, offering power outputs from 221 kW to over 10 MW, suitable for ferries, supply vessels, and offshore support ships where quieter operation and lower emissions relative to two-strokes are advantageous.[102][103] The Wärtsilä 31, recognized for peak thermal efficiency exceeding 50% in its class, delivers 4.6–10.4 MW across 8- to 16-cylinder configurations at 720–750 rpm, enabling fuel flexibility including diesel and dual-fuel options for reduced lifecycle costs.[104] Similarly, MAN's L27/38 series provides 2.1–3.69 MW for propulsion, emphasizing long overhaul intervals and adaptability to heavy fuels.[105] Overall marine four-stroke power spans 2 kW to 25 MW, with inline-6 to V-20 cylinder layouts optimized for vibration control and compliance with emission standards like IMO Tier III.[106]Power output and efficiency metrics

Brake mean effective pressure (BMEP) serves as a key metric for assessing power output in four-stroke engines, representing the average effective pressure on the piston that yields the measured brake power for a given displacement. For naturally aspirated four-stroke engines, BMEP typically ranges from 8 to 12 bar, while turbocharged gasoline variants achieve 15 to 25 bar or higher in optimized designs, enabling specific power outputs exceeding 100 horsepower per liter in modern automotive applications. Diesel four-stroke engines exhibit comparable or slightly higher BMEP values, often 15 to 25 bar under boost, reflecting their capacity for sustained high-pressure combustion.[107][108] Brake thermal efficiency (BTE), the ratio of brake work output to fuel energy input, quantifies fuel conversion effectiveness in four-stroke cycles. Gasoline four-stroke engines achieve BTE of 25% to 40%, with downsized turbocharged models reaching 35% to 40% through elevated compression ratios (up to 12:1 or more), direct injection, and variable valve timing that minimize pumping losses and enable lean-burn operation. Diesel counterparts attain 35% to 45% BTE, benefiting from compression ratios of 16:1 to 20:1 and inherently higher expansion ratios that extract more work from combustion heat. Advanced prototypes, incorporating technologies like Atkinson cycle modifications or exhaust heat recovery, have demonstrated BTE exceeding 45% in both fuel types under controlled conditions.[109][110][111] Brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC), expressed in grams of fuel per kilowatt-hour, inversely correlates with efficiency and highlights operational economy. Four-stroke spark-ignition engines yield BSFC around 250 g/kWh at peak torque, whereas compression-ignition variants achieve approximately 200 g/kWh, underscoring diesel's superior part-load performance due to lower heat rejection and reduced throttling. These metrics improve with load, as BSFC minima occur near maximum torque where volumetric efficiency and combustion completeness peak.[112]| Metric | Gasoline Four-Stroke (Typical) | Diesel Four-Stroke (Typical) |

|---|---|---|

| Brake Thermal Efficiency (%) | 25–40 | 35–45 |

| BSFC (g/kWh) | ~250 | ~200 |

| BMEP (bar, turbocharged) | 15–25 | 15–25 |