Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Imperial units

View on Wikipedia

The imperial system of units, imperial system or imperial units (also known as British Imperial[1] or Exchequer Standards of 1826) is the system of units first defined in the British Weights and Measures Act 1824 and continued to be developed through a series of Weights and Measures Acts and amendments.

The imperial system developed from earlier English units as did the related but differing system of customary units of the United States. The imperial units replaced the Winchester Standards, which were in effect from 1588 to 1825.[2] The system came into official use across the British Empire in 1826.

By the late 20th century, most nations of the former empire had officially adopted the metric system as their main system of measurement, but imperial units are still used alongside metric units in the United Kingdom and in some other parts of the former empire, notably Canada.

The modern UK legislation defining the imperial system of units is given in the Weights and Measures Act 1985 (as amended).[3]

Implementation

[edit]The Weights and Measures Act 1824 was initially scheduled to go into effect on 1 May 1825.[4] The Weights and Measures Act 1825 pushed back the date to 1 January 1826.[5] The 1824 act allowed the continued use of pre-imperial units provided that they were customary, widely known, and clearly marked with imperial equivalents.[4]

Apothecaries' units

[edit]

Apothecaries' units are not mentioned in the acts of 1824 and 1825. At the time, apothecaries' weights and measures were regulated "in England, Wales, and Berwick-upon-Tweed" by the London College of Physicians, and in Ireland by the Dublin College of Physicians. In Scotland, apothecaries' units were unofficially regulated by the Edinburgh College of Physicians. The three colleges published, at infrequent intervals, pharmacopoeias, the London and Dublin editions having the force of law.[6][7]

Imperial apothecaries' measures, based on the imperial pint of 20 fluid ounces, were introduced by the publication of the London Pharmacopoeia of 1836,[8][9] the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia of 1839,[10] and the Dublin Pharmacopoeia of 1850.[11] The Medical Act 1858 transferred to the Crown the right to publish the official pharmacopoeia and to regulate apothecaries' weights and measures.[12]

Units

[edit]Length

[edit]Metric equivalents in this article usually assume the latest official definition. Before this date, the most precise measurement of the imperial Standard Yard was 0.914398415 metres.[13]

| Unit | Abbr. or symbols | Relative to previous | Feet | Metres | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| twip | 1⁄17280 | 0.000017638 | typographic measure | ||

| thou | th | 1.44 twip | 1⁄12000 | 0.0000254 |

Abbreviation of "thousandth of an inch". Also known as mil.[14] |

| barleycorn | 333+1⁄3 th | 1⁄36 | 0.00846 | 1⁄3 in | |

| inch | in (″) | 3 Bc | 1⁄12 | 0.0254 | 1 metre ≡ 39 47⁄127 inches |

| hand | hh | 4 in | 1⁄3 | 0.1016 | Used to measure the height of horses |

| foot | ft (′) | 3 h | 1 | 0.3048 | 12 in |

| yard | yd | 3 ft | 3 | 0.9144 | Defined as exactly 0.9144 m by the international yard and pound agreement of 1959 |

| chain | ch | 22 yd | 66 | 20.1168 | 100 links, 4 rods, or 1⁄10 of a furlong. The distance between the two wickets on a cricket pitch. |

| furlong | fur | 10 chains | 660 | 201.168 | 220 yd |

| mile | mi | 8 furlongs | 5280 | 1609.344 | 1760 yd or 80 chains |

| league | lea | 3 miles | 15840 | 4828.032 | |

| Maritime units | |||||

| fathom | ftm | 2.02667 yd | 6.0761 | 1.852 | The British Admiralty in practice used a fathom of 6 ft. This was despite its being 1⁄1000 of a nautical mile (i.e. 6.08 ft) until the adoption of the international nautical mile.[15] |

| cable | 100 fathoms | 607.61 | 185.2 | One tenth of a nautical mile. Equal to 100 fathoms under the strict definition. | |

| nautical mile | nmi | 10 cables | 6076.1 | 1852 | Used for measuring distances at sea (and also in aviation) and approximately equal to one arc minute of a great circle. Until the adoption of the international definition of 1852 m in 1970, the British nautical (Admiralty) mile was defined as 6080 ft.[16] |

| Gunter's survey units (17th century onwards) | |||||

| link | 7.92 in | 66⁄100 | 0.201168 | 1⁄100 of a chain and 1⁄1000 of a furlong | |

| rod | 25 links | 66⁄4 | 5.0292 | The rod is also called pole or perch and is equal to 5+1⁄2 yards | |

Area

[edit]| Unit | Abbr. or symbol | Relative to previous | Relation to units of length | Square feet | Square yards | Acres | Square metres | Hectares |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| perch* | 1 rd × 1 rd | 272+1⁄4 | 30+1⁄4 | 1⁄160 | 25.29285264 | 0.002529285264 | ||

| rood | 40 perches | 1 furlong × 1 rd[17] | 10890 | 1210 | 1⁄4 | 1011.7141056 | 0.10117141056 | |

| acre | 4 roods | 1 furlong × 1 chain | 43560 | 4840 | 1 | 4046.8564224 | 0.40468564224 | |

| square mile | sq mi | 640 acres | 1 mile × 1 mile | 27878400 | 3097600 | 640 | 2589988.110336 | 258.9988110336 |

| Note: *The square rod has been called a pole or perch or, more properly, square pole or square perch for centuries. | ||||||||

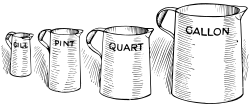

Volume

[edit]

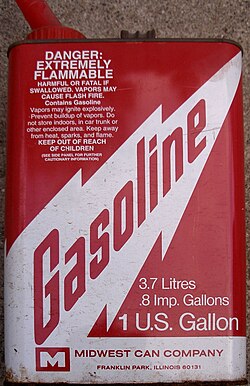

The Weights and Measures Act 1824 invalidated the various different gallons in use in the British Empire, declaring them to be replaced by the statute gallon (which became known as the imperial gallon), a unit close in volume to the ale gallon. The 1824 act defined as the volume of a gallon to be that of 10 pounds (4.54 kg) of distilled water weighed in air with brass weights with the barometer standing at 30 inches of mercury (102 kPa) at a temperature of 62 °F (17 °C).[18] The 1824 act went on to give this volume as 277.274 cubic inches (4.54371 litres).[18] The Weights and Measures Act 1963 refined this definition to be the volume of 10 pounds of distilled water of density 0.998859 g/mL weighed in air of density 0.001217 g/mL against weights of density 8.136 g/mL, which works out to 4.546092 L.[nb 1] The Weights and Measures Act 1985 defined a gallon to be exactly 4.54609 L (approximately 277.4194 cu in).[19]

| Unit | Imperial ounces |

Imperial pints |

Millilitres | Cubic inches | US ounces | US pints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fluid ounce (fl oz) | 1 | 1⁄20 | 28.4130625 | 1.7339 | 0.96076 | 0.060047 |

| gill (gi) | 5 | 1⁄4 | 142.0653125 | 8.6694 | 4.8038 | 0.30024 |

| pint (pt) | 20 | 1 | 568.26125 | 34.677 | 19.215 | 1.2009 |

| quart (qt) | 40 | 2 | 1136.5225 | 69.355 | 38.430 | 2.4019 |

| gallon (gal) | 160 | 8 | 4546.09 | 277.42 | 153.72 | 9.6076 |

| Note: The millilitre equivalences are exact, but cubic-inch and US measures are correct to 5 significant figures. | ||||||

| Unit | gallons | Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| pint | 1⁄8 | 34.76 cu in (569.6 mL; 0.5696 L) |

| quart | 1⁄4 | 69.32 cu in (1.1360 L) |

| gallon | 1 | 277.274 cu in (4.54371 L) |

| peck | 2 | 554.548 cu in (9.08741 L) |

| bushel | 8 | 2,218.192 cu in (36.34965 L) |

| quarter | 64 | 17,745.536 cu in (290.79723 L) |

| Note: The 1824 Act removed the distinction between liquid and dry measure, specifying instead that the dry quantities shall be unheaped. The metric equivalences shown are approximate. | ||

British apothecaries' volume measures

[edit]These measurements were in use from 1826, when the new imperial gallon was defined. For pharmaceutical purposes, they were replaced by the metric system in the United Kingdom on 1 January 1971.[20][21] In the US, though no longer recommended, the apothecaries' system is still used occasionally in medicine, especially in prescriptions for older medications.[22][23]

| Unit | Symbols and abbreviations |

Relative to previous |

Exact metric value[note 1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| minim | ♏︎, |

(1⁄9600 pint) | 59.1938802083 μL |

| fluid scruple | fl ℈, fl s | 20 minims (1⁄480 pint) | 1.18387760416 mL |

| fluid drachm (fluid dram, fluidram) |

ʒ, fl ʒ, fʒ, ƒ 3, fl dr | 3 fluid scruples (1⁄160 pint) | 3.5516328125 mL |

| fluid ounce | ℥, fl ℥, f℥, ƒ ℥, fl oz | 8 fluid drachms | 28.4130625 mL |

| pint | O, pt | 20 fluid ounces | 568.26125 mL |

| gallon | C, gal | 8 pints | 4.54609 L |

Note:

| |||

Mass and weight

[edit]In the 19th and 20th centuries, the UK used three different systems for mass and weight.

- troy weight, used for precious metals;

- avoirdupois weight, used for most other purposes; and

- apothecaries' weight, now virtually unused since the metric system is used for all scientific purposes.

The distinction between mass and weight is not always clearly drawn. Strictly a pound is a unit of mass, but it is commonly referred to as a weight. When a distinction is necessary, the term pound-force may refer to a unit of force rather than mass. The troy pound (373.2417216 g) was made the primary unit of mass by the Weights and Measures Act 1824 and its use was abolished in the UK on 1 January 1879,[30] with only the troy ounce (31.1034768 g) and its decimal subdivisions retained.[31] The Weights and Measures Act 1855 made the avoirdupois pound the primary unit of mass.[32] In all the systems, the fundamental unit is the pound, and all other units are defined as fractions or multiples of it.

| Unit | Pounds | In SI units | Notes | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grain (gr) | 1⁄7000 | 64.79891 mg | Exactly 64.79891 milligrams. | ||||||||||||||||||

| drachm (dr) | 1⁄256 | 1.7718451953125 g | A dram is 1⁄16 of an ounce | ||||||||||||||||||

| ounce (oz) | 1⁄16 | 28.349523125 g | An ounce is 1⁄16 of a pound | ||||||||||||||||||

| pound (lb) | 1 | 0.45359237 kg | Defined by the Units of Measurement Regulations 1994 (SI 1994/2867)[33] | ||||||||||||||||||

| stone (st) | 14 | 6.35029318 kg | The plural stone is often used when providing a weight (e.g. "this sack weighs 8 stone").[34] A person's weight is usually quoted in stone and pounds in English-speaking countries that use the avoirdupois system, with the exception of the United States and Canada, where it is usually quoted in pounds. | ||||||||||||||||||

| quarter (qr or qtr) | 28 | 12.70058636 kg | One quarter (literally a quarter of a hundredweight) is equal to two stone or 28 pounds. The term quarter is also used in retail contexts, where it refers to four ounces, i.e. a quarter of a pound. (The 1824 act defined a quarter as a unit of volume, as above: thus a 'quarter of wheat', 64 gallons, would weigh about 494 lb.[35]). | ||||||||||||||||||

| hundredweight (cwt) | 112 | 50.80234544 kg | One imperial hundredweight is equal to eight stone. This is the long hundredweight, 112 pounds, as opposed to the short hundredweight of 100 pounds used in the United States and Canada.[36] | ||||||||||||||||||

| ton (ton) | 2240 | 1016.0469088 kg | Twenty hundredweight equals a ton (as in the US and Canadian[36] systems). The imperial hundredweight is 12% greater than the US and Canadian one. The imperial ton (or long ton) is 2240 pounds, which is much closer to a tonne (about 2204.6 pounds), compared to the 10.7% smaller North American short ton of 2000 pounds (907.185 kg). The symbol “t” is used to denote a tonne. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gravitational units | |||||||||||||||||||||

| slug (slug) | 32.17404856 | 14.59390294 kg | The slug, a unit associated with imperial and US customary systems, is a mass that accelerates by 1 ft/s2 when a force of one pound (lbf) is exerted on it.[37]

| ||||||||||||||||||

Natural equivalents

[edit]The 1824 Act of Parliament defined the yard and pound by reference to the prototype standards, and it also defined the values of certain physical constants, to make provision for re-creation of the standards if they were to be damaged. For the yard, the length of a pendulum beating seconds at the latitude of Greenwich at mean sea level in vacuo was defined as 39.1393 inches. For the pound, the mass of a cubic inch of distilled water at an atmospheric pressure of 30 inches of mercury and a temperature of 62° Fahrenheit was defined as 252.458 grains, with there being 7,000 grains per pound.[4]

Following the destruction of the original prototypes in the 1834 Houses of Parliament fire, it proved impossible to recreate the standards from these definitions, and a new Weights and Measures Act 1855 was passed which permitted the recreation of the prototypes from recognized secondary standards.[32]

Current use

[edit]United Kingdom

Since the Weights and Measures Act 1985, British law defines base imperial units in terms of their metric equivalent. The metric system is routinely used in business and technology within the United Kingdom, with imperial units remaining in widespread use amongst the public.[38] All UK roads use the imperial system except for weight limits, and newer height or width restriction signs give metric alongside imperial.[39]

Traders in the UK may accept requests from customers specified in imperial units, and scales which display in both unit systems are commonplace in the retail trade. Metric price signs may be accompanied by imperial price signs provided that the imperial signs are no larger and no more prominent than the metric ones.

The United Kingdom completed its official partial transition to the metric system in 1995, with imperial units still legally mandated for certain applications such as draught beer and cider,[40] and road-signs.[41] Therefore, the speedometers on vehicles sold in the UK must be capable of displaying miles per hour. Even though the troy pound was outlawed in the UK in the Weights and Measures Act 1878, the troy ounce may still be used for the weights of precious stones and metals. The original railways (many built in the Victorian era) are a big user of imperial units, with distances officially measured in miles and yards or miles and chains, and also feet and inches, and speeds are in miles per hour.

Some British people still use one or more imperial units in everyday life for distance (miles, yards, feet, and inches) and some types of volume measurement (especially milk and beer in pints; rarely for canned or bottled soft drinks, or petrol).[38][42] As of February 2021[update], many British people also still use imperial units in everyday life for body weight (stones and pounds for adults, pounds and ounces for babies).[43] Government documents aimed at the public may give body weight and height in imperial units as well as in metric.[44] A survey in 2015 found that many people did not know their body weight or height in both systems.[45] As of 2017, people under the age of 40 preferred the metric system but people aged 40 and over preferred the imperial system.[46] As in other English-speaking countries, including Australia, Canada and the United States, the height of horses is usually measured in hands, standardised to 4 inches (102 mm). Fuel consumption for vehicles is commonly stated in miles per gallon (mpg), though official figures always include litres per 100 km equivalents and fuel is sold in litres. When sold draught in licensed premises, beer and cider must be sold in pints, half-pints or third-pints.[47] Cow's milk is available in both litre- and pint-based containers in supermarkets and shops. Areas of land associated with farming, forestry and real estate are commonly advertised in acres and square feet but, for contracts and land registration purposes, the units are always hectares and square metres.[48]

Office space and industrial units are usually advertised in square feet. Steel pipe sizes are sold in increments of inches, while copper pipe is sold in increments of millimetres. Road bicycles have their frames measured in centimetres, while off-road bicycles have their frames measured in inches. Display sizes for screens on television sets and computer monitors are always diagonally measured in inches. Food sold by length or width, e.g. pizzas or sandwiches, is generally sold in inches. Clothing is usually sized in inches, with the metric equivalent often shown as a small supplementary indicator. Gas is usually measured by the cubic foot or cubic metre, but is billed like electricity by the kilowatt hour.[49]

Pre-packaged products can show both metric and imperial measures, and it is also common to see imperial pack sizes with metric only labels, e.g. a 1 lb (454 g) tin of Lyle's Golden Syrup is always labelled 454 g with no imperial indicator. Similarly most jars of jam and packs of sausages are labelled 454 g with no imperial indicator.

India

[edit]India began converting to the metric system from the imperial system between 1955 and 1962. The metric system in weights and measures was adopted by the Indian Parliament in December 1956 with the Standards of Weights and Measures Act, which took effect beginning 1 October 1958. By 1962, metric units became "mandatory and exclusive."[50]

Today all official measurements are made in the metric system. In common usage some older Indians may still refer to imperial units. Some measurements, such as the heights of mountains, are still recorded in feet. Tyre rim diameters are still measured in inches, as used worldwide. Industries like the construction and the real estate industry still use both the metric and the imperial system though it is more common for sizes of homes to be given in square feet and land in acres.[51]

In Standard Indian English, as in Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, Singaporean, and British English, metric units such as the litre, metre, and tonne utilise the traditional spellings brought over from French, which differ from those used in the United States and the Philippines. The imperial long ton is invariably spelt with one 'n'.[51]

Hong Kong

[edit]Hong Kong has three main systems of units of measurement in current use:

- The Chinese units of measurement of the Qing Empire (no longer in widespread use in China);

- British imperial units; and

- The metric system.

In 1976 the Hong Kong Government started the conversion to the metric system, and as of 2012 measurements for government purposes, such as road signs, are almost always in metric units. All three systems are officially permitted for trade,[52] and in the wider society a mixture of all three systems prevails.

The Chinese system's most commonly used units for length are 里 (lei5), 丈 (zoeng6), 尺 (cek3), 寸 (cyun3), 分 (fan1) in descending scale order. These units are now rarely used in daily life, the imperial and metric systems being preferred. The imperial equivalents are written with the same basic Chinese characters as the Chinese system. In order to distinguish between the units of the two systems, the units can be prefixed with "Ying" (英, jing1) for the imperial system and "Wa" (華, waa4) for the Chinese system. In writing, derived characters are often used, with an additional 口 (mouth) radical to the left of the original Chinese character, for writing imperial units. The most commonly used units are the mile or "li" (哩, li1), the yard or "ma" (碼, maa5), the foot or "chek" (呎, cek3), and the inch or "tsun" (吋, cyun3).

The traditional measure of flat area is the square foot (方呎, 平方呎, fong1 cek3, ping4 fong1 cek3) of the imperial system, which is still in common use for real estate purposes. The measurement of agricultural plots and fields is traditionally conducted in 畝 (mau5) of the Chinese system.

For the measurement of volume, Hong Kong officially uses the metric system, though the gallon (加侖, gaa1 leon4-2) is also occasionally used.

Canada

[edit]

During the 1970s, the metric system and SI units were introduced in Canada to replace the imperial system. Within the government, efforts to implement the metric system were extensive; almost any agency, institution, or function provided by the government uses SI units exclusively. Imperial units were eliminated from all public road signs and both systems of measurement will still be found on privately owned signs, such as the height warnings at the entrance of a parkade. In the 1980s, momentum to fully convert to the metric system stalled when the government of Brian Mulroney was elected. There was heavy opposition to metrication and as a compromise the government maintains legal definitions for and allows use of imperial units as long as metric units are shown as well.[53][54][55][56]

The law requires that measured products (such as fuel and meat) be priced in metric units and an imperial price can be shown if a metric price is present.[57][58] There tends to be leniency in regards to fruits and vegetables being priced in imperial units only. Environment Canada still offers an imperial unit option beside metric units, even though weather is typically measured and reported in metric units in the Canadian media. Some radio stations near the United States border (such as CIMX and CIDR) primarily use imperial units to report the weather. Railways in Canada also continue to use imperial units.

Imperial units are still used in ordinary conversation. Today, Canadians typically use a mix of metric and imperial measurements in their daily lives. The use of the metric and imperial systems varies by age. The older generation mostly uses the imperial system, while the younger generation more often uses the metric system. Quebec has implemented metrication more fully. [citation needed] Newborns are measured in SI at hospitals, but the birth weight and length is also announced to family and friends in imperial units. Drivers' licences use SI units, though many English-speaking Canadians give their height and weight in imperial. In livestock auction markets, cattle are sold in dollars per hundredweight (short), whereas hogs are sold in dollars per hundred kilograms. Imperial units still dominate in recipes, construction, house renovation and gardening.[59][60][61][62][63] Land is now surveyed and registered in metric units whilst initial surveys used imperial units. For example, partitioning of farmland on the prairies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was done in imperial units; this accounts for imperial units of distance and area retaining wide use in the Prairie Provinces.

In English-speaking Canada commercial and residential spaces are mostly (but not exclusively) constructed using square feet, while in French-speaking Quebec commercial and residential spaces are constructed in metres and advertised using both square metres and square feet as equivalents. Carpet or flooring tile is purchased by the square foot, but less frequently also in square metres.[64][65] Motor-vehicle fuel consumption is reported in both litres per 100 km and statute miles per imperial gallon,[66] leading to the erroneous impression that Canadian vehicles are 20% more fuel-efficient than their apparently identical American counterparts for which fuel economy is reported in statute miles per US gallon (neither country specifies which gallon is used). Canadian railways maintain exclusive use of imperial measurements to describe train length (feet), train height (feet), capacity (tons), speed (mph), and trackage (miles).[67]

Imperial units also retain common use in firearms and ammunition. Imperial measures are still used in the description of cartridge types, even when the cartridge is of relatively recent invention (e.g., .204 Ruger, .17 HMR, where the calibre is expressed in decimal fractions of an inch). Ammunition that is already classified in metric is still kept metric (e.g., 9×19mm). In the manufacture of ammunition, bullet and powder weights are expressed in terms of grains for both metric and imperial cartridges.

In keeping with the international standard, air navigation is based on nautical units, e.g., the nautical mile, which is neither imperial nor metric, and altitude is measured in imperial feet.[68]

Australia

[edit]While metrication in Australia has largely ended the official use of imperial units, for particular measurements, international use of imperial units is still followed.

- In licensed venues, draught beer and cider is sold in glasses and jugs with sizes based on the imperial fluid ounce, though rounded to the nearest 5 mL.

- Newborns are measured in metric at hospitals, but the birth weight and length is sometimes also announced to family and friends in imperial units.

- Screen sizes, are frequently described in inches instead of or as well as centimetres.

- Property size is infrequently described in acres, but is mostly as square metres or hectares.

- Marine navigation is done in nautical miles, and water-based speed limits are in nautical miles per hour.

- Historical writing and presentations may include pre-metric units to reflect the context of the era represented.

- The illicit drug trade in Australia still often uses imperial measurements, particularly when dealing with smaller amounts closer to end user levels e.g. "8-ball" an 8th of an ounce or 3.5 g; cannabis is often traded in ounces ("oz") and pounds ("p")[citation needed]

- Firearm barrel length are almost always referred by in inches, ammunition is also still measured in grains and ounces as well as grams.

- A persons height is frequently and informally described in feet and inches, but on official records is described in metres.

The influence of British and American culture in Australia has been noted to be a cause for residual use of imperial units of measure.

New Zealand

[edit]New Zealand introduced the metric system on 15 December 1976.[69] Aviation was exempt, with altitude and airport elevation continuing to be measured in feet whilst navigation is done in nautical miles; all other aspects (fuel quantity, aircraft weight, runway length, etc.) use metric units.

Screen sizes for devices such as televisions, monitors and phones, and wheel rim sizes for vehicles, are stated in inches, as is the convention in the rest of the world - and a 1992 study found a continued use of imperial units for birth weight and human height alongside metric units.[70]

Ireland

[edit]Ireland has officially changed over to the metric system since entering the European Union, with distances on new road signs being metric since 1997 and speed limits being metric since 2005. The imperial system remains in limited use – for sales of beer in pubs (traditionally sold by the pint). All other goods are required by law to be sold in metric units with traditional quantities being retained for goods like butter and sausages, which are sold in 454 grams (1 lb) packaging. The majority of cars sold pre-2005 feature speedometers with miles per hour as the primary unit, but with a kilometres per hour display. Often signs such as those for bridge height can display both metric and imperial units. Imperial measurements continue to be used colloquially by the general population especially with height and distance measurements such as feet, inches, and acres as well as for weight with pounds and stones still in common use among people of all ages. Measurements such as yards have fallen out of favour with younger generations. Ireland's railways still use imperial measurements for distances and speed signage.[71][72] Property is usually listed in square feet as well as metres also.

Horse racing in Ireland still continues to use stones, pounds, miles and furlongs as measurements.[73]

Bahamas

[edit]Imperial measurements remain in general use in the Bahamas.

Legally, both the imperial and metric systems are recognised by the Weights and Measures Act 2006.[74]

Belize

[edit]Both imperial units and metric units are used in Belize. Both systems are legally recognized by the National Metrology Act.[75]

Myanmar

[edit]According to the CIA, in June 2009, Myanmar was one of three countries that had not adopted the SI metric system as their official system of weights and measures.[76][unreliable source?] Metrication efforts began in 2011.[77] The Burmese government set a goal to metricate by 2019, which was not met, with the help of the German National Metrology Institute.[78]

Other countries

[edit]Some imperial measurements remain in limited use in Malaysia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and South Africa. Measurements in feet and inches, especially for a person's height, are frequently encountered in conversation and non-governmental publications.

Prior to metrication, it was a common practice in Malaysia for people to refer to unnamed locations and small settlements along major roads by referring to how many miles the said locations were from the nearest major town. In some cases, these eventually became the official names of the locations; in other cases, such names have been largely or completely superseded by new names. An example of the former is Batu 32 (literally "Mile 32" in Malay), which refers to the area surrounding the intersection between Federal Route 22 (the Tamparuli-Sandakan highway) and Federal Route 13 (the Sandakan-Tawau highway). The area is so named because it is 32 miles west of Sandakan, the nearest major town.

Petrol is still sold by the imperial gallon in Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Myanmar, the Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St Kitts and Nevis and St. Vincent and the Grenadines.[citation needed] The United Arab Emirates Cabinet in 2009 issued the Decree No. (270 / 3) specifying that, from 1 January 2010, the new unit sale price for petrol will be the litre and not the gallon, which was in line with the UAE Cabinet Decision No. 31 of 2006 on the national system of measurement, which mandates the use of International System of units as a basis for the legal units of measurement in the country.[79][80][81][82] Sierra Leone switched to selling fuel by the litre in May 2011.[83]

In October 2011, the Antigua and Barbuda government announced the re-launch of the Metrication Programme in accordance with the Metrology Act 2007, which established the International System of Units as the legal system of units. The Antigua and Barbuda government has committed to a full conversion from the imperial system by the first quarter of 2015.[84]

In March 2025, Dubai completed the switch from imperial gallons to cubic metres as the unit to measure water consumption.[85]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ 10 pounds = 4535.9237 grams. @ 0.998859 g/mL => 4546.092 mL

- ^ References for the Table of British apothecaries' volume units: Unit column;[24][25]: C-7 [26] Symbols & abbreviations column;[22][23][24][25]: C-5, C-17–C-18 [26][27][28] Relative to previous column;[24][25]: C-7 Exact metric value column – fluid ounce, pint and gallon,[29] all other values calculated using value for fluid ounce and the Relative to previous column's values.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Britannica Educational Publishing (2010). The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-61530-218-5. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Chaney, Henry James (1897). A Practical Treatise on the Standard Weights and Measures in Use in the British Empire with some account of the metric system. Eyre and Spottiswoode. p. 3. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Weights and Measures Act 1985". legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Great Britain (1824). The statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1807-1865). His Majesty's statute and law printers. pp. 339–354. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ Great Britain; William David Evans; Anthony Hammond; Thomas Colpitts Granger (1836). A collection of statutes connected with the general administration of the law: arranged according to the order of subjects. W. H. Bond. pp. 306–27. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ Edinburgh medical and surgical journal. A. and C. Black. 1824. p. 398.

- ^ Ireland; Butler, James Goddard; Ball, William (barrister.) (1765). The Statutes at Large, Passed in the Parliaments Held in Ireland: From the twenty-third year of George the Second, A.D. 1749, to the first year of George the Third, A.D. 1761 inclusive. Boulter Grierson. p. 852.

- ^ Gray, Samuel Frederick (1836). A supplement to the Pharmacopœia and treatise on pharmacology in general: including not only the drugs and preparations used by practitioners of medicine, but also most of those employed in the chemical arts : together with a collection of the most useful medical formulæ ... Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman. p. 516. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "A Translation of the Pharmacopoeia of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 1836.: With ..." S. Highley, 32, Fleet Street. 1837.

- ^ The Pharmacopoeia of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Adam and Charles Black and Bell and Bradfute. 1839. pp. xiii–xiv.

- ^ Royal College of Physicians of Dublin; Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (1850). The pharmacopœia of the King and queen's college of physicians in Ireland. Hodges and Smith. p. xxii. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Great Britain (1858). A collection of the public general statutes passed in the ... year of the reign of ... Printed by G. W. Eyre and W. Spottiswoode, Printers to the Queen. p. 306.

- ^ Sears et al. 1928. Phil Trans A, 227:281.

- ^ Jerrard and McNeill, Dictionary of Scientific Units, second edition, Chapman and Hall; cites first appearance in print in Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers (G.B.) vol. 1, page 246 (1872).

- ^ The exact figure was 6.08 ft, but 6 ft was in use in practice. The commonly accepted definition of a fathom was always 6 feet. The conflict was inconsequential, as Admiralty nautical charts designated depths shallower than 5 fathoms in feet on older imperial charts. Today, all charts worldwide are metric, except for USA Hydrographic Office charts, which use feet for all depth ranges.

- ^ The nautical mile was not readily expressible in terms of any of the intermediate units, because it was derived from the circumference of the Earth (like the original metre).

- ^ "Appendix C: General Tables of Units of Measurements" (PDF). NIST. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ a b c "An Act for ascertaining and establishing Uniformity of Weights and Measures (17 June 1824)" (PDF). legislation.gov.uk. 17 June 1824. p. 639,640. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

Two such Gallons shall be a Peck, and Eight such Gallons shall be a Bushel, and Eight such Bushels a Quarter of Corn or other dry Goods, not measured by Heaped Measure.

. (The date of coming into effect was 1 May 1825). - ^ imperial gallon. Sizes.com. 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "The Weights and Measures (Equivalents for dealings with drugs) Regulations 1970". Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Information Sheet: 11: Balances, Weights and Measures" (PDF). Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ a b Zentz, Lorraine C. (2010). "Chapter 1: Fundamentals of Math – Apothecary System". Math for Pharmacy Technicians. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-7637-5961-2. OCLC 421360709. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ a b Boyer, Mary Jo (2009). "UNIT 2 Measurement Systems: The Apothecary System". Math for Nurses: A Pocket Guide to Dosage Calculation and Drug Preparation (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 108–9. ISBN 978-0-7817-6335-6. OCLC 181600928. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Royal College of Physicians of Dublin (1850). "Weights and Measures". The Pharmacopœia of the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland. Dublin: Hodges and Smith. p. xlvi. hdl:2027/mdp.39015069402942. OCLC 599509441.

- ^ a b c National Institute of Standards and Technology (October 2011). Butcher, Tina; Cook, Steve; Crown, Linda et al. eds. "Appendix C – General Tables of Units of Measurement" Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Specifications, Tolerances, and Other Technical Requirements for Weighing and Measuring Devices Archived 3 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. NIST Handbook. 44 (2012 ed.). Washington, D.C.: US Department of Commerce, Technology Administration, National Institute of Standards and Technology. ISSN 0271-4027 Archived 25 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. OCLC OCLC 58927093. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ a b Rowlett, Russ (13 September 2001). "F". How Many? A Dictionary of Units of Measurement. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. fluid dram or fluidram (fl dr). Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ Buchholz, Susan; Henke, Grace (2009). "Chapter 3: Metric, Apothecary, and Household Systems of Measurement – Table 3-1: Apothecary Abbreviations". Henke's Med-Math: Dosage Calculation, Preparation and Administration (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7817-7628-8. OCLC 181600929. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Pickar, Gloria D.; Swart, Beth; Graham, Hope; Swedish, Margaret (2012). "Appendix B: Apothecary System of Measurement – Apothecary Units of Measurement and Equivalents". Dosage Calculations (2nd Canadian ed.). Toronto: Nelson Education. p. 528. ISBN 978-0-17-650259-1. OCLC 693657704. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ United Kingdom; Department of Trade and Industry (1995). The Units of Measurement Regulations 1995. London: HMSO. Schedule: Relevant Imperial Units, Corresponding Metric Units and Metric Equivalents. ISBN 978-0-11-053334-6. OCLC 33237616. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Great Britain (1878). Statutes at large ... p. 308.

- ^ Chaney, Henry James (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 477–494, see page 480.

- ^ a b Great Britain (1855). A collection of public general statutes passed in the 18th and 19th years of the reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. pp. 273–75.

- ^ "The Units of Measurement Regulations 1994". legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ "Definition of stone in English from the Oxford dictionary". www.oxforddictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ "Bulk densities of some common food products". engineeringtoolbox.com. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020. The density of wheat is 0.770, and 291*0.770=224 kilograms (494 lb).

- ^ a b Weights and Measures Act Archived 16 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Wolfram-Alpha: Computational Knowledge Engine". Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ a b Kelly, Jon (21 December 2011). "Will British people ever think in metric?". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

...but today the British remain unique in Europe by holding onto imperial weights and measures. ...the persistent British preference for imperial over metric is particularly noteworthy...

- ^ "Height and width road signs to display metric and imperial". BBC. 8 November 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

New road signs showing height and width restrictions will use both metric and imperial measurements from March 2015....Road signs for bridges, tunnels and narrow roads can currently show measurements in just feet and inches or only metres. Some already display both.

- ^ "BusinessLink: Weights and measures: Rules for pubs, restaurants and cafes". Department for Business, Innovation & Skills. Archived from the original (online) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- ^ "Department for Transport statement on metric road signs" (online). BWMA. 12 July 2002. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- ^ "In praise of ... metric measurements". The Guardian. London. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ King, Max (15 February 2021). "Decimalisation: Britain's "new pence" turn 50 years old". MoneyWeek. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "BMI healthy weight calculator". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Dahlgreen, Will (20 June 2015). "Britain's metric muddle not changing any time soon". Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

even today [2015] some 18-24-year-olds still do not know how much they weigh in kilograms (60%) or how tall they are in metres and centimetres (54%).

- ^ "YouGov Survey Results" (PDF). 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Weights and measures: the law". gov.uk. 7 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Explanatory memorandum to The weights and measures (metrication amendments) regulations 2009" (PDF). Legislation.gov.uk. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2019. See paragraph 7.4.

- ^ "Gas meter readings and bill calculation". gov.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Velkar, Ashish (May 2018). "Rethinking Metrology, Nationalism and Development in India, 1833–1956" (PDF). Past & Present (239): 143–79. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtx064. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b Acharya, Anil Kumar. History of Decimalisation Movement in India, Auto-Print & Publicity House, 1958.

- ^ "CAP 68 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES ORDINANCE Sched 2 UNITS OF MEASUREMENT AND PERMITTED SYMBOLS OR ABBREVIATIONS OF UNITS OF MEASUREMENT LAWFUL FOR USE FOR TRADE". Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ "Weights and Measures Act: Canadian units of measure". Justice Canada. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ "11". Guide to Food Labelling and Advertising. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Archived from the original on 24 January 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ "Consumer Packaging and Labelling Regulations (C.R.C., c. 417)". Justice Canada, Legislative Services Branch. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Field Inspection Manual — Automatic Weighing Devices: Part 3, Section A: Abbreviations and Symbols Accepted in Canada". 2 February 2017. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "A Canadian compromise". CBC. 30 January 1985. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ^ "Les livres et les pieds, toujours présents (eng:The pounds and feet, always present)" (in French). 5 sur 5, Société Radio-Canada. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ^ "Imperial Measures - The Origins". BWMAOnline.com. British Weights and Measures Association. 15 February 2021. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ Rosen, Amy (23 February 2011). "Crepes worth savouring". National Post. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019 – via PressReader.com.

- ^ Rosen, Amy (2 February 2011). "Scoring brownie points". National Post. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019 – via PressReader.com.

- ^ McDowell, Adam (28 February 2011). "Drinking school". National Post.

- ^ "Home Hardware - Building Supplies - Building Materials - Fence Products". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ "Canada: Metric System". Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Allard, Marie (25 August 2015). "Système métrique: à quand le virage final?". LaPresse.ca (in French). Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Canada, Government of Canada, Natural Resources. "Fuel Consumption Ratings Search Tool - Conventional Vehicles". Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Canada, Government of Canada, Transportation Safety Board of (9 April 1999). "Railway Investigation Report R96W0171". Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Canadian Aviation Regulations". Langley Flying School. sec. "Altimeter Rules". Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ ""30 Years of the Metric System"". Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Human use of metric measures of length" Archived 9 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Dignan, J. R. E., & O'Shea, R. P. (1995). New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 24, 21–25.

- ^ "Republic of Ireland". www.railsigns.uk. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ "Network Statement 2022" (PDF). Irish Rail. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Full HRI Directives". Archived from the original on 4 May 2016.

- ^ Parliament of the Bahamas. "Weights and Measures Act 2006". Bahamas Bureau of Standards and Quality. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "National Metrology Act, Chapter 294, Revised Edition 2011" (PDF). Government of Belize. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "The World Factbook, Appendix G: Weights and Measures". Web Pages. Central Intelligence Agency. 2010. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Gyi, Ko Ko (18–24 July 2011). "Ditch the viss, govt urges traders". Business and Property. The Myanmar Times. Translated by Thit Lwin. Myanmar. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ Kohler, Nicholas (3 March 2014). "Metrication in Myanmar". Mizzima News. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Address by Agriculture Minister Gregory Bowen". The Ministry of Agriculture, Government of Grenada. 1 November 2004. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

The price of gasoline at the pumps was fixed at EC$7.50 per imperial gallon...

- ^ "FAQ". MoF.gov.bz. Belize Ministry of Finance. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

• Kerosene per US Gallon (per Imperial gallon) • Gasoline (Regular)(per imperial Gallon) • Gasoline (Premium) (per Imperial Gallon) • Diesel (per Imperial Gallon)

- ^ "The High Commission Antigua and Barbuda". Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ Metschies, Gerhard P. (6 September 2005). "International Fuel Prices 2005" (PDF). International-Fuel-Prices.com. German Technical Cooperation. p. 96. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ "Introduction of the Metric System and the Price of Petroleum Products". Sierra Leone Embassy in the United States. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Minister Lovell Addresses Metric Conversions". CARIBARENA Antigua. 18 October 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "DEWA adopts cubic metre as the unit to measure water consumption instead of the imperial gallon starting from March 2025 billing cycle". 9 February 2025. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

General sources

[edit]- Appendices B and C of NIST Handbook 44

- Thompson, A.; Taylor, Barry N. (5 October 2010). "The NIST guide for the use of the international system of units". NIST. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2012. Also available as a PDF file.

- 6 George IV chapter 12, 1825 (statute)

External links

[edit]- British Weights And Measures Association

- Canada Weights and Measures Act 1970-71-72

- General table of units of measure – NIST – pdf

- How Many? A Dictionary of Units of Measurement Archived 10 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Statutory Instrument 1995 No. 1804 Units of Measurement Regulations 1995

Imperial units

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Development

Pre-1824 English Units

The English customary units predating the 1824 standardization emerged organically from Anglo-Saxon practices, drawing on empirical approximations tied to human anatomy and natural objects to meet the demands of local trade, agriculture, and land division. The inch originated as the approximate width of a thumb or the length of three barleycorns laid end-to-end, reflecting a practical subdivision of larger measures derived from everyday materials like barley grains used in farming.[8][9] The foot approximated the length of an adult human foot, varying regionally from about 9.75 to 19 inches before broader codification, while the yard stemmed from an arm's span or stride, often specified as the distance from nose to outstretched thumb tip.[8][10] These units incorporated Anglo-Saxon influences, such as the ynce based on the barleycorn, with the foot comprising 36 barleycorns and the yard 108, facilitating consistent yet flexible measurements for sowing seeds, plowing fields, and bartering goods without reliance on abstract or imported systems.[10] Early royal interventions aimed to mitigate variations through verifiable prototypes. King Henry I (reigned 1100–1135) decreed the yard as the girth of his own arm, establishing a personal standard close to the later 36-inch measure, while tying it to 108 barleycorns for reproducibility in cloth trading and construction.[10][9] In 1324, Edward II formalized the inch explicitly as three barleycorns end-to-end, the foot as 12 inches, and the yard as three feet, using an iron rod prototype to anchor linear measures amid growing commercial exchanges.[8][9] Larger units like the rod (5.5 yards), used for furrow spacing in plowing, and the acre (one chain by one furlong, or 4 rods by 40 rods) directly supported agricultural productivity by aligning with the physical scale of oxen teams and field layouts.[10][9] The Winchester standards, rooted in 10th-century Anglo-Saxon precedents, served as influential national benchmarks for capacity and weight into the 16th century. King Edgar (reigned 959–975) mandated a standard bushel preserved at Winchester, positioning the city as a repository for measures like the gallon derived from dry goods volumes.[11] By the late 15th century, Henry VII (reigned 1485–1509) reaffirmed these customary standards in 1497, issuing brass prototypes such as a bushel of 2,124 cubic inches and a gallon of 272.5 cubic inches, distributed for use in markets to approximate fair exchange in grain and wool.[11] These efforts built on earlier wool trade weights under Edward III (14th century), who standardized the avoirdupois pound at 7,000 grains for bulk commodities, distinct from the troy pound's 5,760 grains for precious metals.[10][11] Despite these prototypes, significant regional inconsistencies persisted, underscoring the units' adaptive, bottom-up evolution rather than rigid uniformity. Feet and yards varied by locality due to differing body proportions or local rods, while miles ranged up to 2,880 yards in parts of England and 2,240 in Ireland, complicating long-distance surveying.[8] Furlongs adjusted to soil types for plowing efficiency, and local market weights deviated from Winchester brass standards, as seen in Elizabethan revisions under Elizabeth I (1588) to correct inaccuracies in Henry VII's copies.[8][11] Nonetheless, this pragmatic variability enabled robust economic activity, with units scaled to human and animal capabilities supporting Britain's expansion in agriculture—via acres for enclosure and yields—and commerce, where avoirdupois pounds standardized bulk trade routes without theoretical impositions.[10][9]Standardization via the 1824 Weights and Measures Act

The Weights and Measures Act 1824, enacted on 17 June 1824, established a unified system of weights and measures across the United Kingdom to promote commerce by replacing disparate local and historical standards with imperial prototypes.[1] The Act mandated the creation of brass standards for length and mass, defining the imperial yard as the distance between two transverse lines etched into a bronze bar maintained at the Exchequer in London, constructed and verified through empirical comparison to prior national artifacts.[12] Similarly, the avoirdupois pound was standardized as a platinum cylinder weighing the equivalent of the existing parliamentary standard, later precisely quantified as 0.45359237 kilograms through subsequent metrological tracing to the original artifact.[13] These definitions prioritized tangible, verifiable physical objects over abstract decimal rationales, ensuring continuity with established trade practices while enabling reproducible precision.[14] The Act also rationalized volume measures by introducing the imperial gallon as the volume occupied by ten avoirdupois pounds of distilled water at 62°F, abolishing variants such as the wine, ale, and corn gallons previously in use.[1] It restricted the troy pound and apothecaries' system to specialized applications like precious metals and pharmaceuticals, designating avoirdupois weights for general commercial transactions to eliminate confusion in bulk goods.[13] Implementation occurred in phases, with prototype standards completed and tested by 1825 for distribution to verification offices, and mandatory use enforced from 1 January 1826, though local standards required gradual calibration against imperial copies by inspectors.[15] This timeline allowed adaptation without immediate disruption, with full abolition of non-conforming measures by 1835 in some jurisdictions. The legislative push reflected demands from the Industrial Revolution for consistent measures in expanding manufacturing and interstate trade, where variability in local units had previously hindered accurate contracts and machinery calibration.[16] By codifying empirical standards derived from long-used benchmarks rather than imposing a wholesale decimal overhaul, the Act facilitated causal reliability in economic exchanges, supporting Britain's position as a global trading power without the disruptions associated with revolutionary metric proposals.[14]Divergence from US Customary Units

The divergence between imperial units and US customary units arose following American independence, as the United States retained definitions rooted in pre-1824 English measures while Britain enacted the Weights and Measures Act of 1824, which standardized and redefined units under the imperial system.[5][17] This act abolished earlier parliamentary standards dating to the 14th century and established new imperial prototypes, such as the imperial gallon defined as the volume occupied by 10 pounds avoirdupois of water at 62°F, equivalent to 277.4194 cubic inches.[13] In contrast, the US adhered to the Queen Anne's wine gallon of 231 cubic inches for liquid measure, a definition codified in British law around 1707 but not revised in the 1824 act's overhaul, resulting in the imperial gallon being approximately 20% larger than its US counterpart.[17][18] The US Congress's Act of July 28, 1866 (often referencing earlier 1836 efforts to align standards), partially harmonized length and mass units by defining the yard and avoirdupois pound to match British prototypes from the 1758 standards, which predated but closely resembled imperial definitions.[18][19] However, volume measures like the gallon and bushel (US at 2150.42 cubic inches versus imperial at 2218.192 cubic inches) remained unchanged due to entrenched commercial practices and reluctance to adopt post-independence British revisions, reflecting path-dependent evolution rather than deliberate rejection of functionality.[17] This selective alignment preserved compatibility in avoirdupois weight and linear measures while perpetuating discrepancies in capacity, as US lawmakers prioritized domestic consistency over full imperial adoption.[5] Empirical applications in trade, agriculture, and engineering demonstrate both systems' adequacy for practical tasks within their respective economies, with no evidence of inherent superiority driving the split; differences stem from historical timing and institutional inertia rather than causal flaws in measurement logic.[13] For instance, the US bushel's fixed volume supported consistent grain transactions without needing imperial adjustments, underscoring how localized standards sufficed amid 19th-century industrialization.[18]Core Definitions and Standards

Legal and Physical Standards

The legal standards for imperial units were established through physical prototypes maintained under controlled conditions to ensure reproducibility and stability in metrology. The Imperial Standard Yard, adopted via the Weights and Measures Act 1824 and refined in subsequent legislation, was embodied in a bronze bar with transverse lines engraved 38 inches apart, defining the unit as the distance between these lines at 62°F (16.66°C) when supported horizontally on two rollers.[12] Between 1845 and 1855, multiple copies of this standard were crafted for verification and distribution, with the primary artifact preserved by the UK government to serve as the authoritative reference for length measurements.[12] While the Weights and Measures Act 1855 introduced equivalents linking imperial units to metric counterparts for facilitating international trade—such as approximating 1 meter as 39.37 inches—these served as secondary verification tools rather than redefinitions, preserving the primacy of the imperial prototypes.[20] The Act legalized parliamentary copies of the standards and emphasized direct traceability to the original artifacts, underscoring a system grounded in empirical physical comparison over abstract derivations. This approach provided causal reliability, as discrepancies could be resolved through meticulous replication and calibration against the master prototypes housed in secure vaults.[19] Recognizing minor variations between national prototypes due to material wear and manufacturing tolerances, representatives from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa reached the 1959 International Yard and Pound Agreement, defining the yard exactly as 0.9144 meters based on interferometric measurements against the wavelength of krypton-86 light.[21] This calibration, conducted at institutions like the UK's National Physical Laboratory, maintained continuity with historical artifacts while enhancing precision and uniformity across Commonwealth and US customary systems.[22] For mass, analogous prototypes such as the Imperial Standard Pound—a platinum cylinder—underwent similar verification processes, with the agreement setting the avoirdupois pound at exactly 0.45359237 kilograms, derived from empirical assessments of prototype stability.[23] These standards ensured legal enforceability in trade and science by prioritizing reproducible physical references, calibrated through direct metrological techniques rather than solely theoretical constructs.Equivalents and Conversions to Metric

The imperial system's fundamental units of length and mass were standardized relative to metric units via the 1959 International Yard and Pound Agreement between the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, defining 1 yard as exactly 0.9144 meters and 1 avoirdupois pound as exactly 0.45359237 kilograms.[24][25] These exact ratios, derived from prior empirical calibrations against metric prototypes, eliminated discrepancies in international trade and science while preserving imperial definitions.[26] Derived length units follow directly: 1 foot equals 0.3048 meters exactly, and 1 inch equals 25.4 millimeters exactly.[26] For volume, the imperial gallon—originally the space occupied by 10 pounds of water at maximum density—is codified as exactly 4.54609 liters in British legislation, with the imperial pint (1/8 gallon) thus equaling exactly 568.261 milliliters.[27] These values reflect post-1824 standardizations adjusted for metric alignment in the 20th century, though they diverge from U.S. customary equivalents (e.g., U.S. liquid pint ≈ 473.176 milliliters), introducing conversion variances in transatlantic contexts.[26] Such precise but non-decimal factors enable verifiable calculations, underscoring imperial units' empirical anchoring in physical constants like water density rather than arbitrary base-10 scaling.| Imperial Unit | Metric Equivalent | Conversion Factor (Exact) |

|---|---|---|

| Inch | Millimeter | 1 in = 25.4 mm |

| Foot | Meter | 1 ft = 0.3048 m |

| Yard | Meter | 1 yd = 0.9144 m |

| Pound (avoirdupois) | Kilogram | 1 lb = 0.45359237 kg |

| Imperial Gallon | Liter | 1 gal = 4.54609 L |

| Imperial Pint | Milliliter | 1 pt = 568.261 mL |

Primary Units of Measurement

Length Units

The imperial system's length units derive from pre-modern English measures rooted in human body proportions, such as the foot approximating the length of an adult foot and the inch the width of a thumb or three barleycorns laid end to end, which historically aided rough estimation in construction and daily tasks without computational aids.[28][29] These empirical bases evolved into a standardized hierarchy via the Weights and Measures Act 1824, which defined the yard as the distance at 62°F between two transverse lines on a bronze bar prototype held by the Exchequer, with the inch as exactly 1/36 of this yard and the foot as 1/3 yard, thereby resolving medieval inconsistencies like varying local feet or miles.[30] Larger units include the rod (also perch or pole), standardized at 5.5 yards for land division and surveying, reflecting agricultural furrow lengths.[31][32] The statute mile, fixed at 1,760 yards (or 5,280 feet), originated from Roman influences but was codified in 1593 under Elizabeth I as eight furlongs, distinguishing it from shorter historical miles and supporting consistent long-distance applications.[33][34] In 1959, the International Yard and Pound Agreement redefined the yard as exactly 0.9144 meters, establishing the inch at precisely 25.4 millimeters while maintaining internal ratios like 12 inches per foot and 3 feet per yard for practical decimal-free divisibility in engineering.[35][25]Area and Volume Units

Imperial area units derive primarily from squaring primary length measures, yielding square inches (sq in), square feet (sq ft), square yards (sq yd), and square miles (sq mi), which scale for plotting fields, buildings, and territories. Traditional subdivisions like the acre, rood, and perch emerged from medieval English agrarian practices, where land was apportioned for plowing with oxen teams—a single acre represented roughly the daily tillable extent for such a yoke, prioritizing practical yields over decimal uniformity. The acre equals exactly 4,840 square yards or 43,560 square feet, standardized in the British Imperial system to maintain continuity with pre-1824 customs while ensuring reproducibility for deeds and taxation.[36][37] A rood comprises one-quarter acre or 1,210 square yards, subdivided into 40 perches (also called poles or rods), each perch spanning 30.25 square yards—dimensions tied to the linear perch of 16.5 feet, facilitating chain-based surveying of irregular plots.[36][38] Volume measures analogously derive from cubing length units, such as cubic inches (cu in) and cubic feet (cu ft), but practical trade standardized the gallon as the base for liquids and bulk dry goods, reflecting capacities of barrels and carts for commodities like ale, wine, and grain. The imperial gallon, fixed at exactly 4.54609 litres since 1824, unified prior fluid and dry variants—eliminating discrepancies where wine gallons (≈4.546 L) differed slightly from corn gallons—to streamline port and market transactions, as volume directly influenced storage and spoilage risks in non-refrigerated eras.[39] The bushel, tailored for dry agricultural hauls, holds 8 gallons or 2,218.192 cubic inches (≈36.37 L), its size calibrated to typical harvest yields and wagon loads rather than weight, accommodating variable densities in crops like wheat or peas without constant re-weighing.[40] This fluid-dry convergence, absent in U.S. customary systems, prioritized causal efficiency in bulk handling over strict separation, as empirical densities often approximated water's for valuation.[41] These units endure in real estate, particularly for land parcels, owing to entrenched historical surveys and legal records predating metric adoption; in the UK, while Ordnance Survey maps employ meters, acres dominate sales listings and valuations for farms exceeding a hectare, preserving investor familiarity amid partial metrication since 1965.[42] In the U.S., acres similarly govern rural and suburban conveyances, with over 90% of non-urban listings citing them, as converting vast archives would impose disproportionate costs without evident productivity gains in appraisal or subdivision.[43]Mass and Force Units

The avoirdupois system forms the basis for imperial mass measurements in general commerce, with the pound (lb) as the fundamental unit, defined exactly as 0.45359237 kilograms since the 1959 international agreement.[24] This pound subdivides into 16 ounces (oz), yielding an avoirdupois ounce of exactly 28.349523125 grams, employed for commodities like foodstuffs and bulk goods.[24] Multiples include the stone (st), equivalent to 14 pounds or 6.35029318 kilograms, traditionally used for weighing produce, livestock, and human body mass in the United Kingdom.[44] For precious metals and bullion, the imperial system retains the troy pound, comprising 12 troy ounces rather than 16, totaling approximately 373.241722 grams, to ensure precision in transactions where small mass differences impact value.[45] This distinction persists in global markets for gold and silver, prioritizing empirical consistency in assaying over alignment with avoirdupois subdivisions. Imperial force units address gravitational contexts directly through the pound-force (lbf), defined as the gravitational force on one avoirdupois pound-mass under standard acceleration of 32.17405 feet per second squared, equating to approximately 4.448221615 newtons.[46] This empirical tie to observed Earth gravity facilitates engineering calculations in fields like structural design and propulsion, where weight measurements in pounds inherently reflect force without requiring separate multiplication by an abstract gravitational constant, as in the SI newton derived from kilogram-mass times meters per second squared.[46] In practice, the dual use of "pound" for both mass and weight underscores causal realism in everyday and industrial applications, where local gravity variations are minor compared to measurement precision.Specialized and Variant Units

Apothecaries' and Troy Systems

The apothecaries' system comprised specialized Imperial units for pharmaceutical compounding, employing troy-based weights and fluid measures optimized for precise dosing of medicines. Originating from practices documented as early as 1270 in Europe, it divided the pound into 12 ounces to enable fractional divisions—such as thirds (4 ounces) or quarters (3 ounces)—better suited to medicinal recipes than the avoirdupois system's 16-ounce pound for bulk commodities.[47] Key weight units included the grain (basis for all troy-derived measures, equivalent to 64.79891 milligrams), scruple (20 grains), dram (60 grains), and ounce (480 grains), with the full troy pound weighing 5,760 grains or 373.241722 grams—lighter overall than the avoirdupois pound of 7,000 grains but with a heavier individual ounce at 31.1034768 grams.[48][44] Fluid measures followed suit, with the apothecaries' fluid ounce defined as 28.4130625 milliliters (one-twentieth of the Imperial pint), subdivided into 8 fluid drams (3.551 ml each) and further into 480 minims for fine liquid dilutions in elixirs and tinctures.[49][50] The troy system, integral to apothecaries' weights, specialized in precious metals assaying, retaining the same 12-ounce pound structure for accuracy in valuing gold and silver, where even minor discrepancies impact economic assessments.[51] Unlike avoirdupois, this configuration prioritized divisibility by 3 and 4 over binary halvings, yielding empirical advantages in subdividing small quantities without excessive remainders, as evidenced in historical compounding where drams and scruples aligned with therapeutic fractions.[52] Though largely supplanted by metric standards in contemporary pharmacy, these systems preserve value in legacy formulations and metallurgical assays, where troy units ensure continuity in empirical verification against historical benchmarks.[53]Nautical and Surveyor Variants

In nautical measurement, the imperial nautical mile was standardized in the United Kingdom as exactly 6080 feet until the international definition of 1852 meters was adopted in 1970.[8] This length derived from empirical approximations of one minute of latitude on the Earth's meridian, facilitating dead reckoning and celestial navigation by aligning distance with angular measurements in spherical trigonometry.[54] The cable, a subdivision equivalent to one-tenth of the nautical mile, measured 608 feet, corresponding historically to the length of anchor cables and used for shorter-range estimations in maritime operations.[8] These adaptations reflected causal necessities of navigation on a curved planetary surface, where distances along meridians or parallels require accounting for geodesic variance rather than planar assumptions; the nautical mile's basis in arc minutes allowed direct conversion from sextant observations or chronometer-derived longitude to tractable distances without constant metric reconfiguration.[55] For land surveying, Gunter's chain—developed by Edmund Gunter in 1620—measured 66 feet or 22 yards, comprising 100 iron links for portability and precision in chaining terrain.[56] In the United States, this chain became the standard for public land surveys under the Public Land Survey System established by the Land Ordinance of 1785, enabling systematic rectangular township grids where 80 chains equaled one mile and ten square chains equaled one acre (43,560 square feet), simplifying computational verification of parcel areas against legal entitlements.[56] The unit's dimensions were selected to integrate seamlessly with imperial acreage computations, minimizing fractional errors in irregular topographies where empirical chaining accounted for slopes and obstructions.[57]Practical Advantages and Empirical Utility

Human-Scale Intuitiveness

Imperial units originated from anthropometric references tied to the human body, enabling intuitive estimation in daily activities without measurement tools. The foot derives from the approximate length of an adult human foot, standardized historically to about 12 inches, while the inch traces to the width of a thumb or digit, divided as one-twelfth of the foot for finer granularity.[9] Similarly, the hand unit equals four inches, matching the breadth of an open hand, and the pace approximates a double-step distance, roughly five feet. These bases allowed pre-industrial societies to gauge lengths, heights, and spans by direct bodily comparison, fostering a visceral sense of scale aligned with human proportions.[31] This anthropometric foundation supports rapid mental approximations for common objects, such as estimating a person's height in feet by visualizing stacked body segments or assessing room widths in yards via arm spans. In manual contexts like agriculture or construction, such units permitted quick assessments—e.g., a field's length in paces for plowing—without instruments, embedding measurement into physical intuition. Analyses of everyday cognition indicate that units scaled to human dimensions, like feet over smaller increments, better match familiar object sizes for approximation tasks.[58] Fractional divisions in imperial units, particularly binary (halves, quarters, eighths) and duodecimal (thirds, sixths), offer practical utility in trades requiring iterative subdivision without decimal conversions. For instance, dividing a foot into 12 inches facilitates equal parts for materials like lumber or pipe fittings, where halves and quarters align with simple tools like saws or calipers. This structure simplifies on-site adjustments in carpentry and plumbing, reducing cognitive load compared to decimal approximations that may demand calculators for non-terminating fractions.[59] Such divisions reflect empirical adaptations from artisanal practices, where repeated halving of lengths or areas—common in woodworking—yields precise fits through powers of two.[60]Efficacy in Engineering and Construction

The Apollo program, which achieved the first manned lunar landings between 1969 and 1972, relied predominantly on U.S. customary units such as feet, inches, pounds, and nautical miles for design, calculations, and operations, enabling precise engineering without documented unit conversion failures akin to those in later metric-involved missions.[61][62] Similarly, the Hoover Dam, constructed from 1931 to 1936 and standing 726 feet high with a base 660 feet thick, was engineered and built using imperial measurements like feet and inches, contributing to its status as a reliable infrastructure project that has operated without structural failures attributable to measurement inconsistencies.[63][64] In machining and iterative construction processes, imperial units facilitate the use of binary fractions (e.g., halves, quarters, sixteenths of an inch), which align with common tooling divisions and minimize rounding errors during repeated subdivisions, as opposed to decimal metric approximations that can compound in multi-step fabrication.[60][65] This fractional tolerance supports high-precision work in fields like aerospace and civil engineering, where imperial's divisibility by 2, 3, and 4 reduces the need for calculators in on-site adjustments, enhancing efficiency in legacy U.S. manufacturing.[66] Efforts to switch to metric in engineering contexts have incurred significant costs, exemplified by NASA's 1999 Mars Climate Orbiter loss, where a failure to convert imperial pound-force seconds to metric newton-seconds resulted in a $327 million mission failure due to mismatched units between contractors.[67][68] Broader analyses indicate that full metric conversion in U.S. industries could require billions in retraining, tooling redesign, and error mitigation, often outweighing benefits in non-research applications where imperial systems have proven stable over decades.[69][70]Criticisms and Inherent Limitations

Arithmetic Inconsistencies

The imperial system's mixed radix structure, such as 12 inches per foot and 16 ounces per avoirdupois pound, introduces arithmetic inconsistencies by requiring non-decimal conversions that demand memorization of irregular factors rather than simple shifts in decimal place.[71] The foot's base-12 division originated in ancient Roman and medieval English practices, where 12's multiple divisors (1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12) supported fractional halving, thirding, and quartering in trade and construction without decimal tools.[5] Similarly, the 16-ounce pound derived from 13th-century French avoirdupois weights imported to England, enabling binary subdivisions suited to weighing commodities like grain.[72] These bases, while empirically tuned for everyday divisibility, hinder scalability across units—e.g., converting yards to inches yields 36 (not a power of 10)—complicating aggregation in bookkeeping or surveying compared to uniform decimal progression.[71] Volume units exemplify historical inconsistencies from pre-standardization variability. Multiple gallon definitions coexisted in Britain before 1824, including the wine gallon (231 cubic inches) and ale gallon; the Weights and Measures Act of 1824 unified the imperial gallon at exactly 10 pounds of water at 62°F (4.54609 liters), resolving domestic discrepancies through statutory prototypes.[1] In the United States, independence preserved the smaller Queen Anne wine gallon of 231 cubic inches (3.78541 liters), creating a persistent transatlantic mismatch equivalent to about 17% volume difference.[5] This divergence, a relic of colonial autonomy rather than deliberate imperial design, necessitated separate conversion tables but was mitigated by codified standards rather than systemic overhaul. Such inconsistencies, rooted in accreted practical subdivisions rather than arbitrary chaos, have been managed in imperial contexts via conversion aids like printed tables and mechanical calculators, predating widespread decimal adoption.[71] Empirical records from Britain's industrial era show no documented systemic arithmetic breakdowns tied to unit radices alone, as practitioners adapted through domain-specific training and tools, underscoring that the flaws reflect historical pragmatism over engineered uniformity.[15]Conflicts with Decimal-Based Science