Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geothermal power

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

Geothermal power is electrical power generated from geothermal energy. Technologies in use include dry steam power stations, flash steam power stations and binary cycle power stations. Geothermal electricity generation is currently used in 26 countries,[1][2] while geothermal heating is in use in 70 countries.[3]

As of 2019, worldwide geothermal power capacity amounts to 15.4 gigawatts (GW), of which 23.9% (3.68 GW) are installed in the United States.[4] International markets grew at an average annual rate of 5 percent over the three years to 2015, and global geothermal power capacity is expected to reach 14.5–17.6 GW by 2020.[5] Based on current geologic knowledge and technology the Geothermal Energy Association (GEA) publicly discloses, the GEA estimates that only 6.9% of total global potential has been tapped so far, while the IPCC reported geothermal power potential to be in the range of 35 GW to 2 TW.[3] Countries generating more than 15 percent of their electricity from geothermal sources include El Salvador, Kenya, the Philippines, Iceland, New Zealand,[6] and Costa Rica. Indonesia has an estimated potential of 29 GW of geothermal energy resources, the largest in the world; in 2017, its installed capacity was 1.8 GW.

Geothermal power is considered to be a sustainable, renewable source of energy because the heat extraction is small compared with the Earth's heat content.[7] The greenhouse gas emissions of geothermal electric stations average 45 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt-hour of electricity, or less than 5% of those of conventional coal-fired plants.[8]

As a source of renewable energy for both power and heating, geothermal has the potential to meet 3 to 5% of global demand by 2050. With economic incentives, it is estimated that by 2100 it will be possible to meet 10% of global demand with geothermal power.[6]

History and development

[edit]In the 20th century, demand for electricity led to the consideration of geothermal power as a generating source. Prince Piero Ginori Conti tested the first geothermal power generator on 4 July 1904 in Larderello, Italy. It successfully lit four light bulbs.[9] Later, in 1911, the world's first commercial geothermal power station was built there. Experimental generators were built in Beppu, Japan and the Geysers, California, in the 1920s, but Italy was the world's only industrial producer of geothermal electricity until 1958.

In 1958, New Zealand became the second major industrial producer of geothermal electricity when its Wairakei station was commissioned. Wairakei was the first station to use flash steam technology.[11] Over the past 60 years, net fluid production has been in excess of 2.5 km3. Subsidence at Wairakei-Tauhara has been an issue in a number of formal hearings related to environmental consents for expanded development of the system as a source of renewable energy.[6]

In 1960, Pacific Gas and Electric began operation of the first successful geothermal electric power station in the United States at The Geysers in California.[12] The original turbine lasted for more than 30 years and produced 11 MW net power.[13]

An organic fluid based binary cycle power station was first demonstrated in 1967 in the Soviet Union[12] and later introduced to the United States in 1981[citation needed], following the 1970s energy crisis and significant changes in regulatory policies. This technology allows the use of temperature resources as low as 81 °C (178 °F). In 2006, a binary cycle station in Chena Hot Springs, Alaska, came on-line, producing electricity from a record low fluid temperature of 57 °C (135 °F).[14]

Geothermal electric stations have until recently been built exclusively where high-temperature geothermal resources are available near the surface. The development of binary cycle power plants and improvements in drilling and extraction technology may enable enhanced geothermal systems over a much greater geographical range.[15] Demonstration projects are operational in Landau-Pfalz, Germany, and Soultz-sous-Forêts, France, while an earlier effort in Basel, Switzerland was shut down after it triggered earthquakes. Other demonstration projects are under construction in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America.[16]

The thermal efficiency of geothermal electric stations is low, around 7 to 10%,[17] because geothermal fluids are at a low temperature compared with steam from boilers. By the laws of thermodynamics this low temperature limits the efficiency of heat engines in extracting useful energy during the generation of electricity. Exhaust heat is wasted, unless it can be used directly and locally, for example in greenhouses, timber mills, and district heating. The efficiency of the system does not affect operational costs as it would for a coal or other fossil fuel plant, but it does factor into the viability of the station. In order to produce more energy than the pumps consume, electricity generation requires high-temperature geothermal fields and specialized heat cycles.[citation needed] Because geothermal power does not rely on variable sources of energy, unlike, for example, wind or solar, its capacity factor can be quite large – up to 96% has been demonstrated.[18] However the global average capacity factor was 74.5% in 2008, according to the IPCC.[19]

Resources

[edit]

The Earth's heat content is about 1×1019 TJ (2.8×1015 TWh).[3] This heat naturally flows to the surface by conduction at a rate of 44.2 TW[20] and is replenished by radioactive decay at a rate of 30 TW.[7] These power rates are more than double humanity's current energy consumption from primary sources, but most of this power is too diffuse (approximately 0.1 W/m2 on average) to be recoverable. The Earth's crust effectively acts as a thick insulating blanket which must be pierced by fluid conduits (of magma, water or other) to release the heat underneath.

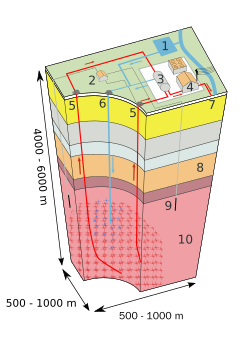

Electricity generation requires high-temperature resources that can only come from deep underground. The heat must be carried to the surface by fluid circulation, either through magma conduits, hot springs, hydrothermal circulation, oil wells, drilled water wells, or a combination of these. This circulation sometimes exists naturally where the crust is thin: magma conduits bring heat close to the surface, and hot springs bring the heat to the surface. If a hot spring is not available, a well must be drilled into a hot aquifer. Away from tectonic plate boundaries the geothermal gradient is 25 to 30 °C per kilometre (70 to 85 °F per mile) of depth in most of the world, so wells would have to be several kilometres deep to permit electricity generation.[3] The quantity and quality of recoverable resources improves with drilling depth and proximity to tectonic plate boundaries.

In ground that is hot but dry, or where water pressure is inadequate, injected fluid can stimulate production. Developers bore two holes into a candidate site, and fracture the rock between them with explosives or high-pressure water. Then they pump water or liquefied carbon dioxide down one borehole, and it comes up the other borehole as a gas.[15] This approach is called hot dry rock geothermal energy in Europe, or enhanced geothermal systems in North America. Much greater potential may be available from this approach than from conventional tapping of natural aquifers.[15]

Estimates of the electricity generating potential of geothermal energy vary from 35 to 2000 GW depending on the scale of investments.[3] This does not include non-electric heat recovered by co-generation, geothermal heat pumps and other direct use. A 2006 report by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that included the potential of enhanced geothermal systems estimated that investing US$1 billion in research and development over 15 years would allow the creation of 100 GW of electrical generating capacity by 2050 in the United States alone.[15] The MIT report estimated that over 200×109 TJ (200 ZJ; 5.6×107 TWh) would be extractable, with the potential to increase this to over 2,000 ZJ with technology improvements – sufficient to provide all the world's present energy needs for several millennia.[15]

At present, geothermal wells are rarely more than 3 km (2 mi) deep.[3] Upper estimates of geothermal resources assume wells as deep as 10 km (6 mi). Drilling near this depth is now possible in the petroleum industry, although it is an expensive process. The deepest research well in the world, the Kola Superdeep Borehole (KSDB-3), is 12.261 km (7.619 mi) deep.[21] Wells drilled to depths greater than 4 km (2.5 mi) generally incur drilling costs in the tens of millions of dollars.[22] The technological challenges are to drill wide bores at low cost and to break larger volumes of rock.

Geothermal power is considered to be sustainable because the heat extraction is small compared to the Earth's heat content, but extraction must still be monitored to avoid local depletion.[7] Although geothermal sites are capable of providing heat for many decades, individual wells may cool down or run out of water. The three oldest sites, at Larderello, Wairakei, and the Geysers have all reduced production from their peaks. It is not clear whether these stations extracted energy faster than it was replenished from greater depths, or whether the aquifers supplying them are being depleted. If production is reduced, and water is reinjected, these wells could theoretically recover their full potential. Such mitigation strategies have already been implemented at some sites. The long-term sustainability of geothermal energy has been demonstrated at the Larderello field in Italy since 1913, at the Wairakei field in New Zealand since 1958,[23] and at the Geysers field in California since 1960.[24]

Power station types

[edit]Geothermal power stations are similar to other steam turbine thermal power stations in that heat from a fuel source (in geothermal's case, the Earth's core) is used to heat water or another working fluid. The working fluid is then used to turn a turbine of a generator, thereby producing electricity. The fluid is then cooled and returned to the heat source.

Dry steam power stations

[edit]Dry steam stations are the simplest and oldest design. There are few power stations of this type, because they require a resource that produces dry steam, but they are the most efficient, with the simplest facilities.[25] At these sites, there may be liquid water present in the reservoir, but only steam, not water, is produced to the surface.[25] Dry steam power directly uses geothermal steam of 150 °C (300 °F) or greater to turn turbines.[3] As the turbine rotates it powers a generator that produces electricity and adds to the power field.[26] Then, the steam is emitted to a condenser, where it turns back into a liquid, which then cools the water.[27] After the water is cooled it flows down a pipe that conducts the condensate back into deep wells, where it can be reheated and produced again. At The Geysers in California, after the first 30 years of power production, the steam supply had depleted and generation was substantially reduced. To restore some of the former capacity, supplemental water injection was developed during the 1990s and 2000s, including utilization of effluent from nearby municipal sewage treatment facilities.[28]

Flash steam power stations

[edit]Flash steam stations pull deep, high-pressure hot water into lower-pressure tanks and use the resulting flashed steam to drive turbines. They require fluid temperatures of at least 180 °C (360 °F), usually more. As of 2022, flash steam stations account for 36.7% of all geothermal power plants and 52.7% of the installed capacity in the world.[29] Flash steam plants use geothermal reservoirs of water with temperatures greater than 180 °C. The hot water flows up through wells in the ground under its own pressure. As it flows upward, the pressure decreases and some of the hot water is transformed into steam. The steam is then separated from the water and used to power a turbine/generator. Any leftover water and condensed steam may be injected back into the reservoir, making this a potentially sustainable resource.[30] [31]

Binary cycle power stations

[edit]Binary cycle power stations are the most recent development, and can accept fluid temperatures as low as 57 °C (135 °F).[14] The moderately hot geothermal water is passed by a secondary fluid with a much lower boiling point than water. This causes the secondary fluid to flash vaporize, which then drives the turbines. This is the most common type of geothermal electricity station being constructed today.[32] Both Organic Rankine and Kalina cycles are used. The thermal efficiency of this type of station is typically about 10–13%.[33] Binary cycle power plants have an average unit capacity of 6.3 MW, 30.4 MW at single-flash power plants, 37.4 MW at double-flash plants, and 45.4 MW at power plants working on superheated steam.[34]

Worldwide production

[edit]

The International Renewable Energy Agency has reported that 14,438 MW of geothermal power was online worldwide at the end of 2020, generating 94,949 GWh of electricity.[35] In theory, the world's geothermal resources are sufficient to supply humans with energy. However, only a tiny fraction of the world's geothermal resources can at present be explored on a profitable basis.[36]

Al Gore said in The Climate Project Asia Pacific Summit that Indonesia could become a super power country in electricity production from geothermal energy.[37] In 2013 the publicly owned electricity sector in India announced a plan to develop the country's first geothermal power facility in the landlocked state of Chhattisgarh.[38]

Geothermal power in Canada has high potential due to its position on the Pacific Ring of Fire. The region of greatest potential is the Canadian Cordillera, stretching from British Columbia to the Yukon, where estimates of generating output have ranged from 1,550 MW to 5,000 MW.[39]

The geography of Japan is advantageous for geothermal power production. Japan has numerous hot springs that could provide fuel for geothermal power plants, but a massive investment in Japan's infrastructure would be necessary.[40]

Utility-grade stations

[edit]

The largest group of geothermal power plants in the world is located at The Geysers, a geothermal field in California, United States.[42] As of 2021, five countries (Kenya, Iceland, El Salvador, New Zealand, and Nicaragua) generate more than 15% of their electricity from geothermal sources.[41]

The following table lists these data for each country:

- total generation from geothermal in terawatt-hours,

- percent of that country's generation that was geothermal,

- total geothermal capacity in gigawatts,

- percent growth in geothermal capacity, and

- the geothermal capacity factor for that year.

Data are for the year 2021. Data are sourced from the EIA.[41] Only includes countries with more than 0.01 TWh of generation. Links for each location go to the relevant geothermal power page, when available.

| Country | Gen (TWh) |

% gen. |

Cap. (GW) |

% cap. growth |

Cap. fac. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | 91.80 | 0.3% | 14.67 | 1.7 | 71% |

| 16.24 | 0.4% | 2.60 | 1.0 | 71% | |

| 15.90 | 5.2% | 2.28 | 6.9 | 80% | |

| 10.89 | 10.1% | 1.93 | 0 | 64% | |

| 10.77 | 3.4% | 1.68 | 3.9 | 73% | |

| 7.82 | 18.0% | 1.27 | 0 | 70% | |

| 5.68 | 29.4% | 0.76 | 0 | 86% | |

| 5.53 | 2.0% | 0.77 | 0 | 82% | |

| 5.12 | 43.4% | 0.86 | 0 | 68% | |

| 4.28 | 1.3% | 1.03 | 0 | 47% | |

| 3.02 | 0.3% | 0.48 | 0 | 72% | |

| 1.60 | 12.6% | 0.26 | 0 | 70% | |

| 1.58 | 23.9% | 0.20 | 0 | 88% | |

| 0.78 | 16.9% | 0.15 | 0 | 58% | |

| 0.45 | 0.04% | 0.07 | 0 | 69% | |

| 0.40 | 8.2% | 0.06 | 0 | 82% | |

| 0.33 | 0.4% | 0.04 | 0 | 94% | |

| 0.32 | 2.2% | 0.05 | 0 | 73% | |

| 0.31 | 2.6% | 0.04 | 0 | 91% | |

| 0.25 | 0.04% | 0.05 | 15.0 | 62% | |

| 0.18 | 0.4% | 0.03 | 0 | 70% | |

| 0.13 | 0.03% | 0.02 | 0 | 95% | |

| 0.13 | 0.002% | 0.03 | 0 | 55% | |

| 0.07 | 0.5% | 0.01 | 0 | 85% |

Environmental impact

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

Existing geothermal electric stations that fall within the 50th percentile of all total life cycle emissions studies reviewed by the IPCC produce on average 45 kg of CO

2 equivalent emissions per megawatt-hour of generated electricity (kg CO

2eq/MWh).[43] For comparison, a coal-fired power plant emits 1,001 kg of CO

2 equivalent per megawatt-hour when not coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS).[8][43] As many geothermal projects are situated in volcanically active areas that naturally emit greenhouse gases, it is hypothesized that geothermal plants may actually decrease the rate of de-gassing by reducing the pressure on underground reservoirs.[44]

Stations that experience high levels of acids and volatile chemicals are usually equipped with emission-control systems to reduce the exhaust. Geothermal stations can also inject these gases back into the earth as a form of carbon capture and storage, such as in New Zealand[44] and in the CarbFix project in Iceland.

Other stations, like the Kızıldere geothermal power plant, exhibit the capability to use geothermal fluids to process carbon dioxide gas into dry ice at two nearby plants, resulting in very little environmental impact.[45]

In addition to dissolved gases, hot water from geothermal sources may hold in solution trace amounts of toxic chemicals, such as mercury, arsenic, boron, antimony, and salt.[46] These chemicals come out of solution as the water cools, and can cause environmental damage if released. The modern practice of injecting geothermal fluids back into the Earth to stimulate production has the side benefit of reducing this environmental risk.

Station construction can adversely affect land stability. Subsidence has occurred in the Wairakei field in New Zealand.[47] Enhanced geothermal systems can trigger earthquakes due to water injection. The project in Basel, Switzerland was suspended because more than 10,000 seismic events measuring up to 3.4 on the Richter Scale occurred over the first 6 days of water injection.[48] The risk of geothermal drilling leading to uplift has been experienced in Staufen im Breisgau.

Geothermal has minimal land and freshwater requirements. Geothermal stations use 404 square meters per GWh versus 3,632 and 1,335 square meters for coal facilities and wind farms respectively.[47] They use 20 litres of freshwater per MWh versus over 1000 litres per MWh for nuclear, coal, or oil.[47]

Local climate cooling is possible as a result of the work of the geothermal circulation systems. However, according to an estimation given by Leningrad Mining Institute in 1980s, possible cool-down will be negligible compared to natural climate fluctuations.[49]

While volcanic activity produces geothermal energy, it is also risky. As of 2022[update] the Puna Geothermal Venture has still not returned to full capacity after the 2018 lower Puna eruption.[50]

Economics

[edit]Geothermal power requires no fuel; it is therefore immune to fuel cost fluctuations. However, capital costs tend to be high. Drilling accounts for over half the costs, and exploration of deep resources entails significant risks. A typical well doublet in Nevada can support 4.5 MW of electricity generation and costs about $10 million to drill, with a 20% failure rate.[22] In total, electrical station construction and well drilling costs about 2–5 million € per MW of electrical capacity, while the levelised energy cost is 0.04–0.10 € per kWh.[10] Enhanced geothermal systems tend to be on the high side of these ranges, with capital costs above $4 million per MW and levelized costs above $0.054 per kWh in 2007.[51]

Research suggests in-reservoir storage could increase the economic viability of enhanced geothermal systems in energy systems with a large share of variable renewable energy sources.[52][53]

Geothermal power is highly scalable: a small power station can supply a rural village, though initial capital costs can be high.[54]

The most developed geothermal field is the Geysers in California. In 2008, this field supported 15 stations, all owned by Calpine, with a total generating capacity of 725 MW.[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Geothermal Energy Association. Geothermal Energy: International Market Update Archived 25 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine May 2010, p. 4-6.

- ^ Bassam, Nasir El; Maegaard, Preben; Schlichting, Marcia (2013). Distributed Renewable Energies for Off-Grid Communities: Strategies and Technologies Toward Achieving Sustainability in Energy Generation and Supply. Newnes. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-12-397178-4. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fridleifsson, Ingvar B.; Bertani, Ruggero; Huenges, Ernst; Lund, John W.; Ragnarsson, Arni; Rybach, Ladislaus (11 February 2008). O. Hohmeyer and T. Trittin (ed.). The possible role and contribution of geothermal energy to the mitigation of climate change (PDF). IPCC Scoping Meeting on Renewable Energy Sources. Luebeck, Germany. pp. 59–80. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Richter, Alexander (27 January 2020). "The Top 10 Geothermal Countries 2019 – based on installed generation capacity (MWe)". Think GeoEnergy - Geothermal Energy News. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "The International Geothermal Market At a Glance – May 2015" (PDF). GEA—Geothermal Energy Association. May 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Craig, William; Gavin, Kenneth (2018). Geothermal Energy, Heat Exchange Systems and Energy Piles. London: ICE Publishing. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-7277-6398-3. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Rybach, Ladislaus (September 2007), "Geothermal Sustainability" (PDF), Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin, vol. 28, no. 3, Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology, pp. 2–7, ISSN 0276-1084, archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2012, retrieved 9 May 2009

- ^ a b Moomaw, W., P. Burgherr, G. Heath, M. Lenzen, J. Nyboer, A. Verbruggen, 2011: Annex II: Methodology. In IPCC: Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation (ref. page 10) Archived 27 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tiwari, G. N.; Ghosal, M. K. Renewable Energy Resources: Basic Principles and Applications. Alpha Science Int'l Ltd., 2005 ISBN 1-84265-125-0

- ^ a b Bertani, Ruggero (September 2007), "World Geothermal Generation in 2007" (PDF), Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin, vol. 28, no. 3, Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology, pp. 8–19, ISSN 0276-1084, archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2012, retrieved 12 April 2009

- ^ "IPENZ Engineering Heritage". IPENZ Engineering Heritage. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ a b Lund, J. (September 2004), "100 Years of Geothermal Power Production" (PDF), Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin, vol. 25, no. 3, Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology, pp. 11–19, ISSN 0276-1084, archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2010, retrieved 13 April 2009

- ^ McLarty, Lynn; Reed, Marshall J. (October 1992), "The U.S. Geothermal Industry: Three Decades of Growth" (PDF), Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, 14 (4), London: Taylor & Francis: 443–455, Bibcode:1992EneSA..14..443M, doi:10.1080/00908319208908739, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2016, retrieved 29 July 2013

- ^ a b Erkan, K.; Holdmann, G.; Benoit, W.; Blackwell, D. (2008), "Understanding the Chena Hot Springs, Alaska, geothermal system using temperature and pressure data", Geothermics, 37 (6): 565–585, doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2008.09.001, ISSN 0375-6505

- ^ a b c d e Tester, Jefferson W.; et al., The Future of Geothermal Energy (PDF), Impact, vol. of Enhanced Geothermal Systems (Egs) on the United States in the 21st Century: An Assessment, Idaho Falls: Idaho National Laboratory, ISBN 0-615-13438-6, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2011, retrieved 7 February 2007

- ^ Bertani, Ruggero (2009). "Geothermal Energy: An Overview on Resources and Potential" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Conference on National Development of Geothermal Energy Use. Slovakia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ Schavemaker, Pieter; van der Sluis, Lou (2008). Electrical Power Systems Essentials. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 978-0470-51027-8.

- ^ Lund, John W. (2003), "The USA Geothermal Country Update", Geothermics, European Geothermal Conference 2003, 32 (4–6), Elsevier Science Ltd.: 409–418, Bibcode:2003Geoth..32..409L, doi:10.1016/S0375-6505(03)00053-1

- ^ Goldstein, B., G. Hiriart, R. Bertani, C. Bromley, L. Gutiérrez-Negrín, E. Huenges, H. Muraoka, A. Ragnarsson, J. Tester, V. Zui (2011) "Geothermal Energy" Archived 5 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. In IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA Geothermal Energy. p. 404.

- ^ Pollack, H.N.; S. J. Hurter, and J. R. Johnson; Johnson, Jeffrey R. (1993), "Heat Flow from the Earth's Interior: Analysis of the Global Data Set", Rev. Geophys., vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 267–280, Bibcode:1993RvGeo..31..267P, doi:10.1029/93RG01249, archived from the original on 3 March 2012, retrieved 1 November 2009

- ^ "Kola". www.icdp-online.org. ICDP. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ a b Geothermal Economics 101, Economics of a 35 MW Binary Cycle Geothermal Plant (PDF), New York: Glacier Partners, October 2009, archived from the original on 21 May 2013, retrieved 17 October 2009

- ^ Thain, Ian A. (September 1998), "A Brief History of the Wairakei Geothermal Power Project" (PDF), Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin, vol. 19, no. 3, Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology, pp. 1–4, ISSN 0276-1084, archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2011, retrieved 2 June 2009

- ^ Axelsson, Gudni; Stefánsson, Valgardur; Björnsson, Grímur; Liu, Jiurong (April 2005), "Sustainable Management of Geothermal Resources and Utilization for 100 – 300 Years" (PDF), Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2005, International Geothermal Association, retrieved 27 August 2022

- ^ a b Tabak, John (2009). Solar and Geothermal Energy. New York: Facts On File, Inc. pp. 97–183. ISBN 978-0-8160-7086-2.

- ^ "Geothermal Energy". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. 20 November 2012. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Gawell, Karl (June 2014). "Economic Costs and Benefits of Geothermal Power" (PDF). Geothermal Energy Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ The Future of Energy: Earth, Wind and Fire. Scientific American. 8 April 2013. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-1-4668-3386-9. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Gutiérrez-Negrín, L. C. A. (12 May 2024). "Evolution of worldwide geothermal power 2020–2023". Geothermal Energy. 12 (1) 14. Springer Nature. Bibcode:2024GeoE...12...14G. doi:10.1186/s40517-024-00290-w.

- ^ "Hydrothermal Power Systems". US DOE EERE. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ "Geothermal Energy Information and Facts". Environment. 19 October 2009. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ "Geothermal Basics Overview". Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^ DiPippo, Ronald (2016). Geothermal Power Plants (4th ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-08-100879-9.

- ^ Tomarov, G. V.; Shipkov, A. A. (1 April 2017). "Modern geothermal power: Binary cycle geothermal power plants". Thermal Engineering. 64 (4): 243–250. Bibcode:2017ThEng..64..243T. doi:10.1134/S0040601517040097. ISSN 1555-6301. S2CID 255304218.

- ^ "Renewable Energy Statistics 2022". /publications/2022/Jul/Renewable-Energy-Statistics-2022. 18 July 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Fouad Saad (2016). The Shock of Energy Transition. Partridge Publishing Singapore. ISBN 978-1-4828-6495-3.

- ^ antaranews.com (9 January 2011). "Indonesia can be super power on geothermal energy: Al Gore". Antara News. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ "India's 1st geothermal power plant to come up in Chhattisgarh". Economic Times. 17 February 2013. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Morphet, Suzanne (March–April 2012), "Exploring BC's Geothermal Potential", Innovation Magazine (Journal of the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of BC): 22, archived from the original on 27 July 2012, retrieved 5 April 2012

- ^ Carol Hager; Christoph H. Stefes, eds. (2017). Germany's Energy Transition: A Comparative Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan US. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-137-44288-8.

- ^ a b c d Under "Electricity" select "More Electricity data". At the top right, under Generation select 'Total' and 'Geothermal' and under Capacity select 'Geothermal'. Choose the two most recent years. "International". eia.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Kagel, Alyssa; Diana Bates; Karl Gawell. A Guide to Geothermal Energy and the Environment (PDF). Geothermal Energy Association. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ a b Chouhan, Avinash Kumar; Kumar, Rakesh; Mishra, Abhishek Kumar (2024). "Assessment of the geothermal potential zone of India utilizing GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis technique". Renewable Energy. 227. Bibcode:2024REne..22720552C. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.120552.

- ^ a b Wannan, Olivia (13 August 2022). "Geothermal energy is already reliable - soon it might be carbon-neutral, too". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Dipippo, Ronald (2012). Ph.D. Massachusetts; Dartmouth: Elsevier Ltd. pp. 437–438. ISBN 978-0-08-098206-9.

- ^

Bargagli1, R.; Cateni, D.; Nelli, L.; Olmastroni, S.; Zagarese, B. (August 1997), "Environmental Impact of Trace Element Emissions from Geothermal Power Plants", Environmental Contamination Toxicology, 33 (2), New York: 172–181, Bibcode:1997ArECT..33..172B, doi:10.1007/s002449900239, PMID 9294245, S2CID 30238608

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Lund, John W. (June 2007), "Characteristics, Development and utilization of geothermal resources" (PDF), Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin, vol. 28, no. 2, Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology, pp. 1–9, ISSN 0276-1084, archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2010, retrieved 16 April 2009

- ^ Deichmann, N.; Mai, M.; Bethmann, F.; Ernst, J.; Evans, K.; Fäh, D.; Giardini, D.; Häring, M.; Husen, S.; Kästli, P.; Bachmann, C.; Ripperger, J.; Schanz, U.; Wiemer, S. (2007), "Seismicity Induced by Water Injection for Geothermal Reservoir Stimulation 5 km Below the City of Basel, Switzerland", American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting, 53: V53F–08, Bibcode:2007AGUFM.V53F..08D

- ^ Дядькин, Ю. Д. (2001). "Извлечение и использование тепла земли". Горный информационно-аналитический бюллетень (научно-технический журнал). Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Penn, Ivan (31 May 2022). "Stung by High Energy Costs, Hawaii Looks to the Sun". The New York Times. p. B1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Sanyal, Subir K.; Morrow, James W.; Butler, Steven J.; Robertson-Tait, Ann (22 January 2007). "Cost of Electricity from Enhanced Geothermal Systems" (PDF). Proc. Thirty-Second Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering. Stanford, California. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ Brahambhatt, Rupendra (9 September 2022). "In a world first, scientists propose geothermal power plants that also work as valuable clean energy reservoirs". interestingengineering.com. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Ricks, Wilson; Norbeck, Jack; Jenkins, Jesse (1 May 2022). "The value of in-reservoir energy storage for flexible dispatch of geothermal power". Applied Energy. 313 118807. Bibcode:2022ApEn..31318807R. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.118807. ISSN 0306-2619. S2CID 247302205.

- University press release: Waters, Sharon. "Study shows geothermal could be an ideal energy storage technology". Princeton University via techxplore.com. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Lund, John W.; Boyd, Tonya (June 1999), "Small Geothermal Power Project Examples" (PDF), Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin, vol. 20, no. 2, Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology, pp. 9–26, ISSN 0276-1084, archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2011, retrieved 2 June 2009

- ^ "Calpine Corporation (CPN) (NYSE Arca) Profile" (Press release). Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- DiPippo, Ronald; Gutiérrez-Negrín, Luis C.A.; Chiasson, Andrew (2025). Geothermal Power Generation: Developments and Innovation. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-24750-7.

- Chandrasekharam, Dornadula (2025). Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) for Sustainable Development. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-30116-2.

- Stober, Ingrid; Bucher, Kurt (2021). Geothermal Energy: From Theoretical Models to Exploration and Development. Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-71685-1.

External links

[edit] Data related to Geothermal power at Wikidata

Data related to Geothermal power at Wikidata- Articles on Geothermal Energy Archived 26 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- The Geothermal Collection by the University of Hawaii at Manoa

- GRC Geothermal Library

Geothermal power

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Principles of geothermal energy extraction

Geothermal energy extraction relies on accessing the Earth's internal heat, which originates primarily from the decay of radioactive isotopes such as uranium, thorium, and potassium in the crust and mantle, supplemented by residual heat from the planet's formation approximately 4.5 billion years ago.[3] This heat conducts outward, establishing a geothermal gradient where subsurface temperatures typically increase by 25–30 °C per kilometer of depth in continental crust.[13] Extraction targets regions with elevated heat flow, such as tectonic plate boundaries or hotspots, where natural convection in fluid-filled reservoirs concentrates thermal energy at shallower depths, often exceeding 150 °C at 1–3 km.[3] The core principle involves drilling production wells into permeable subsurface formations containing hot fluids or capable of being fractured to permit fluid circulation.[14] In these reservoirs, water or brine, heated by surrounding rock, is pumped to the surface through wells, leveraging hydrostatic pressure and pumps where necessary to overcome frictional losses and maintain flow rates.[13] The extracted fluid transfers heat via convection—far more efficient than conduction alone—allowing rapid delivery of thermal energy to the surface for power generation.[3] Sustainable extraction requires balancing production with reinjection of cooled fluids into injection wells to replenish reservoir pressure, minimize subsidence, and sustain permeability by preventing mineral scaling or thermal contraction.[2] Heat extraction efficiency depends on reservoir characteristics, including porosity, permeability, and temperature distribution, governed by Darcy's law for fluid flow through porous media: , where is flow rate, permeability, cross-sectional area, fluid viscosity, and pressure gradient.[15] In low-permeability formations, enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) apply hydraulic stimulation to create artificial fractures, enabling water circulation through hot dry rock and mimicking natural hydrothermal convection.[3] Overall, the process converts stored thermal energy into usable form while managing thermodynamic losses, with net efficiency typically ranging from 10–20% due to the low Carnot efficiency of moderate-temperature sources compared to higher-temperature fossil fuels.[14]Types of geothermal heat sources

Geothermal heat sources for power generation primarily consist of subsurface reservoirs where Earth's internal heat is accessible through fluids or engineered means. These sources derive from primordial heat retained during planetary formation, combined with ongoing radiogenic decay in the crust and mantle, creating temperature gradients that enable extraction. Conventional sources rely on natural hydrothermal convection, while advanced types involve human enhancement of permeability.[3] Hydrothermal reservoirs, the most exploited type, feature permeable rock formations saturated with hot water or steam heated by underlying magmatic intrusions or deep circulation. They are subdivided into vapor-dominated and liquid-dominated systems based on fluid phase. Vapor-dominated reservoirs contain superheated steam with minimal liquid water, typically exceeding 200°C, and constitute less than 5% of identified resources due to their rarity, as seen in fields like The Geysers in California, operational since 1960 with initial capacities over 2 GW. These systems require minimal fluid separation but face depletion risks from steam extraction without recharge.[2][16] Liquid-dominated hydrothermal reservoirs, comprising the majority of commercial sites, hold pressurized hot water at 150–370°C in porous aquifers capped by impermeable layers. Fluids here often "flash" to steam upon pressure reduction at the surface, enabling turbine operation; examples include the Salton Sea field in California, where temperatures reach 300°C and salinities exceed seawater. These systems support higher fluid volumes but necessitate reinjection to sustain pressure and minimize subsidence, with global installed capacity from such sources exceeding 15 GW as of 2023.[17][3] Geopressured reservoirs occur in deep sedimentary basins, trapping hot brine under abnormal hydrostatic pressure with dissolved natural gas, potentially yielding both thermal and methane energy. Located at depths of 3–6 km with temperatures around 150–200°C, they offer co-production potential but face challenges from high salinity and gas separation; U.S. Gulf Coast estimates suggest recoverable energy equivalent to thousands of quads, though commercialization remains limited due to corrosion and scaling issues.[18][19] Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) target hot dry rock lacking natural permeability, fracturing impermeable formations at 3–10 km depths (300–500°C) and circulating injected water to extract heat conductively. Pioneered in projects like Fenton Hill, New Mexico, in the 1970s, EGS expands resource potential to 80% of U.S. land area but requires hydraulic stimulation, raising induced seismicity concerns; pilot capacities have reached 5 MW, with DOE targeting 60 GW by 2050 through R&D.[20][2]Historical Development

Pre-20th century uses

Archaeological evidence indicates that indigenous peoples in North America utilized geothermal hot springs for bathing, cooking, and heating as early as 10,000 years ago, with sites like Hot Springs in present-day Arkansas serving as neutral gathering places for warring tribes.[21][22] Ancient Roman civilization extensively harnessed geothermal resources, channeling hot mineral waters from volcanic regions such as those near modern-day Italy and Bath, England, to supply public bathhouses (thermae) and underfloor heating systems starting around the 1st century CE.[23][24] These applications relied on natural hot springs and shallow groundwater heated by geothermal gradients, facilitating both hygienic and therapeutic uses across the empire.[25] In ancient China, geothermal hot springs were employed for similar purposes, including cooking food directly in heated pools and space heating in dwellings, with records dating back over 2,000 years in regions like Yunnan province.[24][25] Native American groups in the Americas continued these practices into historic times, integrating hot springs into daily sustenance and ceremonial activities.[26] The transition to industrial applications occurred in the early 19th century, when in 1827, near Larderello in Tuscany, Italy, natural steam vents and drilled wells were used to evaporate seawater for boric acid production, marking the first documented commercial exploitation of geothermal steam.[27] This method capitalized on the region's fumaroles, yielding significant chemical output without reliance on fossil fuels.[27]Commercialization in the 20th century

The commercialization of geothermal power began in Italy at the Larderello field in Tuscany, where Prince Piero Ginori Conti demonstrated the first geothermal electricity generator on July 4, 1904, successfully powering four light bulbs using steam from natural fumaroles.[28] This experimental setup marked the initial proof-of-concept for harnessing geothermal steam for electrical generation, leveraging the region's dry steam reservoirs for boric acid extraction since the 19th century.[29] By 1913, the world's first commercial geothermal power plant, Larderello 1, entered operation with a capacity of 250 kilowatts, supplying electricity to local industries and expanding to power the Italian railway system.[30] Italy remained the sole producer of geothermal electricity through the mid-20th century, scaling Larderello's output to several megawatts by the 1920s and 1930s despite interruptions from World War II.[31] Commercialization accelerated post-World War II with developments outside Italy. In New Zealand, the Wairakei power station began generating electricity in November 1958, utilizing wet steam resources in the Taupo Volcanic Zone; its initial 12.5-megawatt turbine represented the first large-scale geothermal plant beyond Europe, eventually reaching 157 megawatts by 1963 through phased construction.[32] This facility demonstrated the feasibility of flash-steam technology for two-phase reservoirs, influencing global adoption.[33] In the United States, The Geysers field in California initiated commercial production in 1960 with Pacific Gas & Electric's Unit 1, an 11-megawatt dry-steam plant that became the first geothermal facility in the Americas and a model for utility-scale deployment.[34] By the late 1960s, The Geysers expanded rapidly, adding multiple units and reaching over 500 megawatts, supported by federal incentives and technological refinements in well drilling and steam separation.[35] The 1970s and 1980s saw broader internationalization amid oil crises that highlighted geothermal's baseload reliability. Japan commissioned its first commercial plant at Hatchobaru in 1973, while Iceland's Svartsengi station began operations in 1976, integrating power with district heating.[36] The Philippines entered with the Tiwi field in 1977, followed by Elazig in Turkey in 1984, and Kenya's Olkaria I in 1985, diversifying to binary-cycle adaptations for lower-temperature resources.[31] By 2000, global installed capacity exceeded 8,000 megawatts across 21 countries, with Italy, the United States, and New Zealand accounting for over half, driven by resource assessments confirming economic viability in volcanic regions.[37] These expansions relied on empirical reservoir modeling and drilling advancements, though challenges like steam depletion prompted reinjection practices by the 1980s.[38]21st century advancements and EGS emergence

The 21st century marked a shift in geothermal power toward broader resource accessibility, with binary cycle systems dominating new installations. Since 2000, nearly all geothermal power plants added in the United States have utilized binary cycles, which efficiently convert heat from fluids at 110–200°C into electricity using organic working fluids, expanding viable sites beyond high-temperature hydrothermal reservoirs.[39] Concurrently, Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) emerged as a pivotal innovation to harness hot dry rock formations by engineering permeability through hydraulic stimulation, creating artificial reservoirs for sustained fluid circulation. This approach, evolving from 1970s "hot dry rock" experiments, gained strategic focus via the 2006 MIT-led report The Future of Geothermal Energy, which modeled EGS potential to supply 100 GWe of baseload power in the U.S. by 2050, contingent on overcoming stimulation and circulation challenges.[40] U.S. Department of Energy initiatives accelerated EGS maturation, including the 2015 launch of the Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy (FORGE) in Utah to validate reservoir creation and flow management.[41] By 2023, Fervo Energy's Project Red in Nevada demonstrated commercial viability, achieving the first grid-connected EGS doublet with 3.5 MW of firm output and record flow rates, leveraging horizontal drilling and fiber-optic monitoring for precise fracture control.[42] Subsequent developments included Fervo's 2023 Cape Station project in Utah, aiming for 400 MW by 2028 through phased scaling, and 2024 FORGE tests confirming fracture connectivity in granitic rock at depths over 2 km.[43] [44] A 2025 review of 103 global EGS efforts documented drilling costs below 20% of prior benchmarks, production temperatures averaging 10°C higher per decade, and flow rates exceeding 80 L/s, signaling readiness for widespread adoption amid power purchase agreements surpassing prior capacities by over tenfold.[45]Resource Assessment

Geological reservoir types

Geothermal reservoirs exploited for power generation are chiefly hydrothermal convective systems, where meteoric water circulates through permeable fractures or porous media, heated by underlying magmatic intrusions or conductive heat flow from the mantle, and trapped beneath impermeable caprock. These natural reservoirs require three essential geological elements: a heat source, a fluid (typically groundwater), and sufficient permeability for fluid migration. They form predominantly in tectonically active regions, such as subduction zones or rift systems, where elevated geothermal gradients exceed 30–50°C/km. Reservoirs are classified primarily by the dominant fluid phase—vapor-dominated or liquid-dominated—reflecting thermodynamic conditions where reservoir pressure and temperature determine phase equilibrium, with vapor systems exhibiting fluid specific volumes exceeding water's critical volume (approximately 0.056 m³/kg at 374°C).[46][47] Vapor-dominated reservoirs contain superheated steam as the primary mobile phase, with minimal immobile liquid, typically at temperatures above 235°C (the boiling point at 30–35 bar reservoir pressure) and permeabilities sustained by fracture networks in volcanic or metamorphic rocks. These systems feature a near-static steam column overlying a two-phase zone, producing only steam discharges without surface hot water manifestations, and are geologically linked to high-enthalpy volcanic provinces where low-permeability caps prevent liquid recharge dominance. Representing less than 10% of identified high-enthalpy fields due to their specific formation requirements, they enable direct steam extraction but risk rapid pressure decline from steam cap depletion. Key examples include Larderello in Italy's Tuscan volcanic province and The Geysers in California's Mayacamas Mountains, both hosted in fractured greywacke and volcanic rocks with initial reservoir pressures around 35 bar.[48][49][47] Liquid-dominated reservoirs, far more prevalent and comprising over 90% of operational geothermal fields, hold pressurized hot water as the principal phase, with temperatures ranging from 150°C to over 350°C in permeable aquifers of sedimentary, volcanic, or fractured igneous rocks. Fluid exists as a single-phase liquid under hydrostatic or higher pressures, often with dissolved gases and minerals, and production involves flashing to steam at the surface or binary cycles; geologically, they arise in extensional basins or faulted terrains where recharge sustains liquid volumes, though excessive extraction can induce boiling and phase transition to vapor conditions. These systems exhibit higher storage capacities but require separation of brine to mitigate scaling from mineral precipitation. Prominent instances occur in the Philippines' volcanic arcs (e.g., Tiwi field) and Indonesia's subduction zones, with reservoir permeabilities of 10–100 mD and porosities up to 20% in volcanic tuffs or limestones.[46][47][50] While both types share convective heat transfer mechanisms, their geological distinctions influence extractability: vapor systems offer higher initial enthalpies (2,500–2,800 kJ/kg) but lower sustainability without recharge, whereas liquid systems support larger volumes (10^9–10^12 m³) yet demand reinjection to maintain pressure and avoid subsidence, as evidenced by drawdowns exceeding 10 bar in mature fields. Emerging assessments also consider hybrid or transitional reservoirs with evolving phase dominance due to exploitation-induced boiling.[51][52]Global distribution and exploration methods

Geothermal resources suitable for power generation are concentrated in tectonically active regions where heat flow from Earth's mantle is elevated due to plate boundary processes, including subduction zones, mid-ocean ridges, and continental rifts. Principal areas include the Pacific Ring of Fire, encompassing Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan, and the western United States; the East African Rift system in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Djibouti; and hotspots like Iceland and parts of New Zealand. Additional significant zones occur along transform faults in Turkey and volcanic provinces in Italy and Mexico. These distributions align with global patterns of thinned crust and magmatic activity, enabling accessible reservoirs at depths typically under 5 km.[53][54] As of the end of 2024, worldwide installed geothermal power capacity totaled 15.4 GW, with operations in over 30 countries but dominated by a handful of leaders exploiting hydrothermal systems. The United States maintains the largest capacity at approximately 3,937 MW, concentrated in California's Geysers field and Nevada's enhanced systems. Indonesia ranks second with 2.6 GW, leveraging its position on the Ring of Fire despite regulatory hurdles limiting fuller development of its estimated 29 GW resource base. Other top contributors include the Philippines (around 1.9 GW), Turkey (1.7 GW), New Zealand (1 GW), Iceland (over 800 MW supplying 25% of national electricity), Kenya (861 MW as of recent expansions), Italy, and Mexico. These nations account for over 80% of global output, reflecting both resource endowment and investment in drilling infrastructure.[55][56] Exploration for geothermal reservoirs employs a phased approach integrating surface and subsurface data to minimize drilling risks, which constitute 30-50% of project costs. Initial reconnaissance relies on geologic mapping of fault systems, volcanic features, and hot springs to identify prospects, supplemented by remote sensing via satellite infrared for thermal anomalies. Geophysical methods dominate subsurface delineation: magnetotellurics (MT) surveys detect low-resistivity zones from saline fluids, seismic reflection profiles image faults and permeability structures, and gravity or magnetic surveys highlight intrusive bodies. Geochemical sampling of fumaroles and fluids analyzes isotopes and gases (e.g., helium-3 for mantle input) to infer reservoir temperatures exceeding 150°C. Confirmation requires slimhole drilling (2-5 inch diameter) for temperature logs and fluid yields, progressing to full-size wells (8-12 inch) for production testing. Volume-based assessments by agencies like the USGS estimate recoverable heat using porosity, permeability, and recharge rates derived from these data.[57][58] Advanced techniques, informed by oil and gas analogs, include 3D seismic imaging for fracture networks and machine learning integration of multi-dataset models to predict reservoir viability. Success rates hover at 20-30% for exploratory wells, underscoring the empirical necessity of iterative testing amid heterogeneous subsurface conditions. Emerging enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) broaden exploration to non-conventional areas by targeting hot dry rock via hydraulic stimulation, as demonstrated in USGS-supported pilots in the Great Basin.[59][60]| Leading Countries by Installed Capacity (2024, MW) | Source |

|---|---|

| United States: 3,937 | ThinkGeoEnergy industry report, corroborated by DOE estimates[14][56] |

| Indonesia: 2,600 | EIA |

| Philippines: ~1,900 | IRENA aggregates[55] |

| Turkey: ~1,700 | IRENA aggregates[55] |

| New Zealand: ~1,000 | IRENA aggregates[55] |

Generation Technologies

Conventional steam-based systems

Conventional steam-based geothermal power systems extract high-temperature fluids from hydrothermal reservoirs to produce steam that drives turbines for electricity generation. These systems encompass dry steam plants, which utilize naturally occurring steam reservoirs, and flash steam plants, which convert pressurized hot water into steam through rapid depressurization. Such technologies are suitable for reservoirs with temperatures exceeding 180°C and are among the earliest and most direct methods of geothermal electricity production.[61][14] Dry steam plants pipe superheated steam directly from production wells to turbines without intermediate separation, minimizing equipment complexity. Steam exits the turbine as low-pressure exhaust, which is condensed using cooling towers or air coolers before reinjection into the reservoir to sustain pressure and reduce subsidence risks. The Larderello field in Italy hosted the world's first dry steam plant in 1904, initially generating enough power for five light bulbs, and remains operational with expansions exceeding 800 MW capacity as of recent assessments. Other notable examples include The Geysers in California, the largest complex of its type, peaking at over 2,000 MW in the 1980s but now operating at about 725 MW due to reservoir management needs. These plants achieve thermal efficiencies around 20-25%, limited by the relatively low steam temperatures compared to fossil fuel cycles.[2][36][62] Flash steam plants, the most prevalent conventional type comprising over 70% of global geothermal capacity, pump hot pressurized water from depths of 1-3 km into surface separators where pressure drops cause flashing—a phase change producing steam at 150-200°C. Single-flash configurations use one separator, while double- or triple-flash systems cascade multiple stages to capture additional steam from separated brine, boosting efficiency by 5-10%. The steam drives turbines, and spent brine is reinjected after silica scaling mitigation, though non-condensable gases like CO2 and H2S require abatement to prevent turbine corrosion and emissions exceeding 100 g/kWh in some fields. Pioneered in New Zealand's Wairakei plant in 1958, flash systems dominate in regions like Indonesia and the Philippines due to abundant liquid-dominated reservoirs.[61][14][63] Both subtypes offer high capacity factors over 90%, providing baseload power with minimal fuel costs, but site specificity confines deployment to volcanic or tectonically active areas covering less than 1% of land surface. Resource depletion from over-extraction has occurred, as at The Geysers, necessitating advanced reinjection; environmental releases include trace minerals and gases, though lifecycle emissions remain below 50 g CO2eq/kWh—far lower than coal's 800+ g. Corrosion from geothermal fluids and induced seismicity from reinjection pose operational challenges, addressed via material alloys and monitoring.[64][2][62]Binary cycle systems

Binary cycle systems in geothermal power generation utilize a closed-loop process where geothermal brine, typically at temperatures between 100°C and 200°C, heats a secondary working fluid with a lower boiling point, such as isobutane, pentane, or refrigerants like R134a, without direct contact between the geothermal fluid and the turbine. This indirect heat exchange occurs in a heat exchanger, vaporizing the secondary fluid to drive a turbine connected to a generator, after which the fluid is condensed and recycled. The geothermal brine, which remains in a liquid state, is reinjected into the reservoir to sustain pressure and minimize surface emissions. These systems are particularly suited for moderate-temperature resources that are uneconomical for dry steam or flash steam plants, expanding the viable geothermal resource base by enabling utilization of fluids as low as 57°C in some advanced configurations, though most operate above 100°C for efficiency. Efficiencies typically range from 10% to 15%, lower than flash or dry steam systems due to the temperature differential, but they offer higher resource recovery and reduced scaling or corrosion issues since the turbine does not contact corrosive geothermal fluids. A key advantage is near-zero air emissions, as non-condensable gases in the brine are reinjected, contrasting with open-cycle systems that may release CO2 or H2S. The first commercial binary cycle plant, the 11 MW Raft River facility in Idaho, USA, began operation in 1981 using isobutane as the working fluid, demonstrating feasibility for lower-temperature fields. By 2023, binary cycles accounted for about 15% of global geothermal capacity, with notable installations including the 34 MW McKay Canyon plant in Nevada (online 1985) and larger dual-flash/binary hybrids like the 117 MW Heber plant in California (1985). In regions like the Philippines and Indonesia, binary systems support baseload power from non-volcanic fields, such as the 49 MW Leyte plant. Ongoing research focuses on supercritical CO2 as a working fluid to boost efficiency up to 20% in pilots, though commercialization remains limited as of 2025.Enhanced and next-generation systems

Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) expand geothermal power potential by engineering reservoirs in hot dry rock formations lacking natural permeability, through hydraulic fracturing and water injection to create artificial fluid pathways for heat extraction.[20] Unlike conventional systems reliant on pre-existing hydrothermal reservoirs, EGS targets deeper, hotter crystalline rock, enabling deployment in diverse geological settings beyond volcanic regions.[65] Advancements since the 1970s, including improved drilling techniques and reservoir stimulation, have boosted productivity and reduced costs, with U.S. Department of Energy estimates indicating EGS could supply over 65 million American homes.[66] [45] Key progress includes horizontal drilling borrowed from oil and gas, enhancing well connectivity and heat exchange efficiency, as demonstrated in projects like Fervo Energy's Cape Station in Nevada, which achieved flow rates exceeding 63 liters per second in 2023 tests.[45] [67] The U.S. FORGE site in Utah has validated EGS viability through iterative field experiments, informing scalable designs with productivity indices up to 0.02 MW per well.[20] Recent cost reductions, estimated at 50% from 2021-2023 via optimized stimulation and diagnostics, position EGS for commercial competitiveness, potentially delivering baseload power at levelized costs approaching $50-100/MWh by 2030.[68] [69] Next-generation variants push boundaries further, such as supercritical geothermal systems accessing fluids above 374°C and 220 bar, yielding up to tenfold energy density compared to subcritical conditions through deeper drilling into superhot rock.[70] [71] Initiatives like Japan's ICDP project and U.S. efforts under H.R. 8665 aim to develop these by advancing millimeter-wave drilling for 10-20 km depths, though challenges persist in material durability and seismicity management.[72] [73] Closed-loop systems, exemplified by Eavor's Eavor-Loop technology, circulate sealed working fluids in coaxial wells, minimizing water loss and environmental risks while targeting consistent output independent of reservoir permeability.[67] As of 2025, these innovations, supported by investments exceeding $500 million in startups like Fervo and Quaise, signal EGS maturation toward contributing 100 GW in the U.S. by 2050, contingent on sustained R&D in fracture longevity and induced seismicity mitigation.[74] [45]Production and Deployment

Current global capacity and output (as of 2025)

As of the end of 2024, global installed geothermal power capacity reached approximately 15.4 gigawatts (GW), reflecting a modest annual growth rate of less than 2% from prior years, according to data compiled by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).[55] Independent trackers, such as Global Energy Monitor, report slightly higher operating capacity at 16.17 GW across 770 units in 49 countries, incorporating updates for smaller or off-grid installations potentially undercounted in aggregated statistics.[5] This capacity has expanded slowly due to high upfront exploration and drilling costs, with cumulative additions since 2010 totaling under 5 GW globally.[75] In 2024, geothermal electricity generation worldwide approximated 98 terawatt-hours (TWh), accounting for about 0.3% of total global electricity output, consistent with capacity utilization factors typically ranging from 70-90% in mature hydrothermal fields.[76] This output remained stable year-over-year, as new capacity additions—primarily in Indonesia, Turkey, and New Zealand—offset minor declines in older fields due to reservoir depletion without significant reinjection enhancements.[77] Projections for 2025 indicate continued incremental growth, potentially adding 0.4-0.5 GW, driven by policy incentives in regions with high resource potential, though enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) contributed negligibly to current totals.[60]Major operational projects and leading nations

The United States holds the largest installed geothermal power capacity worldwide, totaling 3,937 MW as of the end of 2024, primarily concentrated in California, Nevada, and Hawaii.[56] Indonesia ranks second with 2,653 MW, driven by volcanic resources in Sumatra and Java, where projects like the Wayang Windu and Salak fields contribute significantly to national output.[78] The Philippines follows with 1,984 MW, relying on fields such as Tiwi and Mak-Ban, which have been operational since the 1970s and supply about 10% of the country's electricity.[78] Turkey has expanded rapidly to 1,734 MW, with key developments in western Anatolia, including the Kızıldere and Aydın fields.[78] New Zealand operates around 1,000 MW, with pioneering stations like Wairakei (operational since 1958) and modern expansions at Tauhara, supporting over 18% of its electricity needs from geothermal sources.[56] Iceland generates nearly 30% of its electricity from 755 MW of geothermal capacity, exemplified by the Hellisheiði plant (303 MW, commissioned 2006) and Nesjavellir (120 MW), leveraging high-enthalpy resources for baseload power and district heating.[56] Other notable leaders include Kenya (with Olkaria complex exceeding 900 MW across multiple units since 1981 expansions), Mexico (Cerro Prieto at 720 MW), and Italy (Larderello, the world's first grid-connected plant from 1904, now at ~800 MW).[79][56]| Country | Installed Capacity (MW, end-2024) |

|---|---|

| United States | 3,937 |

| Indonesia | 2,653 |

| Philippines | 1,984 |

| Turkey | 1,734 |

| New Zealand | ~1,000 |

| Iceland | 755 |

Economic Analysis

Investment and operational costs

The capital costs for constructing geothermal power plants, encompassing exploration, drilling, surface facilities, and power generation equipment, typically range from $4,000 to $6,000 per kilowatt of installed capacity for conventional hydrothermal systems as of 2023.[80][81] For a representative 50-megawatt binary-cycle plant, the overnight capital cost averages $3,963 per kilowatt, excluding financing and escalation, though actual totals can reach approximately $198 million due to site-specific factors like resource assessment and well drilling, which often constitute up to 50% of the total.[80][82] Flash steam plants may incur slightly lower costs at $4,350 to $5,922 per kilowatt, while binary-cycle variants, which operate at lower temperatures, trend higher at around $4,759 per kilowatt in base-year estimates.[81] Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS), reliant on hydraulic stimulation of hot dry rock, demand substantially more investment, with capital expenditures projected at $6,500 to $7,600 per kilowatt owing to deeper drilling and reservoir engineering challenges.[81] These upfront investments exceed those of variable renewables like solar photovoltaic ($700–$1,000 per kilowatt) primarily because geothermal development involves high-risk geophysical exploration, including seismic surveys and test wells, which can fail to yield viable reservoirs in 20–30% of cases, necessitating dry-hole contingencies.[83][81] Regional variations further influence costs; for instance, U.S. West Coast sites adjusted for labor and permitting may add 10–25% to base figures, yielding $4,500–$4,900 per kilowatt in areas like California's Central Valley or San Francisco Bay.[80] Projections from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory indicate moderate cost reductions of 10–20% by 2035 through improved drilling rates of penetration and larger plant scales (e.g., 100-megawatt units), though EGS commercialization remains contingent on achieving these efficiencies to approach conventional viability.[81] Operational and maintenance (O&M) costs for geothermal plants are comparatively low, reflecting their baseload reliability and absence of fuel expenses, with fixed O&M averaging $125–$150 per kilowatt-year across recent projects.[80][84] Variable O&M is negligible at approximately $0 per megawatt-hour, as operations involve minimal incremental inputs beyond routine monitoring and well-field management to sustain steam production.[80] However, these costs can escalate with reservoir complexity, such as scaling or corrosion mitigation in binary systems, or induced permeability maintenance in EGS, potentially adding 10–20% to fixed expenditures if production declines require reinjection or redrilling.[81][85] Over a typical 30–50-year plant lifespan, these low O&M profiles contribute to favorable long-term economics, though initial exploration risks amplify perceived hurdles relative to dispatchable fossil alternatives.[62]Levelized cost comparisons and profitability

The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for geothermal power, which represents the average net present cost of electricity generation over a plant's lifetime including capital, operations, maintenance, and fuel costs, typically ranges from USD 60 to 82 per MWh for conventional hydrothermal systems in recent assessments.[75][86] According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the global weighted-average LCOE for newly commissioned geothermal projects decreased by 16% in 2024 to approximately USD 60/kWh, reflecting efficiencies in drilling and project execution, though values vary by location with lows of USD 33/kWh in Turkey due to favorable geology and policy support.[75][84] Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) remain higher, often exceeding USD 100/MWh due to exploratory risks and advanced stimulation costs, limiting their current scalability.[81]| Technology | Unsubsidized LCOE (USD/MWh, 2024 estimates) | Capacity Factor (%) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geothermal (hydrothermal) | 60–82 | 75–90 | Baseload, low O&M; high upfront CAPEX offset by longevity >30 years.[86][87][81] |

| Utility-scale solar PV | 24–96 | 20–30 | Intermittent; requires storage for dispatchability, raising effective costs.[86] |

| Onshore wind | 24–75 | 35–50 | Variable output; grid balancing adds externalities not captured in basic LCOE.[86] |

| Combined-cycle gas | 45–74 | 50–60 | Fuel-dependent; lower than geothermal in some low-gas-price regions but volatile.[86][87] |

| Coal (new supercritical) | 70–117 | 60–80 | Includes emissions costs; declining viability due to regulatory pressures.[87] |

| Nuclear (new build) | 140–220 | 90+ | High CAPEX overruns common; longer lead times than geothermal.[86] |

Role of subsidies and market incentives

Geothermal power projects often require substantial upfront capital for exploration and drilling, with success rates for wells as low as 20-30% in some regions, necessitating subsidies to mitigate financial risks and attract private investment.[91] Public finance instruments, including grants, loan guarantees, and equity support, cover 76-90% of investments in many developing projects, with governments absorbing approximately 58.5% of total costs to enable deployment.[92] In the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provided enhanced investment tax credits (ITC) and production tax credits (PTC) for geothermal, which persisted in modified form under the 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act, allowing baseload sources like geothermal to qualify for up to 48E ITC or 45Y PTC rates.[93] These incentives have facilitated over $1.7 billion in North American geothermal funding in the first quarter of 2025 alone, primarily for next-generation enhanced geothermal systems (EGS).[94] Market incentives such as feed-in tariffs (FITs) guarantee renewable producers fixed, above-market prices for electricity fed into the grid, promoting geothermal by ensuring revenue stability over long project lifespans of 30-50 years.[95] Countries like Indonesia and Turkey have used FITs alongside subsidies to accelerate private-sector involvement, contributing to Turkey's geothermal capacity growth from minimal levels in the early 2000s to over 1.7 GW by 2023.[96] In Europe, renewable portfolio standards and similar mandates, combined with EGS-focused grants totaling hundreds of millions in 2024 from nations like Germany and the Netherlands, have supported pilot deployments despite higher initial costs compared to variable renewables.[97] Comparative analyses of FIT schemes indicate they enhance geothermal investment returns by 10-20% in risk-adjusted terms, though efficacy varies by degression rates and contract durations, with longer-term fixed tariffs proving more effective for capital-intensive technologies.[98] Critics argue that ongoing subsidies distort market signals and delay cost reductions through innovation, as geothermal's levelized costs—currently $100-240/MWh for EGS—remain higher than unsubsidized fossil alternatives without incentives.[99] However, proponents, including the International Energy Agency, contend that targeted support for exploration risk-sharing and drilling advancements could reduce costs by up to 80% by 2035, enabling unsubsidized competitiveness in baseload power markets.[60] Empirical evidence from U.S. Department of Energy programs shows that federal risk mitigation has increased successful well completions and lowered effective capital costs by 15-25% in subsidized projects, underscoring subsidies' role in bridging the gap until technological maturation.[100]Environmental and Sustainability Impacts

Emission profiles and climate benefits

Geothermal power plants exhibit some of the lowest lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions among electricity generation technologies, typically ranging from 10 to 50 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour (g CO2eq/kWh).[101] A systematic review of life cycle assessments by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) found median values of 11.3 g CO2eq/kWh for high-temperature binary cycle systems, 47 g CO2eq/kWh for high-temperature flash systems, and 32 g CO2eq/kWh for enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) using binary cycles.[102] These figures encompass emissions from exploration, drilling, plant construction, operation, and decommissioning, with the majority stemming from upfront material use and reservoir-derived gases rather than fuel combustion.[102] Operational emissions arise primarily from naturally dissolved non-condensable gases in geothermal fluids, including CO2 (accounting for about 10% of air emissions in open-loop systems) and methane (in smaller quantities), released during steam separation or reinjection processes.[103] Non-GHG emissions such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S), ammonia (NH3), and trace metals (e.g., arsenic, mercury) can occur but are site-specific and often mitigated through abatement technologies like scrubbing or reinjection, reducing H2S releases to low levels in modern plants.[104] [105] Unlike fossil fuels, geothermal avoids combustion-related pollutants like NOx and SOx, emitting 97% less sulfur compounds and 99% less CO2 on a lifecycle basis compared to coal or natural gas plants.[87]| Technology | Lifecycle GHG Emissions (g CO2eq/kWh, median or range) |

|---|---|

| Geothermal (various) | 10–50[101] |

| Coal | 820–1,000 |

| Natural Gas Combined Cycle | 400–500 |

| Solar PV | 40–50 |

| Onshore Wind | 10–12 |

| Nuclear | 10–15 |