Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Interwar Britain

View on Wikipedia

| Interwar Britain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 November 1918 – 3 September 1939 | |||

| |||

| Monarchs | |||

| Leaders | |||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

| English history |

|---|

| Timeline |

In the United Kingdom, the interwar period (1918–1939) entered a period of relative stability after the Partition of Ireland, although it was also characterised by economic stagnation. In politics, the Liberal Party collapsed and the Labour Party became the main challenger to the dominant Conservative Party throughout the period. The Great Depression affected Britain less severely economically and politically than other major nations, although some areas still suffered from severe long-term unemployment and hardship, especially mining districts and in Scotland and North West England.

Historian Arthur Marwick sees a radical transformation of British society resulting from the Great War, a deluge that swept away many old attitudes and brought in a more egalitarian society. He sees the famous literary pessimism of the 1920s as misplaced, arguing there were major positive long-term consequences of the war for British society. He points to an energised self-consciousness among workers that quickly built up the Labour Party, the coming of partial women's suffrage, and an acceleration of social reform and state control of the economy. He sees a decline of deference toward the aristocracy and established authority in general, and the weakening among youth of traditional restraints on individual moral behaviour. The chaperone faded away; village chemists sold contraceptives.[1] Marwick says that class distinctions softened, national cohesion increased, and British society became more equal during the period.[2]

Political history

[edit]Lloyd George Coalition government: 1918–1922

[edit]

The 1918 general election produced a landslide victory for the coalition government headed by David Lloyd George, who promised "a fit country for heroes to live in".[3] The majority of coalition MPs were Conservative and the election also saw the decline of H. H. Asquith's Liberals and the rise of the Labour Party.[3]

Wartime regulations such as state direction of industry, price controls, the control of raw materials and foreign trade were abolished, and trade unions resurrected restrictive practices.[4] However, food rationing remained until 1921. Prices increased twice as fast during 1919 than they had during the war and this was followed by wage increases.[5] High taxation was regarded as the cause of wasteful government expenditure and in 1921 an Anti-Waste movement was launched, which attracted considerable support for its attacks on "wasteful" public spending.[6] The government appointed Sir Eric Geddes head of the committee on government expenditure and in February 1922 its report was published, which recommended spending cuts on the armed forces and social services.[7] The "Geddes Axe" on government spending and the end of the postwar economic boom in 1922 had made it impossible to fulfil the promises of reconstruction and "homes for heroes".[8]

Enlarging democracy

[edit]The Representation of the People Act 1918 finally gave Britain universal manhood suffrage at age 21, with no property qualifications. Even more dramatically it opened up woman suffrage for most women over the age of 30. In 1928, all women were covered on the same terms as men.[9] With the emergence of revolutionary forces, most notably in Bolshevik Russia and Socialist Germany, but also in Hungary, Italy and elsewhere, revolution to overthrow established elites and aristocracies was in the air. The Labour Party largely controlled working-class politics, and it strongly supported the government in London and opposed violent revolution. Conservatives were especially worried about "Red Clydeside" in industrial Scotland. Their fears were misplaced, for there was no organised attempt at any revolution.

Nevertheless, there were concerns about republicanism. The king and his top advisers were deeply concerned about the republican threat to the British monarchy, so much so that it was a factor in the king's decision not to rescue his cousin, the overthrown Tsar Nicholas II of Russia.[10] Nervous conservatives associated republicanism with the rise of socialism and the growing labour movement. Their concerns, although exaggerated, resulted in a redesign of the monarchy's social role to be more inclusive of the working class and its representatives, a dramatic change for George, who was most comfortable with naval officers and landed gentry. In fact the socialists by 1911 no longer believed in their anti-monarchy slogans and took a wait-and-see attitude toward George V. They were ready to come to terms with the monarchy if it took the first step.[11] During the war George took that step; he made nearly 300 visits to shipyards and munitions factories, chatting with and congratulating ordinary workers on their hard work for the war effort.[12] He adopted a more democratic stance that crossed class lines and brought the monarchy closer to the public. The king also cultivated friendly relations with leading Labour party politicians and trade union officials. George V's abandonment of social aloofness conditioned the royal family's behaviour and enhanced its popularity during the economic crises of the 1920s and for over two generations thereafter. For example, in 1924 the king proved willing, in the absence of a clear majority for any one of the three parties, to replace Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin with Ramsay MacDonald, the first Labour Party prime minister. King George's tactful and understanding reception of the MacDonald government allayed the suspicions of the party's supporters throughout the nation.[13]

Ireland

[edit]An armed insurrection by Irish republicans known as the Easter Rising took place in Dublin during Easter Week, 1916. It was quickly suppressed by the Army. The government responded with harsh repression, 2,000 arrests, and quick execution of 15 leaders. The Catholic Irish then underwent a dramatic change of mood, and shifted to demand vengeance and independence.[14] In 1917 David Lloyd George called the 1917–18 Irish Convention in an attempt to settle the outstanding Home Rule for Ireland issue. It had little support. The upsurge in republican sympathies in Ireland following the Easter Rising coupled with Lloyd George's disastrous attempt to extend conscription to Ireland in April 1918 led to the wipeout of the old Irish Home Rule Party at the December 1918 election. They had supported the British war effort and were then displaced by Sinn Féin, which had mobilised grass-roots opposition to helping the British rule.[15] Sinn Féin MPs did not take up their seats in the British Parliament, instead setting up their own new parliament in Dublin, and immediately declared an Irish Republic.[16]

British policy was confused and contradictory, as the cabinet could not decide on war or peace, sending in enough force to commit atrocities that angered Catholics in Ireland and America, and Liberals in Britain, but not enough to suppress the rebels outside the cities. Lloyd George waxed hot and cold, denouncing murderers one day, but eventually negotiating with them. He sent in 40,000 soldiers as well as newly formed para-military units—the "Black and Tans" and the Auxiliaries—to reinforce the professional police (the Royal Irish Constabulary). British firepower prevailed in the cities forcing the Irish Republican Army (IRA) (the paramilitary force of Sinn Féin) into hiding. However, the IRA controlled much of the countryside and set up an alternative local government.[17] The British units were poorly coordinated while Michael Collins designed a highly effective organisation for the IRA that used informers to destroy the British intelligence system by assassinating its leadership.[18] Although it was called "Irish War of Independence" historians generally agree that it was quite unlike the later Irish Civil War that was fought in 1922–23 between the forces of Collins and Éamon de Valera. The 1919–21 clash "was no war in any conventional sense of the term, but a highly contingent, very small-scale and low-intensity conflict in which assassination was as important as ambush or fixed battle."[19]

Lloyd George finally solved the crisis with the Government of Ireland Act 1920 which partitioned Ireland into Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland in May 1921. Sinn Féin won control of the south and agreed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921 with Irish leaders. Collins took power when de Valera refused to sign and led a breakaway faction.[20] Under the treaty southern Ireland seceded in 1922 to form the Irish Free State. Meanwhile, the Unionists under Edward Carson controlled Ulster and Northern Ireland remained loyal to London.[21][22] By 1922 the Irish situation had stabilised, and no longer played a major role in British politics. Nevertheless, disputes sputtered for decades regarding the exact relationship to the monarchy, a trade war in the 1930s, and British use of naval ports. The Irish Free State cut many of its ties to Britain in 1937. As the Republic of Ireland it was one of a handful of neutral European nations during the Second World War.[23]

Period of instability: 1922–1924

[edit]

The Lloyd George ministry fell apart in 1922 after Conservative MPs voted to end their membership of the Coalition at the Carlton Club meeting of 19 October.[24] Bonar Law became prime minister of a Conservative government and won the general election with a manifesto that promised spending cuts and a non-interventionist foreign policy.[25] However, he resigned in May 1923 because of ill health and was replaced by Stanley Baldwin. Baldwin, as leader of the Conservative Party (1923–37) and as Prime Minister (in 1923–24, 1924–29 and 1935–37), dominated British politics.[26] His mixture of strong social reforms and steady government proved a powerful election combination, with the result that the Conservatives governed Britain either by themselves or as the leading component of the National Government. In the general election of 1935 Baldwin's was the last government to win over 50% of the vote. Baldwin's political strategy was to polarise the electorate so that voters would choose between the Conservatives on the right and the Labour Party on the left, squeezing out the Liberals in the middle.[27] The polarisation did take place and while the Liberals remained active under Lloyd George, they won few seats. Baldwin's reputation soared in the 1920s and 1930s, but crashed after 1940 as he was blamed for the appeasement policies toward Germany, and as Churchill was made the Conservative icon by his admirers. Since the 1970s Baldwin's reputation has recovered somewhat.[28] Ross McKibbin finds that the political culture of the interwar period was built around an anti-socialist middle class, supported by the Conservative leaders, especially Baldwin.[29]

Having won an election just the year before, Baldwin's Conservative party had a comfortable majority in the Commons and could have waited another four years, but the government was concerned about unemployment. As Bonar Law had pledged that there would be no change in the country's fiscal system without a second general election, Baldwin felt the need to receive a new mandate from the people to introduce tariffs, which he hoped would secure the home market for domestic manufacturers and reduce unemployment.[30] Oxford historian (and Conservative MP) J. A. R. Marriott depicts the gloomy national mood:

The times were still out of joint. Mr. Baldwin had indeed succeeded in negotiating (January 1923) a settlement of the British debt to the United States, but on terms which involved an annual payment of £34 million, at the existing rate of exchange. The French remained in the Ruhr. Peace had not yet been made with Turkey; unemployment was a standing menace to national recovery; there was continued unrest among the wage-earners, and a significant strike among farm labourers in Norfolk. Confronted by these difficulties, convinced that economic conditions in England called for a drastic change in fiscal policy, and urged thereto by the Imperial Conference of 1923, Mr. Baldwin decided to ask the country for a mandate for Preference and Protection.[31][32]

The result of the election, however, backfired on Baldwin, who lost a host of seats to the pro-free trade Labour and the Liberal parties.[33][34] The Conservatives remained the largest party with 258 seats, compared to Labour's 191 seats and 158 for the Liberals.[35] Baldwin remained prime minister until the government lost a vote of confidence in the House of Commons on 21 January 1924, when Labour and the Liberals combined to vote against the government. The next day Baldwin resigned the premiership and Ramsay MacDonald formed the first Labour government.[36]

First Labour government: 1924

[edit]

Although the Labour government lacked a majority, it passed the Housing (Financial Provisions) Act 1924, which increased government subsidies to local authorities to build municipal housing for rent for low paid workers.[37][38] The Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Snowden balanced the budget through cuts in expenditure and taxation.[39][37]

The Labour government officially recognised the Soviet Union on 1 February 1924 and engaged in negotiations with the Soviets to settle outstanding issues, such as the payment of Russia's pre-revolutionary debts to Britain. However, the Soviets would only agree if they received a loan guaranteed by the British government.[40] The government signed two treaties with the Soviets on 8 August; the first was a commercial treaty which granted most favoured nation status and the second was a general treaty, which left the settlement of pre-revolutionary debts and the government loan to be negotiated at a later date.[41] The Conservatives and Liberals denounced the treaties, especially the government loan, which David Lloyd George called "a fake...a thoroughly grotesque agreement".[42]

On 5 August the police raided the offices of Workers' Weekly, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Great Britain, for publishing a seditious article by J. R. Campbell, who was arrested under the Incitement to Mutiny Act 1797.[43][44] The Labour government dropped the prosecution of the Campbell Case on 13 August, which was criticised by Conservatives and Liberals as political interference. On 8 October the Conservatives voted for the Liberal motion that called for a committee of enquiry on the government's decision, which was carried by 364 votes to 198.[45][46] Parliament was dissolved the next day and a general election was called. On 25 October, four days before polling day, the Daily Mail published the "Zinoviev letter", which purported to be from Grigory Zinoviev, the Soviet politician and head of the Communist International. The letter, now believed to be a forgery,[47] called for the British Communist Party to support the Russian treaties and encouraged them to commit seditious activities.[48][49]

Baldwin had renounced protectionism in June 1924 and as a consequence there was no longer any major barrier for those Liberals who wanted to vote Conservative to oust the Labour government. In the election the Liberals lost over 100 seats, mainly to the Conservatives, whilst Labour suffered a net loss of 42 seats. The Conservatives won a large parliamentary majority and Baldwin again became prime minister.[50][51]

Conservative government: 1924–1929

[edit]

The government's aim was tranquillity at home and abroad, and to remedy the dislocation caused by the war through a return to the prewar world.[52][53] The 1925 Locarno Treaties, an attempt at reconciliation between France and Germany, were hailed as the harbinger of a new era of peace and it was hoped that the return to the gold standard (at the prewar parity) in 1925 would lead to the restoration of prewar conditions and prosperity.[54][55] The government aimed to reduce class conflict and ameliorate social conditions; when in March 1925 a Conservative backbencher introduced a bill to abolish the trade unions' political levy, Baldwin killed the bill with a speech in which he pleaded: "Give peace in our time, O Lord".[56][57] The government also expanded social services such as unemployment benefit and old age pensions.[58][59] However, the government failed to avert the 1926 general strike, which lasted for nine days in May. The general strike marked the end a period of industrial strife: after the strike the number of days lost to strikes fell and trade union membership declined.[60][61]

Baldwin pleaded for "Safety First" during the 1929 general election but the result was a hung parliament with Labour as the largest party. Baldwin resigned the premiership on 4 June and the next day Ramsay MacDonald became prime minister of the second Labour government.[62][63]

Second Labour government: 1929–1931

[edit]The government passed the Coal Mines Act 1930, which reduced the miners' working day to 7½ hours and empowered the mine-owners to fix minimum prices and quotas of production. The Housing Act 1930, which finally came into operation in 1934, led to more slum clearances in the five years before 1939 than in the preceding fifty.[64]

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in the Great Depression, which led to over two million unemployed by December 1930 and halved the volume of exports between 1929 and 1931.[65] In May 1930 the government rejected Oswald Mosley's memorandum which recommended state direction of industry and the use of credit to expand the economy.[66] In 1931 the government appointed Sir George May as head of a committee on national expenditure.[67][68] The May Report was published on 31 July and recommended that the government's deficit should be remedied by increased taxation and cuts in public spending.[69][70] In August there was a run on the pound and the bankers advised that a 10 percent cut in unemployment benefit as part of a balanced budget would restore confidence in sterling.[71][72] The Cabinet failed to reach agreement on the cuts and MacDonald formed the coalition National government with the Conservatives and some Liberals on 24 August.[73][74]

The Labour Party opposed the coalition and elected Arthur Henderson as their leader in the place of MacDonald, who was expelled from the party on 31 August.[75] In Labour opinion the fall of the Labour government was explained as a "bankers' ramp" and MacDonald was accused of "betrayal" and viewed as a "traitor".[76][77] Supporters of the National government accused the Labour government of "running away" from the crisis because they had refused to accept the spending cuts.[78]

National government: 1931–1939

[edit]On 28 August the National government received £80 million in credits from the bankers of Paris and New York and on 10 September Philip Snowden, who continued as Chancellor, presented his budget, which eliminated the deficit by spending cuts and increased taxation. However, the run on the pound continued and was made worse when news was received of the naval mutiny in Invergordon on 15 September, which caused alarm. The foreign holders of sterling withdrew their holdings and the pound was forced off the gold standard on 21 September.[79][80] On 7 October Parliament was dissolved and a general election was called, with polling day on 27 October. MacDonald appealed to the country to give the National government a "doctor's mandate" so that it would have a free hand to remedy the national crisis.[81][82] The National government won a landslide victory with 67 percent of the vote and the Labour Party was reduced to 52 MPs.[83][84]

The Conservatives, who made up a majority of National MPs, favoured protectionist tariffs as a solution to the depression.[85] The government combated the dumping of foreign goods imported into Britain with the Abnormal Importations (Customs Duties) Act 1931 and empowered the Minister of Agriculture to impose tariffs on fresh fruits, flowers and vegetables with the Horticultural Products (Emergency Customs Duties) Act 1931.[86][87] In February 1932 Neville Chamberlain, who replaced Snowden as Chancellor in November 1931, introduced the Import Duties Bill, which legislated for a general tariff of 10 percent on most goods except food and raw materials.[88][89] The 1932 British Empire Economic Conference led to a limited form of Imperial Preference with the Dominions of the British Empire.[90][91] This breach with free trade led to the resignation from the government of Snowden and some of the Liberals in September 1932.[92][93]

The government also passed the Special Areas Act 1934, which gave £2 million in aid to the "distressed" or "special areas", which were the hardest hit by the depression. These were designated as South Wales, Tyneside, Cumberland and Scotland.[94][95]

In response to the breakdown of the Disarmament Conference and accelerated German rearmament under Adolf Hitler, the National government launched its own rearmament programme in 1934.[96][97] However, pacifist sentiment was widespread at this time, which found expression in the King and Country debate of February 1933, when the Oxford Union passed the motion "This House will under no circumstances fight for its King and country". The October 1933 Fulham East by-election saw the Conservative candidate, who advocated rearmament, defeated by the Labour candidate, who called his opponent a warmonger.[98][99] The Peace Ballot, completed in June 1935, demonstrated overwhelming support for the League of Nations and disarmament, and less emphatic support for military measures to stop an aggressor state.[100][101] The Labour and Liberal parties opposed rearmament and instead advocated disarmament combined with collective security through the League of Nations.[102][99] Winston Churchill, who was left out of the National government, was almost a lone voice in his campaign for increased armaments.[97]

On 4 March 1935 the government published a white paper on defence which announced increased spending on the armed forces.[103][104] On 7 June Baldwin succeeded MacDonald as prime minister and called a general election in October, with polling day on 14 November.[105][106] The National government sought a mandate for rearmament to fill the gaps in Britain's defences and Baldwin told the Peace Society on 31 October that there would be "no great armaments".[107][108] The government won the election with a large though reduced majority and Labour gained around 100 seats.[107][109]

In late 1936 there was a constitutional crisis when king Edward VIII wanted to marry a divorcée, Wallis Simpson. The king was head of the Church of England but the Church disapproved of divorce and the Cabinet opposed the marriage. Edward was determined to marry Mrs Simpson and agreed to abdicate, which was announced by Baldwin in the House of Commons on 10 December and enacted by an Act of Parliament the next day.[110][111]

On 28 May 1937 Neville Chamberlain replaced Baldwin as prime minister and embarked on a series of social reforms. The Special Areas (Amendment) Act 1937 introduced concessions on taxes and rents to encourage businesses to set up works in the "special areas", which suffered the highest unemployment.[112] The government nationalised coal mining royalties through the Coal Act 1938, which was an important step towards nationalisation of the coal mines, achieved in 1946.[113][114] Whereas in the 1920s only 1½ million workers were entitled to an annual paid holiday, this increased to 3 million in 1938 and to 11 million after the enactment of the Holidays with Pay Act 1938.[115][116] The school leaving age was raised to 15 on 1 September 1939.[113]

However, Chamberlain's premiership was dominated by the challenge of Hitler, which Chamberlain attempted to resolve through appeasement of Germany's grievances combined with continued British rearmament.[117][118] The policy of appeasement culminated in the 1938 Munich Agreement, which conceded to Germany the German-speaking areas of Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland.[119][120] On 15 March 1939 the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia, despite Hitler's promise that the Sudetenland was his "last territorial demand in Europe".[121][122] British opinion was shocked and on 31 March Chamberlain pledged Britain to protect Poland and the British military resumed military conversations with France.[123][124] The government also introduced peacetime conscription for the first time with the Military Training Act 1939.[125][126] After Germany entered into a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, the government signed an alliance with Poland on 25 August and passed the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act 1939.[127][128] On 1 September Germany invaded Poland and two days later Britain and France declared war on Germany.[129][130]

Expanding the welfare state

[edit]Two major programmes dealing with unemployment and housing that permanently expanded the welfare state passed in 1919 and 1920 with surprisingly little debate, even as the Conservatives dominated parliament.

The Unemployment Insurance Act 1920 expanded the provisions of the National Insurance Act 1911. It set up the dole system that provided 39 weeks of unemployment benefits to practically the entire civilian working population except domestic servants, farm workers and civil servants. Funded in part by weekly contributions from both employers and employed, it provided weekly payments of 15s for unemployed men and 12s for unemployed women. It passed at a time of very low unemployment. Historian C. L. Mowat called these laws "Socialism by the back door," and notes how surprised politicians were when the costs to the Treasury soared during the high unemployment of 1921.[131] The Baldwin and Chamberlain governments also expanded unemployment assistance: the number of workers included in the scheme increased from 11 million in 1920 to 15.4 million in 1938.[132] For the unemployed who had exceeded their entitlement to assistance, the Unemployment Assistance Board (enacted by the Unemployment Act 1934) required them to undergo the means test to ensure that they were still eligible.[132]

Neville Chamberlain abolished poor law unions and the board of guardians by the Local Government Act 1929, which also transferred poor-law hospitals to local authorities.[132] The number of workers included in the health insurance scheme, which gave them sickness benefit and funded their medical treatment, increased from 15 million in 1921 to 20 million in 1938.[132] According to Paul Addison, Britain's social services were "the most advanced in the world in 1939".[132]

Housing

[edit]The rapid expansion of housing was a major success story of the interwar years, standing in sharp contrast to the United States, where new housing construction practically ceased after 1929. The total housing stock In England and Wales was 7.6 million in 1911; 8.0 million in 1921; 9.4 million in 1931; and 11.3 million in 1939.[133] The influential Tudor Walters Report of 1918 set the standards for council house design and location for the next 90 years.[134] It recommended housing in short terraces, spaced at 70 feet (21 m) or a density of 12 to the acre.[135] With the Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act 1919 Lloyd George set up a system of government housing that followed his 1918 campaign promises of "homes fit for heroes."[136] Also known as the "Addison Act," it required local authorities to survey their housing needs, and start building houses to replace slums. The treasury subsidised the low rents.[137] Older women could then vote. Local politicians consulted with them and in response put more emphasis on such amenities as communal laundries, extra bedrooms, indoor lavatories, running hot water, separate parlours to demonstrate their respectability, and practical vegetable gardens rather than manicured lawns.[138][139] Progress was not automatic, as shown by the troubles of rural Norfolk. Many dreams were shattered as local authorities had to renege on promises they could not fulfill due to undue haste, impossible national deadlines, debilitating bureaucracy, lack of lumber, rising costs and the non-affordability of rents by the rural poor.[140]

In England and Wales 214,000 multi-unit council buildings were built by 1939; the Ministry of Health became largely a ministry of housing.[131] Council housing accounted for 10 percent of the housing stock in Britain by 1938, peaking at 32 percent in 1980, and dropping to 18 percent by 1996, where it held steady for the next two decades.[141]

During the interwar years England experienced an unprecedented growth of the suburbs, which historians have called the "suburban revolution".[142] By 1939 over 4 million new suburban homes had been built and England went from being the most urbanised country in the world at the end of the First World War into the most suburbanised by the beginning of the Second World War.[142]

Increasingly the British ideal was home ownership, even among the working class. Rates of home ownership rose steadily from 15 percent before 1914, to 32 percent by 1938, and 67 percent by 1996. The construction industry sold the idea of home ownership to upscale renters. The mortgage lost its old stigma of a millstone round your neck to instead be seen as a smart long-term investment in suburbanised Britain. It appealed to aspirations of upward mobility and made possible the fastest rate of growth in working-class owner-occupation during the 20th century.[143][144] The boom was largely financed by the savings ordinary Britons put into their building societies. Starting in the 1920s favourable tax policies encouraged substantial investment in the societies, creating huge reserves for lending. Beginning in 1927, the societies encouraged borrowing through gradual liberalisation of mortgage terms.[145]

King George V

[edit]King George V (reigned 1910–1936) was scandal free. He appeared hard working and became widely admired by the people of Britain and the Empire, as well as "The Establishment".[146] It was George V who established the modern norm of conduct for British royalty, reflecting middle-class values and virtues rather than upper-class lifestyles or vices.[147] Anti-intellectual and lacking the sophistication of his two royal predecessors, as well as their cosmopolitan experiences, he nevertheless understood the British Empire better than most of his ministers; indeed he explained, "it has always been my dream to identify myself with the great idea of Empire."[148] He used his exceptional memory for details and faces to good effect in small talk with commoners and officials.[149] He invariably wielded his influence as a force of neutrality and moderation, seeing his role as mediator rather than final decision maker.[150] For example, in 1921 he had General Jan Smuts draft a speech calling for a compromise truce to end the Irish war of independence and secured cabinet approval; the Irish also agreed and the war ended.[151] Historian A. J. P. Taylor praises the king's initiative as, "perhaps the greatest service performed by a British monarch in modern times."[152][153] His transparent sense of duty, his loyalty, his impartiality and his unfailing example of good taste inspired the people and discouraged politicians from manipulating him to their own advantage. King George V was by temperament a cautious and conservative man who never fully appreciated or approved the revolutionary changes underway in British society. Nevertheless, everyone understood that he was earnestly devoted to Britain and the British Commonwealth.[154]

The king's popularity was enhanced during the World War when he made more than a thousand visits to hospitals, factories, and military and naval installations. He thereby gave highly visible support to the morale of ordinary workers and servicemen.[155] In 1932, George delivered his Royal Christmas speech on the radio, an event that became a popular across the British Empire every year.[156] His Silver Jubilee in 1935 became a national festival of fervent rejoicing, tinged with a few complaints.[157] His funeral and following commemorations were elaborately staged, very well attended ceremonies that redefined the role of royalty in a newly democratic nation. The people had new ways to affirm their loyalties, such as close attention to live radio broadcasts and follow-up newsreels. New ceremonies born of the commemoration of death in the Great War included the two-minute silence. Britain set up living memorials to honour and expand the king's lifelong belief in the physical, moral and social benefits of recreation and sports. The royal death thereby acted to enhance a shared Britishness. The funeral of King George VI in 1952 followed the same formula. Thereby the monarchy grew stronger and, more importantly, national cohesion was built up in the era of total war.[158]

The king was the most active monarch in many ways since George III (reigned 1760–1820). Biographer H. C. G. Matthew concludes:

- His was the busiest service of any nineteenth- or twentieth-century British monarch. He dealt with a remarkable and arduous series of crises: the reaction of the Unionists to the Parliament Bill and the home rule crisis, the complex coalition-forming of the First World War, the incorporation of the Labour Party into the working of constitutional government, the replacement of orthodox politics by a national government. George V's assiduous and non-partisan approach smoothed the process of political change which these crises represented.[12]

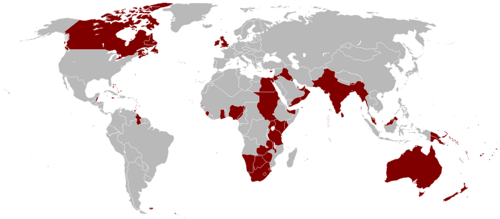

Commonwealth and Empire

[edit]After taking over the League of Nations mandates on certain German and Ottoman territories in 1919, the British Empire reached its territorial peak. The interwar years saw extensive efforts for economic and educational development of the colonies. The Dominions were prosperous and largely took care of themselves. By far the most troublesome areas for London were India and Palestine.[159][160][161][162]

The Dominions (Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand) achieved virtual independence in foreign policy in the Statute of Westminster 1931, though each depended heavily upon British naval protection.[163] After 1931 trade policy favoured Imperial Preference with higher tariffs against the U.S. and all others outside the Commonwealth.[164]

In India, the forces of nationalism were being organised by the Indian National Congress, led by Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. India contributed significantly to victory in the World War, and was bitterly disappointed by the very limited benefits conferred in the Government of India Act 1919.[165] British fears of German wartime plots or postwar Communism following the Ghadar Mutiny ensured that war-time structures were renewed by the Rowlatt Act of 1919 that suppressed dissent. Tensions escalated particularly in the Punjab region, where repressive measures culminated in the Amritsar Massacre. In Britain public opinion was divided over the morality of the massacre, between those who saw it as having saved India from anarchy, and those who viewed it with revulsion.[166] Gandhi developed the technique of nonviolent resistance, claiming moral superiority over the British use of violence.[167] Multiple negotiations were held in the 1930s, but a strong reactionary movement in Britain, led by Winston Churchill, blocked the adoption of reforms that would satisfy Indian nationalists. Historian Lawrence James states:

- From 1930 to 1935 [Churchill] was a Cassandra, warning the country that the government's policy of allowing self-determination for India would be a catastrophe for Britain and mark the beginning of the end for her Empire. His language was stark and his imagery apocalyptic: India was facing a prolonged crisis which successive governments had failed to resolve.[168] The Conservatives in Parliament designed the Government of India Act 1935 to create a federation that would facilitate continued British control and deflect the challenge of Congress.[169] The Labour Party, although in a weak minority in the 1930s, gave support to Congress and worked with Indians in Britain; after 1945 it was in a position to grant India independence.[170]

Egypt was nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, although under British rule, until 1914, when London declared it a protectorate. Independence was formally granted in 1922, though it continued to be a British client state until 1954. British troops remained stationed to guard the Suez Canal. Egypt joined the League of Nations. Iraq, a British mandate since 1920, also gained membership of the League in its own right after achieving independence from Britain in 1932. Iraq remained under firm British guidance regarding foreign affairs, defence policy and oil policy.[171]

In Palestine, Britain was presented with the problem of mediating between the Arabs and increasing numbers of Jews. The Balfour Declaration, which had been incorporated into the terms of the mandate, stated that a national home for the Jewish people would be established in Palestine. Tens of thousands of Jews immigrated from Europe. The Arab population revolted in 1936. As the prospect of war with Germany loomed larger, Britain judged the support of Arabs as more important than the establishment of a Jewish homeland, and shifted to a pro-Arab stance, limiting Jewish immigration and in turn triggering a Jewish insurgency.[172]

Dominions control their foreign policies

[edit]

As Britain's Prime Minister, Lloyd George requested military assistance from the Dominions at the outbreak of the Chanak Crisis in Turkey in 1922. He was rejected.[173] The World War had greatly strengthened the sense of nationalism and self-confidence in the dominions. They were by then independent members of the League of Nations, and refused to automatically follow requests from Britain's leaders. The right of the Dominions to set their own foreign policy, independent of Britain, was recognised at the 1923 Imperial Conference. The 1926 Imperial Conference issued the Balfour Declaration of 1926, declaring the Dominions to be "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another" within a "British Commonwealth of Nations". This declaration was given legal substance under the 1931 Statute of Westminster. India, however, was denied dominion status and its foreign policy was set by London.[174]

Newfoundland was overwhelmed by the economic disasters of the Great depression and voluntarily gave up its dominion status. It reverted to a crown colony under direct British control until it voted to join Canada in 1948.[175] The Irish Free State broke its ties with London with a new constitution in 1937, making it a republic in all but name.[176]

Foreign policy

[edit]Britain had suffered little physical devastation during the war but the cost in death and disability and money were very high. In the Khaki Election of 1918, coming a month after the Allied victory over Germany, Lloyd George promised to impose a harsh treaty on Germany. At the Paris Peace Conference in early 1919, however, he took a much more moderate approach. France and Italy demanded and achieved harsh terms, including German admission of guilt for starting the war (which humiliated Germany), and a demand that Germany pay the entire Allied cost of the war, including veterans' benefits and interest. Britain reluctantly supported the Treaty of Versailles, although many experts, most famously John Maynard Keynes, thought it was too harsh on Germany.[177][178][179]

Britain began to look on a restored Germany as an important trading partner and worried about the effect of reparations on the British economy. In the end the United States financed German debt payments to Britain, France and the other Allies through the Dawes Plan, and Britain used this income to repay the loans it borrowed from the U.S. during the war.[citation needed]

Vivid memories of the horrors and deaths of the World War made Britain and its leaders strongly inclined to pacifism in the interwar era.[180]

1920s

[edit]Britain maintained close relationships with France and the United States, rejected isolationism, and sought world peace through naval arms limitation treaties,[181] and peace with Germany through the Locarno treaties of 1925. A main goal was to restore Germany to a peaceful, prosperous state.[182]

With disarmament high on the agenda, Britain played a major role following the United States in the Washington Naval Conference of 1921 in working toward naval disarmament of the major powers. By 1933 disarmament had collapsed and the issue became rearming for a war against Germany.[183]

At the Washington Conference Britain abandoned the Two power standard - her long-time policy of paramount naval strength equal to or greater than the next two naval powers combined. Instead it accepted equality with United States, and weakness in Asian waters relative to Japan. It promised to not strengthen the fortifications of Hong Kong, which were within range of Japan. The treaty with Japan was not renewed, But Japan at the time was not engaged in expansion activities of the sort that grew momentous from 1931 onward. London cut loose from Tokyo but moved much closer to Washington.[184]

Politically the coalition government of Prime Minister David Lloyd George depended primarily on Conservative Party support. He increasingly antagonised his supporters with foreign policy miscues. The Chanak Crisis of 1922 brought Britain to the brink of war with Turkey, but the Dominions were opposed and the British military was hesitant, so peace was preserved. This was one of the factors causing Conservative MPs to vote, at the Carlton Club meeting, to fight the next election as a separate party; Lloyd George then resigned as Prime Minister, ending the coalition government.[185]

The success at Locarno in handling the German question impelled Foreign Secretary Austen Chamberlain, working with France and Italy, to find a master solution to the diplomatic problems of Eastern Europe and the Balkans. It proved impossible to overcome mutual antagonisms, because Chamberlain's programme was flawed by his misperceptions and fallacious judgments.[186]

1930s

[edit]The great challenge came from dictators, first Benito Mussolini of Italy from 1923, then from 1933 Adolf Hitler of a much more powerful Nazi Germany. Britain and France led the policy of non-interference in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). The League of Nations proved disappointing to its supporters; it was unable to resolve any of the threats posed by the dictators. British policy was to "appease" them in the hopes they would be satiated. League-authorised sanctions against Italy for its invasion of Ethiopia had support in Britain but proved a failure and were dropped in 1936.[187]

Germany was the difficult case. By 1930 British leaders and intellectuals largely agreed that all major powers shared the blame for war in 1914, and not Germany alone as the Treaty of Versailles specified. Therefore, they believed the punitive harshness of the Treaty of Versailles was unwarranted, and this view, adopted by politicians and the public, was largely responsible for supporting appeasement policies down to 1938. That is, German rejections of treaty provisions seemed justified.[188]

Coming of the Second World War

[edit]By late 1938 it was clear that war was looming, and that Germany had the world's most powerful military. British military leaders warned that Germany would win a war, and Britain needed another year or two to catch up in terms of aviation and air defence. Appeasement of Germany—giving in to its demands—was the government's policy until early 1939. The final act of appeasement came when Britain and France sacrificed Czechoslovakia to Hitler's demands at the Munich Agreement of 1938.[189] Instead of satiation Hitler then seized the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 and menaced Poland. In response Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain rejected further appeasement and stood firm in promising to defend Poland. Hitler unexpectedly cut a deal with Joseph Stalin to divide Eastern Europe; when Germany did invade Poland in September 1939, Britain and France declared war; the British Commonwealth followed London's lead.[190]

Economic history

[edit]Taxes rose sharply during the war and never returned to their old levels. A rich man paid 8% of his income in taxes before the war, and about a third afterward. Much of the money went on unemployment benefits. About 5% of the national income every year was transferred from the rich to the poor. A. J. P. Taylor argues most people "were enjoying a richer life than any previously known in the history of the world: longer holidays, shorter hours, higher real wages."[191]

The British economy was lackluster in the 1920s, with sharp declines and high unemployment in heavy industry and coal, especially in Scotland and Wales. Exports of coal and steel halved by 1939 and the business community was slow to adopt the new labour and management principles coming from the US, such as Fordism, consumer credit, eliminating surplus capacity, designing more structured management, and using greater economies of scale.[192] For over a century the shipping industry had dominated world trade, but it remained in the doldrums despite various stimulus efforts by the government. With the very sharp decline in world trade after 1929, its condition became critical.[193]

Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill put Britain back on the gold standard in 1925, which many economists blame for the mediocre performance of the economy. Others point to a variety of factors, including the inflationary effects of the World War and supply-side shocks caused by reduced working hours after the war.[194]

By the late 1920s, economic performance had stabilised, but the overall situation was disappointing, for Britain had fallen behind the United States as the leading industrial power. There also remained a strong economic divide between the north and south of England during this period, with the south of England and the Midlands fairly prosperous by the Thirties, while parts of South Wales and the industrial north of England became known as "distressed areas" due to particularly high rates of unemployment and poverty. Despite this, the standard of living continued to improve as local councils built new houses to let to families rehoused from outdated slums, with up to date facilities including indoor toilets, bathrooms and electric lighting being included in the new properties. The private sector enjoyed a housebuilding boom during the 1930s.[195]

Labour

[edit]During the war, trade unions were encouraged and their membership grew from 4.1 million in 1914 to 6.5 million in 1918. They peaked at 8.3 million in 1920 before relapsing to 5.4 million in 1923.[196][197][198] During the early 1920s strikes became less common: in 1921 over 85 million working days had been lost to strikes, in 1922 the figure declined to 19 million and in 1923 to 10 million.[199]

Coal was a sick industry; the best seams were being exhausted, raising the cost. Demand fell as oil began replacing coal for fuel. The 1926 general strike was a nine-day nationwide walkout of 1.3 million railwaymen, transport workers, printers, dockers, iron workers and steelworkers supporting the 1.2 million coal miners who had been locked out by the owners. The miners had rejected the owners' demands for longer hours and reduced pay in the face of falling prices.[200] The Conservative government had provided a nine-month subsidy in 1925 but that was not enough to turn around a sick industry. To support the miners the Trades Union Congress (TUC), an umbrella organisation of all trades unions, called out certain critical unions. The hope was the government would intervene to reorganise and rationalise the industry and raise the subsidy. The Conservative government had stockpiled supplies and essential services continued in operation using students and middle-class volunteers. All three major parties opposed the strike. The Labour Party leaders did not approve and feared it would tar the party with the image of radicalism, for the Comintern in Moscow had sent instructions for Communists to aggressively promote the strike. The general strike itself was largely non-violent, but the miners' lock-out continued and there was violence in Scotland. It was the only general strike in British history, for TUC leaders such as Ernest Bevin considered it a mistake. Most historians treat it as a singular event with few long-term consequences, but Martin Pugh says it accelerated the movement of working-class voters to the Labour Party, which led to future gains.[201][202] The Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act 1927 made general strikes illegal and ended the automatic payment of union dues to the Labour Party. That act was largely repealed in 1946. The coal industry used up the more accessible coal. As costs rose, output fell from 267 million tons in 1924 to 183 million in 1945.[203] The Labour government nationalised the mines in 1947.

Starting in 1909, Liberals, led especially by Lloyd George, promoted the idea of a minimum wage for farm workers. Resistance from landowners was strong, but success was achieved by 1924.[204] According to Robin Gowers and Timothy J. Hatton, the impact in England and Wales was significant. They estimate that it raised wages for farm labourers by 15 percent by 1929, and by more than 20 percent in the 1930s. It reduced the employment of such labourers by 54,000 (6.5 percent) in 1929 and 97,000 (13.3 percent) in 1937. They argue, "The minimum wage lifted out of poverty many families of farm labourers who remained employed, but it significantly lowered the incomes of farmers, particularly during the 1930s."[205]

Food

[edit]After the War many new food products became available to the typical household, with branded foods advertised for their convenience. The shortage of servants was felt in the kitchen, but instead of an experienced cook spending hours on difficult custards and puddings the housewife could purchase instant foods in jars, or powders that could be quickly mixed. Breakfast porridge from branded, more finely milled, oats could be cooked in two minutes, not 20. American-style dry cereals began to challenge the porridge and bacon and eggs of the middle classes, and the bread and margarine of the poor. Shops carried more bottled and canned goods and fresher meat, fish and vegetables. While wartime shipping shortages had sharply narrowed choices, the 1920s saw many new kinds of foods—especially fruits—imported from around the world, along with better quality packaging and hygiene. Middle-class households often had ice boxes or electric refrigerators, which made for better storage and the convenience of buying in larger quantities.[206]

Numerous studies in the Depression years documented that the average consumer ate better than before. Seebohm Rowntree reported that the "standard to workers in 1936 was about 30 percent higher than it was in 1899."[207] The dairy industry was producing too much, and profits were too low. So the government used the Milk Marketing Board to give a guaranteed price to dairy farmers – a policy ridiculed by The Economist as the "economics of Bedlam."[208] Food prices were low, but the advantage went overwhelmingly to the middle and upper classes, with the poorest third of the population suffering from sustained poor nutrition. Starvation was not a factor, but widespread hunger was. The deleterious effects on poor children were obvious to teachers. In 1934, the government began a program of charging school children a halfpenny a day for a third of a pint of milk. This dramatically improved their nutrition, and the new demand kept up the wholesale price of milk paid to farmers. About half the nation's school children participated by 1936. Milk was distributed for free in the Second World War, and participation rose to 90 percent. Indeed, the rationing system of the wartime years sharply improved the nutrition of poorest third, together with their capacity for manual labour.[209]

Great Depression

[edit]The Great Depression originated on Wall Street in the United States in late 1929, and quickly spread to the rest of the world. The main impact of the economic slump was felt in 1931.[210] Unlike Germany, Canada and Australia, Britain had not experienced a boom in the 1920s, so the downturn was less severe and ended sooner.[211]

Worldwide crisis

[edit]By summer 1931 the world financial crisis began to overwhelm Britain; investors across the world started withdrawing their gold from London at the rate of £2½ million a day.[212][213] Credits of £25 million each from the Bank of France and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and an issue of £15 million in fiduciary notes slowed, but did not reverse the British crisis. The financial crisis caused a major political crisis in Britain in August 1931. With deficits mounting, the bankers demanded a balanced budget; the divided cabinet of Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government agreed; it proposed to raise taxes, cut spending and most controversially, to cut unemployment benefits by 20%. The attack on welfare was totally unacceptable to the Labour movement. MacDonald wanted to resign, but the King insisted he remain and form an all-party coalition "National government." The Conservative and Liberal parties signed on, along with a small cadre of Labour, but the vast majority of Labour leaders denounced MacDonald as a traitor for leading the new government. Britain went off the gold standard, and suffered relatively less than other major countries in the Great Depression. In the 1931 British election the Labour Party was virtually destroyed, leaving MacDonald as Prime Minister of a largely Conservative coalition.[214][215]

The flight of gold continued, however, and the Treasury finally was forced to abandon the gold standard in September 1931. Until then the government had religiously followed orthodox policies, which demanded balanced-budgets and the gold standard. Instead of the predicted disaster, cutting loose from gold proved a major advantage. Immediately the exchange rate of the pound fell by 25%, from $4.86 for one pound to $3.40. British exports were then much more competitive, which laid the ground for a gradual economic recovery. The worst was over.[216][217]

Britain's world trade fell in half (1929–33); the output of heavy industry fell by a third. Employment and profits plunged in nearly all sectors. At the depth in summer 1932, registered unemployed numbered 3.5 million, and many more had only part-time employment.[218] The government tried to work inside the Commonwealth, raising tariffs for products from the United States, France and Germany, while giving preference to Commonwealth members.[219][220]

Organised protests

[edit]The north of England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales suffered particularly severe economic problems, especially if they depended on coal, steel or shipbuilding. Unemployment reached 70% in some mining localities at the start of the 1930s (with more than 3 million out of work nationally). The government was cautious and conservative, rejecting the Keynesian proposal for large-scale public works projects.[221]

Doomsayers on the left such as Sidney and Beatrice Webb, J. A. Hobson and G. D. H. Cole repeated the dire warnings they had been making for years about the imminent death of capitalism, only this time far more people paid attention.[222] Starting in 1935 the Left Book Club provided a new warning every month, and built up the credibility of Soviet-style socialism as an alternative.[223]

In 1936, by which time unemployment was lower, 200 unemployed men made a highly publicised march from Jarrow to London in a bid to show the plight of the industrial poor. Although much romanticised by the Left, the Jarrow Crusade marked a deep split in the Labour Party and resulted in no government action.[224] Unemployment remained high until the war absorbed all the job seekers. George Orwell's book The Road to Wigan Pier gives a bleak overview of the hardships of the time.

Historiography

[edit]The economic crisis of the early 1930s, and the response of the Labour and National governments to the depression, have generated much historical controversy. Apart from the major pockets of long-term high unemployment, Britain was generally prosperous. Historian Piers Brendon writes: "Historians, however, have long since revised this grim picture, presenting the devil's decade as the cradle of the affluent society. Prices fell sharply between the wars and average incomes rose by about a third. The term "property-owning democracy" was coined in the 1920s, and three million houses were built during the 1930s. Land, labour and materials were cheap: a bungalow could be purchased for £225 and a semi for £450. The middle class also bought radiograms, telephones, three-piece suites, electric cookers, vacuum cleaners and golf clubs. They ate Kellogg's Corn Flakes ("never miss a day"), drove to Odeon cinemas in Austin Sevens (costing £135 by 1930) and smoked Craven A cigarettes, cork-tipped "to prevent sore throats". The depression spawned a consumer boom."[225]

In the decades immediately following the Second World War, most historical opinion was critical of the governments of the period. Some historians, such as Robert Skidelsky in his Politicians and the Slump, compared the orthodox policies of the Labour and National governments unfavourably with the more radical proto-Keynesian measures advocated by David Lloyd George and Oswald Mosley, and the more interventionist and Keynesian responses in other economies: Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal in the United States, the Labour government in New Zealand, and the Social Democratic government in Sweden. Since the 1970s opinion has become less uniformly hostile. In the preface to the 1994 edition, Skidelsky argues that recent experience of currency crises and capital flight make it hard to be so critical of the politicians who wanted to achieve stability by cutting labour costs and defending the value of the currency.[226][227]

Society and culture

[edit]The English people were largely ethnically homogeneous during the interwar era, except for the Chinese communities in Liverpool, Swansea and the East End of London.[228] Although regional accents continued to be spoken they were on the decline and full dialects became extinct outside of literature.[228] The 1921 census revealed that there were more women than men in the population by the margin of one million and three quarters, which was largely caused by a higher infant mortality rate amongst males (with wartime losses a contributory factor).[229] The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 enabled women to join the professions and professional bodies, although the majority of women remained dependent on their husbands, especially in working class households. In most jobs women were paid less than men.[229]

Religion

[edit]While the Church of England was historically identified with the upper classes, and with the rural gentry, William Temple (1881–1944) was both a prolific theologian and a social activist, preaching Christian socialism.[230] He served as bishop of Manchester and York, and in 1942 became Archbishop of Canterbury. He advocated a broad and inclusive membership in the Church of England as a means of continuing and expanding the church's position as the established church. Temple was troubled by the high degree of animosity inside, and between the leading religious groups in Britain. In the 1930s he promoted ecumenicism, working to establish better relationships with the Nonconformists, Jews and Catholics, managing in the process to overcome his anti-Catholic bias.[231][232]

Slow decline in religiosity

[edit]Although the overall population was growing steadily, and the Catholic membership was keeping pace, the Protestants were slipping behind. Out of 30–50 million adults, they dropped slowly from 5.7 million members in 1920, and 5.4 million in 1940, to 4.3 million in 1970.[233] The Church of England decline was parallel. Methodism, the largest of the Nonconformist churches reached a peak of 841,000 members in Great Britain in 1910, slipped to 802,000 in 1920, 792,000 in 1940, 729,000 in 1960, and 488,000 in 1980.[234] The Nonconformists had built a strong base in industrial districts that specialised in mining textiles, agriculture and fishing; those were declining industries, whose share of the total male workforce was in steady decline, from 21 percent in 1921 to 13 percent in 1951. As the families migrated to southern England, or to the suburbs, they often lost contact with their childhood religion.[235] The political reverberations were most serious for the Liberal Party, which was largely based in the nonconformist community, and which rapidly lost membership in the 1920s as its leadership quarrelled, the Irish Catholics and many from the working-class moved to the Labour Party, and part of the middle class moved to the Conservative party.[236] Hoping to stem the membership decline, the three major Methodist groups merged in 1932. In Scotland the two major Presbyterian groups, the Church of Scotland and the United Free Church, merged in 1929 for the same reason. Nonetheless, the steady declension continued.[237] The nonconformist churches showed not just a decline in membership but a dramatic fall in enthusiasm. Sunday school attendance plummeted; there were far fewer new ministers. Antagonism towards the Anglican church sharply declined, and many prominent nonconformists became Anglicans, including some leading ministers. There was a falling away in the size and fervour of congregations, less interest in funding missionaries, a decline in intellectualism, and persistent complaints about the lack of money.[238] Commentator D. W. Brogan reported in 1943:

- in the generation that has passed since the great Liberal landslide of 1906, one of the greatest changes in the English religious and social landscape has been the decline of Nonconformity. Partly that decline has been due to the general weakening of the hold of Christianity on the English people, partly it is due to the comparative irrelevance of the peculiarly Nonconformist (as apart from Christian) view of the contemporary world and its problems.[239]

One aspect of the long-term decline in religiosity was that Protestants showed less and less interest in sending their children to religious schools. In localities across England, fierce battles were fought between the Nonconformists, Anglicans and Catholics, each with their own school systems supported by taxes, and secular schools and taxpayers. The Nonconformists had long taken the lead in fighting the Anglicans, who a century before had practically monopolised education. The Anglican share of the elementary school population fell from 57% in 1918 to 39% in 1939.[240] With the sustained decline in Nonconformist enthusiasm their schools closed one after another. In 1902 the Methodist Church operated 738 schools; only 28 remained in 1996.[241]

Britain continued to think of itself as a Christian country; there were few atheists or nonbelievers, and unlike the continent, there was no anti-clericalism worthy of note. A third or more prayed every day. Large majorities used formal church services to mark birth, marriage and death.[242] The great majority believed in God and heaven, although belief in hell fell off after all the deaths of the World War.[243] After 1918, Church of England services stopped practically all discussion of hell.[244]

Prayer Book crisis

[edit]Parliament had governed the Church of England since 1688, but was increasingly eager to turn control over to the church itself. It passed the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919 to establish the Church Assembly, with three houses for bishops, clergy and laity, and permitted it to legislate regulations for the Church, subject to formal approval of Parliament.[245]

A crisis suddenly emerged in 1927 over the Church's proposal to revise the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which had been in daily use for more than 250 years. The goal was to better incorporate moderate Anglo-Catholicism into the life of the Church. The bishops sought a more tolerant, comprehensive established Church. After internal debate the Church Assembly gave its approval. Evangelicals inside the Church, and Nonconformists outside, were outraged because they understood England's religious national identity to be emphatically Protestant and anti-Catholic. They denounced the revisions as a concession to ritualism and tolerance of Roman Catholicism. They mobilised support in parliament, which twice rejected the revisions after intensely heated debates. The Anglican hierarchy compromised in 1929, while strictly prohibiting extreme and Anglo-Catholic practices.[246][247]

Divorce and the abdication of the King

[edit]Standards of morality in Britain changed dramatically after the world wars, in the direction of more personal freedom, especially in sexual matters. The Church tried to hold the line, and was especially concerned to stop the rapid trend toward divorce. In 1935 it reaffirmed that, "in no circumstances can Christian men or women re-marry during the lifetime of a wife or a husband."[248] The Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang, held that the King, as the head of the Church of England, could not marry a divorcée.[249] Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin objected vigorously, noting that "although it is true that standards are lower since the war it only leads people to expect a higher standard from their King."[248] Baldwin was supported by his Conservative Party (except Churchill), as well as the Labour Party, and the prime ministers of the Commonwealth. King Edward VIII therefore was forced to abdicate the throne in 1936 when he insisted on marrying an American divorcée. Although public opinion gave him considerable support, elite opinion was hostile, and he was practically forced into exile. Archbishop Lang in a radio broadcast lashed out, blaming the upper-class social circles that Edward frequented:

- Even more strange and sad it is that he should have sought his happiness in a manner inconsistent with the Christian principles of marriage, and within a social circle whose standards and ways of life are alien to all the best instincts and traditions of the people....Let those who belong to this circle know that to-day they stand rebuked by the judgment of the nation which loved King Edward.[250]

Edward's biographer Philip Ziegler argues that Edward was poorly prepared to be King, because of deep personal weaknesses; he was inconsistent, superficial and incapable of resisting distractions, and handled the constitutional issues poorly.[251] Frank Mort argues that cultural historians have read the abdication story not so much as a constitutional crisis, but as an indicator of:

- The ascendancy of a female ethos of domesticity and privacy....Intense interest in the King's affair ...[exemplified] this obsession with personal life, which was itself part of the media-fuelled emotional character of the late 1930s.[252]

John Charmley argues in the history of the Conservative Party that Baldwin was pushing for more democracy, and less of an old aristocratic upper-class tone. Monarchy was to be a national foundation, whereby the head of the Church, the State and the Empire, by drawing upon 1,000 years of tradition, could unify the nation. George V was an ideal fit: "an ordinary little man with the philistine tastes of most of his subjects, he could be presented as the archetypical English paterfamilias getting on with his duties without fuss." Charmley finds that George V and Baldwin, "made a formidable conservative team, with their ordinary, honest, English decency proving the first (and most effective) bulwark against revolution." Edward VIII, flaunting his upper-class playboy style, suffered from an unstable neurotic character. He needed a strong stabilising partner—a role Mrs. Simpson was unable to provide. Baldwin's final achievement was to smooth the way for Edward to abdicate in favour of his younger brother who became George VI. Father and son both demonstrated the value of a democratic king during the severe physical and psychological hardships of the world wars, and their tradition was carried on by Elizabeth II.[253]

Newspapers

[edit]After the war, the major newspapers engaged in a large-scale circulation race. The political parties, which long had sponsored their own papers, could not keep up, and one after another their outlets were sold or closed down.[254] Sales in the millions depended on popular stories, with a strong human interesting theme, as well as detailed sports reports with the latest scores. Serious news was a niche market and added very little to the circulation base. The niche was dominated by The Times and, to a lesser extent, The Daily Telegraph. Consolidation was rampant, as local dailies were bought up and added to chains based in London. James Curran and Jean Seaton report:

- after the death of Lord Northcliffe in 1922, four men–Lords Beaverbrook (1879–1964), Rothermere (1868–1940), Camrose (1879–1954) and Kemsley (1883–1968)–became the dominant figures in the inter-war press. In 1937, for instance, they owned nearly one in every two national and local daily papers sold in Britain, as well as one in every three Sunday papers that were sold. The combined circulation of all their newspapers amounted to over thirteen million.[255]

Just over half of homes purchased a daily newspaper in 1939.[256] The Times of London was long the most influential prestige newspaper, although far from having the largest circulation. It gave far more attention to serious political and cultural news.[257] In 1922, John Jacob Astor (1886–1971), son of the 1st Viscount Astor (1849–1919), bought The Times from the Northcliffe estate. The paper advocated appeasement of Hitler's demands. Its editor Geoffrey Dawson was closely allied with Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, and pushed hard for the Munich Agreement in 1938. Candid news reports by Norman Ebbutt from Berlin that warned of warmongering were rewritten in London to support the appeasement policy. In March 1939, however, it reversed course and called for urgent war preparations.[258][259]

The daily newspaper most respected abroad was the Liberal Manchester Guardian.[260] The Conservative Morning Post generally took a diehard position and its typical reader was portrayed as a retired senior officer and his family.[261] The Daily Telegraph was a businessman's newspaper and had the largest advertising space of any paper, while The Daily Mail appealed predominantly to middle-class and lower-middle-class readers, and was the first paper to cater for women and children.[262] The only newspaper intended specifically for working class readers was the Labour Daily Herald, which had a circulation of 100,000.[263] The most important literary periodical during the interwar years was The Times Literary Supplement.[264]

Expanded leisure

[edit]As leisure, literacy, wealth, ease of travel and a broadened sense of community grew in Britain from the late 19th century onward, there was more time and interest in leisure activities of all sorts, on the part of all classes.[265] Drinking was differentiated by class, with upper-class clubs and working-class and middle-class pubs. However, drinking as a way of spending leisure time and spare cash declined during the Depression and pub attendance never returned to 1930 levels; it fell far below prewar levels.[266] The majority of pubs were divided into public bars and saloon bars. The saloon bars catered for those who paid an extra halfpenny a pint on beer in exchange for more select company and slightly better furniture. Public bars were often spare of ornamentation except for advertisements and a dart-board, which was not found in the saloons.[267]

Taxes were raised on beer, but there were more alternatives at hand, such as cigarettes (which attracted 8/10 men and 4/10 women), the talkies, the dance halls and Greyhound racing. Football pools offered the excitement of betting on a range of results. New estates with small, inexpensive houses offered gardening as an outdoor recreation. Church attendance declined to half the level of 1901.[268]

The annual holiday became common. Tourists flocked to seaside resorts; Blackpool hosted 7 million visitors a year in the 1930s.[269] Organised leisure was primarily a male activity, with middle-class women allowed in at the margins. Participation in sports and all sorts of leisure activities increased for the average Englishman, and his interest in spectator sports increased dramatically. By the 1920s the cinema and radio attracted all classes, ages and genders in very large numbers, with young women taking the lead.[270] Working-class men were boisterous football spectators. They sang along at the music hall, fancied their pigeons, gambled on horse racing, and took the family to seaside resorts in summer. Political activists complained that working-class leisure diverted men away from revolutionary agitation.[271]

Cinema and radio

[edit]

The British film industry emerged in the 1890s, and built heavily on the strong reputation of the London legitimate theatre for actors, directors and producers.[272][273][274] The problem was that the American market was so much larger and richer. It bought up the top talent, especially when Hollywood came to the fore in the 1920s and produced over 80 percent of the total world output. Efforts to fight back were futile—the government set a quota for British made films, but it failed. Hollywood furthermore dominated the lucrative Canadian and Australian markets. Bollywood (based in Bombay) dominated the huge Indian market.[275] The most prominent directors remaining in London were Alexander Korda, an expatriate Hungarian, and Alfred Hitchcock. There was a revival of creativity in the 1933–45 era, especially with the arrival of Jewish filmmakers and actors fleeing the Nazis.[276][277] Meanwhile, giant palaces were built for the huge audiences that wanted to see Hollywood films. In Liverpool 40 percent of the population attended one of the 69 cinemas once a week; 25 percent went twice. Traditionalists grumbled about the American cultural invasion, but the permanent impact was minor.[278][279]

In radio British audiences had no choice apart from the highbrow programming of the BBC, which had a monopoly on broadcasting. John Reith (1889–1971), an intensely moralistic engineer, was in full charge. His goal was to broadcast, "All that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement.... The preservation of a high moral tone is obviously of paramount importance."[280] Reith succeeded in building a high wall against an American-style free-for-all in radio in which the goal was to attract the largest audiences and thereby secure the greatest advertising revenue. There was no paid advertising on the BBC; all the revenue came from a licence fee charged for the possession of receivers. Highbrow audiences, however, greatly enjoyed it.[281] At a time when American, Australian and Canadian stations were drawing huge audiences cheering for their local teams with the broadcast of baseball, rugby and ice-hockey, the BBC emphasised service for a national, rather than a regional audience. Boat races were well covered along with tennis and horse racing, but the BBC was reluctant to spend its severely limited air time on long football or cricket games, regardless of their popularity.[282][283]

Sports

[edit]The British showed a more profound interest in sports, and in greater variety, than any rival.[284] They gave pride of place to such moral issues as sportsmanship and fair play.[265] Cricket became symbolic of the Imperial spirit throughout the Empire. Football proved highly attractive to the urban working classes, which introduced the rowdy spectator to the sports world. In some sports there was significant controversy in the fight for amateur purity especially in rugby and rowing. New games became popular almost overnight, including golf, lawn tennis, cycling and hockey. Women were much more likely to enter these sports than the old established ones. The aristocracy and landed gentry, with their ironclad control over land rights, dominated hunting, shooting, fishing and horse racing.[285][286]

Cricket had become well established among the English upper class in the 18th century, and was a major factor in sports competition among the public schools. Army units around the Empire had time on their hands, and encouraged the locals to learn cricket so they could have some entertaining competition. Most of the Dominions of the Empire embraced cricket as a major sport, with the exception of Canada. Cricket test matches (international) began by the 1870s; the most famous are those between Australia and England for The Ashes.[287]

For sports to become fully professionalised, coaching had to come first. It gradually professionalised in the Victorian era and the role was well established by 1914. In the First World War, military units sought out the coaches to supervise physical conditioning and develop morale-building teams.[288]

Reading

[edit]As literacy and leisure time expanded after 1900 reading became a popular pastime. New additions to adult fiction doubled during the 1920s, reaching 2,800 new books a year by 1935. Libraries tripled their stock, and saw heavy demand for new fiction.[289] A dramatic innovation was the inexpensive paperback, pioneered by Allen Lane (1902–70) at Penguin Books in 1935. The first titles included novels by Ernest Hemingway and Agatha Christie. They were sold cheaply (usually sixpence) in a wide variety of inexpensive stores such as Woolworth's. Penguin aimed at an educated middle-class "middlebrow" audience. It avoided the downscale image of American paperbacks. The line signalled cultural self-improvement and political education. The more polemical Penguin Specials, typically with a leftist orientation for Labour readers, were widely distributed during the Second World War.[290] However, the war years caused a shortage of staff for publishers and book stores, and a severe shortage of rationed paper, worsened by the air raid on Paternoster Row in 1940 that burned 5 million books in warehouses.[291]